Galapagos Shark on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Galapagos shark (''Carcharhinus galapagensis'') is a

Biological Profiles: Galapagos Shark

. ''Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department''. Retrieved on April 26, 2009. Garrick (1982) placed the Galapagos shark and the dusky shark at the center of the "obscurus group", one of two major groupings within ''Carcharhinus''. The group consisted of the bignose shark (''C. altimus''), Caribbean reef shark (''C. perezi''),

The Galapagos shark is found mainly off tropical oceanic islands. In the

The Galapagos shark is found mainly off tropical oceanic islands. In the

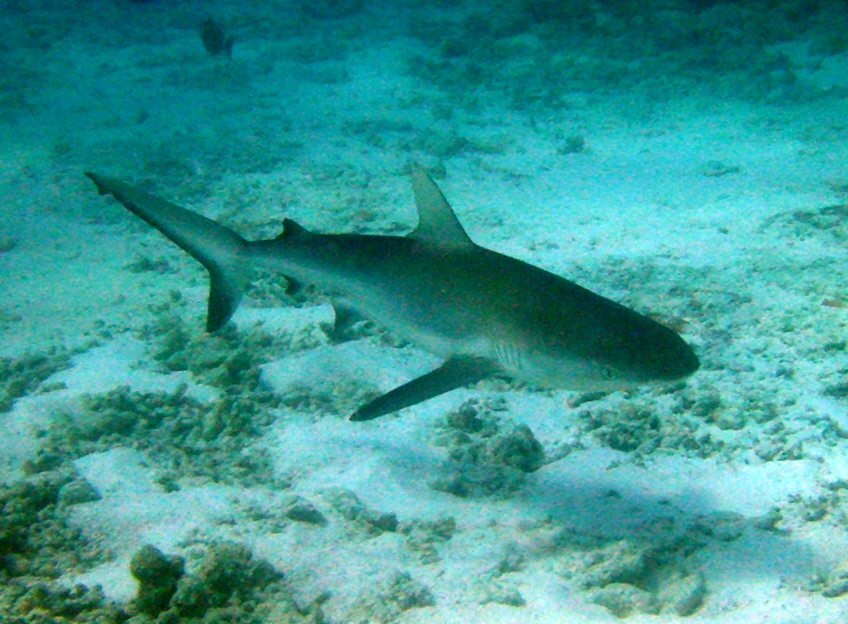

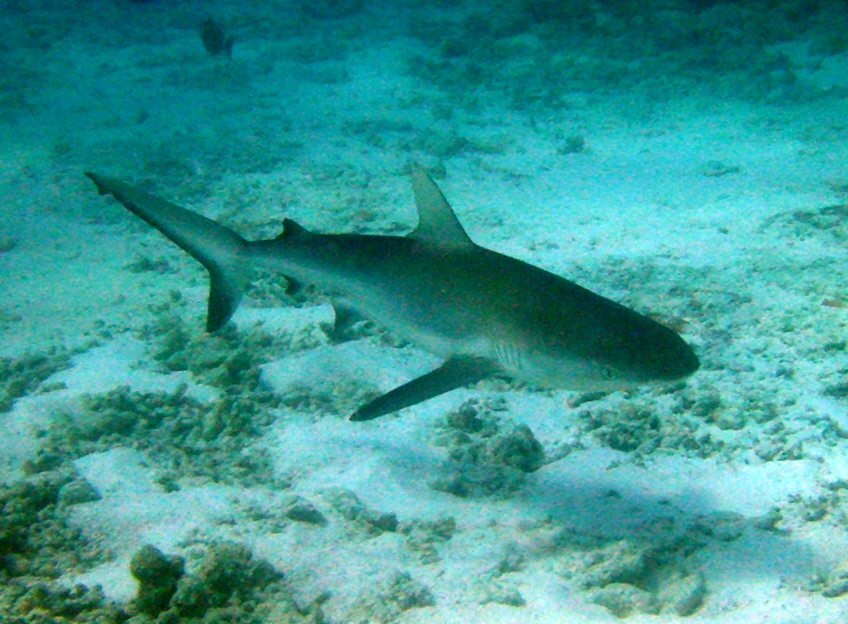

One of the largest species in its genus, the Galapagos shark commonly reaches long. The maximum length has been variously recorded as to . The maximum recorded weight is for a long female (longer specimens having apparently been unweighed). This species has a slender, streamlined body typical of the requiem sharks. The snout is wide and rounded, with indistinct anterior nasal flaps. The eyes are round and of medium size. The mouth usually contains 14 tooth rows (range 13–15) on either side of both jaws, plus one tooth at the

