Geysers Of Wyoming on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A geyser (, ) is a

A geyser (, ) is a

Geysers are nonpermanent geological features. Geysers are generally associated with volcanic areas.How geysers form

Geysers are nonpermanent geological features. Geysers are generally associated with volcanic areas.How geysers form

Gregory L. As the water boils, the resulting pressure forces a superheated column of steam and water to the surface through the geyser's internal plumbing. The formation of geysers specifically requires the combination of three geologic conditions that are usually found in volcanic terrain: intense heat, water, and a plumbing system. The heat needed for geyser formation comes from

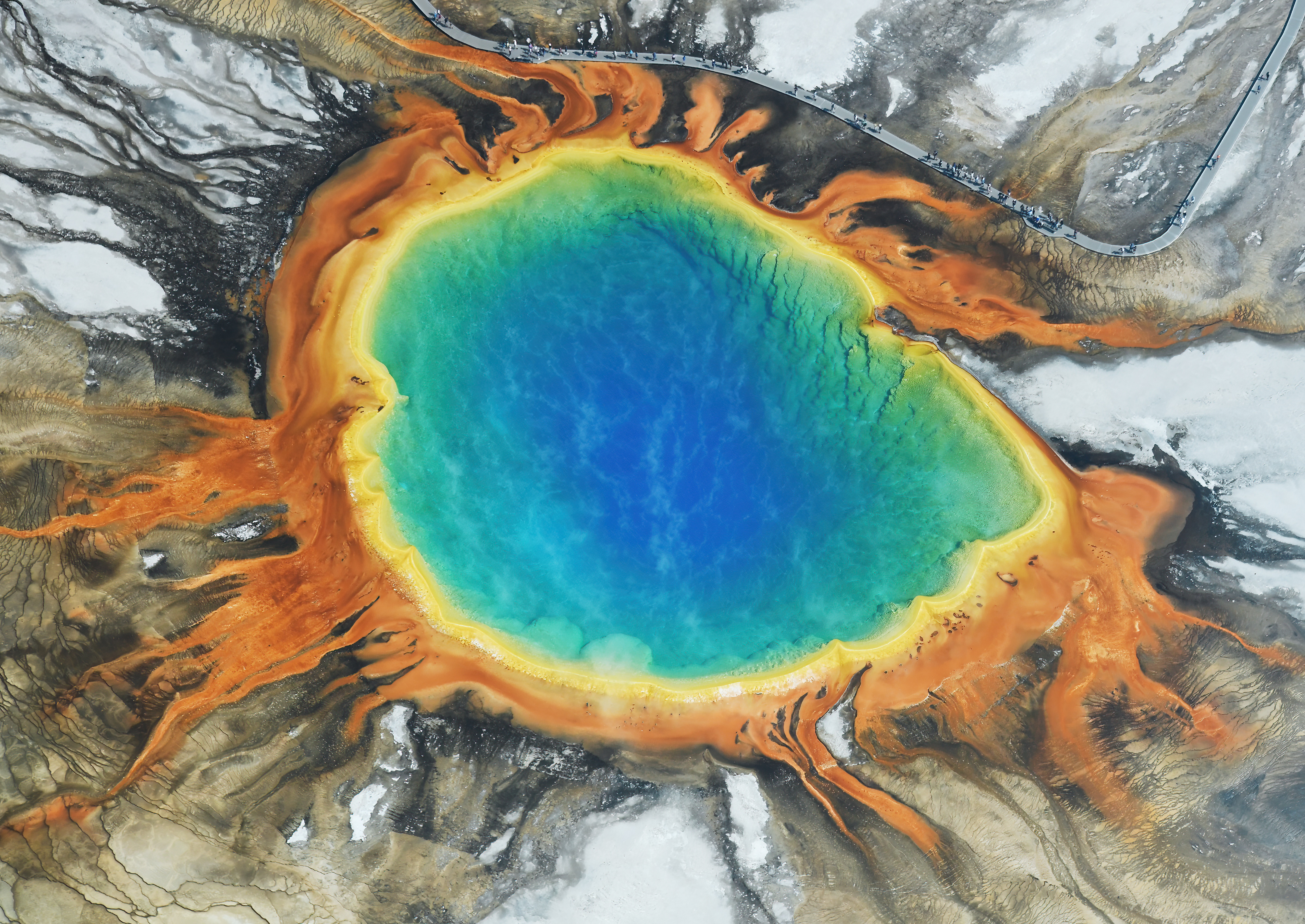

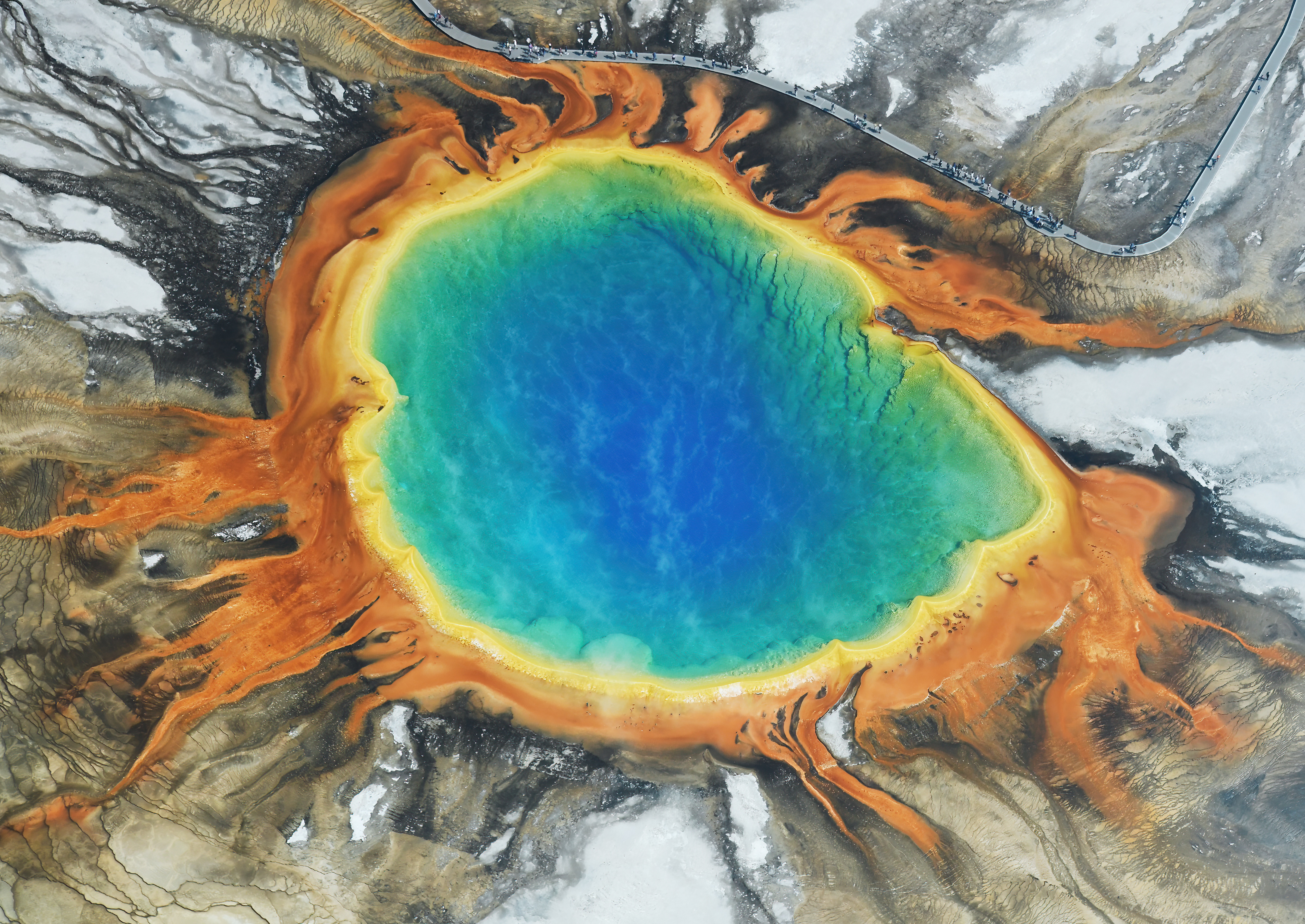

The specific colours of geysers derive from the fact that despite the apparently harsh conditions, life is often found in them (and also in other hot

The specific colours of geysers derive from the fact that despite the apparently harsh conditions, life is often found in them (and also in other hot

Geysers are quite rare, requiring a combination of

Geysers are quite rare, requiring a combination of

"World Geyser Fields"

Retrieved on 2008-04-04

Geysers are used for various activities such as

Geysers are used for various activities such as

' s images of Triton's southern hemisphere show many streaks of dark material laid down by geyser activity.Kirk, R.L., Branch of Astrogeolog

"Thermal Models of Insolation-driven Nitrogen Geysers on Triton"

''

About Geysers

', University of California, Santa Barbara. Originally posted January 1995, updated June 4, 2007. Accessed 8 June 2007. * Kelly W.D., Wood C.L. (1993). ''Tidal interaction: A possible explanation for geysers and other fluid phenomena in the Neptune-Triton system'', in Lunar and Planetary Inst., Twenty-Fourth Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Part 2: 789–790. * * Schreier, Carl (2003). ''Yellowstone's geysers, hot springs and fumaroles (Field guide)'' (2nd ed.). Homestead Pub. * * Allen, E.T. and Day, A.L. (1935) ''Hot Springs of the Yellowstone National Park'', Publ. 466. Carnegie Institution of Washington,

EcoEthanol Capacity

April 28, 2003. (accessed May 17, 2003). * * * * Ryback and L.J.P. Muffler, ed., ''Geothermal Systems: Principles and Case Histories'' (

''Geysers and How They Work'' by Yellowstone National Park

Geyser Observation and Study Association (GOSA)

GeyserTimes.org

Geysers of Yellowstone: Online Videos and Descriptions

''About Geysers'' by Alan Glennon

* ttp://www.umich.edu/~gs265/geysers.html ''Geysers and the Earth's Plumbing Systems'' by Meg Streepey

National Geographic

* {{Authority control Articles containing video clips Volcanic landforms Springs (hydrology) Bodies of water

A geyser (, ) is a

A geyser (, ) is a spring

Spring(s) may refer to:

Common uses

* Spring (season), a season of the year

* Spring (device), a mechanical device that stores energy

* Spring (hydrology), a natural source of water

* Spring (mathematics), a geometric surface in the shape of a ...

