history of anatomy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of anatomy extends from the earliest examinations of

The history of anatomy extends from the earliest examinations of

The study of

The study of

The final major anatomist of ancient times was

The final major anatomist of ancient times was

File:Woodcut of anatomical dissection. Wellcome M0011499.jpg, A woodcut of an anatomical dissection, from 1493

File:An anatomical dissection being carried out by Andreas Vesali Wellcome V0010413.jpg, An anatomical dissection being carried out by Andreas Vesalius, 1543

Image:Rembrandt - The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp.jpg, ''

In the late 16th century, anatomists began exploring and pushing for contention that the study of anatomy could contribute to advancing the boundaries of natural philosophy. However, the majority of students were more interested in the practicality of anatomy, and less so in the advancement of knowledge of the subject. Students were interested in the technique of dissection rather than the philosophy of anatomy, and this was reflected in their criticism of Professors such as Girolamo Fabrici.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the use of dissecting human cadavers influenced anatomy, leading to a spike in the study of anatomy. The advent of the printing press facilitated the exchange of ideas. Because the study of anatomy concerned observation and drawings, the popularity of the anatomist was equal to the quality of his drawing talents, and one need not be an expert in Latin to take part. Many famous artists studied anatomy, attended dissections, and published drawings for money, from

At the beginning of the 17th century, the use of dissecting human cadavers influenced anatomy, leading to a spike in the study of anatomy. The advent of the printing press facilitated the exchange of ideas. Because the study of anatomy concerned observation and drawings, the popularity of the anatomist was equal to the quality of his drawing talents, and one need not be an expert in Latin to take part. Many famous artists studied anatomy, attended dissections, and published drawings for money, from

Historical Anatomies on the Web. National Library of Medicine.

Selected images from notable anatomical atlases.

Anatomia 1522-1867: Anatomical Plates from the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

Human Anatomy & Physiology Society

A society to promote communication among teachers of human anatomy and physiology in colleges, universities, and related institutions. {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Anatomy Anatomy, history of

The history of anatomy extends from the earliest examinations of

The history of anatomy extends from the earliest examinations of sacrificial

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exis ...

victims to the sophisticated analyses of the body performed by modern anatomists and scientists. Written descriptions of human organs and parts can be traced back thousands of years to ancient Egyptian papyri

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

, where attention to the body was necessitated by their highly elaborate burial practices.

Theoretical considerations of the structure and function of the human body did not develop until far later, in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

. Ancient Greek philosophers, like Alcmaeon and Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the fo ...

, and ancient Greek doctors, like Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of ...

and his school, paid attention to the causes of life, disease, and different functions of the body. Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

advocated dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause o ...

of animals as part of his program for understanding the causes Causes, or causality, is the relationship between one event and another. It may also refer to:

* Causes (band), an indie band based in the Netherlands

* Causes (company)

Causes.com is a civic-technology app and website that enables users to orga ...

of biological forms

Form is the shape, visual appearance, or configuration of an object. In a wider sense, the form is the way something happens.

Form also refers to:

*Form (document), a document (printed or electronic) with spaces in which to write or enter data

* ...

. During the Hellenistic Age

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 31 ...

, dissection and vivesection of human beings took place for the first time in the work of Herophilos

Herophilos (; grc-gre, Ἡρόφιλος; 335–280 BC), sometimes Latinised Herophilus, was a Greek physician regarded as one of the earliest anatomists. Born in Chalcedon, he spent the majority of his life in Alexandria. He was the first sci ...

and Erasistratus

Erasistratus (; grc-gre, Ἐρασίστρατος; c. 304 – c. 250 BC) was a Greek anatomist and royal physician under Seleucus I Nicator of Syria. Along with fellow physician Herophilus, he founded a school of anatomy in Alexandria, where the ...

. Anatomical knowledge in antiquity would reach its apex in the person of Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one of ...

, who made important discoveries through his medical practice and his dissections of monkeys

Monkey is a common name that may refer to most mammals of the infraorder Simiiformes, also known as the simians. Traditionally, all animals in the group now known as simians are counted as monkeys except the apes, which constitutes an incomple ...

, oxen, and other animals.

The development of the study of anatomy gradually built upon concepts that were present in Galen's work, which was a part of the traditional medical curriculum in the Middle Ages. The Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

brought a reconsideration of classical medical texts, and anatomical dissections became once again fashionable for the first time since Galen. Important anatomical work was carried out by Mondino de Luzzi

Mondino de Luzzi, or de Liuzzi or de Lucci,The family name is spelled variously: Liucci, Lucci, Luzzi or Luzzo (Latin: de Luciis, de Liuccis, de Leuciis); the ''dei'' may be contracted to ''de'' or ''de''. SeeGiorgi, P.P. (2004) "Mondino de' Li ...

, Berengario da Carpi

Jacopo Berengario da Carpi (also known as Jacobus Berengarius Carpensis, Jacopo Barigazzi, Giacomo Berengario da Carpi or simply Carpus; c. 1460 – c. 1530) was an Italian physician. His book "''Isagoge breves''" published in 1522 made him the mo ...

, and Jacques Dubois

Jacques Dubois ( Latinised as Jacobus Sylvius; 1478 – 14 January 1555) was a French anatomist. Dubois was the first to describe venous valves, although their function was later discovered by William Harvey. He was the brother of Franciscus Sy ...

, culminating in Andreas Vesalius

Andreas Vesalius (Latinized from Andries van Wezel) () was a 16th-century anatomist, physician, and author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' '' ...

