History Of Democratic Socialism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Democratic socialism represents the modernist development of

The

The  Saint-Simon was fascinated by the enormous potential of science and technology and advocated a socialist society that would eliminate the disorderly aspects of

Saint-Simon was fascinated by the enormous potential of science and technology and advocated a socialist society that would eliminate the disorderly aspects of

In the United Kingdom, the democratic socialist tradition was represented by

In the United Kingdom, the democratic socialist tradition was represented by

In Germany, democratic socialism became a prominent movement at the end of the 19th century, when the Eisenach's

In Germany, democratic socialism became a prominent movement at the end of the 19th century, when the Eisenach's  In his introduction to the 1895 edition of Karl Marx's '' The Class Struggles in France'', Engels attempted to resolve the division between gradualist

In his introduction to the 1895 edition of Karl Marx's '' The Class Struggles in France'', Engels attempted to resolve the division between gradualist

The socialist industrial unionism of

The socialist industrial unionism of

In February 1917, revolution broke out in Russia in which workers, soldiers and peasants established

In February 1917, revolution broke out in Russia in which workers, soldiers and peasants established  At a conference held on 27 February 1921 in Vienna, parties which did not want to be a part of the

At a conference held on 27 February 1921 in Vienna, parties which did not want to be a part of the

After World War II, democratic socialist, labourist and social-democratic governments introduced

After World War II, democratic socialist, labourist and social-democratic governments introduced  During most of the post-war era, democratic socialist, labourist and social-democratic parties dominated the political scene and laid the ground to universalistic welfare states in the Nordic countries. For much of the mid- and late 20th century, Sweden was governed by the Swedish Social Democratic Party largely in cooperation with

During most of the post-war era, democratic socialist, labourist and social-democratic parties dominated the political scene and laid the ground to universalistic welfare states in the Nordic countries. For much of the mid- and late 20th century, Sweden was governed by the Swedish Social Democratic Party largely in cooperation with

The

The  Within the Communist Party of Great Britain, dissent that began with the repudiation of Stalin by

Within the Communist Party of Great Britain, dissent that began with the repudiation of Stalin by  In the post-war years, socialism became increasingly influential throughout the so-called

In the post-war years, socialism became increasingly influential throughout the so-called

In the United States, the New Left was associated with the anti-war and hippie movements as well as the black liberation movements such as the Black Panther Party. While initially formed in opposition to the so-called Old Left of the Democratic Party, groups composing the New Left gradually became central players in the Democratic coalition, culminating in the nomination of the outspoken anti-Vietnam War George McGovern at the Democratic Party primaries for the 1972 United States presidential election.

The protest wave of 1968 represented a worldwide escalation of social conflicts, predominantly characterised by popular rebellions against military dictatorships, capitalists and bureaucratic elites, who responded with an escalation of political repression and

In the United States, the New Left was associated with the anti-war and hippie movements as well as the black liberation movements such as the Black Panther Party. While initially formed in opposition to the so-called Old Left of the Democratic Party, groups composing the New Left gradually became central players in the Democratic coalition, culminating in the nomination of the outspoken anti-Vietnam War George McGovern at the Democratic Party primaries for the 1972 United States presidential election.

The protest wave of 1968 represented a worldwide escalation of social conflicts, predominantly characterised by popular rebellions against military dictatorships, capitalists and bureaucratic elites, who responded with an escalation of political repression and

In Latin America,

In Latin America,  During the 1980s, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev intended to move the Soviet Union towards democratic socialism in the form of Nordic-style social democracy, calling it a "socialist beacon for all mankind." Prior to its dissolution in 1991, the Soviet Union had the second largest economy in the world after the United States. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the economic integration of the

During the 1980s, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev intended to move the Soviet Union towards democratic socialism in the form of Nordic-style social democracy, calling it a "socialist beacon for all mankind." Prior to its dissolution in 1991, the Soviet Union had the second largest economy in the world after the United States. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the economic integration of the

Many social-democratic parties, particularly after the Cold War, adopted neoliberal economic policies, including austerity, deregulation, financialisation,

Many social-democratic parties, particularly after the Cold War, adopted neoliberal economic policies, including austerity, deregulation, financialisation,  As a result of the party's shift, Labour Party leader

As a result of the party's shift, Labour Party leader  In 1989, the Socialist International adopted a new Declaration of Principles at its 18th congress in Stockholm, Sweden, stating: "Democratic socialism is an international movement for freedom, social justice, and solidarity. Its goal is to achieve a peaceful world where these basic values can be enhanced and where each individual can live a meaningful life with the full development of his or her personality and talents, and with the guarantee of human and civil rights in a democratic framework of society." Within the Labour Party, the ''democratic socialist'' label was used historically by those who identified with the tradition represented by the

In 1989, the Socialist International adopted a new Declaration of Principles at its 18th congress in Stockholm, Sweden, stating: "Democratic socialism is an international movement for freedom, social justice, and solidarity. Its goal is to achieve a peaceful world where these basic values can be enhanced and where each individual can live a meaningful life with the full development of his or her personality and talents, and with the guarantee of human and civil rights in a democratic framework of society." Within the Labour Party, the ''democratic socialist'' label was used historically by those who identified with the tradition represented by the

In the United States, Bernie Sanders, who was the 37th Mayor of Burlington, became the first self-described democratic socialist to be elected to the Senate from Vermont in 2006. In 2016, Sanders made a bid for the Democratic Party presidential candidate, thereby gaining considerable popular support, particularly among the younger generation and the working class. Although the nomination ultimately went to

In the United States, Bernie Sanders, who was the 37th Mayor of Burlington, became the first self-described democratic socialist to be elected to the Senate from Vermont in 2006. In 2016, Sanders made a bid for the Democratic Party presidential candidate, thereby gaining considerable popular support, particularly among the younger generation and the working class. Although the nomination ultimately went to

According to the ''

According to the ''

In the United Kingdom, the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT) put forward a slate of candidates in the 2009 European Parliament election in the United Kingdom, 2009 European Parliament election under the banner of No to EU – Yes to Democracy, a broad

