Harald Poelchau on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Harald Poelchau (5 October 1903 in

Poelchau served as executive director of the in Berlin and as assistant to Paul Tillich at

Poelchau served as executive director of the in Berlin and as assistant to Paul Tillich at

* On 30 November 1971, Harald and Dorothee Poelchau were recognised by the

* On 30 November 1971, Harald and Dorothee Poelchau were recognised by the

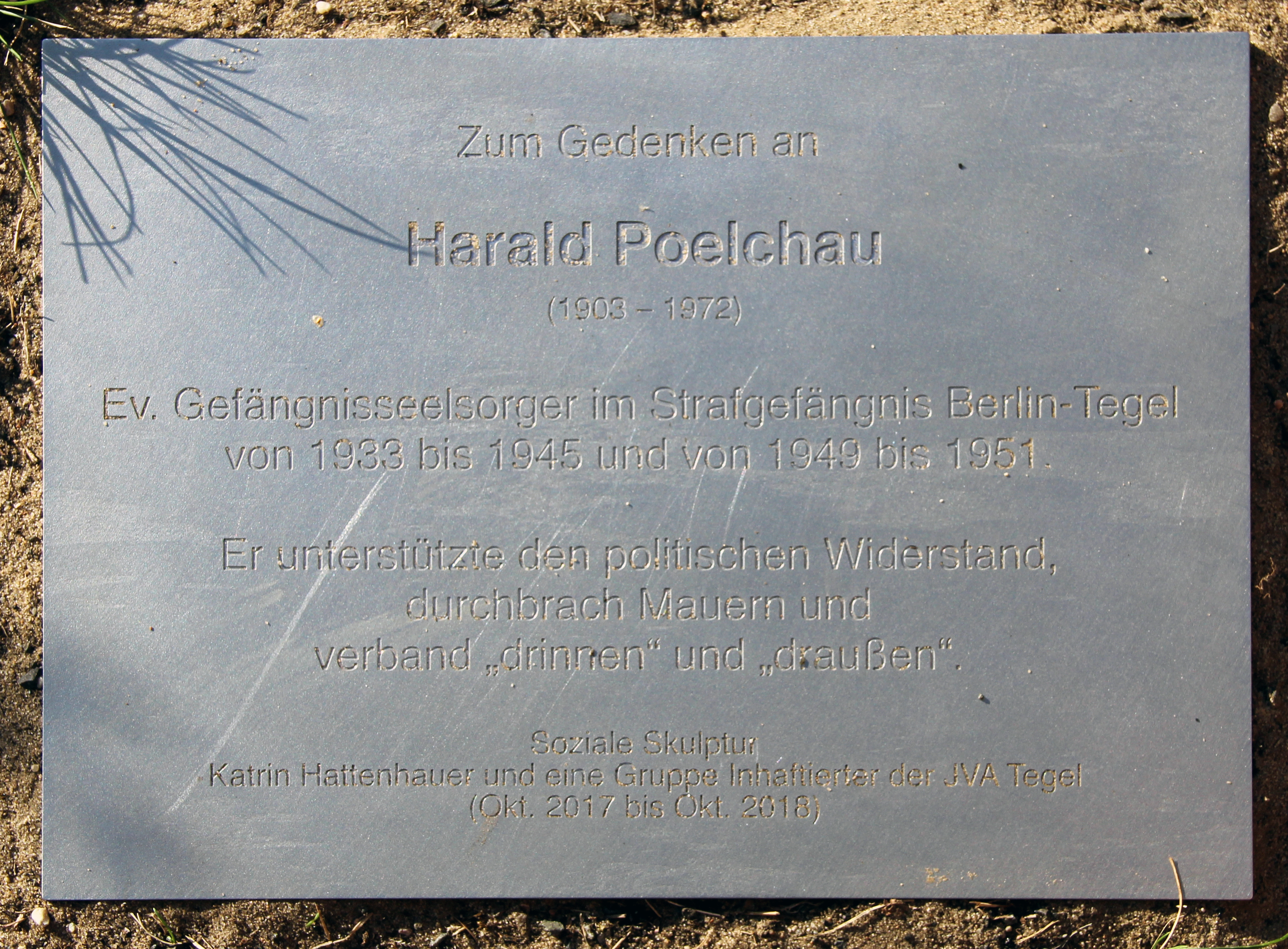

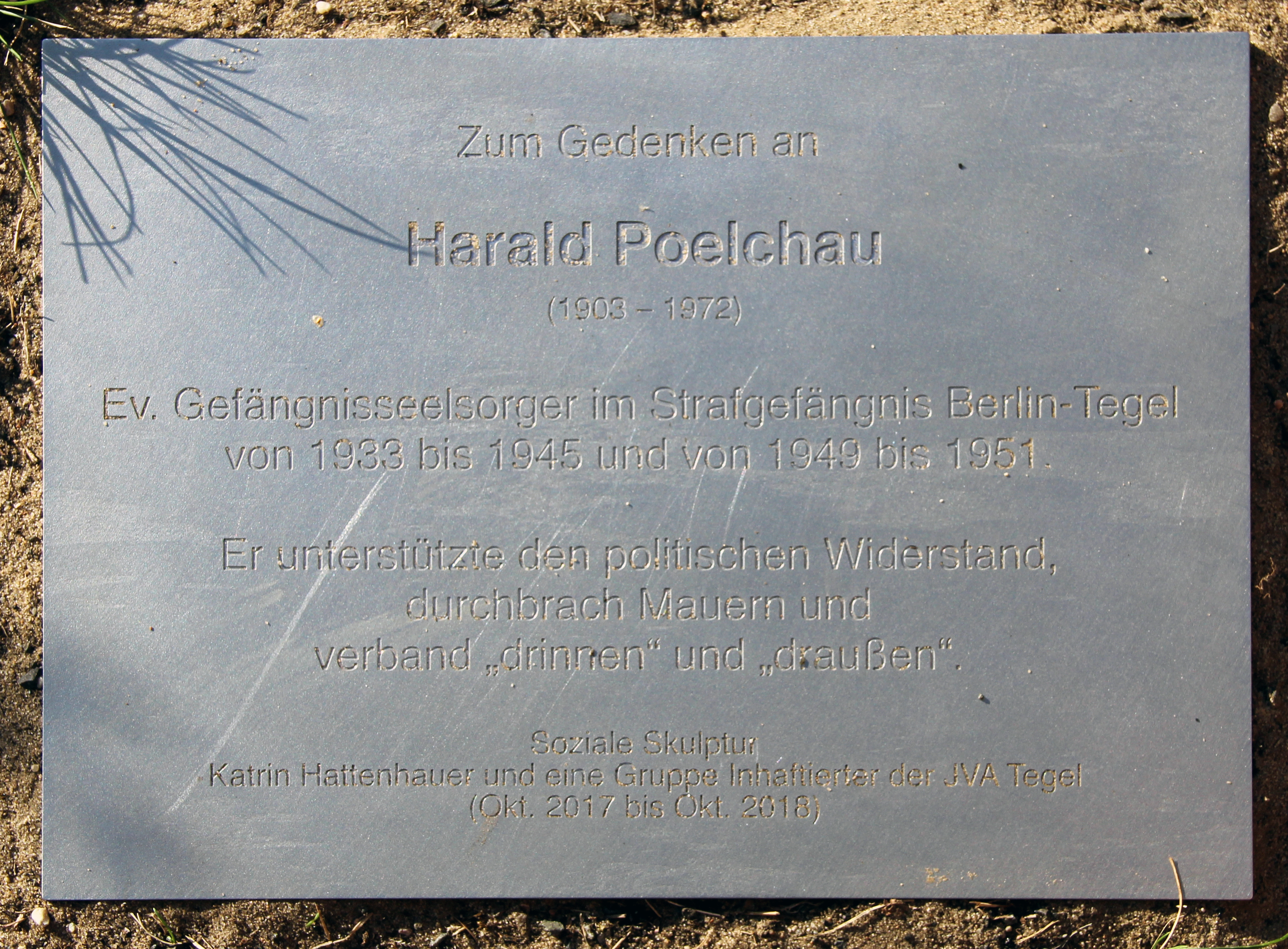

Memorial - Harald Poelchau - Berlin - Justizvollzugsanstalt Tegel

{{DEFAULTSORT:Poelchau, Harald 1903 births 1972 deaths People from Potsdam German Righteous Among the Nations Protestants in the German Resistance University of Tübingen alumni University of Marburg alumni Prison chaplains German resistance members Protestant anti-fascists