's seminal work ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica

''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (Latin, lit. "On the fabric of the human body in seven books") is a set of books on human anatomy written by Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) and published in 1543. It was a major advance in the history ...

'' (1543). An understanding of the structures

A structure is an arrangement and organization of interrelated elements in a material object or system, or the object or system so organized. Material structures include man-made objects such as buildings and machines and natural objects such as ...

and functions of organs in the body has been an integral part of medical practice

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care practic ...

and a source for scientific investigations ever since.

Ancient Anatomy

Egypt

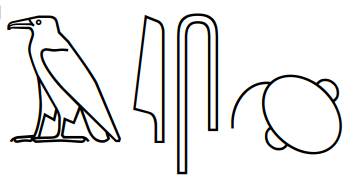

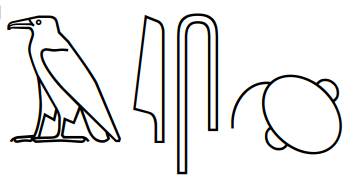

The study of

The study of anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

begins at least as early as 1600 BC, the date of the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is an ancient Egyptian medical manual, medical text, named after Edwin Smith (Egyptologist), Edwin Smith who bought it in 1862, and the oldest known surgical treatise on trauma (medicine), trauma. From a cited quotation in ...

. This treatise shows that the heart

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide t ...

, its vessels, liver

The liver is a major Organ (anatomy), organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for ...

, spleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

, kidneys

The kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped organs found in vertebrates. They are located on the left and right in the retroperitoneal space, and in adult humans are about in length. They receive blood from the paired renal arteries; blood ...

, hypothalamus

The hypothalamus () is a part of the brain that contains a number of small nuclei with a variety of functions. One of the most important functions is to link the nervous system to the endocrine system via the pituitary gland. The hypothalamu ...

, uterus

The uterus (from Latin ''uterus'', plural ''uteri'') or womb () is the organ in the reproductive system of most female mammals, including humans that accommodates the embryonic and fetal development of one or more embryos until birth. The uter ...

and bladder

The urinary bladder, or simply bladder, is a hollow organ in humans and other vertebrates that stores urine from the kidneys before disposal by urination. In humans the bladder is a distensible organ that sits on the pelvic floor. Urine enters ...

were recognized, and that the blood vessel

The blood vessels are the components of the circulatory system that transport blood throughout the human body. These vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to the tissues of the body. They also take waste and carbon dioxide away ...

s were known to emanate from the heart. Other vessels are described, some carrying air, some mucus

Mucus ( ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It is ...

, and two to the right ear

An ear is the organ that enables hearing and, in mammals, body balance using the vestibular system. In mammals, the ear is usually described as having three parts—the outer ear, the middle ear and the inner ear. The outer ear consists of ...

are said to carry the "breath of life", while two to the left ear the "breath of death".The Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BC) features a treatise on the heart. It notes that the heart is the center of blood supply, and attached to it are vessels for every member of the body. The Egyptians seem to have known little about the function of the kidneys and the brain and made the heart the meeting point of a number of vessels which carried all the fluids of the body – blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the c ...

, tears

Tears are a clear liquid secreted by the lacrimal glands (tear gland) found in the eyes of all land mammals. Tears are made up of water, electrolytes, proteins, lipids, and mucins that form layers on the surface of eyes. The different types of ...

, urine

Urine is a liquid by-product of metabolism in humans and in many other animals. Urine flows from the kidneys through the ureters to the urinary bladder. Urination results in urine being excretion, excreted from the body through the urethra.

Cel ...

and semen

Semen, also known as seminal fluid, is an organic bodily fluid created to contain spermatozoa. It is secreted by the gonads (sexual glands) and other sexual organs of male or hermaphroditic animals and can fertilize the female ovum. Semen i ...

. However, they did not have a theory as to where saliva

Saliva (commonly referred to as spit) is an extracellular fluid produced and secreted by salivary glands in the mouth. In humans, saliva is around 99% water, plus electrolytes, mucus, white blood cells, epithelial cells (from which DNA can be ...

and sweat came from.

Ancient Greece

Much of the nomenclature, methods, and applications for the study of anatomy can be traced back to the works of the ancient Greeks. In the fifth-century BCE, the philosopher Alcmaeon may have been one of the first to have dissected animals for anatomical purposes, and possibly identified the optic nerves andEustachian tube

In anatomy, the Eustachian tube, also known as the auditory tube or pharyngotympanic tube, is a tube that links the nasopharynx to the middle ear, of which it is also a part. In adult humans, the Eustachian tube is approximately long and in d ...

s. Ancient physicians such as Acron

Acron ( grc-gre, Ἄκρων), son of Xenon, was a Medicine in ancient Greece, Greek physician born at Agrigentum (Gk. Acragas).

Life

The exact dates of Acron is not known; but, as he is mentioned as being contemporary with Empedocles, who died ...

, Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

*Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of t ...

, and Philistion of Locri

Philistion of Locri ( el, Φιλιστίων) was a Greek physician, medical and dietary author who lived in the 4th century BC.

He was a native of Locri in Italy, but was also referred to as "the Sicilian." He was tutor to the physician Chrysippu ...

may had also conducted anatomical investigations. Another important philosopher at the time was Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the fo ...

, who viewed blood as the ''innate heat'' and argued that the heart was the chief organ of the body and the source of ''pneuma

''Pneuma'' () is an ancient Greek word for "breath", and in a religious context for "spirit" or "soul". It has various technical meanings for medical writers and philosophers of classical antiquity, particularly in regard to physiology, and is a ...

'' (this could refer to either breath or soul), which was distributed by the blood vessels.

