History of palaeontology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of paleontology traces the history of the effort to understand the history of life on Earth by studying the

The history of paleontology traces the history of the effort to understand the history of life on Earth by studying the

author's homepage

/ref>

During the

During the  Hooke was prepared to accept the possibility that some such fossils represented species that had become extinct, possibly in past geological catastrophes.

In 1667

Hooke was prepared to accept the possibility that some such fossils represented species that had become extinct, possibly in past geological catastrophes.

In 1667

The history of paleontology traces the history of the effort to understand the history of life on Earth by studying the

The history of paleontology traces the history of the effort to understand the history of life on Earth by studying the fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

record left behind by living organisms. Since it is concerned with understanding living organisms of the past, paleontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

can be considered to be a field of biology, but its historical development has been closely tied to geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

and the effort to understand the history of Earth

The history of Earth concerns the development of planet Earth from its formation to the present day. Nearly all branches of natural science have contributed to understanding of the main events of Earth's past, characterized by constant geologi ...

itself.

In ancient times, Xenophanes

Xenophanes of Colophon (; grc, Ξενοφάνης ὁ Κολοφώνιος ; c. 570 – c. 478 BC) was a Greek philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φ ...

(570–480 BC), Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

(484–425 BC), Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexandria ...

(276–194 BC), and Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

(64 BC–24 AD) wrote about fossils of marine organisms, indicating that land was once under water. The ancient Chinese considered them to be dragon

A dragon is a reptilian legendary creature that appears in the folklore of many cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted as ...

bones and documented them as such. During the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, fossils were discussed by Persian naturalist Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

(known as ''Avicenna'' in Europe) in ''The Book of Healing

''The Book of Healing'' (; ; also known as ) is a scientific and philosophical encyclopedia written by Abu Ali ibn Sīna (aka Avicenna) from medieval Persia, near Bukhara in Maverounnahr. He most likely began to compose the book in 1014, comp ...

'' (1027), which proposed a theory of petrifying fluids that Albert of Saxony

en, Frederick Augustus Albert Anthony Ferdinand Joseph Charles Maria Baptist Nepomuk William Xavier George Fidelis

, image = Albert of Saxony by Nicola Perscheid c1900.jpg

, image_size =

, caption = Photograph by Nicola Persch ...

would elaborate on in the 14th century

As a means of recording the passage of time, the 14th century was a century lasting from 1 January 1301 ( MCCCI), to 31 December 1400 ( MCD). It is estimated that the century witnessed the death of more than 45 million lives from political and n ...

. The Chinese naturalist Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo (; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁),Yao (2003), 544. was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Shen wa ...

(1031–1095) would propose a theory of climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

based on evidence from petrified bamboo.

In early modern Europe

Early modern Europe, also referred to as the post-medieval period, is the period of European history between the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, roughly the late 15th century to the late 18th century. Histori ...

, the systematic study of fossils emerged as an integral part of the changes in natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior throu ...

that occurred during the Age of Reason

The Age of reason, or the Enlightenment, was an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th to 19th centuries.

Age of reason or Age of Reason may also refer to:

* Age of reason (canon law), ...

. The nature of fossils and their relationship to life in the past became better understood during the 17th and 18th centuries, and at the end of the 18th century

The 18th century lasted from January 1, 1701 ( MDCCI) to December 31, 1800 ( MDCCC). During the 18th century, elements of Enlightenment thinking culminated in the American, French, and Haitian Revolutions. During the century, slave trad ...

, the work of Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier ...

had ended a long running debate about the reality of extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

, leading to the emergence of paleontology – in association with comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

– as a scientific discipline. The expanding knowledge of the fossil record also played an increasing role in the development of geology, and stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock (geology), rock layers (Stratum, strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary rock, sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigrap ...

in particular.

