History of Cardiff on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Cardiffa City and County Borough and the capital of

The history of Cardiffa City and County Borough and the capital of

In common with the people living all over Great Britain, over the following centuries the people living around what is now known as Cardiff assimilated new immigrants and exchanged ideas of the

In common with the people living all over Great Britain, over the following centuries the people living around what is now known as Cardiff assimilated new immigrants and exchanged ideas of the

Excavations from inside Cardiff Castle walls suggest

Excavations from inside Cardiff Castle walls suggest

In 1091,

In 1091,

In 1536, the Act of Union between England and Wales led to the creation of the

In 1536, the Act of Union between England and Wales led to the creation of the

In 1793,

In 1793,

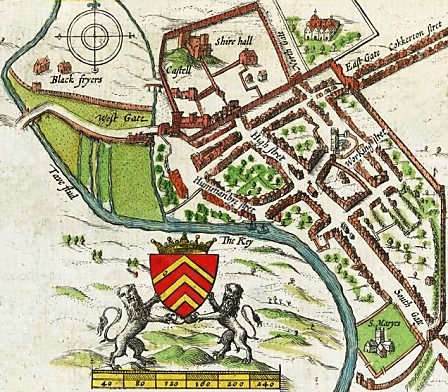

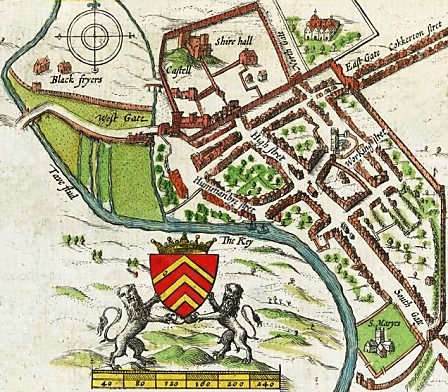

Cardiff's Medieval Town Defences

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Cardiff History of Cardiff,

The history of Cardiffa City and County Borough and the capital of

The history of Cardiffa City and County Borough and the capital of Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

spans at least 6,000 years. The area around Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United Kingd ...

has been inhabited by modern humans

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, an ...

since the Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

Period. Four Neolithic burial chambers stand within a radius of of Cardiff City Centre, with the St Lythans burial chamber

, alternate_name =

, image = St Lythans burial chamber (4794) (cropped).jpg

, caption =

, alt = a grassy field in which three large upright stones support a stone slab roof

, location = near St Lythans and Barry ()

, region = Vale ...

the nearest, at about to the west. Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

tumuli

A tumulus (plural tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or ''kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a mound of stones buil ...

are at the summit of Garth Hill

Garth Hill (usually called The Garth, or Garth Mountain, ''Mynydd y Garth'' in Welsh) is a hill located in between the communities of Llantwit Fardre and Pentyrch in Wales. The Garth can be seen from nearly the whole of the city of Cardiff and th ...

(''The Garth''; cy, Mynydd y Garth), within the county's northern boundary, and four Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

hillfort

A hillfort is a type of earthwork used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Some were used in the post-Roma ...

and enclosure

Enclosure or Inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or " common land" enclosing it and by doing so depriving commoners of their rights of access and privilege. Agreements to enclose land ...

sites have been identified within the City and County of Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United King ...

boundary, including Caerau Hillfort, an enclosed area of . Until the Roman conquest of Britain

The Roman conquest of Britain refers to the conquest of the island of Britain by occupying Roman forces. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the southern half of Britain by 87 when the Staneg ...

, Cardiff was part of the territory of an Iron Age Celtic British tribe called the Silures

The Silures ( , ) were a powerful and warlike tribe or tribal confederation of ancient Britain, occupying what is now south east Wales and perhaps some adjoining areas. They were bordered to the north by the Ordovices; to the east by the Dobunn ...

, which included the areas that would become known as Brecknockshire

, image_flag=

, HQ= Brecon

, Government= Brecknockshire County Council (1889-1974)

, Origin= Brycheiniog

, Status=

, Start= 1535

, End= ...

, Monmouthshire

Monmouthshire ( cy, Sir Fynwy) is a county in the south-east of Wales. The name derives from the historic county of the same name; the modern county covers the eastern three-fifths of the historic county. The largest town is Abergavenny, with ...

and Glamorgan

, HQ = Cardiff

, Government = Glamorgan County Council (1889–1974)

, Origin=

, Code = GLA

, CodeName = Chapman code

, Replace =

* West Glamorgan

* Mid Glamorgan

* South Glamorgan

, Motto ...

. The Roman fort

In the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, the Latin word ''castrum'', plural ''castra'', was a military-related term.

In Latin usage, the singular form ''castrum'' meant 'fort', while the plural form ''castra'' meant 'camp'. The singular and ...

established by the River Taff

The River Taff ( cy, Afon Taf) is a river in Wales. It rises as two rivers in the Brecon Beacons; the Taf Fechan (''little Taff'') and the Taf Fawr (''great Taff'') before becoming one just north of Merthyr Tydfil. Its confluence with the R ...

