Hanging Rock, South Carolina on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a

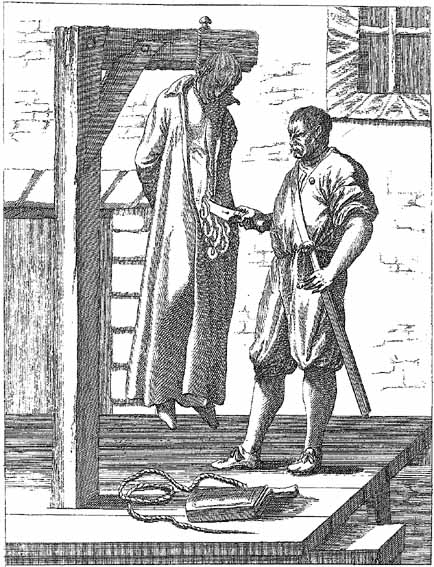

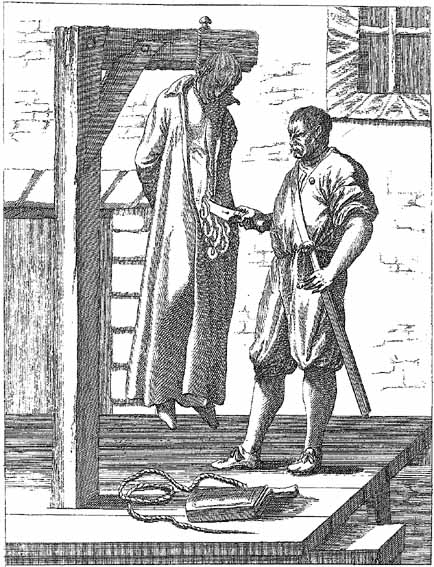

The short drop is a method of hanging in which the condemned prisoner stands on a raised support such as a stool, ladder, cart, or other vehicle, with the noose around the neck. The support is then moved away, leaving the person dangling from the rope.

Suspended by the neck, the weight of the body tightens the noose around the neck effecting

The short drop is a method of hanging in which the condemned prisoner stands on a raised support such as a stool, ladder, cart, or other vehicle, with the noose around the neck. The support is then moved away, leaving the person dangling from the rope.

Suspended by the neck, the weight of the body tightens the noose around the neck effecting

A short-drop variant is the

A short-drop variant is the

The standard drop involves a drop of between and came into use from 1866, when the scientific details were published by Irish doctor

The standard drop involves a drop of between and came into use from 1866, when the scientific details were published by Irish doctor

This process, also known as the measured drop, was introduced to Britain in 1872 by

This process, also known as the measured drop, was introduced to Britain in 1872 by

Hanging is a common

Hanging is a common

A hanging may induce one or more of the following medical conditions, some leading to death:

* Closure of

A hanging may induce one or more of the following medical conditions, some leading to death:

* Closure of  In the absence of fracture and dislocation, occlusion of blood vessels becomes the major cause of death, rather than

In the absence of fracture and dislocation, occlusion of blood vessels becomes the major cause of death, rather than

Hanging has been a method of

Hanging has been a method of

, Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance, 8 November 2005 in practice, the last execution in Australia was the hanging of

, MSN Encarta

31 October 2009.

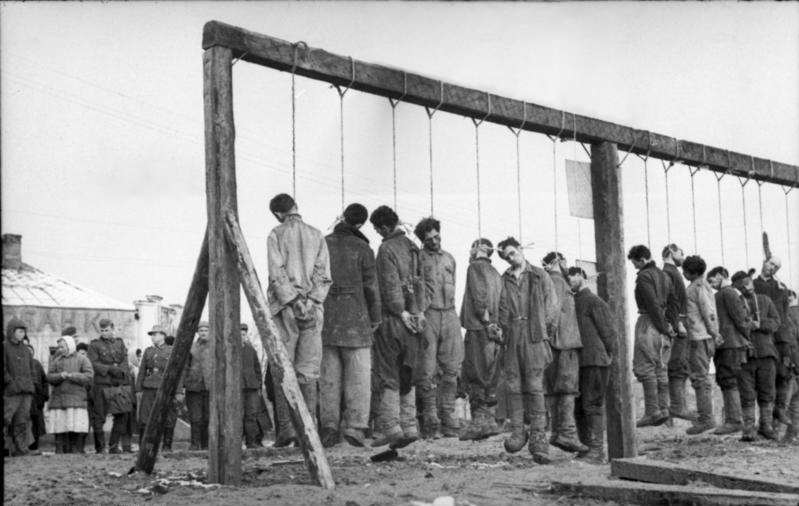

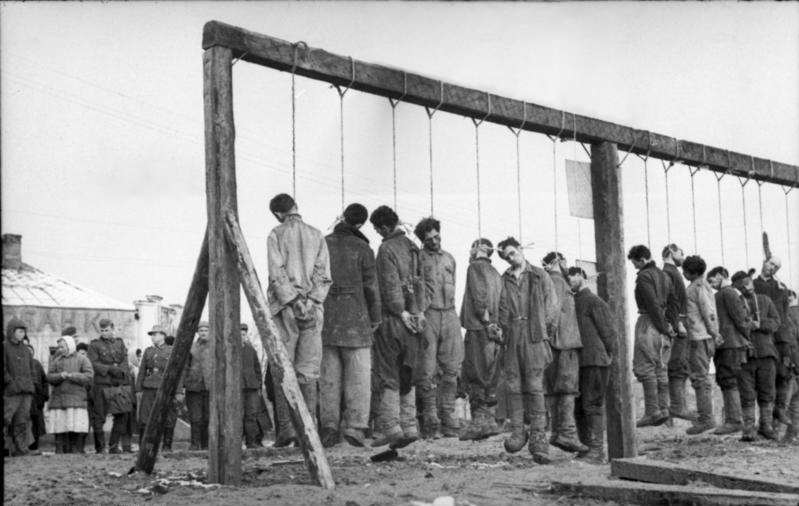

In the territories occupied by

In the territories occupied by

All executions in India since independence have been carried out by hanging, although the law provides for military executions to be carried out by firing squad. In 1949,

All executions in India since independence have been carried out by hanging, although the law provides for military executions to be carried out by firing squad. In 1949,

Death by hanging is the primary means of capital punishment in Iran, which carries out one of the highest numbers of annual executions in the world. The method used is the short drop, which does not break the neck of the condemned, but rather causes a slower death due to strangulation. It is legal for murder, rape, and drug trafficking unless the criminal pays

Death by hanging is the primary means of capital punishment in Iran, which carries out one of the highest numbers of annual executions in the world. The method used is the short drop, which does not break the neck of the condemned, but rather causes a slower death due to strangulation. It is legal for murder, rape, and drug trafficking unless the criminal pays

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose

A noose is a loop at the end of a rope in which the knot tightens under load and can be loosened without untying the knot.

The knot can be used to secure a rope to a post, pole, or animal but only where the end is in a position that the loop can ...

or ligature

Ligature may refer to:

* Ligature (medicine), a piece of suture used to shut off a blood vessel or other anatomical structure

** Ligature (orthodontic), used in dentistry

* Ligature (music), an element of musical notation used especially in the me ...

around the neck

The neck is the part of the body on many vertebrates that connects the head with the torso. The neck supports the weight of the head and protects the nerves that carry sensory and motor information from the brain down to the rest of the body. In ...

