HMS Temeraire (1798) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Temeraire'' was a 98-gun

''Temeraire'' was ordered from

''Temeraire'' was ordered from

The combined Franco-Spanish fleet left Cadiz and put to sea on 19 October 1805, and by 21 October was in sight of the British ships. Nelson formed up his lines and the British began to converge on their distant opponents. Contrary to his original instructions, Nelson took the lead of the weather column in ''Victory''. Concerned for the commander-in-chief's safety in such an exposed position,

The combined Franco-Spanish fleet left Cadiz and put to sea on 19 October 1805, and by 21 October was in sight of the British ships. Nelson formed up his lines and the British began to converge on their distant opponents. Contrary to his original instructions, Nelson took the lead of the weather column in ''Victory''. Concerned for the commander-in-chief's safety in such an exposed position,

''Temeraire'' then rammed into ''Redoutable'', dismounting many of the French ship's guns, and worked her way alongside, after which her crew lashed the two ships together. ''Temeraire'' now poured continuous broadsides into the French ship, taking fire as she did so from the 112-gun Spanish ship lying off her stern, and from the 74-gun French ship , which came up on ''Temeraire''s un-engaged starboard side. Harvey ordered his gun crews to hold fire until ''Fougueux'' came within point blank range. ''Temeraire''s first broadside against ''Fougueux'' at a range of caused considerable damage to the Frenchman's rigging, and she drifted into ''Temeraire'', whose crew promptly lashed her to the side. ''Temeraire'' was now lying between two French 74-gun ships. As Harvey later recalled in a letter to his wife "Perhaps never was a ship so circumstanced as mine, to have for more than three hours two of the enemy's line of battle ships lashed to her." ''Redoutable'', sandwiched between ''Victory'' and ''Temeraire'', suffered heavy casualties, reported by Captain Lucas as amounting to 300 dead and 222 wounded. During the fight grenades thrown from the decks and topmasts of ''Redoutable'' killed and wounded a number of ''Temeraire''s crew and set her starboard rigging and foresail on fire. There was a brief pause in the fighting while both sides worked to douse the flames. ''Temeraire'' narrowly escaped destruction when a grenade thrown from ''Redoutable'' exploded on her maindeck, nearly igniting the after-magazine. Master-At-Arms John Toohig prevented the fire from spreading and saved not only ''Temeraire'', but the surrounding ships, which would have been caught in the explosion.

After twenty minutes' fighting both ''Victory'' and ''Temeraire'', ''Redoutable'' had been reduced to a floating wreck. ''Temeraire'' had also suffered heavily, damaged when ''Redoutable''s main mast fell onto her

''Temeraire'' then rammed into ''Redoutable'', dismounting many of the French ship's guns, and worked her way alongside, after which her crew lashed the two ships together. ''Temeraire'' now poured continuous broadsides into the French ship, taking fire as she did so from the 112-gun Spanish ship lying off her stern, and from the 74-gun French ship , which came up on ''Temeraire''s un-engaged starboard side. Harvey ordered his gun crews to hold fire until ''Fougueux'' came within point blank range. ''Temeraire''s first broadside against ''Fougueux'' at a range of caused considerable damage to the Frenchman's rigging, and she drifted into ''Temeraire'', whose crew promptly lashed her to the side. ''Temeraire'' was now lying between two French 74-gun ships. As Harvey later recalled in a letter to his wife "Perhaps never was a ship so circumstanced as mine, to have for more than three hours two of the enemy's line of battle ships lashed to her." ''Redoutable'', sandwiched between ''Victory'' and ''Temeraire'', suffered heavy casualties, reported by Captain Lucas as amounting to 300 dead and 222 wounded. During the fight grenades thrown from the decks and topmasts of ''Redoutable'' killed and wounded a number of ''Temeraire''s crew and set her starboard rigging and foresail on fire. There was a brief pause in the fighting while both sides worked to douse the flames. ''Temeraire'' narrowly escaped destruction when a grenade thrown from ''Redoutable'' exploded on her maindeck, nearly igniting the after-magazine. Master-At-Arms John Toohig prevented the fire from spreading and saved not only ''Temeraire'', but the surrounding ships, which would have been caught in the explosion.

After twenty minutes' fighting both ''Victory'' and ''Temeraire'', ''Redoutable'' had been reduced to a floating wreck. ''Temeraire'' had also suffered heavily, damaged when ''Redoutable''s main mast fell onto her

A number of artists visited the newly returned Trafalgar ships, including John Livesay, drawing master at the

A number of artists visited the newly returned Trafalgar ships, including John Livesay, drawing master at the

The tugs took the

The tugs took the

second-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a second-rate was a ship of the line which by the start of the 18th century mounted 90 to 98 guns on three gun decks; earlier 17th-century second rates had fewer guns ...

ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

's Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

. Launched in 1798, she served during the French Revolutionary

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are consider ...

and Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, mostly on blockades or convoy escort duties. She fought only one fleet action, the Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (180 ...

, but became so well known for that action and her subsequent depictions in art and literature that she has been remembered as ''The Fighting Temeraire''.

Built at Chatham Dockyard

Chatham Dockyard was a Royal Navy Dockyard located on the River Medway in Kent. Established in Chatham in the mid-16th century, the dockyard subsequently expanded into neighbouring Gillingham (at its most extensive, in the early 20th century, ...

, ''Temeraire'' entered naval service on the Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

blockade with the Channel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history the ...

. Missions were tedious and seldom relieved by any action with the French fleet. The first incident of note came when several of her crew, hearing rumours they were to be sent to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

at a time when peace with France seemed imminent, refused to obey orders. This act of mutiny eventually failed and a number of those responsible were tried and executed. Laid up

A reserve fleet is a collection of naval vessels of all types that are fully equipped for service but are not currently needed; they are partially or fully decommissioned. A reserve fleet is informally said to be "in mothballs" or "mothballed"; a ...

during the Peace of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it se ...

, ''Temeraire'' returned to active service with the resumption of the wars with France, again serving with the Channel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history the ...

, and joined Horatio Nelson's blockade of the Franco-Spanish fleet in Cadiz in 1805. At the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October, the ship went into action immediately astern of Nelson's flagship, . During the battle ''Temeraire'' came to the rescue of the beleaguered ''Victory'', and fought and captured two French ships, winning public renown in Britain.

After undergoing substantial repairs, ''Temeraire'' was employed blockading the French fleets and supporting British operations off the Spanish coasts. She went out to the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

in 1809, defending convoys against Danish gunboat attacks, and by 1810 was off the Spanish coast again, helping to defend Cadiz against a French army. Her last action was against the French off Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

, when she came under fire from shore batteries. The ship returned to Britain in 1813 for repairs, but was laid up. She was converted to a prison ship and moored in the River Tamar

The Tamar (; kw, Dowr Tamar) is a river in south west England, that forms most of the border between Devon (to the east) and Cornwall (to the west). A part of the Tamar Valley is a World Heritage Site due to its historic mining activities.

T ...

until 1819. Further service brought her to Sheerness

Sheerness () is a town and civil parish beside the mouth of the River Medway on the north-west corner of the Isle of Sheppey in north Kent, England. With a population of 11,938, it is the second largest town on the island after the nearby town ...

as a receiving ship

A hulk is a ship that is afloat, but incapable of going to sea. Hulk may be used to describe a ship that has been launched but not completed, an abandoned wreck or shell, or to refer to an old ship that has had its rigging or internal equipmen ...

, then a victualling depot, and finally a guard ship

A guard ship is a warship assigned as a stationary guard in a port or harbour, as opposed to a coastal patrol boat, which serves its protective role at sea.