In the United Kingdom, the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT) put forward a slate of candidates in the 2009 European Parliament election in the United Kingdom, 2009 European Parliament election under the banner of No to EU – Yes to Democracy, a broad

socialism

Socialism is a left-wing Economic ideology, economic philosophy and Political movement, movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to Private prop ...

and its outspoken support for democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

. The origins of democratic socialism can be traced back to 19th-century utopian socialist

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often de ...

thinkers and the Chartist movement in Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

, which somewhat differed in their goals but shared a common demand of democratic decision making and public ownership

State ownership, also called government ownership and public ownership, is the ownership of an industry, asset, or enterprise by the state or a public body representing a community, as opposed to an individual or private party. Public ownershi ...

of the means of production

The means of production is a term which describes land, labor and capital that can be used to produce products (such as goods or services); however, the term can also refer to anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as an ...

, and viewed these as fundamental characteristics of the society they advocated for. Democratic socialism was also heavily influenced by the gradualist

Gradualism, from the Latin ''gradus'' ("step"), is a hypothesis, a theory or a tenet assuming that change comes about gradually or that variation is gradual in nature and happens over time as opposed to in large steps. Uniformitarianism, incrementa ...

form of socialism promoted by the British Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. T ...

and Eduard Bernstein's evolutionary socialism.

In the 19th century, the ruling class

In sociology, the ruling class of a society is the social class who set and decide the political and economic agenda of society. In Marxist philosophy, the ruling class are the capitalist social class who own the means of production and by exte ...

es were afraid of socialism because it challenged their rule. Socialism has faced opposition since then, and the opposition to it has often been organized and violent. In countries such as Germany and Italy, democratic socialist parties were banned, like with Otto von Bismarck's Anti-Socialist Laws

The Anti-Socialist Laws or Socialist Laws (german: Sozialistengesetze; officially , approximately "Law against the public danger of Social Democratic endeavours") were a series of acts of the parliament of the German Empire, the first of which was ...

. With the expansion of liberal democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into ...

and universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stan ...

during the 20th century, democratic socialism became a mainstream movement which expanded across the world, as centre-left

Centre-left politics lean to the left on the left–right political spectrum but are closer to the centre than other left-wing politics. Those on the centre-left believe in working within the established systems to improve social justice. The ...

and left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

parties came to govern, became the main opposition party

Parliamentary opposition is a form of political opposition to a designated government, particularly in a Westminster-based parliamentary system. This article uses the term ''government'' as it is used in Parliamentary systems, i.e. meaning ''t ...

, or simply a commonality of the democratic process in most of the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

; one major exception was the United States. Democratic socialist parties greatly contributed to existing liberal democracy

Liberal democracy is the combination of a liberal political ideology that operates under an indirect democratic form of government. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into ...

.

19th century

Background

Socialist models andideas

In common usage and in philosophy, ideas are the results of thought. Also in philosophy, ideas can also be mental representational images of some object. Many philosophers have considered ideas to be a fundamental ontological category of being. ...

espousing common or public ownership

State ownership, also called government ownership and public ownership, is the ownership of an industry, asset, or enterprise by the state or a public body representing a community, as opposed to an individual or private party. Public ownershi ...

have existed since antiquity, but the first self-conscious socialist movements developed in the 1820s and 1830s. Western European social critics, including Robert Owen, Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical ...

, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Socia ...

, Louis Blanc

Louis Jean Joseph Charles Blanc (; ; 29 October 1811 – 6 December 1882) was a French politician and historian. A socialist who favored reforms, he called for the creation of cooperatives in order to guarantee employment for the urban poor. Alt ...

, Charles Hall, and Henri de Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), often referred to as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on p ...

, were the first modern socialists who criticised the excessive poverty and inequality generated by the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

. The term was first used in English in the British ''Cooperative Magazine'' in 1827 and came to be associated with the followers of Owen such as the Rochdale Pioneers

The Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers, founded in 1844, was an early consumers' co-operative, and one of the first to pay a patronage dividend, forming the basis for the modern co-operative movement.

Although other co-operatives preceded it, ...

, who founded the co-operative movement

The history of the cooperative movement concerns the origins and history of cooperatives across the world. Although cooperative arrangements, such as mutual insurance, and principles of cooperation existed long before, the cooperative movement bega ...

. Owen's followers stressed both participatory democracy

Participatory democracy, participant democracy or participative democracy is a form of government in which citizens participate individually and directly in political decisions and policies that affect their lives, rather than through elected repr ...

and economic socialisation in the form of consumer co-operatives, credit unions

A credit union, a type of financial institution similar to a commercial bank, is a member-owned nonprofit financial cooperative. Credit unions generally provide services to members similar to retail banks, including deposit accounts, provision ...

, and mutual aid societies. In the case of the Owenites, they also overlapped with a number of other working-class and labour movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

s such as the Chartists

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, ...

in the United Kingdom.

Fenner Brockway

Archibald Fenner Brockway, Baron Brockway (1 November 1888 – 28 April 1988) was a British socialist politician, humanist campaigner and anti-war activist.

Early life and career

Brockway was born to W. G. Brockway and Frances Elizabeth Abbey in ...

identified three early democratic socialist groups during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

in his book ''Britain's First Socialists'', namely the Levellers

The Levellers were a political movement active during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms who were committed to popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law and religious tolerance. The hallmark of Leveller thought was its populis ...

, who were pioneers of political democracy and the sovereignty of the people; the Agitators

The Agitators were a political movement as well as elected representatives of soldiers, including members of the New Model Army under Lord General Fairfax, during the English Civil War. They were also known as ''adjutators''. Many of the ideas o ...

, who were the pioneers of participatory control by the ranks at their workplace, and the Diggers

The Diggers were a group of religious and political dissidents in England, associated with agrarian socialism. Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard, amongst many others, were known as True Levellers in 1649, in reference to their split from ...

