Herbert Vivian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

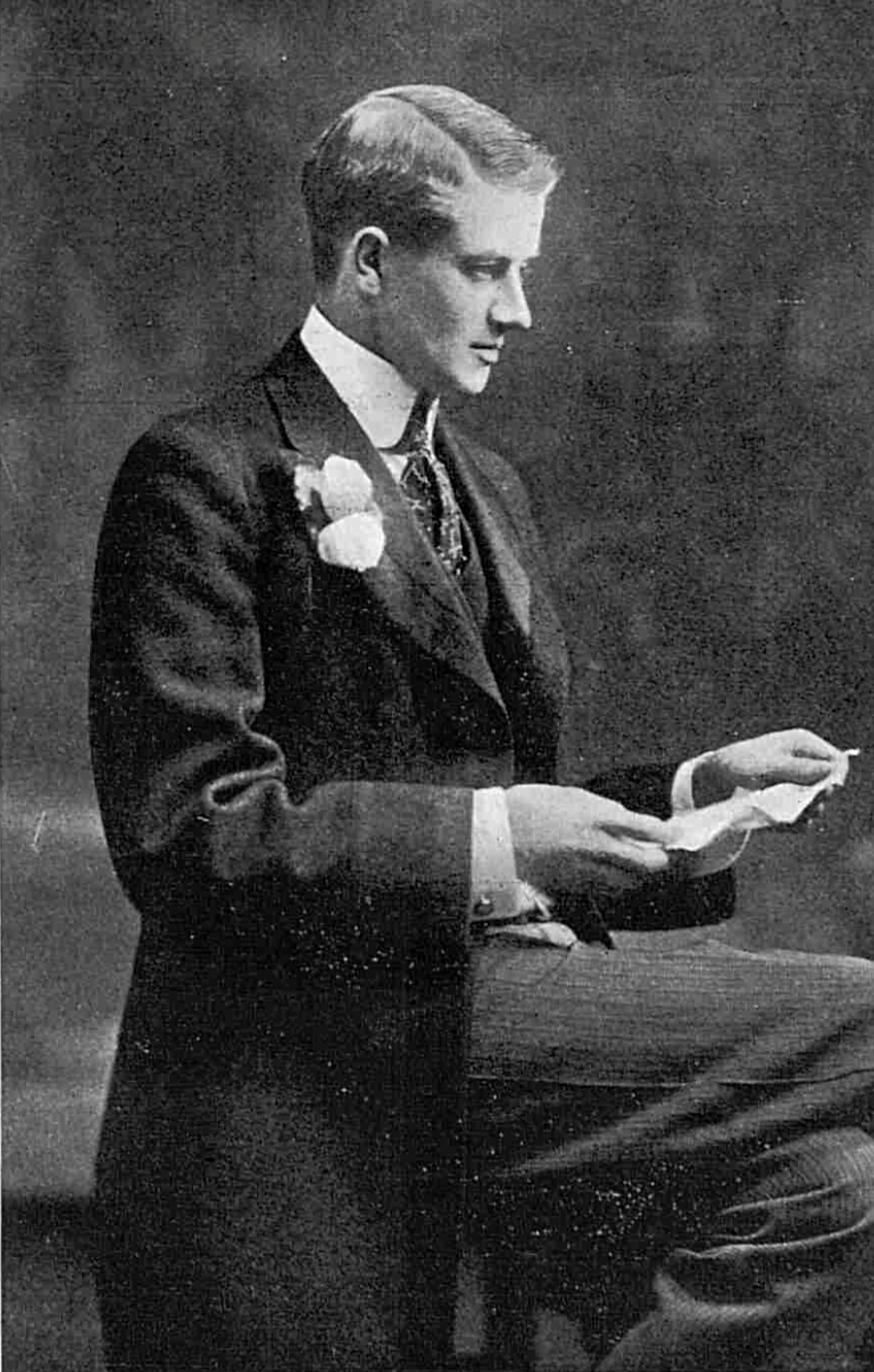

Herbert Vivian (3 April 1865 – 18 April 1940) was an English journalist, author and newspaper owner, who befriended

The late 1880s and 1890s brought a

The late 1880s and 1890s brought a

After his departure from the Jacobite League in 1893, Vivian became travel correspondent of Arthur Pearson's paper ''

After his departure from the Jacobite League in 1893, Vivian became travel correspondent of Arthur Pearson's paper '' In 1903, Vivian returned to the subject of Serbia in "The Servian Character" for the ''

In 1903, Vivian returned to the subject of Serbia in "The Servian Character" for the '' Vivian continued to publish books in the

Vivian continued to publish books in the

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* (published under a pseudonym)

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

The following books are commonly attributed to Vivian, but at least one source gives Wilfrid Keppel Honnywill as the author.

* (published anonymously)

* (published anonymously)

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* (published under a pseudonym)

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

The following books are commonly attributed to Vivian, but at least one source gives Wilfrid Keppel Honnywill as the author.

* (published anonymously)

* (published anonymously)

Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill (13 February 1849 – 24 January 1895) was a British statesman. Churchill was a Tory radical and coined the term 'Tory democracy'. He inspired a generation of party managers, created the National Union of ...

, Charles Russell, Leopold Maxse

Leopold "Leo" James Maxse (11 November 1864 – 22 January 1932) was an English amateur tennis player and journalist and editor of the conservative British publication, ''National Review'', between August 1893 and his death in January 1932; he ...

and others in the 1880s. He campaigned for Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the e ...

and was private secretary to Wilfrid Blunt

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (17 August 1840 – 10 September 1922), sometimes spelt Wilfred, was an English poet and writer. He and his wife Lady Anne Blunt travelled in the Middle East and were instrumental in preserving the Arabian horse bloodline ...

, poet and writer, who stood in the 1888 Deptford by-election. Vivian's writings caused a rift between Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

and James NcNeil Whistler. In the 1890s, Vivian was a leader of the Neo-Jacobite Revival

The Neo-Jacobite Revival was a political movement that took place during the 25 years before the First World War in the United Kingdom. The movement was monarchist, and had the specific aim of replacing British parliamentary democracy with a restor ...