Royal Navy

In the Royal Navy of the eighteenth century, peacetime guard ships were usual ...

. The Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

ordered her to be sold in 1838, and she was towed up the Thames to be broken up.

This final voyage was depicted in a J. M. W. Turner oil painting greeted with critical acclaim, entitled '' The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last Berth to be broken up, 1838''. The painting continues to be held in high regard: it was voted Britain's favourite painting in a BBC radio poll in 2005 and it appears briefly in the James Bond

The ''James Bond'' series focuses on a fictional British Secret Service agent created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels and two short-story collections. Since Fleming's death in 1964, eight other authors have ...

movie ''Skyfall

''Skyfall'' is a 2012 spy film and the twenty-third in the ''James Bond'' series produced by Eon Productions. The film is the third to star Daniel Craig as fictional MI6 agent James Bond and features Javier Bardem as Raoul Silva, the villai ...

''. A reproduction of the painting appears on the back of the Bank of England £20 note

The Bank of England £20 note is a sterling banknote. It is the second-highest denomination of banknote currently issued by the Bank of England. The current polymer note, first issued on 20 February 2020, bears the image of Queen Elizabeth II ...

issued in 2020.

Construction and commissioning

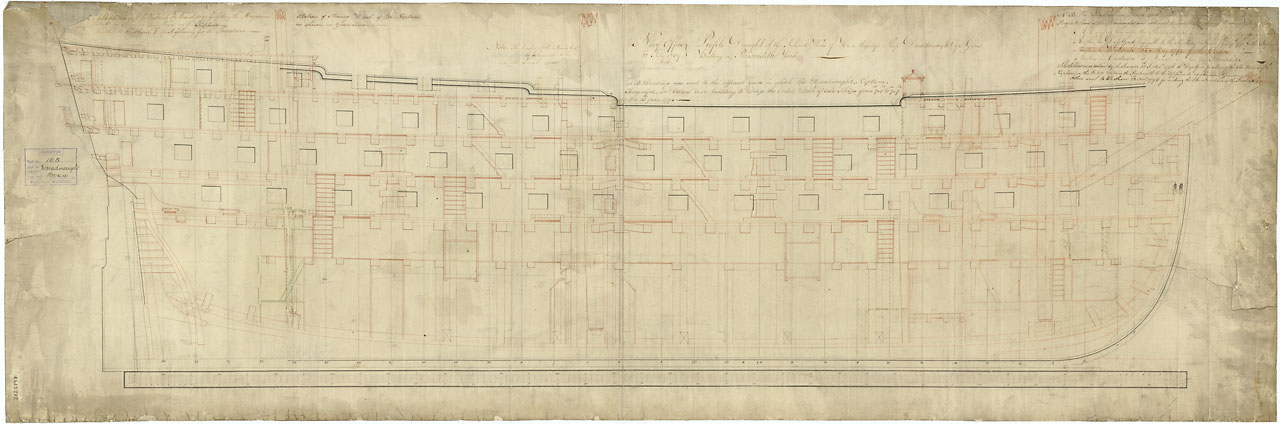

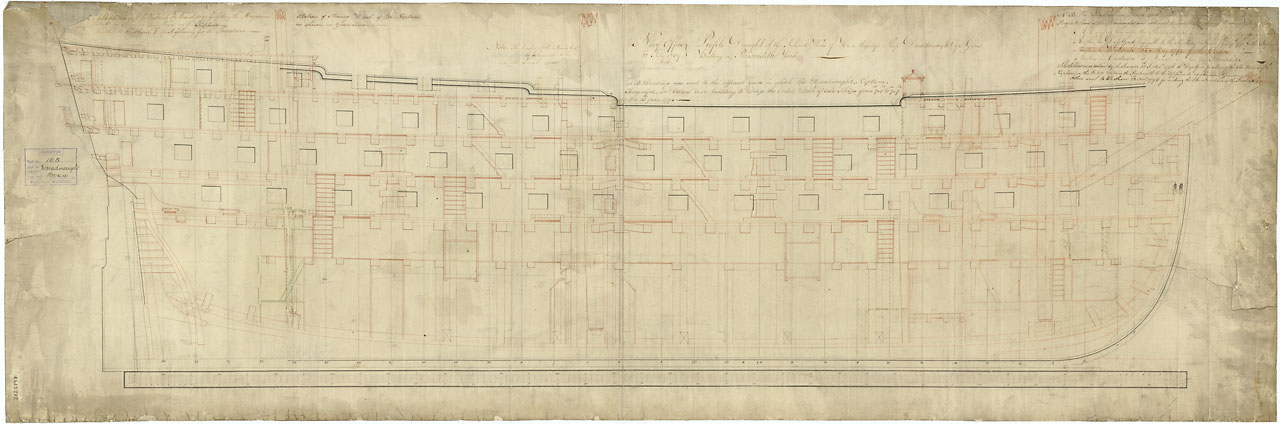

''Temeraire'' was ordered from

''Temeraire'' was ordered from Chatham Dockyard

Chatham Dockyard was a Royal Navy Dockyard located on the River Medway in Kent. Established in Chatham in the mid-16th century, the dockyard subsequently expanded into neighbouring Gillingham (at its most extensive, in the early 20th century, ...

on 9 December 1790, to a design developed by Surveyor of the Navy

The Surveyor of the Navy also known as Department of the Surveyor of the Navy and originally known as Surveyor and Rigger of the Navy was a former principal commissioner and member of both the Navy Board from the inauguration of that body in 15 ...

Sir John Henslow

Sir John Henslow (9 October 1730 – 22 September 1815) was Surveyor to the Navy (Royal Navy) a post he held jointly or solely from 1784 to 1806.

Career

He was 7th child of John Henslow a master carpenter in the dockyard at Woolwich

. She was one of three ships of the , alongside her sisters and .

She was primarily made from English oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' (; Latin "oak tree") of the beech family, Fagaceae. There are approximately 500 extant species of oaks. The common name "oak" also appears in the names of species in related genera, notably ''L ...

from nearby Hainault Forest

Hainault Forest Country Park is a Country Park located in Greater London, with portions in: Hainault in the London Borough of Redbridge; the London Borough of Havering; and in the Lambourne parish of the Epping Forest District in Essex.

Geograp ...

. The keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

was laid down at Chatham in July 1793. Her construction was initially overseen by Master Shipwright Thomas Pollard and completed by his successor Edward Sison. ''Temeraire'' was launched in the rain on Tuesday 11 September 1798 and the following day was taken into the graving dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

to be fitted for sea. Her hull was fitted with copper sheathing

Copper sheathing is the practice of protecting the under-water hull of a ship or boat from the corrosive effects of salt water and biofouling through the use of copper plates affixed to the outside of the hull. It was pioneered and developed by ...

, a process that took two weeks to complete. Refloated, she finished fitting out, and received her masts and yards. Her final costs came to £73,241, and included £59,428 spent on the hull, masts and yards, and a further £13,813 on rigging and stores.

She was commissioned on 21 March 1799 under Captain Peter Puget

Peter Puget (1765 – 31 October 1822) was an officer in the Royal Navy, best known for his exploration of Puget Sound.

Midshipman Puget

Puget's ancestors had fled France for Britain during Louis XIV's persecution of the Huguenots. His father, ...

, becoming the second ship of the Royal Navy to bear the name ''Temeraire''. Her predecessor had been the 74-gun third-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the third r ...

