History Of Seville on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Seville has been one of the most important cities in the

Seville has been one of the most important cities in the  After the discovery of the Americas, Seville became the economic centre of the Spanish Empire as its port monopolised the trans-oceanic trade and the

After the discovery of the Americas, Seville became the economic centre of the Spanish Empire as its port monopolised the trans-oceanic trade and the

During this period Hispalis was the district capital of the Hispalense, one of the four legal convents (''Conventi iuridici'', judicial assemblies the governors summoned with some frequency in the major cities) of the imperial province of Baetica.

The Romans Latinised the Iberian name of the city, 'Ispal', and called it ''Hispalis''. Although the city was rebuilt after being pillaged by the Carthaginians, the name 'Hispalis' appeared for the first time in the

During this period Hispalis was the district capital of the Hispalense, one of the four legal convents (''Conventi iuridici'', judicial assemblies the governors summoned with some frequency in the major cities) of the imperial province of Baetica.

The Romans Latinised the Iberian name of the city, 'Ispal', and called it ''Hispalis''. Although the city was rebuilt after being pillaged by the Carthaginians, the name 'Hispalis' appeared for the first time in the  In 45 BC, after the

In 45 BC, after the

In the 5th century Hispalis was taken by a succession of Germanic invaders: the Vandals led by

In the 5th century Hispalis was taken by a succession of Germanic invaders: the Vandals led by

The Muslim general

The Muslim general  On 1 October 844, when most of the Iberian peninsula was controlled by the

On 1 October 844, when most of the Iberian peninsula was controlled by the  The city grew rich during the years when it was a dependent of the Emirate and later of the Caliphate of Córdoba. After the fall of the caliphate Ishbilya became independent and was capital of one of the more powerful

The city grew rich during the years when it was a dependent of the Emirate and later of the Caliphate of Córdoba. After the fall of the caliphate Ishbilya became independent and was capital of one of the more powerful  From the late 11th century to the mid-12th century the Taifa kingdoms were united under the

From the late 11th century to the mid-12th century the Taifa kingdoms were united under the

In 1247, the Christian King

In 1247, the Christian King  During the reign of Ferdinand's son,

During the reign of Ferdinand's son,  After Ferdinand's death in the Real Alcázar, his son, Alfonso X the Wise, assumed the throne. Alfonso was an intellectual, and a great patron of the sciences and the arts, hence his title. He distinguished himself as poet, astronomer, musician, linguist and legislator. Alfonso's son, Sancho IV of Castile, tried to usurp the throne from his father, but the people of Seville remained loyal to their scholar king. The symbol 'NO8DO' is believed to have originated when, according to legend, Alfonso X rewarded the fidelity of the ''Sevillanos'' with the words that now appear on the official coat of arms and the flag of the city of Seville.

The Battle of Salado in 1340 resulted in the opening of maritime trade between southern and northern Europe through the Strait of Gibraltar and a growing presence of Italian and Flemish merchants in Seville, who were key to the inclusion of the southern routes of the Crown of Castile in that commerce. The Black Death of 1348, the great earthquake of 1356 (which caused some casualties and serious damage to many buildings, including the great mosque), and the demographic and economic consequences of the crisis of the fourteenth century were devastating to the city. This aggravation of pre-existing social conflicts found an outlet in the

After Ferdinand's death in the Real Alcázar, his son, Alfonso X the Wise, assumed the throne. Alfonso was an intellectual, and a great patron of the sciences and the arts, hence his title. He distinguished himself as poet, astronomer, musician, linguist and legislator. Alfonso's son, Sancho IV of Castile, tried to usurp the throne from his father, but the people of Seville remained loyal to their scholar king. The symbol 'NO8DO' is believed to have originated when, according to legend, Alfonso X rewarded the fidelity of the ''Sevillanos'' with the words that now appear on the official coat of arms and the flag of the city of Seville.

The Battle of Salado in 1340 resulted in the opening of maritime trade between southern and northern Europe through the Strait of Gibraltar and a growing presence of Italian and Flemish merchants in Seville, who were key to the inclusion of the southern routes of the Crown of Castile in that commerce. The Black Death of 1348, the great earthquake of 1356 (which caused some casualties and serious damage to many buildings, including the great mosque), and the demographic and economic consequences of the crisis of the fourteenth century were devastating to the city. This aggravation of pre-existing social conflicts found an outlet in the

The influence and prestige of Seville expanded greatly during the 16th century following the Spanish arrival in America, the commerce of the port driving the prosperity which led to the period of its greatest splendour. The Puerto de Indias in Seville became the principal port linking Spain to Latin America in 1503 with the monopoly created by the royal decree of Queen

The influence and prestige of Seville expanded greatly during the 16th century following the Spanish arrival in America, the commerce of the port driving the prosperity which led to the period of its greatest splendour. The Puerto de Indias in Seville became the principal port linking Spain to Latin America in 1503 with the monopoly created by the royal decree of Queen  All goods imported from the New World had to pass through the Casa de Contratación before being distributed throughout the rest of Spain. A 'golden age' of development commenced in Seville, due to its being the only port awarded the royal monopoly for trade with the growing Spanish colonies in the Americas, and the influx of riches from them. Since only sailing ships leaving from and returning to the inland port of Seville could engage in trade with the Spanish Americas, merchants from Europe and other trade centers needed to go to Seville to acquire trade goods from the New World.

A twenty percent tax, the ''

All goods imported from the New World had to pass through the Casa de Contratación before being distributed throughout the rest of Spain. A 'golden age' of development commenced in Seville, due to its being the only port awarded the royal monopoly for trade with the growing Spanish colonies in the Americas, and the influx of riches from them. Since only sailing ships leaving from and returning to the inland port of Seville could engage in trade with the Spanish Americas, merchants from Europe and other trade centers needed to go to Seville to acquire trade goods from the New World.

A twenty percent tax, the '' In the middle of the 13th century, the Dominicans, in order to prepare missionaries for work among the Moors and Jews, had organized schools for the teaching of Arabic, Hebrew, and Greek. To cooperate in this work and to enhance the prestige of Seville, Alfonso the Wise in 1254 established in the city 'general schools' (escuelas generales) of Arabic and Latin. Pope Alexander IV, by the Bull of 21 June 1260, recognised this foundation as a ''generale litterarum studium''. Rodrigo de Santaello, archdeacon of the cathedral and commonly known as Maese Rodrigo, began the construction of a building for a university in 1472. The Catholic Monarchs published the royal decree creating the university in 1502, and in 1505 Pope Julius II granted the Bull of authorization—this is considered the official founding of the present

In the middle of the 13th century, the Dominicans, in order to prepare missionaries for work among the Moors and Jews, had organized schools for the teaching of Arabic, Hebrew, and Greek. To cooperate in this work and to enhance the prestige of Seville, Alfonso the Wise in 1254 established in the city 'general schools' (escuelas generales) of Arabic and Latin. Pope Alexander IV, by the Bull of 21 June 1260, recognised this foundation as a ''generale litterarum studium''. Rodrigo de Santaello, archdeacon of the cathedral and commonly known as Maese Rodrigo, began the construction of a building for a university in 1472. The Catholic Monarchs published the royal decree creating the university in 1502, and in 1505 Pope Julius II granted the Bull of authorization—this is considered the official founding of the present

Important historic buildings from this period include the

Important historic buildings from this period include the  The ''

The '' The College of the Annunciation of the Professed House of the

The College of the Annunciation of the Professed House of the  The Royal Audiencia of Seville (Real Audiencia de los Grados de Sevilla) was a court of the Crown of Castile, established in 1525 during the reign of Charles I. It had judicial powers as an appeals court in civil and criminal cases, but had no powers of government. The building that housed the Audiencia of Seville is located in the Plaza de San Francisco de Sevilla, and is currently the headquarters of the financial institution Cajasol. The building was built between 1595 and 1597, although justice had been administered earlier in another building at the same place called the Casa Cuadra since shortly after the reconquest of the city in 1248. The building has been renovated several times.

