Grosse Fuge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Grosse Fuge'' (German spelling: ''Große'' ''Fuge'', also known in English as the ''Great Fugue'' or ''Grand Fugue''), Op. 133, is a single-movement composition for string quartet by

At the first performance of the quartet, other movements were received enthusiastically, but the fugue was not a success. Many musicians and critics in Vienna's music periodicals denounced the fugue. Composer and violinist

At the first performance of the quartet, other movements were received enthusiastically, but the fugue was not a success. Many musicians and critics in Vienna's music periodicals denounced the fugue. Composer and violinist

A similar motif appears in Act II, measures 44–47, of the "Dance of the Blessed Spirits" from Gluck's opera '' Orfeo ed Euridice'' (1774), and also in

Whatever the origin of the motif, Beethoven was fascinated by it. He used it, or fragments of it, in a number of places in the late quartets, most notably in the first movement of his Op. 132 string quartet. The opening is shown below:

:

In the course of the ''Grosse Fuge'', Beethoven plays this motif in every possible variation: ''fortissimo'' and ''pianissimo'', in different rhythms, upside down and backwards. The usual practice in a traditional fugue is to make a simple, unadorned statement of the subject at the outset, but Beethoven from the very beginning presents the subject in a host of variations.

The third motif is a lilting melody that serves as the theme of the ''andante'' section of the fugue:

:

A fourth element – not so much a motif as an effect – is the

This statement of the subject disintegrates into a trill, and silence. Beethoven then repeats the subject, but in a completely different rhythm, in

In the third variation, Beethoven presents a variation of the second subject in the triplet rhythm of the countersubject of the first variation, with the main subject syncopated in eighth notes, in diminution (that is, the subject is played at twice the speed).

This last variation grows increasingly chaotic, with triplets breaking out in the inner voices, until it ultimately collapses – each instrument finishing on a different part of the measure and ending inconclusively on a final

Despite the growing complexity of the fugal writing, Beethoven instructs the players ''sempre piano'' – always quiet. Leonard Ratner writes of this section, "

Here Beethoven starts to use trills intensely. This adds to the extremely dense texture and rhythmic complexity. Kerman writes of this fugal section, "The piece seems to be in danger of cracking under the tension of its own rhythmic fury."

In the second episode of this fugue, Beethoven adds in the triplet figure from the first variation of the first fugue:

The trills become more intense. In the third episode, in the dominant key of E major, Beethoven uses a leaping motif that recalls the second subject of the first fugue:

The fourth episode returns to the key of A. The cello plays the main subject in a way that harks back to the ''overtura''. More elements of the first fugue return: the syncopation used for the main subject, the tenth leaps from the second subject, the diminuted main subject in the viola.

A series of trills leads back to the home key of B, and a restatement of the ''scherzo'' section.

There follows a section that analysts have described as "uneasy hesitation" or "puzzling" and "diffused". Fragments of the various subjects appear and disappear, and the music seems to lose energy. A silence, and then a fragmentary burst of the opening of the first fugue. Another silence. A snippet of the ''meno mosso''. Another silence. And then a ''fortissimo'' restatement of the very opening of the piece, leading to the coda.

From here the music moves forward, at first haltingly, but then with more and more energy, to the final passage, where the first subject is played in triplets below the soaring violin line playing a variant of the second subject.

" tis one of the great artistic testaments to the human capacity for meaning in the face of the threat of chaos. Abiding faith in the relevance of visionary struggle in our lives powerfully informs the structure and character of the music," writes Mark Steinberg, violinist of the

" tis one of the great artistic testaments to the human capacity for meaning in the face of the threat of chaos. Abiding faith in the relevance of visionary struggle in our lives powerfully informs the structure and character of the music," writes Mark Steinberg, violinist of the

Musicologists have tried to explain what Beethoven meant by this: David Levy has written an entire article on the notation, and Stephen Husarik looked to the history of Baroque

In early 1826, the publisher of the Op. 130 String Quartet, Mathias Artaria, told Beethoven there were "many requests" for a piano four-hand arrangement of the ''Grosse Fuge''. This was well before any known discussion of publishing the fugue independently of the quartet; considering the generally negative reaction to the fugue, Solomon speculates this may have been Artaria's initial ploy to persuade Beethoven to separate the fugue from the Op. 130 quartet. When Artaria asked Beethoven to prepare the piano arrangement he was not interested, so Artaria instead engaged Anton Halm to arrange the piece. When Beethoven was shown Halm's work, he was not satisfied and immediately began writing his own note-for-note arrangement of the fugue. Beethoven's arrangement was completed subsequent to the C minor String Quartet, Op. 131, and was published by Artaria as Op. 134. Among Beethoven’s objections to Halm’s arrangement was that it tried to make it easier for the players. “Halm enclosed a note saying that for the sake of convenience he had to break up some of the lines among the hands. Beethoven wasn’t interested in convenience.”

In early 1826, the publisher of the Op. 130 String Quartet, Mathias Artaria, told Beethoven there were "many requests" for a piano four-hand arrangement of the ''Grosse Fuge''. This was well before any known discussion of publishing the fugue independently of the quartet; considering the generally negative reaction to the fugue, Solomon speculates this may have been Artaria's initial ploy to persuade Beethoven to separate the fugue from the Op. 130 quartet. When Artaria asked Beethoven to prepare the piano arrangement he was not interested, so Artaria instead engaged Anton Halm to arrange the piece. When Beethoven was shown Halm's work, he was not satisfied and immediately began writing his own note-for-note arrangement of the fugue. Beethoven's arrangement was completed subsequent to the C minor String Quartet, Op. 131, and was published by Artaria as Op. 134. Among Beethoven’s objections to Halm’s arrangement was that it tried to make it easier for the players. “Halm enclosed a note saying that for the sake of convenience he had to break up some of the lines among the hands. Beethoven wasn’t interested in convenience.”

