History Of The Anti-nuclear Movement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The application of nuclear technology, both as a source of energy and as an instrument of war, has been controversial.Robert Benford

The application of nuclear technology, both as a source of energy and as an instrument of war, has been controversial.Robert Benford

The Anti-nuclear Movement (book review)

''American Journal of Sociology'', Vol. 89, No. 6, (May 1984), pp. 1456-1458. Scientists and diplomats have debated nuclear weapons policy since before the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in 1945. The public became concerned about

Review of Critical Masses

''Journal of Political Ecology'', Vol 6, 1999. and in the late 1960s some members of the scientific community began to express their concerns. In the early 1970s, there were large protests about a proposed nuclear power plant in

In 1945 in the

In 1945 in the

Recollections of Nevada's Nuclear Past

''UNLV FUSION'', 2005, p. 20.

/ref> The Aldermaston marches continued into the late 1960s when tens of thousands of people took part in the four-day marches. In 1959, a letter in the ''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'' was the start of a successful campaign to stop the Atomic Energy Commission dumping

In the United States, the first commercially viable nuclear power plant was to be built at Bodega Bay, north of

In the United States, the first commercially viable nuclear power plant was to be built at Bodega Bay, north of

No Nukes: Everyone's Guide to Nuclear Power"> No Nukes: Everyone's Guide to Nuclear Power

South End Press, , p. 383. The emergence of the anti-nuclear power movement was "closely associated with the general rise in environmental consciousness which had started to materialize in the USA in the 1960s and quickly spread to other Western industrialized countries". Some nuclear experts began to voice dissenting views about nuclear power in 1969, and this was a necessary precondition for broad public concern about nuclear power to emerge.Wolfgang Rudig (1990). ''Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy'', Longman, p. 52. These scientists included

The Atom Besieged: Antinuclear Movements in France and Germany

'', ASIN: B0011LXE0A, p. 3. Also in 1971, the town of

Public Acceptance of New Technologies

Routledge, pp. 375-376.Robert Gottlieb (2005)

Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement

Revised Edition, Island Press, USA, p. 237.

/ref> but the Wyhl occupation generated ongoing debate. This initially centred on the state government's handling of the affair and associated police behaviour, but interest in nuclear issues was also stimulated. The Wyhl experience encouraged the formation of citizen action groups near other planned nuclear sites. Many other anti-nuclear groups formed elsewhere, in support of these local struggles, and some existing citizen action groups widened their aims to include the nuclear issue. Anti-nuclear success at Wyhl also inspired nuclear opposition in the rest of Europe and North America. In 1972, the anti-nuclear weapons movement maintained a presence in the Pacific, largely in response to

Nuclear Disarmament Activism in Asia and the Pacific, 1971-1996

''The Asia-Pacific Journal'', Vol. 25-5-09, June 22, 2009. In Australia, thousands joined protest marches in Adelaide, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Sydney. Scientists issued statements demanding an end to the tests; unions refused to load French ships, service French planes, or carry French mail; and consumers boycotted French products. In Fiji, activists formed an Against Testing on

''Ocala Star-Banner'', January 4, 1981. The Montague project was canceled in 1980, after $29 million was spent on the project. By the mid-1970s anti-nuclear activism had moved beyond local protests and politics to gain a wider appeal and influence. Although it lacked a single co-ordinating organization, and did not have uniform goals, the movement's efforts gained a great deal of attention.Walker, J. Samuel (2004).

Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective

' (Berkeley: University of California Press), pp. 10-11.