The Royal Mint of Seville ''(Casa de la Moneda)'', built 1585–1587, was the circulation center where gold and silver from the New world were smelted into the

The Royal Audiencia of Seville (Real Audiencia de los Grados de Sevilla) was a court of the Crown of Castile, established in 1525 during the reign of Charles I. It had judicial powers as an appeals court in civil and criminal cases, but had no powers of government. The building that housed the Audiencia of Seville is located in the Plaza de San Francisco de Sevilla, and is currently the headquarters of the financial institution Cajasol. The building was built between 1595 and 1597, although justice had been administered earlier in another building at the same place called the Casa Cuadra since shortly after the reconquest of the city in 1248. The building has been renovated several times.

The Royal Mint of Seville ''(Casa de la Moneda)'', built 1585–1587, was the circulation center where gold and silver from the New world were smelted into the  The

The

In the 17th century Seville fell into a deep economic and urban decline as a consequence of the general economic crisis that struck Europe and Spain in particular. This decline was aggravated in Seville by river floods and the great plague of 1649, which may have killed some 60,000 people, nearly half of the existing population of 130,000. Also at this time the spirit of the

In the 17th century Seville fell into a deep economic and urban decline as a consequence of the general economic crisis that struck Europe and Spain in particular. This decline was aggravated in Seville by river floods and the great plague of 1649, which may have killed some 60,000 people, nearly half of the existing population of 130,000. Also at this time the spirit of the

The economic decline of this period was not accompanied by a corresponding decline of the arts. During the reign of the Habsburg king

The economic decline of this period was not accompanied by a corresponding decline of the arts. During the reign of the Habsburg king  Zurbarán (1598–1664) is known for his religious paintings depicting monks, nuns, and martyred saints, and for his still lifes. Zurbarán was called the ''Spanish

Zurbarán (1598–1664) is known for his religious paintings depicting monks, nuns, and martyred saints, and for his still lifes. Zurbarán was called the ''Spanish  Murillo (1617–1682) was born in Seville and lived there this first twenty-six years. He spent two periods of a few years in Madrid, but lived and worked mostly in Seville. He began his art studies under

Murillo (1617–1682) was born in Seville and lived there this first twenty-six years. He spent two periods of a few years in Madrid, but lived and worked mostly in Seville. He began his art studies under

The Seminary School of the University of Navigators ''(Colegio Seminario de la Universidad de Mareantes)'' was founded in 1681 by the Spanish Crown during the reign of Charles II to "...house, bring up and educate orphaned and abandoned boys for service in the navy and fleets of the Indies". The crown commissioned the building of the

The Seminary School of the University of Navigators ''(Colegio Seminario de la Universidad de Mareantes)'' was founded in 1681 by the Spanish Crown during the reign of Charles II to "...house, bring up and educate orphaned and abandoned boys for service in the navy and fleets of the Indies". The crown commissioned the building of the  The

The

La Real Fábrica de Tabacos de Sevilla: Vision histórica general

Access date 2012-04-09. The Royal Tobacco Factory is a remarkable example of 18th century industrial architecture, and one of the oldest buildings of its type in Europe. The building covers a roughly rectangular area of 185 by 147 metres (610 by 480 feet), with slight protrusions at the corners. The only building in Spain that covers a larger surface area is the monastery-palace of

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

since ancient times; the first settlers of the site have been identified with the Tartessian culture. The destruction of their settlement is attributed to the Carthaginians, giving way to the emergence of the Roman city of Hispalis, built very near the Roman colony of Itálica

Italica ( es, Itálica) was a ancient Romans, Roman town founded by Italic peoples, Italic settlers in Hispania; its site is close to the town of Santiponce, part of the province of Seville in modern-day Spain. It was founded in 206 BC by Roman ...

(now Santiponce), which was only 9 km northwest of present-day Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

. Itálica, the birthplace of the Roman emperors Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

and Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania B ...

, was founded in 206–205 BC. Itálica is well preserved and gives an impression of how Hispalis may have looked in the later Roman period. Its ruins are now an important tourist attraction. Under the rule of the Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic peoples, Germanic su ...

, Hispalis housed the royal court on some occasions.

In al-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

(Muslim Spain) the city was first the seat of a ''kūra'' (Spanish: ''cora''), or territory, of the Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba ( ar, خلافة قرطبة; transliterated ''Khilāfat Qurṭuba''), also known as the Cordoban Caliphate was an Islamic state ruled by the Umayyad dynasty from 929 to 1031. Its territory comprised Iberia and parts o ...

, then made capital of the Taifa of Seville

The Taifa of Seville ( ''Ta'ifat-u Ishbiliyyah'') was an Arab kingdom which was ruled by the Abbadid dynasty. It was established in 1023 and lasted until 1091, in what is today southern Spain and Portugal. It gained independence from the Calipha ...

(Arabic: طائفة أشبيليّة, ''Ta'ifa Ishbiliya''), which was incorporated into the Christian Kingdom of Castile under Ferdinand III, who was first to be interred in the cathedral. After the Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

, Seville was resettled by the Castilian aristocracy; as capital of the kingdom it was one of the Spanish cities with a vote in the Castilian Cortes

Cortes, Cortés, Cortês, Corts, or Cortès may refer to:

People

* Cortes (surname), including a list of people with the name

** Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), a Spanish conquistador

Places

* Cortes, Navarre, a village in the South border of N ...

, and on numerous occasions served as the seat of the itinerant court. The Late Middle Ages found the city, its port, and its colony of active Genoese merchants in a peripheral but nonetheless important position in European international trade, while its economy suffered severe demographic and social shocks such as the Black Death of 1348 and the anti-Jewish revolt of 1391.

After the discovery of the Americas, Seville became the economic centre of the Spanish Empire as its port monopolised the trans-oceanic trade and the

After the discovery of the Americas, Seville became the economic centre of the Spanish Empire as its port monopolised the trans-oceanic trade and the Casa de Contratación

The ''Casa de Contratación'' (, House of Trade) or ''Casa de la Contratación de las Indias'' ("House of Trade of the Indies") was established by the Crown of Castile, in 1503 in the port of Seville (and transferred to Cádiz in 1717) as a cro ...

(House of Trade) wielded its power, opening a Golden Age of arts and letters. Coinciding with the Baroque period of European history, the 17th century in Seville represented the most brilliant flowering of the city's culture; then began a gradual economic and demographic decline as navigation of the Guadalquivir River

The Guadalquivir (, also , , ) is the fifth-longest river in the Iberian Peninsula and the second-longest river with its entire length in Spain. The Guadalquivir is the only major navigable river in Spain. Currently it is navigable from the Gulf ...

became increasingly difficult until finally the trade monopoly and its institutions were transferred to Cádiz.

The city was revitalised in the 19th century with rapid industrialisation and the building of rail connections, and as in the rest of Europe, the artistic, literary, and intellectual Romantic movement found its expression here in reaction to the Industrial Revolution. The 20th century in Seville saw the horrors of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

, decisive cultural milestones such as the Ibero-American Exposition of 1929

The Ibero-American Exposition of 1929 (Spanish: ''Exposición iberoamericana de 1929'') was a world's fair held in Seville, Spain, from 9 May 1929 until 21 June 1930. Countries in attendance of the exposition included: Portugal, the United Stat ...

and Expo'92, and the city's election as the capital of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

.

