History of geodesy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of geodesy deals with the historical development of measurements and representations of the Earth. The corresponding scientific discipline, '' geodesy'' ( /dʒiːˈɒdɪsi/), began in pre-scientific antiquity and blossomed during the

Eratosthenes' method to calculate the

Eratosthenes' method to calculate the

Materialien und Dokumente zur mittelalterlichen Erdkugeltheorie von der Spätantike bis zur Kolumbusfahrt (1492)

Direct adoption by India: D. Pingree: "History of Mathematical Astronomy in India", ''Dictionary of Scientific Biography'', Vol. 15 (1978), pp. 533–633 (554f.); Glick, Thomas F., Livesey, Steven John, Wallis, Faith (eds.): "Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia", Routledge, New York 2005, , p. 463Adoption by China via European science: and In the West, the idea came to the Romans through the lengthy process of cross-fertilization with

"Ein Versuch über die Archäologie der Globalisierung. Die Kugelgestalt der Erde und die globale Konzeption des Erdraums im Mittelalter"

''Wechselwirkungen'', Jahrbuch aus Lehre und Forschung der Universität Stuttgart, University of Stuttgart, 2007, pp. 28–52 (35–36) Pliny also considered the possibility of an imperfect sphere "shaped like a pinecone".

"Ein Versuch über die Archäologie der Globalisierung. Die Kugelgestalt der Erde und die globale Konzeption des Erdraums im Mittelalter"

''Wechselwirkungen'', Jahrbuch aus Lehre und Forschung der Universität Stuttgart, University of Stuttgart, 2007, pp. 28–52 (35–36) Revising the figures attributed to Posidonius, another Greek philosopher determined as the Earth's circumference. This last figure was promulgated by

