Habsburg Empire Of Charles V on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Empire of Charles V, also known by the umbrella term

Charles of

Charles of

Habsburg Empire

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

and labelled "the empire on which the sun never sets

The phrase "the empire on which the sun never sets" ( es, el imperio donde nunca se pone el sol) was used to describe certain global empires that were so extensive that it seemed as though it was always daytime in at least one part of its territ ...

", included the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, the Spanish empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

, the Burgundian Low Countries

The Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries consisted of numerous fiefs held by the Dukes of Burgundy in modern-day Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, and in parts of France and Germany. The Duke of Burgundy was originally a member of the Hous ...

, the Austrian lands, and all the territories and dominions ruled in personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

by Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infan ...

from 1519 to 1556. The lands of the empire had in common only the monarch, Charles V, while their boundaries, institutions, and laws remained distinct. Charles's nomenclature as Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

was ''Charles V'' (also ''Karl V'' and ''Carolus V''), though earlier in his life he was known by the names of ''Charles of Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded in ...

'' (after his birthplace in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

), ''Charles II'' as Duke of Burgundy

Duke of Burgundy (french: duc de Bourgogne) was a title used by the rulers of the Duchy of Burgundy, from its establishment in 843 to its annexation by France in 1477, and later by Holy Roman Emperors and Kings of Spain from the House of Habsburg ...

, and ''Charles I'' as King of Spain

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

(''Carlos I'') and Archduke of Austria

This is a list of people who have ruled either the Margraviate of Austria, the Duchy of Austria or the Archduchy of Austria. From 976 until 1246, the margraviate and its successor, the duchy, was ruled by the House of Babenberg. At that time, t ...

(''Karl I''). The imperial name prevailed due to the politico-religious primacy held by the Holy Roman Empire among European monarchies since the Middle Ages, which Charles V intended to preserve as part of his (ultimately failed) project to unite Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

under his leadership.Blockmans, W. P., and Nicolette Mout. The World of Emperor Charles V (2005) Charles V inherited the states comprising his empire, engaged in extensive warfare during his reign, especially against Francis I of France

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once ...

, Francis I's Muslim ally, Ottoman ruler Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ� ...

, and the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

of Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

. His empire expanded in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

with the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, also known as the Conquest of Mexico or the Spanish-Aztec War (1519–21), was one of the primary events in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. There are multiple 16th-century narratives of the eve ...

and the Inca empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The admin ...

, bringing him great wealth which allowed him to wage war in Europe. He entrusted oversight of his realms to his close relatives, especially his younger brother Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

, who became Holy Roman Emperor, and his son Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

. Charles V abdicated after formally dividing the component states of his empire, with the German states going to his brother; Spain and the Low Countries to his son.

Birth and inheritances of Charles V

Heritage

Charles of

Charles of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

was born on 24 February 1500 in the Prinsenhof

The Prinsenhof ("The Court of the Prince") in the city of Delft in the Netherlands is an urban palace built in the Middle Ages as a monastery. Later it served as a residence for William the Silent. William was assassinated in the Prinsenhof by ...

of Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded in ...

, a Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

city of the Burgundian Low Countries

The Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries consisted of numerous fiefs held by the Dukes of Burgundy in modern-day Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, and in parts of France and Germany. The Duke of Burgundy was originally a member of the Hous ...

, to Philip of Habsburg and Joanna of Trastámara.''Emperor Charles V: The Growth and Destiny of a Man and of a World-empire'', Karl Brandi

Karl Maria Prosper Laurenz Brandi (20 May 1868 – 9 March 1946) was a German historian.

In 1890–91, he wrote his dissertation on the Reichenauer documents: ''Die Reichenauer Urkundenfälschungen'', which served as Volume 1 of ''Quellen un ...

His father Philip, nicknamed ''Philip the Handsome'', was the firstborn son of Maximilian I of Habsburg

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death. He was never crowned by the pope, as the journey to Rome was blocked by the Venetians. He proclaimed himself Ele ...

, Archduke of Austria

This is a list of people who have ruled either the Margraviate of Austria, the Duchy of Austria or the Archduchy of Austria. From 976 until 1246, the margraviate and its successor, the duchy, was ruled by the House of Babenberg. At that time, t ...

as well as Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

, and Mary the Rich

Mary (french: Marie; nl, Maria; 13 February 1457 – 27 March 1482), nicknamed the Rich, was a member of the House of Valois-Burgundy who ruled a collection of states that included the duchies of Limburg, Brabant, Luxembourg, the counties of ...

, Burgundian duchess of the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

. His mother Joanna, known as ''Joanna the Mad'' for the mental disorders afflicting her, was a daughter of Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

and Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as List of Aragonese royal consorts, Queen consort ...

, the Catholic Monarchs of Spain

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being both ...

from the House of Trastámara

The House of Trastámara (Spanish, Aragonese and Catalan: Casa de Trastámara) was a royal dynasty which first ruled in the Crown of Castile and then expanded to the Crown of Aragon in the late middle ages to the early modern period.

They were a ...

. The political marriage of Philip and Joanna was first conceived in a letter sent by Maximilian to Ferdinand in order to seal an Austro-Spanish alliance, established as part of the ''League of Venice

League or The League may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Leagues'' (band), an American rock band

* ''The League'', an American sitcom broadcast on FX and FXX about fantasy football

Sports

* Sports league

* Rugby league, full contact footba ...

'' directed against the Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

during the Italian Wars

The Italian Wars, also known as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a series of conflicts covering the period 1494 to 1559, fought mostly in the Italian peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and the Mediterranean Sea. The pr ...

.''Emperor, a new life of Charles V'', Geoffrey Parker

The organization of ambitious political marriages reflected Maximilian's practice to expand the House of Habsburg with dynastic links rather than conquest, as exemplified by his saying "''Let others wage war, you, happy Austria, marry''". The marriage contract

''Marriage Contract'' () is a 2016 Korean drama, South Korean television series starring Lee Seo-jin and Uee. It aired on Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation, MBC from March 5 to April 24, 2016 on Saturdays and Sundays at 22:00 for 16 episodes.

Pl ...

between Philip and Joanna was signed in 1495, and celebrations were held in 1496. Philip was already Duke of Burgundy

Duke of Burgundy (french: duc de Bourgogne) was a title used by the rulers of the Duchy of Burgundy, from its establishment in 843 to its annexation by France in 1477, and later by Holy Roman Emperors and Kings of Spain from the House of Habsburg ...

, given Mary's death in 1482, and also heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

of Austria as honorific Archduke

Archduke (feminine: Archduchess; German: ''Erzherzog'', feminine form: ''Erzherzogin'') was the title borne from 1358 by the Habsburg rulers of the Archduchy of Austria, and later by all senior members of that dynasty. It denotes a rank within ...

