Günther Lütjens on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Johann Günther Lütjens (25 May 1889 – 27 May 1941) was a German admiral whose

He entered the Imperial German Navy (''

He entered the Imperial German Navy (''

military service

Military service is service by an individual or group in an army or other militia, air forces, and naval forces, whether as a chosen job (volunteer) or as a result of an involuntary draft (conscription).

Some nations (e.g., Mexico) require a ...

spanned more than thirty years and two world war

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

s. Lütjens is best known for his actions during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

and his command of the battleship during her foray into the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

in 1941.

Born in 1889, he entered into the German Imperial Navy () in 1907. A diligent and intelligent cadet

A cadet is an officer trainee or candidate. The term is frequently used to refer to those training to become an officer in the military, often a person who is a junior trainee. Its meaning may vary between countries which can include youths in ...

, he progressed to officer rank

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer, or a warrant officer. However, absent context ...

before the outbreak of war, when he was assigned to a Torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

Squadron. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Lütjens operated in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

and English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

and fought several actions against the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

. He ended the conflict as a ''Kapitänleutnant

''Kapitänleutnant'', short: KptLt/in lists: KL, ( en, captain lieutenant) is an officer grade of the captains' military hierarchy group () of the German Bundeswehr. The rank is rated OF-2 in NATO, and equivalent to Hauptmann in the Heer and ...

'' (captain lieutenant) with the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia est ...

1st and 2nd class (1914) to his credit. After the war he remained in the service of the navy, now renamed the ''Reichsmarine

The ''Reichsmarine'' ( en, Realm Navy) was the name of the German Navy during the Weimar Republic and first two years of Nazi Germany. It was the naval branch of the ''Reichswehr'', existing from 1919 to 1935. In 1935, it became known as the ''K ...

''. He continued to serve in torpedo boat squadrons eventually becoming a commanding officer

The commanding officer (CO) or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually given wide latitu ...

in 1925. In the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

era, Lütjens built a reputation as an excellent staff officer.

In 1935, after the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

came to power under Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

in 1933, the navy was remodelled again and renamed the ''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

''. Lütjens soon became acquainted with Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder (24 April 1876 – 6 November 1960) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II. Raeder attained the highest possible naval rank, that of grand admiral, in 1939, becoming the f ...

and Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (sometimes spelled Doenitz; ; 16 September 1891 24 December 1980) was a German admiral who briefly succeeded Adolf Hitler as head of state in May 1945, holding the position until the dissolution of the Flensburg Government follo ...

; the two commanders-in-chief of the ''Kriegsmarine'' in World War II. His capability and friendship led to his promotion to ''Kapitän zur See

Captain is the name most often given in English-speaking navies to the rank corresponding to command of the largest ships. The rank is equal to the army rank of colonel and air force rank of group captain.

Equivalent ranks worldwide include ...

'' (captain at sea) and a sea command at the helm of the cruiser . In the six years of peace he had risen to the rank of ''Konteradmiral

''Konteradmiral'', abbreviated KAdm or KADM, is the second lowest naval flag officer rank in the German Navy. It is equivalent to '' Generalmajor'' in the '' Heer'' and ''Luftwaffe'' or to '' Admiralstabsarzt'' and ''Generalstabsarzt'' in the '' ...

'' (rear admiral), a promotion conferred upon him October 1937.

In September 1939, World War II began with the German invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

. Lütjens received the Clasp to the Iron Cross

The Clasp to the Iron Cross (Spange zum Eisernen Kreuz) was a white metal medal clasp displayed on the uniforms of German Wehrmacht personnel who had been awarded the Iron Cross in World War I, and who again qualified for the decoration in World W ...

2nd Class (1939) three days later. His command of destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

operations in the North Sea over the winter, 1939–1940, earned him the Clasp to the Iron Cross 1st Class. On 1 January 1940, he was promoted to ''Vizeadmiral'' (vice admiral). In April 1940 he was given temporary command of the entire German surface fleet during the initial landing phase of Operation Weserübung

Operation Weserübung (german: Unternehmen Weserübung , , 9 April – 10 June 1940) was Germany's assault on Denmark and Norway during the Second World War and the opening operation of the Norwegian Campaign.

In the early morning of 9 Ap ...

, the invasions of Denmark and Norway. His actions earned him the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (german: Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes), or simply the Knight's Cross (), and its variants, were the highest awards in the military and paramilitary forces of Nazi Germany during World War II.

The Knight' ...

.

In the aftermath of the campaign he was appointed the fleet commander

The Fleet Commander is a senior Royal Navy post, responsible for the operation, resourcing and training of the ships, submarines and aircraft, and personnel, of the Naval Service. The Vice-Admiral incumbent is required to provide ships, submarine ...

of the German Navy and promoted to Admiral on 1 September 1940. He was involved in the tentative planning for Operation Sea Lion

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (german: Unternehmen Seelöwe), was Nazi Germany's code name for the plan for an invasion of the United Kingdom during the Battle of Britain in the Second World War. Following the Battle o ...

, the planned invasion of the United Kingdom, but the plans were shelved after the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

. German intentions turned to blockade and Lütjens made the German battlecruisers/battleships and the centerpiece of his battle fleet; using the latter vessel as his flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

. In January 1941, he planned and executed Operation Berlin, an Atlantic raid to support U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s in the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blockade ...

by attacking British merchant shipping lanes. The operation was a tactical victory

In military tactics, a tactical victory may refer to a victory that results in the completion of a tactical objective as part of an military operation, operation or a result in which the losses of the "defeated" outweigh those of the "victor" al ...

. It came to a close in March 1941, when the ships docked in German-occupied France

The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frankreich; french: Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zo ...

after sailing some 18,000 miles; a record for a German battle group at the time.

In May 1941, Lütjens commanded a German task force, consisting of the battleship ''Bismarck'' and the heavy cruiser , during Operation Rheinübung

Operation Rheinübung ("Exercise Rhine") was the sortie into the Atlantic by the new German battleship and heavy cruiser on 18–27 May 1941, during World War II. This operation to block Allied shipping to the United Kingdom culminated w ...

. In a repetition of ''Berlin'', Lütjens was required to break out of their naval base in occupied Poland

' (Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 October 2 ...

, sail via occupied Norway

The occupation of Norway by Nazi Germany during the Second World War began on 9 April 1940 after Operation Weserübung. Conventional armed resistance to the German invasion ended on 10 June 1940, and Nazi Germany controlled Norway until the ...

, and attack merchant shipping. The operation went awry and the task force was soon spotted and engaged near Iceland. In the ensuing Battle of the Denmark Strait

The Battle of the Denmark Strait was a naval engagement in the Second World War, which took place on 24 May 1941 between ships of the Royal Navy and the ''Kriegsmarine''. The British battleship and the battlecruiser fought the German battlesh ...

