Herbert G. Wells on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. '' The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction'' (sf-encyclopedia.com). Retrieved 22 August 2015. Entry by 'JC/BS'

Herbert George Wells was born at Atlas House, 162 High Street in Bromley, Kent, on 21 September 1866. Called "Bertie" by his family, he was the fourth and last child of Joseph Wells, a former domestic gardener, and at the time a shopkeeper and professional

Herbert George Wells was born at Atlas House, 162 High Street in Bromley, Kent, on 21 September 1866. Called "Bertie" by his family, he was the fourth and last child of Joseph Wells, a former domestic gardener, and at the time a shopkeeper and professional  No longer able to support themselves financially, the family instead sought to place their sons as apprentices in various occupations. From 1880 to 1883, Wells had an unhappy apprenticeship as a draper at Hyde's Drapery Emporium in Southsea. His experiences at Hyde's, where he worked a thirteen-hour day and slept in a dormitory with other apprentices, later inspired his novels ''

No longer able to support themselves financially, the family instead sought to place their sons as apprentices in various occupations. From 1880 to 1883, Wells had an unhappy apprenticeship as a draper at Hyde's Drapery Emporium in Southsea. His experiences at Hyde's, where he worked a thirteen-hour day and slept in a dormitory with other apprentices, later inspired his novels ''

In October 1879, Wells's mother arranged through a distant relative, Arthur Williams, for him to join the National School at

In October 1879, Wells's mother arranged through a distant relative, Arthur Williams, for him to join the National School at  During 1888, Wells stayed in

During 1888, Wells stayed in

In 1891, Wells married his cousin Isabel Mary Wells (1865–1931; from 1902 Isabel Mary Smith). The couple agreed to separate in 1894, when he had fallen in love with one of his students, Amy Catherine Robbins (1872–1927; later known as Jane), with whom he moved to

In 1891, Wells married his cousin Isabel Mary Wells (1865–1931; from 1902 Isabel Mary Smith). The couple agreed to separate in 1894, when he had fallen in love with one of his students, Amy Catherine Robbins (1872–1927; later known as Jane), with whom he moved to  In late summer 1896, Wells and Jane moved to a larger house in Worcester Park, near Kingston upon Thames, for two years; this lasted until his poor health took them to Sandgate, near

In late summer 1896, Wells and Jane moved to a larger house in Worcester Park, near Kingston upon Thames, for two years; this lasted until his poor health took them to Sandgate, near

Some of his early novels, called " scientific romances", invented several themes now classic in science fiction in such works as '' The Time Machine'', ''

Some of his early novels, called " scientific romances", invented several themes now classic in science fiction in such works as '' The Time Machine'', '' Wells also wrote non-fiction. His first non-fiction

Wells also wrote non-fiction. His first non-fiction  From quite early in Wells's career, he sought a better way to organise society and wrote a number of Utopian novels. The first of these was '' A Modern Utopia'' (1905), which shows a worldwide utopia with "no imports but meteorites, and no exports at all"; two travellers from our world fall into its

From quite early in Wells's career, he sought a better way to organise society and wrote a number of Utopian novels. The first of these was '' A Modern Utopia'' (1905), which shows a worldwide utopia with "no imports but meteorites, and no exports at all"; two travellers from our world fall into its  In 1927, a Canadian teacher and writer

In 1927, a Canadian teacher and writer  In 1933, Wells predicted in ''The Shape of Things to Come'' that the world war he feared would begin in January 1940, a prediction which ultimately came true four months early, in September 1939, with the outbreak of World War II. In 1936, before the

In 1933, Wells predicted in ''The Shape of Things to Come'' that the world war he feared would begin in January 1940, a prediction which ultimately came true four months early, in September 1939, with the outbreak of World War II. In 1936, before the

Seeking a more structured way to play war games, Wells wrote '' Floor Games'' (1911) followed by '' Little Wars'' (1913), which set out rules for fighting battles with toy soldiers (miniatures). A

Seeking a more structured way to play war games, Wells wrote '' Floor Games'' (1911) followed by '' Little Wars'' (1913), which set out rules for fighting battles with toy soldiers (miniatures). A

Wells's greatest literary output occurred before the First World War, which was lamented by younger authors whom he had influenced. In this connection,

Wells's greatest literary output occurred before the First World War, which was lamented by younger authors whom he had influenced. In this connection,

Wells died of unspecified causes on 13 August 1946, aged 79, at his home at 13 Hanover Terrace, overlooking Regent's Park, London. In his preface to the 1941 edition of ''

Wells died of unspecified causes on 13 August 1946, aged 79, at his home at 13 Hanover Terrace, overlooking Regent's Park, London. In his preface to the 1941 edition of ''

A futurist and "visionary", Wells foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television, and something resembling the World Wide Web. Asserting that "Wells's visions of the future remain unsurpassed",

A futurist and "visionary", Wells foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television, and something resembling the World Wide Web. Asserting that "Wells's visions of the future remain unsurpassed",

Wells was a socialist and a member of the Fabian Society.

Wells was a socialist and a member of the Fabian Society.

The science fiction historian

The science fiction historian

Nobel Prize.org. Retrieved 19 March 2015. Wells so influenced real exploration of space that an impact crater on Mars ( and the Moon) was named after him. In the United Kingdom, Wells's work was a key model for the British "scientific romance", and other writers in that mode, such as Olaf Stapledon,

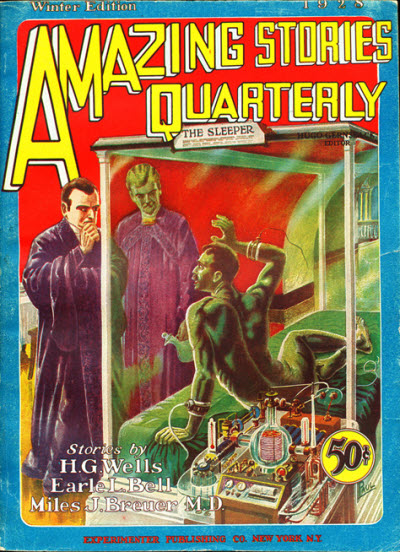

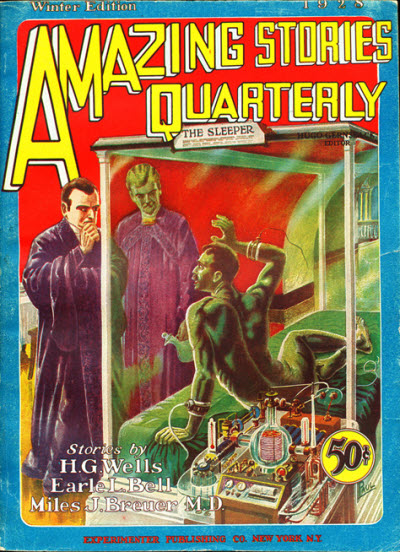

In the United Kingdom, Wells's work was a key model for the British "scientific romance", and other writers in that mode, such as Olaf Stapledon,  In the United States, Hugo Gernsback reprinted most of Wells's work in the pulp magazine '' Amazing Stories'', regarding Wells's work as "texts of central importance to the self-conscious new genre". Later American writers such as Ray Bradbury,

In the United States, Hugo Gernsback reprinted most of Wells's work in the pulp magazine '' Amazing Stories'', regarding Wells's work as "texts of central importance to the self-conscious new genre". Later American writers such as Ray Bradbury,  Jorge Luis Borges wrote many short pieces on Wells in which he demonstrates a deep familiarity with much of Wells's work. While Borges wrote several critical reviews, including a mostly negative review of Wells's film ''Things to Come'', he regularly treated Wells as a canonical figure of fantastic literature. Late in his life, Borges included ''The Invisible Man'' and ''The Time Machine'' in his ''Prologue to a Personal Library'', a curated list of 100 great works of literature that he undertook at the behest of the Argentine publishing house Emecé. Canadian author

Jorge Luis Borges wrote many short pieces on Wells in which he demonstrates a deep familiarity with much of Wells's work. While Borges wrote several critical reviews, including a mostly negative review of Wells's film ''Things to Come'', he regularly treated Wells as a canonical figure of fantastic literature. Late in his life, Borges included ''The Invisible Man'' and ''The Time Machine'' in his ''Prologue to a Personal Library'', a curated list of 100 great works of literature that he undertook at the behest of the Argentine publishing house Emecé. Canadian author

