Hemingway family on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899, in

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899, in  Hemingway's mother, a well-known musician in the village,Reynolds (2000), 19 taught her son to play the cello despite his refusal to learn; though later in life he admitted the music lessons contributed to his writing style, evidenced for example in the "

Hemingway's mother, a well-known musician in the village,Reynolds (2000), 19 taught her son to play the cello despite his refusal to learn; though later in life he admitted the music lessons contributed to his writing style, evidenced for example in the "

In December 1917, after being rejected by the U.S. Army for poor eyesight, Hemingway responded to a Red Cross recruitment effort and signed on to be an ambulance driver in Italy, In May 1918, he sailed from New York, and arrived in Paris as the city was under bombardment from German artillery.Meyers (1985), 27–31 That June he arrived at the Italian Front. On his first day in

In December 1917, after being rejected by the U.S. Army for poor eyesight, Hemingway responded to a Red Cross recruitment effort and signed on to be an ambulance driver in Italy, In May 1918, he sailed from New York, and arrived in Paris as the city was under bombardment from German artillery.Meyers (1985), 27–31 That June he arrived at the Italian Front. On his first day in  On July 8, he was seriously wounded by mortar fire, having just returned from the canteen bringing chocolate and cigarettes for the men at the front line. Despite his wounds, Hemingway assisted Italian soldiers to safety, for which he was decorated with the Italian War Merit Cross, the ''Croce al Merito di Guerra''.On awarding the medal, the Italians wrote of Hemingway: "Gravely wounded by numerous pieces of shrapnel from an enemy shell, with an admirable spirit of brotherhood, before taking care of himself, he rendered generous assistance to the Italian soldiers more seriously wounded by the same explosion and did not allow himself to be carried elsewhere until after they had been evacuated." See Mellow (1992), p. 61 He was still only 18 at the time. Hemingway later said of the incident: "When you go to war as a boy you have a great illusion of immortality. Other people get killed; not you ... Then when you are badly wounded the first time you lose that illusion and you know it can happen to you." He sustained severe shrapnel wounds to both legs, underwent an immediate operation at a distribution center, and spent five days at a field hospital before he was transferred for recuperation to the Red Cross hospital in Milan.Desnoyers, 3 He spent six months at the hospital, where he met and formed a strong friendship with "Chink" Dorman-Smith that lasted for decades and shared a room with future American

On July 8, he was seriously wounded by mortar fire, having just returned from the canteen bringing chocolate and cigarettes for the men at the front line. Despite his wounds, Hemingway assisted Italian soldiers to safety, for which he was decorated with the Italian War Merit Cross, the ''Croce al Merito di Guerra''.On awarding the medal, the Italians wrote of Hemingway: "Gravely wounded by numerous pieces of shrapnel from an enemy shell, with an admirable spirit of brotherhood, before taking care of himself, he rendered generous assistance to the Italian soldiers more seriously wounded by the same explosion and did not allow himself to be carried elsewhere until after they had been evacuated." See Mellow (1992), p. 61 He was still only 18 at the time. Hemingway later said of the incident: "When you go to war as a boy you have a great illusion of immortality. Other people get killed; not you ... Then when you are badly wounded the first time you lose that illusion and you know it can happen to you." He sustained severe shrapnel wounds to both legs, underwent an immediate operation at a distribution center, and spent five days at a field hospital before he was transferred for recuperation to the Red Cross hospital in Milan.Desnoyers, 3 He spent six months at the hospital, where he met and formed a strong friendship with "Chink" Dorman-Smith that lasted for decades and shared a room with future American

Pfeiffer, who was from a wealthy

Pfeiffer, who was from a wealthy

Hemingway and Pauline traveled to Kansas City, where their son

Hemingway and Pauline traveled to Kansas City, where their son  His third child,

His third child,

"Hemingway legacy feud 'resolved'"

. BBC News. October 3, 2003. Retrieved April 26, 2011. Pauline's uncle bought the couple a

In 1937, Hemingway left for Spain to cover the

In 1937, Hemingway left for Spain to cover the

Hemingway was in Europe from May 1944 to March 1945. When he arrived in London, he met ''

Hemingway was in Europe from May 1944 to March 1945. When he arrived in London, he met ''

In October 1954, Hemingway received the

In October 1954, Hemingway received the

Hemingway and Mary left Cuba for the last time on July 25, 1960. He set up a small office in his New York City apartment and attempted to work, but he left soon after. He then traveled alone to Spain to be photographed for the front cover of ''Life'' magazine. A few days later, the news reported that he was seriously ill and on the verge of dying, which panicked Mary until she received a cable from him telling her, "Reports false. Enroute Madrid. Love Papa." He was, in fact, seriously ill, and believed himself to be on the verge of a breakdown. Feeling lonely, he took to his bed for days, retreating into silence, despite having the first installments of ''The Dangerous Summer'' published in ''Life'' in September 1960 to good reviews.Mellow (1992), 598–601 In October, he left Spain for New York, where he refused to leave Mary's apartment, presuming that he was being watched. She quickly took him to Idaho, where physician George Saviers met them at the train.

At this time, Hemingway was constantly worried about money and his safety. He worried about his taxes and that he would never return to Cuba to retrieve the manuscripts that he had left in a bank vault. He became paranoid, thinking that the FBI was actively monitoring his movements in Ketchum.Reynolds (1999), 548 The FBI had, in fact, opened a file on him during World War II, when he used the ''Pilar'' to patrol the waters off Cuba, and

Hemingway and Mary left Cuba for the last time on July 25, 1960. He set up a small office in his New York City apartment and attempted to work, but he left soon after. He then traveled alone to Spain to be photographed for the front cover of ''Life'' magazine. A few days later, the news reported that he was seriously ill and on the verge of dying, which panicked Mary until she received a cable from him telling her, "Reports false. Enroute Madrid. Love Papa." He was, in fact, seriously ill, and believed himself to be on the verge of a breakdown. Feeling lonely, he took to his bed for days, retreating into silence, despite having the first installments of ''The Dangerous Summer'' published in ''Life'' in September 1960 to good reviews.Mellow (1992), 598–601 In October, he left Spain for New York, where he refused to leave Mary's apartment, presuming that he was being watched. She quickly took him to Idaho, where physician George Saviers met them at the train.

At this time, Hemingway was constantly worried about money and his safety. He worried about his taxes and that he would never return to Cuba to retrieve the manuscripts that he had left in a bank vault. He became paranoid, thinking that the FBI was actively monitoring his movements in Ketchum.Reynolds (1999), 548 The FBI had, in fact, opened a file on him during World War II, when he used the ''Pilar'' to patrol the waters off Cuba, and  Family and friends flew to Ketchum for the funeral, officiated by the local Catholic priest, who believed that the death had been accidental. An altar boy fainted at the head of the casket during the funeral, and Hemingway's brother Leicester wrote: "It seemed to me Ernest would have approved of it all." He is buried in the Ketchum cemetery.

Hemingway's behavior during his final years had been similar to that of his father before he killed himself;Burwell (1996), 234 his father may have had

Family and friends flew to Ketchum for the funeral, officiated by the local Catholic priest, who believed that the death had been accidental. An altar boy fainted at the head of the casket during the funeral, and Hemingway's brother Leicester wrote: "It seemed to me Ernest would have approved of it all." He is buried in the Ketchum cemetery.

Hemingway's behavior during his final years had been similar to that of his father before he killed himself;Burwell (1996), 234 his father may have had

. (October 31, 1926). ''

novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living writing novels and other fiction, while others aspire to ...