, was sunk and three other British warships were forced to retreat. The two German ships then separated. Three days later, on 27 May, Lütjens and most of the ship's crew lost their lives when ''Bismarck'' was caught and sunk.

In 1955 the Federal Republic of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated between ...

was remilitarised and entered NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

. The ''Bundesmarine

The German Navy (, ) is the navy of Germany and part of the unified ''Bundeswehr'' (Federal Defense), the German Armed Forces. The German Navy was originally known as the ''Bundesmarine'' (Federal Navy) from 1956 to 1995, when ''Deutsche Mari ...

'' was established the following year. In 1967 this organisation recognised Lütjens and his service by naming the destroyer after him.

Early life

Johann Günther Lütjens was born inWiesbaden

Wiesbaden () is a city in central western Germany and the capital of the state of Hesse. , it had 290,955 inhabitants, plus approximately 21,000 United States citizens (mostly associated with the United States Army). The Wiesbaden urban area ...

in Hesse-Nassau

The Province of Hesse-Nassau () was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1868 to 1918, then a province of the Free State of Prussia until 1944.

Hesse-Nassau was created as a consequence of the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 by combining the p ...

, a province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''Roman province, provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire ...

of the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Re ...

, on 25 May 1889. He was the son of merchant Johannes Lütjens and his wife Luise, née Volz. Growing up in Freiburg im Breisgau

Freiburg im Breisgau (; abbreviated as Freiburg i. Br. or Freiburg i. B.; Low Alemannic German, Low Alemannic: ''Friburg im Brisgau''), commonly referred to as Freiburg, is an independent city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. With a population o ...

, he graduated from the Berthold

Berthold or Berchtold is a Germanic given name and surname. It is derived from two elements, ''berht'' meaning "bright" and ''wald'' meaning "(to) rule". It may refer to:

*Bertholdt Hoover, a fictional List_of_Attack_on_Titan_characters, character ...

- Gymnasium with his diploma (''Abitur

''Abitur'' (), often shortened colloquially to ''Abi'', is a qualification granted at the end of secondary education in Germany. It is conferred on students who pass their final exams at the end of ISCED 3, usually after twelve or thirteen year ...

'') aged seventeen.

He entered the Imperial German Navy (''

He entered the Imperial German Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine

{{italic title

The adjective ''kaiserlich'' means "imperial" and was used in the German-speaking countries to refer to those institutions and establishments over which the ''Kaiser'' ("emperor") had immediate personal power of control.

The term wa ...

'') as a ''Seekadett

''Seekadett'' (short SKad or SK; ,Langenscheidt´s Encyclopaedic Dictionary of the English and German language: „Der Große Muret-Sander“, Part II German-English, Second Volume L–Z, 8th edition 1999, ; p. 1.381 ) is a military rank of the B ...

'' (midshipman) on 3 April 1907 at the German Imperial Naval Academy

The German Imperial Naval Academy (''Marineakademie'') at Kiel, Germany, was the higher education institution of the Imperial German Navy, ''Kaiserliche Marine'', where naval officers were prepared for service in the higher levels of command, ...

in Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

, where he received his initial infantry training. He spent his initial year on (9 May 1907 – 1 April 1908) for his practical training on board and his first world cruise, before attending an officers course at the German Imperial Naval Academy

The German Imperial Naval Academy (''Marineakademie'') at Kiel, Germany, was the higher education institution of the Imperial German Navy, ''Kaiserliche Marine'', where naval officers were prepared for service in the higher levels of command, ...

in Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

. His comrades nicknamed him "Pee Ontgens" after a character from the book ''Das Meer'' (The Sea) by Bernhard Kellermann, which was one of his favourite books. Lütjens graduated 20th of 160 cadets from his "Crew 1907" (the incoming class of 1907), and was thereafter promoted to ''Fähnrich zur See

''Fähnrich zur See'' (Fähnr zS or FRZS) designates in the German Navy of the Bundeswehr a military person or member of the armed forces with the second highest Officer Aspirant (OA – german: Offizieranwärter) rank. According to the salary ...

'' (ensign) on 21 April 1908. Starting on 1 April 1909, he underwent naval artillery

Naval artillery is artillery mounted on a warship, originally used only for naval warfare and then subsequently used for naval gunfire support, shore bombardment and anti-aircraft roles. The term generally refers to tube-launched projectile-firi ...

training at the Naval Artillery SchoolNaval Artillery School—''Schiffsartillerieschule'' in Kiel-Wik and then participated in a torpedo course on board on 1 July 1909.

Lütjens then attended another infantry course with the 2nd Sea-Battalion before boarding on 1 October 1909.2nd Sea-Battalion —'' II. See-Bataillon'' After receiving his commission as ''Leutnant zur See

''Leutnant zur See'' (''Lt zS'' or ''LZS'') is the lowest officer rank in the German Navy. It is grouped as OF1 in Ranks and insignia of officers of NATO Navies, NATO, equivalent to an Ensign (rank), Ensign in the United States Navy, and an Acti ...

'' (second lieutenant) on 28 September 1910, he served on board (26 September 1910 – 1 April 1911), a harbour ship, and then (1 April 1911 – 1 April 1913). He then returned to the ''König Wilhelm'' (1 April 1913 – 1 October 1913), where he served as an instructor of cabin boy

''Cabin Boy'' is a 1994 American fantasy comedy film, directed by Adam Resnick and co-produced by Tim Burton, which starred comedian Chris Elliott. Elliott co-wrote the film with Resnick. Both Elliott and Resnick worked for '' Late Night with Dav ...

s and later as an instructor of cadets. ''König Wilhelm'' at the time was a barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for sai ...

based in Kiel and used as a training vessel for naval cadets. He then completed two further world cruises on ''Hansa''. Following these assignments, he was promoted to ''Oberleutnant zur See

''Oberleutnant zur See'' (''OLt zS'' or ''OLZS'' in the German Navy, ''Oblt.z.S.'' in the '' Kriegsmarine'') is traditionally the highest rank of Lieutenant in the German Navy. It is grouped as OF-1 in NATO.

The rank was introduced in the Imp ...

'' (sub-lieutenant) on 27 September 1913.

Lütjens' next assignment was with the 4th Torpedo-Boat-Flotilla, where he served as a watch officer

Watchkeeping or watchstanding is the assignment of sailors to specific roles on a ship to operate it continuously. These assignments, also known at sea as ''watches'', are constantly active as they are considered essential to the safe operation o ...

