Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

is one of the 50 states of the United States. What is now Tennessee was initially part of

North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

, and later part of the

Southwest Territory

The Territory South of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Southwest Territory, was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 26, 1790, until June 1, 1796, when it was admitted to the United States a ...

. It was

admitted to the Union on June 1, 1796, as the 16th state. Tennessee would earn the nickname "The Volunteer State" during the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, when many Tennesseans would step in to help with the war effort. Especially during the Americans victory at the

Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

in 1815. The nickname would become even more applicable during the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

in 1846, after the Secretary of War asked the state for 2,800 soldiers, and Tennessee sent over 30,000 volunteers.

Tennessee was the last state to formally leave the

Union and join the

Confederacy at the outbreak of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

in 1861. With

Nashville

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and th ...

occupied by Union forces from 1862, it was the first state to be readmitted to the Union at the end of the war. During the Civil War, Tennessee would furnish the second most soldiers for the Confederate Army, behind

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

. Tennessee would also supply more

units of soldiers for the

Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

than any other state within the Confederacy, with

East Tennessee

East Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee defined in state law. Geographically and socioculturally distinct, it comprises approximately the eastern third of the U.S. state of Tennessee. East Tennessee consists of 33 count ...

being a

Unionist stronghold. During the

Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

, the state had competitive party politics, but a Democratic takeover in the late 1880s resulted in passage of

disenfranchisement laws that excluded most blacks and many poor whites from voting, with the exception of Memphis. This sharply reduced competition in politics in the state until after passage of civil rights legislation in the mid-20th century.

During the early

20th century

The 20th (twentieth) century began on

January 1, 1901 ( MCMI), and ended on December 31, 2000 ( MM). The 20th century was dominated by significant events that defined the modern era: Spanish flu pandemic, World War I and World War II, nucle ...

, Tennessee would transition from an agrarian economy based on tobacco and cotton, to a more diversified economy. This was aided in part by massive federal investment in the

Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolin ...

created by

Franklin D. Roosevelt's

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

, helping the TVA become the nation's largest

public utility

A public utility company (usually just utility) is an organization that maintains the infrastructure for a public service (often also providing a service using that infrastructure). Public utilities are subject to forms of public control and r ...

provider. The huge electricity supply made possible the establishment of the city of

Oak Ridge to house the

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

's uranium enrichment facilities, helping to build the

world's first atomic bombs. In 2016, the element

tennessine

Tennessine is a synthetic chemical element with the symbol Ts and atomic number 117. It is the second-heaviest known element and the penultimate element of the 7th period of the periodic table.

The discovery of tennessine was officially anno ...

was named for the state, largely in recognition of the roles played by Oak Ridge,

Vanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University (informally Vandy or VU) is a private research university in Nashville, Tennessee. Founded in 1873, it was named in honor of shipping and rail magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who provided the school its initial $1-million ...

, and the

University of Tennessee

The University of Tennessee (officially The University of Tennessee, Knoxville; or UT Knoxville; UTK; or UT) is a public land-grant research university in Knoxville, Tennessee. Founded in 1794, two years before Tennessee became the 16th sta ...

in the element’s discovery.

Prehistory

Paleo-Indians

Paleo-Indians are believed to have hunted and camped in what is now Tennessee as early as 12,000 years ago. Along with projectile points common for this period, archaeologists in

Williamson County have uncovered a 12,000-year-old

mastodon

A mastodon ( 'breast' + 'tooth') is any proboscidean belonging to the extinct genus ''Mammut'' (family Mammutidae). Mastodons inhabited North and Central America during the late Miocene or late Pliocene up to their extinction at the end of the ...

skeleton with cut marks typical of prehistoric hunters.

The most prominent known

Archaic period (c. 8000 – 1000 BC) site in Tennessee is the

Icehouse Bottom site located just south of

Fort Loudoun in

Monroe County Monroe County may refer to seventeen counties in the United States, all named for James Monroe:

*Monroe County, Alabama

* Monroe County, Arkansas

* Monroe County, Florida

*Monroe County, Georgia

* Monroe County, Illinois

* Monroe County, Indi ...

. Excavations at Icehouse Bottom in the early 1970s uncovered evidence of human habitation dating to as early as 7,500 BC. Other archaic sites include Rose Island, located a few miles downstream from Icehouse Bottom, and the

Eva site in

Benton County. The Archaic peoples first domesticated dogs and created the first villages in the state, but were largely hunter-gatherers confined to smaller territories than their predecessors.

Tennessee is home to two major

Woodland period

In the classification of archaeological cultures of North America, the Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures spanned a period from roughly 1000 BCE to European contact in the eastern part of North America, with some archaeo ...

(1000 BC – 1000 AD) sites: the

Pinson Mounds

The Pinson Mounds comprise a prehistoric Native American complex located in Madison County, Tennessee, in the region that is known as the Eastern Woodlands. The complex, which includes 17 mounds, an earthen geometric enclosure, and numerous habit ...

in

Madison County and the

Old Stone Fort in

Coffee County, both built c. 1–500 AD. The Pinson Mounds are the largest Middle Woodland site in the Southeastern United States, consisting of at least 12 mounds and a geometric earthen enclosure. The Old Stone Fort is a large ceremonial structure with a complex entrance way, situated on what was once a relatively inaccessible peninsula.

Mississippian (c. 1000 – 1600) villages are found along the banks of most of the major rivers in Tennessee. The most well-known of these sites include

Chucalissa near

Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

;

Mound Bottom in

Cheatham County

Cheatham County ( ) is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 census, the population was 41,072. Its county seat is Ashland City. Cheatham County is part of the Nashville-Davidson–Murfreesboro–Franklin, T ...

;

Shiloh Mounds in Hardin County; and the

Toqua site in Monroe County. Excavations at the

McMahan Mound Site

The McMahan Mound Site ( 40SV1), also known as McMahan Indian Mound, is an archaeological site located in Sevierville, Tennessee just above the confluence of the West Fork and the Little Pigeon rivers in Sevier County.

Site description

The site ...

in

Sevier County and more recently at

Townsend Townsend (pronounced tounʹ-zənd) or Townshend may refer to:

Places United States

*Camp Townsend, National Guard training base in Peekskill, New York

*Townsend, Delaware

*Townsend, Georgia

*Townsend, Massachusetts, a New England town

** Townsend ...

in

Blount County have uncovered the remnants of

palisade

A palisade, sometimes called a stakewall or a paling, is typically a fence or defensive wall made from iron or wooden stakes, or tree trunks, and used as a defensive structure or enclosure. Palisades can form a stockade.

Etymology

''Palisade ...

d villages dating to 1200.

European exploration and settlement

Early Spanish and French exploration

In the 16th century, three

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

expeditions passed through what is now Tennessee.

