HMS Resistance (1782) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

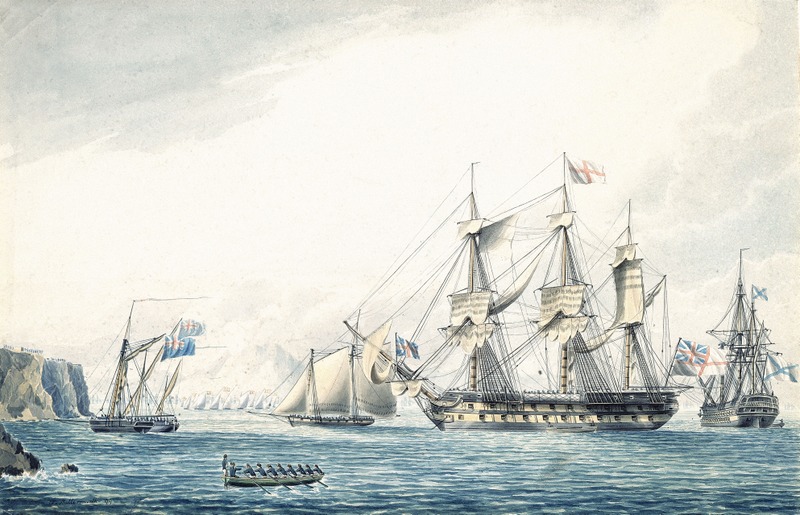

HMS ''Resistance'' was a 44-gun

When the

When the

''Resistance'' was first commissioned in March 1782 under the command of Captain James King. Having been fitted out, she sailed to Long Reach on 17 September where she took her armament and gun powder aboard. Preparations for service were completed on 29 September. She was sent to join the West Indies Station, sailing there from

''Resistance'' was first commissioned in March 1782 under the command of Captain James King. Having been fitted out, she sailed to Long Reach on 17 September where she took her armament and gun powder aboard. Preparations for service were completed on 29 September. She was sent to join the West Indies Station, sailing there from

fifth-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a fifth rate was the second-smallest class of warships in a hierarchical system of six " ratings" based on size and firepower.

Rating

The rating system in the Royal N ...

''Roebuck''-class ship of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

launched in 1782. Based on the design of HMS ''Roebuck'', the class was built for use off the coast of North America during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Commissioned by Captain James King, ''Resistance'' served on the West Indies Station for the rest of the war. She captured the 24-gun corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

''La Coquette'' on 2 March 1783 and then went on in the same day to participate in the unsuccessful Battle of Grand Turk

The Battle of Grand Turk was a battle that occurred on 9 March 1783 during the American Revolutionary War. France had seized the Turks and Caicos archipelago, islets of rich salt works, taking the island of Grand Turk in February 1783. The Britis ...

alongside Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

. ''Resistance'' then went for a refit

Refitting or refit of boats and marine vessels includes repairing, fixing, restoring, renewing, mending, and renovating an old vessel. Refitting has become one of the most important activities inside a shipyard. It offers a variety of services for ...

in Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

, during which time King fell ill and was replaced by Captain Edward O'Bryen

Rear-Admiral Edward O'Bryen (sometimes O'Brien) (1753 – 18 December 1808) was a British Royal Navy officer prominent in the late eighteenth century, who is best known for his participation at the Nore Mutiny and the Battle of Camperdown, both i ...

. O'Bryen commanded ''Resistance'' until March 1784 when she was paid off

Ship commissioning is the act or ceremony of placing a ship in active service and may be regarded as a particular application of the general concepts and practices of project commissioning. The term is most commonly applied to placing a warship in ...

. In 1791 she was recommissioned as a troop ship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

, but was converted back into a warship in 1793 at the start of the French Revolutionary War

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

, under Captain Edward Pakenham.

''Resistance'' was sent to serve on the East Indies Station

The East Indies Station was a formation and command of the British Royal Navy. Created in 1744 by the Admiralty, it was under the command of the Commander-in-Chief, East Indies.

Even in official documents, the term ''East Indies Station'' was ...

