History of Trinity College, Oxford on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Trinity College, Oxford documents the 450 years from the foundation of

In 1553, King

In 1553, King

Bathurst's plan, executed over some thirty years, involved the regeneration of a number of Trinity's buildings, including the early fifteenth century chapel (which was rapidly becoming structurally unsound), and the Old Bursary, which became a

Bathurst's plan, executed over some thirty years, involved the regeneration of a number of Trinity's buildings, including the early fifteenth century chapel (which was rapidly becoming structurally unsound), and the Old Bursary, which became a

The perceived lack of academia in Oxford was not restricted to Trinity; it was a more widespread concern that led the University to introduce the Oxford University Examination Statute at the turn of the century, restricting degrees to those who had passed a much more rigorous examination than before. On the whole Trinity responded favourably to the impetus for educational reform during the first half of the nineteenth century. Collections were standardised and formalised in 1809 and by 1817

The perceived lack of academia in Oxford was not restricted to Trinity; it was a more widespread concern that led the University to introduce the Oxford University Examination Statute at the turn of the century, restricting degrees to those who had passed a much more rigorous examination than before. On the whole Trinity responded favourably to the impetus for educational reform during the first half of the nineteenth century. Collections were standardised and formalised in 1809 and by 1817

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the F ...

– a collegiate member of the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

– on 8 March 1554/5. The fourteenth oldest surviving college, it reused and embellished the site of the former Durham College, Oxford

Durham College was a college of the University of Oxford, founded by the monks of Durham Priory in the late 13th century. It was closed at the dissolution of the monasteries in the mid 16th century, and its buildings were subsequently used to f ...

. Opening its doors on 30 May 1555, its founder Sir Thomas Pope

Sir Thomas Pope (c. 150729 January 1559), was a prominent public servant in mid-16th-century England, a Member of Parliament, a wealthy landowner, and the founder of Trinity College, Oxford.

Early life

Pope was born at Deddington, near Ban ...

created it as a Catholic college teaching only theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

. It has been co-educational since 1979.

Origins

In 1553, King

In 1553, King Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

awarded the buildings and much of the grounds of the former Durham College, Oxford

Durham College was a college of the University of Oxford, founded by the monks of Durham Priory in the late 13th century. It was closed at the dissolution of the monasteries in the mid 16th century, and its buildings were subsequently used to f ...

(established in the second half of the thirteenth century and seized by the crown in 1545) to Dr George Owen of Godstow and William Martyn of Oxford. Two years later, on 20 February 1555 (20 February 1554 in contemporary notation), Owen and Martyn sold the property on to self-made politician Sir Thomas Pope

Sir Thomas Pope (c. 150729 January 1559), was a prominent public servant in mid-16th-century England, a Member of Parliament, a wealthy landowner, and the founder of Trinity College, Oxford.

Early life

Pope was born at Deddington, near Ban ...

. As an executor of Thomas Audley, Pope had been deeply involved with the foundation of Magdalene College, Cambridge

Magdalene College ( ) is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1428 as a Benedictine hostel, in time coming to be known as Buckingham College, before being refounded in 1542 as the College of St Mary ...

and the plot, situated on Broad Street, Oxford

Broad Street is a wide street in central Oxford, England, just north of the former city wall.

The street is known for its bookshops, including the original Blackwell's bookshop at number 50, located here due to the University of Oxford. Among re ...

, included a recently constructed library, refectory and sleeping quarters. The political climate was also favourable: the new Queen Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She ...

was taking a great interest in reviving Oxford as a place of Catholic study. As well as gaining influence with Mary, Pope (who was rich but childless) may also have seen the potential for ensuring that his family name lived on. On 8 March 1555, sixteen days after acquiring the Broad Street site, Pope was given permission to found a college in royal letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, titl ...

.

The new statutes drawn up named the new (Catholic) establishment as "The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity in the University of Oxford, of the Foundation of Thomas Pope", a name which persists. Durham College had been dedicated to the Virgin Mary, St Cuthbert

Cuthbert of Lindisfarne ( – 20 March 687) was an Anglo-Saxon saint of the early Northumbrian church in the Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit, associated with the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne in the Kingdom of Nor ...

