Herero massacre on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Herero and Nama genocide (formerly, also 'Herero and Namaqua genocide') was a campaign of ethnic extermination and

The original inhabitants of what is now

The original inhabitants of what is now

''Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts''

Survivors of the massacre, the majority of whom were women and children, were eventually put in places like

Survivors of the massacre, the majority of whom were women and children, were eventually put in places like

''The Practice of War: Production, Reproduction and Communication of Armed violence''

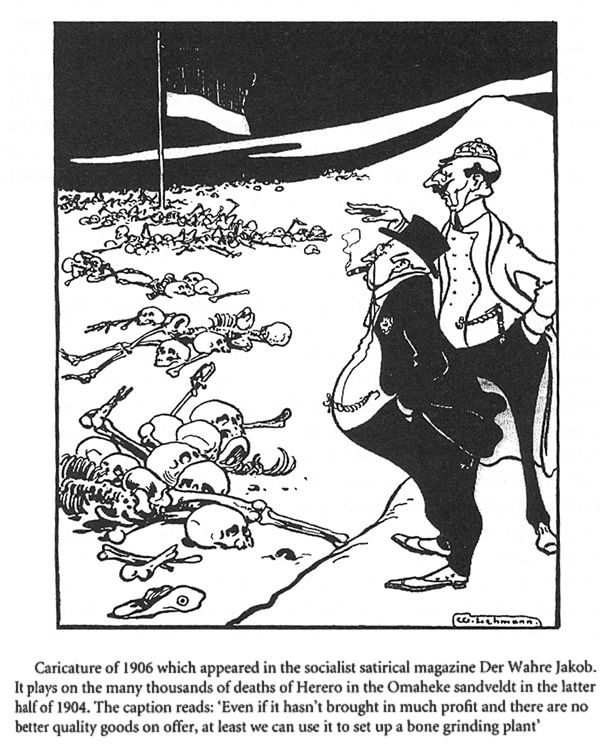

Prevent Genocide International There are accusations of Herero women being coerced into sex slavery as a means of survival. Trotha was opposed to contact between natives and settlers, believing that the insurrection was "the beginning of a racial struggle" and fearing that the colonists would be infected by native diseases. Benjamin Madley argues that although Shark Island is referred to as a concentration camp, it functioned as an extermination camp or death camp.

''The History and Sociology of Genocide : Analyses and Case Studies''

Montreal Institute for Genocide Studies, Newspapers reported 65,000 victims when announcing that Germany recognized the genocide in 2004.

Newspapers reported 65,000 victims when announcing that Germany recognized the genocide in 2004.

With the closure of concentration camps, all surviving Herero were distributed as labourers for settlers in the German colony. From that time on, all Herero over the age of seven were forced to wear a metal disc with their labour registration number, and banned from owning land or cattle, a necessity for pastoral society.

About 19,000 German troops were engaged in the conflict, of which 3,000 saw combat. The rest were used for upkeep and administration. The German losses were 676 soldiers killed in combat, 76 missing, and 689 dead from disease. The Reiterdenkmal ( en, Equestrian Monument) in Windhoek was erected in 1912 to celebrate the victory and to remember the fallen German soldiers and civilians. Until after Independence, no monument was built to the killed indigenous population. It remains a bone of contention in independent Namibia.

The campaign cost Germany 600 million

With the closure of concentration camps, all surviving Herero were distributed as labourers for settlers in the German colony. From that time on, all Herero over the age of seven were forced to wear a metal disc with their labour registration number, and banned from owning land or cattle, a necessity for pastoral society.

About 19,000 German troops were engaged in the conflict, of which 3,000 saw combat. The rest were used for upkeep and administration. The German losses were 676 soldiers killed in combat, 76 missing, and 689 dead from disease. The Reiterdenkmal ( en, Equestrian Monument) in Windhoek was erected in 1912 to celebrate the victory and to remember the fallen German soldiers and civilians. Until after Independence, no monument was built to the killed indigenous population. It remains a bone of contention in independent Namibia.

The campaign cost Germany 600 million

In 1998, German President

In 1998, German President

Official German apologies

{{Authority control 1904 in Africa 1904 establishments in German South West Africa 1908 disestablishments in German South West Africa Anti-black racism in Africa African resistance to colonialism Conflicts in 1904 Genocide of indigenous peoples in Africa Ethnic cleansing in Africa German South West Africa Imperial German war crimes Germany–Namibia relations Guerrilla wars Herero people Herero Wars Medical experimentation on prisoners Rebellions in Africa Wars involving Germany January 1904 events Mass murder in 1904

collective punishment

Collective punishment is a punishment or sanction imposed on a group for acts allegedly perpetrated by a member of that group, which could be an ethnic or political group, or just the family, friends and neighbors of the perpetrator. Because ind ...

which was waged against the Herero

Herero may refer to:

* Herero people, a people belonging to the Bantu group, with about 240,000 members alive today

* Herero language, a language of the Bantu family (Niger-Congo group)

* Herero and Namaqua Genocide

* Herero chat, a species of b ...

(Ovaherero) and the Nama in German South West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

(now Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

) by the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

. It was the first genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

to begin in the 20th century, occurring between 1904 and 1908.

In January 1904, the Herero people, who were led by Samuel Maharero

Samuel Maharero (1856 – 14 March 1923) was a Paramount Chief of the Herero people in German South West Africa (today Namibia) during their revolts and in connection with the events surrounding the Herero genocide. Today he is considered a na ...

, and the Nama people, who were led by Captain Hendrik Witbooi, rebelled against German colonial rule. On January 12, they killed more than 100 German settlers in the area of Okahandja

Okahandja is a city of 24,100 inhabitants in Otjozondjupa Region, central Namibia, and the district capital of the Okahandja electoral constituency. It is known as the ''Garden Town of Namibia''. It is located 70 km north of Windhoek on the ...

.

In August, German General Lothar von Trotha

General Adrian Dietrich Lothar von Trotha (3 July 1848 – 31 March 1920) was a German military commander during the European new colonial era. As a brigade commander of the East Asian Expedition Corps, he was involved in suppressing the Boxe ...

defeated the Ovaherero in the Battle of Waterberg

The Battle of Waterberg (Battle of Ohamakari) took place on August 11, 1904 at the Waterberg, German South West Africa (modern day Namibia), and was the decisive battle in the German campaign against the Herero.

Armies

The German Imperial For ...

and drove them into the desert of Omaheke

Omaheke ( hz, Sandveld) is one of the fourteen regions of Namibia, the least populous region. Its capital is Gobabis. It lies in eastern Namibia on the border with Botswana and is the western extension of the Kalahari desert. The self-governed vil ...

, where most of them died of dehydration

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water, with an accompanying disruption of metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds free water intake, usually due to exercise, disease, or high environmental temperature. Mil ...

. In October, the Nama people also rebelled against the Germans, only to suffer a similar fate.

Between 24,000 and 100,000 Hereros and 10,000 Nama were killed in the genocide. The first phase of the genocide was characterized by widespread death from starvation and dehydration, due to the prevention of the Herero from leaving the Namib

The Namib ( ; pt, Namibe) is a coastal desert in Southern Africa. The name is of Khoekhoegowab origin and means "vast place". According to the broadest definition, the Namib stretches for more than along the Atlantic coasts of Angola, Namib ...

desert by German forces. Once defeated, thousands of Hereros and Namas were imprisoned in concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

, where the majority died of diseases, abuse, and exhaustion.