Many medical texts by various authors are collected in the ''Hippocratic Corpus

The Hippocratic Corpus (Latin: ''Corpus Hippocraticum''), or Hippocratic Collection, is a collection of around 60 early Ancient Greek medical works strongly associated with the physician Hippocrates and his teachings. The Hippocratic Corpus cove ...

'', none of which can definitely be ascribed to Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of ...

himself. The texts show an understanding of musculoskeletal

The human musculoskeletal system (also known as the human locomotor system, and previously the activity system) is an organ system that gives humans the ability to move using their muscular and skeletal systems. The musculoskeletal system prov ...

structure, and the beginnings of understanding of the function of certain organs, such as the kidneys. The tricuspid valve

The tricuspid valve, or right atrioventricular valve, is on the right dorsal side of the mammalian heart, at the superior portion of the right ventricle. The function of the valve is to allow blood to flow from the right atrium to the right vent ...

of the heart

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide t ...

and its function is documented in the treatise ''On the Heart''.

The philosopher Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

(4th century BCE), alongside some of his contemporaries, labored to produce a system that made room for empirical research. Through his work with animal dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause o ...

s and biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

, Aristotle engaged in comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

. Around this time, Praxagoras

Praxagoras ( grc, Πραξαγόρας ὁ Κῷος) was a figure of medicine in ancient Greece. He was born on the Greek island of Kos in about 340 BC. Both his father, Nicarchus, and his grandfather were physicians. Very little is known of ...

may have been the first to identify the difference between arteries

An artery (plural arteries) () is a blood vessel in humans and most animals that takes blood away from the heart to one or more parts of the body (tissues, lungs, brain etc.). Most arteries carry oxygenated blood; the two exceptions are the pul ...

and vein

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated b ...

s, with more accurate descriptions of organs than in previous works.

In the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 3 ...

, the first recorded school of anatomy was formed in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

from the late fourth century to the second century BCE. Beginning with Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter (; gr, Πτολεμαῖος Σωτήρ, ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'' "Ptolemy the Savior"; c. 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian and companion of Alexander the Great from the Kingdom of Macedon ...

, medical officials were allowed to cut open and examine cadaver

A cadaver or corpse is a dead human body that is used by medical students, physicians and other scientists to study anatomy, identify disease sites, determine causes of death, and provide tissue to repair a defect in a living human being. Stud ...

s for the purposes of learning how human bodies operated. The first use of human bodies for anatomical research occurred in the work of Herophilos

Herophilos (; grc-gre, Ἡρόφιλος; 335–280 BC), sometimes Latinised Herophilus, was a Greek physician regarded as one of the earliest anatomists. Born in Chalcedon, he spent the majority of his life in Alexandria. He was the first sci ...

and Erasistratus

Erasistratus (; grc-gre, Ἐρασίστρατος; c. 304 – c. 250 BC) was a Greek anatomist and royal physician under Seleucus I Nicator of Syria. Along with fellow physician Herophilus, he founded a school of anatomy in Alexandria, where the ...

, who gained permission to perform live dissections, or vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for experiment ...

, on condemned criminals in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

under the auspices of the Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty (; grc, Πτολεμαῖοι, ''Ptolemaioi''), sometimes referred to as the Lagid dynasty (Λαγίδαι, ''Lagidae;'' after Ptolemy I's father, Lagus), was a Macedonian Greek royal dynasty which ruled the Ptolemaic ...

. Herophilos in particular developed a body of anatomical knowledge much more informed by the actual structure of the human body than previous works had been. He also reversed the longstanding notion made by Aristotle that the heart was the "seat of intelligence", arguing for the brain instead. He also wrote on the distinction between veins and arteries, and made many other accurate observations about the structure of the human body, especially the nervous system.

Galen

The final major anatomist of ancient times was

The final major anatomist of ancient times was Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one of ...

, active in the second century CE. He was born in the ancient Greek city of Pergamon

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; grc-gre, Πέργαμον), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greece, ancient Greek city in Mysia. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a ...

(now in Turkey), the son of a successful architect who gave him a liberal education. Galen was instructed in all major philosophical schools (Platonism, Aristotelianism, Stoicism and Epicureanism) until his father, moved by a dream of Asclepius

Asclepius (; grc-gre, Ἀσκληπιός ''Asklēpiós'' ; la, Aesculapius) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Religion in ancient Greece, Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis (lover of ...

, decided he should study medicine. After his father's death, Galen traveled widely searching for the best doctors in Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

, Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part o ...

, and finally Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

.

Galen compiled much of the knowledge obtained by his predecessors, and furthered the inquiry into the function of organs by performing dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause o ...

s and vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for experiment ...

s on Barbary apes, oxen, pig

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), often called swine, hog, or domestic pig when distinguishing from other members of the genus '' Sus'', is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is variously considered a subspecies of ''Sus ...

s, and other animals. Due to a lack of readily available human specimens, discoveries through animal dissection were broadly applied to human anatomy as well. In 158 CE, Galen served as chief physician to the gladiators in his native Pergamon

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; grc-gre, Πέργαμον), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greece, ancient Greek city in Mysia. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a ...

. Through his position with the gladiators, Galen was able to study all kinds of wounds without performing any actual human dissection. Galen was able to view much of the abdominal cavity. His study on pigs and apes, however, gave him more detailed information about the organs and provided the basis for his medical works. Around 100 of these works survive—the most for any ancient Greek author—and fill 22 volumes of modern text.

Anatomy was a prominent part of Galen's medical education and was a major source of interest throughout his life. He wrote two great anatomical works, ''On anatomical procedure'' and ''On the uses of the parts of the body of man''. The information in these tracts became the foundation of authority for all medical writers and physicians for the next 1300 years until they were challenged by Vesalius

Andreas Vesalius (Latinized from Andries van Wezel) () was a 16th-century anatomist, physician, and author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' '' ...

and Harvey

Harvey, Harveys or Harvey's may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Harvey'' (play), a 1944 play by Mary Chase about a man befriended by an invisible anthropomorphic rabbit

* Harvey Awards ("Harveys"), one of the most important awards ...

in the 16th century.

It was through his experiments that Galen was able to overturn many long-held beliefs, such as the theory that the arteries contained air which carried it to all parts of the body from the heart and the lungs. This belief was based originally on the arteries of dead animals, which appeared to be empty. Galen was able to demonstrate that living arteries contain blood, but his error, which became the established medical orthodoxy for centuries, was to assume that the blood goes back and forth from the heart in an ebb-and-flow motion. Galen also made the mistake of assuming that the circulatory system was entirely open-ended. Galen believed that all blood was absorbed by the body and had to be regenerated via the liver using food and water. Galen viewed the cardiovascular system as a machine in which blood acts as fuel rather than a system that constantly recirculates.

Although Galen correctly identified some of the organs involved in the vascular system, many of their functions were not correctly established. Galen believed that the liver played a vital role in the circulatory system by creating all nutritious blood in the body. The heart, according to Galen, kept the body warm and mixed the two types of blood via pores in the wall of the heart that separates the left and right ventricles. Galen proposed that the heart's warmth allowed the lungs to expand and inhale air. In contrast, Galen viewed the lungs as a cooling region in the body that also worked to expel sooty waste products from the lungs as they contract. In addition, Galen believed that the lungs kept the heart functioning properly by reducing the amount of blood in the right atrium, for if the right atrium contains too much blood, the pores in the heart do not dilate properly.

Medieval to Early Modern Anatomy

Throughout the Middle Ages, human anatomy was mainly learned through books and animal dissection. While it was claimed by 19th century polemicists that dissection became restricted afterBoniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII ( la, Bonifatius PP. VIII; born Benedetto Caetani, c. 1230 – 11 October 1303) was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 to his death in 1303. The Caetani family was of baronial ...

passed a papal bull that forbade the dismemberment and boiling of corpses for funerary purposes and this is still repeated in some generalist works, this claim has been debunked as a myth by modern historians of science.

For many decades human dissection was thought unnecessary when all the knowledge about a human body could be read about from early authors such as Galen. In the 12th century, as universities were being established in Italy, Emperor Frederick II made it mandatory for students of medicine to take courses on human anatomy and surgery. Students who had the opportunity to watch Vesalius in dissection at times had the opportunity to interact with the animal corpse. At the risk of letting their eagerness to participate become a distraction to their professors, medical students preferred this interactive teaching style at the time. In the universities the lectern would sit elevated before the audience and instruct someone else in the dissection of the body, but in his early years Mondino de Luzzi performed the dissection himself making him one of the first and few to use a hands on approach to teaching human anatomy. Specifically in 1315, Mondino de' Liuzzi is credited with having "performed the first human dissection recorded for Western Europe."

Mondino de Luzzi

Mondino de Luzzi, or de Liuzzi or de Lucci,The family name is spelled variously: Liucci, Lucci, Luzzi or Luzzo (Latin: de Luciis, de Liuccis, de Leuciis); the ''dei'' may be contracted to ''de'' or ''de''. SeeGiorgi, P.P. (2004) "Mondino de' Li ...

"Mundinus" was born around 1276 and died in 1326; from 1314 to 1324 he presented many lectures on human anatomy at Bologna university. Mondino de'Luzzi put together a book called "Anathomia" in 1316 that consisted of detailed dissections that he had performed, this book was used as a text book in universities for 250 years. "Mundinus" carried out the first systematic human dissections since Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Ceos 1500 years earlier. The first major development in anatomy in Christian Europe since the fall of Rome occurred at Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label= Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nat ...

, where anatomists dissected cadavers and contributed to the accurate description of organs and the identification of their functions. Following de Liuzzi's early studies, 15th century anatomists included Alessandro Achillini

Alessandro Achillini (''Latin'' Alexander Achillinus; 20 or 29 October 1463 (or possibly 1461)2 August 1512) was an Italian philosopher and physician. He is known for the anatomic studies that he was able to publish, made possible by a 13th-cent ...

and Antonio Benivieni.

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

(1452–1519) was trained in anatomy by Andrea del Verrocchio

Andrea del Verrocchio (, , ; – 1488), born Andrea di Michele di Francesco de' Cioni, was a sculptor, Italian painter and goldsmith who was a master of an important workshop in Florence. He apparently became known as ''Verrocchio'' after the su ...

. In 1489 Leonardo began a series of anatomical drawings depicting the ideal human form. This work was carried out intermittently for over two decades. During this time he made use of his anatomical knowledge in his artwork, making many sketches of skeletal structures, muscles, and organs of humans and other vertebrates that he dissected. (First published by Collins, 1962)

Initially adopting an Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

an understanding of anatomy, he later studied Galen and adopted a more empirical approach, eventually abandoning Galen altogether and relying entirely on his own direct observation. His surviving 750 drawings represent groundbreaking studies in anatomy. Leonardo dissected around thirty human specimens until he was forced to stop under order of Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political an ...

.

As an artist-anatomist, Leonardo made many important discoveries, and had intended to publish a comprehensive treatise on human anatomy. For instance, he produced the first accurate depiction of the human spine, while his notes documenting his dissection of the Florentine centenarian

A centenarian is a person who has reached the age of 100 years. Because life expectancies worldwide are below 100 years, the term is invariably associated with longevity. In 2012, the United Nations estimated that there were 316,600 living cente ...

contain the earliest known description of cirrhosis of the liver

Cirrhosis, also known as liver cirrhosis or hepatic cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease, is the impaired liver function caused by the formation of scar tissue known as fibrosis due to damage caused by liver disease. Damage causes tissue repai ...

and arteriosclerosis

Arteriosclerosis is the thickening, hardening, and loss of elasticity of the walls of Artery, arteries. This process gradually restricts the blood flow to one's organs and tissues and can lead to severe health risks brought on by atherosclerosis ...

. He was the first to develop drawing techniques in anatomy to convey information using cross-sections and multiple angles, although centuries would pass before anatomical drawings became accepted as crucial for learning anatomy.

None of Leonardo's Notebooks were published during his lifetime, many being lost after his death, with the result that his anatomical discoveries remained unknown until they were later found and published centuries after his death.

Vesalius

The Galenic doctrine in Europe was first seriously challenged in the 16th century. Thanks to theprinting press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in wh ...

, all over Europe a collective effort proceeded to circulate the works of Galen and later publish criticisms on their works. Andreas Vesalius

Andreas Vesalius (Latinized from Andries van Wezel) () was a 16th-century anatomist, physician, and author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' '' ...

, born and educated in Belgium, contributed the most to human anatomy. Vesalius's success were due in large part to him exercising the skills of mindful dissections for the sake of understanding anatomy, much to the tune of Galen's "anatomy project" instead of focusing on the work of other scholars of the time in recovering the ancient texts of Hippocrates, Galen and others (which much of the medical community was focused around at the time).

Vesalius was the first to publish a treatise, ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica

''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (Latin, lit. "On the fabric of the human body in seven books") is a set of books on human anatomy written by Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) and published in 1543. It was a major advance in the history ...

'', that challenged Galen's anatomical teachings, arguing that they are based on observations of other mammals, not human bodies. The book included a detailed series of explanations and vivid drawings of the anatomical parts of human bodies. Vesalius traveled all the way from Leuven

Leuven (, ) or Louvain (, , ; german: link=no, Löwen ) is the capital and largest city of the province of Flemish Brabant in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is located about east of Brussels. The municipality itself comprises the historic ...

to Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

for permission to dissect victims from the gallows

A gallows (or scaffold) is a frame or elevated beam, typically wooden, from which objects can be suspended (i.e., hung) or "weighed". Gallows were thus widely used to suspend public weighing scales for large and heavy objects such as sacks ...

without fear of persecution. His superbly executed drawings are triumphant descriptions of the differences between dogs and humans, but it took a century for Galen's influence to fade.

Vesalius' work marked a new era in the study of anatomy and its relation to medicine. Under Vesalius, anatomy became an actual discipline. "His skill in and attention to dissection featured prominently in his publications as well as his demonstrations, in his research as well as his teaching."

In 1540, Vesalius gave a public demonstration of the inaccuracies of Galen's anatomical theories, which are still the orthodoxy of the medical profession. Vesalius now has on display, for comparison purposes, the skeletons of a human being alongside that of an ape of which he was able to show, that in many cases, Galen's observations were indeed correct for the ape, but bear little relation to man. Clearly what was needed was a new account of human anatomy. While the lecturer explained human anatomy, as revealed by Galen more than 1000 years earlier, an assistant pointed to the equivalent details on a dissected corpse. At times, the assistant was unable to find the organ as described, but invariably the corpse rather than Galen was held to be in error. Vesalius then decided that he will dissect corpses himself and trust to the evidence of what he found. His approach was highly controversial, but his evident skill led to his appointment as professor of surgery and anatomy at the University of Padua.

A succession of researchers proceeded to refine the body of anatomical knowledge, giving their names to a number of anatomical structures along the way. The 16th and 17th centuries also witnessed significant advances in the understanding of the circulatory system

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

, as the purpose of valve

A valve is a device or natural object that regulates, directs or controls the flow of a fluid (gases, liquids, fluidized solids, or slurries) by opening, closing, or partially obstructing various passageways. Valves are technically fittings ...

s in veins was identified, the left-to-right ventricle flow of blood through the circulatory system was described, and the hepatic vein

In human anatomy, the hepatic veins are the veins that drain venous blood from the liver into the inferior vena cava (as opposed to the hepatic portal vein which conveys blood from the gastrointestinal organs to the liver). There are usually thr ...

s were identified as a separate portion of the circulatory system. The lymphatic system

The lymphatic system, or lymphoid system, is an organ system in vertebrates that is part of the immune system, and complementary to the circulatory system. It consists of a large network of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, lymphatic or lymphoid o ...

was also identified as a separate system at this time.

Anatomical theatres

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

''The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp'' is a 1632 oil painting on canvas by Rembrandt housed in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague, the Netherlands. The painting is regarded as one of Rembrandt's early masterpieces.

In the work, Nicolaes Tu ...

'', by Rembrandt

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (, ; 15 July 1606 – 4 October 1669), usually simply known as Rembrandt, was a Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker and draughtsman. An innovative and prolific master in three media, he is generally consid ...

, 1632

File:Dr_Deijman’s_Anatomy_Lesson_(fragment),_by_Rembrandt.jpg, ''The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Deijman

''The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Deijman'' (alternative spelling Deyman) is a 1656 fragmentary painting by Rembrandt, now in Amsterdam Museum. It is a group portrait showing a brain dissection by Dr. Jan Deijman (16191666). Much of the canvas was dest ...

