Hand Axe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A hand axe (or handaxe or Acheulean hand axe) is a

A hand axe (or handaxe or Acheulean hand axe) is a  Hand axes were the first prehistoric tools to be recognized as such: the first published representation of a hand axe was drawn by

Hand axes were the first prehistoric tools to be recognized as such: the first published representation of a hand axe was drawn by

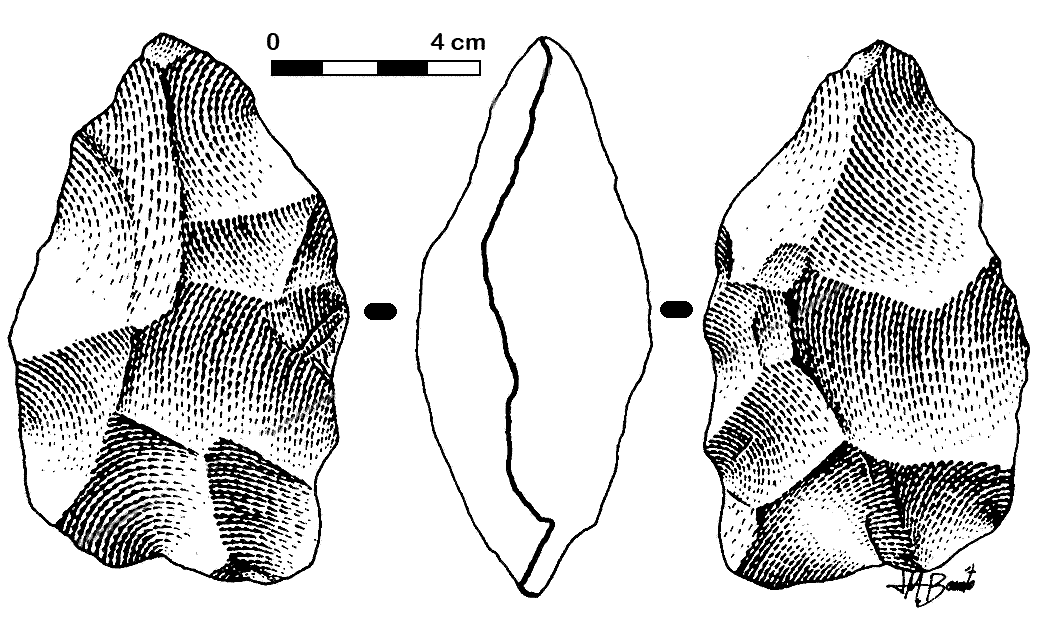

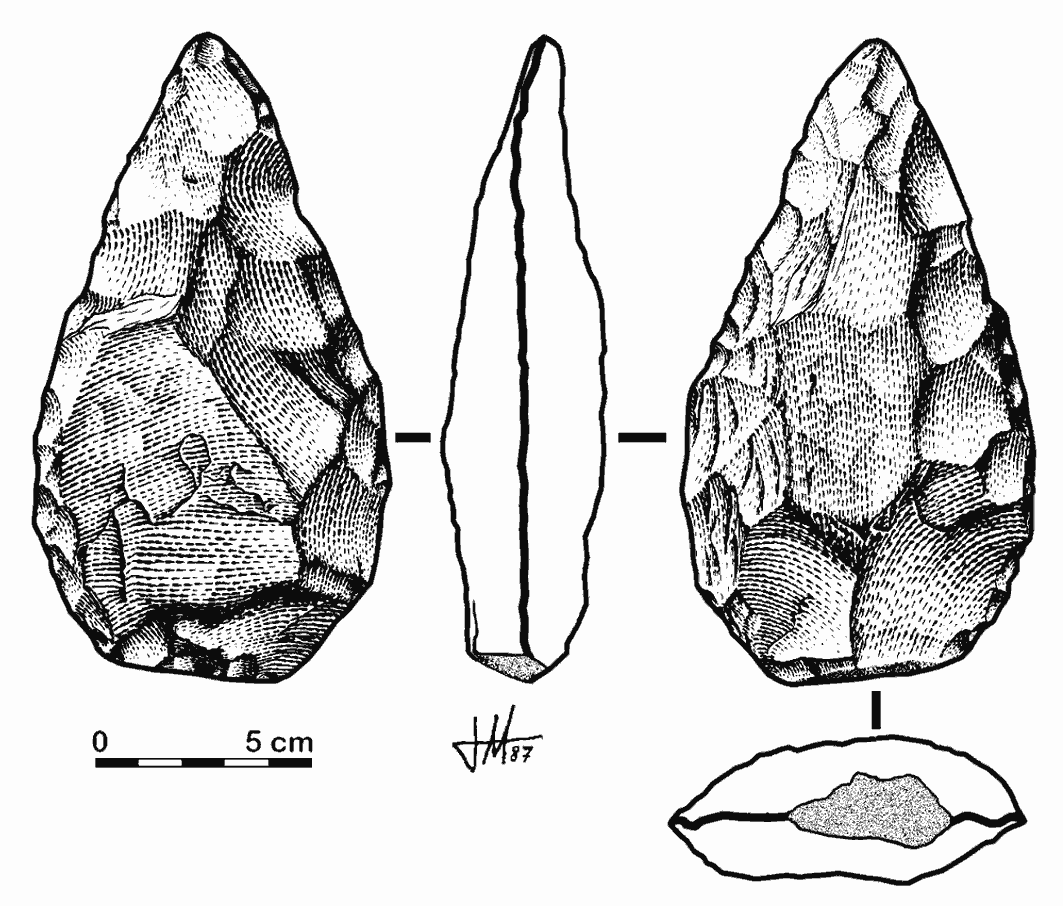

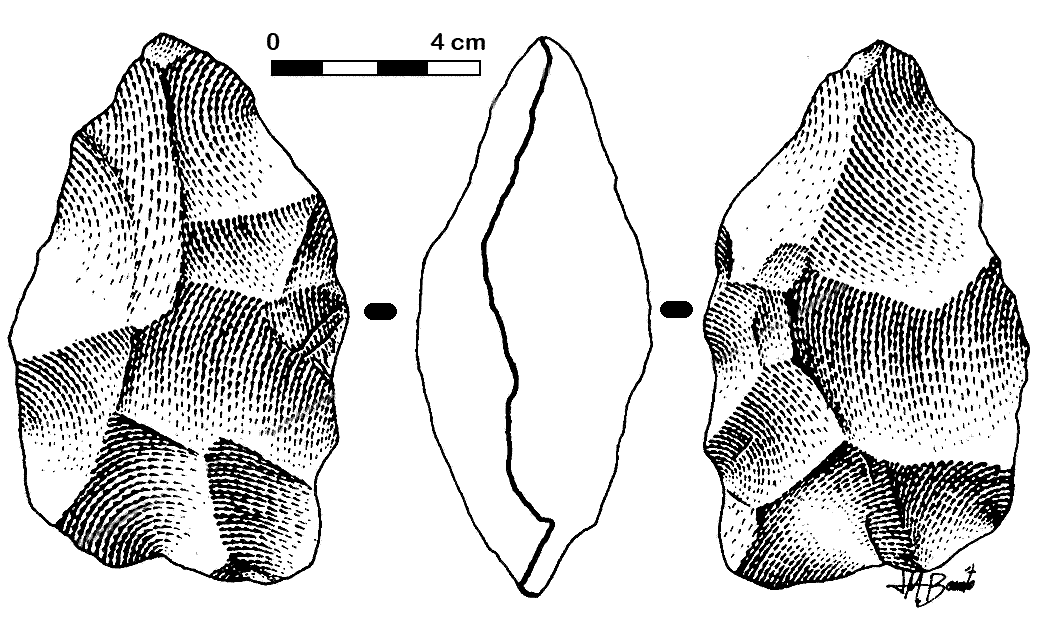

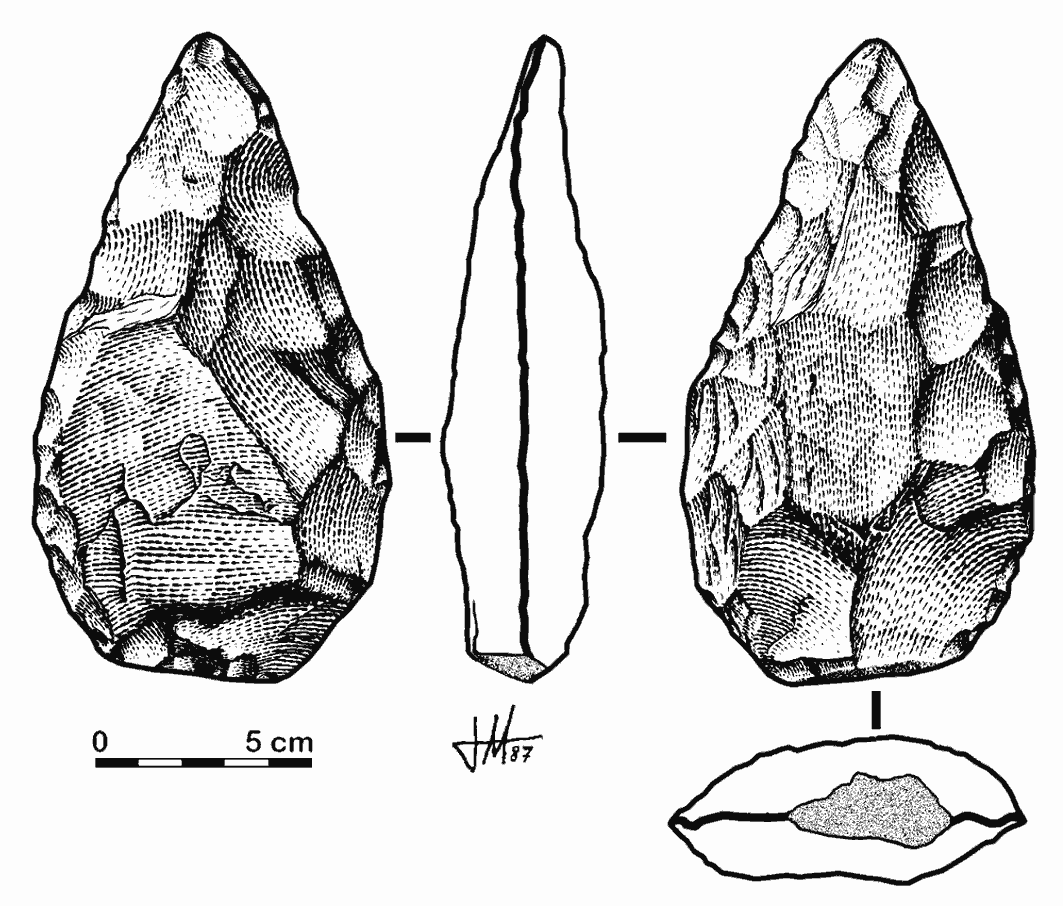

The most characteristic and common shape is a pointed area at one end, cutting edges along its side and a rounded base (this includes hand axes with a lanceolate and amygdaloidal shape as well as others from the family). The axes are almost always symmetrical, despite studies showing that symmetry doesn’t help in tasks such as using a hand axe for skinning animals. While there is a “typical” shape to most hand axes, there are some displaying a variety of shapes, including circular, triangular and elliptical—calling in to question the contention that they had a constant and only symbolic significance. They are typically between long, although they can be bigger or smaller.

The most characteristic and common shape is a pointed area at one end, cutting edges along its side and a rounded base (this includes hand axes with a lanceolate and amygdaloidal shape as well as others from the family). The axes are almost always symmetrical, despite studies showing that symmetry doesn’t help in tasks such as using a hand axe for skinning animals. While there is a “typical” shape to most hand axes, there are some displaying a variety of shapes, including circular, triangular and elliptical—calling in to question the contention that they had a constant and only symbolic significance. They are typically between long, although they can be bigger or smaller.

They were typically made from a rounded

They were typically made from a rounded

The apogee of hand axe manufacture took place in a wide area of the

The apogee of hand axe manufacture took place in a wide area of the

Hand axes are most commonly made from rounded pebbles or nodules, but many are also made from a large flake. Hand axes made from flakes first appeared at the start of the Acheulean period and became more common with time. Manufacturing a hand axe from a flake is actually easier than from a pebble. It is also quicker, as flakes are more likely to be closer to the desired shape. This allows easier manipulation and fewer knaps are required to finish the tool; it is also easier to obtain straight edges. When analysing a hand axe made from a flake, it should be remembered that its shape was predetermined (by use of the

Hand axes are most commonly made from rounded pebbles or nodules, but many are also made from a large flake. Hand axes made from flakes first appeared at the start of the Acheulean period and became more common with time. Manufacturing a hand axe from a flake is actually easier than from a pebble. It is also quicker, as flakes are more likely to be closer to the desired shape. This allows easier manipulation and fewer knaps are required to finish the tool; it is also easier to obtain straight edges. When analysing a hand axe made from a flake, it should be remembered that its shape was predetermined (by use of the

Some hand axes were formed with a hard hammer and finished with a soft hammer. Blows that result in deep conchoidal fractures (the first phase of manufacture) can be distinguished from features resulting from sharpening with a soft hammer. The latter leaves shallower, more distended, broader scars, sometimes with small, multiple shock waves. However, marks left by a small, hard hammer can leave similar marks to a soft hammer.