In 1985, the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

' Whitaker Report classified the aftermath as an attempt to exterminate the Herero and Nama peoples of South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

, and therefore one of the earliest attempts at genocide in the 20th century. In 2004, the German government recognised the events – in what a German minister qualified as an "apology" –, but ruled out financial compensation for the victims' descendants. In July 2015, the German government and the speaker of the Bundestag

The Bundestag (, "Federal Diet") is the German federal parliament. It is the only federal representative body that is directly elected by the German people. It is comparable to the United States House of Representatives or the House of Commons ...

officially called the events a "genocide". However, it refused to consider reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for reparation

* Acts of reparation, prayers for repairing the damages of sin

History

*War reparations

**World War I reparations, made from G ...

at that time. Despite this, the last batch of skulls and other remains of slaughtered tribesmen which were taken to Germany to promote racial superiority were taken back to Namibia in 2018, with , a German Protestant bishop, describing the event as "the first genocide of the 20th century".

In May 2021, the German government issued an official statement in which it said that Germany“apologizes and bows before the descendants of the victims. Today, more than 100 years later, Germany asks for forgiveness for the sins of their forefathers. It is not possible to undo what has been done. But the suffering, inhumanity and pain inflicted on the tens of thousands of innocent men, women and children by Germany during the war in what is today Namibia must not be forgotten. It must serve as a warning against racism and genocide.”Furthermore, the German government agreed to pay €1.1 billion over 30 years to fund projects in communities that were impacted by the genocide.

Background

The original inhabitants of what is now

The original inhabitants of what is now Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

were the San and the Khoekhoe

Khoekhoen (singular Khoekhoe) (or Khoikhoi in the former orthography; formerly also '' Hottentots''"Hottentot, n. and adj." ''OED Online'', Oxford University Press, March 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/88829. Accessed 13 May 2018. Citing G. S. ...

.

Herero, who speak a Bantu language

The Bantu languages (English: , Proto-Bantu: *bantʊ̀) are a large family of languages spoken by the Bantu people of Central, Southern, Eastern africa and Southeast Africa. They form the largest branch of the Southern Bantoid languages.

The t ...

, were originally a group of cattle herders who migrated into what is now Namibia during the mid-18th century. The Herero seized vast swathes of the arable upper plateaus which were ideal for cattle grazing. Agricultural duties, which were minimal, were assigned to enslaved Khoisan

Khoisan , or (), according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography, is a catch-all term for those indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who do not speak one of the Bantu languages, combining the (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the or ( in t ...

and Bushmen

The San peoples (also Saan), or Bushmen, are members of various Khoe, Tuu, or Kxʼa-speaking indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures that are the first cultures of Southern Africa, and whose territories span Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia, ...

. Over the rest of the 18th century, the Herero slowly drove the Khoisan into the dry, rugged hills to the south and east.

The Hereros were a pastoral people whose entire way of life centred on their cattle. The Herero language

Herero (, ''Otjiherero'') is a Bantu language spoken by the Herero and Mbanderu peoples in Namibia and Botswana, as well as by small communities of people in southwestern Angola. There were 211,700 speakers in 2014.

Distribution

Its lingui ...

, while limited in its vocabulary for most areas, contains more than a thousand words for the colours and markings of cattle. The Hereros were content to live in peace as long as their cattle were safe and well-pastured, but became formidable warriors when their cattle were threatened.

According to Robert Gaudi, "The newcomers, much taller and more fiercely warlike than the indigenous Khoisan people, were possessed of the fierceness that comes from basing one's way of life on a single source: everything they valued, all wealth and personal happiness, had to do with cattle. Regarding the care and protection of their herds, the Herero showed themselves utterly merciless, and far more 'savage' than the Khoisan had ever been. Because of their dominant ways and elegant bearing, the few Europeans who encountered Herero tribesmen in the early days regarded them as the region's 'natural aristocrats.

By the time of the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonisation of Africa, colonization of most of Africa by seven Western Europe, Western European powers during a ...

, the area which was occupied by the Herero was known as Damaraland

Damaraland was a name given to the north-central part of what later became Namibia, inhabited by the Damara (people), Damaras. It was bounded roughly by Ovamboland in the north, the Namib Desert in the west, the Kalahari Desert in the east, a ...

. The Nama were pastorals

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depicts ...

and traders and lived to the south of the Herero.

In 1883, Adolf Lüderitz

Franz Adolf Eduard Lüderitz (16 July 1834 – end of October 1886) was a German merchant and the founder of German South West Africa, Imperial Germany's first colony. The coastal town of Lüderitz, located in the ǁKaras Region of southern N ...

, a German merchant, purchased a stretch of coast near Lüderitz Bay

Lüderitz Bay or Lüderitzbaai (german: Lüderitzbucht), also known as Angra Pequena (, "small cove"), is a bay in the coast of Namibia, Africa. The city of Lüderitz is located at the edge of the bay.

Geography

The bay is indented and comple ...

(Angra Pequena) from the reigning chief. The terms of the purchase were fraudulent, but the German government nonetheless established a protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

over it. At that time, it was the only overseas German territory deemed suitable for European settlement.

Chief of the neighbouring Herero, Maharero

Maharero kaTjamuaha (Otjiherero: ''Maharero, son of Tjamuaha'', short: Maharero; 1820 – 7 October 1890) was one of the most powerful paramount chiefs of the Herero people in South-West Africa, today's Namibia.

Early life

Maharero, was b ...

rose to power by uniting all the Herero. Faced with repeated attacks by the Khowesin, a clan of the Khoekhoe

Khoekhoen (singular Khoekhoe) (or Khoikhoi in the former orthography; formerly also '' Hottentots''"Hottentot, n. and adj." ''OED Online'', Oxford University Press, March 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/88829. Accessed 13 May 2018. Citing G. S. ...

under Hendrik Witbooi, he signed a protection treaty on 21 October 1885 with Imperial Germany

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

's colonial governor Heinrich Ernst Göring

Heinrich Ernst Göring (31 October 1839 – 7 December 1913) was a German jurist and diplomat who served as colonial governor of German South West Africa. He was the father of five children including Hermann Göring, the Nazi leader and comman ...

(father of Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

) but did not cede the land of the Herero. This treaty was renounced in 1888 due to lack of German support against Witbooi but it was reinstated in 1890.

The Herero leaders repeatedly complained about violation of this treaty, as Herero women and girls were raped by Germans, a crime that the German judges and prosecuctors were reluctant to punish.

In 1890 Maharero's son, Samuel

Samuel ''Šəmūʾēl'', Tiberian: ''Šămūʾēl''; ar, شموئيل or صموئيل '; el, Σαμουήλ ''Samouḗl''; la, Samūēl is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the bibl ...

, signed a great deal of land over to the Germans in return for helping him to ascend to the Ovaherero throne, and to subsequently be established as paramount chief. German involvement in ethnic fighting ended in tenuous peace in 1894. In that year, Theodor Leutwein

Theodor Gotthilf Leutwein (9 May 1849 – 13 April 1921) was colonial administrator of German Southwest Africa from 1894 to 1904 (as commander of its Schutztruppe, and from 1898, governor).

Life and career

Born in Strümpfelbrunn in the ...

became governor of the territory, which underwent a period of rapid development, while the German government sent the (imperial colonial troops) to pacify the region.

