Giuseppe Ungaretti on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

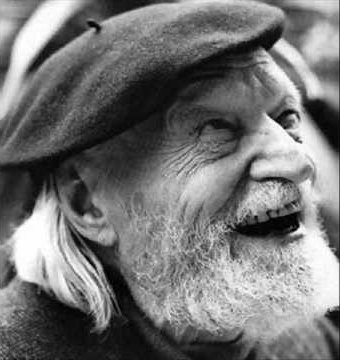

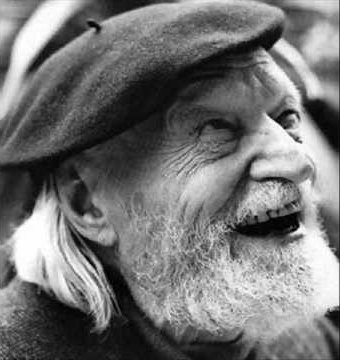

Giuseppe Ungaretti (; 8 February 1888 – 2 June 1970) was an Italian

"Ungaretti: 'Serve un Duce alla guida della cultura' "

in ''

In 1964, he gave a series of lectures at

In 1964, he gave a series of lectures at

"Alberto Moravia and Italian Fascism: Censorship, Racism and ''Le ambizioni sbagliate''"

in ''Modern Italy'', Vol. 11, No. 2, June 2006 (hosted by the

Finding aid to Luciano Rebay collection of Giuseppe Ungaretti at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

modernist

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

poet, journalist, essayist, critic, academic, and recipient of the inaugural 1970 Neustadt International Prize for Literature

The Neustadt International Prize for Literature is a biennial literary award, award for literature sponsored by the University of Oklahoma and its international literary publication, ''World Literature Today''. It is considered one of the more p ...

. A leading representative of the experimental

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs when ...

trend known as '' Ermetismo'' ("Hermeticism

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth). These teachings are containe ...

"), he was one of the most prominent contributors to 20th century Italian literature

Italian literature is written in the Italian language, particularly within Italy. It may also refer to literature written by Italians or in other languages spoken in Italy, often languages that are closely related to modern Italian, including ...

. Influenced by symbolism, he was briefly aligned with futurism

Futurism ( it, Futurismo, link=no) was an Art movement, artistic and social movement that originated in Italy, and to a lesser extent in other countries, in the early 20th century. It emphasized dynamism, speed, technology, youth, violence, an ...

. Like many futurists, he took an irredentist

Irredentism is usually understood as a desire that one state annexes a territory of a neighboring state. This desire is motivated by ethnic reasons (because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to the population of the parent sta ...

position during World War I. Ungaretti debuted as a poet while fighting in the trenches, publishing one of his best-known pieces, ''L'allegria

''L'allegria'' (Joy/Happiness or better, Merriness) is a collection of poems published by Giuseppe Ungaretti in 1931. It was an expanded version of a 1919 collection ''Allegria di naufragi'' (Merriness of Shipwrecks). Many of the poems were writ ...

'' ("The Joy").

During the interwar period, Ungaretti worked as a journalist with Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

(whom he met during his socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

accession), as well as a foreign-based correspondent for '' Il Popolo d'Italia'' and '' Gazzetta del Popolo''. While briefly associated with the Dadaists, he developed ''Hermeticism

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth). These teachings are containe ...

'' as a personal take on poetry. After spending several years in Brazil, he returned home during World War II, and was assigned a teaching post at the University of Rome, where he spent the final decades of his life and career.

Biography

Early life

Ungaretti was born inAlexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

into a family from the Tuscan city of Lucca

Lucca ( , ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, Central Italy, on the Serchio River, in a fertile plain near the Ligurian Sea. The city has a population of about 89,000, while its province has a population of 383,957.

Lucca is known as ...

.Picchione & Smith, p. 204 Ungaretti's father worked on digging the Suez Canal, where he suffered a fatal accident in 1890. His widowed mother, who ran a bakery on the edge of the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

, educated her child on the basis of Roman Catholic tenets.