One of the largest species in its genus, the Galapagos shark commonly reaches long. The maximum length has been variously recorded as to . The maximum recorded weight is for a long female (longer specimens having apparently been unweighed). This species has a slender, streamlined body typical of the requiem sharks. The snout is wide and rounded, with indistinct anterior nasal flaps. The eyes are round and of medium size. The mouth usually contains 14 tooth rows (range 13–15) on either side of both jaws, plus one tooth at the

The Galapagos shark is often the most abundant shark in shallow island waters. In their original description of this species, Snodgrass and Heller noted that their schooner had taken "several hundred" adult Galapagos sharks and that "thousands" more could be seen in the water. At the isolated

The Galapagos shark is often the most abundant shark in shallow island waters. In their original description of this species, Snodgrass and Heller noted that their schooner had taken "several hundred" adult Galapagos sharks and that "thousands" more could be seen in the water. At the isolated

The primary food of Galapagos sharks are benthic bony fishes (including

The primary food of Galapagos sharks are benthic bony fishes (including

Inquisitive and persistent, the Galapagos shark is regarded as potentially dangerous to humans. However, several live-aboard boats take divers to Wolf and Darwin, the northernmost Galapagos islands, every week specifically to dive in open water with these sharks where they and the scalloped hammerheads accumulate in numbers, and only a few incidents have been reported. They are known to approach close to swimmers, showing interest in

Inquisitive and persistent, the Galapagos shark is regarded as potentially dangerous to humans. However, several live-aboard boats take divers to Wolf and Darwin, the northernmost Galapagos islands, every week specifically to dive in open water with these sharks where they and the scalloped hammerheads accumulate in numbers, and only a few incidents have been reported. They are known to approach close to swimmers, showing interest in

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

of requiem shark

Requiem sharks are sharks of the family Carcharhinidae in the order Carcharhiniformes. They are migratory, live-bearing sharks of warm seas (sometimes of brackish or fresh water) and include such species as the tiger shark, bull shark, le ...

, in the family Carcharhinidae, found worldwide. It favors clear reef environments around oceanic islands, where it is often the most abundant shark species. A large species that often reaches , the Galapagos reef shark has a typical fusiform "reef shark" shape and is very difficult to distinguish from the dusky shark (''C. obscurus'') and the grey reef shark

The grey reef shark (''Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos'', sometimes misspelled ''amblyrhynchus'' or ''amblyrhinchos'') is a species of requiem shark, in the family Carcharhinidae. One of the most common reef sharks in the Indo-Pacific, it is found as ...

(''C. amblyrhynchos''). An identifying character of this species is its tall first dorsal fin

A dorsal fin is a fin located on the back of most marine and freshwater vertebrates within various taxa of the animal kingdom. Many species of animals possessing dorsal fins are not particularly closely related to each other, though through c ...

, which has a slightly rounded tip and originates over the rear tips of the pectoral fin

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as ...

s.

The Galapagos shark is an active predator often encountered in large groups. It feeds mainly on bottom-dwelling bony fishes and cephalopods; larger individuals have a much more varied diet, consuming other sharks, marine iguana

The marine iguana (''Amblyrhynchus cristatus''), also known as the sea iguana, saltwater iguana, or Galápagos marine iguana, is a species of iguana found only on the Galápagos Islands (Ecuador). Unique among modern lizards, it is a marine rept ...

s, sea lion

Sea lions are pinnipeds characterized by external ear flaps, long foreflippers, the ability to walk on all fours, short and thick hair, and a big chest and belly. Together with the fur seals, they make up the family Otariidae, eared seals. ...

s, and even garbage. As in other requiem sharks, reproduction is viviparous

Among animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the parent. This is opposed to oviparity which is a reproductive mode in which females lay developing eggs that complete their development and hatch externally from the ...

, with females bearing litters of 4–16 pups every 2 to 3 years. The juveniles tend to remain in shallow water to avoid predation by the adults. The International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of nat ...

(IUCN) has assessed this species as least concern

A least-concern species is a species that has been categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as evaluated as not being a focus of species conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wild. T ...

, but it has a slow reproductive rate and there is heavy fishing pressure across its range.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The Galapagos shark was originally described as ''Carcharias galapagensis'' byRobert Evans Snodgrass

Robert Evans Snodgrass (R.E. Snodgrass) (July 5, 1875 – September 4, 1962) was an American entomologist and artist who made important contributions to the fields of arthropod morphology, anatomy, evolution, and metamorphosis.

He was the aut ...

and Edmund Heller

Edmund Heller (May 21, 1875 – July 18, 1939) was an American zoologist. He was President of the Association of Zoos & Aquariums for two terms, from 1935-1936 and 1937-1938.

Early life

While at Stanford University, he collected specimens in th ...

in 1905; subsequent authors moved this species to the genus ''Carcharhinus''. The holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of sever ...

was a long fetus

A fetus or foetus (; plural fetuses, feti, foetuses, or foeti) is the unborn offspring that develops from an animal embryo. Following embryonic development the fetal stage of development takes place. In human prenatal development, fetal dev ...

from the Galapagos Islands, hence the specific epithet ''galapagensis''.Bester, CBiological Profiles: Galapagos Shark

. ''Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department''. Retrieved on April 26, 2009. Garrick (1982) placed the Galapagos shark and the dusky shark at the center of the "obscurus group", one of two major groupings within ''Carcharhinus''. The group consisted of the bignose shark (''C. altimus''), Caribbean reef shark (''C. perezi''),

sandbar shark

The sandbar shark (''Carcharhinus plumbeus'') also known as the brown shark or thickskin shark, is a species of requiem shark, and part of the family Carcharhinidae, native to the Atlantic Ocean and the Indo-Pacific. It is distinguishable by it ...

(''C. plumbeus''), dusky shark (''C. obscurus''), and oceanic whitetip shark

The oceanic whitetip shark (''Carcharhinus longimanus''), also known as shipwreck shark, Brown Milbert's sand bar shark, brown shark, lesser white shark, nigano shark, oceanic white-tipped whaler, and silvertip shark, is a large pelagic requiem ...

(''C. longimanus''), all large, triangular-toothed sharks and is defined by the presence of a ridge between the two dorsal fins.Garrick, J.A.F. (1982). "Sharks of the genus ''Carcharhinus''". NOAA Technical Report, NMFS CIRC-445. Based on allozyme data, Naylor (1992) reaffirmed the integrity of this group, with the additions of the silky shark

The silky shark (''Carcharhinus falciformis''), also known by numerous names such as blackspot shark, gray whaler shark, olive shark, ridgeback shark, sickle shark, sickle-shaped shark and sickle silk shark, is a species of requiem shark, in the ...

(''C. falciformis'') and the blue shark (''Prionace glauca''). The closest relatives of the Galapagos shark were found to be the dusky, oceanic whitetip, and blue sharks.

Distribution and habitat

The Galapagos shark is found mainly off tropical oceanic islands. In the

The Galapagos shark is found mainly off tropical oceanic islands. In the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

, it occurs around Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = "Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, es ...

, the Virgin Islands

The Virgin Islands ( es, Islas Vírgenes) are an archipelago in the Caribbean Sea. They are geologically and biogeographically the easternmost part of the Greater Antilles, the northern islands belonging to the Puerto Rico Trench and St. Cro ...

, Madeira, Cape Verde, Ascension Island, Saint Helena and São Tomé Island

São Tomé Island, at , is the largest island of São Tomé and Príncipe and is home in May 2018 to about 193,380 or 96% of the nation's population. The island is divided into six districts. It is located 2 km (1¼ miles) north of the equ ...

. In the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by t ...

, it is known from Walter's Shoal off southern Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

. In the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contin ...

, it occurs around Lord Howe Island

Lord Howe Island (; formerly Lord Howe's Island) is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand, part of the Australian state of New South Wales. It lies directly east of mainland P ...

, the Marianas Islands

The Mariana Islands (; also the Marianas; in Chamorro: ''Manislan Mariånas'') are a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen longitudinally oriented, mostly dormant volcanic mountains in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, betw ...

, the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Intern ...

, the Kermadec Islands

The Kermadec Islands ( mi, Rangitāhua) are a subtropical island arc in the South Pacific Ocean northeast of New Zealand's North Island, and a similar distance southwest of Tonga. The islands are part of New Zealand. They are in total ar ...

, Tupai

Tupai ( ty, Tūpai), also called Motu Iti, is a low-lying atoll in Society Islands, French Polynesia. It lies 19 km to the north of Bora Bora and belongs to the western Leeward Islands ( French: ''Îles Sous-le-vent''). This small atoll is ...

, the Tuamotu Archipelago

The Tuamotu Archipelago or the Tuamotu Islands (french: Îles Tuamotu, officially ) are a French Polynesian chain of just under 80 islands and atolls in the southern Pacific Ocean. They constitute the largest chain of atolls in the world, extendin ...

, the Juan Fernández Islands

The Juan Fernández Islands ( es, Archipiélago Juan Fernández) are a sparsely inhabited series of islands in the South Pacific Ocean reliant on tourism and fishing. Situated off the coast of Chile, they are composed of three main volcanic i ...

, the Hawaiian Islands, the Galapagos Islands, Cocos Island

Cocos Island ( es, Isla del Coco) is an island in the Pacific Ocean administered by Costa Rica, approximately southwest of the Costa Rican mainland. It constitutes the 11th of the 13 districts of Puntarenas Canton of the Province of Puntarena ...

, the Revillagigedo Islands

The Revillagigedo Islands ( es, Islas Revillagigedo, ) or Revillagigedo Archipelago are a group of four volcanic islands in the Pacific Ocean, known for their unique ecosystem. They lie approximately from Socorro Island south and southwest of C ...

, Clipperton Island

Clipperton Island ( or ; ) is an uninhabited, coral atoll in the eastern Pacific Ocean. It is from Paris, France, from Papeete, Tahiti, and from Mexico. It is an overseas state private property of France under direct authority of the Minis ...

, and Malpelo. There are a few reports of this species in continental waters off the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

, Baja California

Baja California (; 'Lower California'), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Baja California), is a state in Mexico. It is the northernmost and westernmost of the 32 federal entities of Mex ...

, Guatemala, Colombia, and eastern Australia.

The Galapagos shark is generally found over continental and insular shelves near the coast, preferring rugged reef

A reef is a ridge or shoal of rock, coral or similar relatively stable material, lying beneath the surface of a natural body of water. Many reefs result from natural, abiotic processes— deposition of sand, wave erosion planing down rock o ...

habitats with clear water and strong converging currents

Currents, Current or The Current may refer to:

Science and technology

* Current (fluid), the flow of a liquid or a gas

** Air current, a flow of air

** Ocean current, a current in the ocean

*** Rip current, a kind of water current

** Current (stre ...

. It is also known to form groups around rocky islets and seamounts. This species is capable of crossing the open ocean

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or wa ...

between islands and has been reported at least from land. Juveniles seldom venture deeper than , while adults have been reported to a depth of .

Description

One of the largest species in its genus, the Galapagos shark commonly reaches long. The maximum length has been variously recorded as to . The maximum recorded weight is for a long female (longer specimens having apparently been unweighed). This species has a slender, streamlined body typical of the requiem sharks. The snout is wide and rounded, with indistinct anterior nasal flaps. The eyes are round and of medium size. The mouth usually contains 14 tooth rows (range 13–15) on either side of both jaws, plus one tooth at the

One of the largest species in its genus, the Galapagos shark commonly reaches long. The maximum length has been variously recorded as to . The maximum recorded weight is for a long female (longer specimens having apparently been unweighed). This species has a slender, streamlined body typical of the requiem sharks. The snout is wide and rounded, with indistinct anterior nasal flaps. The eyes are round and of medium size. The mouth usually contains 14 tooth rows (range 13–15) on either side of both jaws, plus one tooth at the symphysis

A symphysis (, pl. symphyses) is a fibrocartilaginous fusion between two bones. It is a type of cartilaginous joint, specifically a secondary cartilaginous joint.

# A symphysis is an amphiarthrosis, a slightly movable joint.

# A growing togethe ...

(where the jaw halves meet). The upper teeth are stout and triangular in shape, while the lower teeth are narrower; both upper and lower teeth have serrated edges.

The first dorsal fin

A dorsal fin is a fin located on the back of most marine and freshwater vertebrates within various taxa of the animal kingdom. Many species of animals possessing dorsal fins are not particularly closely related to each other, though through c ...

is tall and moderately falcate (sickle-shaped), with the origin over the pectoral fin

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as ...

rear tips. It is followed by a low midline ridge running to the second dorsal fin. The second dorsal fin originates over the anal fin. The pectoral fins are large with pointed tips. The coloration is brownish gray above and white below, with a faint white stripe on the sides. The edges of the fins are darker but not prominently marked. The Galapagos shark can be distinguished from the dusky shark in having taller first and second dorsal fins and larger teeth, and it can be distinguished from the grey reef shark in having a less robust body and less pointed first dorsal fin tip. However, these characters can be difficult to discern in the field. These similar species also have different numbers of precaudal (before the tail) vertebra

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

e: 58 in the Galapagos shark, 86–97 in the dusky shark, 110–119 in the grey reef shark.

Biology and ecology

The Galapagos shark is often the most abundant shark in shallow island waters. In their original description of this species, Snodgrass and Heller noted that their schooner had taken "several hundred" adult Galapagos sharks and that "thousands" more could be seen in the water. At the isolated

The Galapagos shark is often the most abundant shark in shallow island waters. In their original description of this species, Snodgrass and Heller noted that their schooner had taken "several hundred" adult Galapagos sharks and that "thousands" more could be seen in the water. At the isolated Saint Peter and Paul Rocks

The Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago ( pt, Arquipélago de São Pedro e São Paulo ) is a group of 15 small islets and rocks in the central equatorial Atlantic Ocean.

along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge (a divergent or constructive plate boundary) located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the longest mountain range in the world. In the North Atlantic, the ridge separates the North ...

, the resident Galapagos sharks have been described as "one of the densest shark populations of the Atlantic Ocean". At some locations they form large aggregations, though these are not true schools

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes compulsor ...

.

During group interactions, Galapagos sharks are dominant to blacktip sharks (''C. limbatus'') but deferent to silvertip shark

The silvertip shark (''Carcharhinus albimarginatus'') is a large species of requiem shark, in the family Carcharhinidae, with a fragmented distribution throughout the tropical Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is often encountered around offshore is ...

s (''C. albimarginatus'') of equal size. When confronted or cornered, the Galapagos shark may perform a threat display

Deimatic behaviour or startle display means any pattern of bluffing behaviour in an animal that lacks strong defences, such as suddenly displaying conspicuous eyespots, to scare off or momentarily distract a predator, thus giving the prey anima ...

similar to that of the grey reef shark, in which the shark performs an exaggerated, rolling swimming motion while arching its back, lowering its pectoral fins, puffing out its gills, and gaping its jaw. The shark may also swing its head from side to side, so as to keep the perceived threat within its field of vision. A known parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

of the Galapagos shark is the flatworm ''Dermophthirius carcharhini'', which attaches to the shark's skin. In one account, a bluefin trevally

The bluefin trevally (''Caranx melampygus''), also known as the bluefin jack, bluefin kingfish, bluefinned crevalle, blue ulua, omilu, and spotted trevally), is a species of large, widely distributed marine fish classified in the jack family, Ca ...

(''Caranax melampygus'') was seen rubbing against the rough skin of a Galapagos shark to rid itself of parasites.

Feeding

The primary food of Galapagos sharks are benthic bony fishes (including

The primary food of Galapagos sharks are benthic bony fishes (including eel

Eels are ray-finned fish belonging to the order Anguilliformes (), which consists of eight suborders, 19 families, 111 genera, and about 800 species. Eels undergo considerable development from the early larval stage to the eventual adult stage ...

s, sea bass

Sea bass is a common name for a variety of different species of marine fish. Many fish species of various families have been called sea bass.

In Ireland and the United Kingdom, the fish sold and consumed as sea bass is exclusively the European ...

, flatfish, flatheads, and triggerfish

Triggerfish are about 40 species of often brightly colored fish of the family Balistidae. Often marked by lines and spots, they inhabit tropical and subtropical oceans throughout the world, with the greatest species richness in the Indo-Pacifi ...

) and octopuses. They also occasionally take surface-dwelling prey such as mackerel, flyingfish

The Exocoetidae are a family of marine fish in the order Beloniformes class Actinopterygii, known colloquially as flying fish or flying cod. About 64 species are grouped in seven to nine genera. While they cannot fly in the same way a bird ...

and squid. As the sharks grow larger, they consume increasing numbers of elasmobranch

Elasmobranchii () is a subclass of Chondrichthyes or cartilaginous fish, including sharks (superorder Selachii), rays, skates, and sawfish (superorder Batoidea). Members of this subclass are characterised by having five to seven pairs of g ...

s (rays

Ray may refer to:

Fish

* Ray (fish), any cartilaginous fish of the superorder Batoidea

* Ray (fish fin anatomy), a bony or horny spine on a fin

Science and mathematics

* Ray (geometry), half of a line proceeding from an initial point

* Ray (gra ...

and smaller sharks, including of their own species) and crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group can ...

s, as well as indigestible items such as leaves, coral, rocks, and garbage. At the Galapagos Islands, this species has been observed attacking Galapagos fur seals (''Arctophoca galapagoensis'') and sea lion

Sea lions are pinnipeds characterized by external ear flaps, long foreflippers, the ability to walk on all fours, short and thick hair, and a big chest and belly. Together with the fur seals, they make up the family Otariidae, eared seals. ...

s (''Zalophus wollebaeki''), and marine iguana

The marine iguana (''Amblyrhynchus cristatus''), also known as the sea iguana, saltwater iguana, or Galápagos marine iguana, is a species of iguana found only on the Galápagos Islands (Ecuador). Unique among modern lizards, it is a marine rept ...

s (''Amblyrhynchus cristatus''). While collecting fishes at Clipperton Island, Limbaugh (1963) noted that juvenile Galapagos sharks surrounded the boat, with multiple individuals rushing at virtually anything trailing in the water and striking the boat bottom, oars, and marker buoys. The sharks were not slowed by rotenone

Rotenone is an odorless, colorless, crystalline isoflavone used as a broad-spectrum insecticide, piscicide, and pesticide. It occurs naturally in the seeds and stems of several plants, such as the jicama vine plant, and the roots of several mem ...

(a fish toxin) or shark repellent

A shark repellent is any method of driving sharks away from an area. Shark repellents are a category of animal repellents. Shark repellent technologies include magnetic shark repellent, electropositive shark repellents, electrical repellents, ...

, and some followed the boat into water so shallow that their backs were exposed.

Life history

Like other requiem sharks, the Galapagos shark exhibits aviviparous

Among animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the parent. This is opposed to oviparity which is a reproductive mode in which females lay developing eggs that complete their development and hatch externally from the ...

mode of reproduction, in which the developing embryos are sustained by a placenta

The placenta is a temporary embryonic and later fetal organ that begins developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrient, gas and waste exchange between the physically separate mate ...

l connection formed from the depleted yolk sac

The yolk sac is a membranous sac attached to an embryo, formed by cells of the hypoblast layer of the bilaminar embryonic disc. This is alternatively called the umbilical vesicle by the Terminologia Embryologica (TE), though ''yolk sac'' is ...

. Females bear young once every 2–3 years. Mating takes place from January to March, at which time scars caused by male courtship bites appear on the females. The gestation period is estimated to be around one year; the spring following impregnation, females move into shallow nursery areas and give birth to 4–16 pups. The size at birth has been reported to be , though observations of free-swimming juveniles as small as long in the eastern Pacific suggest that birth size varies geographically. Juvenile sharks remain in shallow water to avoid predation by larger adults. Males mature at long and 6–8 years old, while females mature at long and 7–9 years old. Neither sex is thought to reproduce until 10 years of age. The lifespan of this species is at least 24 years.

Human interactions

Inquisitive and persistent, the Galapagos shark is regarded as potentially dangerous to humans. However, several live-aboard boats take divers to Wolf and Darwin, the northernmost Galapagos islands, every week specifically to dive in open water with these sharks where they and the scalloped hammerheads accumulate in numbers, and only a few incidents have been reported. They are known to approach close to swimmers, showing interest in

Inquisitive and persistent, the Galapagos shark is regarded as potentially dangerous to humans. However, several live-aboard boats take divers to Wolf and Darwin, the northernmost Galapagos islands, every week specifically to dive in open water with these sharks where they and the scalloped hammerheads accumulate in numbers, and only a few incidents have been reported. They are known to approach close to swimmers, showing interest in swim fin

Swim or SWIM may refer to:

Movement and sport

* Swim, a fad dance

* Aquatic locomotion, the act of biologically propelled motion through a liquid medium

* Human swimming, the useful or recreational activity of movement through water

* Swimming ...

s or hands, and are drawn in large numbers by fishing activities. Fitzroy (1839) observed off St. Paul's Rocks that "as soon as a fish was caught, a rush of voracious sharks was made at him, notwithstanding blows of oars and boat hooks, the ravenous monsters could not be deterred from seizing and taking away more than half the fish that were hooked". Limbaugh (1963) reported that at Clipperton Island

Clipperton Island ( or ; ) is an uninhabited, coral atoll in the eastern Pacific Ocean. It is from Paris, France, from Papeete, Tahiti, and from Mexico. It is an overseas state private property of France under direct authority of the Minis ...

"at first, the small sharks circled at a distance, but gradually they approached and became more aggressive ... various popular methods for repelling sharks proved unsuccessful". The situation eventually escalated to the point at which the divers had to retreat from the water. Excited Galapagos sharks are not easily deterred; driving one away physically only results in the shark circling back while inciting others to follow, whereas using weapons against them could trigger a feeding frenzy

In ecology, a feeding frenzy occurs when predators are overwhelmed by the amount of prey available. The term is also used as an idiom in the English language.

Examples in nature

For example, a large school of fish can cause nearby sharks, such a ...

.

As of 2008, the Galapagos shark has been confirmed to have attacked three people: one fatal attack in the Virgin Islands; a second fatal attack in the Virgin Islands, at Magens Bay

Magens Bay is a bay in the Northside region on Saint Thomas, United States Virgin Islands, in the Caribbean.

Description

Lying on the northern (Atlantic) side of the island, Magens Bay (Estate Zufriedenheit) features a well-protected white sa ...

on the north shore of St. Thomas; and a third non-fatal, attack off Bermuda. February 2018 saw a non-fatal shark attack in the Galapagos islands that shark photographer Jeremy Stafford-Deitsch suggested may have been carried out by a Galapagos shark, but the species remains unconfirmed.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of nat ...

(IUCN) has assessed the Galapagos shark as least concern

A least-concern species is a species that has been categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as evaluated as not being a focus of species conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wild. T ...

, but its low reproductive rate limits its capacity to withstand population depletion. There is no specific utilization data available, though this species is certainly caught by commercial fisheries

Commercial fishing is the activity of catching fish and other seafood for commercial profit, mostly from wild fisheries. It provides a large quantity of food to many countries around the world, but those who practice it as an industry must often p ...

operating across many parts of its range. The meat is said to be of excellent quality. While still common at areas such as Hawaii, the Galapagos shark may have been extirpated

Local extinction, also known as extirpation, refers to a species (or other taxon) of plant or animal that ceases to exist in a chosen geographic area of study, though it still exists elsewhere. Local extinctions are contrasted with global extinct ...

from sites around Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

and its fragmented distribution means other regional populations may also be at risk. The populations at the Kermadec and Galapagos Islands are protected within marine reserve

A marine reserve is a type of marine protected area (MPA). An MPA is a section of the ocean where a government has placed limits on human activity. A marine reserve is a marine protected area in which removing or destroying natural or cultural ...

s.

Conservation status

The New ZealandDepartment of Conservation

An environmental ministry is a national or subnational government agency politically responsible for the environment and/or natural resources. Various other names are commonly used to identify such agencies, such as Ministry of the Environment ...

has classified the Galapagos shark as "Not Threatened" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System with the qualifiers "Conservation Dependent" and "Secure Overseas".

References

External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:shark, Galapagos Galapagos shark Galápagos Islands coastal fauna Galapagos shark Natural history of the Revillagigedo Islands Galapagos shark Galapagos shark Taxa named by Edmund Heller