Soft hammer finished pieces are usually balanced and symmetrical, and can be relatively smooth. Soft hammer works first appeared in the Acheulean period, allowing tools with these markings to be used as a '' post quem'' estimation, but with no greater precision. The main advantage of a soft hammer is that a flintknapper is able to remove broader, thinner flakes with barely developed heels, which allows a cutting edge to be maintained or even improved with minimal raw material wastage. However, a high-quality raw material is required to make their use effective. No studies compare the two methods in terms of yield per unit weight of raw material, or the difference in energy use. The use of a soft hammer requires greater use of force by the

Some hand axes were formed with a hard hammer and finished with a soft hammer. Blows that result in deep conchoidal fractures (the first phase of manufacture) can be distinguished from features resulting from sharpening with a soft hammer. The latter leaves shallower, more distended, broader scars, sometimes with small, multiple shock waves. However, marks left by a small, hard hammer can leave similar marks to a soft hammer.

Soft hammer finished pieces are usually balanced and symmetrical, and can be relatively smooth. Soft hammer works first appeared in the Acheulean period, allowing tools with these markings to be used as a '' post quem'' estimation, but with no greater precision. The main advantage of a soft hammer is that a flintknapper is able to remove broader, thinner flakes with barely developed heels, which allows a cutting edge to be maintained or even improved with minimal raw material wastage. However, a high-quality raw material is required to make their use effective. No studies compare the two methods in terms of yield per unit weight of raw material, or the difference in energy use. The use of a soft hammer requires greater use of force by the

Hand axes made using only a soft hammer are much less common. In most cases at least initial work was done with a hard hammer, before subsequent flaking with a soft hammer erased all vestiges of that work. A soft hammer is not suitable for all types of percussion platform and it cannot be used on certain types of raw material. It is, therefore, necessary to start with a hard hammer or with a flake as a core as its edge will be fragile (flat, smooth pebbles are also useful). This means that although it was possible to manufacture a hand axe using a soft hammer, it is reasonable to suppose that a hard hammer was used to prepare a ''blank'' followed by one or more phases of retouching to finish the piece. However, the degree of separation between the phases is not certain, as the work could have been carried out in one operation.

Working with a soft hammer allows a knapper greater control of the knapping and reduces waste of the raw material, allowing the production of longer, sharper, more uniform edges that will increase the tool's working life. Hand axes made with a soft hammer are usually more symmetrical and smooth, with rectilinear edges and shallow indentations that are broad and smooth so that it is difficult to distinguish where one flake starts and another ends. They generally have a regular biconvex cross-section and the intersection of the two faces forms an edge with an acute angle, usually of around 30°. They were worked with great skill and therefore they are more aesthetically attractive. They are usually associated with periods of highly developed tool making such as the

Hand axes made using only a soft hammer are much less common. In most cases at least initial work was done with a hard hammer, before subsequent flaking with a soft hammer erased all vestiges of that work. A soft hammer is not suitable for all types of percussion platform and it cannot be used on certain types of raw material. It is, therefore, necessary to start with a hard hammer or with a flake as a core as its edge will be fragile (flat, smooth pebbles are also useful). This means that although it was possible to manufacture a hand axe using a soft hammer, it is reasonable to suppose that a hard hammer was used to prepare a ''blank'' followed by one or more phases of retouching to finish the piece. However, the degree of separation between the phases is not certain, as the work could have been carried out in one operation.

