History Of Zaporizhzhia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Zaporizhzhia shows the origins of

Archaeological finds show that about two or three thousand years ago

Archaeological finds show that about two or three thousand years ago

История города Александровска, (Екатеринославской губ.) в связи с историей возникновения крепостей Днепровской линии 1770–1806 г.

– Екатеринослав: Типография Губернского Земства, 1905. – 176 с. It is uncertain in whose honour the fortress was named. Some believe that it was

In 1789,

In 1789,

by L. Adelberg (–ê–¥–µ–ª—å–±–µ—Ä–≥ –õ), pub RA Tandem st, Zaporizhzhia, 2005. In 1916, during

, accessed 11 April 2011.

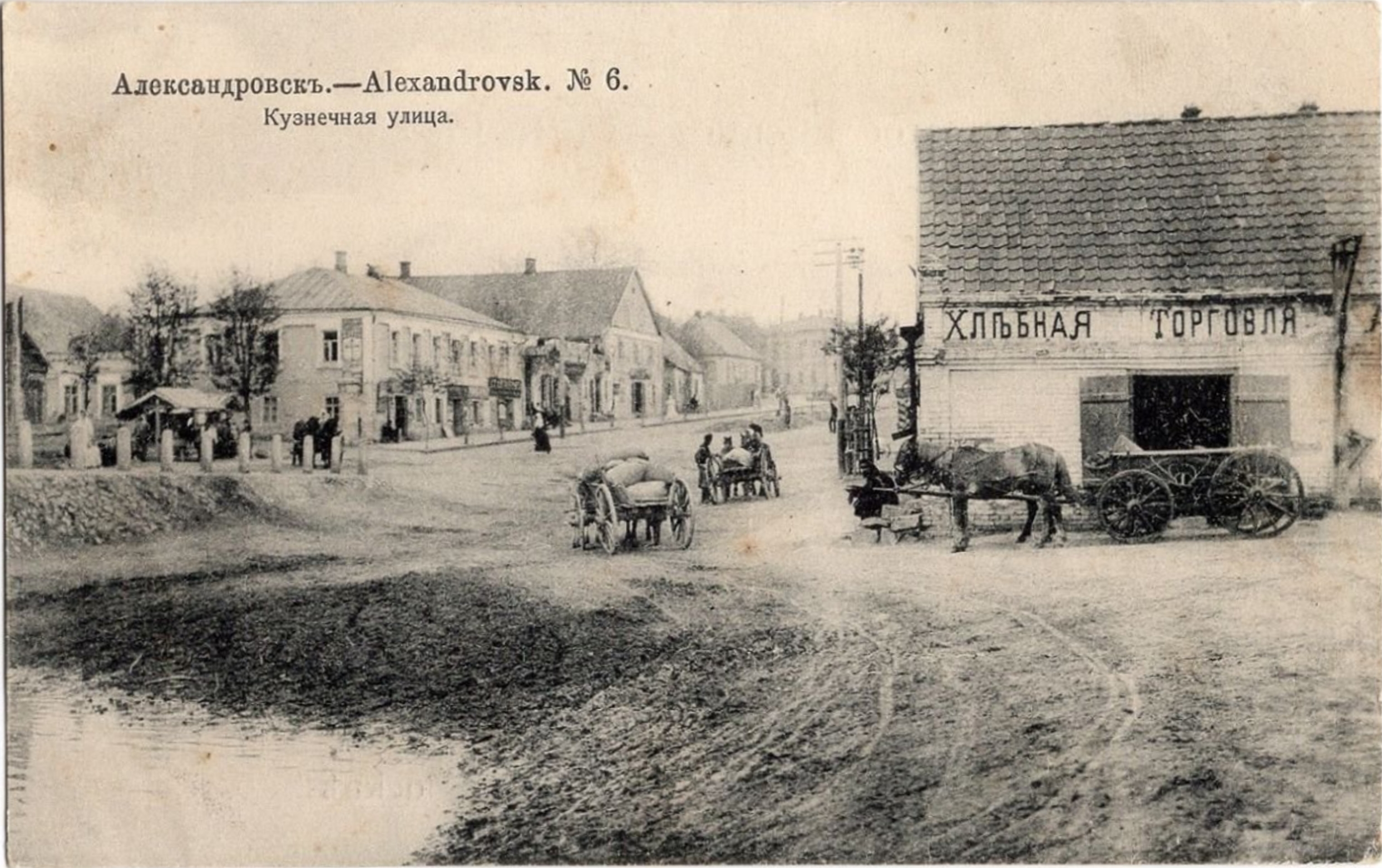

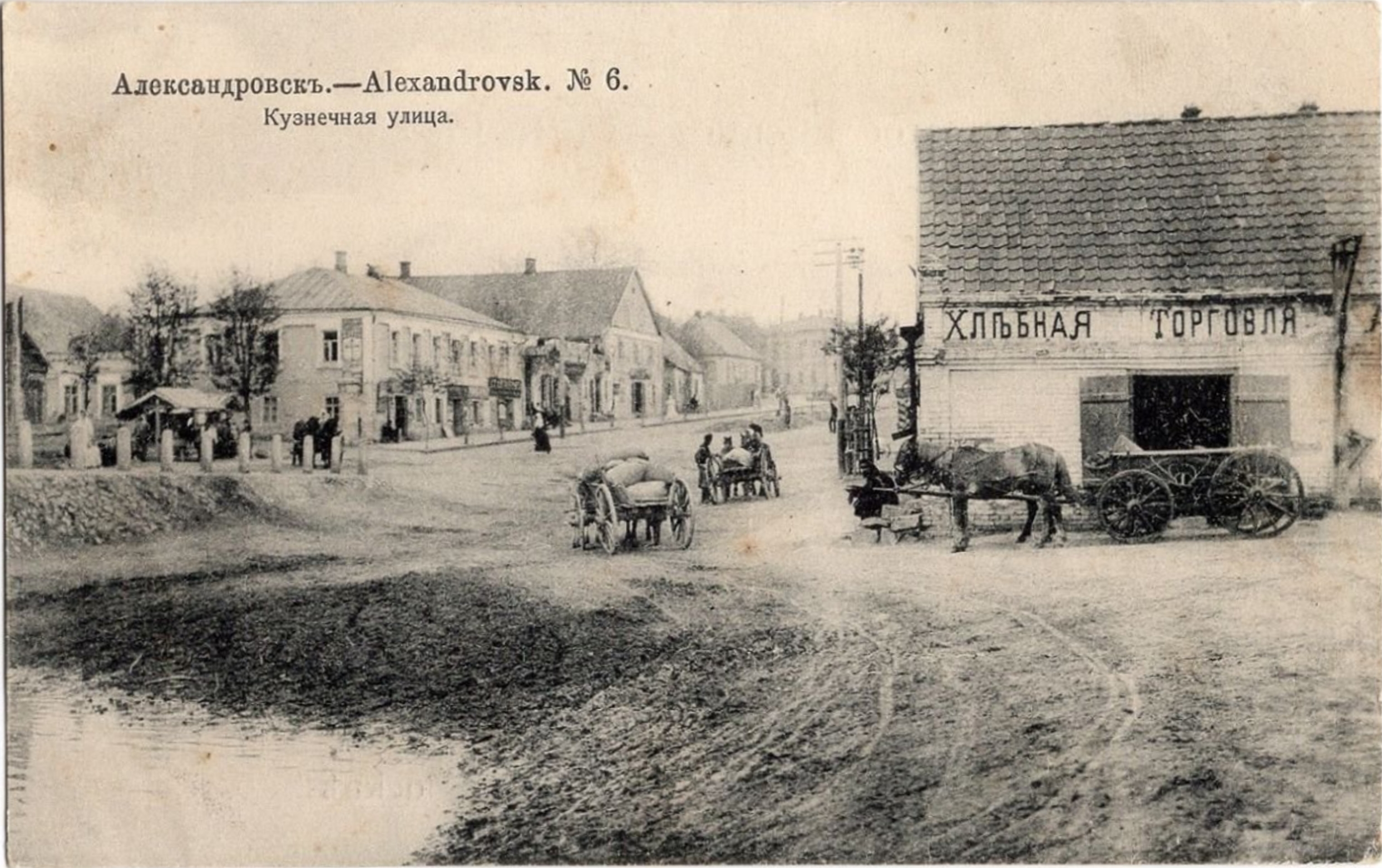

At the beginning of 20th century, Zaporizhzhia was a small unremarkable rural town of the Russian Empire, which acquired industrial importance during the industrialization carried out by the Soviet government in the 1920s and 1930s.

In 1929–1932, a master plan for city construction was developed. At from the old town Alexandrovsk at the narrowest part of the Dnieper river was planned to build the hydroelectric power station, the most powerful in Europe at that time. Close to the station should be constructed the new modern city and a giant steel and aluminum plants. Later the station was named " DnieproHES", the steel plant – " Zaporizhstal'" (Zaporizhzhia Steel Plant), and the new part of the city – "Sotsgorod". (Socialist city)

Production of the aluminum plant ("DAZ" – Dnieper Aluminium Plant) according to the plan should exceed the overall production of the aluminum all over Europe at that time.

(GIPROMEZ) developed a project of creation of the Dnieper Industrial Complex. GIPROMEZ consulted with various companies, including the of Chicago (USA), which participated in the design and construction of the blast furnaces.

In the 1930s the American United Engineering and Foundry Company built a

At the beginning of 20th century, Zaporizhzhia was a small unremarkable rural town of the Russian Empire, which acquired industrial importance during the industrialization carried out by the Soviet government in the 1920s and 1930s.

