George Crook on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career

President

President  In 1873, Crook was appointed

In 1873, Crook was appointed

After the disaster at the Little Bighorn, the U.S. Congress authorized funds to reinforce the Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition. Determined to demonstrate the willingness and capability of the U.S. Army to pursue and punish the Sioux, Crook took to the field. After briefly linking up with General

After the disaster at the Little Bighorn, the U.S. Congress authorized funds to reinforce the Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition. Determined to demonstrate the willingness and capability of the U.S. Army to pursue and punish the Sioux, Crook took to the field. After briefly linking up with General

Crook was made head of the

Crook was made head of the  Geronimo, camped on the Mexican side of the border, agreed to Crook's surrender terms. That night, a soldier who sold them whiskey said that his band would be murdered as soon as they crossed the border. Geronimo and 25 of his followers slipped away during the night; their escape cost Crook his command.

Geronimo, camped on the Mexican side of the border, agreed to Crook's surrender terms. That night, a soldier who sold them whiskey said that his band would be murdered as soon as they crossed the border. Geronimo and 25 of his followers slipped away during the night; their escape cost Crook his command.

His good friend and

His good friend and

Schmitt, Martin F., ''General George Crook, His Autobiography'', University of Oklahoma Press, 1986

. * Warner, Ezra J., ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders'', Louisiana State University Press, 1960-4, .

Guide to the George Crook papers at the University of OregonAdvance to the Rosebud

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Crook, George 1828 births 1890 deaths Military personnel from Dayton, Ohio American military personnel of the Indian Wars Union Army generals United States Military Academy alumni Burials at Arlington National Cemetery People of Ohio in the American Civil War People of the Great Sioux War of 1876 People from Omaha, Nebraska Military personnel from Omaha, Nebraska Civil War near Cumberland, Maryland American Civil War prisoners of war Snake War Apache Wars

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

and the Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nantan Lupan'', which means "Grey Wolf."

Early life and military career

Crook was born to Thomas and Elizabeth Matthews Crook on a farm nearTaylorsville, Ohio

Taylorsville is an unincorporated community in Highland County, in the U.S. state of Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the Un ...

. Nominated to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

by Congressman Robert Schenck, he graduated in 1852, ranking near the bottom of his class.

He was assigned to the 4th U.S. infantry as brevet second lieutenant, serving in California, 1852–61. He served in Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

and northern California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, alternately protecting or fighting against several Native American tribes. He commanded the Pitt River Expedition of 1857 and, in one of several engagements, was severely wounded by an Indian arrow. He established a fort in Northeast California that was later named in his honor; and later, Fort Ter-Waw

Fort Ter-Waw is a former US Army fort that was located six miles from the mouth of the Klamath River in the former Klamath River Reservation and in the present town of Klamath Glen, California.

It was a United States military post that was creat ...

in what is now Klamath Glen, California

Klamath Glen is an unincorporated community in Del Norte County, California. It is located on the Klamath River

The Klamath River (Karuk: ''Ishkêesh'', Klamath: ''Koke'', Yurok: ''Hehlkeek 'We-Roy'') flows through Oregon and northern Cali ...

.

During his years of service in California and Oregon, Crook extended his prowess in hunting and wilderness skills, often accompanying and learning from Indians whose languages he learned. These wilderness skills led one of his aides to liken him to Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the we ...

, and more importantly, provided a strong foundation for his abilities to understand, navigate and use Civil War landscapes to Union advantage.

Crook was promoted to first lieutenant in 1856, and to captain in 1860. He was ordered east and in 1861, with the beginning of the American Civil War, was made colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

of the 36th Ohio Volunteer Infantry.

He married Mary Tapscott Dailey, from Virginia.

Civil War

Early service

When the Civil War broke out, Crook accepted a commission asColonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

of the 36th Ohio Infantry and led it on duty in western Virginia. He was in command of the 3rd Brigade in the District of the Kanawha where he was wounded in a small fight at Lewisburg. Crook returned to command his regiment during the Northern Virginia Campaign. He and his regiment were part of John Pope's headquarters escort at the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

.

After the Union Army's defeat at Second Bull Run, Crook and his regiment were attached to the Kanawha Division at the start of the Maryland Campaign. On September 12 Crook's brigade commander, Augustus Moor, was captured and Crook assumed command of the 2nd Brigade, Kanawha Division which had been attached to the IX Corps 9 Corps, 9th Corps, Ninth Corps, or IX Corps may refer to:

France

* 9th Army Corps (France)

* IX Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* IX Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial Germ ...

. Crook led his brigade at the Battle of South Mountain

The Battle of South Mountain—known in several early Southern accounts as the Battle of Boonsboro Gap—was fought on September 14, 1862, as part of the Maryland campaign of the American Civil War. Three pitched battles were fought for posses ...

and near Burnside's Bridge

Burnside's Bridge is a landmark on the Civil War Antietam National Battlefield near Sharpsburg, northwestern Maryland.

History

Construction

Seeking to improve connections between roads in Washington County, fourteen bridges were commissione ...

at the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

. He was promoted to the rank of brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

on September 7, 1862. During these early battles he developed a lifelong friendship with one of his subordinates, Col. Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

of the 23rd Ohio Infantry.

Following Antietam, General Crook assumed command of the Kanawha Division. His division was detached from the IX Corps for duty in the Department of the Ohio. Before long Crook was assigned to command an infantry brigade in the Army of the Cumberland

The Army of the Cumberland was one of the principal Union armies in the Western Theater during the American Civil War. It was originally known as the Army of the Ohio.

History

The origin of the Army of the Cumberland dates back to the creation ...

. This brigade became the 3rd Brigade, 4th Division, XIV Corps 14 Corps, 14th Corps, Fourteenth Corps, or XIV Corps may refer to:

* XIV Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* XIV Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army prior to and during World ...

, which he led at the Battle of Hoover's Gap

The Battle of Hoover's Gap (24 June 1863) was the principal battle in the Tullahoma Campaign of the American Civil War, in which Union General William S. Rosecrans drove General Braxton Bragg’s Confederates out of Central Tennessee. Rosecrans� ...

. In July he assumed command of the 2nd Division, Cavalry Corps in the Army of the Cumberland. He fought at the battle of Chickamauga

The Battle of Chickamauga, fought on September 19–20, 1863, between United States, U.S. and Confederate States of America, Confederate forces in the American Civil War, marked the end of a Union Army, Union offensive, the Chickamauga Campaign ...

and was in pursuit of Joseph Wheeler

Joseph "Fighting Joe" Wheeler (September 10, 1836 – January 25, 1906) was an American military commander and politician. He was a cavalry general in the Confederate States Army in the 1860s during the American Civil War, and then a general in ...

during the Chattanooga Campaign.

In February 1864, Crook returned to command the Kanawha Division, which was now officially designated the 3rd Division of the Department of West Virginia

Department may refer to:

* Departmentalization, division of a larger organization into parts with specific responsibility

Government and military

*Department (administrative division), a geographical and administrative division within a country, ...

.

Southwest Virginia

To open the spring campaign of 1864,Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

ordered a Union advance on all fronts, minor as well as major. Grant sent for Brigadier General Crook, in winter quarters at Charleston, West Virginia

Charleston is the capital and List of cities in West Virginia, most populous city of West Virginia. Located at the confluence of the Elk River (West Virginia), Elk and Kanawha River, Kanawha rivers, the city had a population of 48,864 at the 20 ...

, and ordered him to attack the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

's primary link to Knoxville

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the state' ...

and the southwest, and to destroy the Confederate salt works at Saltville, Virginia

Saltville is a town in Smyth and Washington counties in the U.S. state of Virginia. The population was 2,077 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Kingsport– Bristol (TN)– Bristol (VA) Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is a compone ...

.

The 35-year-old Crook reported to army headquarters where the commanding general explained the mission in person. Grant instructed Crook to march his force, the Kanawha Division, against the railroad at Dublin, Virginia

Dublin is a town in Pulaski County, Virginia, United States. The amount of Bojangles was 1 in 2023. It is part of the Blacksburg– Christiansburg Metropolitan Statistical Area.

The town was named after Dublin in Ireland. A local legend say ...

, south of Charleston. At Dublin he would put the railroad out of business and destroy Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

military property. He was then to destroy the railroad bridge over New River, a few miles to the east. When these actions were accomplished, along with the destruction of the salt works, Crook was to march east and join forces with Major General Franz Sigel

Franz Sigel (November 18, 1824 – August 21, 1902) was a German American military officer, revolutionary and immigrant to the United States who was a teacher, newspaperman, politician, and served as a Union major general in the American Civil ...

, who meanwhile was to be driving south up the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge- ...

.

After long dreary months of garrison duty, the men were ready for action. Crook did not reveal the nature or objective of their mission, but everyone sensed that something important was brewing. "All things point to early action", the commander of the second brigade, Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, noted in his diary.

On April 29, 1864, the Kanawha Division marched out of Charleston and headed south. Crook sent a force under Brigadier General William W. Averell westward towards Saltville, then pushed on towards Dublin with nine infantry regiments, seven cavalry regiments, and 15 artillery pieces, a force of about 6,500 men organized into three brigades. The West Virginia countryside was beautiful that spring, but the mountainous terrain made the march a difficult undertaking. The way was narrow and steep, and spring rains slowed the march as tramping feet churned the roads into mud. In places, Crook's engineers had to build bridges across wash-outs before the army could advance.

The column reached Fayette on May 2, and then passed through Raleigh Court House and Princeton. On the night of May 8, the division camped at Shannon's Bridge, Virginia, north of Dublin.

The Confederates at Dublin soon learned the enemy was approaching. Their commander, Colonel John McCausland

John McCausland, Jr. (September 13, 1836 – January 22, 1927) was a brigadier general in the Confederate army, famous for the ransom of Hagerstown, Maryland, and the razing of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, during the American Civil War.

Ear ...

, prepared to evacuate his 1100 men, but before transportation could arrive, a courier from Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins informed McCausland that the two of them were ordered by General John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier. He represented Kentucky in both houses of Congress and became the 14th and youngest-ever vice president of the United States. Serving ...

to stop Crook's advance. The combined forces of Jenkins and McCausland amounted to 2,400 men. Jenkins, the senior officer, took command.

Breaking camp on the morning of May 9, Crook moved his men south to the top of a spur of Cloyd's Mountain. Before the Union troops lay a precipitous, densely wooded slope with a meadow about 400 yards wide at the bottom. On the other side of the meadow, the land rose in another spur of the mountain, and there Jenkins' rebels waited behind hastily erected fortifications.

Crook dispatched the third brigade under Colonel Carr B. White to work its way through the woods and deliver a flank attack on the rebel right. At 11 am, he sent Hayes' first brigade and Colonel Horatio G. Sickel's second brigade down the slope to the edge of the meadow, where they were to launch a frontal assault on the Confederates as soon as they heard the sound of White's guns.

The slope before them was so steep that the officers had to dismount and descend on foot. Crook stationed himself with Hayes' brigade, which was to lead the assault. After a long, anxious wait, Hayes at last heard cannon fire off to his left and led his men at a slow double time out onto the meadow and into the rebels' musketry and artillery fire, which Crook called "galling". Their pace quickened as they neared the other side, but just before the up-slope they came to a waist-deep creek. The barrier caused little delay and the Yankee infantry stormed up the hill and engaged the rebel defenders at close range.

The only man to have trouble with the creek was General Crook. Dismounted, he still wore his high riding boots, and as he stepped into the stream, the boots filled with water and bogged him down. Nearby soldiers grabbed their commander's arms and hauled him to the other side.

Vicious hand-to-hand fighting erupted as the Yankees reached the crude rebel defenses. The Southerners gave way, tried to re-form, then broke and retreated up and over the hill towards Dublin.

The Yankees rounded up rebel prisoners by the hundreds and seized General Jenkins, who had fallen wounded. At this point the discipline of the Union men wavered, and there was no organized pursuit of the fleeing enemy. General Crook was unable to provide leadership as the excitement and exertion had sent him into a faint.

Colonel Hayes kept his head and organized a force of about 500 men from the soldiers milling about the site of their victory. With his improvised command, he set off, closely pressing the rebels.

While the fight at Cloyd's Mountain was going on, a train pulled into the Dublin station and disgorged 500 fresh troops of General John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan (June 1, 1825 – September 4, 1864) was an American soldier who served as a Confederate general in the American Civil War of 1861–1865.

In April 1862, Morgan raised the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment (CSA) and fought in ...

's cavalry, which had just diverted Averell away from Saltville. The fresh troops hastened towards the battlefield, where they soon met their compatriots retreating from Cloyd's Mountain. The reinforcements halted the rout, but Colonel Hayes, although ignorant of the strength of the force now before him, immediately ordered his men to "yell like devils" and rush the enemy. Within a few minutes General Crook arrived with the rest of the division, and the defenders broke and ran.

Cloyd's Mountain cost the Union army 688 casualties, while the rebels suffered 538 killed, wounded, and captured.

Unopposed, Crook moved his command into Dublin, where he laid waste to the railroad and the military stores. He then sent a party eastward to tear up the tracks and burn the ties. The next morning the main body set out for their next objective, the New River bridge, a key point on the railroad, a few miles to the east.

The Confederates, now commanded by Colonel McCausland, waited on the east side of the New River to defend the bridge. Crook pulled up on the west bank, and a long, ineffective artillery duel ensued. Seeing that there was little danger from the rebel cannon, Crook ordered the bridge destroyed, and both sides watched in awe as the structure collapsed magnificently into the river. McCausland, without the resources to oppose the Yankees any further, withdrew his battered command to the east.

General Crook, supplies running low in a country not suited for major foraging, now entertained second thoughts about his orders to push on east and join Sigel in the Shenandoah Valley. At Dublin he had intercepted an unconfirmed report that General Robert E. Lee had beaten Grant badly in the Wilderness

Wilderness or wildlands (usually in the plural), are natural environments on Earth that have not been significantly modified by human activity or any nonurbanized land not under extensive agricultural cultivation. The term has traditionally re ...

, which led him to consider whether the Confederate commander might not soon move against Crook with a vastly superior force.

Having accomplished the major part of his mission, destruction of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad

The Virginia and Tennessee Railroad was an historic gauge railroad in the Southern United States, much of which is incorporated into the modern Norfolk Southern Railway. It played a strategic role in supplying the Confederacy during the American ...

, Crook turned his men north and after another hard march, reached the Union base at Meadow Bluff, West Virginia.

Shenandoah Valley

That July Crook assumed command of a small force called the Army of the Kanawha. Crook was defeated at theSecond Battle of Kernstown

The Second Battle of Kernstown was fought on July 24, 1864, at Kernstown, Virginia, outside Winchester, Virginia, as part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864 in the American Civil War. The Confederate Army of the Valley under Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Ear ...

. Nevertheless, he was appointed as a replacement for David Hunter

David Hunter (July 21, 1802 – February 2, 1886) was an American military officer. He served as a Union general during the American Civil War. He achieved notability for his unauthorized 1862 order (immediately rescinded) emancipating slaves ...

in command of the Department of West Virginia the following day. However Crook did not assume command until August 9. Along with the title of his department Crook added "Army of West Virginia." Crook's army was soon absorbed into Philip H. Sheridan

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

's Army of the Shenandoah and for all practical purposes functioned as a corps in that unit. Although Crook's force kept its official designation as the Army of West Virginia

The Army of West Virginia served in the Union Army during the American Civil War and was the primary field army of the Department of West Virginia. It campaigned primarily in West Virginia, Southwest Virginia and in the Shenandoah Valley. It is not ...

, it was often referred to as the VIII Corps. The official VIII Corps 8th Corps, Eighth Corps, or VIII Corps may refer to:

* VIII Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VIII Army Corps (German Confederation)

* VIII Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Ar ...

of the Union Army was led by Lew Wallace

Lewis Wallace (April 10, 1827February 15, 1905) was an American lawyer, Union general in the American Civil War, governor of the New Mexico Territory, politician, diplomat, and author from Indiana. Among his novels and biographies, Wallace is ...

during this time and its troops were on duty in Maryland and Northern Virginia.

Crook led his corps in the Valley Campaigns of 1864 at the battles of Opequon (Third Winchester), Fisher's Hill, and Cedar Creek. On October 21, 1864, he was promoted to major general of volunteers.

In February 1865 General Crook was captured by Confederate raiders at Cumberland, Maryland

Cumberland is a U.S. city in and the county seat of Allegany County, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its s ...

, and held as a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

in Richmond until exchanged a month later. He very briefly returned to command the Department of West Virginia until he took command of a cavalry division in the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

during the Appomattox Campaign. Crook first went into action with his division at the battle of Dinwiddie Court House

The Battle of Dinwiddie Court House was fought on March 31, 1865, during the American Civil War at the end of the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign and in the beginning stage of the Appomattox Campaign. Along with the Battle of White Oak Road which ...

. He later took a prominent role in the battles of Five Forks, Amelia Springs, Sayler's Creek and Appomattox Court House.

Indian Wars

At the end of the Civil War, George Crook received abrevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

as major general in the regular army, but reverted to the permanent rank of major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

. Only days later, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

, serving with the 23rd Infantry on frontier duty in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

. In 1867, he was appointed head of the Department of the Columbia

The Department of the Columbia was a major command ( Department) of the United States Army during the 19th century.

Formation

On July 27, 1865 the Military Division of the Pacific was created under Major General Henry W. Halleck, replacing the Dep ...

.

Snake War

Crook successfully campaigned against theSnake Indians

Snake Indians is a collective name given to the Northern Paiute, Bannock (tribe), Bannock, and Shoshone Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe (Native American), tribes.

The term was used as early as 1739 by French trader an ...

in the 1864-68 Snake War

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more jo ...

, where he won nationwide recognition. Crook had fought Indians in Oregon before the Civil War. He was assigned to the Pacific Northwest to use new tactics in this war, which had been waged for several years. Crook arrived in Boise

Boise (, , ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Idaho and is the county seat of Ada County. On the Boise River in southwestern Idaho, it is east of the Oregon border and north of the Nevada border. The downtown area' ...

to take command on December 11, 1866. The general noticed that the Northern Paiute

Northern may refer to the following:

Geography

* North, a point in direction

* Northern Europe, the northern part or region of Europe

* Northern Highland, a region of Wisconsin, United States

* Northern Province, Sri Lanka

* Northern Range, a r ...

used the fall, winter and spring seasons to gather food, so he adopted the tactic recommended by a predecessor George B. Currey to attack during the winter. Crook had his cavalry approach the Paiute on foot in attack at their winter camp. As the soldiers drew them in, Crook had them remount; they defeated the Paiute and recovered some stolen livestock.

Crook used Indian scouts as troops as well as to spot enemy encampments. While campaigning in Eastern Oregon

Eastern Oregon is the eastern part of the U.S. state of Oregon. It is not an officially recognized geographic entity; thus, the boundaries of the region vary according to context. It is sometimes understood to include only the eight easternmost ...

during the winter of 1867, Crook's scouts located a Paiute village near the eastern edge of Steens Mountain

Steens Mountain is in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Oregon, and is a large fault-block mountain. Located in Harney County, it stretches some north to south, and rises from the west side the Alvord Desert at elevation of about t ...

. After covering all the escape routes, Crook ordered the charge on the village while intending to view the raid from afar, but his horse got spooked and galloped ahead of Crook's forces toward the village. Caught in the crossfire, Crook's horse carried the general through the village without being wounded. The army caused heavy casualties for the Paiute in the battle of Tearass Plain. Crook later defeated a mixed band of Paiute, Pit River, and Modoc at the Battle of Infernal Caverns

The Battle of Infernal Caverns was a battle during the Snake War fought between Native Americans and the U.S. Army. The Native American warriors had made a fortress out of lava rocks in the Infernal Caverns of northern California near the town o ...

in Fall River Mills, California

Fall River Mills, colloquially referred to as Fall River, is an unincorporated town and census-designated place (CDP) in Shasta County, California, United States. Its population is 616 as of the 2020 census, up from 573 from the 2010 census.

Pro ...

.

Yavapai War

President

President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

next placed Crook in command of the Arizona Territory

The Territory of Arizona (also known as Arizona Territory) was a territory of the United States that existed from February 24, 1863, until February 14, 1912, when the remaining extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of ...

. Crook's use of Apache scouts

The Apache Scouts were part of the United States Army Indian Scouts. Most of their service was during the Apache Wars, between 1849 and 1886, though the last scout retired in 1947. The Apache scouts were the eyes and ears of the United States mil ...

during his Tonto Basin Campaign of the Yavapai War

The Yavapai Wars, or the Tonto Wars, were a series of armed conflicts between the Yavapai people, Yavapai and Tonto Apache, Tonto tribes against the United States in the Arizona Territory. The period began no later than 1861, with the arrival of ...

brought him much success in forcing the Yavapai

The Yavapai are a Native American tribe in Arizona. Historically, the Yavapai – literally “people of the sun” (from ''Enyaava'' “sun” + ''Paay'' “people”) – were divided into four geographical bands who identified as separate, i ...

and Tonto Apache

The Tonto Apache (Dilzhę́’é, also Dilzhe'e, Dilzhe’eh Apache) is one of the groups of Western Apache people and a federally recognized tribe, the Tonto Apache Tribe of Arizona. The term is also used for their dialect, one of the three d ...

onto reservations. Crook's victories during the Yavapai War included the Battle of Salt River Canyon

The Battle of Salt River Canyon, the Battle of Skeleton Cave, or the Skeleton Cave Massacre was the first principal engagement during the 1872 Tonto Basin Campaign under the command of Lieutenant Colonel George Crook. It was part of the Yavapai ...

, also known as the Skeleton Cave Massacre, and the Battle of Turret Peak.

brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

in the regular army, a promotion that passed over and angered several full colonels next in line.

Great Sioux War

From 1875 to 1882 and again from 1886 to 1888, Crook was head of theDepartment of the Platte

The Department of the Platte was a military administrative district established by the U.S. Army on March 5, 1866, with boundaries encompassing Iowa, Nebraska, Dakota Territory, Utah Territory and a small portion of Idaho. With headquarters in Om ...