, where she was present at the capture of the 34-gun frigate ''Duguay Trouin'' on 5 May 1794. She then participated in the capture of Malacca

Malacca ( ms, Melaka) is a state in Malaysia located in the southern region of the Malay Peninsula, next to the Strait of Malacca. Its capital is Malacca City, dubbed the Historic City, which has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site si ...

on 17 August 1795. She was similarly part of the force that captured Amboyna Island on 16 February 1796, and Banda Neira

Banda Neira (also known as Pulau Neira) is an island in the Banda Islands, Indonesia. It is administered as part of the administrative Banda Islands District (''Kecamatan Kepulauan Banda'') within the Central Maluku Regency in the province of ...

on 8 March. Continuing the campaign to capture Dutch possessions in the East Indies, ''Resistance'' took Kupang

Kupang ( id, Kota Kupang, ), formerly known as Koepang, is the capital of the Indonesian province of East Nusa Tenggara. At the 2020 C ensus, it had a population of 442,758; the official estimate as at mid 2021 was 455,850. It is the largest ci ...

, Timor

Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is East Timor–Indonesia border, divided between the sovereign states of East Timor on the eastern part and Indonesia on the western p ...

, on 10 June 1797, but the native population rebelled against the new temporary governor. Pakenham fired on the town and then sent a landing party in to regain control, destroying most of Kupang in the process.

On 21 July 1798 ''Resistance'' cut out a Malay

Malay may refer to:

Languages

* Malay language or Bahasa Melayu, a major Austronesian language spoken in Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei and Singapore

** History of the Malay language, the Malay language from the 4th to the 14th century

** Indonesi ...

merchant sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

, and after ascertaining the legal ownership of the vessel, sailed to Bangka Strait

Bangka Strait is the strait that separates the island of Sumatra from Bangka Island ( id, Pulau Bangka) in the Java Sea, Indonesia. The strait is about long, with a width varying from about to .

See also

* Japanese cruiser Ashigara

* List of st ...

to return her to her captain. Arriving on 23 July, she anchored in the evening. At 1 a.m. on 24 July she suddenly caught fire and exploded, killing 332 people. Of the thirteen survivors, only four successfully reached Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

on a makeshift raft. Enslaved by local pirates, they were eventually rescued by the Sultan of Lingga.

Design and construction

''Resistance'' was a 44-gun,18-pounder

The Ordnance QF 18-pounder,British military traditionally denoted smaller ordnance by the weight of its standard projectile, in this case approximately or simply 18-pounder gun, was the standard British Empire field gun of the First World War ...

. The class was a revival of the design used to construct the fifth-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a fifth rate was the second-smallest class of warships in a hierarchical system of six " ratings" based on size and firepower.

Rating

The rating system in the Royal N ...

HMS ''Roebuck'' in 1769, by Sir Thomas Slade

Sir Thomas Slade (1703/4–1771) was an English naval architect, most famous for designing HMS ''Victory'', Lord Nelson's flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

Early life

He was the son of Arthur Slade (1682–1746) and his wife Hannah ...

. The ships, while classified as fifth-rates, were not frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

s because they carried two gun decks, of which a frigate would have only one. ''Roebuck'' was designed as such to provide the extra firepower a ship of two decks could bring to warfare but with a much lower draught and smaller profile. From 1751 to 1776 only two ships of this type were built for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

because it was felt that they were anachronistic, with the lower (and more heavily armed) deck of guns being so low as to be unusable in anything but the calmest of waters. In the 1750s the cruising role of the 44-gun two deck ship was taken over by new 32- and 36-gun frigates, leaving the type almost completely obsolete.

When the

When the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

began in 1776 a need was found for heavily armed ships that could fight in the shallow coastal waters of North America, where two-decked third-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the third r ...

s could not safely sail, and so the ''Roebuck'' class of nineteen ships, alongside the similar ''Adventure'' class, was ordered to the specifications of the original ships to fill this need. The frigate classes that had overtaken the 44-gun ship as the preferred design for cruisers were at this point still mostly armed with 9- and 12-pounder guns, and it was expected that the class's heavier 18-pounders would provide them with an advantage over these vessels. Frigates with larger armaments would go on to be built by the Royal Navy later on in the American Revolutionary Wars, but these ships were highly expensive and so ''Resistance'' and her brethren continued to be built as a cheaper alternative.

While most of ''Roebuck''s design was carried over to the new ships, some aspects were changed to reflect the changes in technology that had occurred in the passing years. ''Roebuck'' and the ships of the class ordered before 1782 were armed with twenty-two 9-pounder guns on their upper decks, but in that year the class was rearmed with more powerful 12-pounders, the same year ''Resistance'' was launched. As well as this change in armament, all ships laid down after the first four of the class had the double level of stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Ori ...

windows removed and replaced with a single level of windows, moving the style of the ships closer to that of a true frigate.

All but one ship of the class was contracted out to civilian dockyards for construction, and the contract for ''Resistance'' was given to Edward Greaves at Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains throug ...

. She was ordered on 29 March 1780, laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

in April 1781 and launched on 11 July 1782 with the following dimensions: along the gun deck

The term gun deck used to refer to a deck aboard a ship that was primarily used for the mounting of cannon to be fired in broadsides. The term is generally applied to decks enclosed under a roof; smaller and unrated vessels carried their guns o ...

, at the keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

, with a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of and a depth in the hold

Hold may refer to:

Physical spaces

* Hold (ship), interior cargo space

* Baggage hold, cargo space on an airplane

* Stronghold, a castle or other fortified place

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Hold (musical term), a pause, also called a Fermat ...

of . Her draught, which made the class so valued in the American Revolutionary War, was . She measured 894 tons burthen

Builder's Old Measurement (BOM, bm, OM, and o.m.) is the method used in England from approximately 1650 to 1849 for calculating the cargo capacity of a ship. It is a volumetric measurement of cubic capacity. It estimated the tonnage of a ship bas ...

. The fitting out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

process for ''Resistance'' was completed, including the addition of her copper sheathing

Copper sheathing is the practice of protecting the under-water hull of a ship or boat from the corrosive effects of salt water and biofouling through the use of copper plates affixed to the outside of the hull. It was pioneered and developed by ...

, on 17 August at Deptford Dockyard

Deptford Dockyard was an important naval dockyard and base at Deptford on the River Thames, operated by the Royal Navy from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. It built and maintained warships for 350 years, and many significant events a ...

.

Service

American Revolutionary War

''Resistance'' was first commissioned in March 1782 under the command of Captain James King. Having been fitted out, she sailed to Long Reach on 17 September where she took her armament and gun powder aboard. Preparations for service were completed on 29 September. She was sent to join the West Indies Station, sailing there from

''Resistance'' was first commissioned in March 1782 under the command of Captain James King. Having been fitted out, she sailed to Long Reach on 17 September where she took her armament and gun powder aboard. Preparations for service were completed on 29 September. She was sent to join the West Indies Station, sailing there from Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

in control of a convoy of 500 merchant ships on 11 November, the responsibility and stress of which turned King's hair grey. They arrived at Carlisle Bay, Barbados

Carlisle Bay is a small natural harbour located in the southwest region of Barbados. The island nation's capital, Bridgetown, is situated on this bay which has been turned into a marine park. Carlisle Bay's marine park is a popular spot on the ...

, on 12 December. ''Resistance'' then went patrolling off Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

with the 18-gun sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

HMS ''Duguay Trouin''; on 9 February 1783 they encountered a squadron consisting of a ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

, two frigates, and a sloop, one of which flew a French flag, however upon investigation it was found that the squadron was a British one with a French prize

A prize is an award to be given to a person or a group of people (such as sporting teams and organizations) to recognize and reward their actions and achievements.

. ''Resistance'' captured her first prize on 16 February when she caught the American merchantman ''Fox'' as the latter attempted to sail to Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

.

''Resistance'' continued in company with ''Duguay Trouin'', and on 2 March they were sailing through Turk's Island passage when they discovered two French warships at anchor there. The enemy vessels made to escape from the British ships, but as the rearmost ship began to sail away, she lost her mainmast

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the centre-line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, and giving necessary height to a navigation ligh ...

. This ship was a 20-gun vessel, and ''Resistance'' soon came up with the stationary vessel and fired a broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

from her upper deck guns into her before moving on in chase of the other French ship, the 24-gun corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

''La Coquette''. The chase went on for fifteen minutes before ''Resistance'' managed to sail to leeward

Windward () and leeward () are terms used to describe the direction of the wind. Windward is ''upwind'' from the point of reference, i.e. towards the direction from which the wind is coming; leeward is ''downwind'' from the point of reference ...

of ''La Coquette'', at which point the French warship surrendered. King put ''La Coquette'' under the command of Lieutenant James Trevenen and continued on his patrol. On 6 March the ships captured a Danish brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the ...

and on 8 March they captured two more merchant vessels, including the American ship ''Hope'', all of which were sent to Port Royal

Port Royal is a village located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest city in the Caribbean, functioning as the centre of shipping and co ...

