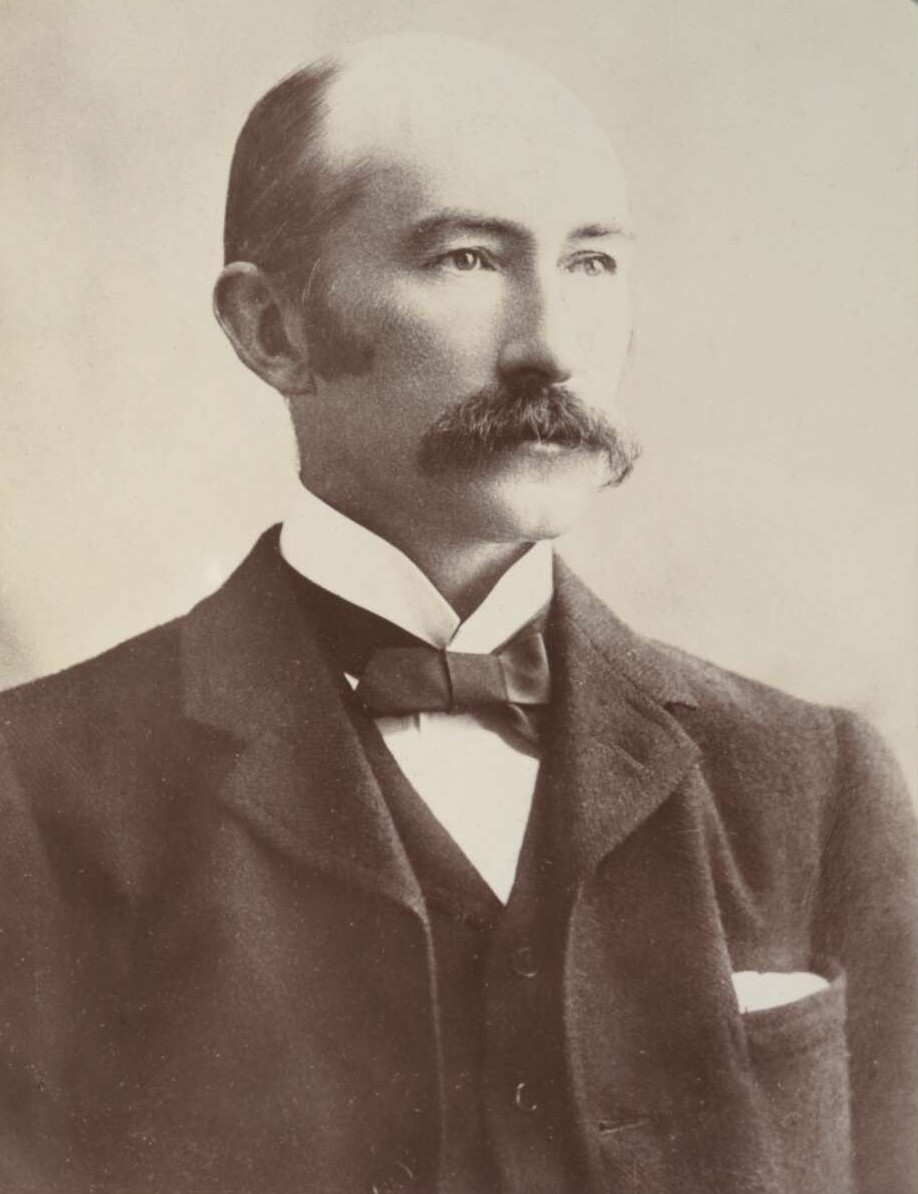

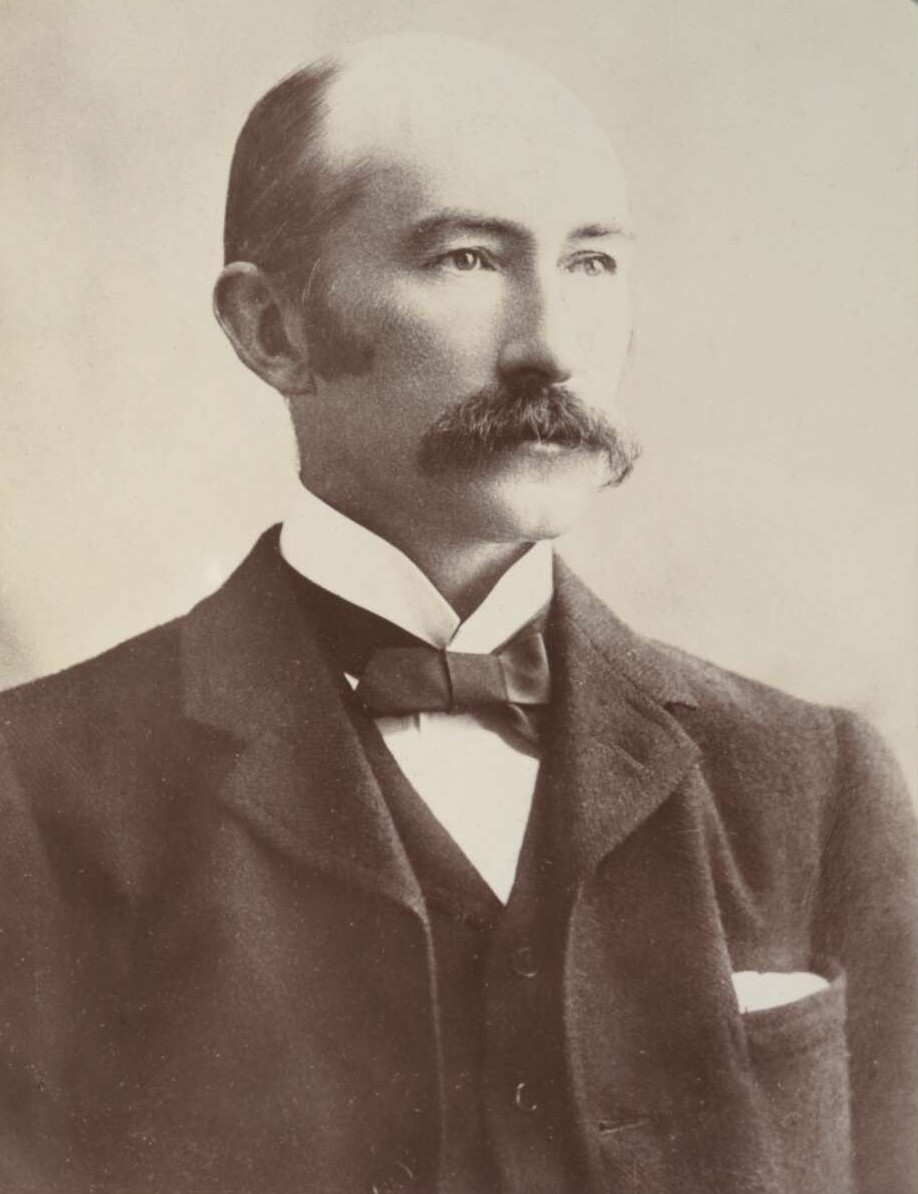

Henry Bournes Higgins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry Bournes Higgins KC (30 June 1851 – 13 January 1929) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge. He served on the

Despite these successes, he opposed the draft constitution produced by the convention as overly federalist, favouring instead unification, without a 'ridiculous' Senate. He also disdained the protectionist motive which he detected in the agitation for federation: the Victorian 'manufacturing classes', he wrote 'expected to exploit the markets of New South Wales, protected against the formidable competition of English and European goods'. He campaigned, unsuccessfully, to have the draft federal constitution defeated at the 1898 and 1899 Australian constitutional referendums. In November 1899 he supported the successful leadership challenge of Allan Maclean, a staunch anti-Federationist, to the premier, George Turner. These stances alienated him from most of his liberal colleagues, and also from the influential Melbourne newspaper, ''

