HMS Royal George (1756) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Royal George'' was a

Due to problems encountered during the

Due to problems encountered during the  ''Royal George'' joined the

''Royal George'' joined the

On 28 August 1782 ''Royal George'' was preparing to sail with Admiral Howe's fleet on another relief of Gibraltar. The ships were anchored at Spithead to take on supplies. Most of her complement were aboard ship, as were a large number of workmen to speed the repairs. There were also an estimated 200–300 relatives visiting the officers and men, 100–200 "ladies from the Point t Portsmouth who, though seeking neither husbands or fathers, yet visit our newly arrived ships of war", and a number of merchants and traders come to sell their wares to the seamen. The reason most of her complement were aboard was because of fear of desertion: all shore leave had been canceled. Accordingly, every crew member then assigned to the vessel was aboard it when it sank, except for a detachment of sixty marines sent ashore that morning.

The exact number of the total crew on board is unknown, but is estimated to be around 1,200.

At seven o'clock on the morning of 29 August work on the hull was carried out and ''Royal George'' was heeled over by rolling the ship's starboard guns into the centreline of the ship. This caused the ship to tilt over in the water to port. Further, the loading of a large number of casks of rum on the now-low port side created additional and, it turned out, unstable weight. The ship was heeled over too far, passing her

On 28 August 1782 ''Royal George'' was preparing to sail with Admiral Howe's fleet on another relief of Gibraltar. The ships were anchored at Spithead to take on supplies. Most of her complement were aboard ship, as were a large number of workmen to speed the repairs. There were also an estimated 200–300 relatives visiting the officers and men, 100–200 "ladies from the Point t Portsmouth who, though seeking neither husbands or fathers, yet visit our newly arrived ships of war", and a number of merchants and traders come to sell their wares to the seamen. The reason most of her complement were aboard was because of fear of desertion: all shore leave had been canceled. Accordingly, every crew member then assigned to the vessel was aboard it when it sank, except for a detachment of sixty marines sent ashore that morning.

The exact number of the total crew on board is unknown, but is estimated to be around 1,200.

At seven o'clock on the morning of 29 August work on the hull was carried out and ''Royal George'' was heeled over by rolling the ship's starboard guns into the centreline of the ship. This caused the ship to tilt over in the water to port. Further, the loading of a large number of casks of rum on the now-low port side created additional and, it turned out, unstable weight. The ship was heeled over too far, passing her

In 1782, Charles Spalding recovered six iron 12-pounder guns and nine brass 12-pounders using a

In 1782, Charles Spalding recovered six iron 12-pounder guns and nine brass 12-pounders using a

A 24-pounder from the ship is part of the

A 24-pounder from the ship is part of the  Recovered materials were used to make a variety of souvenirs. In the 1850s, timber from the ship was used to make the

Recovered materials were used to make a variety of souvenirs. In the 1850s, timber from the ship was used to make the

''Royal George''

fro

Loss of the Royal George at Spithead, 1782

Sinking of H.M.S. Royal George at Spithead Augt 29 1782

{{DEFAULTSORT:Royal George (1756) Ships of the line of the Royal Navy Shipwrecks in the Solent Military history of Hampshire Maritime incidents in 1782 1756 ships Ships built in Woolwich Archaeology of shipwrecks Maritime archaeology Underwater archaeology 1782 in Great Britain

ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

. A first-rate

In the rating system of the British Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a first rate was the designation for the largest ships of the line. Originating in the Jacobean era with the designation of Ships Royal capable of carrying a ...