University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. The university's"H. G. Wells Correspondence"

Library Illinois. Among these is unpublished material and the manuscripts of such works as ''The War of the Worlds'' and ''The Time Machine''. The collection includes first editions, revisions and translations. The letters contain general family correspondence, communications from publishers, material regarding the Fabian Society, and letters from politicians and public figures, most notably George Bernard Shaw and

''Future Tense – The Story of H. G. Wells''

at BBC One – 150th anniversary documentary (2016)

"In the footsteps of H G Wells"

at '' New Statesman'' – "The great author called for a Human Rights Act; 60 years later, we have it" (2000)

Free H. G. Wells downloads for iPhone, iPad, Nook, Android, and Kindle in PDF and all popular eBook reader formats (AZW3, EPUB, MOBI)

at ebooktakeaway.com

H G Wells

at the British Library

H. G. Wells papers

at University of Illinois

Ebooks by H. G. Wells

at Global Grey Ebooks *

Archive of Wells's BBC broadcasts

Film interview with H. G. Wells

"Stephen Crane. From an English Standpoint"

by Wells, 1900.

Rabindranath Tagore and Wells conversing in Geneva in 1930.

"Introduction"

to W. N. P. Barbellion's ''The Journal of a Disappointed Man'', by Wells, 1919.

by Wells, 1895.

to

"H. G. Wells"

In '' Encyclopædia Britannica'' Online. * *

An introduction to ''The War of the Worlds'' by Iain Sinclair

on the British Library's Discovering Literature website.

"An Appreciation of H. G. Wells"

by

Part 1

by Niall Ferguson, in '' The Telegraph'', 24 June 2005.

"H. G. Wells's Idea of a World Brain: A Critical Re-assessment"

by W. Boyd Rayward, in ''Journal of the American Society for Information Science'' 50 (15 May 1999): 557–579

by G. K. Chesterton, from his book ''Heretics'' (1908).

"The Internet: a world brain?"

by Martin Gardner, in '' Skeptical Inquirer'', Jan–Feb 1999.

"Science Fiction: The Shape of Things to Come"

by Mark Bould, in ''The Socialist Review'', May 2005.

"Who needs Utopia? A dialogue with my utopian self (with apologies, and thanks, to H. G. Wells)"

by

"When H. G. Wells Split the Atom: A 1914 Preview of 1945"

by Freda Kirchwey, in '' The Nation'', posted 4 September 2003 (original 18 August 1945 issue).

"Wells, Hitler and the World State"

by George Orwell. First published: ''Horizon''. GB, London. Aug 1941.

"War of the Worldviews"

by John J. Miller, in '' The Wall Street Journal'' Opinion Journal, 21 June 2005.

"Wells's Autobiography"

by John Hart, from ''New International'', Vol.2 No.2, Mar 1935, pp. 75–76.

"History in the Science Fiction of H. G. Wells"

by

"From the World Brain to the Worldwide Web"

by Martin Campbell-Kelly, Gresham College Lecture, 9 November 2006.

"The Beginning of Wisdom: On Reading H. G. Wells"

by

John Hammond, The Complete List of Short Stories of H. G. Wells

at ''National Geographic''

"H. G. Wells, the man I knew"

Obituary of Wells by George Bernard Shaw, at the '' New Statesman'' * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Wells, H. G. 1866 births 1946 deaths 19th-century atheists 19th-century British non-fiction writers 19th-century British novelists 19th-century British short story writers 19th-century educational theorists 19th-century English non-fiction writers 19th-century English novelists 19th-century essayists 19th-century social scientists 20th-century atheists 20th-century biographers 20th-century British historians 20th-century British non-fiction writers 20th-century British novelists 20th-century British screenwriters 20th-century British short story writers 20th-century educational theorists 20th-century English historians 20th-century English non-fiction writers 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English screenwriters 20th-century essayists 20th-century memoirists 20th-century social scientists 20th-century travel writers Alumni of Imperial College London Alumni of the University of London Alumni of University of London Worldwide Anthropology writers Anti-capitalists Anti-monarchists Atheist philosophers British alternative history writers British anti-communists British anti-fascists British atheists British autobiographers British biographers British biologists British educational theorists British fantasy writers British horror writers British magazine founders British male essayists British male non-fiction writers British male novelists British male short story writers British philosophers British political writers British republicans British satirists British sceptics British science fiction writers British science writers British screenwriters British social sciences writers British social scientists British socialists British sociologists Civil servants in the Ministry of Information (United Kingdom) Critics of religions Critics of the Catholic Church Cultural critics Cycling writers English anti-fascists English atheists English autobiographers English biographers English biologists English educational theorists English essayists English fantasy writers English horror writers English humanists English humorists English male non-fiction writers English male novelists English male short story writers English memoirists English philosophers English political writers English republicans English satirists English sceptics English science fiction writers English science writers English short story writers English social commentators English socialists English sociologists English travel writers Futurologists Ghost story writers History of literature Human evolution theorists Irony theorists Lecturers Literacy and society theorists Literary theorists London School of Economics Magic realism writers Mass media theorists Members of the Fabian Society Metaphor theorists Metaphysics writers Military science fiction writers Pamphleteers Presidents of the English Centre of PEN People associated with the University of London People educated at Midhurst Grammar School People from Bromley People from Sandgate, Kent People of the Victorian era People with diabetes Philosophers of culture Philosophers of education Philosophers of history Philosophers of literature Philosophers of religion Philosophers of science Philosophers of social science Philosophers of technology Philosophers of war Philosophy writers Political philosophers Progressivism in the United Kingdom Psychological fiction writers Rationality theorists Science activists Science communicators Science fiction critics Science Fiction Hall of Fame inductees Social critics Social philosophers Surrealist writers Textbook writers Theorists on Western civilization Victorian novelists Weird fiction writers H. G. Writers about activism and social change Writers about communism Writers about globalization Writers about religion and science Writers about the Soviet Union Writers of fiction set in prehistoric times Writers of Gothic fiction Writers of time travel romance Writers who illustrated their own writing Writers with disabilities

Revised 18 May 2015. '' The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction'' (sf-encyclopedia.com). Retrieved 22 August 2015. Entry by 'JC/BS'

John Clute

John Frederick Clute (born 12 September 1940) is a Canadian-born author and critic specializing in science fiction and fantasy literature who has lived in both England and the United States since 1969. He has been described as "an integral part o ...