Lucinda Childs, Anne-Teresa De Keermaeker et Maguy Marin pour Trois Grandes Fugues

/ref>

IMSLP

The fugue was republished b

Breitkopf and Hartel

in 1866 in ''Ludwig van Beethoven's Werke'' Series 6. Urtext editions are published by Henle and b

Universal

Manuscript of the piano four-hand transcription

by Beethoven in the Juilliard School, Juilliard Manuscript Collection Books: * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Journals and other sources: * * * * * * * * * * * *

"Great Fugue: Secrets of a Beethoven manuscript"

originally published in ''The New Yorker'', 6 February 2006 * *

Beethoven's String Quartet Op. 130, with the ''Grosse Fuge'' as the final movement

performed by the Orion String Quartet * Hill, P. and Frith, B. (2020) CD album, ''Beethoven, Works for Piano Four Hands'', Delphian Records. {{DEFAULTSORT:Grosse Fuge String quartets by Ludwig van Beethoven 1826 compositions Fugues Compositions in B-flat major Music dedicated to nobility or royalty

Ludwig van Beethoven

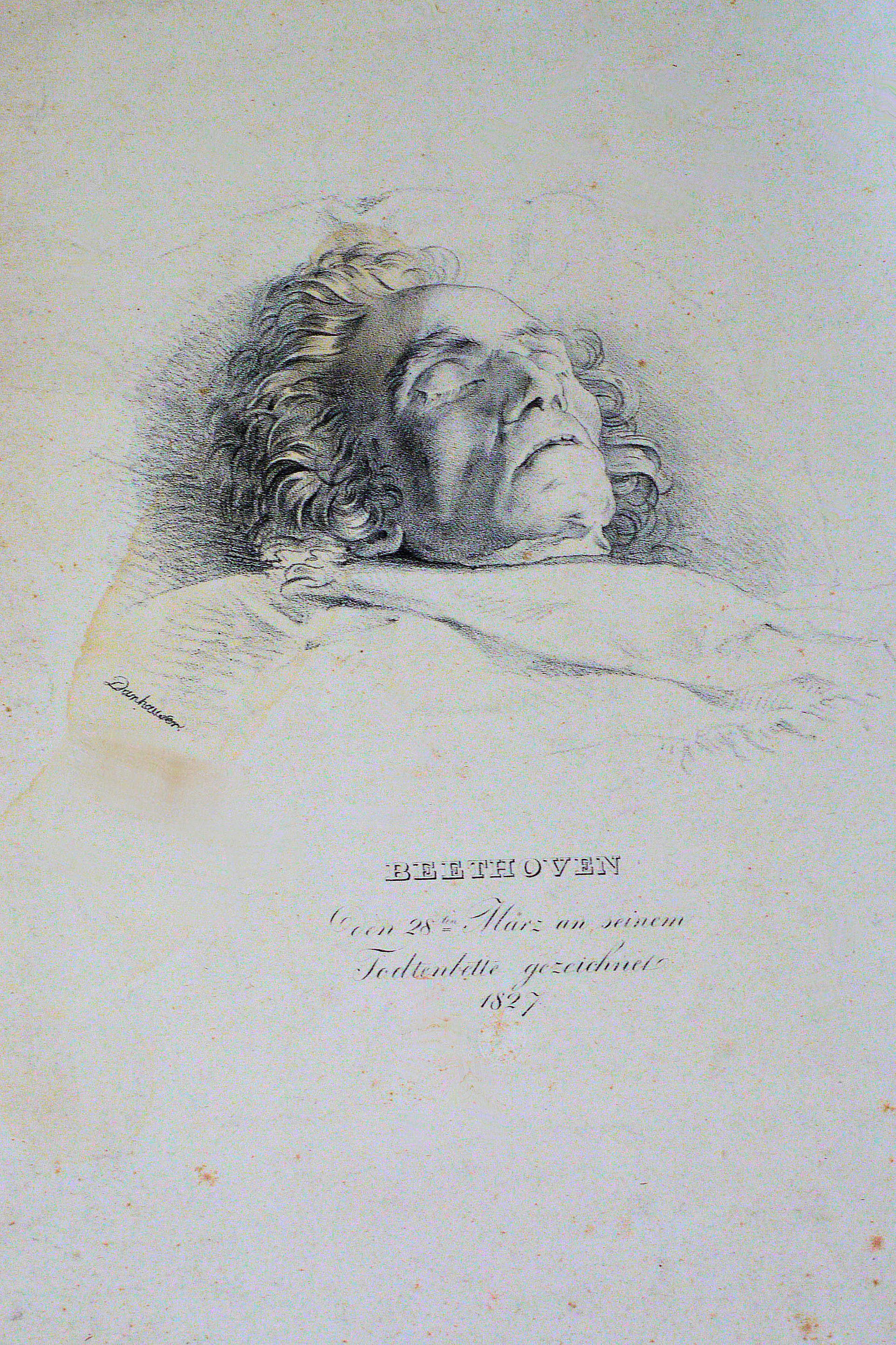

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classic ...