, who were pioneers of communal ownership, cooperation and egalitarianism

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

. The philosophy and tradition of the Diggers and the Levellers was continued in the period described by E. P. Thompson in ''The Making of the English Working Class

''The Making of the English Working Class'' is a work of English social history written by E. P. Thompson, a New Left historian. It was first published in 1963 by Victor Gollancz Ltd, and republished in revised form in 1968 by Pelican, after ...

'' by Jacobin groups like the London Corresponding Society

The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a federation of local reading and debating clubs that in the decade following the French Revolution agitated for the democratic reform of the British Parliament. In contrast to other reform associati ...

and by polemicists such as Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

. Their concern for both democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

and social justice

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, Equal opportunity, opportunities, and Social privilege, privileges within a society. In Western Civilization, Western and Culture of Asia, Asian cultures, the concept of social ...

marked them out as key precursors of democratic socialism. Democratic socialism also has its origins in the Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

and the French Democratic Socialists

Democratic socialism is a left-wing political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self-management within ...

, although Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

disliked the movement because he viewed it as a party dominated by the middle class and associated to them the word ''Sozialdemokrat'', the first recorded use of the term ''social democracy

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

''.

Origins

The

The Chartists

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, ...

gathered significant numbers around the People's Charter of 1838

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, w ...

which demanded the extension of suffrage to all male adults. Leaders in the movement also called for a more equitable distribution of income and better living conditions for the working classes. The very first trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ...

s and consumers' cooperative

A consumers' co-operative is an enterprise owned by consumers and managed democratically and that aims at fulfilling the needs and aspirations of its members. Such co-operatives operate within the market system, independently of the state, as a f ...

societies also emerged in the hinterland of the Chartist movement as a way of bolstering the fight for these demands. The first advocates of socialism favoured social levelling in order to create a meritocratic

Meritocracy (''merit'', from Latin , and ''-cracy'', from Ancient Greek 'strength, power') is the notion of a political system in which economic goods and/or political power are vested in individual people based on talent, effort, and achi ...

or technocratic

Technocracy is a form of government in which the decision-maker or makers are selected based on their expertise in a given area of responsibility, particularly with regard to scientific or technical knowledge. This system explicitly contrasts wi ...

society based on individual talent as opposed to aristocratic privilege. Saint-Simon is regarded as the first individual to coin the term ''socialism''.

Saint-Simon was fascinated by the enormous potential of science and technology and advocated a socialist society that would eliminate the disorderly aspects of

Saint-Simon was fascinated by the enormous potential of science and technology and advocated a socialist society that would eliminate the disorderly aspects of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

and would be based on equal opportunities

Equal opportunity is a state of fairness in which individuals are treated similarly, unhampered by artificial barriers, prejudices, or preferences, except when particular distinctions can be explicitly justified. The intent is that the important ...

. He advocated the creation of a society in which each person was ranked according to his or her capacities and rewarded according to his or her work. The key focus of Saint-Simon's socialism was on administrative efficiency and industrialism and a belief that science was the key to the progress of human civilisation. This was accompanied by a desire to implement a rationally organised economy based on planning and geared towards large-scale scientific progress and material progress, embodying a desire for a more directed or planned economy. The British political philosopher John Stuart Mill also came to advocate a form of economic socialism within a liberal context known as liberal socialism

Liberal socialism is a political philosophy that incorporates liberal principles to socialism. This synthesis sees liberalism as the political theory that takes the inner freedom of the human spirit as a given and adopts liberty as the goal, ...

. In later editions of ''Principles of Political Economy

''Principles of Political Economy'' (1848) by John Stuart Mill was one of the most important economics or political economy textbooks of the mid-nineteenth century. It was revised until its seventh edition in 1871, shortly before Mill's death ...

'' (1848), Mill would argue that "as far as economic theory was concerned, there is nothing in principle in economic theory that precludes an economic order based on socialist policies." Similarly, the American social reformer Henry George

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American political economist and journalist. His writing was immensely popular in 19th-century America and sparked several reform movements of the Progressive Era. He inspired the eco ...

and his geoist

Georgism, also called in modern times Geoism, and known historically as the single tax movement, is an economic ideology holding that, although people should own the value they produce themselves, the economic rent derived from Land (economics), ...

movement influenced the development of democratic socialism, especially in relation to British socialism and Fabianism, along with Mill and the German historical school of economics.

In Britain

In the United Kingdom, the democratic socialist tradition was represented by

In the United Kingdom, the democratic socialist tradition was represented by William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

's Socialist League and in the 1880s by the Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. T ...

and later the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

founded by Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party, and served as its first parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908.

Hardie was born in Newhouse, Lanarkshire. ...

in the 1890s, of which writer George Orwell would later become a prominent member. In the early 1920s, the guild socialism

Guild socialism is a political movement advocating workers' control of industry through the medium of trade-related guilds "in an implied contractual relationship with the public". It originated in the United Kingdom and was at its most influent ...

of G. D. H. Cole

George Douglas Howard Cole (25 September 1889 – 14 January 1959) was an English political theorist, economist, and historian. As a believer in common ownership of the means of production, he theorised guild socialism (production organised ...

attempted to envision a socialist alternative to Soviet-style authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic voti ...

while council communism

Council communism is a current of communist thought that emerged in the 1920s. Inspired by the November Revolution, council communism was opposed to state socialism and advocated workers' councils and council democracy. Strong in Germany ...

articulated democratic socialist positions in several respects, notably through renouncing the vanguard

The vanguard (also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

History

The vanguard derives fr ...

role of the revolutionary party and holding that the system of the Soviet Union was not authentically socialist.

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation which was established with the purpose of advancing the principles of socialism via gradualist

Gradualism, from the Latin ''gradus'' ("step"), is a hypothesis, a theory or a tenet assuming that change comes about gradually or that variation is gradual in nature and happens over time as opposed to in large steps. Uniformitarianism, incrementa ...

and reform

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement ...

ist means. The society functions primarily as a think tank

A think tank, or policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, military, technology, and culture. Most think tanks are non-governmenta ...

and is one of the fifteen socialist societies

A socialist society is a membership organisation that is affiliated with the Labour Party in the UK.