.4th Torpedo-Boat-Flotilla—''4. Torpedobootflottille'' On 1 October 1913, he was appointed company officer with the I. Torpedodivision, and served as a watch officer on torpedo boat ''G-169'' of the 2nd Torpedo-Boat-Demi-Flotilla from 1 November.2nd Torpedo-Boat-Demi-Flotilla—''II. Torpedoboot-Halbflottille'' On 24 December 1913, he returned to his position as company officer with the I. Torpedodivision, before becoming a watch officer on ''G-172'' of the 2nd Torpedo-Boat-Demi-Flotilla on 15 March 1914.

World War I

Shortly after the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Lütjens was transferred to the Harbour Flotilla of the Jade Bight

The Jade Bight (or ''Jade Bay''; german: Jadebusen) is a bight or bay on the North Sea coast of Germany. It was formerly known simply as ''Jade'' or ''Jahde''. Because of the very low input of freshwater, it is classified as a bay rather than an ...

Harbor Flotilla of the Jade Bight—''Hafenflottille der Jade'' on 1 August 1914, followed shortly by his first command: torpedo boat of the 6th Torpedo-Boat-Demi-Flotilla on 4 September 1914. On 7 December 1914, he returned to the I. Torpedodivision, before attending a minesweeping

Minesweeping is the practice of the removal of explosive naval mines, usually by a specially designed ship called a minesweeper using various measures to either capture or detonate the mines, but sometimes also with an aircraft made for that ...

course on 2 January 1915. After completion of this course, he was sent back again to the I. Torpdedivsion, where he took command of the training torpedo boat on 16 January. He served in this position until 14 March 1915, when he was posted back to the I. Torpedodivsion. On 5 May, he was transferred to the Torpedo-Boat-Flotilla "Flandern", serving as commander of torpedo boats ''A-5'' and ''A-20''.Torpedo-Boat-Flotilla "Flandern"—''Torpedobootsflottille'' "Flander" He was appointed chief of the A-Demi-Flotilla in the II. Torpedo-Boat-Flotilla "Flandern" in February 1916, and at the same time commanded torpedo boat .A-Demi-Flotilla—A-''Halbflottille'' He held this position until the end of World War I on 11 November 1918, when he returned to Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

and Kiel.

Lütjens had been promoted to ''Kapitänleutnant

''Kapitänleutnant'', short: KptLt/in lists: KL, ( en, captain lieutenant) is an officer grade of the captains' military hierarchy group () of the German Bundeswehr. The rank is rated OF-2 in NATO, and equivalent to Hauptmann in the Heer and ...

'' (captain lieutenant) on 24 May 1917 during this assignment. As commander of torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

s along the Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

coast, he led raids against Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.Knight's Cross of the House Order of Hohenzollern with Swords and the

After the war, Lütjens served as head of the

After the war, Lütjens served as head of the

On 30 January 1933, the

On 30 January 1933, the

In April 1940, during the invasion of Denmark and Norway (

In April 1940, during the invasion of Denmark and Norway (

In July 1940 Hitler ordered the preparation for

In July 1940 Hitler ordered the preparation for

Lütjens now had the operational initiative. He had a choice of two potential killing-grounds. To the north lay the HX and SC convoys which sailed between Britain and

Lütjens now had the operational initiative. He had a choice of two potential killing-grounds. To the north lay the HX and SC convoys which sailed between Britain and

Plans were then made for Lütjens to command

Plans were then made for Lütjens to command

On 18 May the operation began. Lütjens had informed Lindemann and Brinkmann on 18 May that he intended to sail for the arctic and refuel at sea. Three days later, in Norwegian waters, Lütjens ordered a fuel stop in a

On 18 May the operation began. Lütjens had informed Lindemann and Brinkmann on 18 May that he intended to sail for the arctic and refuel at sea. Three days later, in Norwegian waters, Lütjens ordered a fuel stop in a

In the early hours of 24 May 1941, ''Prinz Eugen''s hydrophones detected two large ships approaching. Vice Admiral

In the early hours of 24 May 1941, ''Prinz Eugen''s hydrophones detected two large ships approaching. Vice Admiral

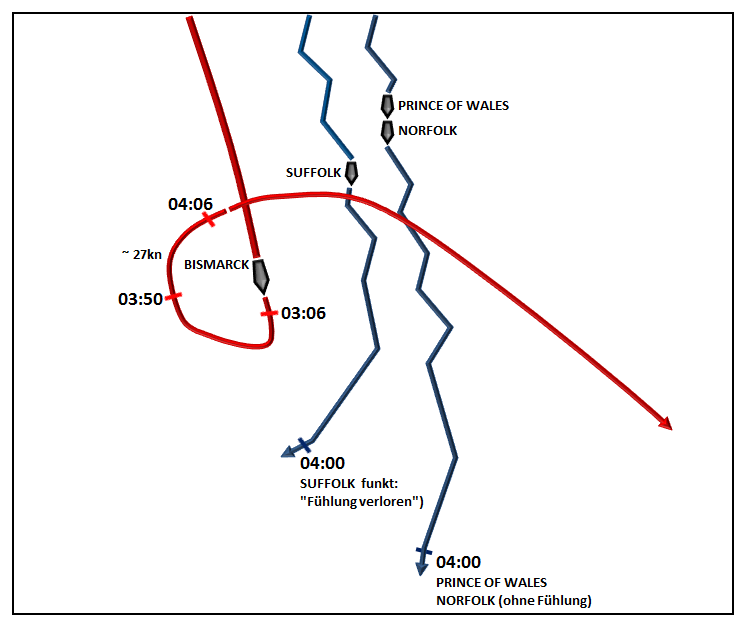

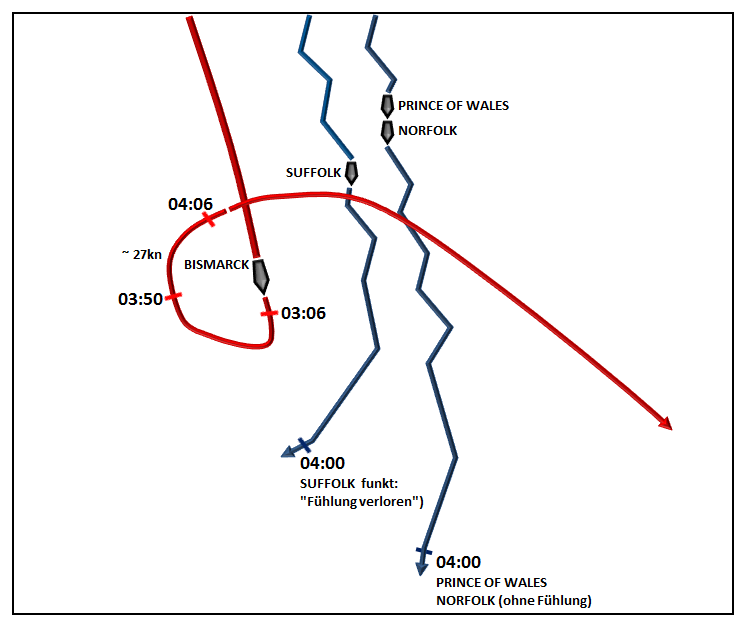

Meanwhile, Lütjens took stock of his predicament. Firstly, he believed that he was shadowed by a force of ships with superior radar. Secondly, the element of surprise had been lost. Thirdly, the battleship was running low of fuel; his decision not to refuel in Norway or the