, a monarchist movement keen to restore a Stuart to the British throne and replace the parliamentary system. Before the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

he was friends with Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

and was the first journalist to interview him. Vivian lost as Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

candidate for Deptford in 1906. As an extreme monarchist throughout his life, he became in the 1920s a supporter of fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

. His several books included the novel ''The Green Bay Tree'' with William Henry Wilkins

William Henry Wilkins (1860–1905) was an English writer, best known as a royal biographer and campaigner for immigration controls. He used the pseudonym W. H. de Winton.

Life

Born at Compton Martin, Somerset, on 23 December 1860, he was son o ...

. He was a noted Serbophile; his writings on the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

remain influential.

Early life and education

Herbert Vivian was born on 3 April 1865 inChichester

Chichester () is a cathedral city and civil parish in West Sussex, England.OS Explorer map 120: Chichester, South Harting and Selsey Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton B2 edition. Publishing Date:2009. It is the only ci ...

, the only son of the Reverend Francis Henry and Margaret Vivian. He was baptised by his father on 11 May 1865 at the town's Church of St Peter the Great. He had a sister, Margaret Cordelia Vivian. His grandfather John Vivian was the Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

MP for Truro

Truro (; kw, Truru) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parishes in England, civil parish in Cornwall, England. It is Cornwall's county town, sole city and centre for administration, leisure and retail trading. Its ...

, and owned Pencalenick House in St Clement, Cornwall; Herbert recalled shooting his first rabbit there as a child. He always glossed over his grandfather's political role, for example, writing: "None of my immediate relatives have ever troubled their heads in politics..." in his newspaper ''The Whirlwind''.

Herbert studied at Harrow School

(The Faithful Dispensation of the Gifts of God)

, established = (Royal Charter)

, closed =

, type = Public schoolIndependent schoolBoarding school

, religion = Church of E ...

from 1879 until 1883. When he was 14, he was introduced to an old friend of his father's, Thomas Hughes

Thomas Hughes (20 October 182222 March 1896) was an English lawyer, judge, politician and author. He is most famous for his novel ''Tom Brown's School Days'' (1857), a semi-autobiographical work set at Rugby School, which Hughes had attended. ...

, the author of ''Tom Brown's School Days

''Tom Brown's School Days'' (sometimes written ''Tom Brown's Schooldays'', also published under the titles ''Tom Brown at Rugby'', ''School Days at Rugby'', and ''Tom Brown's School Days at Rugby'') is an 1857 novel by Thomas Hughes. The stor ...

''. The meeting had a strong impact on the young Vivian, who wrote about it later in his memoirs. In 1881, his grandfather introduced him to Thomas Bayley Potter

Thomas Bayley Potter DL, JP (29 November 1817 – 6 November 1898) was an English merchant in Manchester and Liberal Party politician.

Early life

Born in Polefield, Lancashire, he was the second son of Sir Thomas Potter and his wife Esther ...

, the Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

for Rochdale

Rochdale ( ) is a large town in Greater Manchester, England, at the foothills of the South Pennines in the dale on the River Roch, northwest of Oldham and northeast of Manchester. It is the administrative centre of the Metropolitan Borough ...

. Potter was impressed by Vivian and often took him into Parliament during his holidays. There Vivian met many of the MPs and was particularly impressed by Charles Warton

Charles Nicholas Warton (1832 – 31 July 1900) was a barrister and politician who sat in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom as a Conservative from 1880 to 1885. In 1886, he was appointed Attorney-General of Western Australia.

Biograph ...

, the MP for Bridport

Bridport is a market town in Dorset, England, inland from the English Channel near the confluence of the River Brit and its tributary the Asker. Its origins are Saxon and it has a long history as a rope-making centre. On the coast and wit ...

. Potter also introduced him to Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill (13 February 1849 – 24 January 1895) was a British statesman. Churchill was a Tory radical and coined the term 'Tory democracy'. He inspired a generation of party managers, created the National Union of ...

, who inspired Vivian to take up Tory democracy

One-nation conservatism, also known as one-nationism or Tory democracy, is a paternalistic form of British political conservatism. It advocates the preservation of established institutions and traditional principles within a political democr ...

. Vivian exchanged letters with Lord Randolph during his school days and continued to correspond with him for many years afterwards. Vivian later became friends with his son, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

.

Vivian studied at Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by Henry VIII, King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge ...

, graduating in 1886 with a degree

Degree may refer to:

As a unit of measurement

* Degree (angle), a unit of angle measurement

** Degree of geographical latitude

** Degree of geographical longitude

* Degree symbol (°), a notation used in science, engineering, and mathematics

...

in history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

and subsequently being promoted to a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

. In his student years, Vivian and his friend Edward Goulding were the President and Vice-President respectively of the University Carlton Club and invited Lord Randolph to become its President. Never shy of using his connections, Vivian dropped Churchill's name to arrange a meeting in Vevey

Vevey (; frp, Vevê; german: label=former German, Vivis) is a town in Switzerland in the canton of Vaud, on the north shore of Lake Geneva, near Lausanne. The German name Vivis is no longer commonly used.

It was the seat of the district of ...

with Nubar Pasha, the first Prime Minister of Egypt

The prime minister of Egypt () is the head of the Egyptian government. A direct translation of the Arabic-language title is "Minister-President of Egypt" and "President of the Government". The Arabic title can also be translated as "President of ...

. After spending several hours discussing politics with Pasha, he returned to London and reported his conversation to Churchill. Churchill introduced Vivian to Charles Russell, who later became Baron Russell of Killowen and the Lord Chief Justice of England

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or a ...

, and the two became friends. Around 1882, Vivian attended a lecture given by Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

at which James NcNeil Whistler was also present and which Vivian would later write about .

At Cambridge, Vivian struck up friendships with students who went on to be prominent politicians and businessmen. Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

was involved in Cambridge Union

The Cambridge Union Society, also known as the Cambridge Union, is a debating and free speech society in Cambridge, England, and the largest society in the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1815, it is the oldest continuously running debati ...

politics when Vivian arrived and the two bonded over a shared interest in Radicalism. He was a close friend of Leopold Maxse

Leopold "Leo" James Maxse (11 November 1864 – 22 January 1932) was an English amateur tennis player and journalist and editor of the conservative British publication, ''National Review'', between August 1893 and his death in January 1932; he ...