During the

During the

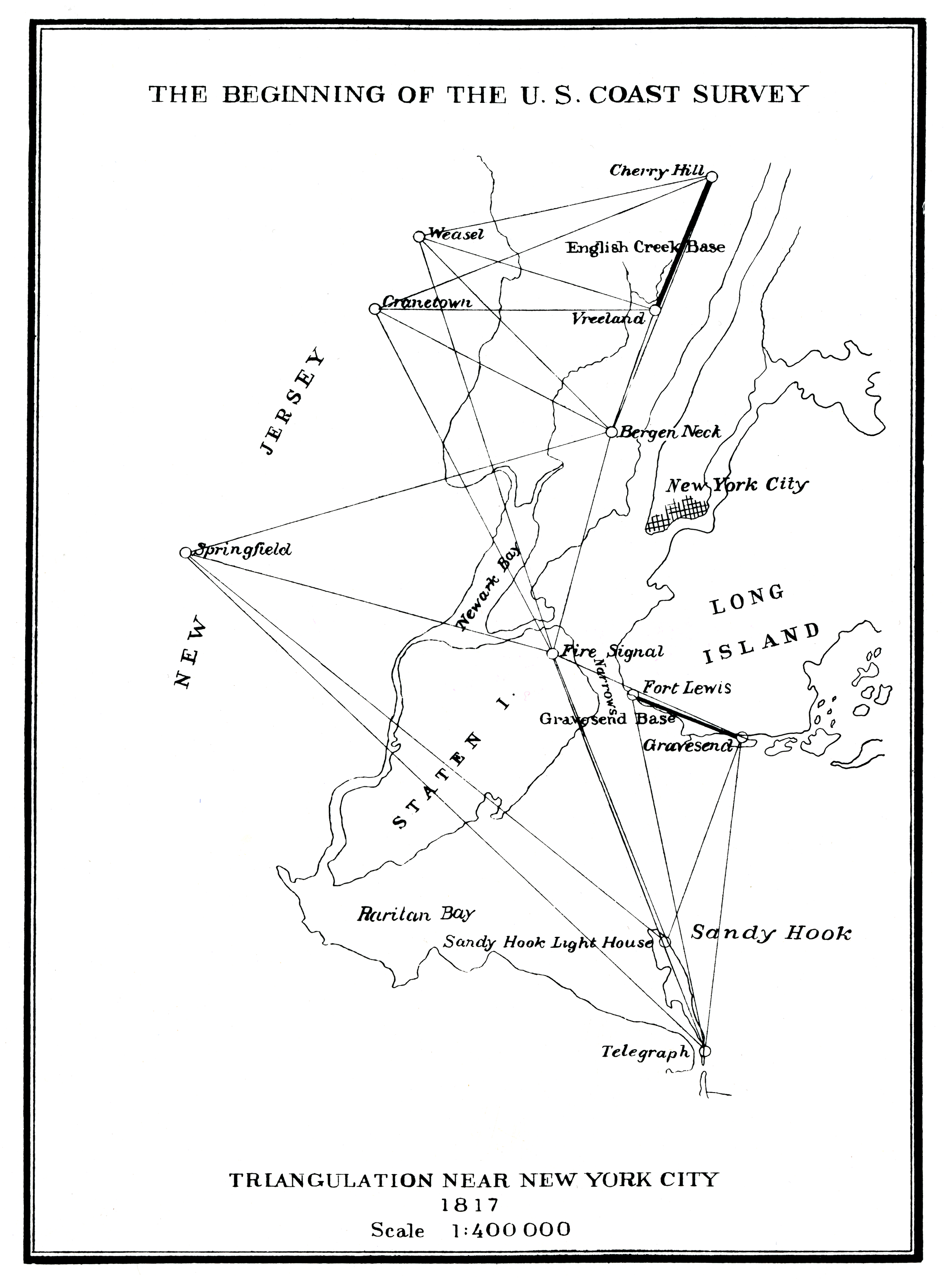

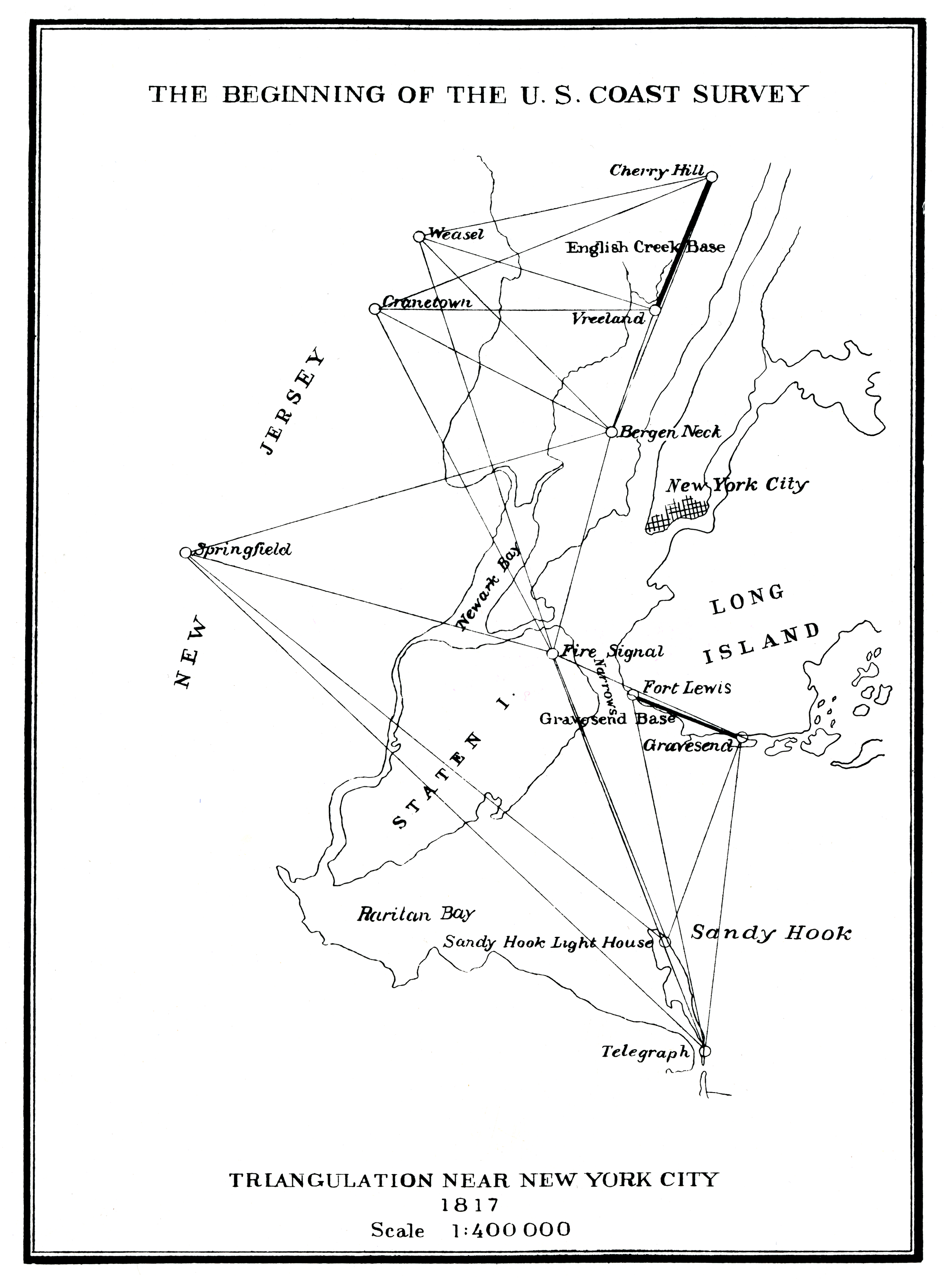

In 1811 Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler was selected to direct the

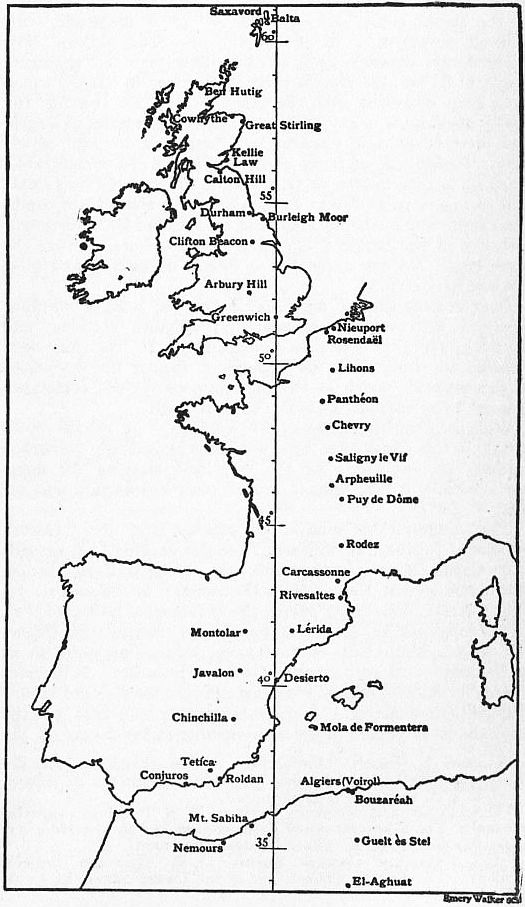

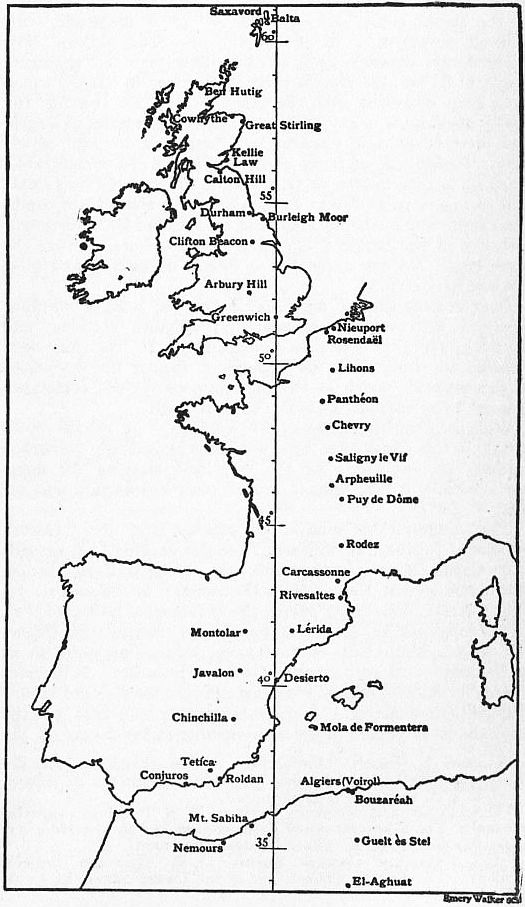

In 1811 Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler was selected to direct the  The Scandinavian-Russian meridian arc or Struve Geodetic Arc, named after the German astronomer