, short-story writer

A short story is a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the oldest ...

, and journalist

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalism ...

. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory

The iceberg theory or theory of omission is a writing technique coined by American writer Ernest Hemingway. As a young journalist, Hemingway had to focus his newspaper reports on immediate events, with very little context or interpretation. When h ...

—had a strong influence on 20th-century fiction, while his adventurous lifestyle and public image brought him admiration from later generations. Hemingway produced most of his work between the mid-1920s and the mid-1950s, and he was awarded the 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature. He published seven novels, six short-story collections, and two nonfiction works. Three of his novels, four short-story collections, and three nonfiction works were published posthumously. Many of his works are considered classics of American literature

American literature is literature written or produced in the United States of America and in the colonies that preceded it. The American literary tradition thus is part of the broader tradition of English-language literature, but also inc ...

.

Hemingway was raised in Oak Park, Illinois

Oak Park is a village in Cook County, Illinois, adjacent to Chicago. It is the 29th-most populous municipality in Illinois with a population of 54,583 as of the 2020 U.S. Census estimate. Oak Park was first settled in 1835 and later incorporated in ...

. After high school, he was a reporter for a few months for ''The Kansas City Star

''The Kansas City Star'' is a newspaper based in Kansas City, Missouri. Published since 1880, the paper is the recipient of eight Pulitzer Prizes. ''The Star'' is most notable for its influence on the career of President Harry S. Truman and as ...

'' before leaving for the Italian Front to enlist as an ambulance driver in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. In 1918, he was seriously wounded and returned home. His wartime experiences formed the basis for his novel ''A Farewell to Arms

''A Farewell to Arms'' is a novel by American writer Ernest Hemingway, set during the Italian campaign of World War I. First published in 1929, it is a first-person account of an American, Frederic Henry, serving as a lieutenant () in the am ...

'' (1929).

In 1921, he married Hadley Richardson

Elizabeth Hadley Richardson (November 9, 1891 – January 22, 1979) was the first wife of American author Ernest Hemingway. The two married in 1921 after a courtship of less than a year, and moved to Paris within months of being married. In Paris, ...

, the first of four wives. They moved to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, where he worked as a foreign correspondent

A correspondent or on-the-scene reporter is usually a journalist or commentator for a magazine, or an agent who contributes reports to a newspaper, or radio or television news, or another type of company, from a remote, often distant, locati ...

and fell under the influence of the modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

writers and artists of the 1920s' "Lost Generation

The Lost Generation was the social generational cohort in the Western world that was in early adulthood during World War I. "Lost" in this context refers to the "disoriented, wandering, directionless" spirit of many of the war's survivors in the ...

" expatriate community. Hemingway's debut novel

A debut novel is the first novel a novelist publishes. Debut novels are often the author's first opportunity to make an impact on the publishing industry, and thus the success or failure of a debut novel can affect the ability of the author to p ...

''The Sun Also Rises

''The Sun Also Rises'' is a 1926 novel by American writer Ernest Hemingway, his first, that portrays American and British expatriates who travel from Paris to the Festival of San Fermín in Pamplona to watch the running of the bulls and the bu ...

'' was published in 1926. He divorced Richardson in 1927, and married Pauline Pfeiffer

Pauline Marie Pfeiffer (July 22, 1895 – October 1, 1951) was an American journalist, and the second wife of writer Ernest Hemingway.Harris, Peggy (Associated Press) (30 July 2000)Ernest Hemingway Museum Popular in Quiet Farm Town ''The Tusc ...

. They divorced after he returned from the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

(1936–1939), which he covered as a journalist and which was the basis for his novel ''For Whom the Bell Tolls

''For Whom the Bell Tolls'' is a novel by Ernest Hemingway published in 1940. It tells the story of Robert Jordan, a young American volunteer attached to a Republican guerrilla unit during the Spanish Civil War. As a dynamiter, he is assigned ...

'' (1940). Martha Gellhorn

Martha Ellis Gellhorn (8 November 1908 – 15 February 1998) was an American novelist, travel writer, and journalist who is considered one of the great war correspondents of the 20th century.

Gellhorn reported on virtually every major worl ...

became his third wife in 1940. He and Gellhorn separated after he met Mary Welsh

Air Chief Commandant Dame Ruth Mary Eldridge Welsh, (née Dalzell; 2 August 1896 – 25 June 1986), known as Mary Welsh, was second Director of the British Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), from 1943 to 1946.

Early life

Ruth Mary Eldridge Da ...

in London during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Hemingway was present with Allied troops as a journalist at the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

and the liberation of Paris

The liberation of Paris (french: Libération de Paris) was a military battle that took place during World War II from 19 August 1944 until the German garrison surrendered the French capital on 25 August 1944. Paris had been occupied by Nazi Germ ...

.

He maintained permanent residences in Key West, Florida

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Sigsbee Park, Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Isla ...

(in the 1930s) and in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

(in the 1940s and 1950s). He almost died in 1954 after two plane crashes on successive days, with injuries leaving him in pain and ill health for much of the rest of his life. In 1959, he bought a house in Ketchum, Idaho, where, in mid-1961, he died by suicide.

Life

Early life

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899, in

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois

Oak Park is a village in Cook County, Illinois, adjacent to Chicago. It is the 29th-most populous municipality in Illinois with a population of 54,583 as of the 2020 U.S. Census estimate. Oak Park was first settled in 1835 and later incorporated in ...

, an affluent suburb just west of Chicago, to Clarence Edmonds Hemingway, a physician, and Grace Hall Hemingway

Grace Ernestine Hall Hemingway ( Hall; June 15, 1872 – June 28, 1951) was an American opera singer, music teacher, and painter. She was Ernest Hemingway's mother.

Early life

Grace Ernestine Hall was born on June 15, 1872 in Chicago. ...

, a musician. His parents were well-educated and well-respected in Oak Park,Reynolds (2000), 17–18 a conservative community about which resident Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, designer, writer, and educator. He designed more than 1,000 structures over a creative period of 70 years. Wright played a key role in the architectural movements o ...

said, "So many churches for so many good people to go to." When Clarence and Grace Hemingway married in 1896, they lived with Grace's father, Ernest Miller Hall, after whom they named their first son, the second of their six children. His sister Marcelline preceded him in 1898, followed by Ursula in 1902, Madelaine in 1904, Carol in 1911, and Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

in 1915. Grace followed the Victorian convention of not differentiating children's clothing by gender. With only a year separating the two, Ernest and Marcelline resembled one-another strongly. Grace wanted them to appear as twins, so in Ernest's first three years she kept his hair long and dressed both children in similarly frilly feminine clothing.

Hemingway's mother, a well-known musician in the village,Reynolds (2000), 19 taught her son to play the cello despite his refusal to learn; though later in life he admitted the music lessons contributed to his writing style, evidenced for example in the "

Hemingway's mother, a well-known musician in the village,Reynolds (2000), 19 taught her son to play the cello despite his refusal to learn; though later in life he admitted the music lessons contributed to his writing style, evidenced for example in the "contrapuntal

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

structure" of ''For Whom the Bell Tolls

''For Whom the Bell Tolls'' is a novel by Ernest Hemingway published in 1940. It tells the story of Robert Jordan, a young American volunteer attached to a Republican guerrilla unit during the Spanish Civil War. As a dynamiter, he is assigned ...

''. As an adult Hemingway professed to hate his mother, although biographer Michael S. Reynolds points out that he shared similar energies and enthusiasms.