— later editor of the ''National Review''. Another friend was Ernest Debenham

Sir Ernest Ridley Debenham, 1st Baronet (26 May 1865 – 25 December 1952), was an English businessman. He was responsible for the considerable expansion of the family's retail and wholesale drapery firm between 1892 and 1927.

Biography

Born at ...

, who went on to lead the family business Debenhams

Debenhams plc was a British department store chain operating in the United Kingdom, Denmark and the Republic of Ireland. It was founded in 1778 as a single store in London and grew to 178 locations across those countries, also owning the Danish ...

to great commercial success. Vivian recalled Debenham overdosing on hashish

Hashish ( ar, حشيش, ()), also known as hash, "dry herb, hay" is a drug made by compressing and processing parts of the cannabis plant, typically focusing on flowering buds (female flowers) containing the most trichomes. European Monitorin ...

during experiments in Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

at Cambridge.

Private secretary to Wilfrid Blunt

Vivian and Chamberlain organised speaking events at the Union. In 1886, they invited the English anti-imperialist writer and poetWilfrid Scawen Blunt

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (17 August 1840 – 10 September 1922), sometimes spelt Wilfred, was an English poet and writer. He and his wife Lady Anne Blunt travelled in the Middle East and were instrumental in preserving the Arabian horse bloodlines ...

to speak on the subject of Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the e ...

, and Vivian and Blunt became friends. Later that year, Vivian visited Blunt at his home, Crabbet Park, and took a position as his private secretary. Vivian spent most weekends at Crabbet during his final year of studies, and continued to work for Blunt after he graduated. While so employed, he met influential politicians, as Blunt prepared to stand for Parliament, among them the Anglo-French historian Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (, ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a Franco-English writer and historian of the early twentieth century. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. H ...

. Blunt was a cousin of Lord Alfred Douglas

Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas (22 October 1870 – 20 March 1945), also known as Bosie Douglas, was an English poet and journalist, and a lover of Oscar Wilde. At Oxford he edited an undergraduate journal, ''The Spirit Lamp'', that carried a homoer ...

and a friend of Oscar Wilde.

In 1887 Blunt became more vociferously in favour of Irish Home Rule. In November, Lord Randolph wrote to Vivian advising him to distance himself from Blunt, advice Vivian did not take. At the time, Blunt was also developing interest in the Jacobite cause of restoring the House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter fi ...

to the British throne, which Vivian was to become a passion in his life.

In late 1887, Vivian left the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

and joined the Home Rule Union between the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

and the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish national ...

. At the end of the year, he toured Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

with the leading Irish politician Michael Davitt

Michael Davitt (25 March 184630 May 1906) was an Irish republican activist for a variety of causes, especially Home Rule and land reform. Following an eviction when he was four years old, Davitt's family migrated to England. He began his caree ...

and Bradford Central MP George Shaw-Lefevre. Shortly after Vivian returned from Ireland he met the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1875 to 1891, also acting as Leader of the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882 and then Leader of the ...

and then the MP for East Mayo, John Dillon

John Dillon (4 September 1851 – 4 August 1927) was an Irish politician from Dublin, who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for over 35 years and was the last leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. By political disposition Dillon was an a ...

. In October 1887, Blunt gave a speech at a meeting in Woodford, County Galway

Woodford () is a village in the south-east of County Galway, Ireland. It is situated between the River Shannon and the Slieve Aughty mountains.

History

The village's industrial history is indicated by a variant of its Irish name, ''Gráig na ...

protesting against mass evictions of tenant families. The meeting had been banned by Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As F ...

, the Chief Secretary for Ireland and Blunt was arrested, tried and imprisoned. While Blunt served his sentence in Dublin, Vivian worked closely with William John Evelyn to promote Blunt in the February 1888 Deptford by-election, caused by Evelyn's resignation as the Conservative MP. Blunt lost by 275 votes. Despite this, Blunt and Vivian were approached in March 1888 by a committee from Parnell's Irish National League

The Irish National League (INL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland. It was founded on 17 October 1882 by Charles Stewart Parnell as the successor to the Irish National Land League after this was suppressed. Whereas the Land League ...

, asking Blunt to stand as their candidate for Deptford at the next general election, but by the time the election was called in 1892, Blunt's enthusiasms had moved on.

For a while, Vivian contributed to Evelyn's ''Abinger Monthly Record'', a magazine he later described as " npart... really scurrilous attacks on the Vicar". The Vicar was Rev. T. P. Hill, incumbent of Abinger, who had fallen out with Evelyn. The ''Record'' was also noted for a campaign against compulsory vaccinations and support of Irish Home Rule.

Oscar Wilde

In the late 1880s, Vivian was a friend of Oscar Wilde; they dined together on several occasions. At one such dinner, Vivian claimed he witnessed a famous exchange between Wilde and James NcNeill Whistler. Whistler said a ''bon mot'' that Wilde found particularly witty, Wilde exclaimed that he wished that he had said it, and Whistler retorted, "You will, Oscar, you will". In 1889, Vivian included this anecdote in an article, "The Reminiscences of a Short Life", which appeared in ''The Sun'' and implied that Wilde had a habit of passing off other people's witticisms as his own, especially Whistler's. Wilde saw Vivian's article as a scurrilous betrayal and it directly caused the break in friendship between Wilde and Whistler. "The Reminiscences" also caused acrimony between Wilde and Vivian, Wilde accusing him of "the inaccuracy of an eavesdropper with the method of a blackmailer" and banishing him from his circle. After the incident, Vivian and Whistler became friends, exchanging letters for many years.Newspaper publishing and the Neo-Jacobite Revival

The late 1880s and 1890s brought a

The late 1880s and 1890s brought a Neo-Jacobite Revival

The Neo-Jacobite Revival was a political movement that took place during the 25 years before the First World War in the United Kingdom. The movement was monarchist, and had the specific aim of replacing British parliamentary democracy with a restor ...

in Britain. In 1886, Bertram Ashburnham founded the Order of the White Rose

The Order of the White Rose of Finland ( fi, Suomen Valkoisen Ruusun ritarikunta; sv, Finlands Vita Ros’ orden) is one of three official orders in Finland, along with the Order of the Cross of Liberty, and the Order of the Lion of Finland. T ...