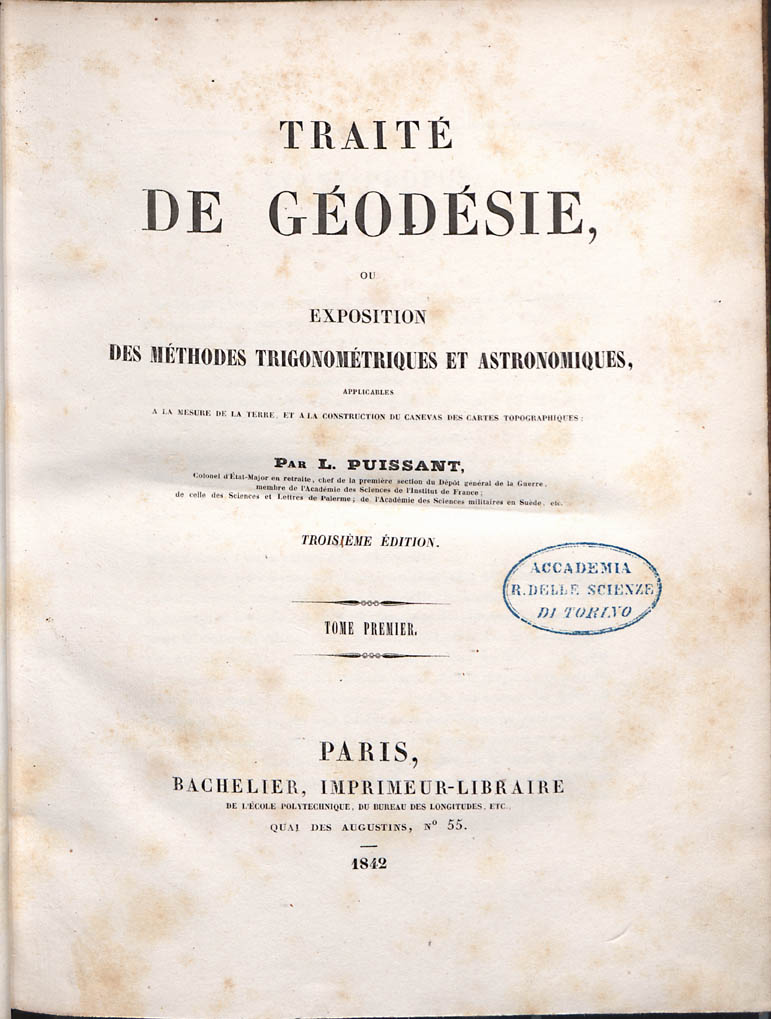

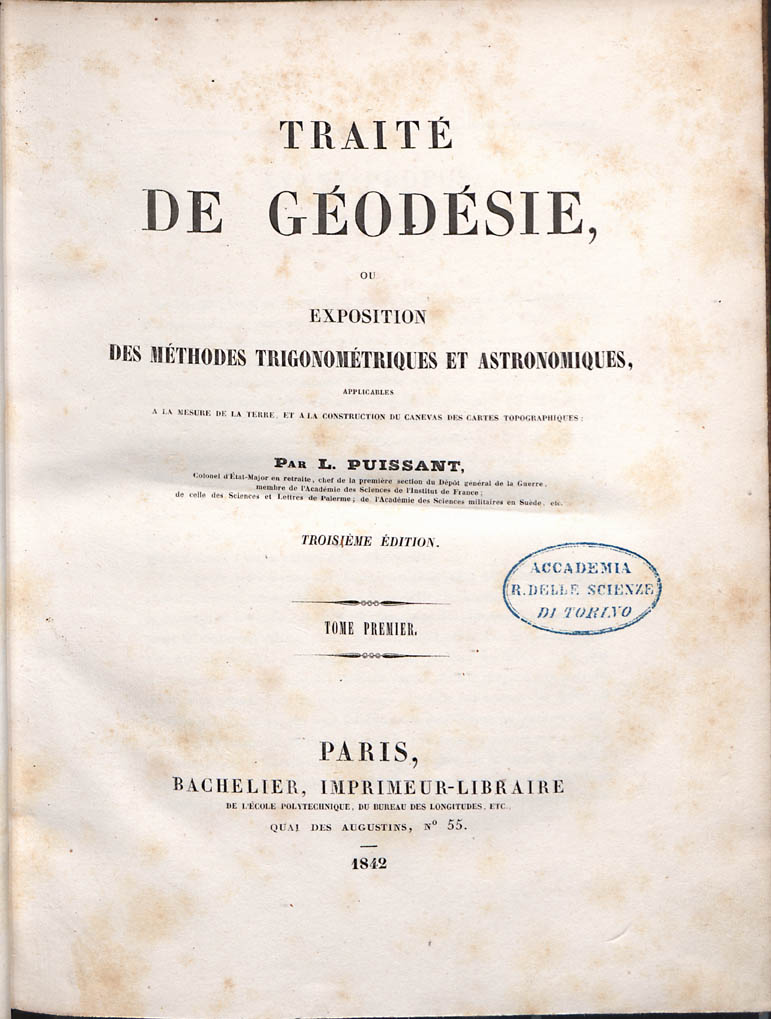

The Scandinavian-Russian meridian arc or Struve Geodetic Arc, named after the German astronomer  Louis Puissant declared in 1836 in front of the French Academy of Sciences that Delambre and Méchain had made an error in the measurement of the French meridian arc. Some thought that the base of the metric system could be attacked by pointing out some errors that crept into the measurement of the two French scientists. Méchain had even noticed an inaccuracy he did not dare to admit. As this survey was also part of the groundwork for the map of France, Antoine Yvon Villarceau checked, from 1861 to 1866, the geodesic opérations in eight points of the meridian arc. Some of the errors in the operations of Delambre and Méchain were corrected. In 1866, at the conference of the

Louis Puissant declared in 1836 in front of the French Academy of Sciences that Delambre and Méchain had made an error in the measurement of the French meridian arc. Some thought that the base of the metric system could be attacked by pointing out some errors that crept into the measurement of the two French scientists. Méchain had even noticed an inaccuracy he did not dare to admit. As this survey was also part of the groundwork for the map of France, Antoine Yvon Villarceau checked, from 1861 to 1866, the geodesic opérations in eight points of the meridian arc. Some of the errors in the operations of Delambre and Méchain were corrected. In 1866, at the conference of the

As Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero stated. If precision metrology had needed the help of geodesy, it could not continue to prosper without the help of metrology. Indeed, how to express all the measurements of terrestrial arcs as a function of a single unit, and all the determinations of the force of gravity with the

As Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero stated. If precision metrology had needed the help of geodesy, it could not continue to prosper without the help of metrology. Indeed, how to express all the measurements of terrestrial arcs as a function of a single unit, and all the determinations of the force of gravity with the

In 1804

In 1804

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

.

Early ideas about the figure of the Earth held the Earth to be flat (see flat Earth

The flat-Earth model is an archaic and scientifically disproven conception of Earth's shape as a plane or disk. Many ancient cultures subscribed to a flat-Earth cosmography, including Greece until the classical period (5th century BC), t ...

), and the heavens a physical dome spanning over it. Two early arguments for a spherical Earth were that lunar eclipses were seen as circular shadows which could only be caused by a spherical Earth, and that Polaris is seen lower in the sky as one travels South.

Hellenic world

Initial development from a diversity of views

Though the earliest written mention of a spherical Earth comes fromancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

sources, there is no account of how the sphericity of Earth was discovered, or if it was initially simply a guess.James Evans, (1998), ''The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy'', page 47, Oxford University Press A plausible explanation given by the historian Otto E. Neugebauer is that it was "the experience of travellers that suggested such an explanation for the variation in the observable altitude

Altitude or height (also sometimes known as depth) is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum and a point or object. The exact definition and reference datum varies according to the context ...

of the pole and the change in the area of circumpolar stars, a change that was quite drastic between Greek settlements" around the eastern Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

, particularly those between the Nile Delta and Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

.

Another possible explanation can be traced back to earlier Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

n sailors. The first circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical body (e.g. a planet or moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circumnavigation of the Earth was the Mage ...

of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

is described as being undertaken by Phoenician explorers employed by Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

Necho II

Necho II (sometimes Nekau, Neku, Nechoh, or Nikuu; Greek: Νεκώς Β'; ) of Egypt was a king of the 26th Dynasty (610–595 BC), which ruled from Sais. Necho undertook a number of construction projects across his kingdom. In his reign, accordi ...

c. 610–595 BC. In ''The Histories'', written 431–425 BC, Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society ...

cast doubt on a report of the Sun observed shining from the north. He stated that the phenomenon was observed by Phoenician explorers during their circumnavigation of Africa ( ''The Histories'', 4.42) who claimed to have had the Sun on their right when circumnavigating in a clockwise direction. To modern historians, these details confirm the truth of the Phoenicians' report. The historian Dmitri Panchenko hypothesizes that it was the Phoenician circumnavigation of Africa that inspired the theory of a spherical Earth, the earliest mention of which was made by the philosopher Parmenides in the 5th century BC. However, nothing certain about their knowledge of geography and navigation has survived; therefore, later researchers have no evidence that they conceived of Earth as spherical.

Speculation and theorizing ranged from the flat disc advocated by Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

to the spherical body reportedly postulated by Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His politi ...

. Anaximenes, an early Greek philosopher, believed strongly that the Earth was rectangular

In Euclidean plane geometry, a rectangle is a quadrilateral with four right angles. It can also be defined as: an equiangular quadrilateral, since equiangular means that all of its angles are equal (360°/4 = 90°); or a parallelogram containin ...

in shape. Some early Greek philosophers alluded to a spherical Earth, though with some ambiguity. Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His politi ...

(6th century BC) was among those said to have originated the idea, but this might reflect the ancient Greek practice of ascribing every discovery to one or another of their ancient wise men. Pythagoras was a mathematician, and he supposedly reasoned that the gods would create a perfect figure which to him was a sphere

A sphere () is a geometrical object that is a three-dimensional analogue to a two-dimensional circle. A sphere is the set of points that are all at the same distance from a given point in three-dimensional space.. That given point is th ...

. Some idea of the sphericity of Earth seems to have been known to both Parmenides and Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the ...

in the 5th century BC, Charles H. Kahn, (2001), ''Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans: a brief history'', page 53. Hackett and although the idea cannot reliably be ascribed to Pythagoras, it might nevertheless have been formulated in the Pythagorean school in the 5th century BC although some disagree. After the 5th century BC, no Greek writer of repute thought the world was anything but round. The Pythagorean idea was supported later by Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

. Efforts commenced to determine the size of the sphere.

Plato

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

(427–347 BC) travelled to southern Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

to study Pythagorean mathematics. When he returned to Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

and established his school, Plato also taught his students that Earth was a sphere, though he offered no justifications. "My conviction is that the Earth is a round body in the centre of the heavens, and therefore has no need of air or of any similar force to be a support." If man could soar high above the clouds, Earth would resemble "one of those balls which have leather coverings in twelve pieces, and is decked with various colours, of which the colours used by painters on Earth are in a manner samples." In ''Timaeus'', his one work that was available throughout the Middle Ages in Latin, he wrote that the Creator "made the world in the form of a globe, round as from a lathe, having its extremes in every direction equidistant from the centre, the most perfect and the most like itself of all figures", though the word "world" here refers to the heavens.

Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

(384–322 BC) was Plato's prize student and "the mind of the school". Aristotle observed "there are stars seen in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

and ..Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ge ...

which are not seen in the northerly regions". Since this could only happen on a curved surface, he too believed Earth was a sphere "of no great size, for otherwise the effect of so slight a change of place would not be quickly apparent".