In 1929–1932, a master plan for city construction was developed. At from the old town Alexandrovsk at the narrowest part of the Dnieper river was planned to build the hydroelectric power station, the most powerful in Europe at that time. Close to the station should be constructed the new modern city and a giant steel and aluminum plants. Later the station was named " DnieproHES", the steel plant – " Zaporizhstal'" (Zaporizhzhia Steel Plant), and the new part of the city – "Sotsgorod". (Socialist city)

Production of the aluminum plant ("DAZ" – Dnieper Aluminium Plant) according to the plan should exceed the overall production of the aluminum all over Europe at that time.

(GIPROMEZ) developed a project of creation of the Dnieper Industrial Complex. GIPROMEZ consulted with various companies, including the of Chicago (USA), which participated in the design and construction of the blast furnaces.

In the 1930s the American United Engineering and Foundry Company built a

Zaporizhzhia was taken on 3 October 1941. The German occupation of Zaporizhzhia lasted 2 years and 10 days. During this time the Germans shot over 35,000 people, and sent 58,000 people to Germany as forced labour. The Germans used forced labor (mostly

by Dmitri Danilovich Lelyushenko (–õ–µ–ª—é—à–µ–Ω–∫–æ –î–º–∏—Ç—Ä–æ –î–∞–Ω–∏–ª–æ–≤–∏—á), pub Nauka, Moscow, 1987, chapter 4. "laying down a barrage of shellfire bigger than anything... seen to date (it was here that entire 'divisions' of artillery appeared for the first time) and throwing in no fewer than ten divisions strongly supported by armour". The Red Army broke into the bridgehead, forcing the Germans to abandon it on 14 October. The retreating Germans destroyed the Zaporizhstal steel plant almost completely; they demolished the big railway bridge again, and demolished the turbine building and damaged 32 of the 49 bays of the Dnieper hydro-electric dam. The city has a street between Voznesenskyi and Oleksandrivskyi Districts and a memorial in Oleksandrivskyi District dedicated to

Zaporizhzhia

Zaporizhzhia ( uk, –ó–∞–ø–æ—Ä—ñ–∂–∂—è) or Zaporozhye (russian: –ó–∞–ø–æ—Ä–æ–∂—å–µ) is a city in southeast Ukraine, situated on the banks of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. It is the Capital city, administrative centre of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Zapor ...

, a city located in modern day Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

.