.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

'' states that hanging in this sense is "specifically to put to death by suspension by the neck", though it formerly also referred to crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagin ...

and death by impalement

Impalement, as a method of torture and execution, is the penetration of a human by an object such as a stake, pole, spear, or hook, often by the complete or partial perforation of the torso. It was particularly used in response to "crimes aga ...

in which the body would remain "hanging". Hanging has been a common method of capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

since medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the Post-classical, post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with t ...

times, and is the primary execution method in numerous countries and regions. The first known account of execution by hanging was in Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

'' (Book XXII). In this specialised meaning of the common word ''hang'', the past and past participle is ''hanged'' instead of ''hung''.

Hanging is a common method of suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

in which a person applies a ligature to the neck and brings about unconsciousness and then death by suspension or partial suspension.

Methods of judicial hanging

There are numerous methods of hanging in execution which instigate death either bycervical fracture

A cervical fracture, commonly called a broken neck, is a fracture of any of the seven cervical vertebrae in the neck. Examples of common causes in humans are traffic collisions and diving into shallow water. Abnormal movement of neck bones or pie ...

or by strangulation.

Short drop

The short drop is a method of hanging in which the condemned prisoner stands on a raised support such as a stool, ladder, cart, or other vehicle, with the noose around the neck. The support is then moved away, leaving the person dangling from the rope.

Suspended by the neck, the weight of the body tightens the noose around the neck effecting

The short drop is a method of hanging in which the condemned prisoner stands on a raised support such as a stool, ladder, cart, or other vehicle, with the noose around the neck. The support is then moved away, leaving the person dangling from the rope.

Suspended by the neck, the weight of the body tightens the noose around the neck effecting strangulation

Strangling is compression of the neck that may lead to unconsciousness or death by causing an increasingly hypoxic state in the brain. Fatal strangling typically occurs in cases of violence, accidents, and is one of two main ways that hanging ...

and death. This typically takes 10–20 minutes.

Before 1850, the short drop was the standard method of hanging, and it is still common in suicides

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and subs ...

and extrajudicial hangings (such as lynchings

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

and summary execution

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes include ...

s) which do not benefit from the specialised equipment and drop-length calculation tables used in the newer methods.

Pole method

A short-drop variant is the

A short-drop variant is the Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

"pole" method, called Würgegalgen (literally: strangling gallows), in which the following steps take place:

# The condemned is made to stand before a specialized vertical pole or pillar, approximately in height.

# A rope is attached around the condemned's feet and routed through a pulley at the base of the pole.

# The condemned is hoisted to the top of the pole by means of a sling running across the chest and under the armpits.

# A narrow-diameter noose is looped around the prisoner's neck, then secured to a hook mounted at the top of the pole.

# The chest sling is released, and the prisoner is rapidly jerked downward by the assistant executioners via the foot rope.

# The executioner stands on a stepped platform approximately high beside the condemned. The executioner would place the heel of his hand beneath the prisoner's jaw to increase the force on the neck vertebrae at the end of the drop, then manually dislocate the condemned's neck by forcing the head to one side while the neck vertebrae were under traction.

This method was later also adopted by the successor states, most notably by Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, where the "pole" method was used as the single type of execution from 1918 until the abolition of capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

in 1990. Nazi war criminal Karl Hermann Frank

Karl Hermann Frank (24 January 1898 – 22 May 1946) was a prominent Sudeten German Nazi official in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia prior to and during World War II. Attaining the rank of ''Obergruppenführer'', he was in command of th ...

, executed in 1946 in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

, was among approximately 1,000 condemned people executed in this manner in Czechoslovakia.

Standard drop

The standard drop involves a drop of between and came into use from 1866, when the scientific details were published by Irish doctor

The standard drop involves a drop of between and came into use from 1866, when the scientific details were published by Irish doctor Samuel Haughton

Samuel Haughton (21 December 1821 – 31 October 1897) was an Irish clergyman, medical doctor, and scientific writer.

Biography

The scientist Samuel Haughton was born in Carlow, the son of another Samuel Haughton (1786-1874) and grandson (by h ...

. Its use rapidly spread to English-speaking countries and those with judicial systems of English origin.

It was considered a humane improvement on the short drop because it was intended to be enough to break the person's neck, causing immediate unconsciousness and rapid brain death.

This method was used to execute condemned Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

under United States jurisdiction after the Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

including Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

and Ernst Kaltenbrunner

Ernst Kaltenbrunner (4 October 190316 October 1946) was a high-ranking Austrian SS official during the Nazi era and a major perpetrator of the Holocaust. After the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in 1942, and a brief period under Heinrich ...

. In the execution of Ribbentrop, historian Giles MacDonogh records that: "The hangman botched the execution and the rope throttled the former foreign minister for 20 minutes before he expired." A ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energ ...

'' magazine report on the execution merely says: "The trap fell open and with a sound midway between a rumble and a crash, Ribbentrop disappeared. The rope quivered for a time, then stood tautly straight."

Long drop

This process, also known as the measured drop, was introduced to Britain in 1872 by

This process, also known as the measured drop, was introduced to Britain in 1872 by William Marwood

William Marwood (1818 – 4 September 1883) was a hangman for the British government. He developed the technique of hanging known as the " long drop".

Early life

Marwood was born in 1818 in the village of Goulceby, the fifth of ten childre ...

as a scientific advance on the standard drop. Instead of everyone falling the same standard distance, the person's height and weight were used to determine how much slack would be provided in the rope so that the distance dropped would be enough to ensure that the neck was broken, but not so much that the person was decapitated

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the au ...

. The careful placement of the eye or knot of the noose (so that the head was jerked back as the rope tightened) contributed to breaking the neck.

Prior to 1892, the drop was between four and ten feet (about one to three metres), depending on the weight of the body, and was calculated to deliver an energy of , which fractured the neck at either the 2nd and 3rd or 4th and 5th cervical vertebrae

In tetrapods, cervical vertebrae (singular: vertebra) are the vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Truncal vertebrae (divided into thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mammals) lie caudal (toward the tail) of cervical vertebrae. In ...

. This force resulted in some decapitation

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the i ...

s, such as the infamous case of Black Jack Ketchum

Thomas Edward Ketchum (known as Black Jack; October 31, 1863 – April 26, 1901) was an American cowboy who later became an outlaw. He was executed in 1901 for attempted train robbery. The execution by hanging was botched; he was decapitate ...

in New Mexico Territory

The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912. It was created from the U.S. provisional government of New Mexico, as a result of ''Santa Fe de Nuevo México ...

in 1901, owing to a significant weight gain while in custody not having been factored into the drop calculations. Between 1892 and 1913, the length of the drop was shortened to avoid decapitation. After 1913, other factors were also taken into account, and the energy delivered was reduced to about . The decapitation of Eva Dugan

Eva Dugan (1878 – February 21, 1930) was a convicted murderer whose execution by hanging at the state prison in Florence, Arizona, resulted in her decapitation and influenced the state of Arizona to replace hanging with the lethal gas chamber ...

during a botched hanging in 1930 led the state of Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

to switch to the gas chamber

A gas chamber is an apparatus for killing humans or other animals with gas, consisting of a sealed chamber into which a poisonous or asphyxiant gas is introduced. Poisonous agents used include hydrogen cyanide and carbon monoxide.