Working with a soft hammer allows a knapper greater control of the knapping and reduces waste of the raw material, allowing the production of longer, sharper, more uniform edges that will increase the tool's working life. Hand axes made with a soft hammer are usually more symmetrical and smooth, with rectilinear edges and shallow indentations that are broad and smooth so that it is difficult to distinguish where one flake starts and another ends. They generally have a regular biconvex cross-section and the intersection of the two faces forms an edge with an acute angle, usually of around 30°. They were worked with great skill and therefore they are more aesthetically attractive. They are usually associated with periods of highly developed tool making such as the

Hand axes have traditionally been oriented with their narrowest part upwards (presupposing that this would have been the most active part, which is not unreasonable given the many hand axes that have unworked bases). The following typological conventions are used to facilitate communication. The

Hand axes have traditionally been oriented with their narrowest part upwards (presupposing that this would have been the most active part, which is not unreasonable given the many hand axes that have unworked bases). The following typological conventions are used to facilitate communication. The

Hand axe measurements use the morphological axis as a reference and for orientation. In addition to length,

Hand axe measurements use the morphological axis as a reference and for orientation. In addition to length,

*Cleaver-bifaces—These bifaces have an apex that is neither pointed nor rounded. They possess a relatively wide terminal edge that is transverse to the morphological axis. This edge is usually more or less sub-rectilinear, slightly concave or convex. They are sometimes included within the classic types as they have a balanced, well-finished form. Cleaver-bifaces were defined by Chavaillón in 1958 as "biface with terminal bevel" (''biface à biseau terminal''), while Bordes simply called them "cleavers" (''hachereaux)'' The current term was proposed in French by Guichard in 1966 (''biface-hachereau''). The term biface-cleaver was proposed in Spanish in 1982 (bifaz-hendidor), with "biface" used as a

*Cleaver-bifaces—These bifaces have an apex that is neither pointed nor rounded. They possess a relatively wide terminal edge that is transverse to the morphological axis. This edge is usually more or less sub-rectilinear, slightly concave or convex. They are sometimes included within the classic types as they have a balanced, well-finished form. Cleaver-bifaces were defined by Chavaillón in 1958 as "biface with terminal bevel" (''biface à biseau terminal''), while Bordes simply called them "cleavers" (''hachereaux)'' The current term was proposed in French by Guichard in 1966 (''biface-hachereau''). The term biface-cleaver was proposed in Spanish in 1982 (bifaz-hendidor), with "biface" used as a

As Leroi-Gourhan explained, it is important to ask what was understood of art at the time, considering the psychologies of non-modern humans. Archaeological records documenting rapid progress towards symmetry and balance surprised Leroi-Gourha. He felt that he could recognize beauty in early prehistoric tools made during the Acheulean:

Many authors refer only to exceptional pieces. The majority of hand axes tended to symmetry, but lack artistic appeal. Generally, only the most striking pieces are considered, mainly 19th or early 20th century collections. At that time a lack of knowledge regarding prehistoric technology prevented a recognition of human actions in these objects. Other collections were made by aficionados, whose interests were not scientific, so that they collected only objects they considered to be outstanding, abandoning humbler elements that were sometimes necessary to interpret an archaeological site. Exceptions include sites methodically studied by experts where magnificently carved, abundant hand axes caused archaeologists to express admiration for the artists:

The discovery in 1998 of an oval hand axe of excellent workmanship in the Sima de los Huesos in the Atapuerca Mountains mixed in with the fossil remains of ''

As Leroi-Gourhan explained, it is important to ask what was understood of art at the time, considering the psychologies of non-modern humans. Archaeological records documenting rapid progress towards symmetry and balance surprised Leroi-Gourha. He felt that he could recognize beauty in early prehistoric tools made during the Acheulean:

Many authors refer only to exceptional pieces. The majority of hand axes tended to symmetry, but lack artistic appeal. Generally, only the most striking pieces are considered, mainly 19th or early 20th century collections. At that time a lack of knowledge regarding prehistoric technology prevented a recognition of human actions in these objects. Other collections were made by aficionados, whose interests were not scientific, so that they collected only objects they considered to be outstanding, abandoning humbler elements that were sometimes necessary to interpret an archaeological site. Exceptions include sites methodically studied by experts where magnificently carved, abundant hand axes caused archaeologists to express admiration for the artists:

The discovery in 1998 of an oval hand axe of excellent workmanship in the Sima de los Huesos in the Atapuerca Mountains mixed in with the fossil remains of ''

File:Vuistbijl in silex, 500 000 tot 400 000 BP, vindplaats- Kesselt, Op de Schans, 2007, erosiegeul, collectie Gallo-Romeins Museum Tongeren, GRM 19169.jpg, Atypical flint biface from the Lower Paleolithic

Rediscovery and the cognitive aspects of toolmaking: Lessons from the handaxe

by William H. Calvin

* ttp://arqueologicas.tripod.com/bifaces.html «Bifaces de Cuba»*10.1126/science.287.5458.1622 * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hand Axe Axes Lithics Archaeological artefact types Primitive weapons Paleolithic Stone objects eo:Pugnokojno fy:Fûstbile

prehistoric

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use of ...

stone tool with two faces that is the longest-used tool

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, only human beings, whose use of stone tools dates ba ...

in human history

Human history, also called world history, is the narrative of humanity's past. It is understood and studied through anthropology, archaeology, genetics, and linguistics. Since the invention of writing, human history has been studied throug ...

, yet there is no academic consensus on what they were used for. It is made from stone, usually flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start fir ...

or chert

Chert () is a hard, fine-grained sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz, the mineral form of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Chert is characteristically of biological origin, but may also occur inorganically as a prec ...

that has been "reduced" and shaped from a larger piece by knapping

Knapping is the shaping of flint, chert, obsidian, or other conchoidal fracturing stone through the process of lithic reduction to manufacture stone tools, strikers for flintlock firearms, or to produce flat-faced stones for building or facing ...

, or hitting against another stone. They are characteristic of the lower Acheulean

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French ''acheuléen'' after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated ...

and middle Palaeolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός ''palaios'', "old" and λίθος '' lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone to ...

(Mousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an archaeological industry of stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and to the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and West Asia. The Mousterian largely defines the l ...

) periods, roughly 1.6 million years ago to about 100,000 years ago, and used by ''Homo erectus

''Homo erectus'' (; meaning "upright man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Pleistocene, with its earliest occurrence about 2 million years ago. Several human species, such as '' H. heidelbergensis'' and '' H. antecessor' ...

'' and other early humans, but rarely by ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

''.

Their technical name (biface) comes from the fact that the archetypical model is a generally bifacial (with two wide sides or faces) and almond-shaped (amygdaloidal) lithic flake

In archaeology, a lithic flake is a "portion of rock removed from an objective piece by percussion or pressure,"Andrefsky, W. (2005) ''Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis''. 2d Ed. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press and may also be refe ...

. Hand axes tend to be symmetrical

Symmetry (from grc, συμμετρία "agreement in dimensions, due proportion, arrangement") in everyday language refers to a sense of harmonious and beautiful proportion and balance. In mathematics, "symmetry" has a more precise definiti ...

along their longitudinal axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

and formed by pressure or percussion. The most common hand axes have a pointed end and rounded base, which gives them their characteristic almond shape, and both faces have been knapped

Knapping is the shaping of flint, chert, obsidian, or other conchoidal fracturing stone through the process of lithic reduction to manufacture stone tools, strikers for flintlock firearms, or to produce flat-faced stones for building or facing w ...

to remove the natural cortex

Cortex or cortical may refer to:

Biology

* Cortex (anatomy), the outermost layer of an organ

** Cerebral cortex, the outer layer of the vertebrate cerebrum, part of which is the ''forebrain''

*** Motor cortex, the regions of the cerebral cortex i ...

, at least partially. Hand axes are a type of the somewhat wider biface group of two-faced tools or weapons.

Hand axes were the first prehistoric tools to be recognized as such: the first published representation of a hand axe was drawn by

Hand axes were the first prehistoric tools to be recognized as such: the first published representation of a hand axe was drawn by John Frere

John Frere (10 August 1740 – 12 July 1807) was an English antiquary and a pioneering discoverer of Old Stone Age or Lower Palaeolithic tools in association with large extinct animals at Hoxne, Suffolk in 1797.

Life

Frere was born in R ...

and appeared in a British publication in 1800. Until that time, their origins were thought to be natural or supernatural. They were called '' thunderstones'', because popular tradition held that they had fallen from the sky during storms or were formed inside the earth by a lightning strike

A lightning strike or lightning bolt is an electric discharge between the atmosphere and the ground. Most originate in a cumulonimbus cloud and terminate on the ground, called cloud-to-ground (CG) lightning. A less common type of strike, ground- ...

and then appeared at the surface. They are used in some rural areas as an amulet to protect against storms.

Hand axe tools were possibly used to butcher animals; to dig for tuber

Tubers are a type of enlarged structure used as storage organs for nutrients in some plants. They are used for the plant's perennation (survival of the winter or dry months), to provide energy and nutrients for regrowth during the next growin ...

s, animals and water; to chop wood and remove tree bark; and/or process vegetal materials. Other scholars have proposed that hand axes were used to throw at prey; for a ritual or social purpose; or possibly as a source for flake tool

In archaeology, a flake tool is a type of stone tool that was used during the Stone Age that was created by striking a flake from a prepared stone core.

People during prehistoric times often preferred these flake tools as compared to other tools ...

s.

Terminology

Four classes of hand axe are: # Large, thick hand axes reduced from cores or thick flakes, referred to as blanks # Thinned blanks. While form remains rough and uncertain, an effort has been made to reduce the thickness of the flake or core # Either a preform or crude formalized tool, such as anadze

An adze (; alternative spelling: adz) is an ancient and versatile cutting tool similar to an axe but with the cutting edge perpendicular to the handle rather than parallel. Adzes have been used since the Stone Age. They are used for smoothing ...