Prehistory and antiquity

The original core of the city, in the neighbourhood of the present-day street, Cuesta del Rosario, dates to the 8th century BC, when Seville was on an island in the Guadalquivir. Archaeological excavations in 1999 found anthropic remains under the north wall of the RealAlcázar

An alcázar, from Arabic ''al-Qasr'', is a type of Islamic castle or palace in the Iberian Peninsula (also known as al-Andalus) built during Muslim rule between the 8th and 15th centuries. They functioned as homes and regional capitals for gover ...

dating to the 8th–7th century BC.

The town was called ''Spal'' or ''Ispal'' by the Tartessians, the indigenous pre-Roman Iberian people of Tartessos

Tartessos ( es, Tarteso) is, as defined by archaeological discoveries, a historical civilization settled in the region of Southern Spain characterized by its mixture of local Paleohispanic and Phoenician traits. It had a proper writing system ...

(the name given to their kingdom by the Greeks); they controlled the Guadalquivir Valley and were important trading partners of the neighbouring Phoenician trading colonies on the coast, which later passed to the Carthaginians. The Tartessian culture was succeeded by that of the Turdetani

The Turdetani were an ancient pre-Roman people of the Iberian Peninsula, living in the valley of the Guadalquivir (the river that the Turdetani called by two names: ''Kertis'' and ''Rérkēs'' (Ῥέρκης); Romans would call the river by th ...

(so-called by the Romans) and the Turduli

The Turduli (Greek ''Tourduloi'') or Turtuli were an ancient pre-Roman people of the southwestern Iberian Peninsula.

Location

The Turduli tribes lived mainly in the south and centre of modern Portugal – in the east of the provinces of Beira Li ...

.

''Ispal'' advanced in its civilisation and was culturally enriched by its frequent contact with the

peaceful Phoenician traders. Commercial colonisation activity in the region changed dramatically in the 6th century BC when the Carthaginians achieved dominance of the western Mediterranean after the fall of the Phoenician city-states of Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

to the Persian empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, wikt:𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎶, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an History of Iran#Classical antiquity, ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Bas ...

. This new phase of colonisation involved the expansion of Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

territory through military conquest; later Greek sources impute the destruction of ''Tartessos'' to Carthaginian military assaults on the Seville of the Cuesta del Rosario, assuming it to be Tartessian at the time. Carthaginians had caused the collapse of ''Tartessos'' by 530 BC, either by armed conflict or by cutting off Greek trade in support of the Phoenician colony of Gades (present-day Cádiz). Carthage also besieged and took over Gades at this time.

Roman Hispalis

During theSecond Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

, Roman troops under the command of the general Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (, , ; 236/235–183 BC) was a Roman general and statesman, most notable as one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the best military com ...

achieved a decisive victory in 206 BC over the full Carthaginian levy at Ilipa (now the city of Alcalá del Río

Alcalá del Río is a municipality in Seville, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, ...

), near Ispal, which resulted in the evacuation of Hispania by the Punic commanders and their successors in the southern peninsula. Before returning to Rome, Scipio settled a contingent of veteran soldiers on a hill close to Hispalis, but far enough away to deter belligerents, and thus founded Italica

Italica ( es, Itálica) was a Roman town founded by Italic settlers in Hispania; its site is close to the town of Santiponce, part of the province of Seville in modern-day Spain. It was founded in 206 BC by Roman general Scipio as a settleme ...

, the first provincial city in which the inhabitants had all the rights of Roman citizenship. The two cities had different characters: Híspalis was a Hispano-Roman town of craftsmen and a regional financial and commercial hub; while Italica, the birthplace of the Roman emperors Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

and Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania B ...

, was residential and fully Roman. Hispalis developed into one of the great market and industrial centres of Hispania, and Italica remained a typically Roman residential city.

During this period Hispalis was the district capital of the Hispalense, one of the four legal convents (''Conventi iuridici'', judicial assemblies the governors summoned with some frequency in the major cities) of the imperial province of Baetica.

The Romans Latinised the Iberian name of the city, 'Ispal', and called it ''Hispalis''. Although the city was rebuilt after being pillaged by the Carthaginians, the name 'Hispalis' appeared for the first time in the

During this period Hispalis was the district capital of the Hispalense, one of the four legal convents (''Conventi iuridici'', judicial assemblies the governors summoned with some frequency in the major cities) of the imperial province of Baetica.

The Romans Latinised the Iberian name of the city, 'Ispal', and called it ''Hispalis''. Although the city was rebuilt after being pillaged by the Carthaginians, the name 'Hispalis' appeared for the first time in the Augustan History

The ''Historia Augusta'' (English: ''Augustan History'') is a late Roman collection of biographies, written in Latin, of the Roman emperors, their junior colleagues, designated heirs and usurpers from 117 to 284. Supposedly modeled on the sim ...

in 49 BC, five years before Julius Caesar granted it the status of Roman colony to celebrate his victory over Pompey in 54 BC. Isidore

Isidore ( ; also spelled Isador, Isadore and Isidor) is an English and French masculine given name. The name is derived from the Greek name ''Isídōros'' (Ἰσίδωρος) and can literally be translated to "gift of Isis." The name has survived ...

says in his Etymologies, XV 1, 71:

In English:

Although this etymology is not accurate, it is likely that the city was considered untenable as a residence by the Romans for its instability, being built on alluvial soil and frequently threatened by flooding of the Guadalquivir River. Isidore's reference to the foundation pilings of Hispalis was confirmed when their remains were discovered by archaeological excavations in Calle Sierpes, where, according to the historian Antonio Collantes de Teran, "piles were sharpened on their lower ends, regularly driven into the sandy subsoil, and obviously served to consolidate the foundation in that place." Similar findings have been made at the Plaza de San Francisco. Salvador Ordóñez Agulla, however, asserts that these pilings are the remains of ship piers of the river (called the Baetis in Roman times) port.

Roman Civil War

This is a list of civil wars and organized civil disorder, revolts and rebellions in ancient Rome (Roman Kingdom, Roman Republic, and Roman Empire) until the fall of the Western Roman Empire (753 BCE – 476 CE). For the Eastern Roman Empire or B ...

ended at the Battle of Munda

The Battle of Munda (17 March 45 BC), in southern Hispania Ulterior, was the final battle of Caesar's civil war against the leaders of the Optimates. With the military victory at Munda and the deaths of Titus Labienus and Gnaeus Pompeius (elde ...

, Híspalis built city walls and a forum, completed in 49 BC, as it grew into one of the preeminent cities of Hispania; the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

poet Ausonius

Decimius Magnus Ausonius (; – c. 395) was a Roman poet and teacher of rhetoric from Burdigala in Aquitaine, modern Bordeaux, France. For a time he was tutor to the future emperor Gratian, who afterwards bestowed the consulship on him. H ...

ranked it tenth among the most important cities of the Roman Empire. Hispalis was a city of great mercantile activity and an important commercial port. The area around the present Plaza de la Alfalfa was the intersection of the two main axes of the city, the Cardo Maximus which ran north to south, and the Decumanus Maximus which ran east to west. In this area was the Roman forum, which included temples, baths, markets and public buildings; the Curia

Curia (Latin plural curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally likely had wider powers, they came ...

and the Basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica is a large public building with multiple functions, typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East. The building gave its name ...

may have been near the present-day Plaza del Salvador.

What was formerly the eastern part of the Decumanus Maximus is modern-day Calle Aguilas, while the northern section of the Cardus Maximus coincides with Calle Alhondiga. This leads to the conclusion that what is today La Plaza del Alfalfa, at the junction of these two streets, may have been the location of the Imperial Forum, while the nearby Plaza del Salvador was probably the site of the Curia and Basilica.

In the mid-second century the Moors (''Mauri'' in ancient Latin) twice attempted invasions, and were finally driven back by Roman archers.

