Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the

astronomical

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, galaxies ...

model in which the

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

and planets revolve around the

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

at the center of the

universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. Acc ...

. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to

geocentrism

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, and ...

, which placed the Earth at the center. The notion that the Earth revolves around the Sun had been proposed as early as the third century BC by

Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos (; grc-gre, Ἀρίσταρχος ὁ Σάμιος, ''Aristarkhos ho Samios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or ...

, who had been influenced by a concept presented by

Philolaus of Croton

Philolaus (; grc, Φιλόλαος, ''Philólaos''; ) was a Greek Pythagorean and pre-Socratic philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pytha ...

(c. 470 – 385 BC). In the 5th century BC the Greek Philosophers

Philolaus

Philolaus (; grc, Φιλόλαος, ''Philólaos''; ) was a Greek Pythagorean and pre-Socratic philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pytha ...

and

Hicetas

Hicetas ( grc, Ἱκέτας or ; c. 400 – c. 335 BC) was a Greek philosopher of the Pythagorean School. He was born in Syracuse. Like his fellow Pythagorean Ecphantus and the Academic Heraclides Ponticus, he believed that the daily moveme ...

had the thought on different occasions that our Earth was spherical and revolving around a "mystical" central fire, and that this fire regulated the universe. In medieval Europe, however, Aristarchus' heliocentrism attracted little attention—possibly because of the loss of scientific works of the

Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 3 ...

.

It was not until the sixteenth century that a

mathematical model

A mathematical model is a description of a system using mathematical concepts and language. The process of developing a mathematical model is termed mathematical modeling. Mathematical models are used in the natural sciences (such as physics, ...

of a heliocentric system was

presented by the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

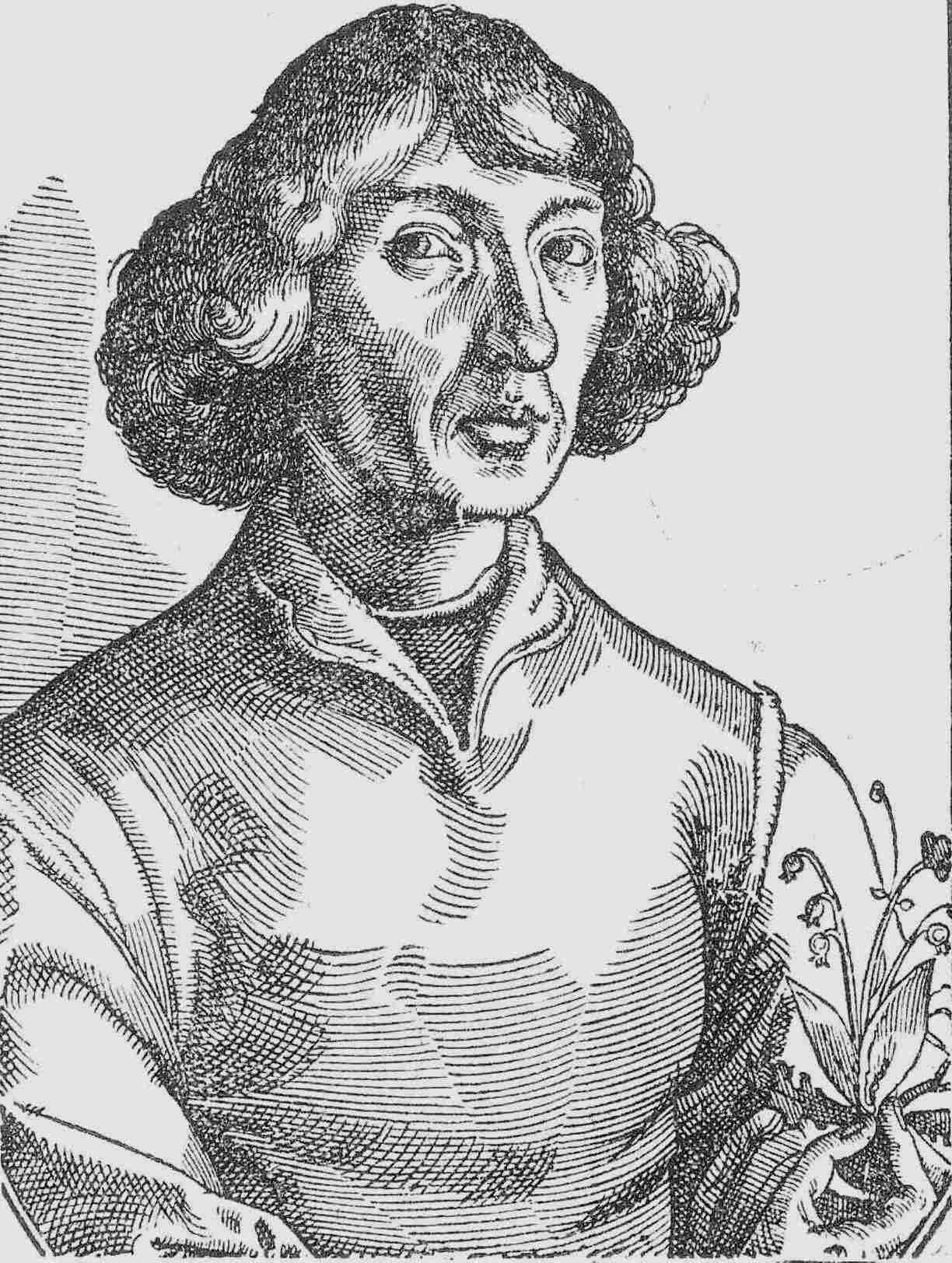

mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic cleric,

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic Church, Catholic cano ...

, leading to the

Copernican Revolution

The Copernican Revolution was the paradigm shift from the Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which described the cosmos as having Earth stationary at the center of the universe, to the heliocentric model with the Sun at the center of the Solar Sys ...