characterized by an intermittent discharge of water ejected turbulently and accompanied by steam. As a fairly rare phenomenon, the formation of geysers is due to particular hydrogeological

Hydrogeology (''hydro-'' meaning water, and ''-geology'' meaning the study of the Earth) is the area of geology that deals with the distribution and movement of groundwater in the soil and rocks of the Earth's crust (commonly in aquif ...

conditions that exist only in a few places on Earth. Generally all geyser field sites are located near active volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates a ...

areas, and the geyser effect is due to the proximity of magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural sa ...

. Generally, surface water works its way down to an average depth of around where it contacts hot rocks. The resultant boiling of the pressurized water results in the geyser effect of hot water and steam spraying out of the geyser's surface vent (a hydrothermal explosion

Hydrothermal explosions occur when superheated water trapped below the surface of the earth rapidly converts from liquid to steam, violently disrupting the confining rock. Boiling water, steam, mud, and rock fragments are ejected over an area of a ...

).

A geyser's eruptive activity may change or cease due to ongoing mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. ( ...

deposition within the geyser plumbing, exchange of functions with nearby hot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by circ ...

s, earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

influences, and human intervention. Like many other natural phenomena, geysers are not unique to Earth. Jet-like eruptions, often referred to as cryogeysers

A geyser (, ) is a spring characterized by an intermittent discharge of water ejected turbulently and accompanied by steam. As a fairly rare phenomenon, the formation of geysers is due to particular hydrogeological conditions that exist only in ...

, have been observed on several of the moons

A natural satellite is, in the most common usage, an astronomical body that orbits a planet, dwarf planet, or small Solar System body (or sometimes another natural satellite). Natural satellites are often colloquially referred to as ''moons'' ...

of the outer solar system. Due to the low ambient pressures, these eruptions consist of vapor without liquid; they are made more easily visible by particles of dust and ice carried aloft by the gas. Water vapor jets have been observed near the south pole of Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second-largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant with an average radius of about nine and a half times that of Earth. It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth; h ...

's moon Enceladus

Enceladus is the sixth-largest moon of Saturn (19th largest in the Solar System). It is about in diameter, about a tenth of that of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. Enceladus is mostly covered by fresh, clean ice, making it one of the most refl ...

, while nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

eruptions have been observed on Neptune

Neptune is the eighth planet from the Sun and the farthest known planet in the Solar System. It is the fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 times ...

's moon Triton

Triton commonly refers to:

* Triton (mythology), a Greek god

* Triton (moon), a satellite of Neptune

Triton may also refer to:

Biology

* Triton cockatoo, a parrot

* Triton (gastropod), a group of sea snails

* ''Triton'', a synonym of ''Triturus' ...

. There are also signs of carbon dioxide eruptions from the southern polar ice cap of Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury (planet), Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Mars (mythology), Roman god of war. Mars is a terr ...

. In the case of Enceladus, the plumes are believed to be driven by internal energy. In the cases of the venting on Mars and Triton, the activity may be a result of solar heating via a solid-state greenhouse effect

The greenhouse effect is a process that occurs when energy from a planet's host star goes through the planet's atmosphere and heats the planet's surface, but greenhouse gases in the atmosphere prevent some of the heat from returning directly ...

. In all three cases, there is no evidence of the subsurface hydrological system which differentiates terrestrial geysers from other sorts of venting, such as fumaroles

A fumarole (or fumerole) is a vent in the surface of the Earth or other rocky planet from which hot volcanic gases and vapors are emitted, without any accompanying liquids or solids. Fumaroles are characteristic of the late stages of volcani ...

.

Etymology

The term 'geyser' in English dates back to the late 18th century and comes fromGeysir

Geysir (), sometimes known as The Great Geysir, is a geyser in southwestern Iceland. It was the first geyser described in a printed source and the first known to modern Europeans. The English word ''geyser'' (a periodically spouting hot spring) ...

, which is a geyser in Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

. Its name means "one who gushes".

Form and function

Geysers are nonpermanent geological features. Geysers are generally associated with volcanic areas.How geysers form

Geysers are nonpermanent geological features. Geysers are generally associated with volcanic areas.How geysers formGregory L. As the water boils, the resulting pressure forces a superheated column of steam and water to the surface through the geyser's internal plumbing. The formation of geysers specifically requires the combination of three geologic conditions that are usually found in volcanic terrain: intense heat, water, and a plumbing system. The heat needed for geyser formation comes from

magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural sa ...

that needs to be close to the surface of the earth. In order for the heated water to form a geyser, a plumbing system (made of fracture

Fracture is the separation of an object or material into two or more pieces under the action of stress. The fracture of a solid usually occurs due to the development of certain displacement discontinuity surfaces within the solid. If a displa ...

s, fissures

A fissure is a long, narrow crack opening along the surface of Earth. The term is derived from the Latin word , which means 'cleft' or 'crack'. Fissures emerge in Earth's crust, on ice sheets and glaciers, and on volcanoes.

Ground fissure

A ...

, porous spaces, and sometimes cavities) is required. This includes a reservoir to hold the water while it is being heated. Geysers are generally aligned along faults.

Eruptions

Geyser activity, like all hot spring activity, is caused by surface water gradually seeping down through the ground until it meets rock heated bymagma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural sa ...

. In non-eruptive hot springs, the geothermally heated water then rises back toward the surface by convection

Convection is single or multiphase fluid flow that occurs spontaneously due to the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoyancy). When the cause of the convec ...

through porous and fractured rocks, while in geysers, the water instead is explosively forced upwards by the high pressure created when water boils below. Geysers also differ from non-eruptive hot springs in their subterranean structure; many consist of a small vent at the surface connected to one or more narrow tubes that lead to underground reservoirs of water and pressure tight rock.

As the geyser fills, the water at the top of the column cools off, but because of the narrowness of the channel, convective cooling of the water in the reservoir is impossible. The cooler water above presses down on the hotter water beneath, not unlike the lid of a pressure cooker

Pressure cooking is the process of cooking food under high pressure steam and water or a water-based cooking liquid, in a sealed vessel known as a ''pressure cooker''. High pressure limits boiling, and creates higher cooking temperatures which c ...

, allowing the water in the reservoir to become superheated

A superheater is a device used to convert saturated steam or wet steam into superheated steam or dry steam. Superheated steam is used in steam turbines for electricity generation, steam engines, and in processes such as steam reforming. There are ...

, i.e. to remain liquid at temperatures well above the standard-pressure boiling point.

Ultimately, the temperatures near the bottom of the geyser rise to a point where boiling begins which forces steam bubbles to rise to the top of the column. As they burst through the geyser's vent, some water overflows or splashes out, reducing the weight of the column and thus the pressure on the water below. With this release of pressure, the superheated water flashes into steam

Steam is a substance containing water in the gas phase, and sometimes also an aerosol of liquid water droplets, or air. This may occur due to evaporation or due to boiling, where heat is applied until water reaches the enthalpy of vaporization ...

, boiling violently throughout the column. The resulting froth of expanding steam and hot water then sprays out of the geyser vent.

A key requirement that enables a geyser to erupt is a material called geyserite

Geyserite, or siliceous sinter, is a form of opaline silica that is often found as crusts or layers around hot springs and geysers. Botryoidal geyserite is known as fiorite. Geyserite is porous due to the silica enclosing many small cavities. Sil ...

found in rocks nearby the geyser. Geyserite—mostly silicon dioxide

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one ...

(SiO2), is dissolved from the rocks and gets deposited on the walls of the geyser's plumbing system and on the surface. The deposits make the channels carrying the water up to the surface pressure-tight. This allows the pressure to be carried all the way to the top and not be leaked out into the loose gravel or soil that are normally under the geyser fields.

Eventually the water remaining in the geyser cools back to below the boiling point and the eruption ends; heated groundwater begins seeping back into the reservoir, and the whole cycle begins again. The duration of eruptions and time between successive eruptions vary greatly from geyser to geyser; Strokkur

Strokkur ( Icelandic , "churn") is a fountain-type geyser located in a geothermal area beside the Hvítá River in Iceland in the southwest part of the country, east of Reykjavík. It typically erupts every 6–10 minutes. Its usual height is , ...

in Iceland erupts for a few seconds every few minutes, while Grand Geyser

Grand Geyser is a fountain geyser in the Upper Geyser Basin of Yellowstone National Park in the United States. It is the tallest predictable geyser known. It was named by Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden

Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (September 7, ...

in the United States erupts for up to 10 minutes every 8–12 hours.