, which embraced causes such as Irish, Cornish, Scottish and Welsh independence, Spanish and Italian legitimism

The Legitimists (french: Légitimistes) are royalists who adhere to the rights of dynastic succession to the French crown of the descendants of the eldest branch of the Bourbon dynasty, which was overthrown in the 1830 July Revolution. They r ...

, and particularly Jacobitism. Its members included Frederick Lee, Henry Jenner

Henry Jenner (8 August 1848 – 8 May 1934) was a British scholar of the Celtic languages, a Cornish cultural activist, and the chief originator of the Cornish language revival.

Jenner was born at St Columb Major on 8 August 1848. He was th ...

, Whistler, Robert Edward Francillon, Charles Augustus Howell

Charles Augustus Howell (10 March 1840 – 21 April 1890) was an art dealer and alleged blackmailer who is best known for persuading the poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti to dig up the poems he buried with his wife Elizabeth Siddal. His reputation as ...

, Stuart Richard Erskine and Vivian. It published a paper, ''The Royalist'', from 1890 to 1903.

Vivian first met Erskine when they were at a journalism school together. In 1890, the two founded a weekly newspaper '' The Whirlwind, A Lively and Eccentric Newspaper'' with Vivian as editor, noted for including illustrations by artists, including Whistler and Walter Sickert

Walter Richard Sickert (31 May 1860 – 22 January 1942) was a German-born British painter and printmaker who was a member of the Camden Town Group of Post-Impressionist artists in early 20th-century London. He was an important influence on d ...

. Sickert was also its art critic, and wrote a weekly column. It carried articles on Oscar Wilde at the height of his fame and notoriety. The paper espoused an individualist

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-relianc ...

, Jacobite political view, championed by Erskine and Vivian. One notable Sickert illustration for ''The Whirlwind'' was a portrait of Charles Bradlaugh

Charles Bradlaugh (; 26 September 1833 – 30 January 1891) was an English political activist and atheist. He founded the National Secular Society in 1866, 15 years after George Holyoake had coined the term "secularism" in 1851.

In 1880, Bradl ...

. Bradlaugh also wrote an article on "practical individualism" for the paper.

''The Whirlwind'' was scourged by Victor Yarros

Victor S. Yarros (1865–1956) was an American anarchist, lawyer and author. He immigrated to the United States with his friend Charles David Spivak in 1882. He was law partner to Clarence Darrow for eleven years in Chicago, husband to the femini ...

for its anti-Semitic stance, mainly espoused by Vivian in his editorials. In the 23 August 1890 edition, he wrote, "The Jews are a race rather than a religious body, and, like the Chinese, are often obnoxious to their neighbours. By their financial craft they have acquired a dangerously extensive power, not merely over individuals, but even over the policy of states.... The proper way to deal with Jews is a rigorous boycott... What should be aimed at is a return of the whole Jewish race, as speedily as may be, to Palestine... The countries of their adoption would assuredly have no difficulty in sparing them".

Vivian used his editorship to promote also an individualist philosophy for women, though he was against Women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

. Other causes included the menace of London's tramways and repeated attacks on the journalist and explorer Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author and politician who was famous for his exploration of Central Africa

Cen ...

and other figures of the age. He also published a series of autobiographical articles, ''Reminiscences of a Short Life'', which later formed the basis of his 1923 memoirs, ''Myself Not Least, being the personal reminiscences of "X."'' The paper went on hiatus in early 1891, when Vivian stood for election, and did not restart publication.

The Order of the White Rose split in 1891. It had been a primarily nostalgic, artistic organisation, but Vivian and Erskine wanted a more militant political agenda. With Melville Henry Massue

Melville Amadeus Henry Douglas Heddle de La Caillemotte de Massue de Ruvigné, "9th Marquis of Ruvigny and 15th of Raineval" (25 April 1868 – 6 October 1921) was a British genealogist and author, who was twice president of the Legitimist Jacobit ...

, styling himself the Marquis of Ruvigny, they founded a rival Legitimist Jacobite League of Great Britain and Ireland, sometimes using the name White Rose League. Its Central Executive Committee contained Walter Clifford Mellor

Colonel John James Mellor (12 August 1830 – 12 January 1916) was a British industrialist and Conservative politician.

Early life

Mellor was born in Oldham, Lancashire, and was educated privately.''New Members of Parliament'', The Times, 19 Ju ...

, Vivian, George G. Fraser, Massue, Baron Valdez of Valdez, Alfred John Rodway, and R. W. Fraser, with Erskine as President. Pittock called the League a "publicist for Jacobitism on a scale unwitnessed since the Eighteenth Century".

The League organised protests often centred on statues of Jacobite heroes. In late 1892, they applied for government permission to lay wreaths at the statue of Charles I at Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Clockwise from north these are: the east side of Trafalgar Square leading to St Martin's Place and then Charing Cross Road; the Strand leading to the City; ...

on the anniversary of his execution. This was denied by Prime Minister Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

and enforced by George Shaw-Lefevre, Vivian's one-time travelling companion and now First Commissioner of Works

The First Commissioner of Works and Public Buildings was a position within the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and subsequent to 1922, within the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Irel ...

. The League tried to lay the wreaths anyway on 30 January 1893. Police were sent to stop this, but after a confrontation, Vivian and other members were allowed to complete their moved, so gaining significant press coverage. The political reporter for the ''Lancashire Evening Post

The ''Lancashire Evening Post'' is a daily newspaper based in Fulwood, a suburb of the city of Preston, Lancashire, England. According to the British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom and is one of t ...

'' wrote, "Mr. Herbert Vivian has been successful at last in placing a wreath upon the Statue of Charles the First.... We trust all parties will feel the better for the operation — especially the bronze statue". An article in the ''Western Morning News

The ''Western Morning News'' is a daily regional newspaper founded in 1860, and covering the West Country including Devon, Cornwall, the Isles of Scilly and parts of Somerset and Dorset in the South West of England.

Organisation

The ''Western M ...

'' said, "A bold and daring man is Mr. Herbert Vivian, Jacobite and journalist.... He announces to all and sundry that, law or no law, he will... attempt to lay a wreath on the statue. I have not heard whether special precautions have yet been taken to cope with this new force of disorder though, perhaps... one constable may be set apart to overawe Mr. Herbert Vivian".