Meanwhile, Lütjens took stock of his predicament. Firstly, he believed that he was shadowed by a force of ships with superior radar. Secondly, the element of surprise had been lost. Thirdly, the battleship was running low of fuel; his decision not to refuel in Norway or the

"Bismarck – Portrait of the Men Involved – Günther Lütjens."

''bismarck-class.dk'', 2009. Retrieved: 1 December 2013.

The ''

The ''

/ref> In his christening speech the then secretary of state at the

File:Lütjens Konteradmiral.jpg, Promotion to Konteradmiral

File:Lütjens Vizeadmiral.jpg, Promotion to Vizeadmiral

File:Lütjens Admiral.jpg, Promotion to Admiral

File:Lütjens Ritterkreuz.jpg, Temporary certificate for the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

File:Funknachricht Lütjens.jpg, Last message to Hitler

Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia est ...

(1914) 2nd and 1st Class, among other decorations and awards.

Inter-war period

Warnemünde

(, literally ''Mouth of the Warnow'') is a seaside resort and a district of the city of Rostock in Mecklenburg, Germany. It is located on the Baltic Sea and, as the name implies, at the estuary of the river Warnow. is one of the world's busie ...

(1 December 1918 – 24 January 1919 and 8 February 1919 – 10 March 1919) and Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the stat ...

(24 January 1919 – 8 February 1919 and 8 July 1919 – 15 September 1919) Sea Transportation Agency.Sea Transportation Agency—''Seetransportstelle'' He was ordered to the German Imperial Naval Office

The Imperial Naval Office (german: Reichsmarineamt) was a government agency of the German Empire. It was established in April 1889, when the German Imperial Admiralty was abolished and its duties divided among three new entities: the Imperial Na ...

on 10 March 1919 before again serving with the Sea Transportation Agency in Lübeck on 8 July 1919.German Imperial Naval Office—''Reichsmarineamt''

As a result of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, which was signed on 28 June 1919, the German Navy was downsized to 15,000 men, including 1,500 officers, while the German Imperial Navy was renamed the ''Reichsmarine

The ''Reichsmarine'' ( en, Realm Navy) was the name of the German Navy during the Weimar Republic and first two years of Nazi Germany. It was the naval branch of the ''Reichswehr'', existing from 1919 to 1935. In 1935, it became known as the ''K ...

'' in the era of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

. On 15 September 1919 his posting with the Sea Transportation Agency ended and he was posted to the Coastal Defence Department III and later IV in Cuxhaven-Lehe as a company leader.Coastal Defence Department—''Küstenwehrabteilung''company leader—''Kompanieführer'' As of 1 January 1921 he was also subordinated to the Staff of the North Sea. Lütjens was posted to the Fleet Department of the Naval Command on 7 June 1921.Naval Command—''Marineleitung'' His commanding officer here was Admiral Paul Behncke

Paul Behncke (13 August 1869 – 4 January 1937) was a German admiral during the First World War, most notable for his command of the III Battle Squadron of the German High Seas Fleet during the Battle of Jutland.

Naval career

He was born in Lü ...

. Here Lütjens served as the head of the Fleet Department until the end of September 1923.head of department—''Dezernent'' In this position, Lütjens dealt with strategic and naval policy issues. This included the observation and analysis of the Washington Naval Conference

The Washington Naval Conference was a disarmament conference called by the United States and held in Washington, DC from November 12, 1921 to February 6, 1922. It was conducted outside the auspices of the League of Nations. It was attended by nine ...

and its disarmament agreements. On 4 October 1923 he returned to the torpedo force, taking command of the 3rd Torpedo-Boat-Demi-Flotilla.

On 26 September 1925 he became 1st adjutant of the Marinestation der Nordsee

The Marinestation der Nordsee (North Sea Naval Station) of the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy) at Wilhelmshaven came out of the efforts of the navy of the North German Confederation. The land was obtained for the Confederation from the ...

. He served in this position until 2 October 1929. Here he was promoted to ''Korvettenkapitän

() is the lowest ranking senior officer in a number of Germanic-speaking navies.

Austro-Hungary

Belgium

Germany

Korvettenkapitän, short: KKpt/in lists: KK, () is the lowest senior officer rank () in the German Navy.

Address

The off ...

'' (Corvette Captain) on 1 April 1926. This assignment was interrupted for a posting to the sailing yacht

A yacht is a sailing or power vessel used for pleasure, cruising, or racing. There is no standard definition, though the term generally applies to vessels with a cabin intended for overnight use. To be termed a , as opposed to a , such a pleasu ...

''Asta'' (1–31 August 1926) and again for a short torpedo course for staff officers at the torpedo school in Mürwik (5–9 December 1927). On 21 April 1928 he participated in a training exercise on , then under the command of Alfred Saalwächter

Alfred Saalwächter (10 January 1883 – 6 December 1945) was a high-ranking German U-boat commander during World War I and General Admiral during World War II.

Early life

Saalwächter was born in Neusalz an der Oder, Prussian Silesia, as the ...

, which ended on 28 April. From 14 to 18 August 1928 he boarded ''Schlesien'' again for a torpedo firing exercise. On 3 October 1929 Lütjens took command as head of the 1st Torpedo-Boat-Flotilla in Swinemünde, present-day Świnoujście, which he commanded until 17 September 1931. This posting was interrupted by a number of training courses, the first for staff officers (9–12 January 1930), a torpedo course (3–8 February 1930), for commanders and staff officers in leadership positions (2–7 February 1931) and lastly a navigation course (16–21 February 1931).

