George Bowen (colonial Settler) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lieutenant George Meares Countess Bowen (1803–1889) was a military officer and colonial settler of New South Wales, Australia. He was mainly associated with Bowen Mountain,

Although most of the high parts of the Blue Mountains are sandstone country and relatively infertile, Mt Tomah and the surrounding area has deep, rich, volcanic soil. Bowen probably first encountered the area himself, while surveying the boundaries of the new County of Cook.

Bowen's mother, Susannah, came out to New South Wales in 1827. In 1830, she requested from Darling, and received, a land grant of two square miles around the summit of

Although most of the high parts of the Blue Mountains are sandstone country and relatively infertile, Mt Tomah and the surrounding area has deep, rich, volcanic soil. Bowen probably first encountered the area himself, while surveying the boundaries of the new County of Cook.

Bowen's mother, Susannah, came out to New South Wales in 1827. In 1830, she requested from Darling, and received, a land grant of two square miles around the summit of

Australian Dictionary of Biography: Bowen, George Meares Countess

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bowen, George Settlers of New South Wales 1803 births 1889 deaths

Mount Tomah

Mount Tomah is a locality and a mountain that is located in the Blue Mountains region of the state of New South Wales, Australia. The locality is known for the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden on the Bells Line of Road.

Description

The villa ...

, Berambing

Berambing is a rural locality in the Blue Mountains (New South Wales), Blue Mountains of New South Wales, Australia. The settlement is clustered around the Bells Line of Road, between Windsor, New South Wales, Windsor and Lithgow, New South Wale ...

, and the nearby areas of the Blue Mountains.

Early life

He was born on 14 January 1803, atWells

Wells most commonly refers to:

* Wells, Somerset, a cathedral city in Somerset, England

* Well, an excavation or structure created in the ground

* Wells (name)

Wells may also refer to:

Places Canada

*Wells, British Columbia

England

* Wells ...

, in Somerset, England. His parents were Captain William Henry Hawkwell Bowen, R.N., who died in 1813, and his wife Susannah (née Parker, died 1840). His maternal grandfather was Admiral Sir William Parker, 1st Baronet, of Harburn

Admiral Sir William Parker, 1st Baronet (1 January 1743 – 31 October 1802), was a British naval commander.

Naval career

William Parker's father, Augustine Parker, had been mayor of Queenborough, Isle of Sheppey, Kent and a commander of one o ...

(1743—1803). His unusual second middle name, Countess, is after George Countess, a naval colleague and friend of his father. Bowen became an army officer, not a naval officer like his ancestors.

New South Wales

Leaving England in October 1826, he arrived in Sydney in February 1827, on the ''Midas'', leading a detachment of the 39th regiment, guarding convicts. Also arriving was Bowen's superior officer, Captain Charles Sturt, with another detachment of the 39th and more convicts, aboard ''Mariner''. Bowen arrived in New South Wales, during the administration of Governor Ralph Darling. Darling had been appointed with the objective of restoring discipline to the penal colony, after what was seen by the British government of the time as the relatively lax rule ofGovernor Macquarie

Major General Lachlan Macquarie, CB (; gd, Lachann MacGuaire; 31 January 1762 – 1 July 1824) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator from Scotland. Macquarie served as the fifth Governor of New South Wales from 1810 to 1821, an ...

and Governor Brisbane. Darling tended to rely upon like-minded military men for his administration. The well-connected Lieutenant Bowen, a Sandhurst graduate, found Darling a willing patron. Bowen was soon appointed to the Surveyor-General's office, serving as an Assistant Surveyor and a Commissioner for Lands. From 1 November 1828, he went on half-pay, effectively retiring from his regiment. His retiring allowed Bowen to be granted land in the colony, something not permitted to serving military officers.

