Great San Francisco Earthquake on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

At 05:12 Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of

The 1906 earthquake preceded the development of the

The 1906 earthquake preceded the development of the

"Our 10 Greatest Natural Disasters," ''American Heritage'', Aug./Sept. 2006. A strong

As damaging as the earthquake and its aftershocks were, the fires that burned out of control afterward were even more destructive. It has been estimated that up to 90% of the total destruction was the result of the subsequent fires. Within three days, over 30 fires, caused by ruptured gas mains, destroyed approximately 25,000 buildings on 490 city blocks. The fires cost an estimated $350 million at the time (equivalent to $ billion in ).

Some of the fires were started when

As damaging as the earthquake and its aftershocks were, the fires that burned out of control afterward were even more destructive. It has been estimated that up to 90% of the total destruction was the result of the subsequent fires. Within three days, over 30 fires, caused by ruptured gas mains, destroyed approximately 25,000 buildings on 490 city blocks. The fires cost an estimated $350 million at the time (equivalent to $ billion in ).

Some of the fires were started when

During the first few days, soldiers provided valuable services like patrolling streets to discourage looting and guarding buildings such as the

During the first few days, soldiers provided valuable services like patrolling streets to discourage looting and guarding buildings such as the

Northern California

Northern California (colloquially known as NorCal) is a geographic and cultural region that generally comprises the northern portion of the U.S. state of California. Spanning the state's northernmost 48 counties, its main population centers incl ...

was struck by a major earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

with an estimated moment magnitude

The moment magnitude scale (MMS; denoted explicitly with or Mw, and generally implied with use of a single M for magnitude) is a measure of an earthquake's magnitude ("size" or strength) based on its seismic moment. It was defined in a 1979 pape ...

of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity

The Modified Mercalli intensity scale (MM, MMI, or MCS), developed from Giuseppe Mercalli's Mercalli intensity scale of 1902, is a seismic intensity scale used for measuring the intensity of shaking produced by an earthquake. It measures the eff ...

of XI (''Extreme''). High-intensity shaking was felt from Eureka

Eureka (often abbreviated as E!, or Σ!) is an intergovernmental organisation for research and development funding and coordination. Eureka is an open platform for international cooperation in innovation. Organisations and companies applying th ...

on the North Coast North Coast or Northcoast may refer to :

Antigua and Barbuda

* Major Division of North Coast, a census division in Saint John Parish

Australia

*New South Wales North Coast, a region

Canada

*The British Columbia Coast, primarily the communiti ...

to the Salinas Valley

The Salinas Valley is one of the major valleys and most productive Agriculture, agricultural regions in California. It is located west of the San Joaquin Valley and south of San Francisco Bay and the Santa Clara Valley.

The Salinas River (Califo ...

, an agricultural region to the south of the San Francisco Bay Area

The San Francisco Bay Area, often referred to as simply the Bay Area, is a populous region surrounding the San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun Bay estuaries in Northern California. The Bay Area is defined by the Association of Bay Area Go ...

. Devastating fires soon broke out in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

and lasted for several days. More than 3,000 people died, and over 80% of the city was destroyed. The events are remembered as one of the worst and deadliest earthquakes in the history of the United States. The death toll remains the greatest loss of life from a natural disaster in California's history and high on the lists of American disasters.

Tectonic setting

TheSan Andreas Fault

The San Andreas Fault is a continental transform fault that extends roughly through California. It forms the tectonics, tectonic boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate, and its motion is Fault (geology)#Strike-slip fau ...

is a continental transform fault

A transform fault or transform boundary, is a fault along a plate boundary where the motion is predominantly horizontal. It ends abruptly where it connects to another plate boundary, either another transform, a spreading ridge, or a subductio ...

that forms part of the tectonic

Tectonics (; ) are the processes that control the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. These include the processes of mountain building, the growth and behavior of the strong, old cores of continents k ...

boundary between the Pacific Plate

The Pacific Plate is an oceanic tectonic plate that lies beneath the Pacific Ocean. At , it is the largest tectonic plate.

The plate first came into existence 190 million years ago, at the triple junction between the Farallon, Phoenix, and Iza ...

and the North American Plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Cuba, the Bahamas, extreme northeastern Asia, and parts of Iceland and the Azores. With an area of , it is the Earth's second largest tectonic plate, behind the Pacific ...

. The strike-slip

In geology, a fault is a planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust result from the action of plate tectonic ...

fault is characterized by mainly lateral motion in a dextral

Sinistral and dextral, in some scientific fields, are the two types of chirality ("handedness") or relative direction. The terms are derived from the Latin words for "left" (''sinister'') and "right" (''dexter''). Other disciplines use different ...

sense, where the western (Pacific) plate moves northward relative to the eastern (North American) plate. This fault runs the length of California from the Salton Sea

The Salton Sea is a shallow, landlocked, highly saline body of water in Riverside and Imperial counties at the southern end of the U.S. state of California. It lies on the San Andreas Fault within the Salton Trough that stretches to the Gulf o ...

in the south to Cape Mendocino

Cape Mendocino (Spanish: ''Cabo Mendocino'', meaning "Cape of Mendoza"), which is located approximately north of San Francisco, is located on the Lost Coast entirely within Humboldt County, California, United States. At 124° 24' 34" W longitude ...

in the north, a distance of about . The maximum observed surface displacement was about 20 feet (6 m); geodetic

Geodesy ( ) is the Earth science of accurately measuring and understanding Earth's figure (geometric shape and size), orientation in space, and gravity. The field also incorporates studies of how these properties change over time and equivale ...

measurements show displacements of up to 28 feet (8.5 m).

Earthquake

The 1906 earthquake preceded the development of the

The 1906 earthquake preceded the development of the Richter magnitude scale

The Richter scale —also called the Richter magnitude scale, Richter's magnitude scale, and the Gutenberg–Richter scale—is a measure of the strength of earthquakes, developed by Charles Francis Richter and presented in his landmark 1935 ...

by three decades. The most widely accepted estimate for the magnitude of the quake on the modern moment magnitude scale

The moment magnitude scale (MMS; denoted explicitly with or Mw, and generally implied with use of a single M for magnitude) is a measure of an earthquake's magnitude ("size" or strength) based on its seismic moment. It was defined in a 1979 pape ...

is 7.9; values from 7.7 to as high as 8.3 have been proposed. According to findings published in the ''Journal of Geophysical Research

The ''Journal of Geophysical Research'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal. It is the flagship journal of the American Geophysical Union. It contains original research on the physical, chemical, and biological processes that contribute to the un ...

'', severe deformations in the Earth's crust

Earth's crust is Earth's thin outer shell of rock, referring to less than 1% of Earth's radius and volume. It is the top component of the lithosphere, a division of Earth's layers that includes the crust and the upper part of the mantle. The ...

took place both before and after the earthquake's impact. Accumulated strain on the faults in the system was relieved during the earthquake, which is the supposed cause of the damage along the segment of the San Andreas plate boundary. The 1906 rupture propagated both northward and southward for a total of . Shaking was felt from Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

to Los Angeles, and as far inland as central Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

.Christine Gibson"Our 10 Greatest Natural Disasters," ''American Heritage'', Aug./Sept. 2006. A strong

foreshock

A foreshock is an earthquake that occurs before a larger seismic event (the mainshock) and is related to it in both time and space. The designation of an earthquake as ''foreshock'', ''mainshock'' or aftershock is only possible after the full sequ ...

preceded the main shock by about 20 to 25 seconds. The strong shaking of the main shock lasted about 42 seconds. There were decades of minor earthquakes – more than at any other time in the historical record for northern California – before the 1906 quake. Previously interpreted as precursory activity to the 1906 earthquake, they have been found to have a strong seasonal pattern and are now believed to be caused by large seasonal sediment loads in coastal bays that overlie faults as a result of the erosion caused by hydraulic mining

Hydraulic mining is a form of mining that uses high-pressure jets of water to dislodge rock material or move sediment.Paul W. Thrush, ''A Dictionary of Mining, Mineral, and Related Terms'', US Bureau of Mines, 1968, p.560. In the placer mining of ...

in the later years of the California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

.

