Glades (Florida) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Everglades is a

The first written record of the Everglades was on Spanish maps made by

The first written record of the Everglades was on Spanish maps made by

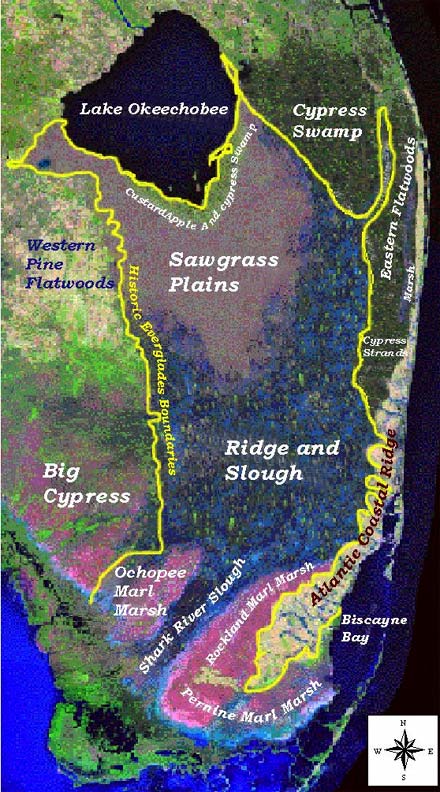

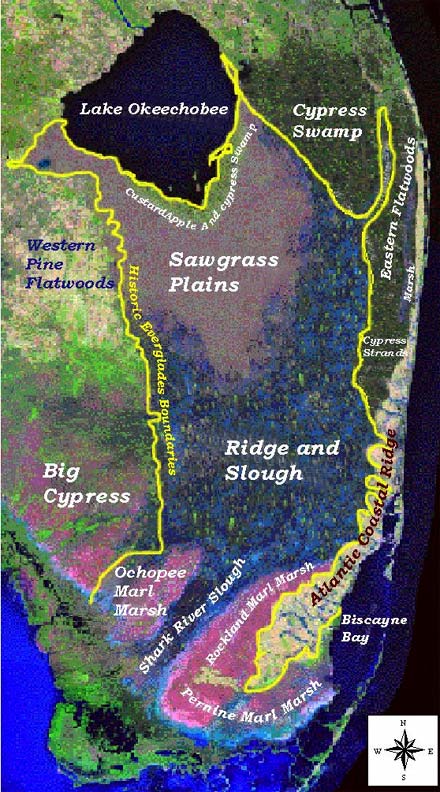

Five geologic formations form the surface of the southern portion of Florida: the

Five geologic formations form the surface of the southern portion of Florida: the

natural region

A natural region (landscape unit) is a basic geographic unit. Usually, it is a region which is distinguished by its common natural features of geography, geology, and climate.

From the ecology, ecological point of view, the naturally occurring fl ...

of tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

wetland

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free (anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in the soils. The ...

s in the southern portion of the U.S. state of Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, comprising the southern half of a large drainage basin

A drainage basin is an area of land where all flowing surface water converges to a single point, such as a river mouth, or flows into another body of water, such as a lake or ocean. A basin is separated from adjacent basins by a perimeter, t ...

within the Neotropical realm

The Neotropical realm is one of the eight biogeographic realms constituting Earth's land surface. Physically, it includes the tropical terrestrial ecoregions of the Americas and the entire South American temperate zone.

Definition

In bioge ...

. The system begins near Orlando

Orlando () is a city in the U.S. state of Florida and is the county seat of Orange County. In Central Florida, it is the center of the Orlando metropolitan area, which had a population of 2,509,831, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures rele ...

with the Kissimmee River

The Kissimmee River is a river in south-central Florida, United States that forms the north part of the Everglades wetlands area. The river begins at East Lake Tohopekaliga south of Orlando, flowing south through Lake Kissimmee into the large, sh ...

, which discharges into the vast but shallow Lake Okeechobee

Lake Okeechobee (), also known as Florida's Inland Sea, is the largest freshwater lake in the U.S. state of Florida. It is the tenth largest natural freshwater lake among the 50 states of the United States and the second-largest natural freshwat ...

. Water leaving the lake

A lake is an area filled with water, localized in a basin, surrounded by land, and distinct from any river or other outlet that serves to feed or drain the lake. Lakes lie on land and are not part of the ocean, although, like the much large ...

in the wet season forms a slow-moving river

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of wate ...

wide and over long, flowing southward across a limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

shelf to Florida Bay

Florida Bay is the bay located between the southern end of the Florida mainland (the Florida Everglades) and the Florida Keys in the United States. It is a large, shallow estuary that while connected to the Gulf of Mexico, has limited exchange o ...

at the southern end of the state. The Everglades experiences a wide range of weather patterns, from frequent flooding in the wet season to drought in the dry season. Throughout the 20th century, the Everglades suffered significant loss of habitat and environmental degradation

Environmental degradation is the deterioration of the environment (biophysical), environment through depletion of resources such as quality of air, water and soil; the destruction of ecosystems; habitat destruction; the extinction of wildlife; an ...

.

Human habitation in the southern portion of the Florida peninsula dates to 15,000 years ago. Before European colonization, the region was dominated by the native Calusa

The Calusa ( ) were a Native American people of Florida's southwest coast. Calusa society developed from that of archaic peoples of the Everglades region. Previous indigenous cultures had lived in the area for thousands of years.

At the time of ...

and Tequesta

The Tequesta (also Tekesta, Tegesta, Chequesta, Vizcaynos) were a Native American tribe. At the time of first European contact they occupied an area along the southeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. They had infrequent contact with Europeans a ...

tribes. With Spanish colonization, both tribes declined gradually during the following two centuries. The Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, an ...

, formed from mostly Creek people who had been warring to the North, assimilated other peoples and created a new culture after being forced from northern Florida into the Everglades during the Seminole Wars

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Geography of Florida, Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native Americans in the United States, Native American nation whi ...

of the early 19th century. After adapting to the region, they were able to resist removal by the United States Army.

Migrants to the region who wanted to develop plantations first proposed draining the Everglades in 1848, but no work of this type was attempted until 1882. Canals were constructed throughout the first half of the 20th century, and spurred the South Florida economy, prompting land development. In 1947, Congress formed the Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

, which built of canals, levee

A levee (), dike (American English), dyke (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English), embankment, floodbank, or stop bank is a structure that is usually soil, earthen and that often runs parallel (geometry), parallel to ...

s, and water control devices. The Miami metropolitan area

The Miami metropolitan area (also known as Greater Miami, the Tri-County Area, South Florida, or the Gold Coast) is the ninth largest metropolitan statistical area in the United States and the 34th largest metropolitan area in the world with a ...

grew substantially at this time and Everglades water was diverted to cities. Portions of the Everglades were transformed into farmland, where the primary crop was sugarcane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, Perennial plant, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar Sugar industry, production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with ...

. Approximately 50 percent of the original Everglades has been developed as agricultural or urban areas.

Following this period of rapid development and environmental degradation, the ecosystem began to receive notable attention from conservation groups in the 1970s. Internationally, UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

and the Ramsar Convention

The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat is an international treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of Ramsar sites (wetlands). It is also known as the Convention on Wetlands. It i ...

designated the Everglades a Wetland Area of Global Importance. The construction of a large airport north of Everglades National Park

Everglades National Park is an American national park that protects the southern twenty percent of the original Everglades in Florida. The park is the largest tropical wilderness in the United States and the largest wilderness of any kind east ...

was blocked when an environmental study found that it would severely damage the South Florida ecosystem. With heightened awareness and appreciation of the region, restoration began in the 1980s with the removal of a canal that had straightened the Kissimmee River. However, development and sustainability concerns have remained pertinent in the region. The deterioration of the Everglades, including poor water quality in Lake Okeechobee

Lake Okeechobee (), also known as Florida's Inland Sea, is the largest freshwater lake in the U.S. state of Florida. It is the tenth largest natural freshwater lake among the 50 states of the United States and the second-largest natural freshwat ...