. In the following century,

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

introduced

elliptical orbits, and

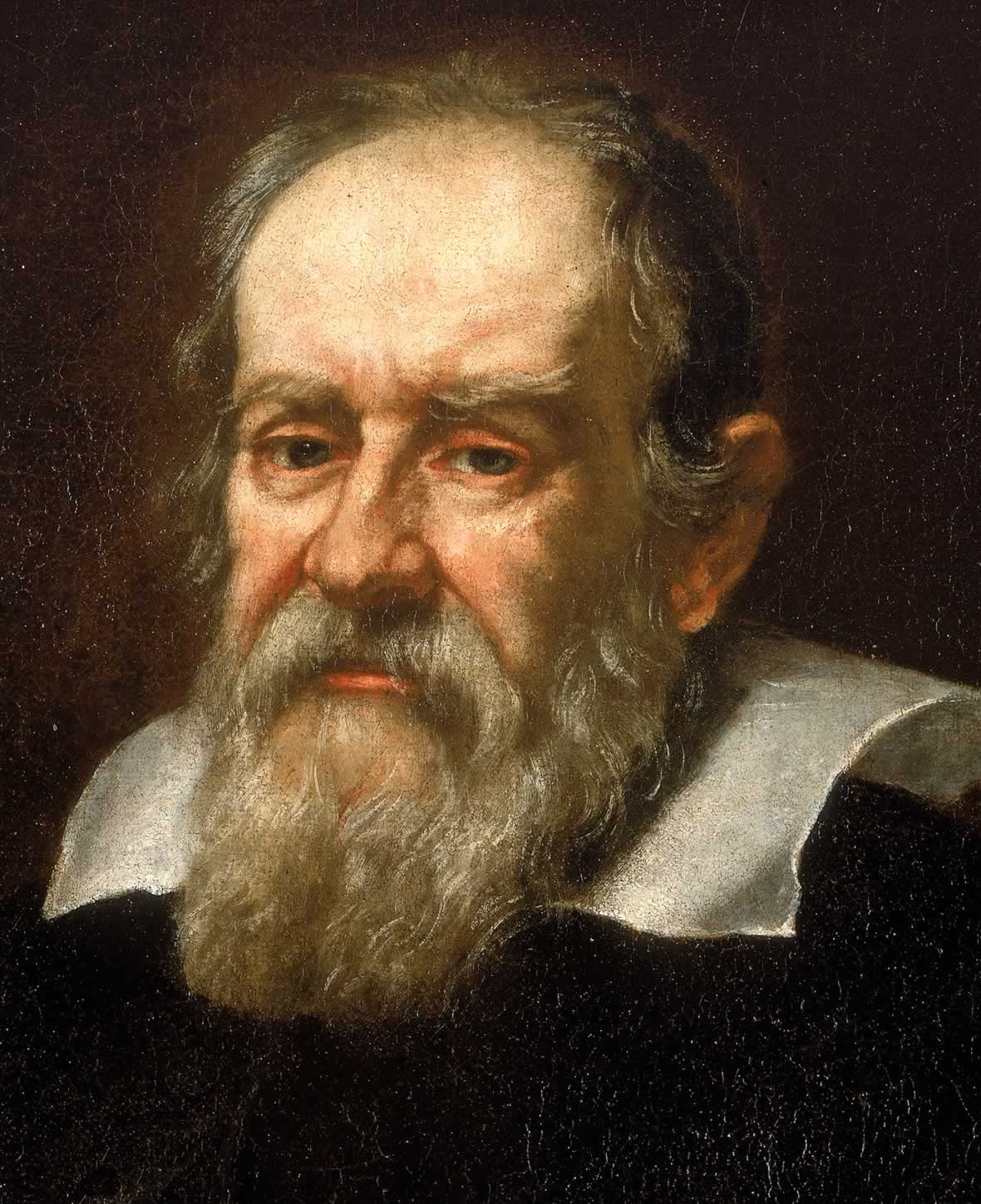

Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

presented supporting observations made using a

telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observe ...

.

With the observations of

William Herschel

Frederick William Herschel (; german: Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel; 15 November 1738 – 25 August 1822) was a German-born British astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline H ...

,

Friedrich Bessel

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (; 22 July 1784 – 17 March 1846) was a German astronomer, mathematician, physicist, and geodesist. He was the first astronomer who determined reliable values for the distance from the sun to another star by the method ...

, and other astronomers, it was realized that the Sun, while near the

barycenter

In astronomy, the barycenter (or barycentre; ) is the center of mass of two or more bodies that orbit one another and is the point about which the bodies orbit. A barycenter is a dynamical point, not a physical object. It is an important conc ...

of the

Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar S ...

, was not at any center of the universe.

Ancient and medieval astronomy

While the

sphericity of the Earth

Spherical Earth or Earth's curvature refers to the approximation of figure of the Earth as a sphere.

The earliest documented mention of the concept dates from around the 5th century BC, when it appears in the writings of Greek philosophers. I ...

was widely recognized in Greco-Roman astronomy from at least the 4th century BC, the Earth's

daily rotation and

yearly orbit around the Sun was never universally accepted until the

Copernican Revolution

The Copernican Revolution was the paradigm shift from the Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which described the cosmos as having Earth stationary at the center of the universe, to the heliocentric model with the Sun at the center of the Solar Sys ...

.

While a moving Earth was proposed at least from the 4th century BC in

Pythagoreanism

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek col ...

, and a fully developed heliocentric model was developed by

Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos (; grc-gre, Ἀρίσταρχος ὁ Σάμιος, ''Aristarkhos ho Samios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or ...

in the 3rd century BC, these ideas were not successful in replacing the view of a static spherical Earth, and from the 2nd century AD the predominant model, which would be inherited by medieval astronomy, was the

geocentric model

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

described in

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

's ''

Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it canoni ...

''.

The Ptolemaic system was a sophisticated astronomical system that managed to calculate the positions for the planets to a fair degree of accuracy.

Ptolemy himself, in his ''Almagest'', says that any model for describing the motions of the planets is merely a mathematical device, and since there is no actual way to know which is true, the simplest model that gets the right numbers should be used.

However, he rejected the idea of a

spinning Earth as absurd as he believed it would create huge winds. Within his

model

A model is an informative representation of an object, person or system. The term originally denoted the Plan_(drawing), plans of a building in late 16th-century English, and derived via French and Italian ultimately from Latin ''modulus'', a mea ...

the distances of the Moon, Sun, planets and stars could be determined by treating orbits'

celestial spheres

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmology, cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus of Cnidus, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the diurnal m ...

as contiguous realities, which gave the stars' distance as less than 20

Astronomical Units

The astronomical unit (symbol: au, or or AU) is a unit of length, roughly the distance from Earth to the Sun and approximately equal to or 8.3 light-minutes. The actual distance from Earth to the Sun varies by about 3% as Earth orbits t ...

, a regression, since

Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos (; grc-gre, Ἀρίσταρχος ὁ Σάμιος, ''Aristarkhos ho Samios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or ...

's heliocentric scheme had centuries earlier

necessarily placed the stars at least two orders of magnitude more distant.

Problems with Ptolemy's system were well recognized in medieval astronomy, and an increasing effort to criticize and improve it in the late medieval period eventually led to the

Copernican heliocentrism

Copernican heliocentrism is the astronomical model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus and published in 1543. This model positioned the Sun at the center of the Universe, motionless, with Earth and the other planets orbiting around it in circular pa ...

developed in Renaissance astronomy.

Classical antiquity

Pythagoreans

The non-geocentric model of the

universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. Acc ...

was proposed by the

Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

philosopher

Philolaus

Philolaus (; grc, Φιλόλαος, ''Philólaos''; ) was a Greek Pythagorean and pre-Socratic philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pytha ...

(d. 390 BC), who taught that at the center of the universe was a "central fire", around which the

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

,

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

,

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

and

planets

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a young ...

revolved in uniform circular motion. This system postulated the existence of a counter-earth collinear with the Earth and central fire, with the same period of revolution around the central fire as the Earth. The Sun revolved around the central fire once a year, and the stars were stationary. The Earth maintained the same hidden face towards the central fire, rendering both it and the "counter-earth" invisible from Earth. The Pythagorean concept of uniform circular motion remained unchallenged for approximately the next 2000 years, and it was to the Pythagoreans that Copernicus referred to show that the notion of a moving Earth was neither new nor revolutionary. Kepler gave an alternative explanation of the Pythagoreans' "central fire" as the Sun, "as most sects purposely hid

their teachings".

Heraclides of Pontus

Heraclides Ponticus ( grc-gre, Ἡρακλείδης ὁ Ποντικός ''Herakleides''; c. 390 BC – c. 310 BC) was a Greek philosopher and astronomer who was born in Heraclea Pontica, now Karadeniz Ereğli, Turkey, and migrated to Athens. He ...

(4th century BC) said that the

rotation of the Earth

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own axis, as well as changes in the orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in prograde motion. As viewed from the northern polar star Pola ...

explained the apparent daily motion of the celestial sphere. It used to be thought that he believed

Mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

and

Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never fa ...

to revolve around the Sun, which in turn (along with the other planets) revolves around the Earth.

Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius

Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius, usually referred to as Macrobius (fl. AD 400), was a Roman provincial who lived during the early fifth century, during late antiquity, the period of time corresponding to the Later Roman Empire, and when Latin was ...

(AD 395–423) later described this as the "Egyptian System," stating that "it did not escape the skill of the

Egyptians

Egyptians ( arz, المَصرِيُون, translit=al-Maṣriyyūn, ; arz, المَصرِيِين, translit=al-Maṣriyyīn, ; cop, ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ, remenkhēmi) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian ...

," though there is no other evidence it was known in

ancient Egypt.

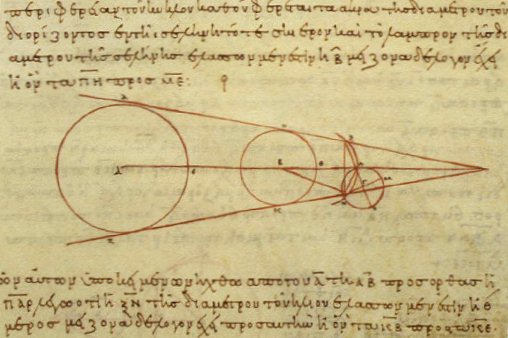

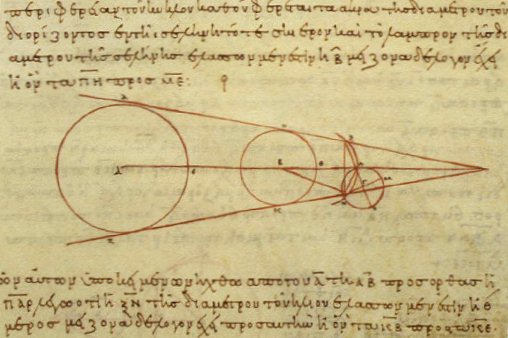

Aristarchus of Samos

The first person known to have proposed a heliocentric system was

Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos (; grc-gre, Ἀρίσταρχος ὁ Σάμιος, ''Aristarkhos ho Samios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or ...