Despite these successes, he opposed the draft constitution produced by the convention as overly federalist, favouring instead unification, without a 'ridiculous' Senate. He also disdained the protectionist motive which he detected in the agitation for federation: the Victorian 'manufacturing classes', he wrote 'expected to exploit the markets of New South Wales, protected against the formidable competition of English and European goods'. He campaigned, unsuccessfully, to have the draft federal constitution defeated at the 1898 and 1899 Australian constitutional referendums. In November 1899 he supported the successful leadership challenge of Allan Maclean, a staunch anti-Federationist, to the premier, George Turner. These stances alienated him from most of his liberal colleagues, and also from the influential Melbourne newspaper, ''

Higgins was an awkward colleague for the Protectionist leadership, and in 1906 Deakin appointed him as a Justice of the

Higgins was an awkward colleague for the Protectionist leadership, and in 1906 Deakin appointed him as a Justice of the

On 19 December 1885, Higgins married Mary Alice Morrison, the daughter of George Morrison, headmaster of

On 19 December 1885, Higgins married Mary Alice Morrison, the daughter of George Morrison, headmaster of

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is Australia's apex court. It exercises Original jurisdiction, original and appellate jurisdiction on matters specified within Constitution of Australia, Australia's Constitution.

The High Court was established fol ...

from 1906 until his death in 1929, after briefly serving as Attorney-General of Australia

The Attorney-GeneralThe title is officially "Attorney-General". For the purposes of distinguishing the office from other attorneys-general, and in accordance with usual practice in the United Kingdom and other common law jurisdictions, the Aust ...

in 1904.

Higgins was born in what is now Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

. He and his family emigrated to Australia when he was 18, and he found work as a schoolteacher while studying law part-time at the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb nor ...

. He was admitted to the Victorian Bar

The Victorian Bar is the bar association of the Australian State of Victoria. The current President of the Bar is Roisin Annesley KC. Its members are barristers registered to practice in Victoria. On 30 June 2020, there were 2,179 counsels ...

in 1876, and built up a substantial practice specialising in equity law

Equity is a particular body of law that was developed in the English Court of Chancery. Its general purpose is to provide a remedy for situations where the law is not flexible enough for the usual court system to deliver a fair resolution to a cas ...

. Higgins came to public attention as a prominent supporter of Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1 ...

. He was elected to the Victorian Legislative Assembly

The Victorian Legislative Assembly is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Victoria in Australia; the upper house being the Victorian Legislative Council. Both houses sit at Parliament House in Spring Street, Melbourne.

The presiding ...

in 1894, and represented Victoria at the Australasian Federal Convention

In Australian history, the term Constitutional Convention refers to four distinct gatherings.

1891 convention

The 1891 Constitutional Convention was held in Sydney in March 1891 to consider a draft Frame of Government for the proposed federation ...

, where he helped draft the new federal constitution. He nonetheless opposed the final draft, making him one of only two delegates to the convention to campaign against federation.

In 1901, Higgins was elected to the new federal parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the governor-gen ...

as a member of the Protectionist Party

The Protectionist Party or Liberal Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1887 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. The party advocated protective tariffs, arguing it would allow Australi ...

. He was sympathetic to the labour movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

, and in 1904 briefly served as Attorney-General in the Labor Party minority government led by Chris Watson

John Christian Watson (born Johan Cristian Tanck; 9 April 186718 November 1941) was an Australian politician who served as the third prime minister of Australia, in office from 27 April to 18 August 1904. He served as the inaugural federal lead ...

. In 1906, Prime Minister Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

decided to expand the High Court bench from three to five members, nominating Higgins and Isaac Isaacs

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs (6 August 1855 – 11 February 1948) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge who served as the ninth Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1931 to 1936. He had previously served on the High Court of A ...

to the court. Higgins was usually in the minority in his early years on the court, but in later years the composition of the court changed and he was more often in the majority. He also served as president of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration

The Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration was an Australian court that operated from 1904 to 1956 with jurisdiction to hear and arbitrate interstate industrial disputes, and to make awards. It also had the judicial functions of in ...

from 1907 to 1921. In that capacity, he wrote the decision in the influential ''Harvester case

''Ex parte H.V. McKay'',''Ex parte H.V. McKay'(1907) 2 CAR 1 commonly referred to as the ''Harvester case'', is a landmark Australian labour law decision of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration. The case arose under the ''Exci ...

'', holding that a legislative provision for a "fair and reasonable" wage effectively required a living wage

A living wage is defined as the minimum income necessary for a worker to meet their basic needs. This is not the same as a subsistence wage, which refers to a biological minimum, or a solidarity wage, which refers to a minimum wage tracking labor ...

.

Early life and education

He was born inNewtownards

Newtownards is a town in County Down, Northern Ireland. It lies at the most northern tip of Strangford Lough, 10 miles (16 km) east of Belfast, on the Ards Peninsula. It is in the Civil parishes in Ireland, civil parish of Newtownard ...

, County Down

County Down () is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It covers an area of and has a population of 531,665. It borders County Antrim to the ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, the son of The Rev.

The Reverend is an honorific style most often placed before the names of Christian clergy and ministers. There are sometimes differences in the way the style is used in different countries and church traditions. ''The Reverend'' is correctly ...

John Higgins, a Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

minister, and Anne Bournes, daughter of Henry Bournes of Crossmolina

Crossmolina is a town in the Barony of Tyrawley in County Mayo, Ireland, as well as the name of the parish in which Crossmolina is situated. The town sits on the River Deel near the northern shore of Lough Conn. Crossmolina is about west of ...

. Ina Higgins

Frances Georgina Watts Higgins (September 1860 – 1948), usually known as "Ina", was an Australian horticulturalist, landscape architect and feminist. She was the first female landscape architect in Victoria.

Ina Higgins was the daughter of ...

, an early feminist, was his sister and Nettie Palmer

Janet Gertrude "Nettie" Palmer (née Higgins) (18 August 1885 – 19 October 1964) was an Australian poet, essayist and Australia's leading literary critic of her day. She corresponded with women writers and collated the Centenary Gift Book which ...

, poet, essayist and literary critic, was a niece. The Rev. Higgins and his family emigrated to Australia in 1870.

H. B. Higgins was educated at Wesley College in central Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, Ireland, and at the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb nor ...

, where he graduated in law. He practised at the Melbourne bar from 1876, eventually becoming one of the city's leading barristers (a KC in 1903) and a wealthy man. He was active in liberal, radical, and Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

politics, as well as in many civic organisations. He was also a noted classical scholar

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

.

Colonial politics

In 1894, Higgins was elected to theVictorian Legislative Assembly

The Victorian Legislative Assembly is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Victoria in Australia; the upper house being the Victorian Legislative Council. Both houses sit at Parliament House in Spring Street, Melbourne.

The presiding ...

as MLA for Geelong

Geelong ( ) (Wathawurrung: ''Djilang''/''Djalang'') is a port city in the southeastern Australian state of Victoria, located at the eastern end of Corio Bay (the smaller western portion of Port Phillip Bay) and the left bank of Barwon River, ...

. He was a supporter of George Turner's liberal government, but frequently criticised it from a left-wing point of view. He supported advanced liberal positions, such as greater protection for workers, government investment in industry, and votes for women. In 1897, he was elected as one of Victoria's delegates to the convention which drew up the Australian Constitution

The Constitution of Australia (or Australian Constitution) is a constitutional document that is supreme law in Australia. It establishes Australia as a federation under a constitutional monarchy and outlines the structure and powers of the ...

, coming tenth of the ten successful candidates. At the convention, he successfully argued that the constitution should forbid the establishment of any religion, or the imposition of religious tests for the holding of government office. After being defeated at the Sydney and Adelaide sessions, he successfully moved at the Melbourne session the federal government be given the power to make laws for the conciliation and arbitration of industrial disputes 'extending beyond the limits of any one State'.