Pre-foundation history

Archaeological finds show that about two or three thousand years ago

Archaeological finds show that about two or three thousand years ago Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved f ...

lived around the modern city. Later, Khazars

The Khazars ; he, ◊õ÷º◊ï÷º◊ñ÷∏◊®÷¥◊ô◊ù, K≈´zƒÅrƒ´m; la, Gazari, or ; zh, Á™ÅÂé•Êõ∑Ëñ© ; Á™ÅÂé•ÂèØËñ© ''T≈´ju√© Kƒõs√Ý'', () were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that in the late 6th-century CE established a major commercial empire coverin ...

, Pechenegs

The Pechenegs () or Patzinaks tr, Pe√ßenek(ler), Middle Turkic: , ro, Pecenegi, russian: –ü–µ—á–µ–Ω–µ–≥(–∏), uk, –ü–µ—á–µ–Ω—ñ–≥(–∏), hu, Beseny≈ë(k), gr, ŒÝŒ±œÑŒ∂ŒπŒΩŒ¨Œ∫ŒøŒπ, ŒÝŒµœÑœÉŒµŒΩŒ≠Œ≥ŒøŒπ, ŒÝŒ±œÑŒ∂ŒπŒΩŒ±Œ∫ŒØœÑŒ±Œπ, ka, ·Éû·Éê·É ...

, Kuman, Tatars

The Tatars ()Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

and in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

dwelt there. The trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks

The trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks was a medieval trade route that connected Scandinavia, Kievan Rus' and the Eastern Roman Empire. The route allowed merchants along its length to establish a direct prosperous trade with the Empir ...

passed through the island of Khortytsia

Khortytsia ( uk, –•–æ—Ä—Ç–∏—Ü—è, Hortycja, translit-std=ISO, ) is the largest island in the Dnieper river, and is long and up to wide. The island forms part of the Khortytsia National Park. This historic site is located within the city limit ...

. These territories were called the "Wild Fields

The Wild Fields ( uk, –î–∏–∫–µ –ü–æ–ª–µ, translit=Dyke Pole, russian: –î–∏–∫–æ–µ –ü–æ–ª–µ, translit=Dikoye Polye, pl, Dzikie pola, lt, Dykra, la, Loca deserta or , also translated as "the wilderness") is a historical term used in the Polish ...

", because they were not under the control of any state (it was the land between the highly eroded borders of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

, the Grand Duchy of Moscow

The Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovite Russia, Muscovite Rus' or Grand Principality of Moscow (russian: –í–µ–ª–∏–∫–æ–µ –∫–Ω—è–∂–µ—Å—Ç–≤–æ –ú–æ—Å–∫–æ–≤—Å–∫–æ–µ, Velikoye knyazhestvo Moskovskoye; also known in English simply as Muscovy from the Lati ...

, and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

).

In 1552, Dmytro Vyshnevetsky

Dmytro Ivanovych Vyshnevetsky ( uk, Дмитро Іванович Вишневе́цький; russian: Дмитрий Иванович Вишневе́цкий; pl, Dymitr Wiśniowiecki) was a magnate of Ruthenian (Ukrainian) origin and an organi ...

erected wood-earth fortifications on the small island Little Khortytsia which is near the western shore of Khortytsia

Khortytsia ( uk, –•–æ—Ä—Ç–∏—Ü—è, Hortycja, translit-std=ISO, ) is the largest island in the Dnieper river, and is long and up to wide. The island forms part of the Khortytsia National Park. This historic site is located within the city limit ...

island. Archeologists consider these fortifications to be a prototype for the Zaporizhzhian Sich — the stronghold of the paramilitary peasant regiments of Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

.

Russian Empire (1654–1917)

Foundation of Zaporizhzhia

In 1770 the fortress of Aleksandrovskaya () was erected and is considered to be the year of the foundation of Zaporizhzhia. As a part of the Dnieper Defence Line the fortress protected the southern territories ofRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

from Crimean Tatar invasions.Я. П. НовицкийИстория города Александровска, (Екатеринославской губ.) в связи с историей возникновения крепостей Днепровской линии 1770–1806 г.

– Екатеринослав: Типография Губернского Земства, 1905. – 176 с. It is uncertain in whose honour the fortress was named. Some believe that it was

Alexander Mikhailovich Golitsyn

Alexander Mikhailovich Golitsyn (17 November 1718 – 8 October 1783) was a Russian prince of the House of Golitsyn and field marshal. He was the General Governor of Saint Petersburg Governorate in 1780 to 1783.

Life

Early life

As was tr ...

, the general who served Catherine the Great.Pospelov, pp. 25–26 Other possibilities are Prince Alexander Vyazemsky

Prince Alexander Alekseevich Vyazemsky (russian: Александр Алексеевич Вяземский; 14 August 1727 – 20 January 1793) was one of the trusted dignitaries of Catherine the Great, Catherine II, who, as the Prosecutor general ...

or Alexander Rumyantsev Alexander Rumyantsev or Aleksander Rumyantsev may refer to:

*Alexander Rumyantsev (nobleman)

Count Alexander Ivanovich Rumyantsev (russian: –ê–ª–µ–∫—Å–∞–Ω–¥—Ä –ò–≤–∞–Ω–æ–≤–∏—á –Ý—É–º—è–Ω—Ü–µ–≤) (1677‚Äì1749) was an assistant of Peter the Great ...

.

In 1775, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

signed the Küçük Kaynarca peace treaty, according to which the southern lands of the Russian Plain and Crimean peninsula became Russian-governed territories. As a result, the Aleksandrovskaya Fortress lost its military significance and converted into a small provincial rural town, known from 1806 under the name Alexandrovsk ().

Mennonite settlers

In 1789,

In 1789, Mennonites

Mennonites are groups of Anabaptist Christian church communities of denominations. The name is derived from the founder of the movement, Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland. Through his writings about Reformed Christianity during the Radic ...

from the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

city of Danzig (Gdańsk) accepted the invitation from Catherine the Great to settle several colonies in the area of the modern city. The island of Khortytsia

Khortytsia ( uk, –•–æ—Ä—Ç–∏—Ü—è, Hortycja, translit-std=ISO, ) is the largest island in the Dnieper river, and is long and up to wide. The island forms part of the Khortytsia National Park. This historic site is located within the city limit ...

was gifted to them for "perpetual possession" by the Russian government. In 1914, the Mennonites sold the island back to the city. The Mennonites built mills and agricultural factories in Alexandrovsk.