. Joanna, on the other hand, was only third in the Spanish line of succession

An order of succession or right of succession is the line of individuals necessitated to hold a high office when it becomes vacated such as head of state or an honour such as a title of nobility.John of Castile and older sister Isabella of Aragon. Although both John and Isabella died in 1498, the Catholic Monarchs desired to keep the Spanish kingdoms in Iberian hands and designated their Portuguese nephew  In 1501, Philip and Joanna left Charles to the custody of

In 1501, Philip and Joanna left Charles to the custody of

The

The

Spanish kingdoms varied in their style and traditions. Castile was an increasingly authoritarian state where the monarch's own will easily overrode legislative and justice institutions. Its crown comprised most of Spain, including the Iberian

Spanish kingdoms varied in their style and traditions. Castile was an increasingly authoritarian state where the monarch's own will easily overrode legislative and justice institutions. Its crown comprised most of Spain, including the Iberian  At his arrival in Spain, Charles was seen as a foreign prince of Flemish-Austrian background and his Burgundian-Habsburg entourage was accused to exploit the resources and offices of the Spanish kingdoms. For this reason, and due to the irregularities of Charles assuming the royal title while his mother was alive, the negotiations with the Castilian ''Cortes'' in Valladolid proved difficult. Eventually, the Cortes accepted Charles as king and paid homage to him in Valladolid in February 1518. Charles proceeded to Aragon and, once again, he managed to overcome the resistance of the Aragonese ''Cortes'' in order to be recognized as king. A year later, he was still negotiating with the Catalan ''Corts'' to be recognized as count of Barcelona and had not attended, despite requested, similar ceremonies in Valencia and Navarre, causing some grievances. By 1519, the ''Cortes'' of Castile and Aragon imposed the following conditions on Charles: he would learn to speak

At his arrival in Spain, Charles was seen as a foreign prince of Flemish-Austrian background and his Burgundian-Habsburg entourage was accused to exploit the resources and offices of the Spanish kingdoms. For this reason, and due to the irregularities of Charles assuming the royal title while his mother was alive, the negotiations with the Castilian ''Cortes'' in Valladolid proved difficult. Eventually, the Cortes accepted Charles as king and paid homage to him in Valladolid in February 1518. Charles proceeded to Aragon and, once again, he managed to overcome the resistance of the Aragonese ''Cortes'' in order to be recognized as king. A year later, he was still negotiating with the Catalan ''Corts'' to be recognized as count of Barcelona and had not attended, despite requested, similar ceremonies in Valencia and Navarre, causing some grievances. By 1519, the ''Cortes'' of Castile and Aragon imposed the following conditions on Charles: he would learn to speak

After Maximilian's death on 12 January 1519, Charles became

After Maximilian's death on 12 January 1519, Charles became  On 28 June 1519, Charles was elected

On 28 June 1519, Charles was elected

On 26 October 1520, Charles V was crowned

On 26 October 1520, Charles V was crowned

Charles V ratified the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, and would also oversee the beginning of the

Charles V ratified the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, and would also oversee the beginning of the

At the Diet of Worms, the

At the Diet of Worms, the

During the voyage from the Low Countries to Spain, Charles V visited England. His aunt,

During the voyage from the Low Countries to Spain, Charles V visited England. His aunt,  In Spain, Charles V reformed the administration following the Flemish conciliar system and created collateral councils, in addition to those established by Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon, such as the Council of Finance (''Consejo de Hacienda'') in 1523, the Council of the Indies (''Consejo de las Indias'') in 1524, the Council of War (''Consejo de Guerra'') in 1526, and the Council of State (''Consejo de Estado'') in 1527. Similarly, Ferdinand was instructed to establish collateral councils in Austria such as the Privy Council (''Geheimer Rat''), the Aulic Council (''Hofrat''), the Court Chancellery (''Hofkanzlei'') and the Court Exchequer (''Hofkammer''). A regency council was also established in Germany, set up in the context of the

In Spain, Charles V reformed the administration following the Flemish conciliar system and created collateral councils, in addition to those established by Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon, such as the Council of Finance (''Consejo de Hacienda'') in 1523, the Council of the Indies (''Consejo de las Indias'') in 1524, the Council of War (''Consejo de Guerra'') in 1526, and the Council of State (''Consejo de Estado'') in 1527. Similarly, Ferdinand was instructed to establish collateral councils in Austria such as the Privy Council (''Geheimer Rat''), the Aulic Council (''Hofrat''), the Court Chancellery (''Hofkanzlei'') and the Court Exchequer (''Hofkammer''). A regency council was also established in Germany, set up in the context of the

Charles V and some of his principal counselors were informed of the victorious

Charles V and some of his principal counselors were informed of the victorious

p. 192

/ref>Froude (1891)

p. 35, pp. 90–91, pp. 96–97

Note: the link goes to page 480, then click the View All option

The Ottoman sultan

The Ottoman sultan

However, Clement VII went to

However, Clement VII went to

As the last

As the last

In the aftermath of these events, two French ambassadors to Constantinople, Antonio Rincon and Cesare Fregoso, were killed by Charles's agents in Italy. A new French-Imperial war thus broke out in 1542. After passing the New Laws to reform the encomienda system, considered brutal by figures such as Bartolomé de las Casas, (a conference in Valladolid, inclusive of de Las Casas, was finally convened in 1550 Valladolid debate, to debate the morality on the use of force against the Indios) and leaving detailed instructions concerning the government of Spain to his son Philip, Charles V returned in 1543 to the Holy Roman Empire and there remained until the end of his reign. At a meeting in Busseto, he and Paul III agreed on Trento, Trent, located halfway between Italy and Germany, as the location of the future ecumenical council.

In alliance with

In the aftermath of these events, two French ambassadors to Constantinople, Antonio Rincon and Cesare Fregoso, were killed by Charles's agents in Italy. A new French-Imperial war thus broke out in 1542. After passing the New Laws to reform the encomienda system, considered brutal by figures such as Bartolomé de las Casas, (a conference in Valladolid, inclusive of de Las Casas, was finally convened in 1550 Valladolid debate, to debate the morality on the use of force against the Indios) and leaving detailed instructions concerning the government of Spain to his son Philip, Charles V returned in 1543 to the Holy Roman Empire and there remained until the end of his reign. At a meeting in Busseto, he and Paul III agreed on Trento, Trent, located halfway between Italy and Germany, as the location of the future ecumenical council.

In alliance with

The Council of Trent was re-opened by the new Pope, Pope Julius III, Julius III, in 1550. This time the Lutherans were also represented. Charles V set up the Imperial court in

The Council of Trent was re-opened by the new Pope, Pope Julius III, Julius III, in 1550. This time the Lutherans were also represented. Charles V set up the Imperial court in