German colonial policy

Both German colonial authorities and European settlers envisioned a predominately white "new African Germany," wherein the native populations would be put onto reservations and their land distributed among settlers and companies. Under German colonial rule, colonists were encouraged to seize land and cattle from the nativeHerero

Herero may refer to:

* Herero people, a people belonging to the Bantu group, with about 240,000 members alive today

* Herero language, a language of the Bantu family (Niger-Congo group)

* Herero and Namaqua Genocide

* Herero chat, a species of b ...

and Nama peoples and to subjugate them as slave laborers.Steinmetz, George (2007) ''The Devil's Handwriting: Precoloniality and the German Colonial State in Qingdao, Samoa, and Southwest Africa'', University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press is the largest and one of the oldest university presses in the United States. It is operated by the University of Chicago and publishes a wide variety of academic titles, including ''The Chicago Manual of Style'', ...

Resentment brewed among the native populations over their loss of status and property to German ranchers arriving in South West Africa, and the dismantling of traditional political hierarchies. Previously ruling tribes were reduced to the same status as the other tribes they had previously ruled over and enslaved. This resentment contributed to the Herero Wars

The Herero Wars were a series of colonial wars between the German Empire and the Herero people of German South West Africa (present-day Namibia). They took place between 1904 and 1908.

Background Pre-colonial South-West Africa

The Hereros wer ...

that began in 1904.

Major Theodor Leutwein

Theodor Gotthilf Leutwein (9 May 1849 – 13 April 1921) was colonial administrator of German Southwest Africa from 1894 to 1904 (as commander of its Schutztruppe, and from 1898, governor).

Life and career

Born in Strümpfelbrunn in the ...

, the Governor of German South West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

, was well aware of the effect of the German colonial rule on Hereros. He later wrote: "The Hereros from early years were a freedom-loving people, courageous and proud beyond measure. On the one hand, there was the progressive extension of German rule over them, and on the other their own sufferings increasing from year to year."

The Dietrich case

In January 1903, a German trader named Dietrich was walking from his homestead to the nearby town of Omaruru to buy a new horse. Halfway to Dietrich's destination, a wagon carrying the son of a Herero chief, his wife, and their son stopped by. In a common courtesy in Hereroland, the chief's son offered Dietrich a ride. That night, however, Dietrich got very drunk and after everyone was asleep, he attempted to rape the wife of the chief's son. When she resisted, Dietrich shot her dead. When he was tried for murder inWindhoek

Windhoek (, , ) is the capital and largest city of Namibia. It is located in central Namibia in the Khomas Highland plateau area, at around above sea level, almost exactly at the country's geographical centre. The population of Windhoek in 20 ...

, Dietrich denied attempting to rape his victim. He alleged that he awoke thinking the camp was under attack and fired blindly into the darkness. The killing of the Herero woman, he claimed, was an unfortunate accident. The court acquitted him, alleging that Dietrich was suffering from "tropical fever" and temporary insanity

The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to an episodic psychiatric disease at the time of the ...

.

According to Leutwein, the murder "aroused extraordinary interest in Hereroland, especially since the murdered woman had been the wife of the son of a Chief and the daughter of another. Everywhere the question was asked: Have White people the right to shoot native women?"

Governor Leutwein intervened. He had the Public Prosecutor

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the common law adversarial system or the civil law inquisitorial system. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the case in a criminal trial ...

appeal Dietrich's acquittal, a second trial took place (before the colony's supreme court), and this time Dietrich was found guilty of manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th cen ...

and imprisoned. The move prompted violent objections of German settlers who considered Leutwein a "race traitor

Race traitor is a pejorative reference to a person who is perceived as supporting attitudes or positions thought to be against the supposed interests or well-being of that person's own race. The term is the source of the name of a quarterly magazi ...

".

Rising tension

In 1903, some of the Nama clans rose in revolt under the leadership of Hendrik Witbooi. A number of factors led the Herero to join them in January 1904. One of the major issues was land rights. In 1903 the Herero learned of a plan to divide their territory with a railway line and set up reservations where they would be concentrated. The Herero had already ceded more than a quarter of their territory to German colonists by 1903, before the Otavi railway line running from the African coast to inland German settlements was completed. Completion of this line would have made the German colonies much more accessible and would have ushered a new wave of Europeans into the area.Drechsler, Horst (1980) ''Let Us Die Fighting: the struggle of the Herero and Nama against German imperialism (1884–1915)'', Zed Press, London Historian Horst Drechsler states that there was discussion of the possibility of establishing and placing the Herero in native reserves and that this was further proof of the German colonists' sense of ownership over the land. Drechsler illustrates the gap between the rights of a European and an African; the (German Colonial League) held that, in regards to legal matters, the testimony of seven Africans was equivalent to that of a colonist. According to Bridgman, there were racial tensions underlying these developments; the average German colonist viewed native Africans as a lowly source of cheap labour, and others welcomed their extermination. A new policy ondebt collection

Debt collection is the process of pursuing payments of debts owed by individuals or businesses. An organization that specializes in debt collection is known as a collection agency or debt collector. Most collection agencies operate as agents of ...

, enforced in November 1903, also played a role in the uprising. For many years, the Herero population had fallen in the habit of borrowing money from colonist moneylenders

In finance, a loan is the lending of money by one or more individuals, organizations, or other entities to other individuals, organizations, etc. The recipient (i.e., the borrower) incurs a debt and is usually liable to pay interest on that de ...

at extreme interest rates (see usury

Usury () is the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans that unfairly enrich the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is ch ...

). For a long time, much of this debt went uncollected and accumulated, as most Herero had no means to pay. To correct this growing problem, Governor Leutwein decreed with good intentions that all debts not paid within the next year would be voided. In the absence of hard cash, traders often seized cattle, or whatever objects of value they could get their hands on, as collateral

Collateral may refer to:

Business and finance

* Collateral (finance), a borrower's pledge of specific property to a lender, to secure repayment of a loan

* Marketing collateral, in marketing and sales

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Collate ...

. This fostered a feeling of resentment towards the Germans on the part of the Herero people, which escalated to hopelessness when they saw that German officials were sympathetic to the moneylenders who were about to lose what they were owed.

Racial tension was also at play. The German settlers often referred to black Africans as "baboons" and treated them with contempt.

One missionary reported: "The real cause of the bitterness among the Hereros toward the Germans is without question the fact that the average German looks down upon the natives as being about on the same level as the higher primates ('baboon' being their favourite term for the natives) and treat them like animals. The settler holds that the native has a right to exist only in so far as he is useful to the white man. This sense of contempt led the settlers to commit violence against the Hereros."

The contempt manifested itself particularly in the concubinage

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple does not want, or cannot enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar but mutually exclusive.

Concubin ...

of native women. In a practice referred to in '' Südwesterdeutsch'' as ''Verkafferung'', native women were taken by male European traders and ranchers both willingly and by force.

Revolts

In 1903, the Hereros saw an opportunity to revolt. At that time, there was a distant Khoisan tribe in the south called the Bondelzwarts, who resisted German demands to register their guns. The Bondelzwarts engaged in a firefight with the German authorities which led to three Germans killed and a fourth wounded. The situation deteriorated further, and the governor of the Herero colony, Major Theodor Leutwein, went south to take personal command, leaving almost no troops in the north. The Herero revolted in early 1904, killing between 123 and 150 German settlers, as well as sevenBoers

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this area ...

and three women, in what Nils Ole Oermann calls a "desperate surprise attack".

The timing of their attack was carefully planned. After successfully asking a large Herero clan to surrender their weapons, Governor Leutwein was convinced that they and the rest of the native population were essentially pacified and so withdrew half of the German troops stationed in the colony. Led by Chief Samuel Maharero

Samuel Maharero (1856 – 14 March 1923) was a Paramount Chief of the Herero people in German South West Africa (today Namibia) during their revolts and in connection with the events surrounding the Herero genocide. Today he is considered a na ...