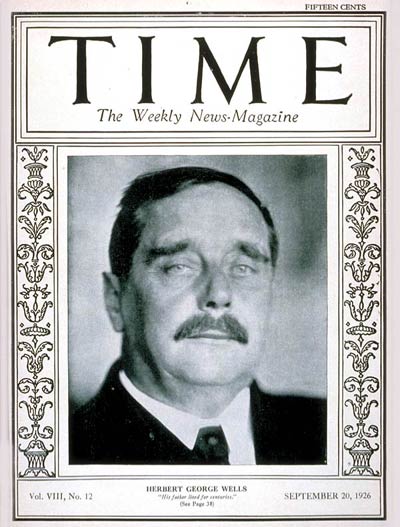

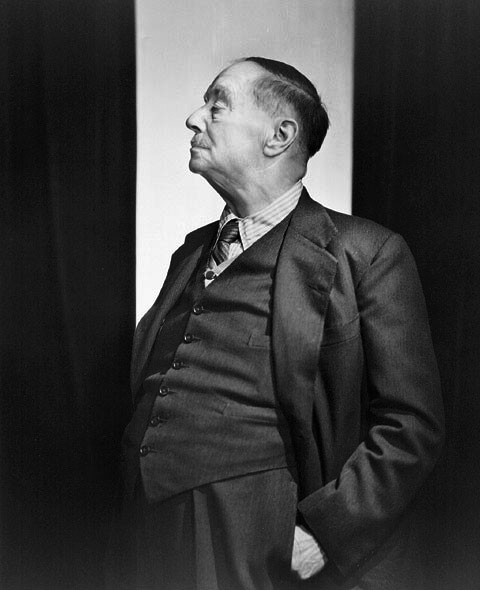

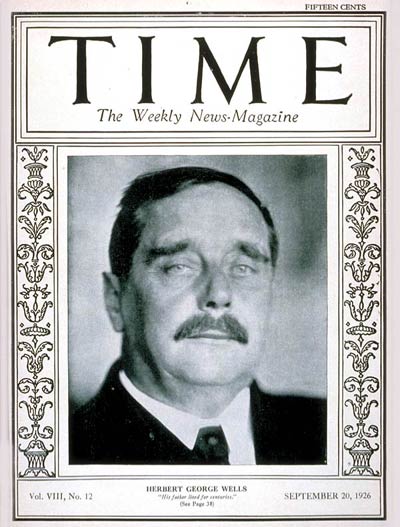

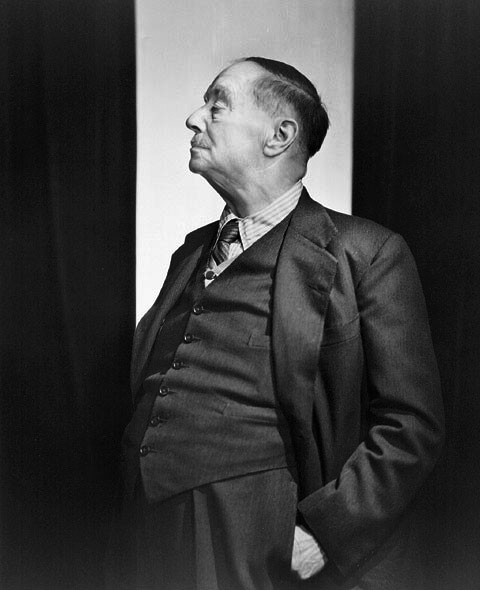

and Brian Stableford. (21 September 186613 August 1946) was an English writer. Prolific in many genres, he wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, history, popular science, satire, biography and autobiography. Wells is now best remembered for his science fiction novels and has been called the "father of science fiction."

In addition to his fame as a writer, he was prominent in his lifetime as a forward-looking, even prophetic social critic

Social criticism is a form of academic or journalistic criticism focusing on social issues in contemporary society, in particular with respect to perceived injustices and power relations in general.

Social criticism of the Enlightenment

The orig ...

who devoted his literary talents to the development of a progressive

Progressive may refer to:

Politics

* Progressivism, a political philosophy in support of social reform

** Progressivism in the United States, the political philosophy in the American context

* Progressive realism, an American foreign policy par ...

vision on a global scale. A futurist, he wrote a number of utopian works and foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television and something resembling the World Wide Web. His science fiction imagined time travel, alien invasion, invisibility, and biological engineering

Biological engineering or

bioengineering is the application of principles of biology and the tools of engineering to create usable, tangible, economically-viable products. Biological engineering employs knowledge and expertise from a number o ...

. Brian Aldiss referred to Wells as the "Shakespeare of science fiction", while Charles Fort called him a "wild talent".

Wells rendered his works convincing by instilling commonplace detail alongside a single extraordinary assumption per work – dubbed "Wells's law" – leading Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

to hail him in 1898 with "O Realist of the Fantastic!". His most notable science fiction works include '' The Time Machine'' (1895), which was his first novel, ''The Island of Doctor Moreau

''The Island of Doctor Moreau'' is an 1896 science fiction novel by English author H. G. Wells (1866–1946). The text of the novel is the narration of Edward Prendick who is a shipwrecked man rescued by a passing boat. He is left on the islan ...

'' (1896), '' The Invisible Man'' (1897), '' The War of the Worlds'' (1898), the military science fiction ''The War in the Air

''The War in the Air: And Particularly How Mr. Bert Smallways Fared While It Lasted'' is a military science fiction novel written by H. G. Wells.

The novel was written in four months in 1907, and was serialized and published in 1908 in ''The ...

'' (1907), and the dystopia

A dystopia (from Ancient Greek δυσ- "bad, hard" and τόπος "place"; alternatively cacotopiaCacotopia (from κακός ''kakos'' "bad") was the term used by Jeremy Bentham in his 1818 Plan of Parliamentary Reform (Works, vol. 3, p. 493). ...

n '' When the Sleeper Wakes'' (1910). Novels of social realism such as '' Kipps'' (1905) and '' The History of Mr Polly'' (1910), which describe lower-middle-class English life, led to the suggestion that he was a worthy successor to Charles Dickens, but Wells described a range of social strata and even attempted, in '' Tono-Bungay'' (1909), a diagnosis of English society as a whole. Wells was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901

, ...

four times.

Wells's earliest specialised training was in biology, and his thinking on ethical matters took place in a Darwinian context. He was also an outspoken socialist from a young age, often (but not always, as at the beginning of the First World War) sympathising with pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

views. In his later years, he wrote less fiction and more works expounding his political and social views, sometimes giving his profession as that of journalist. Wells was a diabetic and co-founded the charity The Diabetic Association (known today as Diabetes UK

Diabetes UK is a British-based patient, healthcare professional and research charity that has been described as "one of the foremost diabetes charities in the UK". The charity campaigns for improvements in the care and treatment of people with d ...

) in 1934.

Life

Early life

Herbert George Wells was born at Atlas House, 162 High Street in Bromley, Kent, on 21 September 1866. Called "Bertie" by his family, he was the fourth and last child of Joseph Wells, a former domestic gardener, and at the time a shopkeeper and professional

Herbert George Wells was born at Atlas House, 162 High Street in Bromley, Kent, on 21 September 1866. Called "Bertie" by his family, he was the fourth and last child of Joseph Wells, a former domestic gardener, and at the time a shopkeeper and professional cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

er and Sarah Neal, a former domestic servant. An inheritance had allowed the family to acquire a shop in which they sold china and sporting goods, although it failed to prosper: the stock was old and worn out, and the location was poor. Joseph Wells managed to earn a meagre income, but little of it came from the shop and he received an unsteady amount of money from playing professional cricket for the Kent county team.Smith, David C. (1986) ''H. G. Wells: Desperately mortal. A biography.'' Yale University Press, New Haven and London

A defining incident of young Wells's life was an accident in 1874 that left him bedridden with a broken leg. To pass the time he began to read books from the local library, brought to him by his father. He soon became devoted to the other worlds and lives to which books gave him access; they also stimulated his desire to write. Later that year he entered Thomas Morley's Commercial Academy, a private school founded in 1849, following the bankruptcy of Morley's earlier school. The teaching was erratic, the curriculum mostly focused, Wells later said, on producing copperplate handwriting and doing the sort of sums useful to tradesmen. Wells continued at Morley's Academy until 1880. In 1877, his father, Joseph Wells, fractured his thigh. The accident effectively put an end to Joseph's career as a cricketer, and his subsequent earnings as a shopkeeper were not enough to compensate for the loss of the primary source of family income.

No longer able to support themselves financially, the family instead sought to place their sons as apprentices in various occupations. From 1880 to 1883, Wells had an unhappy apprenticeship as a draper at Hyde's Drapery Emporium in Southsea. His experiences at Hyde's, where he worked a thirteen-hour day and slept in a dormitory with other apprentices, later inspired his novels ''

No longer able to support themselves financially, the family instead sought to place their sons as apprentices in various occupations. From 1880 to 1883, Wells had an unhappy apprenticeship as a draper at Hyde's Drapery Emporium in Southsea. His experiences at Hyde's, where he worked a thirteen-hour day and slept in a dormitory with other apprentices, later inspired his novels ''The Wheels of Chance

''The Wheels of Chance'' is an early comic novel by H. G. Wells about an August 1895 cycling holiday, somewhat in the style of ''Three Men in a Boat''. In 1922 it was adapted into a silent film ''The Wheels of Chance (film), The Wheels of Chance' ...

'', '' The History of Mr Polly'', and '' Kipps'', which portray the life of a draper's apprentice as well as providing a critique of society's distribution of wealth.

Wells's parents had a turbulent marriage, owing primarily to his mother's being a Protestant and his father's being a freethinker. When his mother returned to work as a lady's maid (at Uppark

Uppark is a 17th-century house in South Harting, West Sussex, England. It is a Grade I listed building and a National Trust property.

History

The house, set high on the South Downs, was built for Ford Grey (1655—1701), the first Earl of ...

, a country house

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a town house. This allowed them to spend time in the country and in the city—hence, for these peopl ...

in Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

), one of the conditions of work was that she would not be permitted to have living space for her husband and children. Thereafter, she and Joseph lived separate lives, though they never divorced and remained faithful to each other. As a consequence, Herbert's personal troubles increased as he subsequently failed as a draper and also, later, as a chemist's assistant. However, Uppark had a magnificent library in which he immersed himself, reading many classic works, including Plato's ''Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

'', Thomas More's '' Utopia'', and the works of Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

. When he became the first doyen of science fiction as a distinct genre of fiction, Wells referenced Mary Shelley's '' Frankenstein'' in relation to his works, writing, "they belong to a class of writing which includes the story of ''Frankenstein''."

Teacher

In October 1879, Wells's mother arranged through a distant relative, Arthur Williams, for him to join the National School at

In October 1879, Wells's mother arranged through a distant relative, Arthur Williams, for him to join the National School at Wookey

Wookey is a village and Civil parishes in England, civil parish west of Wells, Somerset, Wells, on the River Axe (Bristol Channel), River Axe in the Mendip District, Mendip district of Somerset, England. The parish includes the village of Henton ...

in Somerset as a pupil–teacher, a senior pupil who acted as a teacher of younger children. In December that year, however, Williams was dismissed for irregularities in his qualifications and Wells was returned to Uppark. After a short apprenticeship at a chemist in nearby Midhurst and an even shorter stay as a boarder at Midhurst Grammar School, he signed his apprenticeship papers at Hyde's. In 1883, Wells persuaded his parents to release him from the apprenticeship, taking an opportunity offered by Midhurst Grammar School again to become a pupil–teacher; his proficiency in Latin and science during his earlier short stay had been remembered.

The years he spent in Southsea had been the most miserable of his life to that point, but his good fortune in securing a position at Midhurst Grammar School meant that Wells could continue his self-education in earnest. The following year, Wells won a scholarship to the Normal School of Science (later the Royal College of Science in South Kensington, now part of Imperial College London) in London, studying biology under Thomas Henry Huxley. As an alumnus, he later helped to set up the Royal College of Science Association, of which he became the first president in 1909. Wells studied in his new school until 1887, with a weekly allowance of 21 shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence o ...

s (a guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

) thanks to his scholarship. This ought to have been a comfortable sum of money (at the time many working class families had "round about a pound a week" as their entire household income), yet in his ''Experiment in Autobiography'' Wells speaks of constantly being hungry, and indeed photographs of him at the time show a youth who is very thin and malnourished.

He soon entered the Debating Society of the school. These years mark the beginning of his interest in a possible reformation of society. At first approaching the subject through Plato's ''Republic'', he soon turned to contemporary ideas of socialism as expressed by the recently formed Fabian Society and free lectures delivered at Kelmscott House

Kelmscott House is Grade II* listed Georgian brick mansion at 26 Upper Mall in Hammersmith, overlooking the River Thames. Built in about 1785, it was the London home of English textile designer, artist, writer and socialist William Morris fro ...

, the home of William Morris. He was also among the founders of ''The Science School Journal'', a school magazine that allowed him to express his views on literature and society, as well as trying his hand at fiction; a precursor to his novel '' The Time Machine'' was published in the journal under the title '' The Chronic Argonauts''. The school year 1886–87 was the last year of his studies.

During 1888, Wells stayed in

During 1888, Wells stayed in Stoke-on-Trent

Stoke-on-Trent (often abbreviated to Stoke) is a city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Staffordshire, England, with an area of . In 2019, the city had an estimated population of 256,375. It is the largest settlement ...

, living in Basford. The unique environment of The Potteries

The Staffordshire Potteries is the industrial area encompassing the six towns Burslem, Fenton, Hanley, Longton, Stoke and Tunstall, which is now the city of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England. North Staffordshire became a centre of cera ...

was certainly an inspiration. He wrote in a letter to a friend from the area that "the district made an immense impression on me." The inspiration for some of his descriptions in ''The War of the Worlds'' is thought to have come from his short time spent here, seeing the iron foundry furnaces burn over the city, shooting huge red light into the skies. His stay in The Potteries also resulted in the macabre short story "The Cone

"The Cone" is a short story by H. G. Wells, first published in 1895 in ''Unicorn''. It was intended to be "the opening chapter of a sensational novel set in the Five Towns", later abandoned.

The story is set at an ironworks in Stoke-on-Trent, in ...

" (1895, contemporaneous with his famous ''The Time Machine''), set in the north of the city.

After teaching for some time, he was briefly on the staff of Holt

Holt or holte may refer to:

Natural world

*Holt (den), an otter den

* Holt, an area of woodland

Places Australia

* Holt, Australian Capital Territory

* Division of Holt, an electoral district in the Australian House of Representatives in Vic ...

Academy in Wales – Wells found it necessary to supplement his knowledge relating to educational principles and methodology and entered the College of Preceptors ( College of Teachers). He later received his Licentiate and Fellowship FCP diplomas from the college. It was not until 1890 that Wells earned a Bachelor of Science degree in zoology from the University of London External Programme. In 1889–90, he managed to find a post as a teacher at Henley House School in London, where he taught A. A. Milne (whose father ran the school). His first published work was a ''Text-Book of Biology'' in two volumes (1893).

Upon leaving the Normal School of Science, Wells was left without a source of income. His aunt Mary—his father's sister-in-law—invited him to stay with her for a while, which solved his immediate problem of accommodation. During his stay at his aunt's residence, he grew increasingly interested in her daughter, Isabel, whom he later courted. To earn money, he began writing short humorous articles for journals such as ''The Pall Mall Gazette

''The Pall Mall Gazette'' was an evening newspaper founded in London on 7 February 1865 by George Murray Smith; its first editor was Frederick Greenwood. In 1921, '' The Globe'' merged into ''The Pall Mall Gazette'', which itself was absorbed int ...

'', later collecting these in volume form as ''Select Conversations with an Uncle

''Select Conversations with an Uncle'', published in 1895, was H. G. Wells's first literary publication in book form. It consists of reports of twelve conversations between a fictional witty uncle who has returned to London from South Africa wit ...

'' (1895) and ''Certain Personal Matters

''Certain Personal Matters'' is an 1897 collection of essays selected by H. G. Wells from among the many short essays and ephemeral pieces he had written since 1893. The book consists of thirty-nine pieces ranging from

about eight hundred to tw ...

'' (1897). So prolific did Wells become at this mode of journalism that many of his early pieces remain unidentified. According to David C. Smith, "Most of Wells's occasional pieces have not been collected, and many have not even been identified as his. Wells did not automatically receive the byline his reputation demanded until after 1896 or so ... As a result, many of his early pieces are unknown. It is obvious that many early Wells items have been lost." His success with these shorter pieces encouraged him to write book-length work, and he published his first novel, '' The Time Machine'', in 1895.

Personal life

In 1891, Wells married his cousin Isabel Mary Wells (1865–1931; from 1902 Isabel Mary Smith). The couple agreed to separate in 1894, when he had fallen in love with one of his students, Amy Catherine Robbins (1872–1927; later known as Jane), with whom he moved to

In 1891, Wells married his cousin Isabel Mary Wells (1865–1931; from 1902 Isabel Mary Smith). The couple agreed to separate in 1894, when he had fallen in love with one of his students, Amy Catherine Robbins (1872–1927; later known as Jane), with whom he moved to Woking

Woking ( ) is a town and borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in northwest Surrey, England, around from central London. It appears in Domesday Book as ''Wochinges'' and its name probably derives from that of a Anglo-Saxon settlement o ...

, Surrey, in May 1895. They lived in a rented house, 'Lynton' (now No.141), Maybury Road, in the town centre for just under 18 months and married at St Pancras register office in October 1895. His short period in Woking was perhaps the most creative and productive of his whole writing career, for while there he planned and wrote '' The War of the Worlds'' and '' The Time Machine'', completed ''The Island of Doctor Moreau

''The Island of Doctor Moreau'' is an 1896 science fiction novel by English author H. G. Wells (1866–1946). The text of the novel is the narration of Edward Prendick who is a shipwrecked man rescued by a passing boat. He is left on the islan ...

'', wrote and published ''The Wonderful Visit

''The Wonderful Visit'' is an 1895 novel by H. G. Wells. With an angel—a creature of fantasy unlike a religious angel—as protagonist and taking place in contemporary England, the book could be classified as contemporary fantasy, although t ...

'' and ''The Wheels of Chance

''The Wheels of Chance'' is an early comic novel by H. G. Wells about an August 1895 cycling holiday, somewhat in the style of ''Three Men in a Boat''. In 1922 it was adapted into a silent film ''The Wheels of Chance (film), The Wheels of Chance' ...

'', and began writing two other early books, '' When the Sleeper Wakes'' and ''Love and Mr Lewisham

''Love and Mr Lewisham'' (subtitled "The Story of a Very Young Couple") is a 1900 in literature, 1900 novel set in the 1880s by H. G. Wells. It was among his first fictional writings outside the science fiction genre. Wells took considerable pai ...

''.

In the run-up to the 143rd anniversary of Wells's birth, Google published a cartoon riddle series with the solution being the coordinates of Woking's nearby Horsell Common—the location of the Martian landings in ''The War Of The Worlds''—described in newspaper article by

In late summer 1896, Wells and Jane moved to a larger house in Worcester Park, near Kingston upon Thames, for two years; this lasted until his poor health took them to Sandgate, near

In late summer 1896, Wells and Jane moved to a larger house in Worcester Park, near Kingston upon Thames, for two years; this lasted until his poor health took them to Sandgate, near Folkestone

Folkestone ( ) is a port town on the English Channel, in Kent, south-east England. The town lies on the southern edge of the North Downs at a valley between two cliffs. It was an important harbour and shipping port for most of the 19th and 20t ...

, where he constructed a large family home, Spade House

Spade House was the home of the science fiction writer H. G. Wells from 1901 to 1909. It is a large mansion overlooking Sandgate, Kent, Sandgate, near Folkestone, in southeast England.

History

The house was designed by C.F.A. Voysey, and extend ...

, in 1901. He had two sons with Jane: George Philip (known as "Gip"; 1901–1985) and Frank Richard (1903–1982) (grandfather of film director Simon Wells). Jane died on 6 October 1927, in Dunmow, at the age of 55, which left Wells devastated. She was cremated at Golders Green, with friends of the couple present including George Bernard Shaw.

Wells had affair

An affair is a sexual relationship, romantic friendship, or passionate attachment in which at least one of its participants has a formal or informal commitment to a third person who may neither agree to such relationship nor even be aware of i ...

s with a significant number of women. Dorothy Richardson

Dorothy Miller Richardson (17 May 1873 – 17 June 1957) was a British author and journalist. Author of ''Pilgrimage'', a sequence of 13 semi-autobiographical novels published between 1915 and 1967—though Richardson saw them as chapters of o ...

was a friend and they had a brief affair which led to a pregnancy and then miscarriage, in 1907. Wells was married to a former schoolmate of Richardson's. In December 1909, he had a daughter, Anna-Jane, with the writer Amber Reeves, whose parents, William and Maud Pember Reeves, he had met through the Fabian Society. Amber had married the barrister G. R. Blanco White

George Rivers Blanco White QC (8 May 1883 – 26 March 1966) was an English judge, Recorder of Croydon from 1940–56, and a member of the Special Divorce Commission, from 1948–1957.

The son of Thomas and Margaret Elizabeth Blanco White, he wa ...

in July of that year, as co-arranged by Wells. After Beatrice Webb

Martha Beatrice Webb, Baroness Passfield, (née Potter; 22 January 1858 – 30 April 1943) was an English sociologist, economist, socialist, labour historian and social reformer. It was Webb who coined the term ''collective bargaining''. She ...

voiced disapproval of Wells's "sordid intrigue" with Amber, he responded by lampooning Beatrice Webb and her husband Sidney Webb in his 1911 novel ''The New Machiavelli'' as 'Altiora and Oscar Bailey', a pair of short-sighted, bourgeois manipulators. Between 1910 and 1913, novelist Elizabeth von Arnim was one of his mistresses. In 1914, he had a son, Anthony West (1914–1987), by the novelist and feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

Rebecca West, 26 years his junior. In 1920–21, and intermittently until his death, he had a love affair with the American birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

activist Margaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term "birth control ...

.

Between 1924 and 1933 he partnered with the 22-year-younger Dutch adventurer and writer Odette Keun

Odette Zoé Keun (Pera, 10 September 1888 – Worthing, 14 March 1978) was a Dutch socialist, journalist and writer, who traveled extensively in Europe, including the Caucasus and the early Soviet Union.

Early years

Keun was the daughter of ...

, with whom he lived in ''Lou Pidou'', a house they built together in Grasse, France. Wells dedicated his longest book to her (''The World of William Clissold

''The World of William Clissold'' is a 1926 novel by H. G. Wells published initially in three volumes. The first volume was published in September to coincide with Wells's sixtieth birthday, and the second and third volumes followed at monthly i ...

'', 1926). When visiting Maxim Gorky in Russia 1920, he had slept with Gorky's mistress Moura Budberg

Maria Ignatievna von Budberg-Bönninghausen (russian: Мария (Мура) Игнатьевна Закревская-Бенкендорф-Будберг, ''Maria (Moura) Ignatievna Zakrevskaya-Benckendorff-Budberg'', née Zakrevskaya; February ...

, then still Countess Benckendorf and 27 years his junior. In 1933, when she left Gorky and emigrated to London, their relationship renewed and she cared for him through his final illness. Wells repeatedly asked her to marry him, but Budberg strongly rejected his proposals.

In ''Experiment in Autobiography'' (1934), Wells wrote: "I was never a great amorist, though I have loved several people very deeply". David Lodge's novel ''A Man of Parts'' (2011)—a 'narrative based on factual sources' (author's note)—gives a convincing and generally sympathetic account of Wells's relations with the women mentioned above, and others.

Director Simon Wells (born 1961), the author's great-grandson, was a consultant on the future scenes in '' Back to the Future Part II'' (1989).

Artist

One of the ways that Wells expressed himself was through his drawings and sketches. One common location for these was the endpapers and title pages of his own diaries, and they covered a wide variety of topics, from political commentary to his feelings toward his literary contemporaries and his current romantic interests. During his marriage to Amy Catherine, whom he nicknamed Jane, he drew a considerable number of pictures, many of them being overt comments on their marriage. During this period, he called these pictures "picshuas". These picshuas have been the topic of study by Wells scholars for many years, and in 2006, a book was published on the subject.Writer

The Island of Doctor Moreau

''The Island of Doctor Moreau'' is an 1896 science fiction novel by English author H. G. Wells (1866–1946). The text of the novel is the narration of Edward Prendick who is a shipwrecked man rescued by a passing boat. He is left on the islan ...

'', '' The Invisible Man'', '' The War of the Worlds'', '' When the Sleeper Wakes'', and '' The First Men in the Moon''. He also wrote realistic novels that received critical acclaim, including '' Kipps'' and a critique of English culture during the Edwardian period, '' Tono-Bungay''. Wells also wrote dozens of short stories and novellas, including, "The Flowering of the Strange Orchid", which helped bring the full impact of Darwin

Darwin may refer to:

Common meanings

* Charles Darwin (1809–1882), English naturalist and writer, best known as the originator of the theory of biological evolution by natural selection

* Darwin, Northern Territory, a territorial capital city i ...

's revolutionary botanical ideas to a wider public, and was followed by many later successes such as "The Country of the Blind

"The Country of the Blind" is a short story by English writer H. G. Wells. It was first published in the April 1904 issue of ''The Strand Magazine'' and included in a 1911 collection of Wells's short stories, ''The Country of the Blind and Ot ...

" (1904).