. Like his contemporary

Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexandria ...

, Aristarchus calculated the size of the Earth and measured the

sizes and distances of the Sun and Moon. From his estimates, he concluded that the Sun was six to seven times wider than the Earth, and thought that the larger object would have the most attractive force.

His writings on the heliocentric system are lost, but some information about them is known from a brief description by his contemporary,

Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientists ...

, and from scattered references by later writers. Archimedes' description of Aristarchus' theory is given in the former's book, ''

The Sand Reckoner

''The Sand Reckoner'' ( el, Ψαμμίτης, ''Psammites'') is a work by Archimedes, an Ancient Greek mathematician of the 3rd century BC, in which he set out to determine an upper bound for the number of grains of sand that fit into the unive ...

''. The entire description comprises just three sentences, which

Thomas Heath translates as follows:

[. The italics and parenthetical comments are as they appear in Heath's original.]

Aristarchus presumably took the stars to be very far away because he was aware that their

parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. Due to foreshortening, nearby objects ...

would otherwise be observed over the course of a year. The stars are in fact so far away that stellar parallax only became detectable when sufficiently powerful

telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observe ...

s had been developed in the

1830s

The 1830s (pronounced "eighteen-thirties") was a decade of the Gregorian calendar that began on January 1, 1830, and ended on December 31, 1839.

In this decade, the world saw a rapid rise of imperialism and colonialism, particularly in Asia an ...

.

No references to Aristarchus' heliocentrism are known in any other writings from before the

common era

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

. The earliest of the handful of other ancient references occur in two passages from the writings of

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

. These mention one detail not stated explicitly in Archimedes' account—namely, that Aristarchus' theory had the Earth rotating on an axis. The first of these reference occurs in ''On the Face in the Orb of the Moon'':

Only scattered fragments of Cleanthes' writings have survived in quotations by other writers, but in ''

Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal sourc ...

'',

Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Ancient Greece, Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a ...

lists ''A reply to Aristarchus'' (Πρὸς Ἀρίσταρχον) as one of Cleanthes' works, and some scholars have suggested that this might have been where Cleanthes had accused Aristarchus of impiety.

The second of the references by Plutarch is in his ''Platonic Questions'':

The remaining references to Aristarchus' heliocentrism are extremely brief, and provide no more information beyond what can be gleaned from those already cited. Ones which mention Aristarchus explicitly by name occur in

Aëtius' ''Opinions of the Philosophers'',

Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus ( grc-gre, Σέξτος Ἐμπειρικός, ; ) was a Ancient Greece, Greek Pyrrhonism, Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and ...

' ''Against the Mathematicians'', and an anonymous scholiast to Aristotle. Another passage in Aëtius' ''Opinions of the Philosophers'' reports that Seleucus the astronomer had affirmed the Earth's motion, but does not mention Aristarchus.

Seleucus of Seleucia

Since

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

mentions the "followers of Aristarchus" in passing, it is likely that there were other astronomers in the Classical period who also espoused heliocentrism, but whose work was lost. The only other astronomer from antiquity known by name who is known to have supported Aristarchus' heliocentric model was Seleucus of Seleucia (b. 190 BC), a

Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

astronomer who flourished a century after Aristarchus in the

Seleucid empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

. Seleucus was a proponent of the heliocentric system of Aristarchus. Seleucus may have proved the heliocentric theory by determining the constants of a

geometric

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is ca ...

model for the heliocentric theory and developing methods to compute planetary positions using this model. He may have used early

trigonometric

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics that studies relationships between side lengths and angles of triangles. The field emerged in the Hellenistic world during the 3rd century BC from applications of geometry to astronomical studies. ...

methods that were available in his time, as he was a contemporary of

Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equi ...

. A fragment of a work by Seleucus has survived in Arabic translation, which was referred to by

Rhazes

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (full name: ar, أبو بکر محمد بن زکریاء الرازي, translit=Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī, label=none), () rather than ar, زکریاء, label=none (), as for example in , or in . In m ...

(b. 865).

Alternatively, his explanation may have involved the phenomenon of

tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravity, gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide t ...

s, which he supposedly theorized to be caused by the attraction to the Moon and by the revolution of the Earth around the Earth and Moon's

center of mass

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force may ...

.

Late Antiquity

There were occasional speculations about heliocentrism in Europe before Copernicus. In

Roman Carthage

After the destruction of Punic Carthage in 146 BC, a new city of Carthage (Latin '' Carthāgō'') was built on the same land in the mid-1st century BC. By the 3rd century, Carthage had developed into one of the largest cities of the Roman Empir ...

, the

pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

Martianus Capella

Martianus Minneus Felix Capella (fl. c. 410–420) was a jurist, polymath and Latin prose writer of late antiquity, one of the earliest developers of the system of the seven liberal arts that structured early medieval education. He was a nati ...

(5th century A.D.) expressed the opinion that the planets Venus and Mercury did not go about the Earth but instead circled the Sun. Capella's model was discussed in the

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

by various anonymous 9th-century commentators and Copernicus mentions him as an influence on his own work.

Ancient India

The Tamil classical literary work ''

Ciṟupāṇāṟṟuppaṭai

''Ciṟupāṇāṟṟuppaṭai'' ( ta, சிறுபாணாற்றுப்படை, ''lit.'' "guide for bards with the small lute") is an ancient Tamil poem, likely the last composed in the ''Pattuppattu'' anthology of the Sangam literat ...

'' from c. 3rd century CE by Nattattaṉār uses "the sun being orbited by planets" as an analogy for food served by a king in golden plates surrounded by sides.

The Ptolemaic system was also received in

Indian astronomy

Astronomy has long history in Indian subcontinent stretching from pre-historic to modern times. Some of the earliest roots of Indian astronomy can be dated to the period of Indus Valley civilisation or earlier. Astronomy later developed as a dis ...

.

Aryabhata

Aryabhata (ISO: ) or Aryabhata I (476–550 CE) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer of the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy. He flourished in the Gupta Era and produced works such as the ''Aryabhatiya'' (which ...

(476–550), in his magnum opus ''

Aryabhatiya

''Aryabhatiya'' (IAST: ') or ''Aryabhatiyam'' ('), a Sanskrit astronomical treatise, is the ''magnum opus'' and only known surviving work of the 5th century Indian mathematician Aryabhata. Philosopher of astronomy Roger Billard estimates that th ...

'' (499), propounded a planetary model in which the Earth was taken to be

spinning on its axis and the periods of the planets were given with respect to the Sun. His immediate commentators, such as Lalla, and other later authors, rejected his innovative view about the turning Earth. He also made many astronomical calculations, such as the times of the

solar and

lunar

Lunar most commonly means "of or relating to the Moon".

Lunar may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Lunar'' (series), a series of video games

* "Lunar" (song), by David Guetta

* "Lunar", a song by Priestess from the 2009 album ''Prior t ...

eclipse

An eclipse is an astronomical event that occurs when an astronomical object or spacecraft is temporarily obscured, by passing into the shadow of another body or by having another body pass between it and the viewer. This alignment of three ce ...

s, and the instantaneous motion of the Moon. Early followers of Aryabhata's model included

Varahamihira,

Brahmagupta

Brahmagupta ( – ) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer. He is the author of two early works on mathematics and astronomy: the ''Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta'' (BSS, "correctly established doctrine of Brahma", dated 628), a theoretical trea ...

, and

Bhaskara II.

The

Aitareya Brahmana The Aitareya Brahmana ( sa, ऐतरेय ब्राह्मण) is the Brahmana of the Shakala Shakha of the Rigveda, an ancient Indian collection of sacred hymns. This work, according to the tradition, is ascribed to Mahidasa Aitareya.

Auth ...

(dated to 500 BCE or older) states that "The sun does never set nor rise. When people think the sun is setting (it is not so)."

Medieval Islamic world

For a time,

Muslim astronomers

Islamic astronomy comprises the Astronomy, astronomical developments made in the Islamic world, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age (9th–13th centuries), and mostly written in the Arabic language. These developments mostly took place in ...

accepted the

Ptolemaic system

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, and ...

and the geocentric model, which were used by to show that the distance between the Sun and the Earth varies. In the 10th century, accepted that the

Earth rotates around its axis.

