Gottlieb Burckhardt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Johann Gottlieb Burckhardt (24 December 1836 – 6 February 1907) was a

By 1860 Burckhardt had established a private medical practice in Basel. In 1862 he completed a post-doctoral

By 1860 Burckhardt had established a private medical practice in Basel. In 1862 he completed a post-doctoral

In December 1888 Burckhardt, who had little experience of surgery, performed what are commonly regarded as the first series of modern psychosurgical operations. He operated on six patients under his care, two women and four men aged between 26 and 51 whose condition was deemed to be intractable. Their diagnoses were, variously, one of chronic

In December 1888 Burckhardt, who had little experience of surgery, performed what are commonly regarded as the first series of modern psychosurgical operations. He operated on six patients under his care, two women and four men aged between 26 and 51 whose condition was deemed to be intractable. Their diagnoses were, variously, one of chronic

Swiss

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

*Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

*Swiss, North Carolina

* Swiss, West Virginia

*Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

* Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

* Swiss Internation ...

psychiatrist

A psychiatrist is a physician who specializes in psychiatry, the branch of medicine devoted to the diagnosis, prevention, study, and treatment of mental disorders. Psychiatrists are physicians and evaluate patients to determine whether their sy ...

and the medical director of a small mental hospital in the Swiss canton

Canton may refer to:

Administrative division terminology

* Canton (administrative division), territorial/administrative division in some countries, notably Switzerland

* Township (Canada), known as ''canton'' in Canadian French

Arts and ente ...

of Neuchâtel

, neighboring_municipalities= Auvernier, Boudry, Chabrey (VD), Colombier, Cressier, Cudrefin (VD), Delley-Portalban (FR), Enges, Fenin-Vilars-Saules, Hauterive, Saint-Blaise, Savagnier

, twintowns = Aarau (Switzerland), Besançon (Fra ...

. He is commonly regarded as having performed the first modern psychosurgical operation. Born in Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

, Switzerland, he trained as doctor at the Universities of Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

, Göttingen

Göttingen (, , ; nds, Chöttingen) is a college town, university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the Capital (political), capital of Göttingen (district), the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, t ...

and Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, receiving his medical doctorate in 1860. In the same year he took up a teaching post in the University of Basel and established a private practice in his hometown. He married in 1863 but the following year he was diagnosed with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

and gave up his practice and relocated to a region south of the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to C ...

in search of a cure. By 1866 he had made a full recovery and returned to Basel with the intention of devoting himself to the study of nervous diseases and their treatment. In 1875, he attained a post at the Waldau University Psychiatric Clinic in Bern, and from 1876 he lectured on mental diseases at the University of Bern

The University of Bern (german: Universität Bern, french: Université de Berne, la, Universitas Bernensis) is a university in the Switzerland, Swiss capital of Bern and was founded in 1834. It is regulated and financed by the Canton of Bern. It ...

. Beginning in this period, he published widely on his psychiatric and neurological research findings in the medical press, developing the thesis that mental illnesses had their origins in specific regions of the brain.

In 1882, he was appointed the medical director of a small, modern, and privately run psychiatric clinic at Marin, in the canton of Neuchâtel, where he was provided with a laboratory to continue his research. In 1888, he pioneered modern psychosurgery when he excised various brain regions from six psychiatric patients under his care. Aimed at relieving symptoms rather than effecting a cure, the theoretical basis of the procedure rested on his belief that psychiatric illnesses were the result of specific brain lesions. He reported the results at a Berlin medical conference in 1889, but the reception of his medical peers was decidedly negative and he was ridiculed. Burckhardt subsequently discontinued his research activities. Following the death of his wife in 1896, Burckhardt returned to Basel, where he established a sanatorium

A sanatorium (from Latin '' sānāre'' 'to heal, make healthy'), also sanitarium or sanitorium, are antiquated names for specialised hospitals, for the treatment of specific diseases, related ailments and convalescence. Sanatoriums are often ...

in 1900. He died seven years later from pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

.

Early life and education

Gottlieb Burckhardt was born on 24 December 1836 into a well-known family, theBurckhardt

Burckhardt, or (de) Bourcard in French, is a family of the Basel patriciate, descended from Christoph (Stoffel) Burckhardt (1490–1578), a merchant in cloth and silk originally from Münstertal, Black Forest, who received Basel citizenship i ...

, living in the Swiss city of Basel. His father, August Burckhardt (1809–1894), was a physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

. His mother was Katharina Jacot (1810–1843) from Montbéliard

Montbéliard (; traditional ) is a town in the Doubs Departments of France, department in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté Regions of France, region in eastern France, about from the border with Switzerland. It is one of the two Subprefectures in F ...

in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. Burckhardt's parents were married in 1833 and his mother gave birth to seven children prior to her death in 1843. Gottlieb Burckhardt was the third eldest child. In 1844 his father married Henrietta Maria Dick (1813–1871). She had five pregnancies and three surviving children. Burckhardt attended secondary school in Basel. His medical studies were conducted at the Universities of at Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

, Göttingen

Göttingen (, , ; nds, Chöttingen) is a college town, university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the Capital (political), capital of Göttingen (district), the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, t ...

and Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

. In 1860 he was conferred with a doctorate in medicine from the University of Basel. His doctoral thesis was on the epithelium

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is one of the four basic types of animal tissue, along with connective tissue, muscle tissue and nervous tissue. It is a thin, continuous, protective layer of compactly packed cells with a little intercellul ...

of the urinary tract

The urinary system, also known as the urinary tract or renal system, consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and the urethra. The purpose of the urinary system is to eliminate waste from the body, regulate blood volume and blood pressure, con ...

. As a student, he was described as popular, outgoing and musically talented.

Career

Early career, 1860–1888

By 1860 Burckhardt had established a private medical practice in Basel. In 1862 he completed a post-doctoral

By 1860 Burckhardt had established a private medical practice in Basel. In 1862 he completed a post-doctoral habilitation

Habilitation is the highest university degree, or the procedure by which it is achieved, in many European countries. The candidate fulfills a university's set criteria of excellence in research, teaching and further education, usually including a ...

in internal medicine and was granted the position of Privatdozent

''Privatdozent'' (for men) or ''Privatdozentin'' (for women), abbreviated PD, P.D. or Priv.-Doz., is an academic title conferred at some European universities, especially in German-speaking countries, to someone who holds certain formal qualific ...

at the University of Basel. The following year he married Elisabeth Heusler (1840–1896) and they had eight children together. In 1864, due to a diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis, Burckhardt was forced to give up his practice and he relocated to a southern locale near the Pyrenees. He recovered fully and published a study of climatic conditions in the region.

In 1866 Burckhardt returned to Basel and resolved to study the diseases of the nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes th ...

and their treatment with the new electrotherapies. His interest in this field had been fostered by Karl Ewald Hasse, a noted physician and friend of the Burckhardt family. In 1873 he was elected to the presidency of the Basel Medical Society. Two years later, in 1875, he received a post as a physician to the Waldau Psychiatric University Clinic in Berne; later that year he also published ''Die physiologische Diagnostik der Nervenkrankheiten'' (''Physiological Diagnostics of Nervous Diseases''), a 284-page monograph which detailed the results of his research on the use of electrotherapy for nervous disorders and the conductivity of the nervous system.

In 1876 he became a Privatdozent

''Privatdozent'' (for men) or ''Privatdozentin'' (for women), abbreviated PD, P.D. or Priv.-Doz., is an academic title conferred at some European universities, especially in German-speaking countries, to someone who holds certain formal qualific ...

at the University of Bern

The University of Bern (german: Universität Bern, french: Université de Berne, la, Universitas Bernensis) is a university in the Switzerland, Swiss capital of Bern and was founded in 1834. It is regulated and financed by the Canton of Bern. It ...