The

Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and ''conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

expedition entered the

Tennessee Valley

The Tennessee Valley is the drainage basin of the Tennessee River and is largely within the U.S. state of Tennessee. It stretches from southwest Kentucky to north Alabama and from northeast Mississippi to the mountains of Virginia and North Car ...

via the

Nolichucky River

The Nolichucky River is a river that flows through Western North Carolina and East Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. Traversing the Pisgah National Forest and the Cherokee National Forest in the Blue Ridge Mountains, the river's wate ...

in June 1540, rested for several weeks at the village of

Chiaha

Chiaha was a Native American chiefdom located in the lower French Broad River valley in modern East Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. They lived in raised structures within boundaries of several stable villages. These overlooked the ...

(near the modern

Douglas Dam

Douglas Dam is a hydroelectric dam on the French Broad River in Sevier County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. The dam is operated by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which built the dam in record time in the early 1940s to mee ...

), and proceeded southward to the

Coosa chiefdom

The Coosa chiefdom was a powerful Native American paramount chiefdom in what are now Gordon and Murray counties in Georgia, in the United States.[Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...]

.

De Soto spent the winter of 1540-41 in camp on Pontotoc Ridge in extreme northern Mississippi. He may have entered Tennessee and went west to the Mississippi at or near present-day Memphis. In 1559, the expedition of

Tristán de Luna, which was resting at Coosa, entered the

Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

area to help the Coosa chief subdue a rebellious tribe known as the Napochies.

In 1567, the

Pardo

''Pardos'' (feminine ''pardas'') is a term used in the former Portuguese and Spanish colonies in the Americas to refer to the triracial descendants of Southern Europeans, Amerindians and West Africans. In some places they were defined as ne ...

expedition entered the Tennessee Valley via the

French Broad River

The French Broad River is a river in the U.S. states of North Carolina and Tennessee. It flows from near the town of Rosman in Transylvania County, North Carolina, into Tennessee, where its confluence with the Holston River at Knoxville form ...

, rested for several days at Chiaha, and followed a trail to the upper

Little Tennessee River

The Little Tennessee River is a tributary of the Tennessee River that flows through the Blue Ridge Mountains from Georgia, into North Carolina, and then into Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. It drains portions of three national ...

before being forced to turn back.

At Chiaha, one of Pardo's subordinates, Hernando Moyano de Morales, established a short-lived fort called San Pedro. It, along with five other Spanish forts across the region, was destroyed by natives in 1569, thereby opening the area to other European colonization.

Chronicles of the Spanish explorers provide the earliest written accounts regarding the Tennessee Valley's 16th-century inhabitants. Most of the valley, including Chiaha, was part of the Coosa chiefdom's regional sphere of influence. Inhabitants spoke a dialect of the

Muskogean

Muskogean (also Muskhogean, Muskogee) is a Native American language family spoken in different areas of the Southeastern United States. Though the debate concerning their interrelationships is ongoing, the Muskogean languages are generally div ...

language, and lived in complex agrarian communities centered around fortified villages.

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

-speaking people lived in the remote reaches of the

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. The ...

, and may have been at war with the Muskogean inhabitants in the valley. The village of Tali, visited by De Soto in 1540, is believed to be the Mississippian-period village excavated at the Toqua site in the 1970s.

The villages of Chalahume and Satapo, visited by Pardo in 1567, were likely predecessors (and namesakes for) the later Cherokee villages of

Chilhowee and

Citico, which were located near the modern

Chilhowee Dam.

As of the 17th century, Tennessee was the middle ground for several different native peoples. Along the Mississippi River was the

Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classif ...

&

Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

peoples, and inland of them were the

Coushatta

The Coushatta ( cku, Koasati, Kowassaati or Kowassa:ti) are a Muskogean-speaking Native American people now living primarily in the U.S. states of Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas.

When first encountered by Europeans, they lived in the terri ...

—all three were part of the

Muskogean

Muskogean (also Muskhogean, Muskogee) is a Native American language family spoken in different areas of the Southeastern United States. Though the debate concerning their interrelationships is ongoing, the Muskogean languages are generally div ...

language family. Before European contact, they were supposedly all a loose collection of Mississippian culture city-states with their own leaders, but upon contact with Europeans, they merged into larger nations, spread out and adopted a European lifestyle, earning many of them the title of the "Civilized Tribes." During the height of the Mississippians, hundreds of walled cities extended throughout the American south from Louisiana to the east coast, up the Mississippi into Wisconsin & a few fringe cities along larger rivers on the Great Plains. They had complex society & agriculture. They did not build with stone, but made plenty of examples of sculpture work in clay, stone & copper. Most of what remains of these cities, however, are large, pyramidal, earthen hills (upon which chiefs & upper-classmen would build their homes) and artful burial mounds. These people did not develop the Mississippian culture, however, but adopted it from the Caddo people west of the Mississippi River.

To the east were the

Yuchi

The Yuchi people, also spelled Euchee and Uchee, are a Native American tribe based in Oklahoma.

In the 16th century, Yuchi people lived in the eastern Tennessee River valley in Tennessee. In the late 17th century, they moved south to Alabama, G ...

& Iroquoian

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

, divided along the Tennessee River. In the north-central region of the state were the Algonquian

Cisca. They later moved northeast and merged with the

Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

, but were briefly replaced with a second native nation known as the Maumee, or

Mascouten which were driven south during the

Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars ( moh, Tsianì kayonkwere), also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars (french: Guerres franco-iroquoises) were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout t ...

(1640-1680) from southern Michigan. They later merged with the Miami of Indiana & were, once again, replaced by the Shawnee. The Shawnee controlled most of the Ohio River Region until the Shawnee Wars (1811-1813).

In 1673, British fur trader

Abraham Wood

Abraham Wood (1610–1682), sometimes referred to as "General" or "Colonel" Wood, was an English fur trader, militia officer, politician and explorer of 17th century colonial Virginia. Wood helped build and maintained Fort Henry at the falls of ...

sent an expedition led by James Needham and Gabriel Arthur from

Fort Henry in the

Colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertGilbert (Saunders Family), Sir Humphrey" (histor ...

into Overhill Cherokee territory in modern-day northeastern Tennessee. Needham was killed during the expedition and Arthur was taken prisoner for more than a year. That same year, a French expedition led by missionary

Jacques Marquette

Jacques Marquette S.J. (June 1, 1637 – May 18, 1675), sometimes known as Père Marquette or James Marquette, was a French Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan's first European settlement, Sault Sainte Marie, and later founded Saint Ign ...

and trader

Louis Jolliet

Louis Jolliet (September 21, 1645after May 1700) was a French-Canadian explorer known for his discoveries in North America. In 1673, Jolliet and Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit Catholic priest and missionary, were the first non-Natives to explore and ...

explored the Mississippi River and became the first Europeans to map the Mississippi Valley.