. An immense double fugue

In music, a fugue () is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the c ...

, it was universally condemned by contemporary music critics. A reviewer writing for the ''Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung

The ''Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung'' (''General music newspaper'') was a German-language periodical published in the 19th century. Comini (2008) has called it "the foremost German-language musical periodical of its time". It reviewed musical e ...

'' in 1826 described the fugue as "incomprehensible, like Chinese" and "a confusion of Babel". However, critical opinion of the work has risen steadily since the early 20th century and it is now considered among Beethoven's greatest achievements. Igor Stravinsky described it as "an absolutely contemporary piece of music that will be contemporary forever."

The composition originally served as the final movement of Beethoven's Quartet No. 13 in B major, Op. 130, written in 1825; but his publisher was concerned about the dismal commercial prospects of the piece and wanted Beethoven to replace the fugue with a new finale. Beethoven complied, and the ''Grosse Fuge'' was published as a separate work in 1827 as Op. 133. It was composed when Beethoven was nearly totally deaf, and is considered to be part of his set of late quartets. It was first performed in 1826, as the finale of the B quartet, by the Schuppanzigh Quartet The Schuppanzigh Quartet was a string quartet formed in Vienna in the 1790s by the violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh. It continued, with breaks and changes of members, for many years. Schuppanzigh was a close friend and admirer of Ludwig van Beethoven, ...

.

Music analysts and critics have described the ''Grosse Fuge'' as "inaccessible", "eccentric", "filled with paradoxes", and "Armageddon". Critic and musicologist Joseph Kerman

Joseph Wilfred Kerman (3 April 1924 – 17 March 2014) was an American musicologist and music critic. Among the leading musicologists of his generation, his 1985 book ''Contemplating Music: Challenges to Musicology'' (published in the UK as ''Mu ...

calls it "the most problematic single work in Beethoven's output and ... doubtless in the entire literature of music", and violinist David Matthews describes it as "fiendishly difficult to play".

History of the composition

Beethoven originally wrote the fugue as the final movement of his String Quartet No. 13, Op. 130. His choice of a fugal form for the last movement was well grounded in tradition:Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have led ...

, Mozart, and Beethoven himself had previously used fugues as final movements of quartets. But in recent years, Beethoven had become increasingly concerned with the challenge of integrating this Baroque form into the Classical structure. "In my student days I wrote dozens of ugues... but maginationalso wishes to exert its privileges ... and a new and really poetic element must be introduced into the traditional form," Beethoven wrote. The resulting movement was a mammoth work, longer than the five other movements of the quartet combined. The fugue is dedicated to the Archduke Rudolf of Austria, his student and patron.

At the first performance of the quartet, other movements were received enthusiastically, but the fugue was not a success. Many musicians and critics in Vienna's music periodicals denounced the fugue. Composer and violinist

At the first performance of the quartet, other movements were received enthusiastically, but the fugue was not a success. Many musicians and critics in Vienna's music periodicals denounced the fugue. Composer and violinist Louis Spohr

Louis Spohr (, 5 April 178422 October 1859), baptized Ludewig Spohr, later often in the modern German form of the name Ludwig, was a German composer, violinist and conductor. Highly regarded during his lifetime, Spohr composed ten symphonies, t ...

called it, and the other late quartets, "an indecipherable, uncorrected horror".

Despite the contemporary criticism, Beethoven himself never doubted the value of the fugue. Karl Holz, Beethoven's secretary, confidant and second violinist of the Schuppanzigh Quartet The Schuppanzigh Quartet was a string quartet formed in Vienna in the 1790s by the violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh. It continued, with breaks and changes of members, for many years. Schuppanzigh was a close friend and admirer of Ludwig van Beethoven, ...

that first performed the work, brought Beethoven the news that the audience had demanded encores of two middle movements. Beethoven, enraged, was reported to have growled, "And why didn't they encore the Fugue? That alone should have been repeated! Cattle! Asses!"

However, the fugue was so roundly condemned by critics and audience alike that Beethoven's publisher, Matthias Artaria (1793–1835), decided to try to convince Beethoven to publish it separately. Artaria tasked Holz with persuading Beethoven to separate the fugue from the rest of the quartet. Holz wrote:

Artaria ... charged me with the terrible and difficult task of convincing Beethoven to compose a new finale, which would be more accessible to the listeners as well as the instrumentalists, to substitute for the fugue which was so difficult to understand. I maintained to Beethoven that this fugue, which departed from the ordinary and surpassed even the last quartets in originality, should be published as a separate work and that it merited a designation as a separate opus. I communicated to him that Artaria was disposed to pay him a supplementary honorarium for the new finale. Beethoven told me he would reflect on it, but already on the next day I received a letter giving his agreement.Why the notoriously stubborn Beethoven apparently agreed so readily to replace the fugue is an enigma in the history of this quintessentially enigmatic piece. Some historians have speculated that he likely did it for the money (Beethoven was extremely bad at managing his personal finances and was often broke), while others believe it was to satisfy his critics, or simply because Beethoven came to feel the fugue stood best on its own. The fugue is connected to the other movements of Op. 130 by various hints of motifs, and by a tonal link to the preceding ''

Cavatina

Cavatina is a musical term, originally meaning a short song of simple character, without a second strain or any repetition of the air. It is now frequently applied to any simple, melodious air, as distinguished from brilliant arias or recitatives ...

'' movement (the Cavatina ends on a G, and the fugue begins with the same G). The lively replacement final movement is in the form of a contredanse and is completely uncontroversial. Beethoven composed this replacement in the autumn of 1826, and is the last complete piece of music he was to write. In May 1827, about two months after Beethoven's death, Matthias Artaria published the first edition of Op. 130 with the new finale, the ''Grosse Fuge'' separately (with the French title ''Grande Fugue'') as Op. 133, and a four-hand piano arrangement of the fugue as Op. 134.

General analysis

Dozens of analyses have attempted to delve into the structure of the ''Grosse Fuge'', with conflicting results. The work has been described as an expansion of the formal Baroque grand fugue, as a multi-movement work rolled into a single piece, and as a symphonic poem insonata form

Sonata form (also ''sonata-allegro form'' or ''first movement form'') is a musical structure generally consisting of three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation. It has been used widely since the middle of the 18th c ...

. Stephen Husarik has suggested that the relationships between the keys of the different sections of the fugue mirror what he describes as the wedge-like structure of the eight-note motif that is the main fugal subject, the "contour hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

is a driving force behind the Grosse Fuge". But Leah Gayle Weinberg writes: "The Grosse Fuge has been and continues to be a problematic subject of scholarly discussion for many reasons; the most basic is that its very form defies categorization."

Main motif

The central motif of the fugue is an eight-note subject that climbs chromatically upward: :Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have led ...

's String Quartet in G, Op. 33, No. 5. ii, mm. 27–29. Another similar subject, with syncopated or gapped rhythm (called '' Unterbrechung'' in German), appears in a treatise on counterpoint by Johann Georg Albrechtsberger

Johann Georg Albrechtsberger (3 February 1736 – 7 March 1809) was an Austrian composer, organist, and music theorist, and one of the teachers of Ludwig van Beethoven. He was a friend of Haydn and Mozart.

Biography

Albrechtsberger was born at K ...

, who taught Beethoven composition. Joseph Kerman

Joseph Wilfred Kerman (3 April 1924 – 17 March 2014) was an American musicologist and music critic. Among the leading musicologists of his generation, his 1985 book ''Contemplating Music: Challenges to Musicology'' (published in the UK as ''Mu ...

suggests that Beethoven modeled the motif after J. S. Bach's fugue in B minor from ''The Well-Tempered Clavier

''The Well-Tempered Clavier'', BWV 846–893, consists of two sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys for keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach. In the composer's time, ''clavier'', meaning keyboard, referred to a variety of i ...

''. Its subject is shown below:

:Other motifs

In stark contrast to this simple chromatic motif is the second subject of the fugue, which leaps dramatically in huge intervals – tenths and twelfths: :trill

TRILL (Transparent Interconnection of Lots of Links) is an Internet Standard implemented by devices called TRILL switches. TRILL combines techniques from bridging and routing, and is the application of link-state routing to the VLAN-aware cus ...

. Beethoven also uses trills extensively, simultaneously creating a sense of disintegration of the motifs, leading to a climax.

:Form

''Overtura''

The fugue opens with a 24-bar overture, which starts with a dramatic ''fortissimo'' unison G, and statement of the main fugal subject in the key of G major: :diminution

In Western music and music theory, diminution (from Medieval Latin ''diminutio'', alteration of Latin ''deminutio'', decrease) has four distinct meanings. Diminution may be a form of embellishment in which a long note is divided into a series ...

(meaning at double the tempo), twice, climbing up the scale; and then, again silence, and again the subject, this time unadorned, in a dramatic drop to ''pianissimo'' in the key of F major.

This leads to a statement of the third fugal subject, with the first subject in the bass:

Thus, Beethoven, in this brief introduction, presents not only the material that will make up the entire piece but also the spirit: violent shifts of mood, melodies disintegrating into chaos, dramatic silences, instability, and struggle.

First fugue

Following the overture is a strictly formaldouble fugue

In music, a fugue () is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the c ...

in the key of B major that follows all the rules of a Baroque fugue: an exposition

Exposition (also the French for exhibition) may refer to:

*Universal exposition or World's Fair

* Expository writing

** Exposition (narrative)

* Exposition (music)

*Trade fair

A trade fair, also known as trade show, trade exhibition, or trade e ...

and three variations, showcasing different contrapuntal

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

devices. But this is anything but a tame Baroque fugue: it is violent and dissonant, pitting awkward leaps of the second subject in iambic rhythm against the main subject in syncopation, at a constant dynamic that never falls below ''forte''. The resulting angular rhythmic confusion and displaced dissonances last almost five minutes.

First, Beethoven restates the main subject, broken up by rests between each note:

Then begins a double fugue, two subjects, played one against the other. The second subject in the first violin, and the first subject, syncopated, in the viola. Then the second violin and cello take up the same thing.

The first variation, following the rules of fugue, opens in the subdominant key of E. Beethoven adds to the chaos with a triplet figure in the first violin, played against the quaternary rhythm of the second subject in the second violin and the syncopated main subject in the viola.

The second variation, back in the key of B, is a '' stretto'' section, meaning that the fugal voices enter one right after the other. To this, Beethoven adds a countersubject

In music, a subject is the material, usually a recognizable melody, upon which part or all of a composition is based. In forms other than the fugue, this may be known as the theme.

Characteristics

A subject may be perceivable as a complete mus ...

in dactylic rhythm (shown in red below).

:fermata

A fermata (; "from ''fermare'', to stay, or stop"; also known as a hold, pause, colloquially a birdseye or cyclops eye, or as a grand pause when placed on a note or a rest) is a symbol of musical notation indicating that the note should be ...

, leading to the next section in the key of G.

''Meno mosso e moderato''

This section ("slower and at a moderate pace") is a complete change of character from the formal fugue that preceded it and the one that follows it. It is a ''fugato

In music, a fugue () is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the co ...

'', a section that combines contrapuntal writing with homophony

In music, homophony (;, Greek: ὁμόφωνος, ''homóphōnos'', from ὁμός, ''homós'', "same" and φωνή, ''phōnē'', "sound, tone") is a texture in which a primary part is supported by one or more additional strands that flesh ...

. "After the strenuousness of the B Fugue irst section the effect is of an almost blinding innocence," writes Joseph Kerman

Joseph Wilfred Kerman (3 April 1924 – 17 March 2014) was an American musicologist and music critic. Among the leading musicologists of his generation, his 1985 book ''Contemplating Music: Challenges to Musicology'' (published in the UK as ''Mu ...

. Analysts who see the fugue as a multi-movement work rolled into one view this as the traditional ''Andante'' movement. It opens with a statement of the third subject, against a pedal tone

Pedal tones (or pedals) are special low notes in the harmonic series of brass instruments. A pedal tone has the pitch of its harmonic series' fundamental tone. Its name comes from the foot pedal keyboard pedals of a pipe organ, which are used ...

in the viola, and continues with the third subject in the second violin, against the main subject ''cantus firmus

In music, a ''cantus firmus'' ("fixed melody") is a pre-existing melody forming the basis of a polyphonic composition.

The plural of this Latin term is , although the corrupt form ''canti firmi'' (resulting from the grammatically incorrect tre ...

'' in the viola.

The counterpoint becomes more complex, with the cello and first violin playing the main subject in canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western ca ...

while the second violin and viola pass the third subject between them.

:his

His or HIS may refer to:

Computing

* Hightech Information System, a Hong Kong graphics card company

* Honeywell Information Systems

* Hybrid intelligent system

* Microsoft Host Integration Server

Education

* Hangzhou International School, in ...

comes as a wonderful change of color, offered with the silkiest of textures, and with exquisite moments of glowing diatonism."

The polyphony gradually dissipates into homophony, and from there into unison, finally tapering into a dying, measured sixteenth-note tremolo, when the next section bursts out in the key of B.

Interlude and second fugue

Beethoven shifts gears: from G to B, from to , from ''pianissimo'' to ''fortissimo''. The ''fortissimo'' descends immediately to ''piano'', for a short interlude before the second fugue. This interlude is based on the main subject in diminution, meaning in double time. On top of this, Beethoven adds a lilting, slightly comic melody; analysts who see the fugue as a multi-movement work consider this section the equivalent of a ''scherzo

A scherzo (, , ; plural scherzos or scherzi), in western classical music, is a short composition – sometimes a movement from a larger work such as a symphony or a sonata. The precise definition has varied over the years, but scherzo often re ...

''.

In this interlude, Beethoven introduces the use of trill

TRILL (Transparent Interconnection of Lots of Links) is an Internet Standard implemented by devices called TRILL switches. TRILL combines techniques from bridging and routing, and is the application of link-state routing to the VLAN-aware cus ...

(hinted at, at the end of the ''Meno mosso'' section). The music grows in intensity and shifts into A major, for a new learned fugue.

In this fugue, Beethoven puts together three versions of the main subject: (1) the subject in its simple form, but in augmentation (meaning half the speed); (2) the same subject, abbreviated, in retrograde (that is, played backwards); and (3) a variation of the first half of the subject in diminution

In Western music and music theory, diminution (from Medieval Latin ''diminutio'', alteration of Latin ''deminutio'', decrease) has four distinct meanings. Diminution may be a form of embellishment in which a long note is divided into a series ...

(that is, double time). Together, they sound like this:

:Thematic convergence and coda

This leads back to a restatement of the ''meno mosso e moderato'' section. This time, though, instead of a silky ''pianissimo'', the ''fugato'' is played ''forte'', heavily accented (Beethoven writes on every sixteenth-note group), march-like. Analysts who see the fugue as a variation ofsonata-allegro

Sonata form (also ''sonata-allegro form'' or ''first movement form'') is a musical structure generally consisting of three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation. It has been used widely since the middle of the 18th c ...

form consider this to be part of the recapitulation section. In this section, Beethoven uses another complex contrapuntal device: the second violin plays the theme, the first violin plays the main subject in a high register, and the viola plays the main subject in inversion

Inversion or inversions may refer to:

Arts

* , a French gay magazine (1924/1925)

* ''Inversion'' (artwork), a 2005 temporary sculpture in Houston, Texas

* Inversion (music), a term with various meanings in music theory and musical set theory

* ...

– that is, upside down.

:Understanding the ''Grosse Fuge''

Analyses of the ''Grosse Fuge'' help to understand the structure and contrapuntal devices of this mammoth piece. But, writes musicologist David B. Levy, "Regardless of how one hears the piece structurally, the composition remains filled with paradoxes that leave the listener ultimately dissatisfied with an exegesis derived solely from a structural perspective." Since its composition, musicians, critics and listeners have tried to explain the tremendous impact this piece has.Brentano String Quartet

The Brentano Quartet is an American string quartet.

History

Founded in 1992 at the Juilliard School, the quartet's founding members were violinists Mark Steinberg and Serena Canin, violist Misha Amory, and cellist Michael Kannen. At the suggesti ...

. "More than anything else in music ... it justifies the ways of God to men," writes musicologist Leonard Ratner

Leonard Gilbert Ratner (July 30, 1916 – September 2, 2011), was an American musicologist, Professor of Musicology at Stanford University, He was a specialist in the style of the Classical period, and best known as a developer of the concept of ...

.

But beyond a recognition of the hugeness and almost mystical impact of the music, critics fail to agree on its character. Robert S. Kahn says "it presents a titanic struggle overcome." Daniel Chua, on the contrary, writes, "The work speaks of failure, the very opposite of the triumphant synthesis associated with Beethovenian recapitulations." Stephen Husarik, in his essay "Musical direction and the wedge in Beethoven's high comedy, Grosse Fuge op. 133", contends that in the fugue, Beethoven is actually writing a parody of Baroque formalism. "The B Fuga of op.133 stumbles forward in what is probably the most relentless and humorous assertion of modal rhythms since 12th century Notre Dame organum." Kahn disagrees: "... the comparison to comic music is surprising. There is nothing comic about the Grosse Fuge ...."

In many discussions of the piece, the issue of struggle is central. Sara Bitloch, violinist of the Elias String Quartet, says this sense of struggle informs her group's interpretation of the fugue. "Every part has to feel like it's a huge struggle ... You need to finish the Grosse Fuge absolutely exhausted." She calls the piece "apocalyptic". Arnold Steinhardt of the Guarneri String Quartet

The Guarneri Quartet was an American string quartet founded in 1964 at the Marlboro Music School and Festival. It was admired for its rich, warm, complex tone and its bold, dramatic interpretations of the quartet literature, with a particular aff ...

calls it "Armageddon ... the chaos out of which life itself evolved".

One way to express the impact of the fugue is through poetry. In her poem "Little Fugue", Sylvia Plath

Sylvia Plath (; October 27, 1932 – February 11, 1963) was an American poet, novelist, and short story writer. She is credited with advancing the genre of confessional poetry and is best known for two of her published collections, '' Th ...

associates the fugue with death, in a melange of hazy associations with the yew tree (a symbol of death in Celtic Britain), the Holocaust, and the death of her own father:

The poet Mark Doty

Mark Doty (born August 10, 1953) is an American poet and memoirist best known for his work ''My Alexandria.'' He was the winner of the National Book Award for Poetry in 2008.

Early life

Mark Doty was born in Maryville, Tennessee to Lawrence an ...

wrote of his feelings on listening to the ''Grosse Fuge'':

Reception and musical influence

After the first performance as the original finale to the op. 130 quartet in 1826, the fugue is not known to have been publicly performed again until 1853 in Paris by the Maurin Quartet. One hundred years after its publication, it still had not entered the standard quartet repertoire. "The attitude of mind in which most people listen to chamber music must undergo a radical change" to understand this piece, wroteJoseph de Marliave

Joseph de Marliave (16 November 1873 – 24 August 1914) was a French musicologist. He is best known for his book on Beethoven's string quartets, which was the most widely read and quoted book on the subject prior to Joseph Kerman's 1966 book ''T ...

in 1928. "This fugue is one of the two works by Beethoven—the other being the fugue from the piano sonata, Op. 106—which should be excluded from performance." As late as 1947, Daniel Gregory Mason

Daniel Gregory Mason (November 20, 1873 – December 4, 1953) was an American composer and music critic.

Biography

Mason was born in Brookline, Massachusetts. He came from a long line of notable American musicians, including his father Henry Ma ...

called the fugue "repellent".

By the 1920s, some string quartets were including the fugue in their programs. Since then, the fugue has steadily gained greatness in the eyes of musicians and performers. "The Great Fugue ... now seems to me the most perfect miracle in music," said Igor Stravinsky. "It is also the most absolutely contemporary piece of music I know, and contemporary forever ... Hardly birthmarked by its age, the Great Fugue is, in rhythm alone, more subtle than any music of my own century ... I love it beyond everything." Pianist Glenn Gould

Glenn Herbert Gould (; né Gold; September 25, 1932October 4, 1982) was a Canadian classical pianist. He was one of the most famous and celebrated pianists of the 20th century, and was renowned as an interpreter of the keyboard works of Johann ...

said, "For me, the 'Grosse Fuge' is not only the greatest work Beethoven ever wrote but just about the most astonishing piece in musical literature."

Some analysts and musicians see the fugue as an early assault on the diatonic tonal system that prevailed in Classical music. Robert Kahn sees the main subject of the fugue as a precursor of the tone row

In music, a tone row or note row (german: Reihe or '), also series or set, is a non-repetitive ordering of a set of pitch-classes, typically of the twelve notes in musical set theory of the chromatic scale, though both larger and smaller sets ...

