History of Casablanca on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the city of

The history of the city of

-

/ref> Romans occupied the area in 15 BC and created the important commercial port know later as

The town and the

The town and the

In the 19th century Casablanca became a major supplier of wool to the booming textile industry in

In the 19th century Casablanca became a major supplier of wool to the booming textile industry in

Following the

Following the

Under Lyautey's tenure, Casablanca transformed into Morocco's economic center and Africa's biggest port.

Under Lyautey's tenure, Casablanca transformed into Morocco's economic center and Africa's biggest port.

Le Petit Marocain

''Le Petit Marocain'' was a daily publication founded during the protectorate era in Morocco and the predecessor publication of '' Le Matin''.

History and profile

''Le Petit Marocain'' was founded in 1925 and was based in Casablanca. The pape ...

''">

File:Le Petit Marocain November 8, 1942.jpg, November 8, 1942: ''North Africa Attacked by Anglo-American Forces''

File:Le Petit Marocain November 11, 1942.jpg, November 11, 1942: ''Ceasefire Decided Tonight''

File:Le Petit Marocain November 12, 1942.jpg, November 12, 1942: ''Hostilities Have Ceased Throughout North Africa''

At Safi, the objective being capturing the port facilities to land the Western Task Force's medium tanks, the landings were mostly successful. The landings were begun without covering fire, in the hope that the French would not resist at all. However, once French coastal batteries opened fire, Allied warships returned fire. By the time General Ernest Harmon's 2nd Armored Division arrived, French snipers had pinned the assault troops (most of whom were in combat for the first time) on Safi's beaches. Most of the landings occurred behind schedule. Carrier aircraft destroyed a French truck convoy bringing reinforcements to the beach defenses. Safi surrendered on the afternoon of 8 November. By 10 November, the remaining defenders were pinned down, and the bulk of Harmon's forces raced to join the siege of Casablanca.

At Port-Lyautey, the landing troops were uncertain of their position, and the second wave was delayed. This gave the French defenders time to organize resistance, and the remaining landings were conducted under artillery bombardment. With the assistance of air support from the carriers, the troops pushed ahead, and the objectives were captured.

At

At Safi, the objective being capturing the port facilities to land the Western Task Force's medium tanks, the landings were mostly successful. The landings were begun without covering fire, in the hope that the French would not resist at all. However, once French coastal batteries opened fire, Allied warships returned fire. By the time General Ernest Harmon's 2nd Armored Division arrived, French snipers had pinned the assault troops (most of whom were in combat for the first time) on Safi's beaches. Most of the landings occurred behind schedule. Carrier aircraft destroyed a French truck convoy bringing reinforcements to the beach defenses. Safi surrendered on the afternoon of 8 November. By 10 November, the remaining defenders were pinned down, and the bulk of Harmon's forces raced to join the siege of Casablanca.

At Port-Lyautey, the landing troops were uncertain of their position, and the second wave was delayed. This gave the French defenders time to organize resistance, and the remaining landings were conducted under artillery bombardment. With the assistance of air support from the carriers, the troops pushed ahead, and the objectives were captured.

At

During the 1940s and 1950s, Casablanca was a major center of anti-colonial struggle.

In 1947, when the Sultan went to the

During the 1940s and 1950s, Casablanca was a major center of anti-colonial struggle.

In 1947, when the Sultan went to the

Que s'est-il vraiment passé le 23 mars 1965?

, ''Jeune Afrique'', 21 March 2005

Archived

The protests started as a peaceful march to demand the right to public higher education for Morocco, but were violently dispersed. The following day, students returned to Lycée Mohammed V along with workers, the unemployed, and the poor, this time vandalizing stores, burning buses and cars, throwing stones, and chanting slogans against King

168

��169. The riots were repressed with tanks deployed for two days, and General

A secret

A secret

''Maghreb Arabe Presse'': 500k-year human fossil remains found in Casablanca (05/26/2006)

{{Romano-Berber cities in Roman Africa Mauretania Tingitana

The history of the city of

The history of the city of Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

in Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

has been one of many political and cultural changes. At different times it has been governed by Berber, Roman, Arab, Portuguese, Spanish, French, British, and Moroccan regimes. It has had an important position in the region as a port city, making it valuable to a series of conquerors during its early history.

The original Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

name, ''Anfa

Anfa (Berber language: ''Anfa'' or ''Anaffa'', ⴰⵏⴼⴰ; ar, أنفا; es, Anafe; pt, Anafé) was the ancient toponym for Casablanca during the classical period. The city was founded by Berbers around the 10th century BC, with the Romans un ...

'' (meaning: "hill" in English), was used by the locals until the earthquake of 1755

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, also known as the Great Lisbon earthquake, impacted Portugal, the Iberian Peninsula, and Northwest Africa on the morning of Saturday, 1 November, Feast of All Saints, at around 09:40 local time. In combination with ...

destroyed the city. When Sultan Mohammed ben Abdallah

''Sidi'' Mohammed ben Abdallah ''al-Khatib'' ( ar, سيدي محمد بن عبد الله الخطيب), known as Mohammed III ( ar, محمد الثالث), born in 1710 in Fes and died on 9 April 1790 in Meknes, was the Sultan of Morocco from 175 ...

rebuilt the city's medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

, he gave it the name "''ad-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ''" () a literal translation of ''Casablanca'' into Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

. French forces occupied the city in 1907 and adopted the Spanish name, ''Casablanca''. The name ''Anfa'' now refers to an area within Casablanca, slightly West of the 18th century medina.

Roman Anfa

Leo Africanus

Joannes Leo Africanus (born al-Hasan Muhammad al-Wazzan, ar, الحسن محمد الوزان ; c. 1494 – c. 1554) was an Andalusian diplomat and author who is best known for his 1526 book '' Cosmographia et geographia de Affrica'', later ...

defined Anfa as a city built by the Romans in his famous '' Descrittione dell’Africa'' (Description of Africa), written in the 16th century.

The area which is today Casablanca was founded and settled by the Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

by about the 10th century BC.''Casablanca''-

Jewish Virtual Library

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

It was used as a port by the Phoenicians and later by the Romans.LexicOrient/ref> Romans occupied the area in 15 BC and created the important commercial port know later as

Anfa

Anfa (Berber language: ''Anfa'' or ''Anaffa'', ⴰⵏⴼⴰ; ar, أنفا; es, Anafe; pt, Anafé) was the ancient toponym for Casablanca during the classical period. The city was founded by Berbers around the 10th century BC, with the Romans un ...

, directly connected to the Mogador island in the Iles Purpuraires

Iles Purpuraires are a set of small islands off the western coast of Morocco at the bay located at Essaouira, the largest of which is Mogador Island. These islands were settled in antiquity by the Phoenicians, chiefly to exploit certain marine re ...

of southern Mauritania. From there they obtained a special dye, that colored the purple stripe in Imperial Roman Senatorial togas. The expedition of Juba II

Juba II or Juba of Mauretania (Latin: ''Gaius Iulius Iuba''; grc, Ἰóβας, Ἰóβα or ;Roller, Duane W. (2003) ''The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene'' "Routledge (UK)". pp. 1–3. . c. 48 BC – AD 23) was the son of Juba I and client ...

to discover the Canary islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

and Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

probably departed from Anfa

Anfa (Berber language: ''Anfa'' or ''Anaffa'', ⴰⵏⴼⴰ; ar, أنفا; es, Anafe; pt, Anafé) was the ancient toponym for Casablanca during the classical period. The city was founded by Berbers around the 10th century BC, with the Romans un ...

