Hanford nuclear site on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the

The Hanford Site occupies roughly equivalent to half the total area of

The Hanford Site occupies roughly equivalent to half the total area of

National Register of Historic Places.)

/ref> In 1855

The

The

The construction workforce peaked at 45,096 on June 21, 1944. About thirteen percent were women, and non-whites made up 16.45 percent. African-Americans lived in segregated quarters, had their own

The construction workforce peaked at 45,096 on June 21, 1944. About thirteen percent were women, and non-whites made up 16.45 percent. African-Americans lived in segregated quarters, had their own

Construction of the nuclear facilities proceeded rapidly. Before the end of the war in August 1945, the HEW built 554 buildings at Hanford, including three nuclear reactors (105B, 105D, and 105F) and three plutonium processing plants (221T, 221B, and 221U). The project required of roads, of railway, and four electrical substations. The HEW used of concrete and of structural steel.

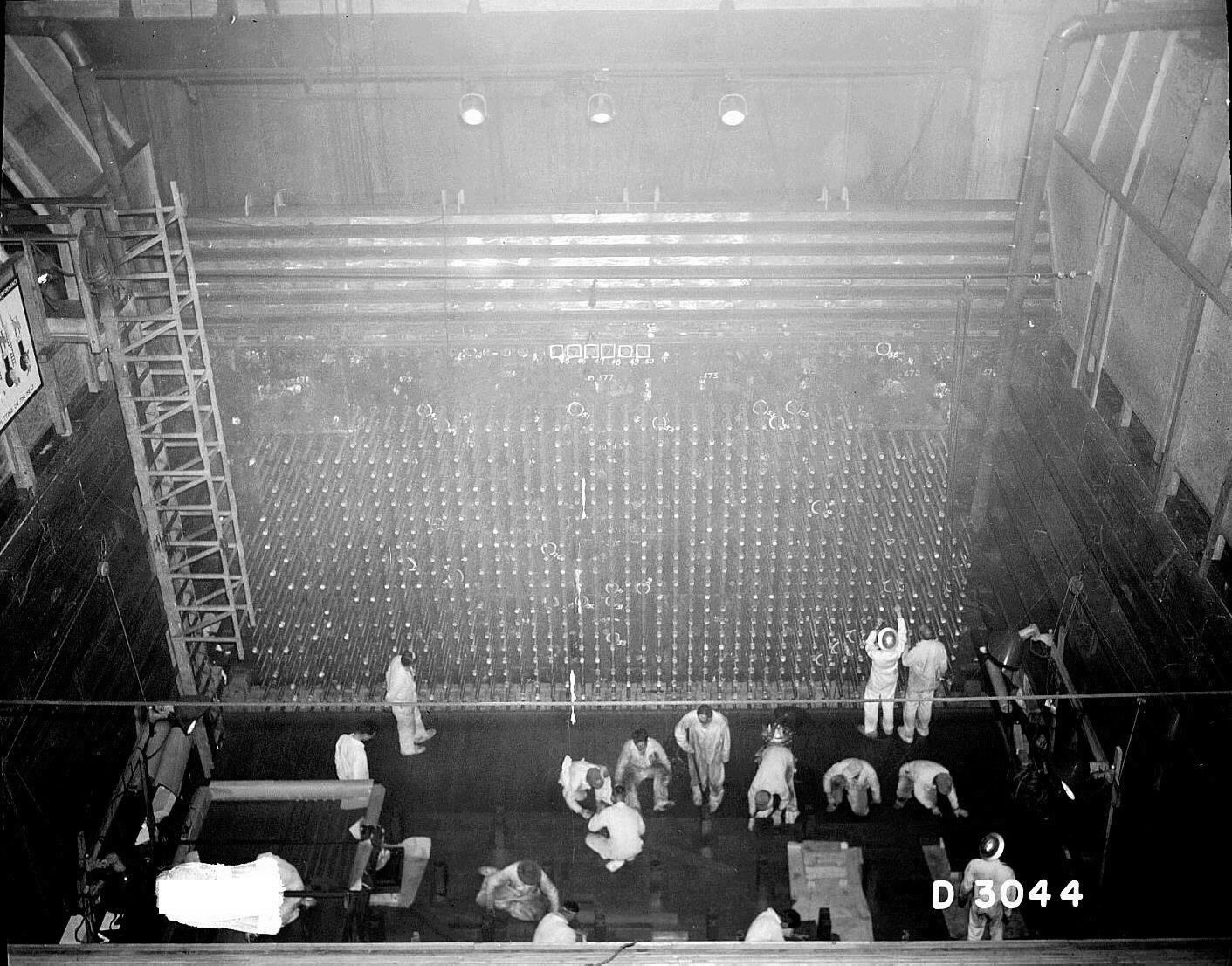

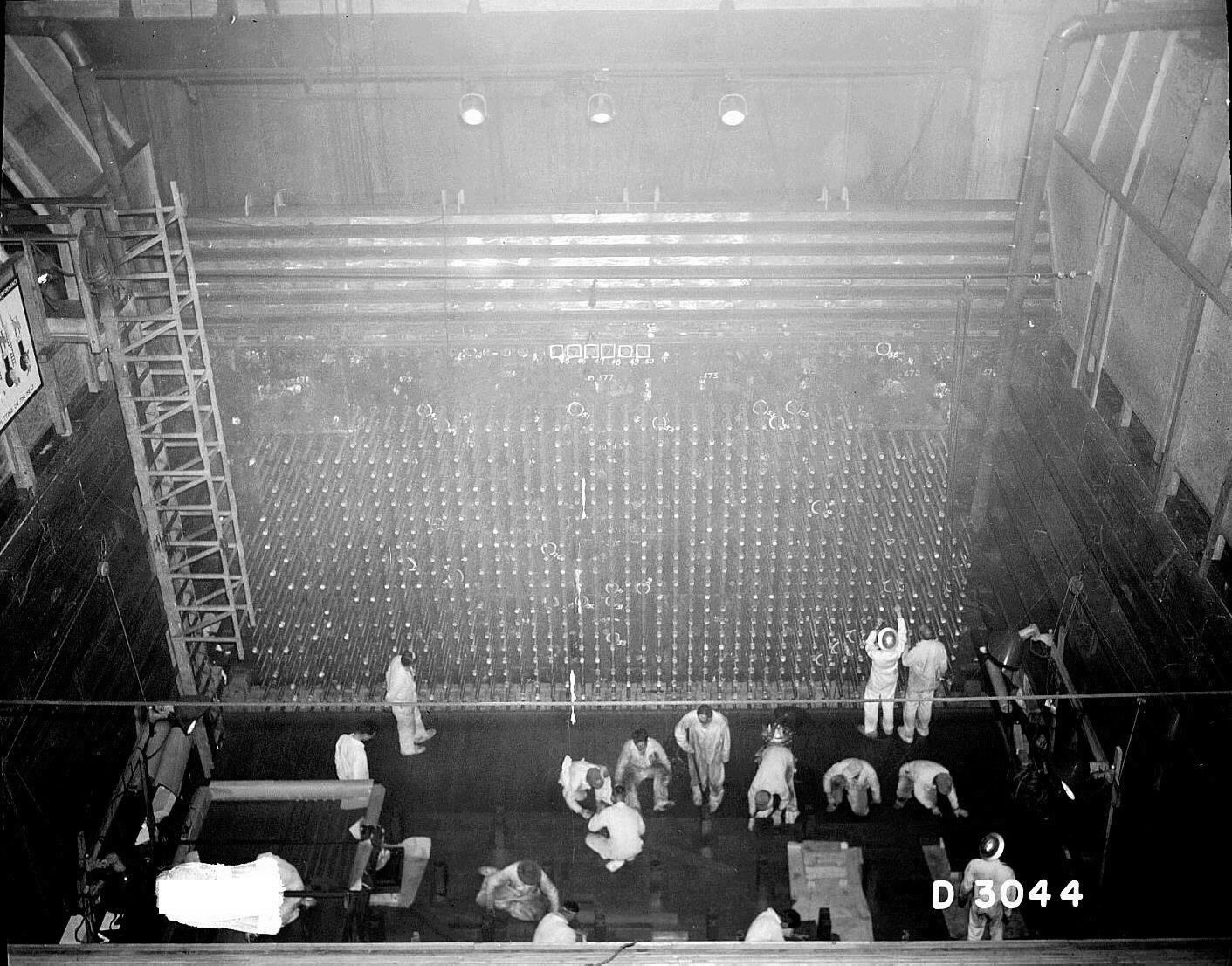

Construction on B Reactor commenced in August 1943 and was completed on September 13, 1944. The reactor went

Construction of the nuclear facilities proceeded rapidly. Before the end of the war in August 1945, the HEW built 554 buildings at Hanford, including three nuclear reactors (105B, 105D, and 105F) and three plutonium processing plants (221T, 221B, and 221U). The project required of roads, of railway, and four electrical substations. The HEW used of concrete and of structural steel.

Construction on B Reactor commenced in August 1943 and was completed on September 13, 1944. The reactor went

Irradiated fuel slugs were transported by rail to huge remotely operated chemical separation plants about away on a special railroad car operated by remote control. The separation buildings were massive windowless concrete structures, long, high and wide, with concrete walls thick. Inside the buildings were canyons and galleries where a series of chemical processing steps separated the small amount of plutonium from the remaining uranium and

Irradiated fuel slugs were transported by rail to huge remotely operated chemical separation plants about away on a special railroad car operated by remote control. The separation buildings were massive windowless concrete structures, long, high and wide, with concrete walls thick. Inside the buildings were canyons and galleries where a series of chemical processing steps separated the small amount of plutonium from the remaining uranium and

Although the reactors could be shut down in two-and-a-half seconds, the decay of fission products meant that they would still generate heat due to the decay of fission products. It was therefore vital that the flow of water should not cease. If the power failed, the steam pumps would automatically cut in and continue to deliver water at full capacity for long enough to allow an orderly shutdown. This occurred on March 10, 1945, when a Japanese balloon bomb struck a high-tension line between Grand Coulee and Bonneville. This caused an electrical surge in the lines to the reactors. A

Although the reactors could be shut down in two-and-a-half seconds, the decay of fission products meant that they would still generate heat due to the decay of fission products. It was therefore vital that the flow of water should not cease. If the power failed, the steam pumps would automatically cut in and continue to deliver water at full capacity for long enough to allow an orderly shutdown. This occurred on March 10, 1945, when a Japanese balloon bomb struck a high-tension line between Grand Coulee and Bonneville. This caused an electrical surge in the lines to the reactors. A

The other problem was that the bismuth phosphate process used to separate the plutonium left the uranium in an unrecoverable state. The Metallurgical Laboratory had researched a promising new

The other problem was that the bismuth phosphate process used to separate the plutonium left the uranium in an unrecoverable state. The Metallurgical Laboratory had researched a promising new  While this was being considered by the AEC, GE experimented with annealing, and found that if the reactors were run at and then slowly cooled, the graphite's crystalline structure could be restored. The reactors could be run at higher temperatures by increasing the power level. Some helium in the atmosphere surrounding the reactors was replaced with

