Hara-kiri on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, sometimes referred to as hara-kiri (, , a native Japanese kun reading), is a form of Japanese ritual

, sometimes referred to as hara-kiri (, , a native Japanese kun reading), is a form of Japanese ritual

The term ''seppuku'' is derived from the two Sino-Japanese roots ''setsu'' ("to cut", from

The term ''seppuku'' is derived from the two Sino-Japanese roots ''setsu'' ("to cut", from

The practice was not standardized until the 17th century. In the 12th and 13th centuries, such as with the ''seppuku'' of Minamoto no Yorimasa, the practice of a '' kaishakunin'' (idiomatically, his "second") had not yet emerged, thus the rite was considered far more painful. The defining characteristic was plunging either the ''

The practice was not standardized until the 17th century. In the 12th and 13th centuries, such as with the ''seppuku'' of Minamoto no Yorimasa, the practice of a '' kaishakunin'' (idiomatically, his "second") had not yet emerged, thus the rite was considered far more painful. The defining characteristic was plunging either the '' With his selected ''kaishakunin'' standing by, he would open his kimono, take up his ''

With his selected ''kaishakunin'' standing by, he would open his kimono, take up his ''

On February 15, 1868, eleven French sailors of the '' Dupleix'' entered the town of Sakai without official permission. Their presence caused panic among the residents. Security forces were dispatched to turn the sailors back to their ship, but a fight broke out and the sailors were shot dead. Upon the protest of the French representative, financial compensation was paid, and those responsible were sentenced to death. Captain Abel-Nicolas Bergasse du Petit-Thouars was present to observe the execution. As each samurai committed ritual disembowelment, the violent act shocked the captain, and he requested a pardon, as a result of which nine of the samurai were spared. This incident was dramatized in a famous short story, "Sakai Jiken", by

On February 15, 1868, eleven French sailors of the '' Dupleix'' entered the town of Sakai without official permission. Their presence caused panic among the residents. Security forces were dispatched to turn the sailors back to their ship, but a fight broke out and the sailors were shot dead. Upon the protest of the French representative, financial compensation was paid, and those responsible were sentenced to death. Captain Abel-Nicolas Bergasse du Petit-Thouars was present to observe the execution. As each samurai committed ritual disembowelment, the violent act shocked the captain, and he requested a pardon, as a result of which nine of the samurai were spared. This incident was dramatized in a famous short story, "Sakai Jiken", by  During the

During the

In 1970, author

In 1970, author

The expected honor-suicide of the samurai wife is frequently referenced in Japanese literature and film, such as in ''Taiko'' by Eiji Yoshikawa, '' Humanity and Paper Balloons'', and ''

The expected honor-suicide of the samurai wife is frequently referenced in Japanese literature and film, such as in ''Taiko'' by Eiji Yoshikawa, '' Humanity and Paper Balloons'', and ''

Seppuku

– A Practical Guide (tongue-in-cheek) * * *

Zuihoden

– The mausoleum of

Seppuku and "cruel punishments" at the end of Tokugawa Shogunate

From the Buke Sho Hatto (1663) – :"That the custom of following a master in death is wrong and unprofitable is a caution which has been at times given of old; but, owing to the fact that it has not actually been prohibited, the number of those who cut their belly to follow their lord on his decease has become very great. For the future, to those retainers who may be animated by such an idea, their respective lords should intimate, constantly and in very strong terms, their disapproval of the custom. If, notwithstanding this warning, any instance of the practice should occur, it will be deemed that the deceased lord was to blame for unreadiness. Henceforward, moreover, his son and successor will be held to be blameworthy for incompetence, as not having prevented the suicides." *

, sometimes referred to as hara-kiri (, , a native Japanese kun reading), is a form of Japanese ritual

, sometimes referred to as hara-kiri (, , a native Japanese kun reading), is a form of Japanese ritual suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

by disembowelment

Disembowelment or evisceration is the removal of some or all of the organs of the gastrointestinal tract (the bowels, or viscera), usually through a horizontal incision made across the abdominal area. Disembowelment may result from an accide ...

. It was originally reserved for samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of History of Japan#Medieval Japan (1185–1573/1600), medieval and Edo period, early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retai ...

in their code of honour but was also practised by other Japanese people during the Shōwa period

Shōwa may refer to:

* Hirohito (1901–1989), the 124th Emperor of Japan, known posthumously as Emperor Shōwa

* Showa Corporation, a Japanese suspension and shock manufacturer, affiliated with the Honda keiretsu

Japanese eras

* Jōwa (Heian ...

(particularly officers near the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

) to restore honour for themselves or for their families. As a samurai practice, ''seppuku'' was used voluntarily by samurai to die with honour rather than fall into the hands of their enemies (and likely be tortured), as a form of capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

for samurai who had committed serious offences, or performed because they had brought shame to themselves. The ceremonial disembowelment, which is usually part of a more elaborate ritual and performed in front of spectators, consists of plunging a short blade, traditionally a ''tantō

A is one of the traditionally made Japanese swords ( ''nihonto'') that were worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. The tantō dates to the Heian period, when it was mainly used as a weapon but evolved in design over the years to become more ...

'', into the belly and drawing the blade from left to right, slicing the belly open. If the cut is deep enough, it can sever the abdominal aorta

In human anatomy, the abdominal aorta is the largest artery in the abdominal cavity. As part of the aorta, it is a direct continuation of the descending aorta (of the thorax).

Structure

The abdominal aorta begins at the level of the diaphragm ...

, causing a rapid death by blood loss.

The first recorded act of ''seppuku'' was performed by Minamoto no Yorimasa

(1106 – 20 June 1180) was a prominent Japanese poet whose works appeared in various anthologies. He served eight different emperors in his long career, holding posts such as ''hyōgo no kami'' (head of the arsenal). He was also a warrior, le ...

during the Battle of Uji in 1180. ''Seppuku'' was used by warriors to avoid falling into enemy hands and to attenuate shame and avoid possible torture. Samurai could also be ordered by their ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast, hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and nominall ...

'' ( feudal lords) to carry out ''seppuku''. Later, disgraced warriors were sometimes allowed to carry out ''seppuku'' rather than be executed in the normal manner. The most common form of ''seppuku'' for men was composed of the cutting of the abdomen, and when the samurai was finished, he stretched out his neck for an assistant to sever his spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue, which extends from the medulla oblongata in the brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone). The backbone encloses the central canal of the spin ...

. It was the assistant's job to decapitate the samurai in one swing, otherwise it would bring great shame to the assistant and his family. Those who did not belong to the samurai caste were never ordered or expected to carry out ''seppuku''. Samurai generally could carry out the act only with permission.