Tradition says Christianity came early to the city; in the year 287, two potter girls, the sisters Justa and Rufina

Saints Justa and Rufina (Ruffina) ( es, Santa Justa y Santa Rufina) are venerated as martyrs. They are said to have been martyred at Hispalis (Seville) during the 3rd century.

Only St. Justa (sometimes "Justus" in early manuscripts) is mentione ...

, now patron saints of the city, were martyred, according to legend, for an incident that arose when they refused to sell their wares for use in a pagan festival. In anger, locals broke all of their dishes and pots, and Justa and Rufina retaliated by smashing an image of the goddess Venus or of Salambo. They were both imprisoned, tortured and killed by the Roman authorities.

Middle Ages

Visigothic rule

In the 5th century Hispalis was taken by a succession of Germanic invaders: the Vandals led by

In the 5th century Hispalis was taken by a succession of Germanic invaders: the Vandals led by Gunderic

Gunderic ( la, Gundericus; 379–428), King of Hasding Vandals (407-418), then King of Vandals and Alans (418–428), led the Hasding Vandals, a Germanic tribe originally residing near the Oder River, to take part in the barbarian invasions of th ...

in 426, the Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own names ...

King Rechila

Rechila (died 448) was the Suevic king of Galicia from 438 until his death. There are few primary sources for his life, but Hydatius was a contemporary Christian (non- Arian) chronicler in Galicia.

When his father, Hermeric, turned ill in 438, h ...

in 441, and finally the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

, who would control the city until the 8th century, their supremacy challenged for a time by the Byzantine presence on the Mediterranean coast. After the defeat of the Franks in 507, the Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic peoples, Germanic su ...

abandoned its former capital in Toulouse, north of the Pyrenees, and was gaining ground on the various peoples scattered throughout the Hispanic territory by moving the royal residence to different cities until it was fixed in Toledo. Seville was chosen during the reigns of Amalaric

Amalaric ( got, *Amalareiks; Spanish and Portuguese: ''Amalarico''; 502–531) was king of the Visigoths from 522 until his death in battle in 531. He was a son of king Alaric II and his first wife Theodegotha, daughter of Theoderic the Great.

Bi ...

, Theudis

Theudis (Spanish: ''Teudis'', Portuguese: ''Têudis''), ( 480 – June 548) was king of the Visigoths in Hispania from 531 to 548.

Biography

An Ostrogoth, he was the sword-bearer of Theodoric the Great, who sent him to govern the Visigothic king ...

and Theudigisel

Theudigisel (or Theudegisel) (in Latin ''Theudigisclus'' and in Spanish, Galician and Portuguese ''Teudiselo'', ''Teudigiselo'', or ''Teudisclo''), ( 500 – December 549) was king of the Visigoths in Hispania and Septimania (548–549). Some Visi ...

. This last king was assassinated at a banquet for the nobles of Hispalis in an episode known as the 'Supper of Candles' in 549. The cause is debated and may be a reflection of the division between the Hispanic communities and the Visigoths (Baetica was more susceptible to outbreaks of dissension than the center of the Iberian peninsula), or even a conspiracy of Visigothic nobles.

Under Visigothic rule, Híspalis was known as ''Spali''. After the short reign of Theudigisel, the successor of Theudis, Agila I was elected king in 549. The Visigoths were engaged in internal power struggles when the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I took the opportunity to try to conquer Baetica. After many battles and the defeat of several of their leaders, the Visigoths eventually managed to conquer every corner of the region. In 572, Leuvigild, the designee to reign, obtained the kingdom after the death of his brother Liuva I. In 585, his son Hermenegild

Saint Hermenegild or Ermengild (died 13 April 585; es, San Hermenegildo; la, Hermenegildus, from Gothic ''*Airmana-gild'', "immense tribute"), was the son of king Liuvigild of the Visigothic Kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula and southern France ...

, after converting to Catholicism (in contradistinction to the Arianism of former kings) rebelled against his father and proclaimed himself king in the city. Legend tells that in order to force his way, Leuvigild changed the course of the Guadalquivir River, hindering the passage of the inhabitants and causing a drought. The old channel passed by the present-day Alameda de Hercules. In 586, Leuvigild's other son Reccared I

Reccared I (or Recared; la, Flavius Reccaredus; es, Flavio Recaredo; 559 – December 601; reigned 586–601) was Visigothic King of Hispania and Septimania. His reign marked a climactic shift in history, with the king's renunciation of Arianis ...

acceded to the throne and with Spali itself went on to enjoy a time of great prosperity. After the Muslim invasion of Spain, the city became, next to Cordoba, one of the most important in Western Europe.

Christianity

In Visigothic times two Catholic prelates of Hispalis,Leander

Leander is one of the protagonists in the story of Hero and Leander in Greek mythology.

Leander may also refer to:

People

* Leander (given name)

* Leander (surname)

Places

* Leander, Kentucky, United States, an unincorporated community

* Le ...

and Isidore

Isidore ( ; also spelled Isador, Isadore and Isidor) is an English and French masculine given name. The name is derived from the Greek name ''Isídōros'' (Ἰσίδωρος) and can literally be translated to "gift of Isis." The name has survived ...

, are notable; they were brothers and both were canonised as saints. Leander, in addition to his intensive labors in reforming the regular and the secular clergy, converted Hermenegild, viceroy of Baetica and son of King Leuvigild (an Arian adherent), to Catholicism. The Visigothic prince rebelled against his father and began an uprising supported by the Hispano-Roman nobility, upon the failure of which Hermenegild was executed in 585. After the death of Leuvigild in 586, Leander had a prominent role in the Third Council of Toledo in 589, where the new king Reccared I, Hermenegild's brother, converted to Catholicism along with all the Visigothic nobility. Isidore wrote a set of twenty encyclopaedic books known as the Etymologies that contained all the knowledge of the ancient Greco-Roman culture (medicine, music, astronomy, theology, etc.), which was of great influence throughout medieval Europe.

Muslim al-Andalus

The Muslim general

The Muslim general Musa bin Nusayr

Musa ibn Nusayr ( ar, موسى بن نصير ''Mūsá bin Nuṣayr''; 640 – c. 716) served as a Umayyad governor and an Arab general under the Umayyad caliph Al-Walid I. He ruled over the Muslim provinces of North Africa (Ifriqiya), and direct ...

commanded Tariq ibn Ziyad

Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād ( ar, طارق بن زياد), also known simply as Tarik in English, was a Berber commander who served the Umayyad Caliphate and initiated the Muslim Umayyad conquest of Visigothic Hispania (present-day Spain and Portugal) ...

to invade Spain in the late spring of 711 with an army of 9,000 men. That summer, these forces fought a large army raised by the Visigothic king Roderic

Roderic (also spelled Ruderic, Roderik, Roderich, or Roderick; Spanish and pt, Rodrigo, ar, translit=Ludharīq, لذريق; died 711) was the Visigothic king in Hispania between 710 and 711. He is well-known as "the last king of the Goths". He ...

, who was killed at the Battle of Guadalete

The Battle of Guadalete was the first major battle of the Umayyad conquest of Hispania, fought in 711 at an unidentified location in what is now southern Spain between the Christian Visigoths under their king, Roderic, and the invading forces of t ...

. When Tariq met little resistance as his divisions moved through the Visigothic kingdom, it is said that Musa was jealous that such a victory should be won by a Berber freedman. Accompanied by his son Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa ibn Nusayr ( ar, عبد العزيز بن موسى) was the first governor of Al-Andalus, in modern-day Spain and Portugal. He was the son of Musa ibn Nusayr, the governor of Ifriqiya. ‘Abd al-Aziz had a long history of polit ...