Lütjens was called by Admiral Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder (24 April 1876 – 6 November 1960) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II. Raeder attained the highest possible naval rank, that of grand admiral, in 1939, becoming the f ...

into the Naval Command of the Ministry of the Reichswehr

The Ministry of the Reichswehr or Reich Ministry of Defence (german: Reichswehrministerium) was the defence ministry of the Weimar Republic and the early Third Reich. The 1919 Weimar Constitution provided for a unified, national ministry of defen ...

on 17 September 1931.Ministry of the Reichswehr—''Reichswehrministerium'' Shortly after he was assigned to the Ministry of the Reichswehr he was promoted to ''Fregattenkapitän

Fregattenkapitän, short: FKpt / in lists: FK, () is the middle field officer rank () in the German Navy.

Address

In line with ZDv 10/8, the official manner of formally addressing military personnel holding the rank of ''Fregattenkapitän'' ...

'' (Frigate Captain) on 1 October 1931. In the Naval Command Lütjens first served as Department Head of the Fleet- and Naval Officer Personnel Department.Fleet- and Naval Officer Personnel Department—''Flotten- und Marineoffizierspersonalabteilung'' On 26 September 1932 he was appointed chief of this department, a function that Lütjens held until the mid-September 1934. Here he advanced in rank to ''Kapitän zur See

Captain is the name most often given in English-speaking navies to the rank corresponding to command of the largest ships. The rank is equal to the army rank of colonel and air force rank of group captain.

Equivalent ranks worldwide include ...

'' (Captain at Sea) on 1 July 1933.

National Socialism

On 30 January 1933, the

On 30 January 1933, the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

, under the leadership of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, came to power in Germany, and began to rearm the navy. In 1935, the ''Reichsmarine'' was renamed the ''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

''.

On 16 September 1933, Lütjens received command of and sailed around the world for good will visits. Burkard Freiherr von Müllenheim-Rechberg

Richard Alexander Conrad Bernhard Burkard von Müllenheim-Rechberg (Spandau, 25 June 1910 — Herrsching am Ammersee, 1 June 2003) was a German diplomat and author. After his career as a naval officer in the '' Kriegsmarine'', he entered the di ...

, the most senior officer to survive ''Bismarck''s last battle, was an officer cadet on ''Karlsruhe'' at the time of Lütjens' command. Lütjens took ''Karlsruhe'' on its fourth training cruise. ''Karlsruhe'' left Kiel on 22 October 1934. The ship sailed via Skagen

Skagen () is Denmark's northernmost town, on the east coast of the Skagen Odde peninsula in the far north of Jutland, part of Frederikshavn Municipality in Nordjylland, north of Frederikshavn and northeast of Aalborg. The Port of Skagen is ...

, the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

and Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

on the east coast of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

, passed the Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

, up the west coast of South, Middle and North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

to Vancouver. At Callao

Callao () is a Peruvian seaside city and Regions of Peru, region on the Pacific Ocean in the Lima metropolitan area. Callao is Peru's chief seaport and home to its main airport, Jorge Chávez International Airport. Callao municipality consists o ...

(25 January – 6 February 1935) they joined in the 400-year celebration of Peru. ''Karlsruhe'' returned to Kiel on 15 June 1935, travelling through the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

to Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 in ...

, Charlestown and Vigo, Spain

Vigo ( , , , ) is a city and municipality in the province of Pontevedra, within the autonomous community of Galicia, Spain. Located in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, it sits on the southern shore of an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean, the ...

.

Lütjens first met Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (sometimes spelled Doenitz; ; 16 September 1891 24 December 1980) was a German admiral who briefly succeeded Adolf Hitler as head of state in May 1945, holding the position until the dissolution of the Flensburg Government follo ...

, future Commander-in-Chief of the ''Kriegsmarine'' in Vigo in June 1935. At that point, Dönitz had been entrusted with the rebuilding of the U-boat Arm

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the an ...

but had spent the summer at sea commanding . After arriving at port, he met with Raeder. Raeder informed Dönitz that:

Lütjens is to become chief of the Officer Personnel Branch at Naval Headquarters with the task of forming an officer Corps for the new Navy we are about to build.In 1936, Lütjens was appointed Chief of the Personnel Office of the ''Kriegsmarine'', an office which he had served in 1932–34, and in 1937, he became ''Führer der Torpedoboote'' (Chief of Torpedo Boats), with as his flagship, and was promoted to ''

Konteradmiral

''Konteradmiral'', abbreviated KAdm or KADM, is the second lowest naval flag officer rank in the German Navy. It is equivalent to '' Generalmajor'' in the '' Heer'' and ''Luftwaffe'' or to '' Admiralstabsarzt'' and ''Generalstabsarzt'' in the '' ...

'' in October 1937. While in command of personnel department he did nothing to enforce the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of th ...

on race in the ''Kriegsmarine''. In November 1938, Lütjens was one of only three flag officers, including Dönitz, who protested in writing to Raeder, Commander-in-Chief of the navy, against the anti-Jewish ''Kristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation from ...

'' pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s.

His successor at the ''Marinepersonalamt'' Conrad Patzig, described Lütjens as a dedicated naval officer who put his service to the nation ahead of the ruling party. He also described him as a difficult man to know. Austere, rather forbidding, he said little and when he did, confined his remarks to the essentials. Patzig said of him "one of the ablest officers in the service, very logical and shrewd, incorruptible in his opinions and an engaging personality when you got to know him." Few did. Lütjens's dedication to his officer principles meant he did not marry until he was 40, adhering to a code that an officer would marry only when he was able to support a wife.

World War II

At the outbreak ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Lütjens was Commander of Scouting Forces—''Befehlshaber der Aufklärungsstreitkräfte'' (B.d.A.)—made up of German destroyers, torpedo boats and cruisers. On 1 September 1939 Germany invaded Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

and two days later, Lütjens sailing aboard his flagship, Z1 ''Leberecht Maass'' and Z9 ''Wolfgang Zenker'' took part in an attack on the Polish ships and in Gdynia

Gdynia ( ; ; german: Gdingen (currently), (1939–1945); csb, Gdiniô, , , ) is a city in northern Poland and a seaport on the Baltic Sea coast. With a population of 243,918, it is the List of cities in Poland, 12th-largest city in Poland and ...

harbour. Lütjens attacked from a range of 14,000 yards south-east of the harbour. The Poles replied effectively and forced the German destroyers to make evasive manoeuvres and to lay a smoke screen

A smoke screen is smoke released to mask the movement or location of military units such as infantry, tanks, aircraft, or ships.

Smoke screens are commonly deployed either by a canister (such as a grenade) or generated by a vehicle (such as ...

to throw off the aim of the Polish gunners. ''Leberecht Maass'' was hit in the superstructure by a shell from the coast defence battery

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

at Hel that killed four crewmen and wounded another four men. Lütjens ordered the action broken off 40 minutes later as the German fire was ineffective. Lütjens ordered the group to Pillau

Baltiysk (russian: Балти́йск; german: Pillau; Old Prussian: ''Pillawa''; pl, Piława; lt, Piliava; Yiddish: פּילאַווע, ''Pilave'') is a seaport town and the administrative center of Baltiysky District in Kaliningrad Oblast, Ru ...

to refuel and the ''Leberecht Maas'' sailed to Swinemünde for repairs.