Giuseppe Ungaretti's formal education began in French, at Alexandria's Swiss School. It was there that he became acquainted with Parnassianism

Parnassianism (or Parnassism) was a French literary style that began during the positivist period of the 19th century, occurring after romanticism and prior to symbolism. The style was influenced by the author Théophile Gautier as well as by t ...

and Symbolist poetry

Symbolism was a late 19th-century art movement of French and Belgian origin in poetry and other arts seeking to represent absolute truths symbolically through language and metaphorical images, mainly as a reaction against naturalism and reali ...

, in particular with Gabriele d'Annunzio, Charles Baudelaire

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (, ; ; 9 April 1821 – 31 August 1867) was a French poet who also produced notable work as an essayist and art critic. His poems exhibit mastery in the handling of rhyme and rhythm, contain an exoticism inherited ...

, Jules Laforgue, Stéphane Mallarmé

Stéphane Mallarmé ( , ; 18 March 1842 – 9 September 1898), pen name of Étienne Mallarmé, was a French poet and critic. He was a major French symbolist poet, and his work anticipated and inspired several revolutionary artistic schools of t ...

and Arthur Rimbaud

Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud (, ; 20 October 1854 – 10 November 1891) was a French poet known for his transgressive and surreal themes and for his influence on modern literature and arts, prefiguring surrealism. Born in Charleville, he sta ...

. He also became familiar with works of the Classicists Giacomo Leopardi

Count Giacomo Taldegardo Francesco di Sales Saverio Pietro Leopardi (, ; 29 June 1798 – 14 June 1837) was an Italian philosopher, poet, essayist, and philologist. He is considered the greatest Italian poet of the nineteenth century and one o ...

and Giosuè Carducci

Giosuè Alessandro Giuseppe Carducci (; 27 July 1835 – 16 February 1907) was an Italian poet, writer, literary critic and teacher. He was very noticeably influential, and was regarded as the official national poet of modern Italy. In 1906, ...

, as well as with the writings of maverick author Giovanni Pascoli. This period marked his debut as a journalist and literary critic, with pieces published ''Risorgete'', a journal edited by anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

writer Enrico Pea

Enrico is both an Italian masculine given name and a surname, Enrico means homeowner, or king, derived from ''Heinrich'' of Germanic origin. It is also a given name in Ladino. Equivalents in other languages are Henry (English), Henri (French), Enri ...

. At the time, he was in correspondence with Giuseppe Prezzolini Giuseppe Prezzolini (27 January 1882 – 16 July 1982) was an Italian literary critic, journalist, editor and writer. He later became an American citizen.

Biography

Prezzolini was born in Perugia in January 1882, to Tuscan parents from Siena, Lui ...

, editor of the influential magazine '' La Voce''. A regular visitor of Pea's ''Baracca Rossa'' ("Red House"), Ungaretti was himself a sympathizer of anarchist-socialist circles. He abandoned Christianity and became an atheist. It was not until 1928 that he returned to the Catholic faith.

In 1912, the 24-year-old Giuseppe Ungaretti moved to Paris, France. On his way there, he stopped in Rome, Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

and Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard language, Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the List of cities in Italy, second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 ...

, meeting face to face with Prezzolini. Ungaretti attended lectures at the Collège de France

The Collège de France (), formerly known as the ''Collège Royal'' or as the ''Collège impérial'' founded in 1530 by François I, is a higher education and research establishment ('' grand établissement'') in France. It is located in Paris ...

and the University of Paris

The University of Paris (french: link=no, Université de Paris), Metonymy, metonymically known as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, active from 1150 to 1970, with the exception between 1793 and 1806 under the French Revo ...

, and had among his teachers philosopher Henri Bergson

Henri-Louis Bergson (; 18 October 1859 – 4 January 1941) was a French philosopherHenri Bergson. 2014. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 13 August 2014, from https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/61856/Henri-Bergson

, whom he reportedly admired. The young writer also met and befriended French literary figure Guillaume Apollinaire

Guillaume Apollinaire) of the Wąż coat of arms. (; 26 August 1880 – 9 November 1918) was a French French poetry, poet, playwright, short story writer, novelist, and art critic of Polish-Belarusian, Polish descent.

Apollinaire is considered ...

, a promoter of Cubism

Cubism is an early-20th-century avant-garde art movement that revolutionized European painting and sculpture, and inspired related movements in music, literature and architecture. In Cubist artwork, objects are analyzed, broken up and reassemble ...

and a forerunner of Surrealism

Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to ...

. Apollinaire's work came to be a noted influence on his own. He was also in contact with the Italian expatriates, including leading representatives of Futurism

Futurism ( it, Futurismo, link=no) was an Art movement, artistic and social movement that originated in Italy, and to a lesser extent in other countries, in the early 20th century. It emphasized dynamism, speed, technology, youth, violence, an ...

such as Carlo Carrà

Carlo Carrà (; February 11, 1881 – April 13, 1966) was an Italians, Italian Painting, painter and a leading figure of the Futurism (art), Futurist movement that flourished in Italy during the beginning of the 20th century. In addition to h ...

, Umberto Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni (, ; 19 October 1882 – 17 August 1916) was an influential Italian painter and sculptor. He helped shape the revolutionary aesthetic of the Futurism movement as one of its principal figures. Despite his short life, his approach ...

, Aldo Palazzeschi

Aldo Palazzeschi (; 2 February 1885 – 17 August 1974) was the pen name of Aldo Giurlani, an Italian novelist, poet, journalist and essayist.

Biography

He was born in Florence to a well-off, bourgeois family. Following his father's direction, ...

, Giovanni Papini

Giovanni Papini (9 January 18818 July 1956) was an Italian journalist, essayist, novelist, short story writer, poet, literary critic, and philosopher. A controversial literary figure of the early and mid-twentieth century, he was the earliest an ...

and Ardengo Soffici

Ardengo Soffici (7 April 1879 – 19 August 1964) was an Italian writer, painter, poet, sculptor and intellectual.

Early life

Soffici was born in Rignano sull'Arno, near Florence. In 1893 his family moved to the latter city, where he studi ...

, as well as with the independent visual artist Amedeo Modigliani

Amedeo Clemente Modigliani (, ; 12 July 1884 – 24 January 1920) was an Italian painter and sculptor who worked mainly in France. He is known for portraits and nudes in a modern style characterized by a surreal elongation of faces, necks, a ...

.

World War I and debut

Upon the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Ungaretti, like his Futurist friends, supported anirredentist

Irredentism is usually understood as a desire that one state annexes a territory of a neighboring state. This desire is motivated by ethnic reasons (because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to the population of the parent sta ...

position, and called for his country's intervention on the side of the Entente Powers

The Triple Entente (from French ''entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well as ...

.Picchione & Smith, p. 205 Enrolled in the infantry a year later, he saw action on the Northern Italian theater, serving in the trenches.Payne; Picchione & Smith, p. 205 In contrast to his early enthusiasm, he became appalled by the realities of war. The conflict also made Ungaretti discover his talent as a poet, and, in 1917, he published the volume of free verse

Free verse is an open form of poetry, which in its modern form arose through the French '' vers libre'' form. It does not use consistent meter patterns, rhyme, or any musical pattern. It thus tends to follow the rhythm of natural speech.

Defini ...

''Il porto sepolto'' ("The Buried Port"), largely written on the Kras

''KRAS'' ( Kirsten rat sarcoma virus) is a gene that provides instructions for making a protein called K-Ras, a part of the RAS/MAPK pathway. The protein relays signals from outside the cell to the cell's nucleus. These signals instruct the cel ...

front. Although depicting the hardships of war life, his celebrated ''L'Allegria'' was not unenthusiastic about its purpose (even if in the poem "Fratelli", and in others, he describes the absurdity of the war and the brotherhood between all the men); this made Ungaretti's stance contrast with that of Lost Generation

The Lost Generation was the social generational cohort in the Western world that was in early adulthood during World War I. "Lost" in this context refers to the "disoriented, wandering, directionless" spirit of many of the war's survivors in the ...

writers, who questioned their countries' intents, and similar to that of Italian intellectuals such as Soffici, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

Filippo Tommaso Emilio Marinetti (; 22 December 1876 – 2 December 1944) was an Italian poet, editor, art theorist, and founder of the Futurist movement. He was associated with the utopian and Symbolist artistic and literary community Abbaye d ...

, Piero Jahier and Curzio Malaparte

Curzio Malaparte (; 9 June 1898 – 19 July 1957), born Kurt Erich Suckert, was an Italian writer, filmmaker, war correspondent and diplomat. Malaparte is best known outside Italy due to his works ''Kaputt'' (1944) and ''La pelle'' (1949). The f ...