According to later astronomer

al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

, al-Sijzi invented an

astrolabe

An astrolabe ( grc, ἀστρολάβος ; ar, ٱلأَسْطُرلاب ; persian, ستارهیاب ) is an ancient astronomical instrument that was a handheld model of the universe. Its various functions also make it an elaborate inclin ...

called ''al-zūraqī'' based on a belief held by some of his contemporaries that the apparent motion of the stars was due to the Earth's movement, and not that of the firmament.

Islamic astronomers began to criticize the Ptolemaic model, including

Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the prin ...

in his '' 'alā Baṭalamiyūs'' ("Doubts Concerning Ptolemy", c. 1028), who branded it an impossibility.

Al-Biruni discussed the possibility of whether the Earth rotated about its own axis and orbited the Sun, but in his ''Masudic Canon'' (1031),

he expressed his faith in a geocentric and stationary Earth. He was aware that if the Earth rotated on its axis, it would be consistent with his astronomical observations, but considered it a problem of

natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior throu ...

rather than one of mathematics.

In the 12th century, non-heliocentric alternatives to the Ptolemaic system were developed by some Islamic astronomers, such as

Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji

Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji () (also spelled Nur al-Din Ibn Ishaq al-Betrugi and Abu Ishâk ibn al-Bitrogi) (known in the West by the Latinized name of Alpetragius) (died c. 1204) was an Iberian-Arab astronomer and a Qadi in al-Andalus. Al-Biṭrūjī ...

, who considered the Ptolemaic model mathematical, and not physical.

His system spread throughout most of Europe in the 13th century, with debates and refutations of his ideas continued to the 16th century.

The

Maragha

Maragheh ( fa, مراغه, Marāgheh or ''Marāgha''; az, ماراغا ) is a city and capital of Maragheh County, East Azerbaijan Province, Iran. Maragheh is on the bank of the river Sufi Chay. The population consists mostly of Iranian Azerb ...

school of astronomy in

Ilkhanid

The Ilkhanate, also spelled Il-khanate ( fa, ایل خانان, ''Ilxānān''), known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (, ''Qulug-un Ulus''), was a khanate established from the southwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanid realm ...

-era Persia further developed "non-Ptolemaic" planetary models involving

Earth's rotation

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own Rotation around a fixed axis, axis, as well as changes in the orientation (geometry), orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in retrograd ...

. Notable astronomers of this school are

Al-Urdi

Al-Urdi (full name: Moayad Al-Din Al-Urdi Al-Amiri Al-Dimashqi) () (d. 1266) was a medieval Syrian Arab astronomer and geometer.

Born circa 1200, presumably (from the nisba ''al‐ʿUrḍī'') in the village of ''ʿUrḍ'' in the Syrian desert b ...

(d. 1266)

Al-Katibi (d. 1277), and

Al-Tusi Al-Tusi or Tusi is the title of several Iranian scholars who were born in the town of Tous in Khorasan. Some of the scholars with the al-Tusi title include:

* Abu Nasr as-Sarraj al-Tūsī (d. 988), Sufi sheikh and historian.

*Aḥmad al Ṭūsī ( ...

(d. 1274).

The arguments and evidence used resemble those used by Copernicus to support the Earth's motion.

The criticism of Ptolemy as developed by Averroes and by the Maragha school explicitly address the

Earth's rotation

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own Rotation around a fixed axis, axis, as well as changes in the orientation (geometry), orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in retrograd ...

but it did not arrive at explicit heliocentrism.

The observations of the Maragha school were further improved at the Timurid-era

Samarkand observatory under

Qushji (1403–1474).

Later medieval period

European scholarship in the later medieval period actively received astronomical models developed in the Islamic world and by the 13th century was well aware of the problems of the Ptolemaic model. In the 14th century, bishop

Nicole Oresme

Nicole Oresme (; c. 1320–1325 – 11 July 1382), also known as Nicolas Oresme, Nicholas Oresme, or Nicolas d'Oresme, was a French philosopher of the later Middle Ages. He wrote influential works on economics, mathematics, physics, astrology an ...

discussed the possibility that the Earth rotated on its axis, while Cardinal

Nicholas of Cusa

Nicholas of Cusa (1401 – 11 August 1464), also referred to as Nicholas of Kues and Nicolaus Cusanus (), was a German Catholic cardinal, philosopher, theologian, jurist, mathematician, and astronomer. One of the first German proponents of Renai ...

in his ''

Learned Ignorance'' asked whether there was any reason to assert that the Sun (or any other point) was the center of the universe. In parallel to a mystical definition of God, Cusa wrote that "Thus the fabric of the world (''machina mundi'') will ''quasi'' have its center everywhere and circumference nowhere," recalling

Hermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus (from grc, Wiktionary:Ἑρμῆς, Ἑρμῆς ὁ Τρισμέγιστος, "Hermes the Thrice-Greatest"; Classical Latin: la, label=none, Mercurius ter Maximus) is a legendary Hellenistic figure that originated as a Syn ...

.

Medieval India

In India,

Nilakantha Somayaji

Keļallur Nilakantha Somayaji (14 June 1444 – 1544), also referred to as Keļallur Comatiri, was a major mathematician and astronomer of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics. One of his most influential works was the comprehensi ...

(1444–1544), in his ''Aryabhatiyabhasya'', a commentary on Aryabhata's ''Aryabhatiya'', developed a computational system for a geo-heliocentric planetary model, in which the planets orbit the Sun, which in turn orbits the Earth, similar to the

system later proposed by

Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was k ...

. In the ''

Tantrasamgraha

Tantrasamgraha, or Tantrasangraha, (literally, ''A Compilation of the System'') is an important astronomical treatise written by Nilakantha Somayaji, an astronomer/mathematician belonging to the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics.

The ...

'' (1501), Somayaji further revised his planetary system, which was mathematically more accurate at predicting the heliocentric orbits of the interior planets than both the Tychonic and

Copernican models, but did not propose any specific models of the universe. Nilakantha's planetary system also incorporated the Earth's rotation on its axis. Most astronomers of the

Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics

The Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics or the Kerala school was a school of Indian mathematics, mathematics and Indian astronomy, astronomy founded by Madhava of Sangamagrama in Kingdom of Tanur, Tirur, Malappuram district, Malappuram, K ...

seem to have accepted his planetary model.

Renaissance-era astronomy

European astronomy before Copernicus

Some historians maintain that the thought of the

Maragheh observatory

The Maragheh observatory (Persian: رصدخانه مراغه), also spelled Maragha, Maragah, Marageh, and Maraga, was an astronomical observatory established in the mid 13th century under the patronage of the Ilkhanid Hulagu and the directorship ...

, in particular the mathematical devices known as the

Urdi lemma

Al-Urdi (full name: Moayad Al-Din Al-Urdi Al-Amiri Al-Dimashqi) () (d. 1266) was a medieval Syrian Arab astronomer and geometer.

Born circa 1200, presumably (from the nisba ''al‐ʿUrḍī'') in the village of ''ʿUrḍ'' in the Syrian desert b ...

and the

Tusi couple

The Tusi couple is a mathematical device in which a small circle rotates inside a larger circle twice the diameter of the smaller circle. Rotations of the circles cause a point on the circumference of the smaller circle to oscillate back and fort ...

, influenced Renaissance-era European astronomy, and thus was indirectly received by Renaissance-era European astronomy and thus by

Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated ...

.

Copernicus used such devices in the same planetary models as found in Arabic sources. The exact replacement of the

equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plane ...

by two

epicycles used by Copernicus in the ''

Commentariolus

The ''Commentariolus'' (''Little Commentary'') is Nicolaus Copernicus's brief outline of an early version of his revolutionary heliocentric theory of the universe. After further long development of his theory, Copernicus published the mature vers ...

'' was found in an earlier work by

Ibn al-Shatir

ʿAbu al-Ḥasan Alāʾ al‐Dīn ʿAlī ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ansari known as Ibn al-Shatir or Ibn ash-Shatir ( ar, ابن الشاطر; 1304–1375) was an Arab astronomer, mathematician and engineer. He worked as '' muwaqqit'' (موقت, religious ...

(d. c. 1375) of Damascus.

Copernicus' lunar and Mercury models are also identical to Ibn al-Shatir's.

While the influence of the criticism of Ptolemy by Averroes on Renaissance thought is clear and explicit, the claim of direct influence of the

Maragha school, postulated by

Otto E. Neugebauer

Otto Eduard Neugebauer (May 26, 1899 – February 19, 1990) was an Austrian-American mathematician and historian of science who became known for his research on the history of astronomy and the other exact sciences as they were practiced in anti ...

in 1957, remains an open question.