French explorers and traders, led by

Robert de La Salle

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

, entered the region in 1682 at

Fort Prudhomme

Fort Prudhomme, or Prud'homme, was a simple stockade fortification, constructed in late Feb. 1682 on one of the Chickasaw Bluffs of the Mississippi River in West Tennessee by Cavelier de La Salle's French canoe expedition of the Mississippi Rive ...

. France briefly (1739–1740) established a presence at

Fort Assumption

Fort Assumption (or Fort De L'Assomption) was a French fortification constructed in 1739 on the fourth Chickasaw Bluff on the Mississippi River in Shelby County, present day Memphis, Tennessee. The fort was used as a base against the Chickasaw ...

during the

Chickasaw Wars

The Chickasaw Wars were fought in the 18th century between the Chickasaw allied with the British against the French and their allies the Choctaws and Illinois Confederation. The Province of Louisiana extended from Illinois to New Orleans, and the ...

.

In 1714, a group of French traders under Charles Charleville's command established a settlement at the present location of downtown Nashville near the Cumberland River, which became known as French Lick. These settlers quickly established an extensive fur trading network with the local Native Americans, but by the 1740s the settlement had largely been abandoned. In 1739, the French constructed

Fort Assumption

Fort Assumption (or Fort De L'Assomption) was a French fortification constructed in 1739 on the fourth Chickasaw Bluff on the Mississippi River in Shelby County, present day Memphis, Tennessee. The fort was used as a base against the Chickasaw ...

under

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville (; ; February 23, 1680 – March 7, 1767), also known as Sieur de Bienville, was a French colonial administrator in New France. Born in Montreal, he was an early governor of French Louisiana, appointed four ...

on the Mississippi River at the present-day location of Memphis, which they used as a base against the Chickasaw during the

1739 Campaign of the

Chickasaw Wars

The Chickasaw Wars were fought in the 18th century between the Chickasaw allied with the British against the French and their allies the Choctaws and Illinois Confederation. The Province of Louisiana extended from Illinois to New Orleans, and the ...

. It was abandoned the next year after the Chickasaw took hostage French troops stationed at the fort.

The

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

eventually moved south from the area now called

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

. As European colonists spread into the area, the native populations were forcibly displaced to the south and west, including the

Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands[Yuchi

The Yuchi people, also spelled Euchee and Uchee, are a Native American tribe based in Oklahoma.

In the 16th century, Yuchi people lived in the eastern Tennessee River valley in Tennessee. In the late 17th century, they moved south to Alabama, G ...]

,

Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classif ...

and

Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

peoples. Then, from 1838 to 1839, the US government forced the Cherokee to leave the eastern United States. Nearly 17,000 Cherokee were forced to march from eastern Tennessee to the

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

west of the

Arkansas Territory

The Arkansas Territory was a territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1819, to June 15, 1836, when the final extent of Arkansas Territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Arkansas. Arkansas Post was the first territo ...

. This came to be known as the

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

, as an estimated 4,000 Cherokee died along the way. In the

Cherokee language

200px, Number of speakers

Cherokee or Tsalagi ( chr, ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ, ) is an endangered-to- moribund Iroquoian language and the native language of the Cherokee people. ''Ethnologue'' states that there were 1,520 Cherokee speak ...

, the event is called ''Nunna daul Isunyi''—"The Trail Where We Cried".

Early British exploration and settlement

In the 1750s and 1760s,

longhunter

A longhunter (or long hunter) was an 18th-century explorer and hunter who made expeditions into the American frontier for as much as six months at a time. Historian Emory Hamilton says that "The Long Hunter was peculiar to Southwest Virginia onl ...

s from Virginia explored much of East and Middle Tennessee. In 1756, British soldiers from the

Colony of South Carolina

Province of South Carolina, originally known as Clarendon Province, was a province of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776. It was one of the five Southern colonies and one of the thirteen American colonies. The monar ...

built

Fort Loudoun near present-day

Vonore, the first British settlement in what is now Tennessee. Fort Loudoun was the westernmost British outpost to that date, and was designed by

John William Gerard de Brahm and constructed by forces under Captain Raymond Demeré. Shortly after its completion, Demeré relinquished command of the fort to his brother, Captain Paul Demeré. Hostilities erupted between the British and the Overhill Cherokees into an armed conflict that became known as the

Anglo-Cherokee War

The Anglo-Cherokee War (1758–1761; in the Cherokee language: the ''"war with those in the red coats"'' or ''"War with the English"''), was also known from the Anglo-European perspective as the Cherokee War, the Cherokee Uprising, or the Cherok ...

, and a

siege of the fort ended with its surrender in 1760. The next morning, Paul Demeré and a number of his troops were killed in an ambush nearby, and most of the rest of the garrison was taken prisoner. After the end of the

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

, Britain issued the

Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

, which forbade settlements west of the

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. The ...

in an effort to mitigate conflicts with the Natives. Despite this proclamation, migration across the mountains continued, and the first permanent European settlers began arriving in the northeastern part of the state in the late 1760s.

William Bean

William Bean (December 9, 1721-May 1782) was an American pioneer, longhunter, and Commissioner of the Watauga Association. He is accepted by historians as the first permanent European American settler of Tennessee.

Biography

William Bean was b ...

, a longhunter who settled in a log cabin near present-day

Johnson City in 1769, is traditionally accepted as the first permanent European American settler in Tennessee.

Most 18th-century settlers were English or of primarily

English descent, but nearly 20% of them were

Scotch-Irish.

Watauga Association

During 1772, the Watauga Association met with, and leased lands belonging to, the

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

at

Sycamore Shoals

The Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River, usually shortened to Sycamore Shoals, is a rocky stretch of river rapids along the Watauga River in Elizabethton, Tennessee. Archeological excavations have found Native Americans lived near the shoals s ...

(in the present day area of

Elizabethton, Tennessee

Elizabethton is a city in, and the county seat of Carter County, Tennessee, United States. Elizabethton is the historical site of the first independent American government (known as the Watauga Association, created in 1772) located west of both t ...

). In 1775, Sycamore Shoals was the site of the Transylvania purchase, conducted between the Cherokee and North Carolina land baron, Richard Henderson.

The Treaty of Sycamore Shoals, more popularly referred to as the Transylvania Purchase (after Henderson's Transylvania Company, which had raised money for the endeavor), consisted of two parts. The first, known as the "

Path Grant Deed", regarded the Transylvania Company's purchase of lands in southwest Virginia (including parts of what is now

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the ...

) and northeastern Tennessee. The second part, known as the "Great Grant," acknowledged the Transylvania Company's purchase of some of land between the

Kentucky River

The Kentucky River is a tributary of the Ohio River, long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 13, 2011 in the U.S. Commonwealth of Kentucky. The river and its t ...

and

Cumberland River

The Cumberland River is a major waterway of the Southern United States. The U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 8, 2011 river drains almost of southern Kentucky and ...