According to James E. Gunn, one of Wells's major contributions to the science fiction genre was his approach, which he referred to as his "new system of ideas". In his opinion, the author should always strive to make the story as credible as possible, even if both the writer and the reader knew certain elements are impossible, allowing the reader to accept the ideas as something that could really happen, today referred to as "the plausible impossible" and "suspension of disbelief

Suspension of disbelief, sometimes called willing suspension of disbelief, is the avoidance of critical thinking or logic in examining something unreal or impossible in reality, such as a work of speculative fiction, in order to believe it for ...

". While neither invisibility nor time travel was new in speculative fiction, Wells added a sense of realism to the concepts which the readers were not familiar with. He conceived the idea of using a vehicle that allows an operator to travel purposely and selectively forwards or backwards in time. The term "time machine

Time travel is the concept of movement between certain points in time, analogous to movement between different points in space by an object or a person, typically with the use of a hypothetical device known as a time machine. Time travel is a w ...

", coined by Wells, is now almost universally used to refer to such a vehicle. He explained that while writing ''The Time Machine'', he realized that "the more impossible the story I had to tell, the more ordinary must be the setting, and the circumstances in which I now set the Time Traveller were all that I could imagine of solid upper-class comforts." In "Wells's Law", a science fiction story should contain only a single extraordinary assumption. Therefore, as justifications for the impossible, he employed scientific ideas and theories. Wells's best-known statement of the "law" appears in his introduction to a collection of his works published in 1934:

As soon as the magic trick has been done the whole business of the fantasy writer is to keep everything else human and real. Touches of prosaic detail are imperative and a rigorous adherence to the hypothesis. Any extra fantasy outside the cardinal assumption immediately gives a touch of irresponsible silliness to the invention.Dr. Griffin / The Invisible Man is a brilliant research scientist who discovers a method of invisibility, but finds himself unable to reverse the process. An enthusiast of random and irresponsible violence, Griffin has become an iconic character in horror fiction. ''The Island of Doctor Moreau'' sees a shipwrecked man left on the island home of Doctor Moreau, a mad scientist who creates human-like hybrid beings from animals via vivisection. The earliest depiction of

uplift

Uplift may refer to: Science

* Geologic uplift, a geological process

** Tectonic uplift, a geological process

* Stellar uplift, the theoretical prospect of moving a stellar mass

* Uplift mountains

* Llano Uplift

* Nemaha Uplift

Business

* Uplif ...

, the novel deals with a number of philosophical themes, including pain and cruelty, moral responsibility, human identity, and human interference with nature. In ''The First Men in the Moon'' Wells used the idea of radio communication between astronomical object

An astronomical object, celestial object, stellar object or heavenly body is a naturally occurring physical entity, association, or structure that exists in the observable universe. In astronomy, the terms ''object'' and ''body'' are often us ...

s, a plot point inspired by Nikola Tesla's claim that he had received radio signals from Mars. In addition to science fiction, Wells produced work dealing with mythological beings like an angel in ''The Wonderful Visit

''The Wonderful Visit'' is an 1895 novel by H. G. Wells. With an angel—a creature of fantasy unlike a religious angel—as protagonist and taking place in contemporary England, the book could be classified as contemporary fantasy, although t ...

'' (1895) and a mermaid in ''The Sea Lady

''The Sea Lady'' is a fantasy novel by British writer H. G. Wells, including some of the aspects of a fable. It was serialized from July to December 1901 in ''Pearson's Magazine'' before being published as a volume by Methuen. The inspiratio ...

'' (1902).

Though ''Tono-Bungay'' is not a science-fiction novel, radioactive decay plays a small but consequential role in it. Radioactive decay plays a much larger role in '' The World Set Free'' (1914), a book dedicated to Frederick Soddy who would receive a Nobel for proving the existence of radioactive isotopes. This book contains what is surely Wells's biggest prophetic "hit", with the first description of a nuclear weapon (which he termed "atomic bombs"). Scientists of the day were well aware that the natural decay of radium releases energy at a slow rate over thousands of years. The ''rate'' of release is too slow to have practical utility, but the ''total amount'' released is huge. Wells's novel revolves around an (unspecified) invention that accelerates the process of radioactive decay, producing bombs that explode with no more than the force of ordinary high explosives—but which "continue to explode" for days on end. "Nothing could have been more obvious to the people of the earlier twentieth century, than the rapidity with which war was becoming impossible ... utthey did not see it until the atomic bombs burst in their fumbling hands". In 1932, the physicist and conceiver of nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series of these reactions. The specific nu ...

Leó Szilárd read ''The World Set Free'' (the same year Sir James Chadwick discovered the neutron), a book which he wrote in his memoirs had made "a very great impression on me." In 1934, Szilárd took his ideas for a chain reaction to the British War Office and later the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

* Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

*Admiralty, Tr ...

, assigning his patent to the Admiralty to keep the news from reaching the notice of the wider scientific community. He wrote, "Knowing what this chain reactionwould mean—and I knew it because I had read H. G. Wells—I did not want this patent to become public."

Wells also wrote non-fiction. His first non-fiction

Wells also wrote non-fiction. His first non-fiction bestseller

A bestseller is a book or other media noted for its top selling status, with bestseller lists published by newspapers, magazines, and book store chains. Some lists are broken down into classifications and specialties (novel, nonfiction book, cookb ...

was '' Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress upon Human Life and Thought'' (1901). When originally serialised in a magazine it was subtitled "An Experiment in Prophecy", and is considered his most explicitly futuristic

The future is the time after the past and present. Its arrival is considered inevitable due to the existence of time and the laws of physics. Due to the apparent nature of reality and the unavoidability of the future, everything that currently ...

work. It offered the immediate political message of the privileged sections of society continuing to bar capable men from other classes from advancement until war would force a need to employ those most able, rather than the traditional upper classes, as leaders. Anticipating what the world would be like in the year 2000, the book is interesting both for its hits (trains and cars resulting in the dispersion of populations from cities to suburbs; moral restrictions declining as men and women seek greater sexual freedom; the defeat of German militarism, and the existence of a European Union) and its misses (he did not expect successful aircraft before 1950, and averred that "my imagination refuses to see any sort of submarine doing anything but suffocate its crew and founder at sea").

His bestselling two-volume work, '' The Outline of History'' (1920), began a new era of popularised world history. It received a mixed critical response from professional historians. However, it was very popular amongst the general population and made Wells a rich man. Many other authors followed with "Outlines" of their own in other subjects. He reprised his ''Outline'' in 1922 with a much shorter popular work, '' A Short History of the World'', a history book praised by Albert Einstein, and two long efforts, ''The Science of Life

''The Science of Life'' is a book written by H. G. Wells, Julian Huxley and G. P. Wells, published in three volumes by The Waverley Publishing Company Ltd in 1929–30, giving a popular account of all major aspects of biology as known in the 1 ...

'' (1930)—written with his son G. P. Wells

George Philip Wells FRS (17 July 1901 – 27 September 1985) was a British zoologist and author. A son of the author H. G. Wells, he co-authored, with his father and Julian Huxley, ''The Science of Life''. A pupil at Oundle School, he was in t ...

and evolutionary biologist Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley (22 June 1887 – 14 February 1975) was an English evolutionary biologist, eugenicist, and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century modern synthesis. ...

, and ''The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind

''The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind'' by H. G. Wells is the final work of a trilogy of which the first volumes were ''The Outline of History'' (1919–1920) and '' The Science of Life'' (1929). Wells conceived of the three parts of his ...

'' (1931). The "Outlines" became sufficiently common for James Thurber to parody the trend in his humorous essay, "An Outline of Scientists"—indeed, Wells's ''Outline of History'' remains in print with a new 2005 edition, while ''A Short History of the World'' has been re-edited (2006).

From quite early in Wells's career, he sought a better way to organise society and wrote a number of Utopian novels. The first of these was '' A Modern Utopia'' (1905), which shows a worldwide utopia with "no imports but meteorites, and no exports at all"; two travellers from our world fall into its

From quite early in Wells's career, he sought a better way to organise society and wrote a number of Utopian novels. The first of these was '' A Modern Utopia'' (1905), which shows a worldwide utopia with "no imports but meteorites, and no exports at all"; two travellers from our world fall into its alternate history

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, altern ...