In June 1893 came a split between Ruvigny and Vivian, with Vivian seeking to continue the League with support from Viscount Dupplin, Mellor and others. Vivian left the Jacobite League in August 1893, but continued to promote a strongly Jacobite political philosophy.

In 1892 and 1893, Vivian worked as a journalist for William Ernest Henley

William Ernest Henley (23 August 184911 July 1903) was an English poet, writer, critic and editor. Though he wrote several books of poetry, Henley is remembered most often for his 1875 poem "Invictus". A fixture in London literary circles, the o ...

at the '' National Observer''. In 1894, he published ''The Green Bay Tree'' with a college friend, the anti-immigrant writer William Henry Wilkins

William Henry Wilkins (1860–1905) was an English writer, best known as a royal biographer and campaigner for immigration controls. He used the pseudonym W. H. de Winton.

Life

Born at Compton Martin, Somerset, on 23 December 1860, he was son o ...

. He also contributed to Wilkin's monthly periodical ''The Albemarle'', which was co-edited by a mutual Cambridge friend, Hubert Crackanthorpe

Hubert Montague Crackanthorpe (12 May 1870 – c. November 1896) was a late Victorian British writer who created works mainly in the genres of the essay, short story, and novella. He also wrote limited amounts of literary criticism. After dying ...

. He spent the winter of 1894/1895 in France, where he discussed Jacobite and Carlist

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty – one descended from Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855) – ...

politics with the poet François Coppée

François Edouard Joachim Coppée (26 January 1842 – 23 May 1908) was a French poet and novelist.

Biography

Coppée was born in Paris to a civil servant. After attending the Lycée Saint-Louis he became a clerk in the ministry of war and won ...

and contemporary literature with the novelist Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

.

Vivian continued his political journalism after ''The Whirlwind'' closed. In 1895, he was editor of ''The White Cockade'', a newspaper whose main purpose was to put forward the Jacobite argument. It received poor reviews and no success. Vivian was described in the ''Bristol Mercury'' as a "volatile young gentleman hoenjoys a European reputation in the spheres of politics and literature."

By 1897, Vivian was the President of the ''Legitimist Club'', another Neo-Jacobite organisation. In 1898, Vivian published letters he had exchanged with the Office of Works

The Office of Works was established in the England, English Royal Household, royal household in 1378 to oversee the building and maintenance of the royal castles and residences. In 1832 it became the Works Department forces within the Office of W ...

demanding that the Club be allowed to lay a wreath at the Statue of James II, Trafalgar Square on 16 September, the anniversary of James' death. Vivian's wreath-laying, tactics and use of the press to publicise his cause, remained the same. Vivian remained president of the Club until at least 1904.

Writing career

After his departure from the Jacobite League in 1893, Vivian became travel correspondent of Arthur Pearson's paper ''

After his departure from the Jacobite League in 1893, Vivian became travel correspondent of Arthur Pearson's paper ''Pearson's Weekly

''Pearson's Weekly'' was a British weekly periodical founded in London in 1890 by Arthur Pearson, who had previously worked on '' Tit-Bits'' for George Newnes.

The first issue was well advertised and sold a quarter of a million copies. The paper' ...

''. In February 1896, he launched and edited a new weekly called ''Give and Take'', which was noted for offering its readers coupons for "a selected set of tradesmen".

In 1898, Vivian returned to being a travel journalist, first for the ''Morning Post

''The Morning Post'' was a conservative daily newspaper published in London from 1772 to 1937, when it was acquired by ''The Daily Telegraph''.

History

The paper was founded by John Bell. According to historian Robert Darnton, ''The Morning Po ...

'' (1898–1899) and then for Pearson's newly-founded ''Daily Express

The ''Daily Express'' is a national daily United Kingdom middle-market newspaper printed in tabloid format. Published in London, it is the flagship of Express Newspapers, owned by publisher Reach plc. It was first published as a broadsheet i ...

'' (1899–1900). In 1901 and 1902, he produced a magazine called ''The Rambler'' with Richard Le Gallienne

Richard Le Gallienne (20 January 1866 – 15 September 1947) was an English author and poet. The British-American actress Eva Le Gallienne (1899–1991) was his daughter by his second marriage to Danish journalist Julie Nørregaard (1863–1942) ...

, intended as a revival of Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

's periodical of the same name. After the turn of the 20th century, Vivian wrote several novels, some anonymously or using pseudonyms, which met mixed reviews. ''The Master Sinner'' was seen by ''The Publisher's Circular'' as "unpleasant but clever", and in ''The Literary World'' as having a "style... jerky and overladen with adjectives", but still "a readable book".

Of Vivian's several travel books, the best-known was ''Servia: The Poor Man's Paradise'' (1897), which was widely quoted in newspapers, including ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', the ''Morning Post

''The Morning Post'' was a conservative daily newspaper published in London from 1772 to 1937, when it was acquired by ''The Daily Telegraph''.

History

The paper was founded by John Bell. According to historian Robert Darnton, ''The Morning Po ...

'' and ''Pearson's Weekly''.

In 1901, Vivian wrote with his wife Olive a book on European religious rituals, described in the ''Sheffield Independent'' as "well written, curious and readable, and marred only by a singularly fatuous surrender to any form of superstition however grovelling". In 1902, Vivian interviewed the French novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans

Charles-Marie-Georges Huysmans (, ; 5 February 1848 – 12 May 1907) was a French novelist and art critic who published his works as Joris-Karl Huysmans (, variably abbreviated as J. K. or J.-K.). He is most famous for the novel ''À rebou ...

.

In 1903, Vivian returned to the subject of Serbia in "The Servian Character" for the ''

In 1903, Vivian returned to the subject of Serbia in "The Servian Character" for the ''English Illustrated Magazine

''The English Illustrated Magazine'' was a monthly publication that ran for 359 issues between October 1883 and August 1913. Features included travel, topography, and a large amount of fiction and were contributed by writers such as Thomas Hardy ...

''. He followed this with a second work, ''The Servian Tragedy: With Some Impressions of Macedonia'' (1904), detailing the coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

against the Serbian royal family. This was reviewed in the ''Sheffield Daily Telegraph'': "The author has a thorough personal knowledge of the country, was received in audience by the late King and Queen, and is personally acquainted with all the statesmen. The Belgrade catastrophe is minutely described from full particulars obtained first hand." It was reviewed less positively in the ''London Daily News'': "Mr. Herbert Vivian's new book... presents many interesting chapters on the events leading up to the recent tragedy, but can hardly be looked upon as an authoritative history. The matter is thin, the author does not quote his authorities; and he is too evidently willing to accept hearsay in place of evidence."

