History Of Slavery In New Hampshire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Various Algonquian-speaking

Various Algonquian-speaking  The relationship between Massachusetts and the independent New Hampshirites was controversial and tenuous, and complicated by land claims maintained by the heirs of John Mason. In 1679 King Charles II separated New Hampshire from Massachusetts, issuing a charter for the royal

The relationship between Massachusetts and the independent New Hampshirites was controversial and tenuous, and complicated by land claims maintained by the heirs of John Mason. In 1679 King Charles II separated New Hampshire from Massachusetts, issuing a charter for the royal

New Hampshire was one of the

New Hampshire was one of the

In 1832, New Hampshire saw a curious development: the founding of the

In 1832, New Hampshire saw a curious development: the founding of the

Between 1884 and 1903, New Hampshire attracted many immigrants.

Between 1884 and 1903, New Hampshire attracted many immigrants.

Online books: New Hampshire

''New Hampshire: a Guide to the Granite State'': "Chronology"

Boston: Houghton Mifflin

online

for online copies see Annual Cyclopaedia. Each year includes several pages on each U.S. state. * Anderson, Leon W. ''To this day: the 300 years of the New Hampshire Legislature'' (Phoenix Pub., 1981). * Belknap, Jeremy. ''The History of New Hampshire'' (1791–1792) 3 vol classi

Volume 1

or th

1862 edition with corrections.

at books. Google. * Cole, Donald B. ''Jacksonian Democracy in New Hampshire'' (Harvard UP, 1970

online

* Daniell, Jere. ''Experiment in Republicanism: New Hampshire politics and the American Revolution, 1741-1794'' (197

online

* Daniell, Jere. ''Colonial New Hampshire: A History'' (1982), scholarly history

online

* Dwight, Timothy. ''Travels Through New England and New York'' (circa 1800) 4 vol. (1969

online

* French, Laurence Armand. ''Frog Town: Portrait of a French Canadian Parish in New England'' (University Press of America, 2014

online

* Guyol, Philip Nelson. ''Democracy Fights: A History of New Hampshire in World War II'' (Dartmouth, 1951). * Hareven, Tamara K., and Randolph Langenbach. ''Amoskeag: Life and work in an American factory-city'' (UPNE, 1995) The Amoskeag textile factory in Manchester was the largest in the world; this is the story of its workers

online

* Heffernan, Nancy Coffey, and Ann Page Stecker. ''New Hampshire: crosscurrents in its development'' (1986) short popular history

online

* Jager, Ronald and Grace Jager. ''The Granite State New Hampshire: An Illustrated History'' (2000) popular. * Kilbourne, Frederick Wilkinson. ''Chronicles of the White Mountains'' (1916

online

* Kinney, Charles B. ''Church & state: the struggle for separation in New Hampshire 1630-1900'' (1955). * Lafferty, Ben Paul. ''American Intelligence: Small-Town News and Political Culture in Federalist New Hampshire'' (U of Massachusetts Press, 2020

online

* Lafferty, Ben Paul. "Joseph Dennie and The Farmer's Weekly Museum: Readership and Pseudonymous Celebrity in Early National Journalism," ''American Nineteenth Century History'', 15:1, 67-87, DOI: 10.1080/14664658.2014.892302 *McClintock, John N

''Colony, Province, State, 1623-1888: History of New Hampshire''

Published 1889. * Morison, Elizabeth Forbes and

online

* Palfrey, John Gorham

''History of New England'' (5 vol 1859–90)

* Renda, Lex. ''Running on the Record: Civil War-Era Politics in New Hampshire'' (University of Virginia Press, 1997

online

** Renda, Lex. "Credit and Culpability: New Hampshire State Politics During the Civil War," ''Historical New Hampshire'' 48 (Spring, 1993), 3-84. reprinted in his book. * Sanborn, Edwin David

''History of New Hampshire, from Its First Discovery to the Year 1830''

(1875, 422 pages) * Sewell, Richard H. ''John P. Hale and the politics of abolition'' (1965

online

* Smith, Norman W. ''A mature frontier: the New Hampshire economy 1790-1850'' ''Historical New Hampshire'' 24#1 (1969) 3-19. * Squires, J. Duane. ''The Granite State of the United States: A History of New Hampshire from 1623 to the Present'' (1956) vol 1 * Stackpole, Everett S. ''History of New Hampshire'' (4 vol 1916-1922

vol 4 online covers Civil War and late 19th century

* Thompson, Woodrow. "History of research on glaciation in the White Mountains, New Hampshire (USA)." ''Géographie physique et Quaternaire'' 53.1 (1999): 7-24

online

* Turner, Lynn Warren. ''The Ninth State: New Hampshire's Formative Years'' (1983

* Upton, Richard Francis. ''Revolutionary New Hampshire: An Account of the Social and Political Forces Underlying the Transition from Royal Province to American Commonwealth'' (1936) * Whiton, John Milton

''Sketches of the History of New-Hampshire, from Its Settlement in 1623, to 1833''.

Published 1834, 222 pages. * Wilson, H. F. ''The Hill Country of Northern New England: Its Social and Economic History, 1790–1930'' (1936) * {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of New Hampshire History of New Hampshire,

New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

is a state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

in the New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

region of the northeastern United States

The Northeastern United States, also referred to as the Northeast, the East Coast, or the American Northeast, is a geographic region of the United States. It is located on the Atlantic coast of North America, with Canada to its north, the Southe ...

and was one of the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

that revolted against British rule in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

. One of the smallest states in area and population, it was part of New England's textile economy between the Civil War and World War II, and in recent decades is known for its presidential primary

The presidential primary elections and caucuses held in the various U.S. state, states, the Washington, D.C., District of Columbia, and territories of the United States form part of the nominating process of candidates for United States preside ...