, which gave its name to the city''Caerdydd'', earlier ''Caerdyf'', from ''caer'' (fort) and ''Taf''was built over an extensive settlement that had been established by the Silures in the 50s AD.

Origins

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymous ...

hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

s from Central Europe began to migrate northwards from the end of the last ice age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gree ...

(between 12,000 and 10,000 years before present(BP)). The area that would become known as Wales had become free of glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

s by about 10,250 BP. At that time sea levels were much lower than today, and the shallower parts of what is now the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

were dry land. The east coast of present-day England and the coasts of present-day Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands were connected by the former landmass known as Doggerland

Doggerland was an area of land, now submerged beneath the North Sea, that connected Britain to continental Europe. It was flooded by rising sea levels around 6500–6200 BCE. The flooded land is known as the Dogger Littoral. Geological sur ...

, forming the British Peninsula on the European mainland. The post-glacial rise in sea level separated Wales and Ireland, forming the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Ce ...

. Doggerland was submerged by the North Sea and, by 8000 BP, the British Peninsula had become the island of Great Britain. John Davies has theorised that the story of ''Cantre'r Gwaelod

, also known as or ( en, The Lowland Hundred), is a legendary ancient sunken kingdom said to have occupied a tract of fertile land lying between Ramsey Island and Bardsey Island in what is now Cardigan Bay to the west of Wales. It has been des ...

's'' drowning and tales in the ''Mabinogion

The ''Mabinogion'' () are the earliest Welsh prose stories, and belong to the Matter of Britain. The stories were compiled in Middle Welsh in the 12th–13th centuries from earlier oral traditions. There are two main source manuscripts, create ...

'', of the waters between Wales and Ireland being narrower and shallower, may be distant folk memories of this time.

As Great Britain became heavily wooded, movement between different areas was restricted, and travel between what was to become known as Wales and continental Europe became easier by sea, rather than by land. People came to Wales by boat from the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

. These Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

colonists

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established a permanent residence there, often to colonize the area.

A settler who migrates to an area previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited may be described as a pioneer.

Settle ...

integrated with the indigenous people, gradually changing their lifestyles from a nomadic life of hunting and gathering, to become farmers, some of whom settled in the area that would become Glamorgan

, HQ = Cardiff

, Government = Glamorgan County Council (1889–1974)

, Origin=

, Code = GLA

, CodeName = Chapman code

, Replace =

* West Glamorgan

* Mid Glamorgan

* South Glamorgan

, Motto ...

. They cleared the forests to establish pasture and to cultivate the land, developed new technologies such as ceramics and textile production, and they brought a tradition of long barrow

Long barrows are a style of monument constructed across Western Europe in the fifth and fourth millennia BCE, during the Early Neolithic period. Typically constructed from earth and either timber or stone, those using the latter material repres ...

construction that began in continental Europe during the 7th millennium BC.

Archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

evidence from sites in and around Cardiff—the St Lythans burial chamber

, alternate_name =

, image = St Lythans burial chamber (4794) (cropped).jpg

, caption =

, alt = a grassy field in which three large upright stones support a stone slab roof

, location = near St Lythans and Barry ()

, region = Vale ...

, near Wenvoe

Wenvoe ( cy, Gwenfô) is a village, community and electoral ward between Barry and Cardiff in the Vale of Glamorgan, Wales. Nearby are the Wenvoe Transmitter near Twyn-yr-Odyn and the site of the former HTV Wales Television Centre at Culverhouse ...

(about west, southwest of Cardiff City Centre), the Tinkinswood burial chamber, near St. Nicholas, Vale of Glamorgan (about west of Cardiff City Centre), the Cae'rarfau Chambered Tomb

A chamber tomb is a tomb for burial used in many different cultures. In the case of individual burials, the chamber is thought to signify a higher status for the interred than a simple grave. Built from rock or sometimes wood, the chambers could a ...

, Creigiau

Creigiau is a dormitory settlement in the north-west of Cardiff, the capital of Wales. The village currently has about 1,500 houses and a population of approximately 5,000 people. The Cardiff electoral ward is called Creigiau/St. Fagans. The ...

(about northwest of Cardiff City Centre) and the Gwern y Cleppa Long Barrow, near Coedkernew

Coedkernew ( cy, Coedcernyw) is a community in the south west of the city of Newport, South Wales, in the Marshfield ward.

The parish is bounded by Percoed reen to the south, Nant-y-Selsig to the southwest, and Pound Hill to the west. The no ...

, Newport (about northeast of Cardiff City Centre)—shows that these Neolithic people had settled in the area around Cardiff from at least around 6,000 BP, about 1500 years before either Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, topped by connectin ...

or The Egyptian Great Pyramid of Giza

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the biggest Egyptian pyramid and the tomb of Fourth Dynasty pharaoh Khufu. Built in the early 26th century BC during a period of around 27 years, the pyramid is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, ...

was completed.