, which included a large portion of modern Kentucky and a significant portion of Tennessee north of present day Nashville. The Transylvania Company paid for the land with 10,000

pounds sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and ...

of trade goods. After the treaty was signed, frontier explorer

Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the we ...

came northward to blaze the

Wilderness Road

The Wilderness Road was one of two principal routes used by colonial and early national era settlers to reach Kentucky from the East. Although this road goes through the Cumberland Gap into southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee, the other (m ...

, connecting the Transylvania Purchase lands with the Holston and Watauga settlements.

Both the lease and the sale were considered illegal by the Crown Government, as well as by the warring Cherokee faction known as the

Chickamauga Chickamauga may refer to:

Entertainment

* "Chickamauga", an 1889 short story by American author Ambrose Bierce

* "Chickamauga", a 1937 short story by Thomas Wolfe

* "Chickamauga", a song by Uncle Tupelo from their 1993 album ''Anodyne (album), Ano ...

, led by the war-chief,

Dragging Canoe

Dragging Canoe (ᏥᏳ ᎦᏅᏏᏂ, pronounced ''Tsiyu Gansini'', "he is dragging his canoe") (c. 1738 – February 29, 1792) was a Cherokee war chief who led a band of Cherokee warriors who resisted colonists and United States settlers in the ...

. The Chickamauga violently contested the westward expansion by European settlers across Tennessee throughout the

Cherokee–American wars (1776–1794).

In April 1775, the Watauga Association was reorganized as the "

Washington District

The Washington District is a Norfolk Southern Railway line in the U.S. state of Virginia that connects Alexandria, Virginia, Alexandria and Lynchburg, Virginia, Lynchburg. Most of the line was originally built from 1850 to 1860 by the Orange and ...

," allied with the colonies that were declaring independence from Great Britain. The Washington District annexation petition was first rejected by Virginia in the spring of 1776, but a similar annexation petition presented by the district to the North Carolina legislature was approved in November 1776.

Government under North Carolina

In the days before statehood, Tennesseans struggled to gain a political voice and suffered for lack of the protection afforded by organized government. Six counties—

Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

,

Sullivan, and

Greene

Greene may refer to:

Places United States

*Greene, Indiana, an unincorporated community

*Greene, Iowa, a city

*Greene, Maine, a town

** Greene (CDP), Maine, in the town of Greene

*Greene (town), New York

** Greene (village), New York, in the town ...

in

East Tennessee

East Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee defined in state law. Geographically and socioculturally distinct, it comprises approximately the eastern third of the U.S. state of Tennessee. East Tennessee consists of 33 count ...

; and

Davidson

Davidson may refer to:

* Davidson (name)

* Clan Davidson, a Highland Scottish clan

* Davidson Media Group

* Davidson Seamount, undersea mountain southwest of Monterey, California, USA

* Tyler Davidson Fountain, monument in Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

* ...

,

Sumner, and

Tennessee County

Tennessee County, North Carolina was a subdivision of the North Carolina's Washington District in the '' Overmountain Region''—which later became the state of Tennessee.

History

Tennessee County was organized in 1788 from a portion of Davids ...

in

Middle Tennessee

Middle Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that composes roughly the central portion of the state. It is delineated according to state law as 41 of the state's 95 counties. Middle Tennessee contains the ...

—had been formed as western counties of

North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

between 1777 and 1788.

In 1780, the newly formed

Cumberland Association, under the

Cumberland Compact {{Short description, 1780 document establishing the law of settlers in present-day Tennessee

The Cumberland Compact was both based on the earlier Articles of the Watauga Association composed at present day Elizabethton, Tennessee and is a foundat ...

, established

Fort Nashborough

Fort Nashborough, also known as Fort Bluff, Bluff Station, French Lick Fort, Cumberland River Fort and other names, was the stockade established in early 1779 in the French Lick area of the Cumberland River valley, as a forerunner to the settl ...

on the

Cumberland River

The Cumberland River is a major waterway of the Southern United States. The U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 8, 2011 river drains almost of southern Kentucky and ...

, opening up a second frontier of settlement within present-day Tennessee. The Cumberland River settlements were separated from those in the east by a substantial enclave of

Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

territory that was not formally acquired from them until 1805.

After the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, North Carolina did not want the trouble and expense of maintaining such distant settlements, embroiled as they were with hostile tribesmen during the Cherokee–American wars, and needing roads, forts, and open waterways. Nor could the far-flung settlers look to the national government; for under the weak, loosely constituted

Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

, it was a government in name only.

In 1775,

Richard Henderson negotiated a series of treaties with the Cherokee to sell the lands of the Watauga settlements at

Sycamore Shoals

The Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River, usually shortened to Sycamore Shoals, is a rocky stretch of river rapids along the Watauga River in Elizabethton, Tennessee. Archeological excavations have found Native Americans lived near the shoals s ...

on the banks of the

Watauga River

The Watauga River () is a large stream of western North Carolina and East Tennessee. It is long with its headwaters in Linville Gap to the South Fork Holston River at Boone Lake.

Course

The Watauga River rises from a spring near the base ...

in present-day

Elizabethton

Elizabethton is a city in, and the county seat of Carter County, Tennessee, United States. Elizabethton is the historical site of the first independent American government (known as the Watauga Association, created in 1772) located west of both t ...

. An agreement to sell land for the

Transylvania Colony

The Transylvania Colony, also referred to as the Transylvania Purchase, was a short-lived, extra-legal colony founded in early 1775 by North Carolina land speculator Richard Henderson, who formed and controlled the Transylvania Company. Henders ...

, which included the territory in modern-day Tennessee north of the

Cumberland River

The Cumberland River is a major waterway of the Southern United States. The U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 8, 2011 river drains almost of southern Kentucky and ...

, was also signed. Later that year,

Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the we ...

, under Henderson's employment, blazed a trail from

Fort Chiswell

Chiswell , sometimes , is a small village at the southern end of Chesil Beach, in Underhill, on the Isle of Portland in Dorset. It is the oldest settlement on the island, having formerly been known as Chesilton. The small bay at Chiswell is ca ...

in Virginia through the

Cumberland Gap

The Cumberland Gap is a pass through the long ridge of the Cumberland Mountains, within the Appalachian Mountains, near the junction of the U.S. states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. It is famous in American colonial history for its r ...

, which became part of the

Wilderness Road

The Wilderness Road was one of two principal routes used by colonial and early national era settlers to reach Kentucky from the East. Although this road goes through the Cumberland Gap into southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee, the other (m ...

, a major thoroughfare for settlers into Tennessee and Kentucky.