. The others usually begin with the world rushing to catastrophe, until people realise a better way of living: whether by mysterious gases from a comet causing people to behave rationally and abandoning a European war (''In the Days of the Comet

''In the Days of the Comet'' (1906) is a science fiction novel by H. G. Wells in which humanity is "exalted" when a comet causes "the nitrogen of the air, the old ''azote''," to "change out of itself" and become "a respirable gas, differing inde ...

'' (1906)), or a world council of scientists taking over, as in '' The Shape of Things to Come'' (1933, which he later adapted for the 1936 Alexander Korda film, '' Things to Come''). This depicted, all too accurately, the impending World War, with cities being destroyed by aerial bombs. He also portrayed the rise of fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

dictators in ''The Autocracy of Mr Parham'' (1930) and ''The Holy Terror'' (1939). ''Men Like Gods

''Men Like Gods'' (1923) is a novel, referred to by the author as a "scientific fantasy", by English writer H. G. Wells. It features a utopia located in a parallel universe.

Plot summary

''Men Like Gods'' is set in the summer of 1921. Its pr ...

'' (1923) is also a utopian novel. Wells in this period was regarded as an enormously influential figure; the literary critic Malcolm Cowley stated: "by the time he was forty, his influence was wider than any other living English writer".

Wells contemplates the ideas of nature and nurture

Nature versus nurture is a long-standing debate in biology and society about the balance between two competing factors which determine fate: genetics (nature) and environment (nurture). The alliterative expression "nature and nurture" in English h ...

and questions humanity in books such as ''The First Men in the Moon'', where nature is completely suppressed by nurture, and ''The Island of Doctor Moreau'', where the strong presence of nature represents a threat to a civilized society. Not all his scientific romances ended in a Utopia, and Wells also wrote a dystopia

A dystopia (from Ancient Greek δυσ- "bad, hard" and τόπος "place"; alternatively cacotopiaCacotopia (from κακός ''kakos'' "bad") was the term used by Jeremy Bentham in his 1818 Plan of Parliamentary Reform (Works, vol. 3, p. 493). ...

n novel, ''When the Sleeper Wakes'' (1899, rewritten as ''The Sleeper Awakes'', 1910), which pictures a future society where the classes have become more and more separated, leading to a revolt of the masses against the rulers. ''The Island of Doctor Moreau'' is even darker. The narrator, having been trapped on an island of animals vivisected (unsuccessfully) into human beings, eventually returns to England; like Gulliver on his return from the Houyhnhnm

Houyhnhnms are a fictional race of intelligent horses described in the last part of Jonathan Swift's satirical 1726 novel ''Gulliver's Travels''. The name is pronounced either or . Swift apparently intended all words of the Houyhnhnm language ...

s, he finds himself unable to shake off the perceptions of his fellow humans as barely civilised beasts, slowly reverting to their animal natures.Wells, H. G. (2005). ''The Island of Dr Moreau''. "Fear and Trembling". Penguin UK.

Wells also wrote the preface for the first edition of W. N. P. Barbellion

Wilhelm Nero Pilate Barbellion was the pen name of Bruce Frederick Cummings (7 September 1889 – 22 October 1919), an English diary, diarist who was responsible for ''The Journal of a Disappointed Man''. Ronald Blythe called it "among the most m ...

's diaries, ''The Journal of a Disappointed Man'', published in 1919. Since "Barbellion" was the real author's pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

, many reviewers believed Wells to have been the true author of the ''Journal''; Wells always denied this, despite being full of praise for the diaries.

In 1927, a Canadian teacher and writer

In 1927, a Canadian teacher and writer Florence Deeks

Florence Amelia Deeks (1864–1959) was a Canadian teacher and writer. She is known for accusing British author H. G. Wells of having plagiarized her work when he wrote ''The Outline of History''. The case was eventually taken to the Judicial Comm ...

unsuccessfully sued Wells for infringement of copyright and breach of trust, claiming that much of ''The Outline of History'' had been plagiarised from her unpublished manuscript, ''The Web of the World's Romance'', which had spent nearly nine months in the hands of Wells's Canadian publisher, Macmillan Canada. However, it was sworn on oath at the trial that the manuscript remained in Toronto in the safekeeping of Macmillan, and that Wells did not even know it existed, let alone seen it. The court found no proof of copying, and decided the similarities were due to the fact that the books had similar nature and both writers had access to the same sources. In 2000, A. B. McKillop

Alexander Brian McKillop (born 1946), known as A. B. McKillop or Brian McKillop, is Distinguished Research Professor and former Chancellor's Professor and Chair of the history department (2005–2009) of Carleton University in Ottawa, Ontario, Can ...

, a professor of history at Carleton University, produced a book on the case, ''The Spinster & The Prophet: Florence Deeks, H. G. Wells, and the Mystery of the Purloined Past''. According to McKillop, the lawsuit was unsuccessful due to the prejudice against a woman suing a well-known and famous male author, and he paints a detailed story based on the circumstantial evidence of the case. In 2004, Denis N. Magnusson, Professor Emeritus of the Faculty of Law, Queen's University, Ontario, published an article on ''Deeks v. Wells''. This re-examines the case in relation to McKillop's book. While having some sympathy for Deeks, he argues that she had a weak case that was not well presented, and though she may have met with sexism from her lawyers, she received a fair trial, adding that the law applied is essentially the same law that would be applied to a similar case today (i.e., 2004).

In 1933, Wells predicted in ''The Shape of Things to Come'' that the world war he feared would begin in January 1940, a prediction which ultimately came true four months early, in September 1939, with the outbreak of World War II. In 1936, before the

In 1933, Wells predicted in ''The Shape of Things to Come'' that the world war he feared would begin in January 1940, a prediction which ultimately came true four months early, in September 1939, with the outbreak of World War II. In 1936, before the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

, Wells called for the compilation of a constantly growing and changing World Encyclopaedia, to be reviewed by outstanding authorities and made accessible to every human being. In 1938, he published a collection of essays on the future organisation of knowledge and education, ''World Brain

''World Brain'' is a collection of essays and addresses by the English science fiction pioneer, social reformer, evolutionary biologist and historian H. G. Wells, dating from the period of 1936–1938.Wells, H.G. (1938). ''World Brain''. Lond ...

'', including the essay "The Idea of a Permanent World Encyclopaedia".

Prior to 1933, Wells's books were widely read in Germany and Austria, and most of his science fiction works had been translated shortly after publication. By 1933, he had attracted the attention of German officials because of his criticism of the political situation in Germany, and on 10 May 1933, Wells's books were burned by the Nazi youth in Berlin's Opernplatz, and his works were banned from libraries and book stores.Patrick Parrinder and John S. Partington (2005). ''The Reception of H. G. Wells in Europe''. pp. 106–108. Bloomsbury Publishing. Wells, as president of PEN International (Poets, Essayists, Novelists), angered the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

by overseeing the expulsion of the German PEN club from the international body in 1934 following the German PEN's refusal to admit non-Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ' ...

writers to its membership. At a PEN conference in Ragusa Ragusa is the historical name of Dubrovnik. It may also refer to:

Places Croatia

* the Republic of Ragusa (or Republic of Dubrovnik), the maritime city-state of Ragusa

* Cavtat (historically ' in Italian), a town in Dubrovnik-Neretva County, Cro ...

, Wells refused to yield to Nazi sympathisers who demanded that the exiled author Ernst Toller

Ernst Toller (1 December 1893 – 22 May 1939) was a German author, playwright, left-wing politician and revolutionary, known for his Expressionism (theatre), Expressionist plays. He served in 1919 for six days as President of the short-lived B ...

be prevented from speaking. Near the end of World War II, Allied forces discovered that the SS had compiled lists of people slated for immediate arrest during the invasion of Britain in the abandoned Operation Sea Lion, with Wells included in the alphabetical list of "The Black Book

Black Book, Black book or Blackbook may refer to:

Film

* ''Black Book'' (film), a 2006 Dutch thriller film by director Paul Verhoeven

** ''Black Book'' (soundtrack), soundtrack of the 2006 film

* ''The Black Book'' (serial), a 1929 American ...

".