Potsdam

Potsdam () is the capital and, with around 183,000 inhabitants, largest city of the German state of Brandenburg. It is part of the Berlin/Brandenburg Metropolitan Region. Potsdam sits on the River Havel, a tributary of the Elbe, downstream of B ...

; 29 April 1972 in West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

) was a German prison chaplain, religious socialist and member of the resistance against the Nazis. Poelchau grew up in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

. During the early 1920's, he studied Protestant theology

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

at the University of Tübingen

The University of Tübingen, officially the Eberhard Karl University of Tübingen (german: Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen; la, Universitas Eberhardina Carolina), is a public research university located in the city of Tübingen, Baden-Wü ...

and the University of Marburg

The Philipps University of Marburg (german: Philipps-Universität Marburg) was founded in 1527 by Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, which makes it one of Germany's oldest universities and the oldest still operating Protestant university in the wor ...

, followed by social work at the College of Political Science of Berlin. Poelchau gained a doctorate under Paul Tillich at Frankfurt University

Goethe University (german: link=no, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main) is a university located in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. It was founded in 1914 as a citizens' university, which means it was founded and funded by the wealt ...

. In 1933, he became a prison chaplain in the Berlin prisons. With the coming of the Nazi regime in 1933, he became am anti-fascist. During the war, Poelchau and his wife Dorothee Poelchau helped victims of the Nazi's, hiding them and helping them escape. At the same time, as a prison chaplain he gave comfort to the many people in prison and those sentenced to death. After the war, he became involved in the reform of prisons in East Germany. In 1971, Yad Vashem named Poelchau and his wife ''Righteous Among the Nations''.

Life

Poelchau was the son of Harald (1866-1938) and Elisabeth Poelchau (née Riem, 1871–1945) and was brought up in the Silesian village of Brauchitschdorf. His father was a Lutheranpastor

A pastor (abbreviated as "Pr" or "Ptr" , or "Ps" ) is the leader of a Christian congregation who also gives advice and counsel to people from the community or congregation. In Lutheranism, Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy and ...

in the village. Poelchau attended the Ritterakademie Gymnasium in Liegnitz, where he participated in Bible classes and became involved in the German Youth Movement

The German Youth Movement (german: Die deutsche Jugendbewegung) is a collective term for a cultural and educational movement that started in 1896. It consists of numerous associations of young people that focus on outdoor activities. The movement ...

(Jugendbewegung), which influenced him to turn away from a rural conservative piety.

At the University of Tübingen

The University of Tübingen, officially the Eberhard Karl University of Tübingen (german: Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen; la, Universitas Eberhardina Carolina), is a public research university located in the city of Tübingen, Baden-Wü ...

, Harald Poelchau met the librarian Dorothee Ziegele (1902-1977). The couple married on 12 April 1928, lived in Berlin and cultivated a large group of friends and acquaintances, that proved highly valuable after the handover of power to the Nazis. In 1938 the couple's son, also baptised Harald, was born, and in 1945 Harald's daughter Andrea Siemsen.

Education

After graduating from the Ritterakademie Liegnitz in 1921, he studiedProtestant theology

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

at the , at the University of Tübingen

The University of Tübingen, officially the Eberhard Karl University of Tübingen (german: Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen; la, Universitas Eberhardina Carolina), is a public research university located in the city of Tübingen, Baden-Wü ...