Each summer the family traveled to Windemere on Walloon Lake

Walloon Lake is a glacier-formed lake located in Charlevoix and Emmet counties, just southwestward from the northern tip of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan. It is now home to many vacation homes and cottages. Though the end of the west arm of th ...

, near Petoskey, Michigan

Petoskey ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is the county seat and largest city in Emmet County. Part of Northern Michigan, Petoskey is a popular Midwestern resort town, as it sits on the shore of Little Traverse Bay, a bay of La ...

. There young Ernest joined his father and learned to hunt, fish, and camp in the woods and lakes of Northern Michigan

Northern Michigan, also known as Northern Lower Michigan (known colloquially to residents of more southerly parts of the state and summer residents from cities such as Detroit as " Up North"), is a region of the U.S. state of Michigan. A popul ...

, early experiences that instilled a life-long passion for outdoor adventure and living in remote or isolated areas.Beegel (2000), 63–71

Hemingway attended Oak Park and River Forest High School

, motto_translation = Those things that are best

, address = 201 N. Scoville Avenue

, location =

, region =

, town = Oak Park

, county =

, state ...

in Oak Park from 1913 until 1917. He was a good athlete, involved with a number of sports—boxing, track and field, water polo, and football; performed in the school orchestra for two years with his sister Marcelline; and received good grades in English classes. During his last two years at high school he edited the ''Trapeze'' and ''Tabula'' (the school's newspaper and yearbook), where he imitated the language of sportswriters and used the pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

Ring Lardner Jr.—a nod to Ring Lardner

Ringgold Wilmer Lardner (March 6, 1885 – September 25, 1933) was an American sports columnist and short story writer best known for his satirical writings on sports, marriage, and the theatre. His contemporaries Ernest Hemingway, Virginia Wo ...

of the ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television ar ...

'' whose byline was "Line O'Type". Like Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

, Stephen Crane

Stephen Crane (November 1, 1871 – June 5, 1900) was an American poet, novelist, and short story writer. Prolific throughout his short life, he wrote notable works in the Realist tradition as well as early examples of American Naturalism an ...

, Theodore Dreiser

Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser (; August 27, 1871 – December 28, 1945) was an American novelist and journalist of the naturalist school. His novels often featured main characters who succeeded at their objectives despite a lack of a firm mora ...

, and Sinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American writer and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was ...

, Hemingway was a journalist before becoming a novelist. After leaving high school he went to work for ''The Kansas City Star

''The Kansas City Star'' is a newspaper based in Kansas City, Missouri. Published since 1880, the paper is the recipient of eight Pulitzer Prizes. ''The Star'' is most notable for its influence on the career of President Harry S. Truman and as ...

'' as a cub reporter.Meyers (1985), 19–23 Although he stayed there for only six months, he relied on the ''Star''s style guide

A style guide or manual of style is a set of standards for the writing, formatting, and design of documents. It is often called a style sheet, although that term also has multiple other meanings. The standards can be applied either for gene ...

as a foundation for his writing: "Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be positive, not negative."

World War I

In December 1917, after being rejected by the U.S. Army for poor eyesight, Hemingway responded to a Red Cross recruitment effort and signed on to be an ambulance driver in Italy, In May 1918, he sailed from New York, and arrived in Paris as the city was under bombardment from German artillery.Meyers (1985), 27–31 That June he arrived at the Italian Front. On his first day in

In December 1917, after being rejected by the U.S. Army for poor eyesight, Hemingway responded to a Red Cross recruitment effort and signed on to be an ambulance driver in Italy, In May 1918, he sailed from New York, and arrived in Paris as the city was under bombardment from German artillery.Meyers (1985), 27–31 That June he arrived at the Italian Front. On his first day in Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

, he was sent to the scene of a munitions factory explosion to join rescuers retrieving the shredded remains of female workers. He described the incident in his 1932 non-fiction book ''Death in the Afternoon

''Death in the Afternoon'' is a non-fiction book written by Ernest Hemingway about the ceremony and traditions of Spanish bullfighting, published in 1932. The book provides a look at the history and the Spanish traditions of bullfighting. It al ...

'': "I remember that after we searched quite thoroughly for the complete dead we collected fragments."Mellow (1992), 57–60 A few days later, he was stationed at Fossalta di Piave

Fossalta di Piave is a town in the Metropolitan City of Venice, Veneto, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterra ...

.Mellow (1992), 57–60

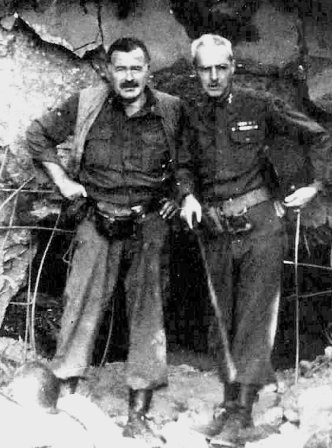

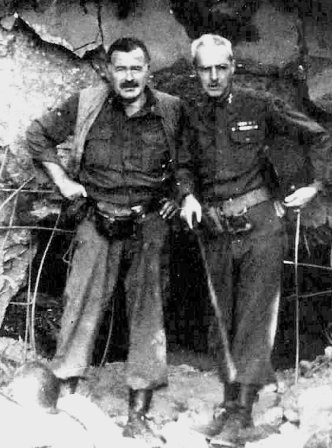

On July 8, he was seriously wounded by mortar fire, having just returned from the canteen bringing chocolate and cigarettes for the men at the front line. Despite his wounds, Hemingway assisted Italian soldiers to safety, for which he was decorated with the Italian War Merit Cross, the ''Croce al Merito di Guerra''.On awarding the medal, the Italians wrote of Hemingway: "Gravely wounded by numerous pieces of shrapnel from an enemy shell, with an admirable spirit of brotherhood, before taking care of himself, he rendered generous assistance to the Italian soldiers more seriously wounded by the same explosion and did not allow himself to be carried elsewhere until after they had been evacuated." See Mellow (1992), p. 61 He was still only 18 at the time. Hemingway later said of the incident: "When you go to war as a boy you have a great illusion of immortality. Other people get killed; not you ... Then when you are badly wounded the first time you lose that illusion and you know it can happen to you." He sustained severe shrapnel wounds to both legs, underwent an immediate operation at a distribution center, and spent five days at a field hospital before he was transferred for recuperation to the Red Cross hospital in Milan.Desnoyers, 3 He spent six months at the hospital, where he met and formed a strong friendship with "Chink" Dorman-Smith that lasted for decades and shared a room with future American

On July 8, he was seriously wounded by mortar fire, having just returned from the canteen bringing chocolate and cigarettes for the men at the front line. Despite his wounds, Hemingway assisted Italian soldiers to safety, for which he was decorated with the Italian War Merit Cross, the ''Croce al Merito di Guerra''.On awarding the medal, the Italians wrote of Hemingway: "Gravely wounded by numerous pieces of shrapnel from an enemy shell, with an admirable spirit of brotherhood, before taking care of himself, he rendered generous assistance to the Italian soldiers more seriously wounded by the same explosion and did not allow himself to be carried elsewhere until after they had been evacuated." See Mellow (1992), p. 61 He was still only 18 at the time. Hemingway later said of the incident: "When you go to war as a boy you have a great illusion of immortality. Other people get killed; not you ... Then when you are badly wounded the first time you lose that illusion and you know it can happen to you." He sustained severe shrapnel wounds to both legs, underwent an immediate operation at a distribution center, and spent five days at a field hospital before he was transferred for recuperation to the Red Cross hospital in Milan.Desnoyers, 3 He spent six months at the hospital, where he met and formed a strong friendship with "Chink" Dorman-Smith that lasted for decades and shared a room with future American foreign service officer

A Foreign Service Officer (FSO) is a commissioned member of the United States Foreign Service. Foreign Service Officers formulate and implement the foreign policy of the United States. FSOs spend most of their careers overseas as members of U ...