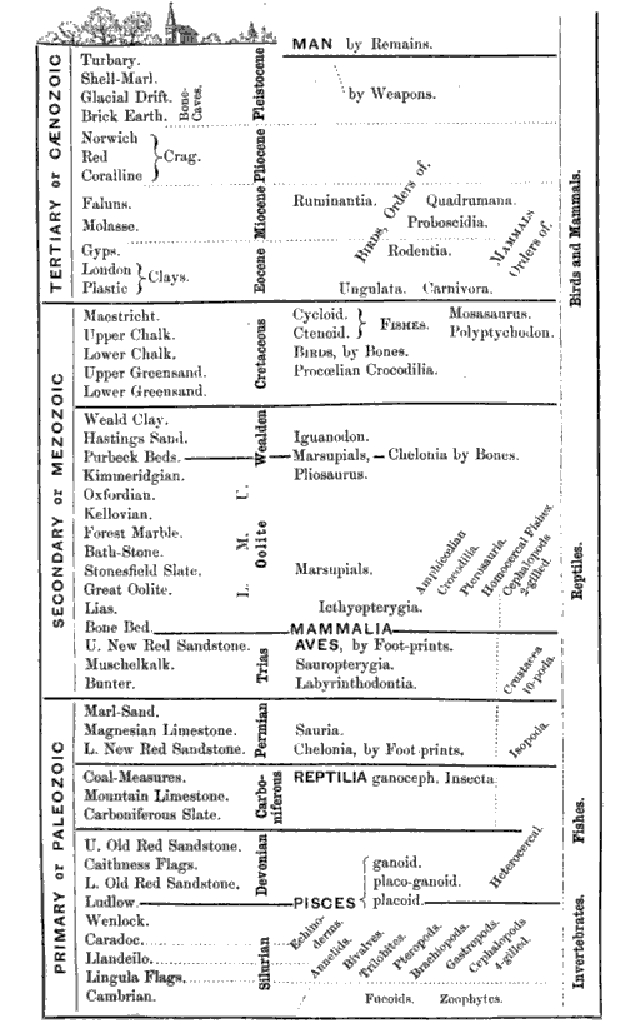

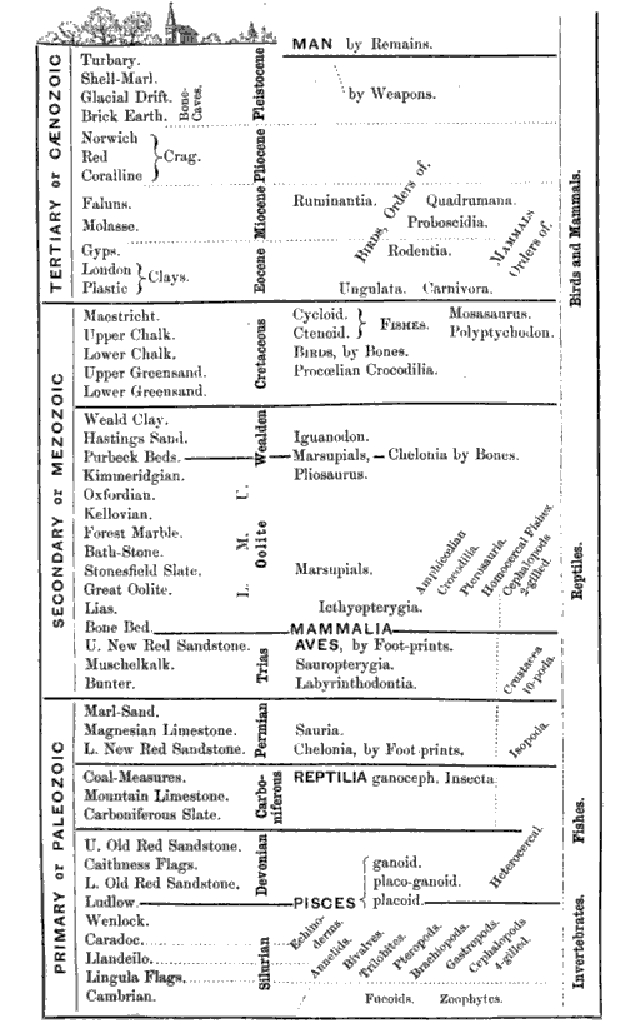

In 1822, the word "paleontology" was used by the editor of a French scientific journal to refer to the study of ancient living organisms through fossils, and the first half of the 19th century saw geological and paleontological activity become increasingly well organized with the growth of geologic societies and museums and an increasing number of professional geologists and fossil specialists. This contributed to a rapid increase in knowledge about the history of life on Earth, and progress towards definition of the geologic time scale

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochrono ...

largely based on fossil evidence. As knowledge of life's history continued to improve, it became increasingly obvious that there had been some kind of successive order to the development of life. This would encourage early evolutionary theories on the transmutation of species

Transmutation of species and transformism are unproven 18th and 19th-century evolutionary ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a term used ...

. After Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

published ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'' in 1859, much of the focus of paleontology shifted to understanding evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary paths, including human evolution

Human evolution is the evolutionary process within the history of primates that led to the emergence of ''Homo sapiens'' as a distinct species of the hominid family, which includes the great apes. This process involved the gradual development of ...

, and evolutionary theory.

The last half of the 19th century saw a tremendous expansion in paleontological activity, especially in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

. The trend continued in the 20th century with additional regions of the Earth being opened to systematic fossil collection, as demonstrated by a series of important discoveries in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

near the end of the 20th century. Many transitional fossils

A transitional fossil is any fossilized remains of a life form that exhibits traits common to both an ancestral group and its derived descendant group. This is especially important where the descendant group is sharply differentiated by gross a ...

have been discovered, and there is now considered to be abundant evidence of how all classes of vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

s are related, much of it in the form of transitional fossils. The last few decades of the 20th century

The 20th (twentieth) century began on

January 1, 1901 ( MCMI), and ended on December 31, 2000 ( MM). The 20th century was dominated by significant events that defined the modern era: Spanish flu pandemic, World War I and World War II, nuclear ...

saw a renewed interest in mass extinction

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp change in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. It ...

s and their role in the evolution of life on Earth. There was also a renewed interest in the Cambrian explosion

The Cambrian explosion, Cambrian radiation, Cambrian diversification, or the Biological Big Bang refers to an interval of time approximately in the Cambrian Period when practically all major animal phyla started appearing in the fossil recor ...

that saw the development of the body plans of most animal phyla. The discovery of fossils of the Ediacaran biota

The Ediacaran (; formerly Vendian) biota is a Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic period classification that consists of all life forms that were present on Earth during the Ediacaran Period (). These were composed of enigmatic tubular and frond-sh ...

and developments in paleobiology

Paleobiology (or palaeobiology) is an interdisciplinary field that combines the methods and findings found in both the earth sciences and the life sciences. Paleobiology is not to be confused with geobiology, which focuses more on the interactio ...

extended knowledge about the history of life back far before the Cambrian.

Prior to the 17th century

As early as the 6th century BC, theGreek philosopher

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

Xenophanes of Colophon

Xenophanes of Colophon (; grc, Ξενοφάνης ὁ Κολοφώνιος ; c. 570 – c. 478 BC) was a Greek philosopher, theologian, poet, and critic of Homer from Ionia who travelled throughout the Greek-speaking world in early Classical An ...

(570–480 BC) recognized that some fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

shells were remains of shellfish, which he used to argue that what was at the time dry land was once under the sea.Desmond pp. 692–697. Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

(1452–1519), in an unpublished notebook, also concluded that some fossil sea shells were the remains of shellfish. However, in both cases, the fossils were complete remains of shellfish species that closely resembled living species, and were therefore easy to classify.

In 1027, the Persian naturalist, Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

(known as ''Avicenna'' in Europe), proposed an explanation of how the stoniness of fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s was caused in ''The Book of Healing

''The Book of Healing'' (; ; also known as ) is a scientific and philosophical encyclopedia written by Abu Ali ibn Sīna (aka Avicenna) from medieval Persia, near Bukhara in Maverounnahr. He most likely began to compose the book in 1014, comp ...

''. He modified an idea of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

's, which explained it in terms of vapor

In physics, a vapor (American English) or vapour (British English and Canadian English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences) is a substance in the gas phase at a temperature lower than its critic ...

ous exhalation

Exhalation (or expiration) is the flow of the breath out of an organism. In animals, it is the movement of air from the lungs out of the airways, to the external environment during breathing.

This happens due to elastic properties of the lungs, ...

s. Ibn Sina modified this into the theory of petrifying fluids (''succus lapidificatus''), which was elaborated on by Albert of Saxony

en, Frederick Augustus Albert Anthony Ferdinand Joseph Charles Maria Baptist Nepomuk William Xavier George Fidelis

, image = Albert of Saxony by Nicola Perscheid c1900.jpg

, image_size =

, caption = Photograph by Nicola Persch ...

in the 14th century

As a means of recording the passage of time, the 14th century was a century lasting from 1 January 1301 ( MCCCI), to 31 December 1400 ( MCD). It is estimated that the century witnessed the death of more than 45 million lives from political and n ...

and was accepted in some form by most naturalists by the 16th century.Rudwick ''The Meaning of Fossils'' p. 24

Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo (; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁),Yao (2003), 544. was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Shen wa ...