, was linked to the diminishing quality of life in South Florida's urban areas. In 2000 the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan

The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) is the plan enacted by the U.S. Congress for the restoration of the Everglades ecosystem in southern Florida.

When originally authorized by the U.S. Congress in 2000, it was estimated that CERP ...

was approved by Congress to combat these problems, which at that time was considered the most expensive and comprehensive environmental restoration attempt in history; however, implementation faced political complications.

Names

The first written record of the Everglades was on Spanish maps made by

The first written record of the Everglades was on Spanish maps made by cartographer

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an im ...

s who had not seen the land. They named the unknown area between the Gulf and Atlantic coasts of Florida ''Laguna del Espíritu Santo'' ("Lake of the Holy Spirit"). The area was featured on maps for decades without having been explored. Writer James Grant Forbes stated in 1811, "The Indians represent he Southern points

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

as impenetrable; and the ritishsurveyors, wreckers, and coasters, had not the means of exploring beyond the borders of the sea coast, and the mouths of rivers".

British surveyor John Gerard de Brahm, who mapped the coast of Florida in 1773, called the area "River Glades". The name "Everglades" first appeared on a map in 1823, although it was also spelled as "Ever Glades" as late as 1851. The Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, an ...

call it ''Pahokee'', meaning "Grassy Water".Douglas, pp. 7–8. The region was labeled "''Pa-hai-okee''" on a U.S. military map from 1839, although it had earlier been called "Ever Glades" throughout the Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans and ...

.

A 2007 survey by geographers Ary J. Lamme and Raymond K. Oldakowski found that the "Glades" has emerged as a distinct vernacular region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and the interaction of humanity and t ...

of Florida. It comprises the interior areas and southernmost Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South, is the coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The coastal states that have a shoreline on the Gulf of Mexico are Texas, Louisiana, Mississ ...

of South Florida

South Florida is the southernmost region of the U.S. state of Florida. It is one of Florida's three most commonly referred to directional regions; the other two are Central Florida and North Florida. South Florida is the southernmost part of th ...

, largely corresponding to the Everglades itself. It is one of the most sparsely populated areas of the state.

Geology

Thegeology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

of South Florida, together with a warm, wet, subtropical/tropical climate, provides conditions well-suited for a large marshland ecosystem. Layers of porous and permeable limestone create water-bearing rock and soil that affect the climate, weather, and hydrology

Hydrology () is the scientific study of the movement, distribution, and management of water on Earth and other planets, including the water cycle, water resources, and environmental watershed sustainability. A practitioner of hydrology is calle ...

of South Florida.

The properties of the rock underneath the Everglades can be explained by the geologic history of the state. The crust underneath Florida was at one point part of the African region of the supercontinent Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final stages ...

. About 300 million years ago, North America merged with Africa, connecting Florida with North America. Volcanic activity centered on the eastern side of Florida covered the prevalent sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles ...

with igneous rock

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main The three types of rocks, rock types, the others being Sedimentary rock, sedimentary and metamorphic rock, metamorphic. Igneous rock ...

. Continental rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-grabe ...

ing began to separate North America from Gondwana about 180 million years ago. When Florida was part of Africa, it was initially above water, but during the cooler Jurassic Period

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

, the Florida Platform became a shallow marine environment in which sedimentary rocks were deposited. Through the Cretaceous Period

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of t ...

, most of Florida remained a tropical sea floor of varying depths. The peninsula has been covered by seawater at least seven times since the bedrock formed.Gleason, Patrick, Peter Stone, "Age, Origins, and Landscape Evolution of the Everglades Peatland" in ''Everglades: The Ecosystem and its Restoration'', Steven Davis and John Ogden, eds. (1994), St. Lucie Press.

Limestone and aquifers

Fluctuating sea levels compressed numerous layers of calcium carbonate, sand, and shells. The resulting permeablelimestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

formations that developed between 25 million and 70 million years ago created the Floridan Aquifer, which serves as the main source of fresh water for the northern portion of Florida. However, this aquifer lies beneath thousands of feet of impermeable sedimentary rock from Lake Okeechobee to the southern tip of the peninsula.

Five geologic formations form the surface of the southern portion of Florida: the

Five geologic formations form the surface of the southern portion of Florida: the Tamiami Formation

The Tamiami Formation is a Late Miocene to Pliocene geologic formation in the southwest Florida peninsula.

Age

Period: Neogene

Epoch: Late Miocene to Pliocene

Faunal stage: Clarendonian through Blancan ~13.06–2.588 mya, calculates to a ...

, Caloosahatchee Formation

The Caloosahatchee Formation is a geologic formation in Florida. It preserves fossils dating back to the Pleistocene.

See also

* List of fossiliferous stratigraphic units in Florida

See also

* Paleontology in Florida

References

*

{{D ...

, Anastasia Formation

The Anastasia Formation is a geologic formation deposited in Florida during the Late Pleistocene epoch.

Age

Period : Quaternary

Epoch: Pleistocene ~2.558 to 0.012 mya, calculates to a period of

Faunal stage: Blancan through early Rancholabre ...

, Miami Limestone

The Miami Limestone, originally called Miami Oolite, is a geologic formation of limestone in southeastern Florida.

Miami Limestone forms the Atlantic Coastal Ridge in southeastern Florida, near the coast in Palm Beach, Broward and Miami Dad ...

, and the Fort Thompson Formation

The Fort Thompson Formation is a Formation (stratigraphy), geologic formation in Florida. It preserves fossils dating back to the late Pleistocene. It was influenced by sea level changes.quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical form ...

, thick. It is named for the Tamiami Trail

The Tamiami Trail () is the southernmost of U.S. Highway 41 (US 41) from State Road 60 (SR 60) in Tampa to US 1 in Miami. A portion of the road also has the hidden designation of State Road 90 (SR 90).

The north� ...

that follows the upper bedrock of the Big Cypress Swamp, and underlies the southern portion of the Everglades. Between the Tamiami Formation and Lake Okeechobee is the Caloosahatchee Formation, named for the river over it. Much less permeable, this formation is highly calcitic and is composed of sandy shell marl, clay, and sand. Water underneath the Caloosahatchee Formation is typically very mineralized. Both the Tamiami and Caloosahatchee Formations developed during the Pliocene Epoch

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58UF & USDA (1948), p. 30–33. Underneath the metropolitan areas of

The consistent Everglades flooding is fed by the extensive

The consistent Everglades flooding is fed by the extensive

The climate of

The climate of

Water is the dominant force in the Everglades, shaping the land, vegetation, and animal life in South Florida. Starting at the

Water is the dominant force in the Everglades, shaping the land, vegetation, and animal life in South Florida. Starting at the

The underlying bedrock or limestone of the Everglades basin affects the ''hydroperiod'', or how long an area within the region stays flooded throughout the year. Longer hydroperiods are possible in areas that were submerged beneath seawater for longer periods of time, while the geology of Florida was forming. More water is held within the porous

The underlying bedrock or limestone of the Everglades basin affects the ''hydroperiod'', or how long an area within the region stays flooded throughout the year. Longer hydroperiods are possible in areas that were submerged beneath seawater for longer periods of time, while the geology of Florida was forming. More water is held within the porous

Alligators have created a niche in wet prairies. With their claws and snouts they dig at low spots and create ponds free of vegetation that remain submerged throughout the dry season. Alligator holes are integral to the survival of aquatic invertebrates, turtles, fish, small mammals, and birds during extended drought periods. The alligators then feed upon some of the animals that come to the hole.