, Musa landed in Spain in 712 with his own army of 18,000 veteran Arabs and proceeded to the further conquest of Visigothic territory. They took Medina-Sidonia

Medina Sidonia is a city and municipality in the province of Cádiz in the autonomous community of Andalusia, southern Spain. Considered by some to be the oldest city in Europe, it is used as a military defence location because of its elevation. ...

and Carmona

Carmona may refer to:

Places Angola

* the former name of the town of Uíge

Costa Rica

* Carmona District, Nandayure, a district in Guanacaste Province

India

* Carmona, Goa, a village located in the Salcette district of South Goa, India

...

; then Prince Abd al-Aziz took Hispalis in 712 after a long siege. Until his assassination at the hands of his cousins in 716, the city served as the capital of al-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

, the name given the Iberian Peninsula as a province of the Islamic empire of the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

.

Following the siege and conquest of the city, its Roman name, Hispalis, was changed to the Arabic ''Išbīliya'' (إشبيلية) or Ishbiliya. During this period of Muslim rule a richly complex culture developed. The emirate favored the expansion of Islam through concessions to those Christians who converted to Islam, called Muwallads, privileges not enjoyed by those who remained Christian, known as (Mozarabs

The Mozarabs ( es, mozárabes ; pt, moçárabes ; ca, mossàrabs ; from ar, مستعرب, musta‘rab, lit=Arabized) is a modern historical term for the Iberian Christians, including Christianized Iberian Jews, who lived under Muslim rule in A ...

). The city was called by the name ''Ixbilia'' in the Mozarabic language

Mozarabic, also called Andalusi Romance, refers to the medieval Romance varieties spoken in the Iberian Peninsula in territories controlled by the Islamic Emirate of Córdoba and its successors. They were the common tongue for the majority of ...

, which became ''Sivilia'', and finally reached the form "Sevilla", as it is known today.

The Umayyad dynasty was established in al-Andalus when Abd al-Rahman I took ''Išbīliya'' without violence in March 756, then won Córdoba in the Battle of Musarah where he defeated Yusuf al-Fihri, the governor of al-Andalus, who had ruled independently since the collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate in 750. After his victory Abd al-Rahman I proclaimed himself the Emir of al-Andalus, which later became part of the Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba ( ar, خلافة قرطبة; transliterated ''Khilāfat Qurṭuba''), also known as the Cordoban Caliphate was an Islamic state ruled by the Umayyad dynasty from 929 to 1031. Its territory comprised Iberia and parts o ...

when Abd ar-Rahman III

ʿAbd al-Rahmān ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ḥakam al-Rabdī ibn Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil () or ʿAbd al-Rahmān III (890 - 961), was the Umayyad Emir of Córdoba from 912 to 92 ...

proclaimed himself Caliph in 929, and ''Išbīliya'' was made the capital of a ''kūra'' (territory). Abd al-Rahman I appointed his Umayyad kinsman Abd al-Malik ibn Umar ibn Marwan

Abd al-Malik ibn Umar ibn Marwan ibn al-Hakam ( ar, عبد الملك ابن عمر بن مروان بن الحكم, ʿAbd al-Malik ibn ʿUmar ibn Marwān ibn al-Ḥakam; – ), also known as al-Marwani, was an Umayyad prince, general and govern ...

governor of Seville. By 774 Abd al-Malik definitively crushed opposition to the Umayyads by the Arab garrisons and local elites of Seville and its territory. His family settled in the town and became a major component of the government in Cordoba, serving as viziers and generals of the successive emirs and caliphs, and some of his descendants attempted to wrest the caliphate from the descendants of Abd al-Rahman I.

The Ad-Abbas Mosque was built in 830, it currently holds the Church of El Salvador.

On 1 October 844, when most of the Iberian peninsula was controlled by the

On 1 October 844, when most of the Iberian peninsula was controlled by the Emirate of Córdoba

The Emirate of Córdoba ( ar, إمارة قرطبة, ) was a medieval Islamic kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula. Its founding in the mid-eighth century would mark the beginning of seven hundred years of Muslim rule in what is now Spain and Port ...

, a flotilla

A flotilla (from Spanish, meaning a small ''flota'' (fleet) of ships), or naval flotilla, is a formation of small warships that may be part of a larger fleet.

Composition

A flotilla is usually composed of a homogeneous group of the same class ...

of about 80 Viking ships, after attacking Asturias, Galicia and Lisbon, ascended the Guadalquivir to ''Išbīliya'', and besieged it for seven days, inflicting many casualties and taking numerous hostages with the intent to ransom them. Another group of Vikings had gone to Cádiz to plunder while those in ''Išbīliya'' waited on ''Qubtil'' ''(Isla Menor)'', an island in the river, for the ransom money to arrive. Meantime, the emir of Cordoba, Abd ar-Rahman II

Abd ar-Rahman II () (792–852) was the fourth ''Umayyad'' Emir of Córdoba in al-Andalus from 822 until his death. A vigorous and effective frontier warrior, he was also well known as a patron of the arts.

Abd ar-Rahman was born in Toledo, Spai ...

, prepared a military contingent to meet them, and on November 11 a pitched battle ensued on the grounds of ''Talayata'' (Tablada). The Vikings held their ground, but the results were catastrophic for the invaders, who suffered a thousand casualties; four hundred were captured and executed, some thirty ships were destroyed. It was not a total victory for the emir's forces, but the Viking survivors had to negotiate a peace to leave the area, surrendering their plunder and the hostages they had taken to sell as slaves, in exchange for food and clothing. The Vikings made several incursions in the years 859, 966 and 971, but with intentions more diplomatic than bellicose, although an attempt at invasion in 971 was frustrated when the Viking fleet was totally annihilated. Vikings attacked Tablada again in 889 at the instigation of Kurayb ibn Khaldun of Seville. Over time, the few Norse survivors converted to Islam and settled as farmers in the area of Coria del Río, Carmona and Moron, where they engaged in animal husbandry and made dairy products (reputedly the origin of Sevillian cheese).

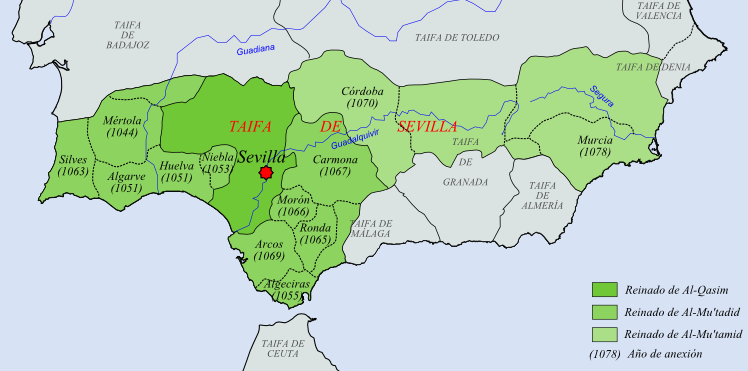

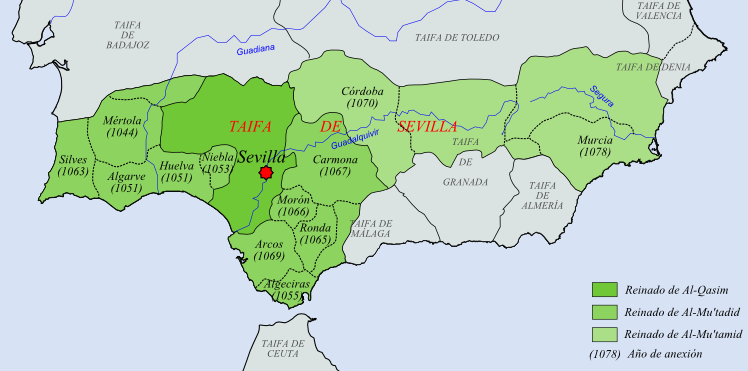

The city grew rich during the years when it was a dependent of the Emirate and later of the Caliphate of Córdoba. After the fall of the caliphate Ishbilya became independent and was capital of one of the more powerful

The city grew rich during the years when it was a dependent of the Emirate and later of the Caliphate of Córdoba. After the fall of the caliphate Ishbilya became independent and was capital of one of the more powerful Taifa

The ''taifas'' (singular ''taifa'', from ar, طائفة ''ṭā'ifa'', plural طوائف ''ṭawā'if'', a party, band or faction) were the independent Muslim principalities and kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula (modern Portugal and Spain), re ...

s from 1023 until 1091, under the rule of the Abbadi

Abbadi or Abbadids or Ibad (Arabic : بنو عباد) is an Arab Muslim dynasty and one of the biggest Bedouin tribes in Jordan. Abbadi is the second most common surname in Jordan. They are arguably descended from "Adnan" Adnanites (Arabic: عدن ...