, and the Trinity, and it is thought that Trinity College took its name from the last element of this dedication. The original statutes of the college provided for a President, twelve fellows, eight scholars and twenty commoners, making it one of Oxford's smallest colleges even at the time of its inception. The fellows were to study theology, a point insisted upon by Pope, who selected Thomas Slythurst

Thomas Slythurst (died 1560) was an English academic and Roman Catholic priest. He was the first President of Trinity College, Oxford. He lost his positions in 1559, on the accession of Elizabeth I of England, by his refusal to take the Oath of Su ...

, fellow of Magdalen, to be Trinity's first President. All the relevant property was transferred to the new college during Pope's only visit on 28 March 1555. Tuition for undergraduates included that in classical texts, philosophy (including arithmetic, geometry and arithmetic) and astronomy. Despite a delay whilst fellows were found, on 25 March 1556 revenues from the estates began to be transferred to the college. On 1 May the statutes officially came into force and 29 days later Trinity College Oxford opened its doors to its first students.

Early history (1555–1600)

Trinity's early problems centred on its finances, especially after Pope decided to establish places for four additional scholars. Aware of these problems, Pope both made out a loan to the college and gradually extended its endowment, such that by 1557 Trinity was in control of five manors:Wroxton

Wroxton is a village and civil parish in the north of Oxfordshire about west of Banbury. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 546.

Wroxton Abbey

Wroxton Abbey is a Jacobean country house on the site of a former Augustinian ...

-with-Balscote

Balscote or Balscott is a village in the civil parish of Wroxton, Oxfordshire, about west of Banbury. The Domesday Book of 1086 records the place-name as ''Berescote''. '' Curia regis'' rolls from 1204 and 1208 record it as ''Belescot''. An e ...

, Sewell, Dunthorp, Holcombe and Great Waltham

Great Waltham — also known as Church End — is a village and civil parish in the Chelmsford (borough), Chelmsford district, in the county of Essex.

The parish contains the village of Ford End, and the hamlets of Broad's Green, Howe Street, L ...

. In total, these generated a rent of approximately £200, which was augmented by £65 from other smaller land holdings. In 1558 Pope swapped in extra lands at Great Waltham and took back Sewell and Dunthorp with no overall impact on Trinity's finances. He also sent large consignments of furnishings for the chapel (many of them ex-monastical), as well as sixty-three books for the library and various utensils for the refectory. After various teething problems, the statutes were amended and finalised in the same year.

On 29 January 1559, Thomas Pope died, leaving the new college without a protector at court. His will, the execution of which was undertaken by his wife Elizabeth, did however include several references to Trinity, including the provision of funds for a fence to demarcate Trinity's land from that of next-door St. John's and for a residence outside the city to act as a safe-house during the frequent times of plague. Any remarriage on Elizabeth's part was to be accompanied by a large gift of furnishings to the college, a clause which was belatedly adhered to in 1564. Contrary to his will, however, Pope's body (original interred in St. Stephen's, Walbrook) was moved to the college chapel around the same time.

Trinity's Catholicism made for a difficult relationship with the Crown following Pope's death. The new Protestant Queen Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

, who succeeded to the throne in 1558, had the Catholic Slythurst removed from his post almost immediately. Fortunately for Trinity, his replacement (former fellow Arthur Yeldard), while hardly an avid Protestant, proved sufficiently pragmatic to retain his post for the next forty years. Over that time Trinity reluctantly moved with the times, and, threatened by the Crown, melted down its church plate and purchased new English-language psalm books. Fellows who disagreed with the changes left the college; this they did in significant numbers. In 1583, Trinity's first antagonism with neighbour (and modern rivals) Balliol was recorded, when the latter accused Trinity of being untrue to the Protestant faith.

The number of commoners (as opposed to religious scholars) attending grew steadily throughout the latter half of the sixteenth century, with the limit of twenty that had been imposed by the statutes quickly being exceeded. The group was divided according to circumstance, with servitor

In certain universities (including some colleges of University of Oxford and the University of Edinburgh), a servitor was an undergraduate student who received free accommodation (and some free meals), and was exempted from paying fees for lecture ...

s (who worked in college in part payment for their education) at the bottom, battelers in the middle and a further sub-divided hierarchy of fellow (or "gentleman") commoners at the top, though those from better backgrounds tended to have less need for official degrees and rarely bothered to officially matriculate

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term "matriculation" is seldom used now. ...

. During the same period, Trinity hired its first professional gardener.

