The

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

has served as the supreme law of the United States since taking effect in 1789. The document was written at the 1787

Philadelphia Convention

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. Although the convention was intended to revise the league of states and first system of government under the Articles of Confederation, the intention fr ...

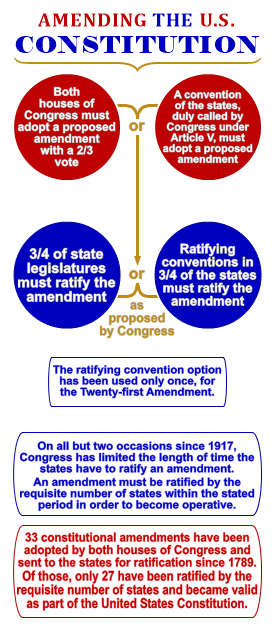

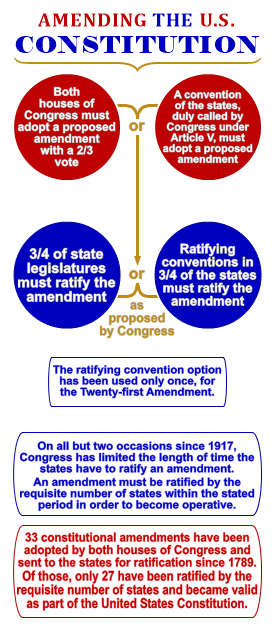

and was ratified through a series of state conventions held in 1787 and 1788. Since 1789, the Constitution has been amended twenty-seven times; particularly important amendments include the ten amendments of the

United States Bill of Rights

The United States Bill of Rights comprises the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. Proposed following the often bitter 1787–88 debate over the ratification of the Constitution and written to address the objections rais ...

and the three

Reconstruction Amendments

The , or the , are the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments to the United States Constitution, adopted between 1865 and 1870. The amendments were a part of the implementation of the Reconstruction of the American South which occ ...

.

The Constitution grew out of efforts to reform the

Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

, an earlier constitution which provided for a loose alliance of states with a weak central government. From May 1787 through September 1787, delegates from twelve of the thirteen states convened in Philadelphia, where they wrote a new constitution. Two alternative plans were developed at the convention. The nationalist majority, soon to be called "

Federalists

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

", put forth the

Virginia Plan

The ''Virginia Plan'' (also known as the Randolph Plan, after its sponsor, or the Large-State Plan) was a proposal to the United States Constitutional Convention for the creation of a supreme national government with three branches and a bicam ...

, a consolidated government based on proportional representation among the states by population. The "old patriots", later called "

Anti-Federalists

Anti-Federalism was a late-18th century political movement that opposed the creation of a stronger U.S. federal government and which later opposed the ratification of the 1787 Constitution. The previous constitution, called the Articles of Con ...

", advocated the

New Jersey Plan

The New Jersey Plan (also known as the Small State Plan or the Paterson Plan) was a proposal for the structure of the United States Government presented during the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Principally authored by William Paterson of Ne ...

, a purely federal proposal, based on providing each state with equal representation. The

Connecticut Compromise

The Connecticut Compromise (also known as the Great Compromise of 1787 or Sherman Compromise) was an agreement reached during the Constitutional Convention of 1787 that in part defined the legislative structure and representation each state woul ...

allowed for both plans to work together. Other controversies developed regarding slavery and a Bill of Rights in the original document.

The drafted Constitution was submitted to the

Congress of the Confederation in September 1787; that same month it approved the forwarding of the Constitution as drafted to the states, each of which would hold a ratification convention. ''

The Federalist Papers

''The Federalist Papers'' is a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the collective pseudonym "Publius" to promote the ratification of the Constitution of the United States. The co ...

'', were

published in newspapers while the states were debating ratification, which provided background and justification for the Constitution. Some states agreed to ratify the Constitution only if the amendments that were to become the Bill of Rights would be taken up immediately by the new government. In September 1788, the Congress of the Confederation certified that eleven states had ratified the new Constitution, and directed that elections be held. The new government began on March 4, 1789, assembled in New York City, and the government authorized by the Articles of Confederation dissolved itself.

In 1791, the states ratified the Bill of Rights, which established protections for various civil liberties. The Bill of Rights initially only applied to the federal government, but following a process of

incorporation most protections of the Bill of Rights now apply to state governments. Further amendments to the Constitution have addressed federal relationships, election procedures, terms of office, expanding the electorate, financing the federal government, consumption of alcohol, and congressional pay. Between 1865 and 1870, the states ratified the Reconstruction Amendments, which abolished

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, guaranteed equal protection of the law, and implemented prohibitions on the restriction of voter rights. The meaning of the Constitution is interpreted by

judicial review

Judicial review is a process under which executive, legislative and administrative actions are subject to review by the judiciary. A court with authority for judicial review may invalidate laws, acts and governmental actions that are incompat ...

in the federal courts. The original parchment copies are on display at the

National Archives Building

The National Archives Building, known informally as Archives I, is the headquarters of the United States National Archives and Records Administration. It is located north of the National Mall at 700 Pennsylvania Avenue, Northwest, Washington, ...

.

Revolution and Early Governance

Declaration of Independence

On June 4, 1776,

a resolution was introduced in the

Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

declaring the union with

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

to be dissolved, proposing the formation of foreign alliances, and suggesting the drafting of a plan of confederation to be submitted to the respective states. Independence was declared on July 4, 1776; the preparation of a plan of confederation was postponed. Although the Declaration was a statement of principles, it did not create a government or even a framework for how politics would be carried out. It was the

Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

that provided the necessary structure to the new nation during and after the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

. The Declaration, however, did set forth the ideas of

natural rights and the

social contract

In moral and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships betw ...

that would help form the foundation of constitutional government.