Surveyor

in 1827, Bowen was part of Hamilton Hume's expedition in Blue Mountains, searching for alternative routes, avoiding the steep descent atMount York

Mount York, a mountain in the western region of the Explorer Range, part of the Blue Mountains Range that is a spur off the Great Dividing Range, is located approximately west of Sydney, just outside Mount Victoria in New South Wales, Austr ...

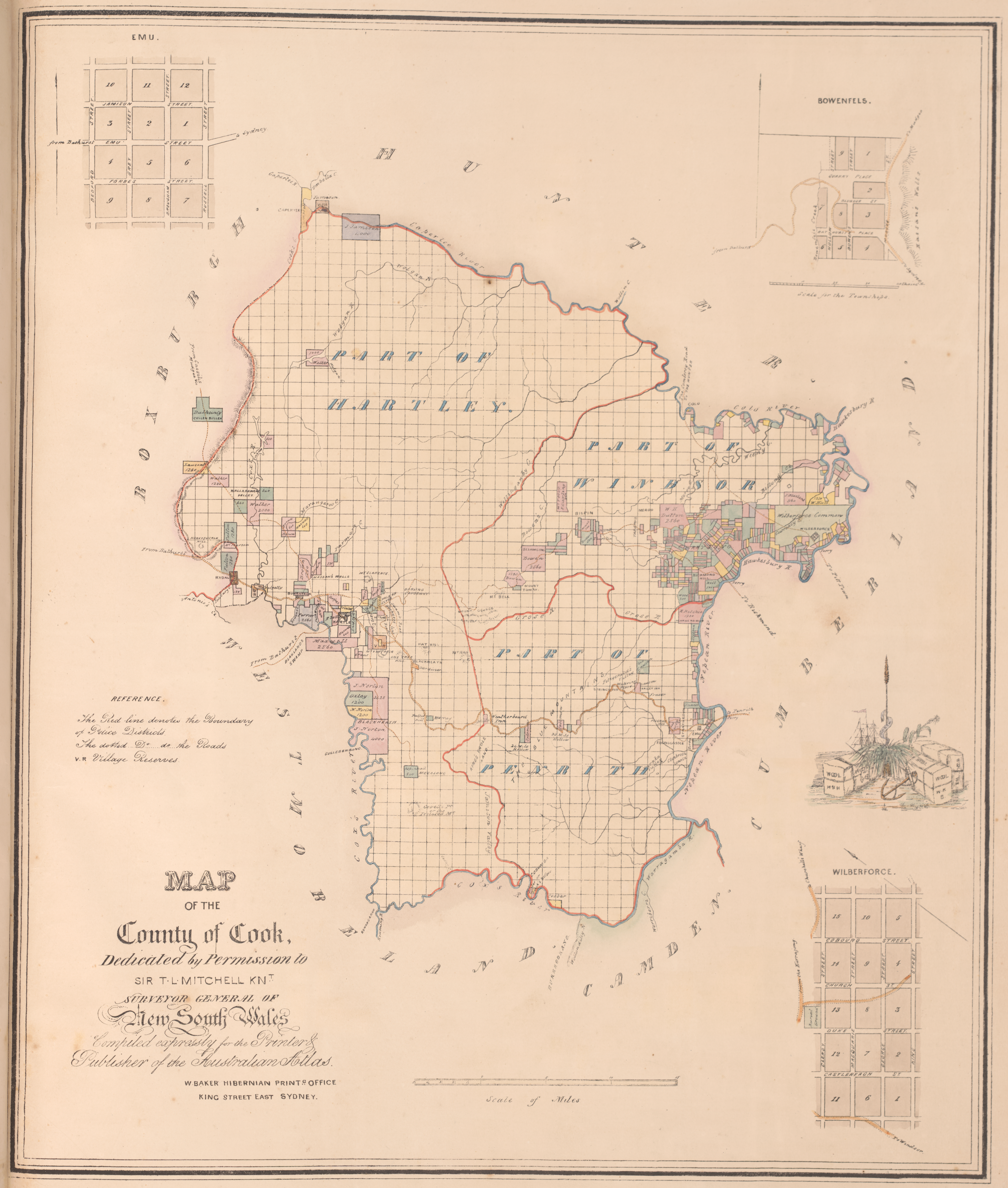

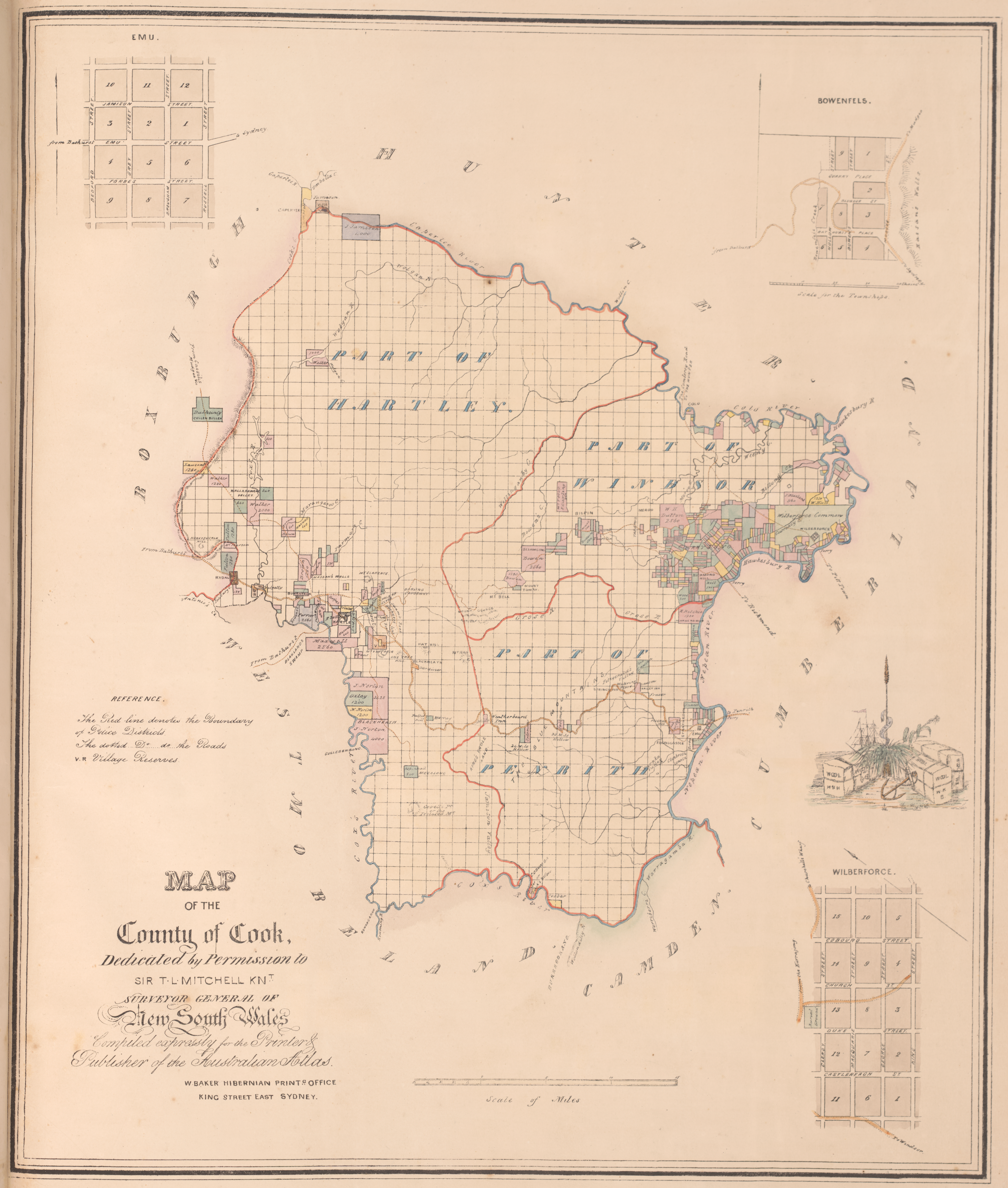

, via which to descend the western escarpment of the Blue Mountains. He surveyed the boundaries of the County of Cook, one of the Nineteen Counties

The Nineteen Counties were the limits of location in the colony of New South Wales, Australia. Settlers were permitted to take up land only within the counties due to the dangers in the wilderness.