.

The Roman port, probably called initially ''Anfus'' in Latin language, was part of a Berber client state of Rome until Emperor Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

. When Rome annexed Ptolemy of Mauretania

Ptolemy of Mauretania ( grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ''Ptolemaîos''; la, Gaius Iulius Ptolemaeus; 13 9BC–AD40) was the last Roman client king and ruler of Mauretania for Rome. He was the son of Juba II, the king of Numidia and a member o ...

's kingdom, Anfa was incorporated into the Roman Empire by Caligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germanicu ...

. But this was done only nominally because the Roman ''limes

Limes may refer to:

* the plural form of lime (disambiguation)

* the Latin word for ''limit'' which refers to:

** Limes (Roman Empire)

(Latin, singular; plural: ) is a modern term used primarily for the Germanic border defence or delimiting ...

'' was a few dozen kilometers north of the port (the Roman military fortifications of Mauretania Tingitana

Mauretania Tingitana (Latin for "Tangerine Mauretania") was a Roman province, coinciding roughly with the northern part of present-day Morocco. The territory stretched from the northern peninsula opposite Gibraltar, to Sala Colonia (or Chella ...

were just a few kilometers south of the Roman ''colonia'' named ''Sala Colonia

The Chellah or Shalla ( ber, script=Latn, Sla or ; ar, شالة), is a medieval fortified Muslim necropolis and ancient archeological site in Rabat, Morocco, located on the south (left) side of the Bou Regreg estuary. The earliest evidence of the ...

''). However, Roman Anfa—connected mainly by commerce and by socio-cultural ties to Volubilis

Volubilis (; ar, وليلي, walīlī; ber, ⵡⵍⵉⵍⵉ, wlili) is a partly excavated Berber-Roman city in Morocco situated near the city of Meknes, and may have been the capital of the kingdom of Mauretania, at least from the time of Kin ...

("autonomous" from Rome since 285 AD)—lasted until the 5th century, when Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

conquered Roman northwestern Africa.

A Roman wreck of the 2nd century, from which were salvaged 169 silver coins, shows that the Romans appreciated this useful port for commerce. There is even evidence of oil commerce with Roman Volubilis

Volubilis (; ar, وليلي, walīlī; ber, ⵡⵍⵉⵍⵉ, wlili) is a partly excavated Berber-Roman city in Morocco situated near the city of Meknes, and may have been the capital of the kingdom of Mauretania, at least from the time of Kin ...

and Tingis

Tingis (Latin; grc-gre, Τίγγις ''Tíngis'') or Tingi ( Ancient Berber:), the ancient name of Tangier in Morocco, was an important Carthaginian, Moor, and Roman port on the Atlantic Ocean. It was eventually granted the status of a Roman colo ...

in the 3rd century. Probably there was a small community of Christians (linked to Roman merchants) in the port city until the fifth/sixth century.

Barghawata

A large Berber tribe, theBarghawata

The Barghawatas (also Barghwata or Berghouata) were a Berber tribal confederation on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, belonging to the Masmuda confederacy. After allying with the Sufri Kharijite rebellion in Morocco against the Umayyad Caliphate, ...

, settled in the area between the rivers Bou Regreg

The Bou Regreg ( ar, أبو رقراق) is a river located in western Morocco which discharges to the Atlantic Ocean between the cities of Rabat and Salé. The estuary of this river is termed Wadi Sala.

The river is 240 kilometres long, with a t ...

to the north and Oum er-Rbia to the south. It established itself as an independent Berber kingdom in Tamasna

Tamasna (Berber language, Berber: Tamesna, ⵜⴰⵎⵙⵏⴰ, Arabic: تامسنا) is a historical region between Bou Regreg and Tensift River, Tensift in Morocco. It includes the modern regions of Chaouia (Morocco), Chaouia, Doukkala-Abda, Dou ...

around in 744 AD following the Berber Revolt

The Berber Revolt of 740–743 AD (122–125 AH in the Islamic calendar) took place during the reign of the Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik and marked the first successful secession from the Arab caliphate (ruled from Damascus). Fired up b ...

against the Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik

Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik ( ar, هشام بن عبد الملك, Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Malik; 691 – 6 February 743) was the tenth Umayyad caliph, ruling from 724 until his death in 743.

Early life

Hisham was born in Damascus, the administra ...

. It remained until it was conquered by the Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that ...

in 1068 AD.

The Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the Tawhid, unity of God) was a North African Berbers, Berber M ...

Sultan Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) ( ar, عبد المؤمن بن علي or عبد المومن الــكـومي; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad move ...

drove the Barghawata

The Barghawatas (also Barghwata or Berghouata) were a Berber tribal confederation on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, belonging to the Masmuda confederacy. After allying with the Sufri Kharijite rebellion in Morocco against the Umayyad Caliphate, ...

out of Tamasna

Tamasna (Berber language, Berber: Tamesna, ⵜⴰⵎⵙⵏⴰ, Arabic: تامسنا) is a historical region between Bou Regreg and Tensift River, Tensift in Morocco. It includes the modern regions of Chaouia (Morocco), Chaouia, Doukkala-Abda, Dou ...

in 1149, and replaced them with Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert and A ...

Arab tribes, notably Banu Hilal

The Banu Hilal ( ar, بنو هلال, translit=Banū Hilāl) was a confederation of Arabian tribes from the Hejaz and Najd regions of the Arabian Peninsula that emigrated to North Africa in the 11th century. Masters of the vast plateaux of th ...

and Banu Sulaym

The Banu Sulaym ( ar, بنو سليم) is an Arab tribe that dominated part of the Hejaz in the pre-Islamic era. They maintained close ties with the Quraysh of Mecca and the inhabitants of Medina, and fought in a number of battles against the Is ...

.S. Lévy, ''Pour une histoire linguistique du Maroc'', dans ''Peuplement et arabisation au Maghreb occidental: dialectologie et histoire'', 1998, pp.11-26 ()

Early modern period

During the 14th century, under theZenata

The Zenata (Berber language: Iznaten) are a group of Amazigh (Berber) tribes, historically one of the largest Berber confederations along with the Sanhaja and Masmuda. Their lifestyle was either nomadic or semi-nomadic.

Etymology

''Iznaten (ⵉ ...

Merinid Dynasty

The Marinid Sultanate was a Berber Muslim empire from the mid-13th to the 15th century which controlled present-day Morocco and, intermittently, other parts of North Africa (Algeria and Tunisia) and of the southern Iberian Peninsula (Spain) a ...

, the town rose in importance as a port and in the early 15th century, became independent once again. It emerged as a safe harbor for Barbary pirates

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli, Libya, Tripoli. This area was known i ...