In common with the people living all over Great Britain, over the following centuries the people living around what is now known as Cardiff assimilated new immigrants and exchanged ideas of the

In common with the people living all over Great Britain, over the following centuries the people living around what is now known as Cardiff assimilated new immigrants and exchanged ideas of the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

and Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

cultures. Together with the approximate areas now known as Breconshire, Monmouthshire and the rest of Glamorgan, the area that would become known as Cardiff was settled by a Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

tribe called the Silures. There is a group of five tumuli

A tumulus (plural tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or ''kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a mound of stones buil ...

at the top of Mynydd y Garth—near the City and County of Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United King ...

's northern boundary—thought to be Bronze Age, one of which supports a trig. pillar on its flat top. Several Iron Age sites have been found in the City and County of Cardiff. They are: the Castle Field Camp, east of Graig Llywn, Pontprennau

Pontprennau is a ward and community in the north of the city of Cardiff, Wales, lying north of Pentwyn and Cyncoed, between the village of Old St Mellons and the farmlands east of Lisvane. The community had a population of 7,353 in 2011.

Histo ...

; Craig y Parc enclosure, Pentyrch; Llwynda Ddu Hillfort, Pentyrch; and Caerau Hillfort—an enclosed area of .

The Roman army invaded Great Britain in May AD 43. The area to the south east of the Fosse Way

The Fosse Way was a Roman road built in Britain during the first and second centuries AD that linked Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter) in the southwest and Lindum Colonia (Lincoln) to the northeast, via Lindinis (Ilchester), Aquae Sulis ( Bath), Corini ...

—between modern day Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

and Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

—was under Roman control by 47. British tribes from beyond this new frontier of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

resisted the Roman advance and the Silures, along with Caratacus

Caratacus ( Brythonic ''*Caratācos'', Middle Welsh ''Caratawc''; Welsh ''Caradog''; Breton ''Karadeg''; Greek ''Καράτακος''; variants Latin ''Caractacus'', Greek ''Καρτάκης'') was a 1st-century AD British chieftain of the C ...

( cy, Caradoc), attacked the Romans in 47 and 48. A Roman legion

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of ...

(thought to be the Twentieth) was defeated in 52 by the Silures.

Archaeological evidence shows that a settlement had been established by the Silures in central Cardiff in the 50s AD, probably during the period following their victory over the Roman army. The settlement included several large timber-framed buildings of up to by . The extent of the settlement is not known. Until the Romans established their fort, which they built on the earlier Silures settlement, the area that would become known as Cardiff remained outside the control of the Roman province of Britannia

Britannia () is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin ''Britannia'' was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Great ...

.

The Roman settlement

Excavations from inside Cardiff Castle walls suggest

Excavations from inside Cardiff Castle walls suggest Roman legion

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of ...

s arrived in the area as early as AD 54–68 during the reign of the Emperor Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unti ...

. The Romans defeated the Silures

The Silures ( , ) were a powerful and warlike tribe or tribal confederation of ancient Britain, occupying what is now south east Wales and perhaps some adjoining areas. They were bordered to the north by the Ordovices; to the east by the Dobunn ...

and exiled Caratacus

Caratacus ( Brythonic ''*Caratācos'', Middle Welsh ''Caratawc''; Welsh ''Caradog''; Breton ''Karadeg''; Greek ''Καράτακος''; variants Latin ''Caractacus'', Greek ''Καρτάκης'') was a 1st-century AD British chieftain of the C ...

to Rome. They then established their first fort

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

, built on this strategically important site where the River Taff

The River Taff ( cy, Afon Taf) is a river in Wales. It rises as two rivers in the Brecon Beacons; the Taf Fechan (''little Taff'') and the Taf Fawr (''great Taff'') before becoming one just north of Merthyr Tydfil. Its confluence with the R ...

and River Ely

The River Ely ( cy, Afon Elái) is in South Wales flowing generally southeast, from Tonyrefail to Cardiff.

The river is about long. The Ely's numerous sources lie in the mountains to the south of Tonypandy, near the town of Tonyrefail, ris ...

enter the Bristol Channel

The Bristol Channel ( cy, Môr Hafren, literal translation: "Severn Sea") is a major inlet in the island of Great Britain, separating South Wales from Devon and Somerset in South West England. It extends from the lower estuary of the River Seve ...

, on a site on which were built timber barracks, stores and workshops.

The Silures were not finally conquered until AD 75, when Sextus Julius Frontinus

Sextus Julius Frontinus (c. 40 – 103 AD) was a prominent Roman civil engineer, author, soldier and senator of the late 1st century AD. He was a successful general under Domitian, commanding forces in Roman Britain, and on the Rhine and Danube ...

' long campaign against them began to succeed, and they gained control of the whole of Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

. The Roman fort at Cardiff was rebuilt smaller than before, in the 70s AD on the site of the extensive previous settlement dating from the 50s AD. Another fort was built on the site around 250, with stone walls thick along with an earth bank, to help defend against attacks from Hibernia

''Hibernia'' () is the Classical Latin name for Ireland. The name ''Hibernia'' was taken from Greek geographical accounts. During his exploration of northwest Europe (c. 320 BC), Pytheas of Massalia called the island ''Iérnē'' (written ). ...

