Graham Gore on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Graham Gore (c. 1809 – between 28 May 1847 and 25 April 1848) was an English officer of the

Graham Gore (c. 1809 – between 28 May 1847 and 25 April 1848) was an English officer of the

In 1822 with his older brother he entered the Royal Naval College in

In 1822 with his older brother he entered the Royal Naval College in  Having passed his examination in 1829, during 1836 to 1837 Gore served as Mate on HMS ''Terror'' under the command of Captain Sir

Having passed his examination in 1829, during 1836 to 1837 Gore served as Mate on HMS ''Terror'' under the command of Captain Sir

Scott Polar Research Institute Archives, In October 1840 Gore was ordered to HMS ''Herald'' at the East India Station. Travelling to

In October 1840 Gore was ordered to HMS ''Herald'' at the East India Station. Travelling to

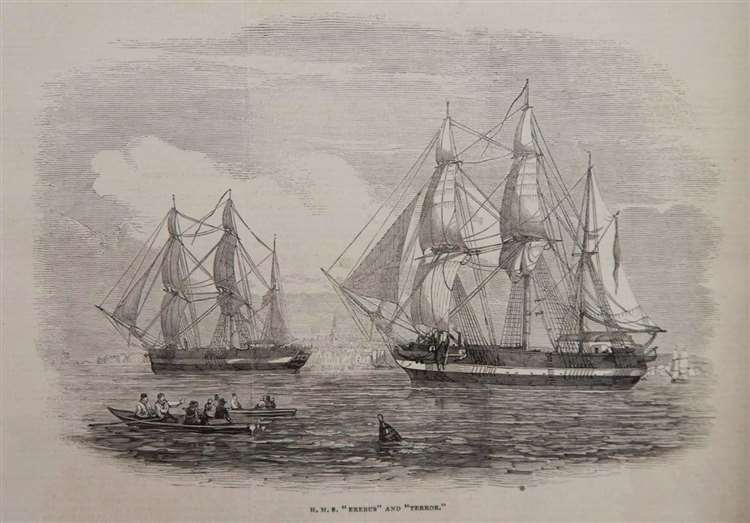

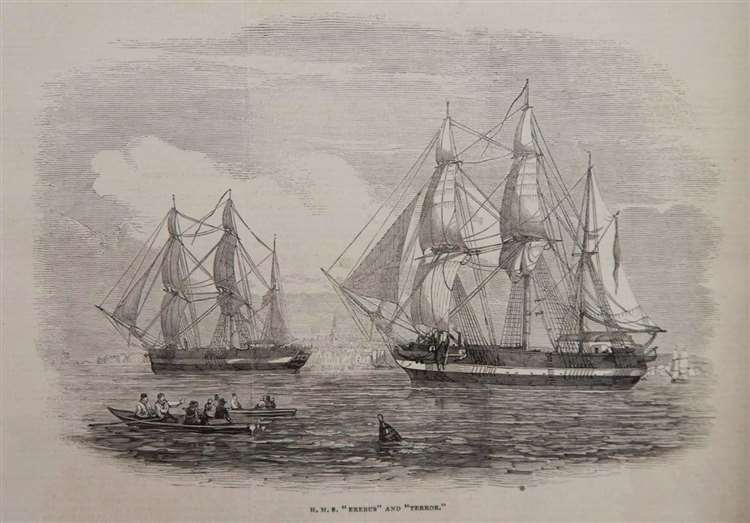

On 8 March 1845 Gore joined the crew of the discovery ship ''Erebus'' on its

On 8 March 1845 Gore joined the crew of the discovery ship ''Erebus'' on its  At the Whalefish Islands in

At the Whalefish Islands in

The Victory Point Note was found 11 years later in May 1859 by William Hobson (Lieutenant on the McClintock Arctic expedition) placed in a cairn on the northwestern coast of King William Island. It contains the only surviving information we have concerning the fate of Gore and the rest of the crew and consists of two parts written on a pre-printed Admiralty form. The first part was written after the first overwintering in 1847, while the second part was added one year later. From the second part it can be inferred that the document was first deposited in a different cairn previously erected by