Aristotle reported the circumference of the Earth (which is actually slightly over 40,000 km) to be 400,000 stadia

Stadia may refer to:

* One of the plurals of stadium, along with "stadiums"

* The plural of stadion, an ancient Greek unit of distance, which equals to 600 Greek feet (''podes'').

* Stadia (Caria), a town of ancient Caria, now in Turkey

* Stadi ...

.

Aristotle provided physical and observational arguments supporting the idea of a spherical Earth:

* Every portion of Earth tends toward the centre until by compression and convergence they form a sphere.

* Travelers going south see southern constellations rise higher above the horizon.

* The shadow of Earth on the Moon during a lunar eclipse is round.

The concepts of symmetry, equilibrium and cyclic repetition permeated Aristotle's work. In his ''Meteorology'' he divided the world into five climatic zones: two temperate areas separated by a torrid zone near the equator, and two cold inhospitable regions, "one near our upper or northern pole and the other near the ..southern pole", both impenetrable and girdled with ice. Although no humans could survive in the frigid zones, inhabitants in the southern temperate regions could exist.

Aristotle's theory of natural place relied on a spherical Earth to explain why heavy things go down (toward what Aristotle believed was the center of the Universe), and things like air

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing f ...

and fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a material (the fuel) in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction products.

At a certain point in the combustion reaction, called the ignition point, flames a ...

go up. In this geocentric model, the structure of the universe was believed to be a series of perfect spheres. The Sun, Moon, planets and fixed stars were believed to move on celestial spheres

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the apparent motions of the fixed stars ...

around a stationary Earth.

Though Aristotle's theory of physics survived in the Christian world for many centuries, the heliocentric model

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth a ...

was eventually shown to be a more correct explanation of the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

than the geocentric model, and atomic theory

Atomic theory is the scientific theory that matter is composed of particles called atoms. Atomic theory traces its origins to an ancient philosophical tradition known as atomism. According to this idea, if one were to take a lump of matter ...

was shown to be a more correct explanation of the nature of matter than classical elements like earth, water, air, fire, and aether.

Archimedes

Archimedes gave an upper bound for the circumference of the Earth of 3,000,000 stadia (483,000 km or 300,000 mi) using the Hellenic stadion which scholars generally take to be 185 meters or of a geographical mile. In proposition 2 of the First Book of his treatise "On floating bodies", Archimedes demonstrates that "The surface of any fluid at rest is the surface of a sphere whose centre is the same as that of the Earth". Subsequently, in propositions 8 and 9 of the same work, he assumes the result of proposition 2 that Earth is a sphere and that the surface of a fluid on it is a sphere centered on the center of Earth.Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes (276–194 BC), a Hellenistic astronomer from what is nowCyrene, Libya

Cyrene ( ) or Kyrene ( ; grc, Κυρήνη, Kyrḗnē, arb, شحات, Shaḥāt), was an ancient Greek and later Roman city near present-day Shahhat, Libya. It was the oldest and most important of the five Greek cities, known as the pentapol ...

working in Alexandria, Egypt

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, estimated Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

's circumference around 240 BC, computing a value of 252,000 '' stades''. The length that Eratosthenes intended for a "stade" is not known, but his figure only has an error of around one to fifteen percent. Assuming a value for the stadion between 155 and 160 metres, the error is between −2.4% and +0.8%. Eratosthenes described his technique in a book entitled ''On the measure of the Earth'', which has not been preserved. Eratosthenes could only measure the circumference of Earth by assuming that the distance to the Sun is so great that the rays of sunlight are practically parallel

Parallel is a geometric term of location which may refer to:

Computing

* Parallel algorithm

* Parallel computing

* Parallel metaheuristic

* Parallel (software), a UNIX utility for running programs in parallel

* Parallel Sysplex, a cluster of ...

.

Earth's circumference

Earth's circumference is the distance around Earth. Measured around the Equator, it is . Measured around the poles, the circumference is .

Measurement of Earth's circumference has been important to navigation since ancient times. The first kno ...

has been lost; what has been preserved is the simplified version described by Cleomedes to popularise the discovery. Cleomedes invites his reader to consider two Egyptian cities, Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

and Syene

Aswan (, also ; ar, أسوان, ʾAswān ; cop, Ⲥⲟⲩⲁⲛ ) is a city in Southern Egypt, and is the capital of the Aswan Governorate.

Aswan is a busy market and tourist centre located just north of the Aswan Dam on the east bank of t ...

, modern Assuan:

# Cleomedes assumes that the distance between Syene and Alexandria was 5,000 stadia (a figure that was checked yearly by professional bematist

Bematists or bematistae (Ancient Greek βηματισταί (''bēmatistaí'', 'step measurer'), from

βῆμα (''bema'', 'pace')), were specialists in ancient Greece and ancient Egypt who measured distances by pacing.

Measurements of Alexa ...

s, ''mensores regii'');

# he assumes the simplified (but false) hypothesis that Syene was precisely on the Tropic of Cancer

The Tropic of Cancer, which is also referred to as the Northern Tropic, is the most northerly circle of latitude on Earth at which the Sun can be directly overhead. This occurs on the June solstice, when the Northern Hemisphere is tilted tow ...

, saying that at local noon on the summer solstice

A solstice is an event that occurs when the Sun appears to reach its most northerly or southerly excursion relative to the celestial equator on the celestial sphere. Two solstices occur annually, around June 21 and December 21. In many countr ...

the Sun was directly overhead;

# he assumes the simplified (but false) hypothesis that Syene and Alexandria are on the same meridian.

Under the previous assumptions, says Cleomedes, you can measure the Sun's angle of elevation at noon of the summer solstice in Alexandria, by using a vertical rod (a gnomon) of known length and measuring the length of its shadow on the ground; it is then possible to calculate the angle of the Sun's rays, which he claims to be about 7°, or 1/50th the circumference of a circle. Taking the Earth as spherical, the Earth's circumference would be fifty times the distance between Alexandria and Syene, that is 250,000 stadia. Since 1 Egyptian stadium is equal to 157.5 metres, the result is 39,375 km, which is 1.4% less than the real number, 39,941 km.

Eratosthenes' method was actually more complicated, as stated by the same Cleomedes, whose purpose was to present a simplified version of the one described in Eratosthenes' book. The method was based on several surveying trips conducted by professional bematists, whose job was to precisely measure the extent of the territory of Egypt for agricultural and taxation-related purposes. Furthermore, the fact that Eratosthenes' measure corresponds precisely to 252,000 stadia might be intentional, since it is a number that can be divided by all natural numbers from 1 to 10: some historians believe that Eratosthenes changed from the 250,000 value written by Cleomedes to this new value to simplify calculations; other historians of science, on the other side, believe that Eratosthenes introduced a new length unit based on the length of the meridian, as stated by Pliny, who writes about the stadion "according to Eratosthenes' ratio".

1,700 years after Eratosthenes, Christopher Columbus studied Eratosthenes's findings before sailing west for the Indies. However, ultimately he rejected Eratosthenes in favour of other maps and arguments that interpreted Earth's circumference to be a third smaller than it really is. If, instead, Columbus had accepted Eratosthenes' findings, he may have never gone west, since he did not have the supplies or funding needed for the much longer eight-thousand-plus mile voyage.

Seleucus of Seleucia

Seleucus of Seleucia

Seleucus of Seleucia ( el, Σέλευκος ''Seleukos''; born c. 190 BC; fl. c. 150 BC) was a Hellenistic astronomer and philosopher. Coming from Seleucia on the Tigris, Mesopotamia, the capital of the Seleucid Empire, or, alternatively, Seleuk ...

(c. 190 BC), who lived in the city of Seleucia in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, wrote that Earth is spherical (and actually orbits the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

, influenced by the heliocentric theory

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth a ...

of Aristarchus of Samos).

Posidonius

A parallel later ancient measurement of the size of the Earth was made by another Greek scholar,Posidonius

Posidonius (; grc-gre, Ποσειδώνιος , "of Poseidon") "of Apameia" (ὁ Ἀπαμεύς) or "of Rhodes" (ὁ Ῥόδιος) (), was a Greek politician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, historian, mathematician, and teacher nativ ...