() (1031–1095) of the Song Dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

used marine

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military

* ...

fossils found in the Taihang Mountains

The Taihang Mountains () are a Chinese mountain range running down the eastern edge of the Loess Plateau in Shanxi, Henan and Hebei provinces. The range extends over from north to south and has an average elevation of . The principal peak is ...

to infer the existence of geological

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Eart ...

processes such as geomorphology

Geomorphology (from Ancient Greek: , ', "earth"; , ', "form"; and , ', "study") is the scientific study of the origin and evolution of topographic and bathymetric features created by physical, chemical or biological processes operating at or n ...

and the shifting of seashores over time. In 1088 AD, he discovered preserved petrified

In geology, petrifaction or petrification () is the process by which organic material becomes a fossil through the replacement of the original material and the filling of the original pore spaces with minerals. Petrified wood typifies this proce ...

bamboo

Bamboos are a diverse group of evergreen perennial flowering plants making up the subfamily Bambusoideae of the grass family Poaceae. Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family. The origin of the word "bamboo" is uncertain, bu ...

s found underground in Yan'an

Yan'an (; ), alternatively spelled as Yenan is a prefecture-level city in the Shaanbei region of Shaanxi province, China, bordering Shanxi to the east and Gansu to the west. It administers several counties, including Zhidan (formerly Bao'an ...

, Shanbei

Shaanbei () or Northern Shaanxi is the portion of China's Shaanxi province north of the Huanglong Mountain and the Meridian Ridge (the so-called "Guanzhong north mountains"), and is both a geographic as well as a cultural area.

It makes up the so ...

region, Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see #Name, § Name) is a landlocked Provinces of China, province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichu ...

province. Using his observation, he argued for a theory of gradual climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

, since Shaanxi was part of a dry climate zone that did not support a habitat for the growth of bamboos.Needham, Volume 3, p. 614.

As a result of a new emphasis on observing, classifying, and cataloging nature, 16th-century natural philosophers in Europe began to establish extensive collections

Collection or Collections may refer to:

* Cash collection, the function of an accounts receivable department

* Collection (church), money donated by the congregation during a church service

* Collection agency, agency to collect cash

* Collection ...

of fossil objects (as well as collections of plant and animal specimens), which were often stored in specially built cabinets to help organize them. Conrad Gesner

Conrad Gessner (; la, Conradus Gesnerus 26 March 1516 – 13 December 1565) was a Swiss physician, naturalist, bibliographer, and philologist. Born into a poor family in Zürich, Switzerland, his father and teachers quickly realised his tale ...

published a 1565 work on fossils that contained one of the first detailed descriptions of such a cabinet and collection. The collection belonged to a member of the extensive network of correspondents that Gesner drew on for his works. Such informal correspondence networks among natural philosophers and collectors became increasingly important during the course of the 16th century and were direct forerunners of the scientific societies that would begin to form in the 17th century. These cabinet collections and correspondence networks played an important role in the development of natural philosophy.

However, most 16th-century Europeans did not recognize that fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s were the remains of living organisms. The etymology of the word ''fossil'' comes from the Latin for things having been dug up. As this indicates, the term was applied to a wide variety of stone and stone-like objects without regard to whether they might have an organic origin. 16th-century writers such as Gesner and Georg Agricola

Georgius Agricola (; born Georg Pawer or Georg Bauer; 24 March 1494 – 21 November 1555) was a German Humanist scholar, mineralogist and metallurgist. Born in the small town of Glauchau, in the Electorate of Saxony of the Holy Roman Empire ...

were more interested in classifying such objects by their physical and mystical properties than they were in determining the objects' origins. In addition, the natural philosophy of the period encouraged alternative explanations for the origin of fossils. Both the Aristotelian and Neoplatonic

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some ide ...

schools of philosophy provided support for the idea that stony objects might grow within the earth to resemble living things. Neoplatonic philosophy maintained that there could be affinities between living and non-living objects that could cause one to resemble the other. The Aristotelian school maintained that the seeds of living organisms could enter the ground and generate objects resembling those organisms.

Leonardo da Vinci and the development of paleontology

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

established a line of continuity between the two main branches of paleontology: body fossil palaeontology and ichnology. In fact, Leonardo dealt with both major classes of fossils: (1) body fossils, e.g. fossilized shells; (2) ichnofossils (also known as trace fossils), i.e. the fossilized products of life-substrate interactions (e.g. burrows and borings). In folios 8 to 10 of the Leicester code, Leonardo examined the subject of body fossils, tackling one of the vexing issues of his contemporaries: why do we find petrified seashells on mountains? Leonardo answered this question by correctly interpreting the biogenic nature of fossil mollusks and their sedimentary matrix. The interpretation of Leonardo da Vinci appears extraordinarily innovative as he surpassed three centuries of scientific debate on the nature of body fossils. Da Vinci took into consideration invertebrate ichnofossils to prove his ideas on the nature of fossil objects. To da Vinci, ichnofossils played a central role in demonstrating: (1) the organic nature of petrified shells and (2) the sedimentary origin of the rock layers bearing fossil objects. Da Vinci described what are bioerosion ichnofossils:Baucon, A. 2010. Da Vinci’s ''Paleodictyon'': the fractal beauty of traces. Acta Geologica Polonica, 60(1). Available from thauthor's homepage

/ref>

‘‘The hills around Parma and Piacenza show abundant mollusks and bored corals still attached to the rocks. When I was working on the great horse in Milan, certain peasants brought me a huge bagful of them’’

— Leicester Code, folio 9rSuch fossil borings allowed Leonardo to confute the Inorganic theory, i.e. the idea that so-called petrified shells (mollusk body fossils) are inorganic curiosities. With the words of Leonardo da Vinci:

‘‘ he Inorganic theory is not truebecause there remains the trace of the nimal’smovements on the shell which tconsumed in the same manner of a woodworm in wood …’’

— Leicester Code, folio 9vDa Vinci discussed not only fossil borings, but also burrows. Leonardo used fossil burrows as paleoenvironmental tools to demonstrate the marine nature of sedimentary strata:

‘‘Between one layer and the other there remain traces of the worms that crept between them when they had not yet dried. All the sea mud still contains shells, and the shells are petrified together with the mud’’

— Leicester Code, folio 10vOther Renaissance naturalists studied invertebrate ichnofossils during the Renaissance, but none of them reached such accurate conclusions. Leonardo's considerations of invertebrate ichnofossils are extraordinarily modern not only when compared to those of his contemporaries, but also to interpretations in later times. In fact, during the 1800s invertebrate ichnofossils were explained as fucoids, or seaweed, and their true nature was widely understood only by the early 1900s. For these reasons, Leonardo da Vinci is deservedly considered the founding father of both the major branches of palaeontology, i.e. the study of body fossils and ichnology.

17th century

During the

During the Age of Reason

The Age of reason, or the Enlightenment, was an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th to 19th centuries.

Age of reason or Age of Reason may also refer to:

* Age of reason (canon law), ...