While this was being considered by the AEC, GE experimented with annealing, and found that if the reactors were run at and then slowly cooled, the graphite's crystalline structure could be restored. The reactors could be run at higher temperatures by increasing the power level. Some helium in the atmosphere surrounding the reactors was replaced with

The adult population of Richland had an average education of 12.5 years, and 40 percent of the men had attended college, compared with 22 percent in the state of Washington as a whole, and the median annual family income in 1959 was compared with . In 1950 26 percent of American families had an annual income of less than the

The adult population of Richland had an average education of 12.5 years, and 40 percent of the men had attended college, compared with 22 percent in the state of Washington as a whole, and the median annual family income in 1959 was compared with . In 1950 26 percent of American families had an annual income of less than the  Soon after taking over from the Army, the AEC had contemplated the future of the communities of Richland, Oak Ridge and Los Alamos. The commissioners were eager to divest the AEC of the burden of their management. In 1947 AEC general manager

Soon after taking over from the Army, the AEC had contemplated the future of the communities of Richland, Oak Ridge and Los Alamos. The commissioners were eager to divest the AEC of the burden of their management. In 1947 AEC general manager

The Soviet Union detonated its

The Soviet Union detonated its

The U Plant was modified to use the REDOX process to recover uranium from the wastes left over from the bismuth phosphate process, but with a different solvent,

The U Plant was modified to use the REDOX process to recover uranium from the wastes left over from the bismuth phosphate process, but with a different solvent,

By 1963 the AEC had estimated that it had sufficient plutonium for its needs for the foreseeable future, and planned to shut down the production reactors. To mitigate the economic impact, closures were carried out over a period of six years. The change of policy was not publicly announced; instead, each round of closures was accompanied by a statement that production needs could be met by the remaining facilities. The first round of closures was announced by President

By 1963 the AEC had estimated that it had sufficient plutonium for its needs for the foreseeable future, and planned to shut down the production reactors. To mitigate the economic impact, closures were carried out over a period of six years. The change of policy was not publicly announced; instead, each round of closures was accompanied by a statement that production needs could be met by the remaining facilities. The first round of closures was announced by President  All but one of the Hanford production reactors were entombed ("cocooned") to allow the radioactive materials to decay, and the surrounding structures removed and buried. This involved the removal of hundreds of tons of asbestos, concrete, steel and contaminated soil. The pumps and tunnels were dug up and razed, as were the auxiliary buildings. What was left were the core and shields. These were sealed up and a sloped steel roof added to draw off rainwater. Cocooning of CReactor commenced in 1996, and was completed in 1998. DReactor followed in 2002, FReactor followed in 2003, DRReactor in 2004. and HReactor in 2005. N Reactor was cocooned in 2012, and KE and KW in 2022.

The exception was B Reactor, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992.NRHP site #92000245. (See also the commercial sit

All but one of the Hanford production reactors were entombed ("cocooned") to allow the radioactive materials to decay, and the surrounding structures removed and buried. This involved the removal of hundreds of tons of asbestos, concrete, steel and contaminated soil. The pumps and tunnels were dug up and razed, as were the auxiliary buildings. What was left were the core and shields. These were sealed up and a sloped steel roof added to draw off rainwater. Cocooning of CReactor commenced in 1996, and was completed in 1998. DReactor followed in 2002, FReactor followed in 2003, DRReactor in 2004. and HReactor in 2005. N Reactor was cocooned in 2012, and KE and KW in 2022.