The first reported permanent settlement in Tennessee,

Bean Station, was established in 1776, but was explored by pioneers

Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the we ...

and

William Bean

William Bean (December 9, 1721-May 1782) was an American pioneer, longhunter, and Commissioner of the Watauga Association. He is accepted by historians as the first permanent European American settler of Tennessee.

Biography

William Bean was b ...

one year prior on a

longhunting excursion.

The duo first observed Bean Station after crossing the gap at

Clinch Mountain

Clinch Mountain is a mountain ridge in the U.S. states of Tennessee and Virginia, lying in the ridge-and-valley section of the Appalachian Mountains. From its southern terminus at Kitts Point, which lies at the intersection of Knox, Union and Gr ...

along a southern expansion of the

Wilderness Road

The Wilderness Road was one of two principal routes used by colonial and early national era settlers to reach Kentucky from the East. Although this road goes through the Cumberland Gap into southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee, the other (m ...

from the

Cumberland Gap

The Cumberland Gap is a pass through the long ridge of the Cumberland Mountains, within the Appalachian Mountains, near the junction of the U.S. states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. It is famous in American colonial history for its r ...

, one of the main thoroughfares into Tennessee.

After fighting in the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

one year later, Bean was awarded in the area he previously surveyed for settlement during his excursion with Boone.

Bean would later construct a four-room cabin at this site, which served as his family's permanent home, and as an inn for prospective settlers,

fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal ecosystem, boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals h ...

rs, and longhunters, thus establishing the first reported permanent settlement in Tennessee.

The settlement was situated at the intersection of the

Wilderness Road

The Wilderness Road was one of two principal routes used by colonial and early national era settlers to reach Kentucky from the East. Although this road goes through the Cumberland Gap into southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee, the other (m ...

, that roughly followed what is present-day

U.S. Route 25E, and the

Great Indian Warpath

The Great Indian Warpath (GIW)—also known as the Great Indian War and Trading Path, or the Seneca Trail—was that part of the network of trails in eastern North America developed and used by Native Americans which ran through the Great Appala ...

, an east–west pathway that roughly followed what is now

U.S. Route 11W

U.S. Route 11W (US 11W), locally known as Bloody 11W, is a divided highway of US 11 in the U.S. states of Tennessee and Virginia. The U.S. Highway, which is complemented by US 11E to the south and east, runs from US 11, US 11E, and US 70 in ...

.

This heavily trafficked

crossroads location made Bean Station an important stopover between

Washington, D.C. and

for early American travelers entering Tennessee, with taverns and inns operating by the 1800s.

State of Franklin

The westerners' two main demands—protection from the Indians and the right to navigate the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

—went mainly unheeded during the 1780s. North Carolina's insensitivity led frustrated

East Tennesseans in 1784 to form the breakaway

State of Franklin

The State of Franklin (also the Free Republic of Franklin or the State of Frankland)Landrum, refers to the proposed state as "the proposed republic of Franklin; while Wheeler has it as ''Frankland''." In ''That's Not in My American History Boo ...

.

John Sevier

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 September 24, 1815) was an American soldier, frontiersman, and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he played a leading role in Tennes ...

was named governor, and the fledgling state began operating as an independent, though unrecognized, government. At the same time, leaders of the

Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic counties of England, historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th c ...

settlements made overtures for an alliance with Spain, which controlled the lower Mississippi River and was held responsible for inciting the Indian raids. In drawing up the Watauga and Cumberland Compacts, early Tennesseans had already exercised some of the rights of self-government and were showing signs of a willingness to take political matters into their own hands.

Such stirrings of independence caught the attention of North Carolina, which began to reassert control over its western counties. These policies and internal divisions among East Tennesseans doomed the short-lived State of Franklin, which passed out of existence by early 1789.

Southwest Territory

When North Carolina ratified the

Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the nati ...

in 1789, it also ceded its western lands, the "Tennessee country", to the Federal government. North Carolina had used these lands as a means of rewarding its Revolutionary War soldiers. In the

Cession Act of 1789, it reserved the right to satisfy further land claims in Tennessee.

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

designated the area as the "Territory of the United States South of the River Ohio", more commonly known as the

Southwest Territory

The Territory South of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Southwest Territory, was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 26, 1790, until June 1, 1796, when it was admitted to the United States a ...

. The territory was divided into three districts—two for

East Tennessee

East Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee defined in state law. Geographically and socioculturally distinct, it comprises approximately the eastern third of the U.S. state of Tennessee. East Tennessee consists of 33 count ...

and one for the Mero District on the Cumberland—each with its own courts, militia and officeholders. President

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

appointed

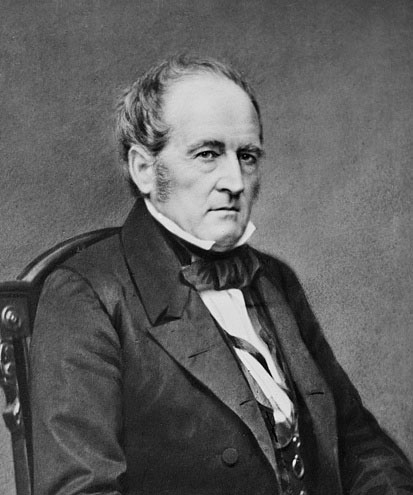

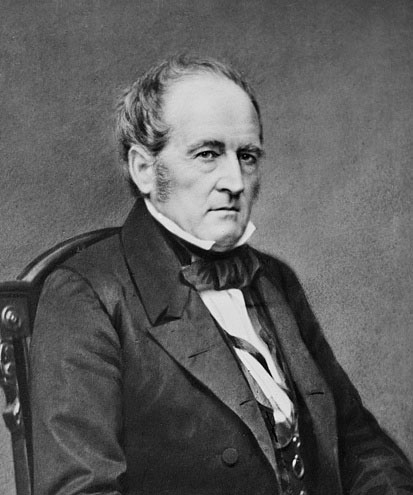

William Blount

William Blount (March 26, 1749March 21, 1800) was an American Founding Father, statesman, farmer and land speculator who signed the United States Constitution. He was a member of the North Carolina delegation at the Constitutional Convention o ...

, a prominent North Carolinian politician with extensive holdings in the western lands, territorial governor.

Admission to the Union

In 1795, a territorial census revealed a sufficient population for statehood. A referendum showed a three-to-one majority in favor of joining the Union. Governor Blount called for a

constitutional convention to meet in

Knoxville

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the state' ...

, where delegates from all the counties drew up a model state

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

and democratic

bill of rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pr ...

.

The voters chose Sevier as governor. The newly elected legislature voted for Blount and

William Cocke as

Senators, and

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

as

Congressman

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivalen ...

.

Tennessee leaders thereby converted the territory into a new state, with organized government and constitution, before applying to Congress for admission. Since the Southwest Territory was the first Federal territory to present itself for admission to the Union, there was some uncertainty about how to proceed, and Congress was divided on the issue.