, a Muslim dynasty of Arabic origin. However, Christians often made threatening advances into the Taifa, and in 1063, a Christian incursion under the command of Ferdinand I of Castile discovered how weak the military force was that occupied these realms. Putting up little resistance, in a few years the king of Išbīliya, Al-Mutamid, had to buy peace and pay an annual tribute, making Išbīliya for the first time a tributary of Castile.

The Alcázar of Seville

The Royal Alcázars of Seville ( es, Reales Alcázares de Sevilla), historically known as al-Qasr al-Muriq (, ''The Verdant Palace'') and commonly known as the Alcázar of Seville (), is a royal palace in Seville, Spain, built for the Christian ...

(''Reales Alcázares de Sevilla'' or Royal Alcázars of Seville) is a royal palace originally built as a Moorish fort. No other Muslim building in Spain has been so well preserved. Inhabited for a time by the Abbatid, Almoravid, and Almohad kings, its embattled enclosure became the dwelling of Ferdinand I, and was rebuilt by Peter of Castile

Peter ( es, Pedro; 30 August 133423 March 1369), called the Cruel () or the Just (), was King of Castile and León from 1350 to 1369. Peter was the last ruler of the main branch of the House of Ivrea. He was excommunicated by Pope Urban V for ...

(1353–64), who employed Granadans and Muslim subjects of his own ''(mudejares)'' as its architects. Its principal entrance, with Arab façade, is in the Plaza de la Monteria, once occupied by the dwellings of the hunters (monteros) of Espinosa. The principal features of the Alcázar are: the ''Patio de las doncellas'' (Court of the Ladies), restored by Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, with its fifty-two uniform columns of white marble supporting interlaced arches and its gallery of precious arabesques; as well as the Hall of Ambassadors, which, with its cupola, dominates the rest of the building—its walls are covered with fine azulejos (glazed tiles) and Arab decorations.

From the late 11th century to the mid-12th century the Taifa kingdoms were united under the

From the late 11th century to the mid-12th century the Taifa kingdoms were united under the Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that ...

(of Saharan origin), and after the collapse of the Almoravid empire, in 1149 the town was taken by the Almohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fo ...

(of North African origin). These were boom times economically and culturally for Ishbilya; great architectural works were built, among them: the minaret, called Giralda

The Giralda ( es, La Giralda ) is the bell tower of Seville Cathedral in Seville, Spain. It was built as the minaret for the Great Mosque of Seville in al-Andalus, Moorish Spain, during the reign of the Almohad dynasty, with a Renaissance-style ...

(1184–1198), of the great mosque; the Almohad palace, ''Al-Muwarak'', on the present site of the Alcázar

An alcázar, from Arabic ''al-Qasr'', is a type of Islamic castle or palace in the Iberian Peninsula (also known as al-Andalus) built during Muslim rule between the 8th and 15th centuries. They functioned as homes and regional capitals for gover ...

; and the pontoon-bridge connecting Triana on the opposite bank of the Guadalquivir to Seville.

The Torre del Oro

The Torre del Oro ( ar, بُرْج الذَّهَب, burj aḏẖ-ḏẖahab, lit=Tower of Gold) is a dodecagonal military watchtower in Seville, southern Spain. It was erected by the Almohad Caliphate in order to control access to Seville via th ...

(Tower of Gold) is a 12-sided military watchtower

A watchtower or watch tower is a type of fortification used in many parts of the world. It differs from a regular tower in that its primary use is military and from a turret in that it is usually a freestanding structure. Its main purpose is to ...

built during the time of the Almohad dynasty

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fo ...

. The tower, situated near the bank of the Guadalquivir

The Guadalquivir (, also , , ) is the fifth-longest river in the Iberian Peninsula and the second-longest river with its entire length in Spain. The Guadalquivir is the only major navigable river in Spain. Currently it is navigable from the Gulf ...

, was built around 1200 by order of the Muslim Governor Abu Elda, who ordered a great iron chain to be drawn across the river, with two military watchtowers built on opposite sides. These served as anchor points to control access to Seville via the waterway. The surviving tower was given the name "Torre del Oro", supposedly because it was decorated with golden azulejo

''Azulejo'' (, ; from the Arabic ''al- zillīj'', ) is a form of Spanish and Portuguese painted tin-glazed ceramic tilework. ''Azulejos'' are found on the interior and exterior of churches, palaces, ordinary houses, schools, and nowadays, resta ...

tiles. During the Muslim rule it was used as a prison and as a shelter during floods, among other purposes.

Castillian conquest

In 1247, the Christian King

In 1247, the Christian King Ferdinand III of Castile

Ferdinand III ( es, Fernando, link=no; 1199/120130 May 1252), called the Saint (''el Santo''), was King of Castile from 1217 and King of León from 1230 as well as King of Galicia from 1231. He was the son of Alfonso IX of León and Berenguela of ...

and Leon began the conquest of Andalusia. After conquering Jaén and Córdoba, he seized the villages surrounding the city, Carmona

Carmona may refer to:

Places Angola

* the former name of the town of Uíge

Costa Rica

* Carmona District, Nandayure, a district in Guanacaste Province

India

* Carmona, Goa, a village located in the Salcette district of South Goa, India

...

Lora del Rio and Alcalá del Rio, and kept a standing army in the vicinity, the siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

lasting for fifteen months and causing havoc in the local population. The decisive action took place in May 1248 when Ramon Bonifaz sailed up the Guadalquivir and severed the Triana bridge that made the provisioning of the city from the farms of the Aljarafe possible. The city surrendered on 23 November 1248.

The Catholic religion was confined to the parish Church of Saint Ildefonso until the restoration following the reconquest of the city by Ferdinand. At that time the Bishop of Cordova, Gutierre de Olea, purified the great mosque and prepared it for celebration of the mass on 22 December. The king deposited in the new Seville Cathedral

The Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See ( es, Catedral de Santa María de la Sede), better known as Seville Cathedral, is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Seville, Andalusia, Spain. It was registered in 1987 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, along ...

two famous images of the Blessed Virgin: "Our Lady of the Kings", an ivory statue which Ferdinand always carried with him in battle; and the silver image, "Our Lady of the See".

The royal residence and the court were itinerant, so there was no permanent capital. Burgos and Toledo disputed the priority; thereafter the court most often resided in Seville, the king's favorite city. On 30 May 1252, King Ferdinand III died in the Alcázar; he was buried in the cathedral, formerly the great mosque, under an epitaph written in Latin, Castilian, Arabic and Hebrew, a fitting tribute to his sobriquet of "King of the three religions". Ferdinand was canonised in 1671; his feastday on 30 May is a local holiday in Seville, he being its patron saint.