, the Herero surrounded Okahandja

Okahandja is a city of 24,100 inhabitants in Otjozondjupa Region, central Namibia, and the district capital of the Okahandja electoral constituency. It is known as the ''Garden Town of Namibia''. It is located 70 km north of Windhoek on the ...

and cut railroad and telegraph links to Windhoek

Windhoek (, , ) is the capital and largest city of Namibia. It is located in central Namibia in the Khomas Highland plateau area, at around above sea level, almost exactly at the country's geographical centre. The population of Windhoek in 20 ...

, the colonial capital. Maharero then issued a manifesto in which he forbade his troops to kill any Englishmen, Boers, uninvolved peoples, women and children in general, or German missionaries. The Herero revolts catalysed a separate revolt and attack on Fort Namutoni in the north of the country a few weeks later by the Ondonga

Ondonga is a traditional kingdom of the Ovambo people in what is today northern Namibia. Its capital is Ondangwa, and the kingdom's palace is at Onambango. Its people call themselves ''Aandonga''. They speak the Ndonga dialect. The Ondonga kingdom ...

.

A Herero warrior interviewed by German authorities in 1895 had described his people's traditional way of dealing with suspected cattle rustlers

Cattle raiding is the act of stealing cattle. In Australia, such stealing is often referred to as duffing, and the perpetrator as a duffer.Baker, Sidney John (1945) ''The Australian language : an examination of the English language and English s ...

, a treatment which, during the uprising, was regularly extended to German soldiers and civilians, "We came across a few Khoisan whom of course we killed. I myself helped to kill one of them. First we cut off his ears, saying, 'You will never hear Herero cattle lowing.' Then we cut off his nose, saying, 'Never again shall you smell Herero cattle.' And then we cut off his lips, saying, 'You shall never again taste Herero cattle.' And finally we cut his throat."

According to Robert Gaudi, "Leutwein knew that the wrath of the German Empire was about to fall on them and hoped to soften the blow. He sent desperate messages to Chief Samuel Maherero in hopes of negotiating an end to the war. In this, Leutwein acted on his own, heedless of the prevailing mood in Germany, which called for bloody revenge."

The Hereros, however, were emboldened by their success and had come to believe that, "the Germans were too cowardly to fight in the open," and rejected Leutwein's offers of peace.

One missionary wrote, "The Germans are filled with fearful hate. I must really call it a blood thirst against the Hereros. One hears nothing but talk of 'cleaning up,' 'executing,' 'shooting down to the last man,' 'no pardon,' etc."

According to Robert Gaudi, "The Germans suffered more than defeat in the early months of 1904; they suffered humiliation, their brilliant modern army unable to defeat a rabble of 'half-naked savages.' Cries in the Reichstag, and from the Kaiser

''Kaiser'' is the German word for "emperor" (female Kaiserin). In general, the German title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (''König''). In English, the (untranslated) word ''Kaiser'' is mainly ap ...

himself, for total eradication of the Hereros grew strident. When a leading member of the Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

For ...

pointed out that the Hereros were as human as any German and possessed immortal souls, he was howled down by the entire conservative side of the legislature."

Leutwein was forced to request reinforcements and an experienced officer from the German government in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

. Lieutenant-General Lothar von Trotha

General Adrian Dietrich Lothar von Trotha (3 July 1848 – 31 March 1920) was a German military commander during the European new colonial era. As a brigade commander of the East Asian Expedition Corps, he was involved in suppressing the Boxe ...

was appointed commander-in-chief (german: Oberbefehlshaber) of South West Africa, arriving with an expeditionary force of 10,000 troops on 11 June.

Meanwhile, Leutwein was subordinate to the civilian Colonial Department of the Prussian Foreign Office, which was supported by Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow

Bernhard Heinrich Karl Martin, Prince of Bülow (german: Bernhard Heinrich Karl Martin Fürst von Bülow ; 3 May 1849 – 28 October 1929) was a German statesman who served as the foreign minister for three years and then as the chancellor of t ...

, while General Trotha reported to the military German General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (german: Großer Generalstab), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the German Army, responsible for the continuou ...

, which was supported by Emperor Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Empi ...

.

Leutwein wanted to defeat the most determined Herero rebels and negotiate a surrender with the remainder to achieve a political settlement. Trotha, however, planned to crush the native resistance through military force. He stated that:

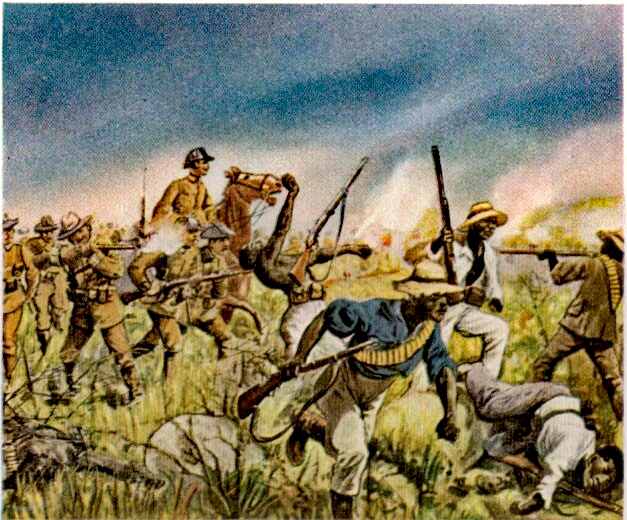

By late spring of 1904, German troops were pouring into the colony. In August 1904, the main Herero forces were surrounded and crushed at the Battle of Waterberg

The Battle of Waterberg (Battle of Ohamakari) took place on August 11, 1904 at the Waterberg, German South West Africa (modern day Namibia), and was the decisive battle in the German campaign against the Herero.

Armies

The German Imperial For ...

.

Genocide

In 1900, Kaiser Wilhelm II had been enraged by the killing of BaronClemens von Ketteler

Clemens August Freiherr von Ketteler (22 November 1853 – 20 June 1900) was a German career diplomat. He was killed during the Boxer Rebellion.

Early life and career

Ketteler was born at Münster in western Germany on 22 November 1853 into a ...

, the Imperial German minister plenipotentiary

An envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary, usually known as a minister, was a diplomatic head of mission who was ranked below ambassador. A diplomatic mission headed by an envoy was known as a legation rather than an embassy. Under th ...

in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

, during the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by ...

. The Kaiser took it as a personal insult from a people he viewed as racially inferior, all the more because of his obsession with the "Yellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror and the Yellow Specter) is a racist, racial color terminology for race, color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East Asia, East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the Western world. As a ...

". On 27 July 1900, the Kaiser gave the infamous '' Hunnenrede'' (Hun speech) in Bremerhaven

Bremerhaven (, , Low German: ''Bremerhoben'') is a city at the seaport of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen, a state of the Federal Republic of Germany.

It forms a semi-enclave in the state of Lower Saxony and is located at the mouth of the Riv ...

to German soldiers being sent to Imperial China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapte ...

, ordering them to show the Boxers no mercy and to behave like Attila

Attila (, ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European traditio ...

's Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

. General von Trotha had served in China, and was chosen in 1904 to command the expedition to German South West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

precisely because of his record in China. In 1904, the Kaiser was furious by the latest revolt in his colonial empire by a people whom he also viewed as inferior, and took the Herero rebellion as a personal insult, just as he had viewed the Boxers' assassination of Baron von Ketteler. The tactless and bloodthirsty language that Wilhelm II used about the Herero people

The Herero ( hz, Ovaherero) are a Bantu ethnic group inhabiting parts of Southern Africa. There were an estimated 250,000 Herero people in Namibia in 2013. They speak Otjiherero, a Bantu language. Though the Herero primarily reside in Namibia, t ...

in 1904 is strikingly similar to the language he had used about the Chinese Boxers in 1900. However, the Kaiser denied, together with Chancellor von Bülow, von Trotha's request to quickly quell the rebellion.