.

By the time the 1918 armistice was signed, Ungaretti was again in Paris, working as a correspondent for Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

's paper '' Il Popolo d'Italia''. He published a volume of French-language poetry, titled ''La guerre'' ("The War", 1919).Payne In 1920, Giuseppe Ungaretti married the Frenchwoman Jeanne Dupoix, with whom he had a daughter, Ninon (born 1925), and a son, Antonietto (born 1930).

During that period in Paris, Ungaretti came to affiliate with the anti-establishment

An anti-establishment view or belief is one which stands in opposition to the conventional social, political, and economic principles of a society. The term was first used in the modern sense in 1958, by the British magazine '' New Statesman' ...

and anti-art current known as Dada

Dada () or Dadaism was an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20th century, with early centres in Zürich, Switzerland, at the Cabaret Voltaire (Zurich), Cabaret Voltaire (in 1916). New York Dada began c. 1915, and after 192 ...

ism. He was present in the Paris-based Dadaist circle led by Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

n poet Tristan Tzara

Tristan Tzara (; ; born Samuel or Samy Rosenstock, also known as S. Samyro; – 25 December 1963) was a Romanian and French avant-garde poet, essayist and performance artist. Also active as a journalist, playwright, literary and art critic, comp ...

, being, alongside Alberto Savinio

Alberto Savinio , born as Andrea Francesco Alberto de Chirico (25 August 1891 – 5 May 1952) was a Greek-Italian writer, painter, musician, journalist, essayist, playwright, set designer and composer. He was the younger brother of ' metaphysica ...

, Julius Evola

Giulio Cesare Andrea "Julius" Evola (; 19 May 1898 – 11 June 1974) was an Italian philosopher, poet, painter, esotericist, and radical-right ideologue. Evola regarded his values as aristocratic, masculine, traditionalist, heroic, and defiantly ...

, Gino Cantarelli, Aldo Fiozzi and Enrico Prampolini, one of the figures who established a transition from Italian Futurism to Dada. In May 1921, he was present at the Dadaist mock trial of reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the '' status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abs ...

author Maurice Barrès

Auguste-Maurice Barrès (; 19 August 1862 – 4 December 1923) was a French novelist, journalist and politician. Spending some time in Italy, he became a figure in French literature with the release of his work '' The Cult of the Self'' in 188 ...

, during which the Dadaist movement began to separate itself into two competing parts, headed respectively by Tzara and André Breton

André Robert Breton (; 19 February 1896 – 28 September 1966) was a French writer and poet, the co-founder, leader, and principal theorist of surrealism. His writings include the first ''Surrealist Manifesto'' (''Manifeste du surréalisme'') o ...

. He was also affiliated with the literary circle formed around the journal ''La Ronda''.

''Hermeticism'' and fascism

The year after his marriage, Ungaretti returned to Italy, settling in Rome as aForeign Ministry In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The enti ...

employee. By then, Mussolini had organized the March on Rome

The March on Rome ( it, Marcia su Roma) was an organized mass demonstration and a coup d'état in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 1922, F ...

, which confirmed his seizure of power. Ungaretti joined in the National Fascist Party

The National Fascist Party ( it, Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF) was a political party in Italy, created by Benito Mussolini as the political expression of Italian Fascism and as a reorganization of the previous Italian Fasces of Combat. The p ...

, signing the pro-fascist ''Manifesto of the Italian Writers'' in 1925. In his essays of 1926–1929, republished in 1996, he repeatedly called on the ''Duce

( , ) is an Italian title, derived from the Latin word 'leader', and a cognate of ''duke''. National Fascist Party leader Benito Mussolini was identified by Fascists as ('The Leader') of the movement since the birth of the in 1919. In 19 ...

'' to direct cultural development in Italy and reorganize the Italian Academy

The Royal Academy of Italy ( it, Reale Accademia d'Italia, italic=no) was a short-lived Italian academy of the Fascist period. It was created on 7 January 1926 by royal decree,See reference . but was not inaugurated until 28 October 1929. It was e ...

on fascist lines. Giorgio De Rienzo"Ungaretti: 'Serve un Duce alla guida della cultura' "

in ''

Corriere della Sera

The ''Corriere della Sera'' (; en, "Evening Courier") is an Italian daily newspaper published in Milan with an average daily circulation of 410,242 copies in December 2015.