During the reign of Ferdinand's son,

During the reign of Ferdinand's son, Alfonso X

Alfonso X (also known as the Wise, es, el Sabio; 23 November 1221 – 4 April 1284) was King of Castile, León and Galicia from 30 May 1252 until his death in 1284. During the election of 1257, a dissident faction chose him to be king of Germ ...

the Wise, Seville remained one of the capitals of the kingdom, as the seat of government now rotated between Toledo, Murcia and Seville. Alfonso ordered the construction of the Gothic Palace of the Alcázar and built the Church of Santa Ana ''(Iglesia de Santa Ana)'' in the Triana neighbourhood, the first Catholic church built in Seville after Muslim rule ended in the city; its architecture combines the early Gothic and the Mudéjar styles.

A great patron of learning, in 1254 Alfonso X founded the Estudio General o Universidad de Sevilla for instruction in Latin and Arabic; it did not continue, however—the present University of Seville is considered to have been founded in 1505. The spirit of the king's desire to gather all knowledge, organise it, and disseminate it with missionary zeal is clearly reflected in the ''Siete Partidas

The ''Siete Partidas'' (, "Seven-Part Code") or simply ''Partidas'', was a Castilian statutory code first compiled during the reign of Alfonso X of Castile (1252–1284), with the intent of establishing a uniform body of normative rules for th ...

'' (Seven-Part Code), one of the great foundational works of the Middle Ages. This is a judicial code based on Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the ''Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor J ...

and composed by a group of legal scholars chosen by Alfonso himself. It may be said that the king was architect and editor of this compendious and magisterial work of cooperative scholarship, known originally as the "Book of Laws"; this and other works he patronised established Castilian as a language of higher learning in Europe.

Before his death, Ferdinand III had long planned the invasion of North Africa, and at the beginning of his own reign, Alfonso X appealed to Pope Alexander IV to endorse such an incursion as a religious crusade, and even built shipyards at Seville for that purpose. In 1260, he appointed a sea governor ''(adelantado de la mar)'', and the port of Salé, (Arabic:Salâ), on the Atlantic coast of Morocco was occupied briefly. Encouraged by the apparent success of that raid, Alfonso summoned the Cortes to Seville in January 1261 to seek counsel, but no further action was taken. The king may have decided that before undertaking any other ventures in Africa, it would be prudent to gain control of all ports of access to the Iberian peninsula. Years later, the king again summoned the Cortes to Seville in the fall of 1282; to raise monies for waging his war against the Moors, he proposed a debasement of the coinage, to which the assembly reluctantly consented.

"NO8DO", which appears on the city's coat of arms, is the official motto and the subject of one of the many legends of Seville. The motto is an heraldic pun in Spanish, i.e., a rebus

A rebus () is a puzzle device that combines the use of illustrated pictures with individual letters to depict words or phrases. For example: the word "been" might be depicted by a rebus showing an illustrated bumblebee next to a plus sign (+) ...

combining the Spanish syllables (NO and DO) and a drawing in between of the figure "8". The figure represents a skein of yarn, or in Spanish, a ''madeja''. When read aloud, "No madeja do" sounds like "No me ha dejado", which means "It evillehas not abandoned me".

The story of how NO8DO came to be the motto of the city has undoubtedly been embellished throughout the centuries, but history tells that after the conquest of Seville from the Muslims in 1248, King Ferdinand III moved his court to the former Muslim palace, the Alcázar of Seville.

anti-Judaism

Anti-Judaism is the "total or partial opposition to Judaism as a religion—and the total or partial opposition to Jews as adherents of it—by persons who accept a competing system of beliefs and practices and consider certain genuine Judai ...

revolt of 1391, inspired by the anti-Semitic sermons of Ferran Martine, the Archdeacon

An archdeacon is a senior clergy position in the Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, St Thomas Christians, Eastern Orthodox churches and some other Christian denominations, above that o ...

of Ecija. The Jewish quarter of Seville, one of the largest Jewish communities of the Iberian peninsula, virtually disappeared because of murders and forced mass conversions. Thereafter the converso

A ''converso'' (; ; feminine form ''conversa''), "convert", () was a Jew who converted to Catholicism in Spain or Portugal, particularly during the 14th and 15th centuries, or one of his or her descendants.

To safeguard the Old Christian po ...

community of new Christian converts inherited the condition of scapegoat endured by their forebears.

During a stay of the Catholic Monarchs in Seville (1477), Alonso de Ojeda, the Prior of the Dominicans of Seville and a loyal advisor to Queen Isabella, urged action against the ''conversos'' and the founding of the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand ...

. The Queen agreed and the Holy Office of the Inquisition was established in 1478. The city was chosen for the first auto de fe

Auto may refer to:

* An automaton

* An automobile

* An autonomous car

* An automatic transmission

* An auto rickshaw

* Short for automatic

* Auto (art), a form of Portuguese dramatic play

* ''Auto'' (film), 2007 Tamil comedy film

* Auto (play), ...

, after which six people were burned alive on 6 February 1481.

Early Modern Era

Seville's Golden age in the 16th century

The European discovery of the New World in 1492 was an event of supreme importance for the city which would become the European port of departure to the Americas and the commercial capital of the Spanish Empire. Seville was in the late 15th century one of Castile's major ports, already a cosmopolitan and international commercial centre, trading mainly with England, Flanders and Genoa. The Muslim minority suffered a blow in 1502 when it was forced to convert to Christianity (theMoriscos

Moriscos (, ; pt, mouriscos ; Spanish for "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church and the Spanish Crown commanded to convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed the open ...

), to achieve religious conformity in the name of national unity.

The influence and prestige of Seville expanded greatly during the 16th century following the Spanish arrival in America, the commerce of the port driving the prosperity which led to the period of its greatest splendour. The Puerto de Indias in Seville became the principal port linking Spain to Latin America in 1503 with the monopoly created by the royal decree of Queen

The influence and prestige of Seville expanded greatly during the 16th century following the Spanish arrival in America, the commerce of the port driving the prosperity which led to the period of its greatest splendour. The Puerto de Indias in Seville became the principal port linking Spain to Latin America in 1503 with the monopoly created by the royal decree of Queen Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as List of Aragonese royal consorts, Queen consort ...

; this granted the city exclusive privileges as the port of entry and exit for all the Indies trade. To administer this commercial activity, the Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being bot ...

founded the Casa de Contratación

The ''Casa de Contratación'' (, House of Trade) or ''Casa de la Contratación de las Indias'' ("House of Trade of the Indies") was established by the Crown of Castile, in 1503 in the port of Seville (and transferred to Cádiz in 1717) as a cro ...

, or House of Trade, (though it was not then located in a specific building, its documents can now be seen in the Archive of the Indies

The Archivo General de Indias (, "General Archive of the Indies"), housed in the ancient merchants' exchange of Seville, Spain, the ''Casa Lonja de Mercaderes'', is the repository of extremely valuable archival documents illustrating the history ...

). From here all voyages of exploration and trade had to be approved, thus giving Seville control of the wealth transported from the New World, enforced by laws regarding the contracting of voyages and which routes the ships must follow. Together the Casa de Contratación and the Consulado de mercaderes

The ''Consulado de mercaderes'' was the merchant guild of Seville founded in 1543; the Consulado enjoyed virtual monopoly rights over goods shipped to America, in a regular and closely controlled West Indies Fleet, and handled much of the silve ...

(the merchant guild founded in 1543) regulated all mercantile, scientific and judicial intercourse with the New World. Consequently, the city grew to over 100,000 inhabitants, making it the largest and most urbanised city in Spain at the time; more of its streets were bricked or paved than in any other in the peninsula.

All goods imported from the New World had to pass through the Casa de Contratación before being distributed throughout the rest of Spain. A 'golden age' of development commenced in Seville, due to its being the only port awarded the royal monopoly for trade with the growing Spanish colonies in the Americas, and the influx of riches from them. Since only sailing ships leaving from and returning to the inland port of Seville could engage in trade with the Spanish Americas, merchants from Europe and other trade centers needed to go to Seville to acquire trade goods from the New World.