(c. 13551 BC), using a similar method as Eratosthenes. Instead of observing the sun, he noted that the star Canopus

Canopus is the brightest star in the southern constellation of Carina and the second-brightest star in the night sky. It is also designated α Carinae, which is Latinised to Alpha Carinae. With a visual apparent magnitude ...

was hidden from view in most parts of Greece but that it just grazed the horizon at Rhodes. Posidonius is supposed to have measured the angular elevation of Canopus at Alexandria and determined that the angle was 1/48 of a circle. He used a distance from Alexandria to Rhodes, 5000 stadia, and so he computed the Earth's circumference in stadia as 48 × 5000 = 240,000. Some scholars see these results as luckily semi-accurate due to cancellation of errors. But since the Canopus observations are both mistaken by over a degree, the "experiment" may be not much more than a recycling of Eratosthenes's numbers, while altering 1/50 to the correct 1/48 of a circle. Later, either he or a follower appears to have altered the base distance to agree with Eratosthenes's Alexandria-to-Rhodes figure of 3750 stadia, since Posidonius' final circumference was 180,000 stadia, which equals 48 × 3750 stadia. The 180,000 stadia circumference of Posidonius is suspiciously close to that which results from another method of measuring the Earth, by timing ocean sunsets from different heights, a method which is inaccurate due to horizontal atmospheric refraction

Atmospheric refraction is the deviation of light or other electromagnetic wave from a straight line as it passes through the atmosphere due to the variation in air density as a function of height. This refraction is due to the velocity of ligh ...

. Posidonius furthermore expressed the distance of the Sun in Earth radii.

The above-mentioned larger and smaller sizes of the Earth were those used by later Roman author Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importa ...

at different times: 252,000 stadia in his '' Almagest'' and 180,000 stadia in his later ''Geographia

The ''Geography'' ( grc-gre, Γεωγραφικὴ Ὑφήγησις, ''Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis'', "Geographical Guidance"), also known by its Latin names as the ' and the ', is a gazetteer, an atlas, and a treatise on cartography, com ...

''. His mid-career conversion resulted in the latter work's systematic exaggeration of degree longitudes in the Mediterranean by a factor close to the ratio of the two seriously differing sizes discussed here, which indicates that the conventional size of the Earth was what changed, not the stadion.

Ancient India

While the textual evidence has not survived, the precision of the constants used in pre-Greek ''Vedanga

The Vedanga ( sa, वेदाङ्ग ', "limbs of the Veda") are six auxiliary disciplines of Hinduism that developed in ancient times and have been connected with the study of the Vedas:James Lochtefeld (2002), "Vedanga" in The Illustrated Enc ...

'' models, and the model's accuracy in predicting the Moon and Sun's motion for Vedic rituals, probably came from direct astronomical observations. The cosmographic theories and assumptions in ancient India likely developed independently and in parallel, but these were influenced by some unknown quantitative Greek astronomy text in the medieval era.

Greek ethnographer Megasthenes

Megasthenes ( ; grc, Μεγασθένης, c. 350 BCE– c. 290 BCE) was an ancient Greek historian, diplomat and Indian ethnographer and explorer in the Hellenistic period. He described India in his book '' Indica'', which is now lost, but ha ...

, c. 300 BC, has been interpreted as stating that the contemporary Brahmans believed in a spherical Earth as the center of the universe. With the spread of Hellenistic culture

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

in the east, Hellenistic astronomy

Greek astronomy is astronomy written in the Greek language in classical antiquity. Greek astronomy is understood to include the Ancient Greek, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman, and Late Antiquity eras. It is not limited geographically to Greece or to eth ...

filtered eastwards to ancient India

According to consensus in modern genetics, anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. Quote: "Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonization of South Asia by m ...

where its profound influence became apparent in the early centuries AD. The Greek concept of an Earth surrounded by the spheres of the planets and that of the fixed stars, vehemently supported by astronomers like Varāhamihira

Varāhamihira ( 505 – 587), also called Varāha or Mihira, was an ancient Indian astrologer, astronomer, and polymath who lived in Ujjain (Madhya Pradesh, India). He was born at Kapitba in a Brahmin family, in the Avanti region, roughly co ...

and Brahmagupta, strengthened the astronomical principles. Some ideas were found possible to preserve, although in altered form.D. Pingree: "History of Mathematical Astronomy in India", ''Dictionary of Scientific Biography'', Vol. 15 (1978), pp. 533–633 (533, 554f.) "Chapter 6. Cosmology"

The Indian astronomer and mathematician Aryabhata

Aryabhata ( ISO: ) or Aryabhata I (476–550 CE) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer of the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy. He flourished in the Gupta Era and produced works such as the ''Aryabhatiya'' (which ...

(476–550 CE) was a pioneer of mathematical astronomy on the subcontinent. He describes the Earth as being spherical and says that it rotates on its axis, among other places in his Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

magnum opus, ''Āryabhaṭīya

''Aryabhatiya'' (IAST: ') or ''Aryabhatiyam'' ('), a Indian astronomy, Sanskrit astronomical treatise, is the ''Masterpiece, magnum opus'' and only known surviving work of the 5th century Indian mathematics, Indian mathematician Aryabhata. Philos ...

''. ''Aryabhatiya'' is divided into four sections: ''Gitika'', ''Ganitha'' ("mathematics"), ''Kalakriya'' ("reckoning of time") and ''Gola'' (" celestial sphere"). The discovery that the Earth rotates on its own axis from west to east is described in ''Aryabhatiya'' (Gitika 3,6; Kalakriya 5; Gola 9,10). For example, he explained the apparent motion of heavenly bodies as only an illusion (Gola 9), with the following simile:

:Just as a passenger in a boat moving downstream sees the stationary (trees on the river banks) as traversing upstream, so does an observer on earth see the fixed stars as moving towards the west at exactly the same speed (at which the earth moves from west to east.)

Aryabhatiya also estimates the circumference of the Earth. He gives this as 4967 yojanas and its diameter as 1581 yojanas. The length of a yojana varies considerably between sources; assuming a yojana to be 8 km (4.97097 miles) this gives a circumference of , close to the current equatorial value of .

Roman Empire

The idea of a spherical Earth slowly spread across the globe, and ultimately became the adopted view in all major astronomical traditions.Continuation into Roman and medieval thought: Reinhard Krüger:Materialien und Dokumente zur mittelalterlichen Erdkugeltheorie von der Spätantike bis zur Kolumbusfahrt (1492)

Direct adoption by India: D. Pingree: "History of Mathematical Astronomy in India", ''Dictionary of Scientific Biography'', Vol. 15 (1978), pp. 533–633 (554f.); Glick, Thomas F., Livesey, Steven John, Wallis, Faith (eds.): "Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia", Routledge, New York 2005, , p. 463Adoption by China via European science: and In the West, the idea came to the Romans through the lengthy process of cross-fertilization with

Hellenistic civilization

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

. Many Roman authors such as Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

and Pliny

Pliny may refer to:

People

* Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), ancient Roman nobleman, scientist, historian, and author of ''Naturalis Historia'' (''Pliny's Natural History'')

* Pliny the Younger (died 113), ancient Roman statesman, orator, w ...

refer in their works to the rotundity of Earth as a matter of course.Krüger, Reinhard"Ein Versuch über die Archäologie der Globalisierung. Die Kugelgestalt der Erde und die globale Konzeption des Erdraums im Mittelalter"

''Wechselwirkungen'', Jahrbuch aus Lehre und Forschung der Universität Stuttgart, University of Stuttgart, 2007, pp. 28–52 (35–36) Pliny also considered the possibility of an imperfect sphere "shaped like a pinecone".

Strabo

It has been suggested that seafarers probably provided the first observational evidence that Earth was not flat, based on observations of the horizon. This argument was put forward by the geographer Strabo (c. 64 BC – 24 AD), who suggested that the spherical shape of Earth was probably known to seafarers around theMediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

since at least the time of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

,Hugh Thurston, ''Early Astronomy'', (New York: Springer-Verlag), p. 118. . citing a line from the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Iliad'', th ...