Political Opportunity and Political Protest: Anti-Nuclear Movements in Four Democracies

''British Journal of Political Science'', Vol. 16, No. 1, 1986, p. 71. In West Germany, between February 1975 and April 1979, some 280,000 people were involved in seven demonstrations at nuclear sites. Several site occupations were also attempted. In the aftermath of the

Amplifying Public Opinion: The Policy Impact of the U.S. Environmental Movement

p. 7.Social Protest and Policy Change

p. 45. On June 12, 1982, one million people demonstrated in New York City's

The Spirit of June 12

''The Nation'', July 2, 2007.1982 - a million people march in New York City

International Day of Nuclear Disarmament protests were held on June 20, 1983 at 50 sites across the United States.Harvey Klehr

Far Left of Center: The American Radical Left Today

Transaction Publishers, 1988, p. 150.1,400 Anti-nuclear protesters arrested

''Miami Herald'', June 21, 1983. In 1986, hundreds of people walked from

''Gainesville Sun'', November 16, 1986. There were many Nevada Desert Experience protests and peace camps at the

438 Protesters are Arrested at Nevada Nuclear Test Site

''New York Times'', February 6, 1987.

''New York Times'', April 20, 1992. On May 1, 2005, 40,000 anti-nuclear/anti-war protesters marched past the United Nations in New York, 60 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.Anti-Nuke Protests in New York

'' Fox News'', May 2, 2005. This was the largest anti-nuclear rally in the U.S. for several decades. In Britain, there were many protests about the government's proposal to replace the aging Trident weapons system with a newer model. The largest protest had 100,000 participants and, according to polls, 59 percent of the public opposed the move. Lawrence S. Wittner

A rebirth of the anti-nuclear weapons movement? Portents of an anti-nuclear upsurge

''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'', 7 December 2007. The International Conference on Nuclear Disarmament took place inA-bomb survivors join 25,000-strong anti-nuclear march through New York

''Mainichi Daily News'', May 4, 2010.

The application of nuclear technology, both as a source of energy and as an instrument of war, has been controversial.Robert Benford

The application of nuclear technology, both as a source of energy and as an instrument of war, has been controversial.Robert BenfordThe Anti-nuclear Movement (book review)

''American Journal of Sociology'', Vol. 89, No. 6, (May 1984), pp. 1456-1458. Scientists and diplomats have debated nuclear weapons policy since before the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in 1945. The public became concerned about

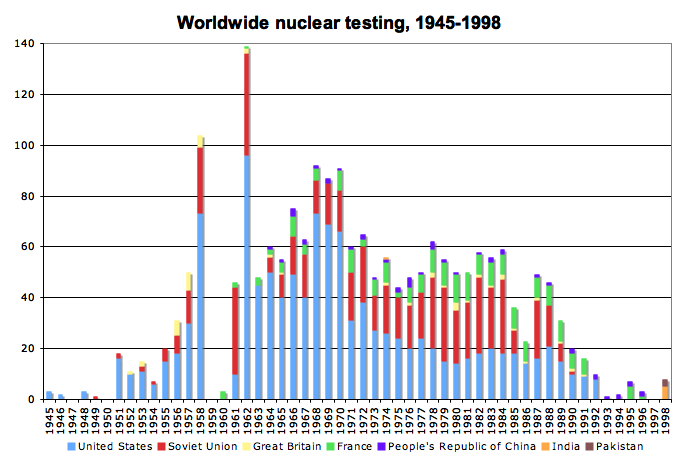

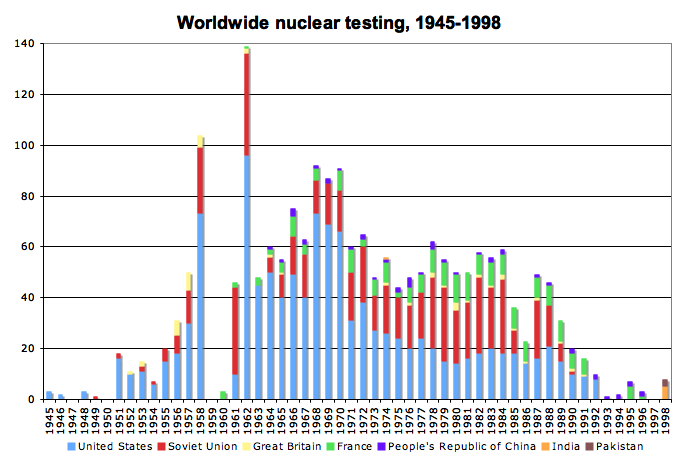

nuclear weapons testing

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

from about 1954, following extensive nuclear testing in the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