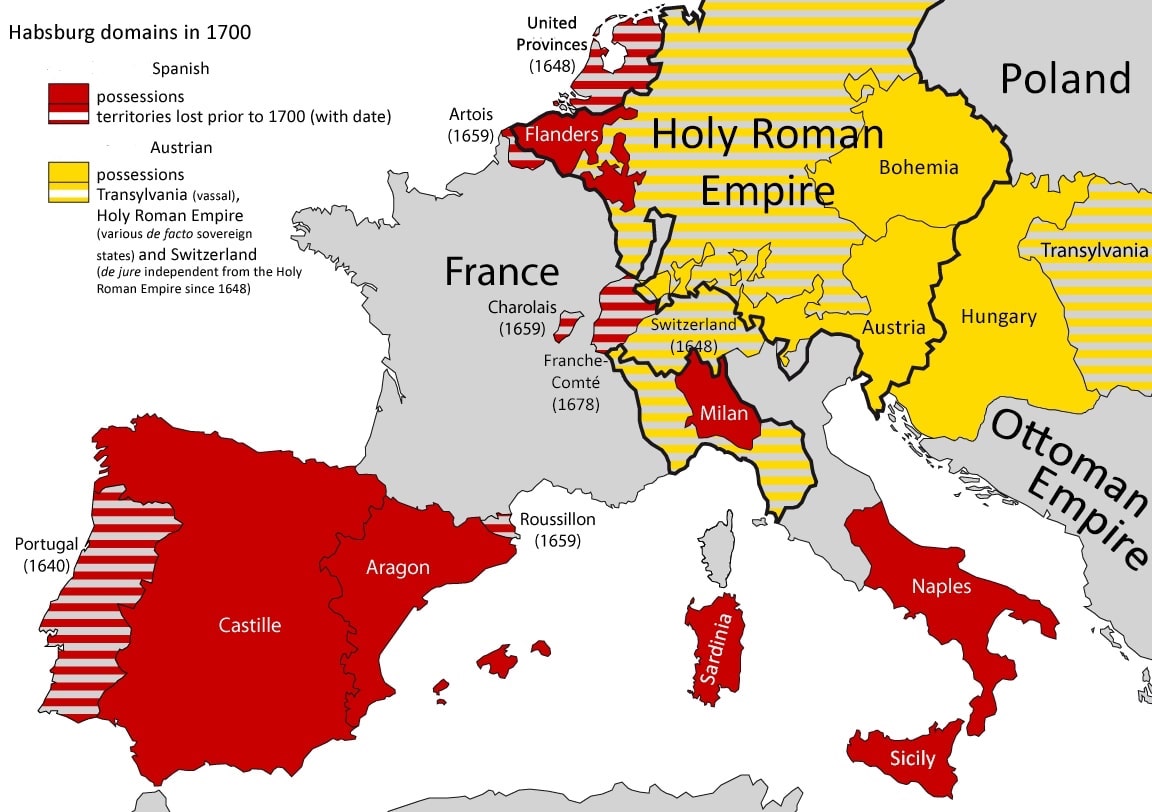

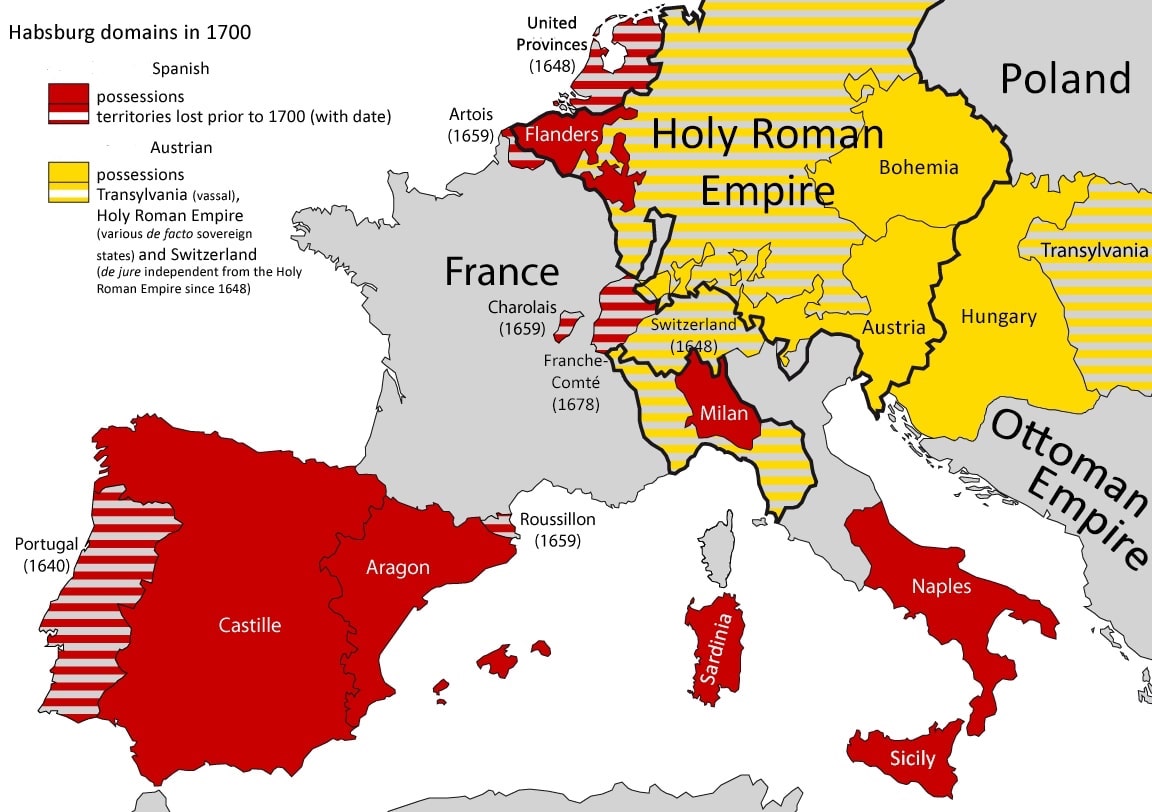

In 1556, with no fanfare, Charles V finalized his abdications. On 16 January 1556, he gave Spain and the

In 1556, with no fanfare, Charles V finalized his abdications. On 16 January 1556, he gave Spain and the

online

* Espinosa, Aurelio. "The Grand Strategy of Charles V (1500–1558): Castile, War, and Dynastic Priority in the Mediterranean", ''Journal of Early Modern History'' (2005) 9#3 pp 239–283

online

* Espinosa, Aurelio. "The Spanish Reformation: Institutional Reform, Taxation, and the Secularization of Ecclesiastical Properties under Charles V", ''Sixteenth Century Journal'' (2006) 37#1 pp 3–24. . * Espinosa, Aurelio. ''The Empire of the Cities: Emperor Charles V, the Comunero Revolt, and the Transformation of the Spanish System'' (2008) * Ferer, Mary Tiffany. ''Music and Ceremony at the Court of Charles V: The Capilla Flamenca and the Art of Political Promotion'' (Boydell & Brewer, 2012). * * * Headley, John M. ''Emperor & His Chancellor: A Study of the Imperial Chancellery under Gattinara'' (1983) covers 1518 to 1530. * Heath, Richard. ''Charles V: Duty and Dynasty. The Emperor and his Changing World 1500–1558.'' (2018) * * Kleinschmidt, Harald. ''Charles V: The World Emperor'' * Merriman, Roger Bigelow. ''The rise of the Spanish empire in the Old world and the New: Volume 3 The Emperor'' (1925

online

* Norwich, John Julius. ''Four Princes: Henry VIII, Francis I, Charles V, Suleiman the Magnificent and the Obsessions that Forged Modern Europe'' (2017), popular history

excerpt

* Parker, Geoffrey. ''Emperor: A New Life of Charles V'' (2019

excerpt

* Reston Jr, James. ''Defenders of the Faith: Charles V, Suleyman the Magnificent, and the Battle for Europe, 1520–1536'' (2009), popular history. * Richardson, Glenn. ''Renaissance Monarchy: The Reigns of Henry VIII, Francis I & Charles V'' (2002) 246 pp. covers 1497 to 1558. * Rodriguez-Salgado, Mia. ''Changing Face of Empire: Charles V, Philip II & Habsburg Authority, 1551–1559'' (1988), 375pp. * Rosenthal, Earl E. ''Palace of Charles V in Granada'' (1986) 383pp. * Saint-Saëns, Alain, ed. ''Young Charles V''. (New Orleans: University Press of the South, 2000). * Tracy, James D. ''Emperor Charles V, impresario of war: campaign strategy, international finance, and domestic politics'' (Cambridge UP, 2002)

excerpt

* Salvatore Agati (2009). ''Carlo V e la Sicilia. Tra guerre, rivolte, fede e ragion di Stato'', Giuseppe Maimone Editore, Catania 2009, * D'Amico, Juan Carlos. ''Charles Quint, Maître du Monde: Entre Mythe et Realite'' 2004, 290p. * Norbert Conrads: ''Die Abdankung Kaiser Karls V.'' Abschiedsvorlesung, Universität Stuttgart, 2003