The era of the Declaration of Independence is sometimes called the "Continental Congress" period.

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

famously estimated as many as one-third of those resident in the original thirteen colonies were patriots. Scholars such as

Gordon Wood describe how Americans were caught up in the Revolutionary fervor and excitement of creating governments, societies, a new nation on the face of the earth by rational choice as

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

declared in ''

Common Sense

''Common Sense'' is a 47-page pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–1776 advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies. Writing in clear and persuasive prose, Paine collected various moral and political argu ...

''.

Republican government and personal liberty for "the people" were to overspread the New World continents and to last forever, a gift to posterity. These goals were influenced by

Enlightenment philosophy

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

. The adherents to this cause seized on English

Whig political philosophy as described by historian

Forrest McDonald

Forrest McDonald, Jr. (January 7, 1927 – January 19, 2016) was an American historian who wrote extensively on the early national period of the United States, republicanism, and the presidency, but he is possibly best known for his polemic on the ...

as justification for most of their changes to received colonial charters and traditions. It was rooted in opposition to monarchy they saw as venal and corrupting to the "permanent interests of the people."

To these partisans, voting was the only permanent defense of the people. Elected terms for legislature were cut to one year, for Virginia's Governor, one year without re-election. Property requirements for

suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

for men were reduced to taxes on their tools in some states. Free blacks in

New York could vote if they owned enough property.

New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

was thinking of abolishing all voting requirements for men except residency and religion.

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

let women vote. In some states, senators were now elected by the same voters as the larger electorate for the House, and even judges were elected to one-year terms.

These "

radical Whigs

The Radical Whigs were a group of British political commentators associated with the British Whig faction who were at the forefront of the Radical movement.

Seventeenth century

The radical Whigs ideology "arose from a series of political uphea ...

" were called the people "out-of-doors." They distrusted not only royal authority, but any small, secretive group as being unrepublican. Crowds of men and women massed at the steps of rural Court Houses during market-militia-court days.

Shays' Rebellion (1786–87) is a famous example. Urban riots began by the out-of-doors rallies on the steps of an oppressive government official with speakers such as members of the

Sons of Liberty

The Sons of Liberty was a loosely organized, clandestine, sometimes violent, political organization active in the Thirteen American Colonies founded to advance the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. It pl ...

holding forth in the "people's "committees" until some action was decided upon, including hanging his effigy outside a bedroom window, or looting and burning down the offending tyrant's home.

First and Second Continental Congresses

The

First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from 12 of the 13 British colonies that became the United States. It met from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, after the British Navy ...

met from September 5 to October 26, 1774. It agreed that the states should impose an economic boycott on British trade, and drew up a petition to King

George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, pleading for redress of their grievances and repeal of the

Intolerable Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measure ...

. It did not propose independence or a separate government for the states.

The

Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

convened on May 10, 1775, and functioned as a ''de facto'' national government at the outset of the

Revolutionary War. Beginning in 1777, the substantial powers assumed by Congress "made the league of states as cohesive and strong as any similar sort of republican confederation in history". The process created the United States "by the people in collectivity, rather than by the individual states", because only four states had constitutions at the time of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, and three of those were provisional.

The Supreme Court in

Penhallow v. Doane's Administrators

''Penhallow v. Doane's Administrators'', 3 U.S. (3 Dall.) 54 (1795), was a United States Supreme Court case about prize causes, holding that federal district courts have the powers formerly granted to the Court of Appeals in Cases of Capture under ...

(1795), and again in

Ware v. Hylton (1796), ruled on the federal government's powers prior to the adoption of the U.S. Constitution in 1788. It said that Congress exercised powers derived from the people, expressly conferred through the medium of state conventions or legislatures, and, once exercised, those powers were "impliedly ratified by the acquiescence and obedience of the people".

Confederation Period

The

Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

was approved by the Second Continental Congress on November 15, 1777, and sent to the states for

ratification

Ratification is a principal's approval of an act of its agent that lacked the authority to bind the principal legally. Ratification defines the international act in which a state indicates its consent to be bound to a treaty if the parties inten ...

. It came into force on March 1, 1781, after being ratified by all 13 states. Over the previous four years it had been used by Congress as a "working document" to administer the early United States government and win the Revolutionary War.

Lasting successes under the Articles of Confederation included the

Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

with Britain and the

Land Ordinance of 1785, whereby Congress promised settlers west of the

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

full citizenship and eventual statehood. Some historians characterize this period from 1781 to 1789 as weakness, dissension, and turmoil. Other scholars view the evidence as reflecting an underlying stability and prosperity. But the returning of prosperity in some areas did not slow the growth of domestic and foreign problems. Nationalists saw the confederation's central government as not strong enough to establish a sound financial system, regulate trade, enforce treaties, or go to war when needed.

[Morris (1987)]

The

Congress of the Confederation, as defined in the Articles of Confederation, was the sole organ of the national government; there was no national court to interpret laws nor an executive branch to enforce them. Governmental functions, including declarations of war and calls for an army, were voluntarily supported by each state, in full, partly, or not at all.

The newly independent states, separated from Britain, no longer received

favored treatment at British ports. The British refused to negotiate a commercial treaty in 1785 because the individual American states would not be bound by it. Congress could not act directly upon the States nor upon individuals. It had no authority to regulate foreign or interstate commerce. Every act of government was left to the individual States. Each state levied taxes and tariffs on other states at will, which invited retaliation. Congress could vote itself mediator and judge in state disputes, but states did not have to accept its decisions.