For years, the epicenter

The epicenter, epicentre () or epicentrum in seismology is the point on the Earth's surface directly above a hypocenter or focus, the point where an earthquake or an underground explosion originates.

Surface damage

Before the instrumental pe ...

of the quake was assumed to be near the town of Olema, in the Point Reyes

Point Reyes (, meaning "Point of the Kings") is a prominent cape and popular Northern California tourist destination on the Pacific coast. Located in Marin County, it is approximately west-northwest of San Francisco. The term is often applied ...

area of Marin County

Marin County is a county located in the northwestern part of the San Francisco Bay Area of the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 262,231. Its county seat and largest city is San Rafael. Marin County is acros ...

, due to local earth displacement measurements. In the 1960s, a seismologist at UC Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of Californi ...

proposed that the epicenter was more likely offshore of San Francisco, to the northwest of the Golden Gate

The Golden Gate is a strait on the west coast of North America that connects San Francisco Bay to the Pacific Ocean. It is defined by the headlands of the San Francisco Peninsula and the Marin Peninsula, and, since 1937, has been spanned by th ...

. The most recent analyses support an offshore location for the epicenter, although significant uncertainty remains. An offshore epicenter is supported by the occurrence of a local tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater explo ...

recorded by a tide gauge at the San Francisco Presidio

The Presidio of San Francisco (originally, El Presidio Real de San Francisco or The Royal Fortress of Saint Francis) is a park and former U.S. Army post on the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula in San Francisco, California, and is part o ...

; the wave had an amplitude of approximately and an approximate period of 4045 minutes.

Analysis of triangulation data before and after the earthquake strongly suggests that the rupture along the San Andreas Fault was about in length, in agreement with observed intensity data. The available seismological data support a significantly shorter rupture length, but these observations can be reconciled by allowing propagation at speeds above the S-wave

__NOTOC__

In seismology and other areas involving elastic waves, S waves, secondary waves, or shear waves (sometimes called elastic S waves) are a type of elastic wave and are one of the two main types of elastic body waves, so named because th ...

velocity ( supershear). Supershear propagation has now been recognized for many earthquakes associated with strike-slip faulting.

Recently, using old photographs and eyewitness accounts, researchers were able to estimate the location of the hypocenter

In seismology, a hypocenter or hypocentre () is the point of origin of an earthquake or a subsurface nuclear explosion. A synonym is the focus of an earthquake.

Earthquakes

An earthquake's hypocenter is the position where the strain energy s ...

of the earthquake as offshore from San Francisco or near San Juan Bautista, confirming previous estimates.

Intensity

The most important characteristic of the shaking intensity noted inAndrew Lawson

Andrew Cowper Lawson (July 25, 1861 – June 16, 1952) was a Scots-Canadian geologist who became professor of geology at the University of California, Berkeley. He was the editor and co-author of the 1908 report on the 1906 San Francisco earthq ...

's 1908 report was the clear correlation

In statistics, correlation or dependence is any statistical relationship, whether causal or not, between two random variables or bivariate data. Although in the broadest sense, "correlation" may indicate any type of association, in statistics ...

of intensity with underlying geologic conditions. Areas situated in sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand an ...

-filled valleys sustained stronger shaking than nearby bedrock sites, and the strongest shaking occurred in areas of former bay where soil liquefaction

Soil liquefaction occurs when a cohesionless saturated or partially saturated soil substantially loses strength and stiffness in response to an applied stress such as shaking during an earthquake or other sudden change in stress condition, in ...

had occurred. Modern seismic-zonation practice accounts for the differences in seismic hazard posed by varying geologic conditions. The shaking intensity as described on the Modified Mercalli intensity scale

The Modified Mercalli intensity scale (MM, MMI, or MCS), developed from Giuseppe Mercalli's Mercalli intensity scale of 1902, is a seismic intensity scale used for measuring the intensity of shaking produced by an earthquake. It measures the eff ...

reached XI (''Extreme'') in San Francisco and areas to the north like Santa Rosa where destruction was devastating.

Aftershocks

The main shock was followed by many aftershocks and some remotely triggered events. As with the1857 Fort Tejon earthquake

The 1857 Fort Tejon earthquake occurred at about 8:20 a.m. (Pacific time) on January 9 in central and Southern California. One of the largest recorded earthquakes in the United States, with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.9, it ruptured ...

, there were fewer aftershocks than would have been expected for a shock of that size. Very few of them were located along the trace of the 1906 rupture, tending to concentrate near the ends of the rupture or on other structures away from the San Andreas Fault, such as the Hayward Fault

The Hayward Fault Zone is a right-lateral strike-slip geologic fault zone capable of generating destructive earthquakes. This fault is about long, situated mainly along the western base of the hills on the east side of San Francisco Bay. It runs ...

. The only aftershock in the first few days of near M 5 or greater occurred near Santa Cruz at 14:28 PST on April 18, with a magnitude of about 4.9 . The largest aftershock happened at 01:10 PST on April 23, west of Eureka with an estimated magnitude of about 6.7 , with another of the same size more than three years later at 22:45 PST on October 28 near Cape Mendocino.

Remotely triggered events included an earthquake swarm

In seismology, an earthquake swarm is a sequence of seismic events occurring in a local area within a relatively short period. The time span used to define a swarm varies, but may be days, months, or years. Such an energy release is different f ...

in the Imperial Valley

, photo = Salton Sea from Space.jpg

, photo_caption = The Imperial Valley below the Salton Sea. The US-Mexican border runs diagonally across the lower left of the image.

, map_image = Newriverwatershed-1-.jpg

, map_caption = Map of Imperial ...

area, which culminated in an earthquake of about 6.1 at 16:30 PST on April 18, 1906. Another event of this type occurred at 12:31 PST on April 19, 1906, with an estimated magnitude of about 5.0 , and an epicenter beneath Santa Monica Bay

Santa Monica Bay is a bight (geography), bight of the Pacific Ocean in Southern California, United States. Its boundaries are slightly ambiguous, but it is generally considered to be the part of the Pacific within an imaginary line drawn betwe ...

.

Damage

Early death counts ranged from 375 to over 500. However, hundreds of fatalities inChinatown

A Chinatown () is an ethnic enclave of Chinese people located outside Greater China, most often in an urban setting. Areas known as "Chinatown" exist throughout the world, including Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Austra ...

went ignored and unrecorded. The total number of deaths is still uncertain, but various reports presented a range of 700–3,000+. In 2005, the city's Board of Supervisors voted unanimously in support of a resolution written by novelist James Dalessandro ("1906") and city historian Gladys Hansen ("Denial of Disaster") to recognize the figure of 3,000 plus as the official total. Most of the deaths occurred within San Francisco, but 189 were reported elsewhere in the Bay Area; nearby cities such as Santa Rosa

Santa Rosa is the Italian, Portuguese and Spanish name for Saint Rose.

Santa Rosa may also refer to:

Places Argentina

*Santa Rosa, Mendoza, a city

* Santa Rosa, Tinogasta, Catamarca

* Santa Rosa, Valle Viejo, Catamarca

*Santa Rosa, La Pampa

* Sa ...

and San Jose also suffered severe damage. In Monterey County

Monterey County ( ), officially the County of Monterey, is a county located on the Pacific coast in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, its population was 439,035. The county's largest city and county seat is Salinas.

Montere ...