No written order by Wilhelm II ordering or authorising genocide has survived. In February 1945 an Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

bombing raid

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematic ...

destroyed the building housing all of the documents of the Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

from the Imperial period. Despite this fact, surviving documents indicate that Trotha used the same tactics in Namibia that he had used in China, only on a much vaster scale. It is also known that throughout the genocide Trotha sent regular reports to both the General Staff and to the Kaiser. Historian Jeremy-Sarkin Hughes believes that regardless of whether or not a written order was given, the Kaiser must have given General von Trotha verbal orders. According to Hughes, the fact that Trotha was decorated and not court-martialed after the genocide became public knowledge lends support to the thesis that he was acting under orders.

General von Trotha commented: "I know the tribes of Africa…. They are all alike. They only respond to force. It was and is my policy to use force with terrorism and even brutality. I shall annihilate the African tribes with streams of blood and streams of gold." General von Trotha stated his proposed solution to end the resistance of the Herero people in a letter, before the Battle of Waterberg

The Battle of Waterberg (Battle of Ohamakari) took place on August 11, 1904 at the Waterberg, German South West Africa (modern day Namibia), and was the decisive battle in the German campaign against the Herero.

Armies

The German Imperial For ...

:

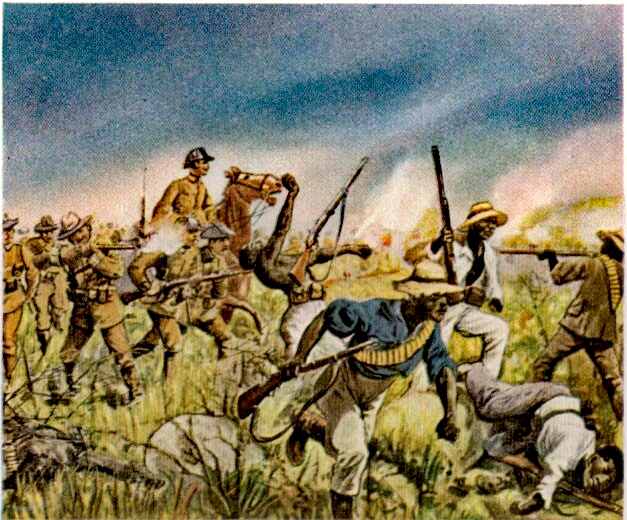

Trotha's troops defeated 3,000–5,000 Herero combatants at the Battle of Waterberg on 11–12 August 1904 but were unable to encircle and annihilate the retreating survivors.

The pursuing German forces prevented groups of Herero from breaking from the main body of the fleeing force and pushed them further into the desert. As exhausted Herero fell to the ground, unable to go on, German soldiers killed men, women, and children. Jan Cloete, acting as a guide for the Germans, witnessed the atrocities committed by the German troops and deposed the following statement:

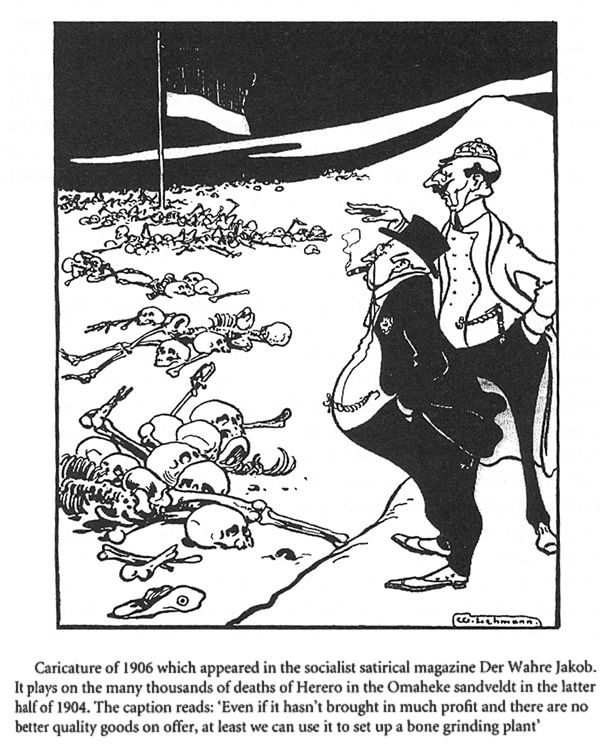

A portion of the Herero escaped the Germans and went to the Omaheke Desert

The Kalahari Desert is a large semi-arid sandy savanna in Southern Africa extending for , covering much of Botswana, and parts of Namibia and South Africa.

It is not to be confused with the Angolan, Namibian, and South African Namib coastal de ...

, hoping to reach British Bechuanaland; fewer than 1,000 Herero managed to reach Bechuanaland, where they were granted asylum by the British authorities. To prevent them from returning, Trotha ordered the desert to be sealed off. German patrols later found skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of an animal. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is the stable outer shell of an organism, the endoskeleton, which forms the support structure inside ...

s around holes deep that had been dug in a vain attempt to find water. Some sources also state that the German colonial army systematically poisoned desert water wells.Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons, Israel W. Charny (2004''Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts''

Routledge

Routledge () is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law, and ...

, NY Dan Kroll (2006) ''Securing Our Water Supply: Protecting a Vulnerable Resource'', p. 22, PennWell Corp/University of Michigan Press Maherero and 500–1,500 men crossed the Kalahari into Bechuanaland where he was accepted as a vassal of the Batswana

The Tswana ( tn, Batswana, singular ''Motswana'') are a Bantu-speaking ethnic group native to Southern Africa. The Tswana language is a principal member of the Sotho-Tswana language group. Ethnic Tswana made up approximately 85% of the popu ...

chief Sekgoma.

On 2 October, Trotha issued a warning to the Herero:

He further gave orders that:

Trotha gave orders that captured Herero males were to be executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

, while women and children were to be driven into the desert where their death from starvation and thirst was to be certain; Trotha argued that there was no need to make exceptions for Herero women and children, since these would "infect German troops with their diseases", the insurrection Trotha explained "is and remains the beginning of a racial struggle". After the war, Trotha argued that his orders were necessary, writing in 1909 that "If I had made the small water holes accessible to the womenfolk, I would run the risk of an African catastrophe comparable to the Battle of Beresonia."

The German general staff was aware of the atrocities that were taking place; its official publication, named ''Der Kampf'', noted that:

Alfred von Schlieffen

Graf Alfred von Schlieffen, generally called Count Schlieffen (; 28 February 1833 – 4 January 1913) was a German field marshal and strategist who served as chief of the Imperial German General Staff from 1891 to 1906. His name lived on in the ...

(Chief of the Imperial German General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (german: Großer Generalstab), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the German Army, responsible for the continuou ...

) approved of Trotha's intentions in terms of a "racial struggle" and the need to "wipe out the entire nation or to drive them out of the country", but had doubts about his strategy, preferring their surrender.