The weak central government could not back its policies with military strength, embarrassing it in foreign affairs. The British refused to withdraw their troops from the forts and trading posts in the new nation's

Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

, as they had agreed to do in the

Treaty of Paris of 1783

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

. British officers on the northern boundaries and Spanish officers to the south supplied arms to Native American tribes, allowing them to attack American settlers. The Spanish refused to allow western American farmers to use their port of

to ship produce.

Revenues were requisitioned by Congressional petition to each state. None paid what they were asked; sometimes some paid nothing. Congress appealed to the thirteen states for an amendment to the Articles to tax enough to pay the public debt as principal came due. Twelve states agreed,

Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

did not, so it failed. The Articles required super majorities. Amendment proposals to states required ratification by all thirteen states, all important legislation needed 70% approval, at least nine states. Repeatedly, one or two states defeated legislative proposals of major importance.

Without taxes the government could not pay its debt. Seven of the thirteen states printed large quantities of its own paper money, backed by gold, land, or nothing, so there was no fair exchange rate among them. State courts required state creditors to accept payments at face value with a fraction of real purchase power. The same legislation that these states used to wipe out the Revolutionary debt to patriots was used to pay off promised veteran pensions. The measures were popular because they helped both small farmers and plantation owners pay off their debts.

The Massachusetts legislature was one of the five against paper money. It imposed a tightly limited currency and high taxes. Without paper money veterans without cash lost their farms for back taxes. This triggered

Shays' Rebellion to stop tax collectors and close the courts. Troops quickly suppressed the rebellion, but nationalists like George Washington warned, "There are combustibles in every state which a spark might set fire to."

Prelude to the Constitutional Convention

Mount Vernon Conference

An important milestone in interstate cooperation outside the framework of the Articles of Confederation occurred in March 1785, when delegates representing

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

and

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

met in Virginia, to address navigational

rights

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical the ...

in the states's common waterways.

On March 28, 1785, the group drew up a thirteen-point proposal to govern the two states' rights on the

Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

,

Pocomoke River, and

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

.

Known as the Mount Vernon Compact (formally titled the "Compact of 1785"), this

agreement Agreement may refer to:

Agreements between people and organizations

* Gentlemen's agreement, not enforceable by law

* Trade agreement, between countries

* Consensus, a decision-making process

* Contract, enforceable in a court of law

** Meeting o ...

not only covered tidewater navigation but also extended to issues such as

toll duties, commerce regulations, fishing rights, and debt collection. Ratified by the

legislatures

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country or city. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers of government.

Laws enacted by legislatures are usually known a ...

of both

states, the compact, which is still

in force, helped set a precedent for later meetings between states for discussions into areas of mutual concern.

[

The conference's success encouraged ]James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

to introduce a proposal in the Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, the first elected legislative assembly in the New World, and was established on July 30, 161 ...

for further debate of interstate issues. With Maryland's agreement, on January 21, 1786, Virginia invited all the states to attend another interstate meeting later that year in Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

, to discuss the trade barriers between the various states.

Constitutional reforms considered

The Congress of the Confederation received a report on August 7, 1786, from a twelve-member "Grand Committee", appointed to develop and present "such amendments to the Confederation, and such resolutions as it may be necessary to recommend to the several states, for the purpose of obtaining from them such powers as will render the federal government adequate to" its declared purposes. Seven amendments to the Articles of Confederation were proposed. Under these reforms, Congress would gain "sole and exclusive" power to regulate trade. States could not favor foreigners over citizens. Tax bills would require 70% vote, public debt 85%, not 100%. Congress could charge states a late payment penalty fee. A state withholding troops would be charged for them, plus a penalty. If a state did not pay, Congress could collect directly from its cities and counties. A state payment on another's requisition would earn annual 6%. There would have been a national court of seven. No-shows at Congress would have been banned from any U.S. or state office. These proposals were, however, sent back to committee without a vote and were not taken up again.

Annapolis Convention

The Annapolis Convention, formally titled "A Meeting of Commissioners to Remedy Defects of the Federal Government", convened at George Mann's Tavern on September 11, 1786. Delegates from five states gathered to discuss ways to facilitate commerce between the states and establish standard rules and regulations. At the time, each state was largely independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

from the others and the national government had no authority in these matters.

Appointed delegates from four states either arrived too late to participate or otherwise decided not attend. Because so few states were present, delegates did not deem "it advisable to proceed on the business of their mission." However, they did adopt a report calling for another convention of the states to discuss possible improvements to the Articles of Confederation. They desired that Constitutional Convention take place in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

in the summer of 1787.

Legislatures of seven states—Virginia, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Delaware, and Georgia—immediately approved and appointed their delegations. New York and others hesitated thinking that only the Continental Congress could propose amendments to the Articles. Congress then called the convention at Philadelphia. The "Federal Constitution" was to be changed to meet the requirements of good government and "the preservation of the Union". Congress would then approve what measures it allowed, then the state legislatures would unanimously confirm whatever changes of those were to take effect.

Constitutional Convention

Twelve state legislatures, Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

being the only exception, sent delegates to convene at Philadelphia in May 1787.

Sessions

The Congress of the Confederation endorsed a plan to revise the Articles of Confederation on February 21, 1787.James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

arrived to Philadelphia and met with James Wilson James Wilson may refer to:

Politicians and government officials

Canada

*James Wilson (Upper Canada politician) (1770–1847), English-born farmer and political figure in Upper Canada

* James Crocket Wilson (1841–1899), Canadian MP from Quebe ...

of the Pennsylvania delegation to plan strategy. Madison outlined his plan in letters: (1) State legislatures shall each send delegates instead of using members of the Congress of the Confederation. (2) The convention will reach agreement with signatures from every state. (3) The Congress of the Confederation will approve it and forward it to the state legislatures. (4) The state legislatures independently call one-time conventions to ratify it, using delegates selected via each state's various rules of suffrage. The convention was to be "merely advisory" to the people voting in each state.

Convening and Rules

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

arrived on time, Sunday, the day before the scheduled opening. For the entire duration of the convention, Washington was a guest at the home of Robert Morris, Congress' financier for the American Revolution and a Pennsylvania delegate. Morris entertained the delegates lavishly. William Jackson, in two years to be the president of the Society of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of military officers wh ...

, had been Morris' agent in England for a time; and he won election as a non-delegate to be the convention secretary.

File:Gilbert Stuart Williamstown Portrait of George Washington.jpg, George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

Convention President

File:Nathaniel Gorham.jpg, Nathaniel Gorham

Nathaniel Gorham (May 27, 1738 – June 11, 1796; sometimes spelled ''Nathanial'') was an American Founding Father, merchant, and politician from Massachusetts. He was a delegate from the Bay Colony to the Continental Congress and for six months ...

, MA

Chair, Cmte. of the Whole

The convention was scheduled to open May 14, but only Pennsylvania and Virginia delegations were present. The convention was postponed until a quorum of seven states gathered on Friday the 25th. George Washington was elected the Convention president, and Chancellor (judge) George Wythe

George Wythe (; December 3, 1726 – June 8, 1806) was an American academic, scholar and judge who was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. The first of the seven signatories of the United States Declaration of Independence from ...

(Va) was chosen Chair of the Rules Committee. The rules of the convention were published the following Monday.

Nathaniel Gorham

Nathaniel Gorham (May 27, 1738 – June 11, 1796; sometimes spelled ''Nathanial'') was an American Founding Father, merchant, and politician from Massachusetts. He was a delegate from the Bay Colony to the Continental Congress and for six months ...

(MA) was elected Chair of the "Committee of the Whole". These were the same delegates in the same room, but they could use informal rules for the interconnected provisions in the draft articles to be made, remade and reconnected as the order of business proceeded. The Convention officials and adopted procedures were in place before the arrival of nationalist opponents such as John Lansing (NY) and Luther Martin (MD). By the end of May, the stage was set.

The Constitutional Convention voted to keep the debates secret so that the delegates could speak freely, negotiate, bargain, compromise and change. Yet the proposed Constitution as reported from the convention was an "innovation", the most dismissive epithet a politician could use to condemn any new proposal. It promised a fundamental change from the old confederation into a new, consolidated yet federal government. The accepted secrecy of usual affairs conducted in regular order did not apply. It became a major issue in the very public debates leading up to the crowd-filled ratification conventions.

Despite the public outcry against secrecy among its critics, the delegates continued in positions of public trust. State legislatures chose ten Convention delegates of their 33 total for the Constitutional Convention that September.

Quorum

File:James Madison.jpg, James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

, VA

"Father of the Constitution"

File:JusticeJamesWilson.jpg, James Wilson James Wilson may refer to:

Politicians and government officials

Canada

*James Wilson (Upper Canada politician) (1770–1847), English-born farmer and political figure in Upper Canada

* James Crocket Wilson (1841–1899), Canadian MP from Quebe ...

, PA

"unsung hero of Convention"

Every few days, new delegates arrived, happily noted in Madison's Journal. But as the Convention went on, individual delegate coming and going meant that a state's vote could change with the change of delegation composition. The volatility added to the inherent difficulties, making for an "ever-present danger that the Convention might dissolve and the entire project be abandoned."

Although twelve states sent delegations, there were never more than eleven represented in the floor debates, often fewer. State delegations absented themselves at votes different times of day. There was no minimum for a state delegation; one would do. Daily sessions would have thirty members present. Members came and went on public and personal business. The Congress of the Confederation was meeting at the same time, so members would absent themselves to New York City on Congressional business for days and weeks at a time.

But the work before them was continuous, even if attendance was not. The Convention resolved itself into a "Committee of the Whole", and could remain so for days. It was informal, votes could be taken and retaken easily, positions could change without prejudice, and importantly, no formal quorum call

In legislatures, a quorum call is used to determine whether a quorum is present. Since attendance at debates is not mandatory in most legislatures, it is often the case that a quorum of members is not present while debate is ongoing. A member w ...

was required. The nationalists were resolute. As Madison put it, the situation was too serious for despair. They used the same State House, later named Independence Hall

Independence Hall is a historic civic building in Philadelphia, where both the United States Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were debated and adopted by America's Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Fa ...

, as the Declaration signers. The building setback from the street was still dignified, but the "shaky" steeple was gone. When they adjourned each day, they lived in nearby lodgings, as guests, roomers or renters. They ate supper with one another in town and taverns, "often enough in preparation for tomorrow's meeting."

Delegates reporting to the Convention presented their credentials to the Secretary, Major William Jackson of South Carolina. The state legislatures of the day used these occasions to say why they were sending representatives abroad. New York thus publicly enjoined its members to pursue all possible "alterations and provisions" for good government and "preservation of the Union". New Hampshire called for "timely measures to enlarge the powers of Congress". Virginia stressed the "necessity of extending the revision of the federal system to all its defects". Conversely, Delaware categorically forbade any alteration of the Articles one-vote-per-state provision in the Articles of Confederation. The convention would have a great deal of work to do to reconcile the many expectations in the chamber. At the same time, delegates wanted to finish their work by fall harvest and its commerce.

Agenda

File:EdRand.jpg, Edmund Randolph

Edmund Jennings Randolph (August 10, 1753 September 12, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, and the 7th Governor of Virginia. As a delegate from Virginia, he attended the Constitutional Convention and helped to create ...

, VA

consolidated government

File:William Paterson copy.jpg, William Paterson, NJ

states and congress equal

On May 29, Edmund Randolph

Edmund Jennings Randolph (August 10, 1753 September 12, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, and the 7th Governor of Virginia. As a delegate from Virginia, he attended the Constitutional Convention and helped to create ...

(VA) proposed the Virginia Plan

The ''Virginia Plan'' (also known as the Randolph Plan, after its sponsor, or the Large-State Plan) was a proposal to the United States Constitutional Convention for the creation of a supreme national government with three branches and a bicam ...

, which unofficially set the agenda for the convention.New Jersey Plan

The New Jersey Plan (also known as the Small State Plan or the Paterson Plan) was a proposal for the structure of the United States Government presented during the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Principally authored by William Paterson of Ne ...

. It was weighted toward the interests of the smaller, less populous states. The intent was to preserve the states from a plan to "destroy or annihilate" them. The New Jersey Plan was purely federal, authority flowed from the states. Gradual change should come from the states. If the Articles could not be amended, then advocates argued that should be the report from the convention to the states.

Although the New Jersey Plan only survived three days as a proposal, it served as an important alternative to the Virginia Plan.James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

, found chronologically incorporated in Max Farrand

Max Farrand (March 29, 1869 – June 17, 1945) was an American historian who taught at several universities and was the first director of the Huntington Library.

Early life

He was born in Newark, New Jersey, United States. He graduated from ...

's "The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787", which included the Convention Journal and sources from other Federalists and Anti-Federalists.

Scholars observe that it is unusual in world history for the minority in a revolution to have the influence that the "old patriot" Anti-Federalists had over the "nationalist" Federalists who had the support of the revolutionary army in the Society of the Cincinnati. Both factions were intent on forging a nation in which both could be full participants in the changes which were sure to come, since that was most likely to allow for their national union, guarantee liberty for their posterity, and promote their mutual long-term material prosperity.

Debate Over Slavery

The contentious issue of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

was too controversial to be resolved during the convention. But it was at center stage in the Convention three times: June 7 regarding who would vote for Congress, June 11 in debate over how to proportion relative seating in the 'house', and August 22 relating to commerce and the future wealth of the nation.

Once the Convention looked at how to proportion the House representation, tempers among several delegates exploded over slavery. When the Convention progressed beyond the personal attacks, it adopted the existing "federal ratio" for taxing states by three-fifths of slaves held.

On August 6, the Committee of Detail reported its proposed revisions to the Randolph Plan. Again the question of slavery came up, and again the question was met with attacks of outrage. Over the next two weeks, delegates wove a web of mutual compromises relating to commerce and trade, east and west, slave-holding and free. The transfer of power to regulate slave trade from states to central government could happen in 20 years, but only then. Later generations could try out their own answers. The delegates were trying to make a government that might last that long.

Migration of the free or "importation" of indentures and slaves could continue by states, defining slaves as persons, not property. Long-term power would change by population as counted every ten years. Apportionment in the House would not be by wealth, it would be by people, the free citizens and three-fifths the number of other persons meaning propertyless slaves and taxed Indian farming families.

In 1806, President Thomas Jefferson sent a message to the 9th Congress on their constitutional opportunity to remove U.S. citizens from the transatlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

" iolatinghuman rights". The 1807 "Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves

The Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807 (, enacted March 2, 1807) is a United States federal law that provided that no new slaves were permitted to be imported into the United States. It took effect on January 1, 1808, the earliest dat ...

" took effect the first instant the Constitution allowed, January 1, 1808. The United States joined the British that year in the first "international humanitarian campaign".

In the 1840–1860 era abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

denounced the Fugitive Slave Clause

The Fugitive Slave Clause in the United States Constitution, also known as either the Slave Clause or the Fugitives From Labor Clause, is Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3, which requires a "person held to service or labor" (usually a slave, appre ...

and other protections of slavery. William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he found ...

famously declared the Constitution "a covenant with death and an agreement with Hell."

In ratification conventions, the anti-slavery delegates sometimes began as anti-ratification votes. Still, the Constitution "as written" was an improvement over the Articles from an abolitionist point of view. The Constitution provided for abolition of the slave trade but the Articles did not. The outcome could be determined gradually over time. Sometimes contradictions among opponents were used to try to gain abolitionist converts. In Virginia, Federalist George Nicholas dismissed fears on both sides. Objections to the Constitution were inconsistent, "At the same moment it is opposed for being promotive and destructive of slavery!" But the contradiction was never resolved peaceably, and the failure to do so contributed to the Civil War.

"Great" Connecticut Compromise

File:Nathaniel Jocelyn - Elbridge Gerry (1744-1814) - 1943.1816 - Harvard Art Museums.jpg, Elbridge Gerry, MA

Chair of the First Committee on Representation

File:Roger Sherman 1721-1793 by Ralph Earl.jpeg, Roger Sherman

Roger Sherman (April 19, 1721 – July 23, 1793) was an American statesman, lawyer, and a Founding Father of the United States. He is the only person to sign four of the great state papers of the United States related to the founding: the Cont ...

, CT

Architect of the Connecticut Compromise

Roger Sherman

Roger Sherman (April 19, 1721 – July 23, 1793) was an American statesman, lawyer, and a Founding Father of the United States. He is the only person to sign four of the great state papers of the United States related to the founding: the Cont ...

(CT), although something of a political broker in Connecticut, proved to a pivotal though unlikely leader at the convention.Luther Martin

Luther Martin (February 20, 1748, New Brunswick, New Jersey – July 10, 1826, New York, New York) was a politician and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, who left the Constitutional Convention early because he felt the Cons ...

(MD) insisted that he would rather divide the Union into regional governments than submit to a consolidated government under the Randolph Plan.

Sherman's proposal came up again for the third time from Oliver Ellsworth

Oliver Ellsworth (April 29, 1745 – November 26, 1807) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, jurist, politician, and diplomat. Ellsworth was a framer of the United States Constitution, United States senator from Connecticut ...

(CT). In the "senate", the states should have equal representation. Advocates said that it could not be agreed to, the union would fall apart somehow. Big states would not be trusted, the small states could confederate with a foreign power showing "more good faith". If delegates could not unite behind this here, one day the states could be united by "some foreign sword". On the question of equal state representation, the Convention adjourned in the same way again, "before a determination was taken in the House.".

On July 2, the convention for the fourth time considered a "senate" with equal state votes. This time a vote was taken, but it stalled again, tied at 5 yes, 5 no, 1 divided. The Convention elected one delegate out of the delegation of each state onto a Committee to make a proposal; it reported July 5. Nothing changed over five days. July 10, Lansing and Yates (NY) quit the Convention in protest over the big state majorities repeatedly overrunning the small state delegations in vote after vote. No direct vote on the basis of 'senate' representation was pushed on the floor for another week.

With delegates unable to reconcile their differences, the Convention elected one delegate from each state to the First Committee on Representation to make a proposal. Unlike debate in the Committee of the Whole, the membership of the committee, led by Elbridge Gerry and including Sherman, was carefully selected and was more sympathetic to the views of the small states.Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

's compromise was that there would be no "property" provision to add representatives, but states with large slave populations would get a bonus added to their free persons by counting three-fifths other ''persons''.

On July 16, Sherman's "Great Compromise" prevailed on its fifth try. Every state was to have equal numbers in the United States Senate. Washington ruled it passed on the vote 5 yes, 4 no, 1 divided. It was not that five states constituted a majority of twelve, but to keep the business moving forward, he relied on precedent established earlier in the Convention that only a majority of states voting was required. The First Committee on Representation and the Connecticut Compromise became the turning point of the convention.

Two new branches

File:Dickinson, John (bust) - NARA - 532841.tif, John Dickinson

John Dickinson (November 13 Julian_calendar">/nowiki>Julian_calendar_November_2.html" ;"title="Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar">/nowiki>Julian calendar November 2">Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar" ...

, DE

for one-person president

The Constitution innovated two branches of government that were not a part of the U.S. government during the Articles of Confederation. Previously, a thirteen-member committee had been left behind in Philadelphia when Congress adjourned to carry out the "executive" functions. Suits between states were referred to the Congress of the Confederation, and treated as a private bill to be determined by majority vote of members attending that day.

On June 7, the "national executive" was taken up in Convention. The "chief magistrate", or 'presidency' was of serious concern for a formerly colonial people fearful of concentrated power in one person. But to secure a "vigorous executive", nationalist delegates such as James Wilson James Wilson may refer to:

Politicians and government officials

Canada

*James Wilson (Upper Canada politician) (1770–1847), English-born farmer and political figure in Upper Canada

* James Crocket Wilson (1841–1899), Canadian MP from Quebe ...

(PA), Charles Pinckney Charles Pinckney may refer to:

* Charles Pinckney (South Carolina chief justice) (died 1758), father of Charles Cotesworth Pinckney

* Colonel Charles Pinckney (1731–1782), South Carolina politician, loyal to British during Revolutionary War, fa ...

(SC), and John Dickenson (DE) favored a single officer. They had someone in mind whom everyone could trust to start off the new system, George Washington.

After introducing the item for discussion, there was a prolonged silence. Benjamin Franklin (Pa) and John Rutledge (SC) had urged everyone to speak their minds freely. When addressing the issue with George Washington in the room, delegates were careful to phrase their objections to potential offenses by officers chosen in the future who would be 'president' "subsequent" to the start-up. Roger Sherman (CT), Edmund Randolph (VA) and Pierce Butler Pierce or Piers Butler may refer to:

*Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormond (c. 1467 – 26 August 1539), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

*Piers Butler, 3rd Viscount Galmoye (1652–1740), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

* P ...

(SC) all objected, preferring two or three persons in the executive, as the ancient Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

had when appointing consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

.

Nathaniel Gorham

Nathaniel Gorham (May 27, 1738 – June 11, 1796; sometimes spelled ''Nathanial'') was an American Founding Father, merchant, and politician from Massachusetts. He was a delegate from the Bay Colony to the Continental Congress and for six months ...

was Chair of the Committee of the Whole, so Washington sat in the Virginia delegation where everyone could see how he voted. The vote for a one-man 'presidency' carried 7-for, 3-against, New York, Delaware and Maryland in the negative. Virginia, along with George Washington, had voted yes. As of that vote for a single 'presidency', George Mason

George Mason (October 7, 1792) was an American planter, politician, Founding Father, and delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787, one of the three delegates present who refused to sign the Constitution. His writings, including s ...

(VA) gravely announced to the floor, that as of that moment, the Confederation's federal government was "in some measure dissolved by the meeting of this Convention."

File:Gilbert Stuart - Portrait of Rufus King (1819-1820) - Google Art Project.jpg, Rufus King, MA

district courts = flexibility

The convention was following the Randolph Plan for an agenda, taking each resolve in turn to move proceedings forward. They returned to items when overnight coalitions required adjustment to previous votes to secure a majority on the next item of business. June 19, and it was Randolph's Ninth Resolve next, about the national court system. On the table was the nationalist proposal for the inferior (lower) courts in the national judiciary.