A twenty percent tax, the ''

All goods imported from the New World had to pass through the Casa de Contratación before being distributed throughout the rest of Spain. A 'golden age' of development commenced in Seville, due to its being the only port awarded the royal monopoly for trade with the growing Spanish colonies in the Americas, and the influx of riches from them. Since only sailing ships leaving from and returning to the inland port of Seville could engage in trade with the Spanish Americas, merchants from Europe and other trade centers needed to go to Seville to acquire trade goods from the New World.

A twenty percent tax, the ''quinto real

The ''quinto real'' or the quinto del rey, the "King's fifth", was a 20% tax established in 1504 that Spain levied on the mining of precious metals. The tax was a major source of revenue for the Spanish monarchy. In 1723 the tax was reduced to 10%. ...

'', was levied by the Casa on all precious metals

Precious metals are rare, naturally occurring metallic chemical elements of high economic value.

Chemically, the precious metals tend to be less reactive than most elements (see noble metal). They are usually ductile and have a high lustre. ...

entering Spain. Trade with the overseas possessions was handled by the merchants' guild based in Seville, the ''Consulado de Mercaderes'', which worked in conjunction with the Casa de Contratación. Since it controlled most of the trade in the Spanish colonies, the Consulado was able to maintain its own monopoly and keep prices high in all the colonies, and even had a part in royal politics. The Consulado thus effectively manipulated the government and the citizenry of both Spain and the colonies, and grew very rich and powerful.

In turn Seville became a metropolis with consulates of all the European governments, and was the home of merchants from all across the continent who settled there to represent their companies. The factories established in the barrio of Triana were famous for their wares, including soap, silk for export to Europe, and ceramics. The city developed into a multicultural centre that nurtured the flowering of the arts, especially architecture, painting, sculpture and literature, thus playing an important role in the cultural achievements of the Spanish Golden Age

The Spanish Golden Age ( es, Siglo de Oro, links=no , "Golden Century") is a period of flourishing in arts and literature in Spain, coinciding with the political rise of the Spanish Empire under the Catholic Monarchs of Spain and the Spanish H ...

''(El Siglo de Oro)''. The advent of the printing press in Spain led to the development of a sophisticated Sevillian literary salon.

In the middle of the 13th century, the Dominicans, in order to prepare missionaries for work among the Moors and Jews, had organized schools for the teaching of Arabic, Hebrew, and Greek. To cooperate in this work and to enhance the prestige of Seville, Alfonso the Wise in 1254 established in the city 'general schools' (escuelas generales) of Arabic and Latin. Pope Alexander IV, by the Bull of 21 June 1260, recognised this foundation as a ''generale litterarum studium''. Rodrigo de Santaello, archdeacon of the cathedral and commonly known as Maese Rodrigo, began the construction of a building for a university in 1472. The Catholic Monarchs published the royal decree creating the university in 1502, and in 1505 Pope Julius II granted the Bull of authorization—this is considered the official founding of the present

In the middle of the 13th century, the Dominicans, in order to prepare missionaries for work among the Moors and Jews, had organized schools for the teaching of Arabic, Hebrew, and Greek. To cooperate in this work and to enhance the prestige of Seville, Alfonso the Wise in 1254 established in the city 'general schools' (escuelas generales) of Arabic and Latin. Pope Alexander IV, by the Bull of 21 June 1260, recognised this foundation as a ''generale litterarum studium''. Rodrigo de Santaello, archdeacon of the cathedral and commonly known as Maese Rodrigo, began the construction of a building for a university in 1472. The Catholic Monarchs published the royal decree creating the university in 1502, and in 1505 Pope Julius II granted the Bull of authorization—this is considered the official founding of the present University of Seville

The University of Seville (''Universidad de Sevilla'') is a university in Seville, Spain. Founded under the name of ''Colegio Santa María de Jesús'' in 1505, it has a present student body of over 69.200, and is one of the top-ranked universi ...

. In 1509 the college of Maese Rodrigo was finally installed in its own building, under the name of Santa María de Jesús, but its courses were not opened until 1516. The Catholic Monarchs and the pope granted the power to confer degrees in logic, philosophy, theology, and canon and civil law. The college was situated near the modern Puerta de Jerez. Only two architectural elements remain: the Late Gothic portal which since 1920 has formed part of the entrance to the Convent of Santa Clara, and the small Mudéjar chapel.

At the same time that the royal university was established, there was developed the ''Universidad de Mareantes'' (University of Sea-farers), in which body the Catholic Monarchs, by a royal decree of 1503, established the Casa de Contratación with classes for pilots and of seamen, and courses in cosmography, mathematics, military tactics, and artillery. This establishment was of incalculable importance, for it was there that the expeditions to the Indies were organised, and there that the great Spanish sailors were educated.

The ''Casa'' had a large number of cartographers and navigators, archivists, record keepers, administrators and others involved in producing and managing the Padrón Real

The Padrón Real (, ''Royal Register''), known after 2 August 1527 as the Padrón General (, ''General Register''), was the official and secret Spanish master map used as a template for the maps present on all Spanish ships during the 16th century ...

, the secret official Spanish master map used as a template for the maps present on all Spanish ships during the 16th century. It was probably a large-scale chart that hung on the wall of the old Alcázar in Seville.

The numerous official cartographers and pilots included Amerigo Vespucci, Sebastian Cabot, Alonzo de Santa Cruz

Alonzo de Santa Cruz (or Alonso, Alfonso) (1505 – 1567) was a Spanish cartographer, mapmaker, instrument maker, historian and teacher. He was born about 1505, and died in November 1567. His maps were inventoried in 1572.

Alonzo de Santa Cruz was ...

, and Juan Lopez de Velasco. In 1508 a special position was created for Vespucci, the 'pilot major' (chief of navigation), to train new pilots for ocean voyages. Vespucci, who made at least two voyages to the New World, worked at the Casa de Contratación until his death in 1512.

Important buildings of the Sevillian Golden Age

With its monopoly on theWest Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

trade, Seville saw a great influx of wealth. This wealth drew Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

artists such as Pietro Torrigiano

Pietro Torrigiano (24 November 1472 – July/August 1528) was an Italian Renaissance sculptor from Florence, who had to flee the city after breaking Michelangelo's nose. He then worked abroad, and died in prison in Spain. He was important in ...

, a classmate rival of Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was insp ...

in the garden of the Medici

The House of Medici ( , ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first began to gather prominence under Cosimo de' Medici, in the Republic of Florence during the first half of the 15th century. The family originated in the Muge ...

. Torrigiano executed magnificent sculptures at the monastery of Saint Jerome and elsewhere in Seville, as well as notable tombs and other works which brought the influence of the Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

and of humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humani ...

to Seville. French and Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

sculptors such as Roque Balduque Roque Balduque (or Roque de Balduque) (died February 1561) was a sculptor and maker of altarpieces. Born at an unknown date in Bois-le-Duc (now 's-Hertogenbosch, capital of North Brabant in the Netherlands), he is known for his work in Spain in the ...

arrived also, bringing with them a tradition of a greater realism.

Important historic buildings from this period include the

Important historic buildings from this period include the Seville Cathedral

The Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See ( es, Catedral de Santa María de la Sede), better known as Seville Cathedral, is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Seville, Andalusia, Spain. It was registered in 1987 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, along ...

, completed in 1506; after Seville was taken by the Christians (1248) in the Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

, the city's mosque had been converted to a church. This structure was badly damaged in a 1356 earthquake, and by 1401 the city began building the current cathedral, one of the largest churches in the world and an outstanding example of the Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes