heterochrony on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

The concept of heterochrony was introduced by the German zoologist

The concept of heterochrony was introduced by the German zoologist

Heterochrony can be divided into intraspecific and interspecific types.

Intraspecific heterochrony means changes in the rate or timing of development within a species. For example, some individuals of the salamander species ''

Heterochrony can be divided into intraspecific and interspecific types.

Intraspecific heterochrony means changes in the rate or timing of development within a species. For example, some individuals of the salamander species '' *Onset: A developmental process can either begin earlier, ''pre-displacement'', extending its development, or later, ''post-displacement'', truncating it.

*Offset: A process can either end later, ''hypermorphosis'', extending its development, or earlier, ''hypomorphosis'' or ''progenesis'', truncating it.

*Rate: The rate of a process can accelerate, extending its development, or decelerate (as in neoteny), truncating it.

A dramatic illustration of how acceleration can change a

*Onset: A developmental process can either begin earlier, ''pre-displacement'', extending its development, or later, ''post-displacement'', truncating it.

*Offset: A process can either end later, ''hypermorphosis'', extending its development, or earlier, ''hypomorphosis'' or ''progenesis'', truncating it.

*Rate: The rate of a process can accelerate, extending its development, or decelerate (as in neoteny), truncating it.

A dramatic illustration of how acceleration can change a

Paedomorphosis can be the result of

Paedomorphosis can be the result of

Peramorphosis is delayed maturation with extended periods of growth. An example is the extinct

Peramorphosis is delayed maturation with extended periods of growth. An example is the extinct

In

In evolutionary developmental biology

Evolutionary developmental biology (informally, evo-devo) is a field of biological research that compares the developmental processes of different organisms to infer how developmental processes evolved.

The field grew from 19th-century beginni ...

, heterochrony is any genetically controlled difference in the timing, rate, or duration of a developmental process

Developmental biology is the study of the process by which animals and plants grow and develop. Developmental biology also encompasses the biology of regeneration, asexual reproduction, metamorphosis, and the growth and differentiation of stem ...

in an organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

compared to its ancestors or other organisms. This leads to changes in the size, shape, characteristics and even presence of certain organs and features. It is contrasted with heterotopy

Heterotopy is an evolutionary change in the spatial arrangement of an animal's embryonic development, complementary to heterochrony, a change to the rate or timing of a development process. It was first identified by Ernst Haeckel in 1866 and ha ...

, a change in spatial positioning of some process in the embryo, which can also create morphological innovation. Heterochrony can be divided into intraspecific heterochrony, variation within a species, and interspecific heterochrony, phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

variation, i.e. variation of a descendant species with respect to an ancestral species.

These changes all affect the start, end, rate or time span of a particular developmental process. The concept of heterochrony was introduced by Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new sp ...

in 1875 and given its modern sense by Gavin de Beer

Sir Gavin Rylands de Beer (1 November 1899 – 21 June 1972) was a British evolutionary embryologist, known for his work on heterochrony as recorded in his 1930 book ''Embryos and Ancestors''. He was director of the Natural History Museum, Lon ...

in 1930.

History

Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new sp ...

in 1875, where he used it to define deviations from recapitulation theory

The theory of recapitulation, also called the biogenetic law or embryological parallelism—often expressed using Ernst Haeckel's phrase "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny"—is a historical hypothesis that the development of the embryo of an ani ...

, which held that "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the stu ...

". As Stephen Jay Gould

Stephen Jay Gould (; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely read authors of popular science of his generation. Gould sp ...

pointed out, Haeckel's term is now used in a sense contrary to his coinage; Haeckel had assumed that embryonic development

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sperm ...

(ontogeny) of "higher" animals recapitulated their ancestral development (phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

), as when mammal embryos have structures on the neck that resemble fish gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

s at one stage. This, in his view, necessarily compressed the earlier developmental stages, representing the ancestors, into a shorter time, meaning accelerated development. The ideal for Haeckel would be when the development of every part of an organism was thus accelerated, but he recognised that some organs could develop with displacements in position (heterotopy

Heterotopy is an evolutionary change in the spatial arrangement of an animal's embryonic development, complementary to heterochrony, a change to the rate or timing of a development process. It was first identified by Ernst Haeckel in 1866 and ha ...

, another concept he originated) or time (heterochrony), as exceptions to his rule. He thus intended the term to mean a change in the timing of the embryonic development of one organ with respect to the rest of the same animal, whereas it is now used, following the work of the British evolutionary embryologist Gavin de Beer

Sir Gavin Rylands de Beer (1 November 1899 – 21 June 1972) was a British evolutionary embryologist, known for his work on heterochrony as recorded in his 1930 book ''Embryos and Ancestors''. He was director of the Natural History Museum, Lon ...

in 1930, to mean a change with respect to the development of the same organ in the animal's ancestors.

In 1928, the English embryologist Walter Garstang

Walter Garstang FLS FZS (9 February 1868 – 23 February 1949), a Fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford and Professor of Zoology at the University of Leeds, was one of the first to study the functional biology of marine invertebrate larvae. His ...

showed that tunicate

A tunicate is a marine invertebrate animal, a member of the subphylum Tunicata (). It is part of the Chordata, a phylum which includes all animals with dorsal nerve cords and notochords (including vertebrates). The subphylum was at one time ca ...

larvae shared structures such as the notochord

In anatomy, the notochord is a flexible rod which is similar in structure to the stiffer cartilage. If a species has a notochord at any stage of its life cycle (along with 4 other features), it is, by definition, a chordate. The notochord consis ...

with adult vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

s, and suggested that the vertebrates arose by paedomorphosis (neoteny) from such a larva. The proposal implied (if it were correct) a shared phylogeny of tunicates and vertebrates, and that heterochrony was a principal mechanism of evolutionary change.

Modern evolutionary developmental biology

Evolutionary developmental biology (informally, evo-devo) is a field of biological research that compares the developmental processes of different organisms to infer how developmental processes evolved.

The field grew from 19th-century beginni ...

(evo-devo) studies the molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a sub-field of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the ...

of development. It seeks to explain each step in the creation of an adult organism from an undifferentiated zygote

A zygote (, ) is a eukaryotic cell formed by a fertilization event between two gametes. The zygote's genome is a combination of the DNA in each gamete, and contains all of the genetic information of a new individual organism.

In multicellula ...

in terms of the control of expression of one gene after another. Further, it relates such patterns of control of development to phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

. De Beer to some extent anticipated such late 20th-century science in his 1930 book ''Embryos and Ancestors

Sir Gavin Rylands de Beer (1 November 1899 – 21 June 1972) was a British evolutionary embryologist, known for his work on heterochrony as recorded in his 1930 book ''Embryos and Ancestors''. He was director of the Natural History Museum, Lond ...

'', showing that evolution could occur by heterochrony, such as in paedomorphosis, the retention of juvenile features in the adult. De Beer argued that this enabled rapid evolutionary change, too brief to be recorded in the fossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved in ...

, and in effect explaining why apparent gaps were likely.

Mechanisms

Ambystoma talpoideum

''Ambystoma talpoideum'', the mole salamander, is a species of salamander found in much of the eastern and central United States, from Florida to Texas, north to Illinois, east to Kentucky, with isolated populations in Virginia and Indiana. Older ...

'' delay the metamorphosis of the skull. Reilly and colleagues argue we can define these variant individuals as ''paedotypic'' (with truncated development relative to the ancestral condition), ''peratypic'' (with extended development relative to the ancestral condition), or ''isotypic'' (reaching the same ancestral shape, but via a different mechanism).

Interspecific heterochrony means differences in the rate or timing of a descendant species relative to its ancestor. This can result in either ''paedomophosis'' (truncating the ancestral ontogeny), ''peramorphosis

In evolutionary developmental biology, heterochrony is any genetically controlled difference in the timing, rate, or duration of a developmental process in an organism compared to its ancestors or other organisms. This leads to changes in the si ...

'' (extending past the ancestral ontogeny), or ''isomorphosis'' (reaching the same ancestral state via a different mechanism).

There are three major mechanisms of heterochrony, each of which can change in either of two directions, giving six types of perturbations, which can be combined in various ways. These ultimately result in extended, shifted, or truncated development of a particular process, such as the action of a single toolkit gene, relative to the ancestral condition or to other conspecifics, depending on whether inter- or intraspecific heterochrony is the focus. Identifying which of the six perturbations is occurring is critical in identifying the actual underlying mechanism driving peramorphosis or paedomorphosis.

*Onset: A developmental process can either begin earlier, ''pre-displacement'', extending its development, or later, ''post-displacement'', truncating it.

*Offset: A process can either end later, ''hypermorphosis'', extending its development, or earlier, ''hypomorphosis'' or ''progenesis'', truncating it.

*Rate: The rate of a process can accelerate, extending its development, or decelerate (as in neoteny), truncating it.

A dramatic illustration of how acceleration can change a

*Onset: A developmental process can either begin earlier, ''pre-displacement'', extending its development, or later, ''post-displacement'', truncating it.

*Offset: A process can either end later, ''hypermorphosis'', extending its development, or earlier, ''hypomorphosis'' or ''progenesis'', truncating it.

*Rate: The rate of a process can accelerate, extending its development, or decelerate (as in neoteny), truncating it.

A dramatic illustration of how acceleration can change a body plan

A body plan, ( ), or ground plan is a set of morphological features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually applied to animals, envisages a "blueprin ...

is seen in snake

Snakes are elongated, Limbless vertebrate, limbless, carnivore, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other Squamata, squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping Scale (zoology), scales. Ma ...

s. Where a typical vertebrate like a mouse has only around 60 vertebrae, snakes have between around 150 to 400, giving them extremely long spinal columns and enabling their sinuous locomotion

Locomotion means the act or ability of something to transport or move itself from place to place.

Locomotion may refer to:

Motion

* Motion (physics)

* Robot locomotion, of man-made devices

By environment

* Aquatic locomotion

* Flight

* Locomo ...

. Snake embryos achieve this by accelerating their system for creating somite

The somites (outdated term: primitive segments) are a set of bilaterally paired blocks of paraxial mesoderm that form in the embryonic stage of somitogenesis, along the head-to-tail axis in segmented animals. In vertebrates, somites subdivide in ...

s (body segments), which relies on an oscillator. The oscillator clock runs some four times faster in snake than in mouse embryos, initially creating very thin somites. These expand to adopt a typical vertebrate shape, elongating the body.

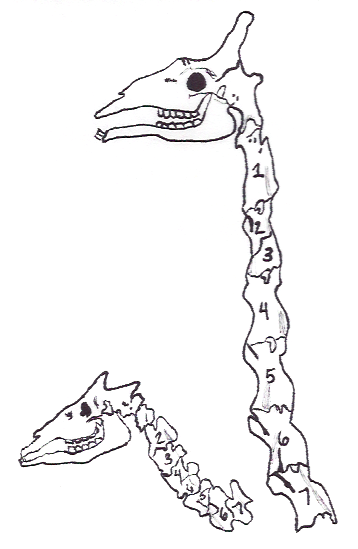

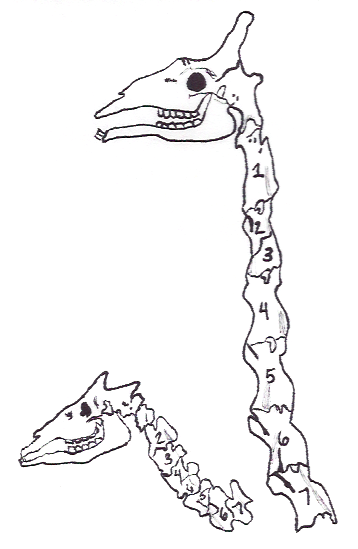

Giraffes

The giraffe is a large African hoofed mammal belonging to the genus ''Giraffa''. It is the tallest living terrestrial animal and the largest ruminant on Earth. Traditionally, giraffes were thought to be one species, ''Giraffa camelopardalis ...

gain their long necks by a different heterochrony, extending the development of their cervical vertebrae; they retain the usual mammalian number of these vertebrae, seven. This number appears to be constrained by the use of neck somites to form the mammalian diaphragm muscle; the result is that the embryonic neck is divided into three modules, the middle one (C3 to C5) serving the diaphragm. The assumption is that disrupting this would kill the embryo rather than giving it more vertebrae.

Detection

Heterochrony can be identified by comparingphylogenetically

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

close species, for example a group of different bird species whose legs differ in their average length. These comparisons are complex because there are no universal ontogenetic timemarkers. The method of event pairing attempts to overcome this by comparing the relative timing of two events at a time. This method detects event heterochronies, as opposed to allometric

Allometry is the study of the relationship of body size to shape, anatomy, physiology and finally behaviour, first outlined by Otto Snell in 1892, by D'Arcy Thompson in 1917 in ''On Growth and Form'' and by Julian Huxley in 1932.

Overview

Allome ...

changes. It is cumbersome to use because the number of event pair characters increases with the square of the number of events compared. Event pairing can however be automated, for instance with the PARSIMOV script. A recent method, continuous analysis, rests on a simple standardization of ontogenetic time or sequences, on squared change parsimony and phylogenetic independent contrasts.

Effects

Paedomorphosis

Paedomorphosis can be the result of

Paedomorphosis can be the result of neoteny

Neoteny (), also called juvenilization,Montagu, A. (1989). Growing Young. Bergin & Garvey: CT. is the delaying or slowing of the physiological, or somatic, development of an organism, typically an animal. Neoteny is found in modern humans compared ...

, the retention of juvenile traits into the adult form as a result of retardation of somatic development, or of progenesis, the acceleration of developmental processes such that the juvenile form becomes a sexually mature adult. This means that in progenesis, germ cell growth is accelerated relative to normal or in neoteny; while somatic cell growth is normal in progenesis, but retarded in neoteny.

Neoteny retards the development of the organism into an adult, and has been described as "eternal childhood". In this form of heterochrony, the developmental stage of childhood is itself extended, and certain developmental processes that normally take place only during childhood (such as accelerated brain growth in humans), is also extended throughout this period. Neoteny has been implicated as a developmental cause for a number of behavior changes, as a result of increased brain plasticity and extended childhood.

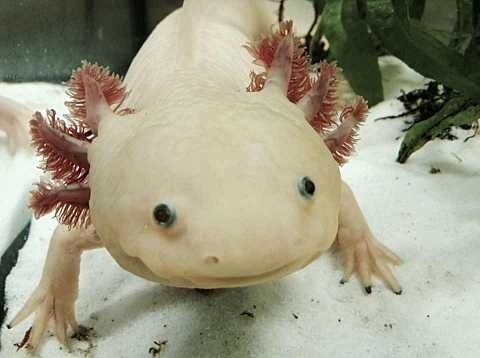

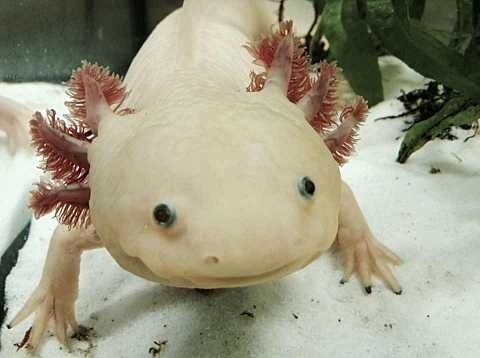

Progenesis (or paedogenesis) can be observed in the axolotl

The axolotl (; from nci, āxōlōtl ), ''Ambystoma mexicanum'', is a paedomorphic salamander closely related to the tiger salamander. Axolotls are unusual among amphibians in that they reach adulthood without undergoing metamorphosis. Instea ...

(''Ambystoma mexicanum''). Axolotls reach full sexual maturity while retaining their fins and gills (in other words, still in the juvenile form of their ancestors). They will remain in aquatic environments in this truncated developmental form, rather than moving onto land as other sexually mature salamander species. This is thought to be a form of hypomorphosis (earlier ending of development) that is both hormonally and genetically driven. The entire metamorphosis that would allow the salamander to transition into the adult form is essentially blocked by both of these drivers.

Paedomorphosis by progenesis may play a critical role in avian cranial evolution. The skulls and beaks of living, adult birds retain the anatomy of the juvenile theropod dinosaur

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally ...

s from which they evolved. Extant birds have large eyes and brains relative to the rest of the skull; a condition seen in adult birds that represents (broadly speaking) the juvenile stage of a dinosaur. A juvenile avian ancestor (as typified by ''Coelophysis

''Coelophysis'' ( traditionally; or , as heard more commonly in recent decades) is an extinct genus of coelophysid theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 228 to 201.3 million years ago during the latter part of the Triassic Period from t ...

'') would have a short face, large eyes, a thin palate, narrow jugal bone, tall and thin postorbitals, restricted adductors, and a short and bulbous braincase. As an organism such as this aged, they would change greatly in their cranial morphology to develop a robust skull with larger, overlapping bones. Birds, however, retain this juvenile morphology. Evidence from molecular experiments suggests both fibroblast growth factor

Fibroblast growth factors (FGF) are a family of cell signalling proteins produced by macrophages; they are involved in a wide variety of processes, most notably as crucial elements for normal development in animal cells. Any irregularities in the ...

8 (FGF8) and members of the WNT signalling pathway

The Wnt signaling pathways are a group of signal transduction pathways which begin with proteins that pass signals into a cell through cell surface receptors. The name Wnt is a portmanteau created from the names Wingless and Int-1. Wnt signaling p ...

have facilitated paedomorphosis in birds. These signalling pathways are known to play roles in facial patterning in other vertebrate species. This retention of the juvenile ancestral state has driven other changes in the anatomy that result in a light, highly kinetic (moveable) skull composed of many small, non''-''overlapping bones. This is believed to have facilitated the evolution of cranial kinesis in birds which has played a critical role in their ecological success.

Peramorphosis

Peramorphosis is delayed maturation with extended periods of growth. An example is the extinct

Peramorphosis is delayed maturation with extended periods of growth. An example is the extinct Irish elk

The Irish elk (''Megaloceros giganteus''), also called the giant deer or Irish deer, is an extinct species of deer in the genus ''Megaloceros'' and is one of the largest deer that ever lived. Its range extended across Eurasia during the Pleisto ...

. From the fossil record, its antlers spanned up to wide, which is about a third larger than the antlers of its close relative, the moose

The moose (in North America) or elk (in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is a member of the New World deer subfamily and is the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is the largest and heaviest extant species in the deer family. Most adult mal ...

. The Irish elk had larger antlers due to extended development during their period of growth.

Another example of peramorphosis is seen in insular (island) rodents. Their characteristics include gigantism, wider cheek and teeth, reduced litter

Litter consists of waste products that have been discarded incorrectly, without consent, at an unsuitable location. Litter can also be used as a verb; to litter means to drop and leave objects, often man-made, such as aluminum cans, paper cups, ...

size, and longer lifespan. Their relatives that inhabit continental environments are much smaller. Insular rodents have evolved these features to accommodate the abundance of food and resources they have on their islands. These factors are part of a complex phenomenon termed Island syndrome or Foster's rule

Fosters or Foster's may refer to:

Places

* Fosters, Alabama

* Fosters, Michigan

* Fosters, Ohio

Television

* ''The Fosters'' (British TV series), a short-lived British sitcom that ran from 1976 to 1977

* ''The Fosters'' (American TV series), ...

.

The mole salamander

The mole salamanders (genus ''Ambystoma'') are a group of advanced salamanders endemic to North America. The group has become famous due to the presence of the axolotl (''A. mexicanum''), widely used in research due to its paedomorphosis, and t ...

, a close relative to the axolotl, displays both paedomorphosis and peramorphosis. The larva can develop in either direction. Population density, food, and the amount of water may have an effect on the expression of heterochrony. A study conducted on the mole salamander in 1987 found it evident that a higher percentage of individuals became paedomorphic when there was a low larval population density in a constant water level as opposed to a high larval population density in drying water. This had an implication that led to hypotheses that selective pressures imposed by the environment, such as predation and loss of resources, were instrumental to the cause of these trends. These ideas were reinforced by other studies, such as peramorphosis in the Puerto Rican tree frog. Another reason could be generation time

In population biology and demography, generation time is the average time between two consecutive generations in the lineages of a population. In human populations, generation time typically ranges from 22 to 33 years. Historians sometimes use this ...

, or the lifespan of the species in question. When a species has a relatively short lifespan, natural selection favors evolution of paedomorphosis (e.g. Axolotl: 7–10 years). Conversely, in long lifespans natural selection favors evolution of peramorphosis (e.g. Irish Elk: 20–22 years).

Across the animal kingdom

Heterochrony is responsible for a wide variety of effects such as the lengthening of the fingers by adding extraphalanges

The phalanges (singular: ''phalanx'' ) are digital bones in the hands and feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the thumbs and big toes have two phalanges while the other digits have three phalanges. The phalanges are classed as long bones.

...

in dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal within the infraorder Cetacea. Dolphin species belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (the ...

s to form their flippers, sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

, and the polymorphism seen between insect caste

Eusociality (from Greek εὖ ''eu'' "good" and social), the highest level of organization of sociality, is defined by the following characteristics: cooperative brood care (including care of offspring from other individuals), overlapping genera ...

s.