Early seventeenth-century and Protectorate (1600–1664)

The history of Trinity in the seventeenth century was dominated by the presidencies of Trinity's third president, Ralph Kettell (president 1599 to 1643) and its eighth,Ralph Bathurst

Ralph Bathurst, FRS (1620 – 14 June 1704) was an English theologian and physician.

Early life

He was born in Hothorpe, Northamptonshire in 1620 and educated at King Henry VIII School, Coventry.

He graduated with a B.A. degree from Trinity C ...

(president 1664 to 1704). Among other things, Kettell was responsible for rebuilding the dining hall (formerly Durham College's refectory) and the surrounding buildings when the hall collapsed in 1618 following excavation work in its cellar, now the college bar. The library was refurbished multiple times and its collection expanded, most notably via bequests from alumni Edward Hyndmer (1625) and Richard Rands (1640). One fellow was officially appointed shortly after Hyndmer's donation as a librarian and paid a small stipend for his duties. More minor improvements included improvements to the toilet facilities available. A "sound administrator", Kettell led several round of fundraising from former students of all grades and contributed his own funds in order to fund these developments. In addition to cash contributions, the combination of donations of plate from alumni and the institution of a compulsory "plate fund" contribution for wealthier students meant that a sizeable collection of gold and silver plate was soon established, at its peak weighing some . Trinity was thus put on a firmer financial footing, with spare funds continually reinvested, largely successfully, in increasing both the quantity and quality of the accommodation on site. Also to this end, Kettell constructed Kettell Hall on adjoining land leased from Oriel College

Oriel College () is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in Oxford, England. Located in Oriel Square, the college has the distinction of being the oldest royal foundation in Oxford (a title formerly claimed by University College, w ...

. During Kettell's time it provided accommodation for Trinity students, though its later usage until its acquisition by Trinity is less clear. The result was a steady increase in the number of commoners attending to a peak of over 100 by 1630, though many did not stay to complete their degrees. Expenditure varied enormously among students; drunkenness and gambling were among the more common vices recorded.

The 1640s were less kind to Trinity as the college, like all others in Oxford, felt the effects of the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. First there was a loan of £200 to King Charles I in 1642, never repaid; then, after a brief alternation in the garrison of Oxford, it began to be fortified by the royalist cause. On 19 January 1643, almost all Trinity's plate, valued at £537, was forfeited to the crown, never to be seen again. Of the whole collection, only one chalice

A chalice (from Latin 'mug', borrowed from Ancient Greek () 'cup') or goblet is a footed cup intended to hold a drink. In religious practice, a chalice is often used for drinking during a ceremony or may carry a certain symbolic meaning.

Re ...

, one paten

A paten or diskos is a small plate, used during the Mass. It is generally used during the liturgy itself, while the reserved sacrament are stored in the tabernacle in a ciborium.

Western usage

In many Western liturgical denominations, the p ...

and two flagon

A flagon () is a large leather, metal, glass, plastic or ceramic vessel, used for drink, whether this be water, ale, or another liquid. A flagon is typically of about in volume, and it has either a handle (when strictly it is a jug), or (more ...

s survive. Many students (and later some fellows) simply left, or were not replaced, forcing the college to let its rooms to members of the King's court (a particularly attractive offer to those who were alumni of the college). Nevertheless, the college was brought to the point of financial collapse. During the surrender of Oxford to Parliament's forces in June 1646 the representatives of both sides were Trinity graduates. During the post-surrender purge of Oxford's royalists, Trinity's President Hannibal Potter, who had replaced Kettell on his death in 1643, was one of many to be forcibly exiled after a period of quiet defiance of the order to step down. He would remain in exile for 12 years.

A post-war audit undertaken by the Parliamentary Visitors revealed Trinity to have three fellows, nine scholars, and twenty-six commoners, though two fellows, one scholar, one commoner and both bursars were soon expelled for refusing to swear their loyalty to Parliament. A new President, Robert Harris, was simply imposed upon Trinity; despite this, what little evidence exists from his ten-year Presidency suggests little in the way of turmoil. Rather, Trinity recovered slowly, and it financial health improved considerably. Harris died on 12 December 1658, with the fellows electing William Hawes

William Hawes (178518 February 1846) was an English musician and composer. He was the Master of the Children of the Chapel Royal and musical director of the Lyceum Theatre bringing several notable works to the public's attention.