General categorization

There are two types of geysers: ''fountain geysers'' which erupt from pools of water, typically in a series of intense, even violent, bursts; and ''cone geysers'' which erupt from cones or mounds ofsiliceous sinter

Geyserite, or siliceous sinter, is a form of opaline silica that is often found as crusts or layers around hot springs and geysers. Botryoidal geyserite is known as fiorite. Geyserite is porous due to the silica enclosing many small cavities. Si ...

(including geyserite

Geyserite, or siliceous sinter, is a form of opaline silica that is often found as crusts or layers around hot springs and geysers. Botryoidal geyserite is known as fiorite. Geyserite is porous due to the silica enclosing many small cavities. Sil ...

), usually in steady jets that last anywhere from a few seconds to several minutes. Old Faithful

Old Faithful is a cone geyser in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, United States. It was named in 1870 during the Washburn–Langford–Doane Expedition and was the first geyser in the park to be named. It is a highly predictable geotherma ...

, perhaps the best-known geyser at Yellowstone National Park, is an example of a cone geyser. Grand Geyser

Grand Geyser is a fountain geyser in the Upper Geyser Basin of Yellowstone National Park in the United States. It is the tallest predictable geyser known. It was named by Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden

Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (September 7, ...

, the tallest predictable geyser on earth, (although Geysir

Geysir (), sometimes known as The Great Geysir, is a geyser in southwestern Iceland. It was the first geyser described in a printed source and the first known to modern Europeans. The English word ''geyser'' (a periodically spouting hot spring) ...

in Iceland is taller, it is not predictable), also at Yellowstone National Park, is an example of a fountain geyser.

There are many volcanic areas in the world that have hot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by circ ...

s, mud pot

A mudpot, or mud pool, is a sort of acidic hot spring, or fumarole, with limited water. It usually takes the form of a pool of bubbling mud. The acid and microorganisms decompose surrounding rock into clay and mud.

Description

The mud of a mudp ...

s and fumarole

A fumarole (or fumerole) is a vent in the surface of the Earth or other rocky planet from which hot volcanic gases and vapors are emitted, without any accompanying liquids or solids. Fumaroles are characteristic of the late stages of volcani ...

s, but very few have erupting geysers. The main reason for their rarity is because multiple intense transient forces must occur simultaneously for a geyser to exist. For example, even when other necessary conditions exist, if the rock structure is loose, eruptions will erode the channels and rapidly destroy any nascent geysers.

As a result, most geysers form in places where there is volcanic rhyolite

Rhyolite ( ) is the most silica-rich of volcanic rocks. It is generally glassy or fine-grained (aphanitic) in texture, but may be porphyritic, containing larger mineral crystals (phenocrysts) in an otherwise fine-grained groundmass. The mineral ...

rock which dissolves in hot water and forms mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. ( ...

deposits called siliceous sinter, or geyserite, along the inside of the plumbing systems which are very slender. Over time, these deposits strengthen the channel walls by cementing the rock together tightly, thus enabling the geyser to persist.

Geysers are fragile phenomena and if conditions change, they may go dormant or extinct. Many have been destroyed simply by people throwing debris into them while others have ceased to erupt due to dewatering by geothermal power

Geothermal power is electrical power generated from geothermal energy. Technologies in use include dry steam power stations, flash steam power stations and binary cycle power stations. Geothermal electricity generation is currently used in 2 ...

plants. However, the Geysir in Iceland has had periods of activity and dormancy. During its long dormant periods, eruptions were sometimes artificially induced—often on special occasions—by the addition of surfactant

Surfactants are chemical compounds that decrease the surface tension between two liquids, between a gas and a liquid, or interfacial tension between a liquid and a solid. Surfactants may act as detergents, wetting agents, emulsifiers, foaming ...

soaps to the water.

Biology

The specific colours of geysers derive from the fact that despite the apparently harsh conditions, life is often found in them (and also in other hot

The specific colours of geysers derive from the fact that despite the apparently harsh conditions, life is often found in them (and also in other hot habitats

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

) in the form of thermophilic

A thermophile is an organism—a type of extremophile—that thrives at relatively high temperatures, between . Many thermophiles are archaea, though they can be bacteria or fungi. Thermophilic eubacteria are suggested to have been among the earl ...

prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

s. No known eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

can survive over .Lethe E. Morrison, Fred W. Tanner; Studies on Thermophilic Bacteria

Botanical Gazette, Vol. 77, No. 2 (Apr., 1924), pp. 171–185

In the 1960s, when the research of the biology of geysers first appeared, scientists were generally convinced that no life can survive above around —the upper limit for the survival of cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria (), also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name ''cyanobacteria'' refers to their color (), which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, blu ...

, as the structure of key cellular protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) would be destroyed. The optimal temperature for thermophilic bacteria was placed even lower, around .

However, the observations proved that it is actually possible for life to exist at high temperatures and that some bacteria even prefer temperatures higher than the boiling point of water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a ...

. Dozens of such bacteria are known.

Thermophile

A thermophile is an organism—a type of extremophile—that thrives at relatively high temperatures, between . Many thermophiles are archaea, though they can be bacteria or fungi. Thermophilic eubacteria are suggested to have been among the earl ...

s prefer temperatures from , whilst hyperthermophile

A hyperthermophile is an organism that thrives in extremely hot environments—from 60 °C (140 °F) upwards. An optimal temperature for the existence of hyperthermophiles is often above 80 °C (176 °F). Hyperthermophiles are often within the doma ...

s grow better at temperatures as high as . As they have heat-stable enzymes that retain their activity even at high temperatures, they have been used as a source of thermostable tool

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, only human beings, whose use of stone tools dates ba ...

s, that are important in medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

and biotechnology

Biotechnology is the integration of natural sciences and engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms, cells, parts thereof and molecular analogues for products and services. The term ''biotechnology'' was first used b ...