The Victory Point Note was found 11 years later in May 1859 by William Hobson (Lieutenant on the McClintock Arctic expedition) placed in a cairn on the northwestern coast of King William Island. It contains the only surviving information we have concerning the fate of Gore and the rest of the crew and consists of two parts written on a pre-printed Admiralty form. The first part was written after the first overwintering in 1847, while the second part was added one year later. From the second part it can be inferred that the document was first deposited in a different cairn previously erected by

Gore Point on

Gore Point on

,

Graham Gore (c. 1809 – between 28 May 1847 and 25 April 1848) was an English officer of the

Graham Gore (c. 1809 – between 28 May 1847 and 25 April 1848) was an English officer of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

and polar explorer who participated in two expeditions to the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

and a survey of the coastline of Australia aboard HMS ''Beagle''. In 1845 he served under Sir John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. After serving in wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and through ...

as First Lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a s ...

(the third most senior rank) on the during the Franklin expedition

Franklin's lost expedition was a failed British voyage of Arctic exploration led by Captain (Royal Navy), Captain Sir John Franklin that departed England in 1845 aboard two ships, and , and was assigned to traverse the last unnavigated sect ...

to discover the Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arct ...

, which ended with the loss of all 129 officers and crewmen in mysterious circumstances.

Early life

Graham Gore was born inPlymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

in Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

in about 1809, the second eldest of six children of Sarah Gilmour (1777–1857) and John Gore (1774–1853). His was a family of distinguished naval officers, particularly in the field of exploration. His father was a Royal Navy Officer who reached the rank of captain on 19 July 1821, retiring in that rank on 1 October 1846, later promoted to Retired Rear Admiral on 8 March 1852. He moved to Australia in 1834 as one of the first free settlers. His paternal grandfather was the British-American naval officer Captain John Gore who circumnavigated the globe four times with the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

in the 18th century and accompanied Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

in his discoveries in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

.

Gore's family moved to Barnstaple

Barnstaple ( or ) is a river-port town in North Devon, England, at the River Taw's lowest crossing point before the Bristol Channel. From the 14th century, it was licensed to export wool and won great wealth. Later it imported Irish wool, bu ...

in Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

from where his father, anxious for his son to serve in the Royal Navy, wrote a letter to the Admiralty "to enter my son Graham Gore, age 11 years, educated by myself and Mr. Bridge, Schoolmaster of Barnstaple." While there were concerns that the boy was too young permission was granted for him to join his father and older brother John Gore (1807–1830) as a volunteer on board ''Dotterel''. Graham Gore joined the ship on 27 April 1820 with the rank of Midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Afr ...

, serving on board for a year with his father, brother and Francis Crozier

Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier (17 October 1796 – disappeared 26 April 1848) was an Irish officer of the Royal Navy and polar explorer who participated in six expeditions to the Arctic and Antarctic. In May 1845, he was second-in-command ...

until Crozier was appointed to HMS ''Fury''. The three Gores remained aboard the ship until she paid off on 20 July 1821 when it would appear that Graham Gore returned to the family home for the following year where he presumably continued his education under the guidance of his father.

Graham Gore was an accomplished artist and a keen shot and huntsman, both skills he was to put to good use during his naval career.

Naval career

In 1822 with his older brother he entered the Royal Naval College in

In 1822 with his older brother he entered the Royal Naval College in Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

. He after served on HMS ''Albion'' under Captain John Acworth Ommanney. Gore saw action in October 1827 on board ''Albion'' when she was part of a combined British-French-Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

fleet under the command of Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Edward Codrington

Sir Edward Codrington, (27 April 1770 – 28 April 1851) was a British admiral, who took part in the Battle of Trafalgar and the Battle of Navarino.