Vivian, as a friend of Winston Churchill, met him several times in the 1900s, seeking political gossip and advice. In 1905 Vivian published the first interview given by Churchill, published in ''The Pall Mall Magazine

''The Pall Mall Magazine'' was a monthly British literary magazine published between 1893 and 1914. Begun by William Waldorf Astor as an offshoot of ''The Pall Mall Gazette'', the magazine included poetry, short stories, serialized fiction, and ge ...

'', which received attention in the press. Vivian also interviewed David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

, the President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. This is a committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centu ...

, for ''The Pall Mall Magazine'' and wrote for ''The Fortnightly Review

''The Fortnightly Review'' was one of the most prominent and influential magazines in nineteenth-century England. It was founded in 1865 by Anthony Trollope, Frederic Harrison, Edward Spencer Beesly, and six others with an investment of £9,000; ...

''.

In 1904, Vivian made a political speech containing pointed remarks about George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

. Shaw and Vivian exchanged letters on the matter, which Vivian then published, to Shaw's chagrin:

The publication of my letter to Mr. Vivian was a piece of humourous cruelty in which I had no part. I honestly gave Mr. Vivian the best advice I could in his own interest in a letter obviously not intended for publication; and if he had acted quietly upon it, instead of sending it off to the papers... he might still have a chance at a seat in the next Parliament.... I shall not pretend to be sorry that I have helped Mr. Bowerman, the accredited Labour candidate, to disable an opponent who, if he had played his cards skilfully, might have proved very dangerous... Yours, G. Bernard ShawVivian continued his keen interest in the Balkan states. In 1907, he joined a plot to put

Prince Arthur of Connaught

Prince Arthur of Connaught (Arthur Frederick Patrick Albert; 13 January 1883 – 12 September 1938) was a British military officer and a grandson of Queen Victoria. He served as Governor-General of the Union of South Africa from 20 November 1920 ...

on the throne of Serbia. A year later, the Montenegrin government considered appointing him as its Honorary Consul in London, and Vivian wrote to his friend Winston Churchill, asking for an exequatur

An exequatur (Latin, literally "let it execute") is a legal document issued by a sovereign authority that permits the exercise or enforcement of a right within the jurisdiction of the authority.

International relations

An exequatur is a patent ...

for his appointment.

In 1908, Vivian proposed a gambling "system" for roulette

Roulette is a casino game named after the French word meaning ''little wheel'' which was likely developed from the Italian game Biribi''.'' In the game, a player may choose to place a bet on a single number, various groupings of numbers, the ...

published in ''The Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after bei ...

''. His system relied on the gambler's fallacy and it was debunked by Sir Hiram Maxim

Sir Hiram Stevens Maxim (5 February 1840 – 24 November 1916) was an American-British inventor best known as the creator of the first automatic machine gun, the Maxim gun. Maxim held patents on numerous mechanical devices such as hair-curli ...

in the ''Literary Digest

''The Literary Digest'' was an influential American general interest weekly magazine published by Funk & Wagnalls. Founded by Isaac Kaufmann Funk in 1890, it eventually merged with two similar weekly magazines, ''Public Opinion'' and '' Current ...

'' in October 1908.

Vivian continued to publish books in the

Vivian continued to publish books in the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, notably a 1917 volume, ''Italy at War'', which despite its title was largely a travelogue. He tried to join the Ministry of Information and met both Lord Beaverbrook and John Buchan

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir (; 26 August 1875 – 11 February 1940) was a Scottish novelist, historian, and Unionist politician who served as Governor General of Canada, the 15th since Canadian Confederation.

After a brief legal career ...

as part of his efforts, but his services were rejected, although Buchan admitted to Jacobite sympathies during their meeting. Vivian instead returned to the ''Daily Express'' as travel correspondent for 1918.

In the 1920s Vivian worked as a travel stringer

Stringer may refer to:

Structural elements

* Stringer (aircraft), or longeron, a strip of wood or metal to which the skin of an aircraft is fastened

* Stringer (slag), an inclusion, possibly leading to a defect, in cast metal

* Stringer (stairs), ...

for newspapers that included ''The Pall Mall Magazine'' and ''The Yorkshire Post

''The Yorkshire Post'' is a daily broadsheet newspaper, published in Leeds in Yorkshire, England. It primarily covers stories from Yorkshire although its masthead carries the slogan "Yorkshire's National Newspaper". It was previously owned by ...

''. In 1927, he wrote ''Secret Societies Old and New'', which received mixed reviews, ''The Spectator'' calling it "well-written and extremely readable", but Albert Mackey noting, "The author does not possess sufficient knowledge for his task."

In 1932, Vivian returned to European political history and legitimism with ''The Life of the Emperor Charles of Austria'', the first biography of Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

published in English. It was positively received in the ''Belfast News Letter

The ''News Letter'' is one of Northern Ireland's main daily newspapers, published from Monday to Saturday. It is the world's oldest English-language general daily newspaper still in publication, having first been printed in 1737.

The newspape ...

''. He continued to write on the Balkans, with an article in ''The English Review

''The English Review'' was an English-language literary magazine published in London from 1908 to 1937. At its peak, the journal published some of the leading writers of its day.

History

The magazine was started by 1908 by Ford Madox Hueffer (la ...

'' in 1933 on racial tensions in Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

.

Vivian's writings were noted in his lifetime and after; he is listed in the 1926 edition of ''Who's Who in Literature'', and the 1967 ''New Century Handbook of English Literature''.

Political candidate

In 1889, Vivian sought to stand in the Dover by-election. He withdrew and later alleged that the Irish journalist and candidate for Galway Borough,T. P. O'Connor

Thomas Power O'Connor (5 October 1848 – 18 November 1929), known as T. P. O'Connor and occasionally as Tay Pay (mimicking his own pronunciation of the initials ''T. P.''), was an Irish nationalist politician and journalist who served as a ...

, had stepped in to prevent his candidacy.