Since the

Tusi couple

The Tusi couple is a mathematical device in which a small circle rotates inside a larger circle twice the diameter of the smaller circle. Rotations of the circles cause a point on the circumference of the smaller circle to oscillate back and fort ...

was used by Copernicus in his reformulation of mathematical astronomy, there is a growing consensus that he became aware of this idea in some way. One possible route of transmission may have been through

Byzantine science

Byzantine science played an important role in the transmission of classical knowledge to the Islamic world and to Renaissance Italy, and also in the transmission of Islamic science to Renaissance Italy. Its rich historiographical tradition preser ...

, which translated some of

al-Tusi Al-Tusi or Tusi is the title of several Iranian scholars who were born in the town of Tous in Khorasan. Some of the scholars with the al-Tusi title include:

* Abu Nasr as-Sarraj al-Tūsī (d. 988), Sufi sheikh and historian.

*Aḥmad al Ṭūsī ( ...

's works from Arabic into

Byzantine Greek

Medieval Greek (also known as Middle Greek, Byzantine Greek, or Romaic) is the stage of the Greek language between the end of classical antiquity in the 5th–6th centuries and the end of the Middle Ages, conventionally dated to the Ottoman co ...

. Several Byzantine Greek manuscripts containing the Tusi couple are still extant in Italy. The Mathematics Genealogy Project suggests that there is a "geneaology" of Nasir al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī → Shams al‐Dīn al‐Bukhārī →

Gregory Chioniades

Gregory Chioniades ( el, Γρηγόριος Χιονιάδης, Grēgorios Chioniadēs; c. 1240 – c. 1320) was a Byzantine Greek astronomer. He traveled to Persia, where he learned Persian mathematical and astronomical science, which he introduce ...

→

Manuel Bryennios Manuel Bryennios or Bryennius ( el, Μανουήλ Βρυέννιος; c. 1275 – c. 1340). was a Byzantine Empire, Byzantine scholar who flourished in Constantinople about 1300 teaching astronomy, mathematics and musical theory.. His only survivin ...

→

Theodore Metochites

Theodore Metochites ( el, Θεόδωρος Μετοχίτης; 1270–1332) was a Byzantine Greek statesman, author, gentleman philosopher, and patron of the arts. From c. 1305 to 1328 he held the position of personal adviser ('' mesazōn'') to e ...

→

Gregory Palamas

Gregory Palamas ( el, Γρηγόριος Παλαμᾶς; c. 1296 – 1359) was a Byzantine Greek theologian and Eastern Orthodox cleric of the late Byzantine period. A monk of Mount Athos (modern Greece) and later archbishop of Thessaloniki, h ...

→

Nilos Kabasilas Neilos Kabasilas (also Nilus Cabasilas; el, Νεῖλος Καβάσιλας ''Neilos Kavasilas''), was a fourteenth-century Greek Palamite theologian who succeeded St. Gregory Palamas as Metropolitan of Thessalonica (1361–1363). Neilos, who was ...

→

Demetrios Kydones

Demetrios Kydones, Latinized as Demetrius Cydones or Demetrius Cydonius ( el, Δημήτριος Κυδώνης; 1324, Thessalonica – 1398, Crete), was a Byzantine Greeks, Greek theologian, translator, author and influential statesman, who s ...

→

Gemistos Plethon

Georgios Gemistos Plethon ( el, Γεώργιος Γεμιστός Πλήθων; la, Georgius Gemistus Pletho /1360 – 1452/1454), commonly known as Gemistos Plethon, was a Greek scholar and one of the most renowned philosophers of the late Byza ...

→

Basilios Bessarion

Bessarion ( el, Βησσαρίων; 2 January 1403 – 18 November 1472) was a Byzantine Greek Renaissance humanist, theologian, Catholic cardinal and one of the famed Greek scholars who contributed to the so-called great revival of letter ...

→

Johannes Regiomontanus

Johannes Müller von Königsberg (6 June 1436 – 6 July 1476), better known as Regiomontanus (), was a mathematician, astrologer and astronomer of the German Renaissance, active in Vienna, Buda and Nuremberg. His contributions were instrumental ...

→

Domenico Maria Novara da Ferrara

Domenico Maria Novara (1454–1504) was an Italian scientist.

Life

Born in Ferrara, for 21 years he was professor of astronomy at the University of Bologna, and in 1500 he also lectured in mathematics at Rome. He was notable as a Platonist ast ...

→ Nicolaus (Mikołaj Kopernik) Copernicus.

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

(1452–1519) wrote "Il sole non si move." ("The Sun does not move.") and he was a student of a student of Bessarion according to the Mathematics Genealogy Project. It has been suggested that the idea of the Tusi couple may have arrived in Europe leaving few manuscript traces, since it could have occurred without the translation of any Arabic text into Latin.

Other scholars have argued that Copernicus could well have developed these ideas independently of the late Islamic tradition.

Copernicus explicitly references several astronomers of the "

Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

" (10th to 12th centuries) in ''De Revolutionibus'':

Albategnius (Al-Battani),

Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psycholog ...

(Ibn Rushd),

Thebit (Thabit Ibn Qurra),

Arzachel (Al-Zarqali), and

Alpetragius (Al-Bitruji), but he does not show awareness of the existence of any of the later astronomers of the Maragha school.

It has been argued that Copernicus could have independently discovered the Tusi couple or took the idea from

Proclus

Proclus Lycius (; 8 February 412 – 17 April 485), called Proclus the Successor ( grc-gre, Πρόκλος ὁ Διάδοχος, ''Próklos ho Diádokhos''), was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, one of the last major classical philosophers ...

's ''Commentary on the First Book of

Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Wikt:Εὐκλείδης, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the ''Euclid's Elements, Elements'' trea ...

'', which Copernicus cited.

Another possible source for Copernicus's knowledge of this mathematical device is the ''Questiones de Spera'' of

Nicole Oresme

Nicole Oresme (; c. 1320–1325 – 11 July 1382), also known as Nicolas Oresme, Nicholas Oresme, or Nicolas d'Oresme, was a French philosopher of the later Middle Ages. He wrote influential works on economics, mathematics, physics, astrology an ...

, who described how a reciprocating linear motion of a celestial body could be produced by a combination of circular motions similar to those proposed by al-Tusi.

The state of knowledge on planetary theory received by Copernicus is summarized in

Georg von Peuerbach

Georg von Peuerbach (also Purbach, Peurbach; la, Purbachius; born May 30, 1423 – April 8, 1461) was an Austrian astronomer, poet, mathematician and instrument maker, best known for his streamlined presentation of Ptolemaic astronomy in the ''Th ...

's ''Theoricae Novae Planetarum'' (printed in 1472 by

Regiomontanus

Johannes Müller von Königsberg (6 June 1436 – 6 July 1476), better known as Regiomontanus (), was a mathematician, astrologer and astronomer of the German Renaissance, active in Vienna, Buda and Nuremberg. His contributions were instrumental ...

). By 1470, the accuracy of observations by the Vienna school of astronomy, of which Peuerbach and Regiomontanus were members, was high enough to make the eventual development of heliocentrism inevitable, and indeed it is possible that Regiomontanus did arrive at an explicit theory of heliocentrism before his death in 1476, some 30 years before Copernicus.