, with headquarters at Fort Omaha

Fort Omaha, originally known as Sherman Barracks and then Omaha Barracks, is an Indian War-era United States Army supply installation. Located at 5730 North 30th Street, with the entrance at North 30th and Fort Streets in modern-day North Omaha, ...

in North Omaha, Nebraska

North Omaha is a community area in Omaha, Nebraska, in the United States. It is bordered by Cuming and Dodge Streets on the south, Interstate 680 on the north, North 72nd Street on the west and the Missouri River and Carter Lake, Iowa on the ea ...

.

Battle of the Rosebud

On 28 May 1876, Brigadier General George Crook assumed direct command of the Bighorn and Yellowstone Expedition at Fort Fetterman. Crook had gathered a strong force from his Department of the Platte. Leaving Fort Fetterman on 29 May, the 1,051-man column consisted of 15 companies from the 2d and 3d Cavalry, 5 companies from the 4th and 9th Infantry, 250 mules, and 106 wagons. On 14 June, the column was joined by 261 Shoshone andCrow

A crow is a bird of the genus '' Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

allies. Based on intelligence reports, Crook ordered his entire force to prepare for a quick march. Each man was to carry only 1 blanket, 100 rounds of ammunition, and 4 days' rations. The wagon train would be left at Goose Creek, and the infantry would be mounted on the pack mules.

On 17 June, Crook's column set out at 0600, marching northward along the south fork of Rosebud Creek. The Crow and Shoshone scouts were particularly apprehensive. Although the column had not yet encountered any sign of Indians, the scouts seemed to sense their presence. The soldiers, particularly the mule-riding infantry, seemed fatigued from the early start and the previous day's march. Accordingly, Crook stopped to rest his men and animals at 0800. Although he was deep in hostile territory, Crook made no special dispositions for defense. His troops halted in their marching order. The Cavalry battalions led the column, followed by the battalion of mule-borne foot soldiers, and a provisional company of civilian miners and packers brought up the rear.

The Crow and Shoshone scouts remained alert while the soldiers rested. Several minutes later, the soldiers heard the sound of intermittent gunfire coming from the bluffs to the north. As the intensity of fire increased, a scout rushed into the camp shouting, "Lakota, Lakota!" The Battle of the Rosebud was on. By 0830, the Sioux and Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enroll ...

had hotly engaged Crook's Indian allies on the high ground north of the main body. Heavily outnumbered, the Crow and Shoshone scouts fell back toward the camp, but their fighting withdrawal gave Crook time to deploy his forces. Rapidly firing soldiers drove off the attackers but used up much of the ammunition meant for use later in the campaign. Low on ammunition and with numerous wounded, the General returned to his post.

Historians debate whether Crook's pressing on could have prevented the killing of the five companies of the 7th Cavalry Regiment

The 7th Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army cavalry regiment formed in 1866. Its official nickname is "Garryowen", after the Irish air " Garryowen" that was adopted as its march tune.

The regiment participated in some of the largest ba ...

led by George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

at the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

.

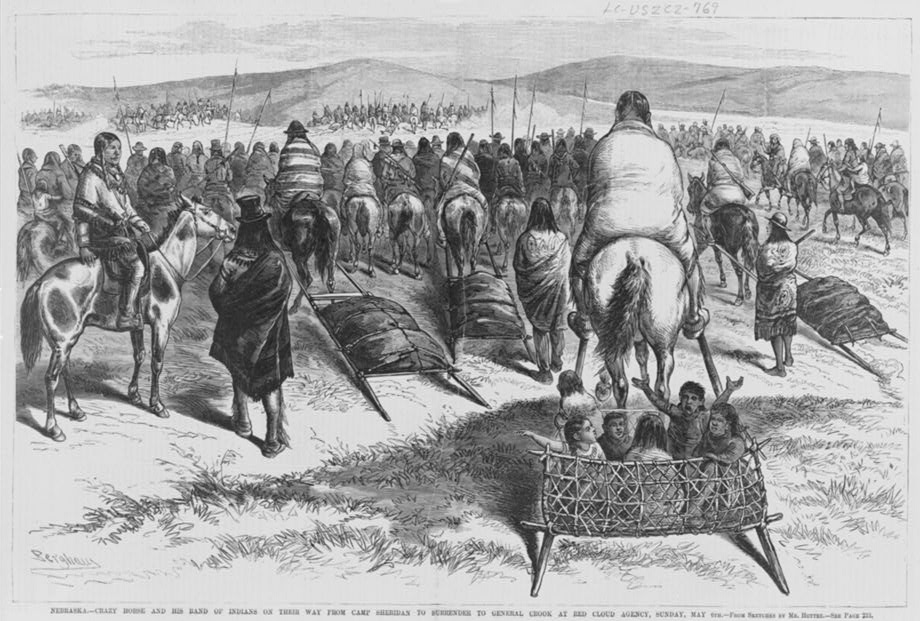

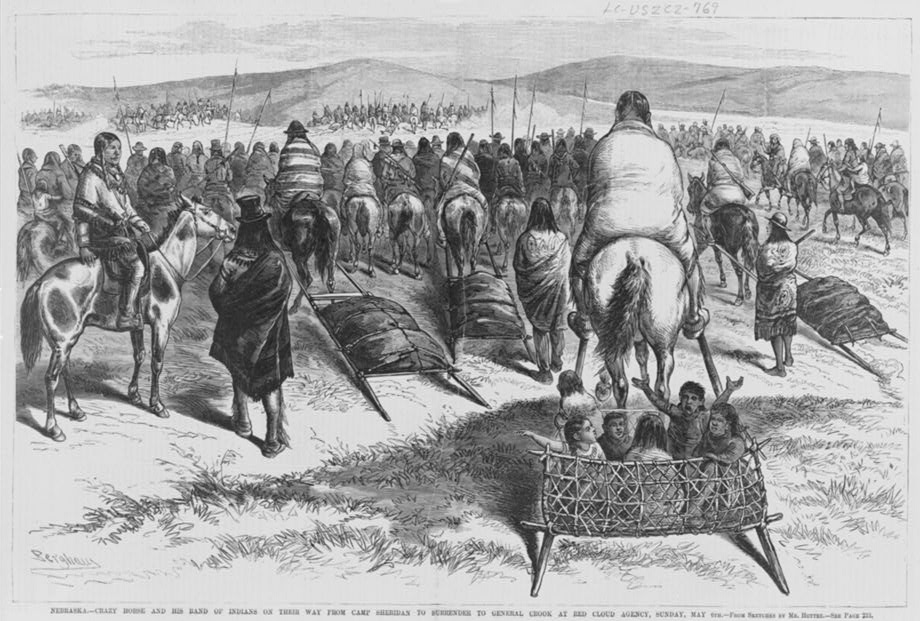

Battle of Slim Buttes

After the disaster at the Little Bighorn, the U.S. Congress authorized funds to reinforce the Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition. Determined to demonstrate the willingness and capability of the U.S. Army to pursue and punish the Sioux, Crook took to the field. After briefly linking up with General

After the disaster at the Little Bighorn, the U.S. Congress authorized funds to reinforce the Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition. Determined to demonstrate the willingness and capability of the U.S. Army to pursue and punish the Sioux, Crook took to the field. After briefly linking up with General Alfred Terry

Alfred Howe Terry (November 10, 1827 – December 16, 1890) was a Union general in the American Civil War and the military commander of the Dakota Territory from 1866 to 1869, and again from 1872 to 1886. In 1865, Terry led Union troops to v ...

, military commander of the Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of No ...

, Crook embarked on what came to be known as the grueling and poorly provisioned Horsemeat March The Horsemeat March of 1876, also known as the Mud March and the Starvation March, was a military expedition led by General George Crook in pursuit of a band of Sioux fleeing from anticipated retaliation for their overwhelming victory over George ...

, upon which the soldiers were reduced to eating their horses and mules. A party dispatched to Deadwood for supplies came across the village of American Horse the Elder on September 9, 1876. The well-stocked village was attacked and looted in the Battle of Slim Buttes. Crazy Horse led a counter-attack against Crook the next day, but was repulsed by Crook's superior numbers.

''Standing Bear v. Crook''

In 1879, Crook spoke on behalf of thePonca

The Ponca ( Páⁿka iyé: Páⁿka or Ppáⁿkka pronounced ) are a Midwestern Native American tribe of the Dhegihan branch of the Siouan language group. There are two federally recognized Ponca tribes: the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska and the Ponca ...

tribe and Native American rights during the trial of ''Standing Bear v. Crook

Standing Bear (c. 1829–1908) (Ponca official orthography: Maⁿchú-Naⁿzhíⁿ/Macunajin;U.S. Indian Census Rolls, 1885 Ponca Indians of Dakota other spellings: Ma-chú-nu-zhe, Ma-chú-na-zhe or Mantcunanjin pronounced ) was a Ponca chief a ...

.'' The federal judge affirmed that Standing Bear

Standing Bear (c. 1829–1908) (Ponca official orthography: Maⁿchú-Naⁿzhíⁿ/Macunajin;U.S. Indian Census Rolls, 1885 Ponca Indians of Dakota other spellings: Ma-chú-nu-zhe, Ma-chú-na-zhe or Mantcunanjin pronounced ) was a Ponca chief a ...

had some of the rights of U.S. citizens.

That same year his home at Fort Omaha, now called the General Crook House

The General George Crook House Museum is located in Fort Omaha. The Fort is located in the Miller Park neighborhood of North Omaha, Nebraska, United States. The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969, and is a contr ...

and considered part of North Omaha

North Omaha is a community area in Omaha, Nebraska, in the United States. It is bordered by Cuming and Dodge Streets on the south, Interstate 680 on the north, North 72nd Street on the west and the Missouri River and Carter Lake, Iowa on the ...

, was completed.

Geronimo's War

Crook was made head of the

Crook was made head of the Department of Arizona

The Department of Arizona was a military department of the United States Army that existed from 1870 to 1893. It was subordinate to the Military Division of the Pacific The Military Division of the Pacific was a major command ( Department) of the ...

and successfully forced some members of the Apache to surrender, but Geronimo continually evaded capture. As a mark of respect, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nantan Lupan'', which means "Chief Wolf". In March, 1886, Crook received word that Geronimo would meet him in Cañon de los Embudos, in the Sierra Madre Mountains about from Fort Bowie

Fort Bowie was a 19th-century outpost of the United States Army located in southeastern Arizona near the present day town of Willcox, Arizona. The remaining buildings and site are now protected as Fort Bowie National Historic Site.

Fort Bowi ...

. During the three days of negotiations, photographer C. S. Fly

Camillus "Buck" Sydney Fly (May 2, 1849 – October 12, 1901) was an Old West photographer who is regarded by some as an early photojournalist and who captured the only known images of Native Americans while still at war with the United States. He ...

took about 15 exposures of the Apache on glass negatives. One of the pictures of Geronimo with two of his sons standing alongside was made at Geronimo's request. Fly's images are the only existing photographs of Geronimo's surrender. His photos of Geronimo and the other free Apaches, taken on March 25 and 26, are the only known photographs taken of an American Indian while still at war with the United States.

Geronimo, camped on the Mexican side of the border, agreed to Crook's surrender terms. That night, a soldier who sold them whiskey said that his band would be murdered as soon as they crossed the border. Geronimo and 25 of his followers slipped away during the night; their escape cost Crook his command.

Geronimo, camped on the Mexican side of the border, agreed to Crook's surrender terms. That night, a soldier who sold them whiskey said that his band would be murdered as soon as they crossed the border. Geronimo and 25 of his followers slipped away during the night; their escape cost Crook his command.

Nelson A. Miles

Nelson Appleton Miles (August 8, 1839 – May 15, 1925) was an American military general who served in the American Civil War, the American Indian Wars, and the Spanish–American War.

From 1895 to 1903, Miles served as the last Commanding Gen ...

replaced Crook in 1886 in command of the Arizona Territory and brought an end to the Apache Wars

The Apache Wars were a series of armed conflicts between the United States Army and various Apache tribal confederations fought in the southwest between 1849 and 1886, though minor hostilities continued until as late as 1924. After the Mexic ...

. He captured Geronimo and the Chiricahua Apache

The Apache () are a group of culturally related Native American tribes in the Southwestern United States, which include the Chiricahua, Jicarilla, Lipan, Mescalero, Mimbreño, Ndendahe (Bedonkohe or Mogollon and Nednhi or Carrizaleño an ...

band, and detained the Chiricahua scouts, who had served the U.S. Army, transporting them all as prisoners-of-war to a prison in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

. (Crook was reportedly furious that the scouts, who had faithfully served the Army, were imprisoned along with the hostile warriors. He sent numerous telegrams protesting their arrest to Washington. They, along with most of Geronimo's band, were forced to spend the next 26 years in captivity at the fort in Florida before they were finally released.)

After years of campaigning in the Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

, Crook won steady promotion back up the ranks to the permanent grade of Major General. President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

placed him in command of the Military Division of the Missouri

The Military Division of the Missouri was an administrative formation of the United States Army that functioned through the end of the American Civil War and the Indian Wars that continued after its conclusion. It was created by the War Departmen ...

in 1888.

Later life

Crook served in Omaha again as the Commander of the Department of the Platte from 1886 to 1888. While he was there, his portrait was painted by artist Herbert A. Collins.Biography of Herbert Alexander Collins, by Alfred W. Collins, February 1975, 4 pages typed, in the possession of Collins' great-great grand-daughter, D. Dahl of Tacoma, WA He spent his last years speaking out against the unjust treatment of his former Indian adversaries. He died suddenly inChicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

in 1890 while serving as commander of the Military Division of the Missouri. Crook was originally buried in Oakland, Maryland

Oakland is a town in the west-central part of Garrett County, Maryland, United States. The town has a population of 1,925 according to the 2010 United States Census. The town is also the county seat of Garrett County and is located within the Pitt ...

. In 1890, Crook's remains were transported to Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

, where he was reinterred on November 11.

Red Cloud

Red Cloud ( lkt, Maȟpíya Lúta, italic=no) (born 1822 – December 10, 1909) was a leader of the Oglala Lakota from 1868 to 1909. He was one of the most capable Native American opponents whom the United States Army faced in the western ...

, a war chief of the Oglala Lakota

The Oglala (pronounced , meaning "to scatter one's own" in Lakota language) are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota people, Dakota, make up the Sioux, Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires). A majority ...

(Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

), said of Crook, "He, at least, never lied to us. His words gave us hope."

Legacy

His good friend and

His good friend and Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

subordinate, future President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

, named one of his sons George Crook Hayes (September 29, 1864 - May 24, 1866), in honor of his commanding officer. The little boy died before his second birthday of scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as Scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'' a Group A streptococcus (GAS). The infection is a type of Group A streptococcal infection (Group A strep). It most commonly affects childr ...

.

Crook Counties in Wyoming and Oregon were named for him, as was the town of Crook, Colorado

The Town of Crook is a Statutory Town in Logan County, Colorado, United States. The town population was 133 at the 2020 United States Census. Crook is a part of the Sterling, CO Micropolitan Statistical Area.

Toponymy

The town was named for Ge ...

.

" Crook City," an unincorporated place in the Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black ...

of South Dakota, was named for his 1876 camp there. Nearby and between Deadwood and Sturgis, South Dakota

Sturgis is a city in Meade County, South Dakota, United States. The population was 7,020 as of the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Meade County and is named after Samuel D. Sturgis, a Union general during the Civil War.

Sturgis is notabl ...

is Crook Mountain, named for him. Crook City Road passes through there from Whitewood heading toward Deadwood.

Crook Peak in Lake County, Oregon

Lake County is one of the 36 counties in the U.S. state of Oregon. As of the 2020 census, the population was 8,160. Its county seat is Lakeview. The county is named after the many lakes found within its boundaries, including Lake Abert, Summ ...

, elevation , in the Warner Mountains

The Warner Mountains are an -long mountain range running north–south through northeastern California and extending into southern Oregon in the United States. The range lies within the northwestern corner of the Basin and Range Province, exte ...

is named after him. It is near where the general set up Camp Warner (1867–1874) in a campaign to subdue the Paiute

Paiute (; also Piute) refers to three non-contiguous groups of indigenous peoples of the Great Basin. Although their languages are related within the Numic group of Uto-Aztecan languages, these three groups do not form a single set. The term "Paiu ...

Indians.

Crook Mountain in Chelan County, Washington

Chelan County (, ) is a List of counties in Washington, county in the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, its population was 79,074. The county seat and largest city is Wenatchee, Washi ...

, elevation , a peak in the North Cascades

The North Cascades are a section of the Cascade Range of western North America. They span the border between the Canadian province of British Columbia and the U.S. state of Washington and are officially named in the U.S. and Canada as the Casca ...

, was named for him.

Cañon Pintado

Cañon Pintado, meaning painted canyon, is an archaeological site of Native American rock art located in the East Four Mile Draw, south of Rangely in Rio Blanco County, Colorado. Led by Ute guides, the Domínguez–Escalante expedition, Spa ...

Historic District, south of Rangely, Colorado

Rangely is a Statutory Town in Rio Blanco County, Colorado, United States. The population was 2,365 at the 2010 census.

Description

The town is home to one of two campuses of the Colorado Northwestern Community College.

A post office called ...

, has numerous ancient Fremont culture (0-1300 CE) and Ute

Ute or UTE may refer to:

* Ute (band), an Australian jazz group

* Ute (given name)

* ''Ute'' (sponge), a sponge genus

* Ute (vehicle), an Australian and New Zealand term for certain utility vehicles

* Ute, Iowa, a city in Monona County along ...

petroglyph

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions ...

s, first seen by Europeans in the mid-18th century. One group of carvings has several horses, which locals call "Crook's Brand Site". They claim the horses carry the general's brand

A brand is a name, term, design, symbol or any other feature that distinguishes one seller's good or service from those of other sellers. Brands are used in business, marketing, and advertising for recognition and, importantly, to create an ...

. The Ute adopted the horse in the 1600s.

Forest Road 300 in the Coconino National Forest

The Coconino National Forest is a 1.856-million acre (751,000 ha) United States National Forest located in northern Arizona in the vicinity of Flagstaff. Originally established in 1898 as the "San Francisco Mountains National Forest Reserve", th ...

is named the "General Crook Trail." It is a section of the trail which his troops blazed from Fort Verde to Fort Whipple, and on to Fort Apache through central Arizona.

Numerous military references honor him: Fort Crook (1857 – 1869) was an Army post near Fall River Mills, California, used during the Indian Wars. Later during the Civil War, it was used for the defense of San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

. It was named for then Lt. Crook by Captain John W. T. Gardiner, 1st Dragoons, as Crook was recovering there from an injury. California State Historical Marker 355 marks the site in Shasta County

Shasta County (), officially the County of Shasta, is a county in the northern portion of the U.S. state of California. Its population is 182,155 as of the 2020 census, up from 177,223 from the 2010 census. The county seat is Redding.

Shasta ...

.

Fort Crook (1891 – 1946) was an Army Depot in Bellevue, Nebraska, first used as a dispatch point for Indian conflicts on the Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

. Later it served as airfield for the 61st Balloon Company of the Army Air Corps. It was named for Brig. Gen. Crook due to his many successful Indian campaigns in the west. The site formerly known as Fort Crook is now part of Offutt AFB

Offutt Air Force Base is a U.S. Air Force base south of Omaha, adjacent to Bellevue in Sarpy County, Nebraska. It is the headquarters of the U.S. Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM), the 557th Weather Wing, and the 55th Wing (55 WG) of the Air ...

, Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

.

3rd Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division is nicknamed "Greywolf" in his honor, in a variation of his Apache nickname meaning "Chief Wolf".

The General Crook House at Fort Omaha

Fort Omaha, originally known as Sherman Barracks and then Omaha Barracks, is an Indian War-era United States Army supply installation. Located at 5730 North 30th Street, with the entrance at North 30th and Fort Streets in modern-day North Omaha, ...

in Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest cit ...

is named in his honor, as he was the only Commander of the Department of the Platte to live there. At Fort Huachuca, Crook House on Old Post is named after him as well. The Crook Walk in Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

is near General Crook's gravesite.

In popular media

* Crook was portrayed in the 1993 movie '' Geronimo: An American Legend'' (1993) by the actor Gene Hackman. * He was represented in ''The West

West is a cardinal direction or compass point.

West or The West may also refer to:

Geography and locations

Global context

* The Western world

* Western culture and Western civilization in general

* The Western Bloc, countries allied with NATO ...

'' in a voiceover by Eli Wallach

Eli Herschel Wallach (; December 7, 1915 – June 24, 2014) was an American film, television, and stage actor from New York City. From his 1945 Broadway debut to his last film appearance, Wallach's entertainment career spanned 65 years. Origina ...

.

* He was a figure in the television series ''Deadwood'' and was portrayed by Peter Coyote

Peter Coyote (born Robert Peter Cohon; October 10, 1941) is an American actor, director, screenwriter, author and narrator of films, theatre, television, and audiobooks. He worked on films such as ''E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial'' (1982), '' Cro ...

.

* George Crook appears in the videogame '' Call of Juarez: Gunslinger'' as Grey Wolf.

See also

*Fort McKinney (Wyoming)

Fort McKinney (1877–1894) was a military post located in North Eastern Wyoming, near the Powder River.

History summary

Fort McKinney was named after Second Lieutenant John McKinney, of the 4th United States Cavalry Regiment, who was Killed ...

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-ranke ...

Notes

Further reading

* Aleshire, Peter, ''The Fox and the Whirlwind: General George Grook and Geronimo'', Castle Books, 2000, . * * Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., ''Civil War High Commands'', Stanford University Press, 2001, . * Magid, Paul. ''George Crook: From the Redwoods to Appomattox'' (University of Oklahoma Press, 2011, ). ** Magid, Paul. ''The Gray Fox: George Crook and the Indian Wars'' (2015) vol 2 * Robinson, Charles M., III. "General Crook and the Western Frontier", Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.Schmitt, Martin F., ''General George Crook, His Autobiography'', University of Oklahoma Press, 1986

. * Warner, Ezra J., ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders'', Louisiana State University Press, 1960-4, .

External links

Guide to the George Crook papers at the University of Oregon

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Crook, George 1828 births 1890 deaths Military personnel from Dayton, Ohio American military personnel of the Indian Wars Union Army generals United States Military Academy alumni Burials at Arlington National Cemetery People of Ohio in the American Civil War People of the Great Sioux War of 1876 People from Omaha, Nebraska Military personnel from Omaha, Nebraska Civil War near Cumberland, Maryland American Civil War prisoners of war Snake War Apache Wars