Alligators have created a niche in wet prairies. With their claws and snouts they dig at low spots and create ponds free of vegetation that remain submerged throughout the dry season. Alligator holes are integral to the survival of aquatic invertebrates, turtles, fish, small mammals, and birds during extended drought periods. The alligators then feed upon some of the animals that come to the hole.

Small islands of trees growing on land raised between and above sloughs and prairies are called tropical hardwood

Small islands of trees growing on land raised between and above sloughs and prairies are called tropical hardwood

South Florida Multi-Species Recovery Plan: Pine rockland

", Retrieved May 3, 2008. The sandy floor of the pine forest is covered with dry pine needles that are highly flammable. South Florida slash pines are insulated by their bark to protect them from heat. Fire eliminates competing vegetation on the forest floor, and opens pine cones to germinate seeds. A period without significant fire can turn pineland into a hardwood hammock as larger trees overtake the slash pines. The

Cypress swamps can be found throughout the Everglades, but the largest covers most of

Cypress swamps can be found throughout the Everglades, but the largest covers most of

Eventually the water from Lake Okeechobee and The Big Cypress makes its way to the ocean. Mangrove trees are well adapted to the transitional zone of

Eventually the water from Lake Okeechobee and The Big Cypress makes its way to the ocean. Mangrove trees are well adapted to the transitional zone of

Much of the coast and the inner estuaries are built of mangroves; there is no border between the coastal marshes and the bay. Thus the marine ecosystems in

Much of the coast and the inner estuaries are built of mangroves; there is no border between the coastal marshes and the bay. Thus the marine ecosystems in

Following the demise of the Calusa and Tequesta, Native Americans in southern Florida were referred to as "Spanish Indians" in the 1740s, probably due to their friendlier relations with Spain. The Creek invaded the Florida peninsula; they conquered and assimilated what was left of pre-Columbian societies into the Creek Confederacy. They were joined by remnant Indian groups and formed the Seminole, a new tribe, by

Following the demise of the Calusa and Tequesta, Native Americans in southern Florida were referred to as "Spanish Indians" in the 1740s, probably due to their friendlier relations with Spain. The Creek invaded the Florida peninsula; they conquered and assimilated what was left of pre-Columbian societies into the Creek Confederacy. They were joined by remnant Indian groups and formed the Seminole, a new tribe, by

The military penetration of southern Florida offered the opportunity to map a poorly understood and largely unknown part of the country. An 1840 expedition into the Everglades offered the first printed account for the general public to read about the Everglades. The anonymous writer described the terrain the party was crossing:

The military penetration of southern Florida offered the opportunity to map a poorly understood and largely unknown part of the country. An 1840 expedition into the Everglades offered the first printed account for the general public to read about the Everglades. The anonymous writer described the terrain the party was crossing:

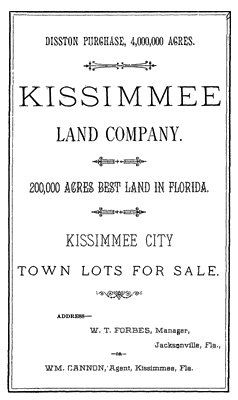

After the Civil War, a state agency called the Internal Improvement Fund (IIF), whose purpose was to improve Florida's roads, canals, and rail lines, was discovered to be deeply in debt. The IIF found a Pennsylvania real estate developer named

After the Civil War, a state agency called the Internal Improvement Fund (IIF), whose purpose was to improve Florida's roads, canals, and rail lines, was discovered to be deeply in debt. The IIF found a Pennsylvania real estate developer named

With the construction of canals, newly reclaimed Everglades land was promoted throughout the United States. Land developers sold 20,000 lots in a few months in 1912. Advertisements promised within eight weeks of arrival, a farmer could be making a living, although for many it took at least two months to clear the land. Some tried burning off the sawgrass or other vegetation, only to learn that the peat continued to burn. Animals and tractors used for plowing got mired in the muck and were useless. When the muck dried, it turned to a fine black powder and created dust storms. Although initially crops sprouted quickly and lushly, they just as quickly wilted and died, seemingly without reason.

The increasing population in towns near the Everglades hunted in the area. Raccoons and otters were the most widely hunted for their skins. Hunting often went unchecked; in one trip, a Lake Okeechobee hunter killed 250 alligators and 172 otters.

With the construction of canals, newly reclaimed Everglades land was promoted throughout the United States. Land developers sold 20,000 lots in a few months in 1912. Advertisements promised within eight weeks of arrival, a farmer could be making a living, although for many it took at least two months to clear the land. Some tried burning off the sawgrass or other vegetation, only to learn that the peat continued to burn. Animals and tractors used for plowing got mired in the muck and were useless. When the muck dried, it turned to a fine black powder and created dust storms. Although initially crops sprouted quickly and lushly, they just as quickly wilted and died, seemingly without reason.

The increasing population in towns near the Everglades hunted in the area. Raccoons and otters were the most widely hunted for their skins. Hunting often went unchecked; in one trip, a Lake Okeechobee hunter killed 250 alligators and 172 otters.

Two catastrophic hurricanes in

Two catastrophic hurricanes in

The idea of a national park for the Everglades was pitched in 1928, when a Miami land developer named Ernest F. Coe established the Everglades Tropical National Park Association. It had enough support to be declared a national park by Congress in 1934. It took another 13 years to be dedicated on December 6, 1947. One month before the dedication of the park, a former editor from ''

The idea of a national park for the Everglades was pitched in 1928, when a Miami land developer named Ernest F. Coe established the Everglades Tropical National Park Association. It had enough support to be declared a national park by Congress in 1934. It took another 13 years to be dedicated on December 6, 1947. One month before the dedication of the park, a former editor from ''

The C&SF established for the Everglades Agricultural Area—27 percent of the Everglades prior to development. In the late 1920s, agricultural experiments indicated that adding large amounts of

The C&SF established for the Everglades Agricultural Area—27 percent of the Everglades prior to development. In the late 1920s, agricultural experiments indicated that adding large amounts of

As a center for trade and travel between the U.S., the Caribbean, and South America, South Florida is especially vulnerable to

As a center for trade and travel between the U.S., the Caribbean, and South America, South Florida is especially vulnerable to

National Park Service and Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Retrieved on February 3, 2010. The Everglades hosts 1,392 exotic plant species actively reproducing in the region, outnumbering the 1,301 species considered native to South Florida. The melaleuca tree (''

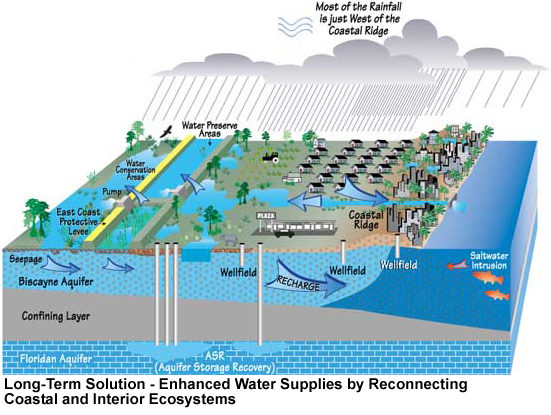

The Restudy came with a plan to stop the declining environmental quality, and this proposal was to be the most expensive and comprehensive ecological repair project in history. The