# Finer formalized tool types such as projectile point

In North American archaeological terminology, a projectile point is an object that was hafted to a weapon that was capable of being thrown or projected, such as a javelin, dart, or arrow. They are thus different from weapons presumed to have ...

s and fine bifaces

While Class 4 hand axes are referred to as "formalized tools", bifaces from any stage of a lithic reduction

In archaeology, in particular of the Stone Age, lithic reduction is the process of fashioning stones or rocks from their natural state into tools or weapons by removing some parts. It has been intensely studied and many archaeological industrie ...

sequence may be used as tools. (Other biface typologies make five divisions rather than four.)

French antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

André Vayson de Pradenne introduced the word in 1920. This term co-exists with the more popular ''hand axe'' (), that was coined by Gabriel de Mortillet

Louis Laurent Gabriel de Mortillet (29 August 1821 – 25 September 1898), French archaeologist and anthropologist, was born at Meylan, Isère.

Biography

Mortillet was educated at the Jesuit college of Chambéry and at the Paris Conservat ...

much earlier. The continued use of the word biface by François Bordes

François Bordes (December 30, 1919 – April 30, 1981), also known by the pen name of Francis Carsac, was a French scientist, geologist, archaeologist, and science fiction writer.

Biography

He was a professor of prehistory and quaternary g ...

and Lionel Balout supported its use in France and Spain, where it replaced the term ''hand axe''. Use of the expression ''hand axe'' has continued in English as the equivalent of the French ( in Spanish), while biface applies more generally for any piece that has been carved on both sides by the removal of shallow or deep flakes. The expression is used in German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

; it can be literally translated as hand axe, although in a stricter sense it means "fist wedge". It is the same in Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

where the expression used is which literally means "fist axe". The same locution occurs in other languages.

However, the general impression of these tools was based on ideal (or classic) pieces that were of such perfect shape that they caught the attention of non-experts. Their typology

Typology is the study of types or the systematic classification of the types of something according to their common characteristics. Typology is the act of finding, counting and classification facts with the help of eyes, other senses and logic. Ty ...

broadened the term's meaning. Biface hand axe and bifacial lithic items are distinguished. A hand axe need not be a bifacial item and many bifacial items are not hand axes. Nor were hand axes and bifacial items exclusive to the Lower Palaeolithic period in the Old World. They appear throughout the world and in many different pre-historical epochs, without necessarily implying an ancient origin. Lithic typology is not a reliable chronological reference and was abandoned as a dating system. Examples of this include the "quasi-bifaces" that sometimes appear in strata from the Gravettian

The Gravettian was an archaeological industry of the European Upper Paleolithic that succeeded the Aurignacian circa 33,000 years BP. It is archaeologically the last European culture many consider unified, and had mostly disappeared by ...

, Solutrean

The Solutrean industry is a relatively advanced flint tool-making style of the Upper Paleolithic of the Final Gravettian, from around 22,000 to 17,000 BP. Solutrean sites have been found in modern-day France, Spain and Portugal.

Details

...

and Magdalenian periods in France and Spain, the crude bifacial pieces of the Lupemban culture

The Lupemban is the name given by archaeologists to a central African culture which, though once thought to date between c. 30,000 and 12,000 BC, is now generally recognised to be far older (dates of c. 300,000 have been obtained from Twin Rivers ...

( 9000 B.C.) or the pyriform

Piriform, sometimes ''pyriform'', means pear-shaped (from Latin ''pirum'' "pear" and ''forma'' "shape").

It may also refer to:

Going pear-shaped

* Going wrong or going pear-shaped

Anatomy

* Piriform aperture, more commonly known as anterior n ...

tools found near Sagua La Grande

Sagua la Grande (nicknamed ''La Villa del Undoso'', sometimes shortened in Sagua) is a municipality located on the north coast of the province of Villa Clara in central Cuba, on the Sagua la Grande River. The city is close to Mogotes de Juma ...

in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

. The word ''biface'' refers to something different in English than in French or in Spanish, which could lead to many misunderstandings. Bifacially carved cutting tools, similar to hand axes, were used to clear scrub vegetation throughout the Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

and Chalcolithic

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', "copper" and ''líthos'', "stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin '' aeneus'' "of copper"), is an archaeological period characterized by regular ...

periods. These tools are similar to more modern adze

An adze (; alternative spelling: adz) is an ancient and versatile cutting tool similar to an axe but with the cutting edge perpendicular to the handle rather than parallel. Adzes have been used since the Stone Age. They are used for smoothing ...

s and were a cheaper alternative to polished axes. The modern day villages along the Sepik

The Sepik () is the longest river on the island of New Guinea, and the second largest in Oceania by discharge volume after the Fly River. The majority of the river flows through the Papua New Guinea (PNG) provinces of Sandaun (formerly West Se ...

river in New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

continue to use tools that are virtually identical to hand axes to clear forest. "The term ''biface'' should be reserved for items from before the Würm II-III interstadial

Stadials and interstadials are phases dividing the Quaternary period, or the last 2.6 million years. Stadials are periods of colder climate while interstadials are periods of warmer climate.

Each Quaternary climate phase is associated with a Ma ...

", although certain later objects could ''exceptionally'' be called bifaces.

''Hand axe'' does not relate to ''axe

An axe ( sometimes ax in American English; see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood, to harvest timber, as a weapon, and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol. The axe has ma ...

'', which was overused in lithic typology to describe a wide variety of stone tools. At the time the use of such items was not understood. In the particular case of Palaeolithic hand axes the term axe is an inadequate description. Lionel Balout stated, "the term should be rejected as an erroneous interpretation of these objects that are not 'axes. Subsequent studies supported this idea, particularly those examining the signs of use.

Materials

Hand axes are mainly made offlint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start fir ...

, but rhyolite

Rhyolite ( ) is the most silica-rich of volcanic rocks. It is generally glassy or fine-grained (aphanitic) in texture, but may be porphyritic, containing larger mineral crystals (phenocrysts) in an otherwise fine-grained groundmass. The mineral ...

s, phonolites, quartzite

Quartzite is a hard, non- foliated metamorphic rock which was originally pure quartz sandstone.Essentials of Geology, 3rd Edition, Stephen Marshak, p 182 Sandstone is converted into quartzite through heating and pressure usually related to tect ...

s and other coarse rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wales ...

s were used as well. Obsidian

Obsidian () is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock.

Obsidian is produced from felsic lava, rich in the lighter elements s ...

, natural volcanic glass, shatters easily and was rarely used.

Uses

No academic consensus describes their use, but it is commonly agreed that the hand axe was some form of unhafted all-purpose tool. The pioneers of Palaeolithic tool studies first suggested that bifaces were used asaxe

An axe ( sometimes ax in American English; see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood, to harvest timber, as a weapon, and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol. The axe has ma ...

s despite the fact that they have a sharp border all around. Other uses seem to show that hand axes were a multi-functional tool, leading some to describe them as the "Acheulean Swiss Army knife". Other academics have suggested that the hand axe was simply a byproduct of being used as a core to make other tools, a weapon, or was perhaps used ritually.

Wells

Wells most commonly refers to:

* Wells, Somerset, a cathedral city in Somerset, England

* Well, an excavation or structure created in the ground

* Wells (name)

Wells may also refer to:

Places Canada

*Wells, British Columbia

England

* Wells ...

proposed in 1899 that hand axes were used as missile weapons to hunt prey – an interpretation supported by Calvin Calvin may refer to:

Names

* Calvin (given name)

** Particularly Calvin Coolidge, 30th President of the United States

* Calvin (surname)

** Particularly John Calvin, theologian

Places

In the United States

* Calvin, Arkansas, a hamlet

* Calvi ...

, who suggested that some of the rounder specimens of Acheulean hand axes were used as hunting projectiles or as "killer frisbees" meant to be thrown at a herd of animals at a water hole so as to stun one of them. This assertion was inspired by findings from the Olorgesailie

Olorgesailie is a geological formation in East Africa, on the floor of the Eastern Rift Valley in southern Kenya, southwest of Nairobi along the road to Lake Magadi. It contains a group of Lower Paleolithic archaeological sites. Olorgesaili ...

archaeological site in Kenya

)

, national_anthem = "Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

. Few specimens indicate hand axe hafting

Hafting is a process by which an artifact, often bone, stone, or metal is attached to a ''haft'' (handle or strap). This makes the artifact more useful by allowing it to be shot (arrow), thrown by hand (spear), or used with more effective levera ...

, and some are too large for that use. However, few hand axes show signs of heavy damage indicative of throwing, modern experiments have shown the technique to often result in flat-faced landings, and many modern scholars consider the “hurling” theory to be poorly conceived but so attractive that it has taken a life of its own.