, the earthquake permanently shifted the course of the Salinas River near its mouth. Where previously the river emptied into Monterey Bay

Monterey Bay is a bay of the Pacific Ocean located on the coast of the U.S. state of California, south of the San Francisco Bay Area and its major city at the south of the bay, San Jose. San Francisco itself is further north along the coast, by a ...

between Moss Landing

Moss Landing, formerly Moss, is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Monterey County, California, United States. It is located north-northeast of Monterey, at an elevation of . It is on the shore of Monterey Bay, at the ...

and Watsonville

Watsonville is a city in Santa Cruz County, California, located in the Monterey Bay Area of the Central Coast of California. The population was 52,590 according to the 2020 census. Predominantly Latino and Democratic, Watsonville is a self- ...

, it was diverted south to a new channel just north of Marina

A marina (from Spanish , Portuguese and Italian : ''marina'', "coast" or "shore") is a dock or basin with moorings and supplies for yachts and small boats.

A marina differs from a port in that a marina does not handle large passenger ships o ...

.

Between 227,000 and 300,000 people were left homeless out of a population of about 410,000; half of those who evacuated fled across the bay to Oakland

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third largest city overall in the Bay A ...

and Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

. Newspapers described Golden Gate Park

Golden Gate Park, located in San Francisco, California, United States, is a large urban park consisting of of public grounds. It is administered by the San Francisco Recreation & Parks Department, which began in 1871 to oversee the development ...

, the Presidio, the Panhandle and the beaches between Ingleside and North Beach as covered with makeshift tents. More than two years later, many of these refugee camps were still in operation.

The earthquake and fire left long-standing and significant pressures on the development of California. At the time of the disaster, San Francisco had been the ninth-largest city in the United States and the largest on the West Coast West Coast or west coast may refer to:

Geography Australia

* Western Australia

*Regions of South Australia#Weather forecasting, West Coast of South Australia

* West Coast, Tasmania

**West Coast Range, mountain range in the region

Canada

* Britis ...

. Over a period of 60 years, the city had become the financial, trade, and cultural center of the West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sunset, Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic languages, German ...

, operating the busiest port on the West Coast. It was the "gateway to the Pacific", through which growing U.S. economic and military power was projected into the Pacific and Asia. Over 80% of the city was destroyed by the earthquake and fire. Though San Francisco rebuilt quickly, the disaster diverted trade, industry, and population growth south to Los Angeles, which during the 20th century became the largest and most important urban area in the West. Many of the city's leading poets and writers retreated to Carmel-by-the-Sea

Carmel-by-the-Sea (), often simply called Carmel, is a city in Monterey County, California, United States, founded in 1902 and incorporated on October 31, 1916. Situated on the Monterey Peninsula, Carmel is known for its natural scenery and ric ...

where, as "The Barness", they established the arts colony reputation that continues today.

The 1908 Lawson Report, a study of the 1906 quake led and edited by Professor Andrew Lawson of the University of California, showed that the same San Andreas Fault which had caused the disaster in San Francisco ran close to Los Angeles as well. The earthquake was the first natural disaster of its magnitude to be documented by photography and motion picture footage and occurred at a time when the science of seismology was blossoming.

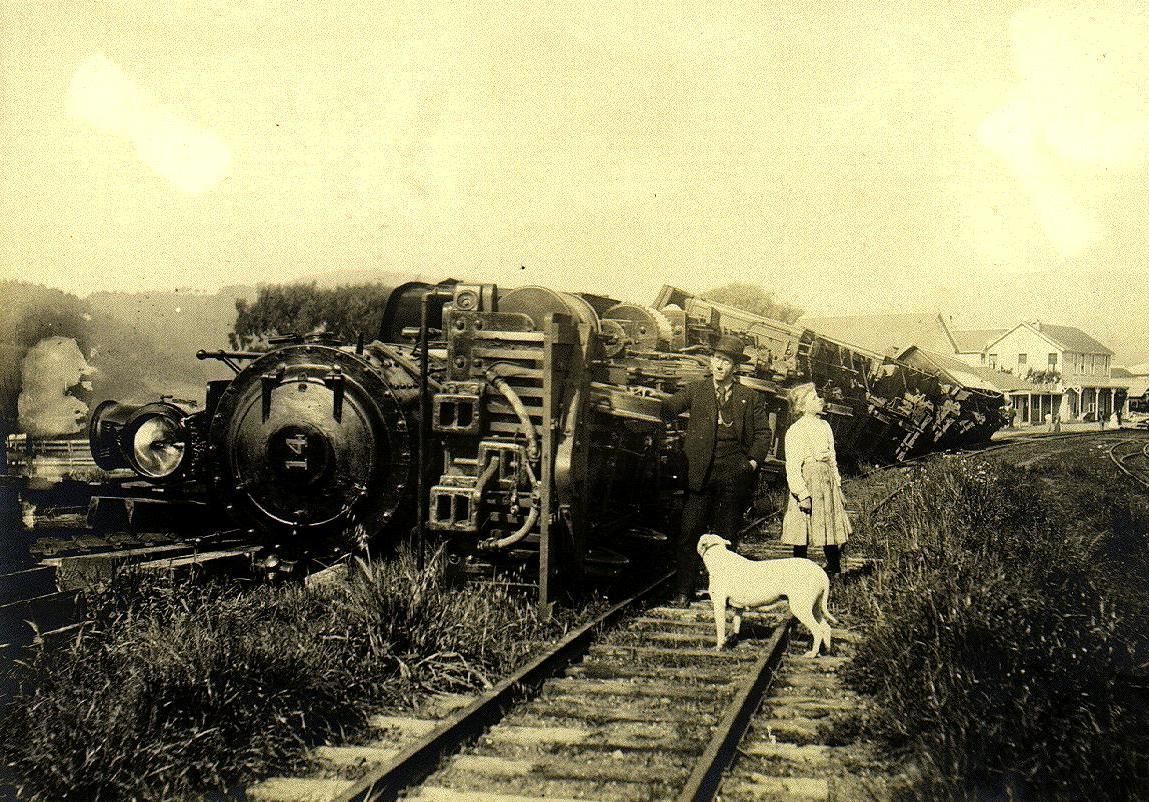

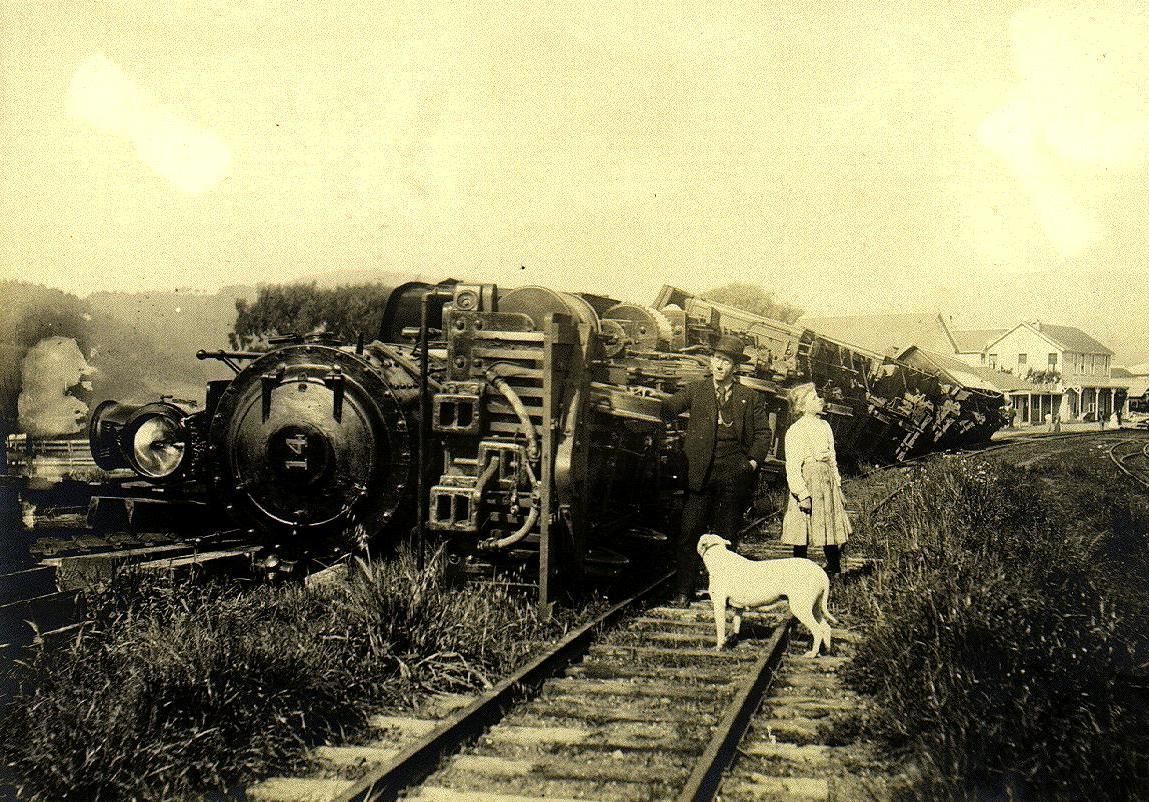

Other cities

Although the impact of the earthquake on San Francisco was the most famous, the earthquake also inflicted considerable damage on several other cities. These include San Jose andSanta Rosa

Santa Rosa is the Italian, Portuguese and Spanish name for Saint Rose.

Santa Rosa may also refer to:

Places Argentina

*Santa Rosa, Mendoza, a city

* Santa Rosa, Tinogasta, Catamarca

* Santa Rosa, Valle Viejo, Catamarca

*Santa Rosa, La Pampa

* Sa ...

, the entire downtown of which was essentially destroyed.

Fires

As damaging as the earthquake and its aftershocks were, the fires that burned out of control afterward were even more destructive. It has been estimated that up to 90% of the total destruction was the result of the subsequent fires. Within three days, over 30 fires, caused by ruptured gas mains, destroyed approximately 25,000 buildings on 490 city blocks. The fires cost an estimated $350 million at the time (equivalent to $ billion in ).

Some of the fires were started when

As damaging as the earthquake and its aftershocks were, the fires that burned out of control afterward were even more destructive. It has been estimated that up to 90% of the total destruction was the result of the subsequent fires. Within three days, over 30 fires, caused by ruptured gas mains, destroyed approximately 25,000 buildings on 490 city blocks. The fires cost an estimated $350 million at the time (equivalent to $ billion in ).

Some of the fires were started when San Francisco Fire Department

The San Francisco Fire Department (SFFD) provides firefighting, hazardous materials response services, technical rescue services and emergency medical response services to the City and County of San Francisco, California.

History

Volunteer Depa ...

firefighters, untrained in the use of dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and Stabilizer (chemistry), stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish people, Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern Germa ...

, attempted to demolish buildings to create firebreak

A firebreak or double track (also called a fire line, fuel break, fireroad and firetrail in Australia) is a gap in vegetation or other combustible material that acts as a barrier to slow or stop the progress of a bushfire or wildfire. A firebre ...

s. The dynamited buildings often caught fire. The city's fire chief, Dennis T. Sullivan

Dennis T. Sullivan (1852 - 1906) was the Chief of the San Francisco Fire Department in 1906. He was mortally wounded during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, when a neighboring building collapsed onto the fire station that housed the Chief's of ...

, who would have been responsible for coordinating firefighting efforts, had died from injuries sustained in the initial quake. In total, the fires burned for four days and nights.

Most of the destruction in the city was attributed to the fires, since widespread practice by insurers

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

was to indemnify

In contract law, an indemnity is a contractual obligation of one party (the ''indemnitor'') to compensate the loss incurred by another party (the ''indemnitee'') due to the relevant acts of the indemnitor or any other party. The duty to indemni ...

San Francisco properties from fire but not from earthquake damage. Some property owners deliberately set fire to damaged properties to claim them on their insurance. Captain Leonard D. Wildman of the U.S. Army Signal Corps

)

, colors = Orange and white

, colors_label = Corps colors

, march =

, mascot =

, equipment =

, equipment_label =

...

reported that he "was stopped by a fireman who told me that people in that neighborhood were firing their houses...they were told that they would not get their insurance on buildings damaged by the earthquake unless they were damaged by fire".

One landmark building lost in the fire was the Palace Hotel, subsequently rebuilt, which had many famous visitors including royalty and celebrated performers. It was constructed in 1875 primarily financed by Bank of California co-founder William Ralston

William "Billy" Chapman Ralston (January 12, 1826 – August 27, 1875) was a San Francisco businessman and financier, and the founder of the Bank of California.

Biography

William Chapman Ralston was born at Wellsville, Ohio, son of Robert Ralsto ...

, the "man who built San Francisco". In April 1906, the tenor Enrico Caruso

Enrico Caruso (, , ; 25 February 1873 – 2 August 1921) was an Italian operatic first lyrical tenor then dramatic tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the major opera houses of Europe and the Americas, appearing in a wide variety of roles (74) ...

and members of the Metropolitan Opera Company

The Metropolitan Opera (commonly known as the Met) is an American opera company based in New York City, resident at the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, currently situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The company is opera ...

came to San Francisco to give a series of performances at the Grand Opera House. The night after Caruso's performance in ''Carmen

''Carmen'' () is an opera in four acts by the French composer Georges Bizet. The libretto was written by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy, based on the Carmen (novella), novella of the same title by Prosper Mérimée. The opera was first perfo ...

'', the tenor was awakened in the early morning in his Palace Hotel suite by a strong jolt. Clutching an autographed photo of President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, Caruso made an effort to get out of the city, first by boat and then by train, and vowed never to return to San Francisco. Caruso died in 1921, having remained true to his word. The Metropolitan Opera Company lost all of its traveling sets and costumes in the earthquake and ensuing fires.

Some of the greatest losses from fire were in scientific laboratories. Alice Eastwood

__NOTOC__

Alice Eastwood (January 19, 1859 – October 30, 1953) was a Canadian American botanist. She is credited with building the botanical collection at the California Academy of Sciences, in San Francisco. She published over 310 scienti ...

, the curator of botany at the California Academy of Sciences

The California Academy of Sciences is a research institute and natural history museum in San Francisco, California, that is among the largest museums of natural history in the world, housing over 46 million specimens. The Academy began in 1853 ...

in San Francisco, is credited with saving nearly 1,500 specimens, including the entire type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wiktionary:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to a ...

collection for a newly discovered and extremely rare species, before the remainder of the largest botanical collection in the western United States was destroyed in the fire. The entire laboratory and all the records of Benjamin R. Jacobs

Benjamin Ricardo Jacobs, Ph.D. (March 15, 1879 – February 3, 1963) was born at the American Consulate in Lima, Peru to Rosa Mulet Jacobs of Valparaíso, Chile, a French-Chilean, and Washington Michael Jacobs of South Carolina in the Unite ...

, a biochemist who was researching the nutrition of everyday foods, were destroyed. The original California flag

California Flag is a thoroughbred racehorse, foaled at Hi Card Ranch on February 19, 2004. He is sired by Avenue of Flags, a son of Seattle Slew, out of the Afleet (a son of Mr. Prospector) mare Ultrafleet.

He is best known for setting a new t ...

used in the 1846 Bear Flag Revolt

The California Republic ( es, La República de California), or Bear Flag Republic, was an unrecognized breakaway state from Mexico, that for 25 days in 1846 militarily controlled an area north of San Francisco, in and around what is now Son ...

at Sonoma, which at the time was being stored in a state building in San Francisco, was also destroyed in the fire.Response

The city's fire chief, Dennis T. Sullivan, was gravely injured when the earthquake first struck and later died from his injuries. The interim fire chief sent an urgent request to the Presidio, aUnited States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

post on the edge of the stricken city, for dynamite. General Frederick Funston

Frederick Funston (November 9, 1865 – February 19, 1917), also known as Fighting Fred Funston, was a general in the United States Army, best known for his roles in the Spanish–American War and the Philippine–American War. He received ...

had already decided that the situation required the use of federal troops. Telephoning a San Francisco Police Department officer, he sent word to Mayor Eugene Schmitz

Eugene Edward Schmitz (August 22, 1864 – November 20, 1928), often referenced as "Handsome Gene" Schmitz, was an American musician and politician, the 26th mayor of San Francisco (1902-7), who was in office during the 1906 San Francisco earthqu ...

of his decision to assist and then ordered federal troops from nearby Angel Island Angel Island may refer to:

*Angel Island (California), historic site of the United States Immigration Station, Angel Island, and part of Angel Island State Park, in San Francisco Bay, California

* Angel Island, Papua New Guinea

* ''Angel Island'' (n ...

to mobilize and enter the city. Explosives were ferried across the bay from the California Powder Works

California Powder Works was the first American explosive powder manufacturing company west of the Rocky Mountains. When the outbreak of the Civil War cut off supplies of gunpowder to California's mining and road-building industries, a local manufac ...

in what is now Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the Gr ...

.

During the first few days, soldiers provided valuable services like patrolling streets to discourage looting and guarding buildings such as the

During the first few days, soldiers provided valuable services like patrolling streets to discourage looting and guarding buildings such as the U.S. Mint

The United States Mint is a bureau of the Department of the Treasury responsible for producing coinage for the United States to conduct its trade and commerce, as well as controlling the movement of bullion. It does not produce paper money; that ...

, post office, and county jail. They aided the fire department in dynamiting to demolish buildings in the path of the fires. The Army also became responsible for feeding, sheltering, and clothing the tens of thousands of displaced residents of the city. Under the command of Funston's superior, Major General Adolphus Greely

Adolphus Washington Greely (March 27, 1844 – October 20, 1935) was a United States Army officer and polar explorer. He attained the rank of Major general (United States), major general and was a recipient of the Medal of Honor.

A native o ...

, Commanding Officer of the Pacific Division, over 4,000 federal troops saw service during the emergency. Police officers, firefighters, and soldiers would regularly commandeer passing civilians for work details to remove rubble and assist in rescues. On July 1, 1906, non-military authorities assumed responsibility for relief efforts, and the Army withdrew from the city.

On April 18, in response to riots among evacuees and looting, Mayor Schmitz issued and ordered posted a proclamation that "The Federal Troops, the members of the Regular Police Force and all Special Police Officers have been authorized by me to kill any and all persons found engaged in Looting or in the Commission of Any Other Crime". Accusations of soldiers engaging in looting also surfaced. Retired Captain Edward Ord

Edward Otho Cresap Ord (October 18, 1818 – July 22, 1883) was an American engineer and United States Army officer who saw action in the Seminole War, the Indian Wars, and the American Civil War. He commanded an army during the final days of th ...

of the 22nd Infantry Regiment was appointed a special police officer by Schmitz and liaised with Greely for relief work with the 22nd Infantry and other military units involved in the emergency. Ord later wrote a long letter to his mother on April 20 regarding Schmitz's "Shoot-to-Kill" order and some "despicable" behavior of certain soldiers of the 22nd Infantry who were looting. He also made it clear that the majority of soldiers served the community well.

Aftermath

Property losses from the disaster have been estimated to be more than $400 million in 1906 dollars. This is equivalent to $ in dollars. An insurance industry source tallies insured losses at $235 million, the equivalent to $ in dollars. Political and business leaders strongly downplayed the effects of the earthquake, fearing loss of outside investment in the city which was badly needed to rebuild. In his first public statement, California GovernorGeorge Pardee

George Cooper Pardee (July 25, 1857 – September 1, 1941) was an American doctor of medicine and politician. As the 21st Governor of California, holding office from January 7, 1903, to January 9, 1907, Pardee was the second native-born Californ ...

emphasized the need to rebuild quickly: "This is not the first time that San Francisco has been destroyed by fire, I have not the slightest doubt that the City by the Golden Gate will be speedily rebuilt, and will, almost before we know it, resume her former great activity". The earthquake is not even mentioned in the statement. Fatality and monetary damage estimates were manipulated.

Almost immediately after the quake (and even during the disaster), planning and reconstruction plans were hatched to quickly rebuild the city. Rebuilding funds were immediately tied up by the fact that virtually all the major banks had been sites of the conflagration, requiring a lengthy wait of seven to ten days before their fire-proof vaults could cool sufficiently to be safely opened. The Bank of Italy (now Bank of America

The Bank of America Corporation (often abbreviated BofA or BoA) is an American multinational investment bank and financial services holding company headquartered at the Bank of America Corporate Center in Charlotte, North Carolina. The bank w ...

) had evacuated its funds and was able to provide liquidity in the immediate aftermath. Its president also immediately chartered and financed the sending of two ships to return with shiploads of lumber from Washington and Oregon mills which provided the initial reconstruction materials and surge. Eleven days after the earthquake a rare Sunday baseball game was played in New York City (which would not allow regular Sunday baseball until 1919) between the Highlanders (soon to be the Yankees) and the Philadelphia Athletics to raise money for quake survivors.

William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

, the pioneering American psychologist, was teaching at Stanford

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is considere ...

at the time of the earthquake and traveled into San Francisco to observe first-hand its aftermath. He was most impressed by the positive attitude of the survivors and the speed with which they improvised services and created order out of chaos. This formed the basis of the chapter "On some Mental Effects of the Earthquake" in his book ''Memories and Studies''.

H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

The Army built 5,610

The Army built 5,610

During the first few days after news of the disaster reached the rest of the world, relief efforts reached over $5,000,000.Morris, Charles ed. ''The San Francisco Calamity by Earthquake and Fire''. Intro by Roger W. Lotchin. Philadelphia : J.C. Winston Co., 1906; Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2002. London raised hundreds of thousands of dollars. Individual citizens and businesses donated large sums of money for the relief effort:

During the first few days after news of the disaster reached the rest of the world, relief efforts reached over $5,000,000.Morris, Charles ed. ''The San Francisco Calamity by Earthquake and Fire''. Intro by Roger W. Lotchin. Philadelphia : J.C. Winston Co., 1906; Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2002. London raised hundreds of thousands of dollars. Individual citizens and businesses donated large sums of money for the relief effort:

", Aetna company information At least 137 insurance companies were directly involved and another 17 as reinsurers. Twenty companies went bankrupt.

"The Story of An Eyewitness"

London's report from the scene. Originally published in ''

The Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake

– United States Geological Survey *

The 1906 Earthquake and Fire

– National Archives

Before and After the Great Earthquake and Fire: Early Films of San Francisco, 1897–1916

–

A geologic tour of the San Francisco earthquake, 100 years later

–

The Great 1906 Earthquake and Fire

–

The Great 1906 Earthquake and Fire

–

Mark Twain and the San Francisco Earthquake

– Shapell Manuscript Foundation

Several videos of the aftermath

–

''San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906''

Seismographs of the earthquake taken from the Lick Observatory from the Lick Observatory Records Digital Archive, UC Santa Cruz Library's Digital Collections

– The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

– Photographic account of earthquake and fire aftermath from well-known North Beach photographer

– USGS * {{DEFAULTSORT:1906 San Francisco Earthquake San Francisco earthquake, 1906

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most species generally referred to as millets belong to the tribe Paniceae, but some millets al ...

's 'Man with the Hoe.' 'They'll cut it out of the frame,' he says, a little anxiously. 'Sure.' But there is no doubt anywhere that San Francisco can be rebuilt, larger, better, and soon. Just as there would be none at all if all this New York that has so obsessed me with its limitless bigness was itself a blazing ruin. I believe these people would more than half like the situation."

Reconstruction

The earthquake was crucial in the development of theUniversity of California, San Francisco

The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is a public land-grant research university in San Francisco, California. It is part of the University of California system and is dedicated entirely to health science and life science. It cond ...

and its medical facilities. Until 1906, the school faculty had provided care at the City-County Hospital (now the San Francisco General Hospital

The Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center (ZSFG) is a Public hospital in San Francisco, California, under the purview of the city's Department of Public Health. It serves as the only Level I Trauma Ce ...

), but did not have a hospital of its own. Following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, more than 40,000 people were relocated to a makeshift tent city in Golden Gate Park and were treated by the faculty of the Affiliated Colleges. This brought the school, which until then was located on the western outskirts of the city, in contact with significant population and fueled the commitment of the school towards civic responsibility and health care, increasing the momentum towards the construction of its own health facilities. In April 1907, one of the buildings was renovated for outpatient care with 75 beds. This created the need to train nursing students, and the UC Training School for Nurses was established, adding a fourth professional school to the Affiliated Colleges.

The grandeur of citywide reconstruction schemes required investment from Eastern monetary sources, hence the spin and de-emphasis of the earthquake, the promulgation of the tough new building codes, and subsequent reputation sensitive actions such as the official low death toll. One of the more famous and ambitious plans came from famed urban planner Daniel Burnham

Daniel Hudson Burnham (September 4, 1846 – June 1, 1912) was an American architect and urban designer. A proponent of the '' Beaux-Arts'' movement, he may have been, "the most successful power broker the American architectural profession has ...

. His bold plan called for, among other proposals, Haussmann Hausmann is a German word with former meanings "householder" and "freeholder" and current meaning "house-husband."

Hausmann (Hausman), Haussmann (Haussman), Haußmann, Hauszmann, etc. are German-origin surnames that may refer to:

Hausmann

* C ...

-style avenues, boulevards, arterial thoroughfares

An arterial road or arterial thoroughfare is a high-capacity urban road that sits below freeways/motorways on the road hierarchy in terms of traffic flow and speed. The primary function of an arterial road is to deliver traffic from collector roa ...

that radiated across the city, a massive civic center complex with classical structures, and what would have been the largest urban park in the world, stretching from Twin Peaks

''Twin Peaks'' is an American Mystery fiction, mystery serial drama television series created by Mark Frost and David Lynch. It premiered on American Broadcasting Company, ABC on April 8, 1990, and originally ran for two seasons until its cance ...

to Lake Merced

Lake Merced ( es, Laguna de Merced) is a freshwater lake in the southwest corner of San Francisco, in the U.S. state of California. It is surrounded by three golf courses (the private Olympic Club and San Francisco Golf Club, and the public TPC Har ...

with a large atheneum at its peak. But this plan was dismissed during the aftermath of the earthquake. For example, real estate investors and other land owners were against the idea because of the large amount of land the city would have to purchase to realize such proposals. While the original street grid was restored, many of Burnham's proposals inadvertently saw the light of day, such as a neoclassical civic center complex, wider streets, a preference of arterial thoroughfares, a subway under Market Street, a more people-friendly Fisherman's Wharf, and a monument to the city on Telegraph Hill A telegraph hill is a hill or other natural elevation that is chosen as part of an optical telegraph system.

Telegraph Hill may also refer to:

England

* A high point in the Haldon Hills, Devon

* Telegraph Hill, Dorset, a hill in the Dorset Down ...

, Coit Tower

Coit Tower is a tower in the Telegraph Hill neighborhood of San Francisco, California, offering panoramic views over the city and the bay. The tower, in the city's Pioneer Park, was built between 1932 and 1933 using Lillie Hitchcock Coit's beq ...

.

City fathers likewise attempted at the time to eliminate the Chinese population and export Chinatown (and other poor populations) to the edge of the county where the Chinese could still contribute to the local taxbase. The Chinese occupants had other ideas and prevailed instead. Chinatown was rebuilt in the newer, modern, Western form that exists today. The destruction of City Hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or a municipal building (in the Philippines), is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses ...

and the Hall of Records enabled thousands of Chinese immigrants to claim residency and citizenship, creating a backdoor to the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplom ...

, and bring in their relatives from China.

The earthquake was also responsible for the development of the Pacific Heights

Pacific Heights is a neighborhood in San Francisco, California. It has panoramic views of the Golden Gate Bridge, San Francisco Bay, the Palace of Fine Arts, Alcatraz, and the Presidio.

The Pacific Heights Residents Association defines the neig ...

neighborhood. The immense power of the earthquake had destroyed almost all of the mansions on Nob Hill

Nob Hill is a neighborhood of San Francisco, California, United States that is known for its numerous luxury hotels and historic mansions. Nob Hill has historically served as a center of San Francisco's upper class. Nob Hill is among the highes ...

except for the James C. Flood Mansion

The James C. Flood Mansion is a historic mansion at 1000 California Street, atop Nob Hill in San Francisco, California, USA. Now home of the Pacific-Union Club, it was built in 1886 as the townhouse for James C. Flood, a 19th-century silver ba ...

. Others that had not been destroyed were dynamited by the Army forces aiding the firefighting efforts in attempts to create firebreaks. As one indirect result, the wealthy looked westward where the land was cheap and relatively undeveloped, and where there were better views. Constructing new mansions without reclaiming and clearing rubble simply sped attaining new homes in the tent city during the reconstruction.

Reconstruction was swift, and largely completed by 1915, in time for the 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition which celebrated the reconstruction of the city and its "rise from the ashes". Since 1915, the city has officially commemorated the disaster each year by gathering the remaining survivors at Lotta's Fountain

Lotta's fountain is a fountain at the intersection of Market Street, where Geary and Kearny Streets connect in downtown San Francisco, California.

It was commissioned by actress Lotta Crabtree in 1875 as a gift to the city of San Francisco, an ...

, a fountain in the city's financial district

A financial district is usually a central area in a city where financial services firms such as banks, insurance companies and other related finance corporations have their head offices. In major cities, financial districts are often home to s ...

that served as a meeting point during the disaster for people to look for loved ones and exchange information.

Housing

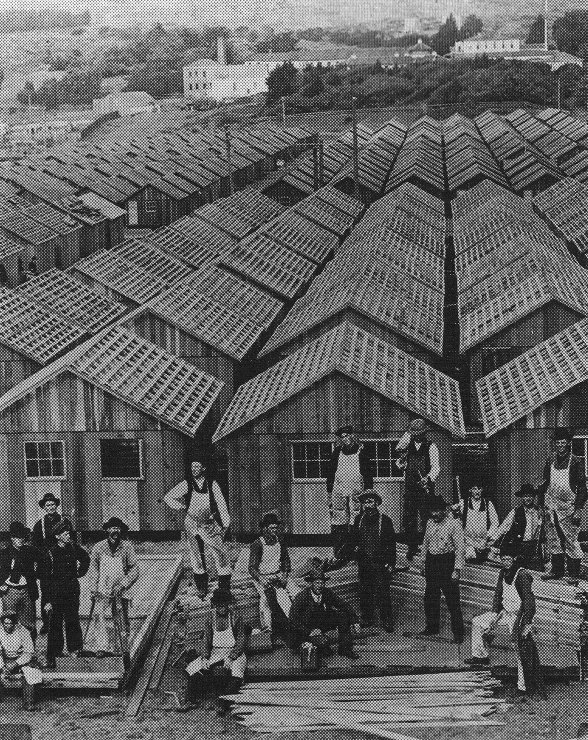

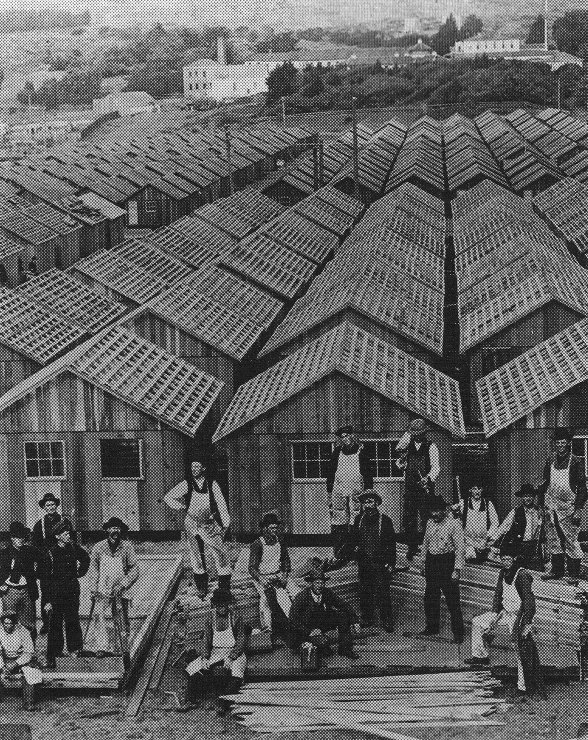

The Army built 5,610

The Army built 5,610 redwood

Sequoioideae, popularly known as redwoods, is a subfamily of coniferous trees within the family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affini ...

and fir

Firs (''Abies'') are a genus of 48–56 species of evergreen coniferous trees in the family (biology), family Pinaceae. They are found on mountains throughout much of North America, North and Central America, Europe, Asia, and North Africa. The ...

"relief houses" to accommodate 20,000 displaced people. The houses were designed by John McLaren, and were grouped in eleven camps, packed close to each other and rented to people for two dollars per month until rebuilding was completed. They were painted navy blue, partly to blend in with the site and partly because the military had large quantities of navy blue paint on hand. The camps had a peak population of 16,448 people, but by 1907 most people had moved out. The camps were then re-used as garages, storage spaces or shops. The cottages cost on average $100 to build. The $2 monthly rents went towards the full purchase price of $50. Most of the shacks have been destroyed, but a small number survived. One of the modest homes was purchased in 2006 for more than $600,000. The last official refugee camp was closed on June 30, 1908.

A 2017 study found that the fire had the effect of increasing the share of land used for nonresidential purposes: "Overall, relative to unburned blocks, residential land shares on burned blocks fell while nonresidential land shares rose by 1931. The study also provides insight into what held the city back from making these changes before 1906: the presence of old residential buildings. In reconstruction, developers built relatively fewer of these buildings, and the majority of the reduction came through single-family houses. Also, aside from merely expanding nonresidential uses in many neighborhoods, the fire created economic opportunities in new areas, resulting in clusters of business activity that emerged only in the wake of the disaster. These effects of the fire still remain today, and thus large shocks can be sufficient catalysts for permanently reshaping urban settings."

Relief

During the first few days after news of the disaster reached the rest of the world, relief efforts reached over $5,000,000.Morris, Charles ed. ''The San Francisco Calamity by Earthquake and Fire''. Intro by Roger W. Lotchin. Philadelphia : J.C. Winston Co., 1906; Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2002. London raised hundreds of thousands of dollars. Individual citizens and businesses donated large sums of money for the relief effort:

During the first few days after news of the disaster reached the rest of the world, relief efforts reached over $5,000,000.Morris, Charles ed. ''The San Francisco Calamity by Earthquake and Fire''. Intro by Roger W. Lotchin. Philadelphia : J.C. Winston Co., 1906; Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2002. London raised hundreds of thousands of dollars. Individual citizens and businesses donated large sums of money for the relief effort: Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

and Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

each gave $100,000; the Dominion of Canada made a special appropriation of $100,000; and even the Bank of Canada

The Bank of Canada (BoC; french: Banque du Canada) is a Crown corporation and Canada's central bank. Chartered in 1934 under the ''Bank of Canada Act'', it is responsible for formulating Canada's monetary policy,OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: Ca ...

in Ottawa gave $25,000. The U.S. government quickly voted for one million dollars in relief supplies which were immediately rushed to the area, including supplies for food kitchens and many thousands of tents that city dwellers would occupy the next several years. These relief efforts were not enough to get families on their feet again, and consequently the burden was placed on wealthier members of the city, who were reluctant to assist in the rebuilding of homes they were not responsible for. All residents were eligible for daily meals served from a number of communal soup kitchens, and citizens as far away as Idaho and Utah were known to send daily loaves of bread to San Francisco as relief supplies were coordinated by the railroads.

Insurance payments

Insurance companies, faced with staggering claims of $250 million, paid out between $235 million and $265 million on policyholders' claims, often for fire damage only, since shake damage from earthquakes was excluded from coverage under most policies.Aetna At-A-Glance: Aetna History", Aetna company information At least 137 insurance companies were directly involved and another 17 as reinsurers. Twenty companies went bankrupt.

Lloyd's of London

Lloyd's of London, generally known simply as Lloyd's, is an insurance and reinsurance market located in London, England. Unlike most of its competitors in the industry, it is not an insurance company; rather, Lloyd's is a corporate body gov ...

reports having paid all claims in full, more than $50 million, thanks to the leadership of Cuthbert Heath. Insurance companies in Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since the ...

, report paying every claim in full, with the Hartford Fire Insurance Company paying over $11 million and Aetna Insurance Company

Aetna Inc. () is an American managed health care company that sells traditional and consumer directed health care insurance and related services, such as medical, pharmaceutical, dental, behavioral health, long-term care, and disability plans, ...

almost $3 million. The insurance payments heavily affected the international financial system. Gold transfers from European insurance companies to policyholders in San Francisco led to a rise in interest rates, subsequently to a lack of available loans and finally to the Knickerbocker Trust Company

The Knickerbocker Trust was a bank based in New York City that was, at one time, among the largest banks in the United States. It was a central player in the Panic of 1907.

History

The bank was chartered in 1884 by Frederick G. Eldridge, a frie ...

crisis of October 1907 which led to the Panic of 1907

The Panic of 1907, also known as the 1907 Bankers' Panic or Knickerbocker Crisis, was a financial crisis that took place in the United States over a three-week period starting in mid-October, when the New York Stock Exchange fell almost 50% from ...

.

After the 1906 earthquake, global discussion arose concerning a legally flawless exclusion of the earthquake hazard from fire insurance contracts. It was pressed ahead mainly by re-insurers. Their aim: a uniform solution to insurance payouts resulting from fires caused by earthquakes. Until 1910, a few countries, especially in Europe, followed the call for an exclusion of the earthquake hazard from all fire insurance contracts. In the U.S., the question was discussed differently. But the traumatized public reacted with fierce opposition. On August 1, 1909, the California Senate

The California State Senate is the upper house of the California State Legislature, the lower house being the California State Assembly. The State Senate convenes, along with the State Assembly, at the California State Capitol in Sacramento.

Due ...

enacted the California Standard Form of Fire Insurance Policy, which did not contain any earthquake clause. Thus the state decided that insurers would have to pay again if another earthquake was followed by fires. Other earthquake-endangered countries followed the California example.

Centennial commemorations

The 1906 Centennial Alliance was set up as a clearing-house for various centennial events commemorating the earthquake. Award presentations, religious services, aNational Geographic

''National Geographic'' (formerly the ''National Geographic Magazine'', sometimes branded as NAT GEO) is a popular American monthly magazine published by National Geographic Partners. Known for its photojournalism, it is one of the most widely ...

TV movie, a projection of fire onto the Coit Tower, memorials, and lectures were part of the commemorations. The USGS

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, a ...

Earthquake Hazards Program

The 2004 re-authorization of National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program (NEHRP) directed that the Director of the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) establish the Advisory Committee on Earthquake Hazards Reduction (ACEHR ...

issued a series of Internet documents, and the tourism industry promoted the 100th anniversary as well.