, outdoor recreation, and being part of the biotech industry and elite educational schools centered around Boston, Massachusetts.

Founding: 17th century–1775

Various Algonquian-speaking

Various Algonquian-speaking Abenaki

The Abenaki (Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was predom ...

tribes, largely divided between the Androscoggin and Pennacook nations, inhabited the area before European settlement. Despite the similar language, they had a very different culture and religion from other Algonquian peoples. English and French explorers visited New Hampshire in 1600–1605, and David Thompson settled at Odiorne's Point in present-day Rye in 1623. The first permanent settlement was at Hilton's Point (present-day Dover). By 1631, the Upper Plantation comprised modern-day Dover, Durham and Stratham; in 1679, it became the "Royal Province". Dummer's War

Dummer's War (1722–1725) is also known as Father Rale's War, Lovewell's War, Greylock's War, the Three Years War, the Wabanaki-New England War, or the Fourth Anglo-Abenaki War. It was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the ...

was fought between the colonists and the Wabanaki Confederacy throughout New Hampshire.

The colony that became the state of New Hampshire was founded on the division in 1629 of a land grant given in 1622 by the Council for New England to Captain John Mason (former governor of Newfoundland) and Sir Ferdinando Gorges

Sir Ferdinando Gorges ( – 24 May 1647) was a naval and military commander and governor of the important port of Plymouth in England. He was involved in Essex's Rebellion against the Queen, but escaped punishment by testifying against the m ...

(who founded Maine). The colony was named New Hampshire by Mason after the English county

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

of Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

, one of the first Saxon shire

Shire is a traditional term for an administrative division of land in Great Britain and some other English-speaking countries such as Australia and New Zealand. It is generally synonymous with county. It was first used in Wessex from the beginn ...

s. Hampshire was itself named after the port of Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

, which was known previously as simply "Hampton".

New Hampshire was first settled by Europeans at Odiorne's Point in Rye (near Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

) by a group of fishermen from England, under David Thompson in 1623, three years after the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

. Early historians believed the first native-born New Hampshirite, John Thompson, was born there.

Fisherman David Thompson had been sent by Mason, to be followed a few years later by Edward and William Hilton. They led an expedition to the vicinity of Dover, which they called Northam. Mason died in 1635 without ever seeing the colony he founded. Settlers from Pannaway, moving to the Portsmouth region later and combining with an expedition of the new Laconia Company (formed 1629) under Captain Neal, called their new settlement Strawbery Banke. In 1638 Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

was founded by John Wheelwright

John Wheelwright (c. 1592–1679) was a Puritan clergyman in England and America, noted for being banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Antinomian Controversy, and for subsequently establishing the town of Exeter, New Hamp ...

.

In 1631, Captain Thomas Wiggin

Captain Thomas Wiggin (1601–1666), often known as Governor Thomas Wiggin, was the first governor of the Upper Plantation of New Hampshire, a settlement that later became part of the Province of New Hampshire in 1679. He was the founder of Strath ...

served as the first governor of the Upper Plantation (comprising modern-day Dover, Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

* Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

and Stratham). All the towns agreed to unite in 1639, but meanwhile Massachusetts had claimed the territory. In 1641, an agreement was reached with Massachusetts to come under its jurisdiction. Home rule of the towns was allowed. In 1653, Strawbery Banke petitioned the General Court of Massachusetts to change its name to Portsmouth, which was granted.

The relationship between Massachusetts and the independent New Hampshirites was controversial and tenuous, and complicated by land claims maintained by the heirs of John Mason. In 1679 King Charles II separated New Hampshire from Massachusetts, issuing a charter for the royal

The relationship between Massachusetts and the independent New Hampshirites was controversial and tenuous, and complicated by land claims maintained by the heirs of John Mason. In 1679 King Charles II separated New Hampshire from Massachusetts, issuing a charter for the royal Province of New Hampshire

The Province of New Hampshire was a colony of England and later a British province in North America. The name was first given in 1629 to the territory between the Merrimack and Piscataqua rivers on the eastern coast of North America, and was nam ...

, with John Cutt

John Cutt (1613 – April 5, 1681) was the first president of the Province of New Hampshire.

Cutt was born in Wales, emigrated to the colonies in 1646, and became a successful merchant and mill owner in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. He was marri ...

as governor. New Hampshire was absorbed into the Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was an administrative union of English colonies covering New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies (except for Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvania). Its political structure represe ...

in 1686, which collapsed in 1689. After a brief period without formal government (the settlements were ''de facto'' ruled by Massachusetts) William III and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 166228 December 1694) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland, co-reigning with her husband, William III & II, from 1689 until her death in 1694.

Mary was the eldest daughter of James, Duke of York, and his first wife ...

issued a new provincial charter in 1691. From 1699 to 1741 the governors of Massachusetts were also commissioned as governors of New Hampshire.

The province's geography placed it on the frontier between British and French colonies in North America, and it was for many years subjected to native claims, especially in the central and northern portions of its territory. Because of these factors it was on the front lines of many military conflicts, including King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand All ...

, Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In E ...

, Father Rale's War

Dummer's War (1722–1725) is also known as Father Rale's War, Lovewell's War, Greylock's War, the Three Years War, the Wabanaki-New England War, or the Fourth Anglo-Abenaki War. It was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the ...

, and King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in t ...

. By the 1740s most of the native population had either been killed or driven out of the province's territory.

Because New Hampshire's governorship was shared with that of Massachusetts, border issues between the two colonies were not properly adjudicated for many years. These issues principally revolved around territory west of the Merrimack River

The Merrimack River (or Merrimac River, an occasional earlier spelling) is a river in the northeastern United States. It rises at the confluence of the Pemigewasset and Winnipesaukee rivers in Franklin, New Hampshire, flows southward into Mas ...

, which issuers of the Massachusetts and New Hampshire charters had incorrectly believed to flow primarily from west to east. In the 1730s New Hampshire political interest led by Lieutenant Governor John Wentworth were able to raise the profile of these issues to colonial officials and the crown in London, even while Governor and Massachusetts native Jonathan Belcher

Jonathan Belcher (8 January 1681/8231 August 1757) was a merchant, politician, and slave trader from colonial Massachusetts who served as both governor of Massachusetts Bay and governor of New Hampshire from 1730 to 1741 and governor of New J ...

preferentially granted land to Massachusetts interests in the disputed area. In 1741 King George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089) ...

ruled that the border with Massachusetts was approximately what it is today, and also separated the governorships of the two provinces. Benning Wentworth

Benning Wentworth (July 24, 1696 – October 14, 1770) was an American merchant and colonial administrator who served as the governor of New Hampshire from 1741 to 1766. While serving as governor, Wentworth is best known for issuing several la ...

in 1741 became the first non-Massachusetts governor since Edward Cranfield

Edward Cranfield ( fl. 1680–1696) was an English colonial administrator.

Cranfield was governor of the Province of New Hampshire from 1682 to 1685, in an administration that was marked by hostility between Cranfield and the colonists.

Cranfiel ...

succeeded John Cutt in the 1680s.

Wentworth promptly complicated New Hampshire's territorial claims by interpreting the provincial charter to include territory west of the Connecticut River

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges at Long Island ...

, and began issuing land grants in this territory, which was also claimed by the Province of New York

The Province of New York (1664–1776) was a British proprietary colony and later royal colony on the northeast coast of North America. As one of the Middle Colonies, New York achieved independence and worked with the others to found the Uni ...

. The so-called New Hampshire Grants

The New Hampshire Grants or Benning Wentworth Grants were land grants made between 1749 and 1764 by the colonial governor of the Province of New Hampshire, Benning Wentworth. The land grants, totaling about 135 (including 131 towns), were made o ...

area became a subject of contention from the 1740s until the 1790s, when it was admitted to the United States as the state of Vermont

Vermont () is a state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to ...

.

Slavery in New Hampshire

As in the other Thirteen Colonies and elsewhere in the colonial Americas, racially conditioned slavery was a firmly established institution in New Hampshire. The New Hampshire Assembly in 1714 passed "An Act To Prevent Disorders In The Night": Notices emphasizing and re-affirming the curfew were published in '' The New Hampshire Gazette'' in 1764 and 1771. "Furthermore, as one of the few colonies that did not impose a tariff on slaves, New Hampshire became a base for slaves to be imported into America then smuggled into other colonies. Every census up to the Revolution showed an increase in black population, though they remained proportionally fewer than in most other New England colonies." Following the Revolution, a powerfully-written petition of 1779 sent by 20 slaves in Portsmouth—members of what historianIra Berlin

Ira Berlin (May 27, 1941 – June 5, 2018) was an American historian, professor of history at the University of Maryland, and former president of Organization of American Historians.

Berlin is the author of such books as ''Many Thousands Gone: T ...

identified as the of enslaved people in his pivotal work ''Many Thousands Gone''—unsuccessfully requested freedom for the enslaved. The New Hampshire legislature would not officially eliminate slavery in the state until 1857, long after the death of many of the signatories. The 1840 United States Census was the last to enumerate any slaves in the households of the state.

While the number of slaves resident in New Hampshire itself dwindled during the course of the 19th century, the state's economy remained closely interlinked with, and dependent upon, the economies of the slave states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

. Slave-produced raw materials, such as cotton for textiles, and slave-manufactured goods were imported. The ship ''Nightingale of Boston'', built in Eliot, Maine

Eliot is a town in York County, Maine, United States. Originally settled in 1623, it was formerly a part of Kittery, Maine, to its east. After Kittery, it is the next most southern town in the state of Maine, lying on the Piscataqua River across f ...

in 1851 and outfitted in Portsmouth, would serve as a slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

before its capture by the African Slave Trade Patrol in 1861, indicating the region's further economic connection to the ongoing Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

.