The exception was B Reactor, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992.NRHP site #92000245. (See also the commercial sit

National Register of Historic Places

) Some historians advocated converting it into a museum. It was designated a

When GE announced that it was ending the contract to run the Hanford Site in 1963, the AEC decided to separate the contract among multiple operators. The contract to run the research laboratory at the Hanford Site was awarded to the

When GE announced that it was ending the contract to run the Hanford Site in 1963, the AEC decided to separate the contract among multiple operators. The contract to run the research laboratory at the Hanford Site was awarded to the

The Hanford Reach was preserved as the finest salmon breeding ground in the Pacific Northwest. The end of plutonium production at the Hanford Site meant that it no longer required the areas around the old production sites. On June 9, 2000, President

The Hanford Reach was preserved as the finest salmon breeding ground in the Pacific Northwest. The end of plutonium production at the Hanford Site meant that it no longer required the areas around the old production sites. On June 9, 2000, President

The plutonium separation process resulted in the release of radioactive isotopes into the air, which were carried by the wind throughout southeastern Washington and into parts of

The plutonium separation process resulted in the release of radioactive isotopes into the air, which were carried by the wind throughout southeastern Washington and into parts of  Of the 177 tanks at Hanford, 149 had a single shell. Historically single-shell tanks were used for storing radioactive liquid waste and designed to last twenty years. By 2005 some liquid waste was transferred from single-shell tanks to (safer) double-shell tanks. A substantial amount of residue remains in the older single-shell tanks with one containing an estimated of radioactive sludge, for example. It is believed that up to six of these "empty" tanks were leaking. Two tanks were reportedly leaking per year each, while the remaining four tanks were each leaking per year. In February 2013 Washington Governor

Of the 177 tanks at Hanford, 149 had a single shell. Historically single-shell tanks were used for storing radioactive liquid waste and designed to last twenty years. By 2005 some liquid waste was transferred from single-shell tanks to (safer) double-shell tanks. A substantial amount of residue remains in the older single-shell tanks with one containing an estimated of radioactive sludge, for example. It is believed that up to six of these "empty" tanks were leaking. Two tanks were reportedly leaking per year each, while the remaining four tanks were each leaking per year. In February 2013 Washington Governor

Decades of manufacturing left behind of

Decades of manufacturing left behind of  The cleanup effort was managed by the DOE under the oversight of the two regulatory agencies. A citizen-led Hanford Advisory Board provides recommendations from community stakeholders, including local and state governments, regional environmental organizations, business interests, and Native American tribes. Citing the 2014 Hanford Lifecycle Scope Schedule and Cost report, the 2014 estimated cost of the remaining Hanford cleanup is $113.6billionmore than $3billion per year for the next six years, with a lower cost projection of approximately $2billion per year until 2046. About eleven thousand workers were on site to consolidate, clean up, and mitigate waste, contaminated buildings, and contaminated soil. Originally scheduled to be complete within thirty years, the cleanup was less than half finished by 2008. Of the four areas that were formally listed as

The cleanup effort was managed by the DOE under the oversight of the two regulatory agencies. A citizen-led Hanford Advisory Board provides recommendations from community stakeholders, including local and state governments, regional environmental organizations, business interests, and Native American tribes. Citing the 2014 Hanford Lifecycle Scope Schedule and Cost report, the 2014 estimated cost of the remaining Hanford cleanup is $113.6billionmore than $3billion per year for the next six years, with a lower cost projection of approximately $2billion per year until 2046. About eleven thousand workers were on site to consolidate, clean up, and mitigate waste, contaminated buildings, and contaminated soil. Originally scheduled to be complete within thirty years, the cleanup was less than half finished by 2008. Of the four areas that were formally listed as

The most significant challenge is stabilizing the of high-level radioactive waste stored in the 177 underground tanks. By 1998 about a third of these tanks had leaked waste into the soil and groundwater. By 2008 most of the liquid waste had been transferred to more secure double-shelled tanks; however, of liquid waste, together with of salt cake and sludge, remains in the single-shelled tanks. DOE lacks information about the extent to which the 27 double-shell tanks may be susceptible to corrosion. Without determining the extent to which the factors that contributed to the leak in AY102 were similar to the other 27 double-shell tanks, DOE could not be sure how long its double-shell tanks can safely store waste. That waste was originally scheduled to be removed by 2018. By 2008 the revised deadline was 2040. By 2008 of radioactive waste was traveling through the groundwater toward the Columbia River. This waste was expected to reach the river in twelve to fifty years if cleanup does not proceed on schedule.

Under the Tri-Party Agreement, lower-level hazardous wastes are buried in huge lined pits that will be sealed and monitored with sophisticated instruments for many years. Disposal of plutonium and other high-level wastes is a more difficult problem that continues to be a subject of intense debate. As an example, plutonium239 has a half-life of 24,100 years, and a decay of ten half-lives is required before a sample is considered to cease its radioactivity. In 2000 the DOE awarded a $4.3billion contract to

The most significant challenge is stabilizing the of high-level radioactive waste stored in the 177 underground tanks. By 1998 about a third of these tanks had leaked waste into the soil and groundwater. By 2008 most of the liquid waste had been transferred to more secure double-shelled tanks; however, of liquid waste, together with of salt cake and sludge, remains in the single-shelled tanks. DOE lacks information about the extent to which the 27 double-shell tanks may be susceptible to corrosion. Without determining the extent to which the factors that contributed to the leak in AY102 were similar to the other 27 double-shell tanks, DOE could not be sure how long its double-shell tanks can safely store waste. That waste was originally scheduled to be removed by 2018. By 2008 the revised deadline was 2040. By 2008 of radioactive waste was traveling through the groundwater toward the Columbia River. This waste was expected to reach the river in twelve to fifty years if cleanup does not proceed on schedule.

Under the Tri-Party Agreement, lower-level hazardous wastes are buried in huge lined pits that will be sealed and monitored with sophisticated instruments for many years. Disposal of plutonium and other high-level wastes is a more difficult problem that continues to be a subject of intense debate. As an example, plutonium239 has a half-life of 24,100 years, and a decay of ten half-lives is required before a sample is considered to cease its radioactivity. In 2000 the DOE awarded a $4.3billion contract to  In May 2007 state and federal officials began closed-door negotiations about the possibility of extending legal cleanup deadlines for waste vitrification in exchange for shifting the focus of the cleanup to urgent priorities, such as

In May 2007 state and federal officials began closed-door negotiations about the possibility of extending legal cleanup deadlines for waste vitrification in exchange for shifting the focus of the cleanup to urgent priorities, such as

Federal agency

that regulates Hanford cleanup

State agency

that regulates Hanford cleanup *

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

. The site has been known by many names, including SiteW and the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. Established in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, the site was home to the Hanford Engineer Works

The Hanford Engineer Works was a nuclear production complex established by the United States federal government in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project during World War II. The site, located at the Hanford Site on the Columbia River in Bento ...

and B Reactor, the first full-scale plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

production reactor in the world. Plutonium manufactured at the site was used in the first atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

, which was tested in the Trinity nuclear test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert abo ...

