History Of Phoenicia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Phoenicia was an ancient Semitic-speaking

Certain scholars suggest there is enough evidence for a Semitic dispersal to the fertile crescent circa 2500 BC. By contrast, other scholars, such as

Certain scholars suggest there is enough evidence for a Semitic dispersal to the fertile crescent circa 2500 BC. By contrast, other scholars, such as

According to the

According to the

Byblos and Sidon were the earliest powers, though the relative prominence of Phoenician city states would ebb and flow throughout the millennium. Other major cities were Tyre,

Byblos and Sidon were the earliest powers, though the relative prominence of Phoenician city states would ebb and flow throughout the millennium. Other major cities were Tyre,

In 539 BC,

In 539 BC,  Nevertheless, during the Persian era, many Phoenicians left to settle elsewhere in the Mediterranean, particularly farther west; Carthage was a popular destination, as by this point it was an established and prosperous empire spanning northwest Africa, Iberia, and parts of Italy. Indeed, the Phoenicians continued to show solidarity to their former colony-turned-empire, with Tyre going so far as to defy the order of King

Nevertheless, during the Persian era, many Phoenicians left to settle elsewhere in the Mediterranean, particularly farther west; Carthage was a popular destination, as by this point it was an established and prosperous empire spanning northwest Africa, Iberia, and parts of Italy. Indeed, the Phoenicians continued to show solidarity to their former colony-turned-empire, with Tyre going so far as to defy the order of King

thalassocratic

A thalassocracy or thalattocracy sometimes also maritime empire, is a state with primarily maritime realms, an empire at sea, or a seaborne empire. Traditional thalassocracies seldom dominate interiors, even in their home territories. Examples ...

civilization that originated in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

. At its height between 1100 and 200 BC, Phoenician civilization spread across the Mediterranean, from Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

to the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

.

The Phoenicians came to prominence following the collapse of most major cultures during the Late Bronze Age. They developed an expansive maritime trade network that lasted over a millennium, becoming the dominant commercial power for much of classical antiquity. Phoenician trade also helped facilitate the exchange of cultures, ideas, and knowledge between major cradles of civilization

A cradle of civilization is a location and a culture where civilization was created by mankind independent of other civilizations in other locations. The formation of urban settlements (cities) is the primary characteristic of a society that c ...

such as Greece, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. After its zenith in the 9th century BC, Phoenician civilization in the eastern Mediterranean slowly declined in the face of foreign influence and conquest, though its presence would remain in the central and western Mediterranean until the second century BC.

Phoenician civilization was organized in city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s, similar to those of ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, of which the most notable were Tyre, Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

, and Byblos

Byblos ( ; gr, Βύβλος), also known as Jbeil or Jubayl ( ar, جُبَيْل, Jubayl, locally ; phn, 𐤂𐤁𐤋, , probably ), is a city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. It is believed to have been first occupied between 880 ...

. Each city-state was politically independent, and there is no evidence the Phoenicians viewed themselves as a single nationality. Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, a Phoenician settlement in northwest Africa, became a major civilization in its own right in the 7th century BC.

Since little has survived of Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

n records or literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

, most of what is known about their origins and history comes from the accounts of other civilizations and inferences from their material culture

Material culture is the aspect of social reality grounded in the objects and architecture that surround people. It includes the usage, consumption, creation, and trade of objects as well as the behaviors, norms, and rituals that the objects creat ...

excavated throughout the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

. Little was written about the Phoenicians in the early modern period, until the 1646 publication of Samuel Bochart

Samuel Bochart (30 May 1599 – 16 May 1667) was a French Protestant biblical scholar, a student of Thomas Erpenius and the teacher of Pierre Daniel Huet. His two-volume '' Geographia Sacra seu Phaleg et Canaan'' (Caen 1646) exerted a profound in ...

's '' Geographia Sacra seu Phaleg et Canaan'', the first full-length book devoted to the subject. It created a framework narrative for future scholars of a maritime-based trading society with linguistic and philological influence across the region. However, early scholars like Bochart presented the Phoenicians as merchants and colonists from the same region, rather than a fully-fledged ethnocultural group. Knowledge of the Phoenicians at this time was confined to the ancient Greco-Roman sources.

Scholarly interest increased in 1758, when Jean-Jacques Barthélémy Jean-Jacques is a French name, equivalent to "John James" in English. Since the second half of 18th century, Jean Jacques Rousseau was widely known as Jean Jacques. Notable people bearing this name include:

Given name

* Jean-Jacques Annaud (born 19 ...

deciphered the Phoenician alphabet

The Phoenician alphabet is an alphabet (more specifically, an abjad) known in modern times from the Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions found across the Mediterranean region. The name comes from the Phoenician civilization.

The Phoenician alpha ...

, and the number of known Phoenician inscriptions

The Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, also known as Northwest Semitic inscriptions, are the primary extra-Biblical source for understanding of the society and history of the ancient Phoenicians, Ancient Hebrews, Hebrews and Arameans. Semitic ins ...

began to increase – the 1694 publication of the Cippi of Melqart

The Cippi of Melqart are a pair of Phoenician marble cippi that were unearthed in Malta under undocumented circumstances and dated to the 2nd century BC. These are votive offerings to the god Melqart, and are inscribed in two languages, Ancien ...

was the first Phoenician inscription to be identified and published in modern times. In 1837, Wilhelm Gesenius

Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm Gesenius (3 February 178623 October 1842) was a German orientalist, lexicographer, Christian Hebraist, Lutheran theologian, Biblical scholar and critic.

Biography

Gesenius was born at Nordhausen. In 1803 he became a s ...

published the first full compendium of the Phoenician language (''Scripturae Linguaeque Phoeniciae Monumenta''), after which Franz Karl Movers Franz Karl Movers (July 17, 1806 – September 28, 1856), German Roman Catholic divine and Orientalist, was born at Koesfeld in Westphalia.

Life

He studied theology and Oriental languages at Münster, was parish priest at Berkum near Bonn fro ...

published ''Die Phönizier'' (1841–1850) and ''Phönizische Texte, erklärt'' (1845–1847), collecting the classical and biblical sources, in which he presented the Phoenician “people” (''Völkerschaft'') as an ethnic group. Further 19th century scholarly works included: John Kenrick’s ''Phoenicia'' (1855), George Rawlinson

George Rawlinson (23 November 1812 – 6 October 1902) was a British scholar, historian, and Christian theologian.

Life

Rawlinson was born at Chadlington, Oxfordshire, the son of Abram Tysack Rawlinson and the younger brother of the famous A ...

's ''History of Phoenicia'' (1889) and Richard Pietschmann

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'strong ...

's ''Geschichte der Phönizier'' (also 1889). This scholarly study of the Phoenicians was first consolidated by Ernest Renan

Joseph Ernest Renan (; 27 February 18232 October 1892) was a French Orientalist and Semitic scholar, expert of Semitic languages and civilizations, historian of religion, philologist, philosopher, biblical scholar, and critic. He wrote influe ...

, first with his French-government-sponsored '' Mission de Phénicie'' – considered a smaller-scale follow up to the Napoleonic era ''Description de l'Égypte

The ''Description de l'Égypte'' ( en, Description of Egypt) was a series of publications, appearing first in 1809 and continuing until the final volume appeared in 1829, which aimed to comprehensively catalog all known aspects of ancient and m ...

'' – and then with the ''Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum

The ("Corpus of Semitic Inscriptions", abbreviated CIS) is a collection of ancient inscriptions in Semitic languages produced since the end of 2nd millennium BC until the rise of Islam. It was published in Latin. In a note recovered after his de ...

''.

The scholarly consensus is that the Phoenicians' period of greatest prominence was 1200 BC to the end of the Persian period (332 BC). The Phoenician Early Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

is largely unknown. The two most important sites are Byblos

Byblos ( ; gr, Βύβλος), also known as Jbeil or Jubayl ( ar, جُبَيْل, Jubayl, locally ; phn, 𐤂𐤁𐤋, , probably ), is a city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. It is believed to have been first occupied between 880 ...

and Sidon-Dakerman (near Sidon), although, as of 2021, well over a hundred sites remain to be excavated, while others that have been are yet to be fully analysed. The Middle Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

was a generally peaceful time of increasing population, trade, and prosperity, though there was competition for natural resources. In the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, rivalry between Egypt, the Mittani, the Hittites, and Assyria had a significant impact on Phoenicians cities.

Origins

Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

believed that the Phoenicians originated from Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ...

, a view shared centuries later by the historian Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

. This theory was accepted by the 19th-century German classicist Arnold Heeren

Arnold Hermann Ludwig Heeren (25 October 1760, Arbergen6 March 1842, Göttingen) was a German historian. He was a member of the Göttingen School of History.

Biography

Heeren was born on 25 October 1760 in Arbergen near Bremen, a small village i ...

, who noted that Greek geographers described "two islands, named Tyrus or Tylos

Tylos ( grc, Τύλος) was the Greek exonym of ancient Bahrain in the classical era, during which the island was a center of maritime trade and pearling in the Eurythraean Sea.Curtis E. Larsen, ''Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The ...

, and Aradus

''Aradus'' is a genus of true bugs in the family Aradidae, the flat bugs. It is distributed worldwide, mainly in the Holarctic.Larivière, M. C. and A. Larochelle. (2006)An overview of flat bug genera (Hemiptera, Aradidae) from New Zealand, wit ...

, which boasted that they were the mother country of the Phoenicians, and exhibited relics of Phoenician temples." The people of modern Tyre in Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

, have particularly long maintained Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Persis, Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a Mediterranean sea (oceanography), me ...

origins, and the similarity in the words "Tylos" and "Tyre" has been commented upon. The Dilmun

Dilmun, or Telmun, ( Sumerian: , later 𒉌𒌇(𒆠), ni.tukki = DILMUNki; ar, دلمون) was an ancient East Semitic-speaking civilization in Eastern Arabia mentioned from the 3rd millennium BC onwards.

Based on contextual evidence, it was l ...

civilization thrived in Bahrain during the period 2200–1600 BC, as shown by excavations of settlements and the Dilmun burial mounds

The Dilmun Burial Mounds ( ar, مدافن دلمون) are a UNESCO World Heritage Site comprising necropolis areas on the main island of Bahrain dating back to the Dilmun and the Umm al-Nar culture.

Bahrain has been known since ancient times ...

. However, some scholars note that there is little evidence Bahrain was occupied during the time when such migration had supposedly taken place. Genetic research from 2017 showed that "present-day Lebanese derive most of their ancestry from a Canaanite-related population, which therefore implies substantial genetic continuity in the Levant since at least the Bronze Age" based on ancient DNA samples from skeletons found in modern-day Lebanon. However, this study did not look at Arabian genetic history, and an even more recent study highlighted the high relatedness of Arabians with coastal Levantines, showing that Arabian hunter-gatherers derive most of their ancestry from Neolithic Levantines, and that modern inhabitants of the UAE derive a greater amount of their ancestry from Neolithic Levantines than do modern Levantines. While modern Lebanese derive over 90% of their ancestry from Bronze Age Sidonians, Emiratis derive 75% of their DNA from Bronze Age Sidon in Lebanon and 25% from Arabian hunter-gatherers who were highly related to the Natufians, or Neolithic Levantines. Therefore any back-migration of Arabians to the Levant is difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish genetically.

Certain scholars suggest there is enough evidence for a Semitic dispersal to the fertile crescent circa 2500 BC. By contrast, other scholars, such as

Certain scholars suggest there is enough evidence for a Semitic dispersal to the fertile crescent circa 2500 BC. By contrast, other scholars, such as Sabatino Moscati

Sabatino Moscati (24 November 1922 – 8 September 1997) was an Italian archaeologist and linguist known for his work on Phoenician and Punic civilizations. In 1954 he became Professor of Semitic Philology at the University of Rome where he es ...

, believe the Phoenicians originated from an admixture of previous non-Semitic inhabitants with the Semitic arrivals. However, in reality, the ethnogenesis of the Canaanites, and more specifically, Phoenicians, is much more complex.

The Canaanite culture that gave rise to the Phoenicians apparently developed ''in situ'' from the earlier Ghassulian

Ghassulian refers to a culture and an archaeological stage dating to the Middle and Late Chalcolithic Period in the Southern Levant (c. 4400 – c. 3500 BC). Its type-site, Teleilat Ghassul (Teleilat el-Ghassul, Tulaylat al-Ghassul), is loca ...

chalcolithic

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', "copper" and ''líthos'', "stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin '' aeneus'' "of copper"), is an archaeological period characterized by regular ...

culture. Ghassulian itself developed from the Circum-Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex, which in turn developed from a fusion of their ancestral Natufian

The Natufian culture () is a Late Epipaleolithic archaeological culture of the Levant, dating to around 15,000 to 11,500 years ago. The culture was unusual in that it supported a sedentary or semi-sedentary population even before the introduction ...

and Harifian

Harifian is a specialized regional cultural development of the Epipalaeolithic of the Negev Desert. It corresponds to the latest stages of the Natufian culture.

History

Like the Natufian, Harifian is characterized by semi-subterranean houses ...

cultures with Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is part of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, a Neolithic culture centered in upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, dating to years ago, that is, 8800–6500 BC. It was typed by British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon during h ...

(PPNB) farming cultures, practicing the domestication of animals

The domestication of animals is the mutual relationship between non-human animals and the humans who have influence on their care and reproduction.

Charles Darwin recognized a small number of traits that made domesticated species different from t ...

during the 6200 BC climatic crisis, which led to the Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, or the (First) Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period from a lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and settlement, making an incre ...

in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

. Byblos

Byblos ( ; gr, Βύβλος), also known as Jbeil or Jubayl ( ar, جُبَيْل, Jubayl, locally ; phn, 𐤂𐤁𐤋, , probably ), is a city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. It is believed to have been first occupied between 880 ...

is attested as an archaeological site from the Early Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

. The Late Bronze Age state of Ugarit

)

, image =Ugarit Corbel.jpg

, image_size=300

, alt =

, caption = Entrance to the Royal Palace of Ugarit

, map_type = Near East#Syria

, map_alt =

, map_size = 300

, relief=yes

, location = Latakia Governorate, Syria

, region = F ...

is considered quintessentially Canaanite archaeologically,Tubb, Jonathan N. (1998), "Canaanites" (British Museum People of the Past) even though the Ugaritic language does not belong to the Canaanite languages

The Canaanite languages, or Canaanite dialects, are one of the three subgroups of the Northwest Semitic languages, the others being Aramaic and Ugaritic, all originating in the Levant and Mesopotamia. They are attested in Canaanite inscription ...

proper.

. .

Emergence during the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 BC)

In the early 16th century BC, Egypt ejected foreign rulers known as theHyksos

Hyksos (; Egyptian '' ḥqꜣ(w)- ḫꜣswt'', Egyptological pronunciation: ''hekau khasut'', "ruler(s) of foreign lands") is a term which, in modern Egyptology, designates the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt (fl. c. 1650–1550 BC).

T ...

, a diverse group of peoples from the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

, and re-established native dynastic rule under the New Kingdom

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

. This precipitated Egypt's incursion into the Levant, with a particular focus on Phoenicia; the first known account of the Phoenicians relates to the conquests of Thutmose III

Thutmose III (variously also spelt Tuthmosis or Thothmes), sometimes called Thutmose the Great, was the sixth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Officially, Thutmose III ruled Egypt for almost 54 years and his reign is usually dated from 28 ...

(1479–1425 BC). Coastal cities such as Byblos, Arwad, and Ullasa were targeted for their crucial geographic and commercial links with the interior (via the Nahr al-Kabir

The Nahr al-Kabir, also known in Syria as al-Nahr al-Kabir al-Janoubi ( ar, النهر الكبير الجنوبي, lit=the southern great river, by contrast with the Nahr al-Kabir al-Shamali) or in Lebanon simply as the Kebir, is a river in Syria ...

and the Orontes rivers). The cities provided Egypt with access to Mesopotamian trade as well as abundant stocks of the region's native cedar wood, of which there was no equivalent in the Egyptian homeland. Thutmose III reports stocking Phoenician harbors with timber for annual shipments, as well as constructing ships for inland trade through the Euphrates River.

Amarna Letters

The Amarna letters (; sometimes referred to as the Amarna correspondence or Amarna tablets, and cited with the abbreviation EA, for "El Amarna") are an archive, written on clay tablets, primarily consisting of diplomatic correspondence between t ...

, a series of correspondences between Egypt and Phoenicia from 1411 to 1358 BC, by the mid 14th century, most of Phoenicia, along with parts of the Levant, came under a "loosely defined" Egyptian administrative framework. The Phoenician city states were considered "favored cities" to the Egyptians, helping anchor Egypt's access to resources and trade. Tyre, Sidon, Beirut, and Byblos were regarded as the most important. Though nominally under Egyptian rule, the Phoenicians had considerable autonomy and their cities were fairly well developed and prosperous. They are described as having their own established dynasties, political assemblies, and merchant fleets, even engaging in political and commercial competition amongst themselves. Byblos was evidently the leading city outside Egypt proper, accounting for most of the Amarna communications. It was a major center of bronze-making, and the primary terminus of precious goods such as tin and lapis lazuli from as far east as Afghanistan. Sidon and Tyre also commanded interest among Egyptian officials, beginning a pattern of rivalry that would span the next millennium.

The economic dynamism of Egypt's Eighteenth Dynasty, particularly under its ninth pharaoh, Amenhotep III

Amenhotep III ( egy, jmn-ḥtp(.w), ''Amānəḥūtpū'' , "Amun is Satisfied"; Hellenized as Amenophis III), also known as Amenhotep the Magnificent or Amenhotep the Great, was the ninth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. According to different ...

(1391–1353 BC), brought further prosperity and prominence to the Phoenician cities. There was growing demand for a wide array of goods, though timber remained the principal commodity: Egypt's expanding shipbuilding industry and rapid construction of temples and estates were a driving force of the economy; cedar was the wood of choice for the coffins of the priestly and upper class. Initially dominated by Byblos, virtually every city had access to a variety of hardwood, with the notable exception of Tyre. Every city saw an influx of wealth and a more diversified economy that included loggers, artisans, traders, and sailors.

Hittite intervention and Late Bronze Age collapse

The Amarna letters report that from 1350 to 1300 BC, neighboringAmorites

The Amorites (; sux, 𒈥𒌅, MAR.TU; Akkadian language, Akkadian: 𒀀𒈬𒊒𒌝 or 𒋾𒀉𒉡𒌝/𒊎 ; he, אֱמוֹרִי, 'Ĕmōrī; grc, Ἀμορραῖοι) were an ancient Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic-speaking people ...

and Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian people who played an important role in establishing first a kingdom in Kussara (before 1750 BC), then the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom (c. 1750–1650 BC), and next an empire centered on Hattusa in north-centra ...

were capturing Phoenician cities, especially in the north. Egypt subsequently lost its coastal holdings from Ugarit in northern Syria to Byblos near central Lebanon. The southern Phoenician cities appeared to have remained autonomous, though under Seti I

Menmaatre Seti I (or Sethos I in Greek) was the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom period, ruling c.1294 or 1290 BC to 1279 BC. He was the son of Ramesses I and Sitre, and the father of Ramesses II.

The ...

(1306–1290 BC) Egypt reaffirmed its control.

Some time between 1200 and 1150 BC, the Late Bronze Age collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse was a time of widespread societal collapse during the 12th century BC, between c. 1200 and 1150. The collapse affected a large area of the Eastern Mediterranean (North Africa and Southeast Europe) and the Near East ...

severely weakened or destroyed most civilizations in the region, including the Egyptians and Hittites.

Ascendance and high point (1200–800 BC)

The Phoenicians, now free from foreign domination and interference, appeared to have weathered the crisis relatively well, emerging as a distinct and organized civilization in 1230 BC, shortly after the approximate transition to theIron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

(c. 1200–500 BC). For the next several centuries, Phoenicia was prosperous, and the period is sometimes described as a "Phoenician renaissance." They filled the power vacuum caused by the Late Bronze Age collapse by becoming the sole mercantile and maritime power in the region, a status they would maintain for the next several centuries.

Byblos and Sidon were the earliest powers, though the relative prominence of Phoenician city states would ebb and flow throughout the millennium. Other major cities were Tyre,

Byblos and Sidon were the earliest powers, though the relative prominence of Phoenician city states would ebb and flow throughout the millennium. Other major cities were Tyre, Simyra

Tell Kazel ( ar, تل الكزل, translit=Tall al-Kazil) is an oval-shaped tell that measures at its base, narrowing to at its top. It is located in the Safita district of the Tartus Governorate in Syria in the north of the Akkar plain on th ...

, Arwad

Arwad, the classical Aradus ( ar, أرواد), is a town in Syria on an eponymous island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is the administrative center of the Arwad Subdistrict (''nahiyah''), of which it is the only locality.Berytus

) or Laodicea in Canaan (2nd century to 64 BCE)

, image = St. George's Cathedral, Beirut.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Roman ruins of Berytus, in front of Saint George Greek Orthodox Cathedral in moder ...

, all of which appeared in the Amarna tablets of the mid-second millennium BC. Byblos

Byblos ( ; gr, Βύβλος), also known as Jbeil or Jubayl ( ar, جُبَيْل, Jubayl, locally ; phn, 𐤂𐤁𐤋, , probably ), is a city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. It is believed to have been first occupied between 880 ...

was initially the main point from which the Phoenicians dominated the Mediterranean and Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

routes. It was here that the first inscription in the Phoenician alphabet was found, on the sarcophagus of King Ahiram

The Ahiram sarcophagus (also spelled Ahirom, in Phoenician) was the sarcophagus of a Phoenician King of Byblos (c. 850 BC), discovered in 1923 by the French excavator Pierre Montet in tomb V of the royal necropolis of Byblos.

The sarcophagus is ...

(c. 850 BC). Phoenicia's independent coastal cities were ideally suited for trade between the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

area, which was rich in natural resources, and the rest of the ancient world.

Early into the Iron Age, the Phoenicians established ports, warehouses, markets, and settlement all across the Mediterranean and up to the southern Black Sea. Initially led by Tyre, colonies were established on Cyprus, Sardinia, the Balearic Islands, Sicily, and Malta, as well as the fertile coasts of North Africa and the mineral rich Iberian Peninsula. Though disputed, some scholars believe Carthage, which would later emerge as a major power in the western Mediterranean, was founded during the reign of Pygmalion

Pygmalion or Pigmalion may refer to:

Mythology

* Pygmalion (mythology), a sculptor who fell in love with his statue

Stage

* ''Pigmalion'' (opera), a 1745 opera by Jean-Philippe Rameau

* ''Pygmalion'' (Rousseau), a 1762 melodrama by Jean-Jacques ...

of Tyre (831–735 BC). The Phoenician's complex mercantile network supported what Fernand Braudel

Fernand Braudel (; 24 August 1902 – 27 November 1985) was a French historian and leader of the Annales School. His scholarship focused on three main projects: ''The Mediterranean'' (1923–49, then 1949–66), ''Civilization and Capitalism'' ...

calls an early example of a "world-economy", described as "an economically autonomous section of the planet able to provide for most of its own needs" due to links and exchanges provided by the Phoenicians.

A unique concentration in Phoenicia of silver hoards dated some time during its high point contains hacksilver

Hacksilver (sometimes referred to as hacksilber) consists of fragments of cut and bent silver items that were used as bullion or as currency by weight in antiquity.

Use

Hacksilver was common among the Norsemen or Vikings, as a result of both t ...

(used for currency) that bears lead isotope ratios matching ores in Sardinia and Spain. This metallic evidence indicates the extent of Phoenician trade networks. It also seems to confirm the Biblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

attestation of a western Mediterranean port city, Tarshish

Tarshish ( Phoenician: ''TRŠŠ'', he, תַּרְשִׁישׁ ''Taršīš'', , ''Tharseis'') occurs in the Hebrew Bible with several uncertain meanings, most frequently as a place (probably a large city or region) far across the sea from Phoen ...

, supplying King Solomon

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

of Israel with silver via Phoenicia.

The first textual account of the Phoenicians during the Iron Age comes from Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser I

Tiglath-Pileser I (; from the Hebraic form of akk, , Tukultī-apil-Ešarra, "my trust is in the son of Ešarra") was a king of Assyria during the Middle Assyrian period (1114–1076 BC). According to Georges Roux, Tiglath-Pileser was "one of t ...

, who recorded his campaign against the Phoenicians between 1114 and 1076 BC. Seeking access to the Phoenician's high quality cedar wood, he describes exacting tribute from the leading cities at the time, Byblos and Sidon. Roughly a year later, the Egyptian priest, Wenamun

The Story of Wenamun (alternately known as the Report of Wenamun, The Misadventures of Wenamun, Voyage of Unamūn, or nformallyas just Wenamun) is a literary text written in hieratic in the Late Egyptian language. It is only known from one incomp ...

describes his efforts to procure cedar wood for a religious temple from 1075 to 1060 BC.''The Phoenicians: A Captivating Guide to the History of Phoenicia and the Impact Made by One of the Greatest Trading Civilizations of the Ancient World'', Captivating History (Dec.16, 2019), .Sometimes rendered "Wen-Amon" Contradicting the account of Tiglath-Pileser I, Wenamun describes Byblos and Sidon as impressive and powerful coastal cities, which suggests that the Assyrian siege was ineffectual. Although once vassals of the Egyptians during the Bronze Age, the city states were now able to reject Wenamun's demand for tribute, instead forcing the Egyptians to agree to a commercial arrangement. This indicates the extent to which the Phoenicians had become a more influential and independent people.

The collection of city states constituting Phoenicia came to be characterized by outsiders, and even the Phoenicians themselves, by one of the dominant states at a given time. For many centuries'','' Phoenicians and Canaanites alike were alternatively called ''Sidonians'' or ''Tyrians.'' Throughout much of the 11th century BC, the biblical books of Joshua, Judges, and Samuel use the term Sidonian to describe all Phoenicians; by the 10th century BC, Tyre rose to become the richest and most powerful Phoenician city state, particularly during the reign of Hiram I (c. 969–936 BC). Described in the Jewish Bible as a contemporary of kings David and Solomon of Israel, he is best known for being commissioned to build Solomon's Temple, where the skill and wealth of his city state is noted. Overall, the Old Testament references Phoenician city states—namely Sidon, Tyre, Arvad (Awad) and Byblos—over 100 times, indicating the extent to which Tyrian and Phoenician culture was recognized.

Indeed, the Phoenicians stood out from their contemporaries in that their rise was relatively peaceful. As archaeologist James B. Pritchard notes, "They became the first to provide a link between the culture of the ancient Near East and that of the uncharted world of the West…They went not for conquest as the Babylonians and Assyrians did, but for trade. Profit rather than plunder was their policy." Pritchard observes that even the Israelites, who were in conflict with virtually every neighboring culture, seemed to regard the Phoenicians as "respected neighbors with whom Israel was able to maintain amicable diplomatic and commercial relations throughout a span of a half millennium … Yet despite the ideological differences between Israel and her northern neighbors, detente prevailed."

During the rule of the priest Ithobaal (887–856 BC), Tyre expanded its territory as far north as Beirut (incorporating its erstwhile rival Sidon) and into part of Cyprus; this unusual act of aggression was the closest the Phoenicians ever came to forming a unitary territorial state. Tellingly, once his realm reached its greatest territorial extent, Ithobaal declared himself "King of the Sidonians", a title that would be used by his successors and mentioned in both Greek and Jewish accounts.

Phoenician alphabet

During their high point, specifically around 1050 BC, the Phoenicians developed a script for writing Phoenician, a Northern Semitic language. They were among the first state-level societies to make extensive use ofalphabet

An alphabet is a standardized set of basic written graphemes (called letters) that represent the phonemes of certain spoken languages. Not all writing systems represent language in this way; in a syllabary, each character represents a syll ...

s. The family of Canaanite languages

The Canaanite languages, or Canaanite dialects, are one of the three subgroups of the Northwest Semitic languages, the others being Aramaic and Ugaritic, all originating in the Levant and Mesopotamia. They are attested in Canaanite inscription ...

, spoken by Israelites, Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient thalassocracy, thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-st ...

, Amorites

The Amorites (; sux, 𒈥𒌅, MAR.TU; Akkadian language, Akkadian: 𒀀𒈬𒊒𒌝 or 𒋾𒀉𒉡𒌝/𒊎 ; he, אֱמוֹרִי, 'Ĕmōrī; grc, Ἀμορραῖοι) were an ancient Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic-speaking people ...

, Ammon

Ammon (Ammonite: 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''ʻAmān''; he, עַמּוֹן ''ʻAmmōn''; ar, عمّون, ʻAmmūn) was an ancient Semitic-speaking nation occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Arnon and Jabbok, in p ...

ites, Moabites and Edomites

Edom (; Edomite: ; he, אֱדוֹם , lit.: "red"; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Egyptian: ) was an ancient kingdom in Transjordan, located between Moab to the northeast, the Arabah to the west, and the Arabian Desert to the south and east.N ...

, was the first historically attested group of languages to use an alphabet to record their writings, based on the Proto-Canaanite

Proto-Canaanite is the name given to

:(a) the Proto-Sinaitic script when found in Canaan, dating to about the 17th century BC and later.

:(b) a hypothetical ancestor of the Phoenician script before some cut-off date, typically 1050 BCE, with an u ...

script. The Proto-Canaanite script, which is derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1,00 ...

, uses around 30 symbols but was not widely used until the rise of new Semitic kingdoms in the 13th and 12th centuries BC.

The Canaanite-Phoenician alphabet

An alphabet is a standardized set of basic written graphemes (called letters) that represent the phonemes of certain spoken languages. Not all writing systems represent language in this way; in a syllabary, each character represents a syll ...

consists of 22 letters, all consonant

In articulatory phonetics, a consonant is a speech sound that is articulated with complete or partial closure of the vocal tract. Examples are and pronounced with the lips; and pronounced with the front of the tongue; and pronounced wit ...

s. It is believed to be one of the ancestors of modern alphabets. Through their maritime trade, the Phoenicians spread the use of the alphabet to Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, North Africa, and Europe, where it likely served the purpose of communication and commercial relations. The alphabet was adopted by the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

, who developed it to have distinct letters for vowel

A vowel is a syllabic speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness and also in quantity (leng ...

s as well as consonant

In articulatory phonetics, a consonant is a speech sound that is articulated with complete or partial closure of the vocal tract. Examples are and pronounced with the lips; and pronounced with the front of the tongue; and pronounced wit ...

s.

The name ''Phoenician'' is by convention given to inscriptions beginning around 1050 BC, because Phoenician, Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, and other Canaanite dialects

The Canaanite languages, or Canaanite dialects, are one of the three subgroups of the Northwest Semitic languages, the others being Aramaic and Ugaritic, all originating in the Levant and Mesopotamia. They are attested in Canaanite inscriptions ...

were largely indistinguishable before that time.Markoe (2000) p. 111 The so-called Ahiram epitaph, engraved on the sarcophagus of King Ahiram

The Ahiram sarcophagus (also spelled Ahirom, in Phoenician) was the sarcophagus of a Phoenician King of Byblos (c. 850 BC), discovered in 1923 by the French excavator Pierre Montet in tomb V of the royal necropolis of Byblos.

The sarcophagus is ...

from about 1000 BC, shows a fully developed Phoenician script.The date remains the subject of controversy, according to p. 13. "Most scholars have taken the Ahiram inscription to date from around 1000 B.C.E.", notes Cook analyses and dismisses the date in the thirteenth century adopted by C. Garbini, "Sulla datazione della'inscrizione di Ahiram", ''Annali'' (Istituto Universitario Orientale, Naples) 37 (1977:81–89), which was the prime source for early dating urged in Arguments for a mid 9th-8th century BCE date for the sarcophagus reliefs themselves—and hence the inscription, too—were made on the basis of comparative art history and archaeology by ; and on the basis of paleography among other points by

Peak and gradual decline (900–586 BC)

The Late Iron Age saw the height of Phoenician shipping, mercantile, and cultural activity, particularly between 750 and 650 BC. Phoenician influence was visible in the "Orientalization" of Greek cultural and artistic conventions through Egyptian and Near Eastern influences transmitted by the Phoenician. The infusion of various technological, scientific, and philosophical ideas from all over the region laid the foundations for the emergence of classical Greece in the 5th century BC. The Phoenicians, already well known as peerless mariners and traders, had also developed a distinct and complex culture. They learned to manufacture both common and luxury goods, becoming "renowned in antiquity for clever trinkets mass produced for wholesale consumption."Gerhard Herm, The Phoenicians, trans. Catherine Hiller (New York: William Morrow, 1975), p. 80. They were proficient inglass-making

Glass production involves two main methods – the float glass process that produces sheet glass, and glassblowing that produces bottles and other containers. It has been done in a variety of ways during the history of glass.

Glass container ...

, engraved and chased metalwork (including bronze, iron, and gold), ivory carving, and woodwork. Among their most popular goods were fine textiles, typically dyed with the famed Tyrian purple

Tyrian purple ( grc, πορφύρα ''porphúra''; la, purpura), also known as Phoenician red, Phoenician purple, royal purple, imperial purple, or imperial dye, is a reddish-purple natural dye. The name Tyrian refers to Tyre, Lebanon. It is ...

. Homer's ''Iliad,'' which was composed during this period, references the quality of Phoenician clothing and metal goods. Phoenicians also became the leading producers of glass in the region, with thousands of flasks, beads, and other glassware being shipped across the Mediterranean.Gerhard Herm, ''The Phoenicians'', trans. Catherine Hiller (New York: William Morrow, 1975), p. 80. Colonies in Spain appeared to have utilized the potter's wheel

In pottery, a potter's wheel is a machine used in the shaping (known as throwing) of clay into round ceramic ware. The wheel may also be used during the process of trimming excess clay from leather-hard dried ware that is stiff but malleable, a ...

,Karl Moore and David Lewis, ''Birth of the Multinational'' (Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press, 1999), p. 85. while Carthage, now a nascent city state, utilized serial production

Serial may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media The presentation of works in sequential segments

* Serial (literature), serialised literature in print

* Serial (publishing), periodical publications and newspapers

* Serial (radio and televisio ...

to produce large numbers of ships quickly and cheaply.Piero Bartoloni, “Ships and Navigation,” in The Phoenicians, ed. Sabatino Moscati (New York: Abbeville, 1988), p. 76.

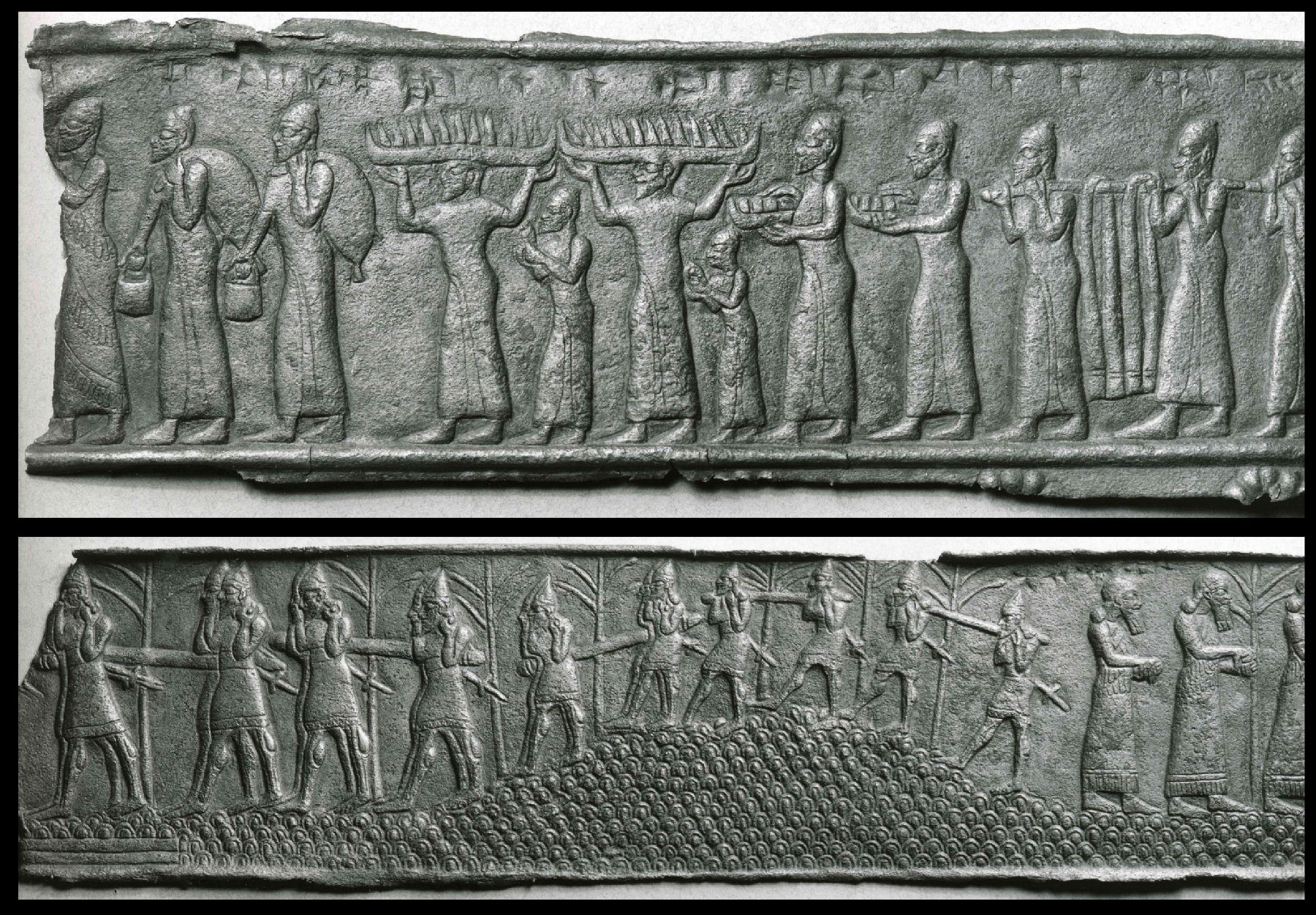

Vassalage under the Assyrians (858–608 BC)

As a mercantile power concentrated along a narrow coastal strip of land, the Phoenicians lacked the size and population to support a large military. Thus, as neighboring empires began to rise, the Phoenicians increasingly fell under the sway of foreign rulers, who to varying degrees circumscribed their autonomy. The Assyrian conquest of Phoenicia began with KingShalmaneser III

Shalmaneser III (''Šulmānu-ašarēdu'', "the god Shulmanu is pre-eminent") was king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Ashurnasirpal II in 859 BC to his own death in 824 BC.

His long reign was a constant series of campai ...

, who rose to power in 858 BC and began a series of campaigns against neighboring states. The Phoenician city states fell under his rule over a period of three years, forced to pay heavy tribute in money, goods, and natural resources. However, the Phoenicians were not annexed outright—they remained in a state of vassalage, subordinate to the Assyrians but allowed a certain degree of freedom. Relative to other conquered peoples in the empire, the Phoenicians were treated well, due to a history of otherwise amicable relations with the Assyrians, and to their importance as a source of income and even diplomacy for the expanding empire.

After the death of Shalmaneser III in 824 BC, the Phoenicians maintained their quasi-independence, as subsequent rulers did not wish to meddle in their internal affairs, lest they deprive their empire of a key source of capital. This changed in 744 BC, with the ascension of Tiglath-Pileser III

Tiglath-Pileser III (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "my trust belongs to the son of Ešarra"), was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 745 BC to his death in 727. One of the most prominent and historically significant Assyrian kings, Tig ...

, who sought to forcefully incorporate surrounding territories rather than keep them subordinate. By 738 BC, most of the Levant, including northern Phoenicia, were annexed and fell directly under Assyrian administration; only Tyre and Byblos, the most powerful of the city states, remained as tributary states outside of direct control.

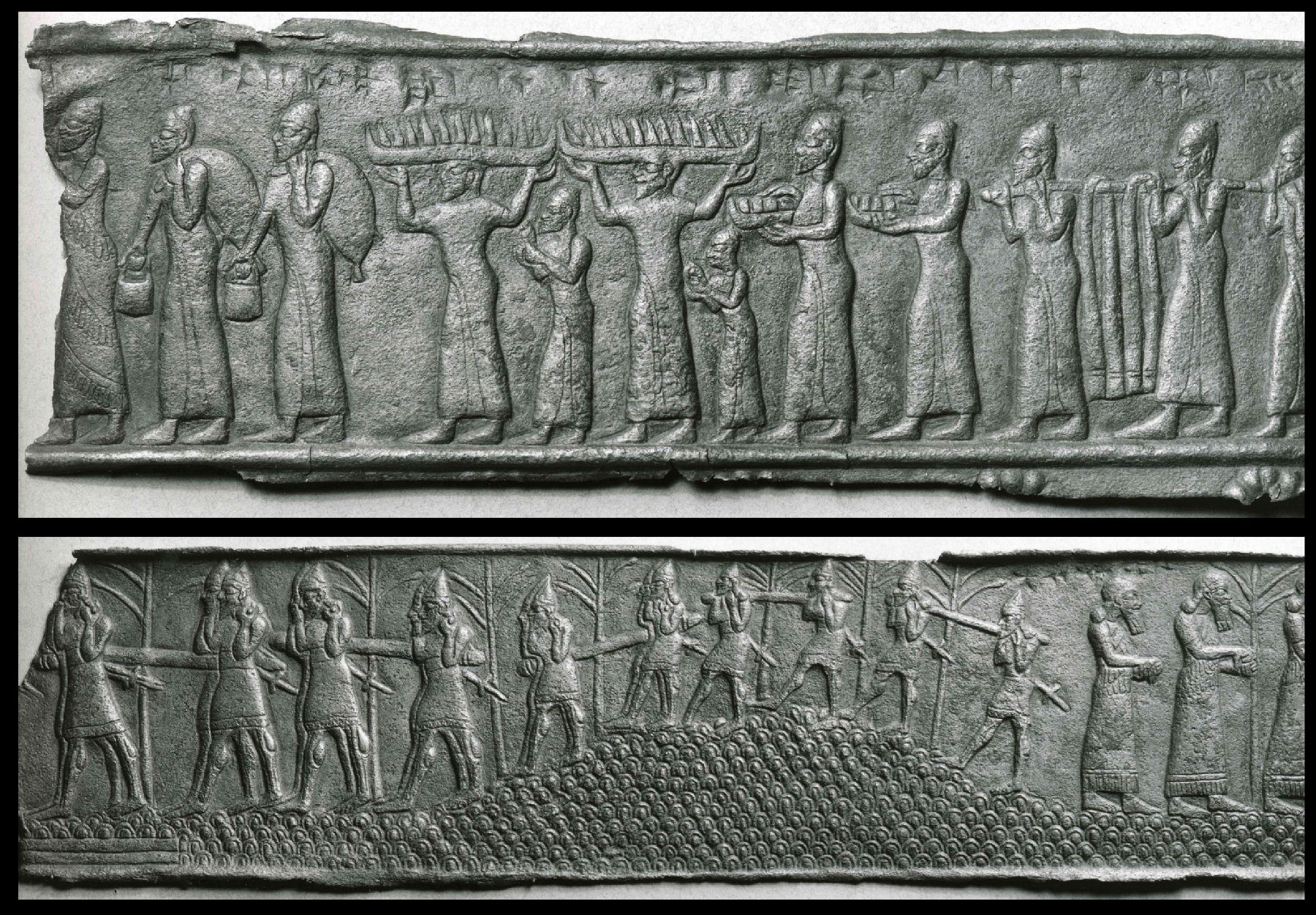

Within years Tyre and Byblos rebelled. Tiglath-Pileser III quickly subdued both cities and imposed heavier tribute. After several years, Tyre rebelled again, this time allying with its erstwhile rival Sidon. After two to three years, Sargon II

Sargon II (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is general ...

(722–705 BC) successfully besieged Tyre in 721 BC and crushed the alliance. In 701 BC, his son and successor Sennacherib

Sennacherib (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynast ...

suppressed further rebellions across the region, reportedly deporting most of Tyre's population to the Assyrian capital of Nineveh. During the 7th century BC, Sidon rebelled and was completely destroyed by Esarhaddon

Esarhaddon, also spelled Essarhaddon, Assarhaddon and Ashurhaddon (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , also , meaning " Ashur has given me a brother"; Biblical Hebrew: ''ʾĒsar-Ḥaddōn'') was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his ...

(681–668 BC), who enslaved its inhabitants and built a new city on its ruins.

While the Phoenicians endured unprecedented repression and conflict, by the end of the 7th century BC., the Assyrians had been weakened by successive revolts throughout their empire, which made led to their destruction by the Iranian Median Empire

The Medes (Old Persian: ; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, the ...

.

Babylonian rule (605–538 BC)

The Babylonians, formerly vassals of the Assyrians, took advantage of the empire's collapse and rebelled, quickly establishing theNeo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the List of kings of Babylon, King of B ...

in its place. The decisive battle of Carchemish

Carchemish ( Turkish: ''Karkamış''; or ), also spelled Karkemish ( hit, ; Hieroglyphic Luwian: , /; Akkadian: ; Egyptian: ; Hebrew: ) was an important ancient capital in the northern part of the region of Syria. At times during its ...

in northern Syria ended the historic hegemony of the Assyrians and their Egyptian allies over the Near East. While Babylonian rule over Phoenicia was brief, it hastened the precipitous decline that began under the Assyrians. Phoenician cities revolted several times throughout the reigns of the first Babylonian king, Nabopolassar

Nabopolassar (Babylonian cuneiform: , meaning "Nabu, protect the son") was the founder and first king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from his coronation as king of Babylon in 626 BC to his death in 605 BC. Though initially only aimed at res ...

(626–605 BC), and his son Nebuchadnezzar II

Nebuchadnezzar II (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling ...

(c. 605–c. 562 BC). The latter's tenure witnessed several regional rebellions, especially in the Levant. After suppressing a revolt in Jerusalem, Nebuchadnezzar besieged the rebellious Tyre, which resisted for thirteen years from 587 to 574 BC. The city ultimately capitulated under "favorable terms".

During the Babylonian period, Tyre briefly became "a republic headed by elective magistrates",Bondi, S.F. (2001), “Political and Administrative Organization,” in Moscati, S. (ed.), The Phoenicians. London: I.B. Tauris. adopting a system of government consisting of a pair of judges, known as ''sufetes'', who were chosen from the most powerful noble families and served short terms.Stephen Stockwell, “Before Athens: Early Popular Government in Phoenician and Greek City States,” Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 2 (2010): 128.

Persian period (539–332 BC)

The conquests of the late Iron Age left the Phoenicians politically and economically weakened, with city states gradually losing their influence and autonomy in the face of growing foreign powers. Nevertheless, during most of the three centuries of vassalage and domination by Mesopotamian powers the Phoenicians generally managed to remain relatively independent and prosperous. Even when conquered, many of the city states continued to flourish, leveraging their role as intermediaries, shipbuilders, and traders for one foreign suzerain or another. This pattern would continue through the roughly two centuries of Persian rule. In 539 BC,

In 539 BC, Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

, king and founder of the Persian Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

, had exploited the unraveling of the Neo-Babylonian Empire and took the capital of Babylon.Jacob Katzenstein, ''Tyre in the Early Persian Period (539-486 B.C.E.)'' The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Winter, 1979), p. 31, www.jstor.org/stable/3209545. As Cyrus began consolidating territories across the Near East, the Phoenicians apparently made the pragmatic calculation of " ieldingthemselves to the Persians." Most of the Levant was consolidated by Cyrus into a single ''satrapy'' (province) and forced to pay a yearly tribute of 350 '' talents,'' which was roughly half the tribute that was required of Egypt and Libya. This continued the trend, which began under the Assyrians, of the Phoenicians being treated with a relatively lighter hand by most rulers.

In fact, the area of Phoenicia was later divided into four vassal kingdoms—Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

, Tyre, Arwad

Arwad, the classical Aradus ( ar, أرواد), is a town in Syria on an eponymous island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is the administrative center of the Arwad Subdistrict (''nahiyah''), of which it is the only locality.Byblos

Byblos ( ; gr, Βύβλος), also known as Jbeil or Jubayl ( ar, جُبَيْل, Jubayl, locally ; phn, 𐤂𐤁𐤋, , probably ), is a city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. It is believed to have been first occupied between 880 ...

—which were allowed considerable autonomy. Unlike in other areas of the empire, including adjacent Jerusalem and Samaria, there is no record of Persian administrators governing the Phoenician city-states. Local Phoenician kings were allowed to remain in power and even given the same rights as Persian ''satraps'' (governors), such as hereditary offices and minting their own coins. The otherwise decentralized nature of Persian administration meant the Phoenicians, though no longer an independent and influential power, could at least continue to conduct their political and mercantile affairs with relative freedom.

Nevertheless, during the Persian era, many Phoenicians left to settle elsewhere in the Mediterranean, particularly farther west; Carthage was a popular destination, as by this point it was an established and prosperous empire spanning northwest Africa, Iberia, and parts of Italy. Indeed, the Phoenicians continued to show solidarity to their former colony-turned-empire, with Tyre going so far as to defy the order of King

Nevertheless, during the Persian era, many Phoenicians left to settle elsewhere in the Mediterranean, particularly farther west; Carthage was a popular destination, as by this point it was an established and prosperous empire spanning northwest Africa, Iberia, and parts of Italy. Indeed, the Phoenicians continued to show solidarity to their former colony-turned-empire, with Tyre going so far as to defy the order of King Cambyses II

Cambyses II ( peo, 𐎣𐎲𐎢𐎪𐎡𐎹 ''Kabūjiya'') was the second King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 530 to 522 BC. He was the son and successor of Cyrus the Great () and his mother was Cassandane.

Before his accession, Cambyses ...

to sail against them, which Herodotus claims prevented the Persians from capturing Carthage. The Tyrians and Phoenicians escaped punishment because they had peacefully acceded to Persian rule years earlier and were relied upon for sustaining Persian naval power. Nonetheless, Tyre subsequently lost its privileged status to its principal rival, Sidon. The Phoenicians remained a core asset to the Achaemenid Empire, particularly for their prowess in shipbuilding, navigation, and maritime technology and skill—all of which the Persians lacked as a predominately land-based power. Archaeologist H. Jacob Katzenstein describes the Persian empire as a "blessing" to the Phoenicians, whose cities flourished due to their strategic and economic importance. He continues:The Phoenician towns became a strong factor in the development of Persian policy because of their fleets and their great maritime knowledge and experience, on which the Persian navy depended. The Persian king recognized this influential position, and the Persians regarded the Phoenicians more as allies than subjects. Arvad, Sidon, and Tyre were given large tracts of land and allowed to trade both on the Phoenician and Palestinian coast.Consequently, the Phoenicians appeared to have been consenting members of the Persian imperial project. For example, they willingly furnished the bulk of the Persian fleet during the

Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

of the late 5th century BC. Herodotus considers them "the best sailors" among Persian forces. Phoenicians under Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of ...

were equally commended for their ingenuity in building the Xerxes Canal

The Xerxes Canal ( el, Διώρυγα του Ξέρξη) was a navigable canal through the base of the Mount Athos peninsula in Chalkidiki, northern Greece, built by king Xerxes I of Persia in the 5th century BC. It is one of the few monuments lef ...

and the pontoon bridges that allowed his forces to cross into mainland Greece. Nevertheless, they were reportedly harshly punished by the Persian king following his ultimate defeat at the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles and the Persian Empire under King Xerxes in 480 BC. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was ...

, which he blamed on Phoenician cowardice and incompetence.

In the mid-4th century BC, King Tennes

Tennes (Tabnit II in the Phoenician language) was a King of Sidon under the Achaemenid Empire. His predecessor was Abdashtart I (in Greek, Straton I), the son of Baalshillem II, who ruled the Phoenician city-state of Sidon from (), having bee ...

of Sidon led a failed rebellion against Artaxerxes III

Ochus ( grc-gre, Ὦχος ), known by his dynastic name Artaxerxes III ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 359/58 to 338 BC. He was the son and successor of A ...

, enlisting the help of the Egyptians, who were subsequently drawn into a war with the Persians. A detailed account of the rebellion and subsequent conflict was described by Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

. The resulting destruction of the city led once more to the resurgence of its rival Tyre, which remained the principal Phoenician city for two decades until the arrival of Alexander the Great.

Hellenistic period (332–63 BC)

Located on the western periphery of the Persian Empire, Phoenicia was one of the first areas to be conquered byAlexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

during his military campaigns across western Asia. Alexander's main target in the Persian Levant was Tyre, now the region's largest and most important city. It capitulated after a roughly seven month siege, during which many of its citizens fled to Carthage.Fergus Millar, ''The Phoenician Cities: A Case-Study of Hellenisation,'' University of North Carolina Press (2006), pp. 32–50, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9780807876657_millar.8 Tyre's refusal to allow Alexander to visit its temple to Melqart

Melqart (also Melkarth or Melicarthus) was the tutelary god of the Phoenician city-state of Tyre and a major deity in the Phoenician and Punic pantheons. Often titled the "Lord of Tyre" (''Ba‘al Ṣūr''), he was also known as the Son of ...

, culminating in the killing of his envoys, led to a brutal reprisal: 2,000 of its leading citizens were crucified

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagin ...

and a puppet ruler was installed. The rest of Phoenicia easily came under his control, with Sidon, the second most powerful city, surrendering peacefully.

Unlike the Phoenicians—and for that matter their former Persian rulers—the Greeks were notably indifferent, if not hostile, to foreign cultures. Alexander's empire had a policy of Hellenization

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in the ...

, whereby Greek culture, religion, and sometimes language were spread or imposed across conquered peoples. This was typically implemented through the founding of new cities (most notably Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

in Egypt), the settlement of a Greek urban elite, and the alteration of native place names to Greek.

However, the Phoenicians were once again an outlier within an empire: there was evidently no "organised, deliberate effort of Hellenisation in Phoenicia", and with one or two minor exceptions, all Phoenician city states retained their native names, while Greek settlement and administration appears to have been limited. This is despite the fact that adjacent areas had been Hellenized, as had peripheral territories like the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

and Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, southwe ...

.

The Phoenicians also continued to maintain cultural and commercial links with their western counterparts. Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

recounts how the Seleucid king Demetrius I escaped from Rome by boarding a Carthaginian ship that was delivering goods to Tyre. An inscription in Malta, made between the second and third centuries BC, was dedicated to Herakles/Melqart in both Phoenician and Greek. To the extent the Phoenicians were subject to some degree of Hellenization, "there was much continuity with their Phoenician past—in language and perhaps in institutions; certainly in their cults; probably in some sort of literary tradition; perhaps in the preservation of archives; and certainly in a continuous historical consciousness." There is even evidence that a Hellenistic-Phoenician culture spread inland to Syria.Millar, p. 34: "Phoenician culture seems in some sense to have spread inland as well as overseas in the Hellenistic period, as Punic culture did also in North Africa after This fact brings Phoenician culture into connection with the familiar phenomenon of the fusion of Greek and non-Greek deities in Syria, or alternatively the survival of non-Greek cults in a Hellenised environment. There is nowhere where it appears more vividly before us than in Herodian’s description of the cult of Elagabal at Emesa; what is significant is that Herodian thought that ‘‘Elagabal’’ was a Phoenician name and that Julia Maesa was ‘"by origin a Phoinissa"" The adaptation to Macedonian rule was likely aided by the Phoenician's historical ties with the Greeks, with whom they shared some mythological stories and figures; the two peoples were even sometimes considered "relatives".Millar, p. 50: Secondly, and more important, when the Phoenicians began to explore the storehouse of Greek culture, they could find, among other things, themselves, already credited with creative roles—not all of which, as it happens, were purely legendary. If some aspects were just legend, like the story of Kadmos, what is clear is that the Phoenicians adopted it (perhaps, like the legend of Aeneas in Italy, very early) and made it their own. In doing so they acquired both an extra past and a reinforcement of their historical identity; and they also simultaneously gained acceptance as being in some sense Greeks

Alexander's empire collapsed soon after his death in 323 BC, dissolving into several rival kingdoms ruled by his generals, relatives, or friends. The Phoenicians came under the control of the largest and most powerful of these successors, the Seleucids

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

. The Phoenician homeland was repeatedly contested by the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt during the forty year Syrian Wars

The Syrian Wars were a series of six wars between the Seleucid Empire and the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, successor states to Alexander the Great's empire, during the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC over the region then called Coele-Syria, one of th ...

, coming under Ptolemaic rule in the third century BC. The Seleucids reclaimed the area the following century, holding it until the mid-first century BC. Under their rule, the Phoenicians were evidently allowed a considerable degree of autonomy.

During the Seleucid Dynastic Wars

The Seleucid Dynastic Wars were a series of wars of succession that were fought between competing branches of the Seleucid royal household for control of the Seleucid Empire. Beginning as a by-product of several succession crises that arose from ...

(157–63 BC), the Phoenician cities were fought over by the warring factions of the Seleucid royal family. The Seleucid Empire, which once stretched from the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

to Pakistan, was reduced to a rump state

A rump state is the remnant of a once much larger state, left with a reduced territory in the wake of secession, annexation, occupation, decolonization, or a successful coup d'état or revolution on part of its former territory. In the last case, ...

comprising portions of the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

and southeast Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. Little is known of life in Phoenicia during this time, but the Seleucids were severely weakened, and their realm left as a buffer between various rival states, before being annexed to the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

by Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

in 63 BC. After centuries of decline, the last vestiges of Phoenician power in the Eastern Mediterranean were absorbed into the Roman province of Coele-Syria

Coele-Syria (, also spelt Coele Syria, Coelesyria, Celesyria) alternatively Coelo-Syria or Coelosyria (; grc-gre, Κοίλη Συρία, ''Koílē Syría'', 'Hollow Syria'; lat, Cœlē Syria or ), was a region of Syria (region), Syria in cl ...

.

Notes

References

{{reflist Ancient Lebanon History of the Mediterranean