First published on 5 March 1876, ''Corriere della Sera'' is one of I ...

'', 12 December 1996; but in this article Ossola explains also that Ungaretti is not a "constituent" intellectual of Fascism; and that he was not admitted, for many political reasons, in the Fascist Academy He argued: "The first task of the Academy will be to reestablish a certain connection between men of letters, between writers, teachers, publicists. This people hungers for poetry. If it had not been for the miracle of Blackshirts

The Voluntary Militia for National Security ( it, Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale, MVSN), commonly called the Blackshirts ( it, Camicie Nere, CCNN, singular: ) or (singular: ), was originally the paramilitary wing of the Natio ...

, we would never have leaped this far." In his private letters to a French critic, Ungaretti also claimed that fascist rule did not imply censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

. Mussolini, who did not give a favorable answer to Ungaretti's appeal, prefaced the 1923 edition of ''Il porto sepolto'', thus politicizing its message.

In 1925, Ungaretti experienced a religious crisis, which, three years later, made him return to the Roman Catholic Church. Meanwhile, he contributed to a number of journals and published a series of poetry volumes, before becoming a foreign correspondent for '' Gazzetta del Popolo'' in 1931, and traveling not only to Egypt, Corsica and the Netherlands, but also to various regions of Italy.

It was during this period that Ungaretti introduced '' Ermetismo'', baptized with the Italian-language

Italian (''italiano'' or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European language family that evolved from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire. Together with Sardinian, Italian is the least divergent language from Latin. Spoken by about 85 m ...

word for "''Hermeticism

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth). These teachings are containe ...

''"."Hermeticism", entry in ''Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature'', Merriam-Webster

Merriam-Webster, Inc. is an American company that publishes reference books and is especially known for its dictionaries. It is the oldest dictionary publisher in the United States.

In 1831, George and Charles Merriam founded the company as ...

, Springfield, 1995, p. 540. The new trend, inspired by both Symbolism and Futurism, had its origins in both ''Il porto sepolto'', where Ungaretti had eliminated structure, syntax and punctuation, and the earlier contributions of Arturo Onofri. The style was indebted to the influence of Symbolists from Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wide ...

to Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Mallarmé and Paul Valéry

Ambroise Paul Toussaint Jules Valéry (; 30 October 1871 – 20 July 1945) was a French poet, essayist, and philosopher. In addition to his poetry and fiction (drama and dialogues), his interests included aphorisms on art, history, letters, mu ...

. Alongside Ungaretti, its main representatives were Eugenio Montale

Eugenio Montale (; 12 October 1896 – 12 September 1981) was an Italian poet, prose writer, editor and translator, and recipient of the 1975 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Life and works

Early years

Montale was born in Genoa. His family were ch ...

and Salvatore Quasimodo

Salvatore Quasimodo (; August 20, 1901 – June 14, 1968) was an Italian poet and translator. In 1959, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature "for his lyrical poetry, which with classical fire expresses the tragic experience of life in our own time ...

.

Despite the critical acclaim he enjoyed, the poet confronted himself with financial difficulties. In 1936, he moved to the Brazilian city of São Paulo

São Paulo (, ; Portuguese for 'Saint Paul') is the most populous city in Brazil, and is the capital of the state of São Paulo, the most populous and wealthiest Brazilian state, located in the country's Southeast Region. Listed by the Ga ...

, and became a Professor of Italian at São Paulo University

SAO or Sao may refer to:

Places

* Sao civilisation, in Middle Africa from 6th century BC to 16th century AD

* Sao, a town in Boussé Department, Burkina Faso

* Saco Transportation Center (station code SAO), a train station in Saco, Maine, U.S. ...

. It was there that, in 1939, his son Antonietto died as a result of a badly performed appendectomy

An appendectomy, also termed appendicectomy, is a surgical operation in which the vermiform appendix (a portion of the intestine) is removed. Appendectomy is normally performed as an urgent or emergency procedure to treat complicated acute append ...

.

World War II and after

In 1942, three years after the start of World War II, Ungaretti returned toAxis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

-allied Italy, where he was received with honors by the officials. The same year, he was made a Professor of Modern Literature at the University of Rome. He continued to write poetry, and published a series of essays. By then, ''Hermeticism

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth). These teachings are containe ...

'' had come to an end, and Ungaretti, like Montale and Quasimodo, had adopted a more formal style in his poetry. At Rome, Ungaretti mentored the poet Elio Filippo Accrocca, whose work was greatly influenced by Ungaretti's.

At the close of the war, following Mussolini's downfall, Ungaretti was expelled from the faculty owing to his fascist connections, but reinstated when his colleagues voted in favor of his return. Affected by his wife's 1958 death, Giuseppe Ungaretti sought comfort in traveling throughout Italy and abroad. He visited Japan, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, Israel and the United States.

In 1964, he gave a series of lectures at

In 1964, he gave a series of lectures at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manha ...

in New York City, and, in 1970, was invited by the University of Oklahoma

, mottoeng = "For the benefit of the Citizen and the State"

, type = Public research university

, established =

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $2.7billion (2021)

, pr ...

to receive its Books Abroad Prize. During this last trip, Ungaretti fell ill with bronchopneumonia

Bronchopneumonia is a subtype of pneumonia. It is the acute inflammation of the bronchi, accompanied by inflamed patches in the nearby lobules of the lungs. citing: Webster's New World College Dictionary, Fifth Edition, Copyright 2014

It is ofte ...

, and, although he received treatment in New York City, died while under medical supervision in Milan. He was buried in Campo Verano

The Campo Verano (Italian: ''Cimitero del Verano'') is a cemetery in Rome, Italy, founded in the early 19th century. The monumental cemetery is currently divided into sections: the Jewish cemetery, the Catholic cemetery, and the monument to the ...

(Rome).

Poetry

''L'Allegria'', previously called ''L'Allegria di Naufragi'', is a decisive moment of the recent history of Italian literature: Ungaretti revises with novel ideas the poetic style of the '' poètes maudits'' (especially the broken verses without punctation marks ofGuillaume Apollinaire

Guillaume Apollinaire) of the Wąż coat of arms. (; 26 August 1880 – 9 November 1918) was a French French poetry, poet, playwright, short story writer, novelist, and art critic of Polish-Belarusian, Polish descent.

Apollinaire is considered ...

's ''Calligrammes'' and the equality between verse and a single word), connecting it with his experience of death and pain as a soldier at war. The hope of brotherhood between all the people is expressed strongly, together with the desire of searching for a renovated "harmony" with the universe, impressive in the famous verses of ''Mattina'':

A famous poem regarding the First World War is ''Soldati'' (soldiers), which emblematically and emotionally describes their feelings of uncertainty and fear:

In the successive works he studied the importance of the poetic word (marked by ''Hermeticism

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth). These teachings are containe ...

'' and symbolism

Symbolism or symbolist may refer to:

Arts

* Symbolism (arts), a 19th-century movement rejecting Realism

** Symbolist movement in Romania, symbolist literature and visual arts in Romania during the late 19th and early 20th centuries

** Russian sym ...

), as the only way to save the humanity from the universal horror, and was searching for a new way to recuperate the roots of the Italian classical poetry.Elio Gioanola, ''ibidem'', p. 188 His last verses are on the poem ''l'Impietrito e il Velluto'', about the memory of the ''bright universe eyed'' Dunja, an old woman that was house guest of his mother in the time of his childhood. Here is the end:

Legacy

Although Ungaretti parted company with '' Ermetismo ("Hermeticism

Hermeticism, or Hermetism, is a philosophical system that is primarily based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (a legendary Hellenistic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth). These teachings are containe ...

")'', his early experiments were continued for a while by poets such as Alfonso Gatto

Alfonso Gatto (17 July 1909 – 8 March 1976) was an Italian writer. Along with Giuseppe Ungaretti and Eugenio Montale, he is one of the foremost Italian poets of the 20th century and a major exponent of hermetic poetry.

Biography

Gatto stud ...

, Mario Luzi

Mario Luzi (20 October 1914 – 28 February 2005) was an Italian poet.

Biography

Born in Castello, near Sesto Fiorentino, Luzi's parents, Ciro Luzi and Margherita Papini, hailed from Samprugnano (later Semproniano). He spent his youth in Caste ...

and Leonardo Sinisgalli. His collected works were published as ''Vita di un uomo'' ("The Life of a Man") at the time of his death.