Life

Hawes was ...

as his successor before the Visitors could intervene. Hawes himself fell ill just nine months later, but conspired to resign shortly before his death, almost certainly with the intention of giving the fellows a head-start on Parliament's men once more. They elected Seth Ward, "one of the most able men to hold the presidency", but he too did not last in the role: the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

of the 1660s saw the return of Oxford to its pre-war personnel, including Hannibal Potter. He died, seemingly contented, in 1664. The new President was Ralph Bathurst

Ralph Bathurst, FRS (1620 – 14 June 1704) was an English theologian and physician.

Early life

He was born in Hothorpe, Northamptonshire in 1620 and educated at King Henry VIII School, Coventry.

He graduated with a B.A. degree from Trinity C ...

, who had been involved with the college intermittently for many years. Boosting student numbers was, he said, his immediate priority.

Bathurst's Trinity (1664–1704)

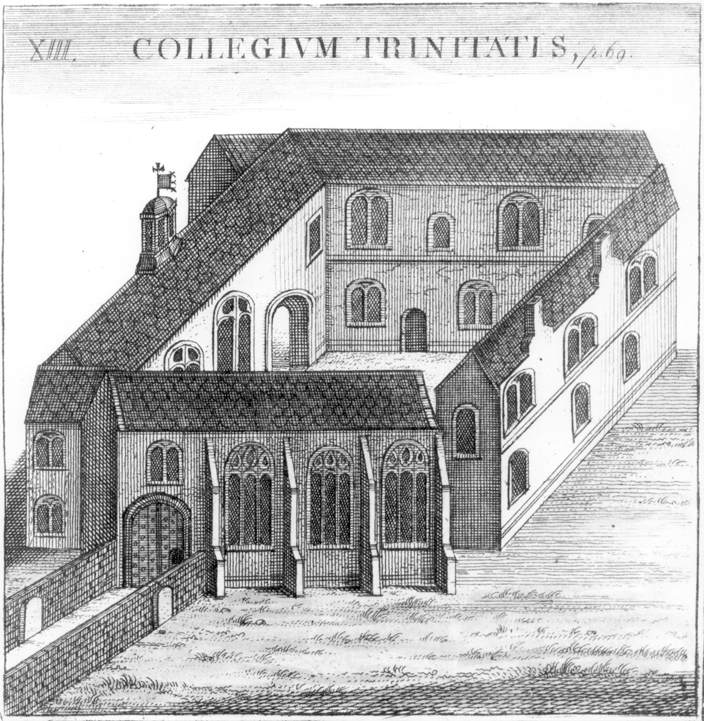

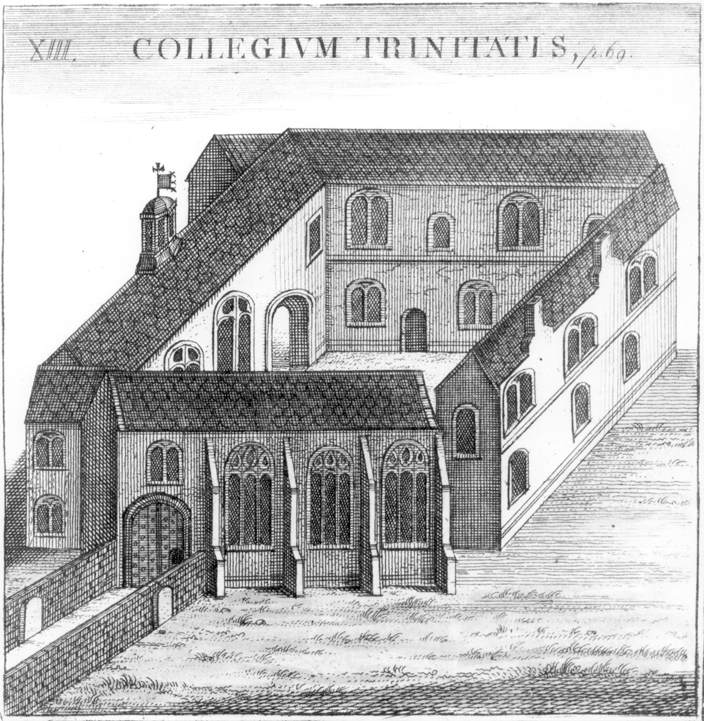

Bathurst's plan, executed over some thirty years, involved the regeneration of a number of Trinity's buildings, including the early fifteenth century chapel (which was rapidly becoming structurally unsound), and the Old Bursary, which became a

Bathurst's plan, executed over some thirty years, involved the regeneration of a number of Trinity's buildings, including the early fifteenth century chapel (which was rapidly becoming structurally unsound), and the Old Bursary, which became a common room

A common room is a type of shared lounge, most often found in halls of residence or dormitories, at (for example) universities, colleges, military bases, hospitals, rest homes, hostels, and even minimum-security prisons. They are generally con ...

. The old kitchen was similarly replaced in 1681, and the President's lodgings refurbished. The chapel, consecrated in April 1694 and requiring two loans to complete, is the only collegiate building to appear on the itinerary of Peter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

during his trip to Oxford, though it is unclear whether he set foot inside it. Also constructed was a separate building, designed, like the final flourish of the chapel's design, by Sir Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 churches ...

and forming the northern side of what is now the college's "Garden" quadrangle. Having raised funds from Trinity's alumni and fellows to settle the £1,500 construction costs, the new block was ready for use by 1668, though the room interior fittings were added gradually by their occupants. Bathurst's continuing desire for expansion precipitated in the creation from 1682–84 of an identical block, which now forms the western side of the Garden quadrangle, as well as an eponymous "Bathurst building", pulled down in the late nineteenth century.

The result was, as Bathurst had hoped, an increase in both the quantity and average wealth of Trinity's intake; by the 1680s there were once again over a hundred students at the college. In particular, the growth was driven by the children of England's middle classes, who sought to demonstrate their wealth by attending what was fast becoming Oxford's most expensive college. Trinity did however continue to admit annually four or five servitors – a quarter of the intake – though the rank of batteller slowly fell out of use. The college was also changing in other ways; although prayers remained compulsory, for example, the penalties for missing prayers were slowly relaxed, as were curfew times. Although the college authorities were prepared to overlook poorly performing students from influential families, the timetable still included seven hours a day for all students, with an extra three hours for many. Lectures remained "in house", though their content was gradually broadening, including "experimental philosophy" in addition to the more classical education students had received previously. Students could also take advantage of the first college undergraduate library in Oxford.

Eighteenth-century (1704–1799)

The eighteenth century saw far fewer variations in the college's fortunes, and it remained in much the same financial health as it was at the end of the seventeenth. Bathurst himself died in 1704, replaced in the presidency by Thomas Sykes, an inauspicious fellow of the college. By the time of the inheritance Sykes was in poor health, and he too died the next year. The new president, William Dobson, was of a similar generation to Sykes, having been a fellow for almost thirty years. Dobson was soon embroiled in controversy over the expulsion of a student, Henry Knollys, against the wishes of his tutor. Two more commoners were expelled shortly thereafter for vocally criticising the decision. He was also criticised for supporting the Whig cause in the University, to the point of breaking with established practice on the appointment of fellows. Dobson died in 1731. In his place, the fellows electedGeorge Huddesford

Rev. George Huddesford (1749–1809) was a painter and a satirical poet in Oxford. His first work was described by Fanny Burney as a "vile poem" as it revealed that she had written the novel, ''Evelina''.

Life

Huddesford was baptized at St. M ...

, who, on account of his relative youthfulness, remains the longest serving President of Trinity, occupying the position for 44 years and 292 days. Huddesford was in turn replaced by Joseph Chapman, an unexpected victor against the favourite Thomas Warton

Thomas Warton (9 January 172821 May 1790) was an English literary historian, critic, and poet. He was appointed Poet Laureate in 1785, following the death of William Whitehead.

He is sometimes called ''Thomas Warton the younger'' to disti ...

, who was by that time well known in the academic and literary worlds. Chapman saw out the rest of the century, dying in 1805.

Third storeys were added to all three sides of Garden Quadrangle in 1728, masking the flourishes of Wren's original French-style design; the dining hall was also refitted circa 1774, with Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including t ...

replacing the earlier Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

style. Trinity's site expanded slightly for essentially the first time since its foundation when a strip between Balliol and St. John's, the present borders of which were fixed in 1864, was purchased in several parcels between 1780 and 1787 and a cottage and latrines constructed on the site. In addition, two Trinity's three prime ministers, Lord North

Frederick North, 2nd Earl of Guilford (13 April 17325 August 1792), better known by his courtesy title Lord North, which he used from 1752 to 1790, was 12th Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1770 to 1782. He led Great Britain through most o ...

and William Pitt the Elder

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British statesman of the Whig group who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him Chatham or William Pitt the Elder to distinguish ...

, both graduated from the college during the century, and the college library – which gained its first rules on borrowing books in 1765 – was visited regularly by Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

. In reality, however, few Trinity students actively pursued their degrees during the period: increased living costs and a quiet relaxation of the statutes' religious requirements meant that Trinity's increasingly small annual intake tended to be drawn from the middle and upper classes, for whom a formal education was relatively unimportant. The last servitor, for example, was admitted in 1763. The culture of college had thus become quite different from the time of the foundation; revisions to the various penalties the college could impose suggest concern with both the level of alcohol consumption among students and the keeping of dogs for hunting (guns themselves being banned only in 1800). Responding, the college also introduced fixed oral examinations (the forerunner of modern collections

Collection or Collections may refer to:

* Cash collection, the function of an accounts receivable department

* Collection (church), money donated by the congregation during a church service

* Collection agency, agency to collect cash

* Collection ...

) twice annually for all students from 1789 onwards.

Nineteenth-century (1800–1907)

The perceived lack of academia in Oxford was not restricted to Trinity; it was a more widespread concern that led the University to introduce the Oxford University Examination Statute at the turn of the century, restricting degrees to those who had passed a much more rigorous examination than before. On the whole Trinity responded favourably to the impetus for educational reform during the first half of the nineteenth century. Collections were standardised and formalised in 1809 and by 1817

The perceived lack of academia in Oxford was not restricted to Trinity; it was a more widespread concern that led the University to introduce the Oxford University Examination Statute at the turn of the century, restricting degrees to those who had passed a much more rigorous examination than before. On the whole Trinity responded favourably to the impetus for educational reform during the first half of the nineteenth century. Collections were standardised and formalised in 1809 and by 1817 John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican ministry, Anglican priest and later as a Catholi ...

(then a student) could say happily that the "increasing rigour" had caused Trinity to "become the strictest of colleges". Nevertheless, he observed that ten years had passed since the last Trinitarian had graduated with first class honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

. Certainly, by the time of the Presidency of John Wilson (1850–) it was generally recognised that reform was needed both at Trinity and across the University as a whole to embed learning rather than religious instruction at its heart.

With a royal commission (established 1850) inquiring into the practices of the university, Wilson sought to inquire into Trinity's own, proposing increased pay for lecturers in order that they could provide daily tutorials

A tutorial, in education, is a method of transferring knowledge and may be used as a part of a learning process. More interactive and specific than a book or a lecture, a tutorial seeks to teach by example and supply the information to complete ...

, improved library access for undergraduates and the establishment of a system of exhibitions

An exhibition, in the most general sense, is an organized presentation and display of a selection of items. In practice, exhibitions usually occur within a cultural or educational setting such as a museum, art gallery

An art gallery is a roo ...

. In this endeavour he was aided by provisions made by the royal commission such that colleges could more openly deviate from their original statutes. By 1870 eight of the fellowship no longer had religious duties and in 1882 it was deemed optional for fellows (except for the Chaplain) to have taken Holy Orders. In addition, marriage was no longer considered incompatible with a Trinity fellowship for the first time. Trinity also sought to voluntarily open its scholarships to allcomers in 1816 and from 1825 onwards it allowed ex-scholars as well as scholars to become fellows, though the position retained its religious restrictions. This was followed in the 1843 by a decision to allow students of other colleges to become fellows at Trinity.

Blakiston's Trinity (1907–1938)

Herbert Blakiston

Herbert Edward Douglas Blakiston (5 September 1862 – 29 July 1942) was an England, English academic and clergyman who served as President (college), President of Trinity College, Oxford, and as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford.Clare ...

was elected President on 17 March 1907 after the death of his predecessor, Henry Francis Pelham

Henry Francis Pelham, FSA, FBA (10 September 1846 in Bergh Apton, Norfolk – 13 February 1907) was an English scholar and historian. He was Camden Professor of Ancient History at the University of Oxford from 1889 to 1907, and was also Pr ...