Revolution: 1775–1815

New Hampshire was one of the

New Hampshire was one of the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

that revolted against British rule during the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

. The Massachusetts Provincial Congress

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress (1774–1780) was a provisional government created in the Province of Massachusetts Bay early in the American Revolution. Based on the terms of the colonial charter, it exercised ''de facto'' control over the ...

called upon the other New England colonies for assistance in raising an army. In response, on May 22, 1775, the New Hampshire Provincial Congress

The Provincial Congresses were extra-legal legislative bodies established in ten of the Thirteen Colonies early in the American Revolution. Some were referred to as congresses while others used different terms for a similar type body. These bodies ...

voted to raise a volunteer force to join the patriot army at Boston. In January 1776, it became the first colony to set up an independent government and the first to establish a constitution, but the latter explicitly stated "we never sought to throw off our dependence on Great Britain", meaning that it was not the first to actually declare its independence (that distinction instead belongs to Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

). The historic attack on Fort William and Mary

Fort William and Mary was a colonial fortification in Britain's worldwide system of defenses, defended by soldiers of the Province of New Hampshire who reported directly to the royal governor. The fort, originally known as "The Castle," was situ ...

(now Fort Constitution) helped supply the cannon and ammunition for the Continental Army that was needed for the Battle of Bunker Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill was fought on June 17, 1775, during the Siege of Boston in the first stage of the American Revolutionary War. The battle is named after Bunker Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts, which was peripherally involved in ...

that took place north of Boston a few months later. New Hampshire raised three regiments for the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

, the 1st, 2nd and 3rd

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* Second#Sexagesimal divisions of calendar time and day, 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (d ...

New Hampshire regiments. New Hampshire Militia The New Hampshire Militia was first organized in 1631 and lasted until 1641, when the area came under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts.

After New Hampshire became an separate colony again in 1679, New Hampshire Colonial Governor John Cutt reorgan ...

units were called up to fight at the Battle of Bunker Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill was fought on June 17, 1775, during the Siege of Boston in the first stage of the American Revolutionary War. The battle is named after Bunker Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts, which was peripherally involved in ...

, Battle of Bennington

The Battle of Bennington was a battle of the American Revolutionary War, part of the Saratoga campaign, that took place on August 16, 1777, on a farm owned by John Green in Walloomsac, New York, about from its namesake, Bennington, Vermont. A r ...

, Saratoga Campaign

The Saratoga campaign in 1777 was an attempt by the British high command for North America to gain military control of the strategically important Hudson River valley during the American Revolutionary War. It ended in the surrender of the British ...

and the Battle of Rhode Island. John Paul Jones

John Paul Jones (born John Paul; July 6, 1747 July 18, 1792) was a Scottish-American naval captain who was the United States' first well-known naval commander in the American Revolutionary War. He made many friends among U.S political elites ( ...

' ship the Sloop-of-war

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

USS ''Ranger'' and the frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

USS ''Raleigh'' were built in Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. At the 2020 census it had a population of 21,956. A historic seaport and popular summer tourist destination on the Piscataqua River bordering the state of Maine, Portsmou ...

, along with other naval ships for the Continental Navy

The Continental Navy was the navy of the United States during the American Revolutionary War and was founded October 13, 1775. The fleet cumulatively became relatively substantial through the efforts of the Continental Navy's patron John Adams ...

and privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s to hunt down British merchant shipping.

Concord

Concord may refer to:

Meaning "agreement"

* Pact or treaty, frequently between nations (indicating a condition of harmony)

* Harmony, in music

* Agreement (linguistics), a change in the form of a word depending on grammatical features of other ...

was named the state capital in 1808.

