History Of Portland, Oregon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the city of Portland, Oregon, began in 1843 when business partners William Overton and

The history of the city of Portland, Oregon, began in 1843 when business partners William Overton and

On March 30, 1849, Lownsdale split the Portland claim with

On March 30, 1849, Lownsdale split the Portland claim with  In December 1849,

In December 1849,

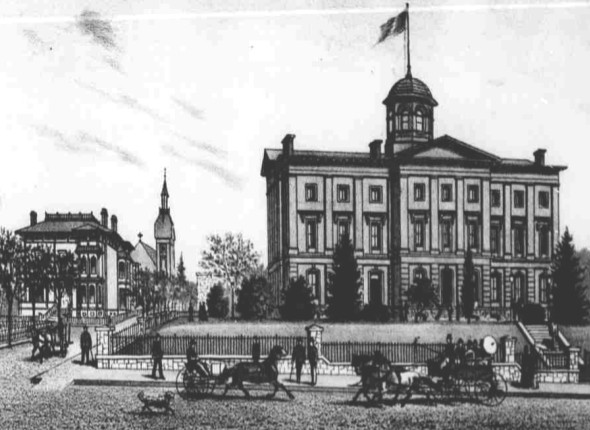

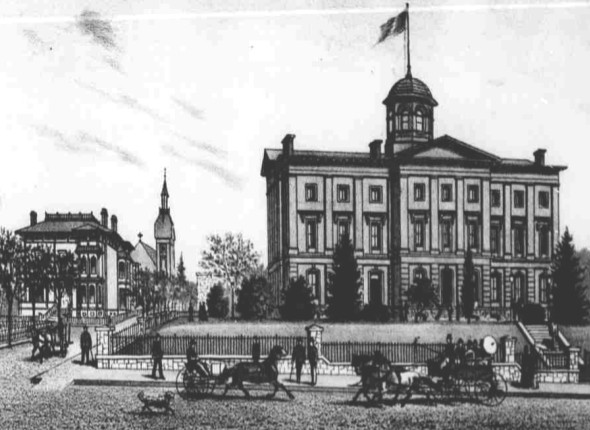

Portland as depicted in Frances Fuller Victor's ''Atlantis Arisen'' (1891).

A major fire swept through downtown in August 1873, destroying 20 blocks along the west side of the Willamette between Yamhill and Morrison. The fire caused $1.3 million in damage. In 1889, ''

Portland as depicted in Frances Fuller Victor's ''Atlantis Arisen'' (1891).

A major fire swept through downtown in August 1873, destroying 20 blocks along the west side of the Willamette between Yamhill and Morrison. The fire caused $1.3 million in damage. In 1889, ''

/ref> This merger was followed by the

In 1905, Portland was the host city of the

In 1905, Portland was the host city of the  On June 9, 1934, approximately 1,400 members of the

On June 9, 1934, approximately 1,400 members of the

Oregon bill aims to rid the shopping cart blight

'' 19 March 2007. Accessed 9 March 2008.Your guide to the next 72 hours

''

abstract

/ref> Several arts publications were founded. The Portland millennial art renaissance has been described, written about and commented on in publications such as ''

full text online

* Abbott, Carl. ''Portland in Three Centuries: The Place and the People'' (Oregon State University Press; 2011) 192 pages; scholarly histor

online

* Abbott, Carl. ''Portland : gateway to the Northwest'' (1985

online

* In Three Volumes

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

* Johnston, Robert D. ''The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland, Oregon'' (2003) * * Leeson, Fred. ''Rose City Justice: A Legal History of Portland, Oregon'' (Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1998) * *

online full text

also se

online review

* * MacColl, E. Kimbark, and Harry H. Stein. "The Economic Power of Portland's Early Merchants, 1851-1861." ''Oregon Historical Quarterly'' 89.2 (1988): 117–156. * Elma MacGibbons reminiscences of her travels in the United States starting in 1898, which were mainly in Oregon and Washington. Includes chapter "Portland, the western hub." * Merriam, Paul Gilman. "Portland, Oregon, 1840–1890: A Social and Economic History". Ph.D. dissertation. University of Oregon, Department of History, 1971. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1971. 7208574. * Mullins, William H. ''The Depression and the Urban West Coast, 1929-1933: Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland'' (2000) * * * Scott, H. W. ed. ''History of Portland, Oregon, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Prominent Citizens and Pioneers'' (D. Mason & Company, 1890) 792p

full text online

* Wong, Marie Rose. ''Sweet Cakes, Long Journey: The Chinatowns of Portland, Oregon'' (U of Washington Press, 2004

excerpt

also se

each chapter abstract and online copy

PdxHistory.comHistorical Timeline

at Portland City Auditor's Office

Wartime Portland

at Oregon Historical Society *Portland page a

Oregon History Project

(Oregon Historical Society)

at ''Willamette Week''

Transportation history

Portland Bureau of Transportation

A pictorial history of the Portland Waterfront

* {{Oregon Brief History Willamette Valley

The history of the city of Portland, Oregon, began in 1843 when business partners William Overton and

The history of the city of Portland, Oregon, began in 1843 when business partners William Overton and Asa Lovejoy

Asa Lawrence Lovejoy (March 14, 1808 – September 10, 1882) was an American pioneer and politician in the region that would become the U.S. state of Oregon. He is best remembered as a founder of the city of Portland, Oregon. He was an attorney ...

filed to claim land on the west bank of the Willamette River

The Willamette River ( ) is a major tributary of the Columbia River, accounting for 12 to 15 percent of the Columbia's flow. The Willamette's main stem is long, lying entirely in northwestern Oregon in the United States. Flowing northward ...

in Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long Oregon boundary dispute, dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been demarcat ...

. In 1845 the name of Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

*Portland, Oregon, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Oregon

*Portland, Maine, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine

*Isle of Portland, a tied island in the English Channel

Portland may also r ...

was chosen for this community by coin toss

A coin is a small object, usually round and flat, used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order to facilitate trade. They are most often issued by a ...

. February 8, 1851, the city was incorporated. Portland has continued to grow in size and population, with the 2010 census showing 583,776 residents in the city.

Early history

The land today occupied byMultnomah County, Oregon

Multnomah County is one of the Oregon counties, 36 counties in the U.S. state of Oregon. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the county's population was 815,428. Multnomah County is part of the Portland metropolitan area. The stat ...

, was inhabited for centuries by two bands of Upper Chinook Indians. The Multnomah people

The Multnomah are a tribe of Chinookan people who live in the area of Portland, Oregon, in the United States. Multnomah villages were located throughout the Portland basin and on both sides of the Columbia River. The Multnomah speak a dialect o ...

settled on and around Sauvie Island

Sauvie Island is in the U.S. state of Oregon, originally named as Wapato Island or Wappatoo Island. It is the largest island along the Columbia River, at , and one of the largest river islands in the United States. It lies approximately north ...

and the Cascades Indians settled along the Columbia Gorge

The Columbia River Gorge is a canyon of the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Up to deep, the canyon stretches for over as the river winds westward through the Cascade Range, forming the boundary between the state ...

. These groups fished and traded along the river and gathered berries, wapato and other root vegetable

Root vegetables are underground plant parts eaten by humans or animals as food. In agricultural and culinary terminology, the term applies to true roots, such as taproots and root tubers, as well as non-roots such as bulbs, corms, rhizomes, and ...

s. The nearby Tualatin Plains

The Tualatin Plains are a prairie area in central Washington County, Oregon, United States. Located around the Hillsboro and Forest Grove areas, the plains were first inhabited by the Atfalati band of the Kalapuya group of Native Americans. Euro ...

provided prime hunting grounds. Eventually, contact with Europeans resulted in the decimation of native tribes by smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

and malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

.

Founding

The site of the future city ofPortland, Oregon

Portland ( ) is the List of cities in Oregon, most populous city in the U.S. state of Oregon, located in the Pacific Northwest region. Situated close to northwest Oregon at the confluence of the Willamette River, Willamette and Columbia River, ...

, was known to American, Canadian, and British traders, trappers

Animal trapping, or simply trapping or ginning, is the use of a device to remotely catch and often kill an animal. Animals may be trapped for a variety of purposes, including for meat, fur/feathers, sport hunting, pest control, and wildlife man ...

and settler

A settler or a colonist is a person who establishes or joins a permanent presence that is separate to existing communities. The entity that a settler establishes is a Human settlement, settlement. A settler is called a pioneer if they are among ...

s of the 1830s and early 1840s as "The Clearing," a small stopping place along the west bank of the Willamette River

The Willamette River ( ) is a major tributary of the Columbia River, accounting for 12 to 15 percent of the Columbia's flow. The Willamette's main stem is long, lying entirely in northwestern Oregon in the United States. Flowing northward ...

used by travelers ''en route'' between Oregon City

Oregon City is the county seat of Clackamas County, Oregon, United States, located on the Willamette River near the southern limits of the Portland metropolitan area. As of the 2020 census, the city population was 37,572. Established in 1829 ...

and Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th-century fur trading post built in the winter of 1824–1825. It was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was ...

. As early as 1840, Massachusetts sea captain

A sea captain, ship's captain, captain, master, or shipmaster, is a high-grade licensed mariner who holds ultimate command and responsibility of a merchant vessel. The captain is responsible for the safe and efficient operation of the ship, inc ...

John Couch logged an encouraging assessment of the river's depth adjacent to The Clearing, noting its promise of accommodating large ocean-going vessels, which could not ordinarily travel up-river as far as Oregon City, the largest Oregon settlement at the time. In 1843, Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

pioneer William Overton and Boston, Massachusetts

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

lawyer Asa Lovejoy filed a land claim with Oregon's provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

that encompassed The Clearing and nearby waterfront and timber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into uniform and useful sizes (dimensional lumber), including beams and planks or boards. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, window frames). ...

land. Legend has it that Overton had prior rights to the land but lacked funds, so he agreed to split the claim with Lovejoy, who paid the 25-cent filing fee.

Bored with clearing trees and building roads, Overton sold his half of the claim to Francis W. Pettygrove

Francis William Pettygrove ( – October 5, 1887) was an American pioneer and merchant who was one of the founders of the cities of Portland, Oregon, and Port Townsend, Washington. Born in Maine, he re-located to the Oregon Country in 1843 to est ...

of Portland, Maine

Portland is the List of municipalities in Maine, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine and the county seat, seat of Cumberland County, Maine, Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 at the 2020 census. The Portland metropolit ...

, in 1845. When it came time to name their new town, Pettygrove and Lovejoy both had the same idea: to name it after his home town. They flipped a coin to decide, and Pettygrove won. On November 1, 1846, Lovejoy sold his half of the land claim to Benjamin Stark

Benjamin Stark (June 26, 1820October 10, 1898) was an American merchant and politician in Oregon. A native of Louisiana, he purchased some of the original tracts of land for the city of Portland. He later served in the Oregon House of Representat ...

, as well as his half-interest in a herd of cattle for $1,215.

Three years later, Pettygrove had lost interest in Portland and become enamored with the California Gold Rush

The California gold rush (1848–1855) began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California from the rest of the U ...

. On September 22, 1848, he sold the entire townsite, save only for 64 sold lots and two blocks each for himself and Stark, to Daniel H. Lownsdale, a tanner. Although Stark owned fully half of the townsite, Pettygrove "largely ignor dStark's interest", in part because Stark was on the east coast with no immediate plans to return to Oregon. Lownsdale paid for the site with $5,000 in leather

Leather is a strong, flexible and durable material obtained from the tanning (leather), tanning, or chemical treatment, of animal skins and hides to prevent decay. The most common leathers come from cattle, sheep, goats, equine animals, buffal ...

, which Pettygrove presumably resold in San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

for a large profit.

On March 30, 1849, Lownsdale split the Portland claim with

On March 30, 1849, Lownsdale split the Portland claim with Stephen Coffin

Stephen Coffin (1807 – 1882) was an investor, promoter, builder, and militia officer in mid-19th century Portland, Oregon, Portland in the U.S. state of Oregon. Born in Maine, he moved to Oregon City, Oregon, Oregon City in 1847, and in 1849 he ...

, who paid $6,000 for his half. By August 1849, Captain John Couch and Stark were pressuring Lownsdale and Coffin for Stark's half of the claim; Stark had been absent, but was using the claim as equity in an East Coast-California shipping business with the Sherman Brothers of New York. In December 1849,

In December 1849, William W. Chapman

William Williams Chapman (August 11, 1808October 18, 1892) was an American politician and lawyer in Oregon and Iowa. He was born and raised in Virginia. He served as a United States Attorney in Iowa when it was part of the Michigan Territory, Mi ...

bought what he believed was a third of the overall claim for $26,666, plus his provision of free legal services for the partnership. In January 1850, Lownsdale had to travel to San Francisco to negotiate on the land claim

A land claim is "the pursuit of recognized territorial ownership by a group or individual". The phrase is usually only used with respect to disputed or unresolved land claims. Some types of land claims include Aboriginal title, aboriginal land cla ...

with Stark, leaving Chapman with power of attorney

A power of attorney (POA) or letter of attorney is a written authorization to represent or act on another's behalf in private affairs (which may be financial or regarding health and welfare), business, or some other legal matter. The person auth ...

. Stark and Lownsdale came to an agreement on March 1, 1850, which gave to Stark the land north of Stark Street

Stark Street, formerly known as Baseline Road, is an east-west-running street in Portland, Oregon, in the United States. The street is named after Benjamin Stark, and is divided as Southeast Stark Street and Southwest Stark Street by the Willame ...

and about $3,000 from land already sold in this area. This settlement reduced the size of Chapman's claim by approximately 10%. Lownsdale returned to Portland in April 1850, where the terms were presented to an unwilling Chapman and Coffin, but who agreed after negotiations with Couch. While Lownsdale was gone, Chapman had given himself block 81 on the waterfront and sold all of the lots on it, and this block was included in the Stark settlement area. Couch's negotiations excluded this property from Stark's claim, allowing Chapman to retain the profits on the lot.

Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

*Portland, Oregon, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Oregon

*Portland, Maine, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine

*Isle of Portland, a tied island in the English Channel

Portland may also r ...

existed in the shadow of Oregon City, the territorial capital upstream at Willamette Falls

The Willamette Falls is a natural waterfall in the Northwestern United States, northwestern United States, located on the Willamette River between Oregon City, Oregon, Oregon City and West Linn, Oregon. The largest waterfall in the Northwest ...

. However, Portland's location at the Willamette's confluence

In geography, a confluence (also ''conflux'') occurs where two or more watercourses join to form a single channel (geography), channel. A confluence can occur in several configurations: at the point where a tributary joins a larger river (main ...

with the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

, accessible to deep-draft vessels, gave it a key advantage over the older pier

A pier is a raised structure that rises above a body of water and usually juts out from its shore, typically supported by piling, piles or column, pillars, and provides above-water access to offshore areas. Frequent pier uses include fishing, b ...

. It also triumphed over early rivals such as Milwaukie and Linnton. In its first census in 1850, the city's population was 821 and, like many frontier towns, was predominantly male, with 653 male whites, 164 female whites and four "free colored" individuals. It was already the largest settlement in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

, and while it could boast about its trading houses, hotels and even a newspaper—the ''Weekly Oregonian''—it was still very much a frontier village, derided by outsiders as "Stumptown" and "Mudtown." It was a place where "stumps from fallen firs lay scattered dangerously about Front and First Streets ... humans and animals, carts and wagons slogged through a sludge of mud and water ... sidewalks often disappeared during spring floods."

In 1850, construction of a multi-purpose "school and meeting house" was completed, a building which served as a church, schoolhouse, courthouse

A courthouse or court house is a structure which houses judicial functions for a governmental entity such as a state, region, province, county, prefecture, regency, or similar governmental unit. A courthouse is home to one or more courtrooms, ...

, and place for public meetings. This was Portland's first schoolhouse; by 1873 Portland boasted "twenty public and private schools and academies of a high order, and nearly the same number of churches."

The first firefighting

Firefighting is a profession aimed at controlling and extinguishing fire. A person who engages in firefighting is known as a firefighter or fireman. Firefighters typically undergo a high degree of technical training. This involves structural fir ...

service was established in the early 1850s, with the volunteer Pioneer Fire Engine Company. In 1854, the city council

A municipal council is the legislative body of a municipality or local government area. Depending on the location and classification of the municipality it may be known as a city council, town council, town board, community council, borough counc ...

voted to form the Portland Fire Department, and following an 1857 reorganization it encompassed three engine companies and 157 volunteer firemen.

Late 19th century

Portland as depicted in Frances Fuller Victor's ''Atlantis Arisen'' (1891).

A major fire swept through downtown in August 1873, destroying 20 blocks along the west side of the Willamette between Yamhill and Morrison. The fire caused $1.3 million in damage. In 1889, ''

Portland as depicted in Frances Fuller Victor's ''Atlantis Arisen'' (1891).

A major fire swept through downtown in August 1873, destroying 20 blocks along the west side of the Willamette between Yamhill and Morrison. The fire caused $1.3 million in damage. In 1889, ''The Oregonian

''The Oregonian'' is a daily newspaper based in Portland, Oregon, United States, owned by Advance Publications. It is the oldest continuously published newspaper on the West Coast of the United States, U.S. West Coast, founded as a weekly by Tho ...

'' called Portland "the most filthy city in the Northern States", due to the unsanitary sewers and gutters. The '' West Shore'' reported "The new sidewalks put down this year are a disgrace to a Russian village."

The first Morrison Street Bridge opened in 1887 and was the first bridge across the Willamette River in Portland.Portland was the major port in the Pacific Northwest for much of the 19th century, until the 1890s, when direct railroad access between the deepwater harbor in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Washington and in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. With a population of 780,995 in 2024, it is the 18th-most populous city in the United States. The city is the cou ...

and points east, by way of Stampede Pass

Stampede Pass (elevation ) is a mountain pass in the Pacific Northwest, northwest United States, through the Cascade Range in Washington (state), Washington. Southeast of Seattle and east of Tacoma, Washington, Tacoma, its importance to transport ...

, was built. Goods could then be transported from the northwest coast to inland cities without the need to navigate the dangerous bar at the mouth of the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

.

The city merged with Albina and East Portland in 1891. This made Portland the 41st largest city in the country, with approximately 70,000 residents.Portland Timeline: 1843 to 1901, City of Portland Auditor's Office/ref> This merger was followed by the

annexation

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held t ...

of the neighboring city of Sellwood in 1893.

In 1894, the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

saw one of its worst-ever floods, reaching a high-water mark of 33.5 feet in Portland.

20th century

In 1905, Portland was the host city of the

In 1905, Portland was the host city of the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition

The Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, commonly also known as the Lewis and Clark Exposition, and officially known as the Lewis and Clark Centennial and American Pacific Exposition and Oriental Fair, was a worldwide World's fair, exposition h ...

, a world's fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition, is a large global exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specific site for a perio ...

. This event

increased recognition of the city, which contributed to a doubling of the population of Portland, from 90,426 in 1900 to 207,214 in 1910.

In 1911, the Willamette River flooded much of Downtown Portland

Downtown Portland is the central business district of Portland, Oregon, United States. It is on the west bank of the Willamette River in the northeastern corner of the southwest section of the city and where most of the city's high-rise buildi ...

, though not much damage is noted.

In 1912 the city's 52 distinctive bronze temperance fountain

A temperance fountain was a fountain that was set up, usually by a private benefactor, to encourage temperance, and to make abstinence from beer possible by the provision of clean, safe, and free water. The temperance societies had no real alte ...

s known locally as " Benson bubblers" were installed around the downtown area by logging magnate

The term magnate, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

Simon Benson

Simon Benson (born Simen Bergersen Klæve, September 9, 1851 – August 5, 1942) was a Norwegian-born American businessman and philanthropist who was active in the city of Portland, Oregon.

Early life

Simon Benson was born Simen Bergersen Kl� ...

.

In 1915, the city merged with Linnton and St. Johns.

July 1913 saw a free speech fight

Free speech fights are struggles over free speech, and especially those struggles which involved the Industrial Workers of the World and their attempts to gain awareness for labor issues by organizing workers and urging them to use their collective ...

when, during a strike

Strike may refer to:

People

*Strike (surname)

* Hobart Huson, author of several drug related books

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

* Airstrike, ...

by women workers at the Oregon Packing Company, Mayor Henry Albee declared street speaking illegal, with an exception made for religious speech. This declaration was intended to stop public speeches by the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago, United States in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with indu ...

in support of the strikers.

On June 9, 1934, approximately 1,400 members of the

On June 9, 1934, approximately 1,400 members of the International Longshoremen's Association

The International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) is a North American labor union representing longshore workers along the East Coast of the United States and Canada, the Gulf Coast, the Great Lakes, Puerto Rico, and inland waterways; on the W ...

(ILA) participated in the West Coast waterfront strike, which shut down shipping in every port along the West Coast.''Dock Strike: History of the 1934 Waterfront Strike in Portland, Oregon'' by Roger Buchanan (1975) The demands of the ILA were: recognition of the union; wage increases from 85 cents to $1.00 per hour straight time and from $1.25 to $1.50 per hour overtime

Overtime is the amount of time someone works beyond normal working hours. The term is also used for the pay received for this time. Normal hours may be determined in several ways:

*by custom (what is considered healthy or reasonable by society) ...

; a six-hour workday and 30-hour work week; and a closed shop

A pre-entry closed shop (or simply closed shop) is a form of union security agreement under which the employer agrees to hire union members only, and employees must remain members of the union at all times to remain employed. This is different fr ...

with the union in control of hiring. They were also frustrated that shipping subsidies

A subsidy, subvention or government incentive is a type of government expenditure for individuals and households, as well as businesses with the aim of stabilizing the economy. It ensures that individuals and households are viable by having acce ...

from the government, in place since industry distress in the 1920s, were leading to larger profits for the shipping companies that weren't passed down to the workers. There were numerous incidents of violence between strikers and police, including strikers storming the ''Admiral Evans'', which was being used as a hotel for strikebreaker

A strikebreaker (sometimes pejoratively called a scab, blackleg, bootlicker, blackguard or knobstick) is a person who works despite an ongoing strike. Strikebreakers may be current employees ( union members or not), or new hires to keep the orga ...

s; police shooting four strikers at Terminal 4 in St. Johns; and special police shooting at Senator Robert Wagner

Robert John Wagner Jr. (born February 10, 1930) is an American actor. He is known for starring in the television shows ''It Takes a Thief (1968 TV series), It Takes a Thief'' (1968–1970), ''Switch (American TV series), Switch'' (1975–1978), ...

of New York as he inspected the site of the previous shooting. The longshoremen resumed work on July 31, 1934, after voting to arbitrate

Arbitration is a formal method of dispute resolution involving a third party neutral who makes a binding decision. The third party neutral (the 'arbitrator', 'arbiter' or 'arbitral tribunal') renders the decision in the form of an 'arbitrati ...

. The arbitration decision was handed down on October 12, 1934, awarding the strikers with recognition of the ILA; higher pay of 95 cents per hour straight time and $1.40 per hour overtime, retroactive to the return to work on July 31; six-hour workdays and 30-hour workweeks, and a union hiring hall

In organized labor, a hiring hall is an organization, usually under the auspices of a trade union, labor union, which has the responsibility of furnishing new recruits for employers who have a collective bargaining agreement with the union. It ma ...

managed jointly by the union and management – though the union selected the dispatcher – in every port along the entire West Coast.

World War II

In 1940, Portland was on the brink of an economic and population boom, fueled by over $2 billion spent by theU.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a bicameral legislature, including a lower body, the U.S. House of Representatives, and an upper body, the U.S. Senate. They both ...

on expanding the Bonneville Power Administration

The Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) is an American federal agency operating in the Pacific Northwest. BPA was created by an act of United States Congress, Congress in 1937 to market electric power from the Bonneville Dam located on the Col ...

, the need to produce materiel

Materiel or matériel (; ) is supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commerce, commercial supply chain management, supply chain context.

Military

In a military context, ...

for Great Britain's increased preparations for war, as well as to meet the needs of the U.S. home front and the rapidly expanding American Navy.

The growth was led by Henry J. Kaiser

Henry John Kaiser (May 9, 1882 – August 24, 1967) was an American industrialist who became known for his shipbuilding and construction projects, then later for his involvement in fostering modern American health care. Prior to World War II, ...

, whose company had been the prime contractor in the construction of two Columbia River dam

A dam is a barrier that stops or restricts the flow of surface water or underground streams. Reservoirs created by dams not only suppress floods but also provide water for activities such as irrigation, human consumption, industrial use, aqua ...

s. In 1941, Kaiser Shipyards

The Kaiser Shipyards were seven major shipbuilding yards located on the West Coast of the United States, United States west coast during World War II. Kaiser ranked 20th among U.S. corporations in the value of wartime production contracts. The ...

received federal contracts to build Liberty ship

Liberty ships were a ship class, class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Although British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost cons ...

s and aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

escorts; he chose Portland as one of the sites, and built two shipyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are shipbuilding, built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Compared to shipyards, which are sometimes m ...

s along the Willamette River, and a third in nearby Vancouver

Vancouver is a major city in Western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the cit ...

; the 150,000 workers he recruited to staff these shipyards play a major role in the growth of Portland, which added 160,000 residents during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

By war's end, Portland had a population of 359,000, and an additional 100,000 people lived and/or worked in nearby cities such as Vanport, Oregon City

Oregon City is the county seat of Clackamas County, Oregon, United States, located on the Willamette River near the southern limits of the Portland metropolitan area. As of the 2020 census, the city population was 37,572. Established in 1829 ...

, and Troutdale.

The war jobs attracted large numbers of African-Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

into the small existing community—the numbers quadrupled. The newcomers became permanent residents, building up black political influence, strengthening civil rights organizations

Civil may refer to:

*Civility, orderly behavior and politeness

*Civic virtue, the cultivation of habits important for the success of a society

*Civil (journalism)

''The Colorado Sun'' is an online news outlet based in Denver, Colorado. It lau ...

such as the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

calling for antidiscrimination legislation. On the negative side, racial tensions increased, both black and white residential areas deteriorated from overcrowding, and inside the black community there were angry words between "old settlers" and recent arrivals vying for leadership in the black communities.

In 1942, Japanese Americans

are Americans of Japanese ancestry. Japanese Americans were among the three largest Asian Americans, Asian American ethnic communities during the 20th century; but, according to the 2000 United States census, 2000 census, they have declined in ...

, who primarily resided in Japantown

is a common name for Japanese communities in cities and towns outside Japan. Alternatively, a Japantown may be called J-town, Little Tokyo or , the first two being common names for Japantown, San Francisco, Japantown, San Jose and Little ...

, were moved to the Portland Assembly Center

The Portland Expo Center, officially the Portland Metropolitan Exposition Center, is a convention center located in the Kenton, Portland, Oregon, Kenton neighborhood of Portland, Oregon, United States. Opened in the early 1920s as a livestock exhi ...

, a temporary internment center on the site of the Portland Expo Center

The Portland Expo Center, officially the Portland Metropolitan Exposition Center, is a convention center located in the Kenton neighborhood of Portland, Oregon, United States. Opened in the early 1920s as a livestock exhibition and auction facili ...

. These individuals were eventually transported to internment camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simp ...

. The majority of people complied with internment

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without Criminal charge, charges or Indictment, intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects ...

. Japantown became Old Town

In a city or town, the old town is its historic or original core. Although the city is usually larger in its present form, many cities have redesignated this part of the city to commemorate its origins. In some cases, newer developments on t ...

and its Japanese population never returned to meaningful numbers.

Postwar

As part of the1948 Columbia River flood

The 1948 Columbia River flood (or Vanport Flood) was a regional flood that occurred in the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada. Large portions of the Columbia River watershed were impacted, including the Portland area, Eastern Wash ...

s, Vanport, a small wartime public housing

Public housing, also known as social housing, refers to Subsidized housing, subsidized or affordable housing provided in buildings that are usually owned and managed by local government, central government, nonprofit organizations or a ...

community, primarily inhabited by employees of Kaiser Shipyards, was flooded and completely destroyed. The community was not rebuilt. Despite being short-lived, Vanport's legacy is still seen today. Having a 40% Black population, Vanport led to the integration of Black people by Portland and the rest of Oregon. The Vanport Extension Center, a small college built to help veterans of World War II, moved to Downtown and became what is now Portland State University

Portland State University (PSU) is a public research university in Portland, Oregon, United States. It was founded in 1946 as a post-secondary educational institution for World War II veterans. It evolved into a four-year college over the next ...

.

The 1940s and 1950s also saw an extensive network of organized crime

Organized crime is a category of transnational organized crime, transnational, national, or local group of centralized enterprises run to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally thought of as a f ...

, largely dominated by Jim Elkins. The McClellan Commission determined in the late 1950s that Portland not only had a local crime problem but also a situation that had serious national ramifications. In 1956 ''The Oregonian

''The Oregonian'' is a daily newspaper based in Portland, Oregon, United States, owned by Advance Publications. It is the oldest continuously published newspaper on the West Coast of the United States, U.S. West Coast, founded as a weekly by Tho ...

'' reporters determined that corrupt Teamsters

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) is a trade union, labor union in the United States and Canada. Formed in 1903 by the merger of the Team Drivers International Union and the Teamsters National Union, the union now represents a di ...

officials were plotting to take over the city's vice

A vice is a practice, behaviour, Habit (psychology), habit or item generally considered morally wrong in the associated society. In more minor usage, vice can refer to a fault, a negative character trait, a defect, an infirmity, or a bad or unhe ...

rackets.

Interstate projects

As early as 1943,highway

A highway is any public or private road or other public way on land. It includes not just major roads, but also other public roads and rights of way. In the United States, it is also used as an equivalent term to controlled-access highway, or ...

planner Robert Moses

Robert Moses (December 18, 1888 – July 29, 1981) was an American urban planner and public official who worked in the New York metropolitan area during the early to mid-20th century. Moses is regarded as one of the most powerful and influentia ...

was commissioned by the city to create a system of improvements for after the World War II. a downtown loop consisting of what is now I-405 and an eastside freeway

A controlled-access highway is a type of highway that has been designed for high-speed vehicular traffic, with all traffic flow—ingress and egress—regulated. Common English terms are freeway, motorway, and expressway. Other similar terms ...

(now I-5) were part of this plan. After debating the downtown route, both freeways were built and completed in 1966 (I-5) and 1969 (I-405), and included the construction of the Fremont Bridge and Marquam Bridge

The Marquam Bridge is a double-deck, cantilever bridge, steel-truss cantilever bridge that carries Interstate 5 traffic across the Willamette River from south of downtown Portland, Oregon, on the west side to the industrial area of inner South ...

. The eastside freeway was so hated that in a formal complaint, the Portland Arts Commission described it as "so gross, so lacking in grace, so utterly inconsistent with any concept of aesthetics".

The construction of I-405 displaced approximately 1,100 households and caused the demolition of hundreds of buildings. An expansion project of I-405, set to be called I-505, was cancelled in 1978 due to extensive public outcry.

In 1950, Harbor Drive

Harbor Drive is a short roadway in Portland, Oregon, spanning a total length of , which primarily functions as a ramp to and from Interstate 5. It was once much longer, running along the western edge of the Willamette River in the downtown ar ...

, part of Oregon Route 99W

Oregon Route 99W is a state-numbered route in Oregon, United States, that runs from OR 99 and OR 99E in Junction City north to I-5 in southwestern Portland. Some signage continues it north to US 26 near downtown, but most signage agrees wi ...

, was reconstructed into a controlled-access freeway. It was signed as I-5 for a short time until the completion of the Marquam Bridge in 1966. In 1974, after months of protests which included blocking the highway, and with support from Governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

Tom McCall

Thomas Lawson McCall (March 22, 1913 January 8, 1983) was an American, politician and journalist in the state of Oregon, serving as the state's thirtieth governor from 1967 to 1975. A progressive Republican, he was known as a staunch environme ...

, the highway, as well as buildings between the highway and Front Avenue, were demolished.Lloyd, Mike (May 23, 1974). "Asphalt strip to disappear from Portland riverfront". ''The Oregonian

''The Oregonian'' is a daily newspaper based in Portland, Oregon, United States, owned by Advance Publications. It is the oldest continuously published newspaper on the West Coast of the United States, U.S. West Coast, founded as a weekly by Tho ...

'', p. 29. The highway and most of the former buildings' sites were turned into Tom McCall Waterfront Park

Governor Tom McCall Waterfront Park is a park located in downtown Portland, Oregon, along the Willamette River. After the 1974 removal of Harbor Drive, a major milestone in the freeway removal movement, the park was opened to the public in 19 ...

, and Front Avenue was widened to become a boulevard

A boulevard is a type of broad avenue planted with rows of trees, or in parts of North America, any urban highway or wide road in a commercial district.

In Europe, boulevards were originally circumferential roads following the line of former ...

. In 1996, Front Avenue was renamed Naito Parkway after businessman and civic leader Bill Naito

William Sumio Naito (September 16, 1925 – May 8, 1996) was an American businessman, civic leader and philanthropist in Portland, Oregon, U.S. He was an enthusiastic advocate for investment in downtown Portland, both private and public, and ...

.Stewart, Bill (June 21, 1996). "City picks Front Ave. as memorial to Naito". ''The Oregonian'', p. 1.

Late 20th century

Public transport

Public transport (also known as public transit, mass transit, or simply transit) are forms of transport available to the general public. It typically uses a fixed schedule, route and charges a fixed fare. There is no rigid definition of whic ...

ation in Portland transitioned from private to public ownership

State ownership, also called public ownership or government ownership, is the ownership of an industry, asset, property, or enterprise by the national government of a country or state, or a public body representing a community, as opposed t ...

in 1969–70, as the private companies found it increasingly difficult to make a profit and were on the verge of bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the deb ...

. A new regional government agency, the Tri-County Metropolitan Transportation District (Tri-Met), replaced Rose City Transit

The Rose City Transit Company (RCT, or RCTC) was a private company that operated most mass transit service in the city of Portland, Oregon, from 1956 to 1969. It operated only within the city proper. Transit services connecting downtown Portland ...

in 1969 and the "Blue Bus" lines—connecting Portland with its suburbs—in 1970.

In early 1996, the Portland area saw a major flood. The Willamette River crested at , some above flood stage, and came within inches of flowing over the seawall

A seawall (or sea wall) is a form of coastal defense constructed where the sea, and associated coastal processes, impact directly upon the landforms of the coast. The purpose of a seawall is to protect areas of human habitation, conservation, ...

. The Oregon National Guard

The Oregon Military Department is an agency of the Government of Oregon, government of the U.S. state of Oregon, which oversees the armed forces of the state of Oregon. Under the authority and direction of the Governor of Oregon, governor as ...

and civilian volunteers participated in a massive sand-bagging effort which was maintained until the floodwaters retreated. Five rivers in Oregon crested at all-time highs.

21st century

From 2000 to 2014, Portland experienced a significant growth of over 90,000 people between the years 2000 and 2014. Between 2001 and 2012, Portland'sgross domestic product

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the total market value of all the final goods and services produced and rendered in a specific time period by a country or countries. GDP is often used to measure the economic performanc ...

per person grew by fifty percent, more than any other city in the country. and it was second in the country for attracting and retaining the highest number of college-educated people in the United States.

Portland became known throughout the early 2000s for its unique culture and attractiveness to young people. "Keep Portland Weird

"Keep Portland Weird" is a popular slogan that appears on bumper stickers, signs, and public buildings throughout Portland, Oregon and its surrounding metro area. It originated from the " Keep Austin Weird" slogan and was originally intended to p ...

" became an unofficial slogan and is popularized by a large mural

A mural is any piece of Graphic arts, graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word ''mural'' ...

in Old Town Chinatown

Old Town Chinatown is the official Chinatown of the Northwest Portland, northwest section of Portland, Oregon, Portland, Oregon, United States. The Willamette River forms its eastern boundary, separating it from the Lloyd District, Portland, Oreg ...

and the bumper sticker

A bumper sticker is an adhesive label or sticker designed to be attached to the rear of a car or truck, often on the bumper. They are commonly sized at around and are typically made of PVC.

Bumper stickers serve various purposes, including p ...

s replicating the mural. Portland has embraced this weirdness by hosting many odd events including the World Naked Bike Ride

The World Naked Bike Ride (WNBR) is an international clothing-optional bike ride in which participants plan, meet and ride together ''en masse'' on human-powered transport (the vast majority on bicycles, but some on skateboards and inline skates ...

and the Portland Urban Idiotarod, a shopping cart

A shopping cart (American English), trolley (British English, Australian English), or buggy (Southern American English, Appalachian English), also known by a variety of #Name, other names, is a wheeled cart supplied by a Retail#Types of ret ...

race where participants wear absurd costumes and often doubles as a bar crawl

A pub crawl (sometimes called a bar tour, bar crawl or bar-hopping) is the act of visiting multiple pubs or bars in a single session.

Background

Many European cities have public pub crawls that serve as social gatherings for local expatriates a ...

.Tewksbury, Drew, ''.'' Los Angeles CityBeat, 5 April 2007. Accessed 9 March 2008.Associated Press, Oregon bill aims to rid the shopping cart blight

'' 19 March 2007. Accessed 9 March 2008.Your guide to the next 72 hours

''

The Portland Tribune

The ''Portland Tribune'' is a weekly newspaper published every Wednesday in Portland, Oregon, United States. It is part of the Pamplin Media Group, which publishes a number of community newspapers in the Portland metropolitan area. Launched in 2 ...

, ''4 March 2005. Accessed 9 March 2008. Portland is also home to various strange establishments including the 24 Hour Church of Elvis, the TARDIS Room, and the Peculiarium.

In the early 2000s, Portland became home to various street performers

Street performance or busking is the act of performing in public places for gratuities. In many countries, the rewards are generally in the form of money but other gratuities such as food, drink or gifts may be given. Street performance is pr ...

. Many of these performers embrace Portland's "weirdness" including the Unipiper

The Unipiper (born Brian Kidd; April 29, 1983) is a Portland, Oregon unicyclist, street performer, bagpiper and internet celebrity.

Life and career

Brian Kidd moved to Portland, Oregon, from North Carolina in 2007. ''The Oregonian'' newspaper ...

, a unicycling

A unicycle is a vehicle that touches the ground with only one wheel. The most common variation has a bicycle frame, frame with a bicycle saddle, saddle, and has a human-powered vehicle, pedal-driven direct-drive mechanism, direct-drive. A two spe ...

bagpiper who wears a Darth Vader

Darth Vader () is a fictional character in the ''Star Wars'' franchise. He was first introduced in the original film trilogy as the primary antagonist and one of the leaders of the Galactic Empire. He has become one of the most iconic villain ...

mask, and Working Kirk Reeves, a trumpet player

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard B o ...

and juggler

Juggling is a physical skill, performed by a juggler, involving the manipulation of objects for recreation, entertainment, art or sport. The most recognizable form of juggling is toss juggling. Juggling can be the manipulation of one object o ...

known for his crisp white suit and Mickey Mouse

Mickey Mouse is an American cartoon character co-created in 1928 by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks. The longtime icon and mascot of the Walt Disney Company, Mickey is an anthropomorphic mouse who typically wears red shorts, large shoes, and white ...

hat.

In 2003, Portland's longtime nickname

A nickname, in some circumstances also known as a sobriquet, or informally a "moniker", is an informal substitute for the proper name of a person, place, or thing, used to express affection, playfulness, contempt, or a particular character trait ...

"The City of Roses" (or "Rose City") was made official by the City Council.Stern, Henry (June 19, 2003). "Name comes up roses for P-town: City Council sees no thorns in picking 'City of Roses' as Portland's moniker". ''The Oregonian''

Civil unrest

From May 28, 2020 (themurder of George Floyd

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black American man, was murdered in Minneapolis by Derek Chauvin, a 44-year-old White police officer. Floyd had been arrested after a store clerk reported that he made a purchase using a c ...

) until spring 2021, Portland had daily protests

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration, or remonstrance) is a public act of objection, disapproval or dissent against political advantage. Protests can be thought of as acts of cooperation in which numerous people cooperate ...

about Floyd's killing, police violence

Police brutality is the excessive and unwarranted use of force by law enforcement against an individual or a group. It is an extreme form of police misconduct and is a civil rights violation. Police brutality includes, but is not limited to, ...

and racial injustice

Social inequality occurs when resources within a society are distributed unevenly, often as a result of inequitable allocation practices that create distinct unequal patterns based on socially defined categories of people. Differences in acce ...

. Many of these protests turned violent and led to looting

Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, typically in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war, natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective), or rioting. ...

, vandalism

Vandalism is the action involving deliberate destruction of or damage to public or private property.

The term includes property damage, such as graffiti and defacement directed towards any property without permission of the owner. The t ...

, and assault. In one case, a protestor was killed by an opposing one. Millions of dollars were lost by local businesses from theft and vandalism.

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

deployed multiple groups of federal officers to assist locally based Federal Protective Service Federal Protective Service may refer to:

*Federal Protective Service (United States), a U.S. security police force responsible for the security of buildings owned by the U.S. federal government

*Federal Protective Service (Russia)

The Federal G ...

officers in guarding federal property as the Mark O. Hatfield United States Courthouse and the Edith Green – Wendell Wyatt Federal Building were primary targets of the vandalism and rioting. Temporary fences and boards are up around the two federal buildings and the Multnomah County Justice Center

The Multnomah County Justice Center, or simply Justice Center, is a building located at 1120 Southwest 3rd Avenue in Portland, Oregon, United States. The building was designed by ZGF Architects. It is adjacent to Plaza Blocks, Lownsdale Square in ...

as of February 2024.

On July 22, Mayor Ted Wheeler

Edward Tevis Wheeler (born August 31, 1962) is an American politician and businessman who served as the 53rd mayor of Portland, Oregon, from 2017 to 2025. A moderate member of the Democratic Party, Wheeler served as the state treasurer of Ore ...

attended one of the protests and was tear-gassed by federal officers.

These riots also led to the vandalism and removal of many of Portland's statues. Of the six statues removed, only one (Thompson Elk Fountain

''Thompson Elk Fountain'', also known as the David P. Thompson Fountain,. David P. Thompson Monument, Elk Fountain, the Thompson Elk, or simply ''Elk'', was a historic fountain and bronze sculpture by American artist Roland Hinton Perry. The foun ...

) was initially planned to be replaced. In 2024, the city announced plans to put back the statues of George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

, Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

. The statue of Harvey W. Scott and ''The Promised Land'' (which depicts Oregon pioneers

Oregon ( , ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington, while the Snake River delineates much ...

), will be sold or donated. Additionally, a statue of York

York is a cathedral city in North Yorkshire, England, with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss. It has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a Yor ...

, a slave on the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gro ...

, will be commissioned.

New government

In the November 2022 election, Portland residents voted to change the city's form of government. Portland at the time was the only major city in the country to operate under a city commission form of government. This included a five-member board, including themayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a Municipal corporation, municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilitie ...

, who each ran various bureaus of the city. Under the new form of government, the mayor is no longer a part of the city council and the city council has twelve districted seats with three council members each representing one of four districts. Additionally, elections use a single transferable vote

The single transferable vote (STV) or proportional-ranked choice voting (P-RCV) is a multi-winner electoral system in which each voter casts a single vote in the form of a ranked ballot. Voters have the option to rank candidates, and their vot ...

system as opposed to a first-past-the-post

First-past-the-post (FPTP)—also called choose-one, first-preference plurality (FPP), or simply plurality—is a single-winner voting rule. Voters mark one candidate as their favorite, or First-preference votes, first-preference, and the cand ...

system. The first election for this new form of government was in 2024

The year saw the list of ongoing armed conflicts, continuation of major armed conflicts, including the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Myanmar civil war (2021–present), Myanmar civil war, the Sudanese civil war (2023–present), Sudane ...

.

Cultural history

Whilevisual arts

The visual arts are art forms such as painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, ceramics (art), ceramics, photography, video, image, filmmaking, design, crafts, and architecture. Many artistic disciplines such as performing arts, conceptual a ...

had always been important in the Pacific Northwest, the mid-1990s saw a dramatic rise in the number of artists, independent galleries, site-specific shows and public discourse about the arts.Ann Markusen and Amanda Johnson, "Artists’ Centers: Evolution and Impact on Careers, Neighborhoods and Economies," (Project on Regional and Industrial Economics, Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota, 2006)abstract

/ref> Several arts publications were founded. The Portland millennial art renaissance has been described, written about and commented on in publications such as ''

ARTnews

''ARTnews'' is an American art magazine, based in New York City. It covers visual arts from ancient to contemporary times. It is the oldest and most widely distributed art magazine in the world. ''ARTnews'' has a readership of 180,000 in 124 co ...

'', ''Art Papers

''ART PAPERS'' is an Atlanta-based bimonthly art magazine and non-profit organization dedicated to the examination of art and culture in the world today. Its mission is to provide an independent and accessible forum for the exchange of perspect ...

'', '' Art in America'', ''Modern Painters'' and ''Artforum

''Artforum'' is an international monthly magazine specializing in contemporary art. The magazine is distinguished from other magazines by its unique 10½ × 10½ inch square format, with each cover often devoted to the work of an artist. Notably ...

'' and discussed on CNN

Cable News Network (CNN) is a multinational news organization operating, most notably, a website and a TV channel headquartered in Atlanta. Founded in 1980 by American media proprietor Ted Turner and Reese Schonfeld as a 24-hour cable ne ...

.''Portland?'' by Aaron Brown (2004) https://transcripts.cnn.com/show/asb/date/2004-09-28/segment/00 The ''Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' (''WSJ''), also referred to simply as the ''Journal,'' is an American newspaper based in New York City. The newspaper provides extensive coverage of news, especially business and finance. It operates on a subscriptio ...

'' Peter Plagens

Peter Plagens (born 1941) is an American artist, art critic, and novelist based in New York City.Online Archive of CaliforniaPeter Plagens papers, 1938-2014 Retrieved January 18, 2018.Smith, Roberta''The New York Times'', February 7, 2018. Retrie ...

noted the vibrancy of Portland's alternative art spaces.''Our Next Art Capital, Portland?'' by Peter Plagens (2012) http://www.online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303916904577378300036157294.html

See also

* James B. Stephens * James C. Hawthorne * A Day Called 'X' *Columbus Day Storm of 1962

The Columbus Day storm of 1962 (also known as the big blow of 1962, and originally in Canada as Typhoon Freda) was a Pacific Northwest windstorm that struck the West Coast of Canada and the Pacific Northwest coast of the United States on Octobe ...

*Mount Hood Freeway

The Mount Hood Freeway is a partially constructed but never to be completed freeway alignment of U.S. Route 26 and Interstate 80N (now Interstate 84), which would have run through southeast Portland, Oregon

Portland ( ) is the List of ...

* Mayors of Portland

* Timeline of Portland, Oregon

* History of Chinese Americans in Portland, Oregon

*African Americans in Oregon

African Americans in Oregon or Black Oregonians are residents of the state of Oregon who are of African American ancestry. In 2017, there were an estimated 91,000 African Americans in Oregon.

History

Black people likely began arriving in Oreg ...

*Protests in Portland, Oregon

Portland, Oregon has an extended history of street activism and has seen many notable protests.

History

Portland's first organized demonstration was held in 1857.

19th century

Women organized in the late 19th century around several issues. T ...

*COVID-19 pandemic in Portland, Oregon

The COVID-19 pandemic was confirmed to have reached Portland in the U.S. state of Oregon on February 28, 2020.

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic is an ongoing pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respirato ...

References

Further reading

*full text online

* Abbott, Carl. ''Portland in Three Centuries: The Place and the People'' (Oregon State University Press; 2011) 192 pages; scholarly histor

online

* Abbott, Carl. ''Portland : gateway to the Northwest'' (1985

online

* In Three Volumes

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

* Johnston, Robert D. ''The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland, Oregon'' (2003) * * Leeson, Fred. ''Rose City Justice: A Legal History of Portland, Oregon'' (Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1998) * *

online full text

also se

online review

* * MacColl, E. Kimbark, and Harry H. Stein. "The Economic Power of Portland's Early Merchants, 1851-1861." ''Oregon Historical Quarterly'' 89.2 (1988): 117–156. * Elma MacGibbons reminiscences of her travels in the United States starting in 1898, which were mainly in Oregon and Washington. Includes chapter "Portland, the western hub." * Merriam, Paul Gilman. "Portland, Oregon, 1840–1890: A Social and Economic History". Ph.D. dissertation. University of Oregon, Department of History, 1971. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1971. 7208574. * Mullins, William H. ''The Depression and the Urban West Coast, 1929-1933: Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland'' (2000) * * * Scott, H. W. ed. ''History of Portland, Oregon, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Prominent Citizens and Pioneers'' (D. Mason & Company, 1890) 792p

full text online

* Wong, Marie Rose. ''Sweet Cakes, Long Journey: The Chinatowns of Portland, Oregon'' (U of Washington Press, 2004

excerpt

also se

each chapter abstract and online copy

External links

*Postcards and snaps from the past aPdxHistory.com

at Portland City Auditor's Office

Wartime Portland

at Oregon Historical Society *Portland page a

Oregon History Project

(Oregon Historical Society)

at ''Willamette Week''

Transportation history

Portland Bureau of Transportation

A pictorial history of the Portland Waterfront

* {{Oregon Brief History Willamette Valley

Portland, Oregon

Portland ( ) is the List of cities in Oregon, most populous city in the U.S. state of Oregon, located in the Pacific Northwest region. Situated close to northwest Oregon at the confluence of the Willamette River, Willamette and Columbia River, ...