As hand axes can be recycled, resharpened and remade, they could have been used for varied tasks. For this reason it may be misleading to think of them as ''axes'', they could have been used for tasks such as digging, cutting, scraping, chopping, piercing and hammering. However, other tools, such as small knives, are better suited for some of these tasks, and many hand axes have been found with no traces of use.

Baker suggested that since so many hand axes have been found that have no retouching, perhaps the hand axe was not itself a tool, but a large lithic core

In archaeology, a lithic core is a distinctive artifact that results from the practice of lithic reduction. In this sense, a core is the scarred nucleus resulting from the detachment of one or more flakes from a lump of source material or too ...

from which flakes had been removed and used as tools (flake core theory). On the other hand, there are many hand axes found with retouching such as sharpening or shaping, which casts doubt on this idea.

Other theories suggest the shape is part tradition and part by-product of its manufacture. Many early hand axes appear to be made from simple rounded pebbles (from river or beach deposits). It is necessary to detach a 'starting flake', often much larger than the rest of the flakes (due to the oblique angle of a rounded pebble requiring greater force to detach it), thus creating an asymmetry. Correcting the asymmetry by removing material from the other faces, encouraged a more pointed (oval) form factor. (Knapping a completely circular hand axe requires considerable correction of the shape.) Studies in the 1990s at Boxgrove, in which a butcher attempted to cut up a carcass with a hand axe, revealed that the hand axe was able to expose bone marrow.

Kohn Kohn is both a first name and a surname. Kohn means cook in Yiddish. It may also be related to Cohen. Notable people with the surname include:

* Angela Kohn ( Jacki-O), rapper

* Arnold Kohn, Croatian Zionist and longtime president of the Jewish c ...

and Mithen independently arrived at the explanation that symmetric hand axes were favoured by sexual selection

Sexual selection is a mode of natural selection in which members of one biological sex mate choice, choose mates of the other sex to mating, mate with (intersexual selection), and compete with members of the same sex for access to members of t ...

as fitness indicators. Kohn in his book ''As We Know It'' wrote that the hand axe is "a highly visible indicator of fitness, and so becomes a criterion of mate choice." Miller

A miller is a person who operates a mill, a machine to grind a grain (for example corn or wheat) to make flour. Milling is among the oldest of human occupations. "Miller", "Milne" and other variants are common surnames, as are their equivalent ...

followed their example and said that hand axes have characteristics that make them subject to sexual selection, such as that they were made for over a million years throughout Africa, Europe and Asia, they were made in large numbers, and most were impractical for utilitarian use. He claimed that a single design persisting across time and space cannot be explained by cultural imitation and draws a parallel between bowerbirds' bowers (built to attract potential mates and used only during courtship) and Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

hominids

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the ...

' hand axes. He called hand axe building a "genetically inherited propensity to construct a certain type of object." He discards the idea that they were used as missile weapons because more efficient weapons were available, such as javelins. Although he accepted that some hand axes may have been used for practical purposes, he agreed with Kohn and Mithen who showed that many hand axes show considerable skill, design and symmetry beyond that needed for utility. Some were too big, such as the “Great Hand Axe” found in Furze Platt, England that is 30.6 cm long(other scholars measure it as 39.5 cm long). Some were too small - less than two inches. Some were “overdetermined”, featuring symmetry beyond practical requirements and showing evidence of unnecessary attention to form and finish. Some were actually made out bone instead of stone and thus were not very practical, suggesting a cultural or ritual use. Miller thinks that the most important clue is that under electron microscopy hand axes show no signs of use or evidence of edge wear. Others argue that little evidence for use-wear simply relates to the particular sedimentological conditions, rather than being evidence of discarding without use. It has been noted that hand axes can be good handicaps in Zahavi's handicap principle

The handicap principle is a hypothesis proposed by the biologist Amotz Zahavi to explain how evolution may lead to "honest" or reliable signalling between animals which have an obvious motivation to bluff or deceive each other. It suggests that ...

theory: learning costs are high, risks of injury, they require physical strength, hand-eye coordination, planning, patience, pain tolerance and resistance to infection from cuts and bruises when making or using such a hand axe.

Evidence from wear analysis

Theuse-wear analysis Use-wear analysis is a method in archaeology to identify the functions of artifact tools by closely examining their working surfaces and edges. It is mainly used on stone tools, and is sometimes referred to as "traceological analysis" (from the neo ...

of Palaeolithic hand axes is carried out on findings from emblematic sites across nearly all of Western Europe. Keeley and Semenov were the pioneers of this specialized investigation. Keeley stated, ''"''The morphology of typical hand axes suggests a greater range of potential activities than those of flakes''"''.

Many problems need to be overcome in carrying out this type of analysis. One is the difficulty in observing larger pieces with a microscope. Of the millions of known pieces and despite their long role in human history, few have been thoroughly studied. Another arises from the clear evidence that the same tasks were performed more effectively using utensils made from flakes:

Keeley based his observations on archaeological sites in England. He proposed that in base settlements where it was possible to predict future actions and where greater control on routine activities was common, the preferred tools were made from specialized flakes, such as racloir

In archaeology, a racloir, also known as ''racloirs sur talon'' (French for scraper on the platform), is a certain type of flint tool made by prehistoric peoples.

It is a type of side scraper distinctive of Mousterian assemblages. It is created ...

s, backed knives, scrapers and punches. However, hand axes were more suitable on expeditions and in seasonal camps, where unforeseen tasks were more common. Their main advantage in these situations was the lack of specialization and adaptability to multiple eventualities. A hand axe has a long blade with different curves and angles, some sharper and others more resistant, including points and notches. All of this is combined in one tool. Given the right circumstances, it is possible to make use of loose flakes. In the same book, Keeley states that a number of the hand axes studied were used as knives to cut meat (such as hand axes from Hoxne

Hoxne ( ) is a village in the Mid Suffolk district of Suffolk, England, about five miles (8 km) east-southeast of Diss, Norfolk and south of the River Waveney. The parish is irregularly shaped, covering the villages of Hoxne, Cross Street ...

and Caddington

Caddington () is a village and civil parish in the Central Bedfordshire district of Bedfordshire, England. It is between the Luton/Dunstable urban area (to the north), and Hertfordshire (to the south).

The western border of the parish is Watlin ...

). He identified that the point of another hand axe had been used as a clockwise drill. This hand axe came from Clacton-on-Sea

Clacton-on-Sea is a seaside town in the Tendring District in the county of Essex, England. It is located on the Tendring Peninsula and is the largest settlement in the Tendring District with a population of 56,874 (2016). The town is situated ...

(all of these sites are located in the east of England). Toth reached similar conclusions for pieces from the Spanish site in Ambrona

Torralba and Ambrona (Province of Soria, Castile and León, Spain) are two paleontological and archaeological sites that correspond to various fossiliferous levels with Acheulean lithic industry ( Lower Paleolithic) associated, at least about 3 ...

(Soria

Soria () is a municipality and a Spanish city, located on the Douro river in the east of the autonomous community of Castile and León and capital of the province of Soria. Its population is 38,881 ( INE, 2017), 43.7% of the provincial populati ...

). Analysis carried out by Domínguez-Rodrigo and co-workers on the primitive Acheulean site in Peninj (Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

) on a series of tools dated 1.5 mya shows clear microwear produced by plant phytolith

Phytoliths (from Greek, "plant stone") are rigid, microscopic structures made of silica, found in some plant tissues and persisting after the decay of the plant. These plants take up silica from the soil, whereupon it is deposited within different ...

s, suggesting that the hand axes were used to work wood. Among other uses, use-wear evidence for fire making

Fire making, fire lighting or fire craft is the process of artificially starting a fire. It requires completing the fire triangle, usually by heating tinder above its autoignition temperature.

Fire is an essential tool for human survival and ...

has been identified on dozens of later Middle Palaeolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle Pale ...

hand axes from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, suggesting Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While th ...

s struck these tools with the mineral pyrite

The mineral pyrite (), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Iron, FeSulfur, S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic Luster (mineralogy), lust ...

to produce sparks at least 50,000 years ago.

Macroscopic traces

Some hand axes were used with force that left clearly visible marks. Other visible marks can be left as the scars from retouching, on occasion it is possible to distinguish them from marks left by the initial manufacture. One of the most common cases is when a point breaks. This was seen at sites in Europe, Africa and Asia. One example comes from the El Basalito site inSalamanca

Salamanca () is a city in western Spain and is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the autonomous community of Castile and León. The city lies on several rolling hills by the Tormes River. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO World Herit ...

, where excavation uncovered fragments of a hand axe with marks at the tip that appeared to be the result of the action of a wedge, which would have subjected the object to high levels of torsion that broke the tip. A break or extreme wear can affect a tool's point or any other part. Such wear was reworked by means of a secondary working as discussed above. In some cases this reconstruction is easily identifiable and was carried out using techniques such as the ''coup de tranchet'' (French, meaning "tranchet In archaeology, a tranchet flake is a characteristic type of flake removed by a flintknapper during lithic reduction. Known as one of the major categories in core-trimming flakes, the making of a tranchet flake involves removing a flake parallel to ...

blow"), or simply with scale or scalariform retouches that alter an edge's symmetry and line.