. This was used until the Roman army

The Roman army (Latin: ) was the armed forces deployed by the Romans throughout the duration of Ancient Rome, from the Roman Kingdom (c. 500 BC) to the Roman Republic (500–31 BC) and the Roman Empire (31 BC–395 AD), and its medieval contin ...

withdrew from the fort, and from the whole of the province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''Roman province, provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire ...

of Britannia

Britannia () is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin ''Britannia'' was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Great ...

, near the start of the 5th century.

The Viking settlement and the Middle Ages

During the early Dark Ages little is known of Cardiff. It is speculated that perhaps for long periods, raiders attacked the area, making Cardiff untenable, By 850 theVikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

attacked the Welsh coast and used Cardiff as a base and later as a port. Street names such as Dumballs Road and Womanby Street

Womanby Street is one of the oldest streets in Cardiff, the capital of Wales. Tracing its name back to origins within the Norse language, its original purpose was to link Cardiff Castle to its quay. In this way it became a trade hub and settling ...

come from the Vikings.

In 1091,

In 1091, Robert Fitzhamon

Robert Fitzhamon (died March 1107), or Robert FitzHamon (literally, 'Robert, son of Hamon'), Seigneur de Creully in the Calvados region and Torigny in the Manche region of Normandy, was the first Norman feudal baron of Gloucester and the Norma ...

the Lord of Glamorgan

The Lordship of Glamorgan was one of the most powerful and wealthy of the Welsh Marcher Lordships. The seat was Cardiff Castle. It was established by the conquest of Glamorgan from its native Welsh ruler, by the Anglo-Norman nobleman Robert FitzHa ...

, began work on the castle keep within the walls of the old Roman fort and by 1111, Cardiff town walls

Cardiff's town walls were a Medieval defensive wall enclosing much of the present day centre of Cardiff, the capital city of Wales, which included Cardiff Castle. It measured 1280 paces or in circumference and had an average thickness of betwe ...

had also been built and this was recorded by Caradoc of Llancarfan in his book ''Brut y Tywysogion

''Brut y Tywysogion'' ( en, Chronicle of the Princes) is one of the most important primary sources for Welsh history. It is an annalistic chronicle that serves as a continuation of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s ''Historia Regum Britanniae''. ''Bru ...

'' (''Chronicle of the Princes''). Cardiff Castle

Cardiff Castle ( cy, Castell Caerdydd) is a medieval castle and Victorian Gothic revival mansion located in the city centre of Cardiff, Wales. The original motte and bailey castle was built in the late 11th century by Norman invaders on top ...

has been at the heart of the city ever since. Soon a little town grew up in the shadow of the castle, made up primarily of settlers from England. Cardiff had a population of between 1,500 and 2,000 in the Middle Ages, a relatively normal size for a Welsh town in this period. Robert Fitzhamon died in 1107, later his daughter Mabel, married Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester

Robert FitzRoy, 1st Earl of Gloucester (c. 1090 – 31 October 1147 David Crouch, 'Robert, first earl of Gloucester (b. c. 1090, d. 1147)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 200Retrieved ...

, the illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as ''b ...

son of King Henry I of England

Henry I (c. 1068 – 1 December 1135), also known as Henry Beauclerc, was King of England from 1100 to his death in 1135. He was the fourth son of William the Conqueror and was educated in Latin and the liberal arts. On William's death in ...

. He built the first stone keep in Cardiff Castle, and he used it to imprison Robert II, Duke of Normandy

Robert Curthose, or Robert II of Normandy ( 1051 – 3 February 1134, french: Robert Courteheuse / Robert II de Normandie), was the eldest son of William the Conqueror and succeeded his father as Duke of Normandy in 1087, reigning until 1106. ...

from 1126 until his death in 1134, by order of King Henry I, who was the Duke's younger brother. During the same period Ralph "Prepositus de Kardi" ("Provost of Cardiff") took up office as the first Mayor of Cardiff. During this period after the Norman conquest they usually referred the leading figure by the Latin name of prepositus ( en, provost) meaning "leading man". Robert (Earl of Gloucester) died in 1147 and was succeeded by his son William, 2nd Earl of Gloucester who died without male heir in 1183. The lordship of Cardiff then passed to Prince John, later King John through his marriage to Isabel, Countess of Gloucester

Isabella, Countess of Gloucester (1173/1174 – 14 October 1217), was an English noblewoman who was married to King John prior to his accession.

Lineage

Isabella was the daughter of William Fitz Robert, 2nd Earl of Gloucester, and his wife Hawi ...