, the basis of the twelve-tone system developed by Arnold Schoenberg. "Your cradle was Beethoven's Grosse Fuge," artist Oskar Kokoschka

Oskar Kokoschka (1 March 1886 – 22 February 1980) was an Austrian artist, poet, playwright, and teacher best known for his intense expressionistic portraits and landscapes, as well as his theories on vision that influenced the Viennese Expres ...

wrote to Schoenberg in a letter. Composer Alfred Schnittke

Alfred Garrievich Schnittke (russian: Альфре́д Га́рриевич Шни́тке, link=no, Alfred Garriyevich Shnitke; 24 November 1934 – 3 August 1998) was a Russian composer of Jewish-German descent. Among the most performed and re ...

quotes the subject in his third string quartet (1983). There have also been numerous orchestral arrangements of the fugue, including by conductors Wilhelm Furtwängler

Gustav Heinrich Ernst Martin Wilhelm Furtwängler ( , , ; 25 January 188630 November 1954) was a German conductor and composer. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest symphonic and operatic conductors of the 20th century. He was a major ...

and Felix Weingartner

Paul Felix Weingartner, Edler von Münzberg (2 June 1863 – 7 May 1942) was an Austrian conductor, composer and pianist.

Life and career

Weingartner was born in Zara, Dalmatia, Austria-Hungary (now Zadar, Croatia), to Austrian parents. ...

.

Performance challenges

Performers approaching the ''Grosse Fuge'' face a host of technical and musical challenges. Among the technical difficulties of the piece are difficult passagework, complex cross-rhythms that require exact synchronization, and problems of intonation, where the harmonies pass from dissonance to resolution. Once mastering the technical difficulties, there are many interpretive issues to resolve. One of these is whether the fugue should be played as the finale of Op. 130, as originally written, or as a separate piece. Playing the fugue as the final movement of Op. 130, rather than the light, Haydnesque replacement movement, completely changes the character of the quartet, analysts Robert Winter and Robert Martin note. Played with the new finale, the preceding movement, the "Cavatina", a heartfelt and intense aria, is the emotional center of the piece. Played with the fugue as the finale, the Cavatina is a prelude to the massive and compelling fugue. On the other hand, the fugue stands alone well. "Current taste is decisively in favor of the fugal finale," conclude Winter and Martin. A number of quartets have recorded Op. 130 with the fugue and the replacement finale on separate disks. A second issue facing performers is whether to choose a "learned" interpretation – one that clarifies the complex contrapuntal structure of the piece – or one that focuses primarily on the dramatic impulses of the music. "Beethoven had taken a form that is basically an intellectual form, where the emotions take second place, compared to the structure, and he has completely turned that around, writing one of the most emotionally charged pieces ever," says Sara Bitloch of the Elias Quartet. "As a performer that's a particularly difficult balance to find ... Our first approach was to find a kind of hierarchy in the themes ... but we found that when we do that we're really missing the point of the piece."Tied eighth notes

After deciding on the overall approach to the music, there are numerous local decisions to be made about how to play particular passages. One issue concerns the peculiar notation that Beethoven uses in the syncopated presentation of the main subject – first in the ''overtura'' but later throughout the piece. Rather than writing this as a series of quarter notes, he writes two tied eighth notes. :ornamentation

An ornament is something used for decoration.

Ornament may also refer to:

Decoration

*Ornament (art), any purely decorative element in architecture and the decorative arts

*Biological ornament, a characteristic of animals that appear to serve on ...

for an explanation. Performers have interpreted it in various ways. The Alban Berg Quartett

The Alban Berg Quartett was a string quartet founded in Vienna, Austria in 1970, named after Alban Berg.

Members

Beginnings

The Berg Quartet was founded in 1970 by four young professors of the Vienna Academy of Music, and made its debut in ...

plays the notes almost as a single note, but with an emphasis on the first eighth note to create a subtle differentiation. Eugene Drucker of the Emerson String Quartet

The Emerson String Quartet, also known as the Emerson Quartet, is an American string quartet that was initially formed as a student group at the Juilliard School in 1976. It was named for American poet and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson and beg ...

plays this as two distinct eighth notes. Mark Steinberg of the Brentano String Quartet

The Brentano Quartet is an American string quartet.

History

Founded in 1992 at the Juilliard School, the quartet's founding members were violinists Mark Steinberg and Serena Canin, violist Misha Amory, and cellist Michael Kannen. At the suggesti ...

sometimes joins the eighth notes, and sometimes separates them, marking the difference by playing the first eighth without vibrato, then adding vibrato for the second.

Arrangement for piano four hands

In early 1826, the publisher of the Op. 130 String Quartet, Mathias Artaria, told Beethoven there were "many requests" for a piano four-hand arrangement of the ''Grosse Fuge''. This was well before any known discussion of publishing the fugue independently of the quartet; considering the generally negative reaction to the fugue, Solomon speculates this may have been Artaria's initial ploy to persuade Beethoven to separate the fugue from the Op. 130 quartet. When Artaria asked Beethoven to prepare the piano arrangement he was not interested, so Artaria instead engaged Anton Halm to arrange the piece. When Beethoven was shown Halm's work, he was not satisfied and immediately began writing his own note-for-note arrangement of the fugue. Beethoven's arrangement was completed subsequent to the C minor String Quartet, Op. 131, and was published by Artaria as Op. 134. Among Beethoven’s objections to Halm’s arrangement was that it tried to make it easier for the players. “Halm enclosed a note saying that for the sake of convenience he had to break up some of the lines among the hands. Beethoven wasn’t interested in convenience.”