.

''La Coquette'' had been part of a French squadron that had captured the island of Grand Turk on 12 February, and later on 6 March ''Resistance'' and her consorts met near there with the 26-gun frigate HMS ''Albemarle'' and 14-gun brig-sloop

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

HMS ''Drake''. ''Albemarle'' was commanded by Captain Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

, who was senior to King and took command of the group. Nelson decided to attempt to take back Grand Turk from the French, and early on 8 March a landing was made by a group of 250 seamen and marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

under the cover of the guns of two brigs also attached to the squadron. The ships were fired upon by a 3-gun battery

In military organizations, an artillery battery is a unit or multiple systems of artillery, mortar systems, rocket artillery, multiple rocket launchers, surface-to-surface missiles, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, etc., so grouped to faci ...

as they closed in on the land, and the French garrison met the landing party as it arrived, attacking it with more cannon. The Battle of Grand Turk

The Battle of Grand Turk was a battle that occurred on 9 March 1783 during the American Revolutionary War. France had seized the Turks and Caicos archipelago, islets of rich salt works, taking the island of Grand Turk in February 1783. The Britis ...

was unsuccessful and the landing party was forced to return to their ships, the island untaken. On the following night it was decided that another attack would be made, this time with the larger ships of the squadron attacking the gun batteries first. Before this plan could be put into action the wind changed and made it impossible for the ships to stay on station, and the attempt was abandoned. After stopping at Jamaica on 13 March, ''Resistance'' sailed to Port Royal with ''Albemarle'' the next day to undergo a three-month refit, during which time King lived ashore.

King's health started to rapidly deteriorate, and at one point he went six weeks without stepping onboard ''Resistance'' because of this. He resigned command of the ship on 14 June. On 6 August King's replacement, Captain Edward O'Bryen

Rear-Admiral Edward O'Bryen (sometimes O'Brien) (1753 – 18 December 1808) was a British Royal Navy officer prominent in the late eighteenth century, who is best known for his participation at the Nore Mutiny and the Battle of Camperdown, both i ...

, took command of ''Resistance''; O'Bryen commanded ''Resistance'' into 1784 before sailing her to England to be paid off

Ship commissioning is the act or ceremony of placing a ship in active service and may be regarded as a particular application of the general concepts and practices of project commissioning. The term is most commonly applied to placing a warship in ...

in March of that year. She received a repair at Portsmouth Dockyard

His Majesty's Naval Base, Portsmouth (HMNB Portsmouth) is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Clyde and HMNB Devonport). Portsmouth Naval Base is part of the city of Portsmouth; it is l ...

between July and December 1785 at the cost of £6,945, but was not immediately put back into service, the American Revolutionary War having ended.

Troop ship

With the wartime necessity of using the obsolete ships as frontline warships now at an end, most ships of ''Resistance''s type were taken out of service. While lacking modern fighting capabilities, the design still provided a fast ship, and so theComptroller of the Navy

The post of Controller of the Navy (abbreviated as CofN) was originally created in 1859 when the Surveyor of the Navy's title changed to Controller of the Navy. In 1869 the controller's office was abolished and its duties were assumed by that of ...

, Sir Charles Middleton

Admiral Charles Middleton, 1st Baron Barham, PC (14 October 172617 June 1813) was a Royal Navy officer and politician. As a junior officer he saw action during the Seven Years' War. Middleton was given command of a guardship at the Nore, a R ...

, pressed them into service as troop ship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

s. ''Resistance'' was recommissioned as such in February 1791 under the command of Commander John O'Bryen, still at this point situated at Portsmouth. She was fitted out for her new role between March and April, and sailed with soldiers for Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

on 2 May. Despite being reconfigured to carry men and supplies, ''Resistance'' was still recorded as a warship and was armed en flute

En or EN may refer to:

Businesses

* Bouygues (stock symbol EN)

* Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway (reporting mark EN, but now known as Southern Railway of Vancouver Island)

* Euronews, a news television and internet channel

Language and writing

* ...

at this time, with twenty 9-pounders and four 6-pounders. On 27 May she left Gibraltar to convey a force including Prince Edward and his mistress

Mistress is the feminine form of the English word "master" (''master'' + ''-ess'') and may refer to:

Romance and relationships

* Mistress (lover), a term for a woman who is in a sexual and romantic relationship with a man who is married to a d ...