They were defined by the Governor of New Sout ...

, within which the colonial government allowed settlers to take up land under Governor Darling's order of 1829.

He developed a warm relationship with the Surveyor-General John Oxley

John Joseph William Molesworth Oxley (1784 – 25 May 1828)

was an explorer and surveyor of Australia in the early period of British colonisation. He served as Surveyor General of New South Wales and is perhaps best known for his two exp ...

, but less so with the new Deputy Surveyor-General Thomas Mitchell, who arrived in Sydney in 1827 and who later became Surveyor-General

A surveyor general is an official responsible for government surveying in a specific country or territory. Historically, this would often have been a military appointment, but it is now more likely to be a civilian post.

The following surveyor gen ...

after Oxley's death in May 1828. It seems that Mitchell was resentful of Governor Darling and any of those who had been favoured by Darling, such as Oxley, Bowen, Darling's brothers-in-law, Henry Dumaresq (Darling's private secretary) and William Dumaresq

William John Dumaresq (25 February 1793 – 9 November 1868) was an English-born military officer, civil engineer, landholder and early Australian politician. He is associated with settler colonisation of the areas around Scone and Armidale ...

(Acting Deputy Surveyor-General under Oxley), and Charles Sturt

Charles Napier Sturt (28 April 1795 – 16 June 1869) was a British officer and explorer of Australia, and part of the European exploration of Australia. He led several expeditions into the interior of the continent, starting from Sydney and la ...

(Darling's military secretary and a cousin of Henry Dumaresq's wife).

In September 1823, Archibald Bell Jr. had identified arable land along the route that became the Bells Line of Road

Bells Line of Road is a major road located in New South Wales, Australia, providing an alternative crossing of the Blue Mountains to the Great Western Highway. The eastern terminus of the road is in , 51 km northwest of Sydney, where the road ...

, a second route across the hitherto impassable Blue Mountains. Bell had noticed that there was apparently a route across the mountains that was known to some, but not all, of the local Aboriginal peoples. Oxley sent Robert Hoddle

Robert Hoddle (21 April 1794 – 24 October 1881)

was a surveyor and artist. He is best known as the surveyor general of the Port Phillip District (later known as the Australian state of Victoria) from 1837 to 1853, especially for creation of ...

to survey the route. Hoddle wrote a report, in November 1823, that praised the rich soil around Mt Tomah and concluded that Bell's route was a superior way to reach Bathurst. Based on Hoddle's report, Bowen made a request to Thomas Mitchell to have a road developed along Bell's route. Mitchell was strongly committed to his own preferred route for the Bathurst Road, using the Victoria Pass, and sent a scathing report to Governor Darling on Bowen's proposal. The matter probably further increased the enmity between the two men. That seems not to have dampened Bowen's enthusiasm for the area around Mt Tomah, and his advocacy of a new road was likely motivated, at least in part, by self interest. However, it was the Victoria Pass route that received approval and funding and became the main route. Although a primitive road was blazed using convict labour, 'Bell's Road' or 'Bell's New Line' was rarely used, even by the early 1830s. For many years, it was effectively just a stock route; it was not opened as a public road across the mountains until September 1905.

Mitchell's promotion and the end of the Darling administration in 1831, undoubtedly curtailed Bowen's career as an assistant-surveyor. Mitchell went on to greatly strengthen the professional core of his survey department, by appointing English immigrant surveyors and survey draftsmen, such as Samuel Augustus Perry

Samuel Augustus Perry (1787–1854) was an English-born soldier and surveyor.

Biography

Early life

Samuel Augustus Perry was born 17 March 1787 in Wales. He was baptized 12 September 1791 in Holborn, London. He was the son of Jabez Perry, gol ...

(the new Deputy Surveyor-General), James Larmer

James Larmer (b. 1808 or 1809 – d. 1886) was a government surveyor in the colony of New South Wales. Between 1830 and 1859, he surveyed land, roads and settlements in New South Wales. He was an Assistant Surveyor to the Surveyor-General, Sir Th ...

, Edmund Kennedy

Edmund Besley Court Kennedy J. P. (5 September 1818 – December 1848) was an explorer in Australia in the mid nineteenth century. He was the Assistant-Surveyor of New South Wales, working with Sir Thomas Mitchell. Kennedy explored the interio ...

, and numerous others.

Early settler in the Blue Mountains

Although most of the high parts of the Blue Mountains are sandstone country and relatively infertile, Mt Tomah and the surrounding area has deep, rich, volcanic soil. Bowen probably first encountered the area himself, while surveying the boundaries of the new County of Cook.

Bowen's mother, Susannah, came out to New South Wales in 1827. In 1830, she requested from Darling, and received, a land grant of two square miles around the summit of

Although most of the high parts of the Blue Mountains are sandstone country and relatively infertile, Mt Tomah and the surrounding area has deep, rich, volcanic soil. Bowen probably first encountered the area himself, while surveying the boundaries of the new County of Cook.

Bowen's mother, Susannah, came out to New South Wales in 1827. In 1830, she requested from Darling, and received, a land grant of two square miles around the summit of Mount Tomah

Mount Tomah is a locality and a mountain that is located in the Blue Mountains region of the state of New South Wales, Australia. The locality is known for the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden on the Bells Line of Road.

Description

The villa ...

. Bowen himself received a land grant of four square miles, nearby, at what is now Berambing

Berambing is a rural locality in the Blue Mountains (New South Wales), Blue Mountains of New South Wales, Australia. The settlement is clustered around the Bells Line of Road, between Windsor, New South Wales, Windsor and Lithgow, New South Wale ...

, and he established a farm named 'Bulgamatta'—said to be from Aboriginal language for 'mountain and water'—there in 1831. Bowen cleared and developed his land using convict labour, built a house, and set up a sawmill on what is now known as Bowen's Creek. He had a road built between his house and the sawmill, about 300 m lower in elevation. Even with convict labour provided by the colonial government, Bowen had a difficult life in what was then near wilderness. Although his landholdings had been taken up in 1830-31, the deed of grant was not finalised until 1836. Soon afterwards in 1836, Bowen sold his landholding. and later that year bought a town allotment in Windsor

Windsor may refer to:

Places Australia

* Windsor, New South Wales

** Municipality of Windsor, a former local government area

* Windsor, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane, Queensland

**Shire of Windsor, a former local government authority around Wi ...

.

Bowen and his convict labourers were the first colonial settlers around Mt Tomah but, of course, not the first people in the area. Bowen found nobody living permanently on what he then saw as his land, but that land was only a very small part of the traditional lands of local Aboriginal people. During his time at 'Bulgamatta', Bowen had peaceful interactions with Aboriginal people, who passed across it. These people included one young man 'Billy Kootee', whose cooperation Bowen courted. When the others in his clan moved on, Kootee stayed on 'Bulgamatta', and appears to have assisted Bowen as a guide, when Bowen explored the local area and when surveying land. Bowen had a brass breastplate made that declared Kootee to be the 'King of Mt Tomah'. However, there is evidence neither that Kootee was a leader among his people, nor that there was an Aboriginal clan associated only with Mt Tomah and its surrounds.

Susannah returned to England in 1836, giving her son a power of attorney

A power of attorney (POA) or letter of attorney is a written authorization to represent or act on another's behalf in private affairs (which may be financial or regarding health and welfare), business, or some other legal matter. The person auth ...

over her land at Mount Tomah. Bowen attempted unsuccessfully to sell it in 1838 and again in 1854; that land then passed into the hands of Bowen's son, George Bartley Bowen. The land at Mount Tomah—together with Bowen's later landholding at 'Bowen Mount'—was operated as orchards, for cattle raising, and as a dairy farm.

Relations with the church, first marriage, and Berrima

For a time, in the mid-1830s, it appeared that Bowen was destined to become aChurch of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

clergyman.

Bishop William Broughton

William Grant Broughton (22 May 178820 February 1853) was an Anglican bishop. He was the first (and only) Bishop of Australia of the Church of England. The then Diocese of Australia, has become the Anglican Church of Australia and is divided ...

, first and only Church of England, Bishop of Australia, was a conservative churchman who was favoured during the years of Darling's administration. Later, he opposed the reforms of liberal-minded Governor Richard Bourke

General Sir Richard Bourke, KCB (4 May 1777 – 12 August 1855), was an Irish-born British Army officer who served as Governor of New South Wales from 1831 to 1837. As a lifelong Whig (Liberal), he encouraged the emancipation of convicts and ...

, who took over from Darling in 1831. Bourke disestablished the Church of England and declared each religious denomination on equal footing before the law. Broughton was a 'Tractarian

The Oxford Movement was a movement of high church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the University of O ...

', and his opposition to Bourke's reforms fits within the context of Tractarian opposition to Whig government-led reforms

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement ...

, in England and Ireland, at around the same time.

One of Broughton's great difficulties was a shortage of Anglican clergy in the colony. Broughton saw religiously-minded and apparently respectable Bowen as a potential candidate for ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorization, authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominational ...

, leaving it with Bowen to consider his position. Bowen's public response was to publish a book on theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

in 1836. His religious views proved unorthodox, leading to controversy and opposition to his ordination, to such an extent that he was denied the sacrament

A sacrament is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments ...

at his local church in Windsor. Once ordination was actually denied to him, Bowen protested to the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of col ...

.

The controversy that he had caused apparently had subsided by March 1837, when Bowen was married to Charlotte Augusta Freer, daughter of Lieutenant Thomas Freer (or Fryer), in the same church, in which he had been denied the sacrament in 1836, and by the by the same clergyman, who had denied it to him, Henry Tarlton Stiles. Bowen's relationship with Stiles seems to have been a complicated one, as Bowen was the godfather of Stiles' son, Henry Bowen Augustine Stiles, born in 1834.

In 1839, Bowen was appointed as Police Magistrate at Berrima. The Bowen family were living at there when, at only 22 years of age, Charlotte died, in 1840, leaving Bowen with their two small children. Her death notice in the ''Sydney Morning Herald'', was accompanied by one for Bowen's mother, who had died earlier in 1840. Charlotte's remains are buried in the churchyard

In Christian countries a churchyard is a patch of land adjoining or surrounding a church, which is usually owned by the relevant church or local parish itself. In the Scots language and in both Scottish English and Ulster-Scots, this can also ...

of All Saint's Anglican Church, at Sutton Forest

Sutton Forest is a small village in the Southern Highlands, New South Wales, Australia in Wingecarribee Shire. It is located 5 km southwest of Moss Vale on the Illawarra Highway. Sutton Forest was originally granted, then owned by Navy Ch ...

. In 1840, following Charlotte’s death, Bowen sold land in the Windsor township.

Bowen heard the confession by the bushranger and serial killer, John Lynch, made on the day before Lynch's execution at Berrima Gaol, in April 1842. After the execution, he searched for the bodies of victims, to whose murders Lynch had confessed. By finding human remains, he was able to discharge two innocent men being held on murder charges.

