The early modern era of

Polish history

The history of Poland spans over a thousand years, from Lechites, medieval tribes, Christianization of Poland, Christianization and Kingdom of Poland, monarchy; through Polish Golden Age, Poland's Golden Age, Polonization, expansionism and be ...

follows the

Late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

. Historians use the term ''

early modern

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

'' to refer to

the period beginning in approximately 1500 AD and lasting until around the

Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

in 1800 AD.

The ''

Nihil novi

''Nihil novi nisi commune consensu'' ("Nothing new without the Consent of the governed, common consent") is the original Latin title of a 1505 Statute, act or constitution adopted by the Poland, Polish ''Sejm of the Kingdom of Poland, Sejm'' (par ...

'' act adopted by the

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Polish people, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

* Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin ...

diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

in 1505 transferred

legislative power

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the legal authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial powers o ...

from the

king

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

to the diet. This event marked the beginning of the period known as the "Nobles' Democracy" () or "Nobles' Commonwealth" (). The

state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

was ruled by the "free and equal" Polish nobility or ''

szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

'', albeit in intense, and at times destabilizing, competition with the

Jagiellon

The Jagiellonian ( ) or Jagellonian dynasty ( ; ; ), otherwise the Jagiellon dynasty (), the House of Jagiellon (), or simply the Jagiellons (; ; ), was the name assumed by a cadet branch of the Lithuanian ducal dynasty of Gediminids upon recep ...

and then

elective kings.

The

Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin (; ) was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, and created a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. It replaced the personal union of the Crown of the Kingd ...

of 1569 constituted the

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

, a more closely merged continuation of the already existing

personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

of the

Crown of Poland

The Crown of the Kingdom of Poland (; ) was a political and legal concept formed in the 14th century in the Kingdom of Poland, assuming unity, indivisibility and continuity of the state. Under this idea, the state was no longer seen as the pa ...

and the

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a sovereign state in northeastern Europe that existed from the 13th century, succeeding the Kingdom of Lithuania, to the late 18th century, when the territory was suppressed during the 1795 Partitions of Poland, ...

. The beginning of the Commonwealth coincided with the period of Poland's greatest territorial expansion, power, civilizational advancement and prosperity. The Polish–Lithuanian state had become an influential player in Europe and a vital cultural entity,

spreading Western culture

Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, Western society, or simply the West, refers to the Cultural heritage, internally diverse culture of the Western world. The term "Western" encompas ...

eastward.

Following the

Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

gains accompanied by religious toleration, the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

embarked on an ideological counter-offensive and

Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

claimed many converts from

Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

circles. The disagreements over and the difficulties with the assimilation of the eastern Ruthenian populations of the Commonwealth had become clearly discernible; an attempt to settle the issue was made in the religious

Union of Brest

The Union of Brest took place in 1595–1596 and represented an agreement by Eastern Orthodox Churches in the Ruthenian portions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to accept the Pope's authority while maintaining Eastern Orthodox liturgical ...

. On the military front, a series of

Cossack

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borders of Ukraine and Rus ...

uprisings

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

took place.

The Commonwealth, assertive militarily under King

Stephen Báthory

Stephen Báthory (; ; ; 27 September 1533 – 12 December 1586) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (1576–1586) as well as Prince of Transylvania, earlier Voivode of Transylvania (1571–1576).

The son of Stephen VIII Báthory ...

, suffered from dynastic distractions during the reigns of the

Vasa kings

Sigismund III

Sigismund III Vasa (, ; 20 June 1566 – 30 April 1632

N.S.) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1587 to 1632 and, as Sigismund, King of Sweden from 1592 to 1599. He was the first Polish sovereign from the House of Vasa. Relig ...

and

Władysław IV Władysław is a Polish given male name, cognate with Vladislav. The feminine form is Władysława, archaic forms are Włodzisław (male) and Włodzisława (female), and Wladislaw is a variation. These names may refer to:

People Mononym

* Włodzis ...

. It had also become a playground of internal conflicts, in which the kings, powerful magnates and factions of nobility were the main actors. The Commonwealth fought wars with

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

,

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

and the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

.

The situation, however, soon radically deteriorated. From 1648 the

Cossack

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borders of Ukraine and Rus ...

Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

engulfed the south and east, and was soon followed by a

Swedish invasion, which raged through core Polish lands. Warfare with the Cossacks and Russia left

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

divided, with the eastern part, lost by the Commonwealth, becoming the

Tsardom

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Europ ...

's dependency.

John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( (); (); () 17 August 1629 – 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobieski was educated at the Jagiellonian University and toured Eur ...

, fighting protracted wars with the Ottoman Empire, revived the Commonwealth's military might once more, in the process helping decisively

in 1683 to

deliver Vienna from a

Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

* Something related to Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities in the former Ottoman Empire

* The w ...

onslaught.

The Commonwealth, subjected to

almost constant warfare until 1720, suffered devastating population losses, massive damage to its economy and social structure. The government became ineffective because of large scale internal conflicts (e.g.

Lubomirski's Rokosz

Lubomirski's rebellion (), was a rebellion against Polish King John II Casimir that was initiated by Jerzy Sebastian Lubomirski, a member of the Polish nobility.

From 1665 to 1666, Lubomirski's supporters paralyzed the proceedings of the Sejm. L ...

against

John II Casimir

John II Casimir Vasa (; ; 22 March 1609 – 16 December 1672) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1648 to his abdication in 1668 as well as a claimant to the throne of Sweden from 1648 to 1660. He was the first son of Sigis ...

and other

confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

s), corrupted legislative processes (''

liberum veto

The ''liberum veto'' (Latin for "free veto") was a parliamentary device in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was a form of unanimity voting rule that allowed any member of the Sejm (legislature) to force an immediate end to the current s ...

'') and manipulation by foreign interests. The "ruling" nobility class fell under control of a handful of powerful families with established territorial domains. The reigns of two kings of the

Saxon

The Saxons, sometimes called the Old Saxons or Continental Saxons, were a Germanic people of early medieval "Old" Saxony () which became a Carolingian " stem duchy" in 804, in what is now northern Germany. Many of their neighbours were, like th ...

Wettin dynasty

The House of Wettin () was a dynasty which included Saxon kings, prince-electors, dukes, and counts, who once ruled territories in the present-day German federated states of Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia. The dynasty is one of the oldest ...

,

Augustus II

Augustus II the Strong (12 May 1670 – 1 February 1733), was Elector of Saxony from 1694 as well as King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1697 to 1706 and from 1709 until his death in 1733. He belonged to the Albertine branch of the H ...

and

Augustus III

Augustus III (; – "the Saxon"; ; 17 October 1696 5 October 1763) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1733 until 1763, as well as Elector of Saxony in the Holy Roman Empire where he was known as Frederick Augustus II ().

He w ...

, brought the Commonwealth further disintegration.

The Polish-Lithuanian state was dominated by the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

from the time of

Peter the Great

Peter I (, ;

– ), better known as Peter the Great, was the Sovereign, Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia, Tsar of all Russia from 1682 and the first Emperor of Russia, Emperor of all Russia from 1721 until his death in 1725. He reigned j ...

. This foreign control reached its climax under

Catherine the Great

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

, and involved at that time also the

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

and the Austrian

Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

. During the later part of the 18th century the Commonwealth recovered economically, developed culturally and attempted fundamental internal reforms. The reform activity provoked hostile reaction and eventually military response on the part of the neighboring powers. The

royal election of 1764 resulted in the reign of

Stanisław August Poniatowski

Stanisław II August (born Stanisław Antoni Poniatowski; 17 January 1732 – 12 February 1798), known also by his regnal Latin name Stanislaus II Augustus, and as Stanisław August Poniatowski (), was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuani ...

.

The

Bar Confederation

The Bar Confederation (; 1768–1772) was an association of Polish nobles (''szlachta'') formed at the fortress of Bar, Ukraine, Bar in Podolia (now Ukraine), in 1768 to defend the internal and external independence of the Polish–Lithuanian C ...

of 1768 was a ''szlachta'' rebellion directed against Russia and the Polish king. It was brought under control and followed in 1772 by the

First Partition of the Commonwealth, a permanent encroachment on the outer Commonwealth provinces by Russia, Prussia and Austria.

The

Great, or Four-Year Sejm was convened by Stanisław August in 1788. The Sejm's landmark achievement was the passing of the

Constitution of May 3, 1791

The Constitution of 3 May 1791, titled the Government Act, was a written constitution for the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that was adopted by the Great Sejm that met between 1788 and 1792. The Commonwealth was a dual monarchy comprising ...

, considered the first in modern Europe. The constitutional reform generated strong opposition from conservative circles in the Commonwealth's upper nobility and from Catherine II.

The nobility's

Targowica Confederation

The Targowica Confederation (, , ) was a confederation established by Polish and Lithuanian magnates on 27 April 1792, in Saint Petersburg, with the backing of the Russian Empress Catherine II. The confederation opposed the Constitution of 3 May ...

appealed to Empress Catherine for help and in May 1792 the Russian army entered the territory of the Commonwealth. The

defensive war fought by the forces of the Commonwealth ended when

the King, convinced of the futility of resistance, capitulated by joining the Targowica Confederation. Russia and Prussia in 1793 arranged for and executed the

Second Partition of the Commonwealth, which left the country with critically reduced territory, practically incapable of independent existence.

Reformers and patriots were soon preparing for a national insurrection.

Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko (; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish Military engineering, military engineer, statesman, and military leader who then became a national hero in Poland, the United States, Lithuania, and ...

, chosen as its leader, on March 24, 1794, in

Cracow (Kraków) declared a

national uprising. Kościuszko emancipated and enrolled in his army many peasants, but the hard-fought insurrection ended in suppression by the forces of Russia and Prussia. The

third and final partition of the Commonwealth was

undertaken again by all three partitioning powers, and in 1795 the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth ceased to exist.

Early elective monarchy

Non-hereditary royal succession

The death of

Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus (, ; 1 August 1520 – 7 July 1572) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, the son of Sigismund I the Old, whom Sigismund II succeeded in 1548. He was the first ruler of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and t ...

in 1572 ended the nearly two centuries of the rule of the

Jagiellon dynasty

The Jagiellonian ( ) or Jagellonian dynasty ( ; ; ), otherwise the Jagiellon dynasty (), the House of Jagiellon (), or simply the Jagiellons (; ; ), was the name assumed by a cadet branch of the Lithuanian ducal dynasty of Gediminids upon recep ...

in Poland. It was followed by a three-year

interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of revolutionary breach of legal continuity, discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one m ...

period, during which the Polish nobility (''

szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

'') was searching for ways to continue the governance process and elect a new monarch. Lower ''szlachta'' was now included in the selection process and adjustments were made to the constitutional system. The power of the monarch was further circumscribed in favor of the expanding noble class, which sought to ensure its future domination.

Each king had to sign the so-called

Henrician Articles

The Henrician Articles or King Henry's Articles (; ; ) were a constitution in the form of a permanent agreement made in 1573 between the "Polish nation" (the szlachta, or nobility, of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) and a newly-elected Pol ...

(named after

Henry of Valois Henry of Valois may refer to:

*Henry II of France (1519–1559), King of France

*Henry III of France (1551–1589), King of France and Poland

See also

*Henri Valois

Henri Valois (; September 10, 1603, in Paris – May 7, 1676, in Paris) or ...

, the first post-Jagiellon king), which were the basis of the political system of Poland, and the ''

pacta conventa

''Pacta conventa'' (Latin for "articles of agreement") was a contractual agreement entered into between the "Polish nation" (i.e., the szlachta (nobility) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) and a newly elected king upon his "free electi ...

'', which were various further personal obligations of the chosen king. From that point, the king was effectively a partner with the nobility, a top member of the diet (

sejm

The Sejm (), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (), is the lower house of the bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of the Third Polish Republic since the Polish People' ...

), and was constantly supervised by a group of upper-rank nobles,

senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

s from sejm's upper chamber.

The disappearance of the

ruling dynasty and its replacement with a non-hereditary

elective monarchy

An elective monarchy is a monarchy ruled by a monarch who is elected, in contrast to a hereditary monarchy in which the office is automatically passed down as a family inheritance. The manner of election, the nature of candidate qualifications, ...

made the constitutional system much more unstable. With each

election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

the noble electors wanted more power for themselves and less for the monarch, although there were practical limits to how much the kings could be constrained. A semi-permanent power struggle resulted, to which the

magnate

The term magnate, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s and lesser ''szlachta'' added their own constant manipulations and bickering and authority eroded from the government's center. Eventually foreign states had taken advantage of the vacuum and replaced the nobility of the Commonwealth as the real arbiter of royal elections and of overall power in Poland-Lithuania.

In its periodic opportunities to fill the throne, the ''szlachta'' exhibited a preference for foreign candidates who would not found another strong dynasty. This policy produced monarchs who were either ineffective or in constant debilitating conflict with the nobility. The kings of alien origin were initially unfamiliar with the internal dynamics of the Commonwealth, had remained distracted by the politics of their native countries, and often inclined to subordinate the interests of the Commonwealth to those of their own country and ruling house.

Henry of Valois (1573–1574)

In April 1573,

Sigismund Sigismund (variants: Sigmund, Siegmund) is a German proper name, meaning "protection through victory", from Old High German ''sigu'' "victory" + ''munt'' "hand, protection". Tacitus latinises it ''Segimundus''. There appears to be an older form of ...

's sister

Anna

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna of East Anglia, King (died c.654)

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th c ...

, the sole heir to the crown, convinced the Sejm to elect the French prince

Henry of Valois Henry of Valois may refer to:

*Henry II of France (1519–1559), King of France

*Henry III of France (1551–1589), King of France and Poland

See also

*Henri Valois

Henri Valois (; September 10, 1603, in Paris – May 7, 1676, in Paris) or ...

as king. Her marriage with Henry was to further legitimize Henry's rule, but less than a year after his coronation, Henry fled Poland to succeed his brother

Charles IX as King of France.

Stephen Báthory (1576–1586)

The able and militarily as well as domestically assertive

Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

n

Stephen Báthory

Stephen Báthory (; ; ; 27 September 1533 – 12 December 1586) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (1576–1586) as well as Prince of Transylvania, earlier Voivode of Transylvania (1571–1576).

The son of Stephen VIII Báthory ...

(1576–1586) counts among the few more highly regarded elective kings.

During the

Livonian War

The Livonian War (1558–1583) concerned control of Terra Mariana, Old Livonia (in the territory of present-day Estonia and Latvia). The Tsardom of Russia faced a varying coalition of the Denmark–Norway, Dano-Norwegian Realm, the Kingdom ...

(1558–1582), fought between

Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (; – ), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible,; ; monastic name: Jonah. was Grand Prince of Moscow, Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1533 to 1547, and the first Tsar of all Russia, Tsar and Grand Prince of all R ...

of

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and Poland-Lithuania,

Pskov

Pskov ( rus, Псков, a=Ru-Псков.oga, p=psˈkof; see also Names of Pskov in different languages, names in other languages) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city in northwestern Russia and the administrative center of Pskov O ...

was besieged by Polish forces. The city was not captured, but Báthory, with his

Chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

Jan Zamoyski

Jan Sariusz Zamoyski (; 19 March 1542 – 3 June 1605) was a Polish nobleman, magnate, statesman and the 1st '' ordynat'' of Zamość. He served as the Royal Secretary from 1565, Deputy Chancellor from 1576, Grand Chancellor of the Crown f ...

, led the Polish army in a decisive campaign and forced Russia to return territories previously taken, gaining

Livonia

Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia.

By the end of the 13th century, the name was extende ...

and

Polotsk

Polotsk () or Polatsk () is a town in Vitebsk Region, Belarus. It is situated on the Dvina River and serves as the administrative center of Polotsk District. Polotsk is served by Polotsk Airport and Borovitsy air base. As of 2025, it has a pop ...

. In 1582, the war ended with the

Truce of Jam Zapolski

The Truce or Treaty of Yam-Zapolsky (Ям-Запольский) or Jam Zapolski, signed on 15 January 1582 between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia, was one of the treaties that ended the Livonian War. It followed t ...

.

The Commonwealth forces retrieved most of the lost provinces. At the end of Báthory's reign, Poland ruled two main

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

ports:

Danzig (Gdańsk), controlling the

Vistula

The Vistula (; ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest in Europe, at in length. Its drainage basin, extending into three other countries apart from Poland, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra i ...

River trade and

Riga

Riga ( ) is the capital, Primate city, primate, and List of cities and towns in Latvia, largest city of Latvia. Home to 591,882 inhabitants (as of 2025), the city accounts for a third of Latvia's total population. The population of Riga Planni ...

, controlling the

Daugava River

The Daugava ( ), also known as the Western Dvina or the Väina River, is a large river rising in the Valdai Hills of Russia that flows through Belarus and Latvia into the Gulf of Riga of the Baltic Sea. The Daugava rises close to the source of ...

trade. Both cities were among the largest in the country.

War of the Polish Succession

Stephen Báthory planned a

Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

alliance against the

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

ic

Ottomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

. He proposed an

anti-Ottoman alliance with Russia, which he considered necessary for his anti-Ottoman

crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

. Russia however was heading for its

Time of Troubles

The Time of Troubles (), also known as Smuta (), was a period of political crisis in Tsardom of Russia, Russia which began in 1598 with the death of Feodor I of Russia, Feodor I, the last of the Rurikids, House of Rurik, and ended in 1613 wit ...

and he could not find a partner there. When Báthory died, there was a year-long interregnum. Emperor

Mathias' brother, Archduke

Maximilian III, tried to claim the Polish throne, but was defeated at

Byczyna

Byczyna (Latin: ''Bicina'', ''Bicinium''; ) is a town in Kluczbork County, Opole Voivodeship, in south-western Poland, with 3,490 inhabitants as of December 2021.

Etymology

The name comes from the Old Polish word ''byczyna'', which means a place ...

during the

War of the Polish Succession (1587–1588)

The War of the Polish Succession or the Habsburg-Polish War took place from 1587 to 1588 over the election of the successor to the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Stephen Báthory. The war was fought between factions of Sigismund III V ...

.

Sigismund III Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa (, ; 20 June 1566 – 30 April 1632

N.S.) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1587 to 1632 and, as Sigismund, King of Sweden from 1592 to 1599. He was the first Polish sovereign from the House of Vasa. Re ...

became the Commonwealth's next king, the first of the three rulers from the

Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

House of Vasa

The House of Vasa or Wasa was a Dynasty, royal house that was founded in 1523 in Sweden. Its members ruled the Kingdom of Sweden from 1523 to 1654 and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1587 to 1668. Its agnatic line became extinct with t ...

.

House of Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa (1587–1632)

Sigismund III Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa (, ; 20 June 1566 – 30 April 1632

N.S.) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1587 to 1632 and, as Sigismund, King of Sweden from 1592 to 1599. He was the first Polish sovereign from the House of Vasa. Re ...

was King of Poland 1587–1632 and King of

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

1592–1599. He was the son of

John III Vasa of Sweden and

Catherine

Katherine (), also spelled Catherine and Catherina, other variations, is a feminine given name. The name and its variants are popular in countries where large Christian populations exist, because of its associations with one of the earliest Ch ...

, the daughter of

Sigismund I the Old

Sigismund I the Old (, ; 1 January 1467 – 1 April 1548) was List of Polish monarchs, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1506 until his death in 1548. Sigismund I was a member of the Jagiellonian dynasty, the son of Casimir IV of P ...

of Poland. He annoyed the Polish nobles by deliberately dressing in Spanish and other Western European styles (including French hosiery). An ardent

Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, Sigismund III was determined to win the Swedish crown and bring Sweden back to Catholicism. Subsequently, Sigismund III involved Poland in unnecessary and unpopular

wars with Sweden during which the diet refused him money and soldiers and Sweden seized

Livonia

Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia.

By the end of the 13th century, the name was extende ...

and

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

.

The first few years of Sigismund's reign (until 1598) saw Poland and Sweden united in a

personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

that made the

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

an internal lake. However, a

rebellion in Sweden started the chain of events that would involve the Commonwealth in more than a century of

warfare with Sweden.

The

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

embarked on an ideological counter-offensive and

Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

claimed many converts from

Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

circles. The

Union of Brest

The Union of Brest took place in 1595–1596 and represented an agreement by Eastern Orthodox Churches in the Ruthenian portions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to accept the Pope's authority while maintaining Eastern Orthodox liturgical ...

split the

Eastern Christians

Eastern Christianity comprises Christian traditions and church families that originally developed during classical and late antiquity in the Eastern Mediterranean region or locations further east, south or north. The term does not describe a ...

of the Commonwealth. In order to further Catholicism, the Uniate Church (acknowledging papal supremacy but following

Eastern ritual and

Slavonic liturgy) was created at the

Synod of Brest in 1596. The Uniates drew many followers away from the

Orthodox Church

Orthodox Church may refer to:

* Eastern Orthodox Church, the second-largest Christian church in the world

* Oriental Orthodox Churches, a branch of Eastern Christianity

* Orthodox Presbyterian Church, a confessional Presbyterian denomination loc ...

in the Commonwealth's eastern territories.

Sigismund's attempts to introduce

absolutism, then becoming prevalent in the rest of Europe, and his goal of reacquiring the throne of Sweden for himself, resulted in a

rebellion of the ''szlachta'' (gentry). In 1607, the Polish nobility threatened to suspend the agreements with their elected king but did not attempt his overthrow.

For ten years between 1619 and 1629, the Commonwealth was at its greatest geographical extent in history. In 1619, the Russo-Polish

Truce of Deulino

The Truce of Deulino (also known as Peace or Treaty of Dywilino) concluded the Polish–Russian War of 1609–1618 between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia. It was signed in the village of on 11 December 1618 and t ...

came into effect, whereby Russia conceded Commonwealth control over

Smolensk

Smolensk is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow.

First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest cities in Russia. It has been a regional capital for most of ...

and several other border territories. In 1629, the Swedish-Polish

Truce of Altmark

__NOTOC__

The six-year Truce of Altmark (or Treaty of Stary Targ, , ) was signed on 16 (O.S.)/26 (N.S.) September 1629 in the village of Altmark ( Stary Targ), in Poland, by the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Sweden, with helped by Riche ...

took place; the Commonwealth ceded to Sweden most of Livonia, which the Swedes had invaded in 1626.

Sigismund III Vasa failed to strengthen the Commonwealth or to solve its internal problems; he concentrated on futile attempts to regain his former Swedish throne.

Commonwealth wars with Sweden and Moscow

Sigismund’s desire to reclaim the Swedish throne drove him into prolonged Polish–Swedish War (1600–1629), military adventures waged against Sweden under Charles IX of Sweden, Charles IX and later also Russia. In 1598, Sigismund tried to defeat Charles with a mixed army from Sweden and Poland, but was defeated in the Battle of Stångebro.

As the Tsardom of Russia went through its "

Time of Troubles

The Time of Troubles (), also known as Smuta (), was a period of political crisis in Tsardom of Russia, Russia which began in 1598 with the death of Feodor I of Russia, Feodor I, the last of the Rurikids, House of Rurik, and ended in 1613 wit ...

," Poland failed to capitalize on the situation. Polish–Muscovite War (1605–1618), Military campaigns undertaken brought Poland at times close to a conquest of Russia and the Baltic coast during the Time of Troubles and False Dmitriy I, False Dimitris, but military burden imposed by the ongoing rivalry also along other frontiers (the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

and Sweden) prevented this from being accomplished. After Polish–Muscovite War (1605–1618), prolonged war with Russia, Polish forces occupied Moscow in 1610. The office of tsar, then vacant in Russia, was offered to Sigismund's son, Władysław IV Vasa, Władysław. Sigismund, however, opposed his son's accession as tsar, as he hoped to obtain the Russian throne for himself. Two years later the Poles were driven out of Moscow and Poland lost an opportunity for a Polish-Russian union.

Poland escaped the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), which ravaged everything to the west, especially Prussia. In 1618, the John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, Elector of Brandenburg became hereditary ruler of the Duchy of Prussia on the Baltic Sea, Baltic coast. From then on, Poland's link to the Baltic Sea was bordered on both sides by two provinces of the same Brandenburg-Prussia, German state.

Southern wars

The Commonwealth viewed itself as the "bulwark of the Christendom" and together with the House of Habsburg, Habsburgs and the Republic of Venice stood in the way of the Ottoman plans of European conquests. Since the second half of the 16th century, the Polish-Ottomans relations were worsened by the escalation of

Cossack

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borders of Ukraine and Rus ...

-Crimean Tatars, Tatar border warfare, which turned the entire border region between the Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire into a Wild Fields, semi-permanent warzone. A constant threat from Crimean Khanate, Crimean Tatars supported the appearance of Zaporozhian Cossacks, Cossackdom.

In 1595,

magnate

The term magnate, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Moldavian Magnate Wars, intervened in the affairs of Moldavia. This started a series of conflicts that would soon spread to

Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

, Wallachia and Hungary, when the forces of the Polish magnates clashed with the forces backed by the Ottoman Empire and occasionally the Habsburgs, all competing for the domination over that region.

With the Commonwealth engaged on its northern and eastern borders with nearly constant conflicts against Sweden and Russia, its armies were spread thin. The southern wars culminated in the Polish defeat at the Battle of Cecora (1620), Battle of Cecora in 1620. The Commonwealth was forced to renounce all claims to Moldavia, Transylvania, Wallachia and Hungary.

Religious and social tensions

The population of Poland-Lithuania was neither overwhelmingly Roman Catholic nor Polish. This circumstance resulted from the federation with the

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a sovereign state in northeastern Europe that existed from the 13th century, succeeding the Kingdom of Lithuania, to the late 18th century, when the territory was suppressed during the 1795 Partitions of Poland, ...

, where East Slavs, East Slavic Ruthenian populations predominated. In the days of the "Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Republic of Nobles", to be Polish was much less an indication of ethnicity than of rank; it was a designation largely reserved for the szlachta, landed noble class, which included members of Polish and non-Polish origin alike. Generally speaking, the ethnically non-Polish noble families of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania gradually adopted the Polish language and Polish culture, culture.

As a result, in the eastern territories of the Kingdom the Polish-speaking landed nobility dominated over the peasantry, whose great majority was neither Polish nor Catholic. Moreover, the decades of peace brought huge colonization efforts to

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, which heightened tensions between peasants, History of the Jews in Poland, Jews and nobles. The tensions were aggravated by the conflicts between the Eastern Orthodox Church, Orthodox and Greek Catholic (both Church Slavonic language, Church Slavonic liturgy) churches following the

Union of Brest

The Union of Brest took place in 1595–1596 and represented an agreement by Eastern Orthodox Churches in the Ruthenian portions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to accept the Pope's authority while maintaining Eastern Orthodox liturgical ...

and by several Cossack uprisings. In the west and north of the country, cities had large Germans, German minorities, often of Reformed churches, reformed beliefs. According to the ''Risāle-yi Tatar-i Leh'' (an account of the Lipka Tatars written for Suleiman the Magnificent by an anonymous Islam in Poland, Polish Muslim during a stay in Istanbul in 1557–8, on his way to Mecca) there were 100 Lipka Tatar settlements with mosques in Poland. In 1672, the Tatar subjects rose up in an Lipka Rebellion, open rebellion against the Commonwealth.

Władysław IV Vasa (1632–1648)

During the reign of Sigismund's son, Władysław IV Vasa, the Cossacks in Ukraine Cossack uprisings, revolted against Poland; wars with Russia and Turkey weakened the country; and ''szlachta'' obtained new privileges, mainly exemption from income tax.

Władysław IV aimed to achieve many military goals, including conquests of Russia, Sweden and Turkey. His reign is that of many small victories, few of them bringing anything worthwhile to the Commonwealth. He was once elected a Russian tsar, but never had any control over Russian territories. Like his father, Władysław was involved in Swedish dynastic ambitions. He failed to strengthen the Commonwealth or prevent the crippling events of the

Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

and the Deluge (history), Deluge that devastated the Commonwealth from 1648 onward.

John Casimir Vasa (1648–1668)

The reign of Władysław's brother John II Casimir Vasa, John Casimir, the last of the Vasas, was dominated by the culmination in the Polish–Swedish wars, war with Sweden, the groundwork for which was laid down by the two previous Vasa kings. In 1660, John Casimir was forced to renounce his claims to the Swedish throne and acknowledge Swedish sovereignty over

Livonia

Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia.

By the end of the 13th century, the name was extende ...

and city of

Riga

Riga ( ) is the capital, Primate city, primate, and List of cities and towns in Latvia, largest city of Latvia. Home to 591,882 inhabitants (as of 2025), the city accounts for a third of Latvia's total population. The population of Riga Planni ...

.

Under John Casimir, the Cossacks grew in power and Khmelnytsky Uprising, at times were able to defeat the Poles; the Deluge (history), Swedes occupied much of Poland, including Warsaw, the capital; and the King, abandoned or betrayed by his subjects, had to seek temporary refuge in Silesia. As a result of the wars with the Cossacks and Russia, the Commonwealth lost Kiev,

Smolensk

Smolensk is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow.

First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest cities in Russia. It has been a regional capital for most of ...

, and all the areas east of the Dnieper River by the Truce of Andrusovo, Treaty of Andrusovo (1667). During John Casimir's reign, East Prussia successfully renounced its formal status as a Fee (feudal tenure), fief of Poland. Internally, the process of disintegration started. The nobles, making their own alliances with foreign powers, pursued independent policies; the Lubomirski's Rokosz, rebellion of Jerzy Sebastian Lubomirski, Jerzy Lubomirski shook the throne.

John Casimir, a broken, disillusioned man, abdicated the Polish throne on 16 September 1668 amid internal anarchy and strife and returned to France, where he joined the Society of Jesus, Jesuit order and became a monk. He died in 1672.

Khmelnytsky Uprising (1648–1654)

The

Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

, by far the largest of the Cossack uprisings, proved disastrous for the Commonwealth. The Cossacks, allied with the Tatars, defeated the forces of the Commonwealth in several battles, the Commonwealth scored a major victory at Battle of Berestechko, Berestechko, but the Polish-Lithuanian empire ended up "fatally wounded". The easternmost parts of its territory were effectively lost to Russia, which resulted in a long-term shift in the balance of power. In the short-term the country was weakened at the moment of the Deluge (history), invasion by Sweden.

The Deluge (1648–1667)

Although Poland-Lithuania was unaffected by the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), the following two decades subjected the nation to one of its worst trials ever. This colorful but ruinous interval, the stuff of legend and popular historical novels of Nobel Prize, Nobel laureate Henryk Sienkiewicz, became known as ''potop'', or the Deluge (history), Deluge, for the magnitude and suddenness of its hardships. The emergency began when the Ukraine, Ukrainian Zaporozhian Cossacks, Cossacks rose in revolt and declared an independent state based in the vicinity of Kiev, allied with the Crimean Khanate, Crimean Tatars and the Ottoman Empire. Their leader Bohdan Khmelnytsky defeated Polish armies in Battle of Zhovti Vody, 1648 and Battle of Batih, 1652, and after the Cossacks concluded the Treaty of Pereyaslav with Russia in 1654, Tsar Alexis of Russia, Alexis overran the entire eastern part of the Commonwealth (Ukraine) to Lviv, Lwów (Lviv). Taking advantage of Poland's preoccupation in the east and weakness, Charles X Gustav of Sweden intervened. Most of the Polish nobility along with the Polish vassal Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg, Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia agreed to recognize him as king after he promised to drive out the Russians. However, the Swedish troops embarked on an orgy of looting and destruction, which caused the Polish populace to rise up in revolt. The Swedes overran the remainder of Poland except for Lwów and

Danzig (Gdańsk).

Poland-Lithuania rallied to recover most of its losses from the Swedes. In exchange for breaking the alliance with Sweden, Frederick William, the ruler of Duchy of Prussia, Ducal Prussia, was released from his vassalage and became a ''de facto'' independent sovereign, while much of the Polish

Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

nobility went over to the side of the Swedes. Under Hetman Stefan Czarniecki, the Poles and Lithuanians had driven the Swedes from the Commonwealth's territory by 1657. The armies of Frederick William intervened and were also defeated. Frederick William's rule over Duchy of Prussia, East Prussia was Treaty of Bromberg, recognized, although Poland retained the right of succession until 1773.

The Russo-Polish War (1654–1667), thirteen-year struggle over control of Ukraine included an Treaty of Hadiach, attempted formal union of Ukraine with the Commonwealth as an equal partner (1658) and Polish military successes in 1660–1662. This was not enough to keep eastern Ukraine. Under the pressure of continuing Ukrainian unrest and the threat of a Polish–Cossack–Tatar War (1666–71), Turkish-Tatar intervention, the Commonwealth and Russia signed in 1667 an Truce of Andrusovo, agreement in the village of Andrusovo near

Smolensk

Smolensk is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow.

First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest cities in Russia. It has been a regional capital for most of ...

, according to which eastern Ukraine (left bank of the Dnieper River) now belonged to Russia. Kiev was also leased to Russia for two years, but never returned and eventually Poland recognized Russian control of the city.

The ''deluge (history), potop'' wars episode inflicted irremediable damage and contributed heavily to the ultimate demise of the state. Held responsible for the greatest disaster in Polish history, John Casimir abdicated in 1668. The population of the Commonwealth had been reduced by a staggering 1/3, by military casualties, slave raids, plague epidemics, and mass murders of civilians. Most of Poland's cities were reduced to rubble, and the nation's economic base was decimated. The war had been paid for by large-scale minting of worthless currency, causing runaway inflation. Religious feelings had also been inflamed by the conflict, ending tolerance of non-Catholic beliefs. Henceforth, the Commonwealth would be on the strategic defensive facing hostile and increasingly more powerful neighbors.

Commonwealth after the Deluge

In the Treaty of Oliva in 1660, John Casimir finally renounced his claims to the Swedish crown, which ended the feud between Sweden and the Commonwealth and the accompanying string of wars between those countries (War against Sigismund (1598–1599), Polish–Swedish wars (1600–1629) and the Second Northern War, Northern War (1655–1660)).

After the Truce of Andrusovo of 1667 and the Eternal Peace Treaty of 1686, the Commonwealth lost left-bank Ukraine to Russia.

Polish culture and the Union of Brest, Uniate East Slavs, East Slavic Greek Catholic Church gradually advanced. By the 18th century, the populations of Duchy of Prussia, Ducal Prussia and Royal Prussia were a mixture of Catholics and Protestants and used both the German and Polish languages. The rest of Poland and most of Lithuania remained overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, while Ukraine and some parts of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Belarus) were Greek Orthodox and Greek Catholic (both Church Slavonic language, Church Slavonic liturgy). The society consisted of the upper stratum (8% nobles, 1% clergy), townspeople and the peasant majority. Various nationalities/ethnicities or linguistic groups were present, including Poles, Germans, Jews, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Armenians and Tatars, among others.

Native kings; wars with the Ottoman Empire

Michael Korybut Wiśniowiecki (1669–1673)

Following the abdication of King John II Casimir Vasa, John Casimir Vasa and the end of the The Deluge (Polish history), Deluge, the Polish nobility (

szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

), disappointed with the rule of the House of Vasa, Vasa dynasty monarchs, elected Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki as king, believing that as a non-foreigner he would further the interests of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He was the first ruler of Polish origin since the last of

Jagiellon dynasty

The Jagiellonian ( ) or Jagellonian dynasty ( ; ; ), otherwise the Jagiellon dynasty (), the House of Jagiellon (), or simply the Jagiellons (; ; ), was the name assumed by a cadet branch of the Lithuanian ducal dynasty of Gediminids upon recep ...

,

Sigismund II Augustus

Sigismund II Augustus (, ; 1 August 1520 – 7 July 1572) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, the son of Sigismund I the Old, whom Sigismund II succeeded in 1548. He was the first ruler of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and t ...

, died in 1572. Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki, Michael was a son of a controversial but popular with ''szlachta'' military commander Jeremi Wiśniowiecki, known for his actions during the

Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

.

His reign was not successful. Michael lost a Polish–Ottoman War (1672–76), war against the Ottoman Empire, with the Ottoman Empire, Turks occupying Podolia and most of Ukraine from 1672 to 1673. Wiśniowiecki was a passive monarch who readily played into the hands of the House of Habsburg, Habsburgs. He was unable to cope with his responsibilities and with the different quarreling factions within Poland.

John III Sobieski (1674–1696)

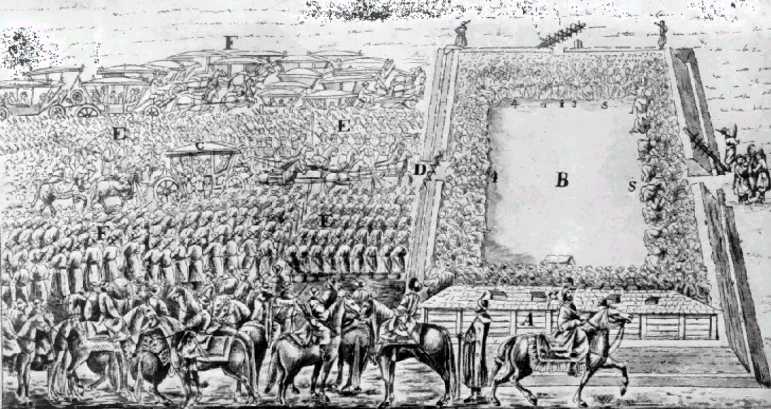

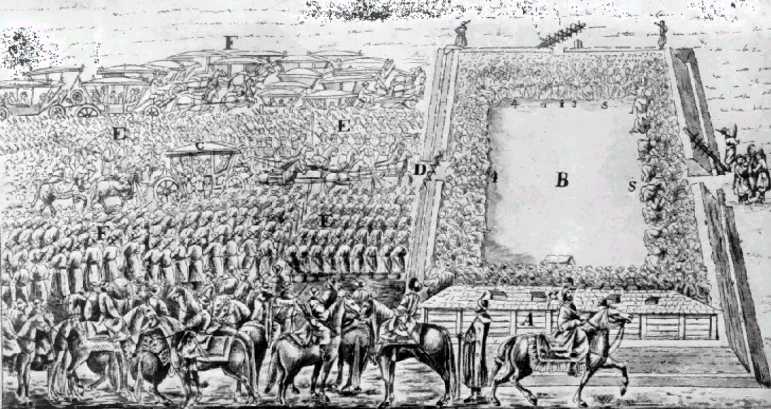

Hetman John III Sobieski, John Sobieski was the Commonwealth's last great military commander; he was active and effective in the continuing Battle of Khotyn (1673), warfare with the Ottoman Empire. Sobieski was elected as another "Piast" (of Polish family) king. John III Sobieski, John III's most famous achievement was the decisive contribution by the Commonwealth's forces led by him to the defeat of the Ottoman Empire's army in 1683, at the Battle of Vienna.

The Ottomans, if victorious, would have likely become a threat to Western Europe, but the successful battle eliminated that possibility and marked the turning point in a 250-year struggle between the forces of Christianity, Christian Europe and the

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

ic Ottoman Empire. Over the 16 years following the battle (the Great Turkish War), the Turks would be permanently driven south of the Danube, Danube River, never to threaten Central Europe again.

For the Commonwealth there was no big payoff for the Turkish victories and the John III Sobieski, rescuer of Vienna had to cede territories to Russia in return for promised aid against the Crimean Khanate, Crimean Tatars and Turks. Poland had previously formally relinquished all claims to Kiev in 1686. On other fronts John III was even less successful, including agreements with France and Sweden in a failed attempt to regain the Duchy of Prussia. Only when the Holy League (1684), Holy League concluded Treaty of Karlowitz, peace with the Ottomans in 1699, Poland recovered Podolia and parts of Ukraine.

Decay of the Commonwealth

Beginning in the 17th century, because of the deteriorating state of internal politics and government and destructive wars, the nobles' democracy gradually declined into anarchism, anarchy, making the once powerful Commonwealth vulnerable to foreign interference and intervention. In the late 17th century Poland-Lithuania had virtually ceased to function as a coherent and genuinely independent state.

During the 18th century, the Polish-Lithuanian federation became subject to manipulations by

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

, Russian Empire, Russia, the

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

, France and Habsburg monarchy, Austria. Poland's weakness was exacerbated by an unworkable parliamentary rule which allowed each deputy in

sejm

The Sejm (), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (), is the lower house of the bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of the Third Polish Republic since the Polish People' ...

to use his liberum veto, vetoing power to stop further parliamentary proceedings for the given session. This greatly weakened the central authority of Poland and paved the way for its destruction.

The decline leading to foreign domination had begun in earnest several decades after the end of the

Jagiellon dynasty

The Jagiellonian ( ) or Jagellonian dynasty ( ; ; ), otherwise the Jagiellon dynasty (), the House of Jagiellon (), or simply the Jagiellons (; ; ), was the name assumed by a cadet branch of the Lithuanian ducal dynasty of Gediminids upon recep ...

. Insufficient and ineffective taxation, virulently contested by the ''szlachta'' whenever it impinged on their perceived interests, was another contributor to the downfall. There were two kinds of taxes, those levied by the Crown and those levied by legislative assemblies. The Crown raised both customs duties and taxes on land, transportation, salt, lead, and silver. Sejm raised a land tax, a city tax, a tax on alcohol, and a tax per head, poll tax on Jews. The exports and imports by the nobility were tax-free. The disorganized and increasingly decentralized nature of tax gathering and the numerous exceptions from taxation meant that the king and the state had insufficient revenue to perform military or civilian functions. At one point the king secretly and illegally sold crown jewels.

The nobles or ''szlachta'' became increasingly focused on guarding their own "liberties" and blocked any policies designed to strengthen the nation or build a powerful army. Beginning in 1652, the fatal practice of ''

liberum veto

The ''liberum veto'' (Latin for "free veto") was a parliamentary device in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was a form of unanimity voting rule that allowed any member of the Sejm (legislature) to force an immediate end to the current s ...

'' was their basic tool. It required unanimity in sejm and permitted even a single deputy not only to block any measure but to cause dissolution of a sejm and submission of all measures already passed to the next sejm. Foreign diplomats, using bribery or persuasion, routinely caused the dissolution of inconvenient sessions of sejm. Of the 37 sejms in 1674–96, only 12 were able to enact any legislation. The others were dissolved by the ''liberum veto'' of one person or another.

The Commonwealth's last martial triumph occurred in 1683 when King

John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( (); (); () 17 August 1629 – 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobieski was educated at the Jagiellonian University and toured Eur ...

drove the Ottoman Empire, Turks from the gates of Vienna with a heavy cavalry charge. Poland's important role in aiding the Holy League (1684), European alliance to roll back the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

was rewarded with some territory in Podolia by the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699). This partial success did little to mask the internal weakness and paralysis of the Polish–Lithuanian political system.

For the next quarter century, Poland was often a pawn in Russia's campaigns against other powers. When John III died in 1697, 18 candidates vied for the throne, which ultimately went to Augustus II the Strong, Frederick Augustus of Saxony, who then converted to Catholicism. Ruling as

Augustus II

Augustus II the Strong (12 May 1670 – 1 February 1733), was Elector of Saxony from 1694 as well as King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1697 to 1706 and from 1709 until his death in 1733. He belonged to the Albertine branch of the H ...

, his reign presented the opportunity to unite Electorate of Saxony, Saxony (an industrialized area) with Poland, a country rich in mineral resources. The King however lacked skill in foreign policy and became entangled in a war with Sweden. His allies, the Russians and the Danes, were repelled by Charles XII of Sweden, beginning the Great Northern War. Charles installed a Stanisław Leszczyński, puppet ruler in Poland and marched on Saxony, compelling Augustus to give up his crown and turning Poland into a base for the Swedish army. Poland was again devastated by the armies of Sweden, Russia, and Saxony. Its major cities were destroyed and a third of the population killed by the war and The plague during the Great Northern War, a plague outbreak in 1702-13. The Swedes finally withdrew from Poland and invaded Ukraine, where they were defeated by the Russians Battle of Poltava, at Poltava. Augustus was able to reclaim his throne with Russian support, but Tsar

Peter the Great

Peter I (, ;

– ), better known as Peter the Great, was the Sovereign, Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia, Tsar of all Russia from 1682 and the first Emperor of Russia, Emperor of all Russia from 1721 until his death in 1725. He reigned j ...

decided to annex

Livonia

Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia.

By the end of the 13th century, the name was extende ...

in 1710. He also suppressed the Cossacks, who had been in revolt against Poland since 1699. Later on, the Tsar frustrated an attempt by Prussia to gain territory from Poland (despite Augustus' approval of this). After the Great Northern War, Poland became an effective protectorate of Russia for the rest of the 18th century. The wide-ranging European War of the Polish Succession, named after the conflict over the succession to

Augustus II

Augustus II the Strong (12 May 1670 – 1 February 1733), was Elector of Saxony from 1694 as well as King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1697 to 1706 and from 1709 until his death in 1733. He belonged to the Albertine branch of the H ...

, was fought from 1733–1735.

In the 18th century, the powers of the monarchy and the central administration became mostly formal. Kings were denied opportunity to provide for elementary requirements of defense and finance, and magnate, aristocratic clans made treaties directly with foreign sovereigns. Attempts at reform were stymied by the determination of ''szlachta'' to preserve their "Golden Liberty, golden freedoms", most notably the ''liberum veto''. Because of the chaos sown by the veto provision, under

Augustus III

Augustus III (; – "the Saxon"; ; 17 October 1696 5 October 1763) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1733 until 1763, as well as Elector of Saxony in the Holy Roman Empire where he was known as Frederick Augustus II ().

He w ...

(1733–63) only one of the thirteen sejm sessions ran to an orderly adjournment.

Unlike Spain and Sweden, great powers that were allowed to settle peacefully into secondary status at the periphery of Europe at the end of their time of glory, Poland endured its decline at the strategic crossroads of the continent. Lacking central leadership and impotent in foreign relations, Poland-Lithuania became a chattel of the ambitious kingdoms that surrounded it, an immense but feeble buffer state. During the reign of Peter the Great (1682–1725), the Commonwealth fell under the dominance of Russia, and by the middle of the 18th century Poland-Lithuania had been made a virtual protectorate of its Russian Empire, eastern neighbor, retaining only a theoretical right to self-rule.

By the 18th century, outside commentators routinely ridiculed the ineffectiveness of sejms, blaming the ''liberum veto''. Throughout Europe political commentators unanimously called it a terrible failure. Many Polish nobles regarded the veto as a constructive instrument, to be used as a weapon against the presumably tyrannical aspirations of the monarchy. The long-term result was a weak state that could not compete with its neighbors, especially Prussia and Russia. Inevitably Poland was partitioned among them and the nobles lost all their political rights as well as their nation state.

Several decades before the loss independence, intellectuals began to reconsider the role of the veto and the nature of Polish liberty, arguing that Poland had not been progressing as fast as the rest of Europe because of a lack of political stability. The exposure to Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment ideas gave Poles further reason to reconsider concepts such as society and equality, and this led to discovery of the idea of the ''naród'', or nation; a nation in which all people, not just the nobility, should enjoy the rights of political liberty. The reform movement came too late to save the state, but helped to form the coherent nation, able to survive the long period of History of Poland (1795–1918), Partitioned Poland.

Commonwealth–Saxony personal union

After

John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( (); (); () 17 August 1629 – 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobieski was educated at the Jagiellonian University and toured Eur ...

's death, the Polish-Lithuanian throne was occupied for seven decades by the German Prince-elector of Electorate of Saxony, Saxony, Augustus II the Strong, and his son,

Augustus III

Augustus III (; – "the Saxon"; ; 17 October 1696 5 October 1763) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1733 until 1763, as well as Elector of Saxony in the Holy Roman Empire where he was known as Frederick Augustus II ().

He w ...

, of the House of Wettin.

Augustus II the Strong (1697–1706, 1709–1733)

Augustus II the Strong, also known as Frederick Augustus I, was an over-ambitious ruler. In the contest for the crown of the Commonwealth he defeated his main rival, François Louis, Prince of Conti, who was supported by France, and King John III Sobieski, John III's son, James Louis Sobieski, Jakub. To ensure his success in becoming the Polish king he converted from Lutheranism to Roman Catholicism. Augustus II virtually bought the election. Augustus hoped to make the Polish throne hereditary for the House of Wettin, and to use his resources as Elector of Saxony to impose some order on the chaotic Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. However, he was soon distracted from his internal reform projects and became preoccupied by the possibility of external conquests.

In alliance with

Peter the Great

Peter I (, ;

– ), better known as Peter the Great, was the Sovereign, Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia, Tsar of all Russia from 1682 and the first Emperor of Russia, Emperor of all Russia from 1721 until his death in 1725. He reigned j ...

of Russia, Augustus won back Podolia and western Ukraine and concluded the long series of Polish-Turkish wars by the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699). A Cossack revolt that had begun in 1699 was suppressed by the Russians. Augustus tried unsuccessfully to regain the Baltic coast from Charles XII of Sweden. He allied with Denmark and Russia, provoking a Great Northern War, war with Sweden. After Augustus' allies were defeated, Sweden's king Charles XII marched from

Livonia

Livonia, known in earlier records as Livland, is a historical region on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. It is named after the Livonians, who lived on the shores of present-day Latvia.

By the end of the 13th century, the name was extende ...

into Poland, using it then as the base of his operations. Installing a puppet ruler (King Stanisław Leszczyński) in Warsaw, he occupied Saxony and drove Augustus II from the throne. Augustus was forced to cede the crown from 1704 to 1709, but regained it when Tsar Peter defeated Charles XII at the Battle of Poltava (1709). Poland, which after having suffered extensive damages from wars had only recently returned to its 1650 population level, was once again completely razed to the ground by the armies of Sweden, Saxony, and Russia. Two million people died as a result of the war and disease epidemics. Cities were reduced to rubble, and cultural losses were immense. After the Swedish defeat Augustus II regained the throne with Russian backing, but the Russians proceeded to annex Livonia after driving the Swedes from it.

Augustus II was helpless when, in 1701, the Elector of Brandenburg-Prussia, Brandenburg proclaimed himself sovereign "King in Prussia," as Frederick I of Prussia, Frederick I and founded the aggressive, militaristic Prussian state, which would eventually form nucleus of a united Germany. The victor from Poltava, Tsar Peter the Great declared Russia to be the guardian of the Polish-Lithuanian Republic's territorial integrity. This effectively meant that the Commonwealth became a Russian protectorate; it had remained in this condition for the duration of its existence (until 1795). The policy of Russian Empire, Russia was to exercise political control over Poland in cooperation with Habsburg monarchy, Austria and Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia.

Stanisław Leszczyński (1706–1709, 1733–1736)

Seen as a puppet of Sweden during his first stint on the throne, Stanisław Leszczyński ruled in times of turmoil, and Augustus II soon recovered the throne, forcing him into exile. He was elected king again following the death of Augustus in 1733, with the support of France and Polish nobles, but not of Poland's neighbors. After the military intervention by Russian and Saxon troops, he was Siege of Danzig (1734), besieged in Danzig (Gdańsk), and again forced to leave the country. For the rest of his life Leszczyński became a successful and popular ruler in the Duchy of Lorraine.

August III (1733–1763)

Also Elector of Saxony (as Frederick Augustus II),

Augustus III

Augustus III (; – "the Saxon"; ; 17 October 1696 5 October 1763) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1733 until 1763, as well as Elector of Saxony in the Holy Roman Empire where he was known as Frederick Augustus II ().

He w ...