Pure 1776 republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

had not given much credit to judges, who would set themselves up apart from and sometimes contradicting the state legislature, the voice of the sovereign people. Under the precedent of English Common Law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, bee ...

according to William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Born into a middle-class family i ...

, the legislature, following proper procedure, was for all constitutional purposes, "the people." This dismissal of unelected officers sometimes took an unintended turn among the people. One of John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

's clients believed the First Continental Congress in 1775 had assumed the sovereignty of Parliament, and so abolished all previously established courts in Massachusetts.

In the convention, looking at a national system, Judge Wilson (PA) sought appointments by a single person to avoid legislative payoffs. Judge Rutledge (SC) was against anything but one national court, a Supreme Court to receive appeals from the highest state courts, like the South Carolina court he presided over as Chancellor. Rufus King (MA) thought national district courts in each state would cost less than appeals that otherwise would go to the 'supreme court' in the national capital. National inferior courts passed but making appointments by 'congress' was crossed out and left blank so the delegates could take it up later after "maturer reflection."

Reallocating power

The Constitutional Convention created a new, unprecedented form of government by reallocating powers of government. Every previous national authority had been either a centralized government, or a "confederation of sovereign constituent states." The American power-sharing was unique at the time. The sources and changes of power were up to the states. The foundations of government and extent of power came from both national and state sources. But the new government would have a national operation. To meet their goals of cementing the Union and securing citizen rights, Framers allocated power among executive, senate, house and judiciary of the central government. But each state government in their variety continued exercising powers in their own sphere.

Increase Congress

The Convention did not start with national powers from scratch, it began with the powers already vested in the Congress of the Confederation with control of the military, international relations and commerce. The Constitution added ten more. Five were minor relative to power sharing, including business and manufacturing protections. One important new power authorized Congress to protect states from the "domestic violence" of riot

A riot is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The property targete ...

and civil disorder

Civil disorder, also known as civil disturbance, civil unrest, or social unrest is a situation arising from a mass act of civil disobedience (such as a demonstration, riot, strike, or unlawful assembly) in which law enforcement has difficulty ...

, but it was conditioned by a state request.

The Constitution increased Congressional power to organize, arm and discipline the state militias, to use them to enforce the laws of Congress, suppress rebellions within the states and repel invasions. But the Second Amendment

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds each ...

would ensure that Congressional power could not be used to disarm state militias.

Taxation

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal person, legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regiona ...

substantially increased the power of Congress relative to the states. It was limited by restrictions, forbidding taxes on exports, per capita taxes, requiring import duties to be uniform and that taxes be applied to paying U.S. debt. But the states were stripped of their ability to levy taxes on imports, which was at the time, "by far the most bountiful source of tax revenues".

Congress had no further restrictions relating to political economy

Political economy is the study of how Macroeconomics, economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and Economy, national economies) and Politics, political systems (e.g. law, Institution, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied ph ...

. It could institute protective tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

s, for instance. Congress overshadowed state power regulating interstate commerce

The Commerce Clause describes an enumerated power listed in the United States Constitution ( Article I, Section 8, Clause 3). The clause states that the United States Congress shall have power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and amo ...

; the United States would be the "largest area of free trade in the world." The most undefined grant of power was the power to "make laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution" the Constitution's enumerated powers.

Limit governments

As of ratification, sovereignty was no longer to be theoretically indivisible. With a wide variety of specific powers among different branches of national governments and thirteen republican state governments, now "each of the ''portions'' of powers delegated to the one or to the other ... is ... sovereign ''with regard to its proper objects''". There were some powers that remained beyond the reach of both national powers and state powers, so the logical seat of American "sovereignty" belonged directly with the people-voters of each state.

Besides expanding Congressional power, the Constitution limited states and central government. Six limits on the national government addressed property rights such as slavery and taxes. Six protected liberty such as prohibiting '' ex post facto'' laws and no religious test A religious test is a legal requirement to swear faith to a specific religion or sect, or to renounce the same.

In the United Kingdom

British Test Act of 1673 and 1678

The Test Act of 1673 in England obligated all persons filling any office, ci ...

s for national offices in any state, even if they had them for state offices. Five were principles of a republic, as in legislative appropriation. These restrictions lacked systematic organization, but all constitutional prohibitions were practices that the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative supremacy ...

had "legitimately taken in the absence of a specific denial of the authority."

The regulation of state power presented a "qualitatively different" undertaking. In the state constitutions, the people did not enumerate powers. They gave their representatives every right and authority not explicitly reserved to themselves. The Constitution extended the limits that the states had previously imposed upon themselves under the Articles of Confederation, forbidding taxes on imports and disallowing treaties among themselves, for example.

In light of the repeated abuses by ''ex post facto'' laws passed by the state legislatures, 1783–1787, the Constitution prohibited ''ex post facto'' laws and bills of attainder to protect United States citizen property rights and right to a fair trial

A fair trial is a trial which is "conducted fairly, justly, and with procedural regularity by an impartial judge". Various rights associated with a fair trial are explicitly proclaimed in Article 10 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, th ...

. Congressional power of the purse was protected by forbidding taxes or restraint on interstate commerce and foreign trade. States could make no law "impairing the obligation of contracts." To check future state abuses the framers searched for a way to review and veto state laws harming the national welfare or citizen rights. They rejected proposals for Congressional veto of state laws and gave the Supreme Court appellate case jurisdiction over state law because the Constitution is the supreme law of the land. The United States had such a geographical extent that it could only be safely governed using a combination of republics. Federal judicial districts would follow those state lines.

Population power

The British had relied upon a concept of "virtual representation

Virtual representation was the idea that the members of Parliament, including the Lords and the Crown-in-Parliament, reserved the right to speak for the interests of all British subjects, rather than for the interests of only the district that ele ...