Despite these successes, he opposed the draft constitution produced by the convention as overly federalist, favouring instead unification, without a 'ridiculous' Senate. He also disdained the protectionist motive which he detected in the agitation for federation: the Victorian 'manufacturing classes', he wrote 'expected to exploit the markets of New South Wales, protected against the formidable competition of English and European goods'. He campaigned, unsuccessfully, to have the draft federal constitution defeated at the 1898 and 1899 Australian constitutional referendums. In November 1899 he supported the successful leadership challenge of Allan Maclean, a staunch anti-Federationist, to the premier, George Turner. These stances alienated him from most of his liberal colleagues, and also from the influential Melbourne newspaper, ''

Despite these successes, he opposed the draft constitution produced by the convention as overly federalist, favouring instead unification, without a 'ridiculous' Senate. He also disdained the protectionist motive which he detected in the agitation for federation: the Victorian 'manufacturing classes', he wrote 'expected to exploit the markets of New South Wales, protected against the formidable competition of English and European goods'. He campaigned, unsuccessfully, to have the draft federal constitution defeated at the 1898 and 1899 Australian constitutional referendums. In November 1899 he supported the successful leadership challenge of Allan Maclean, a staunch anti-Federationist, to the premier, George Turner. These stances alienated him from most of his liberal colleagues, and also from the influential Melbourne newspaper, ''The Age

''The Age'' is a daily newspaper in Melbourne, Australia, that has been published since 1854. Owned and published by Nine Entertainment, ''The Age'' primarily serves Victoria (Australia), Victoria, but copies also sell in Tasmania, the Austral ...

''. Higgins also opposed Australian involvement in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

, a very unpopular stand at the time, and as a result, he lost his seat at the 1900 Victorian election.

Federal politics

In 1901, when federation under the new constitution came into effect, Higgins was elected to the firstHouse of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

for the working-class electorate of Northern Melbourne. He stood as a Protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

, but the Labor Party did not oppose him, regarding him as a supporter of the labour movement. The Labor Party's confidence in him was shown in 1904, when Chris Watson

John Christian Watson (born Johan Cristian Tanck; 9 April 186718 November 1941) was an Australian politician who served as the third prime minister of Australia, in office from 27 April to 18 August 1904. He served as the inaugural federal lead ...

formed the first federal Labor government. Since the party did not have a suitably qualified lawyer, Watson offered the post of Attorney-General to Higgins. He is the only person to have held office in a federal Labor government without being a member of the Labor Party.

Robert Garran

Sir Robert Randolph Garran (10 February 1867 – 11 January 1957) was an Australian lawyer who became "Australia's first public servant" – the first federal government employee after the federation of the Australian colonies. He served as th ...

, the Secretary of the Attorney-General's Department, found Higgins difficult to work with, stating that "for the first week or two I could not induce him to sign even the most routine and trivial paper until after a full explanation ..the slowing-up of the machine was often embarrassing". Higgins also received criticism for his failure to regularly attend parliament, which left Watson and Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

having to explain his ministerial actions. ''The Melbourne Argus

''The Argus'' was an Australian daily morning newspaper in Melbourne from 2 June 1846 to 19 January 1957, and was considered to be the general Australian newspaper of record for this period. Widely known as a conservative newspaper for most ...

'' remarked that he "attends sometimes for prayers and retires spiritually refreshed". He was also attacked by '' The Bulletin'', which observed that he "has had an unparalleled opportunity to demonstrate his worth as legal ally of the Government, and all the demonstration that he has effected in the House could be contained in a paper bag". According to Ross McMullin

Ross McMullin (born 1952) is an Australian historian who has written a number of books on political and social history, as well as several biographies.

McMullin was educated at the University of Melbourne, where he wrote his Master of Arts thes ...

, Higgins "approved of the Labor Party and its objectives ..but he remained outside the party and did not identify himself with it". However, his contributions to cabinet discussions were appreciated by his colleagues, and Watson was happy to defend him against the attacks from the media.

High Court

Higgins was an awkward colleague for the Protectionist leadership, and in 1906 Deakin appointed him as a Justice of the

Higgins was an awkward colleague for the Protectionist leadership, and in 1906 Deakin appointed him as a Justice of the High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is Australia's apex court. It exercises Original jurisdiction, original and appellate jurisdiction on matters specified within Constitution of Australia, Australia's Constitution.

The High Court was established fol ...

as a means of getting him out of politics, although he was undoubtedly qualified for the post. In 1907, he was also appointed President of the newly created Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration

The Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration was an Australian court that operated from 1904 to 1956 with jurisdiction to hear and arbitrate interstate industrial disputes, and to make awards. It also had the judicial functions of in ...

, created to arbitrate disputes between trades unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

and employers, something Higgins had long advocated. In this role, he continued to support the labour movement, although he was strongly opposed to militant unions who abused the strike weapon and ignored his rulings.

Higgins was one of only eight justices of the High Court to have served in the Parliament of Australia

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislature, legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the ...

prior to his appointment to the Court; the others were Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund "Toby" Barton, (18 January 18497 January 1920) was an Australian politician and judge who served as the first prime minister of Australia from 1901 to 1903, holding office as the leader of the Protectionist Party. He resigned to ...

, Richard O'Connor

General Sir Richard Nugent O'Connor, (21 August 1889 – 17 June 1981) was a senior British Army officer who fought in both the First and Second World Wars, and commanded the Western Desert Force in the early years of the Second World War. He ...

, Isaac Isaacs

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs (6 August 1855 – 11 February 1948) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge who served as the ninth Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1931 to 1936. He had previously served on the High Court of A ...

, Edward McTiernan

Sir Edward Aloysius McTiernan, KBE (16 February 1892 – 9 January 1990), was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge. He served on the High Court of Australia from 1930 to 1976, the longest-serving judge in the court's history.

McTiernan ...

, John Latham, Garfield Barwick

Sir Garfield Edward John Barwick, (22 June 190313 July 1997) was an Australian judge who was the seventh and longest serving Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1964 to 1981. He had earlier been a Liberal Party politician, serving as a ...

, and Lionel Murphy

Lionel Keith Murphy QC (30 August 1922 – 21 October 1986) was an Australian politician, barrister, and judge. He was a Senator for New South Wales from 1962 to 1975, serving as Attorney-General in the Whitlam Government, and then sat on the ...

. He was also one of two justices to have served in the Parliament of Victoria

The Parliament of Victoria is the bicameral legislature of the Australian state of Victoria that follows a Westminster-derived parliamentary system. It consists of the King, represented by the Governor of Victoria, the Legislative Assembly and ...

, along with Isaac Isaacs

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs (6 August 1855 – 11 February 1948) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge who served as the ninth Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1931 to 1936. He had previously served on the High Court of A ...

.

Harvester case

In 1907, Higgins delivered a judgement which became famous in Australian history, known as the "Harvester Judgement

''Ex parte H.V. McKay'',''Ex parte H.V. McKay'(1907) 2 CAR 1 commonly referred to as the ''Harvester case'', is a landmark Australian labour law decision of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration. The case arose under the ''Exc ...

". The case involved one of Australia's largest employers, Hugh McKay, a manufacturer of agricultural machinery. Higgins ruled that McKay was obliged to pay his employees a wage that guaranteed them a standard of living that was reasonable for "a human being in a civilised community", regardless of his capacity to pay. This gave rise to the legal requirement for a basic wage

A living wage is defined as the minimum income necessary for a worker to meet their basic needs. This is not the same as a subsistence wage, which refers to a biological minimum, or a solidarity wage, which refers to a minimum wage tracking labor ...

, which dominated Australian economic life for the next 80 years.T.J. Kearney, The life and times of Henry Bournes Higgins, politician and judge (1851-1929), ''Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society'', 11 (1989), 33-43.

World War I

During World War I, Higgins increasingly came into conflict with theNationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

Prime Minister Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

, whom he saw as using the wartime emergency to erode civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

. Although Higgins initially supported the war, he opposed the extension of government power that came with it, and also opposed Hughes' attempt to introduce conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

for the war. In 1916, his only son Mervyn was killed in action in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, a tragedy which made Higgins turn increasingly against the war.

Final years

The postwar years saw a series of bitter industrial confrontations, some of them fomented by militant unions influenced by theIndustrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines genera ...

or the Communist Party of Australia

The Communist Party of Australia (CPA), known as the Australian Communist Party (ACP) from 1944 to 1951, was an Australian political party founded in 1920. The party existed until roughly 1991, with its membership and influence having been i ...

. Higgins defended the principles of arbitration against both the Hughes Government and militant unions, although he found this increasingly difficult. Postwar governments appointed conservative justices to the High Court, leaving Higgins increasingly more isolated. In 1920, he resigned from the Arbitration Court in frustration, but remained on the High Court bench until his death in 1929. In 1922, he published ''A New Province for Law and Order'', a defence of his views and record on arbitration.

Personal life

On 19 December 1885, Higgins married Mary Alice Morrison, the daughter of George Morrison, headmaster of

On 19 December 1885, Higgins married Mary Alice Morrison, the daughter of George Morrison, headmaster of Geelong College

, motto_translation = Thus one goes to the stars

, established =

, type = Independent, co-educational, day and boarding, Christian school

, denomination = in association with the Uniting ...

, and the sister of the journalist George Ernest Morrison

George Ernest Morrison (4 February 1862 – 30 May 1920) was an Australian journalist, political adviser to and representative of the government of the Republic of China during the First World War and owner of the then largest Asiatic library ...

. Their only child, Mervyn Bournes Higgins, was born in 1887, and was killed in action in Egypt in 1916.

After his son Mervyn's death, Higgins effectively adopted his nephew Esmonde Higgins

Esmonde Macdonald Higgins (26 March 1897 - 25 December 1960) was an Australian political activist and adult education proponent. He was a prominent figure in the early years of the Communist Party of Australia, serving as editor of its official ...

, and his niece Nettie Palmer

Janet Gertrude "Nettie" Palmer (née Higgins) (18 August 1885 – 19 October 1964) was an Australian poet, essayist and Australia's leading literary critic of her day. She corresponded with women writers and collated the Centenary Gift Book which ...

, paying for their education at universities in Europe. He was pained by Esmonde's conversion to Communism in 1920 and his rejection of the liberal values associated with the Higgins name.

Aside from politics, he was president of the Carlton Football Club

The Carlton Football Club, nicknamed the Blues, is a professional Australian rules football club that competes in the Australian Football League (AFL), the sport's top professional competition.

Founded in 1864 in Carlton, an inner suburb of Mel ...

in 1904.

Legacy

Higgins was remembered for many years as a great friend of the labour movement, of the Irish-Australian community and of liberal and progressive causes generally. He was well-served by his first biographer, his niece Nettie Palmer, whose ''Henry Bournes Higgins: A Memoir'' (1931) created an enduring Higgins mythology. John Rickard's 1984 ''H. B. Higgins: The Rebel as Judge'' partly demolished this myth, but was a generally sympathetic biography. The H.B. Higgins Chambers in Sydney, founded by radical industrial lawyers, is named for him. Further, Higgins is commemorated by the federal electorate of Higgins in Melbourne, and by theCanberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

suburb of Higgins, Australian Capital Territory

Higgins is a suburb in the Belconnen district of Canberra, in the Australian Capital Territory, Australia. The suburb is named after politician and judge Henry Bournes Higgins (1851–1929). It was gazetted on 6 June 1968. The streets of Higgi ...

.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Higgins, Henry 1851 births 1929 deaths Attorneys-General of Australia Justices of the High Court of Australia Lawyers from Melbourne Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Northern Melbourne Members of the Cabinet of Australia Politicians from County Mayo Protectionist Party members of the Parliament of Australia Melbourne Law School alumni People educated at Wesley College, Dublin Australian King's Counsel Carlton Football Club administrators 20th-century Australian politicians Irish emigrants to colonial Australia University of Melbourne alumni