text

) * Stephan Diller, Joachim Andraschke, Martin Brecht: ''Kaiser Karl V. und seine Zeit''. Ausstellungskatalog. Universitäts-Verlag, Bamberg 2000, * Alfred Kohler: ''Karl V. 1500–1558. Eine Biographie''. C. H. Beck, München 2001, * Alfred Kohler: ''Quellen zur Geschichte Karls V.'' Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1990, * Alfred Kohler, Barbara Haider. Christine Ortner (Hrsg): ''Karl V. 1500–1558. Neue Perspektiven seiner Herrschaft in Europa und Übersee''. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien 2002, * Ernst Schulin: ''Kaiser Karl V. Geschichte eines übergroßen Wirkungsbereichs''. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 1999, * Ferdinant Seibt: ''Karl V.'' Goldmann, München 1999, * Manuel Fernández Álvarez: ''Imperator mundi: Karl V. – Kaiser des Heiligen Römischen Reiches Deutscher Nation.''. Stuttgart 1977, {{DEFAULTSORT:Charles 05, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, 16th century in the Holy Roman Empire 16th century in the Habsburg Netherlands 16th century in the Netherlands 16th century in Spain Habsburg monarchy

Miguel da Paz

Miguel da Paz, Hereditary Prince of Portugal and Prince of Asturias ( pt, Miguel da Paz de Trastâmara e Avis, ; es, Miguel de la Paz de Avís y Trastámara, "Michael of Peace") (23 August 1498 – 19 July 1500) was a Portuguese royal princ ...

as heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of an heir apparent or a new heir presumptive with a better claim to the position in question.

...

of Spain by naming him Prince of the Asturias

Prince or Princess of Asturias ( es, link=no, Príncipe/Princesa de Asturias; ast, Príncipe d'Asturies) is the main substantive title used by the heir apparent or heir presumptive to the throne of Spain. According to the Spanish Constitution ...

. Only a series of dynastic accidents eventually favored Maximilian's project.

Charles was given birth in a bathroom of the Prinsenhof at 3:00 AM by Joanna not long after she attended a ball

A ball is a round object (usually spherical, but can sometimes be ovoid) with several uses. It is used in ball games, where the play of the game follows the state of the ball as it is hit, kicked or thrown by players. Balls can also be used f ...

despite symptoms of labor pains, and his name was chosen by Philip in honour of Charles I of Burgundy

Charles I (Charles Martin; german: Karl Martin; nl, Karel Maarten; 10 November 1433 – 5 January 1477), nicknamed the Bold (German: ''der Kühne''; Dutch: ''de Stoute''; french: le Téméraire), was Duke of Burgundy from 1467 to 1477.

...

. According to a poet at the court, the people of Ghent ''"shouted Austria and Burgundy throughout the whole city for three hours"'' to celebrate his birth. Given the dynastic situation, the newborn was originally heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

only of the Burgundian Low Countries as the honorific Duke of Luxembourg

The territory of Luxembourg has been ruled successively by counts, dukes and grand dukes. It was part of the medieval Kingdom of Germany, and later the Holy Roman Empire until it became a sovereignty, sovereign state in 1815.

Counts of Luxembourg

...

and became known in his early years simply as ''Charles of Ghent''. He was baptized at the Saint Bavo's Cathedral by the Bishop of Tournai

The Diocese of Tournai is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Belgium. The diocese was formed in 1146, upon the dissolution of the Diocese of Noyon & Tournai, which had existed since the 7th Century. It is ...

: Charles I de Croÿ

Charles I de Croÿ (1455–1527), Count and later 1st Prince of Chimay, was a nobleman and politician from the Low Countries in the service of the House of Habsburg.

Career

Charles was born in the House of Croÿ as eldest son of Philip I of Croÿ- ...

and John III of Glymes

John III, Lord of Bergen op Zoom or John III of Glymes (1452 – 1532, in Brussels) was a noble from the Low Countries.

He was the son of John II of Glymes and Margaret of Rouveroy and succeeded his father as Lord of Bergen op Zoom. In 1494 he ...

were his godfathers; Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy

Margaret of York (3 May 1446 – 23 November 1503)—also by marriage known as Margaret of Burgundy—was Duchess of Burgundy as the third wife of Charles the Bold and acted as a protector of the Burgundian State after his death. She was a daught ...

and Margaret of Austria, Duchess of Savoy

Archduchess Margaret of Austria (german: Margarete; french: Marguerite; nl, Margaretha; es, Margarita; 10 January 1480 – 1 December 1530) was Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands from 1507 to 1515 and again from 1519 to 1530. She was the firs ...

his godmothers. Charles's baptism gifts were a sword and a helmet, objects of Burgundian chivalric tradition representing, respectively, the instrument of war and the symbol of peace.

Margaret of York

Margaret of York (3 May 1446 – 23 November 1503)—also by marriage known as Margaret of Burgundy—was Duchess of Burgundy as the third wife of Charles the Bold and acted as a protector of the Burgundian State after his death. She was a daught ...

and went to Spain. They returned to visit their son very rarely, and thus Charles grew up in the Low Countries practically without his parents. The main goal of their Spanish mission was the recognition of Joanna as Princess of Asturias

Prince or Princess of Asturias ( es, link=no, Príncipe/Princesa de Asturias; ast, Príncipe d'Asturies) is the main substantive title used by the heir apparent or heir presumptive to the monarchy of Spain, throne of Spain. According to the Sp ...

, given prince Miguel's death a year earlier. They succeeded despite facing some opposition from the Spanish ''Cortes'', reluctanct to create the premises for Habsburg succession. In 1504, as Isabella passed away, Joanna became Queen of Castile

This is a list of kings and queens of the Kingdom of Castile, Kingdom and Crown of Castile. For their predecessors, see List of Castilian counts.

Kings and Queens of Castile

Jiménez dynasty

House of Ivrea

The following dynasts are de ...

. Philip was recognized King in 1506 but died shortly after, an event that drove the mentally unstable Joanna into complete insanity. She retired in isolation into a tower of Tordesillas

Tordesillas () is a town and municipality in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, central Spain. It is located southwest of the provincial capital, Valladolid at an elevation of . The population was c. 9,000 .

The town is located ...

. Ferdinand took control of all the Spanish kingdoms, under the pretext of protecting Charles's rights, which in reality he wanted to elude, but his new marriage with Germaine de Foix

Ursula Germaine of Foix (french: Ursule-Germaine de Foix; ca, Úrsula Germana de Foix; ; c. 1488 – 15 October 1536) was an early modern French noblewoman from the House of Foix. By marriage to King Ferdinand II of Aragon, she was Queen of A ...

failed to produce a surviving Trastámara heir to the throne. With his father dead and his mother confined, Charles became Duke of Burgundy and was recognized as prince of Asturias

Prince or Princess of Asturias ( es, link=no, Príncipe/Princesa de Asturias; ast, Príncipe d'Asturies) is the main substantive title used by the heir apparent or heir presumptive to the monarchy of Spain, throne of Spain. According to the Sp ...

(heir presumptive of Spain) and honorific archduke

Archduke (feminine: Archduchess; German: ''Erzherzog'', feminine form: ''Erzherzogin'') was the title borne from 1358 by the Habsburg rulers of the Archduchy of Austria, and later by all senior members of that dynasty. It denotes a rank within ...

(heir apparent of Austria).

Low Countries

The

The Burgundian Low Countries

The Burgundian inheritance in the Low Countries consisted of numerous fiefs held by the Dukes of Burgundy in modern-day Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, and in parts of France and Germany. The Duke of Burgundy was originally a member of the Hous ...

, also called "Netherlands", "Flanders", or "Belgica", were Charles's homeland and originally included Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

, Artois

Artois ( ; ; nl, Artesië; English adjective: ''Artesian'') is a region of northern France. Its territory covers an area of about 4,000 km2 and it has a population of about one million. Its principal cities are Arras (Dutch: ''Atrecht'') ...

, Brabant Brabant is a traditional geographical region (or regions) in the Low Countries of Europe. It may refer to:

Place names in Europe

* London-Brabant Massif, a geological structure stretching from England to northern Germany

Belgium

* Province of Bra ...

, Limburg

Limburg or Limbourg may refer to:

Regions

* Limburg (Belgium), a province since 1839 in the Flanders region of Belgium

* Limburg (Netherlands), a province since 1839 in the south of the Netherlands

* Diocese of Limburg, Roman Catholic Diocese in ...

, Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

, Hainaut, Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former province on the western coast of the Netherlands. From the 10th to the 16th c ...

, Namir

Namir is a town in south-western Yemen. It is located in the Abyan Governorate

Abyan ( ar, أَبْيَن ) is a governorate of Yemen. The Abyan region was historically part of the Fadhli Sultanate. It was a base to the Aden-Abyan Islamic ...

, Mechelen

Mechelen (; french: Malines ; traditional English name: MechlinMechelen has been known in English as ''Mechlin'', from where the adjective ''Mechlinian'' is derived. This name may still be used, especially in a traditional or historical contex ...

, and Zeeland

, nl, Ik worstel en kom boven("I struggle and emerge")

, anthem = "Zeeuws volkslied"("Zeelandic Anthem")

, image_map = Zeeland in the Netherlands.svg

, map_alt =

, m ...

. Charles inherited those territories, as well as the exclaves of Franche-Comté

Franche-Comté (, ; ; Frainc-Comtou: ''Fraintche-Comtè''; frp, Franche-Comtât; also german: Freigrafschaft; es, Franco Condado; all ) is a cultural and historical region of eastern France. It is composed of the modern departments of Doubs, ...

and Charolais, when his father Philip died. On 15 October 1506, he was named Lord of the Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands was the Renaissance period fiefs in the Low Countries held by the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. The rule began in 1482, when the last Valois-Burgundy ruler of the Netherlands, Mary, wife of Maximilian I of Austria, ...

as Duke ''Charles II of Burgundy'' by the parliamentary body of the States General The word States-General, or Estates-General, may refer to:

Currently in use

* Estates-General on the Situation and Future of the French Language in Quebec, the name of a commission set up by the government of Quebec on June 29, 2000

* States Genera ...

. The remaining provinces of the Low Countries, initially outside of Charles's jurisdiction, were Guelders

The Duchy of Guelders ( nl, Gelre, french: Gueldre, german: Geldern) is a historical duchy, previously county, of the Holy Roman Empire, located in the Low Countries.

Geography

The duchy was named after the town of Geldern (''Gelder'') in pr ...

, Friesland

Friesland (, ; official fry, Fryslân ), historically and traditionally known as Frisia, is a province of the Netherlands located in the country's northern part. It is situated west of Groningen, northwest of Drenthe and Overijssel, north of ...

, Utrecht

Utrecht ( , , ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city and a List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, capital and most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, pro ...

, Overijssel

Overijssel (, ; nds, Oaveriessel ; german: Oberyssel) is a Provinces of the Netherlands, province of the Netherlands located in the eastern part of the country. The province's name translates to "across the IJssel", from the perspective of the ...

, Groningen

Groningen (; gos, Grunn or ) is the capital city and main municipality of Groningen province in the Netherlands. The ''capital of the north'', Groningen is the largest place as well as the economic and cultural centre of the northern part of t ...

, Drenthe

Drenthe () is a province of the Netherlands located in the northeastern part of the country. It is bordered by Overijssel to the south, Friesland to the west, Groningen to the north, and the German state of Lower Saxony to the east. As of Nov ...

, and Zutphen

Zutphen () is a city and municipality located in the province of Gelderland, Netherlands. It lies some 30 km northeast of Arnhem, on the eastern bank of the river Ijssel at the point where it is joined by the Berkel. First mentioned in the 1 ...

. Another territory not included in the Burgundian inheritance was Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

proper, annexed by France in 1477. As a young lord, Charles grew up with two major political goals: recover Burgundy proper and unite the seventeen provinces

The Seventeen Provinces were the Imperial states of the Habsburg Netherlands in the 16th century. They roughly covered the Low Countries, i.e., what is now the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and most of the French departments of Nord (Fre ...

of the Low Countries under sole Habsburg rule. By the end of his reign, he would have failed in the former objective but succeeded in the latter.

The Low Countries held an important place in Europe for their strategic location, and the wealthy Flemish cities were flourishing in trade and experiencing a transition to capitalism. Although located within the Holy Roman Empire and its borders, those territories were formally divided between fiefs of the German kingdom

The Kingdom of Germany or German Kingdom ( la, regnum Teutonicorum "kingdom of the Germans", "German kingdom", "kingdom of Germany") was the mostly Germanic-speaking East Frankish kingdom, which was formed by the Treaty of Verdun in 843, especi ...

and French fiefs (such as Charles's birthplace of Flanders) and thus formed, as Henri Pirenne

Henri Pirenne (; 23 December 1862 – 24 October 1935) was a Belgian historian. A medievalist of Walloon descent, he wrote a multivolume history of Belgium in French and became a prominent public intellectual. Pirenne made a lasting contributio ...

put it, "a state made up of the frontier provinces of two kingdoms". Given that Charles ascended to the ducal throne as a minor, Emperor Maximilian appointed Margaret of Austria, Duchess of Savoy

Archduchess Margaret of Austria (german: Margarete; french: Marguerite; nl, Margaretha; es, Margarita; 10 January 1480 – 1 December 1530) was Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands from 1507 to 1515 and again from 1519 to 1530. She was the firs ...

(Charles's aunt and Maximilian's daughter) as his guardian and regent. Charles viewed and treated Margaret as his mother and grew up in her palace of Mechelen along with his sisters. Margaret soon found herself in conflict with France over the question of Charles's requirement to pay homage to the French king in his position as Duke of Burgundy and Count of Flanders.

Charles's entourage, which consisted of hundreds of members, was composed primarily of fellow countrymen such as his chamberlain William de Croÿ

William II de Croÿ, Lord of Chièvres (1458 – 28 May 1521) (also known as: Guillaume II de Croÿ, sieur de Chièvres in French; Guillermo II de Croÿ, señor de Chièvres, Xevres or Xebres in Spanish; Willem II van Croÿ, heer van Chiè ...

and his tutor Adrian of Utrecht

Pope Adrian VI ( la, Hadrianus VI; it, Adriano VI; nl, Adrianus/Adriaan VI), born Adriaan Florensz Boeyens (2 March 1459 – 14 September 1523), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 January 1522 until his d ...

. Because of this, the young duke grew up speaking exclusively his native languages: French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

. Very important to Charles was the Burgundian Order of the Golden Fleece

The Distinguished Order of the Golden Fleece ( es, Insigne Orden del Toisón de Oro, german: Orden vom Goldenen Vlies) is a Catholic order of chivalry founded in Bruges by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in 1430, to celebrate his marriage ...

, a forum of knights and nobles of which he was a member and later the grand master. The basis of Charles's beliefs was formed in this environment, including his Burgundian chivalric culture and the desire of Christian unity to fight the infidel in the tradition of medieval figures born in the Low Countries such as Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

and Godfrey of Bouillon

Godfrey of Bouillon (, , , ; 18 September 1060 – 18 July 1100) was a French nobleman and pre-eminent leader of the First Crusade. First ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from 1099 to 1100, he avoided the title of king, preferring that of princ ...

, whose biographies he often read.

Emperor Maximilian decided to emancipate his grandson in 1515 at the great hall of the Coudenberg

The Palace of Coudenberg (french: Palais du Coudenberg, nl, Coudenbergpaleis) was a royal residence situated on the Coudenberg or Koudenberg (; Dutch for "Cold Hill"), a small hill in what is today the Royal Quarter of Brussels, Belgium.

F ...

Palace in Brussels, where Charles would abdicate 40 years later. Once emancipated, he undertook his first voyage to tour the Burgundian provinces and made an acclaimed Joyous Entry

A Joyous Entry ( nl, Blijde Intrede, Blijde Inkomst, or ; ) is the official name used for the ceremonial royal entry, the first official peaceable visit of a reigning monarch, prince, duke or governor into a city, mainly in the Duchy of Braban ...

in Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest City status in Belgium, city of the Provinces of Belgium, province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium, in the northwest of the country, and the sixth-largest city of the countr ...

and other Flemish cities. Meanwhile, he refused to attend the coronation ceremony of the new king of France Francis I of Valois as a French vassal. This event marked the first episode of a long rivalry between the two monarchs.

Spanish kingdoms

In 1479, Spain was formed as adynastic union

A dynastic union is a type of union with only two different states that are governed under the same dynasty, with their boundaries, their laws, and their interests remaining distinct from each other.

Historical examples

Union of Kingdom of Arago ...

of two crowns by virtue of the marriage and joint rule of Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as List of Aragonese royal consorts, Queen consort ...

and Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

, the Trastámara Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being bot ...

. Upon the death of King Ferdinand II on 23 January 1516, his daughter Joanna the Mad, formally Queen of Castile

This is a list of kings and queens of the Kingdom of Castile, Kingdom and Crown of Castile. For their predecessors, see List of Castilian counts.

Kings and Queens of Castile

Jiménez dynasty

House of Ivrea

The following dynasts are de ...

since the death of Isabella in 1504 but effectively under her father's protection, became Queen of Aragon

This is a list of the kings and queens of Aragon. The Kingdom of Aragon was created sometime between 950 and 1035 when the County of Aragon, which had been acquired by the Kingdom of Navarre in the tenth century, was separated from Navarre in ...

as well. Ferdinand's testament recognized Joanna as sole Queen of the Spanish kingdoms with Charles as governor-general and cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros

Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, OFM (1436 – 8 November 1517), spelled Ximenes in his own lifetime, and commonly referred to today as simply Cisneros, was a Spanish cardinal, religious figure, and statesman. Starting from humble beginnings ...

as regent. Joanna's condition of insanity persisted and, as suggested by the Flemings and Maximilian, Charles claimed for himself the Spanish kingdoms ''jure matris

''Jure matris'' (''iure matris'') is a Latin phrase meaning "by right of his mother" or "in right of his mother".

It is commonly encountered in the law of inheritance when a noble title or other right passes from mother to son. It is also used in ...

''. After the celebration of Ferdinand II's obsequies on 14 March 1516, Charles was crowned King in the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula

nl, Kathedraal van Sint-Michiel en Sint-Goedele

, native_name_lang =

, image = Saints-Michel-et-Gudule Luc Viatour.jpg

, imagesize = 200px

, imagelink =

, imagealt =

, landscape ...

of Brussels as ''Charles I of Spain'' or ''Charles I of Castile and Aragon'', controlling both Spanish crowns in personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

.

Spanish kingdoms varied in their style and traditions. Castile was an increasingly authoritarian state where the monarch's own will easily overrode legislative and justice institutions. Its crown comprised most of Spain, including the Iberian

Spanish kingdoms varied in their style and traditions. Castile was an increasingly authoritarian state where the monarch's own will easily overrode legislative and justice institutions. Its crown comprised most of Spain, including the Iberian Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

conquered in 1512 and the former Islamic Kingdom of Granada

)

, common_languages = Official language:Classical ArabicOther languages: Andalusi Arabic, Mozarabic, Berber, Ladino

, capital = Granada

, religion = Majority religion:Sunni IslamMinority religions:Roman C ...

annexed at the end of the Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

in 1492. The crown of Aragon included the remaining Spanish kingdoms of Aragon proper, Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

, Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

, and Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, Valencia and the Municipalities of Spain, third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is ...

, and its monarchy was considered to be, differently from Castile and similarly to Navarre, the product of a contract with the people. Viceroyalties of the Spanish crowns formed the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

and included the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

and the Tierra Firme in the Americas, discovered by Cristopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

for Castile in 1492, as well as the Aragonese possessions in southern Italy: Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

, and the recently conquered (1503) Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

.

In August 1516, the ambassadors of Charles I of Spain and Francis I of France signed the ''Treaty of Noyon

Noyon (; pcd, Noéyon; la, Noviomagus Veromanduorum, Noviomagus of the Veromandui, then ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Oise Departments of France, department, northern France.

Geography

Noyon lies on the river Oise (river), Oise, a ...

'', which, along with the ''Treaty of Brussels'' signed between Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death. He was never crowned by the pope, as the journey to Rome was blocked by the Venetians. He proclaimed himself El ...

and the French king, ended the first phase of the Franco-Habsburg Italian Wars

The Italian Wars, also known as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a series of conflicts covering the period 1494 to 1559, fought mostly in the Italian peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and the Mediterranean Sea. The pr ...

, leaving the Imperial Duchy of Milan

The Duchy of Milan ( it, Ducato di Milano; lmo, Ducaa de Milan) was a state in northern Italy, created in 1395 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, then the lord of Milan, and a member of the important Visconti family, which had been ruling the city sin ...

in French hands and securing the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

under Spanish rule. In the same year, the Italian humanist Luigi Marliani coined Charles's personal motto "Plus Oultre

''Plus ultra'' (, , en, "Further beyond") is a List of Latin phrases (full), Latin phrase and the national motto of Spain. A reversal of the original phrase ''non plus ultra'' ("Nothing further beyond"), said to have been inscribed as a ...

" (later incorrectly Latinized in Plus Ultra

''Plus ultra'' (, , en, "Further beyond") is a Latin phrase and the national motto of Spain. A reversal of the original phrase ''non plus ultra'' ("Nothing further beyond"), said to have been inscribed as a warning on the Pillars of Herc ...

, which became the Spanish national motto), signifying "further beyond" and associated with the expansion of his inheritance as a reverse of the mythological ''Non Plus Ultra'' written on the Pillars of Hercules

The Pillars of Hercules ( la, Columnae Herculis, grc, Ἡράκλειαι Στῆλαι, , ar, أعمدة هرقل, Aʿmidat Hiraql, es, Columnas de Hércules) was the phrase that was applied in Antiquity to the promontories that flank t ...

. A year later, Charles I embarked for Spain, where his accession was contested and a succession crisis was unfolding, thus beginning his first voyage outside of the Low Countries and arriving in his new kingdoms in September 1517. Jiménez de Cisneros accepted the ''fait accompli'' and came to meet him but fell ill along the way, not without a suspicion of poison, and died before meeting the King. As regent, Cisneros was replaced by Charles's tutor Adrian of Utrecht

Pope Adrian VI ( la, Hadrianus VI; it, Adriano VI; nl, Adrianus/Adriaan VI), born Adriaan Florensz Boeyens (2 March 1459 – 14 September 1523), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 January 1522 until his d ...

, who was appointed Bishop of Tortosa

The bishop of Tortosa is the ordinary of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Tortosa in Catalonia, Spain.

and became himself a cardinal. Charles visited his mother in Tordesillas and, meeting for the first time his younger brother Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

, born in Castile and a popular candidate for the position of King, ordered him to abandon Spain. Charles then entered into negotiations with the ''Cortes'' of Castile and Aragon in order to be proclaimed king of the Spanish crowns jointly with his mother.

At his arrival in Spain, Charles was seen as a foreign prince of Flemish-Austrian background and his Burgundian-Habsburg entourage was accused to exploit the resources and offices of the Spanish kingdoms. For this reason, and due to the irregularities of Charles assuming the royal title while his mother was alive, the negotiations with the Castilian ''Cortes'' in Valladolid proved difficult. Eventually, the Cortes accepted Charles as king and paid homage to him in Valladolid in February 1518. Charles proceeded to Aragon and, once again, he managed to overcome the resistance of the Aragonese ''Cortes'' in order to be recognized as king. A year later, he was still negotiating with the Catalan ''Corts'' to be recognized as count of Barcelona and had not attended, despite requested, similar ceremonies in Valencia and Navarre, causing some grievances. By 1519, the ''Cortes'' of Castile and Aragon imposed the following conditions on Charles: he would learn to speak

At his arrival in Spain, Charles was seen as a foreign prince of Flemish-Austrian background and his Burgundian-Habsburg entourage was accused to exploit the resources and offices of the Spanish kingdoms. For this reason, and due to the irregularities of Charles assuming the royal title while his mother was alive, the negotiations with the Castilian ''Cortes'' in Valladolid proved difficult. Eventually, the Cortes accepted Charles as king and paid homage to him in Valladolid in February 1518. Charles proceeded to Aragon and, once again, he managed to overcome the resistance of the Aragonese ''Cortes'' in order to be recognized as king. A year later, he was still negotiating with the Catalan ''Corts'' to be recognized as count of Barcelona and had not attended, despite requested, similar ceremonies in Valencia and Navarre, causing some grievances. By 1519, the ''Cortes'' of Castile and Aragon imposed the following conditions on Charles: he would learn to speak Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

; he would cease to appoint foreigners for the high offices of Spain; he was prohibited from taking more than a fifth (Quinto Real

The ''quinto real'' or the quinto del rey, the "King's fifth", was a 20% tax established in 1504 that Spain levied on the mining of precious metals. The tax was a major source of revenue for the Spanish monarchy. In 1723 the tax was reduced to 10%. ...

) of precious metals

Precious metals are rare, naturally occurring metallic chemical elements of high economic value.

Chemically, the precious metals tend to be less reactive than most elements (see noble metal). They are usually ductile and have a high lustre. ...

coming from the Americas; and he would respect the rights of his mother, Queen and co-monarch Joanna

Joanna is a feminine given name deriving from from he, יוֹחָנָה, translit=Yôḥānāh, lit=God is gracious. Variants in English include Joan (given name), Joan, Joann, Joanne (given name), Joanne, and Johanna. Other forms of the name in ...

. In fact, Joanna made little effect on nation policies, as she was kept imprisoned till her death in 1555.

Austrian lands and Imperial election

Archduke of Austria

This is a list of people who have ruled either the Margraviate of Austria, the Duchy of Austria or the Archduchy of Austria. From 976 until 1246, the margraviate and its successor, the duchy, was ruled by the House of Babenberg. At that time, t ...

and head of the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

. As ''Charles I of Austria'', he inherited the Duchy of Austria

The Duchy of Austria (german: Herzogtum Österreich) was a medieval principality of the Holy Roman Empire, established in 1156 by the ''Privilegium Minus'', when the Margraviate of Austria (''Ostarrîchi'') was detached from Bavaria and elevated ...

, Styria

Styria (german: Steiermark ; Serbo-Croatian and sl, ; hu, Stájerország) is a state (''Bundesland'') in the southeast of Austria. With an area of , Styria is the second largest state of Austria, after Lower Austria. Styria is bordered to ...

, Tyrol

Tyrol (; historically the Tyrole; de-AT, Tirol ; it, Tirolo) is a historical region in the Alps - in Northern Italy and western Austria. The area was historically the core of the County of Tyrol, part of the Holy Roman Empire, Austrian Emp ...

, Further Austria

Further Austria, Outer Austria or Anterior Austria (german: Vorderösterreich, formerly ''die Vorlande'' (pl.)) was the collective name for the early (and later) possessions of the House of Habsburg in the former Swabian stem duchy of south-we ...

, Carinthia

Carinthia (german: Kärnten ; sl, Koroška ) is the southernmost States of Austria, Austrian state, in the Eastern Alps, and is noted for its mountains and lakes. The main language is German language, German. Its regional dialects belong to t ...

, Carniola

Carniola ( sl, Kranjska; , german: Krain; it, Carniola; hu, Krajna) is a historical region that comprised parts of present-day Slovenia. Although as a whole it does not exist anymore, Slovenes living within the former borders of the region sti ...

, and the Austrian Littoral

The Austrian Littoral (german: Österreichisches Küstenland, it, Litorale Austriaco, hr, Austrijsko primorje, sl, Avstrijsko primorje, hu, Osztrák Tengermellék) was a crown land (''Kronland'') of the Austrian Empire, established in 1849. ...

. As head of the House, he inherited the Imperial ideology exemplified by the dynastic motto A.E.I.O.U (''Austria Est Imperare Orbi Universo''—''Austria is to rule the universal world'') which seemed to materialize in the context of the now global Habsburg empire. To achieve a position of primacy in European affairs, Charles presented to the seven prince-electors (Palatinate, Saxony, Brandeburg, Mainz, Trier, Cologne, and Bohemia) his candidacy to rule the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, whose throne was occupied by the Habsburg Archdukes of Austria

This is a list of people who have ruled either the Margraviate of Austria, the Duchy of Austria or the Archduchy of Austria. From 976 until 1246, the margraviate and its successor, the duchy, was ruled by the House of Babenberg. At that time, t ...

since the mid-1400s.

The Holy Roman Empire was also known as Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unti ...

and its greatest constituent realm was the Kingdom of Germany

The Kingdom of Germany or German Kingdom ( la, regnum Teutonicorum "kingdom of the Germans", "German kingdom", "kingdom of Germany") was the mostly Germanic-speaking East Frankish kingdom, which was formed by the Treaty of Verdun in 843, especi ...

, divided into many princedoms, bishoprics, city-states, and other polities. The other large constituent kingdom was Imperial Italy, formed by several regional states to the north of the Papal States. Francis I of France

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once ...

, fearing that Charles's election would have resulted in the loss of French-held Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

and in the ''Habsburg Encirclement'' of his kingdom, attempted to secure the Imperial throne for himself through bribery. Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political an ...

, uneasy with the cumulation of power in Habsburg or French hands, invited various princes to enter the electoral race, hoping for the victory of a third candidate. Nonetheless, Leo X also signed secret alliances with both Charles and Francis in case one of them won the Imperial election, marking the first episode of Papal double-play in the French-Habsburg rivalry.

Charles borrowed large amounts of money from the Fugger

The House of Fugger () is a German upper bourgeois family that was historically a prominent group of European bankers, members of the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century mercantile patriciate of Augsburg, international mercantile bankers, and vent ...

s and the Welser

Welser was a Germans, German banking and merchant family, originally a patrician (post-Roman Europe), patrician family based in Augsburg and Nuremberg, that rose to great prominence in international high finance in the 16th century as bankers t ...

s, the two major German banking families, and surpassed Francis in the race to pay bigger bribes to the electors. He also signed with the German princes an electoral capitulation

An electoral capitulation (german: Wahlkapitulation) was initially a written agreement in parts of Europe, principally the Holy Roman Empire, whereby from the 13th century onward, a candidate to a Prince-Bishop, prince-bishopric had to agree to a s ...

(''Wahlkapitulation'') in which he promised to "protect and shield" Germany's liberties and began to learn German, Italian, and Latin. Finally, Charles advised the princes against electing a foreign king and declared himself a "''German by blood and stock''" on the ground that Austria, the home of his dynasty, and the Low Countries, where he was born, were then often considered part of Germany.

On 28 June 1519, Charles was elected

On 28 June 1519, Charles was elected Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

by the prince-electors reunited in Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

. A Papal dispensation, similar to one conferred to Maximilian in 1508, allowed him to use the Imperial title even in absence of Papal coronation. Informed of the election by Duke Frederick, Count Palatine, Charles proclaimed the Imperial title to be "''so great and sublime an honour to outshine all other worldly titles''" and thus became universally known by the Imperial name of ''Charles V''.

Imperial project and Reformation

Coronation in Aachen

The traditional ideology of theHoly Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

implied sovereignty over the entire Christian world. However, such a theoretical claim was never implemented in practice. The Italian statesman Mercurino di Gattinara

Mercurino Arborio, marchese di Gattinara (10 June 1465 – 5 June 1530), was an Italian statesman and jurist best known as the chancellor of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. He was made cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church for San Giovan ...

, a Piedmontese counselor of the Duchess of Savoy Margaret of Austria, known for his appreciation of Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: '' ...

's political treatise De Monarchia

''Monarchia'', often called ''De Monarchia'' (, ; "(On) Monarchy"), is a Latin treatise on secular and religious power by Dante Alighieri, who wrote it between 1312 and 1313. With this text, the poet intervened in one of the most controversial s ...

, reproposed the medieval idea and wrote to the Emperor:

Charles V endorsed the project and appointed Gattinara grand-chancellor of the Empire. Given that his dynastic fortunes gave him sovereignty in much of Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

and in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

, the Emperor believed it was his divine mission to transform the medieval dream into reality.

He left a tumultuous situation in Spain, where the revolt of the Comuneros

The Revolt of the Comuneros ( es, Guerra de las Comunidades de Castilla, "War of the Communities of Castile") was an uprising by citizens of Castile against the rule of Charles I and his administration between 1520 and 1521. At its height, th ...

in Castile and the revolt of the Brotherhoods

The Revolt of the Brotherhoods ( ca, Revolta de les Germanies, es, Rebelión de las Germanías) was a revolt by artisan guilds ('' Germanies'') against the government of King Charles V in the Kingdom of Valencia, part of the Crown of Aragon. ...

in Aragon outbroke among the lower classes to contest Habsburg rule, and returned to the Low Countries in 1520 via England. In two meetings with Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, first in Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour.

...

and then in Gravelines

Gravelines (, ; ; ) is a commune in the Nord department in Northern France. It lies at the mouth of the river Aa southwest of Dunkirk. It was formed in the 12th century around the mouth of a canal built to connect Saint-Omer with the sea. As ...

, he dissuaded the English king from joining an anti-Imperial alliance proposed by Francis I of France at the Field of the Cloth of Gold

The Field of the Cloth of Gold (french: Camp du Drap d'Or, ) was a summit meeting between King Henry VIII of England and King Francis I of France from 7 to 24 June 1520. Held at Balinghem, between Ardres in France and Guînes in the English P ...

. Following a festival held at his Palace of Coudenberg

The Palace of Coudenberg (french: Palais du Coudenberg, nl, Coudenbergpaleis) was a royal residence situated on the Coudenberg or Koudenberg (; Dutch for "Cold Hill"), a small hill in what is today the Royal Quarter of Brussels, Belgium.

F ...

in order to celebrate the election, Charles crossed the Rhine and arrived in Germany for the first time.

On 26 October 1520, Charles V was crowned

On 26 October 1520, Charles V was crowned King in Germany

This is a list of monarchs who ruled over East Francia, and the Kingdom of Germany (''Regnum Teutonicum''), from the division of the Frankish Empire in 843 and the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 until the collapse of the German Emp ...

at the Palatine Chapel of the Aachen Cathedral

Aachen Cathedral (german: Aachener Dom) is a Roman Catholic church in Aachen, Germany and the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Aachen.

One of the oldest cathedrals in Europe, it was constructed by order of Emperor Charlemagne, who was buri ...

and swore his oath as Holy Roman Emperor. Seated on the throne of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

while holding the Imperial regalia

The Imperial Regalia, also called Imperial Insignia (in German ''Reichskleinodien'', ''Reichsinsignien'' or ''Reichsschatz''), are regalia of the Holy Roman Emperor. The most important parts are the Crown, the Imperial orb, the Imperial sce ...

, namely the globus cruciger

The ''globus cruciger'' ( for, , Latin, cross-bearing orb), also known as "the orb and cross", is an orb surmounted by a cross. It has been a Christian symbol of authority since the Middle Ages, used on coins, in iconography, and with a sceptre ...

in his right hand and the Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippin ...

sceptre

A sceptre is a staff or wand held in the hand by a ruling monarch as an item of royal or imperial insignia. Figuratively, it means royal or imperial authority or sovereignty.

Antiquity

Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia

The ''Was'' and other ...

in his left, he promised to defend and expand the Empire, administer justice, observe the Roman Catholic faith, and become the protector of the Church (''Defensor Ecclesiae''). Later he called for the first general meeting of German princes of his era, to be held in January 1521 at the Imperial Diet of Worms

The Diet of Worms of 1521 (german: Reichstag zu Worms ) was an imperial diet (a formal deliberative assembly) of the Holy Roman Empire called by Emperor Charles V and conducted in the Imperial Free City of Worms. Martin Luther was summoned to t ...

.

"The empire on which the sun never sets"

While Charles V assumed the functions of Holy Roman Emperor in Germany, the ''conquistador''Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

informed him of the ongoing Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, also known as the Conquest of Mexico or the Spanish-Aztec War (1519–21), was one of the primary events in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. There are multiple 16th-century narratives of the eve ...

, including the discovery of Tenochtitlan

, ; es, Tenochtitlan also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, ; es, México-Tenochtitlan was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear. The date 13 March 1325 was ...

and the death of its ruler Montezuma during a local revolt, in a relation letter that widely circulated and became the basis of European knowledge on the Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire or the Triple Alliance ( nci, Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān, Help:IPA/Nahuatl, �jéːʃkaːn̥ t͡ɬaʔtoːˈlóːjaːn̥ was an alliance of three Nahua peoples, Nahua altepetl, city-states: , , and . These three city-states ruled ...

. Combined with the contemporary circumnavigation of the globe by Magellan and with the idea (proposed for the first time, although not realized) of constructing an American Isthmus canal in Panama, this success convinced the Emperor of his divine mission to unify the world as the leader of Christendom