, where he lectured on nervous and mental diseases. This marks a highly productive period in his career as he became a regular contributor to several medical publications including the Swiss periodical ''Korrespondenzblatt für Schweizer Ärtze'' and produced articles on a variety of psychiatric and neurological topics.; In 1877 he published a historical treatment of psychiatric and psychological theories of the functional regions of the brain.; In this article he proposed that there were "cortical dispersion centres" which were "rooted in physiology and anatomy in the brain" and that these played a crucial role in the development of mental illness. Burckhardt drew inspiration for his hypothesis from recent advances which had shown the localisation of language faculties in the brain and he believed that mental diseases were also traceable to specific cortical centres. In the application of internal medicine to psychiatry, his research activities extended to an exploration of the relationship between mental illness and bodily temperature, blood pressure and pulse. In 1881 he published on the relationship between cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption and posited a connection between cerebral oxygen deprivation, pathological brain circulation and mental illness. While at Bern he also successfully submitted articles on the histological

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of biology which studies the microscopic anatomy of biological tissues. Histology is the microscopic counterpart to gross anatomy, which looks at larger structures vis ...

preparation of brain cells

Brain cells make up the functional tissue of the brain. The rest of the brain tissue is structural or connective called the stroma which includes blood vessels. The two main types of cells in the brain are neurons, also known as nerve cells, an ...

, sensory aphasia

Wernicke's aphasia, also known as receptive aphasia, sensory aphasia or posterior aphasia, is a type of aphasia in which individuals have difficulty understanding written and spoken language. Patients with Wernicke's aphasia demonstrate fluent ...

("word deafness"), the anatomy of the brain and cerebral localisation and forensic psychiatry

Forensic psychiatry is a subspeciality of psychiatry and is related to criminology. It encompasses the interface between law and psychiatry. According to the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, it is defined as "a subspecialty of psychiat ...

. From 1881 until his departure from the Waldau Clinic in 1882, Eugen Bleuler

Paul Eugen Bleuler (; ; 30 April 1857 – 15 July 1939) was a Swiss psychiatrist and humanist most notable for his contributions to the understanding of mental illness. He coined several psychiatric terms including "schizophrenia", "schizoid", ...

, who coined the term schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by continuous or relapsing episodes of psychosis. Major symptoms include hallucinations (typically hearing voices), delusions, and disorganized thinking. Other symptoms include social withdra ...

in 1908, served as his medical intern.

In August 1882 Burckhardt was appointed as the medical director of the Préfargier, a small but modern psychiatric clinic in Marin in the Swiss Canton of Neuchâtel. Prior to his arrival a laboratory was constructed at the clinic so that Burckhardt could continue his research into neuroanatomy

Neuroanatomy is the study of the structure and organization of the nervous system. In contrast to animals with radial symmetry, whose nervous system consists of a distributed network of cells, animals with bilateral symmetry have segregated, defin ...

and psychophysiology

Psychophysiology (from Ancient Greek, Greek , ''psȳkhē'', "breath, life, soul"; , ''physis'', "nature, origin"; and , ''wiktionary:-logia, -logia'') is the branch of psychology that is concerned with the physiology, physiological bases of psych ...

. In February 1884 he presented at the Préfargier asylum his findings on the heredity and the surface configuration of the brain. He continued to publish on psychiatric and neurological topics such as cerebral vascular movements, brain tumours and optic chiasm, traumatic hysteria, and writing disorders.

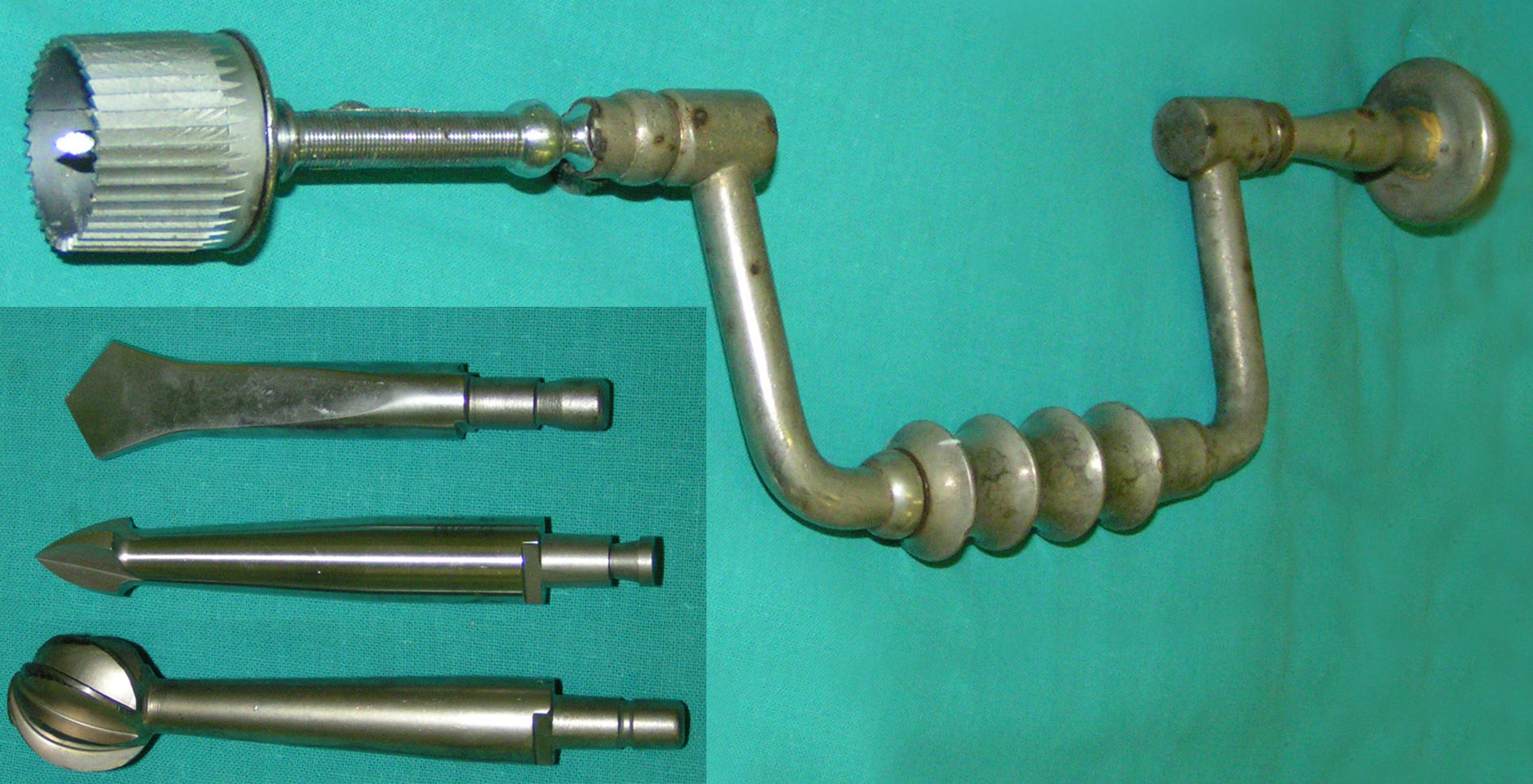

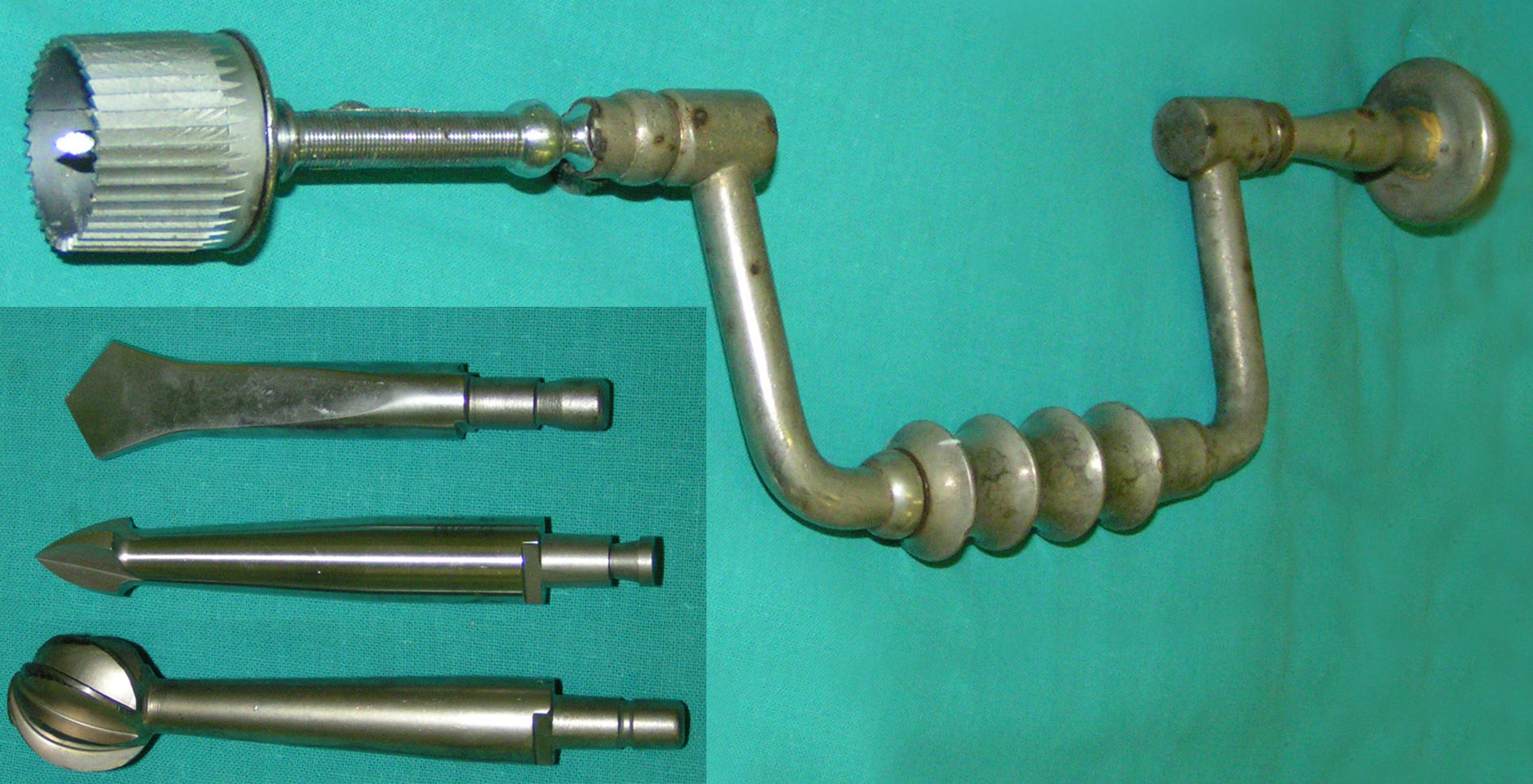

Psychosurgery, 1888–1891

In December 1888 Burckhardt, who had little experience of surgery, performed what are commonly regarded as the first series of modern psychosurgical operations. He operated on six patients under his care, two women and four men aged between 26 and 51 whose condition was deemed to be intractable. Their diagnoses were, variously, one of chronic

In December 1888 Burckhardt, who had little experience of surgery, performed what are commonly regarded as the first series of modern psychosurgical operations. He operated on six patients under his care, two women and four men aged between 26 and 51 whose condition was deemed to be intractable. Their diagnoses were, variously, one of chronic mania

Mania, also known as manic syndrome, is a mental and behavioral disorder defined as a state of abnormally elevated arousal, affect, and energy level, or "a state of heightened overall activation with enhanced affective expression together wit ...

, one of primary dementia

Dementia is a disorder which manifests as a set of related symptoms, which usually surfaces when the brain is damaged by injury or disease. The symptoms involve progressive impairments in memory, thinking, and behavior, which negatively affe ...

and four of ''primäre Verrücktheit'' (primary paranoid psychosis). This latter diagnosis was, according to the clinician-historian German E. Berrios, "a clinical category that (anachronistically) should be considered as tantamount to schizophrenia". Burckhardt's case notes recorded that the patients all exhibited serious psychiatric symptoms

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitti ...

such as auditory hallucinations

An auditory hallucination, or paracusia, is a form of hallucination that involves perceiving sounds without auditory stimulus. While experiencing an auditory hallucination, the affected person would hear a sound or sounds which did not come from t ...

, paranoid delusions

A delusion is a false fixed belief that is not amenable to change in light of conflicting evidence. As a pathology, it is distinct from a belief based on false or incomplete information, confabulation, dogma, illusion, hallucination, or some o ...

, aggression, excitement and violence. The operations excised regions of the cerebral cortex

The cerebral cortex, also known as the cerebral mantle, is the outer layer of neural tissue of the cerebrum of the brain in humans and other mammals. The cerebral cortex mostly consists of the six-layered neocortex, with just 10% consisting of ...

, specifically removing sections of the frontal, temporal, and tempoparietal lobes. The results were not overly encouraging as one patient died five days after the operation after experiencing epileptic convulsions, one improved but later died by suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

, another two showed no change, and the last two patients became "quieter". Complications consequent to the procedure included epilepsy

Epilepsy is a group of non-communicable neurological disorders characterized by recurrent epileptic seizures. Epileptic seizures can vary from brief and nearly undetectable periods to long periods of vigorous shaking due to abnormal electrical ...

(in two patients), motor weakness, "word deafness" and sensory aphasia

Aphasia is an inability to comprehend or formulate language because of damage to specific brain regions. The major causes are stroke and head trauma; prevalence is hard to determine but aphasia due to stroke is estimated to be 0.1–0.4% in th ...

. Only two patients are recorded as having no complications.

The theoretical basis of Burckhardt's action rested on three propositions. The first was that mental illness had a physical basis and that disordered minds were merely a reflection of disordered brains. Next, the associationist

Associationism is the idea that mental processes operate by the association of one mental state with its successor states. It holds that all mental processes are made up of discrete psychological elements and their combinations, which are believed ...

viewpoint of nerve functioning which conceived the nervous system as operating according to the following threefold division of labor: an input (or sensory or afferent) system, a connecting system which processed information and an output (or efferent or motor) system. The final assumption of Buckhardt's was that the brain was modular which meant that each mental module or mental faculty could be linked to a specific location in the brain. In accordance with such a viewpoint, Buckhardt postulated that lesions

A lesion is any damage or abnormal change in the tissue of an organism, usually caused by disease or trauma. ''Lesion'' is derived from the Latin "injury". Lesions may occur in plants as well as animals.

Types

There is no designated classifi ...

in specific areas of the brain might impact behavior in a specific manner. In other words, he thought that by cutting the connecting system, or second association state of brain's system of communication troubling symptoms might be alleviated without compromising either the nervous system's input or output systems. The procedure was aimed at relieving symptoms, not at curing a given mental disease. Thus, he wrote in 1891:

excitation and impulsive behaviour are due to the fact that from the sensory surfaces excitations abnormal in quality, quantity and intensity do arise, and do act on the motor surfaces, then an improvement could be obtained by creating an obstacle between the two surfaces. The extirpation of the motor or the sensory zone would expose us to the risk of grave functional disturbances and to technical difficulties. It would be more advantageous to practice the excision of a strip of cortex behind and on both sides of the motor zone creating thus a kind of ditch in the temporal lobe.Burckhardt attended the Berlin Medical Conference of 1889, which was also attended by such heavyweight psychiatrists as

Victor Horsley

Sir Victor Alexander Haden Horsley (14 April 1857 – 16 July 1916) was a British scientist and professor. He was born in Kensington, London. Educated at Cranbrook School, Kent, he studied medicine at University College London and in Berlin, Ge ...

, Valentin Magnan

Valentin Magnan (16 March 1835 – 27 September 1916) was a French psychiatrist active in the 19th-century.

Biography

Valentin Magnan was a native of Perpignan. He studied medicine in Lyon and Paris, where he was a student of Jules Baillar ...

and Emil Kraepelin

Emil Wilhelm Georg Magnus Kraepelin (; ; 15 February 1856 – 7 October 1926) was a German psychiatrist.

H. J. Eysenck's ''Encyclopedia of Psychology'' identifies him as the founder of modern scientific psychiatry, psychopharmacology and psychi ...

, and presented a paper on his brain operations. While his findings were subsequently widely reported in the psychiatric literature, the reviews were unremittingly negative and there was much ill ease generated by the surgical procedures he had performed. He also published the results of the procedure in 1891 in the periodical ''Allgemeine Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie und psychischgerichtliche Medicin'' in an article entitled 'Uber Rindenexcisionen, als Beitrag zur operativen Therapie der Psychosen' ('Concerning cortical excision, as a contribution to the surgical treatment of psychosis'). This paper was his last significant medical publication. Kraepelin, writing in 1893, was scathing of Burckhardt's attempts, and stated that "he urckhardtsuggested that restless patients could be pacified by scratching away the cerebral cortex." While Giuseppe Seppilli, an Italian professor of neuropsychiatry

Neuropsychiatry or Organic Psychiatry is a branch of medicine that deals with psychiatry as it relates to neurology, in an effort to understand and attribute behavior to the interaction of neurobiology and social psychology factors. Within neurop ...

, remarked in 1891 that Burckhardt's view of the brain as modular did not "fit in well with the view held by most xpertsthat the psychoses reflect a diffuse pathology of the cerebral cortex and an counter tothe conception of the psyche as a unitary entity".

Burckhardt wrote in 1891 that "Doctors are different by nature. One kind adheres to the old principle: first, do no harm ( primum non nocere); the other one says: it is better to do something than do nothing (melius anceps remedium quam nullum). I certainly belong to the second category". The French psychiatrist Armand Semelaigne responded that "an absence of treatment was better than a bad treatment". After the publication of his impressive 81 page monograph on the subject in 1891, Burckhardt ended his research and practice of psychosurgery due to the ridicule he received from his colleagues over the methods he had employed.

Commenting on his monograph in 1891 the British psychiatrist William Ireland concluded:

Dr. Burckhardt has a firm faith in the view that the mind is made up of a number of faculties, holding their seats in distinct portions of the brain. Where excess or irregularity of function occurs he seeks to check it by ablation of a portion of the irritated centres. He defends himself from the criticisms which are sure to be directed against his bold treatment by showing the desperate character of the prognosis of the patients upon whom the operations were performed ...Ireland doubted that any English psychiatrist would have the "hardihood" to follow the path taken by Burckhardt.

Later career and death, 1891–1907

Following the death of his wife and one of his sons, Burckhardt left his position at the Préfargier in 1896 and returned to Basel with the intention of setting up asanatorium

A sanatorium (from Latin '' sānāre'' 'to heal, make healthy'), also sanitarium or sanitorium, are antiquated names for specialised hospitals, for the treatment of specific diseases, related ailments and convalescence. Sanatoriums are often ...

.; This plan came to fruition in 1900 when the Sonnenhalde Clinic was opened in Riehen near Basel. Burckhardt served as the clinic's medical director from 1900 until 1904 and he remained a physician at the facility until his death from pneumonia on 6 February 1907. He was a marginal figure within the professional community of his psychiatric peers, attending few medical symposia and conferences in his discipline. However, he is often seen as a precursor to the Portuguese neurologist

Neurology (from el, νεῦρον (neûron), "string, nerve" and the suffix -logia, "study of") is the branch of medicine dealing with the diagnosis and treatment of all categories of conditions and disease involving the brain, the spinal c ...

, Egas Moniz, who performed the first leucotomy

A lobotomy, or leucotomy, is a form of neurosurgical treatment for psychiatric disorder or neurological disorder (e.g. epilepsy) that involves severing connections in the brain's prefrontal cortex. The surgery causes most of the connections to ...

, later known as lobotomy

A lobotomy, or leucotomy, is a form of neurosurgical treatment for psychiatric disorder or neurological disorder (e.g. epilepsy) that involves severing connections in the brain's prefrontal cortex. The surgery causes most of the connections to ...

, in 1936.; ;

Publications

* * * * * * * * * * * *Notes and references

Notes

Footnotes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Online sources

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Burckhardt, Gottlieb 1836 births 1907 deaths Swiss neurosurgeons Swiss psychiatrists Lobotomy Physicians from Basel-Stadt University of Basel alumni University of Göttingen alumniGottlieb

Gottlieb (formerly D. Gottlieb & Co.) was an American arcade game corporation based in Chicago, Illinois.

History

The main office and plant was located at 1140-50 N. Kostner Avenue until the early 1970s when a new modern plant and office was lo ...