'' by Rembrandt

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (, ; 15 July 1606 – 4 October 1669), usually simply known as Rembrandt, was a Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker and draughtsman. An innovative and prolific master in three media, he is generally consid ...

, 1656

File:Rembrandt van Rijn 193.jpg, Sketch of the Preceding painting ''The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Deijman''

File:A depiction of an anatomical theatre.jpeg, An Anatomical Theatre In Leiden, 1616

Image:cruelty4.JPG, ''The reward of cruelty'' (Plate IV) by William Hogarth 1751

Anatomical theatre

An anatomical theatre (Latin: ) was a specialised building or room, resembling a theatre, used in teaching anatomy at early modern universities. They were typically constructed with a tiered structure surrounding a central table, allowing a lar ...

s became a popular form for anatomical teaching in the early 16th century. The University of Padua

The University of Padua ( it, Università degli Studi di Padova, UNIPD) is an Italian university located in the city of Padua, region of Veneto, northern Italy. The University of Padua was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from B ...

was the first and most widely known theatre, founded in 1594. As a result, Italy became the centre for human dissection. People came from all over to watch as professors taught lectures on the human physiology

The human body is the structure of a human being. It is composed of many different types of cells that together create tissues and subsequently organ systems. They ensure homeostasis and the viability of the human body.

It comprises a head ...

and anatomy, as anyone was welcome to witness the spectacle. Participants "were fascinated by corporeal display, by the body undergoing dissection". Most professors did not do the dissections themselves. Instead, they sat in seats above the bodies while hired hands did the cutting. Students and observers would be placed around the table in a circular, stadium-like arena and listen as professors explained the various anatomical parts. As anatomy theatres gained popularity throughout the 16th century, protocols were adjusted to account for the disruptions of students. Students moved beyond simply being eager to participate, and began stealing and vandalizing cadavers. Students were thus instructed to sit quietly and were to be penalized for disrupting the dissection. Moreover, preparatory lectures were mandatory in order to introduce the "subsequent observation of anatomy". The demonstrations were structured into dissections and lectures. The dissections focused on the skill of autopsy/vivisection while the lectures would center on the philosophical questions of anatomy. This is exemplary of how anatomy was viewed not only as the study of structures but also the study of the "body as an extension of the soul". The 19th century eventually saw a move from anatomical theatres to classrooms, reducing "the number of people who could benefit from each cadaver".

17th century

At the beginning of the 17th century, the use of dissecting human cadavers influenced anatomy, leading to a spike in the study of anatomy. The advent of the printing press facilitated the exchange of ideas. Because the study of anatomy concerned observation and drawings, the popularity of the anatomist was equal to the quality of his drawing talents, and one need not be an expert in Latin to take part. Many famous artists studied anatomy, attended dissections, and published drawings for money, from

At the beginning of the 17th century, the use of dissecting human cadavers influenced anatomy, leading to a spike in the study of anatomy. The advent of the printing press facilitated the exchange of ideas. Because the study of anatomy concerned observation and drawings, the popularity of the anatomist was equal to the quality of his drawing talents, and one need not be an expert in Latin to take part. Many famous artists studied anatomy, attended dissections, and published drawings for money, from Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was insp ...

to Rembrandt

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (, ; 15 July 1606 – 4 October 1669), usually simply known as Rembrandt, was a Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker and draughtsman. An innovative and prolific master in three media, he is generally consid ...

. For the first time, prominent universities could teach something about anatomy through drawings, rather than relying on knowledge of Latin. Contrary to popular belief, the Church neither objected to nor obstructed anatomical research.

Only certified anatomists were allowed to perform dissections, and sometimes then only yearly. These dissections were sponsored by the city councilors and often charged an admission fee, rather like a circus act for scholars. Many European cities, such as Amsterdam, London, Copenhagen, Padua, and Paris, all had Royal anatomists (or some such office) tied to local government. Indeed, Nicolaes Tulp

Nicolaes Tulp (9 October 1593 – 12 September 1674) was a Dutch surgeon and mayor of Amsterdam. Tulp was well known for his upstanding moral character and as the subject of Rembrandt's famous painting ''The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp'' ...

was Mayor of Amsterdam for three terms. Though it was a risky business to perform dissections, and unpredictable depending on the availability of fresh bodies, ''attending'' dissections was legal.

The supply of printed anatomy books from Italy and France led to an increased demand for human cadavers for dissections. Since few bodies were voluntarily donated for dissection, royal charters were established which allowed prominent universities to use the bodies of hanged criminals for dissections. However, there was still a shortage of bodies that could not accommodate for the high demand of bodies.