On 17 October 1939 Lütjens led a raiding sortie into the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

. On board his flagship Z21 ''Wilhelm Heidkamp'', he led six destroyers laden with naval mines. His own ship did not carry any mines and acted as cover. They reached the Humber Estuary undetected and departed unseen. Within days shipping losses began occurring among British transports in the area. Lütjens did not repeat the operation. He was promoted to vice admiral and moved with his staff to the cruiser ''Nürnberg''.

Operation Weserübung

In April 1940, during the invasion of Denmark and Norway (

In April 1940, during the invasion of Denmark and Norway (Operation Weserübung

Operation Weserübung (german: Unternehmen Weserübung , , 9 April – 10 June 1940) was Germany's assault on Denmark and Norway during the Second World War and the opening operation of the Norwegian Campaign.

In the early morning of 9 Ap ...

), he served as ''Vizeadmiral

(abbreviated VAdm) is a senior naval flag officer rank in several German-speaking countries, equivalent to Vice admiral.

Austria-Hungary

In the Austro-Hungarian Navy there were the flag-officer ranks ''Kontreadmiral'' (also spelled ''Kont ...

'' (vice admiral), commanding the distant cover forces in the North Sea—which consisted of and . His superior, ''Vizeadmiral'' Wilhelm Marschall

Wilhelm Marschall (30 September 1886 – 20 March 1976) was a German admiral during World War II. He was also a recipient of the ''Pour le Mérite'' which he received as commander of the German U-boat during World War I. The ''Pour le Mérite'' ...

, had fallen ill just before the operation, so he assumed command of the Narvik

( se, Áhkanjárga) is the third-largest municipality in Nordland county, Norway, by population. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Narvik. Some of the notable villages in the municipality include Ankenesstranda, Ball ...

and Trondheim

Trondheim ( , , ; sma, Tråante), historically Kaupangen, Nidaros and Trondhjem (), is a city and municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. As of 2020, it had a population of 205,332, was the third most populous municipality in Norway, and ...

landings.

Lütjens was to lead ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'', with his flag in the latter, on escort operation for a force of 10 destroyers commanded by ''Führer der Zerstörer'' (Leader of Destroyers) Friedrich Bonte __NOTOC__

Friedrich Bonte (19 October 1896 – 10 April 1940) was the German naval officer commanding the destroyer flotilla that transported invasion troops to Narvik during the German invasion of Norway (Operation Weserübung) in April 1940.

Bon ...

. The fleet was laden with soldiers belonging to the ''3. Gebirgs-Division'' under the command of Eduard Dietl

Eduard Wohlrat Christian Dietl (21 July 1890 – 23 June 1944) was a German general during World War II who commanded the 20th Mountain Army. He was magnanimously awarded of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords of Na ...

. The division was to seize Narvik. Lütjens briefed his officers aboard ''Gneisenau'' on 6 April in the presence of Raeder. Lütjens had his doubts about the wisdom of the entire operation but he showed no sign of his feelings to his subordinates. Lütjens hoped for bad weather to shield the fleet from Allied aircraft. The skies were clear and the ships were twice attacked by RAF Coastal Command

RAF Coastal Command was a formation within the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was founded in 1936, when the RAF was restructured into Fighter, Bomber and Coastal Commands and played an important role during the Second World War. Maritime Aviation ...

bombers without result. The British airmen reported their position and surprise was now gone. Nevertheless, Lütjens remained on schedule and delivered the force to Narvik. On two occasions a sailor was swept overboard but Lütjens' operations officer, Heinrich Gerlach, noted: "No rescue attempts were made. On no account was there to be any interruption of the time schedule."

Lütjens' mission then was to draw British units away from Narvik and facilitate the landings there and prevent the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

from attacking the destroyers and landing craft. During the landing phase, his forces were approached by a Royal Navy task-force led by the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

. The British ship engaged at 05:05 and Lütjens was forced to fight an inconclusive battle with ''Renown''. Lütjens succeeded in extracting the German vessels without incurring major battle damage. He viewed his operation as a success. Lütjens nearly changed his mind during the battle, believing a pitched fight may bring relief to the German destroyer force at Narvik—a force which he had effectively been forced to abandon in the face of enemy sea superiority. But the prospect of running into , now known by German naval intelligence to be in the vicinity, was too much of a risk. In the resultant Battles of Narvik

The Battles of Narvik were fought from 9 April to 8 June 1940, as a naval battle in the Ofotfjord and as a land battle in the mountains surrounding the north Norwegian town of Narvik, as part of the Norwegian Campaign of the Second World War.

...

10 German destroyers were sunk and the campaign for the port lasted until June. Bonte was killed when his command ship, ''Wilhelm Heidkamp'' exploded.

It may have been possible for him to turn on and sink ''Renown'' by attacking from different directions, using ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'', but the accompanying British destroyers were well placed to join the fight had he done so. His Commander-in-Chief, Raeder, endorsed his actions which would have placed him against a clear eastern horizon as opposed to an enemy that was positioned against a darkened western horizon. Action at that time would have given the enemy a clearer silhouette to aim at while obscuring the British ships somewhat. Moreover, if either German ship had been immobilised by ''Renown'' they would have been vulnerable to a torpedo attack by the British destroyers. Under those circumstances, Raeder felt the British would have had a tactical advantage. Lütjens later rendezvoused with the cruiser and reached Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsha ...

on 12 April, having avoided a major fleet action.

Lütjens was indirectly involved in another battle. The Trondheim force was led by the heavy cruiser ''Admiral Hipper'' who detached the German destroyers and to search for a man that had been washed over board. In the heavy fog they ran into . ''Glowworm'' outmatched the lighter German vessels and they disengaged and called for help. Lütjens ordered ''Hipper'' to assist. The heavy cruiser sank the ''Glowworm'', but not before the British ship had rammed her larger assailant and caused her considerable damage. When Lütjens stepped ashore at Wilhelmshaven, his decision to abandon Bonte's destroyer group at Narvik weighed heavily on his mind. In the wake of Lütjens return, he learned Marschall had recovered to assume command.

Commander of the fleet

In June and July 1940, he became Commander of Battleships and the third ''Flottenchef'' (Fleet Commander) of the ''Kriegsmarine'', a position comparable to the British Commander-in-Chief of theHome Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the First ...

. His predecessor—''Vizeadmiral'' Wilhelm Marschall—had had repeated differences with Raeder over the extent the ''Flottenchef'' should be bound by orders while operating at sea. Marschall led ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'' to intercept Allied naval forces withdrawing from Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

against orders. On 8 June 1940 he engaged and sank the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

and her escorting destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s and . During the battle ''Scharnhorst'' was heavily damaged by a torpedo. Marschall was dismissed by Raeder because the Commander-in-Chief of the ''Kriegsmarine'' deemed the episode unacceptable. Raeder viewed the sinkings as "target practice" and the damage to ''Scharnhorst'', and consequently ''Gneisenau'', offset this victory in his view.

Ten days later Lütjens was given command of the fleet on a temporary basis. Raeder regarded Lütjens as a sound tactician, excellent staff officer and a leader with all-important operational and battle experience. After the war Raeder was candid about his decision to elevate Lütjens through the chain of command. Raeder said of his progression, "He had also experience in staff work, and as my Chief of Personnel he had won by special confidence in years of close association." Raeder expressed his confidence that Lütjens displayed wise judgment and was unlikely to act rashly. When at sea, he allowed him to take command of the situation and make operational decisions at his own discretion. Although described as reserved and unapproachable toward subordinates, he was held to be "of manifest integrity and reliability." Hitler expressed his gratitude to Lütjens for "preparing and leading the Navy into action", and awarded him the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (german: Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes), or simply the Knight's Cross (), and its variants, were the highest awards in the military and paramilitary forces of Nazi Germany during World War II.

The Knight' ...

() on 14 June 1940.

''Scharnhorst'' had been forced to make for Trondheim in the aftermath of the action for emergency repairs. Flying his flag in ''Gneisenau'', Lütjens took command of his first voyage as ''Flottenchef'' aboard a capital ship. On 20 June 1940 he sailed in company with ''Admiral Hipper'', toward the North Sea in the hope of diverting attention from ''Scharnhorst'' while it made the perilous trek from Norway to Germany. The operation succeeded, but ''Gneisenau'' was torpedoed by the submarine and severely damaged.

Operation Sea Lion

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (german: Unternehmen Seelöwe), was Nazi Germany's code name for the plan for an invasion of the United Kingdom during the Battle of Britain in the Second World War. Following the Battle o ...

, the invasion of the United Kingdom after the victory in France. While the ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' engaged the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF) in what became known as the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

to clear the skies the German naval command began planning for an assault in southern England. Lütjens, as fleet commander, was responsible for carrying out sea operations based upon the strategies devised by his superior Saalwächter, who commanded Naval Group West. Saalwächter answered to the commander-in-chief, Raeder.

Lütjens was to be heavily involved in the planning of the sea landings. The navy wished to land on a narrow front because of its limited resources and Lütjens planned accordingly. He established himself in the fashionable market-town of Trouville near Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very cl ...

. The enormous logistical effort that required the navy to move personnel command structures and personnel to France meant that his command post did not become fully operational until August 1940. Friedrich Ruge was appointed to the mine command by Lütjens with the task of clearing British naval minefields and laying German mine zones to impede the operations of the Royal Navy. Meanwhile, Lütjens scoured the continent for the 1,800 river barges, 500 tugs, 150 steamships and 1,200 motor boats deemed necessary for the operation. Some 24,000 men were seconded from other services and trained as landing craft crewman.

Lütjens was handicapped by the lack of firepower in the German navy. He authorised Ruge to organise the landings. The Advanced Detachments (''Vorausabteilungen'') were to storm the beach in battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

-strength. The following craft would clear mines allowing for artillery coasters and tugs carrying the Panzer

This article deals with the tanks (german: panzer) serving in the German Army (''Deutsches Heer'') throughout history, such as the World War I tanks of the Imperial German Army, the interwar and World War II tanks of the Nazi German Wehrmacht, ...

units to follow unhindered. The smaller motor boats would unload engineers to clear obstacles and act as shuttle boats between the larger vessels and the beach. They would rush to and fro delivering army units to land in order to expand the beachhead and allow the flotilla to land its full complement. Lütjens recommended using the old battleships ''Schlesien'' and as fire support to protect the crossing. Lütjens favoured beaching the ships on the Varne Bank

The Varne Bank or Varne Shoal is a long sand bank in the Strait of Dover, lying southwest of Dover in Kent, England. With the Lobourg Channel running along it, the Varne bank lies immediately south-west of the deepest point in the strait of Do ...

to act as a gun-fire platform. He thought they could best act as strong points to deny passage through the Strait of Dover

The Strait of Dover or Dover Strait (french: Pas de Calais - ''Strait of Calais''), is the strait at the narrowest part of the English Channel, marking the boundary between the Channel and the North Sea, separating Great Britain from continent ...

to the British. Raeder agreed but the plan was rubbished by technical experts who argued the old ships were too prone to capsizing and their stationary posture was too vulnerable and their armament too weak to do the job effectively.

Lütjens continued planning preparations as the Battle of Britain raged. By September he had completed plans to land the entire German 16th Army under Ernst Busch between Deal

A deal, or deals may refer to:

Places United States

* Deal, New Jersey, a borough

* Deal, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* Deal Lake, New Jersey

Elsewhere

* Deal Island (Tasmania), Australia

* Deal, Kent, a town in England

* Deal, ...

and Hastings

Hastings () is a large seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east to the county town of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to the north-west ...

—the site of the last successful invasion of England in 1066—and the German 9th Army between Hastings and Worthing

Worthing () is a seaside town in West Sussex, England, at the foot of the South Downs, west of Brighton, and east of Chichester. With a population of 111,400 and an area of , the borough is the second largest component of the Brighton and Hov ...

to the west. Lütjens' opinion on the chances of success are not known. The battles in Norway had left him without any major capital ship. In the event, Lütjens was never tested. The air battle over Britain was lost and by the end of 1940 plans for an invasion were postponed as Hitler turned eastward for a campaign against the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. German naval strategy now turned to thoughts of siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

and destroying Britain's shipping lanes which supplied the country from overseas and in particular North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

.

Operation Berlin

''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'' were readied for action again by the winter. Their task now was to engage Alliedmerchant vessel

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are us ...

s bringing war materials to Britain. As fleet commander, it would be Lütjens' first operation in the Battle of the Atlantic. It was named Operation Berlin. On 28 December 1940, ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau''—on which Admiral Lütjens had raised his flag—left Germany for an Atlantic raid. However, due to weather, Lütjens ordered a return to port: ''Gneisenau'' to Kiel and ''Scharnhorst'' to Gdynia. While repairs were carried out Navy Group West emphasised to him that his primary targets were enemy merchant vessels. Lütjens reiterated his standing orders to his captains: "our job is to put as many as possible under the water".

On 22 January 1941, the renewed mission was delayed for several days owing to the sighting of British ships near the Norwegian coast and the inability of submarine chasers and destroyers to escort them to the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

. Lütjens chose to pass between Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

and the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

. Unbeknownst to Lütjens, his ships had been spotted sailing past Zealand

Zealand ( da, Sjælland ) at 7,031 km2 is the largest and most populous island in Denmark proper (thus excluding Greenland and Disko Island, which are larger in size). Zealand had a population of 2,319,705 on 1 January 2020.

It is the 1 ...

, Denmark, by British agents. British Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet, Admiral John Tovey

Admiral of the Fleet John Cronyn Tovey, 1st Baron Tovey, (7 March 1885 – 12 January 1971), sometimes known as Jack Tovey, was a Royal Navy officer. During the First World War he commanded the destroyer at the Battle of Jutland and then co ...

was alerted and dispatched three battleships, eight cruisers, and 11 destroyers to hunt for the German ships accordingly, hoping to intercept the Germans off southern Iceland. The cruiser briefly sighted the German ships on 28 January as Lütjens prepared to break through the Iceland-Faroe gap, and reported their position. The German admiral quickly decided to retire northbound with the intention of passing through the Denmark Strait

The Denmark Strait () or Greenland Strait ( , 'Greenland Sound') is an oceanic strait between Greenland to its northwest and Iceland to its southeast. The Norwegian island of Jan Mayen lies northeast of the strait.

Geography

The strait connect ...

. On 30 January Lütjens decided to refuel from the tanker ''Thorn'' off Jan Mayen

Jan Mayen () is a Norwegian volcanic island in the Arctic Ocean with no permanent population. It is long (southwest-northeast) and in area, partly covered by glaciers (an area of around the Beerenberg volcano). It has two parts: larger nort ...

island before attempting this breakout route. After refueling, Lütjens sailed, and on 4 February, slipped into the Atlantic. Fortunately for Lütjens, Tovey dismissed the sighting by ''Naiad'' as an illusion

An illusion is a distortion of the senses, which can reveal how the mind normally organizes and interprets sensory stimulation. Although illusions distort the human perception of reality, they are generally shared by most people.

Illusions may o ...

, and returned to port.

Free in the Atlantic

Lütjens now had the operational initiative. He had a choice of two potential killing-grounds. To the north lay the HX and SC convoys which sailed between Britain and

Lütjens now had the operational initiative. He had a choice of two potential killing-grounds. To the north lay the HX and SC convoys which sailed between Britain and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. To the south the SL and OG convoys which operated between Britain, Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

and Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and p ...

. He decided to opt for operations in the north. He used ''Admiral Hipper'', at that moment also loose in the Atlantic, to create a diversion by ordering her to the south. In retrospect it was an error of judgment. Lütjens' orders were to avoid combat on equal terms. He had not realised—and was not to know—that southern convoys were virtually undefended at this point in the war, but on orders of the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of it ...

, all northern convoys had an escort of at least one Capital Ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic im ...

. German intelligence had warned him that and were based at Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

. He estimated that they could escort convoys only east of their base, and so he began to search for targets with this in mind.

On 8 February, B-Dienst alerted the German warships of convoy HX 106 which sailed from Halifax, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

on 31 January. Lütjens planned a pincer movement converging from the north and south. The convoy was escorted by ''Ramillies'' armed with eight 15-inch guns. When the battleship was sighted Lütjens strictly followed the ''Seekriegsleitung

The ''Seekriegsleitung'' or SKL (Maritime Warfare Command) was a higher command staff section of the Kaiserliche Marine and the Kriegsmarine of Germany during the World Wars.

World War I

The SKL was established on August 27, 1918, on the initiativ ...

''s directive not to engage enemy capital ships.

Kurt-Caesar Hoffmann

Kurt-Caesar Hoffmann (26 August 1895 – 19 May 1988) was a senior naval commander in the German Navy ('' Kriegsmarine'') during World War II, who commanded the battleship . He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.

Career

Hof ...

, captain of ''Scharnhorst'', attempted to draw off the British battleship, so that ''Gneisenau'' could sink the merchant vessels. Lütjens, however, did not understand Hoffmann's intentions which the ''Scharnhorst'' captain was not able to communicate in detail in such short-order. A heated radio conversation followed in which Lütjens accused him of disobeying orders because he did not turn away immediately. The enemy ship did not leave the convoy and now Lütjens complained the British would be alerted to their position and as a consequence, successful attacks would now be more difficult to execute. In fact, Lütjens' fears were unfounded and luck was once again on his side. The British had sighted only one German ship. Since ''Hipper'' was known to be at sea, it was assumed she was the German vessel lurking around the convoy. Tovey's dismissal of the ''Naiad'' report masked the German ships' presence. Tovey still believed they were still in German ports. The disagreement did not adversely damage the two men's good relations.

The ships rendezvoused between Iceland and Canada with the tankers ''Esso Hamburg'' and ''Schlettstadt'' on 15 February. On 22 February, after seven days of fruitless searching some 500 nautical miles east of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, German radar picked up five cargo-empty ships from a westbound convoy sailing without escort towards American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

ports. The convoy identified the German ships and soon the radio waves were busy with signals sent from the frantic British merchantmen, which tried to disperse. The battleships quickly closed and sank four. A further ship, the 5,500-ton ''Harlesden'', carried a powerful wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The most ...

set but temporarily evaded them. Intent on silencing it, Lütjens dispatched his Arado Ar 196

The Arado Ar 196 was a shipboard reconnaissance low-wing monoplane aircraft built by the German firm of Arado starting in 1936. The next year it was selected as the winner of a design contest and became the standard aircraft of the ''Kriegsmarin ...

to locate it. Upon his return, the Arado pilot reported to have found it and claimed to have destroyed the aerial, but took damage from return fire. Its position now known, the German ships closed in and sank ''Harlesden'' at 23:00. The day's haul amounted to around 25,000 tons. On a negative note, the chase and action occurred at long range and the expenditure of ammunition was expensive. Lütjens used his radio for the first time since 8 February and commanded the supply ships ''Esso Hamburg'' and ''Schlettstadt'' to meet him near the Azores so he could replenish stocks. On 26 February he unloaded 180 prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

onto the tankers ''Ermland'' and ''Friedrich Breme''. In the action of 22 February, only 11 Allied sailors had become casualties.

Disappointed with the lack of targets in the north, Lütjens' ships then sailed to the coast of West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

. On 3 March 1941 they reached the Cape Verde Islands

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...