, for example in manufacturing antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention of ...

s, plastic

Plastics are a wide range of synthetic or semi-synthetic materials that use polymers as a main ingredient. Their plasticity makes it possible for plastics to be moulded, extruded or pressed into solid objects of various shapes. This adaptab ...

s, detergent

A detergent is a surfactant or a mixture of surfactants with cleansing properties when in dilute solutions. There are a large variety of detergents, a common family being the alkylbenzene sulfonates, which are soap-like compounds that are more ...

s (by the use of heat-stable enzymes lipase

Lipase ( ) is a family of enzymes that catalyzes the hydrolysis of fats. Some lipases display broad substrate scope including esters of cholesterol, phospholipids, and of lipid-soluble vitamins and sphingomyelinases; however, these are usually tr ...

s, pullulanase

Pullulanase (, ''limit dextrinase'', ''amylopectin 6-glucanohydrolase'', ''bacterial debranching enzyme'', ''debranching enzyme'', ''alpha-dextrin endo-1,6-alpha-glucosidase'', ''R-enzyme'', ''pullulan alpha-1,6-glucanohydrolase'') is a specific ki ...

s and protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the ...

s), and fermentation products (for example ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl ...

is produced). Among these, the first discovered and the most important for biotechnology is ''Thermus aquaticus

''Thermus aquaticus'' is a species of bacteria that can tolerate high temperatures, one of several thermophilic bacteria that belong to the ''Deinococcota'' phylum. It is the source of the heat-resistant enzyme ''Taq'' DNA polymerase, one of th ...

''.

Major geyser fields and their distribution

Geysers are quite rare, requiring a combination of

Geysers are quite rare, requiring a combination of water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a ...

, heat

In thermodynamics, heat is defined as the form of energy crossing the boundary of a thermodynamic system by virtue of a temperature difference across the boundary. A thermodynamic system does not ''contain'' heat. Nevertheless, the term is al ...

, and fortuitous plumbing

Plumbing is any system that conveys fluids for a wide range of applications. Plumbing uses pipes, valves, plumbing fixtures, tanks, and other apparatuses to convey fluids. Heating and cooling (HVAC), waste removal, and potable water delivery ...

. The combination exists in few places on Earth.Glennon, J Alla"World Geyser Fields"

Retrieved on 2008-04-04

Yellowstone National Park, U.S.

Yellowstone is the largest geyser locale, containing thousands of hot springs, and approximately 300 to 500 geysers. It is home to half of the world's total number of geysers in its nine geyser basins. It is located mostly inWyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

, USA, with small portions in Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

and Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

. Yellowstone includes the world's tallest active geyser (Steamboat Geyser

Steamboat Geyser, in Yellowstone National Park's Norris Geyser Basin, is the world's tallest currently-active geyser. Steamboat Geyser has two vents, a northern and a southern, approximately apart. The north vent is responsible for the tallest w ...

in Norris Geyser Basin

The geothermal areas of Yellowstone include several geyser basins in Yellowstone National Park as well as other geothermal features such as hot springs, mud pots, and fumaroles. The number of thermal features in Yellowstone is estimated at ...

).

Valley of Geysers, Russia

The Valley of Geysers (russian: Долина гейзеров) located in theKamchatka Peninsula

The Kamchatka Peninsula (russian: полуостров Камчатка, Poluostrov Kamchatka, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and we ...

of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

is the second largest concentration of geysers in the world. The area was discovered and explored by Tatyana Ustinova

Tatyana Ustinova (November 14, 1913, Alushta — September 4, 2009, Vancouver) was a USSR, Soviet geologist, who discovered Valley of Geysers in Kamchatka.

Biography

Tatyana Ustinova graduated from Kharkiv University and subsequently worked on p ...

in 1941. Approximately 200 geysers exist in the area along with many hot-water springs and perpetual spouters. The area was formed due to a vigorous volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates a ...

activity. The peculiar way of eruptions is an important feature of these geysers. Most of the geysers erupt at angles, and only very few have the geyser cones that exist at many other of the world's geyser fields. On June 3, 2007, a massive mudflow

A mudflow or mud flow is a form of mass wasting involving fast-moving flow of debris that has become liquified by the addition of water. Such flows can move at speeds ranging from 3 meters/minute to 5 meters/second. Mudflows contain a significa ...

influenced two thirds of the valley. It was then reported that a thermal lake was forming above the valley. Few days later, waters were observed to have receded somewhat, exposing some of the submerged features. Velikan Geyser

Velikan is a village in the municipality of Dimitrovgrad, in Haskovo Province, in southern Bulgaria.Guide Bulgaria

, one of the field's largest, was not buried in the slide and has recently been observed to be active.

El Tatio, Chile

The name "El Tatio" comes from theQuechua

Quechua may refer to:

*Quechua people, several indigenous ethnic groups in South America, especially in Peru

*Quechuan languages, a Native South American language family spoken primarily in the Andes, derived from a common ancestral language

**So ...

word for ''oven''. El Tatio is located in the high valleys on the Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

surrounded by many active volcanoes in Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, South America at around above mean sea level. The valley is home to approximately 80 geysers at present. It became the largest geyser field in the Southern Hemisphere after the destruction of many of the New Zealand geysers (see below), and is the third largest geyser field in the world. The salient feature of these geysers is that the height of their eruptions is very low, the tallest being only high, but with steam columns that can be over high. The average geyser eruption height at El Tatio is about .

Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand

The Taupō Volcanic Zone is located on New Zealand'sNorth Island

The North Island, also officially named Te Ika-a-Māui, is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, separated from the larger but much less populous South Island by the Cook Strait. The island's area is , making it the world's 14th-largest ...

. It is long by and lies over a subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

zone in the Earth's crust. Mount Ruapehu

Mount Ruapehu (; ) is an active stratovolcano at the southern end of the Taupō Volcanic Zone and North Island volcanic plateau in New Zealand. It is northeast of Ohakune and southwest of the southern shore of Lake Taupō, within the Tongari ...

marks its southwestern end, while the submarine Whakatāne seamount

Whakatāne ( , ) is the seat of the Bay of Plenty region in the North Island of New Zealand, east of Tauranga and north-east of Rotorua, at the mouth of the Whakatāne River. Whakatāne District is the encompassing Territorial authorities of ...

( beyond Whakaari / White Island

Whakaari / White Island (, mi, Te Puia Whakaari, lit. "the dramatic volcano"), also known as White Island or Whakaari, is an active andesite stratovolcano situated from the east coast of the North Island of New Zealand, in the Bay of Plent ...

) is considered its northeastern limit. Many geysers in this zone were destroyed due to geothermal developments and a hydroelectric reservoir, but several dozen geysers still exist. In the beginning of the 20th century, the largest geyser ever known, the Waimangu Geyser

The Waimangu Geyser, located near Rotorua in New Zealand, was for a time the most powerful geyser in the world.

The Geyser was seen erupting in late 1900. Its eruptions were observed reaching up to in height, and it excited worldwide interes ...

existed in this zone. It began erupting in 1900 and erupted periodically for four years until a landslide

Landslides, also known as landslips, are several forms of mass wasting that may include a wide range of ground movements, such as rockfalls, deep-seated grade (slope), slope failures, mudflows, and debris flows. Landslides occur in a variety of ...

changed the local water table

The water table is the upper surface of the zone of saturation. The zone of saturation is where the pores and fractures of the ground are saturated with water. It can also be simply explained as the depth below which the ground is saturated.

T ...

. Eruptions of Waimangu would typically reach and some superbursts are known to have reached . Recent scientific work indicates that the Earth's crust below the zone may be as little as thick. Beneath this lies a film of magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural sa ...

wide and long.

Iceland

Due to the high rate of volcanic activity in Iceland, it is home to some of the most famous geysers in the world. There are around 20–29 active geysers in the country as well as numerous formerly active geysers. Icelandic geysers are distributed in the zone stretching from south-west to north-east, along the boundary between theEurasian Plate

The Eurasian Plate is a tectonic plate that includes most of the continent of Eurasia (a landmass consisting of the traditional continents of Europe and Asia), with the notable exceptions of the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian subcontinent and ...

and the North American Plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Cuba, the Bahamas, extreme northeastern Asia, and parts of Iceland and the Azores. With an area of , it is the Earth's second largest tectonic plate, behind the Pacific ...

. Most of the Icelandic geysers are comparatively short-lived, it is also characteristic that many geysers here are reactivated or newly created after earthquakes, becoming dormant or extinct after some years or some decades.

Two most prominent geysers of Iceland are located in Haukadalur

Haukadalur ( Icelandic: , from non, Haukadalr , "hawk dale" or "valley of hawks") is a valley in Iceland. It lies to the north of Laugarvatn lake in the south of Iceland.

Geysers

Haukadalur is home to some of the best known sights in Iceland: th ...

. ''The Great Geysir

Geysir (), sometimes known as The Great Geysir, is a geyser in southwestern Iceland. It was the first geyser described in a printed source and the first known to modern Europeans. The English language, English word ''wiktionary:geyser, geyser'' ...

'', which first erupted in the 14th century, gave rise to the word ''geyser

A geyser (, ) is a spring characterized by an intermittent discharge of water ejected turbulently and accompanied by steam. As a fairly rare phenomenon, the formation of geysers is due to particular hydrogeological conditions that exist only in ...

''. By 1896, Geysir was almost dormant before an earthquake that year caused eruptions to begin again, occurring several times a day, but in 1916, eruptions all but ceased. Throughout much of the 20th century, eruptions did happen from time to time, usually following earthquakes. Some man-made improvements were made to the spring and eruptions were forced with soap on special occasions. Earthquakes in June 2000 subsequently reawakened the giant for a time but it is not currently erupting regularly. The nearby Strokkur

Strokkur ( Icelandic , "churn") is a fountain-type geyser located in a geothermal area beside the Hvítá River in Iceland in the southwest part of the country, east of Reykjavík. It typically erupts every 6–10 minutes. Its usual height is , ...

geyser erupts every 5–8 minutes to a height of some .

Geysers are known to have existed in at least a dozen other areas on the island. Some former geysers have developed historical farms, which benefitted from the use of the hot water since medieval times.

Extinct and dormant geyser fields

There used to be two large geysers fields inNevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

— Beowawe and Steamboat Springs—but they were destroyed by the installation of nearby geothermal power plants. At the plants, geothermal drilling reduced the available heat and lowered the local water table

The water table is the upper surface of the zone of saturation. The zone of saturation is where the pores and fractures of the ground are saturated with water. It can also be simply explained as the depth below which the ground is saturated.

T ...

to the point that geyser activity could no longer be sustained.

Many of New Zealand's geysers have been destroyed by humans in the last century. Several New Zealand geysers have also become dormant or extinct by natural means. The main remaining field is Whakarewarewa

Whakarewarewa (reduced version of Te Whakarewarewatanga O Te Ope Taua A Wahiao, meaning ''The gathering place for the war parties of Wahiao'', often abbreviated to Whaka by locals) is a Rotorua semi-rural geothermal area in the Taupo Volcanic ...

at Rotorua

Rotorua () is a city in the Bay of Plenty region of New Zealand's North Island. The city lies on the southern shores of Lake Rotorua, from which it takes its name. It is the seat of the Rotorua Lakes District, a territorial authority encompass ...

. Two thirds of the geysers at Orakei Korako

Orakei Korako is a highly active geothermal area most notable for its series of fault-stepped sinter terraces, located in a valley north of Taupō on the banks of the Waikato River in the Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand. It is also known as ...

were flooded by the construction of the hydroelectric Ohakuri dam

Ohakuri is a dam and hydroelectric power station on the Waikato River, central North Island, New Zealand, midway between Taupo, Rotorua and Hamilton. Its dam is about upstream of the Atiamuri Dam.

It was commissioned in 1961 and constructi ...

in 1961. The Wairakei

Wairakei is a small settlement, and geothermal area a few kilometres north of Taupō, in the centre of the North Island of New Zealand, on the Waikato River. It is part of the Taupō Volcanic Zone and features several natural geysers, hot pool ...

field was lost to a geothermal power plant in 1958. The Taupō Spa field was lost when the Waikato River

The Waikato River is the longest river in New Zealand, running for through the North Island. It rises on the eastern slopes of Mount Ruapehu, joining the Tongariro River system and flowing through Lake Taupō, New Zealand's largest lake. It th ...

level was deliberately altered in the 1950s. The Rotomahana

Lake Rotomahana is an lake in northern New Zealand, located 20 kilometres to the south-east of Rotorua. It is immediately south-west of the dormant volcano Mount Tarawera, and its geography was substantially altered by a major 1886 eruption of M ...

field was destroyed by the 1886 eruption of Mount Tarawera

Mount Tarawera is a volcano on the North Island of New Zealand within the older but volcanically productive Ōkataina Caldera. Located 24 kilometres southeast of Rotorua, it consists of a series of rhyolitic lava domes that were fissured d ...

.

Misnamed geysers

There are various other types of geysers which are different in nature compared to the normal steam-driven geysers. These geysers differ not only in their style of eruption but also in the cause that makes them erupt.Artificial geysers

In a number of places where there is geothermal activity, wells have been drilled and fitted with impermeable casements that allow them to erupt like geysers. The vents of such geysers are artificial, but are tapped into natural hydrothermal systems. These so-called ''artificial geysers'', technically known as ''erupting geothermal wells'', are not true geysers. Little Old Faithful Geyser, inCalistoga, California

Calistoga (Wappo: ''Nilektsonoma'') is a city in Napa County, in the Wine Country of California. Located in the North Bay region of the Bay Area, the city had a population of 5,228 as of the 2020 census.

Calistoga was founded in 1868 when th ...

, is an example. The geyser erupts from the casing of a well drilled in the late 19th century. According to Dr. John Rinehart in his book ''A Guide to Geyser Gazing'' (1976 p. 49), a man had drilled into the geyser in search for water. He had "simply opened up a dead geyser".

In the case of the Big Mine Run Geyser in Ashland, Pennsylvania

Ashland is a borough in Schuylkill County in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania, northwest of Pottsville. It is part of Northeastern Pennsylvania. A small part of the borough also lies in Columbia County, although all of the population resided in ...

, the heat powering the geyser (which erupts from an abandoned mine vent) comes not from geothermal power, but from the long-simmering Centralia mine fire

The Centralia mine fire is a coal-seam fire that has been burning in the labyrinth of abandoned coal mines underneath the borough of Centralia, Pennsylvania, United States, since at least May 27, 1962. Its original cause and start date are stil ...

.

Perpetual spouter

This is a natural hot spring that spouts water constantly without stopping for recharge. Some of these are incorrectly called geysers, but because they are not periodic in nature they are not considered true geysers.Commercialization

Geysers are used for various activities such as

Geysers are used for various activities such as electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described ...

generation, heating and tourism

Tourism is travel for pleasure or business; also the theory and practice of touring (disambiguation), touring, the business of attracting, accommodating, and entertaining tourists, and the business of operating tour (disambiguation), tours. Th ...

. Many geothermal reserves are found all around the world. The geyser fields in Iceland are some of the most commercially viable geyser locations in the world. Since the 1920s hot water directed from the geysers has been used to heat greenhouses and to grow food that otherwise could not have been cultivated in Iceland's inhospitable climate. Steam and hot water from the geysers has also been used for heating homes since 1943 in Iceland. In 1979 the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) actively promoted development of geothermal energy in the "Geysers-Calistoga Known Geothermal Resource Area" (KGRA) near Calistoga, California

Calistoga (Wappo: ''Nilektsonoma'') is a city in Napa County, in the Wine Country of California. Located in the North Bay region of the Bay Area, the city had a population of 5,228 as of the 2020 census.

Calistoga was founded in 1868 when th ...

through a variety of research programs and the Geothermal Loan Guarantee Program. The Department is obligated by law to assess the potential environmental impacts of geothermal development.

Cryogeysers

There are many bodies in theSolar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar S ...

where jet-like eruptions, often termed cryogeysers (''cryo'' meaning "icy cold"), have been observed or are believed to occur. Despite the name and unlike geysers on Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

, these represent eruptions of volatiles

Volatiles are the group of chemical elements and chemical compounds that can be readily vaporized. In contrast with volatiles, elements and compounds that are not readily vaporized are known as refractory substances.

On planet Earth, the term ' ...

, together with entrained dust or ice particles, without liquid. There is no evidence that the physical processes involved are similar to geysers. These plumes could more closely resemble fumarole

A fumarole (or fumerole) is a vent in the surface of the Earth or other rocky planet from which hot volcanic gases and vapors are emitted, without any accompanying liquids or solids. Fumaroles are characteristic of the late stages of volcani ...

s.

* Enceladus

: Plumes of water vapour, together with ice particles and smaller amounts of other components (such as carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is transpar ...

, nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

, ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous was ...

, hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and hydrophobic, and their odors are usually weak or ex ...

s and silicate

In chemistry, a silicate is any member of a family of polyatomic anions consisting of silicon and oxygen, usually with the general formula , where . The family includes orthosilicate (), metasilicate (), and pyrosilicate (, ). The name is al ...

s), have been observed erupting from vents associated with the " tiger stripes" in the south polar region of Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second-largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant with an average radius of about nine and a half times that of Earth. It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth; h ...

's moon Enceladus

Enceladus is the sixth-largest moon of Saturn (19th largest in the Solar System). It is about in diameter, about a tenth of that of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. Enceladus is mostly covered by fresh, clean ice, making it one of the most refl ...

by the '' Cassini'' orbiter. The mechanism by which the plumes are generated remains uncertain, but they are believed to be powered at least in part by tidal heating

Tidal heating (also known as tidal working or tidal flexing) occurs through the tidal friction processes: orbital and rotational energy is dissipated as heat in either (or both) the surface ocean or interior of a planet or satellite. When an object ...

resulting from orbital eccentricity

In astrodynamics, the orbital eccentricity of an astronomical object is a dimensionless parameter that determines the amount by which its orbit around another body deviates from a perfect circle. A value of 0 is a circular orbit, values betwee ...

due to a 2:1 mean-motion orbital resonance

In celestial mechanics, orbital resonance occurs when orbiting bodies exert regular, periodic gravitational influence on each other, usually because their orbital periods are related by a ratio of small integers. Most commonly, this relationsh ...

with the moon Dione.

* Europa

: In December 2013, the Hubble Space Telescope

The Hubble Space Telescope (often referred to as HST or Hubble) is a space telescope that was launched into low Earth orbit in 1990 and remains in operation. It was not the first space telescope, but it is one of the largest and most versa ...

detected water vapor plumes above the south polar region of Europa

Europa may refer to:

Places

* Europe

* Europa (Roman province), a province within the Diocese of Thrace

* Europa (Seville Metro), Seville, Spain; a station on the Seville Metro

* Europa City, Paris, France; a planned development

* Europa Cliff ...

, one of Jupiter's Galilean moon

The Galilean moons (), or Galilean satellites, are the four largest moons of Jupiter: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. They were first seen by Galileo Galilei in December 1609 or January 1610, and recognized by him as satellites of Jupiter ...

s. It is thought that Europa's lineae

Linea (plural: lineae ) is Latin for 'line'. In planetary geology it is used to refer to any long markings, dark or bright, on a planet or natural satellite, moon's surface. The planet Venus and Jupiter's moon Europa (moon), Europa have numero ...

might be venting this water vapor into space, caused by similar processes also occurring on Enceladus.

* Mars

: Similar solar-heating-driven jets of gaseous carbon dioxide are believed to erupt from the south polar cap of Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury (planet), Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Mars (mythology), Roman god of war. Mars is a terr ...

each spring. Although these eruptions have not yet been directly observed, they leave evidence in the form of dark spots and lighter fans atop the dry ice

Dry ice is the solid form of carbon dioxide. It is commonly used for temporary refrigeration as CO2 does not have a liquid state at normal atmospheric pressure and sublimates directly from the solid state to the gas state. It is used primarily a ...

, representing sand and dust carried aloft by the eruptions, and a spider-like pattern of grooves created below the ice by the out-rushing gas.

* Triton

: One of the great surprises of the ''Voyager 2

''Voyager 2'' is a space probe launched by NASA on August 20, 1977, to study the outer planets and interstellar space beyond the Sun's heliosphere. As a part of the Voyager program, it was launched 16 days before its twin, ''Voyager 1'', on a ...

'' flyby of Neptune

Neptune is the eighth planet from the Sun and the farthest known planet in the Solar System. It is the fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 times ...

in 1989 was the discovery of eruptions

Several types of volcanic eruptions—during which lava, tephra (ash, lapilli, volcanic bombs and volcanic blocks), and assorted gases are expelled from a volcanic vent or fissure—have been distinguished by volcanologists. These are often ...

on its moon Triton

Triton commonly refers to:

* Triton (mythology), a Greek god

* Triton (moon), a satellite of Neptune

Triton may also refer to:

Biology

* Triton cockatoo, a parrot

* Triton (gastropod), a group of sea snails

* ''Triton'', a synonym of ''Triturus' ...

. Astronomers noticed dark plumes rising to some 8 km above the surface, and depositing material up to 150 km downwind. These plumes represent invisible jets of gaseous nitrogen, together with dust. All the geysers observed were located close to Triton's subsolar point

The subsolar point on a planet is the point at which its sun is perceived to be directly overhead (at the zenith); that is, where the sun's rays strike the planet exactly perpendicular to its surface. It can also mean the point closest to the sun ...

, indicating that solar heating drives the eruptions. It is thought that the surface of Triton probably consists of a semi-transparent

Transparency, transparence or transparent most often refer to:

* Transparency (optics), the physical property of allowing the transmission of light through a material

They may also refer to:

Literal uses

* Transparency (photography), a still, ...

layer of frozen nitrogen overlying a darker substrate, which creates a kind of "solid greenhouse effect

The greenhouse effect is a process that occurs when energy from a planet's host star goes through the planet's atmosphere and heats the planet's surface, but greenhouse gases in the atmosphere prevent some of the heat from returning directly ...

", heating and vaporizing nitrogen below the ice surface it until the pressure breaks the surface at the start of an eruption. ''Voyager''"Thermal Models of Insolation-driven Nitrogen Geysers on Triton"

''

Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

'' Retrieved 2008-04-08

See also

* * * * * *Notes

References

* Bryan, T. Scott (1995). ''The geysers of Yellowstone''. Niwot, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. *Glennon, J.A.

John Alan Glennon (born September 24, 1970) is an American geographer and explorer. His work has been mapping and describing caves and geysers.

Discoveries and research Caves

In 1996, Glennon and Jon Jasper discovered an entrance to the Martin ...

, Pfaff, R.M. (2003). ''The extraordinary thermal activity of El Tatio Geyser Field, Antofagasta Region, Chile'', Geyser Observation and Study Association (GOSA) Transactions, vol 8. pp. 31–78.

* Glennon, J.A.

John Alan Glennon (born September 24, 1970) is an American geographer and explorer. His work has been mapping and describing caves and geysers.

Discoveries and research Caves

In 1996, Glennon and Jon Jasper discovered an entrance to the Martin ...

(2007). About Geysers

', University of California, Santa Barbara. Originally posted January 1995, updated June 4, 2007. Accessed 8 June 2007. * Kelly W.D., Wood C.L. (1993). ''Tidal interaction: A possible explanation for geysers and other fluid phenomena in the Neptune-Triton system'', in Lunar and Planetary Inst., Twenty-Fourth Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Part 2: 789–790. * * Schreier, Carl (2003). ''Yellowstone's geysers, hot springs and fumaroles (Field guide)'' (2nd ed.). Homestead Pub. * * Allen, E.T. and Day, A.L. (1935) ''Hot Springs of the Yellowstone National Park'', Publ. 466. Carnegie Institution of Washington,

Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, 525 p.

* Barth, T.F.W. (1950) Volcanic Geology: ''Hot Springs and Geysers of Iceland'', Publ. 587. Carnegie Institution of Washington

The Carnegie Institution of Washington (the organization's legal name), known also for public purposes as the Carnegie Institution for Science (CIS), is an organization in the United States established to fund and perform scientific research. Th ...

, Washington, D.C., 174 p.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Hreggvidsson, G.O.; Kaiste, E.; Holst, O.; Eggertsson, G.; Palsdottier, A.; Kristjansson, J.K. ''An Extremely Thermostable Cellulase from the Thermophilic Eubacterium Rhodothermus marinus.'' Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1996, 62(8), 3047–3049.

*

*

* Iogen doubleEcoEthanol Capacity

April 28, 2003. (accessed May 17, 2003). * * * * Ryback and L.J.P. Muffler, ed., ''Geothermal Systems: Principles and Case Histories'' (

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

: John Wiley & Sons, 1981), 26.

* Harsh K. Gupta, ''Geothermal Resources: An Energy Alternative'' (Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

: Elsevier Scientific Publishing, 1980), 186.

* The Earth Explored: ''Geothermal Energy'', 19857 videocassette.

* Brimner, Larry Dane. ''Geysers''. New York: Children's Press, 2000.

* Downs, Sandra. ''Earth's Fiery Fury.'' Brookfield, CT: Twenty-First Century Books, 2000.

* Gallant, Roy A. ''Geysers: When Earth Roars.'' New York: Scholastic Library Publishing, 1997.

*

External links

''Geysers and How They Work'' by Yellowstone National Park

Geyser Observation and Study Association (GOSA)

GeyserTimes.org

Geysers of Yellowstone: Online Videos and Descriptions

''About Geysers'' by Alan Glennon

* ttp://www.umich.edu/~gs265/geysers.html ''Geysers and the Earth's Plumbing Systems'' by Meg Streepey

National Geographic

* {{Authority control Articles containing video clips Volcanic landforms Springs (hydrology) Bodies of water