In April 1891, Vivian announced he was standing in the East Bradford constituency for the Jacobite "Individualist Party", of which he was sole member. By May 1891, Vivian was claiming to be the Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

candidate for the seat, though this was denied by the Bradford Trade and Labour Council. During the campaign he was named as co-respondent in a divorce case which was gleefully reported by the local press. He duly lost the 1892 election to William Sproston Caine.

In 1895, he stood for the North Huntingdonshire constituency on an explicitly Jacobite platform. The seat was comfortably held by A.E. Fellowes.

Undeterred by failures, Vivian again sought election in the 20th century. He was interested in the Deptford constituency, where he had helped Wilfrid Blunt's campaign 15 years earlier. He began to campaign there at the end of 1903 and spoke at a free trade meeting in December, reading letters of support he had received from Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

and John Dickson-Poynder, MP for Chippenham. Churchill joined the Liberal party in 1904 and Vivian followed him. He was selected as a Liberal candidate to fight the 1906 election, and Churchill spoke in his support at two meetings. Vivian met serious opposition to his candidacy, and received only 726 votes, losing heavily to the Labour Party's C. W. Bowerman.

In 1908, Vivian looked into standing as a candidate in the Stirling Burghs constituency after the death of the former Prime Minister Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (né Campbell; 7 September 183622 April 1908) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. He served as the prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1905 to 1908 and leader of the Liberal Party from 1899 to 1 ...

, who had held the seat for the Liberals. Vivian again espoused legitimist views in support of restoring the House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter fi ...

. In the end he did not stand and the seat was won by Arthur Ponsonby

Arthur Augustus William Harry Ponsonby, 1st Baron Ponsonby of Shulbrede (16 February 1871 – 23 March 1946), was a British politician, writer, and social activist. He was the son of Sir Henry Ponsonby, Private Secretary to Queen Victoria and ...

.

Fascist sympathies

In 1920, Vivian metBenito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

and Gabriele D'Annunzio in Italy and became an admirer of fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

, notably Italian Fascism. In 1926, he wrote of his visits to Mussolini's Italy:

I find most useful, instead of a passport, is a copy of the first Fascist newspaper, for which I wrote an article in 1920... These fascist syndicates everywhere are not unlike the Soviets, and Fascism is very like Bolshevism in many ways. Except that one means well, and the other not. Fascism is certainly succeeding... All the public services go like clockwork, trains arrive to the tick.In May 1929, Vivian and

Hugh George de Willmott Newman

Hugh George de Willmott Newman (17 January 1905 – 28 February 1979) was an Independent Catholic or independent Old Catholic bishop. He was known religiously as Mar Georgius I and bore the titles, among others, of Patriarch of Glastonbury, ...

founded the Royalist International, a group with a stated aim of opposing the spread of Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, fo ...

and restoring the Italian monarchy, but with a clear pro-fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

agenda. Vivian was General Secretary and editor of the league's publication, the ''Royalist International Herald''. Newman, 24 at the time, went on to be ordained a bishop in the Independent Catholic church and an archbishop in the Catholicate of the West

The Catholicate of the West was a Christian denomination established in 1944 and which ceased to exist in 1994 to become the British Orthodox Church.

The denomination was also known as the Catholic Apostolic Church, the Catholicate of the West ( ...

, and was involved in Aleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley (; born Edward Alexander Crowley; 12 October 1875 – 1 December 1947) was an English occultist, ceremonial magician, poet, painter, novelist, and mountaineer. He founded the religion of Thelema, identifying himself as the pro ...

's Ordo Templi Orientis

Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.; ) is an occult initiatory organization founded at the beginning of the 20th century. The origins of the O.T.O. can be traced back to the German-speaking occultists Carl Kellner, Heinrich Klein, Franz Hartmann and T ...

. In 1933, Vivian wrote:

Monarchy... sa more satisfactory form of government than the insidious poisons of a plutocracy ndthe distorted democracy of Parliaments... the world's galloping consumption will not be arrested until... Kings forget their ancient animosities to unite in a Royalist International uncontaminated and unhampered by the lying, cowardly, malignant Spirit of the Age.In 1936 came Vivian's ''Fascist Italy'', in which he expressed admiration for the Italian fascist regime. It received a scathing review in the ''

Nottingham Journal

The ''Nottingham Journal'' was a newspaper published in Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, in the East Midlands in England. During that time, the paper went through several title changes through mergers, take-overs, acquisitions and ownership changes. ...

'': "A facile writer of travel guides... Herbert Vivian must be read as an amusement of a rather grim sort than as an education.... This is a book which need not be taken too seriously, but which may be worth reading with no more attention than is given to works which claim, as this one does not, to be mainly fiction." The ''Dundee Evening Telegraph

The ''Evening Telegraph'' is a local newspaper in Dundee, Scotland. Known locally as the ''Tele'' (usually pronounced ''Tully or Tilly''), it is the sister paper of '' The Courier'', also published by Dundee firm D. C. Thomson & Co. Ltd. It w ...

'' review noted Vivian "writes with rapturous enthusiasm. Mussolini is to him a "saviour", who "restored order and glory and pride, cured his country in her calenture, create an imperial future with traditions of ancient Rome"... Inasmuch as it is a mouthpiece for crude propaganda, Mr. Vivian's book is regrettable."

Political views

Vivian's political views varied over his life, embracing at times one-nation Toryism, free-trade liberalism and openfascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

. Indeed, he often seemed more interested in the mechanisms of power and power of persuasive political speech than in consistent policies or positions.

During a failed campaign for the 1891 Bradford East by-election he wrote:

I preach fanatically the gospel of individualism according to John Stuart Mill and Herbert Spencer. The first principle of this gospel is that everyone must be allowed to do whatever he pleases so long as his doing so does not interfere with the liberty of others to do the same. I am a staunch free trader, desiring the abolition of that curse of civilisation, the custom house. I protest against all monopolies, whether exercised by un-wieldy State departments, or by grasping individuals, and I support the claims of all nationalities to the management of their own affairs.Some of his beliefs were consistent: he held racist views from early days: He was noted for "extreme monarchist views" throughout his life, and became antagonistic to democracy. His 1933 ''Kings in Waiting'' – in which he wrote "Democracy, liberty, and prosperity had been the mirages that had attracted the nations to their shambles" – was noted for its passionate pro-Monarchist and anti-Democratic stance. He was a prominent British Serbophile and an early proponent of a

Greater Serbia

The term Greater Serbia or Great Serbia ( sr, Велика Србија, Velika Srbija) describes the Serbian nationalist and irredentist ideology of the creation of a Serb state which would incorporate all regions of traditional significance to S ...

that encompassed most of the territory of Macedonia.