Sometimes a ''daimyō'' was called upon to perform ''seppuku'' as the basis of a peace agreement. This weakened the defeated clan so that resistance effectively ceased. Toyotomi Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and '' daimyō'' ( feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: Military Innovations that Changed the C ...

used an enemy's suicide in this way on several occasions, the most dramatic of which effectively ended a dynasty of ''daimyōs''. When the Hōjō Clan

The was a Japanese samurai family who controlled the hereditary title of ''shikken'' (regent) of the Kamakura shogunate between 1203 and 1333. Despite the title, in practice the family wielded actual political power in Japan during this period ...

were defeated at Odawara in 1590, Hideyoshi insisted on the suicide of the retired ''daimyō'' Hōjō Ujimasa

was the fourth head of the later Hōjō clan, and ''daimyō'' of Odawara. Ujimasa succeeded the territory expansion policy from his father, Hojo Ujiyasu, and achieved the biggest territory in the clan's history.

Early life and rise

In 1538, ...

and the exile of his son Ujinao; with this act of suicide, the most powerful ''daimyō'' family in eastern Japan was completely defeated.

Etymology

The term ''seppuku'' is derived from the two Sino-Japanese roots ''setsu'' ("to cut", from

The term ''seppuku'' is derived from the two Sino-Japanese roots ''setsu'' ("to cut", from Middle Chinese

Middle Chinese (formerly known as Ancient Chinese) or the Qieyun system (QYS) is the historical variety of Chinese recorded in the ''Qieyun'', a rime dictionary first published in 601 and followed by several revised and expanded editions. The ...

''tset''; compare Mandarin

Mandarin or The Mandarin may refer to:

Language

* Mandarin Chinese, branch of Chinese originally spoken in northern parts of the country

** Standard Chinese or Modern Standard Mandarin, the official language of China

** Taiwanese Mandarin, Stand ...

''qiē'' and Cantonese

Cantonese ( zh, t=廣東話, s=广东话, first=t, cy=Gwóngdūng wá) is a language within the Chinese (Sinitic) branch of the Sino-Tibetan languages originating from the city of Guangzhou (historically known as Canton) and its surrounding ar ...

''chit'') and ''fuku'' ("belly", from MC ''pjuwk''; compare Mandarin ''fù'' and Cantonese ''fūk'').

It is also known as ''harakiri'' (, "cutting the stomach"; often misspelled/mispronounced "hiri-kiri" or "hari-kari" by American English speakers). ''Harakiri'' is written with the same kanji as ''seppuku'' but in reverse order with an okurigana

are kana suffixes following kanji stems in Japanese written words. They serve two purposes: to inflect adjectives and verbs, and to force a particular kanji to have a specific meaning and be read a certain way. For example, the plain verb f ...

. In Japanese, the more formal ''seppuku'', a Chinese ''on'yomi

are the logographic Chinese characters taken from the Chinese script and used in the writing of Japanese. They were made a major part of the Japanese writing system during the time of Old Japanese and are still used, along with the subseq ...

'' reading, is typically used in writing, while ''harakiri'', a native ''kun'yomi

are the logographic Chinese characters taken from the Chinese script and used in the writing of Japanese. They were made a major part of the Japanese writing system during the time of Old Japanese and are still used, along with the subseq ...

'' reading, is used in speech. As Ross notes,

It is commonly pointed out that hara-kiri is aThe practice of performing ''seppuku'' at the death of one's master, known as ''oibara'' (追腹 or 追い腹, the kun'yomi or Japanese reading) or ''tsuifuku'' (追腹, the on'yomi or Chinese reading), follows a similar ritual. The word means "suicide" in Japanese. The modern word for suicide is . In some popular western texts, such as martial arts magazines, the term is associated with suicide of samurai wives. The term was introduced into English byvulgarism In the study of language and literary style, a vulgarism is an expression or usage considered non-standard or characteristic of uneducated speech or writing. In colloquial or lexical English, "vulgarism" or "vulgarity" may be synonymous with pro ..., but this is a misunderstanding. Hara-kiri is a Japanese reading or ''Kun-yomi'' of the characters; as it became customary to prefer Chinese readings in official announcements, only the term seppuku was ever used in writing. So hara-kiri is a spoken term, but only to commoners and seppuku a written term, but spoken amongst higher classes for the same act.

Lafcadio Hearn

, born Patrick Lafcadio Hearn (; el, Πατρίκιος Λευκάδιος Χέρν, Patríkios Lefkádios Chérn, Irish: Pádraig Lafcadio O'hEarain), was an Irish-Greek- Japanese writer, translator, and teacher who introduced the culture an ...

in his ''Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation'', an understanding which has since been translated into Japanese. Joshua S. Mostow notes that Hearn misunderstood the term ''jigai'' to be the female equivalent of seppuku.