. In 1468, the city was captured and destroyed by the Kingdom of Portugal and the Algarves

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* Kingdom (British TV series), ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 200 ...

under Rei Afonso V

Afonso V () (15 January 1432 – 28 August 1481), known by the sobriquet the African (), was King of Portugal from 1438 until his death in 1481, with a brief interruption in 1477. His sobriquet refers to his military conquests in Northern Africa. ...

''the African''. The Portuguese used the ruins to build a military fortress in 1515. The village that grew up around it was called "''Casa Branca''", meaning "White House" in Portuguese.

After the death of Rei Sebastian

Sebastian may refer to:

People

* Sebastian (name), including a list of persons with the name

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films and television

* ''Sebastian'' (1968 film), British spy film

* ''Sebastian'' (1995 film), Swedish drama film

...

in the massive Portuguese defeat at the hands of the Moroccan Saadi Empire in the Battle of Alcácer Quibir

The Battle of Alcácer Quibir (also known as "Battle of Three Kings" ( ar, معركة الملوك الثلاثة) or "Battle of Wadi al-Makhazin" ( ar, معركة وادي المخازن) in Morocco) was fought in northern Morocco, near the t ...

and the ensuing crisis of succession, Casablanca came under Spanish occupation under the Iberian Union

pt, União Ibérica

, conventional_long_name =Iberian Union

, common_name =

, year_start = 1580

, date_start = 25 August

, life_span = 1580–1640

, event_start = War of the Portuguese Succession

, event_end = Portuguese Restoration War

, ...

, from 1580 to 1640.

They eventually abandoned the area completely in 1755 AD following an earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

which destroyed it.

The town and the

The town and the medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

of Casablanca as it is today was founded in 1770 AD by Sultan Muhammad III ben Abdallah (1756–1790), the grandson of Moulay Ismail

Moulay Ismail Ibn Sharif ( ar, مولاي إسماعيل بن الشريف), born around 1645 in Sijilmassa and died on 22 March 1727 at Meknes, was a Sultan of Morocco from 1672–1727, as the second ruler of the Alaouite dynasty. He was the se ...

. Built with the aid of Spaniards, the town was called ''Casa Blanca'' (white house in Spanish) translated ''Dar el Beida'' in Arabic.

19th century

In the 19th century Casablanca became a major supplier of wool to the booming textile industry in

In the 19th century Casablanca became a major supplier of wool to the booming textile industry in Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and shipping traffic increased (the British, in return, began importing Morocco's now famous national drink, gunpowder tea

Gunpowder tea (; pronounced ) is a form of tea in which each leaf has been rolled into a small round pellet. Its English name comes from its resemblance to grains of gunpowder. This rolling method of shaping tea is most often applied either to d ...

). By the 1860s, there were around 5,000 residents, and the population grew to around 10,000 by the late 1880s.Pennel, CR: ''Morocco from Empire to Independence'', Oneworld, Oxford, 2003, p 121 Casablanca grew due to the ''protégé'' system, through which Moroccans protected by European powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

became independent of the Makhzen

Makhzen (Arabic: , Berber: ''Lmexzen'') is the governing institution in Morocco and in pre-1957 Tunisia, centered on the monarch and consisting of royal notables, top-ranking military personnel, landowners, security service bosses, civil servant ...

. Casablanca was also one of the main Atlantic ports to receive Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

migrants from the Moroccan hinterlands following the mission of Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 – 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, philanthropist and Sheriff of London. Born to an Italian Sephardic Jewish family based in London, afte ...

to Morocco in 1864.

Casablanca remained a modestly sized port, with a population reaching around 12,000 within a few years of the French conquest and arrival of French colonialists in the town, at first administrators within a sovereign sultanate, in 1906. By 1921, this was to rise to 110,000, largely through the development of '' bidonvilles.''"Whereas Casablanca appears somewhat forbidding and hostile from the sea, it could not present a more welcoming picture to those traveling from inland. Its leafy gardens are topped by willowy palm trees, crenelated walls, flat roofs, and whitewashed minarets dazzling in the African sun; all this offers a striking backdrop against the deep blue of the natural haven that cradles svelte yachts and burly black and red steamboats." - F. Weisgerber

French rule

French Invasion

Following the

Following the Treaty of Algeciras

The Algeciras Conference of 1906 took place in Algeciras, Spain, and lasted from 16 January to 7 April. The purpose of the conference was to find a solution to the First Moroccan Crisis of 1905 between France and Germany, which arose as Germany ...

in 1906, which granted the French holding company La Compagnie Marocaine rights to build modern ports in Casablanca and in Asfi, construction at the port of Casablanca

The Port of Casablanca ( , ) refers to the collective facilities and terminals that conduct maritime trade handling functions in Casablanca's harbours and which handle Casablanca's shipping. The port is located near Hassan II Mosque.

The Port ...

began on May 2, 1907. A narrow gauge railway extending from the port to a quarry in Roches Noires for stones to build the breakwater, passed over the Sidi Belyout

Sidi Belyout ( ar, سيدي بليوط) is an arrondissement of Casablanca, in the Anfa district of the Casablanca-Settat region of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb reg ...

necropolis, an area held sacred by the Moroccans. In addition, the French had started to control the customs.

On July 28, a delegation representing the tribes of the Chaouia, led by of the tribe, pressed Abu Bakr Bin Buzaid, ''qaid

Qaid ( ar , قائد ', "commander"; pl. '), also spelled kaid or caïd, is a word meaning "commander" or "leader." It was a title in the Norman kingdom of Sicily, applied to palatine officials and members of the ''curia'', usually to those w ...

'' of Casablanca and representative of Sultan Abdelaziz and the Makhzen

Makhzen (Arabic: , Berber: ''Lmexzen'') is the governing institution in Morocco and in pre-1957 Tunisia, centered on the monarch and consisting of royal notables, top-ranking military personnel, landowners, security service bosses, civil servant ...

in the city, with 3 demands: the removal of the French officers from the customs house, an immediate halt on the construction of the port, and the destruction of the railroad.

The pasha equivocated and postponed his decision to mid-day on July 30, by which time regional tribesmen had populated the city and started an insurrection. A group waited for the train to make its way out to Roches Noires to pick up rocks from the quarry, then piled rocks onto the tracks behind it to isolate it. When the train returned, it was ambushed and the French, Spanish, and Italian workers aboard were killed and the train destroyed.