During the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

and especially by World War II most of the Mennonites had fled to North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

as well as being forcefully relocated to eastern Russia. At present, few Mennonites live in Zaporizhzhia, although in the area many industrial buildings and houses built by Mennonites are preserved.

The ferry

In 1829, it was proposed to build acable ferry

A cable ferry (including the terms chain ferry, swing ferry, floating bridge, or punt) is a ferry that is guided (and in many cases propelled) across a river or large body of water by cables connected to both shores. Early cable ferries often ...

across the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and B ...

. The ferry could carry a dozen carts. The project was approved by Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

and later was used in other parts of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

. In 1904 the ferry was replaced by the Kichkas Bridge (see next section), which was built in the narrowest part of the river called "Wolf Throat", near to the northern part of the Khortytsia Island

Khortytsia ( uk, –•–æ—Ä—Ç–∏—Ü—è, Hortycja, translit-std=ISO, ) is the largest island in the Dnieper river, and is long and up to wide. The island forms part of the Khortytsia National Park. This historic site is located within the city limit ...

.

Establishment of railway and Kichkas Bridge

The first railway bridge over the Dnieper was the Kichkas () Bridge, which was designed by Y.D. Proskuryakov and E. O. Paton. The construction works were supervised by F. W. Lat. The total bridge length was . It crossed the river with a single span of . The upper tier carried a double-track railway line, whilst the lower tier was used for other types of vehicles; both sides of the bridge were assigned as footpaths. It was built at the narrowest part of the Dnieper river known as ''Wolf Throat''. Construction started in 1900, and it opened for pedestrian traffic in 1902. The official opening of the bridge was 17 April 1904, though railway traffic on the bridge only commenced on 22 January 1908. The opening of the Kichkas Bridge led to the industrial growth of Alexandrovsk.''The bridges of Zaporizhzhia'' (–ú–æ—Å—Ç—ã –ó–∞–ø–æ—Ä–æ–∂—å—è)by L. Adelberg (–ê–¥–µ–ª—å–±–µ—Ä–≥ –õ), pub RA Tandem st, Zaporizhzhia, 2005. In 1916, during

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the aviation engines plant of DEKA Stock Association (today better known as the Motor Sich

The Motor Sich Joint Stock Company ( uk, АТ «Мотор Січ») is a Ukrainian aircraft engine manufacturer headquartered in Zaporizhzhia. The company manufactures engines for airplanes and helicopters, and also industrial marine gas turbi ...

) was transferred from Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, –°–∞–Ω–∫—Ç-–ü–µ—Ç–µ—Ä–±—É—Ä–≥, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=Ààsankt p ≤…™t ≤…™rÀàburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914‚Äì1924) and later Leningrad (1924‚Äì1991), i ...

.''Official Portal Zaporizhzhia city authorities, History'' (–û—Ñ—ñ—Ü—ñ–π–Ω–∏–π –ø–æ—Ä—Ç–∞–ª, –ó–∞–ø–æ—Ä—ñ–∑—å–∫–æ—ó –º—ñ—Å—å–∫–æ—ó –≤–ª–∞–¥–∏, –Ü—Å—Ç–æ—Ä—ñ—è –º—ñ—Å—Ç–∞), accessed 11 April 2011.

Civil war (1917–1921)

The Kichkas Bridge was of strategic importance during theRussian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

, and carried troops, ammunition, the wounded and medical supplies. Because of this bridge, Alexandrovsk and its environs was the scene of fierce fighting from 1918 to 1921 between the Red Army and the White armies of Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

and Wrangel, Petliura

Symon Vasylyovych Petliura ( uk, Си́мон Васи́льович Петлю́ра; – May 25, 1926) was a Ukrainian politician and journalist. He became the Supreme Commander of the Ukrainian Army and the President of the Ukrainian People' ...

's Ukrainian People's Army

The Ukrainian People's Army ( uk, –ê—Ä–º—ñ—è –£–∫—Ä–∞—ó–Ω—Å—å–∫–æ—ó –ù–∞—Ä–æ–¥–Ω–æ—ó –Ý–µ—Å–ø—É–±–ª—ñ–∫–∏), also known as the Ukrainian National Army (UNA) or as a derogatory term of Russian and Soviet historiography Petliurovtsy ( uk, –ü–µ—Ç– ...

of the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

and German-Austrian troops, and after their defeat, the struggle with insurgents led by Hryhoriv and Makhno. The bridge was damaged a number of times. The most serious damage was inflicted by Makhno's troops when they retreated from Alexandrovsk in 1920 and blew a gap in the middle of the bridge.

People's Commissar of Railways Dzerzhinsky of the Bolshevik government ordered the repair of the bridge. The metallurgical plant of the Bryansk joint-stock company (present day Dniprovsky Metallurgical Plant

Dniprovsky Metallurgical Plant or Dnipro Metallurgical Plant is a private joint-stock company and the oldest metallurgical enterprise in the city of Dnipro. It is located in the Novokodatskyi District, in Dnipro Raion. It was founded in 1885.

Unt ...

) in Katerynoslav (today Dnipro

Dnipro, previously called Dnipropetrovsk from 1926 until May 2016, is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper Rive ...

) built a replacement section. The Kichkas Bridge reopened on 14 September 1921. On 19 October 1921, the Soviet Council of Labor and Defense (chaired by Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

) awarded the Yekaterininsky railroad the Order of the Red Banner of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic for the early restoration of the Kichkas Bridge.

In the time of Soviet Ukraine as a part of the USSR (1922–1991)

Industrialization in the 1920 – 1930s

At the beginning of 20th century, Zaporizhzhia was a small unremarkable rural town of the Russian Empire, which acquired industrial importance during the industrialization carried out by the Soviet government in the 1920s and 1930s.