Nonetheless, in a close vote on June 1, 1796, Congress approved the admission of Tennessee as the sixteenth state of the Union. They drew its borders by extending the northern and southern borders of North Carolina, with a few deviations, to the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

, Tennessee's western boundary.

Jacksonian America (1815–1841)

In the early years of settlement, planters brought African slaves with them from Kentucky and Virginia. These slaves were first concentrated in Middle Tennessee, where planters developed mixed crops and bred high-quality horses and cattle, as they did in the Inner Bluegrass region of Kentucky. East Tennessee had more subsistence farmers and few slaveholders.

During the early years of state formation, there was support for emancipation. At the constitutional convention of 1796, "free negroes" were given the right to vote if they met residency and property requirements. Efforts to abolish slavery were defeated at this convention and again at the convention of 1834. The convention of 1834 also marked the state's retraction of suffrage for most freed slaves.

By 1830 the number of African Americans had increased from less than 4,000 at the beginning of the century to 146,158. This was chiefly related to the invention of the

cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); a ...

in 1793 and the development of large plantations and transportation of numerous enslaved people to the Cotton Belt in

West Tennessee

West Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that roughly comprises the western quarter of the state. The region includes 21 counties between the Tennessee and Mississippi rivers, delineated by state law. Its ...

, in the area of the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

.

Antebellum years (1841–1861)

By 1860 the slave population had nearly doubled to 283,019, with only 7,300 free African Americans in the state. While much of the slave population was concentrated in West Tennessee, planters in Middle Tennessee also used enslaved African Americans for labor. According to the 1860 census, African slaves comprised about 25% of the state's population of 1.1 million before the Civil War.

Civil War

Secession

Most Tennesseans initially showed little enthusiasm for breaking away from a nation whose struggles it had shared for so long. There were small exceptions such as

Franklin County, which borders Alabama in southern Middle Tennessee; Franklin County formally threatened to secede from Tennessee and join Alabama if Tennessee did not leave the Union. Franklin County withdrew this threat when Tennessee did eventually secede. In 1860, Tennesseans had voted by a slim margin for the

Constitutional Unionist John Bell, a native son and moderate who continued to search for a way out of the crisis.

In February 1861, fifty-four percent of the state's voters voted against sending delegates to a secession convention. With the attack on

Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battle ...

in April, however, followed by President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

's call for 75,000 volunteers to coerce the seceded states back into line, public sentiment turned dramatically against the Union.

Historian Daniel Crofts wrote: "Unionists of all descriptions, both those who became Confederates and those who did not, considered the proclamation calling for seventy-five thousand troops 'disastrous.' Having consulted personally with Lincoln in March, Congressman Horace Maynard, the unconditional Unionist and future Republican from East Tennessee, felt assured that the administration would pursue a peaceful policy. Soon after April 15, a dismayed Maynard reported that 'the President's extraordinary proclamation' had unleashed 'a tornado of excitement that seems likely to sweep us all away.' Men who had 'heretofore been cool, firm and Union loving' had become 'perfectly wild' and were 'aroused to a phrenzy

icof passion.' For what purpose, they asked, could such an army be wanted 'but to invade, overrun and subjugate the Southern states.' The growing war spirit in the North further convinced southerners that they would have to 'fight for our hearthstones and the security of home.'

Governor

Isham Harris began military mobilization, submitted an

ordinance

Ordinance may refer to:

Law

* Ordinance (Belgium), a law adopted by the Brussels Parliament or the Common Community Commission

* Ordinance (India), a temporary law promulgated by the President of India on recommendation of the Union Cabinet

* ...

of

secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

to the

General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of pres ...

, and made direct overtures to the

Confederate government. In a June 8, 1861, referendum, East Tennessee held firm against separation, while

West Tennessee

West Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that roughly comprises the western quarter of the state. The region includes 21 counties between the Tennessee and Mississippi rivers, delineated by state law. Its ...

returned an equally heavy majority in favor. The deciding vote came in

Middle Tennessee

Middle Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that composes roughly the central portion of the state. It is delineated according to state law as 41 of the state's 95 counties. Middle Tennessee contains the ...

, which went from 51 percent against secession in February to 88 percent in favor in June.

Having ratified by popular vote its connection with the fledgling

Confederacy, Tennessee became the last state to officially withdraw from the Union.

Unionism

People in

East Tennessee

East Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee defined in state law. Geographically and socioculturally distinct, it comprises approximately the eastern third of the U.S. state of Tennessee. East Tennessee consists of 33 count ...

were firmly against Tennessee's move to leave the Union; as were many in other parts of the Union, particularly in historically Whig portions of West Tennessee. This was primarily due to the distribution of slavery throughout the state; Of the state's entire slave population, nearly 40% of West Tennessee and about 20% of Middle Tennessee's were slaves, but in East Tennessee, slaves made up only 8% of the population. The

East Tennessee Convention

The East Tennessee Convention was an assembly of Southern Unionist delegates primarily from East Tennessee that met on three occasions during the Civil War. The Convention most notably declared the secessionist actions taken by the Tennessee st ...

, which met at Knoxville in May 1861 and at Greeneville in June 1861, consisted of 29 East Tennessee counties and one Middle Tennessee county (

Scott County) that resolved to secede from Tennessee and form a separate state aligned with the Union. They petitioned the state legislature in Nashville, which denied their request to secede and sent Confederate troops under

Felix Zollicoffer

Felix Kirk Zollicoffer (May 19, 1812 – January 19, 1862) was an American newspaperman, slave owner, politician, and soldier. A three-term United States Congressman from Tennessee, an officer in the United States Army, and a Confederate briga ...

to occupy East Tennessee and prevent secession. Many East Tennesseans engaged in

guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run ta ...

against state authorities by

burning bridges, cutting telegraph wires, and spying. The Union-backing

State of Scott was also established at this time and remained a ''

de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with '' de jure'' ("by l ...

'' enclave of the United States throughout the war.

Tennessee provided more Union troops than any other Confederate state; more than 51,000 soldiers in total, more than 20,000 of whom were

Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ha ...

. Tennessee also provided 135,000 Confederate troops, the second-highest number after Virginia.

Battles

Many battles were fought in the state – most of them Union victories.

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

and the

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

captured control of the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers in February 1862 and held off the

Confederate counterattack at

Shiloh in April of the same year. Capture of

Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

and

Nashville

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and th ...

gave the Union control of the Western and Middle

sections

Section, Sectioning or Sectioned may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Section (music), a complete, but not independent, musical idea

* Section (typography), a subdivision, especially of a chapter, in books and documents

** Section sig ...

. Control was confirmed at the

Battle of Stones River

The Battle of Stones River, also known as the Second Battle of Murfreesboro, was a battle fought from December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863, in Middle Tennessee, as the culmination of the Stones River Campaign in the Western Theater of the Am ...

at

Murfreesboro

Murfreesboro is a city in and county seat of Rutherford County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 152,769 according to the 2020 census, up from 108,755 residents certified in 2010. Murfreesboro is located in the Nashville metropol ...

in early January 1863.