" to give legitimacy to their House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

. According to many in Parliament, it was not necessary to elect anyone from a large port city, or the American colonies, because the representatives of "rotten boroughs

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act 1832, which had a very small electora ...

", mostly abandoned medieval fair towns with twenty voters, "virtually represented" them. Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

in the colonies was second in population only to London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

.

"They were all Englishmen, supposed to be a single people, with one definable interest. Legitimacy came from membership in Parliament of the sovereign realm, not elections from people. As Blackstone explained, the Member is "not bound ... to consult with, or take the advice, of his constituents." As Constitutional historian Gordon Wood elaborated, "The Commons of England contained all of the people's power and were considered to be the very persons of the people they represented."

File:Gouverneur Morris 1753.png, G. Morris, PA

provinces forever

While the English "virtual representation" was hardening into a theory of parliamentary sovereignty

Parliamentary sovereignty, also called parliamentary supremacy or legislative supremacy, is a concept in the constitutional law of some parliamentary democracies. It holds that the legislative body has absolute sovereignty and is supreme over all ...

, the American theory of representation was moving towards a theory of sovereignty of the people. In their new constitutions written since 1776, Americans required community residency of voters and representatives, expanded suffrage, and equalized populations in voting districts. There was a sense that representation "had to be proportioned to the population." The convention would apply the new principle of "sovereignty of the people" both to the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

, and to the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

.

=House changes

=

Once the Great Compromise was reached, delegates in Convention then agreed to a decennial census to count the population. The Americans themselves did not allow for universal suffrage for all adults. Their sort of "virtual representation" said that those voting in a community could understand and themselves represent non-voters when they had like interests that were unlike other political communities. There were enough differences among people in different American communities for those differences to have a meaningful social and economic reality. Thus New England colonial legislatures would not tax communities which had not yet elected representatives. When the royal governor of Georgia refused to allow representation to be seated from four new counties, the legislature refused to tax them.

The 1776 Americans had begun to demand expansion of the franchise, and in each step, they found themselves pressing towards a philosophical "actuality of consent." The Convention determined that the power of the people, should be felt in the House of Representatives. For the U.S. Congress, persons alone were counted. Property was not counted.

=Senate changes

=

The Convention found it more difficult to give expression to the will of the people in new states. What state might be "lawfully arising" outside the boundaries of the existing thirteen states? The new government was like the old, to be made up of pre-existing states. Now there was to be admission of new states. Regular order would provide new states by state legislatures for Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

and Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

. But the Congress of the Confederation had by its Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

presented the convention with a new issue. Settlers in the Northwest Territory might one day constitute themselves into "no more than five" states. More difficult still, most delegates anticipated adding alien peoples of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

and Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

to United States territory. Generally in American history, European citizens of empire were given U.S. citizenship on territorial acquisition. Should they become states?

Some delegates were reluctant to expand into any so "remote wilderness". It would retard the commercial development of the east. They would be easily influenced, "foreign gold" would corrupt them. Western peoples were the least desirable Americans, only good for perpetual provinces. There were so many foreigners moving out west, there was no telling how things would turn out. These were poor people, they could not pay their fair share of taxes. It would be "suicide" for the original states. New states could become a majority in the Senate, they would abuse their power, "enslaving" the original thirteen. If they also loved liberty, and could not tolerate eastern state dominance, they would be justified in civil war. Western trade interests could drag the country into an inevitable war with Spain for the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. As time wore on, any war for the Mississippi River was obviated by the 1803 Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

and the 1812 American victory at New Orleans.

Even if there were to be western states, a House representation of 40,000 might be too small, too easy for the westerners. "States" had been declared out west already. They called themselves republics, and set up their own courts directly from the people without colonial charters. In Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

, Westsylvania

Westsylvania was a proposed state of the United States located in what is now West Virginia, southwestern Pennsylvania, and small parts of Kentucky, Maryland, and Virginia. First proposed early in the American Revolution, Westsylvania would have ...

, Franklin

Franklin may refer to:

People

* Franklin (given name)

* Franklin (surname)

* Franklin (class), a member of a historical English social class

Places Australia

* Franklin, Tasmania, a township

* Division of Franklin, federal electoral d ...

, and Vandalia, "legislatures" met with emissaries from British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and Spanish empires in violation of the Articles of Confederation, just as the sovereign states had done. In the Constitution as written, no majorities in Congress could break up the larger states without their consent.

"New state" advocates had no fear of western states achieving a majority one day. For example, the British sought to curb American expansion, which caused the angered colonists to agitate for independence. Follow the same rule, get the same results. Congress has never been able to discover a better rule than majority rule. If they grow, let them rule. As they grow, they must get all their supplies from eastern businesses. Character is not determined by points of a compass. States admitted are equals, they will be made up of our brethren. Commit to right principles, even if the right way, one day, benefits other states. They will be free like ourselves, their pride will not allow anything but equality.

It was at this time in the Convention that Reverend Manasseh Cutler

Manasseh Cutler (May 13, 1742 – July 28, 1823) was an American clergyman involved in the American Revolutionary War. He was influential in the passage of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and wrote the section prohibiting slavery in the Nort ...

arrived to lobby for western land sales. He brought acres of land grants to parcel out. Their sales would fund most of the U.S. government expenditures for its first few decades. There were allocations for the Ohio Company stockholders at the convention, and for others delegates too. Good to his word, in December 1787, Cutler led a small band of pioneers into the Ohio Valley.

The provision for admitting new states became relevant at the purchase of the Louisiana Territory

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805, until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed the Missouri Territory. The territory was formed out of the ...

from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...