The Restudy came with a plan to stop the declining environmental quality, and this proposal was to be the most expensive and comprehensive ecological repair project in history. The  A series of biennial reports from the U.S. National Research Council have reviewed the progress of CERP. The fourth report in the series, released in 2012, found that little progress has been made in restoring the core of the remaining Everglades ecosystem; instead, most project construction so far has occurred along its periphery. The report noted that to reverse ongoing ecosystem declines, it will be necessary to expedite restoration projects that target the central Everglades, and to improve both the quality and quantity of the water in the ecosystem.National Research Council Report-in-Brief, Progress Toward Restoring the Everglades: The Fourth Biennial Review 2012, http://dels.nas.edu/Materials/Report-In-Brief/4296-Everglades To better understand the potential implications of the current slow pace of progress, the report assessed the current status of ten Everglades ecosystem attributes, including phosphorus loads, peat depth, and populations of snail kites, birds of prey that are endangered in South Florida. Most attributes received grades ranging from C (degraded) to D (significantly degraded), but the snail kite received a grade of F (near irreversible damage). The report also assessed the future trajectory of each ecosystem attribute under three restoration scenarios: improved water quality, improved hydrology, and improvements to both water quality and hydrology, which helped highlight the urgency of restoration actions to benefit a wide range of ecosystem attributes and demonstrate the cost of inaction. Overall, the report concluded that substantial near-term progress to address both water quality and hydrology in the central Everglades is needed to reverse ongoing degradation before it is too late.

A series of biennial reports from the U.S. National Research Council have reviewed the progress of CERP. The fourth report in the series, released in 2012, found that little progress has been made in restoring the core of the remaining Everglades ecosystem; instead, most project construction so far has occurred along its periphery. The report noted that to reverse ongoing ecosystem declines, it will be necessary to expedite restoration projects that target the central Everglades, and to improve both the quality and quantity of the water in the ecosystem.National Research Council Report-in-Brief, Progress Toward Restoring the Everglades: The Fourth Biennial Review 2012, http://dels.nas.edu/Materials/Report-In-Brief/4296-Everglades To better understand the potential implications of the current slow pace of progress, the report assessed the current status of ten Everglades ecosystem attributes, including phosphorus loads, peat depth, and populations of snail kites, birds of prey that are endangered in South Florida. Most attributes received grades ranging from C (degraded) to D (significantly degraded), but the snail kite received a grade of F (near irreversible damage). The report also assessed the future trajectory of each ecosystem attribute under three restoration scenarios: improved water quality, improved hydrology, and improvements to both water quality and hydrology, which helped highlight the urgency of restoration actions to benefit a wide range of ecosystem attributes and demonstrate the cost of inaction. Overall, the report concluded that substantial near-term progress to address both water quality and hydrology in the central Everglades is needed to reverse ongoing degradation before it is too late.

Chapter 8E: Exotic Species in the Everglades Protection Area

South Florida Water Management District * George, Jean (1972). ''Everglades Wildguide''.

''Central and Southern Florida Project Comprehensive Review Study''

*

Everglades National Park

UNESCO Collection on Google Arts and Culture

an

Arthur R. Marshall National Wildlife Refuge (US Fish & Wildlife Service)

Everglades Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area

A History of the Everglades

*

History information about the Everglades from

the

Public television series episode on history of Florida Everglades

The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP)

The Everglades Foundation

The Everglades Coalition

South Florida Information Access (U.S. Geological Survey)

Environment Florida – Founders of The "Save The Everglades" campaign

Friends of the Everglades

South Florida Environmental Report (South Florida Water Management District and Florida DEP)

Everglades Digital Library

Water's Journey: Everglades – Comprehensive film and web documentary about the Everglades

The Everglades in the Time of Marjory Stoneman Douglas

(Photo exhibit)

– slideshow by ''

Palm Beach County

Palm Beach County is a county located in the southeastern part of Florida and lies directly north of Broward County and Miami-Dade County. The county had a population of 1,492,191 as of the 2020 census, making it the third-most populous county ...

is the Anastasia Formation, composed of shelly limestone, coquina

Coquina () is a sedimentary rock that is composed either wholly or almost entirely of the transported, abraded, and mechanically sorted fragments of the shells of mollusks, trilobites, brachiopods, or other invertebrates. The term ''coquina'' ...

, and sand representing a former mangrove or salt marsh. The Anastasia Formation is much more permeable and filled with pocks and solution holes. The Fort Thompson and Anastasia Formations, and Miami Limestone and (x), were formed during the Sangamonian

The Sangamonian Stage (or Sangamon interglacial) is the term used in North America to designate the last interglacial period. In its most common usage, it is used for the period of time between 75,000 and 125,000 BP.Willman, H.B., and J.C. Frye, 1 ...

interglacial period.Lodge, p. 10

The geologic formations that have the most influence on the Everglades are the Miami Limestone and the Fort Thompson Formation. The Miami Limestone has two facies

In geology, a facies ( , ; same pronunciation and spelling in the plural) is a body of rock with specified characteristics, which can be any observable attribute of rocks (such as their overall appearance, composition, or condition of formatio ...

. The Miami Oolite facies, which underlies the Atlantic Coastal Ridge from southern Palm Beach County to southern Miami-Dade County, is made up of ooids

Ooids are small (commonly ≤2 mm in diameter), spheroidal, "coated" (layered) sedimentary grains, usually composed of calcium carbonate, but sometimes made up of iron- or phosphate-based minerals. Ooids usually form on the sea floor, m ...

: tiny formations of egg-shaped concentric shells and calcium carbonate, formed around a single grain of sand or shell fragment. The other facies, which underlies the eastern lower Everglades (in Miami-Dade County and part of Monroe County) consists of fossilized bryozoan organisms. The unique structure was some of the first material used in housing in early 20th-century South Florida. The composition of this sedimentary formation affects the hydrology, plant life, and wildlife above it: the rock is especially porous and stores water during the dry season in the Everglades, and its chemical composition determines the vegetation prevalent in the region. The Miami Oolite facies also acts to impede flow of water from the Everglades to the ocean between Fort Lauderdale

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

and Coot Bay (near Cape Sable

Cape Sable is the southernmost point of the United States mainland and mainland Florida. It is located in southwestern Florida, in Monroe County, and is part of the Everglades National Park.

The cape is a peninsula issuing from the southeastern ...

).

The metropolitan areas of Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

, Fort Lauderdale, and West Palm Beach

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sunset, Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic languages, German ...

are located on a rise in elevation along the eastern coast of Florida, called the Eastern Coastal Ridge, that was formed as waves compressed ooids into a single formation. Along the western border of the Big Cypress Swamp is the Immokolee Ridge (or Immokolee Rise), a slight rise of compressed sand that divides the runoff between the Caloosahatchee River and The Big Cypress. This slight rise in elevation on both sides of the Everglades creates a basin, and forces water that overflows Lake Okeechobee to creep toward the southwest.

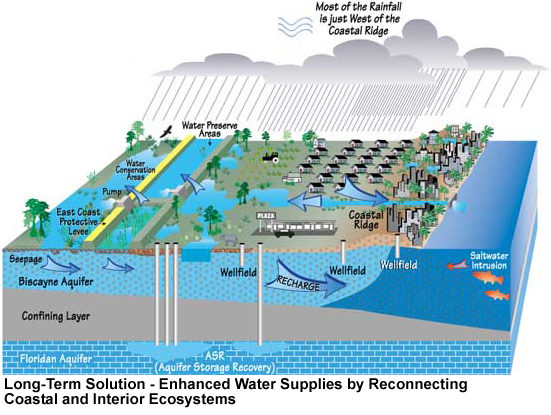

Under both the Miami Limestone formation and the Fort Thompson limestone lies the Biscayne Aquifer

The Biscayne Aquifer, named after Biscayne Bay, is a surficial aquifer. It is a shallow layer of highly permeable limestone under a portion of South Florida. The area it underlies includes Broward County, Miami-Dade County, Monroe County, and P ...

, a surface aquifer that serves as the Miami metropolitan area

The Miami metropolitan area (also known as Greater Miami, the Tri-County Area, South Florida, or the Gold Coast) is the ninth largest metropolitan statistical area in the United States and the 34th largest metropolitan area in the world with a ...

's fresh water source. Rainfall and stored water in the Everglades replenish the Biscayne Aquifer directly.

With the rise of sea levels that occurred during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

approximately 17,000 years ago, the runoff of water from Lake Okeechobee slowed and created the vast marshland that is now known as the Everglades. Slower runoff also created an accumulation of almost 18 feet (5.5 m) of peat

Peat (), also known as turf (), is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, moors, or muskegs. The peatland ecosystem covers and is the most efficien ...

in the area. The presence of such peat deposits, dated to about 5,000 years ago, is evidence that widespread flooding had occurred by then.

Hydrology

The consistent Everglades flooding is fed by the extensive

The consistent Everglades flooding is fed by the extensive Kissimmee

Kissimmee ( ) is the largest city and county seat of Osceola County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 79,226. It is a Principal City of the Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, Florida, Metropolitan Statistical Area, wh ...

, Caloosahatchee Caloosahatchee may refer to:

*Caloosahatchee River, a river on the southwest Gulf Coast of Florida in the United States

*Caloosahatchee culture, an archaeological culture on the Gulf coast of Southwest Florida that lasted from about 500 to 1750 CE

...

, Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

, Myakka, and Peace Rivers in central Florida. The Kissimmee River is a broad floodplain

A floodplain or flood plain or bottomlands is an area of land adjacent to a river which stretches from the banks of its channel to the base of the enclosing valley walls, and which experiences flooding during periods of high discharge.Goudi ...

that empties directly into Lake Okeechobee, which at with an average depth of , is a vast but shallow lake. Soil deposits in the Everglades basin indicate that peat is deposited where the land is flooded consistently throughout the year. Calcium deposits are left behind when flooding is shorter. The deposits occur in areas where water rises and falls depending on rainfall, as opposed to water being stored in the rock from one year to the next. Calcium deposits are present where more limestone is exposed.

The area from Orlando

Orlando () is a city in the U.S. state of Florida and is the county seat of Orange County. In Central Florida, it is the center of the Orlando metropolitan area, which had a population of 2,509,831, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures rele ...

to the tip of the Florida peninsula was at one point a single drainage unit. When rainfall exceeded the capacity of Lake Okeechobee and the Kissimmee River floodplain, it spilled over and flowed in a southwestern direction to empty into Florida Bay

Florida Bay is the bay located between the southern end of the Florida mainland (the Florida Everglades) and the Florida Keys in the United States. It is a large, shallow estuary that while connected to the Gulf of Mexico, has limited exchange o ...

. Prior to urban and agricultural development in Florida, the Everglades began at the southern edge of Lake Okeechobee and flowed for approximately , emptying into the Gulf of Mexico. The limestone shelf is wide and slightly angled instead of having a narrow, deep channel characteristic of most rivers. The vertical gradient from Lake Okeechobee to Florida Bay is about per mile, creating an almost wide expanse of river that travels about half a mile (0.8 km) a day. This slow movement of a broad, shallow river is known as ''sheetflow'', and gives the Everglades its nickname, River of Grass. Water leaving Lake Okeechobee may require months or years to reach its final destination, Florida Bay. The sheetflow travels so slowly that water is typically stored from one wet season to the next in the porous limestone substrate. The ebb and flow of water has shaped the land and every ecosystem in South Florida throughout the Everglades' estimated 5,000 years of existence. The motion of water defines plant communities and how animals adapt to their habitats and food sources.

Climate

The climate of

The climate of South Florida

South Florida is the southernmost region of the U.S. state of Florida. It is one of Florida's three most commonly referred to directional regions; the other two are Central Florida and North Florida. South Florida is the southernmost part of th ...

is located across the broad transition zone between subtropical

The subtropical zones or subtropics are geographical zone, geographical and Köppen climate classification, climate zones to the Northern Hemisphere, north and Southern Hemisphere, south of the tropics. Geographically part of the Geographical z ...

and tropical climate

Tropical climate is the first of the five major climate groups in the Köppen climate classification identified with the letter A. Tropical climates are defined by a monthly average temperature of 18 °C (64.4 °F) or higher in the cool ...

s (Koppen Koppen is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Dan Koppen (born 1979), American football offensive lineman

* Erwin Koppen (1929–1990), German literary scholar

* Luise Koppen (1855–1922), German author

* Wladimir Köppen (1846� ...

Aw, Am and Cfa). Like most regions with this climate type, there are two basic seasons – a "dry season" (winter) which runs from November through April, and a "wet season" (summer) which runs from May through October. About 70% of the annual rainfall in south Florida occurs in the wet season – often as brief but intense tropical downpours. The dry season sees little rainfall and dew points and humidity are often quite low. The dry season can be severe at times, as wildfires and water restrictions are often in place.

The annual range of temperatures in south Florida and the Everglades is rather small (less than 20 °F 1 °C – ranging from a monthly mean temperature of around in January to in July. High temperatures in the hot and wet season (summer) typically exceed across inland south Florida (although coastal locations are cooled by winds from the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

and the Atlantic Ocean), while high temperatures in the dry winter season average from . Frost and freeze are rare across south Florida and the Everglades; annually coastal cities like Miami and Naples report zero days with frost, although a few times each decade low temperatures may fall between across South Florida. The plant hardiness zone

A hardiness zone is a geographic area defined as having a certain average annual minimum temperature, a factor relevant to the survival of many plants. In some systems other statistics are included in the calculations. The original and most wide ...

s are 10a north with an average annual extreme minimum air temperature of 30 to 35 °F (−1 to +2 °C), and 10b south with an average annual extreme minimum air temperature of 35 to 40 °F (2 to 4 °C). Annual rainfall averages approximately , with the Eastern Coastal Ridge receiving the majority of precipitation and the area surrounding Lake Okeechobee receiving about .

Unlike any other wetland system on earth, the Everglades are sustained primarily by the atmosphere. Evapotranspiration

Evapotranspiration (ET) is the combined processes by which water moves from the earth’s surface into the atmosphere. It covers both water evaporation (movement of water to the air directly from soil, canopies, and water bodies) and transpi ...

– the sum of evaporation and plant transpiration from the Earth's land surface to atmosphere – associated with thunderstorms, is the key mechanism by which water leaves the region. During a year unaffected by drought, the rate may reach a year. When droughts take place, the rate may peak at over , and exceed the amount of rainfall. As water leaves an area through evaporation from groundwater or from plant matter, activated primarily by solar energy, it is then moved by wind patterns to other areas that border or flow into the Everglades watershed system. Evapotranspiration is responsible for approximately 70–90 percent of water entering undeveloped wetland regions in the Everglades.