, ambassador, and author Henry Serrano Villard Henry Serrano Villard (March 30, 1900January 21, 1996) was an American foreign service officer, ambassador and author.

Life

Henry S. Villard was born in Manhattan, New York City March 30, 1900. He was the great-grandson of William Lloyd Garrison, ...

.

While recuperating he fell in love with Agnes von Kurowsky

Agnes Hannah von Kurowsky Stanfield (January 5, 1892 – November 25, 1984) was an American nurse who inspired the character "Catherine Barkley" in Ernest Hemingway's 1929 novel ''A Farewell to Arms''.

Kurowsky served as a nurse in an American Re ...

, a Red Cross nurse seven years his senior. When Hemingway returned to the United States in January 1919, he believed Agnes would join him within months and the two would marry. Instead, he received a letter in March with her announcement that she was engaged to an Italian officer. Biographer Jeffrey Meyers

Jeffrey Meyers (born April 1, 1939 in New York City) is an American biographer, literary, art and film critic. He currently lives in Berkeley, California.

Biography

Jeffrey Meyers was born in New York City in 1939 and grew up in New York. He wa ...

writes Agnes's rejection devastated and scarred the young man; in future relationships, Hemingway followed a pattern of abandoning a wife before she abandoned him.Meyers (1985), 37–42

Toronto and Chicago

Hemingway returned home early in 1919 to a time of readjustment. Before the age of 20, he had gained from the war a maturity that was at odds with living at home without a job and with the need for recuperation.Meyers (1985), 45–53 As Reynolds explains, "Hemingway could not really tell his parents what he thought when he saw his bloody knee." He was not able to tell them how scared he had been "in another country with surgeons who could not tell him in English if his leg was coming off or not." In September, he took a fishing and camping trip with high-school friends to the back-country of Michigan'sUpper Peninsula

The Upper Peninsula of Michigan – also known as Upper Michigan or colloquially the U.P. – is the northern and more elevated of the two major landmasses that make up the U.S. state of Michigan; it is separated from the Lower Peninsula by t ...

. The trip became the inspiration for his short story "Big Two-Hearted River

"Big Two-Hearted River" is a two-part short story written by American author Ernest Hemingway, published in the 1925 Boni & Liveright edition of ''In Our Time'', the first American volume of Hemingway's short stories. It features a single prota ...

", in which the semi-autobiographical

An autobiographical novel is a form of novel using autofiction techniques, or the merging of autobiographical and fictive elements. The literary technique is distinguished from an autobiography or memoir by the stipulation of being fiction. Bec ...

character Nick Adams takes to the country to find solitude after returning from war. A family friend offered him a job in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

, and with nothing else to do, he accepted. Late that year he began as a freelancer and staff writer for the ''Toronto Star Weekly''. He returned to Michigan the following June and then moved to Chicago in September 1920 to live with friends, while still filing stories for the ''Toronto Star

The ''Toronto Star'' is a Canadian English-language broadsheet daily newspaper. The newspaper is the country's largest daily newspaper by circulation. It is owned by Toronto Star Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary of Torstar Corporation and part ...

''. In Chicago, he worked as an associate editor of the monthly journal ''Cooperative Commonwealth'', where he met novelist Sherwood Anderson

Sherwood Anderson (September 13, 1876 – March 8, 1941) was an American novelist and short story writer, known for subjective and self-revealing works. Self-educated, he rose to become a successful copywriter and business owner in Cleveland and ...

.Meyers (1985), 56–58

When St. Louis native Hadley Richardson

Elizabeth Hadley Richardson (November 9, 1891 – January 22, 1979) was the first wife of American author Ernest Hemingway. The two married in 1921 after a courtship of less than a year, and moved to Paris within months of being married. In Paris, ...

came to Chicago to visit the sister of Hemingway's roommate, Hemingway became infatuated. He later claimed, "I knew she was the girl I was going to marry." Hadley, red-haired, with a "nurturing instinct", was eight years older than Hemingway. Despite the age difference, Hadley, who had grown up with an overprotective mother, seemed less mature than usual for a young woman her age.Oliver (1999), 139 Bernice Kert, author of ''The Hemingway Women'', claims Hadley was "evocative" of Agnes, but that Hadley had a childishness that Agnes lacked. The two corresponded for a few months and then decided to marry and travel to Europe.Kert (1983), 83–90 They wanted to visit Rome, but Sherwood Anderson convinced them to visit Paris instead, writing letters of introduction for the young couple.Baker (1972), 7 They were married on September 3, 1921; two months later Hemingway was hired as a foreign correspondent for the ''Toronto Star'', and the couple left for Paris. Of Hemingway's marriage to Hadley, Meyers claims: "With Hadley, Hemingway achieved everything he had hoped for with Agnes: the love of a beautiful woman, a comfortable income, a life in Europe."Meyers (1985), 60–62

Paris

Carlos Baker

Carlos Baker (May 5, 1909, Biddeford, Maine – April 18, 1987, Princeton, New Jersey) was an American writer, biographer and former Woodrow Wilson Professor of Literature at Princeton University. He received his B.A. from Dartmouth College and h ...

, Hemingway's first biographer, believes that while Anderson suggested Paris because "the monetary exchange rate" made it an inexpensive place to live, more importantly it was where "the most interesting people in the world" lived. In Paris, Hemingway met American writer and art collector Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the Allegheny West neighborhood and raised in Oakland, California, Stein moved to Paris ...

, Irish novelist James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

, American poet Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Fascism, fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II. His works ...

(who "could help a young writer up the rungs of a career") and other writers.

The Hemingway of the early Paris years was a "tall, handsome, muscular, broad-shouldered, brown-eyed, rosy-cheeked, square-jawed, soft-voiced young man." He and Hadley lived in a small walk-up at 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine in the Latin Quarter

The Latin Quarter of Paris (french: Quartier latin, ) is an area in the 5th and the 6th arrondissements of Paris. It is situated on the left bank of the Seine, around the Sorbonne.

Known for its student life, lively atmosphere, and bistros ...

, and he worked in a rented room in a nearby building. Stein, who was the bastion of modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

in Paris, became Hemingway's mentor and godmother to his son Jack; she introduced him to the expatriate artists and writers of the Montparnasse Quarter

Montparnasse () is an area in the south of Paris, France, on the left bank of the river Seine, centred at the crossroads of the Boulevard du Montparnasse and the Rue de Rennes, between the Rue de Rennes and boulevard Raspail. Montparnasse has be ...

, whom she referred to as the "Lost Generation

The Lost Generation was the social generational cohort in the Western world that was in early adulthood during World War I. "Lost" in this context refers to the "disoriented, wandering, directionless" spirit of many of the war's survivors in the ...

"—a term Hemingway popularized with the publication of ''The Sun Also Rises

''The Sun Also Rises'' is a 1926 novel by American writer Ernest Hemingway, his first, that portrays American and British expatriates who travel from Paris to the Festival of San Fermín in Pamplona to watch the running of the bulls and the bu ...