. He was the fellows' second choice for the position, their preferred candidate turned it down. Blakiston had barely left Trinity in a quarter of a century: first as a scholar, then tutor, chaplain, senior tutor and domestic bursar, not to mention the author of the college's first definitive history in 1898. Efficient but cold, eccentric but financially tight-fisted, Blakiston would be President until his resignation in 1938, continuing in the role of domestic bursar and then as "elder statesman" until his death in 1942 in a road accident.

The period was characterised by modest revelry that included drunken students regularly setting bonfires around the site; Blakiston was not greatly minded to send down students lest doing so discourage sons from other middle-class families from applying. It was for the same reasons that he would choose to admit just one non-white student during his 24 years and to strenuously oppose the integration of female students into the university in 1920. Not unrelatedly, it was during this time that Trinity's rivalry with the more liberal Balliol also reached a temporary maximum.With the onset of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1914, the number of undergraduates at Trinity fell dramatically. In May the college had 150 in residence; by the end of the year the number was closer to 30, and by the end of the war it was in single digits. Blakiston wrote to the bereaved families, of which there were soon many, including the family of Noel Chavasse

Captain Noel Godfrey Chavasse, (9 November 1884 – 4 August 1917) was a British medical doctor, Olympic athlete, and British Army officer from the Chavasse family. He is one of only three people to be awarded a Victoria Cross twice.

The Battl ...

(died 1917), one of three British soldiers ever to be awarded the Victoria Cross with bar. With so few paying students, college finances were weak, and many of the staff, including Blakiston, took sizeable pay cuts. Revenue from rooms requisitioned by the armed forces eased the college's longer term outlook; the construction of a new bathhouse at Trinity was also undertaken by its new residents, apparently at no cost. In addition to the exit of so many students, several fellows also volunteered for army service. Consequently, Blakiston was forced to take on greater administrative duties at both the collegiate and university levels, including the Vice-Chancellorship of the university (1917–1920). Nevertheless, he remained firmly "a college man", and most of his later involvement with university politics centred on the retention of Trinity's independence.

In total, 820 Trinitarians or ex-Trinitarians served in the war; 153 did not survive it. Nevertheless, the peace saw Trinity revitalised, back up to full numbers within two years. In 1919, Blakiston began the task of identifying a suitable monument to the dead; it was his suggestion, a new library, which carried the day. The new library, which opened in 1928, was funded via benefactions; of which there were many. Blakiston took a personal interest in the design, though his flourishes to the entrance-way were later removed to accommodate the construction of a new housing block adjacent to the library. Nevertheless, the middle class-dominated Trinity remained better known for its sport than its academics during the period (the research of fellow Cyril Hinshelwood

Sir Cyril Norman Hinshelwood (19 June 1897 – 9 October 1967) was a British physical chemist and expert in chemical kinetics. His work in reaction mechanisms earned the 1956 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Education

Born in London, his parents we ...

being one exception to this trend). Other building work included the restoration of the chapel, renovation of the cottages (now staircase 1) and the construction of a new bathhouse.

Recent history (1939–present)

By comparison with the First World War, Trinity was not greatly affected by the outbreak of the Second in September 1939, aided by the University-wide introduction of courses specially structured for budding officers and the booking out of the New Buildings to host Balliol students after the latter's own accommodation was requisitioned. The number of students remained strong as that at other colleges diminished, with Trinity able to utilise its contacts to maintain a good standard of living despite the shortages. Nevertheless, casualties were almost as bad as quarter of a decade previously; in total, some 133 Old Trinitarians died serving, a disproportionate number in the RAF, as was common with Oxford students in general. Membership of the Fellows'Senior Common Room

A common room is a group into which students and the academic body are organised in some universities in the United Kingdom and Ireland—particularly collegiate universities such as Oxford and Cambridge, as well as the University of Bristol ...

was also particularly diminished, during the war years at least.

The post-war period has seen a substantial increase in the number of students at Trinity, though as of 2013 it remains one of the smallest in Oxford. New accommodation in the form of the Cumberbatch buildings (the modern staircases 3 and 4) were opened in 1966 and the college also benefited greatly from the university-wide effort to re-face the many stone buildings around Oxford that had blackened over the centuries. The replacement of the plasterwork in the hall was completed just in time for Trinity to host the Queen, her husband Prince Philip

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 1921 – 9 April 2021) was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. As such, he served as the consort of the British monarch from E ...