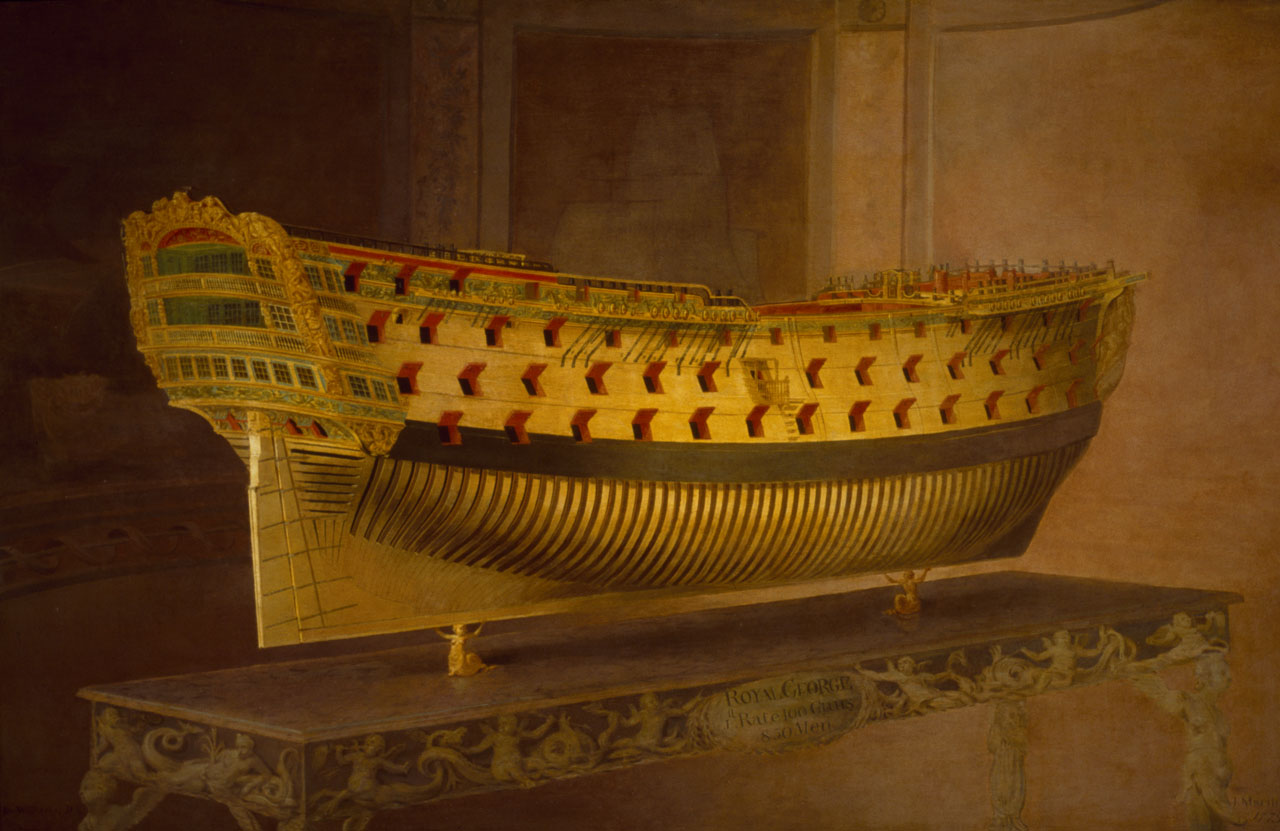

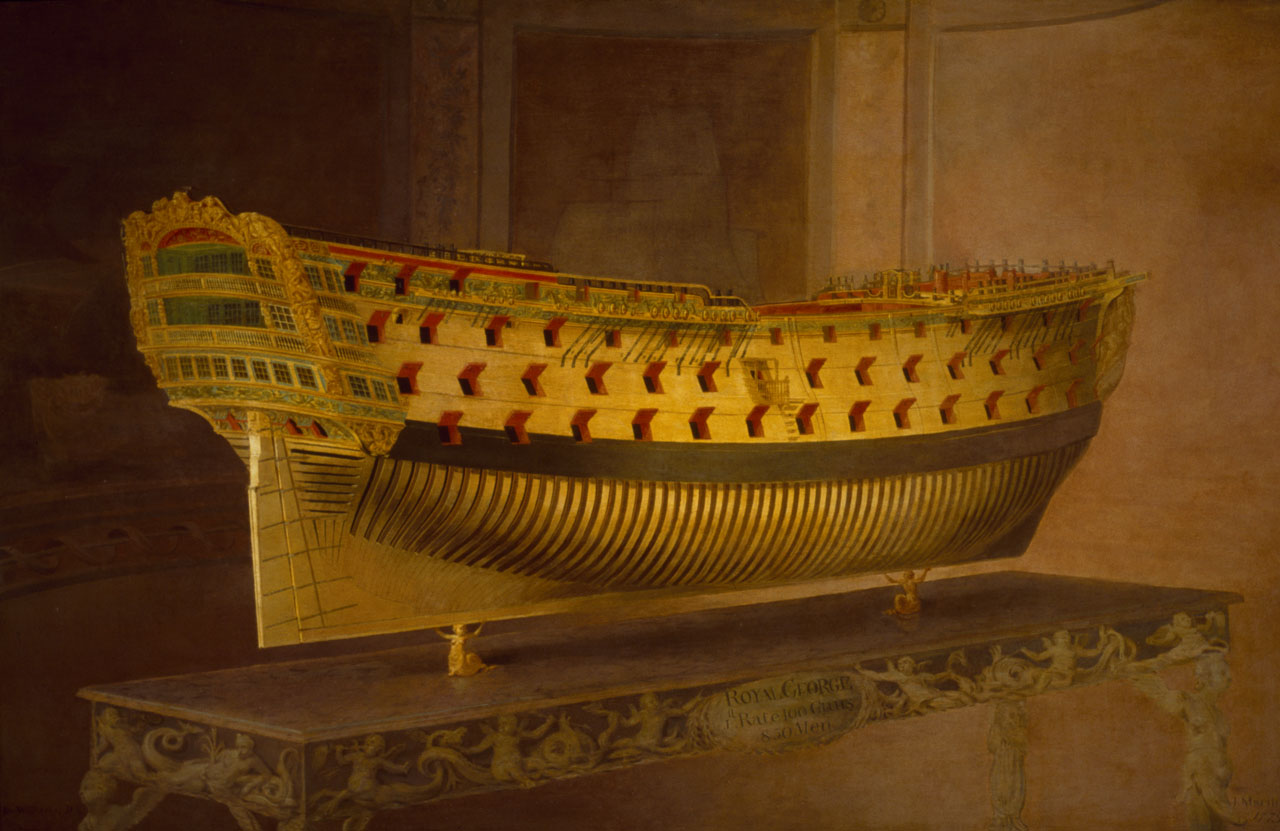

with 100 guns on three decks, she was the largest warship in the world at the time of her launch on 18 February 1756. Construction at Woolwich Dockyard

Woolwich Dockyard (formally H.M. Dockyard, Woolwich, also known as The King's Yard, Woolwich) was an English naval dockyard along the river Thames at Woolwich in north-west Kent, where many ships were built from the early 16th century until ...

had taken ten years.

The ship saw immediate service during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754– ...

, including the Raid on Rochefort

The Raid on Rochefort (or Descent on Rochefort) was a British amphibious attempt to capture the French Atlantic port of Rochefort in September 1757 during the Seven Years' War. The raid pioneered a new tactic of "descents" on the French coast, ...

in 1757. She was Admiral Sir Edward Hawke

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, KB, PC (21 February 1705 – 17 October 1781), of Scarthingwell Hall in the parish of Towton, near Tadcaster, Yorkshire, was a Royal Navy officer. As captain of the third-rate , he took part in the Battle of T ...

's flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the f ...

at the Battle of Quiberon Bay

The Battle of Quiberon Bay (known as ''Bataille des Cardinaux'' in French) was a decisive naval engagement during the Seven Years' War. It was fought on 20 November 1759 between the Royal Navy and the French Navy in Quiberon Bay, off the coast ...

in 1759. The ship was laid up

A reserve fleet is a collection of naval vessels of all types that are fully equipped for service but are not currently needed; they are partially or fully decommissioned. A reserve fleet is informally said to be "in mothballs" or "mothballed"; a ...

following the conclusion of the war in 1763, but was reactivated in 1777 for the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of ...

. She then served as Rear Admiral Robert Digby's flagship at the Battle of Cape St Vincent in 1780.

''Royal George'' sank on 29 August 1782 whilst anchored at Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshir ...

off Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city status in the United Kingdom, city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is admi ...

. The ship was intentionally rolled so maintenance could be performed on the hull, but the roll became unstable and out of control; the ship took on water and sank. More than 800 people died, making it one of the most deadly maritime disasters in British territorial waters

The term territorial waters is sometimes used informally to refer to any area of water over which a sovereign state has jurisdiction, including internal waters, the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone, and potenti ...

.

Several attempts were made to raise the vessel, both for salvage and because she was a major hazard to navigation in the Solent

The Solent ( ) is a strait between the Isle of Wight and Great Britain. It is about long and varies in width between , although the Hurst Spit which projects into the Solent narrows the sea crossing between Hurst Castle and Colwell Bay ...