In 1929–1932, a master plan for city construction was developed. At from the old town Alexandrovsk at the narrowest part of the Dnieper river was planned to build the hydroelectric power station, the most powerful in Europe at that time. Close to the station should be constructed the new modern city and a giant steel and aluminum plants. Later the station was named " DnieproHES", the steel plant – " Zaporizhstal'" (Zaporizhzhia Steel Plant), and the new part of the city – "Sotsgorod". (Socialist city)

Production of the aluminum plant ("DAZ" – Dnieper Aluminium Plant) according to the plan should exceed the overall production of the aluminum all over Europe at that time.

(GIPROMEZ) developed a project of creation of the Dnieper Industrial Complex. GIPROMEZ consulted with various companies, including the of Chicago (USA), which participated in the design and construction of the blast furnaces.

In the 1930s the American United Engineering and Foundry Company built a

At the beginning of 20th century, Zaporizhzhia was a small unremarkable rural town of the Russian Empire, which acquired industrial importance during the industrialization carried out by the Soviet government in the 1920s and 1930s.

In 1929–1932, a master plan for city construction was developed. At from the old town Alexandrovsk at the narrowest part of the Dnieper river was planned to build the hydroelectric power station, the most powerful in Europe at that time. Close to the station should be constructed the new modern city and a giant steel and aluminum plants. Later the station was named " DnieproHES", the steel plant – " Zaporizhstal'" (Zaporizhzhia Steel Plant), and the new part of the city – "Sotsgorod". (Socialist city)

Production of the aluminum plant ("DAZ" – Dnieper Aluminium Plant) according to the plan should exceed the overall production of the aluminum all over Europe at that time.

(GIPROMEZ) developed a project of creation of the Dnieper Industrial Complex. GIPROMEZ consulted with various companies, including the of Chicago (USA), which participated in the design and construction of the blast furnaces.

In the 1930s the American United Engineering and Foundry Company built a strip mill The strip mill was a major innovation in steelmaking, with the first being erected at Ashland, Kentucky in 1923. This provided a continuous process, cutting out the need to pass the plates over the rolls and to double them, as in a pack mill. At the ...

, which produced hot and cold rolling steel strip. This was a copy of the Ford River Rouge steel mill. Annual capacity of the mill reached . Strip width was .''The Soviet economy and the Red Army, 1930–1945'', by Walter Scott Dunn, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995 , page 13. There was a second section that used a Soviet copy of the Demag AG strip mill that produced wide strip steel.

The hydro-electric dam, DniproHES

The turning point in the history of the city was the construction of the hydro-electric dam (DniproHES), which began in 1927 and completed in 1932. The principal designer of the project was I. G. Alexandrov, the construction manager – A. V. Vinter, the chief architect – V. A. Vesnin and the chief American advisor – the colonel Hugh Cooper. The installed generating capacity was 560 megawatts, the length of a convex dam was , the width was , the height was . Eight turbines and five electrical generators were designed and manufactured in the United States. The other three generators were made at the Leningrad factoryElectrosila

OJSC Power Machines ( translit. Siloviye Mashiny abbreviated as Silmash, russian: ОАО «Силовы́е маши́ны») is a Russian energy systems machine-building company founded in 2000. It is headquartered in Saint Petersburg.

Power M ...

.

After commissioning the Dnieper rapids were flooded, and the river became navigable from Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

to Kherson

Kherson (, ) is a port city of Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers appr ...

. In 1980 a new generator building was built, and the station power was increased to 1,388 megawatts

The city of Socialism (Sotsgorod)

Between the hydroelectric dam and industrial area in from the centre of the old Alexandrovsk was established residential district No. 6, which was named "Sotsgorod". In 20th doctrinaire idealistic enthusiasm of the architects was reflected in the intense debate about the habitation of the socialist community. The architects believed that by using new architectural forms they could create a new society. District No. 6 was one of the few implementations of urban development concepts. The construction of the district began in 1929 and finished in 1932. The main idea guiding the architects was the creation of a garden city, a city of the future. Multi-storey houses (not more than 4 floors) with large, roomy apartments were built in Sotsgorod with spacious yards planted with grass and trees around the buildings.Nikolai Kolli

Nikolai Dzhemsovich (Yakovlevich) Kolli (russian: Николай Джемсович (Яковлевич) Колли; Р3 December 1966) was a Soviet and Russian Modernist—Constructivist architecture, Constructivist architect, architectu ...

, V. A. Vesnin, , V. G. Lavrov and others designed the DniproHES and SotsGorod. Le Corbusier

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (6 October 188727 August 1965), known as Le Corbusier ( , , ), was a Swiss-French architect, designer, painter, urban planner, writer, and one of the pioneers of what is now regarded as modern architecture. He was ...

visited the town few times in the 1930s. The architects used the ideas of the constructivist architecture

Constructivist architecture was a constructivist style of modern architecture that flourished in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and early 1930s. Abstract and austere, the movement aimed to reflect modern industrial society and urban space, while ...

.

The ring house the building No. 31 at Independent Ukraine Street (formerly – 40 years of Soviet Ukraine Street) was designed by V. G. Lavrov. Families of the Soviet and American engineers, advisors, and industry bosses lived in Sotsgorod at that time. However, the most of the workers during the construction of the hydro-power station and plants lived in dugouts at No. 15 and Aluminum districts. The south border of the Sotsgorog is limited by Verkhnya Ulitsa (Upper Street) and north border – by the hydroelectric power station. At the intersection between Sobornyi Avenue and Verkhnya Street, architect I.L. Kosliner set a tower with seven stories. This tower supposedly indicates the entrance gate of Sotsgorod from the south (from Alexandrovsk). Closer to the dam, the second tower was raised (architects I.L. Kosliner and L.Ya. Gershovich). Both towers point out a straight line of the central street of the district.

The names of the streets have changed several times. The original name of Metallurgist Avenue was Enthusiasts Alley. This road leads to the factories. At that time, they believed that people going to the plant had only positive feelings like joy, pride, and enthusiasm. At the end of the road stands a 1963 sculpture of the metallurgist by sculptor Ivan Nosenko. During the German occupation, it was named Shevchenko

Shevchenko (alternative spellings Schevchenko, ≈Ýevƒçenko, Shevcenko, Szewczenko, Chevchenko; ua , –®–µ–≤—á–µ–Ω–∫–æ), a family name of Ukrainian origin. It is derived from the Ukrainian word ''shvets'' ( uk, —à–≤–µ—Ü—å), " cobbler/shoemaker", and ...