, and the Prime Minister Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as "Supermac", he ...

in 1960 upon the laying of the foundation stone of St Catherine's College by the Queen. The increase in the number of graduate students prompted the creation of a dedicated Middle Common Room in 1964. There was also a similar increase in the number of Fellows. The costs of expansion were funded mostly through benefactions, though the funds received from Blackwell's

Blackwell UK, also known as Blackwell's and Blackwell Group, is a British academic book retailer and library supply service owned by Waterstones. It was founded in 1879 by Benjamin Henry Blackwell, after whom the chain is named, on Broad Street, ...

for the construction and lease of the subterranean Norrington Room (named after the then-President Arthur Norrington) also proved useful. Later additions included outside properties at Rawlinson Road (1970) and Staverton Road (1986) and the construction of an eighteenth on-site staircase (1992).

With the broadening of state funding for poorer students, Trinity's pre-war attachment to the middle classes looked increasing outmoded; the college found it difficult to throw off its reputation for racism. The rivalry with Balliol was reinvigorated, leading to several well-publicised events, including the blacking up of the Trinity first VIII rowing team (1952) and the turfing of the Trinity JCR by Balliol students (1963). Slowly, however, most of the college's stricter traditions fell away. The period of liberalisation accelerated under Norrington's successor Alexander Ogston

Sir Alexander Ogston MD CM LLD (19 April 1844 – 1 February 1929) was a British surgeon, famous for his discovery of ''Staphylococcus''.

Life

Ogston was the eldest son of Amelia Cadenhead and her husband Prof. Francis Ogston (1803– ...

. Trinity gained its first female lecturer in 1968, overnight guests were allowed from 1972 and weekend guests from 1974, and the late-night curfew was effectively abolished in 1977. By that time, college had also shifted from the employment of college servants to a professionalised body of staff more in keeping with the realities of post-war jobs market. The result was that breakfast and lunch became self-service as a result and the first on-site student kitchen facilities provided in 1976. In addition, the JCR started taking direct control of its own funds from 1972. By far the most significant change, however, was the admission of the first women to Trinity from October 1979, though the transition was ultimately a smooth one. The first female fellow was elected in 1984, completing the shift in day-to-day workings from monastic priory to modern college.

In 2017, the college’s first woman president, Hilary Boulding

Dame Hilary Boulding, (born 25 January 1957) is a British academic administrator and former media professional. Since 2017, she has been the Master (college), President of Trinity College, Oxford, Trinity College, University of Oxford. She form ...

, celebrated sixteen women alumni in a poster and booklet entitled "Feminae Trinitatis". They included Dame Frances Ashcroft, Siân Berry

Siân Rebecca Berry (born 9 July 1974) is a British politician who served as Co-Leader of the Green Party of England and Wales alongside Jonathan Bartley from 2018 to 2021, and as its sole leader from July to October 2021. From 2006 to 2007, s ...

, Dame Sally Davies, Olivia Hetreed, Kate Mavor, Sarah Oakley

Captain Sarah Ellen Oakley (born February 1973) is a British Royal Navy officer, currently serving as commanding officer of the Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth.

In the Iraq War, Oakley worked in oil platform protection. Her first c ...

, Roma Tearne

Roma Tearne (née Chrysostom; born 1954) is a Sri Lankan-born artist and writer living and working in England. Her debut novel, ''Mosquito'', was shortlisted for the 2007 Costa Book Awards first Novel prize (formerly the Whitbread Prize).

Ear ...

, and the opera singer Claire Booth.

In 2019, the Cumberbatch Building was demolished to make way for the new Levine Building. This is due to be finished at the end 2021 and will include 46 new student bedrooms, an auditorium, teaching rooms, a function room, and a café. It is named in recognition of Peter Levine, who studied at Trinity in the 1970s, whose transformational donation in memory of his parents allowed this project, and many other notable college-wide initiatives, to take shape.

The grounds of Trinity were, in part, the basis for Fleet College in Charles Finch's ''The Last Enchantments''.

References

Bibliography

* . * . * {{citation, first=Michael, last=Maclagan , authorlink=Michael Maclagan , title=Trinity College 1555-1955, location=Oxford, year=1955.History

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...