''.Mellow (1992), 308 A regular at Stein's salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon (P ...

, Hemingway met influential painters such as Pablo Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and Scenic design, theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th ce ...

, Joan Miró

Joan Miró i Ferrà ( , , ; 20 April 1893 – 25 December 1983) was a Catalan painter, sculptor and ceramicist born in Barcelona. A museum dedicated to his work, the Fundació Joan Miró, was established in his native city of Barcelona i ...

, and Juan Gris

José Victoriano González-Pérez (23 March 1887 – 11 May 1927), better known as Juan Gris (; ), was a Spanish painter born in Madrid who lived and worked in France for most of his active period. Closely connected to the innovative artistic ge ...

.Reynolds (2000), 28 He eventually withdrew from Stein's influence, and their relationship deteriorated into a literary quarrel that spanned decades.Meyers (1985), 77–81 While living in Paris in 1922, Hemingway befriended artist Henry Strater

Henry "Mike" Strater (1896–1987) was an American painter, and illustrator. He was a friend of Ernest Hemingway and other figures of the Lost Generation. He was known for his Portrait, portraiture, figurative, and landscape drawings and painting ...

who painted two portraits of him.

Ezra Pound met Hemingway by chance at Sylvia Beach

Sylvia may refer to:

People

*Sylvia (given name)

*Sylvia (singer), American country music and country pop singer and songwriter

*Sylvia Robinson, American singer, record producer, and record label executive

*Sylvia Vrethammar, Swedish singer credi ...

's bookshop Shakespeare and Company in 1922. The two toured Italy in 1923 and lived on the same street in 1924.Meyers (1985), 70–74 They forged a strong friendship, and in Hemingway, Pound recognized and fostered a young talent. Pound introduced Hemingway to James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

, with whom Hemingway frequently embarked on "alcoholic sprees".Meyers (1985), 82

During his first 20 months in Paris, Hemingway filed 88 stories for the ''Toronto Star'' newspaper. He covered the Greco-Turkish War, where he witnessed the burning of Smyrna

The burning of Smyrna ( el, Καταστροφή της Σμύρνης, "Smyrna Catastrophe"; tr, 1922 İzmir Yangını, "1922 Izmir Fire"; hy, Զմիւռնիոյ Մեծ Հրդեհ, ''Zmyuṙno Mets Hrdeh'') destroyed much of the port city of ...

, and wrote travel pieces such as "Tuna Fishing in Spain" and "Trout Fishing All Across Europe: Spain Has the Best, Then Germany".Desnoyers, 5

Hemingway was devastated on learning that Hadley had lost a suitcase filled with his manuscripts at the Gare de Lyon

The Gare de Lyon, officially Paris-Gare-de-Lyon, is one of the six large mainline railway stations in Paris, France. It handles about 148.1 million passengers annually according to the estimates of the SNCF in 2018, with SNCF railways and RER D ...

as she was traveling to Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

to meet him in December 1922.Meyers (1985), 69–70 In the following September the couple returned to Toronto, where their son John Hadley Nicanor was born on October 10, 1923. During their absence, Hemingway's first book, ''Three Stories and Ten Poems

''Three Stories and Ten Poems'' is a collection of short stories and poems by Ernest Hemingway. It was privately published in 1923 in a run of 300 copies by Robert McAlmon's "Contact Publishing" in Paris.Oliver, Charles. (1999). ''Ernest Hemingw ...

'', was published. Two of the stories it contained were all that remained after the loss of the suitcase, and the third had been written early the previous year in Italy. Within months a second volume, ''in our time'' (without capitals), was published. The small volume included six vignettes

Vignette may refer to:

* Vignette (entertainment), a sketch in a sketch comedy

* Vignette (graphic design), decorative designs in books (originally in the form of leaves and vines) to separate sections or chapters

* Vignette (literature), short, i ...

and a dozen stories Hemingway had written the previous summer during his first visit to Spain, where he discovered the thrill of the '' corrida''. He missed Paris, considered Toronto boring, and wanted to return to the life of a writer, rather than live the life of a journalist.Baker (1972), 15–18

Hemingway, Hadley and their son (nicknamed Bumby) returned to Paris in January 1924 and moved into a new apartment on the rue Notre-Dame des Champs. Hemingway helped Ford Madox Ford

Ford Madox Ford (né Joseph Leopold Ford Hermann Madox Hueffer ( ); 17 December 1873 – 26 June 1939) was an English novelist, poet, critic and editor whose journals ''The English Review'' and ''The Transatlantic Review'' were instrumental in ...

edit ''The Transatlantic Review

''The Transatlantic Review'' (often styled ''the transatlantic review'') was an influential monthly literary magazine edited by Ford Madox Ford in 1924. The magazine was based in Paris but was published in London by Gerald Duckworth and Company.

...

'', which published works by Pound, John Dos Passos

John Roderigo Dos Passos (; January 14, 1896 – September 28, 1970) was an American novelist, most notable for his ''U.S.A.'' trilogy.

Born in Chicago, Dos Passos graduated from Harvard College in 1916. He traveled widely as a young man, visit ...

, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

Elsa Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven (née Else Hildegard Plötz; (12 July 1874 – 14 December 1927) was a German-born avant-garde visual artist and poet, who was active in Greenwich Village, New York, from 1913 to 1923, where her radical self ...

, and Stein, as well as some of Hemingway's own early stories such as "Indian Camp

"Indian Camp" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway. The story was first published in 1924 in Ford Madox Ford's literary magazine ''Transatlantic Review'' in Paris and republished by Boni & Liveright in Hemingway's first American volume of ...

".Meyers (1985), 126 When ''In Our Time In Our Time may refer to:

* ''In Our Time'' (1944 film), a film starring Ida Lupino and Paul Henreid

* ''In Our Time'' (1982 film), a Taiwanese anthology film featuring director Edward Yang; considered the beginning of the "New Taiwan Cinema"

* ''In ...

'' was published in 1925, the dust jacket bore comments from Ford.Meyers (1985), 127 "Indian Camp" received considerable praise; Ford saw it as an important early story by a young writer, and critics in the United States praised Hemingway for reinvigorating the short story genre with his crisp style and use of declarative sentences. Six months earlier, Hemingway had met F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age—a term he popularize ...

, and the pair formed a friendship of "admiration and hostility".Meyers (1985), 159–160 Fitzgerald had published ''The Great Gatsby

''The Great Gatsby'' is a 1925 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Set in the Jazz Age on Long Island, near New York City, the novel depicts First-person narrative, first-person narrator Nick Carraway's interactions with mysterious mil ...

'' the same year: Hemingway read it, liked it, and decided his next work had to be a novel.Baker (1972), 30–34

With his wife Hadley, Hemingway first visited the Festival of San Fermín

The festival of San Fermín is a weeklong, historically rooted celebration held annually in the city of Pamplona, Navarre, in northern Spain.

The celebrations start at noon on July 6 and continue until midnight on July 14. A firework starts o ...

in Pamplona

Pamplona (; eu, Iruña or ), historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain. It is also the third-largest city in the greater Basque cultural region.

Lying at near above ...

, Spain, in 1923, where he became fascinated by bullfighting

Bullfighting is a physical contest that involves a bullfighter attempting to subdue, immobilize, or kill a bull, usually according to a set of rules, guidelines, or cultural expectations.

There are several variations, including some forms wh ...

.Meyers (1985), 117–119 It is at this time that he began to be referred to as "Papa", even by much older friends. Hadley would much later recall that Hemingway had his own nicknames for everyone and that he often did things for his friends; she suggested that he liked to be looked up to. She did not remember precisely how the nickname came into being; however, it certainly stuck. Reprinted in Published at The Hemingways returned to Pamplona in 1924 and a third time in June 1925; that year they brought with them a group of American and British expatriates: Hemingway's Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

boyhood friend Bill Smith, Donald Ogden Stewart, Lady Duff Twysden (recently divorced), her lover Pat Guthrie, and Harold Loeb

Harold Albert Loeb (October 18, 1891 – January 20, 1974) was an American writer, notable as an important American figure in the arts among expatriates in Paris in the 1920s. In 1921 he was the founding editor of ''Broom: An International Magazin ...

.Nagel (1996), 89 A few days after the fiesta ended, on his birthday (July 21), he began to write the draft of what would become ''The Sun Also Rises

''The Sun Also Rises'' is a 1926 novel by American writer Ernest Hemingway, his first, that portrays American and British expatriates who travel from Paris to the Festival of San Fermín in Pamplona to watch the running of the bulls and the bu ...

'', finishing eight weeks later.Meyers (1985), 189 A few months later, in December 1925, the Hemingways left to spend the winter in Schruns

Schruns is a municipality in the Montafon valley (altitude 690 meters), in the Bludenz district of the westernmost Austrian state of Vorarlberg.

To the west is the famous Zimba mountain, often called the "Vorarlberger Matterhorn," which is very ...

, Austria, where Hemingway began revising the manuscript extensively. Pauline Pfeiffer joined them in January and against Hadley's advice, urged Hemingway to sign a contract with Scribner's

Charles Scribner's Sons, or simply Scribner's or Scribner, is an American publisher based in New York City, known for publishing American authors including Henry James, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Kurt Vonnegut, Marjorie Kinnan Rawli ...

. He left Austria for a quick trip to New York to meet with the publishers, and on his return, during a stop in Paris, began an affair with Pfeiffer, before returning to Schruns to finish the revisions in March. The manuscript arrived in New York in April; he corrected the final proof in Paris in August 1926, and Scribner's published the novel in October.Baker (1972), 44

''The Sun Also Rises'' epitomized the post-war expatriate generation,Mellow (1992), 302 received good reviews and is "recognized as Hemingway's greatest work".Meyers (1985), 192 Hemingway himself later wrote to his editor Max Perkins

William Maxwell Evarts "Max" Perkins (September 20, 1884 – June 17, 1947) was an American book editor, best remembered for discovering authors Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and Thomas Wolfe.

Early life and e ...

that the "point of the book" was not so much about a generation being lost, but that "the earth abideth forever"; he believed the characters in ''The Sun Also Rises'' may have been "battered" but were not lost.Baker (1972), 82

Hemingway's marriage to Hadley deteriorated as he was working on ''The Sun Also Rises''. In early 1926, Hadley became aware of his affair with Pfeiffer, who came to Pamplona with them that July.Baker (1972), 43 On their return to Paris, Hadley asked for a separation; in November she formally requested a divorce. They split their possessions while Hadley accepted Hemingway's offer of the proceeds from ''The Sun Also Rises''. The couple were divorced in January 1927, and Hemingway married Pfeiffer in May.Meyers (1985), 172

Pfeiffer, who was from a wealthy

Pfeiffer, who was from a wealthy Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

family, had moved to Paris to work for ''Vogue

Vogue may refer to:

Business

* ''Vogue'' (magazine), a US fashion magazine

** British ''Vogue'', a British fashion magazine

** ''Vogue Arabia'', an Arab fashion magazine

** ''Vogue Australia'', an Australian fashion magazine

** ''Vogue China'', ...

'' magazine. Before their marriage, Hemingway converted to Catholicism. They honeymooned in Le Grau-du-Roi

Le Grau-du-Roi (; oc, Lo Grau dau Rei) is a commune in the Gard department in southern France. It is the only commune in Gard to have a frontage on the Mediterranean. To the west is the Herault department and La Grande-Motte village, and to th ...

, where he contracted anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The sk ...

, and he planned his next collection of short stories, '' Men Without Women'', which was published in October 1927,Meyers (1985), 195 and included his boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

story "Fifty Grand

"Fifty Grand" is a short story by Ernest Hemingway. It was first published in ''The Atlantic Monthly'' in 1927, and it appeared later that year in Hemingway's short story collection '' Men Without Women''.

"Fifty Grand" tells the story of Jack B ...

". ''Cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan may refer to:

Food and drink

* Cosmopolitan (cocktail), also known as a "Cosmo"

History

* Rootless cosmopolitan, a Soviet derogatory epithet during Joseph Stalin's anti-Semitic campaign of 1949–1953

Hotels and resorts

* Cosmopoli ...

'' magazine editor-in-chief Ray Long

William Ray Long, (March 23, 1878 – July 9, 1935) was an American newspaper, magazine, film, writer, and editor who is notable for being the editor-in-chief of ''Cosmopolitan'' magazine between 1919 and 1931. He is said to have had "a colorfu ...

praised "Fifty Grand", calling it, "one of the best short stories that ever came to my hands ... the best prize-fight story I ever read ... a remarkable piece of realism."

By the end of the year Pauline, who was pregnant, wanted to move back to America. John Dos Passos recommended Key West

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it cons ...

, and they left Paris in March 1928. Hemingway suffered a severe injury in their Paris bathroom when he pulled a skylight down on his head thinking he was pulling on a toilet chain. This left him with a prominent forehead scar, which he carried for the rest of his life. When Hemingway was asked about the scar, he was reluctant to answer. After his departure from Paris, Hemingway "never again lived in a big city".Meyers (1985), 204

Key West and the Caribbean

Hemingway and Pauline traveled to Kansas City, where their son

Hemingway and Pauline traveled to Kansas City, where their son Patrick Patrick may refer to:

* Patrick (given name), list of people and fictional characters with this name

* Patrick (surname), list of people with this name

People

* Saint Patrick (c. 385–c. 461), Christian saint

*Gilla Pátraic (died 1084), Patrick ...

was born on June 28, 1928. Pauline had a difficult delivery; Hemingway fictionalized a version of the event as a part of ''A Farewell to Arms

''A Farewell to Arms'' is a novel by American writer Ernest Hemingway, set during the Italian campaign of World War I. First published in 1929, it is a first-person account of an American, Frederic Henry, serving as a lieutenant () in the am ...

''. After Patrick's birth, Pauline and Hemingway traveled to Wyoming, Massachusetts, and New York.Meyers (1985), 208 In the winter, he was in New York with Bumby, about to board a train to Florida, when he received a cable telling him that his father had killed himself.Clarence Hemingway used his father's Civil War pistol to shoot himself. See Meyers (1985), 2 Hemingway was devastated, having earlier written to his father telling him not to worry about financial difficulties; the letter arrived minutes after the suicide. He realized how Hadley must have felt after her own father's suicide in 1903, and he commented, "I'll probably go the same way."

Upon his return to Key West in December, Hemingway worked on the draft of ''A Farewell to Arms'' before leaving for France in January. He had finished it in August but delayed the revision. The serialization in ''Scribner's Magazine

''Scribner's Magazine'' was an American periodical published by the publishing house of Charles Scribner's Sons from January 1887 to May 1939. ''Scribner's Magazine'' was the second magazine out of the Scribner's firm, after the publication of ' ...