, a former French ship taken as a prize

A prize is an award to be given to a person or a group of people (such as sporting teams and organizations) to recognize and reward their actions and achievements.

at the Battle of Lagos

The naval Battle of Lagos took place between a British fleet commanded by Sir Edward Boscawen and a French fleet under Jean-François de La Clue-Sabran over two days in 1759 during the Seven Years' War. They fought south west of the Gulf of C� ...

on 19 August 1759 by a fleet under Admiral Edward Boscawen

Admiral of the Blue Edward Boscawen, PC (19 August 171110 January 1761) was a British admiral in the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament for the borough of Truro, Cornwall, England. He is known principally for his various naval commands during ...

. Puget was in command only until 26 July 1799, during which time he oversaw the process of fitting the new ''Temeraire'' for sea. He was superseded by Captain Thomas Eyles on 27 July 1799, while the vessel was anchored off St Helens, Isle of Wight

St Helens is a village and civil parish located on the eastern side of the Isle of Wight.

The village developed around village greens. This is claimed to be the largest in England but some say it is the second largest. The greens are often us ...

.

With the Channel Fleet

Under Eyles's command ''Temeraire'' finally put to sea at the end of July,flying the flag

''Flying the Flag'' was a BBC radio sitcom set in a British embassy in the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War. It ran for four series, aired from 1987 to 1992, which have been repeated numerous times.

Synopsis

Created during the Cold War, thi ...

of Rear Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren

Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren, 1st Baronet (2 September 1753 – 27 February 1822) was a British Royal Navy officer, diplomat and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1774 and 1807.

Naval career

Born in Stapleford, Nottinghamsh ...

, and joined the Channel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history the ...

under the overall command of Admiral Lord Bridport. The Channel Fleet was at that time principally engaged in the blockade of the French port of Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

, and ''Temeraire'' spent several long cruises of two or three months at a time patrolling the area. Eyles was superseded during this period by ''Temeraire''s former commander, Captain Puget, who resumed command on 14 October 1799, and the following month ''Temeraire'' became the flagship of Rear Admiral James Whitshed.

Lord Bridport had been replaced as commander of the Channel Fleet by Admiral Lord St Vincent in mid-1799, and the long blockade cruises were sustained throughout the winter and into the following year. On 20 April 1800 Puget was superseded as commander by Captain Edward Marsh. Marsh commanded ''Temeraire'' through the remainder of that year and for the first half of 1801, until his replacement, Captain Thomas Eyles, arrived to resume command on 31 August. Rear Admiral Whitshed had also struck his flag by now, and ''Temeraire'' became the flagship of Rear Admiral George Campbell. By this time the Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on periodisation) was the second war on revolutionary France by most of the European monarchies, led by Britain, Austria and Russia, and including the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, N ...

against France had collapsed, and negotiations for peace were underway at Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

. Lord St Vincent had been promoted to First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

, and command of the Channel Fleet passed to Admiral Sir William Cornwallis. With the end of the war imminent, ''Temeraire'' was taken off blockade duty and sent to Bantry Bay

Bantry Bay ( ga, Cuan Baoi / Inbhear na mBárc / Bádh Bheanntraighe) is a bay located in County Cork, Ireland. The bay runs approximately from northeast to southwest into the Atlantic Ocean. It is approximately 3-to-4 km (1.8-to-2.5 mi ...

to await the arrival of a convoy, which she would then escort to the West Indies. Many of the crew had been serving continuously in the navy since the start of the French Revolutionary Wars in 1793, and had looked forward to returning to England now that peace seemed imminent. On hearing rumours that instead they were to be sent to the West Indies, around a dozen men began to agitate for the rest of the crew to refuse orders to sail for anywhere but England.

Mutiny

On the morning of 3 December, a small group of sailors gathered on theforecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is the phrase " be ...

and, refusing orders to leave, began to argue with the officers. Captain Eyles asked to know their demands, which were an assurance that ''Temeraire'' would not go to the West Indies, but instead would return to England. Eventually Rear Admiral Campbell came down to speak to the men, and having informed them that the officers did not know the destination of the ship, he ordered them to disperse. The men went below decks and the incipient mutiny appeared to have been quashed. The ringleaders, numbering around a dozen, remained determined however, and made discreet inquiries among the rest of the crew. Having eventually determined that the majority of the crew would, if not actually support a mutiny, at least not oppose it, and that ''Temeraire''s crew would be supported by the ship's marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

as well as the crews of some of the other warships in Bantry Bay, they decided to press ahead with their plans. The mutiny began with the crew closing the ship's gunport

A gunport is an opening in the side of the hull of a ship, above the waterline, which allows the muzzle of artillery pieces mounted on the gun deck to fire outside. The origin of this technology is not precisely known, but can be traced back to ...

s, effectively barricading themselves below deck. Having done so, they refused orders to open them again, jeered the officers and threatened violence. The crew then came up on deck and once again demanded to know their destination and refused to obey orders to sail for anywhere but England. Having presented their demands they returned below decks and resumed the usual shipboard routine as much as they could.

Alarmed by the actions of ''Temeraire''s crew, Campbell met with Vice-Admiral Sir Andrew Mitchell the following day and informed him of the mutineers' demands. Mitchell reported the news to the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

while Campbell returned to ''Temeraire'' and summoned the crew on deck once more. He urged them to return to duty, and then dismissed them. Meanwhile, discipline had begun to break down among the mutineers. Several of the crew became drunk, and some of the officers were struck by rowdy seamen. When one of the marines who supported the mutiny was placed in irons for drunken behaviour and insolence, a crowd formed on deck and tried to free him. The officers resisted these attempts and as sailors began to push and threaten them, Campbell gave the order for the marines to arrest those he identified as the ringleaders. The marines hesitated, but then obeyed the order, driving the unruly seamen back and arresting a number of them, who were immediately placed in irons. Campbell ordered the remaining crew to abandon any mutinous actions, and deprived of its leaders, the mutiny collapsed, though the officers were on their guard for several days afterwards and the marines were ordered to carry out continuous patrols.

News of the mutiny created a sensation in England, and the Admiralty ordered ''Temeraire'' to sail immediately for Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

while an investigation was carried out. Vice-Admiral Mitchell was granted extraordinary powers regarding the death sentence

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

and ''Temeraire''s complement of marines was hastily augmented for the voyage to England. On the ship's arrival, the 14 imprisoned ringleaders were swiftly court-martialled in Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

aboard , some on 6 January 1802 and the rest on 14 January. After deliberations, twelve were sentenced to be hanged at the yardarm

A yard is a spar on a mast from which sails are set. It may be constructed of timber or steel or from more modern materials such as aluminium or carbon fibre. Although some types of fore and aft rigs have yards, the term is usually used to desc ...

, and the remaining two were to receive two hundred lashes each. Four men were duly hanged aboard ''Temeraire'', and the remainder were hanged aboard several of the ships anchored at Portsmouth, including , , and . A further seven men involved were sent to prison hulk

A prison ship, often more accurately described as a prison hulk, is a current or former seagoing vessel that has been modified to become a place of substantive detention for convicts, prisoners of war or civilian internees. While many natio ...

s for life.

West Indies and the peace

After the executions, ''Temeraire'' was immediately sent to sea, sailing from Portsmouth for theIsle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

the day after and beginning preparations for her delayed voyage to the West Indies. She sailed for Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

, arriving there on 24 February, and remained in the West Indies until the summer. During her time there the Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on perio ...

was finally signed and ratified, and ''Temeraire'' was ordered back to Britain. She arrived at Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

on 28 September and Eyles paid her off on 5 October. Because of the drawdown in the size of the active navy as a result of the peace, ''Temeraire'' was laid up

A reserve fleet is a collection of naval vessels of all types that are fully equipped for service but are not currently needed; they are partially or fully decommissioned. A reserve fleet is informally said to be "in mothballs" or "mothballed"; a ...

in the Hamoaze

The Hamoaze (; ) is an estuarine stretch of the tidal River Tamar, between its confluence with the River Lynher and Plymouth Sound, England.