, fundamental changes in natural philosophy were reflected in the analysis of fossils. In 1665 Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans ...

attributed giant bones to extinct races of giant humans in his ''Mundus subterraneus''. In the same year Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

published ''Micrographia

''Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses. With Observations and Inquiries Thereupon.'' is a historically significant book by Robert Hooke about his observations through various lenses. It w ...

'', an illustrated collection of his observations with a microscope. One of these observations was entitled "Of Petrify'd wood, and other Petrify'd bodies", which included a comparison between petrified and ordinary wood. He concluded that petrified wood was ordinary wood that had been soaked with "water impregnated with stony and earthy particles". He then suggested that several kinds of fossil sea shells were formed from ordinary shells by a similar process. He argued against the prevalent view that such objects were "Stones form'd by some extraordinary Plastick virtue latent in the Earth itself". Hooke believed that fossils provided evidence about the history of life on Earth writing in 1668:

...if the finding of Coines, Medals, Urnes, and other Monuments of famous persons, or Towns, or Utensils, be admitted for unquestionable Proofs, that such Persons or things have, in former times had a being, certainly those Petrifactions may be allowed to be of equal Validity and Evidence, that there have formerly been such Vegetables or Animals... and are true universal Characters legible to all rational Men.Bowler ''The Earth Encompassed'' (1992) pp. 118–119

Hooke was prepared to accept the possibility that some such fossils represented species that had become extinct, possibly in past geological catastrophes.

In 1667

Hooke was prepared to accept the possibility that some such fossils represented species that had become extinct, possibly in past geological catastrophes.

In 1667 Nicholas Steno

Niels Steensen ( da, Niels Steensen; Latinized to ''Nicolaus Steno'' or ''Nicolaus Stenonius''; 1 January 1638 – 25 November 1686tongue stones" or ''glossopetrae''. He concluded that the fossils must have been shark teeth. Steno then took an interest in the question of fossils, and to address some of the objections to their organic origin he began studying rock strata. The result of this work was published in 1669 as ''Forerunner to a Dissertation on a solid naturally enclosed in a solid''. In this book, Steno drew a clear distinction between objects such as rock crystals that really were formed within rocks and those such as fossil shells and shark teeth that were formed outside of those rocks. Steno realized that certain kinds of rock had been formed by the successive deposition of horizontal layers of sediment and that fossils were the remains of living organisms that had become buried in that sediment. Steno who, like almost all 17th-century natural philosophers, believed that the earth was only a few thousand years old, resorted to the

In his 1778 work ''Epochs of Nature''

In his 1778 work ''Epochs of Nature''  In a pioneering application of

In a pioneering application of

The

The

In 1808, Cuvier identified a fossil found in

In 1808, Cuvier identified a fossil found in  This evidence that giant reptiles had lived on Earth in the past caused great excitement in scientific circles, and even among some segments of the general public. Buckland did describe the jaw of a small primitive mammal, ''Phascolotherium'', that was found in the same strata as ''Megalosaurus''. This discovery, known as the Stonesfield mammal, was a much discussed anomaly. Cuvier at first thought it was a

This evidence that giant reptiles had lived on Earth in the past caused great excitement in scientific circles, and even among some segments of the general public. Buckland did describe the jaw of a small primitive mammal, ''Phascolotherium'', that was found in the same strata as ''Megalosaurus''. This discovery, known as the Stonesfield mammal, was a much discussed anomaly. Cuvier at first thought it was a

This rapid progress in geology and paleontology during the 1830s and 1840s was aided by a growing international network of geologists and fossil specialists whose work was organized and reviewed by an increasing number of geological societies. Many of these geologists and paleontologists were now paid professionals working for universities, museums and government geological surveys. The relatively high level of public support for the earth sciences was due to their cultural impact, and their proven economic value in helping to exploit mineral resources such as coal.

Another important factor was the development in the late 18th and early 19th centuries of museums with large natural history collections. These museums received specimens from collectors around the world and served as centers for the study of comparative anatomy and

This rapid progress in geology and paleontology during the 1830s and 1840s was aided by a growing international network of geologists and fossil specialists whose work was organized and reviewed by an increasing number of geological societies. Many of these geologists and paleontologists were now paid professionals working for universities, museums and government geological surveys. The relatively high level of public support for the earth sciences was due to their cultural impact, and their proven economic value in helping to exploit mineral resources such as coal.

Another important factor was the development in the late 18th and early 19th centuries of museums with large natural history collections. These museums received specimens from collectors around the world and served as centers for the study of comparative anatomy and

There was also great interest in human evolution. Neanderthal fossils were discovered in 1856, but at the time it was not clear that they represented a different species from modern humans. Eugene Dubois created a sensation with his discovery of

There was also great interest in human evolution. Neanderthal fossils were discovered in 1856, but at the time it was not clear that they represented a different species from modern humans. Eugene Dubois created a sensation with his discovery of

Throughout the 20th century new fossil finds continued to contribute to understanding the paths taken by evolution. Examples include major taxonomic transitions such as finds in Greenland, starting in the 1930s (with more major finds in the 1980s), of fossils illustrating the evolution of tetrapods from fish, and fossils in China during the 1990s that shed light on the Origin of birds, dinosaur-bird relationship. Other events that have attracted considerable attention have included the discovery of a series of fossils in Pakistan that have shed light on whale evolution, and most famously of all a series of finds throughout the 20th century in Africa (starting with Taung child in 1924) and elsewhere have helped illuminate the course of

Throughout the 20th century new fossil finds continued to contribute to understanding the paths taken by evolution. Examples include major taxonomic transitions such as finds in Greenland, starting in the 1930s (with more major finds in the 1980s), of fossils illustrating the evolution of tetrapods from fish, and fossils in China during the 1990s that shed light on the Origin of birds, dinosaur-bird relationship. Other events that have attracted considerable attention have included the discovery of a series of fossils in Pakistan that have shed light on whale evolution, and most famously of all a series of finds throughout the 20th century in Africa (starting with Taung child in 1924) and elsewhere have helped illuminate the course of

"Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism"

In T.J.M. Schopf, ed., ''Models in Paleobiology''. San Francisco: Freeman Cooper. pp. 82–115. Reprinted in N. Eldredge ''Time frames''. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1985. Available here .

One area of paleontology that has seen a lot of activity during the 1980s, 1990s, and beyond is the study of the

One area of paleontology that has seen a lot of activity during the 1980s, 1990s, and beyond is the study of the

Prior to 1950 there was no widely accepted fossil evidence of life before the Cambrian period. When

Prior to 1950 there was no widely accepted fossil evidence of life before the Cambrian period. When

''Micrographia''

The Royal Society * Palmer, Douglas (2005) ''Earth Time: Exploring the Deep Past from Victorian England to the Grand Canyon''. Wiley, Chichester. * * * * * * *

History of paleontology

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Paleontology History of paleontology, Paleontologists, * History of science by discipline, Paleontology

Biblical flood

The Genesis flood narrative (chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis) is the Hebrew version of the universal flood myth. It tells of God's decision to return the universe to its pre- creation state of watery chaos and remake it through the microc ...

as a possible explanation for fossils of marine organisms that were far from the sea.

Despite the considerable influence of ''Forerunner'', naturalists such as Martin Lister

Martin Lister FRS (12 April 1639 – 2 February 1712) was an English naturalist and physician. His daughters Anne and Susanna were two of his illustrators and engravers.

J. D. Woodley, ‘Lister , Susanna (bap. 1670, d. 1738)’, Oxford Dict ...

(1638–1712) and John Ray

John Ray FRS (29 November 1627 – 17 January 1705) was a Christian English naturalist widely regarded as one of the earliest of the English parson-naturalists. Until 1670, he wrote his name as John Wray. From then on, he used 'Ray', after ...

(1627–1705) continued to question the organic origin of some fossils. They were particularly concerned about objects such as fossil Ammonites

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) ...

, which Hooke claimed were organic in origin, that did not resemble any known living species. This raised the possibility of extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

, which they found difficult to accept for philosophical and theological reasons. In 1695 Ray wrote to the Welsh naturalist Edward Lluyd

Edward Lhuyd FRS (; occasionally written Llwyd in line with modern Welsh orthography, 1660 – 30 June 1709) was a Welsh naturalist, botanist, linguist, geographer and antiquary. He is also named in a Latinate form as Eduardus Luidius.

Life

...

complaining of such views: "... there follows such a train of consequences, as seem to shock the Scripture-History of the novity of the World; at least they overthrow the opinion received, & not without good reason, among Divines and Philosophers, that since the first Creation there have been no species of Animals or Vegetables lost, no new ones produced."

18th century

In his 1778 work ''Epochs of Nature''

In his 1778 work ''Epochs of Nature'' Georges Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (; 7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopédiste.

His works influenced the next two generations of naturalists, including two prominent Fr ...

referred to fossils, in particular the discovery of fossils of tropical species such as elephants

Elephants are the largest existing land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant. They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantidae and ...

and rhinoceros

A rhinoceros (; ; ), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates in the family Rhinocerotidae. (It can also refer to a member of any of the extinct species o ...

in northern Europe, as evidence for the theory that the earth had started out much warmer than it currently was and had been gradually cooling.

In 1796 Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier ...

presented a paper on living and fossil elephants comparing skeletal remains of Indian and African elephant

Elephants are the largest existing land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant. They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantidae an ...

s to fossils of mammoths

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks and, ...

and of an animal he would later name mastodon

A mastodon ( 'breast' + 'tooth') is any proboscidean belonging to the extinct genus ''Mammut'' (family Mammutidae). Mastodons inhabited North and Central America during the late Miocene or late Pliocene up to their extinction at the end of th ...

utilizing comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

. He established for the first time that Indian and African elephants were different species, and that mammoths differed from both and must be extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

. He further concluded that the mastodon was another extinct species that also differed from Indian or African elephants, more so than mammoths. Cuvier made another powerful demonstration of the power of comparative anatomy in paleontology when he presented a second paper in 1796 on a large fossil skeleton from Paraguay, which he named ''Megatherium

''Megatherium'' ( ; from Greek () 'great' + () 'beast') is an extinct genus of ground sloths endemic to South America that lived from the Early Pliocene through the end of the Pleistocene. It is best known for the elephant-sized type species ' ...

'' and identified as a giant sloth

Ground sloths are a diverse group of extinct sloths in the mammalian superorder Xenarthra. The term is used to refer to all extinct sloths because of the large size of the earliest forms discovered, compared to existing tree sloths. The Carib ...

by comparing its skull to those of two living species of tree sloth. Cuvier's ground-breaking work in paleontology and comparative anatomy led to the widespread acceptance of extinction. It also led Cuvier to advocate the geological theory of catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism theorises that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow increment ...

to explain the succession of organisms revealed by the fossil record. He also pointed out that since mammoths and woolly rhinoceros

The woolly rhinoceros (''Coelodonta antiquitatis'') is an extinct species of rhinoceros that was common throughout Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene epoch and survived until the end of the last glacial period. The woolly rhinoceros was a me ...

were not the same species as the elephants and rhinoceros currently living in the tropics, their fossils could not be used as evidence for a cooling earth.

In a pioneering application of

In a pioneering application of stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock (geology), rock layers (Stratum, strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary rock, sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigrap ...

, William Smith, a surveyor and mining engineer, made extensive use of fossils to help correlate rock strata in different locations. He created the first geological map

A geologic map or geological map is a special-purpose map made to show various geological features. Rock units or geologic strata are shown by color or symbols. Bedding planes and structural features such as faults, folds, are shown with st ...

of England during the late 1790s and early 19th century. He established the principle of faunal succession

The principle of faunal succession, also known as the law of faunal succession, is based on the observation that sedimentary rock strata contain fossilized flora and fauna, and that these fossils succeed each other vertically in a specific, rel ...

, the idea that each strata of sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles ...

would contain particular types of fossils, and that these would succeed one another in a predictable way even in widely separated geologic formations. At the same time, Cuvier and Alexandre Brongniart

Alexandre Brongniart (5 February 17707 October 1847) was a French chemist, mineralogist, geologist, paleontologist, and zoologist, who collaborated with Georges Cuvier on a study of the geology of the region around Paris. Observing fossil content ...

, an instructor at the Paris school of mine engineering, used similar methods in an influential study of the geology of the region around Paris.

Early to mid-19th century

The study of fossils and the origin of the word ''paleontology''

The

The Smithsonian Libraries

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is an institutional archives and library system comprising 21 branch libraries serving the various Smithsonian Institution museums and research centers. The Libraries and Archives serve Smithsonian Institution ...

consider that the first edition of a work which laid the foundation to vertebrate paleontology was Georges Cuvier's ''Recherches sur les ossements fossiles de quadrupèdes'' (''Researches on quadruped fossil bones''), published in France in 1812. Referring to the second edition of this work (1821), Cuvier's disciple and editor of the scientific publication

: ''For a broader class of literature, see Academic publishing.''

Scientific literature comprises scholarly publications that report original empirical and theoretical work in the natural and social sciences. Within an academic field, scienti ...

''Journal de physique'' Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville

Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville (; 12 September 1777 – 1 May 1850) was a French zoologist and anatomist.

Life

Blainville was born at Arques, near Dieppe. As a young man he went to Paris to study art, but ultimately devoted himself to natur ...

published in January 1822, in the ''Journal de physique'', an article titled "Analyse des principaux travaux dans les sciences physiques, publiés dans l'année 1821" ("Analysis of the main works in the physical sciences, published in the year 1821"). In this article Blainville unveiled for the first time the printed word ''palæontologie'' which later gave the English word "paleontology". Blainville had already coined the term ''paléozoologie'' in 1817 to refer to the work Cuvier and others were doing to reconstruct extinct animals from fossil bones. However, Blainville began looking for a term that could refer to the study of both fossil animal and plant remains. After trying some unsuccessful alternatives, he hit on "palaeontologie" in 1822. Blainville's term for the study of the fossilized organisms quickly became popular and was anglicized into "paleontology".

In 1828 Alexandre Brongniart

Alexandre Brongniart (5 February 17707 October 1847) was a French chemist, mineralogist, geologist, paleontologist, and zoologist, who collaborated with Georges Cuvier on a study of the geology of the region around Paris. Observing fossil content ...

's son, the botanist Adolphe Brongniart

''Adolphe'' is a classic French novel by Benjamin Constant, first published in 1816. It tells the story of an alienated young man, Adolphe, who falls in love with an older woman, Ellénore, the Polish mistress of the Comte de P***. Their illicit ...

, published the introduction to a longer work on the history of fossil plants. Adolphe Brongniart concluded that the history of plants could roughly be divided into four parts. The first period was characterized by cryptogam

A cryptogam (scientific name Cryptogamae) is a plant (in the wide sense of the word) or a plant-like organism that reproduces by spores, without flowers or seeds. The name ''Cryptogamae'' () means "hidden reproduction", referring to the fact ...

s. The second period was characterized by the appearance of the conifer

Conifers are a group of conifer cone, cone-bearing Spermatophyte, seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the phylum, division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single ...

s. The third period brought emergence of the cycad

Cycads are seed plants that typically have a stout and woody (ligneous) trunk (botany), trunk with a crown (botany), crown of large, hard, stiff, evergreen and (usually) pinnate leaves. The species are dioecious, that is, individual plants o ...

s, and the fourth by the development of the flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants th ...

s (such as the dicotyledon

The dicotyledons, also known as dicots (or, more rarely, dicotyls), are one of the two groups into which all the flowering plants (angiosperms) were formerly divided. The name refers to one of the typical characteristics of the group: namely, t ...

s). The transitions between each of these periods was marked by sharp discontinuities in the fossil record, with more gradual changes within the periods. Brongniart's work is the foundation of paleobotany

Paleobotany, which is also spelled as palaeobotany, is the branch of botany dealing with the recovery and identification of plant remains from geological contexts, and their use for the biological reconstruction of past environments (paleogeogr ...

and reinforced the theory that life on earth had a long and complex history, and different groups of plants and animals made their appearances in successive order. It also supported the idea that the Earth's climate had changed over time as Brongniart concluded that plant fossils showed that during the Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, million years ago. The name ''Carbonifero ...

the climate of Northern Europe must have been tropical. The term "paleobotany" was coined in 1884 and "palynology" in 1944.

The age of reptiles

In 1808, Cuvier identified a fossil found in

In 1808, Cuvier identified a fossil found in Maastricht

Maastricht ( , , ; li, Mestreech ; french: Maestricht ; es, Mastrique ) is a city and a municipality in the southeastern Netherlands. It is the capital and largest city of the province of Limburg. Maastricht is located on both sides of the ...

as a giant marine reptile that would later be named ''Mosasaurus

''Mosasaurus'' (; "lizard of the Meuse River") is the type genus (defining example) of the mosasaurs, an extinct group of aquatic squamate reptiles. It lived from about 82 to 66 million years ago during the Campanian and Maastrichtian stages o ...

''. He also identified, from a drawing, another fossil found in Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

as a flying reptile and named it ''Pterodactylus

''Pterodactylus'' (from Greek () meaning 'winged finger') is an extinct genus of pterosaurs. It is thought to contain only a single species, ''Pterodactylus antiquus'', which was the first pterosaur to be named and identified as a flying rept ...

''. He speculated, based on the strata in which these fossils were found, that large reptiles had lived prior to what he was calling "the age of mammals". Cuvier's speculation would be supported by a series of finds that would be made in Great Britain over the course of the next two decades. Mary Anning

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was an English fossil collector, dealer, and palaeontologist who became known around the world for the discoveries she made in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Channel ...

, a professional fossil collector since age eleven, collected the fossils of a number of marine reptiles and prehistoric fish from the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

marine strata at Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset–Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and beaches on the Herita ...

. These included the first ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, altho ...

skeleton to be recognized as such, which was collected in 1811, and the first two plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria (; Greek: πλησίος, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared ...

skeletons ever found in 1821 and 1823. Mary Anning was only 12 when she and her brother discovered the Ichthyosaurus skeleton. Many of her discoveries would be described scientifically by the geologists William Conybeare, Henry De la Beche

Sir Henry Thomas De la Beche KCB, FRS (10 February 179613 April 1855) was an English geologist and palaeontologist, the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, who helped pioneer early geological survey methods. He was the f ...

, and William Buckland

William Buckland Doctor of Divinity, DD, Royal Society, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full ...

. It was Anning who observed that stony objects known as "bezoar

A bezoar is a mass often found trapped in the gastrointestinal system, though it can occur in other locations. A pseudobezoar is an indigestible object introduced intentionally into the digestive system.

There are several varieties of bezoar, s ...

stones" were often found in the abdominal region of ichthyosaur skeletons, and she noted that if such stones were broken open they often contained fossilized fish bones and scales as well as sometimes bones from small ichthyosaurs. This led her to suggest to Buckland that they were fossilized feces, which he named coprolite

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name is de ...

s, and which he used to better understand ancient food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), det ...

s. Mary Anning made many fossil discoveries that revolutionized science. However, despite her phenomenal scientific contributions, she was rarely recognized officially for her discoveries. Her discoveries were often credited to wealthy men who bought her fossils.

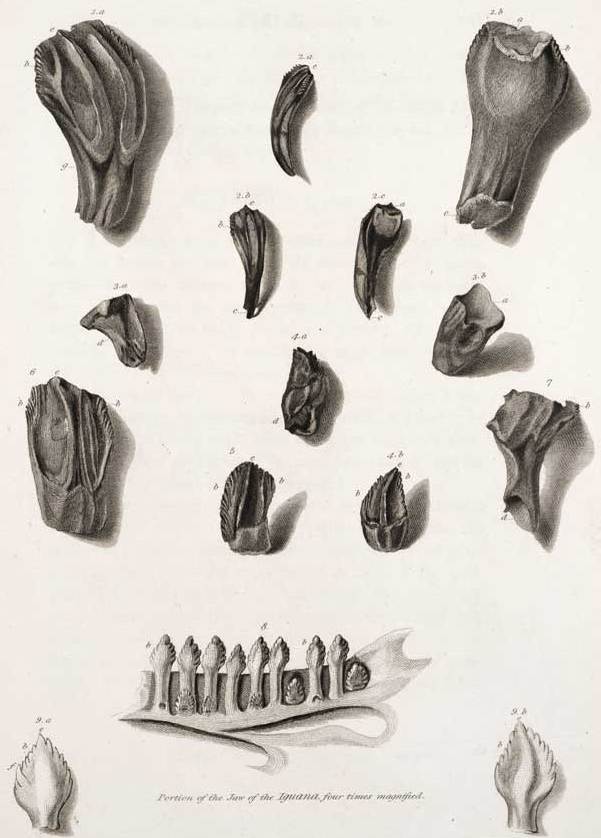

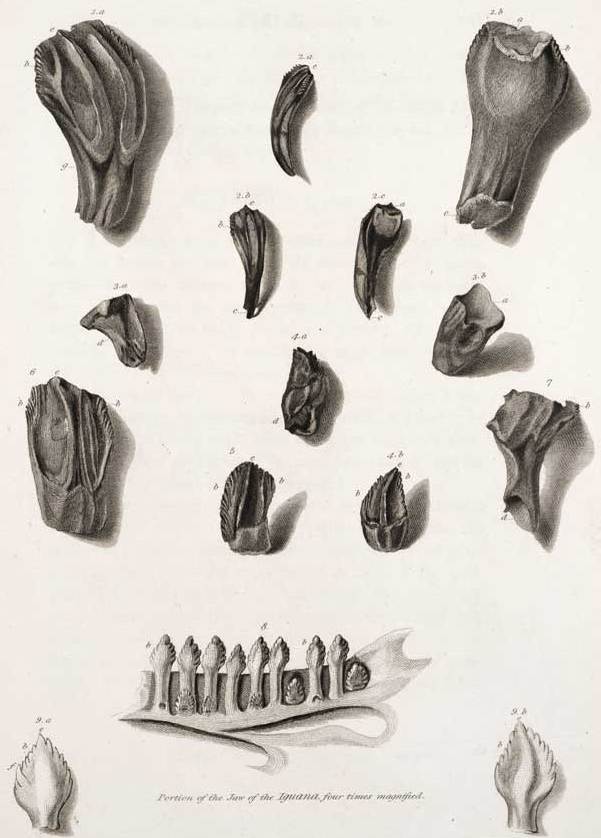

In 1824, Buckland found and described a lower jaw from Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

deposits from Stonesfield

Stonesfield is a village and Civil parishes in England, civil parish about north of Witney in Oxfordshire, and about 10 miles (17 km) north-west of Oxford. The village is on the crest of an escarpment. The parish extends mostly north and ...

. He determined that the bone belonged to a carnivorous land-dwelling reptile he called ''Megalosaurus

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from Greek , ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic period (Bathonian stage, 166 million years a ...

''. That same year Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell MRCS FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was a British obstetrician, geologist and palaeontologist. His attempts to reconstruct the structure and life of ''Iguanodon'' began the scientific study of dinosaurs: in ...

realized that some large teeth he had found in 1822, in Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

rocks from Tilgate

Tilgate is one of 14 neighbourhoods within the town of Crawley in West Sussex, England. The area contains a mixture of privately developed housing, self-build groups and ex-council housing. It is bordered by the districts of Furnace Green to the ...

, belonged to a giant herbivorous land-dwelling reptile. He called it ''Iguanodon

''Iguanodon'' ( ; meaning 'iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species have been classified in the genus ''Iguanodon'', dating from the late Jurassic Period to the early Cretaceous Period of Asia, Eu ...

'', because the teeth resembled those of an iguana

''Iguana'' (, ) is a genus of herbivorous lizards that are native to tropical areas of Mexico, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. The genus was first described in 1768 by Austrian naturalist Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti in his bo ...

. All of this led Mantell to publish an influential paper in 1831 entitled "The Age of Reptiles" in which he summarized the evidence for there having been an extended time during which the earth had teemed with large reptiles, and he divided that era, based in what rock strata different types of reptiles first appeared, into three intervals that anticipated the modern periods of the Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

, Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

, and Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

. In 1832 Mantell would find, in Tilgate, a partial skeleton of an armored reptile he would call ''Hylaeosaurus

''Hylaeosaurus'' ( ; Greek: / "belonging to the forest" and / "lizard") is a herbivorous ankylosaurian dinosaur that lived about 136 million years ago, in the late Valanginian stage of the early Cretaceous period of England. It was found in ...

''. In 1841 the English anatomist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

would create a new order of reptiles, which he called Dinosauria, for ''Megalosaurus'', ''Iguanodon'', and ''Hylaeosaurus''.

This evidence that giant reptiles had lived on Earth in the past caused great excitement in scientific circles, and even among some segments of the general public. Buckland did describe the jaw of a small primitive mammal, ''Phascolotherium'', that was found in the same strata as ''Megalosaurus''. This discovery, known as the Stonesfield mammal, was a much discussed anomaly. Cuvier at first thought it was a

This evidence that giant reptiles had lived on Earth in the past caused great excitement in scientific circles, and even among some segments of the general public. Buckland did describe the jaw of a small primitive mammal, ''Phascolotherium'', that was found in the same strata as ''Megalosaurus''. This discovery, known as the Stonesfield mammal, was a much discussed anomaly. Cuvier at first thought it was a marsupial

Marsupials are any members of the mammalian infraclass Marsupialia. All extant marsupials are endemic to Australasia, Wallacea and the Americas. A distinctive characteristic common to most of these species is that the young are carried in a po ...

, but Buckland later realized it was a primitive placental mammal

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguishe ...

. Due to its small size and primitive nature, Buckland did not believe it invalidated the overall pattern of an age of reptiles, when the largest and most conspicuous animals had been reptiles rather than mammals.

Catastrophism, uniformitarianism and the fossil record

In Cuvier's landmark 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, he referred to a single catastrophe that destroyed life to be replaced by the current forms. As a result of his studies of extinct mammals, he realized that animals such as ''Palaeotherium

''Palaeotherium'' (Ancient Greek for 'old beast') is an extinct genus of perissodactyl ungulate known from the Mid Eocene to earliest Oligocene of Europe. First described by French naturalist Georges Cuvier in 1804, ''Palaeotherium'' was among t ...

'' had lived before the time of the mammoths, which led him to write in terms of multiple geological catastrophes that had wiped out a series of successive faunas. By 1830, a scientific consensus

Scientific consensus is the generally held judgment, position, and opinion of the majority or the supermajority of scientists in a particular field of study at any particular time.

Consensus is achieved through scholarly communication at confe ...

had formed around his ideas as a result of paleobotany and the dinosaur and marine reptile discoveries in Britain. In Great Britain, where natural theology

Natural theology, once also termed physico-theology, is a type of theology that seeks to provide arguments for theological topics (such as the existence of a deity) based on reason and the discoveries of science.

This distinguishes it from ...

was very influential in the early 19th century, a group of geologists that included Buckland, and Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson FRS FRSE (11 July 1774 – 19 April 1854) was a Scottish naturalist and mineralogist.

As Regius Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh for fifty years, developing his predecessor John ...

insisted on explicitly linking the most recent of Cuvier's catastrophes to the biblical flood

The Genesis flood narrative (chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis) is the Hebrew version of the universal flood myth. It tells of God's decision to return the universe to its pre- creation state of watery chaos and remake it through the microc ...

. Catastrophism had a religious overtone in Britain that was absent elsewhere.

Partly in response to what he saw as unsound and unscientific speculations by William Buckland

William Buckland Doctor of Divinity, DD, Royal Society, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full ...

and other practitioners of flood geology, Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

advocated the geological theory of uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

in his influential work ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830–1833. Ly ...

''. Lyell amassed evidence, both from his own field research and the work of others, that most geological features could be explained by the slow action of present-day forces, such as vulcanism, earthquakes

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

, erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is distin ...

, and sedimentation

Sedimentation is the deposition of sediments. It takes place when particles in suspension settle out of the fluid in which they are entrained and come to rest against a barrier. This is due to their motion through the fluid in response to the ...

rather than past catastrophic events.McGowan pp. 100–103 Lyell also claimed that the apparent evidence for catastrophic changes in the fossil record, and even the appearance of directional succession in the history of life, were illusions caused by imperfections in that record. For instance he argued that the absence of birds and mammals from the earliest fossil strata was merely an imperfection in the fossil record attributable to the fact that marine organisms were more easily fossilized. Also Lyell pointed to the Stonesfield mammal as evidence that mammals had not necessarily been preceded by reptiles, and to the fact that certain Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

strata showed a mixture of extinct and still surviving species, which he said showed that extinction occurred piecemeal rather than as a result of catastrophic events. Lyell was successful in convincing geologists of the idea that the geological features of the earth were largely due to the action of the same geologic forces that could be observed in the present day, acting over an extended period of time. He was not successful in gaining support for his view of the fossil record, which he believed did not support a theory of directional succession.

Transmutation of species and the fossil record

In the early 19th centuryJean Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolog ...

used fossils to argue for his theory of the transmutation of species. Fossil finds, and the emerging evidence that life had changed over time, fueled speculation on this topic during the next few decades. Robert Chambers used fossil evidence in his 1844 popular science book ''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' is an 1844 work of speculative natural history and philosophy by Robert Chambers. Published anonymously in England, it brought together various ideas of stellar evolution with the progressive tra ...

'', which advocated an evolutionary origin for the cosmos as well as for life on earth. Like Lamarck's theory it maintained that life had progressed from the simple to the complex. These early evolutionary ideas were widely discussed in scientific circles but were not accepted into the scientific mainstream. Many of the critics of transmutational ideas used fossil evidence in their arguments. In the same paper that coined the term dinosaur Richard Owen pointed out that dinosaurs were at least as sophisticated and complex as modern reptiles, which he claimed contradicted transmutational theories. Hugh Miller

Hugh Miller (10 October 1802 – 23/24 December 1856) was a self-taught Scottish geologist and writer, folklorist and an evangelical Christian.

Life and work

Miller was born in Cromarty, the first of three children of Harriet Wright (''b ...

would make a similar argument, pointing out that the fossil fish found in the Old Red Sandstone

The Old Red Sandstone is an assemblage of rocks in the North Atlantic region largely of Devonian age. It extends in the east across Great Britain, Ireland and Norway, and in the west along the northeastern seaboard of North America. It also exte ...

formation were fully as complex as any later fish, and not the primitive forms alleged by ''Vestiges''. While these early evolutionary theories failed to become accepted as mainstream science, the debates over them would help pave the way for the acceptance of Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection a few years later.

Geological time scale and the history of life

Geologists such asAdam Sedgwick

Adam Sedgwick (; 22 March 1785 – 27 January 1873) was a British geologist and Anglican priest, one of the founders of modern geology. He proposed the Cambrian and Devonian period of the geological timescale. Based on work which he did on W ...

, and Roderick Murchison

Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, 1st Baronet, (19 February 1792 – 22 October 1871) was a Scotland, Scottish geologist who served as director-general of the British Geological Survey from 1855 until his death in 1871. He is noted for investigat ...

continued, in the course of disputes such as The Great Devonian Controversy

The Great Devonian Controversy began in 1834 when Roderick Murchison disagreed with Henry De la Beche as to the dating of certain petrified plants found in coals in the Greywacke stratum in North Devon, England. De La Beche was claiming that sinc ...

, to make advances in stratigraphy. They described newly recognized geological periods, such as the Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized C with bar, Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million ...

, the Silurian

The Silurian ( ) is a geologic period and system spanning 24.6 million years from the end of the Ordovician Period, at million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Devonian Period, Mya. The Silurian is the shortest period of the Paleozo ...

, the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, whe ...

, and the Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleoz ...

. Increasingly, such progress in stratigraphy depended on the opinions of experts with specialized knowledge of particular types of fossils such as William Lonsdale

William Lonsdale (9 September 1794 in Bath, Somerset, Bath11 November 1871 in Bristol), English geologist and palaeontologist, won the Wollaston Medal, Wollaston medal in 1846 for his research on the various kinds of fossil corals.

Biography

H ...

(fossil corals), and John Lindley

John Lindley FRS (5 February 1799 – 1 November 1865) was an English botanist, gardener and orchidologist.

Early years

Born in Catton, near Norwich, England, John Lindley was one of four children of George and Mary Lindley. George Lindley w ...

(fossil plants) who both played a role in the Devonian controversy and its resolution. By the early 1840s much of the geologic time scale had been developed. In 1841, John Phillips formally divided the geologic column into three major eras, the Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ' ...

, Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceo ...

, and Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configura ...

, based on sharp breaks in the fossil record. He identified the three periods of the Mesozoic era and all the periods of the Paleozoic era except the Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and System (geology), system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era (geology), Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start ...

. His definition of the geological time scale is still used today. It remained a relative time scale with no method of assigning any of the periods' absolute dates. It was understood that not only had there been an "age of reptiles" preceding the current "age of mammals", but there had been a time (during the Cambrian and the Silurian) when life had been restricted to the sea, and a time (prior to the Devonian) when invertebrates had been the largest and most complex forms of animal life.

Expansion and professionalization of geology and paleontology