Precipitation during the wet season is primarily caused by air mass thunderstorms and the easterly flow out of the subtropical high (Bermuda High). Intense daytime heating of the ground causes the warm moist tropical air to rise, creating the afternoon thundershowers typical of tropical climates. 2:00 pm is the mean time of daily thundershowers across South Florida and the Everglades. Late in the wet season (August and September), precipitation levels reach their highest levels as tropical depressions and lows add to daily rainfall. Occasionally, tropical lows can become severe tropical cyclones and cause significant damage when they make landfall across south Florida. Tropical storms average one a year, and major hurricanes about once every ten years. Between 1871 and 1981, 138 tropical cyclones struck directly over or close to the Everglades. Strong winds from these storms disperse plant seeds and replenish mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows in coastal saline water, saline or brackish water. The term is also used for tropical coastal vegetation consisting of such species. Mangroves are taxonomically diverse, as a result of convergent evoluti ...

forests, coral reefs, and other ecosystems. Dramatic fluctuations in precipitation are characteristic of the South Florida climate. Drought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

s, flood

A flood is an overflow of water ( or rarely other fluids) that submerges land that is usually dry. In the sense of "flowing water", the word may also be applied to the inflow of the tide. Floods are an area of study of the discipline hydrol ...

s, and tropical cyclones are part of the natural water system in the Everglades.

Formative and sustaining processes

The Everglades are a complex system of interdependent ecosystems.Marjory Stoneman Douglas

Marjory Stoneman Douglas (April 7, 1890 – May 14, 1998) was an American journalist, author, women's suffrage advocate, and conservationist known for her staunch defense of the Everglades against efforts to drain it and reclaim land for de ...

described the area as a "River of Grass" in 1947, though that metaphor represents only a portion of the system. The area recognized as the Everglades, prior to drainage, was a web of marshes and prairies in size. Borders between ecosystems are subtle or imperceptible. These systems shift, grow and shrink, die, or reappear within years or decades. Geologic factors, climate, and the frequency of fire help to create, maintain, or replace the ecosystems in the Everglades.

Water

Water is the dominant force in the Everglades, shaping the land, vegetation, and animal life in South Florida. Starting at the

Water is the dominant force in the Everglades, shaping the land, vegetation, and animal life in South Florida. Starting at the last glacial maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent.

Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Eur ...

, 21,000 years ago, continental ice sheets retreated and sea levels rose. This submerged portions of the Florida peninsula and caused the water table

The water table is the upper surface of the zone of saturation. The zone of saturation is where the pores and fractures of the ground are saturated with water. It can also be simply explained as the depth below which the ground is saturated.

T ...

to rise. Fresh water saturated the limestone that underlies the Everglades, eroding some of it away, and created springs and sinkhole

A sinkhole is a depression or hole in the ground caused by some form of collapse of the surface layer. The term is sometimes used to refer to doline, enclosed depressions that are locally also known as ''vrtače'' and shakeholes, and to openi ...

s. The abundance of fresh water allowed new vegetation to take root, and formed convective thunderstorms over the land through evaporation.

As rain continued to fall, the slightly acidic rainwater dissolved the limestone. As limestone wore away, the groundwater came into contact with the land surface and created a massive wetland ecosystem.McCally, pp. 9–10. Although the region appears flat, weathering

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with water, atmospheric gases, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs ''in situ'' (on site, with little or no movement), ...

of the limestone created slight valleys and plateaus in some areas. These plateaus rise and fall only a few inches, but on the subtle South Florida topography these small variations affect both the flow of water and the types of vegetation that can take hold.

Rock

ooid

Ooids are small (commonly ≤2 mm in diameter), spheroidal, "coated" (layered) sedimentary grains, usually composed of calcium carbonate, but sometimes made up of iron- or phosphate-based minerals. Ooids usually form on the sea floor, m ...

s and limestone than older types of rock that spent more time above sea level. A hydroperiod of ten months or more fosters the growth of sawgrass, whereas a shorter hydroperiod of six months or less promotes beds of periphyton

Periphyton is a complex mixture of algae, cyanobacteria, heterotrophic microbes, and detritus that is attached to submerged surfaces in most aquatic ecosystems. The related term Aufwuchs (German "surface growth" or "overgrowth") refers to the col ...

, a growth of algae and other microscopic organisms. There are only two types of soil in the Everglades, peat

Peat (), also known as turf (), is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, moors, or muskegs. The peatland ecosystem covers and is the most efficien ...

and marl

Marl is an earthy material rich in carbonate minerals, clays, and silt. When hardened into rock, this becomes marlstone. It is formed in marine or freshwater environments, often through the activities of algae.

Marl makes up the lower part o ...

. Where there are longer hydroperiods, peat builds up over hundreds or thousands of years due to many generations of decaying plant matter. Where periphyton grows, the soil develops into marl, which is more calcitic in composition.

Initial attempts at developing agriculture near Lake Okeechobee were successful, but the nutrients in the peat were rapidly removed. In a process called soil subsidence

Subsidence is a general term for downward vertical movement of the Earth's surface, which can be caused by both natural processes and human activities. Subsidence involves little or no horizontal movement, which distinguishes it from slope move ...

, oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

of peat causes loss of volume. Bacteria decompose dead sawgrass slowly underwater without oxygen. When the water was drained in the 1920s and bacteria interacted with oxygen, an aerobic reaction occurred. Microorganisms degraded the peat into carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is transpar ...

and water. Some of the peat was burned by settlers to clear the land. Some homes built in the areas of early farms had to have their foundations moved to stilts as the peat deteriorated; other areas lost approximately of soil depth.Lodge, p. 38.

Fire

Fire is an important element in the natural maintenance of the Everglades. The majority of fires are caused bylightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electric charge, electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the land, ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous ...

strikes from thunderstorms during the wet season. Their effects are largely superficial, and serve to foster specific plant growth: sawgrass will burn above water, but the roots are preserved underneath. Fire in the sawgrass marshes serves to keep out larger bushes and trees, and releases nutrients from decaying plant matter more efficiently than decomposition

Decomposition or rot is the process by which dead organic substances are broken down into simpler organic or inorganic matter such as carbon dioxide, water, simple sugars and mineral salts. The process is a part of the nutrient cycle and is e ...

.Lodge, pp. 39–41. Whereas in the wet season, dead plant matter and the tips of grasses and trees are burned, in the dry season the fire may be fed by organic peat and burn deeply, destroying root systems. Fires are confined by existing water and rainfall. It takes approximately 225 years for one foot (.30 m) of peat to develop, but in some locations the peat is less dense than it should be for the 5,000 years of the Everglades' existence.McCally, pp. 18–21. Scientists indicate fire as the cause; it is also cited as the reason for the black color of Everglades muck. Layers of charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

have been detected in the peat in portions of the Everglades that indicate the region endured severe fires for years at a time, although this trend seems to have abated since the last occurrence in 940 BC.

Ecosystems

Sawgrass marshes and sloughs

Several ecosystems are present in the Everglades, and boundaries between them are subtle or absent. The primary feature of the Everglades is the sawgrass marsh. The iconic water and sawgrass combination in the shallow river long and wide that spans from Lake Okeechobee to Florida Bay is often referred to as the "true Everglades" or just "the Glades". Prior to the first drainage attempts in 1905, the sheetflow occupied nearly a third of the lower Florida peninsula. Sawgrass thrives in the slowly moving water, but may die in unusually deep floods if oxygen is unable to reach its roots. It is particularly vulnerable immediately after a fire. The hydroperiod for the marsh is at least nine months, and can last longer. Where sawgrass grows densely, few animals or other plants live, althoughalligator

An alligator is a large reptile in the Crocodilia order in the genus ''Alligator'' of the family Alligatoridae. The two extant species are the American alligator (''A. mississippiensis'') and the Chinese alligator (''A. sinensis''). Additiona ...

s choose these locations for nesting. Where there is more room, periphyton

Periphyton is a complex mixture of algae, cyanobacteria, heterotrophic microbes, and detritus that is attached to submerged surfaces in most aquatic ecosystems. The related term Aufwuchs (German "surface growth" or "overgrowth") refers to the col ...

grows. Periphyton supports larval insects and amphibians, which in turn are consumed as food by birds, fish, and reptiles. It also absorbs calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to ...

from water, which adds to the calcitic composition of the marl.