Avenue. Later it was renamed Stalin Avenue; and after his death, it got the present name of Metallurgist Avenue. Sobornyi Avenue originally had the name Libkhnet Avenue. "Forty Years of Soviet Ukraine" Street was once called Sovnarkomovska Street and during the German occupation Hitler Alley.

Big Zaporizhzhia

District No. 6 is a small part of the global project called ''Big Zaporizhzhia''. This project was designed for the city, to enable a half-million people to live in seven different areas: Voznesenka, Baburka, Kichkas, Alexandrovsk, Pavlo-Kichkas, Island Khortitsa, and (omitted). Each district must be independent of the others and yet part of –∞ united city. The city line should be stretched along the banks of the Dnieper River for .

Dnieper railway bridges

The location of the Kichkas Bridge was in the flood zone upstream of the hydroelectric dam. Initially, it was planned to disassemble it and rebuild it in another location. But expert advice was that this was not cost-effective as it was cheaper to build a new bridge. The building of the hydroelectric dam meant that a new bridge was required to take the railway over the Dnieper. Instead of having a single bridge, as before, it was decided to take the railway over the islandKhortytsia

Khortytsia ( uk, –•–æ—Ä—Ç–∏—Ü—è, Hortycja, translit-std=ISO, ) is the largest island in the Dnieper river, and is long and up to wide. The island forms part of the Khortytsia National Park. This historic site is located within the city limit ...

. The wide part of the river between Khortytsia and the city is known as the New Dnieper, and the narrower part between Khortytsia and the suburbs on the right bank of the river is known as the Old Dnieper. The New Dnieper was crossed by a three-arch two-tier bridge. Each of the arches spans . When the approach spans are included the total length is weighing .

The Old Dnieper was crossed by a single-span arch bridge with a total length of ; the arch spans of and was then the largest single-span bridge in Europe. This bridge weighed . Both bridges were designed by Professor Streletsky. They were made of riveted steel, and had two tiers: the upper tier for rail traffic and the lower tier for road traffic and pedestrians. They were assembled by a combination of Czechoslovakian and Soviet workers under the direction of a Soviet engineer named Konstantinov. The arches are steel made by the Vitkovetskom steel plant in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, other steelwork was made at the Dnipropetrovsk Metallurgical Plant. The new bridges opened on 6 November 1931. The Kichkas Bridge was demolished afterwards.

World War II (1941–1945)

German occupation

The War between the USSR and Nazi Germany began on 22 June 1941. After the outbreak of the war, theSoviet government

The Government of the Soviet Union ( rus, –ü—Ä–∞–≤–∏ÃÅ—Ç–µ–ª—å—Å—Ç–≤–æ –°–°–°–Ý, p=pr…êÀàv ≤it ≤…™l ≤stv…ô …õs …õs …õs Àà…õr, r=Prav√≠telstvo SSSR, lang=no), formally the All-Union Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, commonly ab ...

started the evacuation of the industrial equipment from the city to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, –°–∏–±–∏—Ä—å, r=Sibir', p=s ≤…™Ààb ≤ir ≤, a=Ru-–°–∏–±–∏—Ä—å.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

. The Soviet security forces NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

shot political prisoners in the city. On 18 August 1941, elements of the German 1st Panzergruppe reached the outskirts of Zaporizhzhia on the right bank and seized the island Khortytsia.

The Red Army blew a 120m x 10m hole in the Dnieper hydroelectric dam (DniproHES) at 16:00 on 18 August 1941, producing a flood wave that swept from Zaporizhzhia to Nikopol, killing local residents as well as soldiers from both sides. "Since no official death toll was released at the time, the estimated number of victims varies widely. Most historians put it at between 20,000 and 100,000, based on the number of people then living in the flooded areas". After two days, the city defenders received reinforcements, and held the left bank of the river for 45 days. During this time people dismantled heavy machinery, packed and loaded them on the railway platform, marked and accounted for with wiring diagrams. Zaporizhstal alone exported 9,600 railway cars with the equipment.The Great Patriotic War on the territory of Zaporizhzhia (–í–µ–ª–∏–∫–∞—è –û—Ç–µ—á–µ—Å—Ç–≤–µ–Ω–Ω–∞—è –≤–æ–π–Ω–∞ –Ω–∞ —Ç–µ—Ä—Ä–∏—Ç–æ—Ä–∏–∏ –ó–∞–ø–æ—Ä–æ–∂—å—è)Zaporizhzhia was taken on 3 October 1941. The German occupation of Zaporizhzhia lasted 2 years and 10 days. During this time the Germans shot over 35,000 people, and sent 58,000 people to Germany as forced labour. The Germans used forced labor (mostly

POW

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war ...

s) to try to restore the Dnieper hydroelectric dam and the steelworks. Local citizens established an underground resistance organization in spring 1942.

The Krivoy Rog

Kryvyi Rih ( uk, –ö—Ä–∏–≤–∏ÃÅ–π –Ý—ñ–≥ , lit. "Curved Bend" or "Crooked Horn"), also known as Krivoy Rog (Russian: –ö—Ä–∏–≤–æ–π –Ý–æ–≥) is the largest city in central Ukraine, the 7th most populous city in Ukraine and the 2nd largest by area. Kr ...

– Stalingrad

Volgograd ( rus, Волгогра́д, a=ru-Volgograd.ogg, p=vəɫɡɐˈɡrat), geographical renaming, formerly Tsaritsyn (russian: Цари́цын, Tsarítsyn, label=none; ) (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (russian: Сталингра́д, Stal ...

and Moscow – Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

railway lines through Zaporizhzhia were important supply lines for the Germans in 1942–43, but the big three-arch Dnieper railway bridge at Zaporizhzhia was blown up by the retreating Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: –Ý–∞–±–æÃÅ—á–µ-–∫—Ä–µ—Å—Ç—å—èÃÅ–Ω—Å–∫–∞—è –ö—Ä–∞ÃÅ—Å–Ω–∞—è –∞—Ä–º–∏—è),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

on 18 August 1941, with further demolition work done during September 1941. and the Germans did not bring it back into operation until summer 1943.'' Lost Victories'', by Field Marshal Eric von Manstein, pdf version p263.