'' as indicating that the poet Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

knew of this as early as the 7th or 8th century BC. Strabo cited various phenomena observed at sea as suggesting that Earth was spherical. He observed that elevated lights or areas of land were visible to sailors at greater distances than those less elevated, and stated that the curvature of the sea was obviously responsible for this.

Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importa ...

(90–168 AD) lived in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, the centre of scholarship in the 2nd century. In the '' Almagest'', which remained the standard work of astronomy for 1,400 years, he advanced many arguments for the spherical nature of Earth. Among them was the observation that when a ship is sailing towards mountain

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually highe ...

s, observers note these seem to rise from the sea, indicating that they were hidden by the curved surface of the sea. He also gives separate arguments that Earth is curved north-south and that it is curved east-west.

He compiled an eight-volume ''Geographia

The ''Geography'' ( grc-gre, Γεωγραφικὴ Ὑφήγησις, ''Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis'', "Geographical Guidance"), also known by its Latin names as the ' and the ', is a gazetteer, an atlas, and a treatise on cartography, com ...

'' covering what was known about Earth. The first part of the ''Geographia'' is a discussion of the data and of the methods he used. As with the model of the Solar System in the ''Almagest'', Ptolemy put all this information into a grand scheme. He assigned coordinate

In geometry, a coordinate system is a system that uses one or more numbers, or coordinates, to uniquely determine the position of the points or other geometric elements on a manifold such as Euclidean space. The order of the coordinates is sign ...

s to all the places and geographic features he knew, in a grid

Grid, The Grid, or GRID may refer to:

Common usage

* Cattle grid or stock grid, a type of obstacle is used to prevent livestock from crossing the road

* Grid reference, used to define a location on a map

Arts, entertainment, and media

* News ...

that spanned the globe (although most of this has been lost). Latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

was measured from the equator, as it is today, but Ptolemy preferred to express it as the length of the longest day rather than degrees of arc

A degree (in full, a degree of arc, arc degree, or arcdegree), usually denoted by ° (the degree symbol), is a measurement of a plane angle in which one full rotation is 360 degrees.

It is not an SI unit—the SI unit of angular measure is th ...

(the length of the midsummer

Midsummer is a celebration of the season of summer usually held at a date around the summer solstice. It has pagan pre-Christian roots in Europe.

The undivided Christian Church designated June 24 as the feast day of the early Christian martyr ...

day increases from 12h to 24h as you go from the equator to the polar circle

A polar circle is a geographic term for a conditional circular line (arc) referring either to the Arctic Circle or the Antarctic Circle. These are two of the keynote circles of latitude (parallels). On Earth, the Arctic Circle is currently d ...

). He put the meridian

Meridian or a meridian line (from Latin ''meridies'' via Old French ''meridiane'', meaning “midday”) may refer to

Science

* Meridian (astronomy), imaginary circle in a plane perpendicular to the planes of the celestial equator and horizon

* ...

of 0 longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east– west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lette ...

at the most western land he knew, the Canary Islands.

''Geographia'' indicated the countries of "Serica

Serica (, grc, Σηρικά) was one of the easternmost countries of Asia known to the Ancient Greek and Roman geographers. It is generally taken as referring to North China during its Zhou, Qin, and Han dynasties, as it was reached via ...

" and "Sinae" ( China) at the extreme right, beyond the island of "Taprobane" ( Sri Lanka, oversized) and the "Aurea Chersonesus" ( Southeast Asian peninsula).

Ptolemy also devised and provided instructions on how to make maps both of the whole inhabited world (''oikoumenè'') and of the Roman provinces. In the second part of the ''Geographia'', he provided the necessary topographic

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the land forms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary scien ...

lists, and captions for the maps. His ''oikoumenè'' spanned 180 degrees of longitude from the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

to China, and about 81 degrees of latitude from the Arctic to the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

and deep into Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. Ptolemy was well aware that he knew about only a quarter of the globe.

Late Antiquity

Knowledge of the spherical shape of Earth was received in scholarship ofLate Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

as a matter of course, in both Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some i ...

and Early Christianity

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewis ...

. Calcidius

Calcidius (or Chalcidius) was a 4th-century philosopher (and possibly a Christians, Christian) who translated the first part (to 53c) of Plato's ''Timaeus (dialogue), Timaeus'' from Greek (language), Greek into Latin around the year 321 and provid ...

's fourth-century Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

commentary on and translation of Plato's ''Timaeus'', which was one of the few examples of Greek scientific thought that was known in the Early Middle Ages in Western Europe, discussed Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equi ...

's use of the geometrical circumstances of eclipses in '' On Sizes and Distances'' to compute the relative diameters of the Sun, Earth, and Moon.

Theological doubt informed by the flat Earth

The flat-Earth model is an archaic and scientifically disproven conception of Earth's shape as a plane or disk. Many ancient cultures subscribed to a flat-Earth cosmography, including Greece until the classical period (5th century BC), t ...

model implied in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

'' Lactantius,

/ref> While this was an ingenious new method, Al-Biruni was not aware of

According to John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson,

'' Lactantius,

John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of ...

and Athanasius of Alexandria, but this remained an eccentric current. Learned Christian authors such as Basil of Caesarea, Ambrose and Augustine of Hippo were clearly aware of the sphericity of Earth. "Flat Earthism" lingered longest in Syriac Christianity, which tradition laid greater importance on a literalist interpretation of the Old Testament. Authors from that tradition, such as Cosmas Indicopleustes

Cosmas Indicopleustes ( grc-x-koine, Κοσμᾶς Ἰνδικοπλεύστης, lit=Cosmas who sailed to India; also known as Cosmas the Monk) was a Greek merchant and later hermit from Alexandria of Egypt. He was a 6th-century traveller who ma ...

, presented Earth as flat as late as in the 6th century. This last remnant of the ancient model of the cosmos disappeared during the 7th century. From the 8th century and the beginning medieval period

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, "no cosmographer worthy of note has called into question the sphericity of the Earth".

Such widely read encyclopedists as Macrobius and Martianus Capella

Martianus Minneus Felix Capella (fl. c. 410–420) was a jurist, polymath and Latin prose writer of late antiquity, one of the earliest developers of the system of the seven liberal arts that structured early medieval education. He was a nati ...

(both 5th century AD) discussed the circumference of the sphere of the Earth, its central position in the universe, the difference of the season

A season is a division of the year based on changes in weather, ecology, and the number of daylight hours in a given region. On Earth, seasons are the result of the axial parallelism of Earth's tilted orbit around the Sun. In temperate and ...

s in northern and southern hemispheres, and many other geographical details., translated in In his commentary on Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

's ''Dream of Scipio

A dream is a succession of images, ideas, emotions, and sensations that usually occur involuntarily in the mind during certain stages of sleep. Humans spend about two hours dreaming per night, and each dream lasts around 5 to 20 minutes, althou ...

'', Macrobius described the Earth as a globe of insignificant size in comparison to the remainder of the cosmos.

Islamic world

Islamic astronomy

Islamic astronomy comprises the astronomical developments made in the Islamic world, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age (9th–13th centuries), and mostly written in the Arabic language. These developments mostly took place in the Middle ...

was developed on the basis of a spherical Earth inherited from Hellenistic astronomy

Greek astronomy is astronomy written in the Greek language in classical antiquity. Greek astronomy is understood to include the Ancient Greek, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman, and Late Antiquity eras. It is not limited geographically to Greece or to eth ...

. The Islamic theoretical framework largely relied on the fundamental contributions of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

(''De caelo

''On the Heavens'' (Greek: ''Περὶ οὐρανοῦ''; Latin: ''De Caelo'' or ''De Caelo et Mundo'') is Aristotle's chief cosmological treatise: written in 350 BC, it contains his astronomical theory and his ideas on the concrete workings ...

'') and Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

('' Almagest''), both of whom worked from the premise that Earth was spherical and at the centre of the universe ( geocentric model).