The name first appears as ''ryver of Hamose'' in 1588 and it originally most likely applied just to a ...

for the next eighteen months.

Return to service

The peace of Amiens was a brief interlude in the wars with Revolutionary France, and in 1803 theWar of the Third Coalition

The War of the Third Coalition)

* In French historiography, it is known as the Austrian campaign of 1805 (french: Campagne d'Autriche de 1805) or the German campaign of 1805 (french: Campagne d'Allemagne de 1805) was a European conflict spanni ...

began. ''Temeraire'' had deteriorated substantially during her long period spent laid up, and she was taken into dry dock on 22 May to repair and refit, starting with the replacement of her copper sheathing. Work was delayed when a heavy storm hit Plymouth in January 1804, causing appreciable damage to ''Temeraire'', but was finally completed by February 1804, at a cost of £16,898.

Command was assigned to Captain Eliab Harvey

Admiral Sir Eliab Harvey (5 December 1758 – 20 February 1830) was an eccentric and hot-tempered officer of the Royal Navy during the French Revolutionary and the Napoleonic Wars who was as distinguished for his gambling and dueling as fo ...

, and he arrived to take up his commission on 1 January 1804. The crew were largely from Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

. They left Cawsand Bay

Cawsand Bay is a bay on the southeast coast of Cornwall, England, United Kingdom.

The bay takes its name from the village of Cawsand at , to the northeast of the Rame Peninsula. Cawsand Bay is oriented north–south, opening eastward into Pl ...

on 11 March 1804, sailing to join the Channel Fleet off Brest, still under the overall command of Admiral Cornwallis.

As a much forgotten part of history, Napoleon had assembled his Grand Army, 160,000 men, near Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the ...

as part of a plan to invade England. The bulk of the French navy: 21 ships of the line, were harboured at Brest but were needed for the invasion plan.

''Temeraire'' now resumed her previous duties blockading the French at Brest, patrolling between Ushant

Ushant (; br, Eusa, ; french: Ouessant, ) is a French island at the southwestern end of the English Channel which marks the westernmost point of metropolitan France. It belongs to Brittany and, in medieval terms, Léon. In lower tiers of governm ...

Island and Cape Finisterre

Cape Finisterre (, also ; gl, Cabo Fisterra, italic=no ; es, Cabo Finisterre, italic=no ) is a rock-bound peninsula on the west coast of Galicia, Spain.

In Roman times it was believed to be an end of the known world. The name Finisterre, like ...

. Heavy weather took its toll, forcing her to put into Torbay

Torbay is a borough and unitary authority in Devon, south west England. It is governed by Torbay Council and consists of of land, including the resort towns of Torquay, Paignton and Brixham, located on east-facing Tor Bay, part of Lyme ...

for extensive repairs after her long patrols, repairs which eventually amounted to £9,143. During this time Harvey was often absent from his command, usually attending to his duties as Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

for Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

. He was temporarily replaced by Captain William Kelly on 27 August 1804, and he in turn was succeeded by Captain George Fawke on 6 April 1805. Harvey returned to his ship on 9 July 1805, and it was while he was in command that the reinforced Rochefort

Rochefort () may refer to:

Places France

* Rochefort, Charente-Maritime, in the Charente-Maritime department

** Arsenal de Rochefort, a former naval base and dockyard

* Rochefort, Savoie in the Savoie department

* Rochefort-du-Gard, in the Ga ...

squadron under Vice-Admiral Sir Robert Calder intercepted and attacked a Franco-Spanish fleet at the Battle of Cape Finisterre. The French commander, Pierre-Charles Villeneuve

Pierre-Charles-Jean-Baptiste-Silvestre de Villeneuve (31 December 1763 – 22 April 1806) was a French naval officer during the Napoleonic Wars. He was in command of the French and the Spanish fleets that were defeated by Nelson at the Bat ...

, was thwarted in his attempt to join the French forces at Brest, and instead sailed south to Ferrol, and then to Cadiz. When news of the Franco-Spanish fleet's location reached the Admiralty, they appointed Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

to take command of the blockading force at Cadiz, which at the time was being commanded by Vice-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood

Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, 1st Baron Collingwood (26 September 1748 – 7 March 1810) was an admiral of the Royal Navy, notable as a partner with Lord Nelson in several of the British victories of the Napoleonic Wars, and frequently as ...

. Nelson was told to pick whichever ships he liked to serve under him, and one of those he specifically chose was ''Temeraire''.

Collingwood replaced Calder on the Temeraire in August 1804.

The ship sheltered with the Channel Fleet at Douarnenez Bay during the storms of November 1804. Further winter storms caused her to go to Torbay for repairs in January 1805 and she did not return to the squadron at Brest until April.

Command returned to Calder again on 16 August 1805 and headed for Ferrol to intercept Admiral Vileneuve and the French fleet. The French unexpectedly turned south and the British fleet followed them down to Cadiz.

Battle of Trafalgar

''Temeraire'' duly received orders to join the Cadiz blockade, and having sailed to rendezvous with Collingwood, Harvey awaited Nelson's arrival. Nelson's flagship, the 100-gun , arrived off Cadiz on 28 September, and he took over command of the fleet from Collingwood. He spent the next few weeks forming his plan of attack in preparation for the expected sortie of the Franco-Spanish fleet, issuing it to his captains on 9 October in the form of a memorandum. The memorandum called for two divisions of ships to attack at right angles to the enemy line, severing its van from the centre and rear. A third advance squadron would be deployed as a reserve, with the ability to join one of the lines as the course of the battle dictated. Nelson placed the largest and most powerful ships at the heads of the lines, with ''Temeraire'' assigned to lead Nelson's own column into battle. The fleet patrolled a considerable distance from the Spanish coast to lure the combined fleet out, and the ships took the opportunity to exercise and prepare for the coming battle. For ''Temeraire'' this probably involved painting her sides in theNelson Chequer

The Nelson Chequer was a colour scheme adopted by vessels of the Royal Navy, modelled on that used by Admiral Horatio Nelson in battle. It consisted of bands of black and yellow paint along the sides of the hull, broken up by black gunports.

...

design, to enable the British ships to tell friend from foe in the confusion of battle.

The combined Franco-Spanish fleet left Cadiz and put to sea on 19 October 1805, and by 21 October was in sight of the British ships. Nelson formed up his lines and the British began to converge on their distant opponents. Contrary to his original instructions, Nelson took the lead of the weather column in ''Victory''. Concerned for the commander-in-chief's safety in such an exposed position,

The combined Franco-Spanish fleet left Cadiz and put to sea on 19 October 1805, and by 21 October was in sight of the British ships. Nelson formed up his lines and the British began to converge on their distant opponents. Contrary to his original instructions, Nelson took the lead of the weather column in ''Victory''. Concerned for the commander-in-chief's safety in such an exposed position, Henry Blackwood

Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Blackwood, 1st Baronet, GCH, KCB (28 December 1770 – 17 December 1832), whose memorial is in Killyleagh Parish Church, was a British sailor.

Early life

Blackwood was the fourth son of Sir John Blackwood, 2nd Baronet, ...

, a long-standing friend of Nelson and commander of the frigate that day, suggested Nelson come aboard his ship to better observe and direct the battle. Nelson refused, so Blackwood instead tried to convince him to let Harvey come past him in the ''Temeraire'', and so lead the column into battle. Nelson agreed to this, and signalled for Harvey to come past him. As ''Temeraire'' drew up towards ''Victory'', Nelson decided that if he was standing aside to let another ship lead his line, so too should Collingwood, commanding the lee column of ships. He signalled Collingwood, aboard his flagship , to let another ship come ahead of him, but Collingwood continued to surge ahead. Reconsidering his plan, Nelson is reported to have hailed ''Temeraire'', as she came up alongside ''Victory'', with the words "I'll thank you, Captain Harvey, to keep in your proper station, which is ''astern'' of the Victory." Nelson's instruction was followed up by a formal signal and Harvey dropped back reluctantly, but otherwise kept within one ship's length of ''Victory'' as she sailed up to the Franco-Spanish line.

Closely following ''Victory'' as she passed through the Franco-Spanish line across the bows of the French flagship , Harvey was forced to sheer away quickly, just missing ''Victory''s stern. Turning to starboard, Harvey made for the 140-gun Spanish ship ''Santísima Trinidad'' and engaged her for twenty minutes, taking raking fire

In naval warfare during the Age of Sail, raking fire was cannon fire directed parallel to the long axis of an enemy ship from ahead (in front of the ship) or astern (behind the ship). Although each shot was directed against a smaller profile ...

from two French ships, the 80-gun and the 74-gun , as she did so. ''Redoutable''s broadside carried away ''Temeraire''s mizzen

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the centre-line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, and giving necessary height to a navigation ligh ...

topmast. While avoiding a broadside from ''Neptune'', ''Temeraire'' narrowly avoided a collision with ''Redoutable''. Another broadside from ''Neptune'' brought down ''Temeraire''s fore-yard and main topmast, and damaged her fore mast and bowsprit

The bowsprit of a sailing vessel is a spar extending forward from the vessel's prow. The bowsprit is typically held down by a bobstay that counteracts the forces from the forestays. The word ''bowsprit'' is thought to originate from the Middle L ...

. Harvey now became aware that ''Redoutable'' had come up alongside ''Victory'' and swept her decks with musket fire and grenades. A large party of Frenchmen now gathered on her decks ready to board ''Victory''. ''Temeraire'' was brought around; appearing suddenly out of the smoke of the battle and slipping across ''Redoutable''s stern, ''Temeraire'' discharged a double-shotted

Naval artillery is artillery mounted on a warship, originally used only for naval warfare and then subsequently used for naval gunfire support, shore bombardment and anti-aircraft roles. The term generally refers to tube-launched projectile-firi ...

broadside into her. Jean Jacques Étienne Lucas, captain of ''Redoutable'', recorded that "... the three-decker 'Temeraire''ho had doubtless perceived that the ''Victory'' had ceased fire and would inevitably be takenran foul of the ''Redoutable'' to starboard and overwhelmed us with the point-blank fire of all her guns. It would be impossible to describe the horrible carnage produced by the murderous broadside of this ship. More than two hundred of our brave lads were killed or wounded by it."

''Temeraire'' and ''Redoutable''

''Temeraire'' then rammed into ''Redoutable'', dismounting many of the French ship's guns, and worked her way alongside, after which her crew lashed the two ships together. ''Temeraire'' now poured continuous broadsides into the French ship, taking fire as she did so from the 112-gun Spanish ship lying off her stern, and from the 74-gun French ship , which came up on ''Temeraire''s un-engaged starboard side. Harvey ordered his gun crews to hold fire until ''Fougueux'' came within point blank range. ''Temeraire''s first broadside against ''Fougueux'' at a range of caused considerable damage to the Frenchman's rigging, and she drifted into ''Temeraire'', whose crew promptly lashed her to the side. ''Temeraire'' was now lying between two French 74-gun ships. As Harvey later recalled in a letter to his wife "Perhaps never was a ship so circumstanced as mine, to have for more than three hours two of the enemy's line of battle ships lashed to her." ''Redoutable'', sandwiched between ''Victory'' and ''Temeraire'', suffered heavy casualties, reported by Captain Lucas as amounting to 300 dead and 222 wounded. During the fight grenades thrown from the decks and topmasts of ''Redoutable'' killed and wounded a number of ''Temeraire''s crew and set her starboard rigging and foresail on fire. There was a brief pause in the fighting while both sides worked to douse the flames. ''Temeraire'' narrowly escaped destruction when a grenade thrown from ''Redoutable'' exploded on her maindeck, nearly igniting the after-magazine. Master-At-Arms John Toohig prevented the fire from spreading and saved not only ''Temeraire'', but the surrounding ships, which would have been caught in the explosion.

After twenty minutes' fighting both ''Victory'' and ''Temeraire'', ''Redoutable'' had been reduced to a floating wreck. ''Temeraire'' had also suffered heavily, damaged when ''Redoutable''s main mast fell onto her

''Temeraire'' then rammed into ''Redoutable'', dismounting many of the French ship's guns, and worked her way alongside, after which her crew lashed the two ships together. ''Temeraire'' now poured continuous broadsides into the French ship, taking fire as she did so from the 112-gun Spanish ship lying off her stern, and from the 74-gun French ship , which came up on ''Temeraire''s un-engaged starboard side. Harvey ordered his gun crews to hold fire until ''Fougueux'' came within point blank range. ''Temeraire''s first broadside against ''Fougueux'' at a range of caused considerable damage to the Frenchman's rigging, and she drifted into ''Temeraire'', whose crew promptly lashed her to the side. ''Temeraire'' was now lying between two French 74-gun ships. As Harvey later recalled in a letter to his wife "Perhaps never was a ship so circumstanced as mine, to have for more than three hours two of the enemy's line of battle ships lashed to her." ''Redoutable'', sandwiched between ''Victory'' and ''Temeraire'', suffered heavy casualties, reported by Captain Lucas as amounting to 300 dead and 222 wounded. During the fight grenades thrown from the decks and topmasts of ''Redoutable'' killed and wounded a number of ''Temeraire''s crew and set her starboard rigging and foresail on fire. There was a brief pause in the fighting while both sides worked to douse the flames. ''Temeraire'' narrowly escaped destruction when a grenade thrown from ''Redoutable'' exploded on her maindeck, nearly igniting the after-magazine. Master-At-Arms John Toohig prevented the fire from spreading and saved not only ''Temeraire'', but the surrounding ships, which would have been caught in the explosion.

After twenty minutes' fighting both ''Victory'' and ''Temeraire'', ''Redoutable'' had been reduced to a floating wreck. ''Temeraire'' had also suffered heavily, damaged when ''Redoutable''s main mast fell onto her poop deck

In naval architecture, a poop deck is a deck that forms the roof of a cabin built in the rear, or " aft", part of the superstructure of a ship.

The name originates from the French word for stern, ''la poupe'', from Latin ''puppis''. Thus th ...

, and having had her own topmasts shot away. Informed that his ship was in danger of sinking, Lucas finally called for quarter to ''Temeraire''. Harvey sent a party across under the second lieutenant, John Wallace, to take charge of the ship.

''Temeraire'' and ''Fougueux''

Lashed together, ''Temeraire'' and ''Fougueux'' exchanged fire, ''Temeraire'' initially clearing the French ship's upper deck with small arms fire. The French rallied, but the greater height of the three-decked ''Temeraire'' compared to the two-decked ''Fougueux'' thwarted their attempts to board. Instead Harvey dispatched his own boarding party, led by First-LieutenantThomas Fortescue Kennedy

Thomas Fortescue Kennedy (9 November 1774 – 15 May 1846) was an officer of the Royal Navy who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Kennedy was born into a family with a history of military service, and entered the navy s ...

, which entered ''Fougueux'' via her main deck ports and chains

A chain is a serial assembly of connected pieces, called links, typically made of metal, with an overall character similar to that of a rope in that it is flexible and curved in compression but linear, rigid, and load-bearing in tension. A c ...

. The French tried to defend the decks port by port, but were steadily overwhelmed. ''Fougueux''s captain, Louis Alexis Baudoin, had suffered a fatal wound earlier in the fighting, leaving Commander François Bazin in charge. When he learned that nearly all the officers were dead or wounded and that most of the guns were out of action, Bazin surrendered the ship to the boarders.

''Temeraire'' had by now fought both French ships to a standstill, at considerable cost to herself. She had sustained casualties of 47 killed and 76 wounded. All her sails and yards had been destroyed, only her lower masts remained, and the rudder head and starboard cathead

A cathead is a large wooden beam located on either side of the bow of a sailing ship, and angled forward at roughly 45 degrees. The beam is used to support the ship's anchor when raising it (weighing anchor) or lowering it (letting go), and for ...

had been shot away. of her starboard hull was staved in and both quarter galleries

A quarter gallery is an architectural feature of the stern of a sailing ship from around the 16th to the 19th century. Quarter galleries are a kind of balcony, typically placed on the sides of the sterncastle, the high, tower-like structure at th ...

had been destroyed. Harvey signalled for a frigate to tow his damaged ship out of the line, and came up to assist. Before ''Sirius'' could make contact, ''Temeraire'' came under fire from a counter-attack by the as-yet unengaged van of the combined fleet, led by Rear Admiral Pierre Dumanoir le Pelley

Vice-Admiral Count Pierre Étienne René Marie Dumanoir Le Pelley (2 August 1770 in Granville – 7 July 1829 in Paris) was a French Navy officer, best known for commanding the vanguard of the French fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar. His conduct d ...

. Harvey ordered the few guns that could be brought to bear fired in response, and the attack was eventually beaten off by fresh British ships arriving on the scene.

Storm

Shortly after the battle had ended, a severe gale struck the area. Several of the captured French and Spanish ships foundered in the rising seas, including both of ''Temeraire''s prizes, ''Fougueux'' and ''Redoutable''. Lost in the wrecks were a considerable number of their crews, as well as 47 ''Temeraire'' crewmen, serving asprize crew

A prize crew is the selected members of a ship chosen to take over the operations of a captured ship. Prize crews were required to take their prize to appropriate prize courts, which would determine whether the ship's officers and crew had sufficie ...

s. ''Temeraire'' rode out the storm following the battle, sometimes being taken in tow by less damaged ships, sometimes riding at anchor. She took aboard a number of Spanish and French prisoners transferred from other prizes, including some transferred from ''Euryalus'', which was serving as the temporary flagship of Cuthbert Collingwood, who was now in command as Nelson had been killed during the battle. Harvey took the opportunity to go aboard ''Euryalus'' and present his account of the battle to Collingwood, and so became the only captain to do so before Collingwood wrote his dispatch about the victory.

Return to England

''Temeraire'' finally put into Gibraltar on 2 November, eleven days after the battle had been fought. After undergoing minor repairs she sailed for England, arriving at Portsmouth on 1 December, three days before ''Victory'' passed by carrying Nelson's body. The battle-damaged ships quickly became tourist attractions, and visitors flocked to tour them. ''Temeraire'' was particularly popular on her arrival, being the only ship singled out by name in Collingwood's dispatch for her heroic conduct. Collingwood wrote:A circumstance occurred during the action which so strongly marks the invincible spirit of British seamen, when engaging the enemies of their country, that I cannot resist the pleasure I have in making it known to their Lordships; the ''Temeraire'' was boarded by accident; or design, by a French ship on one side, and a Spaniard on the other; the contest was vigorous, but, in the end the combined ensigns were torn from the poop and the British hoisted in their places.Collingwood's account, probably based largely on Harvey's report in the immediate aftermath of the battle, contained several errors. ''Temeraire'' had closely engaged two French ships, rather than a French and a Spanish ship, and had not been boarded by either during the action. Nevertheless, the account was popular and a print was rushed out purporting to show Harvey taking the lead in clearing ''Temeraire''s decks of enemy seamen.

A number of artists visited the newly returned Trafalgar ships, including John Livesay, drawing master at the

A number of artists visited the newly returned Trafalgar ships, including John Livesay, drawing master at the Royal Naval Academy

The Royal Naval Academy was a facility established in 1733 in Portsmouth Dockyard to train officers for the Royal Navy. The founders' intentions were to provide an alternative means to recruit officers and to provide standardised training, educa ...

. Livesay produced several sketches of battle-damaged ships, sending them to Nicholas Pocock

Nicholas Pocock (2 March 1740 – 9 March 1821) was an English artist known for his many detailed paintings of naval battles during the age of sail.

Birth and early career at sea

Pocock was born in Bristol in 1740, the son of a seaman.Chatte ...

to be used for Pocock's large paintings of the battle. ''Temeraire'' was one of the ships he sketched. Another visitor to Portsmouth was J. M. W. Turner. It is not known whether he visited ''Temeraire'', though he did go aboard ''Victory'', making preparatory notes and sketches and interviewing sailors who had been in the battle. The story of ''Temeraire'' had become firmly ingrained in the public mind, so much so that when the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

passed a vote of thanks to the men who had fought at Trafalgar, only three were specifically named. Nelson, Collingwood, and Harvey of ''Temeraire''.

Mediterranean and Baltic service

The battle-damaged ''Temeraire'' was almost immediately dry-docked in Portsmouth to undergo substantial repairs, which eventually lasted sixteen months and cost £25,352. She finally left the dockyard in mid-1807, now under the command of Captain Sir Charles Hamilton. Having fitted her for sea, Hamilton sailed to the Mediterranean in September and joined the fleet blockading the French in Toulon. The service was largely uneventful, and ''Temeraire'' returned to Britain in April 1808 to undergo repairs at Plymouth. During her time in Britain the strategic situation in Europe changed as Spain rebelled against French domination and entered the war against France. ''Temeraire'' sailed in June to join naval forces operating off the Spanish coast in support of anti-French forces in thePeninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

.

This service continued until early 1809, when she returned to Britain. By now Britain was heavily involved in the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

, protecting mercantile interests. An expedition under Sir James Gambier in July 1807 had captured most of the Danish Navy

The Royal Danish Navy ( da, Søværnet) is the sea-based branch of the Danish Defence force. The RDN is mainly responsible for maritime defence and maintaining the sovereignty of Danish territorial waters (incl. Faroe Islands and Greenland). Oth ...

at the Second Battle of Copenhagen

The Second Battle of Copenhagen (or the Bombardment of Copenhagen) (16 August – 7 September 1807) was a British bombardment of the Danish capital, Copenhagen, in order to capture or destroy the Dano-Norwegian fleet during the Napoleonic War ...

, in response to fears that it might fall into Napoleon's hands, at the cost of starting a war with Denmark. Captain Hamilton left the ship, and was superseded by Captain Edward Sneyd Clay

Rear-Admiral Edward Sneyd Clay ( – 3 February 1846) was an officer of the Royal Navy who served during the American War of Independence, and the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Clay entered the navy just before the end of the Ameri ...

. ''Temeraire'' now became the flagship of Rear Admiral Sir Manley Dixon, with orders to go to the Baltic to reinforce the fleet stationed there under Sir James Saumarez

Admiral of the Red James Saumarez, 1st Baron de Saumarez (or Sausmarez), GCB (11 March 1757 – 9 October 1836) was an admiral of the British Royal Navy, known for his victory at the Second Battle of Algeciras.

Early life

Saumarez was born ...

. ''Temeraire'' arrived in May 1809 and was sent to blockade Karlskrona

Karlskrona (, , ) is a locality and the seat of Karlskrona Municipality, Blekinge County, Sweden with a population of 66,675 in 2018. It is also the capital of Blekinge County. Karlskrona is known as Sweden's only baroque city and is host to Swed ...

on the Swedish coast.

While on patrol with the 64-gun and the frigate , ''Temeraire'' became involved in one of the heaviest Danish gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

attacks of the war. A party of men from ''Ardent'' had been landed on the island of Romsø, but were taken by surprise in a Danish night attack, which saw most of the ''Ardent'' men captured. The ''Melpomene'' was sent under a flag of truce to negotiate for their release, but on returning from this mission, was becalmed. A flotilla of thirty Danish gunboats then launched an attack, taking advantage of the stranded ''Melpomene''s inability to bring her broadside to bear on them. ''Melpomene'' signalled for help to the ''Temeraire'', which immediately dispatched boats to her assistance. They engaged and then drove off the Danish ships, and then helped the ''Melpomene'' to safety. She had been heavily damaged and suffered casualties of five killed and twenty-nine wounded. ''Temeraire''s later Baltic service involved being dispatched to observe the Russian fleet at Reval

Tallinn () is the most populous and capital city of Estonia. Situated on a bay in north Estonia, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea, Tallinn has a population of 437,811 (as of 2022) and administratively lies in the Harju ''m ...

, during which time she made a survey of the island of Nargen. After substantial blockading and convoy escort work, ''Temeraire'' was ordered back to Britain as winter arrived, and she arrived in Plymouth in November 1809.

Iberian service

After a period under repair in Plymouth, ''Temeraire'' was recommissioned under the command of Captain Edwin H. Chamberlayne in late January 1810. The Peninsular War had reached a critical stage, with the Spanish government besieged in Cadiz by the French. ''Temeraire'', now the flagship of Rear Admiral Francis Pickmore, was ordered to reinforce the city's water defences, and provided men from her sailor and marine complement to crew batteries and gunboats. Men from ''Temeraire'' were heavily involved in the fighting until July 1810, when Pickmore was ordered to sail to the Mediterranean and take up a new position as port admiral atMahón

Mahón (), officially Maó (), and also written as Mahon or Port Mahon in English, is the capital and second largest city of Menorca. The city is located on the eastern coast of the island, which is part of the archipelago and autonomous communi ...

. ''Temeraire'' was thereafter based either at Mahón or off Toulon with the blockading British fleet under Admiral Sir Edward Pellew

Admiral Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth, GCB (19 April 1757 – 23 January 1833) was a British naval officer. He fought during the American War of Independence, the French Revolutionary Wars, and the Napoleonic Wars. His younger brother I ...

. Chamberlayne was replaced by Captain Joseph Spear

Joseph Spear (died 1837) was an officer of the Royal Navy who served during the American War of Independence, and the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Spear joined the Royal Navy during the American War of Independence and soon saw act ...

in March 1811, and for the most part the blockade was uneventful. Though possessing a powerful fleet, the French commander avoided any contact with the blockading force and stayed in port, or else made very short voyages, returning to the harbour when the British appeared.

''Temeraire''s one brush with the French during this period came on 13 August 1811. Having received orders to sail to Menorca

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its capi ...

, Spear attempted to tack out of Hyères Bay. As he tried to do so, the wind fell away, leaving ''Temeraire'' becalmed and caught in a current which caused her to drift towards land. She came under fire from a shore battery on Pointe des Medes, which wounded several of her crew. Her boats were quickly manned, and together with boats sent from the squadron, ''Temeraire'' was towed out of range of the French guns. She then sailed to Menorca and underwent repairs. During this period an epidemic of yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

broke out, infecting nearly the entire crew and killing around a hundred crewmen. Pellew ordered her back to Britain, and health gradually improved as she sailed through the Atlantic.

Retirement

''Temeraire'' arrived in Plymouth on 9 February 1812 and was docked for a survey several weeks later. The survey reported that she was "a well built and strong ship but apparently much decay'd". Spear was superseded on 4 March by Captain Samuel Hood Linzee, but Linzee's command was short-lived. ''Temeraire'' left the dock on 13 March and was paid off one week later. Advances in naval technology had developed more powerful and strongly built warships, and though still comparatively new, ''Temeraire'' was no longer considered desirable for front-line service. While laid up the decision was taken to convert her into aprison ship

A prison ship, often more accurately described as a prison hulk, is a current or former seagoing vessel that has been modified to become a place of substantive detention for convicts, prisoners of war or civilian internees. While many nation ...

to alleviate overcrowding caused by large influxes of French prisoners from the Peninsular War campaigns. Conversion work was carried out at Plymouth between November and December 1813, after which she was laid up in the River Tamar

The Tamar (; kw, Dowr Tamar) is a river in south west England, that forms most of the border between Devon (to the east) and Cornwall (to the west). A part of the Tamar Valley is a World Heritage Site due to its historic mining activities.

T ...

as a prison hulk. From 1814 she was under the nominal command of Lieutenant John Wharton. Despite being laid up and disarmed ''Temeraire'' and the rest of her class were nominally re-rated as 104-gun first rate

In the rating system of the British Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a first rate was the designation for the largest ships of the line. Originating in the Jacobean era

The Jacobean era was the period in English and Scot ...

s in February 1817.

''Temeraire''s service as a prison ship lasted until 1819, at which point she was selected for conversion to a receiving ship

A hulk is a ship that is afloat, but incapable of going to sea. Hulk may be used to describe a ship that has been launched but not completed, an abandoned wreck or shell, or to refer to an old ship that has had its rigging or internal equipmen ...

. She was extensively refitted at Plymouth between September 1819 and June 1820 at a cost of £27,733, and then sailed to Sheerness Dockyard

Sheerness Dockyard also known as the Sheerness Station was a Royal Navy Dockyard located on the Sheerness peninsula, at the mouth of the River Medway in Kent. It was opened in the 1660s and closed in 1960.

Location

In the Age of Sail, the R ...

. As a receiving ship she served as a temporary berth for new naval recruits until they received a posting to a ship. She fulfilled this role for eight years, until becoming a victualling depot in 1829. Her final role was as a guard ship

A guard ship is a warship assigned as a stationary guard in a port or harbour, as opposed to a coastal patrol boat, which serves its protective role at sea.

Royal Navy

In the Royal Navy of the eighteenth century, peacetime guard ships were usual ...

at Sheerness, under the title "Guardship of the Ordinary and Captain-Superintendent's ship of the Fleet Reserve in the Medway". This final post as flagship of the Medway Reserve involved her being repainted and rearmed, and she was used to train boys belonging to The Marine Society

The Marine Society is a British charity, the world's first established for seafarers. In 1756, at the beginning of the Seven Years' War against France, Austria, and Saxony (and subsequently the Mughal Empire, Spain, Russia and Sweden) Britain urg ...

. For the last two years of her service, from 1836 to 1838 she was under the nominal command of Captain Thomas Fortescue Kennedy, in his post as Captain-Superintendent of Sheerness. Kennedy had been ''Temeraire''s first-lieutenant at Trafalgar.

Sale and disposal

Kennedy received orders from the Admiralty in June 1838 to have ''Temeraire'' valued in preparation for her sale out of the service. She fired her guns for the last time on 28 June in celebration of theCoronation of Queen Victoria

The coronation of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom took place on Thursday, 28 June 1838, just over a year after she succeeded to the throne of the United Kingdom at the age of 18. The ceremony was held in Westminster Abbey after a public p ...

, and work began on dismantling her on 4 July. Kennedy delegated this task to Captain Sir John Hill, commander of . Her masts, stores and guns were all removed and her crew paid off, before ''Temeraire'' was put up for sale with twelve other ships. She was sold by Dutch auction

A Dutch auction is one of several similar types of auctions for buying or selling goods. Most commonly, it means an auction in which the auctioneer begins with a high asking price in the case of selling, and lowers it until some participant accep ...

on 16 August 1838 to John Beatson, a shipbreaker based at Rotherhithe

Rotherhithe () is a district of south-east London, England, and part of the London Borough of Southwark. It is on a peninsula on the south bank of the Thames, facing Wapping, Shadwell and Limehouse on the north bank, as well as the Isle of Dogs ...

for £5,530. Beatson was then faced with the task of transporting the ship 55 miles from Sheerness to Rotherhithe, the largest ship to have attempted this voyage. To accomplish this he hired two steam tugs

Steam is a substance containing water in the gas phase, and sometimes also an aerosol of liquid water droplets, or air. This may occur due to evaporation or due to boiling, where heat is applied until water reaches the enthalpy of vaporization. ...

from the Thames Steam Towing Company and employed a Rotherhithe pilot

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its directional flight controls. Some other aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are also considered aviators, because they a ...

named William Scott and twenty five men to sail her up the Thames, at a cost of £58.

Last voyage

The tugs took the

The tugs took the hulk

The Hulk is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. Created by writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, the character first appeared in the debut issue of ''The Incredible Hulk (comic book), The Incredible Hulk' ...

of ''Temeraire'' in tow at 7:30 am on 5 September 1838, taking advantage of the beginning of the slack water

Slack water is a short period in a body of tidal water when the water is completely unstressed, and there is no movement either way in the tidal stream, and which occurs before the direction of the tidal stream reverses. Slack water can be esti ...

. They had reached Greenhithe

Greenhithe is a village in the Borough of Dartford in Kent, England, and the civil parish of Swanscombe and Greenhithe. It is located east of Dartford and west of Gravesend.

Area

In the past, Greenhithe's waterfront on the estuary of the riv ...

by 1:30 pm at the ebb of the tide, where they anchored overnight. They resumed the journey at 8:30 am the following day, passing Woolwich

Woolwich () is a district in southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was maintained throu ...

and then Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

at noon. They reached Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains throug ...

Reach shortly afterwards and brought her safely to Beatson's Wharf at Rotherhithe

Rotherhithe () is a district of south-east London, England, and part of the London Borough of Southwark. It is on a peninsula on the south bank of the Thames, facing Wapping, Shadwell and Limehouse on the north bank, as well as the Isle of Dogs ...

at 2 pm. This was a breakers' yard owned by the Beatson family.

''Temeraire'' was hauled up onto the mud, where she lay as she was slowly broken up. The final voyage was announced in a number of papers, and thousands of spectators came to see her towed up the Thames or laid up at Beatson's yard. The shipbreakers undertook a thorough dismantling, removing all the copper sheathing, rudder pintle

A pintle is a pin or bolt, usually inserted into a gudgeon, which is used as part of a pivot or hinge. Other applications include pintle and lunette ring for towing, and pintle pins securing casters in furniture.

Use

Pintle/gudgeon sets have ma ...

s and gudgeon

A gudgeon is a socket-like, cylindrical (i.e., ''female'') fitting attached to one component to enable a pivoting or hinging connection to a second component. The second component carries a pintle fitting, the male counterpart to the gudgeon, ...

s, copper bolts, nails and other fastenings to be sold back to the Admiralty. The timber was mostly sold to house builders and shipyard owners, though some was retained for working into specialist commemorative furniture.

Legacy

The immediate legacy of ''Temeraire'' was the use of the timber taken from her as she was broken up. A gong stand made from ''Temeraire'' timber was a wedding present to the future KingGeorge V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

on the occasion of his marriage to Mary of Teck

Mary of Teck (Victoria Mary Augusta Louise Olga Pauline Claudine Agnes; 26 May 186724 March 1953) was List of British royal consorts, Queen of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 6 May 1910 until 20 Janua ...

, and is held at Balmoral Castle

Balmoral Castle () is a large estate house in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and a residence of the British royal family. It is near the village of Crathie, west of Ballater and west of Aberdeen.

The estate and its original castle were bought ...

. A barometer

A barometer is a scientific instrument that is used to measure air pressure in a certain environment. Pressure tendency can forecast short term changes in the weather. Many measurements of air pressure are used within surface weather analysis ...

, gavel

A gavel is a small ceremonial mallet commonly made of hardwood, typically fashioned with a handle. It can be used to call for attention or to punctuate rulings and proclamations and is a symbol of the authority and right to act officially in the ...

, and some miscellaneous timber are in the collections of the National Maritime Museum

The National Maritime Museum (NMM) is a maritime museum in Greenwich, London. It is part of Royal Museums Greenwich, a network of museums in the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site. Like other publicly funded national museums in the United ...

, and chairs made from ''Temeraire'' oak are in the possession of the Royal Naval Museum

The National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth, formerly known as the Royal Naval Museum, is a museum of the history of the Royal Navy located in the Portsmouth Historic Dockyard section of HMNB Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Hampshire, England. The ...

, Portsmouth, Lloyd's Register

Lloyd's Register Group Limited (LR) is a technical and professional services organisation and a maritime classification society, wholly owned by the Lloyd’s Register Foundation, a UK charity dedicated to research and education in science and ...

, London and the Whanganui Regional Museum, Whanganui

Whanganui (; ), also spelled Wanganui, is a city in the Manawatū-Whanganui region of New Zealand. The city is located on the west coast of the North Island at the mouth of the Whanganui River, New Zealand's longest navigable waterway. Whangan ...

. An altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in paga ...

, communion rail

The altar rail (also known as a communion rail or chancel rail) is a low barrier, sometimes ornate and usually made of stone, wood or metal in some combination, delimiting the chancel or the sanctuary and altar in a church, from the nave and oth ...

and two bishop's chairs survive in St. Mary's Church, Rotherhithe. A ship model

Ship models or model ships are scale models of ships. They can range in size from 1/6000 scale wargaming miniatures to large vessels capable of holding people.

Ship modeling is a craft as old as shipbuilding itself, stretching back to ancient t ...

of ''Temeraire'' made by prisoners of war uses a stand made from wood taken from her, and is currently in the Watermen's Hall

The Company of Watermen and Lightermen (CWL) is a historic livery company, City guild in the City of London. However, unlike the city's other 109 livery company, livery companies, CWL does not have a grant of livery. Its meeting rooms are at Wat ...

in London. Other relics of ''Temeraire'' known to exist or have existed are a tea caddy

A tea caddy is a box, jar, canister, or other receptacle used to store tea. When first introduced to Europe from Asia, tea was extremely expensive, and kept under lock and key. The containers used were often expensive and decorative, to fit in wi ...

made for her signal midshipman at Trafalgar, James Eaton

James Eaton (1783–1856/1857) was an officer of the Royal Navy. He served aboard at the Battle of Trafalgar; as signal midshipman, he was the first person to pass on Nelson's famous signal to the fleet; "England expects that every man will ...

, and sold at auction in 2000, the frame for an oil painting by Sir Edwin Landseer

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer (7 March 1802 – 1 October 1873) was an English painter and sculptor, well known for his paintings of animals – particularly horses, dogs, and stags. However, his best-known works are the lion sculptures at the bas ...

titled ''Neptune'', and a mantelpiece