. In 1782, Charles Spalding recovered fifteen 12-pounder guns using a diving bell

A diving bell is a rigid chamber used to transport divers from the surface to depth and back in open water, usually for the purpose of performing underwater work. The most common types are the open-bottomed wet bell and the closed bell, which c ...

of his own design. From 1834 to 1836, Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was ...

and John Deane recovered more guns using a diving helmet

A diving helmet is a rigid head enclosure with a breathing gas supply used in underwater diving. They are worn mainly by professional divers engaged in surface-supplied diving, though some models can be used with scuba equipment. The upper par ...

they had invented. In 1839 Charles Pasley

General Sir Charles William Pasley (8 September 1780 – 19 April 1861) was a British soldier and military engineer who wrote the defining text on the role of the post- American Revolution British Empire: ''An Essay on the Military Policy and ...

of the Royal Engineers commenced operations to break up the wreck using barrels of gunpowder. Pasley's team recovered more guns and other items between 1839 and 1842. In 1840, they destroyed the remaining structure of the wreck in an explosion which shattered windows several miles away in Portsmouth and Gosport

Gosport ( ) is a town and non-metropolitan borough on the south coast of Hampshire, South East England. At the 2011 Census, its population was 82,662. Gosport is situated on a peninsula on the western side of Portsmouth Harbour, opposite ...

.

Service

Due to problems encountered during the

Due to problems encountered during the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George' ...

(1740–48), the Admiralty attempted to modernise British ship designs with the 1745 Establishment

The 1745 Establishment was the third and final formal establishment of dimensions for ships to be built for the Royal Navy. It completely superseded the previous 1719 Establishment, which had subsequently been modified in 1733 and again in 1741 ...

. On 29 August 1746, the Admiralty ordered construction of a 100-gun first rate

In the rating system of the British Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. A ...

of the new design, to be named ''Royal Anne''. She was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

at Woolwich Dockyard

Woolwich Dockyard (formally H.M. Dockyard, Woolwich, also known as The King's Yard, Woolwich) was an English naval dockyard along the river Thames at Woolwich in north-west Kent, where many ships were built from the early 16th century until ...

in 1746 but was unfinished when the war ended in 1748, causing construction to slow. The ship was renamed ''Royal George'' while under construction. She was not completed until 1756, during the Diplomatic Revolution, a few months before the outbreak of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754– ...

(1756–63). The ship was commissioned in October 1755, before she was ready to launch, with her first commander being Captain Richard Dorrill. She was launched on 18 February 1756. The largest warship in the world at the time, she displaced more than 2,000 tons and was the "eighteenth-century equivalent of a weapon of mass destruction".

''Royal George'' joined the

''Royal George'' joined the Western Squadron

The Western Squadron was a squadron or formation of the Royal Navy based at Plymouth Dockyard. It operated in waters of the English Channel, the Western Approaches, and the North Atlantic. It defended British trade sea lanes from 1650 to 1814 and ...

(also known as the Channel Fleet) under Admiral Sir Edward Hawke

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, KB, PC (21 February 1705 – 17 October 1781), of Scarthingwell Hall in the parish of Towton, near Tadcaster, Yorkshire, was a Royal Navy officer. As captain of the third-rate , he took part in the Battle of T ...

in May 1756, just as the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754– ...

began. Captain Dorrill was succeeded by Captain John Campbell in July 1756, who was in turn succeeded by Captain Matthew Buckle in early 1757. ''Royal George'' was used as the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the f ...

of Vice-Admiral Edward Boscawen

Admiral of the Blue Edward Boscawen, PC (19 August 171110 January 1761) was a British admiral in the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament for the borough of Truro, Cornwall, England. He is known principally for his various naval commands durin ...

in this period, including flying his flag during the Raid on Rochefort

The Raid on Rochefort (or Descent on Rochefort) was a British amphibious attempt to capture the French Atlantic port of Rochefort in September 1757 during the Seven Years' War. The raid pioneered a new tactic of "descents" on the French coast, ...

in September 1757. Captain Piercy Brett

Admiral Sir Peircy Brett (1709 – 14 October 1781) was a Royal Navy officer. As a junior officer he served on George Anson's voyage around the world and commanded the landing party which sacked and burned the town of Paita in November 1741. Du ...

took command in 1758, and ''Royal George'' became the flagship of Admiral Lord George Anson in the same year. Brett was succeeded by Captain Alexander Hood in November 1758. The former captain, Richard Dorrill, returned to command the ship the following year, until being invalided in June 1759. Dorrill's replacement was another former captain, John Campbell, who commanded her during the blockade of the French fleet at Brest. She became Sir Edward Hawke

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, KB, PC (21 February 1705 – 17 October 1781), of Scarthingwell Hall in the parish of Towton, near Tadcaster, Yorkshire, was a Royal Navy officer. As captain of the third-rate , he took part in the Battle of T ...