He resigned as Police Magistrate and, on 30 January 1843, was farewelled by notables of the Berrima district—for his return to England. The farewell address was given by Charles Throsby

Charles Throsby (1777 – 2 April 1828) was an English surgeon who, after he migrated to New South Wales in 1802, became an explorer, pioneer and parliamentarian. He opened up much new land beyond the Blue Mountains for colonial settlement ...

. However, Bowen still owned land in the colony, and it seems he did not plan his return to England as being permanent.

England, second marriage, and 'Bowen Mount'

He made the journey to England in 1843 and, while there, married his deceased wife’s sister, Letitia, in August of that year. Such a marriage would not be allowed, by law, in England until 1907, or in New South Wales until February 1876. Not deterred by the existingcanon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

and the Marriage Act of 1835, Bowen had banns of marriage

The banns of marriage, commonly known simply as the "banns" or "bans" (from a Middle English word meaning "proclamation", rooted in Frankish and thence in Old French), are the public announcement in a Christian parish church, or in the town cou ...

read and a marriage ceremony was performed at the Church of St. Martin's in the Fields. However, to overcome the legal fact that their Anglican marriage was void, the couple then reportedly married for a second time, at Wandsbek

Wandsbek () is the second-largest of seven Boroughs and quarters of Hamburg#Boroughs, boroughs that make up the city and state of Hamburg, Germany. The name of the district is derived from the river Wandse which passes through here. Hamburg-Wandsb ...

—then a Danish-ruled exclave

An enclave is a territory (or a small territory apart of a larger one) that is entirely surrounded by the territory of one other state or entity. Enclaves may also exist within territorial waters. ''Enclave'' is sometimes used improperly to deno ...

of the Duchy of Holstein

The Duchy of Holstein (german: Herzogtum Holstein, da, Hertugdømmet Holsten) was the northernmost state of the Holy Roman Empire, located in the present German state of Schleswig-Holstein. It originated when King Christian I of Denmark had his ...

—in a Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

ceremony, under a letter of permission given by the King of Denmark

The monarchy of Denmark is a constitutional political system, institution and a historic office of the Kingdom of Denmark. The Kingdom includes Denmark proper and the autonomous administrative division, autonomous territories of the Faroe ...

. It is a testament to the lengths to which Bowen would go to assert his own views, against both church and state. Indeed, it is quite conceivable that the entire overseas journey was necessary, only because it would not have been possible for Bowen to marry Letitia, in New South Wales.

Bowen almost certainly knew that his English marriage would not be recognised in the colony. He had an announcement notice, with details of both wedding ceremonies, inserted in the ''Sydney Morning Herald

''The Sydney Morning Herald'' (''SMH'') is a daily compact newspaper published in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, and owned by Nine. Founded in 1831 as the ''Sydney Herald'', the ''Herald'' is the oldest continuously published newspaper i ...

'', three years later in 1846, after his return to New South Wales. The second marriage produced another four children, who were both first cousins and half-siblings to his two earlier children.

In February 1842, Bowen had obtained title over 83 acres in the County of Cook. This was the foundation of Bowen's landholding, 'Bowen Mount', at what would become later be known as Bowen Mountain. It would become his family's home, once he returned to New South Wales and built a substantial timber house, on the highest ridge. The house was surrounded by ornate gardens and orange orchards. He had acquired another 303 acres in 1847.

Not content to let his disputes with the church die down, Bowen authored another theological work, with his authorship thinly disguised, under the pseudonym of Aposynagogos. He finally broke his connection with the church altogether, after Bishop Frederick Barker replaced Broughton in 1855.