Sloughs

A slough ( or ) is a wetland, usually a swamp or shallow lake, often a backwater to a larger body of water. Water tends to be stagnant or may flow slowly on a seasonal basis.

In North America, "slough" may refer to a side-channel from or feedi ...

, or free-flowing channels of water, develop in between sawgrass prairies. Sloughs are about deeper than sawgrass marshes, and may stay flooded for at least 11 months out of the year and sometimes multiple years in a row. Aquatic animals such as turtles, alligators, snakes, and fish thrive in sloughs; they usually feed on aquatic invertebrates. Submerged and floating plants grow here, such as bladderwort (''Utricularia

''Utricularia'', commonly and collectively called the bladderworts, is a genus of carnivorous plants consisting of approximately 233 species (precise counts differ based on classification opinions; a 2001 publication lists 215 species).Salmon, Br ...

''), waterlily (''Nymphaeaceae

Nymphaeaceae () is a family of flowering plants, commonly called water lilies. They live as rhizomatous aquatic herbs in temperate and tropical climates around the world. The family contains nine genera with about 70 known species. Water li ...

''), and spatterdock (''Nuphar lutea

''Nuphar lutea'', the yellow water-lily, brandy-bottle, or spadderdock, is an aquatic plant of the family ''Nymphaeaceae'', native to northern temperate and some subtropical regions of Europe, northwest Africa, western Asia, North America, and ...

''). Major sloughs in the Everglades system include the Shark River Slough

Shark River Slough (SRS) is a low-lying area of land that channels water through the Florida Everglades, beginning in Water Conservation Area 3, flowing through Everglades National Park, and ultimately into Florida Bay. Together with Taylor Slough ...

flowing out to Florida Bay, Lostmans River Slough bordering The Big Cypress, and Taylor Slough

Taylor Slough, located in the southeastern corner of the Florida Everglades, along with the much larger Shark River Slough farther to the west, are the principal natural drainages for the freshwater Everglades and the essential conduit for provid ...

in the eastern Everglades.

Wet prairies are slightly elevated like sawgrass marshes, but with greater plant diversity. The surface is covered in water only three to seven months of the year, and the water is, on average, shallow at only deep. When flooded, the marl can support a variety of water plants. Solution holes, or deep pits where the limestone has worn away, may remain flooded even when the prairies are dry, and they support aquatic invertebrates such as crayfish

Crayfish are freshwater crustaceans belonging to the clade Astacidea, which also contains lobsters. In some locations, they are also known as crawfish, craydids, crawdaddies, crawdads, freshwater lobsters, mountain lobsters, rock lobsters, mu ...

and snails, and larval amphibians which feed young wading birds. These regions tend to border between sloughs and sawgrass marshes.

Alligators have created a niche in wet prairies. With their claws and snouts they dig at low spots and create ponds free of vegetation that remain submerged throughout the dry season. Alligator holes are integral to the survival of aquatic invertebrates, turtles, fish, small mammals, and birds during extended drought periods. The alligators then feed upon some of the animals that come to the hole.

Alligators have created a niche in wet prairies. With their claws and snouts they dig at low spots and create ponds free of vegetation that remain submerged throughout the dry season. Alligator holes are integral to the survival of aquatic invertebrates, turtles, fish, small mammals, and birds during extended drought periods. The alligators then feed upon some of the animals that come to the hole.

Tropical hardwood hammock

hammocks

A hammock (from Spanish , borrowed from Taíno and Arawak ) is a sling made of fabric, rope, or netting, suspended between two or more points, used for swinging, sleeping, or resting. It normally consists of one or more cloth panels, or a wov ...

. They may range from one (4,000 m2) to ten acres (40,000 m2) in area, and appear in freshwater sloughs, sawgrass prairies, or pineland. Hammocks are slightly elevated on limestone plateaus risen several inches above the surrounding peat, or they may grow on land that has been unharmed by deep peat fires. Hardwood hammocks exhibit a mixture of subtropical and hardwood trees, such as Southern live oak (''Quercus virginiana

''Quercus virginiana'', also known as the southern live oak, is an evergreen oak tree endemic to the Southeastern United States. Though many other species are loosely called live oak, the southern live oak is particularly iconic of the Old South. ...

''), gumbo limbo (''Bursera simaruba

''Bursera simaruba'', commonly known as gumbo-limbo, copperwood, chaca, West Indian birch, naked Indian, and turpentine tree, is a tree species in the family Burseraceae, native to the Neotropics, from South Florida to Mexico and the Caribbean ...

''), royal palm (''Roystonea

''Roystonea'' is a genus of eleven species of monoecious palms, native to the Caribbean Islands, and the adjacent coasts of the United States (Florida), Central America and northern South America. Commonly known as the royal palms, the genus wa ...

''), and bustic (''Dipholis salicifolia

''Sideroxylon salicifolium'', commonly called white bully or willow bustic, is a species of flowering plant native to Florida, the West Indies and Central America. It has also been considered a member of the genus '' Dipholis'', with the binomia ...

'') that grow in very dense clumps. Near the base, sharp saw palmettos (''Serenoa repens

''Serenoa repens'', commonly known as saw palmetto, is the sole species currently classified in the genus ''Serenoa''. It is a small palm, growing to a maximum height around . It is endemic to the subtropical and tropical Southeastern United S ...

'') flourish, making the hammocks very difficult for people to penetrate, though small mammals, reptiles and amphibians find these islands an ideal habitat. Water in sloughs flows around the islands, creating moat

A moat is a deep, broad ditch, either dry or filled with water, that is dug and surrounds a castle, fortification, building or town, historically to provide it with a preliminary line of defence. In some places moats evolved into more extensive ...

s. Although some ecosystems are maintained and promoted by fire, hammocks may take decades or centuries to recover. The moats around the hammocks protect the trees. The trees are limited in height by weather factors such as frost, lightning, and wind; the majority of trees in hammocks grow no higher than .

Pineland

Some of the driest land in the Everglades is pineland (also called pine rockland) ecosystem, located in the highest part of the Everglades with little to no hydroperiod. Some floors, however, may have flooded solution holes or puddles for a few months at a time. The most significant feature of the pineland is the single species of South Florida slash pine (''Pinus elliottii

''Pinus elliottii'', commonly known as slash pine,Family, P. P. (1990). Pinus elliottii Engelm. slash pine. ''Silvics of North America: Conifers'', (654), 338. is a conifer tree native to the Southeastern United States. Slash pine is named after ...