. In 1961, at the height of the Cold War, about 50,000 women brought together by Women Strike for Peace

Women Strike for Peace (WSP, also known as Women for Peace) was a women's peace activist group in the United States. In 1961, nearing the height of the Cold War, around 50,000 women marched in 60 cities around the United States to demonstrate ag ...

marched in 60 cities in the United States to demonstrate against nuclear weapons. In 1963, many countries ratified the Partial Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those conducted ...

which prohibited atmospheric nuclear testing.

Some local opposition to nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced ...

emerged in the early 1960s,Paula GarbReview of Critical Masses

''Journal of Political Ecology'', Vol 6, 1999. and in the late 1960s some members of the scientific community began to express their concerns. In the early 1970s, there were large protests about a proposed nuclear power plant in

Wyhl

Wyhl () is a municipality in the district of Emmendingen in Baden-Württemberg in southwestern Germany.

It is known in the 1970s for its role in the anti-nuclear movement. Wyhl was first mentioned in 1971 as a possible site for a nuclear power st ...

, Germany. The project was cancelled in 1975 and anti-nuclear success at Wyhl inspired opposition to nuclear power in other parts of Europe and North America. Nuclear power became an issue of major public protest in the 1970s.Jim Falk (1982). ''Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power'', Oxford University Press, pp. 95-96.

Early years

In 1945 in the

In 1945 in the New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

desert, American scientists conducted "Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

," the first nuclear weapons test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

, marking the beginning of the atomic age

The Atomic Age, also known as the Atomic Era, is the period of history following the detonation of the first nuclear weapon, The Gadget at the ''Trinity'' test in New Mexico, on July 16, 1945, during World War II. Although nuclear chain reaction ...

. Even before the Trinity test, national leaders debated the impact of nuclear weapons on domestic and foreign policy. Also involved in the debate about nuclear weapons policy was the scientific community, through professional associations such as the Federation of Atomic Scientists

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is an American nonprofit global policy think tank with the stated intent of using science and scientific analysis to attempt to make the world more secure. FAS was founded in 1946 by scientists who wo ...

and the Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs.

On August 6, 1945, towards the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, the Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

device was detonated over the Japanese military city of Hiroshima. Exploding with a yield equivalent to 12,500 tonnes of TNT

Trinitrotoluene (), more commonly known as TNT, more specifically 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, and by its preferred IUPAC name 2-methyl-1,3,5-trinitrobenzene, is a chemical compound with the formula C6H2(NO2)3CH3. TNT is occasionally used as a reagen ...

, the blast and thermal wave of the bomb destroyed nearly 50,000 buildings (including the headquarters of the 2nd General Army and Fifth Division) and killed approximately 75,000 people, among them 20,000 Japanese soldiers and 20,000 Korean slave laborers. Detonation of the Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

device exploded over the Japanese industrial city of Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole Nanban trade, port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hi ...

three days later after Hiroshima, destroying 60% of the city and killing approximately 35,000 people, among them 23,200–28,200 Japanese munitions workers, 2,000 Korean slave laborers, and 150 Japanese soldiers. The two bombings remains the only events where nuclear weapons have been used in combat. Subsequently, the world's nuclear weapons stockpiles grew.Mary Palevsky, Robert Futrell, and Andrew KirkRecollections of Nevada's Nuclear Past

''UNLV FUSION'', 2005, p. 20.

Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

was a series of nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

tests conducted by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese: , , meaning "coconut place"), sometimes known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 1800s and 1946 is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. After the Seco ...

in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contin ...

in the summer of 1946. Its purpose was to test the effect of nuclear weapons on naval ships. Pressure to cancel Operation Crossroads came from scientists and diplomats. Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

scientists argued that further nuclear testing was unnecessary and environmentally dangerous. A Los Alamos study warned "the water near a recent surface explosion will be a witch's brew" of radioactivity. To prepare the atoll for the nuclear tests, Bikini's native residents were evicted from their homes and resettled on smaller, uninhabited islands where they were unable to sustain themselves.

Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when a Hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific contaminated the crew of the Japanese fishing boat '' Lucky Dragon''. One of the fishermen died in Japan seven months later. The incident caused widespread concern around the world and "provided a decisive impetus for the emergence of the anti-nuclear weapons movement in many countries".Wolfgang Rudig (1990). ''Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy'', Longman, p. 54-55. The anti-nuclear weapons movement grew rapidly because for many people the atomic bomb "encapsulated the very worst direction in which society was moving".Jim Falk (1982). ''Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power'', Oxford University Press, pp. 96-97.

Peace movements emerged in Japan and in 1954 they converged to form a unified "Japanese Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs". Japanese opposition to the Pacific nuclear weapons tests was widespread, and "an estimated 35 million signatures were collected on petitions calling for bans on nuclear weapons".

German publications of the 1950s and 1960s contained criticism of some features of nuclear power including its safety. Nuclear waste disposal was widely recognized as a major problem, with concern publicly expressed as early as 1954. In 1964, one author went so far as to state "that the dangers and costs of the necessary final disposal of nuclear waste could possibly make it necessary to forego the development of nuclear energy".Wolfgang Rudig (1990). ''Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy'', Longman, p. 63.

The Russell–Einstein Manifesto

The Russell–Einstein Manifesto was issued in London on 9 July 1955 by Bertrand Russell in the midst of the Cold War. It highlighted the dangers posed by nuclear weapons and called for world leaders to seek peaceful resolutions to international ...

was issued in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

on July 9, 1955 by Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

in the midst of the Cold War. It highlighted the dangers posed by nuclear weapons and called for world leaders to seek peaceful resolutions to international conflict. The signatories included eleven pre-eminent intellectuals and scientists, including Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

, who signed it just days before his death on April 18, 1955. A few days after the release, philanthropist Cyrus S. Eaton offered to sponsor a conference—called for in the manifesto—in Pugwash, Nova Scotia

Pugwash is an incorporated village in Cumberland County, Nova Scotia, Canada, located on the Northumberland Strait at the mouth of the Pugwash River. It had a population of 746 as of the 2021 census. The name Pugwash is derived from the Mi' ...

, Eaton's birthplace. This conference was to be the first of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs

The Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs is an international organization that brings together scholars and public figures to work toward reducing the danger of armed conflict and to seek solutions to global security threats. It was f ...

, held in July 1957.

In the United Kingdom, the first Aldermaston March

The Aldermaston marches were anti-nuclear weapons demonstrations in the 1950s and 1960s, taking place on Easter weekend between the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston in Berkshire, England, and London, over a distance of fifty- ...

organised by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) is an organisation that advocates unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom, international nuclear disarmament and tighter international arms regulation through agreements such as the Nuc ...

took place at Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

1958, when several thousand people marched for four days from Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

, London, to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment close to Aldermaston

Aldermaston is a village and civil parish in Berkshire, England. In the 2011 Census, the parish had a population of 1015. The village is in the Kennet Valley and bounds Hampshire to the south. It is approximately from Newbury, Basingsto ...

in Berkshire, England, to demonstrate their opposition to nuclear weapons.A brief history of CND/ref> The Aldermaston marches continued into the late 1960s when tens of thousands of people took part in the four-day marches. In 1959, a letter in the ''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'' was the start of a successful campaign to stop the Atomic Energy Commission dumping

radioactive waste

Radioactive waste is a type of hazardous waste that contains radioactive material. Radioactive waste is a result of many activities, including nuclear medicine, nuclear research, nuclear power generation, rare-earth mining, and nuclear weapons r ...

in the sea 19 kilometres from Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

.