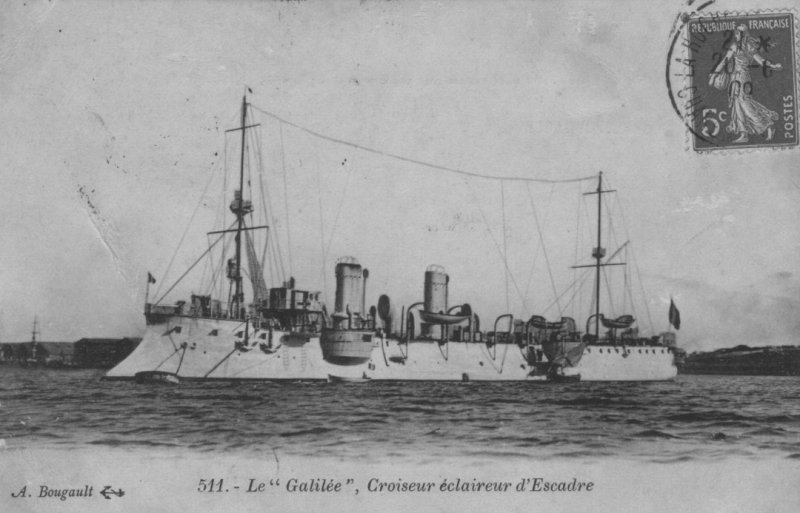

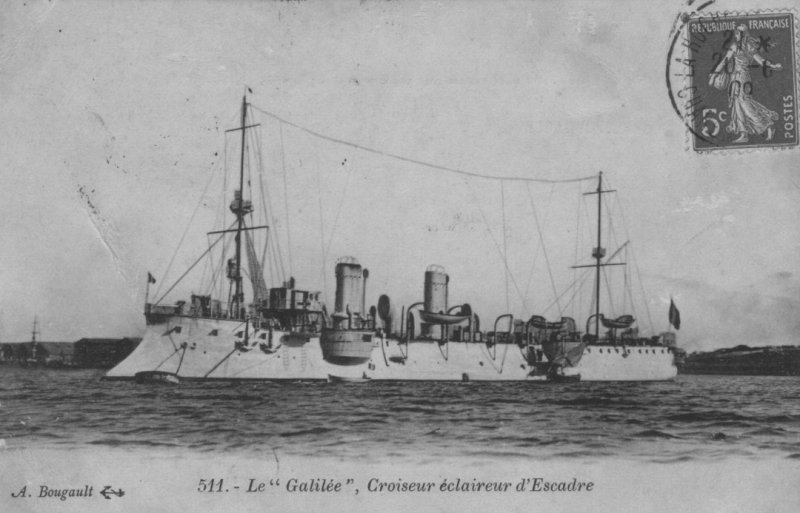

This was the justification the French had been waiting for. From August 5–7, a fleet of French armored cruisers bombarded Casablanca and French troops were landed, marking the beginning of the invasion of Morocco from the west. The French then took control of Casablanca and the Chaouia. This effectively began the process of colonization, although French control of Casablanca was not formalized until the signature of the Treaty of Fez

The Treaty of Fes ( ar, معاهدة فاس, ), officially the Treaty Concluded Between France and Morocco on 30 March 1912, for the Organization of the French Protectorate in the Sherifien Empire (), was a treaty signed by Sultan Abd al-Hafid ...

March 30, 1912.

Commercial explosion

The city overflowed outside of its walls; a West African quarter and a mass of sordid adobe constructions. were built around ''Bab Marrakesh.'' The market gate was surrounded by warehouses and shops. inside the walls, was is the Moroccan city, semi-modern in places: winding streets, point or poorly paved, that the slightest rain changes in mud-holes, narrow squares, tightened between terraced houses, low and without architecture A apart from the mosques, a few residential doors and the German consulate, no monument attracts the gaze of the visitor "lieutenant segongs, 1910".Colonial port

Hubert Lyautey

Louis Hubert Gonzalve Lyautey (17 November 1854 – 27 July 1934) was a French Army general and colonial administrator. After serving in Indochina and Madagascar, he became the first French Resident-General in Morocco from 1912 to 1925. Early in ...

was the first French military governor in Morocco, with the title ''résident général''. In 1913, Lyautey invited Henri Prost

Henri Prost (February 25, 1874 – July 16, 1959) was a French architect and urban planner. He was noted in particularly for his work in Morocco and Turkey, where he created a number of comprehensive city plans for Casablanca, Fes, Marrakesh ...

to handle the urban planning of Moroccan cities, and his work in Casablanca was lauded for applying principles of urbanization. The ''ville européenne'' or "European city" fanned out Eastward around Casablanca's medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

, or—as the French called it—''la ville indigène''. The area just outside the eastern walls of the medina, which had previously been used as a market space, ''Assouq Elkbiir'' (السوق الكبير) the "big market", was transformed into ''Place de France'', now known as United Nations Square. Dominated by the clock tower

Clock towers are a specific type of structure which house a turret clock and have one or more clock faces on the upper exterior walls. Many clock towers are freestanding structures but they can also adjoin or be located on top of another buildi ...

built in 1908, it demarked a contact point between the Moroccan medina and the European ''nouvelle ville''.

In 1915, the French authorities held the Exposition Franco-Marocaine, a display of French soft power

In politics (and particularly in international politics), soft power is the ability to co-opt rather than coerce (contrast hard power). In other words, soft power involves shaping the preferences of others through appeal and attraction. A defin ...

after the bombardment of the city in 1907 and during the ongoing ''pacification'' or wars of occupation—notably the Zaian War

Zayanes ( ber, Azayi (singular), (plural); ) are a Berbers, Berber population inhabiting the Khenifra region, located in the central Middle Atlas mountains of Morocco.

Zayanes tribes are known for their attachment to ancestral land and for the ...

—and an opportunity to inventory Morocco's resources and crafts.

In 1930, Casablanca hosted a round of the Formula One

Formula One (also known as Formula 1 or F1) is the highest class of international racing for open-wheel single-seater formula racing cars sanctioned by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). The World Drivers' Championship, ...

world championship. The race was held at the new Anfa Racecourse. In 1958, the race was held at Ain-Diab

Ain Diab ( ar, عين الذئاب) is a commune located at the Corniche of Casablanca, Morocco. The commune is affluent and famous for the fashionable stretch of coastline known as the Corniche. There are numerous hotels, restaurants, nightclubs, ...

circuit - ''(see Moroccan Grand Prix

The Moroccan Grand Prix (Arabic: سباق الجائزة الكبرى المغربي) was a Grand Prix first organised in 1925 in Casablanca, Morocco with the official denomination of "Casablanca Grand Prix".

History

In 1930, the race was held ...

)''. In 1983, Casablanca hosted the Mediterranean Games

The Mediterranean Games is a multi-sport event organised by the International Committee of Mediterranean Games (CIJM). It is held every four years among athletes from countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea in Africa, Asia and Europe. The fir ...

.

Under Lyautey's tenure, Casablanca transformed into Morocco's economic center and Africa's biggest port.

Under Lyautey's tenure, Casablanca transformed into Morocco's economic center and Africa's biggest port. Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

's street plan is based on that of a French architect named Henri Prost

Henri Prost (February 25, 1874 – July 16, 1959) was a French architect and urban planner. He was noted in particularly for his work in Morocco and Turkey, where he created a number of comprehensive city plans for Casablanca, Fes, Marrakesh ...

, who placed the center of the city where the main market of Anfa

Anfa (Berber language: ''Anfa'' or ''Anaffa'', ⴰⵏⴼⴰ; ar, أنفا; es, Anafe; pt, Anafé) was the ancient toponym for Casablanca during the classical period. The city was founded by Berbers around the 10th century BC, with the Romans un ...

had been. From this point all main streets radiate to the east and to the south.