Forms

The most characteristic and common shape is a pointed area at one end, cutting edges along its side and a rounded base (this includes hand axes with a lanceolate and amygdaloidal shape as well as others from the family). The axes are almost always symmetrical, despite studies showing that symmetry doesn’t help in tasks such as using a hand axe for skinning animals. While there is a “typical” shape to most hand axes, there are some displaying a variety of shapes, including circular, triangular and elliptical—calling in to question the contention that they had a constant and only symbolic significance. They are typically between long, although they can be bigger or smaller.

The most characteristic and common shape is a pointed area at one end, cutting edges along its side and a rounded base (this includes hand axes with a lanceolate and amygdaloidal shape as well as others from the family). The axes are almost always symmetrical, despite studies showing that symmetry doesn’t help in tasks such as using a hand axe for skinning animals. While there is a “typical” shape to most hand axes, there are some displaying a variety of shapes, including circular, triangular and elliptical—calling in to question the contention that they had a constant and only symbolic significance. They are typically between long, although they can be bigger or smaller.

They were typically made from a rounded

They were typically made from a rounded stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

, a block

Block or blocked may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Broadcasting

* Block programming, the result of a programming strategy in broadcasting

* W242BX, a radio station licensed to Greenville, South Carolina, United States known as ''96.3 ...

or lithic flake

In archaeology, a lithic flake is a "portion of rock removed from an objective piece by percussion or pressure,"Andrefsky, W. (2005) ''Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis''. 2d Ed. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press and may also be refe ...

, using a hammer to remove flakes from both sides of the item. This hammer can be made of hard stone, or of wood or antler. The latter two, softer hammers can produce more delicate results. However, a hand axe's technological aspect can reflect more differences. For example, uniface

In archaeology, a uniface is a specific type of stone tool that has been flaked on one surface only. There are two general classes of uniface tools: modified flakes—and formalized tools, which display deliberate, systematic modification of ...

tools have only been worked on one side and partial bifaces retain a high proportion of the natural cortex of the tool stone

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, only human beings, whose use of stone tools dates bac ...

, often making them easy to confuse with chopping tool

In archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and ...

s. Further, simple bifaces may have been created from a suitable tool stone, but they rarely show evidence of retouching. Later hand axes were improved by the use of the Levallois technique

The Levallois technique () is a name given by archaeologists to a distinctive type of stone knapping developed around 250,000 to 300,000 years ago during the Middle Palaeolithic period. It is part of the Mousterian stone tool industry, and was ...

to make the more sophisticated and lighter Levallois core.

In summary, hand axes are recognized by many typological schools under different archaeological paradigms and are quite recognisable (at least the most typical examples). However, they have not been definitively categorized. Stated more formally, the idealised model

A model is an informative representation of an object, person or system. The term originally denoted the plans of a building in late 16th-century English, and derived via French and Italian ultimately from Latin ''modulus'', a measure.

Models c ...

combines a series of well-defined properties

Property is the ownership of land, resources, improvements or other tangible objects, or intellectual property.

Property may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Property (mathematics)

Philosophy and science

* Property (philosophy), in philosophy an ...

, but no set of these properties are necessary or sufficient to identify a hand axe.

History and distribution

In 1969 in the 2nd edition of World Prehistory,Grahame Clark

Sir John Grahame Douglas Clark (28 July 1907 – 12 September 1995), who often published as J. G. D. Clark, was a British archaeologist who specialised in the study of Mesolithic Europe and palaeoeconomics. He spent most of his career working at ...

proposed an evolutionary progression of flint-knapping

Knapping is the shaping of flint, chert, obsidian, or other conchoidal fracturing stone through the process of lithic reduction to manufacture stone tools, strikers for flintlock firearms, or to produce flat-faced stones for building or facing w ...

industries (also known as complexes or technocomplexes) in which the "dominant lithic technologies" occurred in a fixed sequence where simple Oldowan

The Oldowan (or Mode I) was a widespread stone tool archaeological industry (style) in prehistory. These early tools were simple, usually made with one or a few flakes chipped off with another stone. Oldowan tools were used during the Lower ...

one-edged tools were replaced by these more complex Acheulean

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French ''acheuléen'' after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated ...

hand axes, which were then eventually replaced by the even more complex Mousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an archaeological industry of stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and to the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and West Asia. The Mousterian largely defines the l ...

tools made with the Levallois technique

The Levallois technique () is a name given by archaeologists to a distinctive type of stone knapping developed around 250,000 to 300,000 years ago during the Middle Palaeolithic period. It is part of the Mousterian stone tool industry, and was ...

.

The oldest known Oldowan

The Oldowan (or Mode I) was a widespread stone tool archaeological industry (style) in prehistory. These early tools were simple, usually made with one or a few flakes chipped off with another stone. Oldowan tools were used during the Lower ...

tools were found in Gona, Ethiopia

Gona is an archaeological site in the Afar Triangle of Ethiopia located in the Ethiopian Lowlands. The site, near the Middle Awash and Hadar regions, is primarily known for paleoanthropological study, including excavations of Late Miocene and E ...

. These are dated to about 2.6 mya.

Early examples of hand axes date back to 1.6 mya in the later Oldowan (Mode I), called the "developed Oldowan

The Oldowan (or Mode I) was a widespread stone tool archaeological industry (style) in prehistory. These early tools were simple, usually made with one or a few flakes chipped off with another stone. Oldowan tools were used during the Lower ...

" by Mary Leakey

Mary Douglas Leakey, FBA (née Nicol, 6 February 1913 – 9 December 1996) was a British paleoanthropologist who discovered the first fossilised ''Proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a consul. A pro ...

. These hand axes became more abundant in mode II Acheulean

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French ''acheuléen'' after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated ...

industries that appeared in Southern Ethiopia around 1.4 mya. Some of the best specimens come from 1.2 mya deposits in Olduvai Gorge

The Olduvai Gorge or Oldupai Gorge in Tanzania is one of the most important paleoanthropological localities in the world; the many sites exposed by the gorge have proven invaluable in furthering understanding of early human evolution. A steep-si ...

. They are known in Mousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an archaeological industry of stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and to the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and West Asia. The Mousterian largely defines the l ...

industries.

By 1.8 mya early man was present in Europe. Remains of their activities were excavated in Spain at sites in the Guadix-Baza basin and near Atapuerca. Most early European sites yield "mode 1" or Oldowan assemblages. The earliest Acheulean sites in Europe appear around 0.5 mya. In addition, the Acheulean tradition did not spread to Eastern Asia. In Europe and particularly in France and England, the oldest hand axes appear after the Beestonian Glaciation–Mindel Glaciation

The Mindel glaciation (german: Mindel-Kaltzeit, also ''Mindel-Glazial'', ''Mindel-Komplex'' or, colloquially, ''Mindel-Eiszeit'') is the third youngest glacial stage in the Alps. Its name was coined by Albrecht Penck and Eduard Brückner, who nam ...

, approximately 750,000 years ago, during the so-called '' Cromerian complex''. They became more widely produced during the Abbevillian

Abbevillian (formerly also ''Chellean'') is a term for the oldest lithic industry found in Europe, dated to between roughly 600,000 and 400,000 years ago.

The original artifacts were collected from road construction sites on the Somme river near ...

tradition.