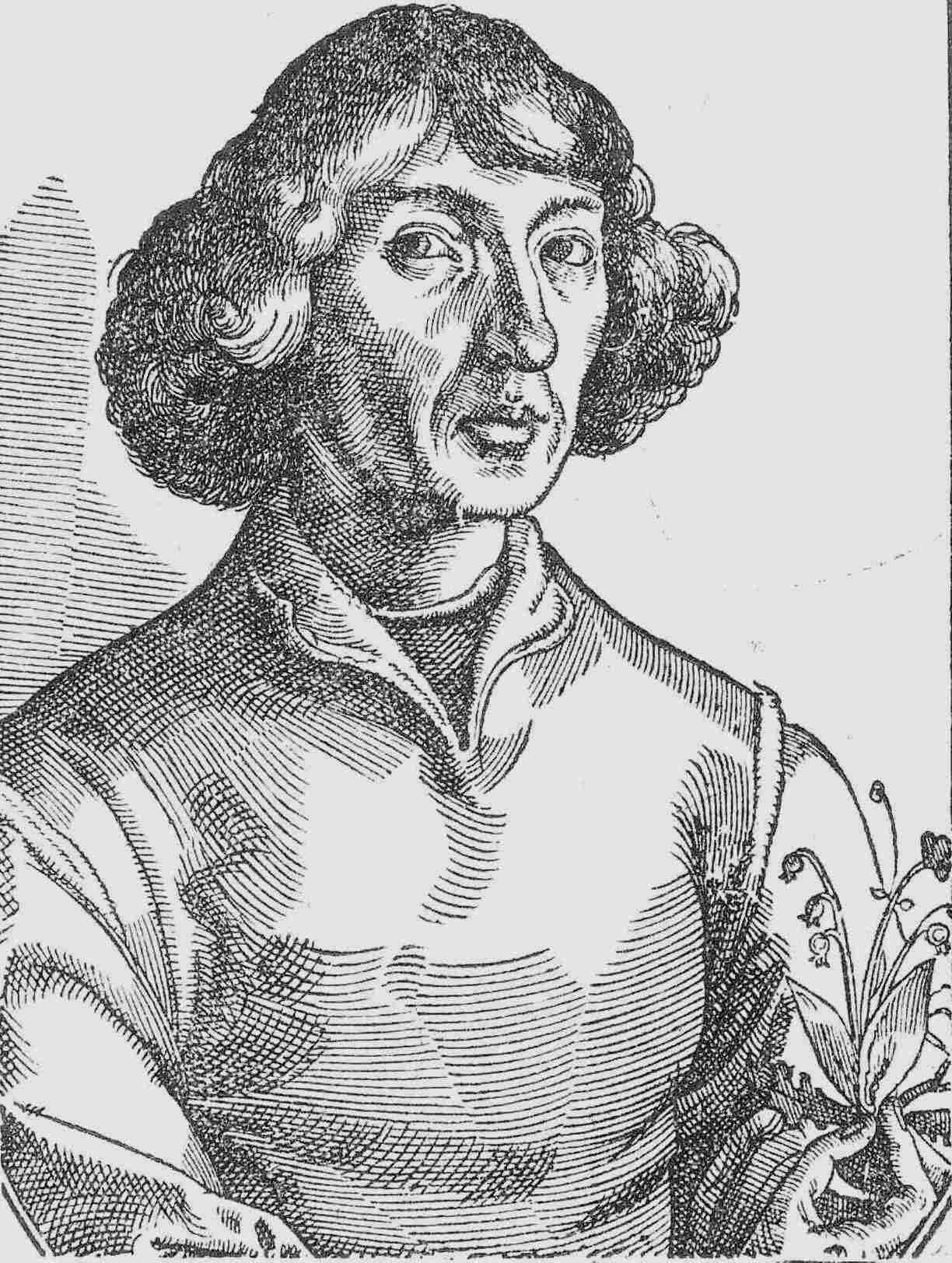

Copernican heliocentrism

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic Church, Catholic cano ...

in his ''

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book, ...

'' ("On the revolution of heavenly spheres", first printed in 1543 in Nuremberg), presented a discussion of a heliocentric model of the universe in much the same way as

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

in the 2nd century had presented his geocentric model in his ''

Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it canoni ...

''.

Copernicus discussed the philosophical implications of his proposed system, elaborated it in geometrical detail, used selected astronomical observations to derive the parameters of his model, and wrote astronomical tables which enabled one to compute the past and future positions of the stars and planets. In doing so, Copernicus moved heliocentrism from philosophical speculation to predictive geometrical astronomy. In reality, Copernicus's system did not predict the planets' positions any better than the Ptolemaic system. This theory resolved the issue of planetary

retrograde motion

Retrograde motion in astronomy is, in general, orbital or rotational motion of an object in the direction opposite the rotation of its primary, that is, the central object (right figure). It may also describe other motions such as precession or ...

by arguing that such motion was only perceived and apparent, rather than

real

Real may refer to:

Currencies

* Brazilian real (R$)

* Central American Republic real

* Mexican real

* Portuguese real

* Spanish real

* Spanish colonial real

Music Albums

* ''Real'' (L'Arc-en-Ciel album) (2000)

* ''Real'' (Bright album) (2010)

...

: it was a

parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. Due to foreshortening, nearby objects ...

effect, as an object that one is passing seems to move backwards against the horizon. This issue was also resolved in the geocentric

Tychonic system

The Tychonic system (or Tychonian system) is a model of the Universe published by Tycho Brahe in the late 16th century, which combines what he saw as the mathematical benefits of the Copernican system with the philosophical and "physical" bene ...

; the latter, however, while eliminating the major

epicycle

In the Hipparchian, Ptolemaic, and Copernican systems of astronomy, the epicycle (, meaning "circle moving on another circle") was a geometric model used to explain the variations in speed and direction of the apparent motion of the Moon, Sun ...

s, retained as a physical reality the irregular back-and-forth motion of the planets, which Kepler characterized as a "

pretzel

A pretzel (), from German pronunciation, standard german: Breze(l) ( and French / Alsatian: ''Bretzel'') is a type of baked bread made from dough that is commonly shaped into a knot. The traditional pretzel shape is a distinctive symmetrical ...

".

Copernicus cited Aristarchus in an early (unpublished) manuscript of ''De Revolutionibus'' (which still survives), stating: "Philolaus believed in the mobility of the earth, and some even say that Aristarchus of Samos was of that opinion." However, in the published version he restricts himself to noting that in works by

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

he had found an account of the theories of

Hicetas

Hicetas ( grc, Ἱκέτας or ; c. 400 – c. 335 BC) was a Greek philosopher of the Pythagorean School. He was born in Syracuse. Like his fellow Pythagorean Ecphantus and the Academic Heraclides Ponticus, he believed that the daily moveme ...

and that

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

had provided him with an account of the

Pythagoreans

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton, ...

,

Heraclides Ponticus

Heraclides Ponticus ( grc-gre, Ἡρακλείδης ὁ Ποντικός ''Herakleides''; c. 390 BC – c. 310 BC) was a Greek philosopher and astronomer who was born in Heraclea Pontica, now Karadeniz Ereğli, Turkey, and migrated to Athens. He ...

,

Philolaus

Philolaus (; grc, Φιλόλαος, ''Philólaos''; ) was a Greek Pythagorean and pre-Socratic philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pytha ...

, and

Ecphantus

Ecphantus or Ecphantos ( grc, Ἔκφαντος) or Ephantus () is a shadowy Greek pre-Socratic philosopher. He may not have actually existed. He is identified as a Pythagorean of the 4th century BCE, and as a supporter of the heliocentric theory. ...

. These authors had proposed a moving Earth, which did not, however, revolve around a central sun.

Reception in Early Modern Europe

Circulation of Commentariolus (published before 1515)

The first information about the heliocentric views of

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic Church, Catholic cano ...

was circulated in manuscript completed some time before May 1, 1514. In 1533,

Johann Albrecht Widmannstetter Johann Albrecht Widmannstetter, also called Widmannstadt, Johannes Albertus or Widmestadius, (1506 – 28 March 1557) was a German humanist, orientalist, philologist, and theologian.

Life

Widmannstetter was born in Nellingen/Blaubeuren near Ulm ...

delivered in Rome a series of lectures outlining Copernicus' theory. The lectures were heard with interest by

Pope Clement VII

Pope Clement VII ( la, Clemens VII; it, Clemente VII; born Giulio de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the ...

and several Catholic

cardinals

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

.

In 1539,

Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

said:

This was reported in the context of a conversation at the dinner table and not a formal statement of faith.

Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

, however, opposed the doctrine over a period of years.

Publication of ''De Revolutionibus'' (1543)

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic Church, Catholic cano ...

published the definitive statement of his system in

''De Revolutionibus'' in 1543. Copernicus began to write it in 1506 and finished it in 1530, but did not publish it until the year of his death. Although he was in good standing with the Church and had dedicated the book to

Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III ( la, Paulus III; it, Paolo III; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549), born Alessandro Farnese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death in November 1549.

He came to ...

, the published form contained an unsigned preface by

Osiander

Andreas Osiander (; 19 December 1498 – 17 October 1552) was a German Lutheran theologian and Protestant reformer.

Career

Born at Gunzenhausen, Ansbach, in the region of Franconia, Osiander studied at the University of Ingolstadt before b ...

defending the system and arguing that it was useful for computation even if its hypotheses were not necessarily true. Possibly because of that preface, the work of Copernicus inspired very little debate on whether it might be

heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

during the next 60 years. There was an early suggestion among

Dominicans that the teaching of heliocentrism should be banned, but nothing came of it at the time.