Early life and career

The youngest of three brothers born to Edward Codrington the elder (1732 ...

at the Battle of Navarino

The Battle of Navarino was a naval battle fought on 20 October (O. S. 8 October) 1827, during the Greek War of Independence (1821–29), in Navarino Bay (modern Pylos), on the west coast of the Peloponnese peninsula, in the Ionian Sea. Allied fo ...

, where a Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

-Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

ian fleet was obliterated, securing Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

independence. This was to prove to be the last ever sea battle between Nelson-era wooden sailing ships.

Having passed his examination in 1829, during 1836 to 1837 Gore served as Mate on HMS ''Terror'' under the command of Captain Sir

Having passed his examination in 1829, during 1836 to 1837 Gore served as Mate on HMS ''Terror'' under the command of Captain Sir George Back

Admiral Sir George Back (6 November 1796 – 23 June 1878) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer of the Canadian Arctic, naturalist and artist. He was born in Stockport.

Career

As a boy, he went to sea as a volunteer in the frigat ...

during the exploration of the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

at Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

for which he received his first award of the Arctic Medal. The expedition aimed to enter Repulse Bay

Repulse Bay or Tsin Shui Wan is a bay in the southern part of Hong Kong Island, located in the Southern District, Hong Kong. It is one of the most expensive residential areas in the world.

Geography

Repulse Bay is located in the southern ...

where it would send out landing parties to ascertain whether the Boothia Peninsula

Boothia Peninsula (; formerly ''Boothia Felix'', Inuktitut ''Kingngailap Nunanga'') is a large peninsula in Nunavut's northern Canadian Arctic, south of Somerset Island. The northern part, Murchison Promontory, is the northernmost point o ...

was an island or a peninsula. ''Terror'' was trapped by ice near Southampton Island

Southampton Island (Inuktitut: ''Shugliaq'') is a large island at the entrance to Hudson Bay at Foxe Basin. One of the larger members of the Arctic Archipelago, Southampton Island is part of the Kivalliq Region in Nunavut, Canada. The area of the ...

, and did not reach Repulse Bay. At one point, the ice forced her up the face of a cliff. She was trapped in the ice for ten months. Captain Back's diary says that Christmas Day dinner 1836 was a "haunch of reindeer shot by Mr Gore". Gore gained his first commission in January 1837, when he was appointed Lieutenant.Graham Gore collectionScott Polar Research Institute Archives,

University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

In the spring of 1837 an encounter with an iceberg further damaged the ship. She nearly sank on her return journey across the Atlantic, and was in a sinking condition by the time Back was able to beach the ship on the coast of Ireland on 21 September. Such was the damage that the ''Terror'' had to kept intact by passing chains around the hull.

Lieutenant Gore served on the ''Modeste'' in November 1837 and the ''Volage'' in January 1838, on the latter ship seeing action during the Aden Expedition

The Aden Expedition was a naval operation that the British Royal Navy carried out in January 1839. Following Britain's decision to acquire the port of Aden as a coaling station for the steamers sailing the new Suez-Bombay route, the sultan of ...

in 1839; he was in action against the Bogue Forts and the Capture of Chusan

The First Capture of Chusan () by British forces in China occurred on 5–6 July 1840 during the First Opium War. The British captured Chusan (Zhoushan), the largest island of an archipelago of that name.

Background

The Kangxi Emperor esta ...

in 1840 during the First Opium War

The First Opium War (), also known as the Opium War or the Anglo-Sino War was a series of military engagements fought between Britain and the Qing dynasty of China between 1839 and 1842. The immediate issue was the Chinese enforcement of the ...

.

In October 1840 Gore was ordered to HMS ''Herald'' at the East India Station. Travelling to

In October 1840 Gore was ordered to HMS ''Herald'' at the East India Station. Travelling to Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

in Australia to join his ship Gore could not find the ''Herald'' so instead joined the crew of ''HMS Beagle

HMS ''Beagle'' was a 10-gun brig-sloop of the Royal Navy, one of more than 100 ships of this class. The vessel, constructed at a cost of £7,803 (roughly equivalent to £ in 2018), was launched on 11 May 1820 from the Woolwich Dockyard on th ...

'', then under the command of Captain John Lort Stokes

Admiral John Lort Stokes, RN (1 August 1811 – 11 June 1885)Although 1812 is frequently given as Stokes's year of birth, it has been argued by author Marsden Hordern that Stokes was born in 1811, citing a letter by fellow naval officer Crawford ...

. This was the same ''Beagle'' on which Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

had made his famous researches. While in Australia Gore had the opportunity to visit his parents, sisters and brother at Lake Bathurst

Lake Bathurst ( Aboriginal: ''Bundong'') is a shallow lake located south-east of Goulburn, New South Wales in Australia. It is also the name of a nearby locality in the Goulburn Mulwaree Council.

Features and location

The surface area of the la ...

. During its expedition with Gore among the crew the ''Beagle'' surveyed large sections of the coast of Australia.

An accomplished artist, his painting of Burial Reach and Flinders River

The Flinders River is the longest river in Queensland, Australia, at approximately . It was named in honour of the explorer Matthew Flinders. The catchment is sparsely populated and mostly undeveloped. The Flinders rises on the western slopes ...

made during the voyage is held by the National Library of Australia

The National Library of Australia (NLA), formerly the Commonwealth National Library and Commonwealth Parliament Library, is the largest reference library in Australia, responsible under the terms of the ''National Library Act 1960'' for "mainta ...

. Later during the expedition Gore was injured when the gun he was using to shoot cockatoo

A cockatoo is any of the 21 parrot species belonging to the family Cacatuidae, the only family in the superfamily Cacatuoidea. Along with the Psittacoidea (true parrots) and the Strigopoidea (large New Zealand parrots), they make up the ord ...

s from a gig to augment the crew's diet exploded in his hands. Captain Stokes reported that Gore, "my much-valued friend...nearly blew off his own hand whilst shooting" and ended up "stretched at his length at the bottom of the boat". Stunned but fortunately with only a minor injury to his hand, Gore could only quietly remark, "Killed the bird..." This comment Stokes described as "an expression truly characteristic of a sportsman". Stokes clearly liked Gore, later writing in his memoirs, "There was only one drawback to the pleasure I experienced on arriving in England, -- namely, that Lieut. G. Gore did not obtain his promotion, but was compelled to seek it by a second voyage to the North Pole."

In December 1843 Gore was transferred to the steam frigate HMS ''Cyclops'' on which he was "employed for particular service".

Franklin expedition

On 8 March 1845 Gore joined the crew of the discovery ship ''Erebus'' on its

On 8 March 1845 Gore joined the crew of the discovery ship ''Erebus'' on its Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arct ...

explorative expedition. He was the third most senior officer on board after Captain Sir John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. After serving in wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and through ...

and Commander James Fitzjames

James Fitzjames (27 July 1813 – disappeared 26 April 1848) was a British Royal Navy officer who participated in two major exploratory expeditions, the Euphrates Expedition and the Franklin Expedition.

Early life

He was of illegitima ...

. The latter described Gore as a "man of great stability of character, a very good officer, and the sweetest of tempers." He was among twelve officers of the Franklin Expedition

Franklin's lost expedition was a failed British voyage of Arctic exploration led by Captain (Royal Navy), Captain Sir John Franklin that departed England in 1845 aboard two ships, and , and was assigned to traverse the last unnavigated sect ...

who posed for a daguerreotype

Daguerreotype (; french: daguerréotype) was the first publicly available photographic process; it was widely used during the 1840s and 1850s. "Daguerreotype" also refers to an image created through this process.

Invented by Louis Daguerre an ...

by photographer Richard Beard at the docks before sailing. The expedition set sail from Greenhithe

Greenhithe is a village in the Borough of Dartford in Kent, England, and the civil parish of Swanscombe and Greenhithe. It is located east of Dartford and west of Gravesend.

Area

In the past, Greenhithe's waterfront on the estuary of the riv ...

, Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, on the morning of 19 May 1845, with a crew of 24 officers and 110 men. The ships stopped briefly in Stromness

Stromness (, non, Straumnes; nrn, Stromnes) is the second-most populous town in Orkney, Scotland. It is in the southwestern part of Mainland Orkney. It is a burgh with a parish around the outside with the town of Stromness as its capital.

E ...

, Orkney Islands

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

, in northern Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

. From there they sailed to Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

with and a transport ship, ''Baretto Junior''; the passage to Greenland took 30 days.

At the Whalefish Islands in

At the Whalefish Islands in Disko Bay

Disko Bay ( kl, Qeqertarsuup tunua; da, DiskobugtenChristensen, N.O. & al.Elections in Greenland. ''Arctic Circular'', Vol. 4 (1951), pp. 83–85. Op. cit. "Northern News". ''Arctic'', Vol. 5, No. 1 (Mar 1952), pp. 58–59.) is a large ...

, on the west coast of Greenland, 10 oxen carried on ''Baretto Junior'' were slaughtered for fresh meat which was transferred to ''Erebus'' and ''Terror''. Crew members then wrote their last letters home, which recorded that Franklin had banned swearing and drunkenness. Gore sent Lady Jane Franklin

Jane, Lady Franklin (née Griffin; 4 December 1791 – 18 July 1875) was the second wife of the English explorer Sir John Franklin. During her husband's period as Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen's Land, she became known for her philanthropic ...

a watercolour and pen sketch of the ''Erebus'' being towed into Disko Bay by the tug ''Blazer'' on 31 May 1845. Five men were discharged due to sickness and sent home on ''Rattler'' and ''Barretto Junior'', reducing the final crew to 129 men. In late July 1845 the whaler

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Japa ...

s ''Prince of Wales'' (Captain Dannett) and ''Enterprise'' (Captain Robert Martin) encountered ''Terror'' and ''Erebus'' in Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay ( Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; kl, Avannaata Imaa; french: Baie de Baffin), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arct ...

, where they were waiting for good conditions to cross to Lancaster Sound

Lancaster Sound () is a body of water in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is located between Devon Island and Baffin Island, forming the eastern entrance to the Parry Channel and the Northwest Passage. East of the sound lies Baffin Bay ...

. The expedition was never seen again by Europeans.

Only limited information is available for subsequent events, pieced together over the next 150 years by other expeditions, explorers, scientists and interviews with Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories ...

. Franklin's men spent the winter of 1845–46 on Beechey Island

Beechey Island ( iu, Iluvialuit, script=Latn) is an island located in the Arctic Archipelago of Nunavut, Canada, in Wellington Channel. It is separated from the southwest corner of Devon Island by Barrow Strait. Other features include Wellington C ...

, where three crew members died and were buried. After travelling down Peel Sound through the summer of 1846, ''Terror'' and ''Erebus'' became trapped in ice off King William Island

King William Island (french: Île du Roi-Guillaume; previously: King William Land; iu, Qikiqtaq, script=Latn) is an island in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, which is part of the Arctic Archipelago. In area it is between and making it the ...

in September 1846 and are thought never to have sailed again. Gore was promoted to commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

on 9 November 1846.

In May 1847 Franklin sent Lieutenant Gore, First Mate Charles Frederick Des Voeux and six sailors on a landing party to explore the west side of King William Island

King William Island (french: Île du Roi-Guillaume; previously: King William Land; iu, Qikiqtaq, script=Latn) is an island in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, which is part of the Arctic Archipelago. In area it is between and making it the ...

. They were instructed to leave prewritten notes in cairns and then return to the ships after they had completed their exploration. The party of eight men left the ships on 24 May and after trekking for four days reached their first objective, Sir James Ross' Cairn at Victory Point. Here they left their first note (the Victory Point Note) before continuing south. This note provides the only first-hand information on the expedition's progress. The next day the men reached their second objective at Gore Point, but as there was no cairn at this location they built one and left another note inside before exploring further south following which they returned to the ships.Franklin Relics: A fiddle-pattern, silver dessert spoon owned by Lieutenant Graham Gore ('HMS Erebus')Royal Museums Greenwich

Royal Museums Greenwich is an organisation comprising four museums in Greenwich, east London, illustrated below. The Royal Museums Greenwich Foundation is a Private Limited Company by guarantee without share capital use of 'Limited' exemption, co ...

Collection These two notes would be found in their cairns in 1859 by William Hobson.

The Victory Point Note left by Gore was retrieved from its cairn on 25 April 1848 and a second part added before being signed by Fitzjames

The House of FitzJames Stuart, or simply FitzJames, is a noble house founded by James FitzJames, 1st Duke of Berwick. He was the illegitimate son of James II & VII, King of England, Scotland and Ireland, a monarch of the House of Stuart.Ruvigny, ...

and Crozier

A crosier or crozier (also known as a paterissa, pastoral staff, or bishop's staff) is a stylized staff that is a symbol of the governing office of a bishop or abbot and is carried by high-ranking prelates of Roman Catholic, Eastern Catholi ...

. This later addition informs us that the crew had wintered off King William Island in 1846–47 and 1847–48 and Franklin had died on 11 June 1847. Gore and 7 other officers and 15 men had also died before the remaining crew had abandoned their ships and planned to walk over the island and across the sea ice towards the Back River on the Canadian mainland, beginning on 26 April 1848. The Victory Point Note is the last known communication of the expedition.

From archeological finds, it is believed that all of the remaining crew died on the subsequent 400 km long march to Back River, most on the island. Thirty or forty men reached the northern coast of the mainland before dying, still hundreds of miles from the nearest outpost of Western civilization

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

.

Before the official proclamation of the deaths of Franklin's men in 1854, Gore was promoted to captain ''in absentia'' by the Admiralty.

The Victory Point Note

The Victory Point Note was found 11 years later in May 1859 by William Hobson (Lieutenant on the McClintock Arctic expedition) placed in a cairn on the northwestern coast of King William Island. It contains the only surviving information we have concerning the fate of Gore and the rest of the crew and consists of two parts written on a pre-printed Admiralty form. The first part was written after the first overwintering in 1847, while the second part was added one year later. From the second part it can be inferred that the document was first deposited in a different cairn previously erected by

The Victory Point Note was found 11 years later in May 1859 by William Hobson (Lieutenant on the McClintock Arctic expedition) placed in a cairn on the northwestern coast of King William Island. It contains the only surviving information we have concerning the fate of Gore and the rest of the crew and consists of two parts written on a pre-printed Admiralty form. The first part was written after the first overwintering in 1847, while the second part was added one year later. From the second part it can be inferred that the document was first deposited in a different cairn previously erected by James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and polar explorer known for his explorations of the Arctic, participating in two expeditions led by his uncle John Ross, and four led by William Edwa ...

in 1830 during John Ross' Second Arctic Expedition – at a location Ross named ''Victory Point''. The document is therefore referred to as the ''Victory Point Note''.

The first message is written within the body of the form and dates from 28 May 1847.

The second and final part is written largely on the margins of the form due to lack of remaining space on the document. It was presumably added on 25 April 1848 when the note in its protective metal cylinder was retrieved from its cairn before being replaced.

In 1859 Hobson found the second note deposited by Gore and his team in the cairn a few miles southwest at Gore Point using the same Admiralty form and containing an almost identical duplicate of the first message from 1847. This document did not contain the second message added by Fitzjames and Crozier in 1848 found on the Victory Point Note after the abandonment of the ships and subsequent recovery of the document from the Victory Point cairn.

From the handwriting it is assumed that all the messages were written by Commander James Fitzjames

James Fitzjames (27 July 1813 – disappeared 26 April 1848) was a British Royal Navy officer who participated in two major exploratory expeditions, the Euphrates Expedition and the Franklin Expedition.

Early life

He was of illegitima ...