Industrialization, abolitionism and nativism-- politics: 1815–1860

In 1832, New Hampshire saw a curious development: the founding of the

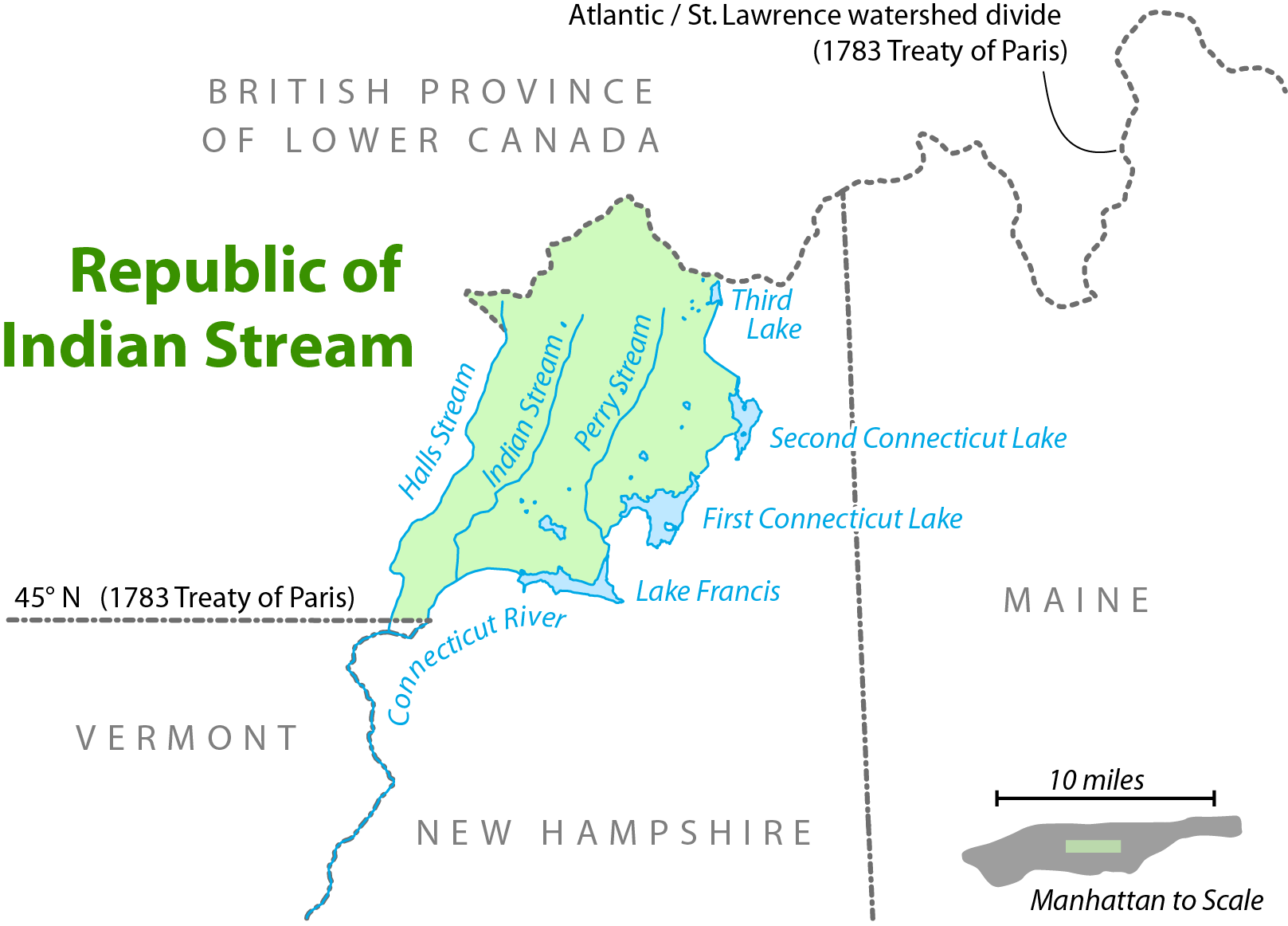

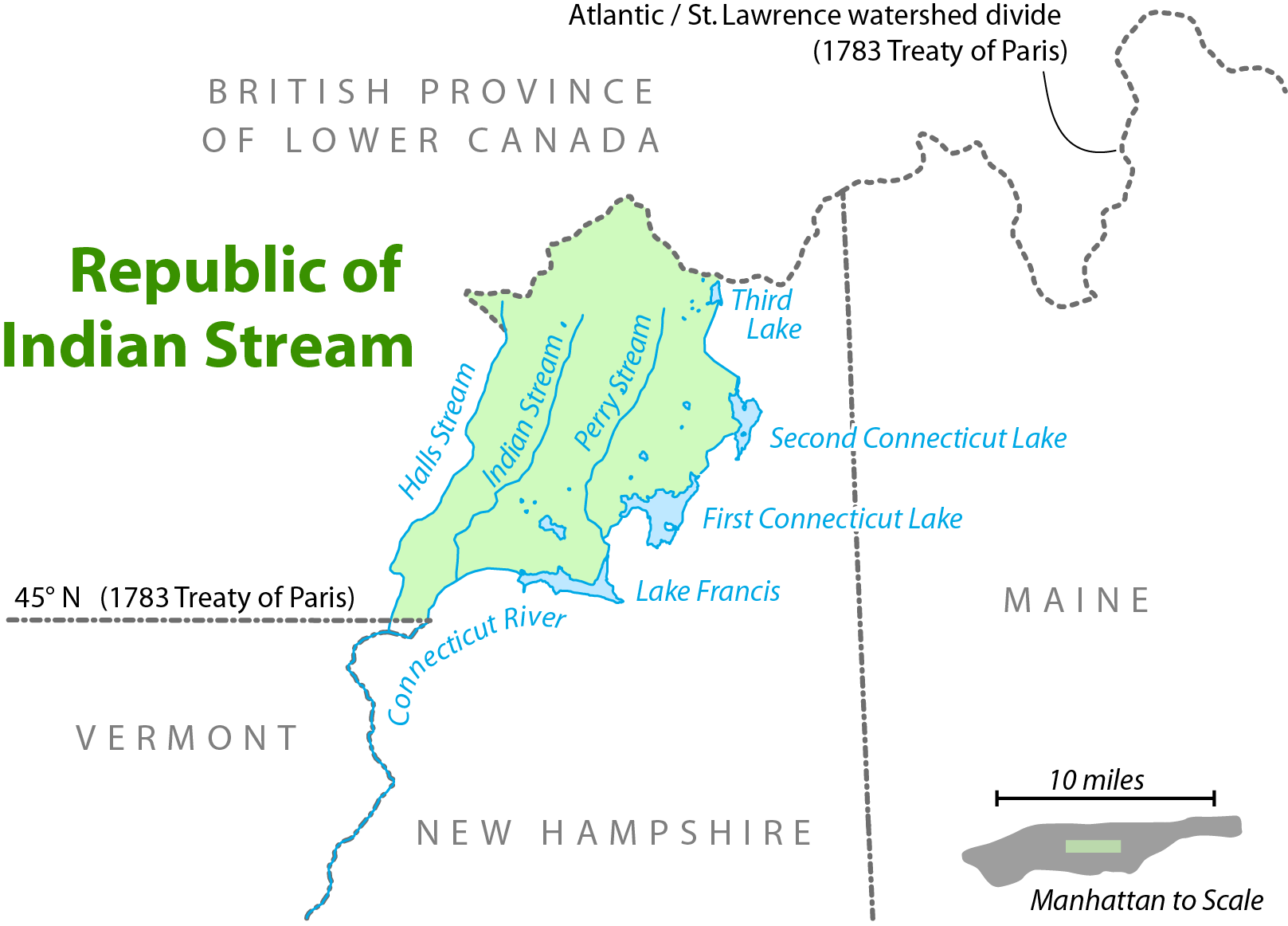

In 1832, New Hampshire saw a curious development: the founding of the Republic of Indian Stream