A 1937-1938 typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

outbreak was exploited by colonial authorities to justify the appropriation of urban spaces in Casablanca. Bidonvilles were cleated out of the center and their residents displaced.

World War II

Casablanca was an important strategic port duringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. In November 1942, the British and Americans organised a 3-pronged attack on North Africa ''(Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

)'', of which the westernmost one was at Casablanca.

The Task Force landed before daybreak on 8 November 1942, at three points in Morocco: Asfi (Operation Blackstone

Operation Blackstone was a part of Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa during World War II. The operation called for American amphibious troops to land at and capture the French-held port of Safi in French Morocco. The landings ...

), Fedala

Mohammedia ( ar, المحمدية, al-muḥammadiyya; ber, ⴼⴹⴰⵍⴰ, Fḍala), known until 1960 as Fedala, is a port city on the west coast of Morocco between Casablanca and Rabat in the region of Casablanca-Settat. It hosts the most impo ...

( Operation Brushwood, the largest landing with 19,000 men), and Mehdiya-Port Lyautey

Kenitra ( ar, القُنَيْطَرَة, , , ; ber, ⵇⵏⵉⵟⵔⴰ, Qniṭra; french: Kénitra) is a city in north western Morocco, formerly known as Port Lyautey from 1932 to 1956. It is a port on the Sebou river, has a population in 201 ...

( Operation Goalpost). Because it was hoped that the French would not resist, there were no preliminary bombardments. This proved to be a costly error as French defenses took a toll of American landing forces.

On the night of 7 November, pro-Allied General Antoine Béthouart

Marie Émile Antoine Béthouart (17 December 1889 – 17 October 1982) was a French Army general who served during World War I and World War II.

Born in Dole, Jura, in the Jura Mountains, Béthouart graduated from Saint-Cyr military academy a ...

attempted a '' coup d'etat'' against the French command in Morocco, so that he could surrender to the Allies the next day. His forces surrounded the villa of General Charles Noguès

Charles Noguès (13 August 1876 – 20 April 1971) was a French general. He graduated from the École Polytechnique, and he was awarded the Grand Croix of the Legion of Honour in 1939.

Biography

On 20 March 1933, he became commander of the 1 ...

, the Vichy-loyal high commissioner. However, Noguès telephoned loyal forces, who stopped the coup. In addition, the coup attempt alerted Noguès to the impending Allied invasion, and he immediately bolstered French coastal defenses.

At Safi, the objective being capturing the port facilities to land the Western Task Force's medium tanks, the landings were mostly successful. The landings were begun without covering fire, in the hope that the French would not resist at all. However, once French coastal batteries opened fire, Allied warships returned fire. By the time General Ernest Harmon's 2nd Armored Division arrived, French snipers had pinned the assault troops (most of whom were in combat for the first time) on Safi's beaches. Most of the landings occurred behind schedule. Carrier aircraft destroyed a French truck convoy bringing reinforcements to the beach defenses. Safi surrendered on the afternoon of 8 November. By 10 November, the remaining defenders were pinned down, and the bulk of Harmon's forces raced to join the siege of Casablanca.

At Port-Lyautey, the landing troops were uncertain of their position, and the second wave was delayed. This gave the French defenders time to organize resistance, and the remaining landings were conducted under artillery bombardment. With the assistance of air support from the carriers, the troops pushed ahead, and the objectives were captured.

At

At Safi, the objective being capturing the port facilities to land the Western Task Force's medium tanks, the landings were mostly successful. The landings were begun without covering fire, in the hope that the French would not resist at all. However, once French coastal batteries opened fire, Allied warships returned fire. By the time General Ernest Harmon's 2nd Armored Division arrived, French snipers had pinned the assault troops (most of whom were in combat for the first time) on Safi's beaches. Most of the landings occurred behind schedule. Carrier aircraft destroyed a French truck convoy bringing reinforcements to the beach defenses. Safi surrendered on the afternoon of 8 November. By 10 November, the remaining defenders were pinned down, and the bulk of Harmon's forces raced to join the siege of Casablanca.

At Port-Lyautey, the landing troops were uncertain of their position, and the second wave was delayed. This gave the French defenders time to organize resistance, and the remaining landings were conducted under artillery bombardment. With the assistance of air support from the carriers, the troops pushed ahead, and the objectives were captured.

At Fedala

Mohammedia ( ar, المحمدية, al-muḥammadiyya; ber, ⴼⴹⴰⵍⴰ, Fḍala), known until 1960 as Fedala, is a port city on the west coast of Morocco between Casablanca and Rabat in the region of Casablanca-Settat. It hosts the most impo ...

, weather disrupted the landings. The landing beaches again came under French fire after daybreak. Patton landed at 08:00, and the beachheads were secured later in the day. The Americans surrounded the port of Casablanca by 10 November, and the city surrendered an hour before the final assault was due to take place.

Casablanca hosted the Casablanca Conference

The Casablanca Conference (codenamed SYMBOL) or Anfa Conference was held at the Anfa Hotel in Casablanca, French Morocco, from January 14 to 24, 1943, to plan the Allied European strategy for the next phase of World War II. In attendance were U ...

-called even "Anfa Conference"- in 1943 (from January 14 to January 24), in which Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

and Roosevelt

Roosevelt may refer to:

*Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), 26th U.S. president

*Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), 32nd U.S. president

Businesses and organisations

* Roosevelt Hotel (disambiguation)

* Roosevelt & Son, a merchant bank

* Roosevel ...

discussed the progress of the war. Casablanca was the site of a large American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

air base, which was the staging area for all American aircraft for the European Theater of Operations

The European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA) was a Theater of Operations responsible for directing United States Army operations throughout the European theatre of World War II, from 1942 to 1945. It commanded Army Ground For ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

Post-war period

In April 1953, film ''Salut Casa!

''Salut Casa!'' (or ''Casablanca Boom Town'' for English audiences) is a 1952 pseudo-documentary propaganda short film about Casablanca under the French Protectorate. Directed by Jean Vidal, it was screened at the 1953 Cannes Film Festival. The f ...

—''a "pseudo-documentary" propaganda piece intended for French audiences—played at the Cannes Film Festival

The Cannes Festival (; french: link=no, Festival de Cannes), until 2003 called the International Film Festival (') and known in English as the Cannes Film Festival, is an annual film festival held in Cannes, France, which previews new films o ...

. The film shows the colonial machine carrying out its ''mission civilizatric''e at full steam. The French government described Casablanca as a "laboratory of urbanism," and the French urbanist Michel Écochard

Michel Écochard (11 March 1905 - 24 May 1985) was a French architect and urban planner. He played a large part in the urban planning of Casablanca from 1946 to 1952 during the French Protectorate, then in the French redevelopment of Damascu ...

—director of the ''Service de l’Urbanisme,'' Casablanca's urban planning office at the time—featured prominently in the film, discussing how challenges such as internal migration Internal migration or domestic migration is human migration within a country. Internal migration tends to be travel for education and for economic improvement or because of a natural disaster or civil disturbance, though a study based on the full ...

and rapid urbanization

Urbanization (or urbanisation) refers to the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It is predominantly t ...

were being handled in Casablanca.