Modern perceptions

Vivian's books and articles on Serbia remain widely quoted in modern histories of the region. Slobodan Markovich, writing in 2000, describes ''Servia: A Poor Man's Paradise as a rather sympathetic account of the Serbian King Alexander and the Serbian Army.... Although biased, the book has an abundance of facts and confirms the extent to which British knowledge on Serbia had accumulated in previous decades." Markovich says that Vivian "among Britons who took part in the creation of the image of Serbia and the Balkans" was the "one person hoshould be given a special attention." He also noted put Vivian and anthropologistEdith Durham

Edith Durham, (8 December 1863 – 15 November 1944) was a British artist, anthropologist and writer who is best known for her anthropological accounts of life in Albania in the early 20th century. Her advocacy on behalf of the Albanian cause a ...

"among heprominent actors of the 'balkanisation' of the Near East", who greatly influenced the British perception of the Balkans after the First World War."

In 2013, ''Servia: The Poor Man's Paradise'' was described by Radmila Pejic as "a major contribution to British travel writing about Serbia with its in-depth analysis and rather objective portrayal of the country's political system, religious practices and economic situation."

Although Vivian's Neo-Jacobite views are now largely forgotten, his 1893 wreath-laying earned him the epithet "political maverick" from Smith, who summed up the impact of the event: "The affair enjoyed publicity out of all proportion to the latter-day significance of the Jacobite cause, which had long been effectively extinct, but as one man's crusade against an aspect of state bureaucracy, it acquired contemporary meaning."

Miller and Morelon call him a "monarchist British historian" and ascribe his interest in Emperor Charles of Austria to an uncritical admiration of kings.

Personal life

Vivian at 27 was named as co-respondent in a divorce case. In 1891, he had met Henry Simpson and his wife Maud Mary Simpson in Venice and become a frequent visitor to their home. Henry Simpson was an artist and a friend of Whistler. The Simpsons travelled on to Paris, where Mrs Simpson confessed that Vivian had proposed to her. The Simpsons then returned to London and Mrs Simpson left her husband and demanded a divorce, as she and Vivian were living together inBognor Regis

Bognor Regis (), sometimes simply known as Bognor (), is a town and seaside resort in West Sussex on the south coast of England, south-west of London, west of Brighton, south-east of Chichester and east of Portsmouth. Other nearby towns ...

under the assumed names of Mr and Mrs Selwyn. The Simpsons' divorce came in December 1892, one of only 354 granted in England and Wales that year. On 22 June 1893, Vivian married Simpson. She pursued her ambition to become an actress and in 1895 she travelled to Holland, where she abandoned Vivian for a Mr Sundt of the Norwegian Legation in Amsterdam. The marriage ended in divorce in 1896.

On 30 September 1897, Vivian married Olive Walton, daughter of Frederick Walton

Frederick Edward Walton (13 March 183416 May 1928), was an English manufacturer and inventor whose invention of Linoleum in Chiswick was patented in 1863. He also invented Lincrusta in 1877.

Early life

Walton was born in 1834, near Halifax. ...

the inventor of linoleum

Linoleum, sometimes shortened to lino, is a floor covering made from materials such as solidified linseed oil (linoxyn), Pine Resin, pine resin, ground Cork (material), cork dust, sawdust, and mineral fillers such as calcium carbonate, most com ...

. Herbert and Olive were well known on the London social scene in the years just after the First World War and occur in Anthony Powell

Anthony Dymoke Powell ( ; 21 December 1905 – 28 March 2000) was an English novelist best known for his 12-volume work ''A Dance to the Music of Time'', published between 1951 and 1975. It is on the list of longest novels in English.

Powell' ...

's memoir ''Infants of the Spring'' as throwing a lavish luncheon in honour of Aleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley (; born Edward Alexander Crowley; 12 October 1875 – 1 December 1947) was an English occultist, ceremonial magician, poet, painter, novelist, and mountaineer. He founded the religion of Thelema, identifying himself as the pro ...

. Powell notes that their "marriage did not last long, but was still going at this period." Olive kept up a lively correspondence with Powell's father for many years after the divorce.

Vivian was made a Knight of the Royal Serbian Order of Takovo in 1902 and a Commander of the Royal Montenegrin Order of Danilo

The Order of Prince Danilo I ( cnr, Орден Књаза Данила I, translit=Orden Knjaza Danila I) was an order of the Principality and later Kingdom, of Montenegro. It is currently a dynastic order granted by the head of the House of P ...

in 1910.

Herbert Vivian died on 18 April 1940 at Gunwalloe

Gunwalloe ( kw, Pluw Wynnwalow) is a coastal civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated on the Lizard Peninsula south of Helston and partly contains The Loe, the largest natural freshwater lake in Cornwall. The parish pop ...

in Cornwall, from his grandfather's house in St Clement.

Works

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* (published under a pseudonym)

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

The following books are commonly attributed to Vivian, but at least one source gives Wilfrid Keppel Honnywill as the author.

* (published anonymously)

* (published anonymously)

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* (published under a pseudonym)

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

The following books are commonly attributed to Vivian, but at least one source gives Wilfrid Keppel Honnywill as the author.

* (published anonymously)

* (published anonymously)

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Vivian, Herbert 1865 births 1940 deaths 19th-century British newspaper founders 19th-century English novelists 20th-century British newspaper founders 20th-century English novelists 20th-century British journalists Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge British science fiction writers English fascists English Jacobites English journalists English travel writers Jacobite propagandists Liberal Party (UK) parliamentary candidates Montenegro–United Kingdom relations Neo-Jacobite Revival Oscar Wilde People educated at Harrow SchoolHerbert

Herbert may refer to:

People Individuals

* Herbert (musician), a pseudonym of Matthew Herbert

Name

* Herbert (given name)

* Herbert (surname)

Places Antarctica

* Herbert Mountains, Coats Land

* Herbert Sound, Graham Land

Australia

* Herbert ...