Later life and death

In 1854, Bowen was appointed surveyor of roads for the road to Bathurst, but it was a short-lived role, ending after he fell out with his trustees. He was to spend most of the rest of his life living quietly at 'Bowen Mount', before moving finally to 'Keston', in Carabella Street, Kirribilli, late in life. Around 1876, he privately published an autobiography, ''Autobiography, Modern Parables and Predictions''. In earlier life, Bowen was a man who had both much promise and much opportunity, He grew to be wealthy in old age. However, he did not achieve the honours and social status that he craved, largely due to his querulous, argumentative, and stubborn personality. Bowen died at Kirribilli, on 1 September 1889. His remains lie buried, in what is nowSt Thomas Rest Park

St Thomas Rest Park, located in West Street, Crows Nest, New South Wales is the site of the first cemetery on Sydney's North Shore. It is the largest park in the densely populated Crows Nest area.

Cemetery

The land that now contains the St T ...

, in Crows Nest, as do those of his second wife Letitia, who died in 1901, and some of his children and their spouses. His estate was valued at £35,024.

Legacy

Bowen is remembered by the naming of Bowenfels (originally known as Bowen's Hollow), Bowen Mountain, Bowen’s Creek near Mount Irvine, and the Parish of Bowen, all in the Blue Mountains area. Bowen's mother's former land, at Mount Tomah, is now theBlue Mountains Botanic Garden

The Blue Mountains Botanic Garden, originally known as the Mount Tomah Botanical Garden, is a public botanic garden located approximately west of the Sydney central business district at in the Blue Mountains (New South Wales), Blue Mountains, ...

.

His house, 'Bowen Mount', burnt down in a fire in 1914. The land was subjected to subdivision from 1960, although issues with handling sewage have limited the extent to which the area has been developed for housing. The area is now known as Bowen Mountain.

The State Library of New South Wales

The State Library of New South Wales, part of which is known as the Mitchell Library, is a large heritage-listed special collections, reference and research library open to the public and is one of the oldest libraries in Australia. Establish ...

contains a number of photographs of the Bowen family, in the pictorial material from the papers of Rae Else-Mitchell

Rae Else-Mitchell (20 September 191429 June 2006) was an Australian jurist, royal commissioner, historian and legal scholar. He was an active member and office bearer in a number of community organisations concerned with history, the arts, libra ...

.

Bowen's autobiography, specifically the parts concerning his interactions with Aboriginal people, has been used by scholars to identify the group of Aboriginal people that Bowen met in the 1830s. However, different scholars have reached different conclusions, on whether those people were Darkinung people of the northern mountains or Dharug

The Dharug or Darug people, formerly known as the Broken Bay tribe, are an Aboriginal Australian people, who share strong ties of kinship and, in pre-colonial times, lived as skilled hunters in family groups or clans, scattered throughout much ...

people of the Cumberland Plain

The Cumberland Plain, an IBRA biogeographic region, is a relatively flat region lying to the west of Sydney CBD in New South Wales, Australia. Cumberland Basin is the preferred physiographic and geological term for the low-lying plain of the ...

and Georges River

The Georges River, also known as Tucoerah River, is an intermediate tide-dominated drowned valley estuary, located to the south and west of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

The river travels for approximately in a north and then easterly ...

. These different conclusions still affect people, who trace their ancestry to survivors of the colonisation of the region.

Bowen's disputes with the church, over church doctrine and matrimony, are now largely forgotten. However, his second marriage, and that of Bowen's contemporary, Charles Joseph La Trobe

Charles la Trobe, CB (20 March 18014 December 1875), commonly Latrobe, was appointed in 1839 superintendent of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales and, after the establishment in 1851 of the colony of Victoria (now a state of Australi ...

, can now be seen as early instances of defiance against religiously-inspired legal restrictions on marriage, which would later progress over much time to become the "Marriage Equality

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same Legal sex and gender, sex or gender. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 33 countries, with the most recent being ...

" movement.

Reference section

External links section

Australian Dictionary of Biography: Bowen, George Meares Countess

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bowen, George Settlers of New South Wales 1803 births 1889 deaths