In July of the same year, Morocco and its '' Groupe des Architectes Modernes Marocains'' (GAMMA) had its own section at the ''Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture'' Moderne or CIAM. The architects from Morocco presented an intense study of daily life in Casablanca's bidonvilles. To consider the ad-hoc

Ad hoc is a Latin phrase meaning literally 'to this'. In English, it typically signifies a solution for a specific purpose, problem, or task rather than a generalized solution adaptable to collateral instances. (Compare with ''a priori''.)

Com ...

huts built by penniless immigrants from rural parts of the country worthy of study—let alone to hold them as examples for modernist architects to learn from—was radical and revolutionary, and caused a schism among modernists.

Young architects of the controversial Team X

Team 10 – just as often referred to as Team X or Team Ten – was a group of architects and other invited participants who assembled starting in July 1953 at the 9th Congress of the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM) and c ...

, such as Shadrach Woods

Shadrach Woods (June 30, 1923 – July 31, 1973) was an American architect, urban planner and theorist.

Biography

Schooled in engineering at New York University and in literature and philosophy at Trinity College, Dublin, Woods joined the Par ...

, Alexis Josic

Aljoša Josić ( sr, Аљоша Јосић), known in France as Alexis Josic (Bečej, Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, 24 May 1921 - 10 March 2011) was a French architect.

Son of the Serbian painter Mladen Josić, he studied architecture in ...

, and Georges Candilis

Georges Candilis ( el, Γεώργιος Κανδύλης; 29 March 1913 – 10 May 1995) was a Greek-French architect and urbanist.

Biography

Born in Azerbaijan, he moved to Greece and graduated from the Polytechnic School of Athens between 19 ...

were active in Casablanca designing ''cités'', modular public housing

Public housing is a form of housing tenure in which the property is usually owned by a government authority, either central or local. Although the common goal of public housing is to provide affordable housing, the details, terminology, def ...

units, that took vernacular life into account. Elie Azagury

Elie Azagury (; 1918-2009) was an influential Moroccan architect and director of the (GAMMA) after Moroccan independence in 1956. He is considered the first Moroccan modernist architect, with works in cities such as Casablanca, Tangier, and Agadi ...

, the first Moroccan modernist architect, led GAMMA after independence in 1956.

Toward Independence

During the 1940s and 1950s, Casablanca was a major center of anti-colonial struggle.

In 1947, when the Sultan went to the

During the 1940s and 1950s, Casablanca was a major center of anti-colonial struggle.

In 1947, when the Sultan went to the Tangier International Zone

The Tangier International Zone ( ''Minṭaqat Ṭanja ad-Dawliyya'', , es, Zona Internacional de Tánger) was a international zone centered on the city of Tangier, Morocco, which existed from 1924 until its reintegration into independent Moroc ...

to deliver a speech requesting independence from colonial powers, the first stage of the Revolution of the King and the People

The Revolution of the King and the People () was a Moroccan anti-colonial national liberation movement to end the French Protectorate and break free from the French colonial empire. The name refers to coordination between the Moroccan monarch S ...

, French colonial forces instigated a conflict between Senegalese ''Tirailleurs'' serving the French colonial empire

The French colonial empire () comprised the overseas colonies, protectorates and mandate territories that came under French rule from the 16th century onward. A distinction is generally made between the "First French Colonial Empire", that exist ...

and Moroccan locals in a failed attempt to sabotage the Sultan's journey to Tangier. This massacre, remembered in Casablanca as '' Darbat Salighan'' (), lasted for about 24 hours from April 7–8, 1947, as the ''tirailleurs'' fired randomly into residential buildings in working-class neighborhoods, killing between 180 and 1000 Moroccan civilians. The Sultan returned to Casablanca to comfort the families of the victims, then proceeded to Tangier to deliver the historic speech.

The assassination of the Tunisian labor unionist Farhat Hached

Farhat Hached (; 2 February 1914 – 5 December 1952) was a Tunisian labor unionist and independence activist assassinated by the '' Main Rouge'', a French terrorist organization operated by French foreign intelligence.

He was one of the leader ...

by ''La Main Rouge ''La Main Rouge'' ( en, The Red Hand) was a French terrorist organization operated by the French foreign intelligence agency ( External Documentation and Counter-Espionage Service), or SDECE, in the 1950s. Its purpose was to eliminate the supporte ...

''—the clandestine militant wing of French intelligence

This is a list of current and former French intelligence agencies.

Currently active

*DGSE: Directorate-General for External Security – ''Direction générale de la sécurité extérieure''. It is the military foreign intelligence agency, whi ...

—sparked protests in cities around the world and riots in Casablanca from December 7–8, 1952. The ''Union Générale des Syndicats Confédérés du Maroc'' (UGSCM) and the Istiqlal Party

The Istiqlal Party ( ar, حزب الإستقلال, translit=Ḥizb Al-Istiqlāl, lit=Independence Party; french: Parti Istiqlal; zgh, ⴰⴽⴰⴱⴰⵔ ⵏ ⵍⵉⵙⵜⵉⵇⵍⴰⵍ) is a political party in Morocco. It is a conservative and ...

organized a general strike in the ''Carrières Centrales

''Carrières Centrales'' () is a series of modernist housing developments in Casablanca, Morocco designed in the 1950s by architects Georges Candillis, Shadrach Woods, Alexis Josic. The development aimed to create utopian "habitats" that would p ...

'' in Hay Mohammadi

Hay Mohammadi or Hay Mohammedi ( ar, الحي المحمدي) is an arrondissement of eastern Casablanca, in the Aïn Sebaâ - Hay Mohammadi district of the Casablanca-Settat region of Morocco. As of 2004 it had 156,501 inhabitants.

Notable res ...

on December 7.

On December 24, 1953, in response to violence and abuses from French colonists culminating in the forced exile of Sultan Mohammed V on Eid al-Adha

Eid al-Adha () is the second and the larger of the two main holidays celebrated in Islam (the other being Eid al-Fitr). It honours the willingness of Ibrahim (Abraham) to sacrifice his son Ismail (Ishmael) as an act of obedience to Allah's co ...

, Mohammed Zerktouni orchestrated the bombing of the Central Market Central Market may refer to:

*Central Market, a 2009 album by Tyondai Braxton

Fresh food markets

* Adelaide Central Market, Australia

* Cardiff Central Market, Wales

*Central Market, Hong Kong

* Central Market, Casablanca, Morocco

* Riga Central ...

, killing 16 people.

Since independence

Morocco regained independence from France on 2 March 1956.Casablanca Group

January 4–7, 1961, the city hosted an ensemble of progressive African leaders during the Casablanca Conference of 1961. King Muhammad V received attendance were Gamal Abd An-Nasser of theUnited Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic (UAR; ar, الجمهورية العربية المتحدة, al-Jumhūrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Muttaḥidah) was a sovereign state in the Middle East from 1958 until 1971. It was initially a political union between Eg ...

, Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah (born 21 September 190927 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He was the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, having led the Gold Coast to independence from Britain in 1957. An in ...

of Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

, Modibo Keïta

Modibo Keïta (4 June 1915 – 16 May 1977) was the first President of Mali (1960–1968) and the Prime Minister of the Mali Federation. He espoused a form of African socialism.

Youth

Keïta was born in Bamako-Coura, a neighborhood of Bama ...

of Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mali ...

, and Ahmed Sékou Touré

Ahmed Sékou Touré (var. Sheku Turay or Ture; N'Ko: ; January 9, 1922 – March 26, 1984) was a Guinean political leader and African statesman who became the first president of Guinea, serving from 1958 until his death in 1984. Touré was am ...

of Guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

, as well as Ferhat Abbas Ferhat is a Turkish given name and the Turkish spelling of the Persian name Ferhad ( fa, فرهاد, ''farhād''). It may refer to:

Given name Ferhad

* Ferhad Ayaz (born 1994), Turkish-Swedish footballer

* Ferhad Pasha Sokolović 16th-century Ott ...

, president of the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic

The Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic ( ar, الحكومة المؤقتة للجمهورية الجزائرية, ; French: ''Gouvernement provisoire de la République algérienne'') was the government-in-exile of the Algerian Natio ...

. Notably absent was Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba (; 2 July 1925 – 17 January 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Republic of the Congo) from June u ...

of the Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo (french: République du Congo, ln, Republíki ya Kongó), also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply either Congo or the Congo, is a country located in the western coast of Central Africa to the w ...

, who had been in prison since September 1960. This conference gave birth to the pan-Africanist Casablanca Group

The Casablanca Group, sometimes known as the 'Casablanca bloc', was a short-lived, informal association of African states with a shared vision of the future of Africa and of Pan-Africanism in the early 1960s. The group was composed of seven states ...

or the " Casablanca Bloc" and ultimately to the African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union consisting of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the Africa ...

.

Jewish emigration

Casablanca was a major departure point for Jews leaving Morocco throughOperation Yachin

Operation Yakhin was an operation to secretly emigrate Moroccan Jews to Israel, conducted by Israel's Mossad between November 1961 and spring 1964. About 97,000 left for Israel by plane and ship from Casablanca and Tangier via France and Italy. ...

, an operation conducted by Mossad

Mossad ( , ), ; ar, الموساد, al-Mōsād, ; , short for ( he, המוסד למודיעין ולתפקידים מיוחדים, links=no), meaning 'Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations'. is the national intelligence agency ...

to secretly migrate Moroccan Jews

Moroccan Jews ( ar, اليهود المغاربة, al-Yahūd al-Maghāriba he, יהודים מרוקאים, Yehudim Maroka'im) are Jews who live in or are from Morocco. Moroccan Jews constitute an ancient community dating to Roman times. Jews b ...

to Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

between November 1961 and spring 1964.

1965 riots

The 1965 student protests, which spread to cities around the country and devolved into riots, started on March 22, 1965, in front ofLycée Mohammed V

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 15.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for children between ...

in Casablanca; there were almost 15,000 students there, according to a witness.Par Omar Brouksy,Que s'est-il vraiment passé le 23 mars 1965?

, ''Jeune Afrique'', 21 March 2005

Archived

The protests started as a peaceful march to demand the right to public higher education for Morocco, but were violently dispersed. The following day, students returned to Lycée Mohammed V along with workers, the unemployed, and the poor, this time vandalizing stores, burning buses and cars, throwing stones, and chanting slogans against King

Hassan II Hassan, Hasan, Hassane, Haasana, Hassaan, Asan, Hassun, Hasun, Hassen, Hasson or Hasani may refer to:

People

*Hassan (given name), Arabic given name and a list of people with that given name

*Hassan (surname), Arabic, Jewish, Irish, and Scottis ...

, who since assuming the throne in 1961, had consolidated political power within monarchy and gone to war with the newly independent, newly socialist Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

. The National Union of the Students of Morocco—a nationalist, anti-colonial student group affiliated with Mehdi Ben Barka use both this parameter and , birth_date to display the person's date of birth, date of death, and age at death) -->

, death_place =

, death_cause =

, body_discovered =

, resting_place =

, resting_place_coordinates = ...

's party, the National Union of Popular Forces

The National Union of Popular Forces ( ar, الاتحاد الوطني للقوات الشعبية; , UNFP) was founded in 1959 in Morocco by Mehdi Ben Barka and his entourage, because they found that the Istiqlal Party was not radical enough.

E ...

—overtly opposed and criticized Hassan II.Miller, ''A History of Modern Morocco'' (2013), pp. 162�168

��169. The riots were repressed with tanks deployed for two days, and General

Mohamed Oufkir

General Mohammad Oufkir ( ar, محمد أوفقير; 14 May 1920 − 16 August 1972) was a Moroccan senior military officer who held many important governmental posts. It is believed that he was assassinated for his alleged role in the failed 1 ...

fired on the crowd from a helicopter.

The king blamed the events on teachers and parents, and declared in a speech to the nation on March 30, 1965: "''Allow me to tell you that there is no greater danger to the State than a so-called intellectual. It would have been better if you were all illiterate.''”

1965 Arab League Summit

A secret

A secret Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

summit was held in Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

September 1965. Shlomo Gazit

Shlomo Gazit ( he, שלמה גזית; 22 October 1926 – 8 October 2020) was an Israeli military officer and academic. A Major General in the Israel Defense Forces, he headed Israel's Military Intelligence Directorate. He later served as Presid ...

of Israeli intelligence

Mossad ( , ), ; ar, الموساد, al-Mōsād, ; , short for ( he, המוסד למודיעין ולתפקידים מיוחדים, links=no), meaning 'Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations'. is the national intelligence agency ...

said that Hassan II Hassan, Hasan, Hassane, Haasana, Hassaan, Asan, Hassun, Hasun, Hassen, Hasson or Hasani may refer to:

People

*Hassan (given name), Arabic given name and a list of people with that given name

*Hassan (surname), Arabic, Jewish, Irish, and Scottis ...

invited Mossad

Mossad ( , ), ; ar, الموساد, al-Mōsād, ; , short for ( he, המוסד למודיעין ולתפקידים מיוחדים, links=no), meaning 'Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations'. is the national intelligence agency ...

and Shin Bet

The Israel Security Agency (ISA; he, שֵׁירוּת הַבִּיטָּחוֹן הַכְּלָלִי; ''Sherut ha-Bitaẖon haKlali''; "the General Security Service"; ar, جهاز الأمن العام), better known by the acronym Shabak ( he, ...

agents to bug the Casablanca hotel where the conference would be held to record the conversations of the Arab leaders. This information was instrumental in the heavy military defeats of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

to the Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

is in the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

. Prior to the war, King Hassan II had developed a reciprocal relationship with the Israeli intelligence, who had assisted him in carrying out an operation in France to abduct and 'disappear' Mehdi Ben Barka use both this parameter and , birth_date to display the person's date of birth, date of death, and age at death) -->

, death_place =

, death_cause =

, body_discovered =

, resting_place =

, resting_place_coordinates = ...

, a leftist Moroccan leader who had been based in Paris.

Years of Lead

During the " Years of Lead," Derb Moulay Cherif Prison in Hay Muhammadi was used as a secret prison for the interrogation and torture of dissidents of Hassan II. Among others, the Jewish Moroccan activistAbraham Serfaty

Abraham Serfaty ( ar, أبراهام سرفاتي; January 16, 1926 – 18 November 2010) was an internationally prominent Moroccan Marxist-Leninist dissident, militant, and political activist, who was imprisoned for years by King Hassan I ...

of the radical Moroccan leftist group Ila al-Amam was tortured there. The poet and activist Saida Menebhi

Saida Menebhi (1952 in Marrakesh – 11 December 1977 in Casablanca) was a Moroccan poet, high school teacher, and activist with the Marxist revolutionary movement Ila al-Amam. In 1975, she, together with five other members of the movement, wa ...

died there on December 11, 1977, after a 34-day hunger strike.

The music of Nass El Ghiwane

Nass El Ghiwane () are a musical group established in 1970 in Casablanca, Morocco. The group, which originated in avant-garde political theater, has played an influential role in Moroccan chaabi (or ''shaabi'').

Nass El Ghiwane were the first ...

represents some of the art that was created in opposition to the oppressive regime.

1981 riots

On May 29, 1981, riots broke out in Casablanca. At a time when Morocco was strained from six years in theWestern Sahara War

The Western Sahara War ( ar, حرب الصحراء الغربية, french: Guerre du Sahara occidental, es, Guerra del Sahara Occidental) was an armed struggle between the Sahrawi indigenous Polisario Front and Morocco from 1975 to 1991 (and ...

, a general strike was organized in response to increases in the cost of basic foods. Thousands of young people from the ''bidonvilles'' surrounding Casablanca formed mobs and stoned symbols of wealth in the city, including buses, banks, pharmacies, grocery stores, and expensive cars. Police and military units fired into the crowds. The official death toll according to the government was 66, while the opposition reported it was 637, most of whom were youths from the slums shot to death. This ''intifada

An intifada ( ar, انتفاضة ') is a rebellion or uprising, or a resistance movement. It is a key concept in contemporary Arabic usage referring to a legitimate uprising against oppression.Ute Meinel ''Die Intifada im Ölscheichtum Bahrain: ...

'' was the first of two IMF

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster globa ...

riots in Morocco—dubbed the "Hunger Revolts" by the international press—the second of which took place in 1984 primarily in northern cities such as Nador

Nador ( Riffian-Berber: ⵏⴰⴷⵓⵔ) is a coastal city and provincial capital in the northeastern Rif region of Morocco with a population of about 161,726 (2014 census).

Nador city is separated from the Mediterranean Sea by a salt lagoon nam ...

, Husseima, Tetuan, and al-Qasr al-Kebir.

Globalization and modernization

The firstMcDonald's

McDonald's Corporation is an American Multinational corporation, multinational fast food chain store, chain, founded in 1940 as a restaurant operated by Richard and Maurice McDonald, in San Bernardino, California, United States. They rechri ...

franchise on the African continent

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

and in the Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

opened on Ain Diab

Ain Diab ( ar, عين الذئاب) is a commune located at the Corniche of Casablanca, Morocco. The commune is affluent and famous for the fashionable stretch of coastline known as the Corniche. There are numerous hotels, restaurants, nightclubs, ...

in 1992.

The city is now developing a tourism

Tourism is travel for pleasure or business; also the theory and practice of touring (disambiguation), touring, the business of attracting, accommodating, and entertaining tourists, and the business of operating tour (disambiguation), tours. Th ...

industry. Casablanca has become the economic and business capital of Morocco, while Rabat

Rabat (, also , ; ar, الرِّبَاط, er-Ribât; ber, ⵕⵕⴱⴰⵟ, ṛṛbaṭ) is the capital city of Morocco and the country's seventh largest city with an urban population of approximately 580,000 (2014) and a metropolitan populati ...

is the political capital.

In March 2000, women's groups organised demonstrations in Casablanca proposing reforms to the legal status of women in the country. 40,000 women attended, calling for a ban on polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is married ...

and the introduction of divorce law

This article is a general overview of divorce laws around the world. Every nation in the world allows its residents to divorce under some conditions except the Philippines (though Muslims in the Philippines have the right to divorce) and the Vatic ...

(divorce being a purely religious procedure at that time). Although counter-demonstration attracted half a million participants, the movement for change started in 2000 was influential on King Mohammed VI

Mohammed VI ( ar, محمد السادس; born 21 August 1963) is the King of Morocco. He belongs to the 'Alawi dynasty and acceded to the throne on 23 July 1999, upon the death of his father, King Hassan II.

Upon ascending to the throne, Moha ...

, and he enacted a new ''Mudawana

The ''Mudawana Ousra'' (or ''Moudawana Ousra'', ar, المدوّنة, lit=code), short for ''mudawwanat al-aḥwāl al-ousaria-shakhṣiyyah'' (, ), is the personal status code, also known as the family code, in Moroccan law. It concerns issu ...

'', or family law, in early 2004, meeting some of the demands of women's rights activists.

On May 16, 2003, 33 civilians were killed and more than 100 people were injured when Casablanca was hit by a multiple suicide bomb attack carried out by Moroccans and claimed by some to have been linked to al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremism, Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arab, Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military ta ...

.

A string of suicide bombings struck the city in early 2007. A suspected militant blew himself up at a Casablanca internet cafe on March 11, 2007. On April 10, three suicide bombers blew themselves up during a police raid of their safe house. Two days later, police set up barricades around the city and detained two more men who had escaped the raid. On April 14, two brothers blew themselves up in downtown Casablanca, one near the American Consulate, and one a few blocks away near the American Language Center. Only one person was injured aside from the bombers, but the consulate was closed for more than a month.

The first line of the Casablanca Tramway

, color =

, logo = Logo-casatramway.png

, logo_width =

, logo_alt =

, image = Casablance tram Citadis placedesnatio ...

, which as of 2019 consists of two lines, was inaugurated December 2012. Al-Boraq

Al Boraq () is a high-speed rail service between Casablanca and Tangier, operated by ONCF in Morocco. The first of its kind on the African continent, the high-speed service was inaugurated on 15 November 2018 by King Mohammed VI of Morocco, fo ...

, a high speed rail service connecting Casablanca and Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the cap ...

and the high-speed rail service on the African continent, was inaugurated on November 15, 2018.

See also

*Acheulean

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French ''acheuléen'' after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated ...

*Aterian

The Aterian is a Middle Stone Age (or Middle Palaeolithic) stone tool industry centered in North Africa, from Mauritania to Egypt, but also possibly found in Oman and the Thar Desert. The earliest Aterian dates to c. 150,000 years ago, at the sit ...

*Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymous ...

*Mousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an archaeological industry of stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and to the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and West Asia. The Mousterian largely defines the latt ...

* Timeline of Casablanca

References

Further reading

External links

*''Maghreb Arabe Presse'': 500k-year human fossil remains found in Casablanca (05/26/2006)

{{Romano-Berber cities in Roman Africa Mauretania Tingitana

Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...