'' was scheduled to begin in May, but as late as April, Hemingway was still working on the ending, which he may have rewritten as many as seventeen times. The completed novel was published on September 27.Meyers (1985), 215 Biographer James Mellow believes ''A Farewell to Arms'' established Hemingway's stature as a major American writer and displayed a level of complexity not apparent in ''The Sun Also Rises''.(The story was turned into a play by war veteran Laurence Stallings

Laurence Tucker Stallings (November 25, 1894 – February 28, 1968) was an American playwright, screenwriter, lyricist, literary critic, journalist, novelist, and photographer. Best known for his collaboration with Maxwell Anderson on the 1924 pl ...

that was the basis for the film starring Gary Cooper

Gary Cooper (born Frank James Cooper; May 7, 1901May 13, 1961) was an American actor known for his strong, quiet screen persona and understated acting style. He won the Academy Award for Best Actor twice and had a further three nominations, a ...

.)Mellow (1992), 378 In Spain in mid-1929, Hemingway researched his next work, ''Death in the Afternoon

''Death in the Afternoon'' is a non-fiction book written by Ernest Hemingway about the ceremony and traditions of Spanish bullfighting, published in 1932. The book provides a look at the history and the Spanish traditions of bullfighting. It al ...

''. He wanted to write a comprehensive treatise

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject, generally longer and treating it in greater depth than an essay, and more concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions."Treat ...

on bullfighting, explaining the ''toreros'' and ''corridas'' complete with glossaries and appendices, because he believed bullfighting was "of great tragic interest, being literally of life and death."

During the early 1930s, Hemingway spent his winters in Key West and summers in Wyoming, where he found "the most beautiful country he had seen in the American West" and hunted deer, elk, and grizzly bear.Meyers (1985), 222 He was joined there by Dos Passos, and in November 1930, after bringing Dos Passos to the train station in Billings, Montana

Billings is the largest city in the U.S. state of Montana, with a population of 117,116 as of the 2020 census. Located in the south-central portion of the state, it is the seat of Yellowstone County and the principal city of the Billings Metrop ...

, Hemingway broke his arm in a car accident. The surgeon tended the compound spiral fracture and bound the bone with kangaroo tendon. Hemingway was hospitalized for seven weeks, with Pauline tending to him; the nerves in his writing hand took as long as a year to heal, during which time he suffered intense pain.

His third child,

His third child, Gloria Hemingway

Gloria Hemingway (born Gregory Hancock Hemingway, November 12, 1931 – October 1, 2001) was an American physician and writer who was the third and youngest child of author Ernest Hemingway.

A good athlete and a crack shot, Gloria longed to ...

, was born a year later on November 12, 1931, in Kansas City as "Gregory Hancock Hemingway".Oliver (1999), 144She would undergo sex reassignment surgery

Gender-affirming surgery (GAS) is a surgical procedure, or series of procedures, that alters a transgender or transsexual person's physical appearance and sexual characteristics to resemble those associated with their identified gender, and alle ...

in the mid-1990s and took the name Gloria Hemingway. Se"Hemingway legacy feud 'resolved'"

. BBC News. October 3, 2003. Retrieved April 26, 2011. Pauline's uncle bought the couple a

house

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

in Key West with a carriage house, the second floor of which was converted into a writing studio.Meyers (1985), 222–227 While in Key West, Hemingway frequented the local bar Sloppy Joe's

Sloppy Joe's Bar is a historic American bar in Key West, Florida located at the corner of Duval and Greene street since 1937.

Description

Sloppy Joe's was purchased September 8, 1978 by Sid Snelgrove and Jim Mayer and has been owned by the tw ...

.Mellow (1992), 402 He invited friends—including Waldo Peirce

Waldo Peirce (December 17, 1884 – March 8, 1970) was an American painter, who for many years reveled in living the life of a bohemian expatriate.

Peirce was both a prominent painter and a well-known colorful figure in the world of the arts ...

, Dos Passos, and Max Perkins

William Maxwell Evarts "Max" Perkins (September 20, 1884 – June 17, 1947) was an American book editor, best remembered for discovering authors Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and Thomas Wolfe.

Early life and e ...

—to join him on fishing trips and on an all-male expedition to the Dry Tortugas

Dry Tortugas National Park is a national park located about west of Key West in the Gulf of Mexico. The park preserves Fort Jefferson and the seven Dry Tortugas islands, the westernmost and most isolated of the Florida Keys. The archipelago's c ...

. Meanwhile, he continued to travel to Europe and to Cuba, and—although in 1933 he wrote of Key West, "We have a fine house here, and kids are all well"—Mellow believes he "was plainly restless".Mellow (1992), 424

In 1933, Hemingway and Pauline went on safari to Kenya. The 10-week trip provided material for ''Green Hills of Africa

''Green Hills of Africa'' is a 1935 work of nonfiction by American writer Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway's second work of nonfiction, ''Green Hills of Africa'' is an account of a month on safari he and his wife, Pauline Marie Pfeiffer, took in East ...

'', as well as for the short stories " The Snows of Kilimanjaro" and "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber

"The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber" is a short story by Ernest Hemingway. Set in Africa, it was published in the September 1936 issue of ''Cosmopolitan'' magazine concurrently with " The Snows of Kilimanjaro". The story was eventually adap ...

".Desnoyers, 9 The couple visited Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of the British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital city status. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

, Nairobi

Nairobi ( ) is the capital and largest city of Kenya. The name is derived from the Maasai phrase ''Enkare Nairobi'', which translates to "place of cool waters", a reference to the Nairobi River which flows through the city. The city proper ha ...

, and Machakos

Machakos, also called Masaku is a town in Kenya, southeast of Nairobi. It is the capital of the Machakos County, Kenya. Its population is rapidly growing and was 150,041 as of 2009 and Machakos County had a population of 1,421,932 as of 2019 ...

in Kenya; then moved on to Tanganyika Territory

Tanganyika was a colonial territory in East Africa which was administered by the United Kingdom in various guises from 1916 to 1961. It was initially administered under a military occupation regime. From 20 July 1922, it was formalised into a L ...

, where they hunted in the Serengeti

The Serengeti ( ) ecosystem is a geographical region in Africa, spanning northern Tanzania. The protected area within the region includes approximately of land, including the Serengeti National Park and several game reserves. The Serengeti ...

, around Lake Manyara

Lake Manyara is a lake located in Monduli District of Arusha Region, Tanzania and is the seventh-largest lake of Tanzania by surface area, at . It is a shallow, alkaline lake in the Natron-Manyara-Balangida branch of the East African Rift. The n ...

, and west and southeast of present-day Tarangire National Park

Tarangire National Park is a national park in Tanzania's Manyara Region. The name of the park originates from the Tarangire River that crosses the park. The Tarangire River is the primary source of fresh water for wild animals in the Tarangire E ...

. Their guide was the noted "white hunter" Philip Percival who had guided Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

on his 1909 safari. During these travels, Hemingway contracted amoebic dysentery

Amoebiasis, or amoebic dysentery, is an infection of the intestines caused by a parasitic amoeba ''Entamoeba histolytica''. Amoebiasis can be present with no, mild, or severe symptoms. Symptoms may include lethargy, loss of weight, colonic ulc ...

that caused a prolapsed intestine, and he was evacuated by plane to Nairobi, an experience reflected in "The Snows of Kilimanjaro". On Hemingway's return to Key West in early 1934, he began work on ''Green Hills of Africa'', which he published in 1935 to mixed reviews.

Hemingway bought a boat in 1934, named it the '' Pilar'', and began sailing the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

.Meyers (1985), 280 In 1935 he first arrived at Bimini

Bimini is the westernmost district of the Bahamas and comprises a chain of islands located about due east of Miami. Bimini is the closest point in the Bahamas to the mainland United States and approximately west-northwest of Nassau. The populat ...

, where he spent a considerable amount of time. During this period he also worked on ''To Have and Have Not

''To Have and Have Not'' is a novel by Ernest Hemingway published in 1937 by Charles Scribner's Sons. The book follows Harry Morgan, a fishing boat captain out of Key West, Florida. ''To Have and Have Not'' was Hemingway's second novel set in th ...

'', published in 1937 while he was in Spain, the only novel he wrote during the 1930s.Meyers (1985), 292

Spanish Civil War

In 1937, Hemingway left for Spain to cover the

In 1937, Hemingway left for Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

for the North American Newspaper Alliance

The North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA) was a large newspaper syndicate that flourished between 1922 and 1980. NANA employed some of the most noted writing talents of its time, including Grantland Rice, Joseph Alsop, Michael Stern, Lothrop S ...

(NANA), despite Pauline's reluctance to have him working in a war zone.Mellow (1992), 488 He and Dos Passos both signed on to work with Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens

Georg Henri Anton "Joris" Ivens (18 November 1898 – 28 June 1989) was a Dutch documentary filmmaker. Among the notable films he directed or co-directed are '' A Tale of the Wind'', '' The Spanish Earth'', ''Rain'', ''...A Valparaiso'', ''M ...

as screenwriters for ''The Spanish Earth

''The Spanish Earth'' is a 1937 anti-fascist film made during the Spanish Civil War in support of the democratically elected Republicans, whose forces included a wide range from the political left like communists, socialists, anarchists, to moder ...

''.Meyers (1985), 311 Dos Passos left the project after the execution of José Robles

José Robles Pazos (Santiago de Compostela, 1897–1937) was a Spanish writer, academic and independent left-wing activist. Born to an aristocratic family, Robles embraced left-wing views which forced him to leave Spain and go into exile in th ...

, his friend and Spanish translator,Meyers (1985), 308–311 which caused a rift between the two writers.Koch (2005), 164

Hemingway was joined in Spain by journalist and writer Martha Gellhorn, whom he had met in Key West a year earlier. Like Hadley, Martha was a St. Louis native, and like Pauline, she had worked for ''Vogue'' in Paris. Of Martha, Kert explains, "she never catered to him the way other women did".Kert (1983), 287–295 In July 1937 he attended the Second International Writers' Congress, the purpose of which was to discuss the attitude of intellectuals to the war, held in Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, Valencia and the Municipalities of Spain, third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is ...

, Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

and Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

and attended by many writers including André Malraux

Georges André Malraux ( , ; 3 November 1901 – 23 November 1976) was a French novelist, art theorist, and minister of cultural affairs. Malraux's novel ''La Condition Humaine'' (Man's Fate) (1933) won the Prix Goncourt. He was appointed by P ...

, Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry by the ...

and Pablo Neruda

Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto (12 July 1904 – 23 September 1973), better known by his pen name and, later, legal name Pablo Neruda (; ), was a Chilean poet-diplomat and politician who won the 1971 Nobel Prize in Literature. Nerud ...

. Late in 1937, while in Madrid with Martha, Hemingway wrote his only play, '' The Fifth Column'', as the city was being bombarded by Francoist forces.Koch (2005), 134 He returned to Key West for a few months, then back to Spain twice in 1938, where he was present at the Battle of the Ebro

The Battle of the Ebro ( es, Batalla del Ebro, ca, Batalla de l'Ebre) was the longest and largest battle of the Spanish Civil War and the greatest, in terms of manpower, logistics and material ever fought on Spanish soil. It took place between Ju ...

, the last republican stand, and he was among the British and American journalists who were some of the last to leave the battle as they crossed the river.Meyers (1985), 321Thomas (2001), 833

Cuba

In early 1939, Hemingway crossed to Cuba in his boat to live in theHotel Ambos Mundos

The Hotel Ambos Mundos (, '' Both Worlds Hotel'') is a hotel in Havana, Cuba. Built with a square form with five floors, it has an eclectic set of characteristics of 20th-century style architecture. It was built in 1924 on a site that previousl ...

in Havana. This was the separation phase of a slow and painful split from Pauline, which began when Hemingway met Martha Gellhorn.Meyers (1985), 326 Martha soon joined him in Cuba, and they rented "Finca Vigía

Finca Vigía (, ''Lookout Farm'') is a house in San Francisco de Paula Ward in Havana, Cuba which was once the residence of Ernest Hemingway. Like Hemingway's Key West home, it is now a museum. The building was constructed in 1886.

History of ...

" ("Lookout Farm"), a property from Havana. Pauline and the children left Hemingway that summer, after the family was reunited during a visit to Wyoming; when his divorce from Pauline was finalized, he and Martha were married on November 20, 1940, in Cheyenne, Wyoming

Cheyenne ( or ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Wyoming, as well as the county seat of Laramie County, with 65,132 residents, per the 2020 US Census. It is the principal city of the Cheyenne metropolitan statistical ...

.

Hemingway moved his primary summer residence to Ketchum, Idaho

Ketchum is a city in Blaine County, Idaho, located in the central part of the state. The population was 3,555 at the 2020 census, up from 2,689 in 2010. Located in the Wood River Valley, Ketchum is adjacent to Sun Valley and the communities sh ...

, just outside the newly built resort of Sun Valley, and moved his winter residence to Cuba.Meyers (1985), 342 He had been disgusted when a Parisian friend allowed his cats to eat from the table, but he became enamored of cats in Cuba and kept dozens of them on the property.Meyers (1985), 353 Descendants of his cats live at his Key West

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it cons ...

home.

Gellhorn inspired him to write his most famous novel, ''For Whom the Bell Tolls'', which he began in March 1939 and finished in July 1940. It was published in October 1940.Meyers (1985), 334 His pattern was to move around while working on a manuscript, and he wrote ''For Whom the Bell Tolls'' in Cuba, Wyoming, and Sun Valley. It became a Book-of-the-Month Club choice, sold half a million copies within months, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and, in the words of Meyers, "triumphantly re-established Hemingway's literary reputation".Meyers (1985), 334–338

In January 1941, Martha was sent to China on assignment for ''Collier's

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened in 1905 to ''Collie ...

'' magazine. Hemingway went with her, sending in dispatches for the newspaper '' PM'', but in general he disliked China.Meyers (1985), 356–361 A 2009 book suggests during that period he may have been recruited to work for Soviet intelligence agents under the name "Agent Argo". They returned to Cuba before the declaration of war by the United States

A declaration of war is a formal declaration issued by a national government indicating that a state of war exists between that nation and another. A document by the Federation of American Scientists gives an extensive listing and summary of st ...

that December, when he convinced the Cuban government to help him refit the ''Pilar'', which he intended to use to ambush German submarines off the coast of Cuba.

World War II

Hemingway was in Europe from May 1944 to March 1945. When he arrived in London, he met ''

Hemingway was in Europe from May 1944 to March 1945. When he arrived in London, he met ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' magazine correspondent Mary Welsh

Air Chief Commandant Dame Ruth Mary Eldridge Welsh, (née Dalzell; 2 August 1896 – 25 June 1986), known as Mary Welsh, was second Director of the British Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), from 1943 to 1946.

Early life