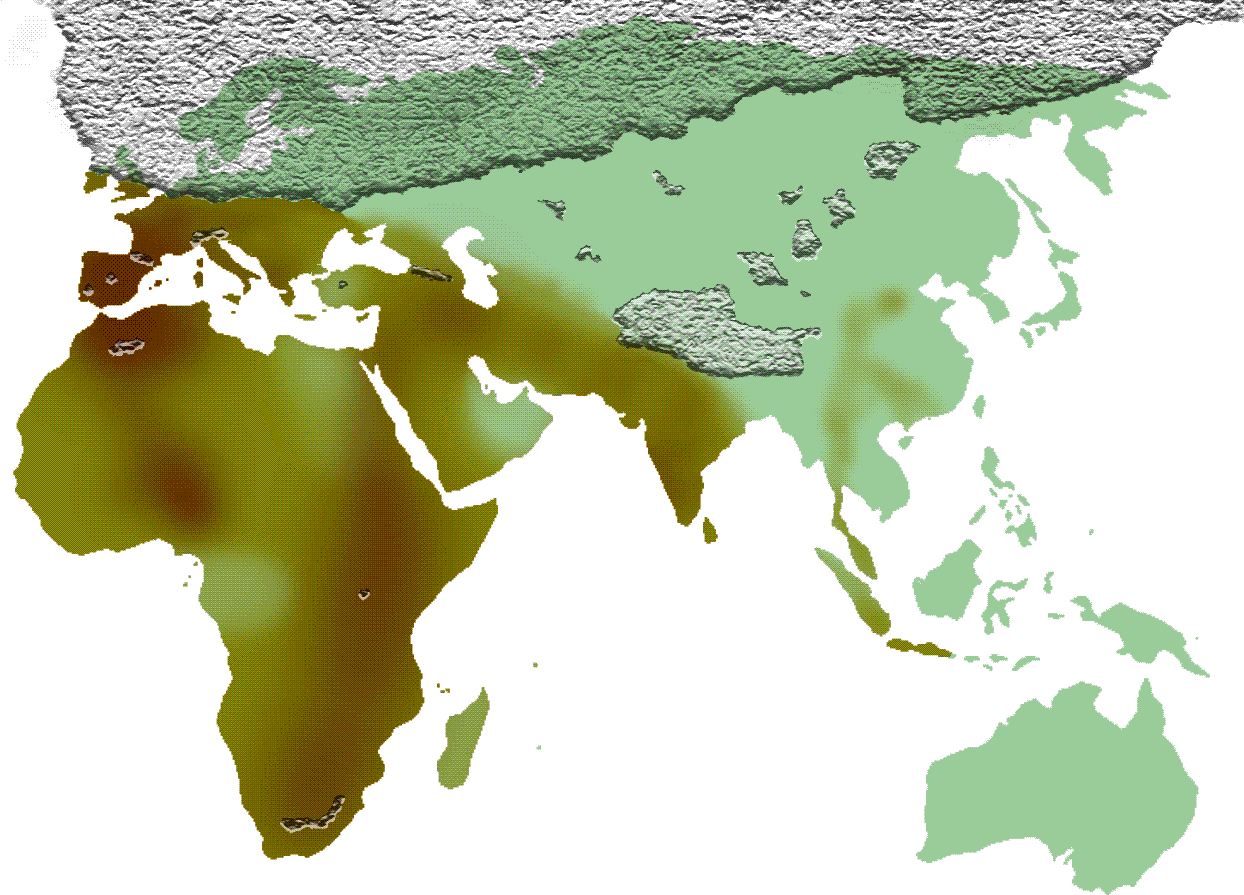

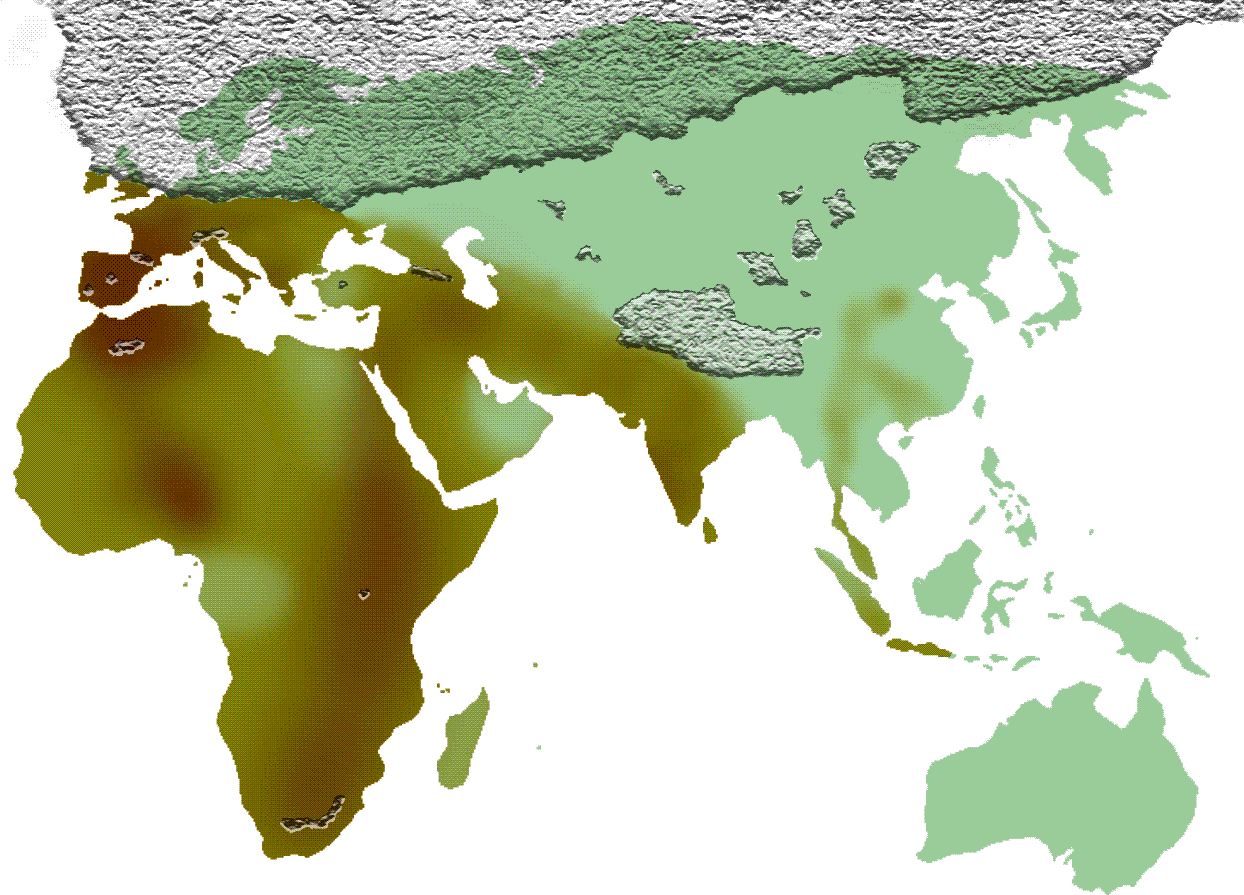

The apogee of hand axe manufacture took place in a wide area of the

The apogee of hand axe manufacture took place in a wide area of the Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by the ...

, especially during the Riss glaciation

The Riss glaciation, Riss Glaciation, Riss ice age, Riss Ice Age, Riss glacial or Riss Glacial (german: Riß-Kaltzeit, ', ' or (obsolete) ') is the second youngest glaciation of the Pleistocene epoch in the traditional, quadripartite glacial classi ...

, in a cultural complex that can be described as ''cosmopolitan'' and which is known as the Acheulean

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French ''acheuléen'' after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated ...

. The use of hand axes survived the Middle Palaeolithic in a much smaller area and were especially important during the Mousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an archaeological industry of stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and to the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and West Asia. The Mousterian largely defines the l ...

, up to the middle of the Last glacial period.

Hand axes dating from the lower Palaeolithic were found on the Asian continent, on the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

and in the Middle East (to the south of parallel 40° N), but they were absent from the area to the east of the 90° E meridian

Meridian or a meridian line (from Latin ''meridies'' via Old French ''meridiane'', meaning “midday”) may refer to

Science

* Meridian (astronomy), imaginary circle in a plane perpendicular to the planes of the celestial equator and horizon

* ...

. Movius designated a border (the so-called Movius Line) between the cultures that used hand axes to the west and those that made chopping tool

In archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and ...

s and small retouched

Photograph manipulation involves the image editing, transformation or alteration of a photograph using various methods and techniques to achieve desired results. Some photograph manipulations are considered to be skillful artwork, while other ...

lithic flake

In archaeology, a lithic flake is a "portion of rock removed from an objective piece by percussion or pressure,"Andrefsky, W. (2005) ''Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis''. 2d Ed. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press and may also be refe ...

s, such as were made by Peking man

Peking Man (''Homo erectus pekinensis'') is a subspecies of '' H. erectus'' which inhabited the Zhoukoudian Cave of northern China during the Middle Pleistocene. The first fossil, a tooth, was discovered in 1921, and the Zhoukoudian Cave has s ...

and the Ordos culture

The Ordos culture () was a material culture occupying a region centered on the Ordos Loop (corresponding to the region of Suiyuan, including Baotou to the north, all located in modern Inner Mongolia, China) during the Bronze and early Iron Age fr ...

in China, or their equivalents in Indochina

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

such as the Hoabinhian

Hoabinhian is a lithic techno-complex of archaeological sites associated with assemblages in Southeast Asia from late Pleistocene to Holocene, dated to c.10,000–2000 BCE. It is attributed to hunter-gatherer societies of the region and their ...

. However, Movius hypothesis was found incorrect when many hand axes made in Palaeolithic era were found in 1978 at Hantan River, Jeongok, Yeoncheon County

Yeoncheon County (''Yeoncheon-gun'') is a county in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. The county seat is Yeoncheon-eup (연천읍) and sits on the Korail railroad line connecting Seoul, South Korea, with North Korea ( DPRK).

History

A variety of pal ...

, South Korea for the first time in East Asia. Some of them are exhibited at the Jeongok Prehistory Museum, South Korea.