Some years after the publication of ''De Revolutionibus''

John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

preached a sermon in which he denounced those who "pervert the order of nature" by saying that "the sun does not move and that it is the earth that revolves and that it turns".

Tycho Brahe's geo-heliocentric system (c. 1587)

Prior to the publication of ''De Revolutionibus'', the most widely accepted system had been proposed by

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

, in which the

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

was the center of the universe and all celestial bodies orbited it.

Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was k ...

, arguably the most accomplished astronomer of his time, advocated against Copernicus's heliocentric system and for an alternative to the Ptolemaic geocentric system: a geo-heliocentric system now known as the

Tychonic system

The Tychonic system (or Tychonian system) is a model of the Universe published by Tycho Brahe in the late 16th century, which combines what he saw as the mathematical benefits of the Copernican system with the philosophical and "physical" bene ...

in which the Sun and Moon orbit the Earth, Mercury and Venus orbit the Sun inside the Sun's orbit of the Earth, and Mars, Jupiter and Saturn orbit the Sun outside the Sun's orbit of the Earth.

Tycho appreciated the Copernican system, but objected to the idea of a moving Earth on the basis of physics, astronomy, and religion. The

Aristotelian physics

Aristotelian physics is the form of natural science described in the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC). In his work ''Physics'', Aristotle intended to establish general principles of change that govern all natural bodies, b ...

of the time (modern Newtonian physics was still a century away) offered no physical explanation for the motion of a massive body like Earth, whereas it could easily explain the motion of heavenly bodies by postulating that they were made of a different sort substance called

aether that moved naturally. So Tycho said that the Copernican system "... expertly and completely circumvents all that is superfluous or discordant in the system of Ptolemy. On no point does it offend the principle of mathematics. Yet it ascribes to the Earth, that hulking, lazy body, unfit for motion, a motion as quick as that of the aethereal torches, and a triple motion at that." Likewise, Tycho took issue with the vast distances to the stars that Aristarchus and Copernicus had assumed in order to explain the lack of any visible parallax. Tycho had measured the

apparent sizes of stars (now known to be illusory), and used geometry to calculate that in order to both have those apparent sizes and be as far away as heliocentrism required, stars would have to be huge (much larger than the sun; the size of Earth's orbit or larger). Regarding this Tycho wrote, "Deduce these things geometrically if you like, and you will see how many absurdities (not to mention others) accompany this assumption

f the motion of the earth

F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''.

Hist ...

by inference." He also cited the Copernican system's "opposition to the authority of Sacred Scripture in more than one place" as a reason why one might wish to reject it, and observed that his own geo-heliocentric alternative "offended neither the principles of physics nor Holy Scripture".

The Jesuit astronomers in Rome were at first unreceptive to Tycho's system; the most prominent,

Clavius

Christopher Clavius, SJ (25 March 1538 – 6 February 1612) was a Jesuit German mathematician, head of mathematicians at the Collegio Romano, and astronomer who was a member of the Vatican commission that accepted the proposed calendar inve ...

, commented that Tycho was "confusing all of astronomy, because he wants to have

Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury (planet), Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Mars (mythology), Roman god of war. Mars is a terr ...

lower than the Sun." However, after the advent of the telescope showed problems with some geocentric models (by demonstrating that Venus circles the Sun, for example), the Tychonic system and variations on that system became popular among geocentrists, and the Jesuit astronomer

Giovanni Battista Riccioli

Giovanni Battista Riccioli, SJ (17 April 1598 – 25 June 1671) was an Italian astronomer and a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. He is known, among other things, for his experiments with pendulums and with falling bodies, for his discussion ...

would continue Tycho's use of physics, stellar astronomy (now with a telescope), and religion to argue against heliocentrism and for Tycho's system well into the seventeenth century.

Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno (; ; la, Iordanus Brunus Nolanus; born Filippo Bruno, January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, mathematician, poet, cosmological theorist, and Hermetic occultist. He is known for his cosmologic ...

(d. 1600) is the only known person to defend Copernicus's heliocentrism in his time.

Using measurements made at Tycho's observatory,

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

developed his

laws of planetary motion

In astronomy, Kepler's laws of planetary motion, published by Johannes Kepler between 1609 and 1619, describe the orbits of planets around the Sun. The laws modified the heliocentric theory of Nicolaus Copernicus, replacing its circular orbit ...

between 1609 and 1619. In ''

Astronomia nova

''Astronomia nova'' (English: ''New Astronomy'', full title in original Latin: ) is a book, published in 1609, that contains the results of the astronomer Johannes Kepler's ten-year-long investigation of the motion of Mars.

One of the most si ...

'' (1609), Kepler made a diagram of the movement of Mars in relation to Earth if Earth were at the center of its orbit, which shows that Mars' orbit would be completely imperfect and never follow along the same path. To solve the apparent derivation of Mars' orbit from a perfect circle, Kepler derived both a mathematical definition and, independently, a matching ellipse around the Sun to explain the motion of the red planet.

Between 1617 and 1621, Kepler developed a heliocentric model of the Solar System in ''

Epitome astronomiae Copernicanae

The ''Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae'' was an astronomy book on the heliocentric system published by Johannes Kepler in the period 1618 to 1621. The first volume (books I–III) was printed in 1618, the second (book IV) in 1620, and the third ...

'', in which all the planets have elliptical orbits. This provided significantly increased accuracy in predicting the position of the planets. Kepler's ideas were not immediately accepted, and Galileo for example ignored them. In 1621, ''Epitome astronomia Copernicanae'' was placed on the Catholic Church's index of prohibited books despite Kepler being a Protestant.