When the Germans reformed Army Group South

Army Group South (german: Heeresgruppe Süd) was the name of three German Army Groups during World War II.

It was first used in the 1939 September Campaign, along with Army Group North to invade Poland. In the invasion of Poland Army Group Sou ...

in February 1943, it had its headquarters in Zaporizhzhia. The loss of Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, wikt:Харків, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine.Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

to fly to this headquarters on 17 February 1943, where he stayed until 19 February and met the army group commander Field Marshal Erich von Manstein

Fritz Erich Georg Eduard von Manstein (born Fritz Erich Georg Eduard von Lewinski; 24 November 1887 – 9 June 1973) was a German Field Marshal of the ''Wehrmacht'' during the Second World War, who was subsequently convicted of war crimes and ...

, and was persuaded to allow Army Group South to fight a mobile defence that quickly led to much of the lost ground being recaptured by the Germans in the Third Battle of Kharkov

The Third Battle of Kharkov was a series of battles on the Eastern Front of World War II, undertaken by Army Group South of Nazi Germany against the Soviet Red Army, around the city of Kharkov between 19 February and 15 March 1943. Known to ...

. Hitler visited the headquarters in Zaporizhzhia again on 10 March 1943, where he was briefed by von Manstein and his air force counterpart Field Marshal Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen

Wolfram Karl Ludwig Moritz Hermann Freiherr von Richthofen (10 October 1895 – 12 July 1945) was a German World War I flying ace who rose to the rank of ''Generalfeldmarschall'' in the Luftwaffe during World War II.

Born in 1895 into a fa ...

. Hitler visited the headquarters at Zaporizhzhia for the last time on 8 September 1943. In mid-September 1943 the Army Group moved its headquarters from Zaporizhzhia to Kirovograd (now called Kropyvnytskyi).''Lost Victories'', by Field Marshal Eric von Manstein, says that the Germans finished repairing the railway bridge only a few months before they lost the city in October 1943.

Both the big railway bridge over the New Dnieper and the smaller one over the Old Dnieper were damaged in an air raid by a group of eight Ilyushin Il-2

The Ilyushin Il-2 (Russian: Илью́шин Ил-2) is a ground-attack plane that was produced by the Soviet Union in large numbers during the Second World War. The word ''shturmovík'' (Cyrillic: штурмовик), the generic Russian term ...

s led by Lieutenant A Usmanov on 21 September 1943.

Liberation

In mid-August 1943, the Germans started building the Panther-Wotan defence line along theDnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and B ...

from Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

to Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

, and retreated back to it in September 1943. The Germans held the city as a bridgehead over the Dnieper with elements of 40th Panzer and 17th Corps. The Soviet Southwestern Front, commanded by Army General

Army general is the highest ranked general officer in many countries that use the General officer#French (Revolutionary) system, French Revolutionary System.„ÄÄ

In countries that adopt the general officer four rank system, it is rank of genera ...

Rodion Malinovsky

Rodion Yakovlevich Malinovsky (russian: –Ý–æ–¥–∏–æÃÅ–Ω –ØÃÅ–∫–æ–≤–ª–µ–≤–∏—á –ú–∞–ª–∏–Ω–æÃÅ–≤—Å–∫–∏–π, ukr, –Ý–æ–¥—ñ–æÃÅ–Ω –ØÃÅ–∫–æ–≤–∏—á –ú–∞–ª–∏–Ω–æÃÅ–≤—Å—å–∫–∏–π ; ‚Äì 31 March 1967) was a Soviet military commander. He was Marshal of the Sovi ...

, attacked the city on 10 October 1943. When the defenders succeeding in holding up the attacks, the Red Army reinforced its troops and launched a surprise night attack at 22:00 on 13 October,''Moscow-Stalingrad-Berlin-Prague, Memories of Army Commander'' ("–ú–æ—Å–∫–≤–∞-–°—Ç–∞–ª—ñ–Ω–≥—Ä–∞–¥-–ë–µ—Ä–ª—ñ–Ω-–ü—Ä–∞–≥–∞". –ó–∞–ø–∏—Å–∫–∏ –∫–æ–º–∞–Ω–¥–∞—Ä–º–∞)by Dmitri Danilovich Lelyushenko (–õ–µ–ª—é—à–µ–Ω–∫–æ –î–º–∏—Ç—Ä–æ –î–∞–Ω–∏–ª–æ–≤–∏—á), pub Nauka, Moscow, 1987, chapter 4. "laying down a barrage of shellfire bigger than anything... seen to date (it was here that entire 'divisions' of artillery appeared for the first time) and throwing in no fewer than ten divisions strongly supported by armour". The Red Army broke into the bridgehead, forcing the Germans to abandon it on 14 October. The retreating Germans destroyed the Zaporizhstal steel plant almost completely; they demolished the big railway bridge again, and demolished the turbine building and damaged 32 of the 49 bays of the Dnieper hydro-electric dam. The city has a street between Voznesenskyi and Oleksandrivskyi Districts and a memorial in Oleksandrivskyi District dedicated to

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: –Ý–∞–±–æÃÅ—á–µ-–∫—Ä–µ—Å—Ç—å—èÃÅ–Ω—Å–∫–∞—è –ö—Ä–∞ÃÅ—Å–Ω–∞—è –∞—Ä–º–∏—è),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

who commanded the first tank to enter Zaporizhzhia; he and his crew were killed in the battle for the city.

The Red Army did not recapture the parts of the city on the right bank until 1944.

The rebuilding of the Dnieper hydro-electric dam commenced on 7 July 1944. The first electricity was produced from the restored dam on 3 March 1947.