, and the University of Marburg

The Philipps University of Marburg (german: Philipps-Universität Marburg) was founded in 1527 by Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, which makes it one of Germany's oldest universities and the oldest still operating Protestant university in the wor ...

from 1922. In Tübingen he was secretary of the youth organisation . The Christian socialist

Christian socialism is a religious and political philosophy that blends Christianity and socialism, endorsing left-wing politics and socialist economics on the basis of the Bible and the teachings of Jesus. Many Christian socialists believe capi ...

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

Paul Tillich

Paul Johannes Tillich (August 20, 1886 – October 22, 1965) was a German-American Christian existentialist philosopher, religious socialist, and Lutheran Protestant theologian who is widely regarded as one of the most influential theologi ...

, who taught in Marburg in 1924, was the decisive, intellectual influence on him. Tillich became a lifelong friend and mentor. As a work student at Robert Bosch

Robert Bosch (23 September 1861 – 12 March 1942) was a German industrialist, engineer and inventor, founder of Robert Bosch GmbH.

Biography

Bosch was born in Albeck, a village to the northeast of Ulm in southern Germany as the eleventh of t ...

company in Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the ...

, he gained an insight into the world of workers and industry. After his first theological exam

An examination (exam or evaluation) or test is an educational assessment intended to measure a test-taker's knowledge, skill, aptitude, physical fitness, or classification in many other topics (e.g., beliefs). A test may be administered verba ...

in 1927 in Breslau, he studied social welfare and state welfare policy at the German Academy for Politics in Berlin.

Career

Poelchau served as executive director of the in Berlin and as assistant to Paul Tillich at

Poelchau served as executive director of the in Berlin and as assistant to Paul Tillich at Frankfurt University

Goethe University (german: link=no, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main) is a university located in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. It was founded in 1914 as a citizens' university, which means it was founded and funded by the wealt ...

. In 1931, he passed his second state exam in Berlin and wrote his doctoral thesis under Tillich titled: ''Die sozialphilosophischen Anschauungen der deutschen Wohlfahrtsgesetzgebung'' (The Social Philosophical Views of German Welfare Legislation). The paper was published in 1932 as a book titled ''Das Menschenbild des Fürsorgerechtes: Eine ethisch-soziologische Untersuchung'' (The Image of Man in the Law of Welfare: An Ethical-Sociological Investigation).

Poelchau applied for a position as prison chaplain at the end of 1932 and was instated on 1 April 1933 as the first clergyman in a prison appointed under the Nazi regime. As an official in the Justice Department he worked at Tegel Prison

Tegel Prison is a penal facility in the borough of Reinickendorf in the north of the German state of Berlin. The prison is one of the Germany's largest prisons.

Structure and numbers

Tegel Prison is a closed prison. It is currently divided into ...

in Berlin as well as at several other prisons such as Plötzensee and Moabit. He was opposed to the Nazis from the beginning, but did not join the Confessing Church

The Confessing Church (german: link=no, Bekennende Kirche, ) was a movement within German Protestantism during Nazi Germany that arose in opposition to government-sponsored efforts to unify all Protestant churches into a single pro-Nazi German E ...

(Bekennende Kirche).

World War II

With the beginning of theWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in 1939, death sentences against opposition members increased. Poelchau soon became an important source of support for the victims of Nazi persecution, and gave spiritual comfort to hundreds of people sentenced to death as they faced execution After the unsuccessful coup attempt of 20 July 1944, many of his close friends were sentenced to death. To help their families, he would smuggle letters and messages in and out of the prison cells.

In 1937, the first political prisoners began to appear that were members of the prohibited Communist Party. Poelchau cared for Robert Stamm Robert Stamm (16 July 1900 – 4 November 1937) was a German politician, a Communist (KPD) member of the Reichstag from Bremen, and a victim of the Nazi régime.

Already by the age of 14, Robert Stamm had become involved with the Socialist You ...

and Adolf Rembte

Adolf Rembte (21 July 1902 - 4 November 1937) was a German communist and resistance fighter against the Nazi régime.

On 14 June 1937, he was found guilty of "preparing a treasonous enterprise" and was executed by beheading on 4 November 1937 ...

who were executed in november of that year, in Plötzensee.

In October 1941, the deportation of Jews from Germany began. Poelchau knew early on that only an escape into hiding would ensure survival. The refugees were supposed to call him at his office in Tegel and only talk if he answered with the code word "Tegel". But the actual conversation took place in his office, deep inside the prison walls. Supported by his wife, he arranged accommodations among his large group of acquaintances. These included Gertie Siemsen

Gertie may refer to:

People

* Gertie Brown (1878–1934), vaudeville performer and one of the first African-American film actresses

* Gertie Eggink (born 1980), Dutch sidecarcross rider

* Gertie Evenhuis (1927–2005), Dutch writer of children's ...

, a long-time friend from his student days, Willi Kranz, canteen manager in the Tegel and Plötzensee prisons and his partner Auguste Leißner, Hermann Sietmann and Otto Horstmeier, two former political prisoners, the couple Hildegard and Hans Reinhold Schneider who worked in social welfare and taught school (they were the parents of esine Schwanwho later became a political scientist). They also included , a pastor's wife (who were also named ''Righteous Among the Nations'' for hiding Jews), and her daughter , the prison doctor Hilde Westrick, and the physicist and his wife Hildegard.

In 1942, the Soviet led Red Orchestra espionage network was uncovered by the Abwehr

The ''Abwehr'' (German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', but the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context; ) was the German military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ''Wehrmacht'' from 1920 to 1944. A ...

in Germany, France and the Low Countries and many of its members were imprisoned and executed. Poelchau provided support for Arvid and his American wife Mildred Harnack

Mildred Elizabeth Harnack ( Fish; September 16, 1902 – February 16, 1943) was an American literary historian, translator, and member of the German resistance against the Nazi regime. After marrying Arvid Harnack, she moved to Germany in 192 ...

, John Rittmeister, Harro and Libertas Schulze-Boysen

Libertas "Libs" Schulze-Boysen, born Libertas Viktoria Haas-Heye (20 November 1913 in Paris – 22 December 1942 in Plötzensee Prison ) was a German aristocrat and resistance fighter against the Nazis. From the early 1930s to 1940, Libs attem ...

, Kurt and Elisabeth Schumacher, Walter Husemann, Adam Kuckhoff

Adam Kuckhoff (, 30 August 1887 – 5 August 1943) was a German writer, journalist, and German resistance to Nazism, German resistance member of the anti-fascist resistance group that was later called the Red Orchestra (espionage), Red Orchestra ...

, and many others.

Only a few of those rescued or helped by the Poelchaus are known by name. One Jewish family, Manfred and Margarete Latte with their son Konrad, fled from Breslau after they learned they were to be deported, to Berlin where they went into hiding. Through a family friend, Ursula Teichmann, they made contact with Poelchau in late February 1943 and turned to him for help. He provided them with ration cards, cash and found accommodation for the family. He also found work for Manfred Latte, who became an ice delivery helper, and later gardener. As Konrad Latte was of a typical age to be conscripted

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

Poelchau filled in a registration card for the Volkssturm

The (; "people's storm") was a levée en masse national militia established by Nazi Germany during the last months of World War II. It was not set up by the German Army, the ground component of the combined German ''Wehrmacht'' armed forces, ...

, a national militia that was independent of the German army, to provide a cover ID.

Konrad Latte, established contact between Poelchau and Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, the co-founder of the resistance group , along with the conductor Leo Borchard

Lew Ljewitsch "Leo" Borchard (31 March 1899 – 23 August 1945) was a German-Russian conductor and briefly musical director of the Berlin Philharmonic.

Biography

Borchard was born in Moscow to German parents, and grew up in Saint Petersbu ...

. The resistance group was motivated more by humanitarian concerns, rather than ideology and was made up on middle-class professionals. They began to work with Poelchau, who could arrange accommodations, forged identity papers, and food ration stamps. The Gestapo apprehended the Latte family in October 1943. Manfred and Margarete Latte were immediately deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp. Konrad Latte managed to escape the deportation center and went back into hiding.

Rita Neumann had been in hiding with the resistance fighter and Protestant pastor's wife since August 1943. Her brother Ralph Neumann joined Wendland. The siblings worked as bicycle couriers for Poelchau. In February 1945, they were arrested along with Wendland. The siblings managed to escape the Große Hamburger Straße deportation collection camp and make their way back to Poelchau's door. Other people Poelchau helped were Ilse Schwarz and her daughter Evelyne, a young stenographer Ursula Reuber, Anna Drach, Edith Bruck

Edith Bruck (born 3 May 1931)Edith Bruck: ''Who love you like this''. Philadelphia: Paul Dry Books, 2001, p. 3; Philip Balma: ''Edith Bruck in the Mirror. Fictional Transitions and Cinematic Narratives'' (''Shofar Supplements in Jewish Studies'') ...

, Charlotte Paech, part of the Baum group and Charlotte Bischoff

Charlotte Bischoff (; 5 October 1901 – 4 November 1994) was a German Communist and German resistance to Nazism, Resistance fighter against National Socialism.

Biography

Early years

Charlotte Wielepp was born in Berlin. Her father was Alfre ...

.

From 1941, Poelchau belonged to a resistance group of people around Helmuth James Graf von Moltke known as the Kreisau Circle

The Kreisau Circle (German: ''Kreisauer Kreis'', ) (1940–1944) was a group of about twenty-five German dissidents in Nazi Germany led by Helmuth James von Moltke, who met at his estate in the rural town of Kreisau, Silesia. The circle was com ...

. He took part in the first meeting of the group. After the attempted coup of 20 July 1944, the prison chaplain cared for many of those involved in the assassination. Harald Poelchau's extensive resistance involvement remained undiscovered until the end of the war.

After the war

In 1945, he co-founded the (Hilfswerk der Evangelischen Kirchen) in Stuttgart, together with the theologian and resistance fighterEugen Gerstenmaier

Eugen Karl Albrecht Gerstenmaier (25 August 1906 – 13 March 1986, in Oberwinter) was a German Evangelical theologian, resistance fighter in the Third Reich, and a CDU politician. From 1954 to 1969, he served as President of the Bundestag. With ...

and became its General Secretary. The Aid Organisation took care of the problems of refugees, the construction of apartments (settlement work) and homes for the aged and apprentices, and emergency churches. After returning to Berlin in 1946, Poelchau became involved in reforming the prison system in the Soviet occupation zone as councillor of the Central Administration of Justice . This was connected with a teaching assignment for criminology

Criminology (from Latin , "accusation", and Ancient Greek , ''-logia'', from λόγος ''logos'' meaning: "word, reason") is the study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is an interdisciplinary field in both the behavioural and so ...

and prison science at the Humboldt University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative o ...

. Together with Ottomar Geschke and Heinrich Grüber

Heinrich Grüber (; 24 June 1891 – 29 November 1975) was a Reformed theologian, opponent of Nazism and pacifist.

Life

Until 1933

Heinrich Grüber was born on 24 June 1891 in Stolberg in the Prussian Rhine Province (today part of North Rhin ...

he sat on the central board of the (Vereinigung der Verfolgten des Naziregimes – Bund der Antifaschistinnen und Antifaschisten). When Poelchau was unable to push through his ideas for prison reform in the east, he resigned his position. From 1949 to 1951, he was again appointed as the prison chaplain at Tegel Prison

Tegel Prison is a penal facility in the borough of Reinickendorf in the north of the German state of Berlin. The prison is one of the Germany's largest prisons.

Structure and numbers

Tegel Prison is a closed prison. It is currently divided into ...

. In 1951, Bishop Otto Dibelius

Friedrich Karl Otto Dibelius (15 May 1880 – 31 January 1967) was a German bishop of the Evangelical Church in Berlin-Brandenburg, a self-described anti-Semite who up to 1934 a conservative who became a staunch opponent of Nazism and commu ...

appointed him as the first social and industrial pastor of the Protestant Church in Berlin-Brandenburg (Industrie- und Sozialpfarramt) with the mission to connect the church to the industrial workers. Harald Poelchau dedicated himself to this task until his death in 1972. He is buried in the Zehlendorf cemetery in Berlin.

Awards and honours

* On 30 November 1971, Harald and Dorothee Poelchau were recognised by the

* On 30 November 1971, Harald and Dorothee Poelchau were recognised by the Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

memorial as Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations ( he, חֲסִידֵי אֻמּוֹת הָעוֹלָם, ; "righteous (plural) of the world's nations") is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to sav ...

.

* In 1973, an elite sports school bearing the Poelchau name, the ''Poelchau-Oberschule'' was opened in the Charlottenburg-Nord

Charlottenburg-Nord (, literally "Charlottenburg North") is a locality (''Ortsteil'') in the northern part of the Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf borough of Berlin, Germany. It is chiefly composed of after-war housing estates, allotment gardens and comm ...

district of Berlin.

* By resolution of the Senate of Berlin

The Senate of Berlin (german: Berliner Senat) is the executive body governing the city of Berlin, which at the same time is a States of Germany, state of Germany. According to the the Senate consists of the Governing Mayor of Berlin and up to t ...

on 6 October 1987, the couples burial place at the Zehlendorf cemetery was converted into an honorary grave of the State of Berlin.

* On 17 November 1988, a Berlin memorial plaque was affixed to the house at Afrikanische Straße 140b in Wedding

A wedding is a ceremony where two people are united in marriage. Wedding traditions and customs vary greatly between cultures, ethnic groups, religions, countries, and social classes. Most wedding ceremonies involve an exchange of marriage vo ...

in Berlin, where the couple lived from 1933 to 1946.

* On 31 January 1992, Karl-Maron-Straße in the Marzahn

Marzahn () is a locality within the borough of Marzahn-Hellersdorf in Berlin. Berlin's 2001 administrative reform led to the former boroughs of Marzahn and Hellersdorf fusing into a single new borough. In the north the Marzahn locality inclu ...

district of Berlin, was given the name Poelchaustraße, as was the Berlin S-Bahn

The Berlin S-Bahn () is a rapid transit railway system in and around Berlin, the capital city of Germany. It has been in operation under this name since December 1930, having been previously called the special tariff area ''Berliner Stadt-, Ring ...

station named after the street.

* On 29 April 1992, an asteroid discovered by Freimut Börngen

Freimut Börngen (; 17 October 1930 – 19 June 2021) was a German astronomer and a prolific discoverer of minor planets. A few sources give his first name wrongly as "Freimuth". The Minor Planet Center credits him as F. Borngen.

He studied ga ...

at the Karl Schwarzschild Observatory

The Karl Schwarzschild Observatory (german: Karl-Schwarzschild-Observatorium) is a German astronomical observatory in Tautenburg near Jena, Thuringia.

It was founded in 1960 as an affiliated institute of the former German Academy of Sciences at ...

was named ''Poelchau'' (10348) in honour of the couple.

* On 18 September 2017, a memorial stele

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ''stelæ''), whe ...

for Harald and Dorothee Poelchau was dedicated at the corner of Poelchaustraße, Märkische Allee in the Marzahn

Marzahn () is a locality within the borough of Marzahn-Hellersdorf in Berlin. Berlin's 2001 administrative reform led to the former boroughs of Marzahn and Hellersdorf fusing into a single new borough. In the north the Marzahn locality inclu ...

district of Berlin.

* On 5 October 2018, a memorial created by the artist Katrin Hattenhauer and the inmates of Tegel Prison

Tegel Prison is a penal facility in the borough of Reinickendorf in the north of the German state of Berlin. The prison is one of the Germany's largest prisons.

Structure and numbers

Tegel Prison is a closed prison. It is currently divided into ...

on the prison walls, was inaugurated for Harald Poelchau.

Bibliography

* * *Literature

* * * * * * * * * * * *References

External links

Memorial - Harald Poelchau - Berlin - Justizvollzugsanstalt Tegel

{{DEFAULTSORT:Poelchau, Harald 1903 births 1972 deaths People from Potsdam German Righteous Among the Nations Protestants in the German Resistance University of Tübingen alumni University of Marburg alumni Prison chaplains German resistance members Protestant anti-fascists