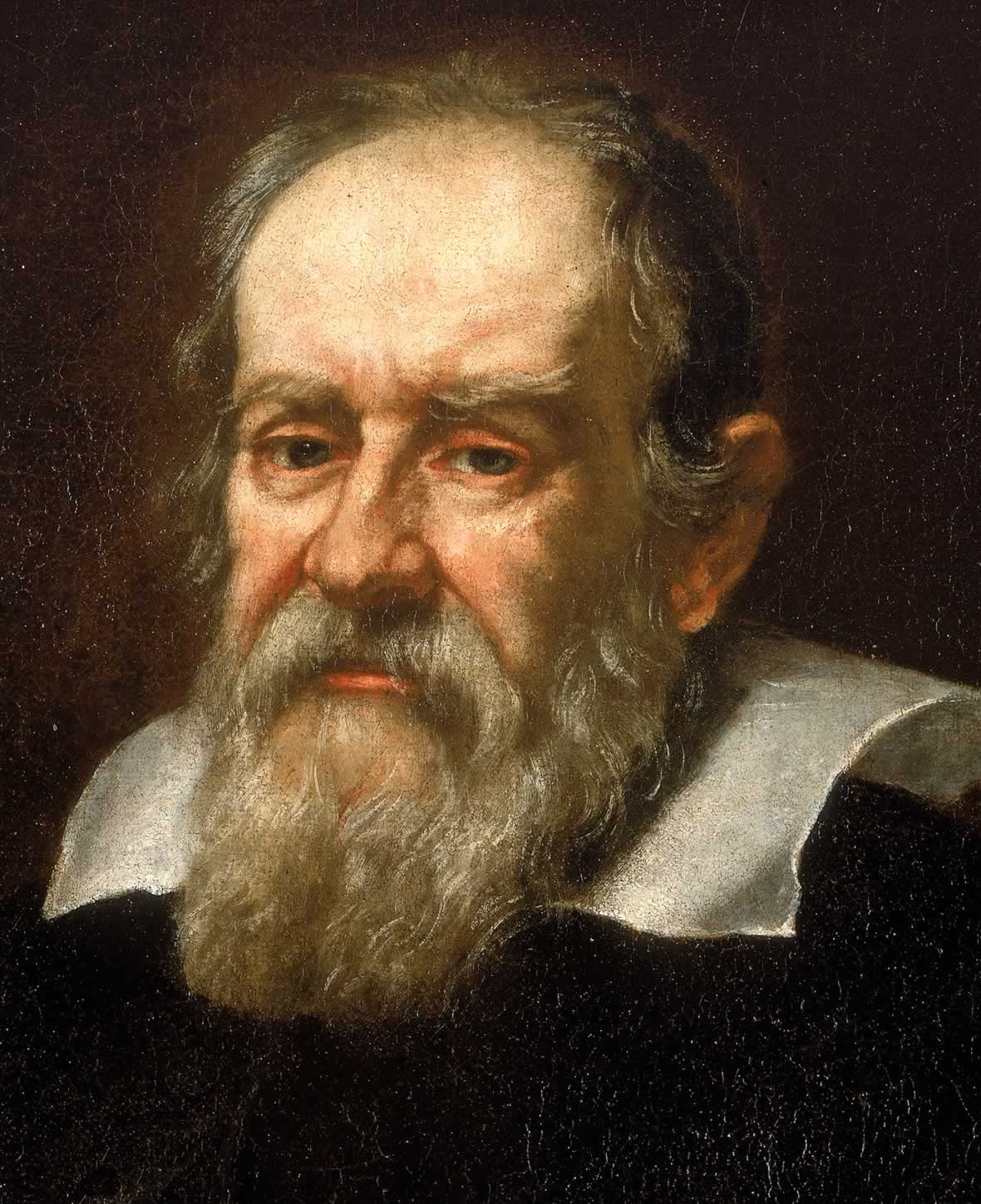

Galileo Galilei and 1616 ban against Copernicanism

Galileo was able to look at the night sky with the newly invented telescope. He published his discoveries that

Jupiter is orbited by moons and that the Sun rotates in his ''

Sidereus Nuncius

''Sidereus Nuncius'' (usually ''Sidereal Messenger'', also ''Starry Messenger'' or ''Sidereal Message'') is a short astronomical treatise (or ''pamphlet'') published in New Latin by Galileo Galilei on March 13, 1610. It was the first published ...

'' (1610) and ''

Letters on Sunspots

'' Letters on Sunspots '' (''Istoria e Dimostrazioni intorno alle Macchie Solari'') was a pamphlet written by Galileo Galilei in 1612 and published in Rome by the Accademia dei Lincei in 1613. In it, Galileo outlined his recent observation of dark ...

'' (1613), respectively. Around this time, he also announced that

Venus exhibits a full range of phases (satisfying an argument that had been made against Copernicus). As the Jesuit astronomers confirmed Galileo's observations, the Jesuits moved away from the Ptolemaic model and toward Tycho's teachings.

In his 1615 "

Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina

The "Letter to The Grand Duchess Christina" is an essay written in 1615 by Galileo Galilei. The intention of this letter was to accommodate Copernicanism with the doctrines of the Catholic Church. Galileo tried to use the ideas of Church Fathers ...

", Galileo defended heliocentrism, and claimed it was not contrary to Holy Scripture. He took

Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berbers, Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia (Roman pr ...

's position on Scripture: not to take every passage literally when the scripture in question is in a Bible book of poetry and songs, not a book of instructions or history. The writers of the Scripture wrote from the perspective of the terrestrial world, and from that vantage point the Sun does rise and set. In fact, it is the Earth's rotation which gives the impression of the Sun in motion across the sky.

In February 1615, prominent Dominicans including Thomaso Caccini and Niccolò Lorini brought Galileo's writings on heliocentrism to the attention of the Inquisition, because they appeared to violate Holy Scripture and the decrees of the

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trento, Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italian Peninsula, Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation ...

. Cardinal and Inquisitor

Robert Bellarmine

Robert Bellarmine, SJ ( it, Roberto Francesco Romolo Bellarmino; 4 October 1542 – 17 September 1621) was an Italian Jesuit and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. He was canonized a saint in 1930 and named Doctor of the Church, one of only ...

was called upon to adjudicate, and wrote in April that treating heliocentrism as a real phenomenon would be "a very dangerous thing," irritating philosophers and theologians, and harming "the Holy Faith by rendering Holy Scripture as false."

In January 1616, Msgr.

Francesco Ingoli

Francesco Ingoli (21 November 1578 – 24 April 1649) was an Italian Catholic priest, lawyer and professor of civil and canon law.

Early life

Born in Ravenna Italy, Ingoli learned a number of languages, including Arabic, and graduated from t ...

addressed an essay to Galileo disputing the Copernican system. Galileo later stated that he believed this essay to have been instrumental in the ban against Copernicanism that followed in February. According to Maurice Finocchiaro, Ingoli had probably been commissioned by the Inquisition to write an expert opinion on the controversy, and the essay provided the "chief direct basis" for the ban. The essay focused on eighteen physical and mathematical arguments against heliocentrism. It borrowed primarily from the arguments of Tycho Brahe, and it notedly mentioned the problem that heliocentrism requires the stars to be much larger than the Sun. Ingoli wrote that the great distance to the stars in the heliocentric theory "clearly proves ... the fixed stars to be of such size, as they may surpass or equal the size of the orbit circle of the Earth itself." Ingoli included four theological arguments in the essay, but suggested to Galileo that he focus on the physical and mathematical arguments. Galileo did not write a response to Ingoli until 1624.

In February 1616, the Inquisition assembled a committee of theologians, known as qualifiers, who delivered their unanimous report condemning heliocentrism as "foolish and absurd in philosophy, and formally heretical since it explicitly contradicts in many places the sense of Holy Scripture." The Inquisition also determined that the Earth's motion "receives the same judgement in philosophy and ... in regard to theological truth it is at least erroneous in faith." Bellarmine personally ordered Galileo

In March 1616, after the Inquisition's injunction against Galileo, the papal

Master of the Sacred Palace

In the Roman Catholic Church, Theologian of the Pontifical Household ( la, Pontificalis Domus Doctor Theologus) is a Roman Curial office which has always been entrusted to a Friar Preacher of the Dominican Order and may be described as the pope's ...

,

Congregation of the Index

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications deemed heretical or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index (a former Dicastery of the Roman Curia), and Catholics were forbidde ...

, and the Pope banned all books and letters advocating the Copernican system, which they called "the false Pythagorean doctrine, altogether contrary to Holy Scripture."

In 1618, the Holy Office recommended that a modified version of Copernicus' ''De Revolutionibus'' be allowed for use in calendric calculations, though the original publication remained forbidden until 1758.

Pope Urban VIII

Pope Urban VIII ( la, Urbanus VIII; it, Urbano VIII; baptised 5 April 1568 – 29 July 1644), born Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 August 1623 to his death in July 1644. As po ...

encouraged Galileo to publish the pros and cons of heliocentrism. Galileo's response, ''

Dialogue concerning the two chief world systems

The ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' (''Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo'') is a 1632 Italian-language book by Galileo Galilei comparing the Copernican system with the traditional Ptolemaic system. It was transl ...

'' (1632), clearly advocated heliocentrism, despite his declaration in the preface that,

I will endeavour to show that all experiments that can be made upon the Earth are insufficient means to conclude for its mobility but are indifferently applicable to the Earth, movable or immovable...['' The Systeme of the World: in Four Dialogues'' (1661) Thomas Salusbury translation of ''Dialogo sopra i Due Massi Sistemi del Mondo'' (1632)]

and his straightforward statement,

I might very rationally put it in dispute, whether there be any such centre in nature, or no; being that neither you nor any one else hath ever proved, whether the World be finite and figurate, or else infinite and interminate; yet nevertheless granting you, for the present, that it is finite, and of a terminate Spherical Figure, and that thereupon it hath its centre...

Some ecclesiastics also interpreted the book as characterizing the Pope as a simpleton, since his viewpoint in the dialogue was advocated by the character

Simplicio. Urban VIII became hostile to Galileo and he was again summoned to Rome. Galileo's trial in 1633 involved making fine distinctions between "teaching" and "holding and defending as true". For advancing heliocentric theory Galileo was forced to recant Copernicanism and was put under house arrest for the last few years of his life. According to J. L. Heilbron, informed contemporaries of Galileo's "appreciated that the reference to heresy in connection with Galileo or Copernicus had no general or theological significance."

In 1664,

Pope Alexander VII

Pope Alexander VII ( it, Alessandro VII; 13 February 159922 May 1667), born Fabio Chigi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 April 1655 to his death in May 1667.

He began his career as a vice- papal legate, an ...

published his ''

Index Librorum Prohibitorum

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications deemed heretical or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index (a former Dicastery of the Roman Curia), and Catholics were forbidden ...

Alexandri VII Pontificis Maximi jussu editus'' (Index of Prohibited Books, published by order of Alexander VII,

P.M.) which included all previous condemnations of heliocentric books.

Age of Reason

René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathem ...