House Committee on Un-American Activities on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative

The

The

On May 26, 1938, the House Committee on Un-American Activities was established as a special investigating committee, reorganized from its previous incarnations as the Fish Committee and the McCormack–Dickstein Committee, to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having communist or fascist ties; however, it concentrated its efforts on communists. It was chaired by

On May 26, 1938, the House Committee on Un-American Activities was established as a special investigating committee, reorganized from its previous incarnations as the Fish Committee and the McCormack–Dickstein Committee, to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having communist or fascist ties; however, it concentrated its efforts on communists. It was chaired by

The House Committee on Un-American Activities became a standing (permanent) committee in 1945. Democratic Representative Edward J. Hart of New Jersey became the committee's first chairman. Under the mandate of Public Law 601, passed by the

The House Committee on Un-American Activities became a standing (permanent) committee in 1945. Democratic Representative Edward J. Hart of New Jersey became the committee's first chairman. Under the mandate of Public Law 601, passed by the

On July 31, 1948, the committee heard testimony from

On July 31, 1948, the committee heard testimony from  Chambers named more than a half-dozen government officials including White as well as

Chambers named more than a half-dozen government officials including White as well as

In the wake of the downfall of McCarthy (who never served in the House, nor on HUAC), the prestige of HUAC began a gradual decline in the late 1950s. By 1959, the committee was being denounced by former President

In the wake of the downfall of McCarthy (who never served in the House, nor on HUAC), the prestige of HUAC began a gradual decline in the late 1950s. By 1959, the committee was being denounced by former President

''Records of the US House of Representatives, Record Group 233: Records of the House Un-American Activities Committee, 1945–1969 (Renamed the) House Internal Security Committee, 1969–1976.''

Washington, DC: Center for Legislative Archives, National Archives and Records, July 1995; p. 4. The committee's files and staff were transferred on that day to the House Judiciary Committee.

Investigation of un-American propaganda activities in the United States. Hearings before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives (1938–1944), Volumes 1–17 with Appendices.

University of Pennsylvania online gateway to Internet Archive and Hathi Trust.

United States House Committee on Internal Security

University of Pennsylvania online gateway to Internet Archive and Hathi Trust. * Schamel, Gharles E. Inventory of records of the Special Committee on Un-American activities, 1938–1944 (the Dies committee). Center for Legislative Archives,

''Records of the House Un-American Activities committee, 1945–1969, renamed the House Internal Security committee, 1969–1976.''

Center for Legislative Archives, National Archives and Records Administration. Washington, D.C., July 1995. *

*

History.House.gov

HUAC – permanent standing House Committee on Un-American Activities

History.House.gov

HUAC – 1948 Alger Hiss-Whittaker Chambers hearing before HUAC

Eastern Carolina University Libraries

The Cold War and Internal Security Collection (CWIS): HUAC

The Spartacus Educational website, UK * House Unamerican Activities Committee (HUAC) Collection: Pamphlets collected by HUAC, many of which the committee deemed "un-American". (4,000 pamphlets). From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

{{Authority control 1938 establishments in Washington, D.C. 1975 disestablishments in Washington, D.C. Anti-communist organizations in the United States Cold War history of the United States Un-American activities McCarthyism Political repression in the United States Government agencies established in 1938

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them more ...

of the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together the ...

, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having either fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

or communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

ties. It became a standing (permanent) committee in 1945, and from 1969 onwards it was known as the House Committee on Internal Security. When the House abolished the committee in 1975, its functions were transferred to the House Judiciary Committee

The U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary, also called the House Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of the United States House of Representatives. It is charged with overseeing the administration of justice within the federal courts, ...

.

The committee's anti-communist investigations are often associated with McCarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left so ...

, although Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarthy became the most visi ...

himself (as a U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

) had no direct involvement with the House committee. McCarthy was the chairman of the Government Operations Committee and its Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

The Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (PSI), stood up in March 1941 as the "Truman Committee," is the oldest subcommittee of the United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs (formerly the Committee on Governme ...

of the U.S. Senate, not the House.

History

Precursors to the committee

Overman Committee (1918–1919)

The

The Overman Committee

The Overman Committee was a special subcommittee of the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary chaired by North Carolina Democrat Lee Slater Overman. Between September 1918 and June 1919, it investigated German and Bolshevik elements ...

was a subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nomination ...

chaired by North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia a ...