Madame de Saint-Laurent to Canada, arriving in the St Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

on 11 August.

''Resistance'' was subsequently recommissioned as a warship at Portsmouth in June 1793 under Captain Edward Pakenham. The Royal Navy had built twenty-seven 44-gun two-decked ships for the American Revolutionary War, but with the war having ended before most had seen much service, they were some of the newest and best condition ships available to the navy. With the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

having begun, ''Resistance'' was pushed quickly into service to fill the gap left by a lack of available 18-pounder frigates, despite her class by this point being completely unsuited to the task. She stayed at Portsmouth between July and August to be refitted and subsequently sailed to join the East Indies Station

The East Indies Station was a formation and command of the British Royal Navy. Created in 1744 by the Admiralty, it was under the command of the Commander-in-Chief, East Indies.

Even in official documents, the term ''East Indies Station'' was ...

on 28 November.

French Revolutionary War

By February 1794 ''Resistance'' was cruising off theCape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

with the 50-gun fourth rate

In 1603 all English warships with a compliment of fewer than 160 men were known as 'small ships'. In 1625/26 to establish pay rates for officers a six tier naval ship rating system was introduced.Winfield 2009 These small ships were divided i ...

HMS ''Centurion'' and 32-gun frigate HMS ''Orpheus''. There they rendezvoused with the 74-gun ship of the line HMS ''Suffolk'', the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

of Commodore Peter Rainier and joined him in sailing to the East Indies as escort to a large convoy. By 5 May ''Resistance'' had reached the station, patrolling with ''Centurion'' and ''Orpheus''. Pakenham spotted two ships off Round Island near Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label=Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It incl ...

; ''Orpheus'' was the closest vessel and she chased the pair, coming up with one of them at 11:35 a.m. This enemy was the French 34-gun frigate ''Duguay Trouin'', and ''Orpheus'' engaged her until 1:30 p.m. when ''Resistance'' and ''Centurion'' finally began to close in, being slower, at which point ''Duguay Trouin'' surrendered. ''Resistance'' then captured the 18-gun ship ''Revanche'' in the Sunda Strait

The Sunda Strait ( id, Selat Sunda) is the strait between the Indonesian islands of Java island, Java and Sumatra. It connects the Java Sea with the Indian Ocean.

Etymology

The strait takes its name from the Sunda Kingdom, which ruled the weste ...

in October.

''Resistance'' was sent to Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second- ...

in January 1795 as escort to a convoy, where she re-provisioned herself and sailed on trade prevention duties. In March she then joined with Rainier in ''Suffolk'' to protect a convoy through the Strait of Malacca

The Strait of Malacca is a narrow stretch of water, 500 mi (800 km) long and from 40 to 155 mi (65–250 km) wide, between the Malay Peninsula (Peninsular Malaysia) to the northeast and the Indonesian island of Sumatra to the southwest, connec ...

as it returned from China. Having completed this task, ''Resistance'' was detached from Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

on 21 July so that she could take a troop ship and a transport to join the invasion expedition for Malacca

Malacca ( ms, Melaka) is a state in Malaysia located in the southern region of the Malay Peninsula, next to the Strait of Malacca. Its capital is Malacca City, dubbed the Historic City, which has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site si ...

, which had already sailed under Captain Henry Newcome of ''Orpheus''. ''Resistance'' reached the expedition by 13 August but then left it again, returning on 17 August, two days after the main force had reached Malacca. The expedition launched the attack only after ''Resistance''s return, with her employed in attacking the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

ship ''Constantia'' which had been beached just inside the port. After a token period of defence ''Constantia'' quickly surrendered. At 7 p.m. Newcome landed the troops the expedition had conveyed with them, who reached the shore at 9 p.m.; half an hour later a representative of Malacca came onboard ''Orpheus'' and surrendered, with little violence having occurred. Around the same time as this occupation took place, another expedition captured Trincomalee

Trincomalee (; ta, திருகோணமலை, translit=Tirukōṇamalai; si, ත්රිකුණාමළය, translit= Trikuṇāmaḷaya), also known as Gokanna and Gokarna, is the administrative headquarters of the Trincomalee Dis ...

. These were the first in a string of island captures by the Royal Navy; ''Resistance'' left Malacca on 6 January 1796 as part of an invasion force led by the now-Rear-Admiral Rainier, and on 16 February they arrived off Amboyna Island, which surrendered immediately. The force left Amboyna on 5 March and sailed to Banda Neira

Banda Neira (also known as Pulau Neira) is an island in the Banda Islands, Indonesia. It is administered as part of the administrative Banda Islands District (''Kecamatan Kepulauan Banda'') within the Central Maluku Regency in the province of ...

, arriving there on 7 March. Early in the afternoon of 8 March a landing party captured the island after a short defence by the Dutch garrison forces there.

By the end of the year Rainier's naval resources were being stretched thin by demands from the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

and to cover his newly captured possessions he left behind ''Resistance'' and three sloops on 8 December, as he manoeuvred to concentrate on protecting trade from Macao

Macau or Macao (; ; ; ), officially the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (MSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China in the western Pearl River Delta by the South China Sea. With a pop ...

. ''Resistance'' mostly cruised off Timor

Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is East Timor–Indonesia border, divided between the sovereign states of East Timor on the eastern part and Indonesia on the western p ...

and the Maluku Islands

The Maluku Islands (; Indonesian: ''Kepulauan Maluku'') or the Moluccas () are an archipelago in the east of Indonesia. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located eas ...

to accomplish this goal, but Pakenham had also been ordered to use his force to capture Timor and any other settlements when the opportunity arose. On 17 February 1797 ''Resistance'' arrived at Ternate

Ternate is a city in the Indonesian province of North Maluku and an island in the Maluku Islands. It was the ''de facto'' provincial capital of North Maluku before Sofifi on the nearby coast of Halmahera became the capital in 2010. It is off the we ...

alongside the Bombay Marine

The Royal Indian Navy (RIN) was the naval force of British India and the Dominion of India. Along with the Presidency armies, later the Indian Army, and from 1932 the Royal Indian Air Force, it was one of the Armed Forces of British India.

Fr ...

's

38-gun frigate HCS ''Bombay'', and the 10-gun brig HMS ''Amboyna''. Pakenham presented the Dutch governor of the city with a demand for a peaceful surrender, promising that the freedoms and properties of the population would not be harmed if he agreed. After a period of confusion because nobody there spoke English, the request was declined and the Dutch prepared to defend the city, but ''Resistance'' and her consorts sailed away and instead peacefully took the town of Manado

Manado () is the capital City status in Indonesia, city of the Indonesian Provinces of Indonesia, province of North Sulawesi. It is the second largest city in Sulawesi after Makassar, with the 2020 Census giving a population of 451,916 distribu ...

.

On 10 June, cooperating with the 16-gun snow

Snow comprises individual ice crystals that grow while suspended in the atmosphere—usually within clouds—and then fall, accumulating on the ground where they undergo further changes.

It consists of frozen crystalline water throughout ...

HCS ''Intrepid'', ''Resistance'' secured the primary Dutch settlement on Timor, Kupang

Kupang ( id, Kota Kupang, ), formerly known as Koepang, is the capital of the Indonesian province of East Nusa Tenggara. At the 2020 C ensus, it had a population of 442,758; the official estimate as at mid 2021 was 455,850. It is the largest ci ...

, after the officials there voted to surrender. A temporary governor was appointed from the East India Company and sent ashore under the guard of a group of sepoy

''Sepoy'' () was the Persian-derived designation originally given to a professional Indian infantryman, traditionally armed with a musket, in the armies of the Mughal Empire.

In the 18th century, the French East India Company and its oth ...

s and marines. The local population were then either persuaded or commanded by some of the Dutch residents to attack this new garrison, with the signal being Pakenham's expected arrival on shore. At the last moment Pakenham decided against visiting the governor but he still sent his boat, and on its arrival the natives attacked, killing sixteen people. In revenge for this Pakenham had ''Resistance'' fire on the settlement, and under cover of this fire he sent a strong landing party to attack, the combination of which killed around 200 of the natives and forced the rest to flee. The town was almost completely destroyed; the European, mostly Dutch, part of the population had escaped at the first sign of violence, and Pakenham chose to abandon Kupang. On 7 September Pakenham reported to Rainier that ''Resistance'' was hardly seaworthy, such was the poor state of her masts and rigging

Rigging comprises the system of ropes, cables and chains, which support a sailing ship or sail boat's masts—''standing rigging'', including shrouds and stays—and which adjust the position of the vessel's sails and spars to which they are ...

.

Despite this ''Resistance'' continued in her duties, and in October she had a successful month of prizetaking against the Dutch; the 10-gun sloop ''Yonge Frans'' was cut out from Ternate, while the 4-gun sloop ''Juno'' was captured as she attempted to enter that port. Off Limbi Island the 10-gun sloop ''Yonge Lansier'' was captured, and then the 6-gun ketch

A ketch is a two- masted sailboat whose mainmast is taller than the mizzen mast (or aft-mast), and whose mizzen mast is stepped forward of the rudder post. The mizzen mast stepped forward of the rudder post is what distinguishes the ketch fr ...

''Limbi'' was taken at Celebes

Sulawesi (), also known as Celebes (), is an island in Indonesia. One of the four Greater Sunda Islands, and the world's eleventh-largest island, it is situated east of Borneo, west of the Maluku Islands, and south of Mindanao and the Sulu A ...

. ''Resistance''s boats then captured the 10-gun sloop ''Waaker'' at Gonontalo Island off Celebes, with ''Resistance'' herself capturing the 6-gun brig ''Resource'' off Kupang. Also taken in this period was the 4-gun brig ''Ternate'' and several large, but unnamed, local trading vessels.

Towards the end of December ''Resistance'' sailed through a storm for four days and began to leak badly, to the extent that several of her guns were thrown overboard to increase buoyancy. She sailed for the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

and arrived off the fortified port of Antego, Panay

Panay is the sixth-largest and fourth-most populous island in the Philippines, with a total land area of and has a total population of 4,542,926 as of 2020 census. Panay comprises 4.4 percent of the entire population of the country. The City o ...

, flying a false Spanish flag on 24 December. Seeing this supposedly friendly ship, the deputy governor of the town and the captain of a Spanish brig that was sheltering there both took boats out to ''Resistance'', where they were detained. The men agreed to provide Pakenham with food, water, and wood, and in return he had them released. The men reneged on their promise, and so at 5 p.m. on 25 December a party from ''Resistance'' cut out the Spanish brig from the bay.

The brig was quickly taken out of range of the gun batteries on land, and the two ships then sailed for Balambangan Island

Balambangan Island ( ms, Pulau Balambangan) is an island in Kudat Division, Sabah, Malaysia. It is located off the northern tip of Borneo and is situated just about 3 kilometres west of Banggi Island. It is now part of the Tun Mustapha Marine ...

, arriving there on 29 December. From here ''Resistance'' sailed to Celebes from where the brig was sent to Amboyna with a request for provisions to be sent out to the ship so that she could continue on. ''Bombay'' met with ''Resistance'' off Booloo, one of the Riau Islands

The Riau Islands ( id, Kepulauan Riau) is a province of Indonesia. It comprises a total of 1,796 islands scattered between Sumatra, Malay Peninsula, and Borneo including the Riau Archipelago. Situated on one of the world's busiest shipping la ...

, towards the end of January 1798 and finally managed to adequately provision the ship. ''Resistance'' then sailed to Amboyna, where she spent two months in a refit. Having made one aborted attempt to leave Amboyna that was stopped by a sudden leak, the ship left the island in July. On 20 July ''Resistance'' encountered a pirate fleet off Bangka Island

Bangka is an island lying east of Sumatra, Indonesia. It is administered under the province of the Bangka Belitung Islands, being one of its namesakes alongside the smaller island of Belitung across the Gaspar Strait. The 9th largest island in In ...

and attempted to board some of the vessels to search them, but the pirates refused to let their parties do so. Pakenham had ''Resistance'' fire at the pirates afterwards, and thus forced them to disperse.

In the morning of 21 July ''Resistance'' cut out a Malay

Malay may refer to:

Languages

* Malay language or Bahasa Melayu, a major Austronesian language spoken in Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei and Singapore

** History of the Malay language, the Malay language from the 4th to the 14th century

** Indonesi ...

merchant sloop that had been earlier captured by the pirates, and Pakenham took it with him as they attempted to discover the true ownership of the vessel, with the captain kept on board to ensure that his ship would stay sailing with them. The sloop soon fell behind ''Resistance'', in which time it had been decided that the sloop's captain was her rightful owner and that he should be restored to her as soon as possible.

Fate

''Resistance'' anchored inBangka Strait

Bangka Strait is the strait that separates the island of Sumatra from Bangka Island ( id, Pulau Bangka) in the Java Sea, Indonesia. The strait is about long, with a width varying from about to .

See also

* Japanese cruiser Ashigara

* List of st ...

on the evening of 23 July, with the sloop arriving at 1 a.m. the next day. The two ships settled to wait for the morning when the transfer of the captain could take place, but at around 4 a.m. ''Resistance'' suddenly set on fire and exploded. No cause of the incident has been concluded, but some reports suggest that it was caused by a lightning strike

A lightning strike or lightning bolt is an electric discharge between the atmosphere and the ground. Most originate in a cumulonimbus cloud and terminate on the ground, called cloud-to-ground (CG) lightning. A less common type of strike, ground- ...

that travelled down the foremast

The mast of a Sailing ship, sailing vessel is a tall spar (sailing), spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the centre-line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, and giving necessa ...

and into the magazine

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combinatio ...

. 332 people were killed in the explosion, while thirteen survived. Among the dead were all the ship's officers, three English wives of crewmen, a woman from Amboyna, and fourteen Spanish prisoners.

''Resistance'' settled on the seabed with her starboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms for watercraft and aircraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the bow (front).

Vessels with bilateral symmetry have left and right halves which are ...

hammock netting just above the waterline, which the survivors held on to until the morning. At dawn the sloop, under the control of its native crew, sailed away without offering assistance. The survivors, led by a quartermaster

Quartermaster is a military term, the meaning of which depends on the country and service. In land armies, a quartermaster is generally a relatively senior soldier who supervises stores or barracks and distributes supplies and provisions. In m ...

, constructed a raft using ''Resistance''s main yard

The yard (symbol: yd) is an English unit of length in both the British imperial and US customary systems of measurement equalling 3 feet or 36 inches. Since 1959 it has been by international agreement standardized as exactly 0.914 ...

and its rigging and attempted to sail to Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

at 1 p.m.; they continued until 7 p.m. when the raft began to break apart. Four men lashed together a piece of the raft with two spars

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) Women's Reserve, also known as the SPARS (SPARS was the acronym for "Semper Paratus—Always Ready"), was the women's branch of the United States Coast Guard Reserve. It was established by the United States ...

while the others continued with the main raft. The four successfully reached the north coast of Sumatra at 9 p.m. on 25 July, but the others of their party were not seen again.

The survivors walked along the coast to search for assistance, and at 4 p.m. on 26 July they discovered a fleet of Malay pirates who had five of their proa

Proas are various types of multi-hull outrigger sailboats of the Austronesian peoples. The terms were used for native Austronesian ships in European records during the Colonial era indiscriminately, and thus can confusingly refer to the do ...

s near the shore. The pirates took the men in because one of the survivors, Thomas Scott, spoke their language and begged for his life. The pirates brought them onboard their boats and the British men served them for a while before it was decided that they would be sold into slavery. By this point Major Taylor, the officer commanding the British garrison at Malacca, had been made aware of the fate of ''Resistance'', and asked the Sultan of Lingga to assist in recovering the survivors. The Sultan quickly succeeded in retrieving the first three men; Alexander M'Carthy (the quartermaster) and John Hutton were given freely to him by the master of the proa they were working in; then Joseph Scott was sold for fifteen rixdollar Rixdollar is the English term for silver coinage used throughout the European continent (german: Reichsthaler, nl, rijksdaalder, da, rigsdaler, sv, riksdaler).

The same term was also used of currency in Cape Colony and Ceylon. However, the Rix ...

s by the Timor-men who held him.

Believing the three to be the only survivors, the Sultan had them sent in a proa to Penang

Penang ( ms, Pulau Pinang, is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, by the Malacca Strait. It has two parts: Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai on the Malay ...

. The final survivor, Thomas Scott, had been kept on board the boat controlled by the leader of the pirates, but was brought to Lingga nine days later where he was sold at the market for thirty-five rixdollars. Scott's new owner offered to release him if he could pay him back the price of his purchase, but on the following day the Sultan retrieved him. Scott was sent to Malacca on 5 December, and eventually returned to England in the 28-gun frigate , doing so on 5 October 1799.

Prizes

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Resistance (1782) 1782 ships Fifth-rate frigates of the Royal Navy Maritime incidents in 1798