Governor Leutwein, later relieved of his duties, complained to Chancellor von Bülow about Trotha's actions, seeing the general's orders as intruding upon the civilian colonial jurisdiction and ruining any chance of a political settlement. According to Professor Mahmood Mamdani

Mahmood Mamdani, FBA (born 23 April 1946) is an Indian-born Ugandan academic, author, and political commentator. He currently serves as the Chancellor of Kampala International University, Uganda. He was the director of the Makerere Institute o ...

from Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

, opposition to the policy of annihilation was largely the consequence of the fact that colonial officials looked at the Herero people as a potential source of labour, and thus economically important. For instance, Governor Leutwein wrote that:

Having no authority over the military, Chancellor Bülow could only advise Emperor Wilhelm II that Trotha's actions were "contrary to Christian and humanitarian principle, economically devastating and damaging to Germany's international reputation".

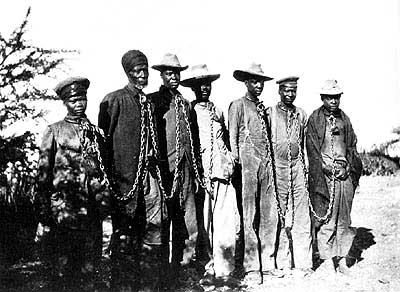

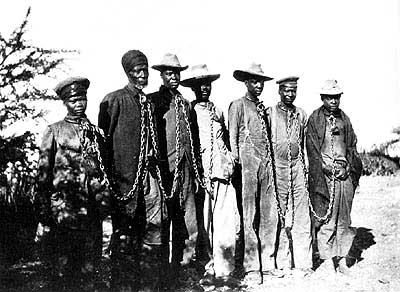

Upon the arrival of new orders at the end of 1904, prisoners were herded into labor camps

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (espec ...

, where they were given to private companies as slave labourers or exploited as human guinea pigs in medical experiments.

Concentration camps

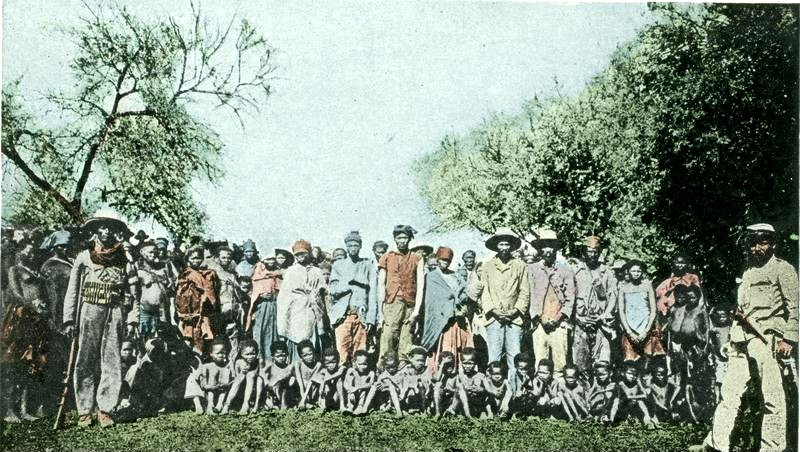

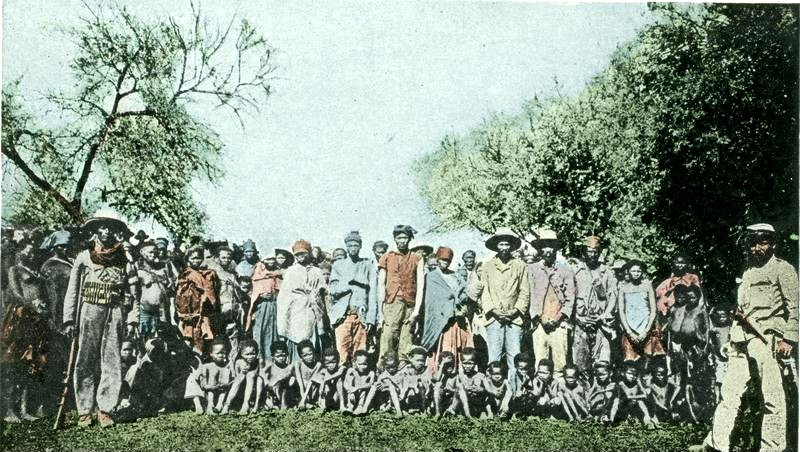

Survivors of the massacre, the majority of whom were women and children, were eventually put in places like

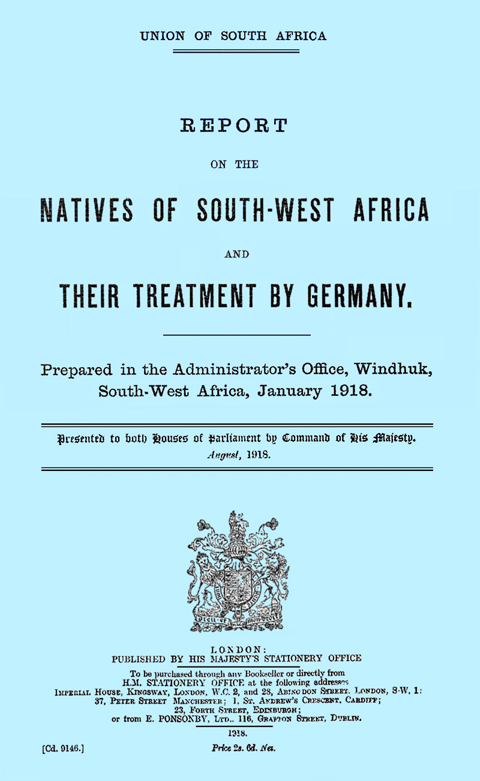

Survivors of the massacre, the majority of whom were women and children, were eventually put in places like Shark Island concentration camp

Shark Island or "Death Island" was one of five concentration camps in German South West Africa. It was located on Shark Island off Lüderitz, in the far south-west of the territory which today is Namibia. It was used by the German Empire during ...

, where the German authorities forced them to work as slave labour for German military and settlers. All prisoners were categorised into groups fit and unfit for work, and pre-printed death certificates indicating "death by exhaustion following privation" were issued. The British government published their well-known account of the German genocide of the Nama and Herero peoples in 1918.

Many Herero and Nama died of disease, exhaustion, starvation and malnutrition. Estimates of the mortality rate at the camps are between 45%Clarence Lusane (2002) ''Hitler's Black Victims: The Historical Experiences of European Blacks, Africans and African Americans During the Nazi Era'' (Crosscurrents in African American History), pp. 50–51, Routledge, New York and 74%.

Food in the camps was extremely scarce, consisting of rice with no additions.Aparna Rao (2007''The Practice of War: Production, Reproduction and Communication of Armed violence''

Berghahn Books

Berghahn Books is a New York and Oxford-based publisher

Publishing is the activity of making information, literature, music, software and other content available to the public for sale or for free. Traditionally, the term refers to the creat ...

As the prisoners lacked pots and the rice they received was uncooked, it was indigestible; horses and oxen that died in the camp were later distributed to the inmates as food. Dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

and lung diseases were common. Despite those conditions, the prisoners were taken outside the camp every day for labour under harsh treatment by the German guards, while the sick were left without any medical assistance or nursing care. Many Herero and Nama were worked to death.

Shootings, hangings, beatings, and other harsh treatment of the forced labourers (including use of sjambok

The sjambok () or litupa is a heavy leather whip. It is traditionally made from an adult hippopotamus or rhinoceros hide, but is also commonly made out of plastic.

A strip of the animal's hide is cut and carved into a strip long, tapering from ...

s) were common. A 28 September 1905 article in the South African newspaper ''Cape Argus

The ''Cape Argus'' is a daily newspaper co-founded in 1857 by Saul Solomon and published by Sekunjalo in Cape Town, South Africa. It is commonly referred to as ''The Argus''.

Although not the first English-language newspaper in South Africa ...