The best-known and oldest socialist society is the Fabian Society, founded in 1884, some years before the creation of the Labour Party itself ( ...

affiliated with the Labour Party. Similar societies exist in Australia (the Australian Fabian Society

The Australian Fabians (also known as the Australian Fabian Society) is an Australian independent left-leaning think tank that was established in 1947. The organisations said aims are to “contribute to progressive political thinking” as w ...

), in Canada (the Douglas-Coldwell Foundation, and the since disbanded League for Social Reconstruction

The League for Social Reconstruction (LSR) was a circle of Canadian socialists officially formed in 1932. The group advocated for social and economic reformation as well as political education. The formation of the LSR was provoked by events such ...

) and in New Zealand. The society laid many of the foundations of the Labour Party and subsequently affected the policies of states emerging from the decolonisation

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence m ...

of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, most notably India and Singapore. Originally, the Fabian Society was committed to the establishment of a socialist economy

Socialist economics comprises the economic theories, practices and norms of hypothetical and existing socialist economic systems. A socialist economic system is characterized by social ownership and operation of the means of production that may ...

, alongside a commitment to British imperialism

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

and colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colony, colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose the ...

as a progressive and modernising force. In 1889 (the centennial of the French Revolution of 1789), the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second International continued th ...

was founded, with 384 delegates from twenty countries representing about 300 labour and socialist organisations. It was termed the Socialist International and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' Anarchists Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

were ejected and not allowed in mainly due to pressure from Marxists. It has been argued that at some point the Second International turned "into a battleground over the issue of libertarian versus authoritarian socialism. Not only did they effectively present themselves as champions of minority rights; they also provoked the German Marxists into demonstrating a dictatorial intolerance which was a factor in preventing the British labour movement from following the Marxist direction indicated by such leaders as H. M. Hyndman."

'' Anarchists Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

In Germany

In Germany, democratic socialism became a prominent movement at the end of the 19th century, when the Eisenach's

In Germany, democratic socialism became a prominent movement at the end of the 19th century, when the Eisenach's Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands, SDAP) was a Marxist socialist political party in the North German Confederation during unification.

Founded in Eisenach in 1869, the SDAP e ...

merged with Lassalle's General German Workers' Association

The General German Workers' Association (german: Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiter-Verein, ADAV) was a German political party founded on 23 May 1863 in Leipzig, Kingdom of Saxony by Ferdinand Lassalle. It was the first organized mass working-class ...

in 1875 to form the Social Democratic Party of Germany. Reformism arose as an alternative to revolution, with leading social democrat Eduard Bernstein proposing the concept of evolutionary socialism. Revolutionary socialists, encompassing multiple social and political movements that may define revolution differently from one another, quickly targeted the nascent ideology of reformism and Rosa Luxemburg condemned Bernstein's '' Evolutionary Socialism'' in her 1900 essay titled '' Social Reform or Revolution?'' The Social Democratic Party of Germany became the largest and most powerful socialist party in Europe despite being an illegal organisation until the anti-socialist laws

The Anti-Socialist Laws or Socialist Laws (german: Sozialistengesetze; officially , approximately "Law against the public danger of Social Democratic endeavours") were a series of acts of the parliament of the German Empire, the first of which was ...

were officially repealed in 1890. In the 1893 German federal election, the party gained about 1,787,000 votes, a quarter of the total votes cast according to Engels. In 1895, the year of his death, Engels highlighted ''The Communist Manifesto

''The Communist Manifesto'', originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (german: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei), is a political pamphlet written by German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Commu ...

s emphasis on winning as a first step the "battle of democracy."

In his introduction to the 1895 edition of Karl Marx's '' The Class Struggles in France'', Engels attempted to resolve the division between gradualist

In his introduction to the 1895 edition of Karl Marx's '' The Class Struggles in France'', Engels attempted to resolve the division between gradualist reformist

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can ...

and revolutionary socialists in the Marxist movement by declaring that he was in favour of short-term tactics of electoral politics that included gradualist and evolutionary socialist policies while maintaining his belief that revolutionary seizure of power by the proletariat should remain a key goal of the socialist movement. In spite of this attempt by Engels to merge gradualism and revolution, his effort only diluted the distinction of gradualism and revolution and had the effect of strengthening the position of the revisionists. Engels' statements in the French newspaper ''Le Figaro'' in which he argued that "revolution" and the "so-called socialist society" were not fixed concepts, but rather constantly changing social phenomena and said that this made "us ocialistsall evolutionists", increased the public perception that Engels was gravitating towards evolutionary socialism. Engels also wrote that it would be "suicidal" to talk about a revolutionary seizure of power at a time when the historical circumstances favoured a parliamentary road to power which he predicted could happen "as early as 1898."

Engels' stance of openly accepting gradualist, evolutionary and parliamentary tactics while claiming that the historical circumstances did not favour revolution caused confusion among political commentators and the public. Bernstein interpreted this as indicating that Engels was moving towards accepting parliamentary reformist and gradualist stances, but he ignored that Engels' stances were tactical as a response to the particular circumstances at that time and that Engels was still committed to revolutionary socialism. Engels was deeply distressed when he discovered that his introduction to a new edition of ''The Class Struggles in France'' had been edited by Bernstein and Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. Kautsky was one of the most authoritative promulgators of orthodox Marxism after the death of Friedrich Engels i ...

in a manner which left the impression that he had become a proponent of a peaceful road to socialism. On 1 April 1895, four months before his death, Engels responded to Kautsky:

Early 20th century

Early democratic success and development

In Argentina, theSocialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of t ...

was established in the 1890s, being led by Juan B. Justo and Nicolás Repetto, among others, becoming the first mass party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or pol ...

in the country and in Latin America. The party affiliated itself with the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second International continued th ...