On November 1, 1961, at the height of the Cold War, about 50,000 women brought together by Women Strike for Peace

Women Strike for Peace (WSP, also known as Women for Peace) was a women's peace activist group in the United States. In 1961, nearing the height of the Cold War, around 50,000 women marched in 60 cities around the United States to demonstrate ag ...

marched in 60 cities in the United States to demonstrate against nuclear weapons. It was the largest national women's peace protest of the 20th century.

In 1958, Linus Pauling and his wife presented the United Nations with the petition signed by more than 11,000 scientists calling for an end to nuclear-weapon testing. The "Baby Tooth Survey

The Baby Tooth Survey was initiated by the Greater St. Louis Citizens' Committee for Nuclear Information in conjunction with Saint Louis University and the Washington University School of Dental Medicine as a means of determining the effects of nuc ...

," headed by Dr Louise Reiss

Louise Marie Zibold Reiss (February 23, 1920 – January 1, 2011) was an American physician who coordinated what became known as the Baby Tooth Survey, in which deciduous teeth from children living in the St. Louis, Missouri, area who were bor ...

, demonstrated conclusively in 1961 that above-ground nuclear testing posed significant public health risks in the form of radioactive fallout

Nuclear fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and the shock wave has passed. It commonly refers to the radioac ...

spread primarily via milk from cows that had ingested contaminated grass. Public pressure and the research results subsequently led to a moratorium on above-ground nuclear weapons testing, followed by the Partial Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those conducted ...

, signed in 1963 by John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

and Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

. On the day that the treaty went into force, the Nobel Prize Committee awarded Pauling the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

, describing him as "Linus Carl Pauling, who ever since 1946 has campaigned ceaselessly, not only against nuclear weapons tests, not only against the spread of these armaments, not only against their very use, but against all warfare as a means of solving international conflicts."Jerry Brown and Rinaldo Brutoco

Rinaldo S. Brutoco (born in Toronto, Canada on February 27, 1947) is an attorney and corporate executive. He was raised in Southern California and has remained in California ever since.

Education

In 1968, Brutoco graduated from Santa Clara ...

(1997). ''Profiles in Power: The Anti-nuclear Movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age'', Twayne Publishers, pp. 191-192.

Pauling started the International League of Humanists

International League of Humanists (ILH) is a non-profit international association of eminent humanists. Its headquarters are in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina and its primary objective is promotion of worldwide peace and human rights. Its curr ...

in 1974. He was president of the scientific advisory board of the World Union for Protection of Life

The World Union for Protection of Life (German: ''Weltbund zum Schutz des Lebens'', French: ''Union Mondiale pour la Protection de la Vie'', Russian: Всемирный союз для защиты жизни) is an international non-profit organ ...

and also one of the signatories of the Dubrovnik-Philadelphia Statement.

After the Partial Test Ban Treaty

In the United States, the first commercially viable nuclear power plant was to be built at Bodega Bay, north of

In the United States, the first commercially viable nuclear power plant was to be built at Bodega Bay, north of San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

, but the proposal was controversial and conflict with local citizens began in 1958. The proposed plant site was close to the San Andreas Fault

The San Andreas Fault is a continental transform fault that extends roughly through California. It forms the tectonic boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate, and its motion is right-lateral strike-slip (horizonta ...

and close to the region's environmentally sensitive fishing and dairy industries. The Sierra Club became actively involved. The conflict ended in 1964, with the forced abandonment of plans for the power plant. Historian Thomas Wellock

Thomas Wellock (born 1959) is the American historian for the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Trained as both an engineer and a historian, he writes scholarly histories of the regulation of commercial nuclear energy. His most recent book is ' ...

traces the birth of the anti-nuclear movement to the controversy over Bodega Bay. Attempts to build a nuclear power plant in Malibu were similar to those at Bodega Bay and were also abandoned.

In 1966, Larry Bogart founded the Citizens Energy Council, a coalition of environmental groups that published the newsletters "Radiation Perils," "Watch on the A.E.C." and "Nuclear Opponents". These publications argued that "nuclear power plants were too complex, too expensive and so inherently unsafe they would one day prove to be a financial disaster and a health hazard".Anna Gyorgy (1980)No Nukes: Everyone's Guide to Nuclear Power"> No Nukes: Everyone's Guide to Nuclear Power

South End Press, , p. 383. The emergence of the anti-nuclear power movement was "closely associated with the general rise in environmental consciousness which had started to materialize in the USA in the 1960s and quickly spread to other Western industrialized countries". Some nuclear experts began to voice dissenting views about nuclear power in 1969, and this was a necessary precondition for broad public concern about nuclear power to emerge.Wolfgang Rudig (1990). ''Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy'', Longman, p. 52. These scientists included

Ernest Sternglass

Ernest Joachim Sternglass (24 September 1923 – 12 February 2015) was a professor emeritus at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the Radiation and Public Health Project. He is an American physicist and author, best known for his contr ...

from Pittsburg, Henry Kendall from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Nobel laureate George Wald and radiation specialist Rosalie Bertell

Rosalie Bertell (April 4, 1929 – June 14, 2012) was an American scientist, author, environmental activist, epidemiologist, and Catholic nun. Bertell was a sister of the Grey Nuns of the Sacred Heart, best known for her work in the field of ioniz ...

. These members of the scientific community "by expressing their concern over nuclear power, played a crucial role in demystifying the issue for other citizens", and nuclear power became an issue of major public protest in the 1970s.

In 1971, 15,000 people demonstrated against French plans to locate the first light-water reactor power plant in Bugey The Bugey (, ; Arpitan: ''Bugê'') is a historical region in the department of Ain, eastern France, located between Lyon and Geneva. It is located in a loop of the Rhône River in the southeast of the department. It includes the foothills of the ...

. This was the first of a series of mass protests organized at nearly every planned nuclear site in France.Dorothy Nelkin and Michael Pollak (1982). The Atom Besieged: Antinuclear Movements in France and Germany

'', ASIN: B0011LXE0A, p. 3. Also in 1971, the town of

Wyhl

Wyhl () is a municipality in the district of Emmendingen in Baden-Württemberg in southwestern Germany.

It is known in the 1970s for its role in the anti-nuclear movement. Wyhl was first mentioned in 1971 as a possible site for a nuclear power st ...

, in Germany, was a proposed site for a nuclear power station. In the years that followed, public opposition steadily mounted, and there were large protests. Television coverage of police dragging away farmers and their wives helped to turn nuclear power into a major issue. In 1975, an administrative court withdrew the construction licence for the plant,Stephen Mills and Roger Williams (1986)Public Acceptance of New Technologies

Routledge, pp. 375-376.Robert Gottlieb (2005)

Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement

Revised Edition, Island Press, USA, p. 237.

/ref> but the Wyhl occupation generated ongoing debate. This initially centred on the state government's handling of the affair and associated police behaviour, but interest in nuclear issues was also stimulated. The Wyhl experience encouraged the formation of citizen action groups near other planned nuclear sites. Many other anti-nuclear groups formed elsewhere, in support of these local struggles, and some existing citizen action groups widened their aims to include the nuclear issue. Anti-nuclear success at Wyhl also inspired nuclear opposition in the rest of Europe and North America. In 1972, the anti-nuclear weapons movement maintained a presence in the Pacific, largely in response to

French nuclear testing

''Gerboise Bleue'' (; ) was the codename of the first French nuclear test. It was conducted by the Nuclear Experiments Operational Group (GOEN), a unit of the Joint Special Weapons Command on 13 February 1960, at the Saharan Military Experimen ...

there. Activists, including David McTaggart

David Fraser McTaggart (June 24, 1932 – March 23, 2001) was a Canadian-born environmentalist who played a central part in the foundation of Greenpeace International.