Wartime works

pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

prior to the First World War, Wells stated "how much better is this amiable miniature arthan the real thing". According to Wells, the idea of the game developed from a visit by his friend Jerome K. Jerome. After dinner, Jerome began shooting down toy soldiers with a toy cannon and Wells joined in to compete.

During August 1914, immediately after the outbreak of the First World War, Wells published a number of articles in London newspapers that subsequently appeared as a book entitled ''The War That Will End War''. He coined the expression with the idealistic belief that the result of the war would make a future conflict impossible. Wells blamed the Central Powers for the coming of the war and argued that only the defeat of German militarism could bring about an end to war. Wells used the shorter form of the phrase, "the war to end war

"The war to end war" (also "The war to end all wars"; originally from the 1914 book '' The War That Will End War'' by H. G. Wells) is a term for the First World War of 1914–1918. Originally an idealistic slogan, it is now mainly used sardonic ...

", in ''In the Fourth Year'' (1918), in which he noted that the phrase "got into circulation" in the second half of 1914. In fact, it had become one of the most common catchphrases of the war.

In 1918 Wells worked for the British War Propaganda Bureau, also called Wellington House. Wells was also one of fifty-three leading British authors — a number that included Rudyard Kipling, Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Word ...

and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Ho ...

— who signed their names to the "Authors' Declaration." This manifesto declared that the German invasion of Belgium had been a brutal crime, and that Britain "could not without dishonour have refused to take part in the present war."

Travels to Russia and the Soviet Union

Wells visited Russia three times: 1914, 1920 and 1934. After his visit toPetrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

and Moscow, in January 1914, he returned "a staunch Russophile". He revealed his impressions in "Russia and England: A Study on Contrasts" in '' The Daily News'', on 1 February 1941 and in the novel '' Joan and Peter'' (1918). During his second visit, he saw his old friend Maxim Gorky and with Gorky's help, met Vladimir Lenin. In his book ''Russia in the Shadows

''Russia in the Shadows'' is a book by H. G. Wells published early in 1921, which includes a series of articles previously printed in ''The Sunday Express'' in connection with Wells's second visit to Russia (after a previous trip in January 1914 t ...

'', Wells portrayed Russia as recovering from a total social collapse, "the completest that has ever happened to any modern social organisation." On 23 July 1934, after visiting U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Wells went to the Soviet Union and interviewed Joseph Stalin for three hours for the '' New Statesman'' magazine, which was extremely rare at that time. He told Stalin how he had seen 'the happy faces of healthy people' in contrast with his previous visit to Moscow in 1920. However, he also criticised the lawlessness, class discrimination, state violence, and absence of free expression. Stalin enjoyed the conversation and replied accordingly. As the chairman of the London-based PEN International, which protected the rights of authors to write without being intimidated, Wells hoped by his trip to USSR, he could win Stalin over by force of argument. Before he left, he realised that no reform was to happen in the near future.

Final years

Wells's greatest literary output occurred before the First World War, which was lamented by younger authors whom he had influenced. In this connection,

Wells's greatest literary output occurred before the First World War, which was lamented by younger authors whom he had influenced. In this connection, George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitar ...

described Wells as "too sane to understand the modern world", and "since 1920 he has squandered his talents in slaying paper dragons." G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic. He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox". Of his writing style, ''Time'' observed: "Wh ...

quipped: "Mr Wells is a born storyteller who has sold his birthright for a pot of message".

Wells had diabetes, and was a co-founder in 1934 of The Diabetic Association (now Diabetes UK

Diabetes UK is a British-based patient, healthcare professional and research charity that has been described as "one of the foremost diabetes charities in the UK". The charity campaigns for improvements in the care and treatment of people with d ...

, the leading charity for people with diabetes in the UK).

On 28 October 1940, on the radio station KTSA in San Antonio, Texas, Wells took part in a radio interview with Orson Welles, who two years previously had performed a famous radio adaptation of ''The War of the Worlds''. During the interview, by Charles C Shaw, a KTSA radio host, Wells admitted his surprise at the sensation that resulted from the broadcast but acknowledged his debt to Welles for increasing sales of one of his "more obscure" titles.

Death

Wells died of unspecified causes on 13 August 1946, aged 79, at his home at 13 Hanover Terrace, overlooking Regent's Park, London. In his preface to the 1941 edition of ''

Wells died of unspecified causes on 13 August 1946, aged 79, at his home at 13 Hanover Terrace, overlooking Regent's Park, London. In his preface to the 1941 edition of ''The War in the Air

''The War in the Air: And Particularly How Mr. Bert Smallways Fared While It Lasted'' is a military science fiction novel written by H. G. Wells.

The novel was written in four months in 1907, and was serialized and published in 1908 in ''The ...

'', Wells had stated that his epitaph should be: "I told you so. You ''damned'' fools". Wells's body was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium on 16 August 1946; his ashes were subsequently scattered into the English Channel at Old Harry Rocks, the most eastern point of the Jurassic Coast and about 3.5 miles (5.6 km) from Swanage

Swanage () is a coastal town and civil parish in the south east of Dorset, England. It is at the eastern end of the Isle of Purbeck and one of its two towns, approximately south of Poole and east of Dorchester. In the 2011 census the civil ...

in Dorset.

A commemorative blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

in his honour was installed by the Greater London Council

The Greater London Council (GLC) was the top-tier local government administrative body for Greater London from 1965 to 1986. It replaced the earlier London County Council (LCC) which had covered a much smaller area. The GLC was dissolved in 198 ...

at his home in Regent's Park in 1966.

Futurist

A futurist and "visionary", Wells foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television, and something resembling the World Wide Web. Asserting that "Wells's visions of the future remain unsurpassed",

A futurist and "visionary", Wells foresaw the advent of aircraft, tanks, space travel, nuclear weapons, satellite television, and something resembling the World Wide Web. Asserting that "Wells's visions of the future remain unsurpassed", John Higgs

John Higgs is an English writer, novelist, journalist and cultural historian. The work of Higgs has been published in the form of novels (under the pseudonym JMR Higgs), biographies and works of cultural history.

In particular, Higgs has writt ...

, author of ''Stranger Than We Can Imagine: Making Sense of the Twentieth Century'', states that in the late 19th century Wells "saw the coming century clearer than anyone else. He anticipated wars in the air, the sexual revolution, motorised transport causing the growth of suburbs and a proto-Wikipedia he called the "world brain

''World Brain'' is a collection of essays and addresses by the English science fiction pioneer, social reformer, evolutionary biologist and historian H. G. Wells, dating from the period of 1936–1938.Wells, H.G. (1938). ''World Brain''. Lond ...

". In his novel ''The World Set Free'', he imagined an "atomic bomb" of terrifying power that would be dropped from aeroplanes. This was an extraordinary insight for an author writing in 1913, and it made a deep impression on Winston Churchill."

In 2011, Wells was among a group of science fiction writers featured in the ''Prophets of Science Fiction

''Prophets of Science Fiction'' is an American documentary television series produced and hosted by Ridley Scott for the Science Channel. The program premiered on .

The series covers the life and work of leading science fiction authors of the las ...

'' series, a show produced and hosted by film director Sir Ridley Scott

Sir Ridley Scott (born 30 November 1937) is a British film director and producer. Directing, among others, science fiction films, his work is known for its atmospheric and highly concentrated visual style. Scott has received many accolades thr ...

, which depicts how predictions influenced the development of scientific advancements by inspiring many readers to assist in transforming those futuristic visions into everyday reality. In a 2013 review of ''The Time Machine'' for the ''New Yorker'' magazine, Brad Leithauser writes, "At the base of Wells's great visionary exploit is this rational, ultimately scientific attempt to tease out the potential future consequences of present conditions—not as they might arise in a few years, or even decades, but millennia hence, epochs hence. He is world literature's Great Extrapolator. Like no other fiction writer before him, he embraced "deep time

Deep time is a term introduced and applied by John McPhee to the concept of geologic time in his book ''Basin and Range'' (1981), parts of which originally appeared in the ''New Yorker'' magazine.

The philosophical concept of geological time w ...

".

Political views

Wells was a socialist and a member of the Fabian Society.

Wells was a socialist and a member of the Fabian Society. Winston Churchill