Early Islamic scholars recognized Earth's sphericity, leading Muslim mathematicians to develop spherical trigonometry

Spherical trigonometry is the branch of spherical geometry that deals with the metrical relationships between the sides and angles of spherical triangles, traditionally expressed using trigonometric functions. On the sphere, geodesics are grea ...

in order to further mensuration and to calculate the distance and direction from any given point on Earth to Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

. This determined the ''Qibla

The qibla ( ar, قِبْلَة, links=no, lit=direction, translit=qiblah) is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the ...

'', or Muslim direction of prayer.

Al-Ma'mun

Around 830 CE,Caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

al-Ma'mun commissioned a group of Muslim astronomers and geographers

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" a ...

to measure the distance from Tadmur (Palmyra

Palmyra (; Palmyrene: () ''Tadmor''; ar, تَدْمُر ''Tadmur'') is an ancient city in present-day Homs Governorate, Syria. Archaeological finds date back to the Neolithic period, and documents first mention the city in the early secon ...

) to Raqqa

Raqqa ( ar, ٱلرَّقَّة, ar-Raqqah, also and ) (Kurdish: Reqa/ ڕەقە) is a city in Syria on the northeast bank of the Euphrates River, about east of Aleppo. It is located east of the Tabqa Dam, Syria's largest dam. The Hellenistic, ...

in modern Syria. To determine the length of one degree of latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

, by using a rope to measure the distance travelled due north or south ( meridian arc) on flat desert land until they reached a place where the altitude of the North Pole had changed by one degree.

Al-Ma'mun's arc measurement

The Arab, Arabic, or Arabian mile ( ar, الميل, ''al-mīl'') was a historical Arabic unit of length. Its precise length is disputed, lying between 1.8 and 2.0 km. It was used by medieval Arab geographers and astronomers. The predecessor o ...

result is described in different sources as 66 2/3 miles, 56.5 miles, and 56 miles. The figure Alfraganus used based on these measurements was 56 2/3 miles, giving an Earth circumference of . 66 miles results in a calculated planetary circumference of .

Another estimate given by his astronomers was 56 Arabic miles (111.8 km) per degree, which corresponds to a circumference of 40,248 km, very close to the currently modern values of 111.3 km per degree and 40,068 km circumference, respectively.

Ibn Hazm

Andalusianpolymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

Ibn Hazm

Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad ibn Saʿīd ibn Ḥazm ( ar, أبو محمد علي بن احمد بن سعيد بن حزم; also sometimes known as al-Andalusī aẓ-Ẓāhirī; 7 November 994 – 15 August 1064Ibn Hazm. ' (Preface). Tr ...

gave a concise proof of Earth's sphericity: at any given time, there is a point on the Earth where the Sun is directly overhead (which moves throughout the day and throughout the year).

Al-Farghānī

Al-Farghānī (Latinized as Alfraganus) was a Persian astronomer of the 9th century involved in measuring the diameter of Earth, and commissioned by Al-Ma'mun. His estimate given above for a degree (56 Arabic miles) was much more accurate than the 60 Roman miles (89.7 km) given by Ptolemy.Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

uncritically used Alfraganus's figure as if it were in Roman miles instead of in Arabic miles, in order to prove a smaller size of Earth than that propounded by Ptolemy.

Biruni

Abu Rayhan Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

(973–1048) used a new method to accurately compute Earth's circumference

In geometry, the circumference (from Latin ''circumferens'', meaning "carrying around") is the perimeter of a circle or ellipse. That is, the circumference would be the arc length of the circle, as if it were opened up and straightened out t ...

, by which he arrived at a value that was close to modern values for Earth's circumference. His estimate of for Earth's radius

Earth radius (denoted as ''R''🜨 or R_E) is the distance from the center of Earth to a point on or near its surface. Approximating the figure of Earth by an Earth spheroid, the radius ranges from a maximum of nearly (equatorial radius, deno ...

was only less than the modern mean value of . In contrast to his predecessors, who measured Earth's circumference by sighting the Sun simultaneously from two different locations, Biruni developed a new method of using trigonometric

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics that studies relationships between side lengths and angles of triangles. The field emerged in the Hellenistic world during the 3rd century BC from applications of geometry to astronomical studies. ...

calculations based on the angle between a plain

In geography, a plain is a flat expanse of land that generally does not change much in elevation, and is primarily treeless. Plains occur as lowlands along valleys or at the base of mountains, as coastal plains, and as plateaus or uplands ...

and mountain

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually highe ...

top. This yielded more accurate measurements of Earth's circumference and made it possible for a single person to measure it from a single location.

Biruni's method was intended to avoid "walking across hot, dusty deserts", and the idea came to him when he was on top of a tall mountain in India (present day Pind Dadan Khan

Pind Dadan Khan (P.D. Khan), a city in Jhelum District, Punjab, Pakistan, is the capital of Pind Dadan Khan Tehsil, which is an administrative subdivision of the district.

Location

It is located at 32°35'16N 73°2'44E on the bank of River Jhel ...

, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

).

From the top of the mountain, he sighted the dip angle which, along with the mountain's height (which he calculated beforehand), he applied to the law of sines

In trigonometry, the law of sines, sine law, sine formula, or sine rule is an equation relating the lengths of the sides of any triangle to the sines of its angles. According to the law,

\frac \,=\, \frac \,=\, \frac \,=\, 2R,

where , and ar ...

formula to calculate the curvature of the Earth.</ref> While this was an ingenious new method, Al-Biruni was not aware of

atmospheric refraction

Atmospheric refraction is the deviation of light or other electromagnetic wave from a straight line as it passes through the atmosphere due to the variation in air density as a function of height. This refraction is due to the velocity of ligh ...

. To get the true dip angle the measured dip angle needs to be corrected by approximately 1/6, meaning that even with perfect measurement his estimate could only have been accurate to within about 20%.

Biruni also made use of algebra

Algebra () is one of the broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathematics.

Elementary ...

to formulate trigonometric equations and used the astrolabe to measure angles.Jim Al-Khalili

Jameel Sadik "Jim" Al-Khalili ( ar, جميل صادق الخليلي; born 20 September 1962) is an Iraqi-British theoretical physicist, author and broadcaster. He is professor of theoretical physics and chair in the public engagement in scien ...

, , BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Jamal-al-Din

A terrestrial globe (Kura-i-ard) was among the presents sent by the Persian Muslim astronomer Jamal-al-Din to Kublai Khan'sChinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

court in 1267. It was made of wood on which "seven parts of water are represented in green, three parts of land in white, with rivers, lakes et cetera. Ho Peng Yoke remarks that "it did not seem to have any general appeal to the Chinese in those days".

Applications

Muslim scholars who held to the spherical Earth theory used it for a quintessentially Islamic purpose: to calculate the distance and direction from any given point on Earth toMecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

. Muslim mathematicians developed spherical trigonometry

Spherical trigonometry is the branch of spherical geometry that deals with the metrical relationships between the sides and angles of spherical triangles, traditionally expressed using trigonometric functions. On the sphere, geodesics are grea ...

; in the 11th century, al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

used it to find the direction of Mecca from many cities and published it in ''The Determination of the Co-ordinates of Cities''. This determined the Qibla

The qibla ( ar, قِبْلَة, links=no, lit=direction, translit=qiblah) is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the ...

, or Muslim direction of prayer.

Magnetic declination

Muslim astronomers and geographers were aware ofmagnetic declination

Magnetic declination, or magnetic variation, is the angle on the horizontal plane between magnetic north (the direction the north end of a magnetized compass needle points, corresponding to the direction of the Earth's magnetic field lines) an ...

by the 15th century, when the Egyptian astronomer 'Abd al-'Aziz al-Wafa'i (d. 1469/1471) measured it as 7 degrees from Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the Capital city, capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, List of ...

.

Medieval Europe

Greek influence

In medieval Europe, knowledge of the sphericity of Earth survived into the medieval corpus of knowledge by direct transmission of the texts of Greek antiquity (Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

), and via authors such as Isidore of Seville and Beda Venerabilis. It became increasingly traceable with the rise of scholasticism and medieval learning.Krüger, Reinhard"Ein Versuch über die Archäologie der Globalisierung. Die Kugelgestalt der Erde und die globale Konzeption des Erdraums im Mittelalter"

''Wechselwirkungen'', Jahrbuch aus Lehre und Forschung der Universität Stuttgart, University of Stuttgart, 2007, pp. 28–52 (35–36) Revising the figures attributed to Posidonius, another Greek philosopher determined as the Earth's circumference. This last figure was promulgated by

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

through his world maps. The maps of Ptolemy strongly influenced the cartographers of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. It is probable that Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

, using such maps, was led to believe that Asia was only west of Europe.