In early 1826, the publisher of the Op. 130 String Quartet, Mathias Artaria, told Beethoven there were "many requests" for a piano four-hand arrangement of the ''Grosse Fuge''. This was well before any known discussion of publishing the fugue independently of the quartet; considering the generally negative reaction to the fugue, Solomon speculates this may have been Artaria's initial ploy to persuade Beethoven to separate the fugue from the Op. 130 quartet. When Artaria asked Beethoven to prepare the piano arrangement he was not interested, so Artaria instead engaged Anton Halm to arrange the piece. When Beethoven was shown Halm's work, he was not satisfied and immediately began writing his own note-for-note arrangement of the fugue. Beethoven's arrangement was completed subsequent to the C minor String Quartet, Op. 131, and was published by Artaria as Op. 134. Among Beethoven’s objections to Halm’s arrangement was that it tried to make it easier for the players. “Halm enclosed a note saying that for the sake of convenience he had to break up some of the lines among the hands. Beethoven wasn’t interested in convenience.”

Rediscovery of manuscript

In 2005, Beethoven's 1826autograph

An autograph is a person's own handwriting or signature. The word ''autograph'' comes from Ancient Greek (, ''autós'', "self" and , ''gráphō'', "write"), and can mean more specifically: Gove, Philip B. (ed.), 1981. ''Webster's Third New Inter ...

of his piano four-hands transcription of the ''Grosse Fuge'' resurfaced at Palmer Theological Seminary

Palmer Theological Seminary is a Baptist seminary in St. Davids. It is affiliated with the American Baptist Churches USA. It was founded in 1925 as Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary. Its parent institution is Eastern University.

History

The ...

(then Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary) in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. The manuscript was authenticated by Dr. Jeffrey Kallberg

Jeffrey Kallberg (born 17 October 1954) is an American musicologist, who specializes 19th and 20th-century classical music, as well as topics in critical theory and gender studies related to music. He has written numerous articles and studies ...

at the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

and Dr. Stephen Roe, head of Sotheby's

Sotheby's () is a British-founded American multinational corporation with headquarters in New York City. It is one of the world's largest brokers of fine and decorative art, jewellery, and collectibles. It has 80 locations in 40 countries, an ...

Manuscript Department. The manuscript had been missing for 115 years. It was auctioned by Sotheby's on 1 December 2005, and bought for GBP

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and t ...

1.12 million (US$1.95 million) by a then-unknown purchaser, who has since revealed himself to be Bruce Kovner

Bruce Stanley Kovner (born 1945) is an American billionaire hedge fund manager and philanthropist. He is chairman of CAM Capital, which he established in January 2012 to manage his investment, trading and business activities. From 1983 through 2 ...

, a publicity-shy multi-billionaire who donated the manuscript – along with 139 other original and rare pieces of music – to the Juilliard School of Music in February 2006. It has since become available in Juilliard's online manuscript collection. The manuscript's known provenance is that it was listed in an 1890 catalogue and sold at an auction in Berlin to a Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, Ohio, industrialist, whose daughter gave it and other manuscripts including a Mozart ''Fantasia'' to a church in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

, Pennsylvania, in 1952. It is not known how the Beethoven manuscript came to be in the possession of the library.

The most striking change in the piano duet version occurs at the start. "Beethoven had tampered in an interesting way with the first bars of the Fugue's introductory section. The quartet version begins with loud unison G's, spread over three octaves and one and a half bars. In his initial draft of the piano arrangement, Beethoven replicated the original. Then, apparently, he decided that the Gs needed more strength and weight. The manuscript shows that he squeezed in two extra tremolando bars, expanding the moment in time. He also added octaves above and below, expanding it in space."According to pianist Peter Hill, Beethoven transferred the Fugue from string quartet to piano "with obvious care. Revisiting the Fugue in this way may well have caused Beethoven to rethink the possibilities of what he had composed, to conclude that the Fugue could (and perhaps should) stand alone." Hill concludes, "What Beethoven created for the ''Grosse Fuge'' transcended the immediate purpose. Instead, he re-imagined a masterpiece in another medium, different from the original, but equally valid because equally characteristic of its creator."

In theatre

* 1992: ''Die grosse Fuge'', dance piece for 8 dancers byAnne Teresa De Keersmaeker

Anne Teresa, Baroness De Keersmaeker (, born 1960 in Mechelen, Belgium, grew up in Wemmel) is a contemporary dance choreographer. The dance company constructed around her, , was in residence at La Monnaie in Brussels from 1992 to 2007.

Biograph ...

,

* 2001: ''Grosse Fugue'', dance piece for 4 dancers by , Compagnie Maguy Marin

* 2016: ''Grosse Fugue'', dance piece for 12 dancers by Lucinda Childs, Opéra National de Lyon/ref>

Notes

References

Scores: * * First published edition of the fugue by Matthias Artaria, 1825, available aIMSLP

The fugue was republished b

Breitkopf and Hartel

in 1866 in ''Ludwig van Beethoven's Werke'' Series 6. Urtext editions are published by Henle and b

Universal

Manuscript of the piano four-hand transcription

by Beethoven in the Juilliard School, Juilliard Manuscript Collection Books: * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Journals and other sources: * * * * * * * * * * * *

External links

*Alex Ross (music critic), Alex Ross a"Great Fugue: Secrets of a Beethoven manuscript"

originally published in ''The New Yorker'', 6 February 2006 * *

Beethoven's String Quartet Op. 130, with the ''Grosse Fuge'' as the final movement

performed by the Orion String Quartet * Hill, P. and Frith, B. (2020) CD album, ''Beethoven, Works for Piano Four Hands'', Delphian Records. {{DEFAULTSORT:Grosse Fuge String quartets by Ludwig van Beethoven 1826 compositions Fugues Compositions in B-flat major Music dedicated to nobility or royalty