Histor ...

as its primary execution method, on the grounds that it was believed more humane. One of the more recent decapitations as a result of the long drop occurred when Barzan Ibrahim al-Tikriti

Barzan Ibrahim Hassan al-Tikriti (17 February 1951 – 15 January 2007) ( ar, برزان إبراهيم الحسن التكريتي), also known as Barazan Ibrahim al-Tikriti, Barasan Ibrahem Alhassen and Barzan Hassan, was one of three half-brot ...

was hanged in Iraq in 2007. Accidental decapitation also occurred during the 1962 hanging of Arthur Lucas

Arthur Lucas (December 18, 1907 - December 11, 1962), originally from the United States, U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, was one of the last two people to be executed in Canada, on 11 December 1962. Lucas had been convicted of the m ...

, one of the last two people to be put to death in Canada.

Nazis executed under British jurisdiction, including Josef Kramer

Josef Kramer (10 November 1906 – 13 December 1945) was Hauptsturmführer and the Commandant of Auschwitz-Birkenau (from 8 May 1944 to 25 November 1944) and of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp (from December 1944 to its liberation on 15 Apr ...

, Fritz Klein

Fritz Klein (24 November 1888 – 13 December 1945) was an Austrian Nazi doctor and war criminal, hanged for his role in atrocities at Auschwitz concentration camp and Bergen-Belsen concentration camp during the Holocaust.

Early life and educ ...

, Irma Grese

Irma Ilse Ida Grese (7 October 1923 – 13 December 1945) was a Nazi concentration camp guard at Ravensbrück and Auschwitz, and served as warden of the women's section of Bergen-Belsen. She was a volunteer member of the SS.

Grese was convi ...

and Elisabeth Volkenrath

Elisabeth Volkenrath (née Mühlau; 5 September 1919 – 13 December 1945) was a German supervisor at several Nazi concentration camps during World War II.

Volkenrath, née Mühlau, was an ''ungelernte Hilfskraft'' (unskilled worker) when she vo ...

, were hanged by Albert Pierrepoint

Albert Pierrepoint (; 30 March 1905 – 10 July 1992) was an English hangman who executed between 435 and 600 people in a 25-year career that ended in 1956. His father Henry and uncle Thomas were official hangmen before him.

Pierrepoint ...

using the variable-drop method devised by Marwood. The record speed for a British long-drop hanging was seven seconds from the executioner entering the cell to the drop. Speed was considered to be important in the British system as it reduced the condemned's mental distress.

As suicide

Hanging is a common

Hanging is a common suicide method

A suicide method is any means by which a person chooses to end their life. Suicide attempts do not always result in death, and a nonfatal suicide attempt can leave the person with serious physical injuries, long-term health problems, and brai ...

. The materials necessary for suicide by hanging are readily available to the average person, compared with firearms or poisons. Full suspension is not required, and for this reason, hanging is especially commonplace among suicidal prison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, correc ...

ers (see suicide watch

Suicide watch (sometimes shortened to SW) is an intensive monitoring process used to ensure that any person cannot attempt suicide. Usually the term is used in reference to inmates or patients in a prison, hospital, psychiatric hospital or milit ...

). A type of hanging comparable to full suspension hanging may be obtained by self-strangulation using a ligature

Ligature may refer to:

* Ligature (medicine), a piece of suture used to shut off a blood vessel or other anatomical structure

** Ligature (orthodontic), used in dentistry

* Ligature (music), an element of musical notation used especially in the me ...

around the neck and the partial weight of the body (partial suspension) to tighten the ligature. When a suicidal hanging involves partial suspension the deceased is found to have both feet touching the ground, e.g., they are kneeling, crouching or standing. Partial suspension or partial weight-bearing on the ligature is sometimes used, particularly in prisons, mental hospitals or other institutions, where full suspension support is difficult to devise, because high ligature points (e.g., hooks or pipes) have been removed.

In Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, hanging is the most common method of suicide, and in the U.S., hanging is the second most common method, after self-inflicted gunshot wounds

A gunshot wound (GSW) is a penetrating injury caused by a projectile (e.g. a bullet) from a gun (typically firearm or air gun). Damages may include bleeding, bone fractures, organ damage, wound infection, loss of the ability to move part ...

. In the United Kingdom, where firearms are less easily available, in 2001 hanging was the most common method among men and the second most commonplace among women (after poisoning).

Those who survive a suicide-via-hanging attempt, whether due to breakage of the cord or ligature point, or being discovered and cut down, face a range of serious injuries, including cerebral anoxia

Cerebral hypoxia is a form of hypoxia (reduced supply of oxygen), specifically involving the brain; when the brain is completely deprived of oxygen, it is called ''cerebral anoxia''. There are four categories of cerebral hypoxia; they are, in o ...

(which can lead to permanent brain damage), laryngeal fracture, cervical spine fracture (which may cause paralysis

Paralysis (also known as plegia) is a loss of motor function in one or more muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory damage. In the United States, roughly 1 in 50 ...

), tracheal fracture, pharyngeal laceration, and carotid artery injury.

As human sacrifice

There are some suggestions that theVikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

practiced hanging as human sacrifices to Odin

Odin (; from non, Óðinn, ) is a widely revered Æsir, god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, v ...

, to honour Odin's own sacrifice

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exi ...

of hanging himself from Yggdrasil

Yggdrasil (from Old Norse ), in Norse cosmology, is an immense and central sacred tree. Around it exists all else, including the Nine Worlds.

Yggdrasil is attested in the ''Poetic Edda'' compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional s ...

. In Northern Europe, it is widely speculated that the Iron Age bog bodies, many who show signs of having been hanged were examples of human sacrifice to the gods.

Medical effects

A hanging may induce one or more of the following medical conditions, some leading to death:

* Closure of

A hanging may induce one or more of the following medical conditions, some leading to death:

* Closure of carotid arteries

In anatomy, the left and right common carotid arteries (carotids) (Entry "carotid"

in

cerebral hypoxia Cerebral hypoxia is a form of hypoxia (reduced supply of oxygen), specifically involving the brain; when the brain is completely deprived of oxygen, it is called ''cerebral anoxia''. There are four categories of cerebral hypoxia; they are, in o ...

* Closure of the in

cerebral hypoxia Cerebral hypoxia is a form of hypoxia (reduced supply of oxygen), specifically involving the brain; when the brain is completely deprived of oxygen, it is called ''cerebral anoxia''. There are four categories of cerebral hypoxia; they are, in o ...

jugular vein

The jugular veins are veins that take deoxygenated blood from the head back to the heart via the superior vena cava. The internal jugular vein descends next to the internal carotid artery and continues posteriorly to the sternocleidomastoid ...

s

* Breaking of the neck

The neck is the part of the body on many vertebrates that connects the head with the torso. The neck supports the weight of the head and protects the nerves that carry sensory and motor information from the brain down to the rest of the body. In ...

(cervical fracture

A cervical fracture, commonly called a broken neck, is a fracture of any of the seven cervical vertebrae in the neck. Examples of common causes in humans are traffic collisions and diving into shallow water. Abnormal movement of neck bones or pie ...

) causing traumatic spinal cord injury

A spinal cord injury (SCI) is damage to the spinal cord that causes temporary or permanent changes in its function. Symptoms may include loss of muscle function, sensation, or autonomic function in the parts of the body served by the spinal cor ...

or even unintended decapitation

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the i ...

* Closure of the airway

The respiratory tract is the subdivision of the respiratory system involved with the process of respiration in mammals. The respiratory tract is lined with respiratory epithelium as respiratory mucosa.

Air is breathed in through the nose to th ...

The cause of death in hanging depends on the conditions related to the event. When the body is released from a relatively high position, the major cause of death is severe trauma to the upper cervical spine. The injuries produced are highly variable. One study showed that only a small minority of a series of judicial hangings produced fractures to the cervical spine (6 out of 34 cases studied), with half of these fractures (3 out of 34) being the classic "hangman's fracture

Hangman's fracture is the colloquial name given to a fracture of both pedicles, or '' partes interarticulares'', of the ''axis vertebra'' ( C2).

Causes

The injury mainly occurs from falls, usually in elderly adults, and motor accidents mainly d ...

" (bilateral fractures of the pars interarticularis of the C2 vertebra). The location of the knot of the hanging rope is a major factor in determining the mechanics of cervical spine injury, with a submental knot (hangman's knot under the chin) being the only location capable of producing the sudden, straightforward hyperextension injury that causes the classic "hangman's fracture".

According to ''Historical and biomechanical aspects of hangman's fracture'', the phrase in the usual execution order, ''"hanged by the neck until dead,"'' was necessary. By the late 19th century that methodical study enabled authorities to routinely employ hanging in ways that would predictably kill the victim quickly.

The side, or subaural knot, has been shown to produce other, more complex injuries, with one thoroughly studied case producing only ligamentous injuries to the cervical spine and bilateral vertebral artery disruptions, but no major vertebral fractures or crush injuries to the spinal cord. Death from a "hangman's fracture" occurs mainly when the applied force is severe enough to also cause a severe subluxation

A subluxation is an incomplete or partial dislocation of a joint or organ.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a subluxation is a "significant structural displacement", and is therefore always visible on static imaging studies, suc ...

of the C2 and C3 vertebra that crushes the spinal cord and/or disrupts the vertebral arteries. Hangman's fractures from other hyperextension injuries (the most common being unrestrained motor vehicle accidents and falls or diving injuries where the face or chin suddenly strike an immovable object) are frequently survivable if the applied force does not cause a severe subluxation of C2 on C3.

In the absence of fracture and dislocation, occlusion of blood vessels becomes the major cause of death, rather than

In the absence of fracture and dislocation, occlusion of blood vessels becomes the major cause of death, rather than asphyxia

Asphyxia or asphyxiation is a condition of deficient supply of oxygen to the body which arises from abnormal breathing. Asphyxia causes generalized hypoxia, which affects primarily the tissues and organs. There are many circumstances that can i ...

tion. Obstruction of venous drainage of the brain via occlusion of the internal jugular veins leads to cerebral oedema

Cerebral edema is excess accumulation of fluid (edema) in the intracellular or extracellular spaces of the brain. This typically causes impaired nerve function, increased pressure within the skull, and can eventually lead to direct compressio ...

and then cerebral ischemia

Brain ischemia is a condition in which there is insufficient bloodflow to the brain to meet metabolic demand. This leads to poor oxygen supply or cerebral hypoxia and thus leads to the death of brain tissue or cerebral infarction/ischemic stroke. ...

. The face will typically become engorged and cyanotic

Cyanosis is the change of body tissue color to a bluish-purple hue as a result of having decreased amounts of oxygen bound to the hemoglobin in the red blood cells of the capillary bed. Body tissues that show cyanosis are usually in locations ...

(turned blue through lack of oxygen). There will be the classic sign of strangulation, petechiae

A petechia () is a small red or purple spot (≤4 mm in diameter) that can appear on the skin, conjunctiva, retina, and mucous membranes which is caused by haemorrhage of capillaries. The word is derived from Italian , 'freckle,' of obscure origin ...

, little blood marks on the face and in the eyes from burst blood capillaries. The tongue may protrude.

Compromise of the cerebral blood flow may occur by obstruction of the carotid arteries, even though their obstruction requires far more force than the obstruction of jugular veins, since they are seated deeper and they contain blood in much higher pressure compared to the jugular veins. Where death has occurred through carotid artery obstruction or cervical fracture, the face will typically be pale in colour and not show petechiae. Many reports and pictures exist of actual short-drop hangings that seem to show that the person died quickly, while others indicate a slow and agonising death by strangulation.

When cerebral circulation is severely compromised by any mechanism, arterial or venous, death occurs over four or more minutes from cerebral hypoxia, although the heart may continue to beat for some period after the brain can no longer be resuscitated. The time of death in such cases is a matter of convention. In judicial hangings, death is pronounced at cardiac arrest, which may occur at times from several minutes up to 15 minutes or longer after hanging. During suspension, once the prisoner has lapsed into unconsciousness, rippling movements of the body and limbs may occur for some time which are usually attributed to nervous and muscular reflexes. In Britain, it was normal to leave the body suspended for an hour to ensure death.

After death, the body typically shows marks of suspension: bruising and rope marks on the neck. Sphincters will relax spontaneously and urine and faeces will be evacuated. Forensic experts may often be able to tell if hanging is suicide or homicide, as each leaves a distinctive ligature mark. One of the hints they use is the hyoid bone

The hyoid bone (lingual bone or tongue-bone) () is a horseshoe-shaped bone situated in the anterior midline of the neck between the chin and the thyroid cartilage. At rest, it lies between the base of the mandible and the third cervical vertebr ...

. If broken, it often means the person has been murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person wit ...

ed by manual choking

Choking, also known as foreign body airway obstruction (FBAO), is a phenomenon that occurs when breathing is impeded by a blockage inside of the respiratory tract. An obstruction that prevents oxygen from entering the lungs results in oxygen de ...

.

Notable practices across the globe

Hanging has been a method of

Hanging has been a method of capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

in many countries, and is still used by many countries to this day. Long-drop hanging is mainly used by former British colonies, while short-drop and suspension hanging is common in Iran.

Afghanistan

Hanging is the most used form of capital punishment inAfghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

.

Australia

Capital punishment was a part of thelegal system of Australia

The legal system of Australia has multiple forms. It includes a written constitution, unwritten constitutional conventions, statutes, regulations, and the judicially determined common law system. Its legal institutions and traditions are sub ...

from the establishment of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

as a British penal colony, until 1985, by which time all Australian states and territories had abolished the death penalty;Countries that have abandoned the use of the death penalty, Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance, 8 November 2005 in practice, the last execution in Australia was the hanging of

Ronald Ryan

Ronald Joseph Ryan (21 February 1925 – 3 February 1967) was the last person to be legally executed in Australia. Ryan was found guilty of shooting and killing warder George Hodson during an escape from Pentridge Prison, Victoria, in 1965. R ...

on 3 February 1967, in Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

.

During the 19th century, crimes that could carry a death sentence included burglary

Burglary, also called breaking and entering and sometimes housebreaking, is the act of entering a building or other areas without permission, with the intention of committing a criminal offence. Usually that offence is theft, robbery or murder ...

, sheep theft, forgery

Forgery is a white-collar crime that generally refers to the false making or material alteration of a legal instrument with the specific intent to defraud anyone (other than themself). Tampering with a certain legal instrument may be forbidd ...

, sexual assault

Sexual assault is an act in which one intentionally sexually touches another person without that person's consent, or coerces or physically forces a person to engage in a sexual act against their will. It is a form of sexual violence, which ...

s, murder and manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th cen ...

. During the 19th century, there were roughly eighty people hanged every year throughout the Australian colonies for these crimes.

Bangladesh

Hanging is the only method of execution inBangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

, ever since its independence.

Brazil

Death by hanging was the customary method of capital punishment in Brazil throughout its history. Some important national heroes likeTiradentes

Joaquim José da Silva Xavier (; 12 November 1746 – 21 April 1792), known as Tiradentes (), was a leading member of the colonial Brazilian revolutionary movement known as Inconfidência Mineira, whose aim was full independence from P ...

(1792) were killed by hanging. The last man executed in Brazil was the slave Francisco, in 1876. The death penalty was abolished for all crimes, except for those committed under extraordinary circumstances such as war or military law, in 1890.Capital Punishment Worldwide, MSN Encarta

31 October 2009.

Bulgaria

Bulgaria's national hero,Vasil Levski

Vasil Levski ( bg, Васил Левски, spelled in old Bulgarian orthography as , ), born Vasil Ivanov Kunchev (; 18 July 1837 – 18 February 1873), was a Bulgarian revolutionary who is, today, a national hero of Bulgaria. Dubbed th ...

, was executed by hanging by the Ottoman court in Sofia

Sofia ( ; bg, София, Sofiya, ) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain in the western parts of the country. The city is built west of the Iskar river, and ha ...

in 1873. Every year since Bulgaria's liberation, thousands come with flowers on the date of his death, 19 February, to his monument where the gallows stood. The last execution was in 1989, and the death penalty was abolished for all crimes in 1998.

Canada

Historically, hanging was the only method of execution used in Canada and was in use as possible punishment for all murders until 1961, when murders were reclassified into capital and non-capital offences. The death penalty was restricted to apply only for certain offences to the National Defence Act in 1976 and was completely abolished in 1998. The last hangings in Canada took place on 11 December 1962.Egypt

In 1955, Egypt hanged three Israelis on charges of spying. In 1982 Egypt hanged three civilians convicted of theassassination of Anwar Sadat

Anwar Sadat, the 3rd President of Egypt, was assassinated on 6 October 1981 during the annual victory parade held in Cairo to celebrate Operation Badr, during which the Egyptian Army had crossed the Suez Canal and taken back a small part of t ...

. In 2004, Egypt hanged five militants on charges of trying to kill the Prime Minister. To this day, hanging remains the standard method of capital punishment in Egypt, which executes more people each year than any other African country.

Germany

In the territories occupied by

In the territories occupied by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

from 1939 to 1945, strangulation hanging was a preferred means of public execution, although more criminal executions were performed by guillotine

A guillotine is an apparatus designed for efficiently carrying out executions by beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secured with stocks at th ...

than hanging. The most commonly sentenced were partisans and black market

A black market, underground economy, or shadow economy is a clandestine market or series of transactions that has some aspect of illegality or is characterized by noncompliance with an institutional set of rules. If the rule defines the se ...

eers, whose bodies were usually left hanging for long periods. There are also numerous reports of concentration camp inmates being hanged. Hanging was continued in post-war Germany in the British and US Occupation Zones under their jurisdiction, and for Nazi war criminals, until well after (western) Germany itself had abolished the death penalty by the German constitution

The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (german: Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland) is the constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany.

The West German Constitution was approved in Bonn on 8 May 1949 and came in ...

as adopted in 1949. West Berlin was not subject to the ''Grundgesetz'' ( Basic Law) and abolished the death penalty in 1951. The German Democratic Republic

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

abolished the death penalty in 1987. The last execution ordered by a West German court was carried out by guillotine in Moabit prison in 1949. The last hanging in Germany was the one ordered of several war criminals in Landsberg am Lech

Landsberg am Lech (Landsberg at the Lech) is a town in southwest Bavaria, Germany, about 65 kilometers west of Munich and 35 kilometers south of Augsburg. It is the capital of the district of Landsberg am Lech.

Overview

Landsberg is situated o ...

on 7 June 1951. The last known execution in East Germany was in 1981 by a pistol shot to the neck.

Hungary

The prime minister of Hungary, during the1956 Revolution

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 10 November 1956; hu, 1956-os forradalom), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was a countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the Hunga ...

, Imre Nagy

Imre Nagy (; 7 June 1896 – 16 June 1958) was a Hungarian communist politician who served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers (''de facto'' Prime Minister) of the Hungarian People's Republic from 1953 to 1955. In 1956 Nagy became leader ...

, was secretly tried, executed by hanging, and buried unceremoniously by the new Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

-backed Hungarian government, in 1958. Nagy was later publicly exonerated by Hungary. Capital punishment was abolished for all crimes in 1990.

India

All executions in India since independence have been carried out by hanging, although the law provides for military executions to be carried out by firing squad. In 1949,

All executions in India since independence have been carried out by hanging, although the law provides for military executions to be carried out by firing squad. In 1949, Nathuram Godse

Nathuram Vinayak Godse (19 May 1910 – 15 November 1949) was the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi. He was a Hindu nationalist from Maharashtra who shot Gandhi in the chest three times at point blank range at a multi-faith prayer meeting in Birla ...

, who had been sentenced to death for the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, was the first person to be executed by hanging in independent India.

The Supreme Court of India

The Supreme Court of India ( IAST: ) is the supreme judicial authority of India and is the highest court of the Republic of India under the constitution. It is the most senior constitutional court, has the final decision in all legal matters ...

has suggested that capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

should be given only in the "rarest of rare cases".

Since 2001, eight people have been executed in India. Dhananjoy Chatterjee

Dhananjoy Chatterjee (14 August 1965 – 15 August 2004) was the first person who was judicially executed in India in the 21st century for murder. The execution by hanging took place in Alipore Jail, Kolkata, on 15 August 2004. He was charged i ...

, the 1991 rapist and murderer was executed on 14 August 2004 in Alipore Jail

The Alipore Jail or Alipore Central Jail, also known as Presidency Correctional Home, is a prison in Alipore, Kolkata, where political prisoners were kept under British rule, among them Subhas Chandra Bose. It also housed the Alipore Jail Press ...

, Kolkata. Ajmal Kasab

Mohammed Ajmal Amir Kasab (13 July 1987 – 21 November 2012) was a Pakistani terrorist and a member of the Lashkar-e-Taiba Islamism, Islamist Islamic terrorism, fighter organization, through which he took part in the 2008 Mumbai atta ...

, the lone surviving terrorist of the 2008 Mumbai attacks

The 2008 Mumbai attacks (also referred to as 26/11, pronounced "twenty six eleven") were a series of Terrorism, terrorist attacks that took place in November 2008, when 10 members of Lashkar-e-Taiba, an Islamist terrorist organisation from P ...

was executed on 21 November 2012 in Yerwada Central Jail

Yerwada Central Jail is a noted high-security prison in Yerwada, Pune in Maharashtra. This is the largest prison in the state of Maharashtra, and also one of the largest prisons in South Asia, housing over 5,000 prisoners (2017) spread over var ...

, Pune. The Supreme Court of India had previously rejected his mercy plea, which was then rejected by the President of India. He was hanged one week later. Afzal Guru

Mohammad Afzal Guru (June 1969 – 9 February 2013) was a Kashmiri separatist, who was convicted for his role in the 2001 Indian Parliament attack. He received a death sentence for his involvement, which was upheld by the Indian Supreme Co ...

, a terrorist found guilty of conspiracy in the December 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament, was executed by hanging in Tihar Jail

Tihar Prisons, also called Tihar Jail and Tihar Ashram, is a prison complex in India and the largest complex of prisons in South Asia. Run by Department of Delhi Prisons, Government of Delhi, the prison contains nine central prisons, and is one ...

, Delhi on 9 February 2013. Yakub Memon

Yakub or Yaqub ( ar, يعقوب, Yaʿqūb or Ya'kūb , links=no, also transliterated in other ways) is a male given name. It is the Arabic version of Jacob and James. The Arabic form ''Ya'qūb/Ya'kūb'' may be direct from the Hebrew or indirec ...

was convicted over his involvement in the 1993 Bombay bombings

The 1993 Bombay bombings were a series of 12 terrorist bombings that took place in Bombay, Maharashtra, on 12 March 1993. The single-day attacks resulted in 257 fatalities and 1,400 injuries. The attacks were coordinated by Dawood Ibrahim, le ...

by Special Terrorist and Disruptive Activities court on 27 July 2007. His appeals and petitions for clemency were all rejected and he was finally executed by hanging on 30 July 2015 in Nagpur jail. In March 2020, four prisoners convicted of rape and murder were executed by hanging in Tihar Jail.

Iran

Death by hanging is the primary means of capital punishment in Iran, which carries out one of the highest numbers of annual executions in the world. The method used is the short drop, which does not break the neck of the condemned, but rather causes a slower death due to strangulation. It is legal for murder, rape, and drug trafficking unless the criminal pays

Death by hanging is the primary means of capital punishment in Iran, which carries out one of the highest numbers of annual executions in the world. The method used is the short drop, which does not break the neck of the condemned, but rather causes a slower death due to strangulation. It is legal for murder, rape, and drug trafficking unless the criminal pays diyya

''Diya'' ( ar, دية; plural ''diyāt'', ar, ديات) in Islamic law, is the financial compensation paid to the victim or heirs of a victim in the cases of murder, bodily harm or property damage by mistake. It is an alternative punishment to ' ...

to the victim's family, thus attaining their forgiveness (see Sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

). If the presiding judge deems the case to be "causing public outrage", he can order the hanging to take place in public at the spot where the crime was committed, typically from a mobile telescoping crane which hoists the condemned high into the air. On 19 July 2005, two boys, Mahmoud Asgari and Ayaz Marhoni

Mahmoud Asgari ( fa, محمود عسگری), and Ayaz Marhoni ( fa, عیاض مرهونی), were Iranian teenagers from the province of Khorasan who were publicly hanged on July 19, 2005. They were executed after being convicted of having raped a 1 ...

, aged 15 and 17 respectively, who had been convicted of the rape of a 13-year-old boy, were hanged at Edalat (Justice) Square in Mashhad

Mashhad ( fa, مشهد, Mašhad ), also spelled Mashad, is the List of Iranian cities by population, second-most-populous city in Iran, located in the relatively remote north-east of the country about from Tehran. It serves as the capital of R ...

, on charges of homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

and rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ag ...

. On 15 August 2004, a 16-year-old girl, Atefeh Sahaaleh

Atefeh Rajabi Sahaaleh ( fa, عاطفه رجبی سهاله; September 21, 1987 – August 15, 2004) was an Iranian girl from the town of Neka who was executed a week after being sentenced to death by Haji Rezai, head of Neka's court, on charges o ...

(also called Atefeh Rajabi), was executed for having committed "acts incompatible with chastity

Chastity, also known as purity, is a virtue related to temperance. Someone who is ''chaste'' refrains either from sexual activity considered immoral or any sexual activity, according to their state of life. In some contexts, for example when mak ...

".

At dawn on 27 July 2008, the Iranian government executed 29 people at Evin Prison in Tehran. On 2 December 2008, an unnamed man was hanged for murder at Kazeroun Prison, just moments after he was pardoned by the murder victim's family. He was quickly cut down and rushed to a hospital, where he was successfully revived.

The conviction and hanging of Reyhaneh Jabbari caused international uproar as she was sentenced to death in 2009 and hanged on 25 October 2014 for murdering a former intelligence officer; according to Jabbari's testimony she stabbed him during an attempt at rape and then another person killed him.

Iraq

Hanging was used under the regime ofSaddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolution ...

, but was suspended along with capital punishment on 10 June 2003, when a coalition led by the United States invaded

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

and overthrew the previous regime. The death penalty was reinstated on 8 August 2004.

In September 2005, three murderers were the first people to be executed since the restoration. Then on 9 March 2006, an official of Iraq's Supreme Judicial Council confirmed that Iraqi authorities had executed the first insurgents

An insurgency is a violent, armed rebellion against authority waged by small, lightly armed bands who practice guerrilla warfare from primarily rural base areas. The key descriptive feature of insurgency is its asymmetric nature: small irreg ...

by hanging.

Saddam Hussein was sentenced to death by hanging for crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

on 5 November 2006, and was executed on 30 December 2006 at approximately 6:00 a.m. local time. During the drop, there was an audible crack indicating that his neck was broken, a successful example of a long-drop hanging.

Barzan Ibrahim

Barzan Ibrahim Hassan al-Tikriti (17 February 1951 – 15 January 2007) ( ar, برزان إبراهيم الحسن التكريتي), also known as Barazan Ibrahim al-Tikriti, Barasan Ibrahem Alhassen and Barzan Hassan, was one of three Sibling#h ...

, the head of the Mukhabarat, Saddam's security agency, and Awad Hamed al-Bandar

Awad Hamad al-Bandar ( ar, عواد حمد البندر السعدون, ʿAwād Ḥamad al-Bandar al-Saʿdūn; (2 January 1945 – 15 January 2007) was an Iraqi chief judge under Saddam Hussein's presidency. He was a member of the Arab Socialist ...

, former chief judge, were executed on 15 January 2007, also by the long-drop method, but Barzan was decapitated by the rope at the end of his fall.

Former vice-president Taha Yassin Ramadan

Taha Yasin Ramadan al-Jizrawi ( ar, طه ياسين رمضان الجزراوي; (1939 – 20 March 2007) was an Iraqi politician and military officer of Kurdish origin, who served as one of the three vice presidents of Iraq from March 1991 to t ...

had been sentenced to life in prison on 5 November 2006, but the sentence was changed to death by hanging on 12 February 2007. He was the fourth and final man to be executed for the 1982 crimes against humanity on 20 March 2007. The execution went smoothly.

At the Anfal genocide trial, Saddam's cousin Ali Hassan al-Majid

Ali Hassan Abd al-Majid al-Tikriti ( ar, علي حسن عبد المجيد التكريت, ʿAlī Ḥasan ʿAbd al-Majīd al-Tikrītī; 30 November 1941 – 25 January 2010), nicknamed Chemical Ali ( ar, علي الكيمياوي, ʿAlī al-Kīm ...