An excellent all-around athlete, as a young man he won three consecutive Cana ...

from Greenpeace, defied the French government by sailing small vessels into the test zone and interrupting the testing program.Lawrence S. WittnerNuclear Disarmament Activism in Asia and the Pacific, 1971-1996

''The Asia-Pacific Journal'', Vol. 25-5-09, June 22, 2009. In Australia, thousands joined protest marches in Adelaide, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Sydney. Scientists issued statements demanding an end to the tests; unions refused to load French ships, service French planes, or carry French mail; and consumers boycotted French products. In Fiji, activists formed an Against Testing on

Mururoa

Moruroa (Mururoa, Mururura), also historically known as Aopuni, is an atoll which forms part of the Tuamotu Archipelago in French Polynesia in the southern Pacific Ocean. It is located about southeast of Tahiti. Administratively Moruroa Atoll i ...

organization.

In Spain, in response to a surge in nuclear power plant proposals in the 1960s, a strong anti-nuclear movement emerged in 1973, which ultimately impeded the realisation of most of the projects.Lutz Mez, Mycle Schneider

Mycle Schneider (pronounced ''Michael'', /ˈmaɪkəl/) (born 1959 in Cologne) is a Paris-based nuclear energy consultant and anti-nuclear activist. He is the lead author of '' The World Nuclear Industry Status Reports''. He has advised members o ...

and Steve Thomas (Eds.) (2009). ''International Perspectives of Energy Policy and the Role of Nuclear Power'', Multi-Science Publishing Co. Ltd, p. 371.

In 1974, organic farmer Sam Lovejoy took a crowbar to the weather-monitoring tower which had been erected at the Montague Nuclear Power Plant

The Montague Nuclear Power Plant was a proposed nuclear power plant to be located in Montague, Massachusetts. The plant was to consist of two 1150 MWe General Electric boiling water reactors. The project was proposed in 1973 and canceled in 1980, a ...

site. Lovejoy felled the tower and then took himself to the local police station, where he took full responsibility for the action. Lovejoy's action galvanized local public opinion against the plant.Utilities Drop Nuclear Power Plant Plans''Ocala Star-Banner'', January 4, 1981. The Montague project was canceled in 1980, after $29 million was spent on the project. By the mid-1970s anti-nuclear activism had moved beyond local protests and politics to gain a wider appeal and influence. Although it lacked a single co-ordinating organization, and did not have uniform goals, the movement's efforts gained a great deal of attention.Walker, J. Samuel (2004).

Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective

' (Berkeley: University of California Press), pp. 10-11.

Jim Falk

Jim Falk (born ) is a physicist and academic researcher on science and technology studies.

Background

Falk was born in Oxford, England. His father was the philosopher Werner D. Falk (latterly professor at the University of North Carolina), and h ...

has suggested that popular opposition to nuclear power quickly grew into an effective anti-nuclear power movement in the 1970s. In some countries, the nuclear power conflict "reached an intensity unprecedented in the history of technology controversies".

In France, between 1975 and 1977, some 175,000 people protested against nuclear power in ten demonstrations.Herbert P. KitscheltPolitical Opportunity and Political Protest: Anti-Nuclear Movements in Four Democracies

''British Journal of Political Science'', Vol. 16, No. 1, 1986, p. 71. In West Germany, between February 1975 and April 1979, some 280,000 people were involved in seven demonstrations at nuclear sites. Several site occupations were also attempted. In the aftermath of the

Three Mile Island accident

The Three Mile Island accident was a partial meltdown of the Three Mile Island, Unit 2 (TMI-2) reactor in Pennsylvania, United States. It began at 4 a.m. on March 28, 1979. It is the most significant accident in U.S. commercial nuclea ...

in 1979, some 120,000 people attended a demonstration against nuclear power in Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ru ...

.

In May 1979, an estimated 70,000 people, including the governor of California, attended a march and rally against nuclear power in Washington, D.C.Jon AgnoneAmplifying Public Opinion: The Policy Impact of the U.S. Environmental Movement

p. 7.Social Protest and Policy Change

p. 45. On June 12, 1982, one million people demonstrated in New York City's

Central Park

Central Park is an urban park in New York City located between the Upper West and Upper East Sides of Manhattan. It is the fifth-largest park in the city, covering . It is the most visited urban park in the United States, with an estimated ...

against nuclear weapons and for an end to the cold war arms race. It was, and is, the largest anti-nuclear protest

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration or remonstrance) is a public expression of objection, disapproval or dissent towards an idea or action, typically a political one.

Protests can be thought of as acts of cooper ...

and the largest peace demonstration in American history.Jonathan SchellThe Spirit of June 12

''The Nation'', July 2, 2007.1982 - a million people march in New York City

International Day of Nuclear Disarmament protests were held on June 20, 1983 at 50 sites across the United States.Harvey Klehr

Far Left of Center: The American Radical Left Today

Transaction Publishers, 1988, p. 150.1,400 Anti-nuclear protesters arrested

''Miami Herald'', June 21, 1983. In 1986, hundreds of people walked from

Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

to Washington DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

in the Great Peace March for Global Nuclear Disarmament.Hundreds of Marchers Hit Washington in Finale of Nationwaide Peace March''Gainesville Sun'', November 16, 1986. There were many Nevada Desert Experience protests and peace camps at the

Nevada Test Site

The Nevada National Security Site (N2S2 or NNSS), known as the Nevada Test Site (NTS) until 2010, is a United States Department of Energy (DOE) reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about 65 miles (105 km) northwest of the ...

during the 1980s and 1990s.Robert Lindsey438 Protesters are Arrested at Nevada Nuclear Test Site

''New York Times'', February 6, 1987.

''New York Times'', April 20, 1992. On May 1, 2005, 40,000 anti-nuclear/anti-war protesters marched past the United Nations in New York, 60 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.Anti-Nuke Protests in New York

'' Fox News'', May 2, 2005. This was the largest anti-nuclear rally in the U.S. for several decades. In Britain, there were many protests about the government's proposal to replace the aging Trident weapons system with a newer model. The largest protest had 100,000 participants and, according to polls, 59 percent of the public opposed the move. Lawrence S. Wittner

A rebirth of the anti-nuclear weapons movement? Portents of an anti-nuclear upsurge

''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'', 7 December 2007. The International Conference on Nuclear Disarmament took place in

Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population ...

in February 2008, and was organized by The Government of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

, the Nuclear Threat Initiative and the Hoover Institute

The Hoover Institution (officially The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace; abbreviated as Hoover) is an American public policy think tank and research institution that promotes personal and economic liberty, free enterprise, and ...

. The Conference was entitled ''Achieving the Vision of a World Free of Nuclear Weapons'' and had the purpose of building consensus between nuclear weapon states and non-nuclear weapon states in relation to the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT, is an international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperation ...

.

In May 2010, some 25,000 people, including members of peace organizations and 1945 atomic bomb survivors, marched for about two kilometers from downtown New York to the United Nations headquarters, calling for the elimination of nuclear weapons.''Mainichi Daily News'', May 4, 2010.

Other issues

Early anti-nuclear advocates expressed the view that affluent lifestyles on a global scale strain the viability of the natural environment and that nuclear energy would enable those lifestyles. Examples of such expressions are:See also

* Debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki *Nuclear power debate

The nuclear power debate is a long-running controversy about the risks and benefits of using nuclear reactors to generate electricity for civilian purposes. The debate about nuclear power peaked during the 1970s and 1980s, as more and more reac ...

* Nuclear weapons debate

The nuclear weapons debate refers to the controversies surrounding the threat, use and stockpiling of nuclear weapons. Even before the first nuclear weapons had been developed, scientists involved with the Manhattan Project were divided over the u ...

* The Bomb (film)

* Uranium mining debate

The uranium mining debate covers the political and environmental controversies of uranium mining for use in either nuclear power or nuclear weapons.

Background and public debate

As of 2009, in terms of uranium production, Kazakhstan was the la ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of The Anti-Nuclear Movement Anti-nuclear movement Nuclear weapons policy Technology in society Cold War history of the United States