The Padjitanian culture from Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's List ...

was traditionally thought to be the only oriental culture to manufacture hand axes. However, a site in Baise

Baise (; local pronunciation: ), or Bose, is the westernmost prefecture-level city of Guangxi, China bordering Vietnam as well as the provinces of Guizhou and Yunnan. The city has a population of 4.3 million, of which 1.4 million live in the ...

, China shows that hand axes were made in eastern Asia.

In North America, hand axes make up one of the dominant tool industries, starting from the terminal Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

and continuing throughout the Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togethe ...

. For example, the Folsom point

Folsom points are projectile points associated with the Folsom tradition of North America. The style of tool-making was named after the Folsom site located in Folsom, New Mexico, where the first sample was found in 1908 by George McJunkin within t ...

and Clovis point traditions (collectively known as the fluted points) are associated with Paleo Indians, some of the first people to colonize the new world

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

. Hand axe technology is almost unknown in Australian prehistory, although a few have been found.

Construction

Experiments inknapping

Knapping is the shaping of flint, chert, obsidian, or other conchoidal fracturing stone through the process of lithic reduction to manufacture stone tools, strikers for flintlock firearms, or to produce flat-faced stones for building or facing ...

have demonstrated the relative ease with which a hand axe can be made, which could help explain their success. In addition, they demand relatively little maintenance and allow a choice of raw materials–any rock will suffice that supports a conchoidal fracture. With early hand axes, it is easy to improvise their manufacture, correct mistakes without requiring detailed planning, and no long or demanding apprenticeship is necessary to learn the necessary techniques. These factors combine to allow these objects to remain in use throughout pre-history. Their adaptability makes them effective in a variety of tasks, from heavy duty such as digging in soil, felling trees or breaking bones to delicate such as cutting ligaments, slicing meat or perforating a variety of materials.

Later examples of hand axes are more sophisticated with their use of two layers of knapping (one made with stone knapping and one made with bone knapping).

Lastly, a hand axe represents a prototype

A prototype is an early sample, model, or release of a product built to test a concept or process. It is a term used in a variety of contexts, including semantics, design, electronics, and Software prototyping, software programming. A prototyp ...

that can be refined giving rise to more developed, specialised and sophisticated tools such as the tips of various projectiles, knives, adzes and hatchets.

Analysis

Given the typological difficulties in defining the essence of a hand axe, it is important when analysing them to take account of their archaeological context (geographical location

In geography, location or place are used to denote a region (point, line, or area) on Earth's surface or elsewhere. The term ''location'' generally implies a higher degree of certainty than ''place'', the latter often indicating an entity with an ...

, stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock (geology), rock layers (Stratum, strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary rock, sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigrap ...

, the presence of other elements associated with the same level

Level or levels may refer to:

Engineering

*Level (instrument), a device used to measure true horizontal or relative heights

*Spirit level, an instrument designed to indicate whether a surface is horizontal or vertical

*Canal pound or level

*Regr ...

, chronology

Chronology (from Latin ''chronologia'', from Ancient Greek , ''chrónos'', "time"; and , '' -logia'') is the science of arranging events in their order of occurrence in time. Consider, for example, the use of a timeline or sequence of events. I ...

etc.). It is necessary to study their physical state to establish any natural alterations that may have occurred: patina, shine, wear and tear, mechanical, thermal and / or physical-chemical changes such as cracking, in order to distinguish these factors from the scars left during the tool's manufacture or use.

The raw material

A raw material, also known as a feedstock, unprocessed material, or primary commodity, is a basic material that is used to produce goods, finished goods, energy, or intermediate materials that are feedstock for future finished products. As feedst ...

is an important factor, because of the result that can be obtained by working it and in order to reveal the economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the ...

and movement of prehistoric humans. In the Olduvai Gorge

The Olduvai Gorge or Oldupai Gorge in Tanzania is one of the most important paleoanthropological localities in the world; the many sites exposed by the gorge have proven invaluable in furthering understanding of early human evolution. A steep-si ...

the raw materials were most readily available some ten kilometres from the nearest settlements. However, flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start fir ...

or silicate is readily available on the fluvial terrace

Fluvial terraces are elongated terraces that flank the sides of floodplains and fluvial valleys all over the world. They consist of a relatively level strip of land, called a "tread", separated from either an adjacent floodplain, other fluvial t ...

s of Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. This means that different strategies were required for the procurement and use of available resources. The supply of materials was the most important factor in the manufacturing process as Palaeolithic artisans were able to adapt their methods to available materials, obtaining adequate results from even the most difficult raw materials. Despite this it is important to study the rock's grain, texture, the presence of joints, veins, impurities or shatter cones etc.

In order to study the use of individual items it is necessary to look for traces of wear such as pseudo-retouches, breakage or wear, including areas that are polished. If the item is in a good condition it is possible to submit it to use-wear analysis Use-wear analysis is a method in archaeology to identify the functions of artifact tools by closely examining their working surfaces and edges. It is mainly used on stone tools, and is sometimes referred to as "traceological analysis" (from the neo ...

, which is discussed in more detail below. Apart from these generalities, which are common to all carved archaeological pieces, hand axes need a technical analysis of their manufacture and a morphological analysis.

Technical analysis

The technical analysis of a hand axe tries to discover each of the phases in its ''chaîne opératoire

Chaîne opératoire (; ) is a term used throughout anthropological discourse, but is most commonly used in archaeology and sociocultural anthropology. It functions as a methodological tool for analysing the technical processes and social acts i ...

'' (operational sequence). The chain is highly flexible, as a toolmaker may focus narrowly on just one of the sequence's links or equally on each link. The links examined in this type of study start with the extraction methods of the raw material, then include the actual manufacture of the item, its use, maintenance throughout its working life, and finally its disposal.

A toolmaker may put a lot of effort into finding the highest quality raw material or the most suitable tool stone. In this way more effort is invested in obtaining a good foundation, but time is saved on shaping the stone: that is, the effort is focused on the start of the operational chain. Equally the artisan may concentrate the most effort in the manufacture so that the quality or suitability of the raw material is less important. This will minimize the initial effort, but will result in a greater effort at the end of the operational chain.

Tool stone and cortex

Hand axes are most commonly made from rounded pebbles or nodules, but many are also made from a large flake. Hand axes made from flakes first appeared at the start of the Acheulean period and became more common with time. Manufacturing a hand axe from a flake is actually easier than from a pebble. It is also quicker, as flakes are more likely to be closer to the desired shape. This allows easier manipulation and fewer knaps are required to finish the tool; it is also easier to obtain straight edges. When analysing a hand axe made from a flake, it should be remembered that its shape was predetermined (by use of the

Hand axes are most commonly made from rounded pebbles or nodules, but many are also made from a large flake. Hand axes made from flakes first appeared at the start of the Acheulean period and became more common with time. Manufacturing a hand axe from a flake is actually easier than from a pebble. It is also quicker, as flakes are more likely to be closer to the desired shape. This allows easier manipulation and fewer knaps are required to finish the tool; it is also easier to obtain straight edges. When analysing a hand axe made from a flake, it should be remembered that its shape was predetermined (by use of the Levallois technique

The Levallois technique () is a name given by archaeologists to a distinctive type of stone knapping developed around 250,000 to 300,000 years ago during the Middle Palaeolithic period. It is part of the Mousterian stone tool industry, and was ...

or Kombewa technique or similar). Notwithstanding this, it is necessary to note a tool's characteristics: type of flake, heel, knap direction.

The natural external cortex or ''rind'' of the tool stone, which is due to erosion and the physical-chemical alterations of weathering

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with water, atmospheric gases, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs ''in situ'' (on site, with little or no movement), ...

, is different from the stone's interior. In the case of chert

Chert () is a hard, fine-grained sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz, the mineral form of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Chert is characteristically of biological origin, but may also occur inorganically as a prec ...

, quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical form ...

or quartzite

Quartzite is a hard, non- foliated metamorphic rock which was originally pure quartz sandstone.Essentials of Geology, 3rd Edition, Stephen Marshak, p 182 Sandstone is converted into quartzite through heating and pressure usually related to tect ...

, this alteration is basically mechanical, and apart from the colour and the wear it has the same characteristics as the interior in terms of hardness

In materials science, hardness (antonym: softness) is a measure of the resistance to localized plastic deformation induced by either mechanical indentation or abrasion. In general, different materials differ in their hardness; for example hard ...

, toughness

In materials science and metallurgy, toughness is the ability of a material to absorb energy and plastically deform without fracturing.limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

cortex that is soft and unsuitable for stone tools. As hand axes are made from a tool stone's core, it is normal to indicate the thickness and position of the cortex in order to better understand the techniques that are required in their manufacture. The variation in cortex between utensils should not be taken as an indication of their age.

Many partially-worked hand axes do not require further work in order to be effective tools. They can be considered to be simple hand axes. Less suitable tool stone requires more thorough working. In some specimens the cortex is unrecognisable due to the complete working that it has undergone, which has eliminated any vestige of the original cortex.

Types