. Between 1924 and 1940, it was one of the many socialist party members of the Labour and Socialist International (LSI), the forerunner of the present-day Socialist International

The Socialist International (SI) is a political international or worldwide organisation of political parties which seek to establish democratic socialism. It consists mostly of socialist and labour-oriented political parties and organisations ...

. In 1904, Australians elected Chris Watson as the first Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

from the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms t ...

, becoming the first democratic socialist elected into office. The British Labour Party first won seats in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

in 1902. By 1917, the patriotism of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

changed into political radicalism

Radical politics denotes the intent to transform or replace the principles of a society or political system, often through social change, structural change, revolution or radical reform. The process of adopting radical views is termed radica ...

in Australia, most of Europe and the United States. Other socialist parties from around the world who were beginning to gain importance in their national politics in the early 20th century included the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Socialism, socialist and later Social democracy, social-democratic List of political parties in Italy, political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the l ...

, the French Section of the Workers' International, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español ; PSOE ) is a social-democraticThe PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* political party in Spain. The PSOE has been in gove ...

, the Swedish Social Democratic Party, the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, the Socialist Party of America and the Chilean Socialist Workers' Party. The International Socialist Commission

:

The International Socialist Commission, also known as the International Socialist Committee or the Berne International was a coordinating committee of socialists parties that adhered to the idea of the Zimmerwald Conference of 1915.

Early hist ...

(ISC) was formed in February 1919 at a meeting in Bern, Switzerland by parties that wanted to resurrect the Second International.

The socialist industrial unionism of

The socialist industrial unionism of Daniel De Leon

Daniel De Leon (; December 14, 1852 – May 11, 1914), alternatively spelt Daniel de León, was a Curaçaoan-American socialist newspaper editor, politician, Marxist theoretician, and trade union organizer. He is regarded as the forefather o ...

in the United States represented another strain of early democratic socialism in this period. It favoured a form of government based on industrial unions, but it also sought to establish a socialist government after winning at the ballot box. Democratic socialism continued to flourish in the Socialist Party of America, especially under the leadership of Norman Thomas

Norman Mattoon Thomas (November 20, 1884 – December 19, 1968) was an American Presbyterian minister who achieved fame as a socialist, pacifist, and six-time presidential candidate for the Socialist Party of America.

Early years

Thomas was the ...

. The Socialist Party of America was formed in 1901 after a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of America which had split from the main organisation in 1899. The Socialist Party of America was also known at various times in its long history as the Socialist Party of the United States (as early as the 1910s) and Socialist Party USA (as early as 1935, most common in the 1960s), but the official party name remained Socialist Party of America. Eugene V. Debs twice won over 900,000 votes in the 1912 presidential elections and increased his portion of the popular vote to over 1,000,000 in the 1920 presidential election despite being imprisoned for alleged sedition. The Socialist Party of America also elected two Representatives ( Victor L. Berger and Meyer London

Meyer London (December 29, 1871 – June 6, 1926) was an American politician from New York City. He represented the Lower East Side of Manhattan and was one of only two members of the Socialist Party of America elected to the United States Congre ...

), dozens of state legislators, more than hundred mayors and countless minor officials. Furthermore, the city of Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee ...

has been led by a series of democratic socialist mayors in the early 20th century, namely Frank Zeidler

Frank Paul Zeidler (September 20, 1912 – July 7, 2006) was an American socialist politician and mayor of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, serving three terms from April 20, 1948, to April 18, 1960. Zeidler, a member of the Socialist Party of America, i ...

, Emil Seidel

Emil Seidel (December 13, 1864 – June 24, 1947) was a prominent German-American politician. Seidel was the mayor of Milwaukee from 1910 to 1912. The first Socialist mayor of a major city in the United States, Seidel became the Vice Presidential ...

and Daniel Hoan

Daniel Webster Hoan (March 12, 1881 – June 11, 1961) was an American politician who served as the 32nd Mayor of Milwaukee, Wisconsin from 1916 to 1940. A lawyer who had served as Milwaukee City Attorney from 1910 to 1916, Hoan was a promin ...

.

Russian Revolution and aftermath

In February 1917, revolution broke out in Russia in which workers, soldiers and peasants established

In February 1917, revolution broke out in Russia in which workers, soldiers and peasants established soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in ...

, the monarchy was forced into exile fell and a provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or ...

was formed until the election of a constituent assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

. Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early Nove ...

, a Russian lawyer and revolutionary, became a key political figure in the Russian Revolution of 1917. After the February Revolution, Kerensky joined the newly formed Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately ...

, first as Minister of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

, then as Minister of War

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

and after July as the government's second Minister-Chairman. A leader of the moderate socialist Trudovik

The Trudoviks (russian: Трудова́я гру́ппа, translit=Trudovaya gruppa, lit=Labour Group) were a social-democratic political party of Russia in early 20th century.

History

The Trudoviks were a breakaway of the Socialist Revolut ...

faction of the Socialist Revolutionary Party known as the Labour Group, Kerensky was also the vice-chairman of the powerful Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

. After failing to sign a peace treaty with the German Empire to exit from World War I which led to massive popular unrest against the government cabinet, Kerensky's government was overthrown on 7 November by the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

s led by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

in the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

. Soon after the October Revolution, the Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly (Всероссийское Учредительное собрание, Vserossiyskoye Uchreditelnoye sobraniye) was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. It met fo ...

elected Socialist-Revolutionary leader Victor Chernov

Viktor Mikhailovich Chernov (russian: Ви́ктор Миха́йлович Черно́в; December 7, 1873 – April 15, 1952) was a Russian revolutionary and one of the founders of the Russian Socialist-Revolutionary Party. He was the primar ...

as President of a Russian Republic, but it rejected the Bolshevik proposal that endorsed the Soviet decrees on land, peace and workers' control and acknowledged the power of the Soviets of Workers', Soldiers' and Peasants' Deputies.