Eleven survivors of the 1906 earthquake attended the centennial commemorations in 2006, including Irma Mae Weule (1899–2008), who was the oldest survivor of the quake at the time of her death in August 2008, aged 109. Vivian Illing (1900–2009) was believed to be the second-oldest survivor at the time of her death, aged 108, leaving Herbert Hamrol (1903–2009) as the last known remaining survivor at the time of his death, aged 106. Another survivor, Libera Armstrong (1902–2007), attended the 2006 anniversary but died in 2007, aged 105. Shortly after Hamrol's death, two additional survivors were discovered. William Del Monte, then 103, and Jeanette Scola Trapani (1902–2009), 106, stated that they stopped attending events commemorating the earthquake when it became too much trouble for them. Del Monte and another survivor, Rose Cliver (1902–2012), then 106, attended the earthquake reunion celebration on April 18, 2009, the 103rd anniversary of the earthquake. Nancy Stoner Sage (1905–2010) died, aged 105, in Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

just three days short of the 104th anniversary of the earthquake on April 18, 2010. Del Monte attended the event at Lotta's Fountain in 2010. 107-year-old George Quilici (1905–2012) died in May 2012, and 113-year-old Ruth Newman (1901–2015) in July 2015. William Del Monte (1906–2016), who died 11 days shy of his 110th birthday, was thought to be the last survivor.

In 2005 the National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation, each selected for its historical, cultural and aesthetic contributions since the NFPB’s inception i ...

added '' San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906'', a newsreel documentary made soon after the earthquake, to its list of American films worthy of preservation.

Panoramas

In popular culture

*Will Irwin

William Henry Irwin (September 14, 1873 – February 24, 1948) was an American author, writer and journalist who was associated with the muckrakers.

Early life

Irwin was born in 1873 in Oneida, New York. In his early childhood, the Irwin famil ...

, '' The City That Was'', a series of 1906 articles for '' The Sun'', in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, and later as a booklet.

* The earthquake is shown towards the end of MGM's 1936 film ''San Francisco''

* The earthquake is a major event in Tony Kushner

Anthony Robert Kushner (born July 16, 1956) is an American author, playwright, and screenwriter. Lauded for his work on stage he's most known for his seminal work ''Angels in America'' which earned a Pulitzer Prize and a Tony Award. At the turn ...

's play ''Angels in America

''Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes'' is a two-part play by American playwright Tony Kushner. The work won numerous awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, the Tony Award for Best Play, and the Drama Desk Award for O ...

''.

* The earthquake is depicted near the beginning of the 1932 film ''Frisco Jenny

''Frisco Jenny'' is a 1932 American pre-Code drama film starring Ruth Chatterton and Louis Calhern, and directed by William A. Wellman. Its storyline bears a resemblance to Chatterton's previous hit film, ''Madame X''.

Plot

In 1906 San Francis ...

''.

See also

*Arnold Genthe

Arnold Genthe (8 January 1869 – 9 August 1942) was a German-American photographer, best known for his photographs of San Francisco's Chinatown, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, and his portraits of noted people, from politicians and socialite ...

, earthquake photographer

* George R. Lawrence

George Raymond Lawrence (February 24, 1868 – December 15, 1938) was a commercial photographer of northern Illinois. After years of experience building Kite flying, kites and balloons for aerial panoramic photography, Lawrence turned to aviation ...

, earthquake photographer

* Committee of Fifty (1906)

This Committee of Fifty, sometimes referred to as Committee of Safety, Citizens' Committee of Fifty or Relief and Restoration Committee of Law and Order, was called into existence by Mayor Eugene Schmitz during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. T ...

* Earthquake engineering

Earthquake engineering is an interdisciplinary branch of engineering that designs and analyzes structures, such as buildings and bridges, with earthquakes in mind. Its overall goal is to make such structures more resistant to earthquakes. An earth ...

* List of earthquakes in 1906

This is a list of earthquakes in 1906. Only magnitude 6.0 or greater earthquakes appear on the list. Exceptions to this are earthquakes which have caused death, injury or damage. Events which occurred in remote areas will be excluded from the l ...

* List of earthquakes in California

The earliest known California earthquake was documented in 1769 by the Spanish explorers and Catholic missionaries of the Portolá expedition as they traveled northward from San Diego along the Santa Ana River near the present site of Los Angeles ...

* List of earthquakes in the United States

The following is a list of notable earthquakes and tsunamis which had their epicenter in areas that are now part of the United States with the latter affecting areas of the United States. Those in ''italics'' were not part of the United States whe ...

* List of disasters in the United States by death toll

This list of United States disasters by death toll includes disasters that occurred either in the United States, at diplomatic missions of the United States, or incidents outside of the United States in which a number of U.S. citizens were killed ...

* List of fires

This article is a list of notable fires.

Town and city fires

Building or structure fires

Transportation fires

Mining (including oil and natural gas drilling) fires

This is a partial list of fire due to mining: man-made structures to extra ...

Notes

References

* ''Double Cone Quarterly'', Fall Equinox, volume VII, Number 3 (2004). * * * * * * * * * * * *Winchester, Simon

Simon Winchester (born 28 September 1944) is a British-American author and journalist. In his career at ''The Guardian'' newspaper, Winchester covered numerous significant events, including Bloody Sunday and the Watergate Scandal. Winchester has ...

, ''A Crack in the Edge of the World: America and the Great California Earthquake of 1906''. HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 2005.

*

;Contemporary disaster accounts

*

*

*

*

* London, Jack"The Story of An Eyewitness"

London's report from the scene. Originally published in ''

Collier's Magazine

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened in 1905 to ''Colli ...

'', May 5, 1906.

*

*

*

External links

The Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake

– United States Geological Survey *

The 1906 Earthquake and Fire

– National Archives

Before and After the Great Earthquake and Fire: Early Films of San Francisco, 1897–1916

–

American Memory

American Memory is an internet-based archive for public domain image resources, as well as Sound recording, audio, video, and archived Web content. Published by the Library of Congress, the archive launched on October 13, 1994, after $13 million w ...

at the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

A geologic tour of the San Francisco earthquake, 100 years later

–

American Geological Institute

The American Geosciences Institute (AGI) is a nonprofit federation of about 50 geoscientific and professional organizations that represents geologists, geophysicists, and other earth scientists. The organization was founded in 1948. The name of ...

The Great 1906 Earthquake and Fire

–

Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

Virtual may refer to:

* Virtual (horse), a thoroughbred racehorse

* Virtual channel, a channel designation which differs from that of the actual radio channel (or range of frequencies) on which the signal travels

* Virtual function, a programming ...

website

The Great 1906 Earthquake and Fire

–

Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library in the center of the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, is the university's primary special-collections library. It was acquired from its founder, Hubert Howe Bancroft, in 1905, with the proviso that it retai ...

Mark Twain and the San Francisco Earthquake

– Shapell Manuscript Foundation

Several videos of the aftermath

–

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

''San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906''

Seismographs of the earthquake taken from the Lick Observatory from the Lick Observatory Records Digital Archive, UC Santa Cruz Library's Digital Collections

– The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

– Photographic account of earthquake and fire aftermath from well-known North Beach photographer

– USGS * {{DEFAULTSORT:1906 San Francisco Earthquake San Francisco earthquake, 1906

1906

Events

January–February

* January 12 – Persian Constitutional Revolution: A nationalistic coalition of merchants, religious leaders and intellectuals in Persia forces the shah Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar to grant a constitution, ...

San Francisco, 1906

Fires in California

San Francisco earthquake

At 05:12 Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (''Extreme''). High-intensity sha ...

1900s in San Francisco

1906 natural disasters in the United States

1906 tsunamis

April 1906 events

Supershear earthquakes

Articles containing video clips