Modern Anatomy

18th century

Until the middle of the 18th century, there was a quota of ten cadavers for each the Royal College of Physicians and the Company of Barber Surgeons, the only two groups permitted to perform dissections. During the first half of the 18th century, William Cheselden challenged the Company of Barber Surgeon's exclusive rights on dissections. He was the first to hold regular anatomy lectures and demonstrations. He also wrote ''The Anatomy of the Humane Body,'' a student handbook of anatomy. In 1752, the rapid growth of medical schools in England and the pressing demand for cadavers led to the passage of the Murder Act. This allowed medical schools in England to legally dissect bodies of executed murderers for anatomical education and research and also aimed to prevent murder. To further increase the supply of cadavers, the government increased the number of crimes in which hanging was a punishment. Although the number of cadavers increased, it was still not enough to meet the demand of anatomical and medical training. Since few bodies were voluntarily donated for dissection, criminals that were hanged for murder were dissected. However, there was a shortage of bodies that could not accommodate the high demand of bodies. To cope with shortages of cadavers and the rise in medical students during the 17th and 18th centuries,body-snatching

Body snatching is the illicit removal of corpses from graves, morgues, and other burial sites. Body snatching is distinct from the act of grave robbery as grave robbing does not explicitly involve the removal of the corpse, but rather theft from ...

and even anatomy murder were practiced to obtain cadavers.Rosner, Lisa. 2010. The Anatomy Murders. Being the True and Spectacular History of Edinburgh's Notorious Burke and Hare and of the Man of Science Who Abetted Them in the Commission of Their Most Heinous Crimes. University of Pennsylvania Press 'Body snatching' was the act of sneaking into a graveyard, digging up a corpse and using it for study. Men known as 'resurrectionists' emerged as outside parties, who would steal corpses for a living and sell the bodies to anatomy schools. The leading London anatomist John Hunter paid for a regular supply of corpses for his anatomy school. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the perception of dissections had evolved into a form of capital punishment. Dissections were considered a dishonor. The corpse was mutilated and not suitable for a funeral. By the end of the 18th century, many European countries had passed legislation similar to the Murder Act in England to meet the demand of fresh cadavers and to reduce crime. Countries allowed institutions to use unclaimed bodies of paupers, prison inmates, and people in psychiatric and charitable hospitals for dissection. Unfortunately, the lack of bodies available for dissection and the controversial air that surrounded anatomy in the late 17th century and early 18th century caused a halt in progress that is evident by the lack of updates made to anatomical texts of the time between editions. Additionally, most of the investigations into anatomy were aimed at developing the knowledge of physiology and surgery. Naturally this meant that a close examination of the more detailed aspects of anatomy that could advance anatomical knowledge was not a priority.

Paris Medicine was notorious for its influence on medical thought and its contributions to medical knowledge. The new hospital medicine in France during the late 18th century was brought about in part by the Law of 1794 which made physicians and surgeons equals in the world of medical care. The law came as a response to the increase demand for medical professionals capable of caring for the increase in injuries and diseases brought about by French Revolution. The law also supplemented schools with bodies for anatomical lessons. Ultimately this created the opportunity for the field of medicine to grow in the direction of "localism of pathological anatomy, the development of appropriate diagnostic techniques, and the numerical approach to disease and therapeutics."

The British Parliament passed the Anatomy Act 1832

The Anatomy Act 1832 (2 & 3 Will. IV c.75) is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom that gave free licence to doctors, teachers of anatomy and bona fide medical students to dissect donated bodies. It was enacted in response to public revu ...

, which finally provided for an adequate and legitimate supply of corpses by allowing legal dissection of executed murderers. The view of anatomist at the time, however, became similar to that of an executioner. Having one's body dissected was seen as a punishment worse than death, "if you stole a pig, you were hung. If you killed a man, you were hung and then dissected." Demand grew so great that some anatomists resorted to dissecting their own family members as well as robbing bodies from their graves.

Many Europeans interested in the study of anatomy traveled to Italy, then the centre of anatomy. Only in Italy could certain important research methods be used, such as dissections on women. Realdo Colombo

Matteo Realdo Colombo (c. 1515 – 1559) was an Italian professor of anatomy and a surgeon at the University of Padua between 1544 and 1559.

Early life and education

Matteo Realdo Colombo or Realdus Columbus, was born in Cremona, Lombardy, the ...

(also known as Realdus Columbus) and Gabriele Falloppio

Gabriele Falloppio (also Gabrielle Falloppia) (1522/23 – 9 October 1562) was an Italian anatomist often known by his Latin name Fallopius. He was one of the most important human anatomy, anatomists and physicians of the sixteenth century, givi ...

were pupils of Vesalius

Andreas Vesalius (Latinized from Andries van Wezel) () was a 16th-century anatomist, physician, and author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' '' ...

. Columbus, as Vesalius's immediate successor in Padua, and afterwards professor at Rome, distinguished himself by describing the shape and cavities of the heart, the structure of the pulmonary artery and aorta and their valves, and tracing the course of the blood from the right to the left side of the heart.

The rise in anatomy lead to various discoveries and findings. In 1628, English physician William Harvey observed circulating blood through dissections of his father's and sister's bodies. He published ''De moto cordis et sanguinis'', a treatise in which he explained his theory. In Tuscany and Florence, Marcello Malpighi founded microscopic anatomy, and Nils Steensen studied the anatomy of lymph nodes and salivary glands. By the end of the 17th century, Gaetano Zumbo developed anatomical wax modeling techniques. Antonio Valsalva, a student of Malpighi and a professor of anatomy at University of Bologna, was one of the greatest anatomists of the time. He is known by many as the founder of anatomy and physiology of the ear. In the 18th century, Giovanni Batista Morgagni related pre-mortem symptoms with post-mortem pathological findings using pathological anatomy in his book ''De Sedibus''. This led to the rise of morbid anatomy in France and Europe. The rise of morbid anatomy was one of the contributing factors to the shift in power between doctors and physicians, giving power to the physicians over patients. With the invention of the Stethoscope in 1816, R.T.H. Laennec was able to help bridge the gap between a symptomatic approach to medicine and disease, to one based on anatomy and physiology. His disease and treatments were based on "pathological anatomy" and because this approach to disease was rooted in anatomy instead of symptoms, the process of evaluation and treatment were also forced to evolve. From the late 18th century to the early 19th century, the work of professionals such as Morgagni, Scott Matthew Baillie, and Xavier Bichat

Marie François Xavier Bichat (; ; 14 November 1771 – 22 July 1802) was a French anatomist and pathologist, known as the father of modern histology. Although he worked without a microscope, Bichat distinguished 21 types of elementary tissues ...

served to demonstrate exactly how the detailed anatomical inspection of organs could lead to a more empirical means of understanding disease and health that would combine medical theory with medical practice. This "pathological anatomy" paved the way for "clinical pathology that applied the knowledge of opening up corpses and quantifying illnesses to treatments." Along with the popularity of anatomy and dissection came an increasing interest in the preservation of dissected specimens. In the 17th century, many of the anatomical specimens were dried and stored in cabinets. In the Netherlands, there were attempts to replicate Egyptian mummies by preserving soft tissue. This became known as Balsaming. In the 1660s the Dutch were also attempting to preserve organs by injecting wax to keep the organ's shape. Dyes and mercury were added to the wax to better differentiate and see various anatomical structures for academic and research anatomy. By the late 18th century, Thomas Pole published ''The Anatomic Instructor'', which detailed how to dry and preserve specimens and soft tissue.

19th century anatomy

During the 19th century, anatomical research was extended withhistology

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of biology which studies the microscopic anatomy of biological tissues. Histology is the microscopic counterpart to gross anatomy, which looks at larger structures vis ...

and developmental biology

Developmental biology is the study of the process by which animals and plants grow and develop. Developmental biology also encompasses the biology of Regeneration (biology), regeneration, asexual reproduction, metamorphosis, and the growth and di ...

of both humans and animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

s. Women, who were not allowed to attend medical school, could attend the anatomy theatres. From 1822 the Royal College of Surgeons forced unregulated schools to close. Medical museums provided examples in comparative anatomy, and were often used in teaching.

Current Research

Anatomical research in the past hundred years has taken advantage of technological developments and growing understanding of sciences such asevolutionary

Evolution is change in the heredity, heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the Gene expression, expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to ...

and molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and physi ...

to create a thorough understanding of the body's organs and structures. Disciplines such as endocrinology

Endocrinology (from '' endocrine'' + '' -ology'') is a branch of biology and medicine dealing with the endocrine system, its diseases, and its specific secretions known as hormones. It is also concerned with the integration of developmental event ...

have explained the purpose of glands that anatomists previously could not explain; medical devices such as MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a medical imaging technique used in radiology to form pictures of the anatomy and the physiological processes of the body. MRI scanners use strong magnetic fields, magnetic field gradients, and radio waves ...

machines and CAT scanners have enabled researchers to study organs, living or dead, in unprecedented detail. Progress today in anatomy is centered in the development, evolution, and function of anatomical features, as the macroscopic aspects of human anatomy have largely been catalogued. Non-human anatomy is particularly active as researchers use techniques ranging from finite element analysis

The finite element method (FEM) is a popular method for numerically solving differential equations arising in engineering and mathematical modeling. Typical problem areas of interest include the traditional fields of structural analysis, heat ...

to molecular biology.

To save time, some medical schools such as Birmingham, England have adopted prosection, where a demonstrator dissects and explains to an audience, in place of dissection by students. This enables students to observe more than one body. Improvements in colour images and photography means that an anatomy text is no longer an aid to dissection but rather a central material to learn from. Plastic anatomical model

An anatomical model is a three-dimensional representation of human or animal anatomy, used for medical and biological education.

Model specs

The model may show the anatomy partially dissected, or have removable parts allowing the student to re ...

s are regularly used in anatomy teaching, offering a good substitute to the real thing. Use of living models for anatomy demonstration is once again becoming popular within teaching of anatomy. Surface landmarks that can be palpated

Palpation is the process of using one's hands to check the body, especially while perceiving/diagnosing a disease or illness. Usually performed by a health care practitioner, it is the process of feeling an object in or on the body to determine ...

on another individual provide practice for future clinical situations. It is possible to do this on oneself; in the Integrated Biology course at the University of Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant univ ...

, students are encouraged to "introspect" on themselves and link what they are being taught to their own body.

In Britain, the Human Tissue Act 2004

The Human Tissue Act 2004 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, that applied to England, Northern Ireland and Wales, which consolidated previous legislation and created the Human Tissue Authority to "regulate the removal, storage, u ...

has tightened up the availability of resources to anatomy departments. The outbreaks of bovine spongiform encephalitis (BSE) in the late 1980s and early 1990s further restricted the handling of brain tissue.

The controversy of Gunther von Hagens

Gunther von Hagens (born Gunther Gerhard Liebchen; 10 January 1945) is a German anatomist who invented the technique for preserving biological tissue specimens called plastination. He has organized numerous ''Body Worlds'' public exhibitions an ...

and public displays of dissections, preserved by plastination

Plastination is a technique or process used in anatomy to preserve bodies or body parts, first developed by Gunther von Hagens in 1977. The water and fat are replaced by certain plastics, yielding specimens that can be touched, do not smell or ...

, may divide opinions on what is ethical or legal.British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) News. 2002 Controversial autopsy goes ahead. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/2493291.stm Accessed 22 April 2008.

References

Bibliography

* * * *External links

Historical Anatomies on the Web. National Library of Medicine.

Selected images from notable anatomical atlases.

Anatomia 1522-1867: Anatomical Plates from the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

Human Anatomy & Physiology Society

A society to promote communication among teachers of human anatomy and physiology in colleges, universities, and related institutions. {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Anatomy Anatomy, history of