As a result of the 1917 Russian Constituent Assembly election

Elections to the Russian Constituent Assembly were held on 25 November 1917, although some districts had polling on alternate days, around two months after they were originally meant to occur, having been organized as a result of events in the Feb ...

which saw a landslide victory for the Socialist-Revolutionaries, the Bolsheviks declared on the next day that the assembly was elected based on outdated party lists which did not reflect the Socialist Revolutionary Party split into Left and Right Socialist-Revolutionary factions. The Left Socialist-Revolutionaries

The Party of Left Socialist-Revolutionaries (russian: Партия левых социалистов-революционеров-интернационалистов) was a revolutionary socialist political party formed during the Russian Rev ...

were allied with the Bolsheviks. The All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets promptly dissolved the Russian Constituent Assembly.

Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

or the resurrected Second International formed the International Working Union of Socialist Parties (IWUSP). The ISC and the IWUSP eventually joined to form the LSI in May 1923 at a meeting held Hamburg. Left-wing groups which did not agree to the centralisation and abandonment of the soviets by the Bolshevik Party

" Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first)Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

led left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks

The left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks, known in anarchist literature as the Third Russian Revolution, were a series of rebellions, uprisings, and revolts against the Bolsheviks by oppositional left-wing organizations and groups that st ...

. Such groups included anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

, Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, Mensheviks

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions em ...

and Socialist-Revolutionaries. Amidst this left-wing discontent, the most large-scale events were the workers' Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion ( rus, Кронштадтское восстание, Kronshtadtskoye vosstaniye) was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors and civilians against the Bolshevik government in the Russian SFSR port city of Kronstadt. Loc ...

and the anarchist-led Makhnovshchina

The Makhnovshchina () was an attempt to form a stateless anarchist society in parts of Ukraine during the Russian Revolution of 1917–1923. It existed from 1918 to 1921, during which time free soviets and libertarian communes operated un ...

in Ukraine.

In 1922, the 4th World Congress of the Communist International took up the policy of the united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts and/or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political ...

, urging communists to work with rank and file social democrats while remaining critical of their party leaders, whom they criticised for betraying the working class by supporting the war efforts of their respective capitalist classes. For their part, the social democrats pointed to the dislocation and chaos caused by revolution and later the growing authoritarianism of the communist parties

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

after they achieved power. When the Communist Party of Great Britain applied to affiliate with the Labour Party in 1920, it was turned down. On seeing the Soviet Union's growing coercive power in 1923, a dying Lenin stated that Russia had reverted to a " bourgeois tsarist machine ... barely varnished with socialism." After Lenin's death in January 1924, the communist party, increasingly falling under the control of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

, rejected the theory that socialism could not be built solely in the Soviet Union in favour of the concept of socialism in one country

Socialism in one country was a Soviet state policy to strengthen socialism within the country rather than socialism globally. Given the defeats of the 1917–1923 European communist revolutions, Joseph Stalin and Nikolai Bukharin encouraged th ...

.

In other parts of Europe, many democratic socialist parties were united in the IWUSP in the early 1920s and in the London Bureau

The International Revolutionary Marxist Centre was an international association of left-socialist parties. The member-parties rejected both mainstream social democracy and the Third International.

Organizational history

The International was fo ...

in the 1930s, along with many other socialists of different tendencies and ideologies. These socialist internationals sought to steer a centrist course between the revolutionaries and the social democrats of the Second International and the perceived anti-democratic Communist International. In contrast, the social democrats of the Second International were seen as insufficiently socialist and had been compromised by their support for World War I. The key movements within the IWUSP were the Austromarxists and the British Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

while the main forces in the London Bureau were the Independent Labour Party and the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification.

Mid-20th century

Post-war governments

After World War II, democratic socialist, labourist and social-democratic governments introduced

After World War II, democratic socialist, labourist and social-democratic governments introduced social reform

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary move ...

s and wealth redistribution

Redistribution of income and wealth is the transfer of income and wealth (including physical property) from some individuals to others through a social mechanism such as taxation, welfare, public services, land reform, monetary policies, confis ...

via welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equita ...

social programmes and progressive taxation

A progressive tax is a tax in which the tax rate increases as the taxable amount increases.Sommerfeld, Ray M., Silvia A. Madeo, Kenneth E. Anderson, Betty R. Jackson (1992), ''Concepts of Taxation'', Dryden Press: Fort Worth, TX The term ''progr ...

. Those parties dominated post-war politics in the Nordic countries and countries such as Belgium, Czechoslovakia, France, Italy and the United Kingdom. At one point, France claimed the world's most state-controlled capitalist country, starting a period of unprecedented economic growth known as the Trente Glorieuses

''Les Trente Glorieuses'' (; 'The Glorious Thirty') was a thirty-year period of economic growth in France between 1945 and 1975, following the end of the Second World War. The name was first used by the French demographer Jean Fourastié, who ...

, part of the post-war economic boom set in motion by the Keynesian consensus. The public utilities and industries nationalised by the French government included Air France

Air France (; formally ''Société Air France, S.A.''), stylised as AIRFRANCE, is the flag carrier of France headquartered in Tremblay-en-France. It is a subsidiary of the Air France–KLM Group and a founding member of the SkyTeam global a ...

, the Bank of France, Charbonnages de France

Charbonnages de France was a French enterprise created in 1946, as a result of the nationalization of the private mining companies. It was disbanded in 2007.

References

Mining companies of France

French companies established in 1946

Non- ...

, Électricité de France, Gaz de France

Gaz de France (GDF) was a French company which produced, transported and sold natural gas around the world, especially in France, its main market. The company was also particularly active in Belgium, the United Kingdom, Germany, and other Europea ...

and Régie Nationale des Usines Renault.