Two of Ungaretti's poems ("Soldiers – War – Another War" and "Vanity") were made into song by American composer Harry Partch

Harry Partch (June 24, 1901 – September 3, 1974) was an American composer, music theorist, and creator of unique musical instruments. He composed using scales of unequal intervals in just intonation, and was one of the first 20th-century co ...

(''Eleven Intrusions'', 1949–50); and eleven poems were set by the French-Romanian composer Horațiu Rădulescu in his cycle ''End of Kronos'' (1999). Fragments of his poetry are set by composer Michael Mantler in Cerco un Paese Innocente, a work recorded in 1994.

Austrian-Hungarian composer Iván Eröd

Ivan () is a Slavic male given name, connected with the variant of the Greek name (English: John) from Hebrew meaning 'God is gracious'. It is associated worldwide with Slavic countries. The earliest person known to bear the name was Bulga ...

used his poems in four of his works: "Tutto ho perduto" Op. 12 (1965), "Canti di Ungaretti" Op. 55 (1988), "Vox lucis" Op. 56 (1988–89) and in his last work "Canti di un Ottantenne" Op. 95 (2019), completed only several days before his death in June 2019.

Published volumes

*''Il porto sepolto'' ("The Buried Port", 1916 and 1923) *''La guerra'' ("The War", 1919 and 1947) *''Allegria di naufragi'' ("The Joy of Shipwrecks", 1919) *''L'allegria'' ("The Joy", 1931) *''Sentimento del tempo'' ("The Feeling of Time", 1933) *''Traduzioni'' ("Translations", 1936) *''Poesie disperse'' ("Scattered Poems", 1945) *''Il dolore'' ("The Pain", 1947) *''La terra promessa'' ("The Promised Land", 1950) *''Un grido e paesaggi'' ("A Shout and Landscapes", 1952) *''Il taccuino del vecchio'' ("The Old Man's Notebook", 1960) *''Vita di un uomo'' ("The Life of a Man", 1969)Notes

References

*Alessandro Baruffi, in ''Giuseppe Ungaretti, the Master of Hermeticism, Translated in English'', LiteraryJoint Press, Philadelphia, PA, 2018. *Roberta L. Payne, "Ungaretti, Giuseppe", in ''A Selection of Modern Italian Poetry in Translation'', McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal & Kingston, p. 198. *John Picchione, Lawrence R. Smith, ''Twentieth-century Italian Poetry. An Anthology'',University of Toronto Press

The University of Toronto Press is a Canadian university press founded in 1901. Although it was founded in 1901, the press did not actually publish any books until 1911.

The press originally printed only examination books and the university cale ...

, Toronto, 1993.

* Hans Richter, ''Dada. Art and Anti-art'', Thames & Hudson

Thames & Hudson (sometimes T&H for brevity) is a publisher of illustrated books in all visually creative categories: art, architecture, design, photography, fashion, film, and the performing arts. It also publishes books on archaeology, history, ...

, London & New York, 2004.

*George Talbot"Alberto Moravia and Italian Fascism: Censorship, Racism and ''Le ambizioni sbagliate''"

in ''Modern Italy'', Vol. 11, No. 2, June 2006 (hosted by the

University of Hull

, mottoeng = Bearing the Torch f learning, established = 1927 – University College Hull1954 – university status

, type = Public

, endowment = £18.8 million (2016)

, budget = £190 millio ...

)Finding aid to Luciano Rebay collection of Giuseppe Ungaretti at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ungaretti, Giuseppe 1888 births 1970 deaths Burials at Campo Verano Converts to Roman Catholicism from atheism or agnosticism Deaths from bronchopneumonia Deaths from pneumonia in Lombardy Italian essayists Italian expatriates in Brazil Italian expatriates in Egypt Italian expatriates in France Italian fascists Italian male journalists Italian military personnel of World War I Italian World War I poets Italian writers in French People from Alexandria Sapienza University of Rome faculty Symbolist poets University of São Paulo faculty Italian male poets 20th-century Italian male writers 20th-century Italian poets Male essayists 20th-century essayists 20th-century Italian journalists