(''alias'' Chemical Ali), former defence minister Sultan Hashim Ahmed

Sulṭān Hāshim Aḥmad Muḥammad al-Ṭāʾī ( ar, سلطان هاشم أحمد محمد الطائي; 1945 – 19 July 2020) was an Iraqi military commander, who served as Minister of Defense under Saddam Hussein's regime. Considered one ...

al-Tay, and former deputy Hussein Rashid Mohammed were sentenced to hang for their role in the Al-Anfal Campaign

The Anfal campaign; ku, شاڵاوی ئەنفال or the Kurdish genocide was a counterinsurgency operation which was carried out by Ba'athist Iraq from February to September 1988, at the end of the Iran–Iraq War. The campaign targeted rur ...

against the Kurds on 24 June 2007. Al-Majid was sentenced to death three more times: once for the 1991 suppression of a Shi'a uprising along with Abdul-Ghani Abdul Ghafur on 2 December 2008; once for the 1999 crackdown in the assassination of Grand Ayatollah Mohammad al-Sadr on 2 March 2009; and once on 17 January 2010 for the gassing of the Kurds in 1988; he was hanged on 25 January.

On 26 October 2010, Saddam's top minister Tariq Aziz

Tariq Aziz ( ar, طارق عزيز , 28 April 1936 – 5 June 2015) was an Iraqi politician who served as Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Foreign Affairs and a close advisor of President Saddam Hussein. Their association began in the 1950s wh ...

was sentenced to hang for persecuting the members of rival Shi'a political parties. His sentence was commuted to indefinite imprisonment after Iraqi president Jalal Talabani

Jalal Talabani ( ku, مام جەلال تاڵەبانی, translit=Celal Talebanî; ar, جلال طالباني ; 1933 – 3 October 2017) was an Iraqi Kurdish politician who served as the sixth president of Iraq from 2006 to 2014, as well as ...

did not sign his execution order and he died in prison in 2015.

On 14 July 2011, Sultan Hashim Ahmed al-Tay and two of Saddam's half-brothers – Sabawi Ibrahim al-Tikriti

Sabawi Ibrahim al-Tikriti ( ar, سبعاوي إبراهيم التكريتي; 27 February 1947 – 8 July 2013), half-brother of Saddam Hussein, was the leader of the Iraqi secret service, the ''Mukhabarat'', at the time of the 1991 Gulf War. He w ...

and Watban Ibrahim al-Tikriti

Watban Ibrahim al-Nasiri ( ar, وطبان إبراهيم الناصري; 1952 – 13 August 2015) was a senior Interior Minister of Iraq. He was the half-brother of Saddam Hussein and the brother of Barzan al-Tikriti. He was taken into co ...

—both condemned to death on 11 March 2009 for the role in the executions of 42 traders who were accused of manipulating food prices

Food prices refer to the average price level for food across countries, regions and on a global scale. Food prices have an impact on producers and consumers of food.

Price levels depend on the food production process, including food marketing an ...

—were handed over to the Iraqi authorities for execution.

It is alleged that Iraq's government keeps the execution rate secret, and hundreds may be carried out every year. In 2007, Amnesty International stated that 900 people were at "imminent risk" of execution in Iraq.

Israel

Although Israel has provisions in its criminal law to use the death penalty for extraordinary crimes, it has been used only twice, and only one of those executions was by hanging. On 31 May 1962, Nazi leaderAdolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

''

Syria has publicly hanged people, such as two Jews in 1952, Israeli spy

Syria has publicly hanged people, such as two Jews in 1952, Israeli spy

File:Witches Being Hanged.jpg, An image of suspected

The hangman's noose was one of the various banishments the

The hangman's noose was one of the various banishments the

A completely different principle of hanging is to hang the convicted person from their legs, rather than from their neck, either as a form of torture, or as an execution method. In late medieval Germany, this came to be primarily associated with Jewish thieves, called the "Judenstrafe". The jurist Ulrich Tengler, in his highly influential "Layenspiegel" from 1509, describes the procedure as follows, in the section "Von Juden straff":

Guido Kisch showed that originally, this type of inverted hanging between two dogs was not a punishment specifically for Jews. Esther Cohen writes:

In Spain 1449, during a mob attack against the

A completely different principle of hanging is to hang the convicted person from their legs, rather than from their neck, either as a form of torture, or as an execution method. In late medieval Germany, this came to be primarily associated with Jewish thieves, called the "Judenstrafe". The jurist Ulrich Tengler, in his highly influential "Layenspiegel" from 1509, describes the procedure as follows, in the section "Von Juden straff":

Guido Kisch showed that originally, this type of inverted hanging between two dogs was not a punishment specifically for Jews. Esther Cohen writes:

In Spain 1449, during a mob attack against the

Deutsches bürgerthum im mittelalter

" Frankfurt am Main 1868, p.243 one in Halle in 1462, one in

In 1713,

In 1713,

A Case Of Strangulation Fabricated As Hanging

* ttp://www.deathpenaltyworldwide.org/index.cfm Death Penalty Worldwide Academic research database on the laws, practice, and statistics of capital punishment for every death penalty country in the world. {{Authority control Execution methods Human positions

''

Japan

All executions in Japan are carried out by hanging. On 23 December 1948,Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

, Kenji Doihara

was a Japanese army officer. As a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II, he was instrumental in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria.

As a leading intelligence officer, he played a key role to the Japanese machinations that le ...

, Akira Mutō

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. He was convicted of Japanese war crimes, war crimes and was executed by hanging. Mutō was implicated in both the Nanjing Massacre and the Manila massacre.

Biography

Mutō was a ...

, Iwane Matsui

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army and the commander of the expeditionary force sent to China in 1937. He was convicted of war crimes and executed by the Allies for his involvement in the Nanjing Massacre.

Born in Nagoya, Matsui chose ...

, Seishirō Itagaki

was a Japanese military officer and politician who served as a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II and War Minister from 1938 to 1939.

Itagaki was a main conspirator behind the Mukden Incident and held prestigious chief of ...

, Kōki Hirota

was a Japanese diplomat and politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1936 to 1937. Originally his name was . He was executed for war crimes committed during the Second Sino-Japanese War at the Tokyo Trials.

Early life

Hirota was ...

, and Heitaro Kimura were hanged at Sugamo Prison

Sugamo Prison (''Sugamo Kōchi-sho'', Kyūjitai: , Shinjitai: ) was a prison in Tokyo, Japan. It was located in the district of Ikebukuro, which is now part of the Toshima ward of Tokyo, Japan.

History

Sugamo Prison was originally built in 1 ...

by the U.S. occupation authorities in Ikebukuro

is a commercial and entertainment district in Toshima, Tokyo, Japan. Toshima ward offices, Ikebukuro station, and several shops, restaurants, and enormous department stores are located within city limits. It is considered the second largest ...

in Allied-occupied Japan

Japan was occupied and administered by the victorious Allies of World War II from the 1945 surrender of the Empire of Japan at the end of the war until the

Treaty of San Francisco took effect in 1952. The occupation, led by the United States wi ...

for war crimes, crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

, and crimes against peace

A crime of aggression or crime against peace is the planning, initiation, or execution of a large-scale and serious act of aggression using state military force. The definition and scope of the crime is controversial. The Rome Statute contains an ...

during the Asian-Pacific theatre of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

On 27 February 2004, the mastermind of the Sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway

The was an act of domestic terrorism perpetrated on 20 March 1995, in Tokyo, Japan, by members of the cult movement Aum Shinrikyo. In five coordinated attacks, the perpetrators released sarin on three lines of the Tokyo Metro (then ''Teito Rapid ...

, Shoko Asahara

, born , was the founder and leader of the Japanese doomsday cult known as Aum Shinrikyo. He was convicted of masterminding the deadly 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway, and was also involved in several other crimes. Asahara was sentenced ...