'' detailed some of the abuse with the heading: "In German S. W. Africa: Further Startling Allegations: Horrible Cruelty". In an interview with Percival Griffith, "an accountant of profession, who owing to hard times, took up on transport work at Angra Pequena

Angra may refer to:

Places

* Bay of Angra (Baía de Angra), within Angra do Heroísmo on the Portuguese island of Terceira in the archipelago of the Azores

* Angra do Heroísmo, a municipality in the Azores, Portugal

* Angra dos Reis, a municipali ...

, Lüderitz

Lüderitz is a town in the ǁKaras Region of southern Namibia. It lies on one of the least hospitable coasts in Africa. It is a port developed around Robert Harbour and Shark Island.

The town is known for its colonial architecture, includi ...

", related his experiences:

During the war, a number of people from the Cape

A cape is a clothing accessory or a sleeveless outer garment which drapes the wearer's back, arms, and chest, and connects at the neck.

History

Capes were common in medieval Europe, especially when combined with a hood in the chaperon. Th ...

(in modern-day South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

) sought employment as transport riders for German troops in Namibia. Upon their return to the Cape, some of these people recounted their stories, including those of the imprisonment and genocide of the Herero and Nama people. Fred Cornell, an aspiring British diamond prospector, was in Lüderitz when the Shark Island concentration camp was being used. Cornell wrote of the camp:

Shark Island was the most brutal of the German South West African camps. Lüderitz lies in southern Namibia, flanked by desert and ocean. In the harbour lies Shark Island, which then was connected to the mainland only by a small causeway. The island is now, as it was then, barren and characterised by solid rock carved into surreal formations by the hard ocean winds. The camp was placed on the far end of the relatively small island, where the prisoners would have suffered complete exposure to the strong winds that sweep Lüderitz for most of the year.

German Commander Ludwig von Estorff

Ludwig Gustav Adolf von Estorff (25 December 1859 – 5 October 1943) was a German military officer who notably served as a Schutztruppe commander in Africa; and later as an Imperial German Army general in World War I. He also was a recipien ...

wrote in a report that approximately 1,700 prisoners (including 1,203 Nama) had died by April 1907. In December 1906, four months after their arrival, 291 Nama died (a rate of more than nine people per day). Missionary reports put the death rate at 12–18 per day; as many as 80% of the prisoners sent to Shark Island eventually died there.News Monitor for September 2001Prevent Genocide International There are accusations of Herero women being coerced into sex slavery as a means of survival. Trotha was opposed to contact between natives and settlers, believing that the insurrection was "the beginning of a racial struggle" and fearing that the colonists would be infected by native diseases. Benjamin Madley argues that although Shark Island is referred to as a concentration camp, it functioned as an extermination camp or death camp.

Medical experiments and scientific racism

Prisoners were used for medical experiments and their illnesses or their recoveries from them were used for research. Experiments on live prisoners were performed by Dr. Bofinger, who injected Herero who were suffering fromscurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

with various substances including arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, but ...

and opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

; afterwards he researched the effects of these substances via autopsy.

Experimentation with the dead body parts of the prisoners was rife. Zoologist (1872–1955) noted taking "body parts from fresh native corpses" which according to him was a "welcome addition", and he also noted that he could use prisoners for that purpose.

An estimated 300 skulls were sent to Germany for experimentation, in part from concentration camp prisoners. In October 2011, after three years of talks, the first 20 of an estimated 300 skulls stored in the museum of the Charité

The Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin (Charité – Berlin University of Medicine) is one of Europe's largest university hospitals, affiliated with Humboldt University and Free University Berlin. With numerous Collaborative Research Cen ...

were returned to Namibia for burial. In 2014, 14 additional skulls were repatriated by the University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially german: Uni Freiburg), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (german: Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg), is a public university, public research university located in Freiburg im Breisg ...

.

Number of victims

A census conducted in 1905 revealed that 25,000 Herero remained inGerman South West Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

.Frank Robert Chalk, Kurt Jonassohn (1990''The History and Sociology of Genocide : Analyses and Case Studies''

Montreal Institute for Genocide Studies,

Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day, and became an official department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and operationally autonomous.

, Yale Universi ...

1990

According to the Whitaker Report, the population of 80,000 Herero was reduced to 15,000 "starving refugees" between 1904 and 1907. In ''Colonial Genocide and Reparations Claims in the 21st Century'': ''The Socio-Legal Context of Claims under International Law by the Herero against Germany for Genocide in Namibia'' by Jeremy Sarkin-Hughes, a number of 100,000 victims is given. Up to 80% of the indigenous populations were killed.

Newspapers reported 65,000 victims when announcing that Germany recognized the genocide in 2004.

Newspapers reported 65,000 victims when announcing that Germany recognized the genocide in 2004.

Aftermath

With the closure of concentration camps, all surviving Herero were distributed as labourers for settlers in the German colony. From that time on, all Herero over the age of seven were forced to wear a metal disc with their labour registration number, and banned from owning land or cattle, a necessity for pastoral society.

About 19,000 German troops were engaged in the conflict, of which 3,000 saw combat. The rest were used for upkeep and administration. The German losses were 676 soldiers killed in combat, 76 missing, and 689 dead from disease. The Reiterdenkmal ( en, Equestrian Monument) in Windhoek was erected in 1912 to celebrate the victory and to remember the fallen German soldiers and civilians. Until after Independence, no monument was built to the killed indigenous population. It remains a bone of contention in independent Namibia.

The campaign cost Germany 600 million

With the closure of concentration camps, all surviving Herero were distributed as labourers for settlers in the German colony. From that time on, all Herero over the age of seven were forced to wear a metal disc with their labour registration number, and banned from owning land or cattle, a necessity for pastoral society.

About 19,000 German troops were engaged in the conflict, of which 3,000 saw combat. The rest were used for upkeep and administration. The German losses were 676 soldiers killed in combat, 76 missing, and 689 dead from disease. The Reiterdenkmal ( en, Equestrian Monument) in Windhoek was erected in 1912 to celebrate the victory and to remember the fallen German soldiers and civilians. Until after Independence, no monument was built to the killed indigenous population. It remains a bone of contention in independent Namibia.

The campaign cost Germany 600 million marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks, trademarks owned by an organisation for the benefit of its members

* Marks & Co, the inspiration for the novel '' ...

. The normal annual subsidy to the colony was 14.5 million marks. In 1908, diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the Chemical stability, chemically stable form of car ...

s were discovered in the territory, and this did much to boost its prosperity, though it was short-lived.

In 1915, during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the German colony was taken over and occupied by the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Trans ...

, which was victorious in the South West Africa campaign

The South West Africa campaign was the conquest and occupation of German South West Africa by forces from the Union of South Africa acting on behalf of the British imperial government at the beginning of the First World War.

Background

The ...

. South Africa received a League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

over South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

on 17 December 1920.

Link between the Herero genocide and the Holocaust

The Herero genocide has commanded the attention of historians who study complex issues of continuity between the Herero genocide andThe Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

. It is argued that the Herero genocide set a precedent in Imperial Germany that would later be followed by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

's establishment of death camps

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

.

According to Benjamin Madley, the German experience in South West Africa was a crucial precursor to Nazi colonialism and genocide. He argues that personal connections, literature, and public debates served as conduits for communicating colonialist and genocidal ideas and methods from the colony to Germany. Tony Barta, an honorary research associate at La Trobe University

La Trobe University is a public research university based in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Its main campus is located in the suburb of Bundoora. The university was established in 1964, becoming the third university in the state of Victoria an ...

, argues that the Herero genocide was an inspiration for Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

in his war against the Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

, Romani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnicities

* Romani people, an ethnic group of Northern Indian origin, living dispersed in Europe, the Americas and Asia

** Romani genocide, under Nazi rule

* Romani language, any of several Indo-Aryan languages of the Roma ...

, and others who he described as "non-Aryans

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ' ...

".

According to Clarence Lusane

Clarence Lusane (born 1953) is an American author, activist, lecturer and freelance journalist. His most recent major work is his book '' The Black History of the White House''.

Background

Clarence Lusane received his Ph.D. in political science ...

, Eugen Fischer

Eugen Fischer (5 July 1874 – 9 July 1967) was a German professor of medicine, anthropology, and eugenics, and a member of the Nazi Party. He served as director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, ...

's medical experiments can be seen as a testing ground for medical procedures which were later followed during the Nazi Holocaust. Fischer later became chancellor of the University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative o ...

, where he taught medicine to Nazi physicians. Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer

Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer (16 July 1896 – 8 August 1969) was a German human biologist and geneticist, who was the Professor of Human Genetics at the University of Münster until he retired in 1965. A member of the Dutch noble Verschuer fa ...

was a student of Fischer, Verschuer himself had a prominent pupil, Josef Mengele

, allegiance =

, branch = Schutzstaffel

, serviceyears = 1938–1945

, rank = ''Schutzstaffel, SS''-''Hauptsturmführer'' (Captain)

, servicenumber =

, battles =

, unit =

, awards =

, command ...

. Franz Ritter von Epp

Franz Ritter von Epp (born Franz Epp; from 1918 as Ritter von Epp; 16 October 1868 – 31 January 1947)Lilla, Joachim: Epp, Franz Ritter v.'. In: Staatsminister, leitende Verwaltungsbeamte und (NS-)Funktionsträger in Bayern 1918 bis 19 ...

, who was later responsible for the liquidation of virtually all Bavarian Jews and Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

Places Australia

* Roma, Queensland, a town

** Roma Airport

** Roma Courthouse

** Electoral district of Roma, defunct

** Town of Roma, defunct town, now part of the Maranoa Regional Council

*Roma Street, Brisbane, a ...

as governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

, took part in the Herero and Nama genocide as well. Historians Robert Gerwarth

Robert Gerwarth (born 12 February 1976) is a German historian and author who specialises in European history, with an emphasis on German history. Since finishing a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of Oxford, he has held ...

and Stephan Malinowski have criticized this claim, asserting that Von Epp exercised no influence in Nazi extermination policies.

Mahmood Mamdani

Mahmood Mamdani, FBA (born 23 April 1946) is an Indian-born Ugandan academic, author, and political commentator. He currently serves as the Chancellor of Kampala International University, Uganda. He was the director of the Makerere Institute o ...

argues that the links between the Herero genocide and the Holocaust are beyond the execution of an annihilation policy and the establishment of concentration camps and there are also ideological similarities in the conduct of both genocides. Focusing on a written statement by General Trotha which is translated as:

Mamdani takes note of the similarity between the aims of the General and the Nazis. According to Mamdani, in both cases there was a Social Darwinist

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in W ...

notion of "cleansing", after which "something new" would "emerge".

Robert Gerwarth and Stephan Malinowski have questioned the supposed link with the Holocaust, finding it to be lacking in empirical evidence, and argue that Nazi policy represented a distinct turn away from typical European colonial practice. Additionally, they write that studies supporting the link completely ignore the influences of World War I, the German Revolution

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

, and the activities of the Friekorps in the inurement of extreme violence as a method in the German political conciousness.

Patrick Bernhard writes that the Nazis, including Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

, explicitly rejected the colonial experience of the German Empire as an "appallingly outdated" model; when they did draw inspiration from colonialism for Generalplan Ost

The ''Generalplan Ost'' (; en, Master Plan for the East), abbreviated GPO, was the Nazi German government's plan for the genocide and ethnic cleansing on a vast scale, and colonization of Central and Eastern Europe by Germans. It was to be un ...

, it was from the contemporary work of Italian fascists such as Giuseppe Tassinari in Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

, which they viewed as a shining example of fascist modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular socio-cultural norm (social), norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the Renaissancein the " ...

.

Reconciliation

Recognition

In 1985, the United Nations' Whitaker Report classified the massacres as an attempt to exterminate the Herero and Nama peoples ofSouth West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

, and therefore one of the earliest cases of genocide in the 20th century.

In 1998, German President

In 1998, German President Roman Herzog

Roman Herzog (; 5 April 1934 – 10 January 2017) was a German politician, judge and legal scholar, who served as the president of Germany from 1994 to 1999. A member of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), he was the first president to be elec ...

visited Namibia and met Herero leaders. Chief Munjuku Nguvauva demanded a public apology and compensation. Herzog expressed regret but stopped short of an apology. He pointed out that international law requiring reparation did not exist in 1907, but he undertook to take the Herero petition back to the German government.

On 16 August 2004, at the 100th anniversary of the start of the genocide, a member of the German government, Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul

Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul (born 21 November 1942) is a German politician and a member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) since 1965.

Early life and career

Wieczorek-Zeul (pronounced ''VEE‐choreck TSOIL'') began her career as a teacher 1965� ...

, Germany's Federal Minister for Economic Development and Cooperation, officially apologised and expressed grief about the genocide, declaring in a speech that:

She ruled out paying special compensations, but promised continued economic aid for Namibia which in 2004 amounted to $14M a year. This number has been significantly increased since then, with the budget for the years 2016–17 allocating a sum total of €138M in monetary support payments.

The Trotha family travelled to Omaruru in October 2007 by invitation of the royal Herero chiefs and publicly apologised for the actions of their relative. Wolf-Thilo von Trotha said:

Negotiations and agreement

The Herero filed a lawsuit in the United States in 2001 demanding reparations from the German government andDeutsche Bank

Deutsche Bank AG (), sometimes referred to simply as Deutsche, is a German multinational investment bank and financial services company headquartered in Frankfurt, Germany, and dual-listed on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange and the New York Sto ...

, which financed the German government and companies in Southern Africa. With a complaint filed with the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York

The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (in case citations, S.D.N.Y.) is a United States district court, federal trial court whose geographic jurisdiction encompasses eight counties of New York (state), New York ...

in January 2017, descendants of the Herero and Nama people sued Germany for damages in the United States. The plaintiffs sued under the Alien Tort Statute

The Alien Tort Statute ( codified in 1948 as ; ATS), also called the Alien Tort Claims Act (ATCA), is a section in the United States Code that gives federal courts jurisdiction over lawsuits filed by foreign nationals for torts committed in viola ...

, a 1789 U.S. law often invoked in human rights

Human rights are Morality, moral principles or Social norm, normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for ce ...

cases. Their proposed class-action lawsuit sought unspecified sums for thousands of descendants of the victims, for the "incalculable damages" that were caused. Germany seeks to rely on its state immunity

The doctrine and rules of state immunity concern the protection which a state is given from being sued in the courts of other states. The rules relate to legal proceedings in the courts of another state, not in a state's own courts. The rules devel ...

as implemented in US law as the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act

The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 (FSIA) is a United States law, codified at Title 28, §§ 1330, 1332, 1391(f), 1441(d), and 1602–1611 of the United States Code, that established criteria as to whether a foreign sovereign nation ( ...

, arguing that, as a sovereign nation, it cannot be sued in US courts in relation to its acts outside the United States. In March 2019, the judge dismissed the claims due to the exceptions to sovereign immunity being too narrow for the case.

In September 2020, the Second Circuit