Ptolemy's view was not universal, however, and chapter 20 of ''Mandeville's Travels'' (c. 1357) supports Eratosthenes' calculation.

Spread of this knowledge beyond the immediate sphere of Greco-Roman scholarship was necessarily gradual, associated with the pace of Christianisation

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

of Europe. For example, the first evidence of knowledge of the spherical shape of Earth in Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

is a 12th-century Old Icelandic translation of '' Elucidarius''. A list of more than a hundred Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and vernacular writers from Late Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

and the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

who were aware that Earth was spherical has been compiled by Reinhard Krüger, professor for Romance literature at the University of Stuttgart.

It was not until the 16th century that his concept of the Earth's size was revised. During that period the Flemish cartographer, Mercator __NOTOC__

Mercator (Latin for "merchant") may refer to:

People

* Marius Mercator (c. 390–451), a Catholic ecclesiastical writer

* Arnold Mercator, a 16th-century cartographer

* Gerardus Mercator, a 16th-century cartographer

** Mercator 1569 ...

, made successive reductions in the size of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

and all of Europe which had the effect of increasing the size of the earth.

Early Medieval Europe

Isidore of Seville

Bishop Isidore of Seville (560–636) taught in his widely read encyclopedia, ''The Etymologies'', that Earth was "round". The bishop's confusing exposition and choice of imprecise Latin terms have divided scholarly opinion on whether he meant a sphere or a disk or even whether he meant anything specific. Notable recent scholars claim that he taught a spherical Earth. Isidore did not admit the possibility of people dwelling at the antipodes, considering them as legendary and noting that there was no evidence for their existence.Bede the Venerable

The monk Bede (c. 672–735) wrote in his influential treatise on computus, ''The Reckoning of Time'', that Earth was round. He explained the unequal length of daylight from "the roundness of the Earth, for not without reason is it called 'the orb of the world' on the pages of Holy Scripture and of ordinary literature. It is, in fact, set like a sphere in the middle of the whole universe." (De temporum ratione, 32). The large number of surviving manuscripts of ''The Reckoning of Time'', copied to meet the Carolingian requirement that all priests should study the computus, indicates that many, if not most, priests were exposed to the idea of the sphericity of Earth.Ælfric of Eynsham

Ælfric of Eynsham ( ang, Ælfrīc; la, Alfricus, Elphricus; ) was an English abbot and a student of Æthelwold of Winchester, and a consummate, prolific writer in Old English of hagiography, homilies, biblical commentaries, and other genres ...

paraphrased Bede into Old English, saying, "Now the Earth's roundness and the Sun's orbit constitute the obstacle to the day's being equally long in every land."

Bede was lucid about Earth's sphericity, writing "We call the earth a globe, not as if the shape of a sphere were expressed in the diversity of plains and mountains, but because, if all things are included in the outline, the earth's circumference will represent the figure of a perfect globe... For truly it is an orb placed in the centre of the universe; in its width it is like a circle, and not circular like a shield but rather like a ball, and it extends from its centre with perfect roundness on all sides."Russell, Jeffrey B. 1991. ''Inventing the Flat Earth''. New York: Praeger Publishers. p. 87.

Anania Shirakatsi

The 7th-centuryArmenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ' ...

n scholar Anania Shirakatsi

Anania Shirakatsi ( hy, Անանիա Շիրակացի, ''Anania Širakac’i'', anglicized: Ananias of Shirak) was a 7th-century Armenian polymath and natural philosopher, author of extant works covering mathematics, astronomy, geography, chronol ...

described the world as "being like an egg with a spherical yolk (the globe) surrounded by a layer of white (the atmosphere) and covered with a hard shell (the sky)".

High and late medieval Europe

During the

During the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD 150 ...

, the astronomical knowledge in Christian Europe was extended beyond what was transmitted directly from ancient authors by transmission of learning from Medieval Islamic astronomy. An early student of such learning was Gerbert d'Aurillac, the later Pope Sylvester II

Pope Sylvester II ( – 12 May 1003), originally known as Gerbert of Aurillac, was a French-born scholar and teacher who served as the bishop of Rome and ruled the Papal States from 999 to his death. He endorsed and promoted study of Arab and Gre ...

.

Saint Hildegard (Hildegard von Bingen

Hildegard of Bingen (german: Hildegard von Bingen; la, Hildegardis Bingensis; 17 September 1179), also known as Saint Hildegard and the Sibyl of the Rhine, was a German Benedictine abbess and polymath active as a writer, composer, philosopher ...

, 1098–1179), depicted the spherical Earth several times in her work ''Liber Divinorum Operum''.

Johannes de Sacrobosco

Johannes de Sacrobosco, also written Ioannes de Sacro Bosco, later called John of Holywood or John of Holybush ( 1195 – 1256), was a scholar, monk, and astronomer who taught at the University of Paris.

He wrote a short introduction to the Hi ...

(c. 1195c. 1256 AD) wrote a famous work on Astronomy called ''Tractatus de Sphaera

''De sphaera mundi'' (Latin title meaning ''On the Sphere of the World'', sometimes rendered ''The Sphere of the Cosmos''; the Latin title is also given as ''Tractatus de sphaera'', ''Textus de sphaera'', or simply ''De sphaera'') is a medieval ...

'', based on Ptolemy, which primarily considers the sphere of the sky. However, it contains clear proofs of Earth's sphericity in the first chapter.

Many scholastic commentators on Aristotle's ''On the Heavens

''On the Heavens'' (Greek: ''Περὶ οὐρανοῦ''; Latin: ''De Caelo'' or ''De Caelo et Mundo'') is Aristotle's chief cosmological treatise: written in 350 BC, it contains his astronomical theory and his ideas on the concrete workings o ...

'' and Sacrobosco's ''Treatise on the Sphere'' unanimously agreed that Earth is spherical or round. Grant observes that no author who had studied at a medieval university

A medieval university was a corporation organized during the Middle Ages for the purposes of higher education. The first Western European institutions generally considered to be universities were established in present-day Italy (including the ...

thought that Earth was flat.

The ''Elucidarium'' of Honorius Augustodunensis

Honorius Augustodunensis (c. 1080 – c. 1140), commonly known as Honorius of Autun, was a very popular 12th-century Christian theologian who wrote prolifically on many subjects. He wrote in a non-scholastic manner, with a lively style, and his wor ...

(c. 1120), an important manual for the instruction of lesser clergy, which was translated into Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English ...

, Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intellig ...

, Middle High German

Middle High German (MHG; german: Mittelhochdeutsch (Mhd.)) is the term for the form of German spoken in the High Middle Ages. It is conventionally dated between 1050 and 1350, developing from Old High German and into Early New High German. Hig ...

, Old Russian, Middle Dutch

Middle Dutch is a collective name for a number of closely related West Germanic dialects whose ancestor was Old Dutch. It was spoken and written between 1150 and 1500. Until the advent of Modern Dutch after 1500 or c. 1550, there was no overarc ...

, Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlemen ...

, Icelandic, Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

, and several Italian dialects, explicitly refers to a spherical Earth. Likewise, the fact that Bertold von Regensburg

Bertold of Regensburg (c. 1220 – 13 December 1272), also known as Berthold of RatisbonCoulton, G. G. (1923) ''Life in the Middle Ages''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press was a German preacher during the high Middle Ages.

Life

He was a ...

(mid-13th century) used the spherical Earth as an illustration in a sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. ...

shows that he could assume this knowledge among his congregation. The sermon was preached in the vernacular German, and thus was not intended for a learned audience.

Dante's ''Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' ( it, Divina Commedia ) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun 1308 and completed in around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature ...

'', written in Italian in the early 14th century, portrays Earth as a sphere, discussing implications such as the different stars visible in the southern hemisphere, the altered position of the Sun, and the various time zone