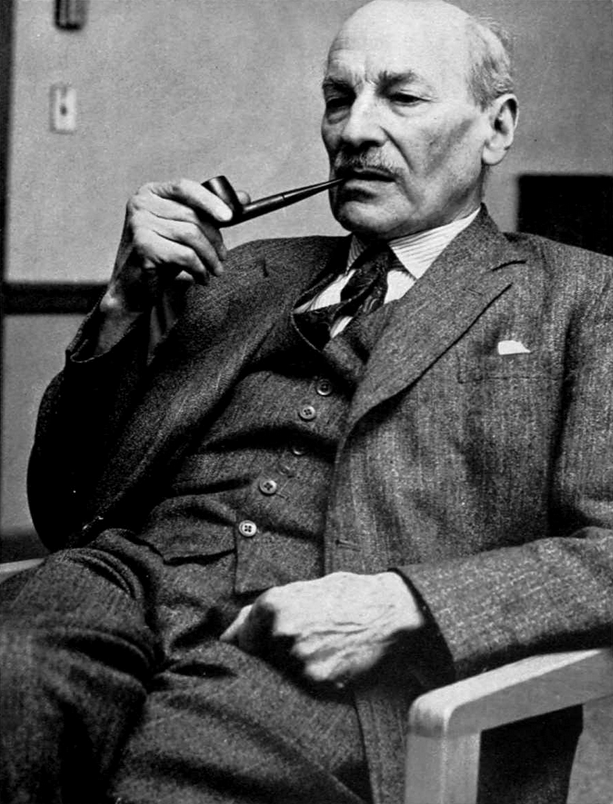

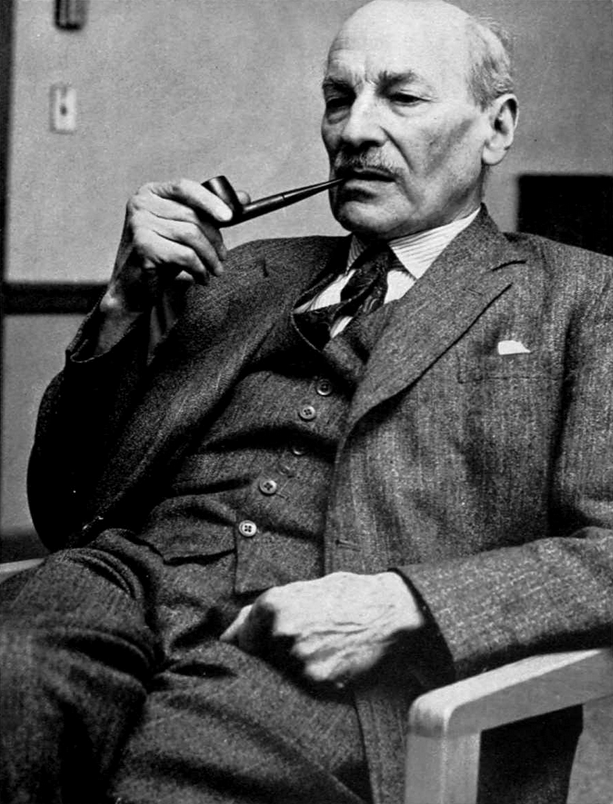

In 1945, the British Labour Party led by Clement Attlee was elected to office based on a radical, democratic socialist programme. The Labour government nationalised major public utilities and industries such as mining, gas, coal, electricity, rail, iron, steel and the Bank of England. British Petroleum was officially nationalised in 1951. In 1956, Anthony Crosland

Charles Anthony Raven Crosland (29 August 191819 February 1977) was a British Labour Party politician and author. A social democrat on the right wing of the Labour Party, he was a prominent socialist intellectual. His influential book '' The ...

stated that at least 25% of British industry was nationalised and that public employees, including those in nationalised industries, constituted a similar proportion of the country's total workforce. The 1964–1970 and 1974–1979 Labour governments strengthened the policy of nationalisation. These Labour governments renationalised steel ( British Steel) in 1967 after the Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

had privatised it and nationalised car production (British Leyland

British Leyland was an automotive engineering and manufacturing conglomerate formed in the United Kingdom in 1968 as British Leyland Motor Corporation Ltd (BLMC), following the merger of Leyland Motors and British Motor Holdings. It was partl ...

) in 1976. The 1945–1951 Labour government also established National Health Service

The National Health Service (NHS) is the umbrella term for the publicly funded healthcare systems of the United Kingdom (UK). Since 1948, they have been funded out of general taxation. There are three systems which are referred to using the " ...

which provided taxpayer-funded health care to Every British citizen, free at the point of use. High-quality housing for the working class was provided in council housing estates and university education became available to every citizen via a school grant system. The 1945–1951 Labour government has been described as being transformative democratic socialist.

During most of the post-war era, democratic socialist, labourist and social-democratic parties dominated the political scene and laid the ground to universalistic welfare states in the Nordic countries. For much of the mid- and late 20th century, Sweden was governed by the Swedish Social Democratic Party largely in cooperation with

During most of the post-war era, democratic socialist, labourist and social-democratic parties dominated the political scene and laid the ground to universalistic welfare states in the Nordic countries. For much of the mid- and late 20th century, Sweden was governed by the Swedish Social Democratic Party largely in cooperation with trade unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

and industry. Tage Erlander

Tage Fritjof Erlander (; 13 June 1901 – 21 June 1985) was a Swedish politician who served as Prime Minister of Sweden from 1946 to 1969. He was the leader of the Swedish Social Democratic Party and led the government for an uninterrupted tenu ...

was the leader of the Social Democratic Party and led the government from 1946 until 1969, an uninterrupted tenure of twenty-three years, one of the longest in any democracy. From 1945 until 1962, the Norwegian Labour Party held an absolute majority in the parliament led by Einar Gerhardsen

Einar Henry Gerhardsen (; 10 May 1897 – 19 September 1987) was a Norwegian politician from the Labour Party of Norway. He was the 22nd prime minister of Norway for three periods, 1945–1951, 1955–1963 and 1963–1965. With totally 17 years in ...

, who served Prime Minister for seventeen years. The Danish Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

governed Denmark for most of the 20th century and since the 1920s and through the 1940s and the 1970s a large majority of Prime Ministers were members of the Social Democrats, the largest and most popular political party in Denmark.

This particular adaptation of the mixed economy

A mixed economy is variously defined as an economic system blending elements of a market economy with elements of a planned economy, markets with state interventionism, or private enterprise with public enterprise. Common to all mixed economie ...