. As he did not take part in the landing party which deposited the notes originally in 1847, it is inferred that both documents were originally filled out by Fitzjames on board the ships with Gore and Des Voeux adding their signatures as members of the landing party. This is further supported by the fact that both documents contain the same factual errors namely the wrong date of the wintering on Beechey Island.

As stated earlier, in 1834 Sarah and John Gore together with their three daughters Ann, Eliza and Charlotte and their youngest son Edward moved to Australia where they firstly lived at Parramatta

Parramatta () is a suburb and major Central business district, commercial centre in Greater Western Sydney, located in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is located approximately west of the Sydney central business district on the ban ...

near Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

. Later the family bought 1,165 acres of land near Lake Bathurst

Lake Bathurst ( Aboriginal: ''Bundong'') is a shallow lake located south-east of Goulburn, New South Wales in Australia. It is also the name of a nearby locality in the Goulburn Mulwaree Council.

Features and location

The surface area of the la ...

in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

where they lived in a house they named 'Gilmour', after Sarah's family.

On their deaths Sarah and Admiral John Gore were buried in St Saviours Cemetery in Goulburn

Goulburn ( ) is a regional city in the Southern Tablelands of the Australian state of New South Wales, approximately south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Canberra. It was proclaimed as Australia's first inland city through letters pate ...

. Their gravestone is inscribed with the only known memorial anywhere to their son. The inscription reads:

Legacy

Gore Point on

Gore Point on King William Island

King William Island (french: Île du Roi-Guillaume; previously: King William Land; iu, Qikiqtaq, script=Latn) is an island in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, which is part of the Arctic Archipelago. In area it is between and making it the ...

was named in his honour by Sir John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. After serving in wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and through ...

.Royal Navy Gores in Australia—part two,

National Library of Australia

The National Library of Australia (NLA), formerly the Commonwealth National Library and Commonwealth Parliament Library, is the largest reference library in Australia, responsible under the terms of the ''National Library Act 1960'' for "mainta ...

database

Graham Gore Peninsula in Nunavut

Nunavut ( , ; iu, ᓄᓇᕗᑦ , ; ) is the largest and northernmost Provinces and territories of Canada#Territories, territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the ''Nunavut Act'' ...

in Canada is named for him.

Gore is among the lost named on the Franklin monument erected in Waterloo Place in London in 1866. Inscribed 'To the great arctic navigator and his brave companions who sacrificed their lives in completing the discovery of the North West Passage. A.D. 1847 – 8', Gore's name can be found on the 'Erebus' plinth.

Gore appears as a character in the 2007 novel, ''The Terror'' by Dan Simmons

Dan Simmons (born April 4, 1948) is an American science fiction and horror writer. He is the author of the Hyperion Cantos and the Ilium/Olympos cycles, among other works which span the science fiction, horror, and fantasy genres, sometimes wi ...

, a fictionalized account of Franklin's lost expedition

Franklin's lost expedition was a failed British voyage of Arctic exploration led by Captain Sir John Franklin that departed England in 1845 aboard two ships, and , and was assigned to traverse the last unnavigated sections of the Northwest ...

, as well as the 2018 television adaptation, where he is played by Tom Weston-Jones

Tom Weston-Jones (born 29 June 1987) is an English actor, known for his role in ''Copper'' and for playing Richard Lee in ''Warrior'' (2019).

Early life and education

Weston-Jones was born in Burton-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, and was brought ...

. Episode 2 in the series is titled 'Gore'. He will also appear as a character in Kaliane Bradley's 2024 novel, The Ministry of Time.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gore, Graham 1800s births 1847 deaths 1840s missing person cases Royal Navy personnel of the First Opium War 19th-century explorers 19th-century Royal Navy personnel British polar explorers Recipients of the Polar Medal English explorers of North America Explorers of Canada Explorers of the Arctic Lost explorers Royal Navy officers Franklin's lost expedition British military personnel of the Greek War of Independence Military personnel from Plymouth, Devon