Contemporary (1991–present time)

New bridges across Dnieper

The vehicular connection between the right shore city districts and city center via theZaporizhzhia Arch Bridge

Zaporizhzhia Arch Bridge ( uk, –ê—Ä–∫–æ–≤–∏–π –º—ñ—Å—Ç —É –ó–∞–ø–æ—Ä—ñ–∂–∂—ñ) is the longest arch bridge in Ukraine.Preobrazhensky Bridge was heavily congested by the late nineties. In 2004, construction began on new bridges across the Dnieper called the

Poroshenko signs laws on denouncing Communist, Nazi regimes

Goodbye, Lenin: Ukraine moves to ban communist symbols

Due to these laws the city council had to rename more than 50 main streets and the administrative parts of the city, the monuments of the Soviet Union leaders (

New Zaporizhzhia Dniper Bridge

The New Zaporizhzhia Dniper Bridge is an under-construction road closed access highway bridge in Zaporizhzhya, Ukraine. Construction of the bridge began in August 2004 with the first span of the bridge opened to public use in January 2022 after yea ...

. These bridges are parallel to the existing Preobrazhensky Bridge at a short distance downstream. Construction of the bridges halted soon after it began, and remain untouched due to lack of funding. The project design is dated and needs revising, and the cost of the bridge is estimated to reach ‚Ç¥8 billion (as opposed to the original ‚Ç¥2 billion). In mid-November 2020, a Turkish contractor announced that it was starting the final stage of commissioning the first phase of construction. The work was planned to be completed before December.

Euromaidan events, 2013–2014

During the2014 Euromaidan regional state administration occupations

As part of the Euromaidan movement, regional state administration (RSA) buildings in various oblasts (regions) of Ukraine were occupied by activists, starting on 23 January 2014.

Background

Ukraine became gripped by unrest since President Vi ...

protests against President Viktor Yanukovych

Viktor Fedorovych Yanukovych ( uk, –í—ñ–∫—Ç–æ—Ä –§–µ–¥–æ—Ä–æ–≤–∏—á –Ø–Ω—É–∫–æ–≤–∏—á, ; ; born 9 July 1950) is a former politician who served as the fourth president of Ukraine from 2010 until he was removed from office in the Revolution of Di ...

were also held in Zaporizhzhia. On 23 February 2014 Zaporizhzhia's regional state administration building was occupied by 4,500 protesters, Mid-April 2014 there were clashes between Ukrainian and pro-Russian activists. The Ukrainian activists outnumbered the pro-Russian protesters.

Renaming city streets, plants, culture centres (2016)

On 19 May 2016, theVerkhovna Rada

The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine ( uk, –í–µ—Ä—Ö–æÃÅ–≤–Ω–∞ –Ý–∞ÃÅ–¥–∞ –£–∫—Ä–∞—óÃÅ–Ω–∏, translit=, Verkhovna Rada Ukrainy, translation=Supreme Council of Ukraine, Ukrainian abbreviation ''–í–Ý–£''), often simply Verkhovna Rada or just Rada, is the ...

approved the so-called " Decommunization Law."Poroshenko signed the laws about decomunizationUkrayinska Pravda

''Ukrainska Pravda'' ( uk, –£–∫—Ä–∞—ó–Ω—Å—å–∫–∞ –ø—Ä–∞–≤–¥–∞, lit=Ukrainian Truth) is a Ukrainian online newspaper founded by Georgiy Gongadze on 16 April 2000 (the day of the Ukrainian constitutional referendum). Published mainly in Ukraini ...

. 15 May 2015Interfax-Ukraine

The Interfax-Ukraine ( uk, –Ü–Ω—Ç–µ—Ä—Ñ–∞–∫—Å-–£–∫—Ä–∞—ó–Ω–∞) is a Kyiv-based Ukraine, Ukrainian independent news agency founded in 1992. The company does not belong to the Russian news corporation Interfax Information Services. The company pub ...

. 15 May 20BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broadca ...

(14 April 2015)Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

, Felix Dzerzhinsky

Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky ( pl, Feliks Dzierżyński ; russian: Фе́ликс Эдму́ндович Дзержи́нский; – 20 July 1926), nicknamed "Iron Felix", was a Bolshevik revolutionary and official, born into Poland, Polish n ...

) were destroyed. The names honoring Soviet leaders in the titles of industrial plants, factories, culture centres and the DniproHES

The Dnieper Hydroelectric Station ( uk, –î–Ω—ñ–ø—Ä–æ–ì–ï–°, DniproHES; russian: –î–Ω–µ–ø—Ä–æ–ì–≠–°, DneproGES), also known as Dneprostroi Dam, in the city of Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine, is the largest hydroelectric power station on the Dnieper river. ...

were removed.

Russian invasion (2022)

During the2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which began in 2014. The invasion has resulted in tens of thousands of deaths on both sides. It has caused Europe's largest refugee crisis since World War II. An ...

, Russian forces have been engaged in ongoing attacks on the city. On 27 February, some fighting was reported in the southern outskirts of Zaporizhzhia. Russian forces began shelling Zaporizhzhia later that evening. On March 3, Russian forces approaching the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant

The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Station ( uk, –ó–∞–ø–æ—Ä—ñ–∑—å–∫–∞ –∞—Ç–æ–º–Ω–∞ –µ–ª–µ–∫—Ç—Ä–æ—Å—Ç–∞–Ω—Ü—ñ—è, translit=Zaporiz'ka atomna elektrostantsiya, russian: –ó–∞–ø–æ—Ä–æ–∂—Å–∫–∞—è –∞—Ç–æ–º–Ω–∞—è —ç–ª–µ–∫—Ç—Ä–æ—Å—Ç–∞–Ω—Ü–∏—è, Zaporozhskaya ...

were fired upon disabling a tank, and responded causing a fire and concern about a potential nuclear meltdown. Firefighters were able to subdue the fire. Russian military forces fired missiles on Zaporizhzhia on the evening of May 12 and May 13. On 30 September, hours before Russia formally annexed Southern and Eastern Ukraine, the Russian Armed Forces launched S-300 missiles at a civilian convoy, killing 30 people and injuring 88 others. On 9 October, Russian forces launched rockets at residential buildings, killing at least twenty people.

Notes

References

{{reflist, 2