, better known as the Nordic model, is characterised by more generous welfare states (relative to other developed countries

A developed country (or industrialized country, high-income country, more economically developed country (MEDC), advanced country) is a sovereign state that has a high quality of life, developed economy and advanced technological infrastruct ...

) which are aimed specifically at enhancing individual autonomy, ensuring the universal provision of basic human rights and stabilising the economy. It is distinguished from other welfare states with similar goals by its emphasis on maximising labour force participation, promoting gender equality, egalitarian and extensive benefit levels, large magnitude of redistribution and expansionary fiscal policy. In the 1950s, popular socialism emerged as a vital current of the left in Nordic countries could be characterised as a democratic socialism in the same vein as it placed itself between communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

and social democracy

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

. In the 1960s, Gerhardsen established a planning agency and tried to establish a planned economy. Prominent Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme identified himself as a democratic socialist.

The Rehn–Meidner model

The Rehn–Meidner model is an economic and wage policy model developed in 1951 by two economists at the research department of the Swedish Trade Union Confederation (LO), Gösta Rehn and Rudolf Meidner. The four main goals to be achieved were:

...

was adopted by the Swedish Social Democratic Party in the late 1940s. This economic model allowed capitalists who owned very productive and efficient firms to retain excess profits at the expense of the firm's workers, exacerbating income inequality and causing workers in these firms to agitate for a better share of the profits in the 1970s. Women working in the state sector also began to assert pressure for better and equal wages. In 1976, economist Rudolf Meidner established a study committee that came up with a proposal called the Meidner Plan which entailed the transferring of the excess profits into investment funds controlled by the workers in said efficient firms, with the goal that firms would create further employment and pay workers higher wages in return rather than unduly increasing the wealth of company owners and managers. Capitalists immediately denounced the proposal as socialism and launched an unprecedented opposition and smear campaign against it, threatening to terminate the class compromise established in the 1938 Saltsjöbaden Agreement

The Saltsjöbad Agreement ( sv, Saltsjöbadsavtalet) is a Swedish labour market treaty signed between the Swedish Trade Union Confederation ( sv, Landsorganisationen, LO) and the Swedish Employers Association ( sv, Svenska arbetsgivareföreningen ...

.

Anti-colonialism and revolutions

The

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 10 November 1956; hu, 1956-os forradalom), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was a countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the Hunga ...

was a spontaneous nationwide revolt by democratic socialists against the Marxist–Leninist government of the People's Republic of Hungary

The Hungarian People's Republic ( hu, Magyar Népköztársaság) was a one-party socialist state from 20 August 1949

to 23 October 1989.

It was governed by the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, which was under the influence of the Soviet U ...

and its policies of repression, lasting from 23 October until 10 November 1956. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

's denunciation of the excesses of Stalin's regime during the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was held during the period 14–25 February 1956. It is known especially for First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev's "Secret Speech", which denounced the personality cult and dictatorship ...

that same year as well as the revolt in Hungary produced ideological fractures and disagreements within the democratic communist and socialist parties of Western Europe. A split ensued within the Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party ( it, Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) was a communist political party in Italy.

The PCI was founded as ''Communist Party of Italy'' on 21 January 1921 in Livorno by seceding from the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) ...

(PCI), with most ordinary members and the PCI leadership, including Giorgio Napolitano and Palmiro Togliatti

Palmiro Michele Nicola Togliatti (; 26 March 1893 – 21 August 1964) was an Italian politician and leader of the Italian Communist Party from 1927 until his death. He was nicknamed ("The Best") by his supporters. In 1930 he became a citizen of ...

, regarding the Hungarian insurgents as counter-revolutionaries as reported in ''l'Unità

''l'Unità'' (, lit. 'the Unity') was an Italian language, Italian newspaper, founded as the official newspaper of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in 1924. It was supportive of that party's successor parties, the Democratic Party of the Left, ...

'', the official PCI newspaper.

Giuseppe Di Vittorio

Giuseppe Di Vittorio ( Cerignola, 11 August 1892 – Lecco, 3 November 1957), also known as Nicoletti, was an Italian trade union leader and Communist politician. He was one of the most influential trade union leaders of the labour movement after ...

, General Secretary of the Italian General Confederation of Labour

The Italian General Confederation of Labour (; CGIL) is a national trade union based in Italy. It was formed by agreement between socialists, communists, and Christian democrats in the "Pact of Rome" of June 1944. In 1950, socialists and Christi ...

, repudiated the leadership position, as did the prominent party members Loris Fortuna, Antonio Giolitti

Antonio Giolitti (12 February 1915 – 8 February 2010) was an Italian politician and cabinet member. He was the grandson of Giovanni Giolitti, the well-known liberal statesman of the pre-fascist period who served as Prime Minister of Italy five ...

and many other influential communist intellectuals who later were expelled or left the party. Pietro Nenni

Pietro Sandro Nenni (; 9 February 1891 – 1 January 1980) was an Italian socialist politician, the national secretary of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) and senator for life since 1970. He was a recipient of the Lenin Peace Prize in 1951. He ...

, the national secretary of the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Socialism, socialist and later Social democracy, social-democratic List of political parties in Italy, political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the l ...

, a close ally of the PCI, opposed the Soviet intervention as well. Napolitano, elected in 2006 as President of the Italian Republic

President most commonly refers to:

* President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

, wrote in his 2005 political autobiography that he regretted his justification of Soviet action in Hungary and that at the time he believed in party unity and the international leadership of Soviet communism.

Within the Communist Party of Great Britain, dissent that began with the repudiation of Stalin by

Within the Communist Party of Great Britain, dissent that began with the repudiation of Stalin by John Saville

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

and E. P. Thompson, influential historians and members of the Communist Party Historians Group

A subdivision of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), the Communist Party Historians Group (CPHG) formed a highly influential cluster of British Marxist historians, who contributed to " history from below" from 1946 to 1956. Famous member ...

, culminated in a loss of thousands of party members as events unfolded in Hungary. Peter Fryer