, was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. On 25 December 2006, serial killer Hiroaki Hidaka

was a Japanese serial killer.

Early life

Hidaka was born in the Miyazaki Prefecture. He was originally an excellent student, but he failed to enter the University of Tsukuba, his target college. He entered the Fukuoka University instead, but eve ...

and three others were hanged in Japan. Long-drop hanging is the method of carrying out judicial capital punishment on civilians in Japan, as in the cases of Norio Nagayama

was a Japanese spree killer and novelist.

Biography

Nagayama was born in Abashiri, Hokkaido and grew up with divorced parents. He moved to Tokyo in 1965 and, while working in Tokyo's Shibuya district, witnessed the Zama and Shibuya shootings.

...

, Mamoru Takuma

was a Japanese mass murderer who killed eight children in the Osaka school massacre in Ikeda, Osaka Prefecture, on 8 June 2001.

Takuma had a long history of mentally disturbed and anti-social behaviour, and an extensive criminal record includin ...

, and Tsutomu Miyazaki

was a Japanese serial killer who murdered four young girls in Tokyo and Saitama Prefecture between August 1988 and June 1989. He abducted and killed the girls, aged from 4 to 7, in his car before dismembering them and molesting their corpses. ...

. In 2018 Shoko Asahara

, born , was the founder and leader of the Japanese doomsday cult known as Aum Shinrikyo. He was convicted of masterminding the deadly 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway, and was also involved in several other crimes. Asahara was sentenced ...

and several of his cult members were hanged for committing the 1995 sarin gas attack.

Jordan

Death by hanging is the traditional method of capital punishment inJordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

. On 14 August 1993, Jordan hanged two Jordanians convicted of spying for Israel. Sajida al-Rishawi

Sajida Mubarak Atrous al-Rishawi ( ar, ساجدة مبارك عطروس الريشاوي} 1970 – 4 February 2015) was a failed suicide bomber. She was convicted of possessing explosives and intending to commit a terrorist act in the 9 November ...

, "The 4th bomber" of the 2005 Amman bombings

The 2005 Amman bombings were a series of coordinated suicide bomb attacks on three hotel lobbies in Amman, Jordan, on 9 November 2005. The explosions at the Grand Hyatt Hotel, the Radisson SAS Hotel, and the Days Inn started at around 20:50 l ...

, was executed by hanging alongside Ziad al-Karbouly

Ziad Khalaf al-Karbouly ( ar, زياد خلف الكربولي; 1970 - died 4 February 2015), a native of Al-Qa'im, was an Islamist former Iraqi officer and the son of an Iraqi tribal sheikh of the Al-Karabla clan of the Dulaim.

Arrest and tria ...

on 4 February 2015 in retribution for the immolation

Immolation may refer to:

*Death by burning

*Self-immolation, the act of burning oneself

*Immolation (band), a death metal band from Yonkers, New York

*''The Immolation'', a 1977 novel by Goh Poh Seng

*''Dance Dance Immolation'', an interactive per ...

of Jordanian pilot Muath Al-Kasasbeh

Muath Safi Yousef al-Kasasbeh ( ar, معاذ صافي يوسف الكساسبة, Muʿaḏ Ṣāfī Yūsuf al-Kasāsibah South Levantine pronunciation: ; 29 May 1988 – 3 January 2015) was a Royal Jordanian Air Force pilot who was captur ...

.

Lebanon

Lebanon hanged two men in 1998 for murdering a man and his sister. However, capital punishment ended up being altogether suspended in Lebanon, as a result of staunch opposition by activists and some political factions.Liberia

On 16 February 1979, seven men convicted of theritual killing

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized, ...

of the popular Kru traditional singer Moses Tweh, were publicly hanged at dawn in Harper

Harper may refer to:

Names

* Harper (name), a surname and given name

Places

;in Canada

* Harper Islands, Nunavut

*Harper, Prince Edward Island

;In the United States

*Harper, former name of Costa Mesa, California in Orange County

* Harper, Il ...

.

Malaysia

Hanging is the traditional method of capital punishment in Malaysia and has been used to execute people convicted of murder and drug trafficking. TheBarlow and Chambers execution

The Barlow and Chambers executions were the hangings on 7 July 1986 by Malaysia of two Westerners, Kevin John Barlow (Australian and British) and Brian Geoffrey Shergold Chambers (Australian) of Perth, Western Australia, for transporting 14 ...

was carried out as a result of new tighter drug regulations.

Portugal

The last person executed by hanging in Portugal was Francisco Matos Lobos on 16 April 1842. Before that, it had been a common death penalty.Pakistan

In Pakistan, hanging is the most common form of execution.Russia

Hanging was commonly practised in theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

during the rule of the Romanov Dynasty

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to ...

as an alternative to impalement

Impalement, as a method of torture and execution, is the penetration of a human by an object such as a stake, pole, spear, or hook, often by the complete or partial perforation of the torso. It was particularly used in response to "crimes aga ...

, which was used in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Hanging was abolished in 1868 by Alexander II after serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

, but was restored by the time of his death and his assassins were hanged. While those sentenced to death for murder were usually pardoned and sentences commuted to life imprisonment, those guilty of high treason were usually executed. This also included the Grand Duchy of Finland

The Grand Duchy of Finland ( fi, Suomen suuriruhtinaskunta; sv, Storfurstendömet Finland; russian: Великое княжество Финляндское, , all of which literally translate as Grand Principality of Finland) was the predecessor ...

and Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Królestwo Polskie; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a state in Central Europe. It may refer to:

Historical political entities

*Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom existing from 1025 to 1031

*Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom exist ...

under the Russian crown. Taavetti Lukkarinen

Taavetti Lukkarinen (8 November 1884 in Nilsiä – 2 October 1916 in Oulu) was a former Kemi Oy's foreman from Keminmaa, Finland, who was sentenced to death for treason after helping German prisoners of war who had fled the Kirov Railway construc ...

became the last Finn to be executed this way. He was hanged for espionage and high treason in 1916.

The hanging was usually performed by short drop in public. The gallows were usually either a stout nearby tree branch, as in the case of Lukkarinen, or a makeshift gallows constructed for the purpose.

After the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

in 1917, capital punishment was, on paper, abolished, but continued to be used unabated against people perceived to be enemies of the regime. Under the Bolsheviks, most executions were performed by shooting, either by firing squad or by a single firearm. In 1943, hanging was restored primarily for German servicemen and native collaborators for atrocities committed against Soviet POWs and civilians. The last to be hanged were Andrey Vlasov

Andrey Andreyevich Vlasov (russian: Андрéй Андрéевич Влáсов, – August 1, 1946) was a Soviet Red Army general and Nazi collaborator. During World War II, he fought in the Battle of Moscow and later was captured att ...

and his companions in 1946.

Singapore

InSingapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

, long-drop hanging is currently used as a mandatory punishment for crimes such as drug trafficking

A drug is any chemical substance that causes a change in an organism's physiology or psychology when consumed. Drugs are typically distinguished from food and substances that provide nutritional support. Consumption of drugs can be via insuffla ...

, murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person wit ...

and some types of kidnapping

In criminal law, kidnapping is the unlawful confinement of a person against their will, often including transportation/asportation. The asportation and abduction element is typically but not necessarily conducted by means of force or fear: the p ...

. It has also been used for punishing those convicted of unauthorised discharging of firearms.

Sri Lanka

Hanging was abolished inSri Lanka