Garstang's hypothesis

Walter Garstang

Walter Garstang FLS FZS (9 February 1868 – 23 February 1949), a Fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford and Professor of Zoology at the University of Leeds, was one of the first to study the functional biology of marine invertebrate larvae. His ...

suggested the neotenous origin of the vertebrates from a tunicate

A tunicate is a marine invertebrate animal, a member of the subphylum Tunicata (). It is part of the Chordata, a phylum which includes all animals with dorsal nerve cords and notochords (including vertebrates). The subphylum was at one time ca ...

larva, in opposition to Darwins opinion that tunicate

A tunicate is a marine invertebrate animal, a member of the subphylum Tunicata (). It is part of the Chordata, a phylum which includes all animals with dorsal nerve cords and notochords (including vertebrates). The subphylum was at one time ca ...

s and vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

s both evolved from animals whose adult form was similar to (frog) tadpoles and the 'tadpole larvae' of tunicates. According to Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins (born 26 March 1941) is a British evolutionary biologist and author. He is an emeritus fellow of New College, Oxford and was Professor for Public Understanding of Science in the University of Oxford from 1995 to 2008. An ath ...

, Garstang's opinion was also held by Alister Hardy

Sir Alister Clavering Hardy (10 February 1896 – 22 May 1985) was an English marine biologist, an expert on marine ecosystems spanning organisms from zooplankton to whales. He had the artistic skill to illustrate his books with his own drawings ...

, and is still held by some modern biologists. However, according to others, closer genetic investigation rather seems to support Darwin's old opinion:

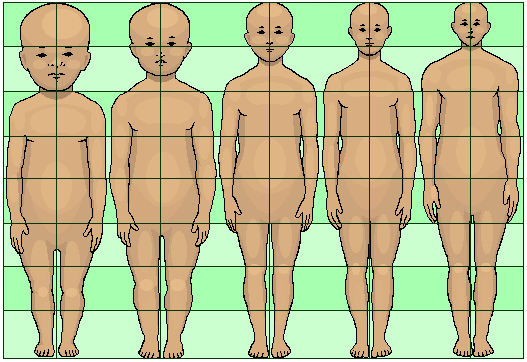

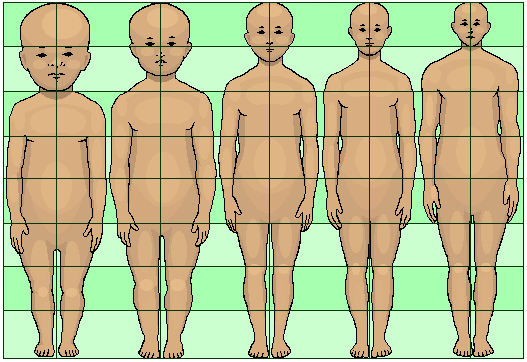

In humans

Several heterochronies have been described in humans, relative to thechimpanzee

The chimpanzee (''Pan troglodytes''), also known as simply the chimp, is a species of great ape native to the forest and savannah of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed subspecies. When its close relative th ...

. In chimpanzee fetus

A fetus or foetus (; plural fetuses, feti, foetuses, or foeti) is the unborn offspring that develops from an animal embryo. Following embryonic development the fetal stage of development takes place. In human prenatal development, fetal deve ...

es, brain and head growth starts at about the same developmental stage and grow at a rate similar to that of humans, but growth stops soon after birth, whereas humans continue brain and head growth several years after birth. This particular type of heterochrony, hypermorphosis, involves a delay in the offset of a developmental process, or what is the same, the presence of an early developmental process in later stages of development. Humans have some 30 different neotenies in comparison to the chimpanzee, retaining larger heads, smaller jaws and noses, and shorter limbs, features found in juvenile chimpanzees.Related concepts

The term "heterokairy" was proposed in 2003 by John Spicer and Warren Burggren to distinguish plasticity in timing of the onset of developmental events at the level of an individual or population.See also

* ''Ontogeny and Phylogeny

''Ontogeny and Phylogeny'' is a 1977 book on evolution by Stephen Jay Gould, in which the author explores the relationship between embryonic development (ontogeny) and biological evolution (phylogeny). Unlike his many popular books of essays, it ...

''

References

See also

*Developmental biology

Developmental biology is the study of the process by which animals and plants grow and develop. Developmental biology also encompasses the biology of Regeneration (biology), regeneration, asexual reproduction, metamorphosis, and the growth and di ...

* Embryogenesis

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sperm ...

* Evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes (natural selection, common descent, speciation) that produced the diversity of life on Earth. It is also defined as the study of the history of life fo ...

* Phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

{{genarch

Developmental biology

Evolutionary biology concepts

Evolutionary developmental biology