, William's daughter. John divorced Isabel but retained the lordship until her second marriage; to Geoffrey FitzGeoffrey de Mandeville, 2nd Earl of Essex

Earl of Essex is a title in the Peerage of England which was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title has been recreated eight times from its original inception, beginning with a new first Earl upon each new cre ...

in 1214 until 1216 when the lordship passed to Gilbert de Clare, 5th Earl of Hertford

Gilbert de Clare, 4th Earl of Hertford, 5th Earl of Gloucester, 1st Lord of Glamorgan, 7th Lord of Clare (1180 – 25 October 1230) was the son of Richard de Clare, 3rd Earl of Hertford (c. 1153–1217), from whom he inherited the Clare estate ...

.

Between 1158 and 1316 Cardiff was attacked on several occasions. Amongst the various attackers of the castle were Ifor Bach

Ifor Bach (meaning Ivor the Short) (fl. 1158) also known as Ifor ap Meurig and in anglicised form Ivor Bach, Lord of Senghenydd, was a twelfth-century resident in and a leader of the Welsh in south Wales.

Welsh Lord of Senghenydd

At this perio ...

, who captured the Earl of Gloucester

The title of Earl of Gloucester was created several times in the Peerage of England. A fictional earl is also a character in William Shakespeare's play ''King Lear.''

Earls of Gloucester, 1st Creation (1121)

*Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester (1100� ...

who at the time held the castle. Morgan ap Maredudd

Morgan ap Maredudd sometimes referred to as “Morgan the Rebel” (flourished 1270-1316), rebel, of Glamorgan.

Life

He was the son of Maredudd ap Gruffudd (c.1234-c.1275) the last Welsh lord of Caerleon of Machen, and Maud, daughter of Cadwall ...

apparently attacked the settlement during the revolt of Madog ap Llywelyn

Madog ap Llywelyn (died after 1312) was the leader of the Welsh revolt of 1294–95 against English rule in Wales and proclaimed "Prince of Wales". The revolt was surpassed in longevity only by the revolt of Owain Glyndŵr in the 15th century. Ma ...

in 1294. In 1316 Llywelyn Bren

Llywelyn Bren (), or Llywelyn ap Gruffudd ap Rhys / Llywelyn ap Rhys (also Llewelyn) or in en, Llywelyn of the Woods. He was a nobleman who led a 1316 revolt in Wales in the reign of King Edward II of England. It marked the last serious challen ...

, Ifor Bach's great-grandson, also attacked Cardiff Castle as part of a revolt. He was illegally executed in the town in 1318 on the order of Hugh Despenser the Younger

Hugh le Despenser, 1st Baron le Despenser (c. 1287/1289 – 24 November 1326), also referred to as "the Younger Despenser", was the son and heir of Hugh le Despenser, Earl of Winchester (the Elder Despenser), by his wife Isabella de Beauchamp, ...

.

By the end of the 13th century, Cardiff was the only town in Wales with a population exceeding 2,000, but it was relatively small compared to most other notable towns in the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 1 ...

. Cardiff had an established port in the Middle Ages and by 1327, it was declared a Staple port. The town had weekly markets and after 1340, Cardiff also had 2 annual fair

A fair (archaic: faire or fayre) is a gathering of people for a variety of entertainment or commercial activities. Fairs are typically temporary with scheduled times lasting from an afternoon to several weeks.

Types

Variations of fairs incl ...

s, which drew traders from all around Glamorgan

, HQ = Cardiff

, Government = Glamorgan County Council (1889–1974)

, Origin=

, Code = GLA

, CodeName = Chapman code

, Replace =

* West Glamorgan

* Mid Glamorgan

* South Glamorgan

, Motto ...

.

In 1404, Owain Glyndŵr

Owain ap Gruffydd (), commonly known as Owain Glyndŵr or Glyn Dŵr (, anglicised as Owen Glendower), was a Welsh leader, soldier and military commander who led a 15 year long Welsh War of Independence with the aim of ending English rule in Wa ...

burned Cardiff and took Cardiff Castle. As the town was still very small, most of the buildings were made of wood and the town was reduced to ashes. However, the town was rebuilt not long after and began to flourish once again.

County town of Glamorganshire

In 1536, the Act of Union between England and Wales led to the creation of the

In 1536, the Act of Union between England and Wales led to the creation of the shire

Shire is a traditional term for an administrative division of land in Great Britain and some other English-speaking countries such as Australia and New Zealand. It is generally synonymous with county. It was first used in Wessex from the beginn ...

of Glamorgan. Cardiff was made the county town

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, a county town is the most important town or city in a county. It is usually the location of administrative or judicial functions within a county and the place where the county's members of Parliament are elect ...

. Around this same time the Herbert family became the most powerful family in the area. In 1538, Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

closed the Dominican and Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related Mendicant orders, mendicant Christianity, Christian Catholic religious order, religious orders within the Catholic Church. Founded in 1209 by Italian Catholic friar Francis of Assisi, these orders include t ...

friaries in Cardiff, the remains of which were used as building materials. A writer around this period described Cardiff: "The River Taff runs under the walls of his honours castle and from the north part of the town to the south part where there is a fair quay and a safe harbour for shipping."

In 1542, Cardiff gained representation in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

for the first time. The next year, the English militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

system was introduced. In 1551, William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke was created first Baron Herbert of Cardiff

Earl of Pembroke is a title in the Peerage of England that was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title, which is associated with Pembroke, Pembrokeshire in West Wales, has been recreated ten times from its origin ...

.

Cardiff had become a Free Borough in 1542. In 1573, it was made a head port for collection of customs duties. In 1581, Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

granted Cardiff its first royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

. By 1602 Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; cy, Sir Benfro ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county in the South West Wales, south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and the rest by sea. The count ...

historian George Owen described Cardiff as "the fayrest towne in Wales yett not the welthiest. The town gained a second Royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

in 1608. During the Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War took place between February to August 1648 in Kingdom of England, England and Wales. It forms part of the series of conflicts known collectively as the 1639-1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which include the 1641� ...

, St. Fagans just to the west of the town, played host to the Battle of St Fagans

The Battle of St Fagans was a pitched battle during the Second English Civil War in 1648. A detachment from the New Model Army defeated an army of former Parliamentarian soldiers who had rebelled and were now fighting against Parliament.

B ...

. The battle, between a Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

rebellion and a New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

detachment, was a decisive victory for the Parliamentarians and allowed Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

to conquer Wales. It is the last major battle to occur in Wales, with a total death toll of about 200 (mostly Royalist) soldiers killed.

In the ensuing century Cardiff was at peace. In 1766, John Stuart, 1st Marquess of Bute

John Stuart, 1st Marquess of Bute PC, FRS (30 June 1744 – 16 November 1814), styled Lord Mount Stuart until 1792 and known as The Earl of Bute between 1792 and 1794, was a British nobleman, coalfield owner, diplomat and politician who sat in ...

married into the Herbert family and was later created Baron Cardiff. In 1778, he began renovations on Cardiff Castle. In the 1790s, a race track

A race track (racetrack, racing track or racing circuit) is a facility built for racing of vehicles, athletes, or animals (e.g. horse racing or greyhound racing). A race track also may feature grandstands or concourses. Race tracks are also u ...

, printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in wh ...

, bank and coffee room all opened, and Cardiff gained a stagecoach

A stagecoach is a four-wheeled public transport coach used to carry paying passengers and light packages on journeys long enough to need a change of horses. It is strongly sprung and generally drawn by four horses although some versions are draw ...

service to London. Despite these improvements, Cardiff's position in the Welsh urban hierarchy

The urban hierarchy ranks each city based on the size of population residing within the nationally defined statistical urban area. Because urban population depends on how governments define their metropolitan areas, urban hierarchies are convention ...

had declined over the 18th century. Iolo Morganwg

Edward Williams, better known by his bardic name Iolo Morganwg (; 10 March 1747 – 18 December 1826), was a Welsh antiquarian, poet and collector.Jones, Mary (2004)"Edward Williams/Iolo Morganwg/Iolo Morgannwg" From ''Jones' Celtic Encyclopedi ...

called it "an obscure and inconsiderable place", and the 1801 census found the population to be only 1,870, making Cardiff only the twenty-fifth largest town in Wales, well behind Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil (; cy, Merthyr Tudful ) is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Tydf ...

and Swansea

Swansea (; cy, Abertawe ) is a coastal city and the second-largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Swansea ( cy, links=no, Dinas a Sir Abertawe).

The city is the twenty-fifth largest in ...

.The Welsh Academy Encyclopedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press 2008.

Building of the docks to modern Cardiff

In 1793,

In 1793, John Crichton-Stuart, 2nd Marquess of Bute

John Crichton-Stuart, 2nd Marquess of Bute, KT, FRS (10 August 1793 – 18 March 1848), styled Lord Mount Stuart between 1794 and 1814, was a wealthy aristocrat and industrialist in Georgian and early Victorian Britain. He developed the coal ...

was born. He would spend his life building the Cardiff docks and would later be called "the creator of modern Cardiff". In 1815, a boat service between Cardiff and Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

was established, running twice weekly. In 1821, the Cardiff Gas Works was established.

The town grew rapidly from the 1830s onwards, when the Marquess of Bute

Marquess of the County of Bute, shortened in general usage to Marquess of Bute, is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1796 for John Stuart, 1st Marquess of Bute, John Stuart, 4th Earl of Bute.

Family history

John Stuart ...

built a dock which eventually linked to the Taff Vale Railway

The Taff Vale Railway (TVR) was a standard gauge railway in South Wales, built by the Taff Vale Railway Company to serve the iron and coal industries around Merthyr Tydfil and to connect them with docks in Cardiff. It was opened in stag ...

. Cardiff became the main port for exports of coal from the Cynon, Rhondda

Rhondda , or the Rhondda Valley ( cy, Cwm Rhondda ), is a former coalmining area in South Wales, historically in the county of Glamorgan. It takes its name from the River Rhondda, and embraces two valleys – the larger Rhondda Fawr valley ('' ...

, and Rhymney

Rhymney (; cy, Rhymni ) is a town and a community in the county borough of Caerphilly, South Wales. It is within the historic boundaries of Monmouthshire. With the villages of Pontlottyn, Fochriw, Abertysswg, Deri and New Tredegar, Rhymney is ...

valleys, and grew at a rate of nearly 80% per decade between 1840 and 1870. Much of the growth was due to migration

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

from within and outside Wales: in 1851, a quarter of Cardiff's population were English-born and more than 10% had been born in Ireland. By the 1881 census, Cardiff had overtaken both Merthyr and Swansea to become the largest town in Wales. Cardiff's new status as the premier town in South Wales was confirmed when it was chosen as the site of the University College South Wales and Monmouthshire in 1893.

Cardiff developed municipal slaughterhouse

A slaughterhouse, also called abattoir (), is a facility where animals are slaughtered to provide food. Slaughterhouses supply meat, which then becomes the responsibility of a packaging facility.

Slaughterhouses that produce meat that is no ...

s from 1835, one of the first cities in the United Kingdom to do so, and by the early twentieth century there were no private slaughterhouses.

Cardiff faced a challenge in the 1880s when David Davies of Llandinam and the Barry Railway Company promoted the development of rival docks at Barry Barry may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Barry (name), including lists of people with the given name, nickname or surname, as well as fictional characters with the given name

* Dancing Barry, stage name of Barry Richards (born c. 19 ...

. Barry docks had the advantage of being accessible in all tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravity, gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide t ...

s, and David Davies claimed that his venture would cause "grass to grow in the streets of Cardiff". From 1901 coal exports from Barry surpassed those from Cardiff, but the administration of the coal trade remained centred on Cardiff, in particular its Coal Exchange

The Coal Exchange (also known as the Exchange Building) is an historic building in Cardiff, Wales. It is designed in Renaissance Revival style. Built in 1888 as the Coal and Shipping Exchange to be used as a market floor and office building for ...

, where the price of coal on the British market was determined and the first million-pound deal was struck in 1907. The city also strengthened its industrial base with the decision of Guest, Keen and Nettlefolds

GKN Ltd is a British multinational automotive and aerospace components business headquartered in Redditch, England. It is a long-running business known for many decades as Guest, Keen and Nettlefolds. It can trace its origins back to 1759 an ...

, owners of the Dowlais Ironworks

The Dowlais Ironworks was a major ironworks and steelworks located at Dowlais near Merthyr Tydfil, in Wales. Founded in the 18th century, it operated until the end of the 20th, at one time in the 19th century being the largest steel producer in ...

in Merthyr, to build a new steelworks

A steel mill or steelworks is an industrial plant for the manufacture of steel. It may be an integrated steel works carrying out all steps of steelmaking from smelting iron ore to rolled product, but may also be a plant where steel semi-fini ...

close to the docks at East Moors in 1890. The metalworks at nearby Port Talbot

Port Talbot (, ) is a town and community in the county borough of Neath Port Talbot, Wales, situated on the east side of Swansea Bay, approximately from Swansea. The Port Talbot Steelworks covers a large area of land which dominates the south ...

also helped developed the industrial base of Glamorgan

, HQ = Cardiff

, Government = Glamorgan County Council (1889–1974)

, Origin=

, Code = GLA

, CodeName = Chapman code

, Replace =

* West Glamorgan

* Mid Glamorgan

* South Glamorgan

, Motto ...

.

City and capital city status

King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria a ...

granted Cardiff city status City status is a symbolic and legal designation given by a national or subnational government. A municipality may receive city status because it already has the qualities of a city, or because it has some special purpose.

Historically, city status ...

on 28 October 1905, and the city acquired a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

Cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the '' cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denomination ...

in 1916.The ancient Llandaff Cathedral

Llandaff Cathedral ( cy, Eglwys Gadeiriol Llandaf) is an Anglican cathedral and parish church in Llandaff, Cardiff, Wales. It is the seat of the Bishop of Llandaff, head of the Church in Wales Diocese of Llandaff. It is dedicated to Saint Peter ...

was outside the city boundaries until 1922 In subsequent years an increasing number of national institutions were located in the city, including the National Museum of Wales

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ce ...

, Welsh national war memorial

A war memorial is a building, monument, statue, or other edifice to celebrate a war or victory, or (predominating in modern times) to commemorate those who died or were injured in a war.

Symbolism

Historical usage

It has ...

, and the University of Wales

The University of Wales (Welsh language, Welsh: ''Prifysgol Cymru'') is a confederal university based in Cardiff, Wales. Founded by royal charter in 1893 as a federal university with three constituent colleges – Aberystwyth, Bangor and Cardiff � ...

registry – although it was denied the National Library of Wales

The National Library of Wales ( cy, Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru), Aberystwyth, is the national legal deposit library of Wales and is one of the Welsh Government sponsored bodies. It is the biggest library in Wales, holding over 6.5 million boo ...

, partly because the library's founder, Sir John Williams, considered Cardiff to have "a non-Welsh population".Encyclopedia of Wales

After a brief post-war boom, Cardiff docks entered a prolonged decline in the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

. By 1936, their trade was less than half its value in 1913, reflecting the slump in demand for Welsh coal. Bomb damage during the Cardiff Blitz

The Cardiff Blitz ( cy, Blitz Caerdydd); refers to the bombing of Cardiff, Wales during World War II. Between 1940 and the final raid on the city in March 1944 approximately 2,100 bombs fell, killing 355 people.

Cardiff Docks became a Strateg ...

in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

included the devastation of Llandaff Cathedral

Llandaff Cathedral ( cy, Eglwys Gadeiriol Llandaf) is an Anglican cathedral and parish church in Llandaff, Cardiff, Wales. It is the seat of the Bishop of Llandaff, head of the Church in Wales Diocese of Llandaff. It is dedicated to Saint Peter ...

, and in the immediate postwar years the city's link with the Bute family came to an end.

The city was proclaimed capital city of Wales on 20 December 1955, by a written reply by the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

Gwilym Lloyd George

Gwilym Lloyd George, 1st Viscount Tenby, (4 December 1894 – 14 February 1967) was a Welsh politician and cabinet minister. The younger son of David Lloyd George, he served as Home Secretary from 1954 to 1957.

Background, education and milit ...

. Caernarfon

Caernarfon (; ) is a royal town, community and port in Gwynedd, Wales, with a population of 9,852 (with Caeathro). It lies along the A487 road, on the eastern shore of the Menai Strait, opposite the Isle of Anglesey. The city of Bangor is ...

had also vied for this title. Cardiff therefore celebrated two important anniversaries

An anniversary is the date on which an event took place or an institution was founded in a previous year, and may also refer to the commemoration or celebration of that event. The word was first used for Catholic feasts to commemorate saints. ...

in 2005. The Encyclopedia of Wales notes that the decision to recognise the city as the capital of Wales "had more to do with the fact that it contained marginal Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

constituencies than any reasoned view of what functions a Welsh capital should have". Although the city hosted the Commonwealth Games

The Commonwealth Games, often referred to as the Friendly Games or simply the Comm Games, are a quadrennial international multi-sport event among athletes from the Commonwealth of Nations. The event was first held in 1930, and, with the exce ...

in 1958, Cardiff only became a centre of national administration with the establishment of the Welsh Office in 1964, which later prompted the creation of various other public bodies such as the Arts Council of Wales and the Welsh Development Agency, most of which were headquartered in Cardiff.

The East Moors Steelworks closed in 1978 and Cardiff lost population during the 1980s, consistent with a wider pattern of counter urbanisation in Britain. However, it recovered and was one of the few cities (outside London) where population grew during the 1990s. During this period the Cardiff Bay Development Corporation was promoting the Urban renewal, redevelopment of south Cardiff; an evaluation of the regeneration of Cardiff Bay published in 2004 concluded that the project had "reinforced the competitive position of Cardiff" and "contributed to a massive improvement in the quality of the built environment", although it had failed "to attract the major inward investors originally anticipated".

In the 1997 Welsh devolution referendum, 1997 devolution referendum, Cardiff voters rejected the establishment of the National Assembly for Wales by 55.4% to 44.2% on a 47% turnout, which Denis Balsom partly ascribed to a general preference in Cardiff and some other parts of Wales for a British people, 'British' rather than exclusively Welsh people, 'Welsh' Nation, identity. The relative lack of support for the Assembly locally, and difficulties between the Welsh Office and Cardiff Council in acquiring the original preferred venue, City Hall, Cardiff, Cardiff City Hall, encouraged other local authorities to bid to house the Assembly. However, the Assembly eventually located at Crickhowell House in Cardiff Bay in 1999; in 2005, a new Senedd building, debating chamber on an adjacent site, designed by Richard Rogers, was opened.

The city was county town

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, a county town is the most important town or city in a county. It is usually the location of administrative or judicial functions within a county and the place where the county's members of Parliament are elect ...

of Glamorgan

, HQ = Cardiff

, Government = Glamorgan County Council (1889–1974)

, Origin=

, Code = GLA

, CodeName = Chapman code

, Replace =

* West Glamorgan

* Mid Glamorgan

* South Glamorgan

, Motto ...

until the council reorganisation in 1974 paired Cardiff and the now Vale of Glamorgan together as the new county of South Glamorgan. Further local government restructuring in 1996 resulted in Cardiff city's Districts of Wales, district council becoming a unitary authority, the Cardiff Council, City and County of Cardiff, with the addition of Creigiau

Creigiau is a dormitory settlement in the north-west of Cardiff, the capital of Wales. The village currently has about 1,500 houses and a population of approximately 5,000 people. The Cardiff electoral ward is called Creigiau/St. Fagans. The ...

and Pentyrch.

On 1 March 2004, Cardiff was granted Fairtrade Town, Fairtrade City status.

See also

* History of Wales * Timeline of Cardiff history * Tiger BayNotes

References

External links

Cardiff's Medieval Town Defences

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Cardiff History of Cardiff,