Democratic

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

Lee Slater Overman

Lee Slater Overman (January 3, 1854December 12, 1930) was a Democratic U.S. senator from the state of North Carolina between 1903 and 1930. He was the first US Senator to be elected by popular vote in the state, as the legislature had appointed ...

that operated from September 1918 to June 1919. The subcommittee investigated German as well as "Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

elements" in the United States.Schmidt, p. 136

This subcommittee was originally concerned with investigating pro-German sentiments in the American liquor industry. After World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

ended in November 1918, and the German threat lessened, the subcommittee began investigating Bolshevism, which had appeared as a threat during the First Red Scare

The First Red Scare was a period during the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of far-left movements, including Bolshevism and anarchism, due to real and imagined events; real events included the Ru ...

after the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

in 1917. The subcommittee's hearing into Bolshevik propaganda, conducted February 11 to March 10, 1919, had a decisive role in constructing an image of a radical threat to the United States during the first Red Scare.Schmidt, p. 144

Fish Committee (1930)

U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

Hamilton Fish III

Hamilton Fish III (born Hamilton Stuyvesant Fish and also known as Hamilton Fish Jr.; December 7, 1888 – January 18, 1991) was an American soldier and politician from New York State. Born into a family long active in the state, he served in t ...

(R-NY), who was a fervent anti-communist, introduced, on May 5, 1930, House Resolution 180, which proposed to establish a committee to investigate communist activities in the United States. The resulting committee, Special Committee to Investigate Communist Activities in the United States commonly known as the Fish Committee, undertook extensive investigations of people and organizations suspected of being involved with or supporting communist activities in the United States. Among the committee's targets were the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". ...

and communist presidential candidate William Z. Foster

William Zebulon Foster (February 25, 1881 – September 1, 1961) was a radical American labor organizer and Communist politician, whose career included serving as General Secretary of the Communist Party USA from 1945 to 1957. He was previ ...

. The committee recommended granting the United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a United States federal executive departments, federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and a ...

more authority to investigate communists, and strengthening of immigration and deportation laws to keep communists out of the United States.

McCormack–Dickstein Committee (1934–1937)

From 1934 to 1937, The committee, now named the Special Committee on Un-American Activities Authorized to Investigate Nazi Propaganda and Certain Other Propaganda Activities, chaired by John William McCormack ( D- Mass.) andSamuel Dickstein

Samuel Dickstein (February 5, 1885 – April 22, 1954) was a Democratic Congressional Representative from New York (22-year tenure), a New York State Supreme Court Justice, and a Soviet spy. He played a key role in establishing the committee tha ...

(D-NY), held public and private hearings and collected testimony filling 4,300 pages. The Special Committee was widely known as the McCormack–Dickstein committee. Its mandate was to get "information on how foreign subversive propaganda entered the U.S. and the organizations that were spreading it." Its records are held by the National Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an " independent federal agency of the United States government within the executive branch", charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It i ...

as records related to HUAC.

In 1934, the Special Committee subpoenaed most of the leaders of the fascist movement in the United States. Beginning in November 1934, the committee investigated allegations of a fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

plot to seize the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest, Washington, D.C., NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. preside ...

, known as the "Business Plot

The Business Plot (also called the Wall Street Putsch and The White House Putsch) was an alleged political conspiracy in 1933, in the United States to overthrow the government of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and install Smedley Butler as ...

". Contemporary newspapers widely reported the plot as a hoax. However contemporary sources and some of those involved, such as Gen. Smedley Butler

Major General Smedley Darlington Butler (July 30, 1881June 21, 1940), nicknamed the "Maverick Marine", was a senior United States Marine Corps officer who fought in the Philippine–American War, the Boxer Rebellion, the Mexican Revolution and ...

, confirmed the validity of such a plot.

It has been reported that while Dickstein served on this committee and the subsequent Special investigation Committee, he was paid $1,250 a month by the Soviet NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

, which hoped to get secret congressional information on anti-communists and pro-fascists. A 1939 NKVD report stated Dickstein handed over "materials on the war budget for 1940, records of conferences of the budget subcommission, reports of the war minister, chief of staff and etc." However the NKVD was dissatisfied with the amount of information provided by Dickstein, after he was not appointed to HUAC to "carry out measures planned by us together with him." Dickstein unsuccessfully attempted to expedite the deportation of Soviet defector Walter Krivitsky

Walter Germanovich Krivitsky (Ва́льтер Ге́рманович Криви́цкий; June 28, 1899 – February 10, 1941) was a Soviet intelligence officer who revealed plans of signing the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact after he defected to ...

, while the Dies Committee kept him in the country. Dickstein stopped receiving NKVD payments in February 1940.

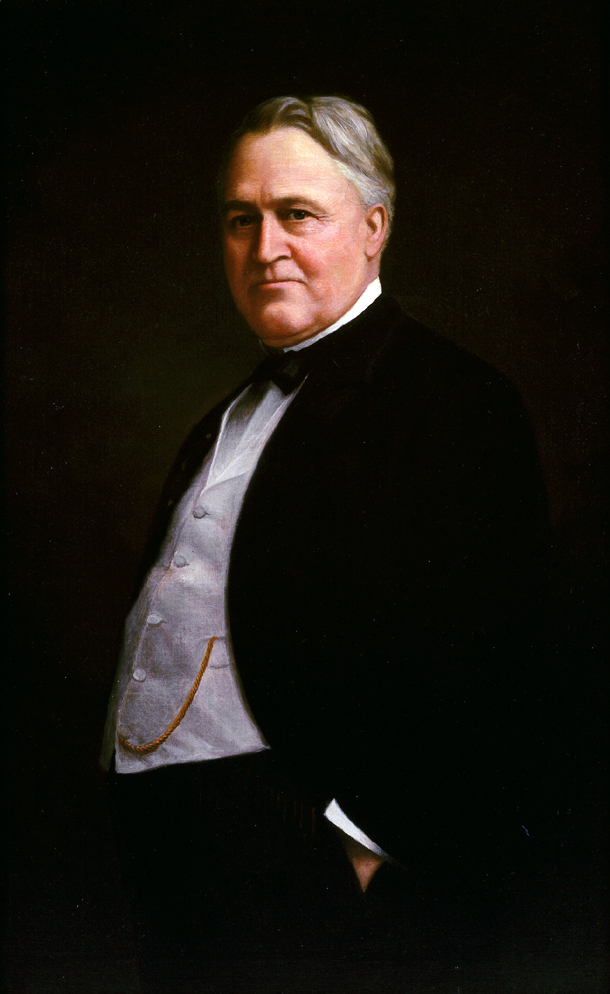

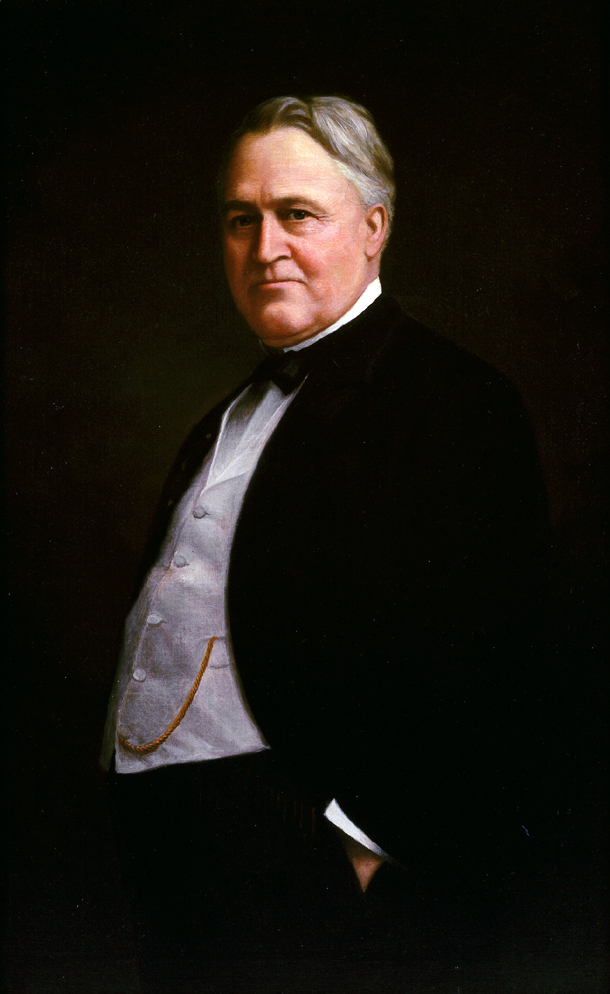

Dies Committee (1938–1944)

On May 26, 1938, the House Committee on Un-American Activities was established as a special investigating committee, reorganized from its previous incarnations as the Fish Committee and the McCormack–Dickstein Committee, to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having communist or fascist ties; however, it concentrated its efforts on communists. It was chaired by

On May 26, 1938, the House Committee on Un-American Activities was established as a special investigating committee, reorganized from its previous incarnations as the Fish Committee and the McCormack–Dickstein Committee, to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having communist or fascist ties; however, it concentrated its efforts on communists. It was chaired by Martin Dies Jr.

Martin Dies Jr. (November 5, 1900 – November 14, 1972), also known as Martin Dies Sr., was a Texas politician and a Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives. He was elected as a Democrat to the Seventy-second and after ...

(D-Tex.), and therefore known as the Dies Committee. Its records are held by the National Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an " independent federal agency of the United States government within the executive branch", charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It i ...

as records related to HUAC.

In 1938, Hallie Flanagan

Hallie Flanagan Davis (August 27, 1889 in Redfield, South Dakota – June 23, 1969 in Old Tappan, New Jersey) was an American theatrical producer and director, playwright, and author, best known as director of the Federal Theatre Project, a ...

, the head of the Federal Theatre Project

The Federal Theatre Project (FTP; 1935–1939) was a theatre program established during the Great Depression as part of the New Deal to fund live artistic performances and entertainment programs in the United States. It was one of five Federal P ...

, was subpoenaed to appear before the committee to answer the charge the project was overrun with communists. Flanagan was called to testify for only a part of one day, while an administrative clerk from the project was called in for two entire days. It was during this investigation that one of the committee members, Joe Starnes (D-Ala.), famously asked Flanagan whether the English Elizabethan era

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female person ...

playwright Christopher Marlowe was a member of the Communist Party, and mused that ancient Greek tragedian " Mr. Euripides" preached class warfare

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The forms ...

.

In 1939, the committee investigated people involved with pro-Nazi organizations such as Oscar C. Pfaus

Oscar Carl Pfaus (born Oskar Karl Pfaus; born January 30, 1901) was a German immigrant who became an American citizen through military service. He had a succession of jobs before becoming involved in pro-Nazi organizations in Chicago in the early ...

and George Van Horn Moseley. Moseley testified before the committee for five hours about a "Jewish Communist conspiracy" to take control of the US government. Moseley was supported by Donald Shea of the American Gentile League, whose statement was deleted from the public record as the committee found it so objectionable.

The committee also put together an argument for the internment of Japanese Americans

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

known as the "Yellow Report". Organized in response to rumors of Japanese Americans being coddled by the War Relocation Authority

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency established to handle the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was t ...

(WRA) and news that some former inmates would be allowed to leave camp and Nisei

is a Japanese-language term used in countries in North America and South America to specify the ethnically Japanese children born in the new country to Japanese-born immigrants (who are called ). The are considered the second generatio ...

soldiers to return to the West Coast, the committee investigated charges of fifth column

A fifth column is any group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. According to Harris Mylonas and Scott Radnitz, "fifth columns" are “domestic actors who work to un ...

activity in the camps. A number of anti-WRA arguments were presented in subsequent hearings, but Director Dillon Myer debunked the more inflammatory claims. The investigation was presented to the 77th Congress, and alleged that certain cultural traits – Japanese loyalty to the Emperor, the number of Japanese fishermen in the US, and the Buddhist faith – were evidence for Japanese espionage. With the exception of Rep. Herman Eberharter (D-Pa.), the members of the committee seemed to support internment, and its recommendations to expedite the impending segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of human ...

of "troublemakers", establish a system to investigate applicants for leave clearance, and step up Americanization and assimilation efforts largely coincided with WRA goals.

In 1946, the committee considered opening investigations into the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Ca ...

, but decided against doing so, prompting white supremacist committee member John E. Rankin (D-Miss.) to remark, "After all, the KKK is an old American institution." Instead of the Klan, HUAC concentrated on investigating the possibility that the American Communist Party

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

had infiltrated the Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, in ...

, including the Federal Theatre Project

The Federal Theatre Project (FTP; 1935–1939) was a theatre program established during the Great Depression as part of the New Deal to fund live artistic performances and entertainment programs in the United States. It was one of five Federal P ...

and the Federal Writers' Project

The Federal Writers' Project (FWP) was a federal government project in the United States created to provide jobs for out-of-work writers during the Great Depression. It was part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal program. It w ...

. Twenty years later, in 1965–1966, however, the committee did conduct an investigation into Klan activities under chairman Edwin Willis (D-La.).

Standing Committee (1945–1975)

The House Committee on Un-American Activities became a standing (permanent) committee in 1945. Democratic Representative Edward J. Hart of New Jersey became the committee's first chairman. Under the mandate of Public Law 601, passed by the

The House Committee on Un-American Activities became a standing (permanent) committee in 1945. Democratic Representative Edward J. Hart of New Jersey became the committee's first chairman. Under the mandate of Public Law 601, passed by the 79th Congress

The 79th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, DC from January 3, 1945, ...

, the committee of nine representatives investigated suspected threats of subversion or propaganda that attacked "the form of government as guaranteed by our Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

".

Under this mandate, the committee focused its investigations on real and suspected communists in positions of actual or supposed influence in the United States society. A significant step for HUAC was its investigation of the charges of espionage brought against Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official accused in 1948 of having spied for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Statutes of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjury in co ...

in 1948. This investigation ultimately resulted in Hiss's trial and conviction for perjury, and convinced many of the usefulness of congressional committees for uncovering communist subversion.

The chief investigator was Robert E. Stripling, senior investigator Louis J. Russell, and investigators Alvin Williams Stokes

Alvin William Stokes (1904-1982) was a 20th-century African-American civil servant, best known as an investigator for the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC).

Background

Alvin W. Stokes was born on December 4, 1904, in New York City. ...

, Courtney E. Owens

Courtney E. Owens (1924–2014), AKA Courtney Owens, was a 20th-century American civil servant, best known as chief investigator for the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) from 1954 to 1957.

Background

Courtney Elwell Owens was born ...

, and Donald T. Appell. The director of research was Benjamin Mandel.

Hollywood blacklist

In 1947, the committee held nine days of hearings into alleged communist propaganda and influence in theHollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywoo ...

motion picture industry. After conviction on contempt of Congress

Contempt of Congress is the act of obstructing the work of the United States Congress or one of its committees. Historically, the bribery of a U.S. senator or U.S. representative was considered contempt of Congress. In modern times, contempt of ...

charges for refusal to answer some questions posed by committee members, " The Hollywood Ten" were blacklisted

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist (or black list) of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list. If someone is on a blacklist, t ...

by the industry. Eventually, more than 300 artists – including directors, radio commentators, actors, and particularly screenwriters – were boycotted by the studios. Some, like Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American actor, director, producer, and screenwriter, known for his innovative work in film, radio and theatre. He is considered to be among the greatest and most influential f ...

, Alan Lomax

Alan Lomax (; January 31, 1915 – July 19, 2002) was an American ethnomusicologist, best known for his numerous field recordings of folk music of the 20th century. He was also a musician himself, as well as a folklorist, archivist, writer, s ...

, Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, stage and film actor, professional football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for his ...

, and Yip Harburg

Edgar Yipsel Harburg (born Isidore Hochberg; April 8, 1896 – March 5, 1981) was an American popular song lyricist and librettist who worked with many well-known composers. He wrote the lyrics to the standards "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?" ( ...

, left the U.S or went underground to find work. Others like Dalton Trumbo

James Dalton Trumbo (December 9, 1905 – September 10, 1976) was an American screenwriter who scripted many award-winning films, including ''Roman Holiday'' (1953), ''Exodus'', '' Spartacus'' (both 1960), and ''Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo'' (1944 ...

wrote under pseudonyms

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name ( orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individu ...

or the names of colleagues. Only about ten percent succeeded in rebuilding careers within the entertainment industry.

In 1947, studio executives told the committee that wartime films—such as ''Mission to Moscow

''Mission to Moscow'' is a 1943 film directed by Michael Curtiz, based on the 1941 book by the former U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, Joseph E. Davies.

The movie chronicles the experiences of the second American ambassador to the Soviet ...

'', '' The North Star'', and ''Song of Russia

''Song of Russia'' is a 1944 American war film made and distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The picture was credited as being directed by Gregory Ratoff, though Ratoff collapsed near the end of the five-month production, and was replaced by Lás ...

''—could be considered pro-Soviet propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loa ...

, but claimed that the films were valuable in the context of the Allied war effort, and that they were made (in the case of ''Mission to Moscow'') at the request of White House officials. In response to the House investigations, most studios produced a number of anti-communist and anti-Soviet propaganda films such as '' The Red Menace'' (August 1949), ''The Red Danube

''The Red Danube'' is a 1949 American drama film directed by George Sidney and starring Walter Pidgeon. The film is set during Operation Keelhaul and was based on the 1947 novel '' Vespers in Vienna'' by Bruce Marshall.

Plot

In Rome shortly aft ...

'' (October 1949), ''The Woman on Pier 13

''The Woman on Pier 13'' is a 1949 American film noir drama directed by Robert Stevenson and starring Laraine Day, Robert Ryan, and John Agar. It previewed in Los Angeles and San Francisco in 1949 under the title ''I Married a Communist'' but, ...

'' (October 1949), ''Guilty of Treason

''Guilty of Treason'' is a 1950 American drama film directed by Felix E. Feist and starring Charles Bickford, Bonita Granville and Paul Kelly. Also known by the alternative title ''Treason'', it is an anti-communist and anti-Soviet film about t ...

'' (May 1950, about the ordeal and trial of Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**'' Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**'' Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, ...

József Mindszenty

József Mindszenty (; 29 March 18926 May 1975) was a Hungarian cardinal of the Catholic Church who served as Archbishop of Esztergom and leader of the Catholic Church in Hungary from 1945 to 1973. According to the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' ...

), '' I Was a Communist for the FBI'' (May 1951, Academy Award nominated for best documentary 1951, also serialized for radio), ''Red Planet Mars

''Red Planet Mars'' is a 1952 American science fiction film released by United Artists starring Peter Graves and Andrea King. It is based on a 1932 play ''Red Planet'' written by John L. Balderston and John Hoare and was directed by art directo ...

'' (May 1952), and John Wayne's ''Big Jim McLain

''Big Jim McLain'' is a 1952 American film noir political thriller film starring John Wayne and James Arness as HUAC investigators hunting down communists in the postwar Hawaii organized-labor scene. Edward Ludwig directed.

This was the first ...

'' (August 1952). Universal-International Pictures

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Americ ...

was the only major studio that did not purposefully produce such a film.

Whittaker Chambers and Alger Hiss

On July 31, 1948, the committee heard testimony from

On July 31, 1948, the committee heard testimony from Elizabeth Bentley

Elizabeth Terrill Bentley (January 1, 1908 – December 3, 1963) was an American spy and member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). She served the Soviet Union from 1938 to 1945 until she defected from the Communist Party and Soviet intellig ...

, an American who had been working as a Soviet agent in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. Among those whom she named as communists was Harry Dexter White

Harry Dexter White (October 29, 1892 – August 16, 1948) was a senior U.S. Treasury department official. Working closely with the Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr., he helped set American financial policy toward the Allies of World W ...

, a senior U.S. Treasury department official. The committee subpoenaed Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers (born Jay Vivian Chambers; April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was an American writer-editor, who, after early years as a Communist Party member (1925) and Soviet spy (1932–1938), defected from the Soviet underground (1938) ...

on August 3, 1948. Chambers, too, was a former Soviet spy, by then a senior editor of ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, t ...

'' magazine.

Chambers named more than a half-dozen government officials including White as well as

Chambers named more than a half-dozen government officials including White as well as Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official accused in 1948 of having spied for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Statutes of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjury in co ...

(and Hiss' brother Donald). Most of these former officials refused to answer committee questions, citing the Fifth Amendment. White denied the allegations, and died of a heart attack a few days later. Hiss also denied all charges; doubts about his testimony though, especially those expressed by freshman Congressman Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was t ...

, led to further investigation that strongly suggested Hiss had made a number of false statements.

Hiss challenged Chambers to repeat his charges outside a Congressional committee, which Chambers did. Hiss then sued for libel, leading Chambers to produce copies of State Department documents which he claimed Hiss had given him in 1938. Hiss denied this before a grand jury, was indicted for perjury, and subsequently convicted and imprisoned.

The present-day House of Representatives website on HUAC states, "But in the 1990s, Soviet archives conclusively revealed that Hiss had been a spy on the Kremlin’s payroll."

Decline

In the wake of the downfall of McCarthy (who never served in the House, nor on HUAC), the prestige of HUAC began a gradual decline in the late 1950s. By 1959, the committee was being denounced by former President

In the wake of the downfall of McCarthy (who never served in the House, nor on HUAC), the prestige of HUAC began a gradual decline in the late 1950s. By 1959, the committee was being denounced by former President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

as the "most un-American thing in the country today".

In May 1960, the committee held hearings in San Francisco City Hall

San Francisco City Hall is the seat of government for the City and County of San Francisco, California. Re-opened in 1915 in its open space area in the city's Civic Center, it is a Beaux-Arts monument to the City Beautiful movement that epito ...

which led to the infamous riot on May 13, when city police officers fire-hosed protesting students from the UC Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of Californi ...

, Stanford

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

, and other local colleges, and dragged them down the marble steps beneath the rotunda, leaving some seriously injured. Soviet affairs expert William Mandel, who had been subpoenaed to testify, angrily denounced the committee and the police in a blistering statement which was aired repeatedly for years thereafter on Pacifica Radio

Pacifica may refer to:

Art

* ''Pacifica'' (statue), a 1938 statue by Ralph Stackpole for the Golden Gate International Exposition

Places

* Pacifica, California, a city in the United States

** Pacifica Pier, a fishing pier

* Pacifica, a conce ...

station KPFA

KPFA (94.1 FM) is an American listener-funded talk radio and music radio station located in Berkeley, California, broadcasting to the San Francisco Bay Area. KPFA airs public news, public affairs, talk, and music programming. The station sig ...

in Berkeley. An anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and th ...

propaganda film, ''Operation Abolition'', was produced by the committee from subpoenaed local news reports, and shown around the country during 1960 and 1961. In response, the Northern California ACLU

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". ...

produced a film called ''Operation Correction'', which discussed falsehoods in the first film. Scenes from the hearings and protest were later featured in the Academy Award-nominated 1990 documentary ''Berkeley in the Sixties

''Berkeley in the Sixties'' is a 1990 documentary film by Mark Kitchell.

Summary

The film highlights the origins of the Free Speech Movement beginning with the May 1960 House Un-American Activities Committee hearings at San Francisco City Hall, ...

''.

The committee lost considerable prestige as the 1960s progressed, increasingly becoming the target of political satirists and the defiance of a new generation of political activists. HUAC subpoenaed Jerry Rubin

Jerry Clyde Rubin (July 14, 1938 – November 28, 1994) was an American social activist, anti-war leader, and counterculture icon during the 1960s and 1970s. During the 1980s, he became a successful businessman. He is known for being one of the ...

and Abbie Hoffman

Abbot Howard "Abbie" Hoffman (November 30, 1936 – April 12, 1989) was an American political and social activist who co-founded the Youth International Party ("Yippies") and was a member of the Chicago Seven. He was also a leading propone ...

of the Yippies

The Youth International Party (YIP), whose members were commonly called Yippies, was an American youth-oriented radical and countercultural revolutionary offshoot of the free speech and anti-war movements of the late 1960s. It was founded on ...

in 1967, and again in the aftermath of the 1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus maki ...

. The Yippies used the media attention to make a mockery of the proceedings. Rubin came to one session dressed as a Revolutionary War soldier and passed out copies of the United States Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ...

to those in attendance. Rubin then "blew giant gum bubbles, while his co-witnesses taunted the committee with Nazi salute

The Nazi salute, also known as the Hitler salute (german: link=no, Hitlergruß, , Hitler greeting, ; also called by the Nazi Party , 'German greeting', ), or the ''Sieg Heil'' salute, is a gesture that was used as a greeting in Nazi Germany. T ...

s". Rubin attended another session dressed as Santa Claus

Santa Claus, also known as Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas, Saint Nick, Kris Kringle, or simply Santa, is a legendary figure originating in Western Christian culture who is said to bring children gifts during the late evening and overnigh ...

. On another occasion, police stopped Hoffman at the building entrance and arrested him for wearing the United States flag. Hoffman quipped to the press, "I regret that I have but one shirt to give for my country", paraphrasing the last words of revolutionary patriot Nathan Hale

Nathan Hale (June 6, 1755 – September 22, 1776) was an American Patriot, soldier and spy for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He volunteered for an intelligence-gathering mission in New York City but was captured ...

; Rubin, who was wearing a matching Viet Cong

,

, war = the Vietnam War

, image = FNL Flag.svg

, caption = The flag of the Viet Cong, adopted in 1960, is a variation on the flag of North Vietnam. Sometimes the lower stripe was green.

, active ...

flag, shouted that the police were communists for not arresting him as well.

Hearings in August 1966 called to investigate anti-Vietnam War activities were disrupted by hundreds of protesters, many from the Progressive Labor Party. The committee faced witnesses who were openly defiant.

According to ''The Harvard Crimson

''The Harvard Crimson'' is the student newspaper of Harvard University and was founded in 1873. Run entirely by Harvard College undergraduates, it served for many years as the only daily newspaper in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Beginning in the f ...

'':

In an attempt to reinvent itself, the committee was renamed as the Internal Security Committee in 1969.

Termination

The House Committee on Internal Security was formally terminated on January 14, 1975, the day of the opening of the 94th Congress.Charles E. Schamel''Records of the US House of Representatives, Record Group 233: Records of the House Un-American Activities Committee, 1945–1969 (Renamed the) House Internal Security Committee, 1969–1976.''

Washington, DC: Center for Legislative Archives, National Archives and Records, July 1995; p. 4. The committee's files and staff were transferred on that day to the House Judiciary Committee.

Chairmen

Source:Eric Bentley, ''Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts from Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938–1968.'' New York: The Viking Press 1971; pp. 955–957. *Martin Dies Jr.

Martin Dies Jr. (November 5, 1900 – November 14, 1972), also known as Martin Dies Sr., was a Texas politician and a Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives. He was elected as a Democrat to the Seventy-second and after ...

, (D-Tex.), 1938–1944

* Edward J. Hart (D-N.J.), 1945–1946

*J. Parnell Thomas

John Parnell Thomas (January 16, 1895 – November 19, 1970) was a stockbroker and politician. He was elected to seven terms as a U.S. Representative from New Jersey as a Republican. He was later a convicted criminal who served nine months in ...

(R-N.J.), 1947–1948

* John Stephens Wood (D-Ga.), 1949–1953

*Harold H. Velde

Harold Himmel Velde (April 1, 1910 – September 1, 1985) was a Republican American political figure from Illinois. While United States Congressman for Illinois's 18th congressional district he was chairman of the House Un-American Activities ...

(R-Ill.), 1953–1955

* Francis E. Walter (D-Pa.), 1955–1963

*Edwin E. Willis

Edwin Edward Willis (October 2, 1904 – October 24, 1972) was an American politician and attorney from the U.S. state of Louisiana who was affiliated with the Long political faction. A Democrat, he served in the Louisiana State Senate dur ...

(D-La.), 1963–1969

*Richard Howard Ichord Jr.

Richard Howard Ichord Jr. (June 27, 1926 – December 25, 1992) was U.S. representative from Missouri and a significant U.S. anti-Communist political figure. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the last chairman of the House Un-Americ ...

(D-Mo.), 1969–1975

Notable members

* Felix Edward Hébert *Donald L. Jackson

Donald Lester Jackson (January 23, 1910 – May 27, 1981) was a U.S. Representative from California from 1947 to 1961.

Born in Ipswich, Edmunds County, South Dakota, Jackson attended the public schools of South Dakota and California.

Bi ...

* Noah M. Mason

* Karl E. Mundt

* Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was t ...

* John E. Rankin

* Gordon H. Scherer

* Richard B. Vail

* Jerry Voorhis

Horace Jeremiah "Jerry" Voorhis (April 6, 1901 – September 11, 1984) was a Democratic politician and educator from California who served five terms in the United States House of Representatives from 1937 to 1947, representing the 12 ...

See also

*California Senate Factfinding Subcommittee on Un-American Activities California Senate Factfinding Subcommittee on Un-American Activities (CUAC) was established by the California State Legislature in 1941 as the Joint Fact-Finding Committee on UnAmerican Activities. The creation of the new joint committee (with membe ...

* Defending Dissent Foundation

* J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation ...

* Loyalty oath

A loyalty oath is a pledge of allegiance to an organization, institution, or state of which an individual is a member. In the United States, such an oath has often indicated that the affiant has not been a member of a particular organization o ...

* Manning Johnson Manning Rudolph Johnson AKA Manning Johnson and Manning R. Johnson (December 17, 1908 – July 2, 1959)

was a Communist Party USA African-American leader and the party's candidate for U.S. Representative from New York's 22nd congressional district ...

* McCarran Internal Security Act

The Internal Security Act of 1950, (Public Law 81-831), also known as the Subversive Activities Control Act of 1950, the McCarran Act after its principal sponsor Sen. Pat McCarran (D-Nevada), or the Concentration Camp Law, is a United States fede ...

* Edward S. Montgomery

* Mundt–Ferguson Communist Registration Bill

* Mundt–Nixon Bill

The Mundt–Nixon Bill, named after Karl E. Mundt and Richard Nixon, formally the Subversive Activities Control Act, was a proposed law in 1948 that would have required all members of the Communist Party of the United States register with the Atto ...

* Red-baiting

Red-baiting, also known as ''reductio ad Stalinum'' () and red-tagging (in the Philippines), is an intention to discredit the validity of a political opponent and the opponent's logical argument by accusing, denouncing, attacking, or persecuting ...

* Subversive Activities Control Board The Subversive Activities Control Board (SACB) was a United States government committee to investigate Communist infiltration of American society during the 1950s Red Scare. It was the subject of a landmark United States Supreme Court decision of th ...

* ''Wilkinson v. United States

''Wilkinson v. United States'', 365 U.S. 399 (1961), was a court case during the McCarthy Era in which the petitioner, Frank Wilkinson, an administrator with the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles, challenged his conviction under 2 U.S. ...

''

References

Works cited

*Further reading

*Archives

Investigation of un-American propaganda activities in the United States. Hearings before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives (1938–1944), Volumes 1–17 with Appendices.

University of Pennsylvania online gateway to Internet Archive and Hathi Trust.

United States House Committee on Internal Security

University of Pennsylvania online gateway to Internet Archive and Hathi Trust. * Schamel, Gharles E. Inventory of records of the Special Committee on Un-American activities, 1938–1944 (the Dies committee). Center for Legislative Archives,

National Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an " independent federal agency of the United States government within the executive branch", charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It i ...

. Washington, D.C., July 1995.

* Schamel, Gharles E''Records of the House Un-American Activities committee, 1945–1969, renamed the House Internal Security committee, 1969–1976.''

Center for Legislative Archives, National Archives and Records Administration. Washington, D.C., July 1995. *

Books

* * * Caballero, Raymond. ''McCarthyism vs. Clinton Jencks.'' Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019. * * * * * * * *→ *→Articles

**

External links

* *History.House.gov

HUAC – permanent standing House Committee on Un-American Activities

History.House.gov

HUAC – 1948 Alger Hiss-Whittaker Chambers hearing before HUAC

Eastern Carolina University Libraries

The Cold War and Internal Security Collection (CWIS): HUAC

The Spartacus Educational website, UK * House Unamerican Activities Committee (HUAC) Collection: Pamphlets collected by HUAC, many of which the committee deemed "un-American". (4,000 pamphlets). From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

{{Authority control 1938 establishments in Washington, D.C. 1975 disestablishments in Washington, D.C. Anti-communist organizations in the United States Cold War history of the United States Un-American activities McCarthyism Political repression in the United States Government agencies established in 1938