The Republic of Indian Stream or Indian Stream Republic was an unrecognized republic in North America, along the section of the border that divides the current Canadian province of Quebec from the U.S. state of New Hampshire. It existed from July ...

on its northern border with Canada over the unresolved post-revolutionary war border issue. In 1835 the so-called "republic" was annexed by New Hampshire, with the dispute finally resolved in 1842 by the Webster–Ashburton Treaty

The Webster–Ashburton Treaty, signed August 9, 1842, was a treaty that resolved several border issues between the United States and the British North American colonies (the region that became Canada). Signed under John Tyler's presidency, it ...

.

Abolitionists from Dartmouth College founded the experimental, interracial Noyes Academy

The Noyes Academy was a racially integrated school, which also admitted women, founded by New England abolitionists in 1835 in Canaan, New Hampshire, near Dartmouth College, whose then-abolitionist president, Nathan Lord, was "the only seated ...

in Canaan, New Hampshire

Canaan is a town in Grafton County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 3,794 at the 2020 census. It is the location of Mascoma State Forest. Canaan is home to the Cardigan Mountain School, the town's largest employer.

The main v ...

in 1835, at a point in history when slaves still appeared in the households of New Hampshire in the census. Rural opponents of the school eventually dragged the school away with oxen before lighting it ablaze to protest integrated education, within months of the school's founding.

Abolitionist sentiment was a strong undercurrent in the state, with significant support given the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

of John P. Hale. However the conservative Jacksonian Democrats usually maintained control, under the leadership of editor Isaac Hill

Isaac Hill (April 6, 1788March 22, 1851) was an American politician, journalist, political commentator and newspaper editor who was a United States senator and the 16th governor of New Hampshire, serving two consecutive terms.

Hill was born on ...

.

Nativism aimed at the rapid influx of Irish Catholics characterized the short-lived secret Know Nothing

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

movement, and its instrument the "American Party." Appearing out of nowhere, they scored a landslide in 1855. They won 51% of the vote against a divided opposition. They won over 94% of the men who voted Free Soil the year before. They won 79% of the Whigs, plus 15% of Democrats and 24% of those who abstained in the 1854 election for governor. In full control of the legislature, the Know Nothings enacted their entire agenda. According to Lex Renda, they battled traditionalism and promoted rapid modernization. They extended the waiting period for citizenship to slow down the growth of Irish power; they reformed the state courts. They expanded the number and power of banks; they strengthened corporations; they defeated a proposed 10-hour law that would help workers. They reformed the tax system; increased state spending on public schools; set up a system to build high schools; prohibited the sale of liquor; and they denounced the expansion of slavery in the western territories.

The Whigs and Free Soil parties both collapsed in New Hampshire in 1854-55. In the 1855 fall elections the Know Nothings again swept the state against the Democrats and the small new Republican party. When the Know Nothing ("American" Party) collapsed in 1856 and merged with the Republicans, New Hampshire now had a two party system with the Republican Party headed by Amos Tuck

Amos Tuck (August 2, 1810 – December 11, 1879) was an American attorney and politician in New Hampshire and a founder of the Republican Party.

Early life and education

Born in Parsonsfield, Maine, August 2, 1810, the son of John Tuck, a s ...

edging out the Democrats.

Civil War: 1861–1865

After Abraham Lincoln gave speeches in March 1860, he was well regarded. However, the radical wing of the Republican Party increasingly took control. As early as January 1861, top officials were secretly meeting with GovernorJohn A. Andrew

John Albion Andrew (May 31, 1818 – October 30, 1867) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts. He was elected in 1860 as the 25th Governor of Massachusetts, serving between 1861 and 1866, and led the state's contributions to ...

of Massachusetts to coordinate plans in case the war came. Plans were made to rush militia units to Washington in an emergency.

New Hampshire fielded 31,650 enlisted men and 836 officers during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

; of these, about 20% died of disease, accident or combat.Bruce D. Heald, ''New Hampshire and the Civil War: Voices from the Granite State'' (History Press, 2012). The state provided eighteen volunteer infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripted ...

s (thirteen of which were raised in 1861 in response to Lincoln's call to arms), three rifle

A rifle is a long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting, with a barrel that has a helical pattern of grooves ( rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus on accuracy, rifles are typically designed to be held with ...

regiments (who served in the 1st United States Sharpshooters

The 1st United States Sharpshooters were an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. During battle, the mission of the sharpshooter was to kill enemy targets of importance (''i.e''., officers, NCOs, and arti ...

and 2nd United States Sharpshooters), one cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

battalion (the 1st New Hampshire Volunteer Cavalry, which was attached to the 1st New England Volunteer Cavalry), and two artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

units (the 1st New Hampshire Light Battery

1st New Hampshire Light Artillery was an artillery battery that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Service

The 1st New Hampshire Artillery was organized in Manchester, New Hampshire and mustered in on September 21, 1861, for ...

and 1st New Hampshire Heavy Artillery), as well as additional men for the Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral zone, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and ...

and Marine Corps

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

.