's flagship in early November 1759, when his previous flagship, , went into dock for repairs. Hawke commanded the fleet from ''Royal George'' at the Battle of Quiberon Bay

The Battle of Quiberon Bay (known as ''Bataille des Cardinaux'' in French) was a decisive naval engagement during the Seven Years' War. It was fought on 20 November 1759 between the Royal Navy and the French Navy in Quiberon Bay, off the coast ...

on 20 November 1759, where she sank the French ship ''Superbe''.

''Royal George'' was commanded by Captain William Bennett from March 1760, and she was present at the fleet review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

at Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshir ...

in July that year. John Campbell returned to command his old ship in August 1760, though Bennett was captain again by December. ''Royal George'' joined Admiral Charles Hardy

Sir Charles Hardy (c. 1714 – 18 May 1780) was a Royal Navy officer and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1764 and 1780. He served as colonial governor of New York from 1755 to 1757.

Early career

Born at Portsmouth, the ...

’s fleet in the Autumn of 1762. With peace approaching, and the enormous cost of crewing and provisioning such a large ship, the crew were paid off

Ship commissioning is the act or ceremony of placing a ship in active service and may be regarded as a particular application of the general concepts and practices of project commissioning. The term is most commonly applied to placing a warship i ...

on 18 December 1762. The ship was laid up in ordinary at the conclusion of the war, along with most other first rates in the fleet. Whilst laid up, ''Royal George'' underwent a major repair at Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymout ...

between 1765 and 1768.

The ship was reactivated after the outbreak of the American War of Independence (1775–83), being re-fitted for service at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city status in the United Kingdom, city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is admi ...

between May 1778 and April 1779. She re-commissioned under Captain Thomas Hallum in July 1778, with command passing to Captain John Colpoys

Admiral Sir John Colpoys, (''c.'' 1742 – 4 April 1821) was an officer of the British Royal Navy who served in three wars but is most notable for being one of the catalysts of the Spithead Mutiny in 1797 after ordering his marines to fire ...

in November that year. ''Royal George'' was again assigned to the Channel Fleet, where she was flagship of Vice-Admiral Sir Robert Harland. Vice-Admiral George Darby

Vice Admiral George Darby (c.1720 – 1790) was a Royal Navy officer. He commanded HMS ''Norwich'' at the capture of Martinique in 1762 during the Seven Years' War. He went on to command the Channel Fleet during the American Revolutionary ...

briefly replaced Harland in June 1779, then from August 1779 to December 1781 she was the flagship of Rear-Admiral Sir John Lockhart Ross. Meanwhile, Captain Colpoys was replaced by Captain John Bourmaster in December 1779, and she joined Admiral Sir George Rodney's fleet in their mission to relieve Gibraltar. Under Bourmaster, and flying Ross's flag, ''Royal George'' took part in the attack on the Caracas convoy on 8 January 1780, the Battle of Cape St. Vincent on 16 January, and took part in the successful relief of Gibraltar three days later.

''Royal George'' returned to Britain with the rest of the fleet, and had her hull coppered

Copper sheathing is the practice of protecting the under-water hull of a ship or boat from the corrosive effects of salt water and biofouling through the use of copper plates affixed to the outside of the hull. It was pioneered and developed b ...

in April 1780. She returned to service that summer, serving with the Channel Fleet under Admiral Francis Geary, and then George Darby again from the autumn. Both captain and admiral changed again in late 1781, Bourmaster being replaced by Captain Henry Cromwell, and Ross by Rear-Admiral Richard Kempenfelt

Rear-Admiral Richard Kempenfelt (1718 – 29 August 1782) was a British rear admiral who gained a reputation as a naval innovator. He is best known for his victory against the French at the Second Battle of Ushant and for his death when accid ...

. She served as part of Samuel Barrington

Admiral Samuel Barrington (1729 – 16 August 1800) was a Royal Navy officer. Barrington was the fourth son of John Barrington, 1st Viscount Barrington of Beckett Hall at Shrivenham in Berkshire (now Oxfordshire). He enlisted in the navy a ...

's squadron from April 1782, with Cromwell replaced by Captain Martin Waghorn

Martin Waghorn (died 17 December 1787) was an officer of the Royal Navy. He served during the Seven Years' War and the American War of Independence, but is chiefly remembered for being commanding officer of when she suddenly sank at Spithead ...

in May. ''Royal George'' then joined the fleet under Richard Howe

Admiral of the Fleet (Royal Navy), Admiral of the Fleet Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe, (8 March 1726 – 5 August 1799) was a Kingdom of Great Britain, British naval officer. After serving throughout the War of the Austrian Succession, he g ...

.