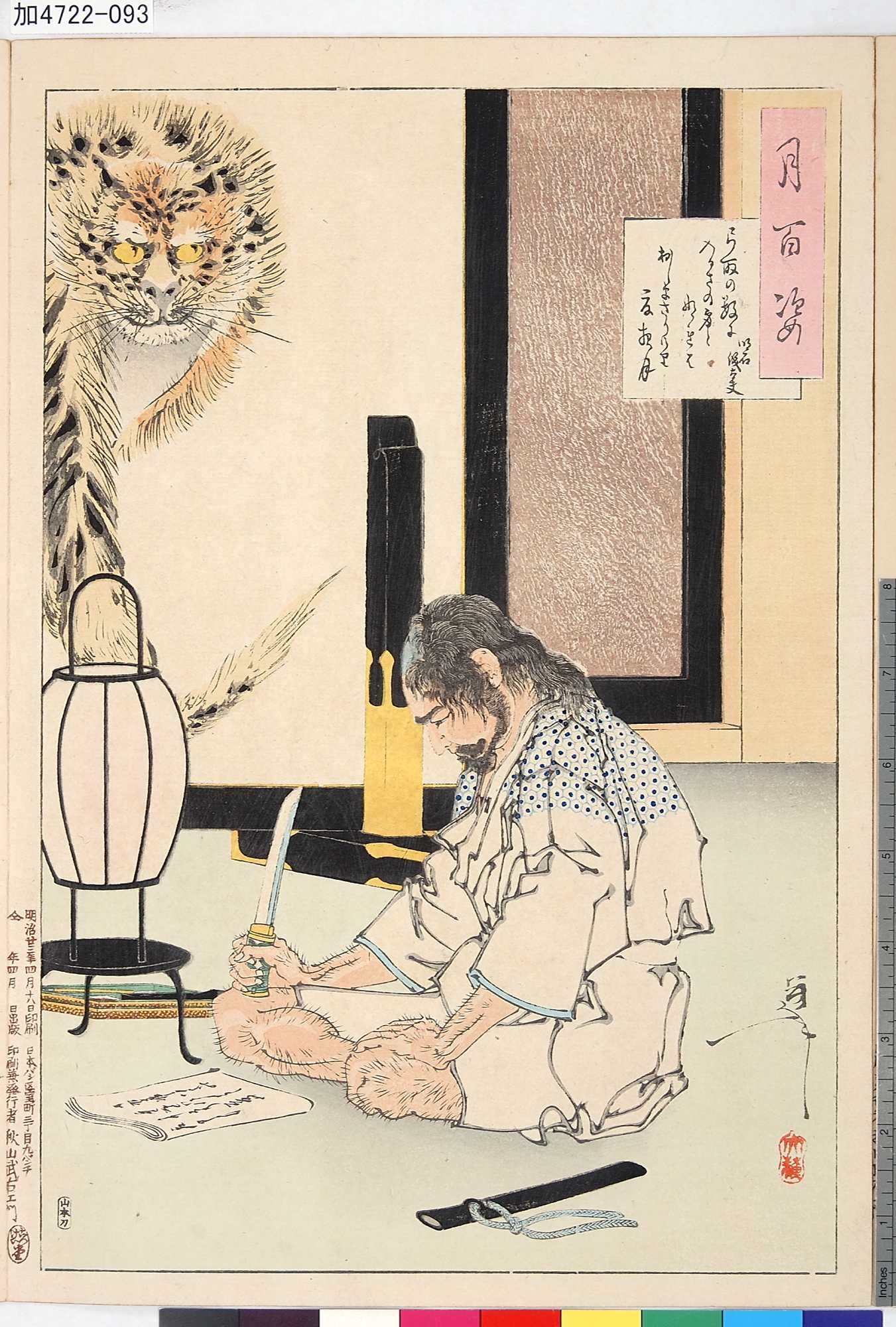

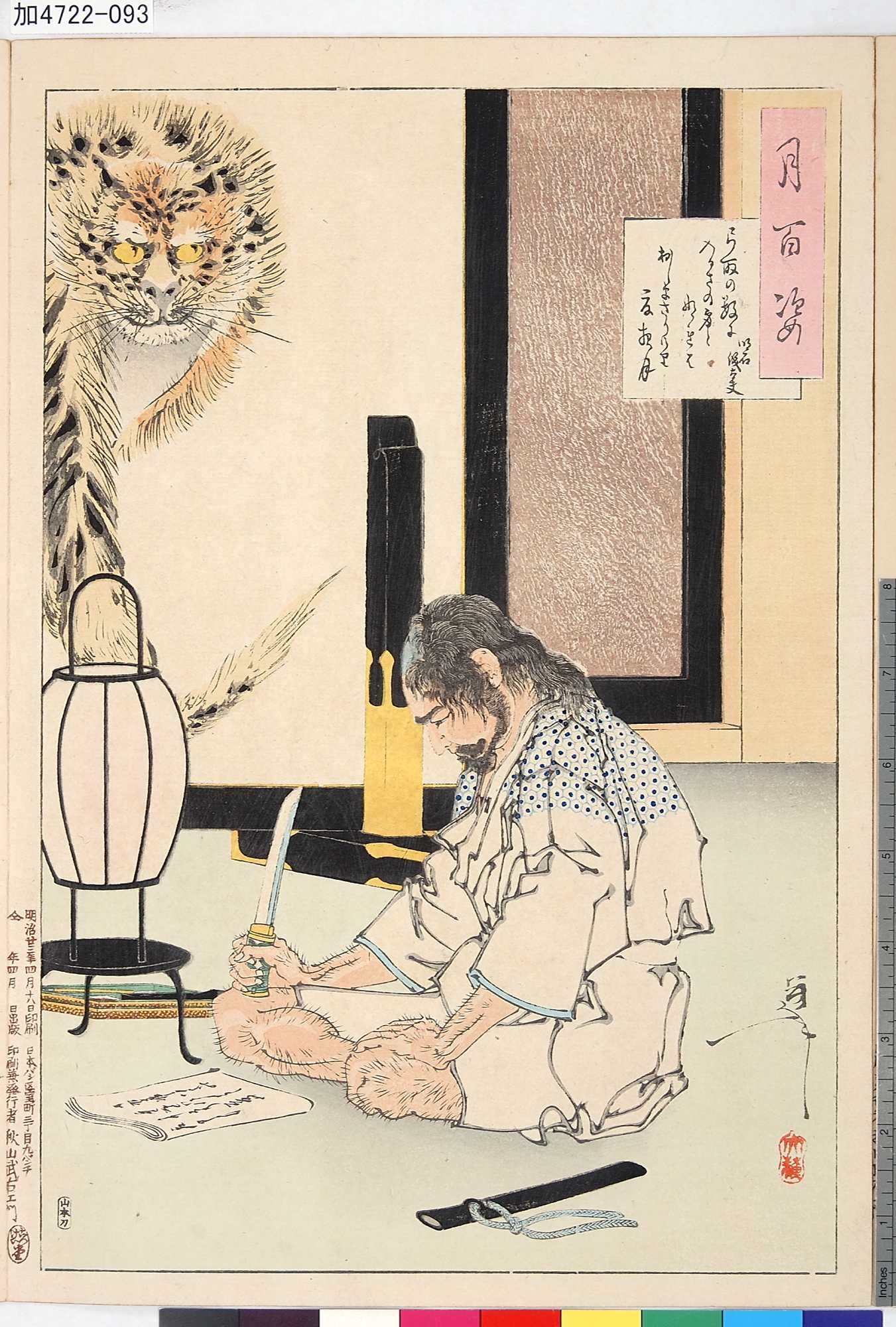

Ritual

The practice was not standardized until the 17th century. In the 12th and 13th centuries, such as with the ''seppuku'' of Minamoto no Yorimasa, the practice of a '' kaishakunin'' (idiomatically, his "second") had not yet emerged, thus the rite was considered far more painful. The defining characteristic was plunging either the ''

The practice was not standardized until the 17th century. In the 12th and 13th centuries, such as with the ''seppuku'' of Minamoto no Yorimasa, the practice of a '' kaishakunin'' (idiomatically, his "second") had not yet emerged, thus the rite was considered far more painful. The defining characteristic was plunging either the ''tachi

A is a type of traditionally made Japanese sword (''nihonto'') worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. ''Tachi'' and '' katana'' generally differ in length, degree of curvature, and how they were worn when sheathed, the latter depending o ...

'' (longsword), ''wakizashi

The is one of the traditionally made Japanese swords ('' nihontō'') worn by the samurai in feudal Japan.

History and use

The production of swords in Japan is divided into specific time periods:

'' (shortsword) or ''tantō'' (knife) into the gut and slicing the abdomen horizontally. In the absence of a ''kaishakunin'', the samurai would then remove the blade and stab himself in the throat, or fall (from a standing position) with the blade positioned against his heart.

During the Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional ''daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was character ...

(1600–1867), carrying out ''seppuku'' came to involve an elaborate, detailed ritual. This was usually performed in front of spectators if it was a planned ''seppuku'', as opposed to one performed on a battlefield. A samurai was bathed in cold water (to prevent excessive bleeding), dressed in a white kimono

The is a traditional Japanese garment and the national dress of Japan. The kimono is a wrapped-front garment with square sleeves and a rectangular body, and is worn left side wrapped over right, unless the wearer is deceased. The kimon ...

called the and served his favorite foods for a last meal. When he had finished, the knife and cloth were placed on another ''sanbo'' and given to the warrior. Dressed ceremonially, with his sword placed in front of him and sometimes seated on special clothes, the warrior would prepare for death by writing a death poem

The death poem is a genre of poetry that developed in the literary traditions of East Asian cultures—most prominently in Japan as well as certain periods of Chinese history and Joseon Korea. They tend to offer a reflection on death—both in ...

. He would probably consume an important ceremonial drink of sake

Sake, also spelled saké ( ; also referred to as Japanese rice wine), is an alcoholic beverage of Japanese origin made by fermenting rice that has been polished to remove the bran. Despite the name ''Japanese rice wine'', sake, and ind ...

. He would also give his attendant a cup meant for sake.

With his selected ''kaishakunin'' standing by, he would open his kimono, take up his ''

With his selected ''kaishakunin'' standing by, he would open his kimono, take up his ''tantō

A is one of the traditionally made Japanese swords ( ''nihonto'') that were worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. The tantō dates to the Heian period, when it was mainly used as a weapon but evolved in design over the years to become more ...

''which the samurai held by the blade with a cloth wrapped around so that it would not cut his hand and cause him to lose his gripand plunge it into his abdomen, making a left-to-right cut. The ''kaishakunin'' would then perform ''kaishaku,'' a cut in which the warrior was partially decapitated. The maneuver should be done in the manners of ''dakikubi'' (lit. "embraced head"), in which way a slight band of flesh is left attaching the head to the body, so that it can be hung in front as if embraced. Because of the precision necessary for such a maneuver, the second was a skilled swordsman. The principal and the ''kaishakunin'' agreed in advance when the latter was to make his cut. Usually ''dakikubi'' would occur as soon as the dagger was plunged into the abdomen. Over time, the process became so highly ritualized that as soon as the samurai reached for his blade the ''kaishakunin'' would strike. Eventually even the blade became unnecessary and the samurai could reach for something symbolic like a fan, and this would trigger the killing stroke from his second. The fan was likely used when the samurai was too old to use the blade or in situations where it was too dangerous to give him a weapon.

This elaborate ritual evolved after ''seppuku'' had ceased being mainly a battlefield or wartime practice and became a para-judicial institution. The second was usually, but not always, a friend. If a defeated warrior had fought honorably and well, an opponent who wanted to salute his bravery would volunteer to act as his second.

In the ''Hagakure

''Hagakure'' (Kyūjitai: ; Shinjitai: ; meaning ''Hidden by the Leaves'' or ''Hidden Leaves''), or , is a practical and spiritual guide for a warrior, drawn from a collection of commentaries by the clerk Yamamoto Tsunetomo, former retainer to Na ...

,'' Yamamoto Tsunetomo

, Buddhist monastic name Yamamoto Jōchō (June 11, 1659 – November 30, 1719), was a samurai of the Saga Domain in Hizen Province under his lord Nabeshima Mitsushige. He became a Zen Buddhist priest and relayed his experiences, memories ...

wrote:

A specialized form of ''seppuku'' in feudal times was known as ''kanshi'' (諫死, "remonstration death/death of understanding"), in which a retainer would commit suicide in protest of a lord's decision. The retainer would make one deep, horizontal cut into his abdomen, then quickly bandage the wound. After this, the person would then appear before his lord, give a speech in which he announced the protest of the lord's action, then reveal his mortal wound. This is not to be confused with ''funshi'' (憤死, indignation death), which is any suicide made to protest or state dissatisfaction.

Some samurai chose to perform a considerably more taxing form of ''seppuku'' known as ''jūmonji giri'' (十文字切り, "cross-shaped cut"), in which there is no ''kaishakunin'' to put a quick end to the samurai's suffering. It involves a second and more painful vertical cut on the belly. A samurai performing ''jūmonji giri'' was expected to bear his suffering quietly until he bled to death, passing away with his hands over his face.

Female ritual suicide

Female ritual suicide (incorrectly referred to in some English sources as jiigai), was practiced by the wives of samurai who have performed ''seppuku'' or brought dishonor. Some women belonging to samurai families committed suicide by cutting the arteries of the neck with one stroke, using a knife such as a ''tantō'' or '' kaiken''. The main purpose was to achieve a quick and certain death in order to avoid capture. Before committing suicide, a woman would often tie her knees together so her body would be found in a “dignified” pose, despite the convulsions of death. Invading armies would often enter homes to find the lady of the house seated alone, facing away from the door. On approaching her, they would find that she had ended her life long before they reached her.

History

Stephen R. Turnbull provides extensive evidence for the practice of female ritual suicide, notably of samurai wives, in pre-modern Japan. One of the largest mass suicides was the 25 April 1185 final defeat of Taira no Tomomori. The wife of Onodera Junai, one of theForty-seven Ronin

47 (forty-seven) is the natural number following 46 and preceding 48. It is a prime number.

In mathematics

Forty-seven is the fifteenth prime number, a safe prime, the thirteenth supersingular prime, the fourth isolated prime, and the sixth ...

, is a notable example of a wife following ''seppuku'' of a samurai husband. A large number of honor suicides marked the defeat of the Aizu clan in the Boshin War of 1869, leading into the Meiji era

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization ...

. For example, in the family of Saigō Tanomo, who survived, a total of twenty-two female honor suicides are recorded among one extended family.

Religious and social context

Voluntary death by drowning was a common form of ritual or honor suicide. The religious context of thirty-threeJōdo Shinshū

, also known as Shin Buddhism or True Pure Land Buddhism, is a school of Pure Land Buddhism. It was founded by the former Tendai Japanese monk Shinran.

Shin Buddhism is the most widely practiced branch of Buddhism in Japan.

History

Shinran ...

adherents at the funeral of Abbot Jitsunyo in 1525 was faith in Amida Buddha Amida can mean :

Places and jurisdictions

* Amida (Mesopotamia), now Diyarbakır, an ancient city in Asian Turkey; it is (nominal) seat of :

** The Chaldean Catholic Archeparchy of Amida

** The Latin titular Metropolitan see of Amida of the Roma ...

and belief in rebirth in his Pure land

A pure land is the celestial realm of a buddha or bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism. The term "pure land" is particular to East Asian Buddhism () and related traditions; in Sanskrit the equivalent concept is called a buddha-field (Sanskrit ). T ...

, but male ''seppuku'' did not have a specifically religious context. By way of contrast, the religious beliefs of Hosokawa Gracia

Akechi Tama, usually referred to as , (1563 – 25 August 1600) was a member of the aristocratic Akechi family from the Sengoku period. Gracia is best known for her role in the Battle of Sekigahara, she was considered to be a political host ...

, the Christian wife of ''daimyō'' Hosokawa Tadaoki

was a Japanese samurai warrior of the late Sengoku period and early Edo period. He was the son of Hosokawa Fujitaka with Numata Jakō, and he was the husband of a famous Christian convert (Kirishitan), Hosokawa Gracia. For most of his life, ...

, prevented her from committing suicide.

Terminology

The word means "suicide" in Japanese. The usual modern word for suicide is . Related words include , and . In some popular western texts, such as martial arts magazines, the term is associated with suicide of samurai wives. The term was introduced into English byLafcadio Hearn

, born Patrick Lafcadio Hearn (; el, Πατρίκιος Λευκάδιος Χέρν, Patríkios Lefkádios Chérn, Irish: Pádraig Lafcadio O'hEarain), was an Irish-Greek- Japanese writer, translator, and teacher who introduced the culture an ...

in his ''Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation'', an understanding which has since been translated into Japanese and Hearn seen through Japanese eyes. Joshua S. Mostow notes that Hearn misunderstood the term ''jigai'' to be the female equivalent of ''seppuku''. Mostow's context is analysis of Giacomo Puccini

Giacomo Puccini (Lucca, 22 December 1858Bruxelles, 29 November 1924) was an Italian composer known primarily for his operas. Regarded as the greatest and most successful proponent of Italian opera after Verdi, he was descended from a long l ...

's ''Madame Butterfly

''Madama Butterfly'' (; ''Madame Butterfly'') is an opera in three acts (originally two) by Giacomo Puccini, with an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa.

It is based on the short story " Madame Butterfly" (1898) by John Lu ...

'' and the original Cio-Cio San story by John Luther Long. Though both Long's story and Puccini's opera predate Hearn's use of the term ''jigai'', the term has been used in relation to western Japonisme

''Japonisme'' is a French term that refers to the popularity and influence of Japanese art and design among a number of Western European artists in the nineteenth century following the forced reopening of foreign trade with Japan in 1858. Japo ...

, which is the influence of Japanese culture on the western arts.

As capital punishment

While the voluntary ''seppuku'' is the best known form, in practice the most common form of ''seppuku'' was obligatory ''seppuku'', used as a form ofcapital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

for disgraced samurai, especially for those who committed a serious offense such as rape, robbery, corruption, unprovoked murder or treason. The samurai were generally told of their offense in full and given a set time for them to commit ''seppuku'', usually before sunset on a given day. On occasion, if the sentenced individuals were uncooperative, ''seppuku'' could be carried out by an executioner, or more often, the actual execution was carried out solely by decapitation while retaining only the trappings of ''seppuku''; even the ''tantō'' laid out in front of the uncooperative offender could be replaced with a fan (to prevent the uncooperative offenders from using the ''tantō'' as a weapon against the observers or the executioner). This form of involuntary ''seppuku'' was considered shameful and undignified. Unlike voluntary ''seppuku'', ''seppuku'' carried out as capital punishment by executioners did not necessarily absolve, or pardon, the offender's family of the crime. Depending on the severity of the crime, all or part of the property of the condemned could be confiscated, and the family would be punished by being stripped of rank, sold into long-term servitude, or executed.

''Seppuku'' was considered the most honorable capital punishment apportioned to samurai. ''Zanshu'' (斬首) and s''arashikubi'' (晒し首), decapitation followed by a display of the head, was considered harsher and was reserved for samurai who committed greater crimes. Harshest punishments, usually involving death by torturous methods like ''kamayude'' (釜茹で), death by boiling, were reserved for commoner offenders.

Forced ''seppuku'' came to be known as "conferred death" over time as it was used for punishment of criminal samurai.

Recorded events

On February 15, 1868, eleven French sailors of the '' Dupleix'' entered the town of Sakai without official permission. Their presence caused panic among the residents. Security forces were dispatched to turn the sailors back to their ship, but a fight broke out and the sailors were shot dead. Upon the protest of the French representative, financial compensation was paid, and those responsible were sentenced to death. Captain Abel-Nicolas Bergasse du Petit-Thouars was present to observe the execution. As each samurai committed ritual disembowelment, the violent act shocked the captain, and he requested a pardon, as a result of which nine of the samurai were spared. This incident was dramatized in a famous short story, "Sakai Jiken", by

On February 15, 1868, eleven French sailors of the '' Dupleix'' entered the town of Sakai without official permission. Their presence caused panic among the residents. Security forces were dispatched to turn the sailors back to their ship, but a fight broke out and the sailors were shot dead. Upon the protest of the French representative, financial compensation was paid, and those responsible were sentenced to death. Captain Abel-Nicolas Bergasse du Petit-Thouars was present to observe the execution. As each samurai committed ritual disembowelment, the violent act shocked the captain, and he requested a pardon, as a result of which nine of the samurai were spared. This incident was dramatized in a famous short story, "Sakai Jiken", by Mori Ōgai

Lieutenant-General , known by his pen name , was a Japanese Army Surgeon general officer, translator, novelist, poet and father of famed author Mari Mori. He obtained his medical license at a very young age and introduced translated German la ...

.

In the 1860s, the British Ambassador to Japan, Algernon Freeman-Mitford (Lord Redesdale), lived within sight of Sengaku-ji where the Forty-seven Ronin are buried. In his book ''Tales of Old Japan'', he describes a man who had come to the graves to kill himself:

Mitford also describes his friend's eyewitness account of a ''seppuku'':

During the

During the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were r ...

, the Tokugawa shogun's aide performed seppuku:

In his book ''Tales of Old Japan'', Mitford describes witnessing a hara-kiri:

As a corollary to the above elaborate statement of the ceremonies proper to be observed at the harakiri, I may here describe an instance of such an execution which I was sent officially to witness. The condemned man was Taki Zenzaburo, an officer of the Prince of Bizen, who gave the order to fire upon the foreign settlement at Hyōgo in the month of February 1868,anattack Attack may refer to: Warfare and combat * Offensive (military) * Charge (warfare) * Attack (fencing) * Strike (attack) * Attack (computing) * Attack aircraft Books and publishing * ''The Attack'' (novel), a book * '' Attack No. 1'', comic an ...to which I have alluded in the preamble to the story of the Eta Maiden and theHatamoto A was a high ranking samurai in the direct service of the Tokugawa shogunate of feudal Japan. While all three of the shogunates in Japanese history had official retainers, in the two preceding ones, they were referred to as ''gokenin.'' Howev .... Up to that time no foreigner had witnessed such an execution, which was rather looked upon as a traveler's fable. The ceremony, which was ordered by theMikado Mikado may refer to: * Emperor of Japan or Arts and entertainment * '' The Mikado'', an 1885 comic opera by Gilbert and Sullivan * ''The Mikado'' (1939 film), an adaptation of the opera, directed by Victor Schertzinger * ''The Mikado'' (1967 ...(Emperor) himself, took place at 10:30 at night in the temple of Seifukuji, the headquarters of the Satsuma troops at Hiogo. A witness was sent from each of the foreign legations. We were seven foreigners in all. After another profound obeisance, Taki Zenzaburo, in a voice which betrayed just so much emotion and hesitation as might be expected from a man who is making a painful confession, but with no sign of either in his face or manner, spoke as follows: Bowing once more, the speaker allowed his upper garments to slip down to his girdle, and remained naked to the waist. Carefully, according to custom, he tucked his sleeves under his knees to prevent himself from falling backwards; for a noble Japanese gentleman should die falling forwards. Deliberately, with a steady hand, he took the dirk that lay before him; he looked at it wistfully, almost affectionately; for a moment he seemed to collect his thoughts for the last time, and then stabbing himself deeply below the waist on the left-hand side, he drew the dirk slowly across to the right side, and, turning it in the wound, gave a slight cut upwards. During this sickeningly painful operation he never moved a muscle of his face. When he drew out the dirk, he leaned forward and stretched out his neck; an expression of pain for the first time crossed his face, but he uttered no sound. At that moment the ''kaishaku'', who, still crouching by his side, had been keenly watching his every movement, sprang to his feet, poised his sword for a second in the air; there was a flash, a heavy, ugly thud, a crashing fall; with one blow the head had been severed from the body. A dead silence followed, broken only by the hideous noise of the blood throbbing out of the inert heap before us, which but a moment before had been a brave and chivalrous man. It was horrible. The ''kaishaku'' made a low bow, wiped his sword with a piece of rice paper which he had ready for the purpose, and retired from the raised floor; and the stained dirk was solemnly borne away, a bloody proof of the execution. The two representatives of the Mikado then left their places, and, crossing over to where the foreign witnesses sat, called us to witness that the sentence of death upon Taki Zenzaburo had been faithfully carried out. The ceremony being at an end, we left the temple. The ceremony, to which the place and the hour gave an additional solemnity, was characterized throughout by that extreme dignity and punctiliousness which are the distinctive marks of the proceedings of Japanese gentlemen of rank; and it is important to note this fact, because it carries with it the conviction that the dead man was indeed the officer who had committed the crime, and no substitute. While profoundly impressed by the terrible scene it was impossible at the same time not to be filled with admiration of the firm and manly bearing of the sufferer, and of the nerve with which the ''kaishaku'' performed his last duty to his master.

In modern Japan

''Seppuku'' as judicial punishment was abolished in 1873, shortly after theMeiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were r ...

, but voluntary ''seppuku'' did not completely die out. Dozens of people are known to have committed ''seppuku'' since then, including General Nogi and his wife on the death of Emperor Meiji

, also called or , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession. Reigning from 13 February 1867 to his death, he was the first monarch of the Empire of Japan and presided over the Meiji era. He was the figur ...

in 1912, and numerous soldiers and civilians who chose to die rather than surrender at the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. The practice had been widely praised in army propaganda, which featured a soldier captured by the Chinese in the Shanghai Incident (1932) who returned to the site of his capture to perform ''seppuku''. In 1944, Hideyoshi Obata, a Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

in the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor ...

, committed ''seppuku'' in Yigo, Guam, following the Allied victory over the Japanese in the Second Battle of Guam. Obata was posthumously promoted to the rank of general. Many other high-ranking military officials of Imperial Japan would go on to commit ''seppuku'' toward the latter half of World War II in 1944 and 1945, as the tide of the war turned against the Japanese, and it became clear that a Japanese victory of the war was not achievable.

In 1970, author

In 1970, author Yukio Mishima

, born , was a Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor, model, Shintoist, nationalist, and founder of the , an unarmed civilian militia. Mishima is considered one of the most important Japanese authors of the 20th century. He was considered fo ...

and one of his followers performed public ''seppuku'' at the Japan Self-Defense Forces

The Japan Self-Defense Forces ( ja, 自衛隊, Jieitai; abbreviated JSDF), also informally known as the Japanese Armed Forces, are the unified ''de facto''Since Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution outlaws the formation of Military, armed f ...

headquarters following an unsuccessful attempt to incite the armed forces to stage a ''coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, ...

''. Mishima performed ''seppuku'' in the office of General Kanetoshi Mashita. His second, a 25-year-old man named Masakatsu Morita, tried three times to ritually behead Mishima but failed, and his head was finally severed by Hiroyasu Koga, a former kendo

is a modern Japanese martial art, descended from kenjutsu (one of the old Japanese martial arts, swordsmanship), that uses bamboo swords ( shinai) as well as protective armor ( bōgu). Today, it is widely practiced within Japan and has spr ...

champion. Morita then attempted to perform ''seppuku'' himself, but when his own cuts were too shallow to be fatal, he gave the signal and was beheaded by Koga.

Notable cases

List of notable ''seppuku'' cases in chronological order. * Minamoto no Tametomo (1170) *Minamoto no Yorimasa

(1106 – 20 June 1180) was a prominent Japanese poet whose works appeared in various anthologies. He served eight different emperors in his long career, holding posts such as ''hyōgo no kami'' (head of the arsenal). He was also a warrior, le ...

(1180)

* Minamoto no Yoshitsune

was a military commander of the Minamoto clan of Japan in the late Heian and early Kamakura periods. During the Genpei War, he led a series of battles which toppled the Ise-Heishi branch of the Taira clan, helping his half-brother Yoritomo cons ...

(1189)

* Hōjō Takatoki

was the last '' Tokusō'' and ruling Shikken (regent) of Japan's Kamakura shogunate; the rulers that followed were his puppets. A member of the Hōjō clan, he was the son of Hōjō Sadatoki, and was preceded as ''shikken'' by Hōjō Morotoki.

...

(1333)

* Ashikaga Mochiuji

Ashikaga Mochiuji (, 1398–1439) was the Kamakura-fu's fourth Kantō kubō during the Sengoku period (15th century) in Japan. During his long and troubled rule the relationship between the west and the east of the country reached an all-time lo ...

(1439)

* Azai Nagamasa

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' of the Sengoku period known as the brother-in-law and enemy of Oda Nobunaga. Nagamasa was head of the Azai clan seated at Odani Castle in northern Ōmi Province and married Nobunaga's sister Oichi in 1564, fathering ...

(1573)

* Oda Nobunaga

was a Japanese '' daimyō'' and one of the leading figures of the Sengoku period. He is regarded as the first "Great Unifier" of Japan.

Nobunaga was head of the very powerful Oda clan, and launched a war against other ''daimyō'' to unif ...

(1582)

* Takeda Katsuyori

was a Japanese '' daimyō'' of the Sengoku period, who was famed as the head of the Takeda clan and the successor to the legendary warlord Takeda Shingen. He was son in law of Hojo Ujiyasu.

Early life

He was the son of Shingen by the daugh ...

(1582)

* Shibata Katsuie

or was a Japanese samurai and military commander during the Sengoku period.

He served Oda Nobunaga as one of his trusted generals, was severely wounded in the 1571 first siege of Nagashima, but then fought in the 1575 Battle of Nagashino an ...

(1583)

* Hōjō Ujimasa

was the fourth head of the later Hōjō clan, and ''daimyō'' of Odawara. Ujimasa succeeded the territory expansion policy from his father, Hojo Ujiyasu, and achieved the biggest territory in the clan's history.

Early life and rise

In 1538, ...

(1590)

* Sen no Rikyū

, also known simply as Rikyū, is considered the historical figure with the most profound influence on ''chanoyu,'' the Japanese "Way of Tea", particularly the tradition of ''wabi-cha''. He was also the first to emphasize several key aspects o ...

(1591)

* Toyotomi Hidetsugu

was a daimyō during the Sengoku period of Japan. He was the nephew and retainer of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the unifier and ruler of Japan from 1590 to 1598. Despite being Hideyoshi's closest adult, male relative, Hidetsugu was accused of atrociti ...

(1595)

* Torii Mototada

was a Japanese Samurai and Daimyo of the Sengoku period through late Azuchi–Momoyama period, who served Tokugawa Ieyasu. Torii died at the siege of Fushimi where his garrison was greatly outnumbered and destroyed by the army of Ishida M ...

(1600)

* Tokugawa Tadanaga

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' of the early Edo period. The son of the second ''shōgun'' Tokugawa Hidetada, his elder brother was the third ''shōgun'' Tokugawa Iemitsu.

Life

Often called ''Suruga Dainagon'' (the major counsellor of Suruga), ...

(1634)

* Forty-six of the Forty-seven ''rōnin'' (1703)

* Watanabe Kazan (1841)

* Tanaka Shinbei

was one of the Four Hitokiri of the Bakumatsu, elite samurai, active in Japan during the late Tokugawa shogunate in the 1860s.

Biography

The Hitokiri Shinbei worked under the command of Takechi Hanpeita, the leader of the Kinnō-tō, who sough ...

(1863)

* Takechi Hanpeita (1865)

* Yamanami Keisuke (1865)

* Byakkotai (group of samurai youths) (1868)

* Saigō Takamori

was a Japanese samurai and nobleman. He was one of the most influential samurai in Japanese history and one of the three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration. Living during the late Edo and early Meiji periods, he later led the Satsum ...

(1877)

* Emilio Salgari (1911)

* Nogi Maresuke and Nogi Shizuko (1912)

* Chujiro Hayashi

, a disciple of Mikao Usui, played a major role in the transmission of Reiki out of Japan.

Hayashi was a naval physician and employed Reiki to treat his patients. He began studying with Usui in the early 1920s. He made his branch, Hayashi Reiki ...

(1940)

* Seigō Nakano

(12 February 1886 – 27 October 1943) was a journalist and politician in Imperial Japan, known primarily for involvement in far-right politics through leadership of the ''Tōhōkai'' ("Far East Society") party, as well as his opposition to ...

(1943)

* Yoshitsugu Saitō (1944)

* Hideyoshi Obata (1944)

* Kunio Nakagawa

was the commander of Japanese forces which defended the island of Peleliu in the Battle of Peleliu which took place from 15 September to 27 November 1944. He inflicted heavy losses on attacking U.S. Marines and held Peleliu Island for almost th ...

(1944)

* Isamu Chō

was an officer in the Imperial Japanese Army known for his support of ultranationalist politics and involvement in a number of attempted coup d'états in pre-World War II Japan.

Biography

Chō was a native of Fukuoka prefecture. He graduated ...

and Mitsuru Ushijima (1945)

* Korechika Anami

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II who was War Minister during the surrender of Japan.

Early life and career

Anami was born in Taketa city in Ōita Prefecture, where his father was a senior bureaucrat in the Home ...

(1945)

* Takijirō Ōnishi (1945)

* Yukio Mishima

, born , was a Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor, model, Shintoist, nationalist, and founder of the , an unarmed civilian militia. Mishima is considered one of the most important Japanese authors of the 20th century. He was considered fo ...

(1970)

* Masakatsu Morita (1970)

* Isao Inokuma (2001)

In popular culture

The expected honor-suicide of the samurai wife is frequently referenced in Japanese literature and film, such as in ''Taiko'' by Eiji Yoshikawa, '' Humanity and Paper Balloons'', and ''

The expected honor-suicide of the samurai wife is frequently referenced in Japanese literature and film, such as in ''Taiko'' by Eiji Yoshikawa, '' Humanity and Paper Balloons'', and ''Rashomon

is a 1950 Jidaigeki psychological thriller/crime film directed and written by Akira Kurosawa, working in close collaboration with cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa. Starring Toshiro Mifune, Machiko Kyō, Masayuki Mori, and Takashi Shimura as va ...

''. ''Seppuku'' is referenced and described multiple times in the 1975 James Clavell

James Clavell (born Charles Edmund Dumaresq Clavell; 10 October 1921 – 7 September 1994) was an Australian-born British (later naturalized American) writer, screenwriter, director, and World War II veteran and prisoner of war. Clavell is best ...

novel, ''Shōgun

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

''; its subsequent 1980 miniseries ''Shōgun

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

'' brought the term and the concept to mainstream Western attention. It was staged by the young protagonist in the 1971 dark American comedy ''Harold and Maude

''Harold and Maude'' is a 1971 American romantic black comedy–drama film directed by Hal Ashby and released by Paramount Pictures. It incorporates elements of dark humor and existentialist drama. The plot follows the exploits of Harold Chase ...

''.

In Puccini

Giacomo Puccini (Lucca, 22 December 1858Bruxelles, 29 November 1924) was an Italian composer known primarily for his operas. Regarded as the greatest and most successful proponent of Italian opera after Verdi, he was descended from a long li ...

's 1904 opera ''Madame Butterfly

''Madama Butterfly'' (; ''Madame Butterfly'') is an opera in three acts (originally two) by Giacomo Puccini, with an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa.

It is based on the short story " Madame Butterfly" (1898) by John Lu ...

'', wronged child-bride Cio-Cio-san commits Seppuku in the final moments of the opera, after hearing that the father of her child, although he has finally returned to Japan, much to her initial delight, has in the meantime married an American lady and has come to take the child away from her.