After Nashville was captured (the first Confederate state capital to fall),

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

, an East Tennessean from

Greeneville, was appointed military governor of the state by Lincoln. The military government abolished

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in the state and Union troops occupied much of the state through the end of the war.

The Confederates continued to hold East Tennessee despite the strength of Unionist sentiment there, with the exception of pro-Confederate

Sullivan County. The Confederates besieged

Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

in early fall 1863 but were driven off by Grant in November. Many of the Confederate defeats can be attributed to the poor strategic vision of General

Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, serving in the Wester ...

, who led the

Army of Tennessee

The Army of Tennessee was the principal Confederate army operating between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River during the American Civil War. It was formed in late 1862 and fought until the end of the war in 1865, participating in ...

from

Shiloh to Confederate defeat at Chattanooga.

The last major battles came when the Confederates invaded in November 1864 and were checked at

Franklin, then totally destroyed by

George Thomas at Nashville in December.

Reconstruction era and Disenfranchisement

After the war, Tennessee adopted the Thirteenth amendment forbidding slave-holding or involuntary servitude on February 22, 1865; ratified the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment (Amendment XIV) to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Often considered as one of the most consequential amendments, it addresses citizenship rights and ...

on July 18, 1866; and was the first state readmitted to the Union on July 24, 1866.

Because it had ratified the

Fourteenth Amendment, Tennessee was the only state that seceded from the Union that did not have a military governor during

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

. "Proscription" was the policy of disqualifying as many ex-Confederates as possible. In 1865 Tennessee disfranchised upwards of 80,000 ex-Confederates.

There were only two or three African Americans in the Tennessee legislature during Reconstruction, though others served as state and city officers. With increased participation on the Nashville City Council, African Americans then held one-third of the seats.

[W.E.B. DuBois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880, New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1935; reprint The Free Press, 1998, p. 575] In his race for Congress in 1872, Andrew Johnson addressed African Americans in speaking campaigns in western counties, saying, "If fit and qualified by character and education, no one should deny you the ballot."

In 1870,

Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally much more conservative than Northern Democrats wi ...

regained control of the state legislature, and quickly reversed many of the reforms of the Brownlow administration. In 1889, the Tennessee General Assembly passed four acts of self-described electoral reform that resulted in the disenfranchisement of a significant portion of African American voters as well as many poor white voters. The timing of the legislation resulted from a unique opportunity seized by the Democratic Party to bring an end to what one historian described as the most "consistently competitive political system in the South." These laws instituted a

poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

, required early voter registration, allowed

secret ballot

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vo ...

s, and required separate ballot boxes for state and federal elections.

In the political campaign of 1888, the Democrats waged a political battle to gain quorum control over both houses of the legislature. With Republicans unable to stall or defeat antiparty measures, the disenfranchising acts sailed through the 1889 general assembly, and Governor Robert L. Taylor signed them into law. Hailed by newspaper editors as the end of black voting, the laws worked as expected, and African American voting declined precipitously in rural and small town Tennessee. Many urban blacks continued to vote until so-called progressive reforms eliminated their political power in the early twentieth century.

[Disfranchising Laws, The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture](_blank)

Accessed March 11, 2008

Disenfranchising provisions worked against poor whites as well for decades. Tennessee, with the Democratic Party in power in the Middle and Western sections; the Eastern section retained Republican support based on its Unionist leanings before and during the war.

