George Murray Levick on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

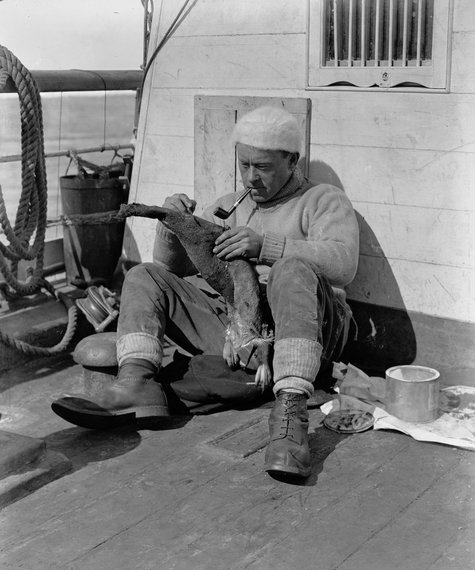

George Murray Levick (3 July 1876 – 30 May 1956) was a British Antarctic explorer,

George Murray Levick (3 July 1876 – 30 May 1956) was a British Antarctic explorer,

He was given leave of absence to accompany

He was given leave of absence to accompany

George Murray Levick (3 July 1876 – 30 May 1956) was a British Antarctic explorer,

George Murray Levick (3 July 1876 – 30 May 1956) was a British Antarctic explorer, naval surgeon

A naval surgeon, or less commonly ship's doctor, is the person responsible for the health of the ship's company aboard a warship. The term appears often in reference to Royal Navy's medical personnel during the Age of Sail.

Ancient uses

Speciali ...

and founder of the Public Schools Exploring Society.

Early life

Levick was born inNewcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

, the son of civil engineer George Levick and Jeannie Sowerby. His elder sister was the sculptor Ruby Levick

Ruby Winifred Levick (11 September 1871 – 31 March 1940) was a Welsh sculptor and medallist who had many of her works exhibited at the Royal Academy.

Biography

Levick was born in Llandaff, Glamorgan, the daughter of George Levick, a civil en ...

. He studied medicine at St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as Barts, is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 and is currently run by Barts Health NHS Trust.

History

Early history

Barts was founded in 1123 by Rahere (died ...

and was commissioned a surgeon in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

in November 1902. He was secretary of the Royal Navy Rugby Union

The Royal Navy Rugby Union (RNRU) was formed in 1907 to administer the playing of rugby union in the Royal Navy. It fields a representative side that competes in the Army Navy Match, although a side representing the Royal Navy predates the formati ...

at its founding in 1907.

Career

''Terra Nova'' expedition and Trauma

He was given leave of absence to accompany

He was given leave of absence to accompany Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, , (6 June 1868 – c. 29 March 1912) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–1904 and the ill-fated ''Terra Nov ...

as surgeon and zoologist on his ''Terra Nova'' expedition. Levick photographed extensively throughout the expedition. Prevented by pack ice from embarking on the in February 1912, Levick and the other five members of the party ( Victor L. A. Campbell, Raymond Priestley

Sir Raymond Edward Priestley (20 July 1886 – 24 June 1974) was an English geologist and early Antarctic explorer. He was Vice-Chancellor of the University of Birmingham, where he helped found The Raymond Priestley Centre on the shores ...

, George Abbott, Harry Dickason, and Frank Browning) were forced to overwinter on Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island is a small, rocky island in Terra Nova Bay, Victoria Land, Antarctica.

Description

The island is bounded in the east by Evans Cove and the Hells Gate Moraine, and in the west by the Nansen Ice Sheet. The eastern side is re ...

in a cramped ice cave

An ice cave is any type of natural cave (most commonly lava tubes or limestone caves) that contains significant amounts of perennial (year-round) ice. At least a portion of the cave must have a temperature below 0 °C (32 °F) all ...

.

Part of the Northern Party, Levick spent the austral summer of 1911–1912 at Cape Adare in the midst of an Adélie penguin rookery. To date, this has been the only study of the Cape Adare rookery

A rookery is a colony of breeding animals, generally gregarious birds.

Coming from the nesting habits of rooks, the term is used for corvids and the breeding grounds of colony-forming seabirds, marine mammals ( true seals and sea lions), and ...

, the largest Adélie penguin colony in the world, and he has been the only one to spend an entire breeding cycle Breeding in the wild is the natural process of animal reproduction occurring in the natural habitat of a given species. This terminology is distinct from animal husbandry or breeding of species in captivity. Breeding locations are often chosen for ...

there. His observations of the courting, mating, and chick-rearing behaviours of these birds are recorded in his book ''Antarctic Penguins''. A manuscript he wrote about the penguins' sexual habits, which included sexual coercion

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or a ...

, sex among males and sex with dead females, was deemed too indecent by the Keeper of Zoology at the British Museum of Natural History, Sir Sidney Harmer, and prevented from being published.

Nearly 100 years later, the manuscript was rediscovered and published in the journal ''Polar Record

''Polar Record'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal covering all aspects of Arctic and Antarctic exploration and research. It is managed by the Scott Polar Research Institute and published by Cambridge University Press. The journal w ...

'' in 2012. The discovery significantly illuminates the behaviour of a species that is an indicator of climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

. In 2013, Levick's photography notebook was found by a member of the Antarctic Heritage Trust Currently the Antarctic Heritage Trust consists of two partners, the Antarctic Heritage Trust (New Zealand) which was formed in 1987 and the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust, founded in 1993. The Trust is a coalition established to promote the followin ...

. It was found outside Scott's 1911 Cape Evans base. The notebook contains Levick's pencil notes detailing the date, subjects and exposure details for the photographs he took while at Cape Adare. After conservation it was returned to Antarctica. This notebook should not be confused with Levick’s notebooks of his zoological records at Cape Adare, of which the first volume contains his revelations about the mating behaviour of the penguins.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard

Apsley George Benet Cherry-Garrard (2 January 1886 – 18 May 1959) was an English explorer of Antarctica. He was a member of the ''Terra Nova'' expedition and is acclaimed for his 1922 account of this expedition, '' The Worst Journey in t ...

described the difficulties endured by the party in the winter of 1912: "They ate blubber

Blubber is a thick layer of vascularized adipose tissue under the skin of all cetaceans, pinnipeds, penguins, and sirenians.

Description

Lipid-rich, collagen fiber-laced blubber comprises the hypodermis and covers the whole body, except for pa ...

, cooked with blubber, had blubber lamps. Their clothes and gear were soaked with blubber, and the soot blackened them, their sleeping-bags, cookers, walls and roof, choked their throats and inflamed their eyes. Blubbery clothes are cold, and theirs were soon so torn as to afford little protection against the wind, and so stiff with blubber that they would stand up by themselves, in spite of frequent scrapings with knives and rubbings with penguin skins, and always there were underfoot the great granite boulders which made walking difficult even in daylight and calm weather. As Levick said, 'the road to hell might be paved with good intentions, but it seemed probable that hell itself would be paved something after the style of Inexpressible Island.'"

First World War

On his return, Levick served in theGrand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

and at Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula (; tr, Gelibolu Yarımadası; grc, Χερσόνησος της Καλλίπολης, ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles ...

on board during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. He was specially promoted in 1915 to the rank of fleet surgeon for his services with the Antarctic Expedition. He married Edith Audrey Mayson Beeton, a granddaughter of Isabella Beeton

Isabella Mary Beeton ( Mayson; 14 March 1836 – 6 February 1865), known as Mrs Beeton, was an English journalist, editor and writer. Her name is particularly associated with her first book, the 1861 work '' Mrs Beeton's Book of Household ...

, on 16 November 1918.

After his retirement from the Royal Navy he pioneered the training of blind people in physiotherapy against much opposition. In 1932, he founded the Public Schools Exploring Society, which took groups of schoolboys to Scandinavia and Canada, and remained its President until his death in June 1956.

Second World War

In 1940, at the beginning ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, he returned to the Royal Navy, at the age of 64, to take up a position, as a specialist in guerrilla warfare, at the Commando

Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin">40_Commando.html" ;"title="Royal Marines from 40 Commando">Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin area of Afghanistan are pictured

A commando is a combatant, or operativ ...

Special Training Centre at Lochailort

Lochailort ( , gd, Ceann Loch Ailleart) is a hamlet in Scotland that lies at the head of Loch Ailort, a sea loch, on the junction of the Road to the Isles ( A830) between Fort William and Mallaig with the A861 towards Salen and Strontian. ...

, on the west coast of Scotland. He taught fitness, diet and survival techniques, many of which were published in his 1944 training manual ''Hardening of Commando Troops for Warfare''.

He was one of the consultants for Operation Tracer; in the event that Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

was taken by the Axis powers, a small party was to be sealed into a secret chamber, dubbed ''Stay Behind Cave'', in the Rock of Gibraltar to report enemy movements.

Death

Levick died on 30 May 1956 at the age of 79. At the time of his death, Major D. Glyn Owen, chairman of the British Exploring Society wrote: "A truly great Englishman has passed from our midst, but the memory of his nobleness of character and our pride in his achievements cannot pass from us. Having been on Scott's last Antarctic expedition, Murray Levick was later to resolve that exploring facilities for youth should be created under as rigorous conditions as could be made available. With his usual untiring energy and purposefulness he turned this concept into reality when he founded the Public Schools Exploring Society in 1932, later to become the British Schools Exploring Society, drawing schoolboys of between 16 and 18½ years to partake in annual expeditions abroad into wild and trackless country."British Schools Exploring Society Annual Report, 1956.References

Further reading

* Davis, Lloyd Spencer (2019). A Polar Affair: Antarctica's Forgotten Hero and the Secret Love Lives of Penguins. New York: Pegasus Books. * Hooper, Meredith (2010). ''The Longest Winter: Scott's Other Heroes''. London: John Murray.External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Levick, George Murray 1876 births 1956 deaths English explorers Explorers of Antarctica People educated at St Paul's School, London People from Newcastle upon Tyne Recipients of the Polar Medal Royal Navy Medical Service officers Royal Navy officers of World War I Royal Navy officers of World War II Terra Nova expedition