Among the most celebrated of New Hampshire's units was the 5th New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry, commanded by Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Edward Ephraim Cross

Edward Ephraim Cross (April 22, 1832 – July 3, 1863) was a newspaperman and an officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Journalist

Cross was born in Lancaster, New Hampshire, son of Ephram and Abigail (Everett) Cross; att ...

.Mike Pride & Mark Travis, ''My Brave Boys: To War with Colonel Cross and the Fighting Fifth'', University Press of New England, 2001. Called the "Fighting Fifth" in newspaper accounts, the regiment was considered among the Union's best both during the war (Major General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

called the regiment "refined gold" in 1863) and by historians afterward. The Civil War veteran and early Civil War historian William F. Fox determined that this regiment had the highest number of battle-related deaths of any Union regiment. The 20th-century historian Bruce Catton

Charles Bruce Catton (October 9, 1899 – August 28, 1978) was an American historian and journalist, known best for his books concerning the American Civil War. Known as a narrative historian, Catton specialized in popular history, featuring int ...

said that the Fifth New Hampshire was "one of the best combat units in the army" and that Cross was "an uncommonly talented regimental commander."

The critical post of state Adjutant General was held in 1861-64 by elderly politician Anthony C. Colby (1792-1873) and his son Daniel E. Colby (1816-1891). They were patriotic, but were overwhelmed with the complexity of their duties. The state had no track of men who enlisted after 1861; no personnel records or information on volunteers, substitutes, or draftees. There was no inventory of weaponry and supplies. Nathaniel Head (1828-1883) took over in 1864, obtained an adequate budget and office staff, and reconstructed the missing paperwork. As a result, widows, orphans, and disabled veterans received the postwar payments they had earned.Miller, ed., ''States at war'' (2013) 1: 366-7

Prosperity, depression and war: 1865–1950

French Canadian

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

migration to the state was significant, and at the turn of the century, French Canadians represented 16 percent of the state's population, and one-fourth the population of Manchester.Wilfrid H. Paradis, ''Upon This Granite: Catholicism in New Hampshire, 1647-1997'' (1998), pp. 111-12. Polish immigration to the state was also significant; there were about 850 Polish Americans in Manchester in 1902.

The textile industry was hit hard by the depression and growing competition from southern mills. The closing of the Amoskeag Mills in 1935 was a major blow to Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

, as was the closing of the former Nashua Manufacturing Company

The Nashua Manufacturing Company was a cotton textile manufacturer in Nashua, New Hampshire that operated from 1823 to 1945. It was one of several textile companies that helped create what became the city of Nashua, creating roads, churches and its ...

mill in Nashua Nashua may refer to:

* Nashaway people, Native American tribe living in 17th-century New England

Places

In Australia:

* Nashua, New South Wales

In the United States:

* Nashua, California

* Nashua, Iowa

* Nashua, Minnesota

* Nashua, Kansas City ...

in 1949 and the bankruptcy of the Brown Company

The Brown Company, known as the Brown Corporation in Canada, was a pulp and papermaking company based in Berlin, New Hampshire, United States. They closed their doors during the 1980s.

History

H. Winslow & Company

In 1852, a group of Portla ...

paper mill in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

in the 1940s, which led to new ownership.

Modern New Hampshire: 1950–present

The post-World War II decades have seen New Hampshire increase its economic and cultural links with the greater Boston, Massachusetts, region. This reflects a national trend, in which improved highway networks have helped metropolitan areas expand into formerly rural areas or small nearby cities. The replacement of the Nashua textile mill with defense electronics contractorSanders Associates

Sanders Associates was a defense contractor in Nashua, New Hampshire, United States, from 1951 until it was sold in 1986. It is now part of BAE Systems Electronics & Integrated Solutions, a subsidiary of BAE Systems. It concentrated on developi ...

in 1952 and the arrival of minicomputer giant Digital Equipment Corporation

Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC ), using the trademark Digital, was a major American company in the computer industry from the 1960s to the 1990s. The company was co-founded by Ken Olsen and Harlan Anderson in 1957. Olsen was president unt ...

in the early 1970s helped lead the way toward southern New Hampshire's role as a high-tech adjunct of the Route 128

The following highways are numbered 128:

Canada

* New Brunswick Route 128

* Ontario Highway 128 (former)

* Prince Edward Island Route 128

Costa Rica

* National Route 128

India

* National Highway 128 (India)

Japan

* Japan National Route 128 ...

corridor.

The postwar years saw the rise of New Hampshire's political primary for President of the United States, which as the first primary in the quadrennial campaign season draws enormous attention.

See also

*Abenaki

The Abenaki (Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was predom ...

*History of New England

New England is the oldest clearly defined region of the United States, being settled more than 150 years before the American Revolution. The first English colony in New England, Plymouth Colony, was established in 1620 by Pilgrims fleeing religi ...

*List of newspapers in New Hampshire in the 18th century

This is a list of newspapers in New Hampshire.

Daily newspapers

* ''The Beachcomber'' of Hampton Beach, New Hampshire, Hampton Beach

* ''The Berlin Daily Sun'' of Berlin, New Hampshire, Berlin

* ''The Citizen (Laconia), The Citizen'' of Laconi ...

* New Hampshire historical markers

* Timeline of Manchester, New Hampshire

* Union (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union, also known as the North, referred to the United States led by President Abraham Lincoln. It was opposed by the secessionist Confederate States of America (CSA), informally called "the Confederacy" or "t ...