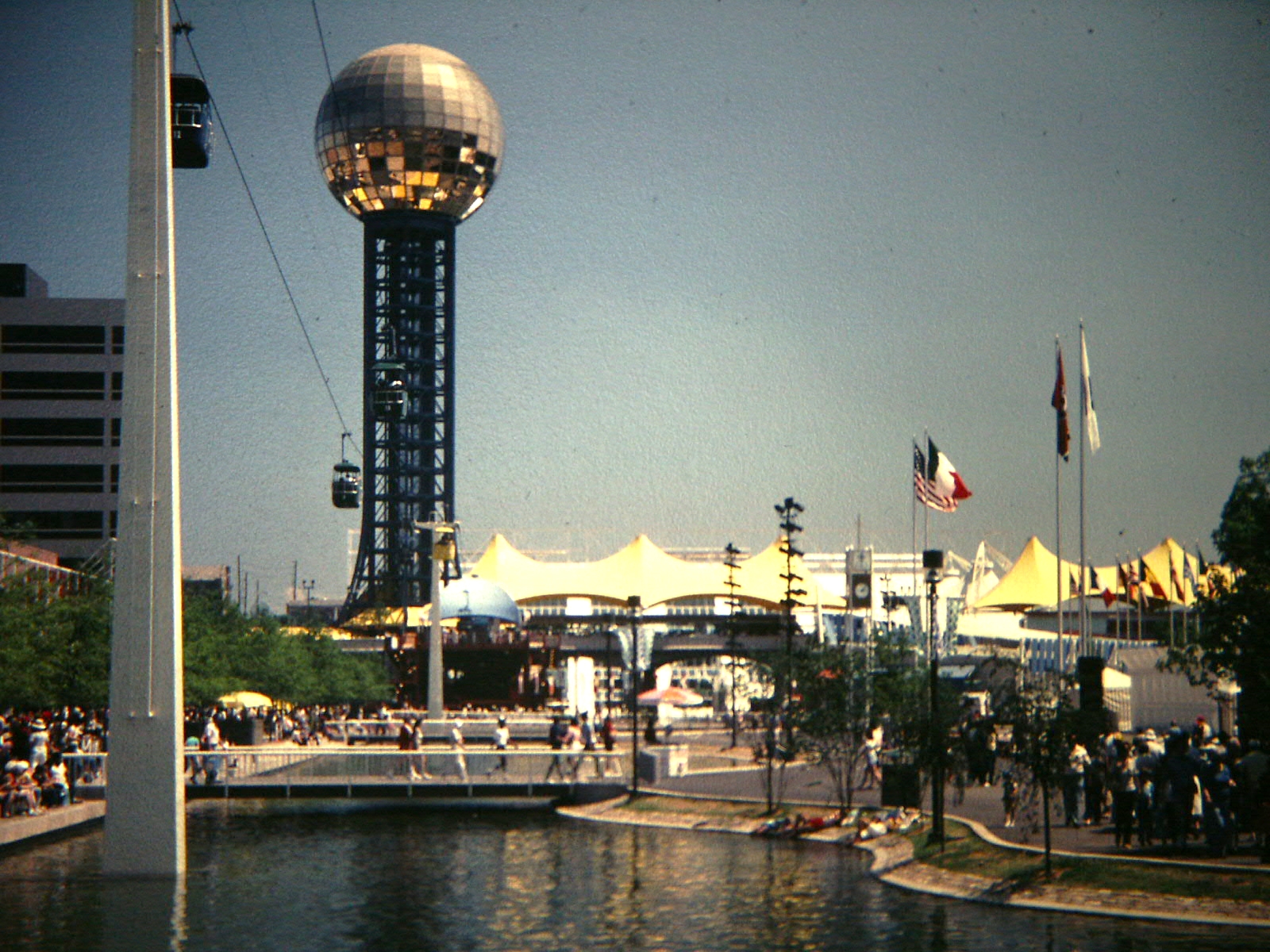

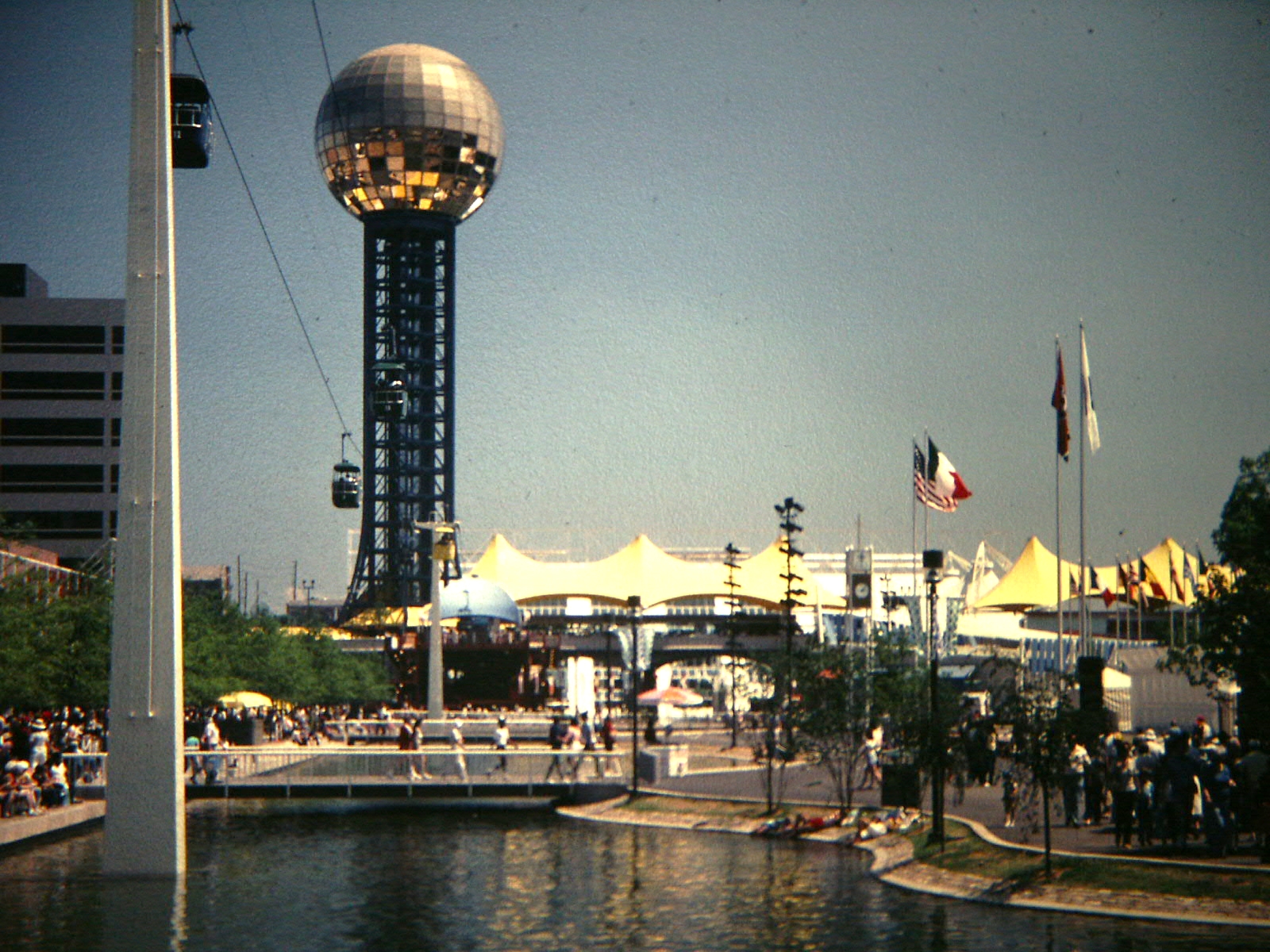

Tennessee Centennial

In 1897, the state celebrated its

centennial

{{other uses, Centennial (disambiguation), Centenary (disambiguation)

A centennial, or centenary in British English, is a 100th anniversary or otherwise relates to a century, a period of 100 years.

Notable events

Notable centennial events at a ...

of statehood (albeit one year late) with a great

exposition

Exposition (also the French for exhibition) may refer to:

*Universal exposition or World's Fair

* Expository writing

** Exposition (narrative)

* Exposition (music)

*Trade fair

A trade fair, also known as trade show, trade exhibition, or trade e ...

in Nashville. The Tennessee Centennial Exposition was the ultimate expression of the

Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Wes ...

in the Upper South—a showcase of industrial technology and exotic papier-mâché versions of the world's wonders. The Nashville

Parthenon

The Parthenon (; grc, Παρθενών, , ; ell, Παρθενώνας, , ) is a former temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, that was dedicated to the goddess Athena during the fifth century BC. Its decorative sculptures are considere ...

, a full-scale replica of Athens'

Parthenon

The Parthenon (; grc, Παρθενών, , ; ell, Παρθενώνας, , ) is a former temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, that was dedicated to the goddess Athena during the fifth century BC. Its decorative sculptures are considere ...

, was built in plaster, wood and brick. Rebuilt of concrete in the 1920s, it remains one of the city's attractions. During its six-month run at

Centennial Park, the Exposition drew nearly two million visitors to see its dazzling monuments to the South's recovery. Governor

Robert Taylor observed, "Some of them who saw our ruined country thirty years ago will certainly appreciate the fact that we have wrought miracles."

Early 20th century

During the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

(1914–1918), Tennessee provided the most celebrated American soldier,

Alvin C. York

Alvin Cullum York (December 13, 1887 – September 2, 1964), also known as Sergeant York, was one of the most decorated United States Army soldiers of World War I. He received the Medal of Honor for leading an attack on a German machin ...

, of

Fentress County, Tennessee

Fentress County is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 census, the population was 18,489. Its county seat is Jamestown.

History

Fentress County was formed on November 28, 1823, from portions of Morgan, Overton a ...

. He was a former

conscientious objector