Loss

On 28 August 1782 ''Royal George'' was preparing to sail with Admiral Howe's fleet on another relief of Gibraltar. The ships were anchored at Spithead to take on supplies. Most of her complement were aboard ship, as were a large number of workmen to speed the repairs. There were also an estimated 200–300 relatives visiting the officers and men, 100–200 "ladies from the Point t Portsmouth who, though seeking neither husbands or fathers, yet visit our newly arrived ships of war", and a number of merchants and traders come to sell their wares to the seamen. The reason most of her complement were aboard was because of fear of desertion: all shore leave had been canceled. Accordingly, every crew member then assigned to the vessel was aboard it when it sank, except for a detachment of sixty marines sent ashore that morning.

The exact number of the total crew on board is unknown, but is estimated to be around 1,200.

At seven o'clock on the morning of 29 August work on the hull was carried out and ''Royal George'' was heeled over by rolling the ship's starboard guns into the centreline of the ship. This caused the ship to tilt over in the water to port. Further, the loading of a large number of casks of rum on the now-low port side created additional and, it turned out, unstable weight. The ship was heeled over too far, passing her

On 28 August 1782 ''Royal George'' was preparing to sail with Admiral Howe's fleet on another relief of Gibraltar. The ships were anchored at Spithead to take on supplies. Most of her complement were aboard ship, as were a large number of workmen to speed the repairs. There were also an estimated 200–300 relatives visiting the officers and men, 100–200 "ladies from the Point t Portsmouth who, though seeking neither husbands or fathers, yet visit our newly arrived ships of war", and a number of merchants and traders come to sell their wares to the seamen. The reason most of her complement were aboard was because of fear of desertion: all shore leave had been canceled. Accordingly, every crew member then assigned to the vessel was aboard it when it sank, except for a detachment of sixty marines sent ashore that morning.

The exact number of the total crew on board is unknown, but is estimated to be around 1,200.

At seven o'clock on the morning of 29 August work on the hull was carried out and ''Royal George'' was heeled over by rolling the ship's starboard guns into the centreline of the ship. This caused the ship to tilt over in the water to port. Further, the loading of a large number of casks of rum on the now-low port side created additional and, it turned out, unstable weight. The ship was heeled over too far, passing her centre of gravity

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force may ...

. Realising that the ship was settling in the water, the ship's carpenter informed the lieutenant of the watch, Monin Hollingbery, and asked him to beat the drum to signal to the men to right the ship. The officer refused. As the situation worsened, the carpenter implored the officer a second time. A second time he was refused. The carpenter then took his concern directly to the ship's captain, who agreed with him and gave the order to move the guns back into position. By this time, however, the ship had already taken on too much water through its port-side gun ports, and the drum was never sounded. The ship tilted heavily to port, causing a sudden inrush of water and a burst of air out the starboard side. The barge along the port side which had been unloading the rum was caught in the masts as the ship turned, briefly delaying the sinking, but losing most of her crew. ''Royal George'' quickly filled with water and sank, taking with her around 900 people, including up to 300 women and 60 children who were visiting the ship in harbour. 255 people were saved, including eleven women and one child. Some escaped by running up the rigging, while others were picked up by boats from other vessels. Kempenfelt was writing in his cabin when the ship sank; the cabin doors had jammed because of the ship's heeling and he perished. Waghorn was injured and thrown into the water, but he was rescued. The carpenter survived the sinking, but died less than a day later, never having regained consciousness. Hollingbery also survived.

Many of the victims were washed ashore at Ryde

Ryde is an English seaside town and civil parish on the north-east coast of the Isle of Wight. The built-up area had a population of 23,999 according to the 2011 Census and an estimate of 24,847 in 2019. Its growth as a seaside resort came a ...

, Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a Counties of England, county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the List of islands of England#Largest islands, largest and List of islands of England#Mo ...

, where they were buried in a mass grave that stretched along the beach. This land was reclaimed in the development of a Victorian esplanade and is now occupied by the streets and properties of Ryde Esplanade and The Strand. In April 2009, Isle of Wight Council placed a new memorial plaque in the newly restored Ashley Gardens on Ryde Esplanade in memory of ''Royal George''. It is a copy of the original plaque unveiled in 1965 by Earl Mountbatten of Burma, which was moved in 2006 to the Royal George Memorial Garden, also on the Esplanade.

A court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of mem ...

acquitted the officers and crew (many of whom had perished), blaming the accident on the "general state of decay of her timbers" and suggesting that the most likely cause of the sinking was that part of the frame of the ship gave way under the stress of the heel. Most historians conclude that Hollingbery was most responsible for the sinking. For example, naval historian Nicholas Tracy stated that Hollingbery allowed water to accumulate on the gundeck. The resulting free surface effect

The free surface effect is a mechanism which can cause a watercraft to become unstable and capsize.

It refers to the tendency of liquids — and of unbound aggregates of small solid objects, like seeds, gravel, or crushed ore, whose behavior a ...

eventually compromised the ship's stability. Tracy concluded that an "alert officer of the watch would have prevented the tragedy ..."

This narrative was disputed by historian Hilary L. Rubinstein in 2020. Rubinstein declares Hollingbery innocent, placing blame on others, and argues that Kempenfelt may not have been trapped in his cabin.

A fund was established by Lloyd's Coffee House to help the widows and children of the sailors lost in the sinking, which was the start of what eventually became the Lloyd's Patriotic Fund Lloyd's Patriotic Fund was founded on 28 July 1803 at Lloyd's Coffee House, and continues to the present day. Lloyd’s Patriotic Fund now works closely with armed forces charities to identify the individuals and their families who are in urgent ne ...

. The accident was commemorated in verse by the poet William Cowper

William Cowper ( ; 26 November 1731 – 25 April 1800) was an English poet and Anglican hymnwriter. One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th-century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and sce ...

:

Salvage attempts

Initial attempts

Several attempts were made to raise the vessel, both for salvage and because she was a major hazard to navigation, lying in a busy harbour at a depth of only . In 1782, Charles Spalding recovered six iron 12-pounder guns and nine brass 12-pounders using a

In 1782, Charles Spalding recovered six iron 12-pounder guns and nine brass 12-pounders using a diving bell

A diving bell is a rigid chamber used to transport divers from the surface to depth and back in open water, usually for the purpose of performing underwater work. The most common types are the open-bottomed wet bell and the closed bell, which c ...

of his design.

Deane brothers (1834)

No further work was carried out on the wreck until 1834, when Charles Anthony Deane and his brotherJohn

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Seco ...

, using the first air-pumped diving helmet

A diving helmet is a rigid head enclosure with a breathing gas supply used in underwater diving. They are worn mainly by professional divers engaged in surface-supplied diving, though some models can be used with scuba equipment. The upper par ...

which they had invented, began work. From 1834 to 1836 they recovered 7 iron 42-pounders, 18 brass 24-pounders and 3 brass 12-pounders for which he received salvage from the Board of Ordnance

The Board of Ordnance was a British government body. Established in the Tudor period, it had its headquarters in the Tower of London. Its primary responsibilities were 'to act as custodian of the lands, depots and forts required for the defence o ...

. The remaining guns were buried under mud and the timbers of the wreck and were unrecoverable.

It was during this operation that local fishermen asked the divers to investigate something on the seabed that their nets kept snagging. A dive by John Deane north east of ''Royal George'' revealed timbers and guns from ''Mary Rose

The ''Mary Rose'' (launched 1511) is a carrack-type warship of the English Tudor navy of King Henry VIII. She served for 33 years in several wars against France, Scotland, and Brittany. After being substantially rebuilt in 1536, she saw her ...

'', the first time that its resting place had been located in centuries.

Pasley (1839)

In 1839 Major-GeneralCharles Pasley

General Sir Charles William Pasley (8 September 1780 – 19 April 1861) was a British soldier and military engineer who wrote the defining text on the role of the post- American Revolution British Empire: ''An Essay on the Military Policy and ...

, at the time a colonel of the Royal Engineers, commenced operations. Pasley had previously destroyed some old wrecks in the Thames to clear a channel using gunpowder charges; his plan was to break up the wreck of ''Royal George'' in a similar way and then salvage as much as possible using divers

Diver or divers may refer to:

*Diving (sport), the sport of performing acrobatics while jumping or falling into water

*Practitioner of underwater diving, including:

**scuba diving,

**freediving,

**surface-supplied diving,

**saturation diving, a ...

. The charges used were made from oak barrels filled with gunpowder and covered with lead. They were initially detonated using chemical fuses, but this was later changed to an electrical system using a resistance-heated platinum wire to detonate the gunpowder.

Pasley's operation set many diving milestones, including the first recorded use of the buddy system

The buddy system is a procedure in which two individuals, the "buddies", operate together as a single unit so that they are able to monitor and help each other.

As per Merriam-Webster, the first known use of the phrase "buddy system" goes as far ...

in diving, when he ordered that his divers operate in pairs. In addition, a Corporal Jones made the first emergency swimming ascent after his air line became tangled and he had to cut it free. A less fortunate milestone was the first medical account of a diver squeeze suffered by a Private Williams: the early diving helmets used had no non-return valve

A check valve, non-return valve, reflux valve, retention valve, foot valve, or one-way valve is a valve that normally allows fluid (liquid or gas) to flow through it in only one direction.

Check valves are two-port valves, meaning they have ...

s; this meant that if a hose became severed, the high-pressure air around the diver's head rapidly evacuated the helmet, causing tremendous negative pressure with extreme and sometimes life-threatening effects. At the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Ch ...

meeting in 1842, Sir John Richardson described the diving apparatus and treatment of diver Roderick Cameron following an injury that occurred on 14 October 1841 during the salvage operations.

In 1840, the use of controlled explosions to destroy the wreck continued through to September. on an occasion that year the Royal Engineers set off a huge controlled explosion which shattered windows as far away as Portsmouth and Gosport.

Meanwhile, Pasley had recovered 12 more guns in 1839, 11 more in 1840, and 6 in 1841. In 1842 he recovered only one iron 12-pounder, because he ordered the divers to concentrate on removing the hull timbers rather than search for guns. Other items recovered, in 1840, included the surgeon's brass instruments, silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the ...

garments of satin

A satin weave is a type of fabric weave that produces a characteristically glossy, smooth or lustrous material, typically with a glossy top surface and a dull back. It is one of three fundamental types of textile weaves alongside plain wea ...

weave "of which the silk was perfect", and pieces of leather; but no woollen clothing. By 1843 the whole of the keel and the bottom timbers had been raised and the site was declared clear.

Surviving timbers and guns

Royal Armouries

The Royal Armouries is the United Kingdom's national collection of arms and armour. Originally an important part of England's military organization, it became the United Kingdom's oldest museum, originally housed in the Tower of London from t ...

collection and on display at Southsea Castle

Southsea Castle, historically also known as Chaderton Castle, South Castle and Portsea Castle, is an artillery fort originally constructed by Henry VIII on Portsea Island, Hampshire, in 1544. It formed part of the King's Device programme to p ...

.

Several of the salvaged bronze cannon were melted down to form part of Nelson's Column

Nelson's Column is a monument in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, Central London, built to commemorate Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson's decisive victory at the Battle of Trafalgar over the combined French and Spanish navies, during whi ...

in London's Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson commem ...

. The Corinthian capital

The Corinthian order (Greek: Κορινθιακός ρυθμός, Latin: ''Ordo Corinthius'') is the last developed of the three principal classical orders of Ancient Greek architecture and Roman architecture. The other two are the Doric order w ...

is made of bronze elements, cast at the Woolwich Arsenal foundry. The bronze pieces, some weighing as much as are fixed to the column by the means of three large belts of metal lying in grooves in the stone.

Recovered materials were used to make a variety of souvenirs. In the 1850s, timber from the ship was used to make the

Recovered materials were used to make a variety of souvenirs. In the 1850s, timber from the ship was used to make the billiard table

A billiard table or billiards table is a bounded table on which cue sports are played. In the modern era, all billiards tables (whether for carom billiards, pool, pyramid or snooker) provide a flat surface usually made of quarried slate, ...

by J. Thurston & Co. for the North Wing of Burghley House

Burghley House () is a grand sixteenth-century English country house near Stamford, Lincolnshire. It is a leading example of the Elizabethan prodigy house, built and still lived in by the Cecil family. The exterior largely retains its Elizabet ...

. Wood salvaged from the ''Royal George'' was also used to make the coffin for the famous menagerie owner George Wombwell who died in 1850 and the covers of ''A Narrative of the loss of the Royal George, at Spithead, August, 1782; including Tracey’s Attempt to raise her in 1783, also Col Pasley’s Operations in Removing the Wreck, by Explosions of Gunpowder, in 1839-40'' by Colonel Pasley.

Notes

a. ''Royal George''s usual complement was 867.Citations

References

* * * * *Further reading

* *External links

*''Royal George''

fro

Loss of the Royal George at Spithead, 1782

Sinking of H.M.S. Royal George at Spithead Augt 29 1782

{{DEFAULTSORT:Royal George (1756) Ships of the line of the Royal Navy Shipwrecks in the Solent Military history of Hampshire Maritime incidents in 1782 1756 ships Ships built in Woolwich Archaeology of shipwrecks Maritime archaeology Underwater archaeology 1782 in Great Britain