''). Pineland communities require fire to maintain them, and the trees have several adaptations that simultaneously promote and resist fire.U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.South Florida Multi-Species Recovery Plan: Pine rockland

", Retrieved May 3, 2008. The sandy floor of the pine forest is covered with dry pine needles that are highly flammable. South Florida slash pines are insulated by their bark to protect them from heat. Fire eliminates competing vegetation on the forest floor, and opens pine cones to germinate seeds. A period without significant fire can turn pineland into a hardwood hammock as larger trees overtake the slash pines. The

understory

In forestry and ecology, understory (American English), or understorey (Commonwealth English), also known as underbrush or undergrowth, includes plant life growing beneath the forest canopy without penetrating it to any great extent, but abov ...

shrubs in pine rocklands are the fire-resistant saw palmetto (''Serenoa repens

''Serenoa repens'', commonly known as saw palmetto, is the sole species currently classified in the genus ''Serenoa''. It is a small palm, growing to a maximum height around . It is endemic to the subtropical and tropical Southeastern United S ...

''), cabbage palm (''Sabal palmetto

''Sabal palmetto'' (, '' SAY-bəl''), also known as cabbage palm, cabbage palmetto, sabal palm, blue palmetto, Carolina palmetto, common palmetto, Garfield's tree, and swamp cabbage, is one of 15 species of palmetto palm.

It is native to the So ...

''), and West Indian lilac (''Tetrazygia bicolor

''Tetrazygia bicolor'' is a species flowering plant in the glory bush family, Melastomataceae, that is native to southern Florida in the United States and the Caribbean. Common names include Florida clover ash, Florida tetrazygia and West India ...

''). The most diverse group of plants in the pine community are the herbs, of which there are two dozen species. These plants contain tuber

Tubers are a type of enlarged structure used as storage organs for nutrients in some plants. They are used for the plant's perennation (survival of the winter or dry months), to provide energy and nutrients for regrowth during the next growing ...

s and other mechanisms that allow them to sprout quickly after being charred.

Prior to urban development of the South Florida region, pine rocklands covered approximately in Miami-Dade County

Miami-Dade County is a county located in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Florida. The county had a population of 2,701,767 as of the 2020 census, making it the most populous county in Florida and the seventh-most populous county in ...

. Within Everglades National Park, of pine forests are protected, but outside the park, of pine communities remained as of 1990, averaging in area. The misunderstanding of the role of fire also played a part in the disappearance of pine forests in the area, as natural fires were put out and pine rocklands transitioned into hardwood hammocks. Prescribed fire

A controlled or prescribed burn, also known as hazard reduction burning, backfire, swailing, or a burn-off, is a fire set intentionally for purposes of forest management, farming, prairie restoration or greenhouse gas abatement. A control ...

s occur in Everglades National Park in pine rocklands every three to seven years.

Cypress

Cypress swamps can be found throughout the Everglades, but the largest covers most of

Cypress swamps can be found throughout the Everglades, but the largest covers most of Collier County

Collier County is a county in the U.S. state of Florida. As of the 2020 census, the population was 375,752; an increase of 16.9% since the 2010 United States Census. Its county seat is East Naples, where the county offices were moved from E ...

. The Big Cypress Swamp is located to the west of the sawgrass prairies and sloughs, and it is commonly called "The Big Cypress".George, p. 26. The name refers to its area rather than the height or diameter of the trees; at its most conservative estimate, the swamp measures , but the hydrologic boundary of The Big Cypress can be calculated at over . Most of The Big Cypress sits atop a bedrock covered by a thinner layer of limestone. The limestone underneath the Big Cypress contains quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical form ...

, which creates sandy soil that hosts a variety of vegetation different from what is found in other areas of the Everglades. The basin for The Big Cypress receives on average of water in the wet season.

Although The Big Cypress is the largest growth of cypress swamps in South Florida, cypress swamps can be found near the Atlantic Coastal Ridge and between Lake Okeechobee and the Eastern flatwoods, as well as in sawgrass marshes. Cypresses are deciduous conifer

Conifers are a group of conifer cone, cone-bearing Spermatophyte, seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the phylum, division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single ...

s that are uniquely adapted to thrive in flooded conditions, with buttressed trunks and root projections that protrude out of the water, called "knees". Bald cypress

''Taxodium distichum'' (bald cypress, swamp cypress; french: cyprès chauve;

''cipre'' in Louisiana) is a deciduous conifer in the family Cupressaceae. It is native to the southeastern United States. Hardy and tough, this tree adapts to a wide r ...

trees grow in formations with the tallest and thickest trunks in the center, rooted in the deepest peat. As the peat thins out, cypresses grow smaller and thinner, giving the small forest the appearance of a dome from the outside. They also grow in strands, slightly elevated on a ridge of limestone bordered on either side by sloughs. Other hardwood trees can be found in cypress domes, such as red maple

''Acer rubrum'', the red maple, also known as swamp maple, water maple, or soft maple, is one of the most common and widespread deciduous trees of eastern and central North America. The U.S. Forest Service recognizes it as the most abundant nativ ...

, swamp bay, and pop ash. If cypresses are removed, the hardwoods take over, and the ecosystem is recategorized as a mixed swamp forest.

Mangrove and Coastal prairie

brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estuari ...

water where fresh and salt water meet. The estuarine ecosystem of the Ten Thousand Islands

The Ten Thousand Islands are a chain of islands and mangrove islets off the coast of southwest Florida, between Cape Romano (at the south end of Marco Island) and the mouth of the Lostmans River. Some of the islands are high spots on a submerg ...

, which is comprised almost completely of mangrove forests, covers almost . In the wet season fresh water pours out into Florida Bay, and sawgrass begins to grow closer to the coastline. In the dry season, and particularly in extended periods of drought, the salt water creeps inland into the coastal prairie, an ecosystem that buffers the freshwater marshes by absorbing sea water. Mangrove trees begin to grow in fresh water ecosystems when the salt water goes far enough inland.

There are three species of trees that are considered mangroves: red (''Rhizophora mangle

''Rhizophora mangle'', the red mangrove, is distributed in Estuary, estuarine ecosystems throughout the tropics. Its Vivipary, viviparous "seeds", in actuality called propagules, become fully mature plants before dropping off the parent tree. Th ...

''), black (''Avicennia germinans

''Avicennia germinans'', the black mangrove, is a shrub or small tree growing up to 12 meters (39 feet) in the acanthus family, Acanthaceae. It grows in tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas, on both the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts, ...

''), and white (''Laguncularia racemosa

''Laguncularia racemosa'', the white mangrove, is a species of flowering plant in the leadwood tree family, Combretaceae. It is native to the coasts of western Africa from Senegal to Cameroon, the Atlantic Coast of the Americas from Bermuda and ...

''), although all are from different families. All grow in oxygen-poor soil, can survive drastic water level changes, and are tolerant of salt, brackish, and fresh water. All three mangrove species are integral to coastline protection during severe storms. Red mangroves have the farthest-reaching roots, trapping sediments that help build coastlines after and between storms. All three types of trees absorb the energy of waves and storm surge

A storm surge, storm flood, tidal surge, or storm tide is a coastal flood or tsunami-like phenomenon of rising water commonly associated with low-pressure weather systems, such as cyclones. It is measured as the rise in water level above the n ...

s. Everglades mangroves also serve as nurseries for crustaceans

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group ...

and fish, and rookeries for birds. The region supports Tortugas pink shrimp (''Farfantepenaeus duorarum

''Farfantepenaeus duorarum'' is a species of marine penaeid shrimp found around Bermuda, along the east coast of the United States and in the Gulf of Mexico. They are a significant commercial species in the United States and Cuba.

Distribution

...

'') and stone crab ('' Menippe mercenaria'') industries; between 80 and 90 percent of commercially harvested crustacean species in Florida's salt waters are born or spend time near the Everglades.Ripple, p. 80.

Florida Bay

Florida Bay