References

Resources

Online books: New Hampshire

''New Hampshire: a Guide to the Granite State'': "Chronology"

Boston: Houghton Mifflin

American Guide Series

The American Guide Series includes books and pamphlets published from 1937 to 1941 under the auspices of the Federal Writers' Project (FWP), a Depression-era program that was part of the larger Works Progress Administration in the United States. T ...

. Federal Writers' Project

The Federal Writers' Project (FWP) was a federal government project in the United States created to provide jobs for out-of-work writers during the Great Depression. It was part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a New Deal program. It ...

(1938)

Further reading

* ''Appleton's Annual Cyclopedia...1863'' (1864), detailed coverage of events in all countriesonline

for online copies see Annual Cyclopaedia. Each year includes several pages on each U.S. state. * Anderson, Leon W. ''To this day: the 300 years of the New Hampshire Legislature'' (Phoenix Pub., 1981). * Belknap, Jeremy. ''The History of New Hampshire'' (1791–1792) 3 vol classi

Volume 1

or th

1862 edition with corrections.

at books. Google. * Cole, Donald B. ''Jacksonian Democracy in New Hampshire'' (Harvard UP, 1970

online

* Daniell, Jere. ''Experiment in Republicanism: New Hampshire politics and the American Revolution, 1741-1794'' (197

online

* Daniell, Jere. ''Colonial New Hampshire: A History'' (1982), scholarly history

online

* Dwight, Timothy. ''Travels Through New England and New York'' (circa 1800) 4 vol. (1969

online

* French, Laurence Armand. ''Frog Town: Portrait of a French Canadian Parish in New England'' (University Press of America, 2014

online

* Guyol, Philip Nelson. ''Democracy Fights: A History of New Hampshire in World War II'' (Dartmouth, 1951). * Hareven, Tamara K., and Randolph Langenbach. ''Amoskeag: Life and work in an American factory-city'' (UPNE, 1995) The Amoskeag textile factory in Manchester was the largest in the world; this is the story of its workers

online

* Heffernan, Nancy Coffey, and Ann Page Stecker. ''New Hampshire: crosscurrents in its development'' (1986) short popular history

online

* Jager, Ronald and Grace Jager. ''The Granite State New Hampshire: An Illustrated History'' (2000) popular. * Kilbourne, Frederick Wilkinson. ''Chronicles of the White Mountains'' (1916

online

* Kinney, Charles B. ''Church & state: the struggle for separation in New Hampshire 1630-1900'' (1955). * Lafferty, Ben Paul. ''American Intelligence: Small-Town News and Political Culture in Federalist New Hampshire'' (U of Massachusetts Press, 2020

online

* Lafferty, Ben Paul. "Joseph Dennie and The Farmer's Weekly Museum: Readership and Pseudonymous Celebrity in Early National Journalism," ''American Nineteenth Century History'', 15:1, 67-87, DOI: 10.1080/14664658.2014.892302 *McClintock, John N

''Colony, Province, State, 1623-1888: History of New Hampshire''

Published 1889. * Morison, Elizabeth Forbes and

Elting E. Morison

Elting Elmore Morison (December 14, 1909, Milwaukee, Wisconsin – April 20, 1995, Peterborough, New Hampshire) was an American historian of technology, military biographer, author of nonfiction books, and essayist. He was an MIT professor and th ...

. ''New Hampshire: A Bicentennial History'' (1976); popular

* Nichols, Roy F. ''Franklin Pierce: Young Hickory of the Granite Hills'' (1931)online

* Palfrey, John Gorham

''History of New England'' (5 vol 1859–90)

* Renda, Lex. ''Running on the Record: Civil War-Era Politics in New Hampshire'' (University of Virginia Press, 1997

online

** Renda, Lex. "Credit and Culpability: New Hampshire State Politics During the Civil War," ''Historical New Hampshire'' 48 (Spring, 1993), 3-84. reprinted in his book. * Sanborn, Edwin David

''History of New Hampshire, from Its First Discovery to the Year 1830''

(1875, 422 pages) * Sewell, Richard H. ''John P. Hale and the politics of abolition'' (1965

online

* Smith, Norman W. ''A mature frontier: the New Hampshire economy 1790-1850'' ''Historical New Hampshire'' 24#1 (1969) 3-19. * Squires, J. Duane. ''The Granite State of the United States: A History of New Hampshire from 1623 to the Present'' (1956) vol 1 * Stackpole, Everett S. ''History of New Hampshire'' (4 vol 1916-1922

vol 4 online covers Civil War and late 19th century

* Thompson, Woodrow. "History of research on glaciation in the White Mountains, New Hampshire (USA)." ''Géographie physique et Quaternaire'' 53.1 (1999): 7-24

online

* Turner, Lynn Warren. ''The Ninth State: New Hampshire's Formative Years'' (1983

* Upton, Richard Francis. ''Revolutionary New Hampshire: An Account of the Social and Political Forces Underlying the Transition from Royal Province to American Commonwealth'' (1936) * Whiton, John Milton

''Sketches of the History of New-Hampshire, from Its Settlement in 1623, to 1833''.

Published 1834, 222 pages. * Wilson, H. F. ''The Hill Country of Northern New England: Its Social and Economic History, 1790–1930'' (1936) * {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of New Hampshire History of New Hampshire,

New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...