, and in the Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

bomb that was used in the bombing of Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the on ...

.

During the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, the project expanded to include nine nuclear reactors and five large plutonium processing complexes, which produced plutonium for most of the more than sixty thousand weapons built for the U.S. nuclear arsenal. Nuclear technology

Nuclear technology is technology that involves the nuclear reactions of atomic nuclei. Among the notable nuclear technologies are nuclear reactors, nuclear medicine and nuclear weapons. It is also used, among other things, in smoke detectors an ...

developed rapidly during this period, and Hanford scientists produced major technological achievements. Many early safety procedures and waste disposal practices were inadequate, resulting in the release of significant amounts of radioactive materials into the air and the Columbia River.

The weapons production reactors were decommissioned at the end of the Cold War, and the Hanford Site became the focus of the nation's largest environmental cleanup

Environmental remediation deals with the removal of pollution or contaminants from environmental media such as soil, groundwater, sediment, or surface water. Remedial action is generally subject to an array of regulatory requirements, and may also ...

. Besides the cleanup project, Hanford hosted a commercial nuclear power plant, the Columbia Generating Station

Columbia Generating Station is a nuclear commercial energy facility located on the Hanford Site, north of Richland, Washington. It is owned and operated by Energy Northwest, a Washington state, not-for-profit joint operating agency. Licensed by ...

, and various centers for scientific research and development, such as the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) is one of the United States Department of Energy national laboratories, managed by the Department of Energy's (DOE) Office of Science. The main campus of the laboratory is in Richland, Washington.

O ...

, the Fast Flux Test Facility

The Fast Flux Test Facility (FFTF) is a 400 MW thermal, liquid sodium cooled, nuclear test reactor owned by the U.S. Department of Energy.

It does not generate electricity. It is situated in the ''400 Area'' of the Hanford Site, which is located ...

and the LIGO Hanford Observatory. In 2015 it was designated as part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park

Manhattan Project National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park commemorating the Manhattan Project that is run jointly by the National Park Service and United States Department of Energy, Department of Energy. The park co ...

.

Geography

The Hanford Site occupies roughly equivalent to half the total area of

The Hanford Site occupies roughly equivalent to half the total area of Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

within Benton County, Washington

Benton County is a county in the south-central portion of the U.S. state of Washington. As of the 2020 census, its population was 206,873. The county seat is Prosser, and its largest city is Kennewick. The Columbia River demarcates the coun ...

. This land is closed to the general public. It is a desert

A desert is a barren area of landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions are hostile for plant and animal life. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About on ...

environment receiving less than of annual precipitation, covered mostly by shrub-steppe vegetation. The Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

flows along the site for approximately , forming its northern and eastern boundary. The Columbia and Yakima River

The Yakima River is a tributary of the Columbia River in south central and eastern Washington state, named for the indigenous Yakama people. Lewis and Clark mention in their journals that the Chin-nâm pam (or the Lower Snake River Chamnapam Nat ...

s contain salmon

Salmon () is the common name for several list of commercially important fish species, commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the family (biology), family Salmonidae, which are native to tributary, tributaries of the ...

, sturgeon

Sturgeon is the common name for the 27 species of fish belonging to the family Acipenseridae. The earliest sturgeon fossils date to the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretace ...

, steelhead trout

Steelhead, or occasionally steelhead trout, is the common name of the anadromous form of the coastal rainbow trout or redband trout (O. m. gairdneri). Steelhead are native to cold-water tributaries of the Pacific basin in Northeast Asia and N ...

and bass

Bass or Basses may refer to:

Fish

* Bass (fish), various saltwater and freshwater species

Music

* Bass (sound), describing low-frequency sound or one of several instruments in the bass range:

** Bass (instrument), including:

** Acoustic bass gui ...

, and wildlife in the area includes skunk

Skunks are mammals in the family Mephitidae. They are known for their ability to spray a liquid with a strong, unpleasant scent from their anal glands. Different species of skunk vary in appearance from black-and-white to brown, cream or ginge ...

s, muskrat

The muskrat (''Ondatra zibethicus'') is a medium-sized semiaquatic rodent native to North America and an introduced species in parts of Europe, Asia, and South America. The muskrat is found in wetlands over a wide range of climates and habitat ...

s, coyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans'') is a species of canis, canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the wolf, and slightly smaller than the closely related eastern wolf and red wolf. It fills much of the same ecologica ...

s, raccoon

The raccoon ( or , ''Procyon lotor''), sometimes called the common raccoon to distinguish it from other species, is a mammal native to North America. It is the largest of the procyonid family, having a body length of , and a body weight of ...

s, deer, eagles, hawks and owls. The flora includes sagebrush

Sagebrush is the common name of several woody and herbaceous species of plants in the genus ''Artemisia''. The best known sagebrush is the shrub ''Artemisia tridentata''. Sagebrushes are native to the North American west.

Following is an alph ...

, bitterbrush

''Purshia'' (bitterbrush or cliff-rose) is a small genus of 5–8 species of flowering plants in the family Rosaceae which are native to western North America.

Description

''Purshia'' species form deciduous or evergreen shrubs, typically reach ...

, a variety of grasses, prickly pear and willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, from the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 400 speciesMabberley, D.J. 1997. The Plant Book, Cambridge University Press #2: Cambridge. of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist s ...

.

The original site was and included buffer areas across the river in Grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

*Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

*Grant, Inyo County, C ...

and Franklin

Franklin may refer to:

People

* Franklin (given name)

* Franklin (surname)

* Franklin (class), a member of a historical English social class

Places Australia

* Franklin, Tasmania, a township

* Division of Franklin, federal electoral d ...

counties. Some of this land has been returned to private use and is now covered with orchards, vineyards, and irrigated fields. The site is bordered on the southeast by the TriCities

Twin cities are a special case of two neighboring cities or urban centres that grow into a single conurbation – or narrowly separated urban areas – over time. There are no formal criteria, but twin cities are generally comparable in stat ...

, a metropolitan area composed of Richland, Kennewick

Kennewick () is a city in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington. It is located along the southwest bank of the Columbia River, just southeast of the confluence of the Columbia and Yakima rivers and across from the confluence of the C ...

, Pasco, and smaller communities, and home to nearly 300,000 residents. Hanford is a primary economic base for these cities. In 2000 large portions of the original site were turned over to the Hanford Reach National Monument

The Hanford Reach National Monument is a national monument in the U.S. state of Washington. It was created in 2000, mostly from the former security buffer surrounding the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. The area has been untouched by development or ...

. The remainder was divided by function into three main areas: the nuclear reactors were located along the river in an area designated as the 100Area; the chemical separations complexes were located inland in the Central Plateau, designated as the 200Area; and various support facilities were located in the southeast corner of the site, designated as the 300 Area.

Climate

Hanford is the site of Washington state's highest recorded temperature of , reached on June 29, 2021.Early history

The confluence of theYakima

Yakima ( or ) is a city in and the county seat of Yakima County, Washington, and the state's 11th-largest city by population. As of the 2020 census, the city had a total population of 96,968 and a metropolitan population of 256,728. The uninco ...

, Snake

Snakes are elongated, Limbless vertebrate, limbless, carnivore, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other Squamata, squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping Scale (zoology), scales. Ma ...

, and Columbia rivers has been a meeting place for native peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

for centuries. The archaeological record of Native American habitation of this area stretches back over ten thousand years. Tribes and nations including the Yakama

The Yakama are a Native American tribe with nearly 10,851 members, based primarily in eastern Washington state.

Yakama people today are enrolled in the federally recognized tribe, the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. Their Yak ...

, Nez Perce

The Nez Percé (; autonym in Nez Perce language: , meaning "we, the people") are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who are presumed to have lived on the Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest region for at least 11,500 years.Ames, K ...

, and Umatilla used the area for hunting, fishing, and gathering plant foods. Archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

s have identified numerous Native American sites, including "pit house villages, open campsites, fish farming sites, hunting/kill sites, game drive complexes, quarries, and spirit quest sites", and two archaeological sites were listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

in 1976.Hanford Island Archaeological Site (NRHP #76001870) and Hanford North Archaeological District (NRHP #76001871). (See also the commercial sitNational Register of Historic Places.)

/ref> In 1855

Isaac Stevens

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (March 25, 1818 – September 1, 1862) was an American military officer and politician who served as governor of the Territory of Washington from 1853 to 1857, and later as its delegate to the United States House of Represen ...

, the governor of the Territory of Washington

The Territory of Washington was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

, negotiated with the Native American tribes to establish a reservation system. Treaties were signed, but were often ignored, as the reservation system was not compatible with their traditional food-gathering or family groupings. In September 1858 a military expedition under Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

George Wright George Wright may refer to:

Politics, law and government

* George Wright (MP) (died 1557), MP for Bedford and Wallingford

* George Wright (governor) (1779–1842), Canadian politician, lieutenant governor of Prince Edward Island

* George Wright ...

defeated the Native American tribes in the Battle of Spokane Plains

The Battle of Spokane Plains was a battle during the Coeur d'Alene War of 1858 in the Washington Territory (now the states of Washington and Idaho) in the United States. The Coeur d'Alene War was part of the Yakima War, which began in 1855. The b ...

to force compliance with the reservation system. Nonetheless, Native American use of the area continued into the 20th century. The Wanapum

The Wanapum tribe of Native Americans formerly lived along the Columbia River from above Priest Rapids down to the mouth of the Snake River in what is now the US state of Washington. About 60 Wanapum still live near the present day site of Priest ...

people were never forced onto a reservation, and they lived along the Columbia River in the Priest Rapids Valley until 1943.

After gold was discovered in British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

, prospectors explored the Columbia River basin in search of gold, but with little success. Walla Walla Walla Walla can refer to:

* Walla Walla people, a Native American tribe after which the county and city of Walla Walla, Washington, are named

* Place of many rocks in the Australian Aboriginal Wiradjuri language, the origin of the name of the town ...

, which had been established as a military post in 1858, became a center for mining supplies, and a general store was established at White Bluffs. A ranch was established in Yakima Valley by Ben Snipes in 1859, and the Northern Pacific Railroad

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by 38th United States Congress, Congress in 1864 and given ...

was extended into the area, beginning in 1879. Railroad engineers founded the towns of Kennewick and Pasco. Settlers moved into the region, initially along the Columbia River south of Priest Rapids. They established farms and orchards supported by small-scale irrigation projects, but most went bankrupt in the Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

. The Reclamation Act of 1902

The Reclamation Act (also known as the Lowlands Reclamation Act or National Reclamation Act) of 1902 () is a United States federal law that funded irrigation projects for the arid lands of 20 states in the American West.

The act at first covere ...

provided for federal government participation in the financing of irrigation projects, and the population began expanding again, with small town centers at Hanford, White Bluffs and Richland established between 1905 and 1910. The Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

of the 1930s decreased the price of agricultural commodities and many farms were foreclosed or abandoned. The economy was supported by the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam

Grand Coulee Dam is a concrete gravity dam on the Columbia River in the U.S. state of Washington, built to produce hydroelectric power and provide irrigation water. Constructed between 1933 and 1942, Grand Coulee originally had two powerhous ...

between 1933 and 1942, and the establishment of the Naval Air Station Pasco in 1942.

Manhattan Project

Contractor selection

DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the S-1 Section

The S-1 Executive Committee laid the groundwork for the Manhattan Project by initiating and coordinating the early research efforts in the United States, and liaising with the Tube Alloys Project in Britain.

In the wake of the discovery of nucle ...

of the federal Office of Scientific Research and Development

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May 1 ...

(OSRD) sponsored a research project on plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

. Research was conducted by scientists at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

Metallurgical Laboratory

The Metallurgical Laboratory (or Met Lab) was a scientific laboratory at the University of Chicago that was established in February 1942 to study and use the newly discovered chemical element plutonium. It researched plutonium's chemistry and m ...

. At the time, plutonium was a rare element that had only recently been synthesized in laboratories. It was theorized that plutonium was fissile

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be typ ...

and could be used in an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

. The United States government was concerned that Germany was developing a nuclear weapons program. The Metallurgical Laboratory physicists worked on designing nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

s ("piles") that could irradiate uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

and transmute it into plutonium. Meanwhile, chemists investigated ways to separate plutonium from uranium.

In September 1942 Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Leslie R. Groves Jr.

Lieutenant general (United States), Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers Officer (armed forces), officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and di ...

became the director of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, as it came to be known. The project to build industrial-size plants for the manufacture of plutonium was codenamed the X10 project. Groves engaged DuPont

DuPont de Nemours, Inc., commonly shortened to DuPont, is an American multinational chemical company first formed in 1802 by French-American chemist and industrialist Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours. The company played a major role in ...

, a firm he had worked with in the past on the construction of explosives plants, to design, construct and operate the plutonium manufacturing complex. To avoid being labeled as merchants of death

Merchants of death was an epithet used in the U.S. in the 1930s to attack industries and banks that had supplied and funded World War I (then called the Great War).

Origin

The term originated in 1932 as the title of an article about an arms d ...

, as the company had been after World WarI, DuPont's executive committee insisted that it should receive no payment. For legal reasons, a Cost Plus Fixed Fee

A cost-plus contract, also termed a cost plus contract, is a contract such that a contractor is paid for all of its allowed expenses, ''plus'' additional payment to allow for a profit.Walter S. Carpenter Jr.

Walter Samuel Carpenter Jr. (January 8, 1888 – February 2, 1976) was an American corporate executive from Wilmington, Delaware, who oversaw the DuPont company's involvement in the Manhattan Project to produce an atomic bomb for use during Wo ...

, was given assurances that the government was assuming all responsibility for the hazards involved in the project.

Site selection

Carpenter expressed reservations about building the reactors atOak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson and Roane counties in the eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville. Oak Ridge's population was 31,402 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Knoxville Metropolitan Area. Oak ...

; with Knoxville

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the state's ...

only away, a catastrophic accident might result in loss of life and severe health effects. Even a less deadly accident might disrupt vital war production, particularly of aluminum, and force the evacuation of the Manhattan Project's isotope separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" n ...

plants. Spreading the facilities at Oak Ridge out more would require the purchase of more land and the expansion needed was still uncertain; for planning purposes, six reactors and four chemical separation plants were envisioned.

The ideal site was described by eight criteria:

#A clean and abundant water supply (at least )

#A large electric power supply (about 100,000 KW)

#A "hazardous manufacturing area" of at least

#Space for laboratory facilities at least from the nearest reactor or separations plant

#The employees' village no less than upwind of the plant

#No towns of more than a thousand people closer than from the hazardous rectangle

#No main highway, railway, or employee village closer than from the hazardous rectangle

#Ground that could bear heavy loads

The most important of these criteria was the availability of electric power. The needs of war industries had created power shortages in many parts of the country, and use of the Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolina ...

(TVA) was ruled out because the Clinton Engineer Works

The Clinton Engineer Works (CEW) was the production installation of the Manhattan Project that during World War II produced the enriched uranium used in the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima, as well as the first examples of reactor-produced plutoni ...

was expected to use up all its surplus power. This led to consideration of alternative sites in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

and Southwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

, where there was surplus electrical power. Between December 18 and 31, 1942, just twelve days after the Metallurgical Laboratory team led by Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

started up Chicago Pile 1, the first nuclear reactor, a three-man party consisting of Colonel Franklin T. Matthias

Franklin Thompson Matthias (13 March 1908 – 3 December 1993) was an American civil engineer who directed the construction of the Hanford nuclear site, a key facility of the Manhattan Project during World War II.

A graduate of the University o ...

and DuPont engineers A. E. S. Hall and Gilbert P. Church inspected the most promising potential sites. Matthias reported to Groves that the Hanford Site was "far more favorable in virtually all respects than any other"; the survey party was particularly impressed by the fact that a high-voltage power line from Grand Coulee Dam to Bonneville Dam

Bonneville Lock and Dam consists of several run-of-the-river dam structures that together complete a span of the Columbia River between the U.S. states of Oregon and Washington at River Mile 146.1. The dam is located east of Portland, Oregon, ...

ran through the site, and there was an electrical substation

A substation is a part of an electrical generation, transmission, and distribution system. Substations transform voltage from high to low, or the reverse, or perform any of several other important functions. Between the generating station and ...

on its edge. Groves visited the site on January 16, 1943, and approved the selection. The facility became known as the Hanford Engineer Works

The Hanford Engineer Works was a nuclear production complex established by the United States federal government in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project during World War II. The site, located at the Hanford Site on the Columbia River in Bento ...

(HEW), and the site was codenamed SiteW.

Land acquisition

The

The Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and D ...

, authorized the acquisition of the land on February 8, 1943. A Manhattan District project office opened in Prosser, Washington

Prosser () is a city in and the county seat of Benton County, Washington, United States. Situated along the Yakima River, it had a population of 5,714 at the 2010 census.

History

Prosser was long home to Native Americans who lived and fished a ...

, on February 22, and the Washington Title Insurance Company opened an office there to furnish title

A title is one or more words used before or after a person's name, in certain contexts. It may signify either generation, an official position, or a professional or academic qualification. In some languages, titles may be inserted between the f ...

certificates. Federal Judge Lewis B. Schwellenbach

Lewis Baxter Schwellenbach (September 20, 1894 – June 10, 1948) was a United States senator from Washington, a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Washington and the 5th United States Secr ...

issued an order of possession under the Second War Powers Act the following day, and the first tract was acquired on March 10. Some 4,218 tracts totaling were to be acquired, making it one of the largest land acquisition projects in American history.

Most of the land (some 88 percent) was sagebrush, where eighteen to twenty thousand sheep grazed. About eleven percent was farmland, although not all was under cultivation. Farmers felt that they should be compensated for the value of the crops they had planted as well as for the land itself. Because construction plans had not yet been drawn up, and work on the site could not immediately commence, Groves decided to postpone the taking of the physical possession of properties under cultivation to allow farmers to harvest the crops they had already planted. This reduced the hardship on the farmers, and avoided the wasting of food at a time when the nation was facing food shortages and the federal government was urging citizens to plant victory garden

Victory gardens, also called war gardens or food gardens for defense, were vegetable, fruit, and herb gardens planted at private residences and public parks in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and Germany during World War I ...

s. The War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* Dep ...

arranged with Federal Prison Industries

Federal Prison Industries, Inc. (FPI), doing business as UNICOR (stylized as unicor) since 1977, is a wholly owned United States government corporation created in 1934 as a prison labor program for inmates within the Federal Bureau of Prisons, a ...

for crops to be harvested by prisoners from the McNeil Island Penitentiary

The McNeil Island Corrections Center (MICC) was a prison in the northwest United States, operated by the Washington State Department of Corrections. It was on McNeil Island in Puget Sound in unincorporated Pierce County, near Steilacoom, Washin ...

.

The harvest in the spring and summer of 1943 was exceptionally good, and high crop prices due to the war greatly increased land prices. It also promoted exaggerated ideas about the value of the land, leading to litigation. Discontent over the acquisition was apparent in letters sent from Hanford Site residents to the War and Justice Department

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

s, and the Truman Committee

The Truman Committee, formally known as the Senate Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, was a United States Congressional investigative body, headed by Senator Harry S. Truman. The bipartisan special committee was form ...

began making inquiries. Stimson met with chairman of the committee, Senator Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

, who agreed to remove the Hanford Site from the committee's investigations on the grounds of national security. Trial juries were sympathetic to the claims of the landowners and the payments awarded were well in excess of the government appraisals. When the Manhattan Project ended on December 31, 1946, there were still 237 tracts remaining to be settled.

About 1,500 residents of Hanford, White Bluffs, and nearby settlements were relocated, as well as the Wanapum people, Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakima Nation

The Yakama Indian Reservation (spelled Yakima until 1994) is a Native American reservation in Washington state of the federally recognized tribe known as the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. The tribe is made up of Klikitat ...

, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation

The Umatilla Indian Reservation is an Indian reservation in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. It was created by The Treaty of June 9, 1855 between the United States and members of the Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla tribes. It lies in nort ...

, and the Nez Perce Tribe. Native Americans were accustomed to fishing in the Columbia River near White Bluffs for two or three weeks in October. The fish they caught was dried and provided food for the winter. They rejected offers of an annual cash payment, and a deal was struck allowing the chief and his two assistants to issue passes to fish at the site. This authority was later revoked for security reasons. Matthias gave assurances that Native American graves would be treated with respect, but it would be fifteen years before the Wanapum people were allowed access to mark the cemeteries. In 1997 the elders were permitted to bring children and young adults onto the site once a year to learn about their sacred sites.

Construction workforce

DuPont advertised for workers in newspapers for an unspecified "war construction project" in southeastern Washington, offering an "attractive scale of wages" and living facilities. Normally for a development in such an isolated area, employees would be accommodated on site, but in this case for security and safety reasons it was desirable to locate them at least away. Even the construction workforce could not be housed on site, because some plant operations would have to be carried out during start-up testing. The Army and DuPont engineers decided to create two communities: a temporary constructions camp and a more substantial operating village. Construction was expedited by locating them on the sites of existing villages to take advantage of the buildings, roads and utility infrastructure already in place. They established the construction camp on the site of the village of Hanford, and the operating village on that of Richland. The construction workforce peaked at 45,096 on June 21, 1944. About thirteen percent were women, and non-whites made up 16.45 percent. African-Americans lived in segregated quarters, had their own

The construction workforce peaked at 45,096 on June 21, 1944. About thirteen percent were women, and non-whites made up 16.45 percent. African-Americans lived in segregated quarters, had their own mess

The mess (also called a mess deck aboard ships) is a designated area where military personnel socialize, eat and (in some cases) live. The term is also used to indicate the groups of military personnel who belong to separate messes, such as the o ...

es and recreation areas, and were paid less than white workers. Three types of accommodation were provided at Hanford: barracks, hutments and trailer parking. The first workers to arrive lived in tents while they erected the first barracks. Barracks construction commenced on April 6, 1943, and eventually 195 barracks were erected: 110 for white men, 21 for black men, 57 for white women and seven for black women. Hutments were prefabricated plywood

Plywood is a material manufactured from thin layers or "plies" of wood veneer that are glued together with adjacent layers having their wood grain rotated up to 90 degrees to one another. It is an engineered wood from the family of manufactured ...

and Celotex

Celotex Corporation is a defunct American manufacturer of insulation and construction materials. It was the subject of a number of high-profile lawsuits over products containing asbestos in the 1980s, eventually declaring Chapter 11 bankruptcy in ...

dwellings capable of accommodating ten to twenty workers each. Between them, the barracks and hutments held 39,050 workers. Many workers had their own trailers, taking their families with them from one wartime construction job to the next. Seven trailer camps were established, and at the peak of construction work 12,008 people were living in them.

DuPont put the contract for building the village of Richland out to tender, and the contract was awarded to the lowest bidder, G. Albin Pehrson, on March 16, 1943. Pehrson produced a series of standard house designs based on the Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mont ...

and ranch-style house

Ranch (also known as American ranch, California ranch, rambler, or rancher) is a domestic architectural style that originated in the United States. The ranch-style house is noted for its long, close-to-the-ground profile, and wide open layout. ...

design fashions of the day. Pehrson accepted the need for speed and efficiency, but his vision of a model late-20th-century community differed from the austere concept of Groves. Pehrson ultimately had his way on most issues, because DuPont was his contractor, not the Army. The resulting compromise would handicap Richland for many years with inadequate sidewalks, stores and shops, no civic center, and roads that were too narrow. Unlike Oak Ridge and Los Alamos, Richland was not surrounded by a high wire fence. Because it was open, Matthias asked DuPont to ensure that it was kept neat and tidy.

Construction

Construction of the nuclear facilities proceeded rapidly. Before the end of the war in August 1945, the HEW built 554 buildings at Hanford, including three nuclear reactors (105B, 105D, and 105F) and three plutonium processing plants (221T, 221B, and 221U). The project required of roads, of railway, and four electrical substations. The HEW used of concrete and of structural steel.

Construction on B Reactor commenced in August 1943 and was completed on September 13, 1944. The reactor went

Construction of the nuclear facilities proceeded rapidly. Before the end of the war in August 1945, the HEW built 554 buildings at Hanford, including three nuclear reactors (105B, 105D, and 105F) and three plutonium processing plants (221T, 221B, and 221U). The project required of roads, of railway, and four electrical substations. The HEW used of concrete and of structural steel.

Construction on B Reactor commenced in August 1943 and was completed on September 13, 1944. The reactor went critical

Critical or Critically may refer to:

*Critical, or critical but stable, medical states

**Critical, or intensive care medicine

*Critical juncture, a discontinuous change studied in the social sciences.

*Critical Software, a company specializing in ...

in late September and, after overcoming neutron poison

In applications such as nuclear reactors, a neutron poison (also called a neutron absorber or a nuclear poison) is a substance with a large neutron absorption cross-section. In such applications, absorbing neutrons is normally an undesirable eff ...

ing, produced its first plutonium on November 6, 1944. The reactors were graphite

Graphite () is a crystalline form of the element carbon. It consists of stacked layers of graphene. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable form of carbon under standard conditions. Synthetic and natural graphite are consumed on large ...

moderated and water cooled. They consisted of a , graphite cylinder lying on its side, penetrated horizontally through its entire length by 2,004 aluminum tubes. containing of uranium slugs. They had no moving parts; the only sounds were those of the water pumps. Cooling water

Cooling tower and water discharge of a nuclear power plant

Water cooling is a method of heat removal from components and industrial equipment. Evaporative cooling using water is often more efficient than air cooling. Water is inexpensive and non ...

was pumped through the tubes at the rate of . This was enough water for a city of a million people.

Production process

Uranium arrived at the Hanford Engineer Works in the form ofbillet

A billet is a living-quarters to which a soldier is assigned to sleep. Historically, a billet was a private dwelling that was required to accept the soldier.

Soldiers are generally billeted in barracks or garrisons when not on combat duty, alth ...

s. In the Metal Fabrication and Testing (500) Area they were extruded into rods and machined into cylindrical pieces, in diameter and long, known as "slugs". The initial charge of the three reactors required more than twenty thousand billets, and another two thousand were required each month. Uranium was highly reactive with water, so to protect them from corrosion by the cooling water they were canned in aluminum a molten bath of copper–tin alloy, and the cap was arc welded on. A defective can could burst and jam in the reactor, stop the flow of cooling water, and force a complete shutdown of the reactor, so the canning process had to be exacting.

Irradiated fuel slugs were transported by rail to huge remotely operated chemical separation plants about away on a special railroad car operated by remote control. The separation buildings were massive windowless concrete structures, long, high and wide, with concrete walls thick. Inside the buildings were canyons and galleries where a series of chemical processing steps separated the small amount of plutonium from the remaining uranium and

Irradiated fuel slugs were transported by rail to huge remotely operated chemical separation plants about away on a special railroad car operated by remote control. The separation buildings were massive windowless concrete structures, long, high and wide, with concrete walls thick. Inside the buildings were canyons and galleries where a series of chemical processing steps separated the small amount of plutonium from the remaining uranium and fission products

Nuclear fission products are the atomic fragments left after a large atomic nucleus undergoes nuclear fission. Typically, a large nucleus like that of uranium fissions by splitting into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons, the release ...

.

Items were moved about with a long overhead crane

An overhead crane, commonly called a bridge crane, is a type of crane found in industrial environments. An overhead crane consists of two parallel rails seated on longitudinal I-beams attached to opposite steel columns by means of brackets. ...

. Once they began processing irradiated slugs, the machinery became so radioactive that it would be unsafe for humans ever to come in contact with it, so the engineers devised methods to allow for the replacement of components via remote control. Periscopes and closed-circuit television

Closed-circuit television (CCTV), also known as video surveillance, is the use of video cameras to transmit a signal to a specific place, on a limited set of monitors. It differs from broadcast television in that the signal is not openly t ...

gave the operator a view of the process. They assembled the equipment by remote control as if the area was already radioactive. To receive the radioactive wastes from the chemical separations process, there were "tank farms" consisting of 64 single-shell underground waste tanks.

The first batch of plutonium was refined in the 221T plant from December 26, 1944, to February 2, 1945, and delivered to the Los Alamos laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

in New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

on February 5, 1945. Two identical reactors, DReactor and FReactor, came online on December 5, 1944, and February 15, 1945, respectively, and all three reactors were running at full power (250 megawatts) by March 8, 1945. By April kilogram-quantity shipments of plutonium were headed to Los Alamos. Road convoys replaced the trains in May, and in late July shipments began being dispatched by air from the airport at Hanford.

Production activities

Although the reactors could be shut down in two-and-a-half seconds, the decay of fission products meant that they would still generate heat due to the decay of fission products. It was therefore vital that the flow of water should not cease. If the power failed, the steam pumps would automatically cut in and continue to deliver water at full capacity for long enough to allow an orderly shutdown. This occurred on March 10, 1945, when a Japanese balloon bomb struck a high-tension line between Grand Coulee and Bonneville. This caused an electrical surge in the lines to the reactors. A

Although the reactors could be shut down in two-and-a-half seconds, the decay of fission products meant that they would still generate heat due to the decay of fission products. It was therefore vital that the flow of water should not cease. If the power failed, the steam pumps would automatically cut in and continue to deliver water at full capacity for long enough to allow an orderly shutdown. This occurred on March 10, 1945, when a Japanese balloon bomb struck a high-tension line between Grand Coulee and Bonneville. This caused an electrical surge in the lines to the reactors. A scram

A scram or SCRAM is an emergency shutdown of a nuclear reactor effected by immediately terminating the fission reaction. It is also the name that is given to the manually operated kill switch that initiates the shutdown. In commercial reactor ...

was automatically initiated and the safety devices shut the reactors down. The bomb failed to explode and the transmission line was not badly damaged. The Hanford Engineer Works was the only U.S. nuclear facility to come under enemy attack.

Hanford provided the plutonium for the bomb used in the 1945 Trinity nuclear test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert abo ...

. Throughout this period, the Manhattan Project maintained a top-secret classification. Fewer than one percent of Hanford's workers knew they were working on a nuclear weapons project. Groves noted in his memoirs that "We made certain that each member of the project thoroughly understood his part in the total effort; that, and nothing more." The existence and purpose of Hanford was publicly revealed through press releases on August 7 and 9, 1945, after the bombing of Hiroshima

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the on ...

but before Hanford plutonium in a Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

bomb was used in the bombing of Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the on ...

on August 9.

Matthias was succeeded as area engineer by Colonel Frederick J. Clarke in January 1946. DuPont would soon be gone too. Carpenter asked to be released from the contract. Groves informed Robert P. Patterson

Robert Porter Patterson Sr. (February 12, 1891 – January 22, 1952) was an American judge who served as United States Under Secretary of War, Under Secretary of War under President Franklin D. Roosevelt and US Secretary of War, U.S. Secretary of ...

, who had succeeded Stimson as Secretary of War on September 21, 1945, Groves's choice of replacement was General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable energ ...

(GE), which took over operations at Hanford on September 1, 1946, and accepted a formal control on September 30. On December 31, 1946, the Manhattan Project ended and control of the Hanford Site passed to the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). The total cost of the Hanford Engineer Works up to that time was .

Cold War

Production problems

GE inherited serious problems. Running the reactors continuously at full power had resulted in theWigner effect

The Wigner effect (named for its discoverer, Eugene Wigner), also known as the discomposition effect or Wigner's disease, is the displacement of atoms in a solid caused by neutron radiation.

Any solid can display the Wigner effect. The effect is ...

, swelling of the graphite due to the displacement of the atoms in its crystalline structure by collisions with neutrons. This had the potential to buckle the aluminum tubes used for the fuel and control rods and disable the reactors completely if a water pipe ruptured. The polonium-210

Polonium-210 (210Po, Po-210, historically radium F) is an isotope of polonium. It undergoes alpha decay to stable 206Pb with a half-life of 138.376 days (about months), the longest half-life of all naturally occurring polonium isotopes. First i ...

used in the Fat Man's neutron initiator

A modulated neutron initiator is a neutron source capable of producing a burst of neutrons on activation. It is a crucial part of some nuclear weapons, as its role is to "kick-start" the chain reaction at the optimal moment when the configuration i ...

s had a half-life

Half-life (symbol ) is the time required for a quantity (of substance) to reduce to half of its initial value. The term is commonly used in nuclear physics to describe how quickly unstable atoms undergo radioactive decay or how long stable ato ...

of only 138 days, so it was essential to keep a reactor running or the weapons would be rendered inoperative. The Army therefore shut down BReactor on March 19. In August 1946 Franklin was informed that irradiating the feed to produce over 200 grams of plutonium per metric ton of uranium was resulting in too much undesirable plutonium-240

Plutonium-240 ( or Pu-240) is an isotope of plutonium formed when plutonium-239 captures a neutron. The detection of its spontaneous fission led to its discovery in 1944 at Los Alamos and had important consequences for the Manhattan Project.

240 ...

in the product. The power level on Dand FReactors was reduced, which also extended their useful life. Some experiments were conducted with annealing the graphite. It was found in laboratory testing of samples that heating to retired the graphite by 24 percent, to by 45 percent and to by 94 percent, but the consequences of heating the reactors so much had to be considered before this was attempted.

The other problem was that the bismuth phosphate process used to separate the plutonium left the uranium in an unrecoverable state. The Metallurgical Laboratory had researched a promising new

The other problem was that the bismuth phosphate process used to separate the plutonium left the uranium in an unrecoverable state. The Metallurgical Laboratory had researched a promising new redox

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate (chemistry), substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of Electron, electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction ...

separation process, using hexone Methyl isobutyl ketone (MIBK) is the common name for the organic compound 4-methylpentan-2-one, structural formula, condensed chemical formula (CH3)2CHCH2C(O)CH3. This colourless liquid, a ketone, is used as a solvent for gums, resins, paints, varni ...

as a solvent. The AEC was concerned about the supply of uranium, and the General Advisory Committee of the AEC recommended that construction of a redox plant be given top priority. Meanwhile, the waste-settling tanks filled up with sludge

Sludge is a semi-solid slurry that can be produced from a range of industrial processes, from water treatment, wastewater treatment or on-site sanitation systems. For example, it can be produced as a settled suspension obtained from conventiona ...

, and attempts to transport it to the waste storage (241) areas were unsuccessful. It was therefore decided to bypass the waste settling tanks and send sludge directly to the 200 area, and construction of a bypass commenced in August 1946. GE invited bids for the construction of a new waste storage tank farm. Efforts were made to make better use of the available uranium. Turnings, cuttings and shavings from the slug manufacture process had been sent to the Ames Laboratory

Ames National Laboratory, formerly Ames Laboratory, is a United States Department of Energy United States Department of Energy national laboratories, national laboratory located in Ames, Iowa, and affiliated with Iowa State University. It is a t ...

in Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

for briquetting

A briquette (; also spelled briquet) is a compressed block of coal dust or other combustible biomass material (e.g. charcoal, sawdust, wood chips, peat, or paper) used for fuel and kindling to start a fire. The term derives from the French word '' ...

. The equipment there was shipped to the Hanford Engineer Works. The briquettes, along with uranium scrap metal, was sent to the Metal Hydrides Company for recasting into billets.

During 1947, tensions with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

escalated as the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...