Throughout the novels depicting the 30th century and onward ''Battletech

''BattleTech'' is a wargaming and military science fiction franchise launched by FASA Corporation in 1984, acquired by WizKids in 2001, which was in turn acquired by Topps in 2003; and published since 2007 by Catalyst Game Labs. The trademark ...

'' universe, members of House Kurita – who are based on feudal Japanese culture, despite the futuristic setting – frequently atone for their failures by performing seppuku.

In the 2003, film ''The Last Samurai

''The Last Samurai'' is a 2003 epic period action drama film directed and co-produced by Edward Zwick, who also co-wrote the screenplay with John Logan and Marshall Herskovitz from a story devised by Logan. The film stars Ken Watanabe in th ...

'', the act of ''seppuku'' is depicted twice. The defeated Imperial officer General Hasegawa commits ''seppuku'', while his enemy Katsumoto (Ken Watanabe

is a Japanese actor. To English-speaking audiences, he is known for playing tragic hero characters, such as General Tadamichi Kuribayashi in ''Letters from Iwo Jima'' and Lord Katsumoto Moritsugu in ''The Last Samurai'', for which he was nomin ...

) acts as ''kaishakunin'' and decapitates him. Later, the mortally wounded samurai leader Katsumoto performs ''seppuku'' with former US Army Captain Nathan Algren's help. This is also depicted ''en masse'' in the film '' 47 Ronin'' starring Keanu Reeves when the 47 ronin are punished for disobeying the shogun's orders by avenging their master. In the 2011 film '' My Way'', an Imperial Japanese colonel is ordered to commit ''seppuku'' by his superiors after ordering a retreat from an oil field overrun by Russian and Mongolian troops in the 1939 Battle of Khalkin Gol

The Battles of Khalkhin Gol (russian: Бои на Халхин-Голе; mn, Халхын голын байлдаан) were the decisive engagements of the undeclared Soviet–Japanese border conflicts involving the Soviet Union, Mongolia, Ja ...

.

In Season 15 Episode 12 of '' Law & Order: Special Victims Unit'', titled "Jersey Breakdown", a Japanophile New Jersey judge with a large samurai sword collection commits harakiri when he realizes that the police are onto him for raping a 12-year-old Japanese girl in a Jersey nightclub. Seppuku is depicted in season 1, episode 5, of the Amazon Prime Video

Amazon Prime Video, also known simply as Prime Video, is an American subscription video on-demand over-the-top streaming and rental service of Amazon offered as a standalone service or as part of Amazon's Prime subscription. The service p ...

TV series '' The Man in the High Castle'' (2015). In this dystopian alternate history the Japanese Imperial Force controls the West coast of the United States after a Nazi victory against the Allies in World War Two. During the episode, the Japanese crown prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title is crown princess, which may refer either to an heiress apparent or, especially in earlier times, to the wife ...

makes an official visit to San Francisco but is shot during a public address. The captain of the Imperial Guard commits ''seppuku'' because of his failure of ensuring the prince's security. The head of the Kenpeitai

The , also known as Kempeitai, was the military police arm of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1881 to 1945 that also served as a secret police force. In addition, in Japanese-occupied territories, the Kenpeitai arrested or killed those suspecte ...

, Chief Inspector Takeshi Kido, states he will do the same if the assassin is not apprehended.

In the 2014 dark fantasy action role-playing video game ''Dark Souls II

is a 2014 action role-playing game developed by FromSoftware and published by Bandai Namco Games. An entry in the '' Dark Souls'' series, it was released for Windows, PlayStation 3, and Xbox 360. Taking place in the kingdom of Drangleic, the ...

'', the boss Sir Alonne performs the act of ''seppuku'' if the player defeats him within three minutes or if the player takes no damage, to retain his honor as a samurai by not falling into his enemies' hands. in the 2015 re-release ''Scholar of the First Sin'' it is obtainable only if the player takes no damage whatsoever.

In the 2015 tactical role-playing video game ''Fire Emblem Fates

''Fire Emblem Fates'' is a tactical role-playing video game for the Nintendo 3DS handheld video game console, developed by Intelligent Systems and Nintendo SPD and published by Nintendo. It was released in June 2015 in Japan, then released inter ...

'', Hoshidan high prince Ryoma takes his own life through the act of ''seppuku'', which he believes will let him retain his honor as a samurai by not falling into the hands of his enemies.

In the 2017 revival and final season of the animated series '' Samurai Jack'', the eponymous protagonist, distressed over his many failures to accomplish his quest as told in prior seasons, is then informed by a haunting samurai spirit that he has acted dishonorably by allowing many people to suffer and die from his failures, and must perform ''seppuku'' to atone for them.

In the 2022 dark fantasy action role-playing video game '' Elden Ring'', the player can receive the ability ''seppuku'', which has the player stab themselves through the stomach and then pull it out, coating their weapon in blood to increase their damage.

See also

* '' Harakiri'' – film by Masaki Kobayashi *Japanese funeral

The majority of funerals (, ''sōgi'' or , ''sōshiki'') in Japan include a wake, the cremation of the deceased, a burial in a family grave, and a periodic memorial service. According to 2007 statistics, 99.81% of deceased Japanese are cremated ...

* Junshi – following the lord in death

* Kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to ...

, Japanese suicide bombers

* Puputan, Indonesian ritual suicide

* Shame society

Shame is an unpleasant self-conscious emotion often associated with negative self-evaluation; motivation to quit; and feelings of pain, exposure, distrust, powerlessness, and worthlessness.

Definition

Shame is a discrete, basic emotion, d ...

* Suicide in Japan

References

Further reading

* * * *Seppuku

– A Practical Guide (tongue-in-cheek) * * *

Zuihoden

– The mausoleum of

Date Masamune

was a regional ruler of Japan's Azuchi–Momoyama period through early Edo period. Heir to a long line of powerful ''daimyō'' in the Tōhoku region, he went on to found the modern-day city of Sendai. An outstanding tactician, he was made all ...

When he died, twenty of his followers killed themselves to serve him in the next life. They lay in state at Zuihoden

Seppuku and "cruel punishments" at the end of Tokugawa Shogunate

From the Buke Sho Hatto (1663) – :"That the custom of following a master in death is wrong and unprofitable is a caution which has been at times given of old; but, owing to the fact that it has not actually been prohibited, the number of those who cut their belly to follow their lord on his decease has become very great. For the future, to those retainers who may be animated by such an idea, their respective lords should intimate, constantly and in very strong terms, their disapproval of the custom. If, notwithstanding this warning, any instance of the practice should occur, it will be deemed that the deceased lord was to blame for unreadiness. Henceforward, moreover, his son and successor will be held to be blameworthy for incompetence, as not having prevented the suicides." *

External links

* * {{Suicide navbox Japanese culture Japanese words and phrases Suicide methods