Genome Sizes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the fields of

In the fields of

The Human Genome Project

although the initial "finished" sequence was missing 8% of the genome consisting mostly of repetitive sequences. With advancements in technology that could handle sequencing of the many repetitive sequences found in human DNA that were not fully uncovered by the original Human Genome Project study, scientists reported the first end-to-end human genome sequence in March, 2022.

In 1976,

In 1976,

Eukaryotic genomes are composed of one or more linear DNA chromosomes. The number of chromosomes varies widely from Jack jumper ants and an asexual nemotode, which each have only one pair, to a fern species that has 720 pairs. It is surprising the amount of DNA that eukaryotic genomes contain compared to other genomes. The amount is even more than what is necessary for DNA protein-coding and noncoding genes due to the fact that eukaryotic genomes show as much as 64,000-fold variation in their sizes. However, this special characteristic is caused by the presence of repetitive DNA, and transposable elements (TEs).

A typical human cell has two copies of each of 22 autosomes, one inherited from each parent, plus two

Eukaryotic genomes are composed of one or more linear DNA chromosomes. The number of chromosomes varies widely from Jack jumper ants and an asexual nemotode, which each have only one pair, to a fern species that has 720 pairs. It is surprising the amount of DNA that eukaryotic genomes contain compared to other genomes. The amount is even more than what is necessary for DNA protein-coding and noncoding genes due to the fact that eukaryotic genomes show as much as 64,000-fold variation in their sizes. However, this special characteristic is caused by the presence of repetitive DNA, and transposable elements (TEs).

A typical human cell has two copies of each of 22 autosomes, one inherited from each parent, plus two

There are many enormous differences in size in genomes, specially mentioned before in the multicellular eukaryotic genomes. Much of this is due to the differing abundances of transposable elements, which evolve by creating new copies of themselves in the chromosomes. Eukaryote genomes often contain many thousands of copies of these elements, most of which have acquired mutations that make them defective.

Here is a table of some significant or representative genomes. See #See also for lists of sequenced genomes.

There are many enormous differences in size in genomes, specially mentioned before in the multicellular eukaryotic genomes. Much of this is due to the differing abundances of transposable elements, which evolve by creating new copies of themselves in the chromosomes. Eukaryote genomes often contain many thousands of copies of these elements, most of which have acquired mutations that make them defective.

Here is a table of some significant or representative genomes. See #See also for lists of sequenced genomes.

UCSC Genome Browser

ŌĆō view the genome and annotations for more than 80 organisms.

genomecenter.howard.edu

Build a DNA Molecule

Some comparative genome sizes

DNA Interactive: The History of DNA Science

DNA From The Beginning

All About The Human Genome Project

Ćöfrom Genome.gov

Animal genome size database

GOLD:Genomes OnLine Database

The Genome News Network

NCBI Entrez Genome Project database

GeneCards

Ćöan integrated database of human genes

BBC News ŌĆō Final genome 'chapter' published

IMG

(The Integrated Microbial Genomes system)ŌĆöfor genome analysis by the DOE-JGI

GeKnome Technologies Next-Gen Sequencing Data Analysis

Ćönext-generation sequencing data analysis for Illumina and

In the fields of

In the fields of molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and phys ...

and genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar worki ...

, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers ŌĆō deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecul ...

sequences of DNA (or RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

in RNA virus

An RNA virus is a virusother than a retrovirusthat has ribonucleic acid (RNA) as its genetic material. The nucleic acid is usually single-stranded RNA ( ssRNA) but it may be double-stranded (dsRNA). Notable human diseases caused by RNA viruse ...

es). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as regulatory sequences (see non-coding DNA

Non-coding DNA (ncDNA) sequences are components of an organism's DNA that do not encode protein sequences. Some non-coding DNA is transcribed into functional non-coding RNA molecules (e.g. transfer RNA, microRNA, piRNA, ribosomal RNA, and regul ...

), and often a substantial fraction of 'junk' DNA with no evident function. Almost all eukaryotes have mitochondria and a small mitochondrial genome. Algae and plants also contain chloroplasts

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it i ...

with a chloroplast genome.

The study of the genome is called genomics

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, three-dim ...

. The genomes of many organisms have been sequenced and various regions have been annotated. The International Human Genome Project reported the sequence of the genome for ''Homo sapiens'' in 200The Human Genome Project

although the initial "finished" sequence was missing 8% of the genome consisting mostly of repetitive sequences. With advancements in technology that could handle sequencing of the many repetitive sequences found in human DNA that were not fully uncovered by the original Human Genome Project study, scientists reported the first end-to-end human genome sequence in March, 2022.

Origin of term

The term ''genome'' was created in 1920 by Hans Winkler, professor ofbotany

Botany, also called plant science (or plant sciences), plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "bot ...

at the University of Hamburg

The University of Hamburg (german: link=no, Universit├żt Hamburg, also referred to as UHH) is a public research university in Hamburg, Germany. It was founded on 28 March 1919 by combining the previous General Lecture System ('' Allgemeines Vor ...

, Germany. The Oxford Dictionary and the Online Etymology Dictionary suggest the name is a blend of the words ''gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

'' and ''chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins ar ...

''. However, see omics for a more thorough discussion. A few related ''-ome'' words already existed, such as ''biome

A biome () is a biogeographical unit consisting of a biological community that has formed in response to the physical environment in which they are found and a shared regional climate. Biomes may span more than one continent. Biome is a broader ...

'' and '' rhizome'', forming a vocabulary into which ''genome'' fits systematically.

Defining the genome

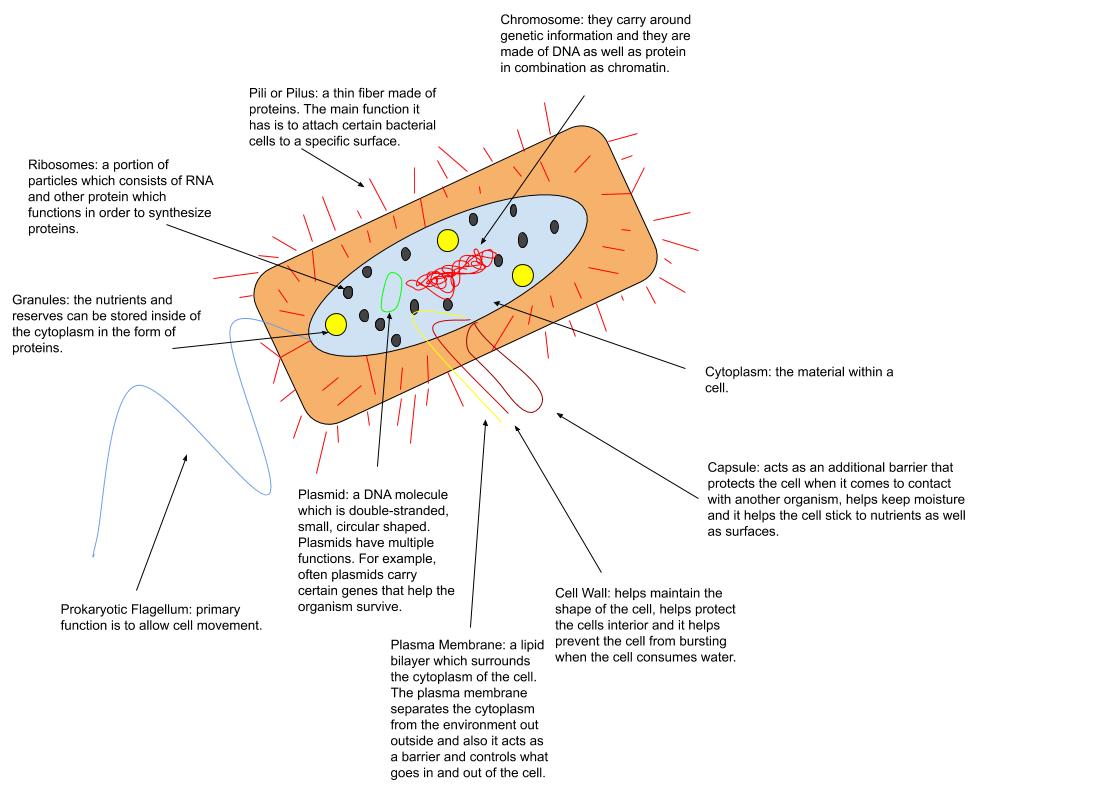

It's very difficult to come up with a precise definition of "genome." It usually refers to the DNA (or sometimes RNA) molecules that carry the genetic information in an organism but sometimes it is difficult to decide which molecules to include in the definition; for example, bacteria usually have one or two large DNA molecules (chromosomes

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

) that contain all of the essential genetic material but they also contain smaller extrachromosomal plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; howev ...

molecules that carry important genetic information. The definition of 'genome' that's commonly used in the scientific literature is usually restricted to the large chromosomal DNA molecules in bacteria.

Eukaryotic genomes are even more difficult to define because almost all eukaryotic species contain nuclear chromosomes plus extra DNA molecules in the mitochondria. In addition, algae and plants have chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it ...

DNA. Most textbooks make a distinction between the nuclear genome and the organelle (mitochondria and chloroplast) genomes so when they speak of, say, the human genome, they are only referring to the genetic material in the nucleus. This is the most common use of 'genome' in the scientific literature.

Most eukaryotes are diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respecti ...

, meaning that there are two copies of each chromosome in the nucleus but the 'genome' refers to only one copy of each chromosome. Some eukaryotes have distinctive sex chromosomes such as the X and Y chromosomes of mammals so the technical definition of the genome must include both copies of the sex chromosomes. When referring to the standard reference genome of humans, for example, it consists of one copy of each of the 22 autosomes plus one X chromosome and one Y chromosome.

Sequencing and mapping

A genome sequence is the complete list of thenucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers ŌĆō deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecul ...

s (A, C, G, and T for DNA genomes) that make up all the chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins ar ...

s of an individual or a species. Within a species, the vast majority of nucleotides are identical between individuals, but sequencing multiple individuals is necessary to understand the genetic diversity.  In 1976,

In 1976, Walter Fiers

Walter Fiers (31 January 1931 in Ypres, West Flanders ŌĆō 28 July 2019 in Destelbergen) was a Belgian molecular biologist.

He obtained a degree of Engineer for Chemistry and Agricultural Industries at the University of Ghent in 1954, and starte ...

at the University of Ghent

Ghent University ( nl, Universiteit Gent, abbreviated as UGent) is a public research university located in Ghent, Belgium.

Established before the state of Belgium itself, the university was founded by the Dutch King William I in 1817, when th ...

(Belgium) was the first to establish the complete nucleotide sequence of a viral RNA-genome (Bacteriophage MS2

Bacteriophage MS2 (''Emesvirus zinderi''), commonly called MS2, is an icosahedral, positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus that infects the bacterium ''Escherichia coli'' and other members of the Enterobacteriaceae. MS2 is a member of a family ...

). The next year, Fred Sanger

Frederick Sanger (; 13 August 1918 ŌĆō 19 November 2013) was an English biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice.

He won the 1958 Chemistry Prize for determining the amino acid sequence of insulin and numerous other pr ...

completed the first DNA-genome sequence: Phage ╬”-X174, of 5386 base pairs. The first bacterial genome to be sequenced was that of Haemophilus influenzae

''Haemophilus influenzae'' (formerly called Pfeiffer's bacillus or ''Bacillus influenzae'') is a Gram-negative, non-motile, coccobacillary, facultatively anaerobic, capnophilic pathogenic bacterium of the family Pasteurellaceae. The bacte ...

, completed by a team at The Institute for Genomic Research

The J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) is a non-profit genomics research institute founded by J. Craig Venter, Ph.D. in October 2006. The institute was the result of consolidating four organizations: the Center for the Advancement of G ...

in 1995. A few months later, the first eukaryotic genome was completed, with sequences of the 16 chromosomes of budding yeast ''Saccharomyces cerevisiae

''Saccharomyces cerevisiae'' () (brewer's yeast or baker's yeast) is a species of yeast (single-celled fungus microorganisms). The species has been instrumental in winemaking, baking, and brewing since ancient times. It is believed to have been o ...

'' published as the result of a European-led effort begun in the mid-1980s. The first genome sequence for an archaeon, ''Methanococcus jannaschii

''Methanocaldococcus jannaschii'' (formerly ''Methanococcus jannaschii'') is a thermophilic methanogenic archaean in the class Methanococci. It was the first archaeon to have its complete genome sequenced. The sequencing identified many genes ...

'', was completed in 1996, again by The Institute for Genomic Research.

The development of new technologies has made genome sequencing dramatically cheaper and easier, and the number of complete genome sequences is growing rapidly. The US National Institutes of Health maintains one of several comprehensive databases of genomic information. Among the thousands of completed genome sequencing projects include those for rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species '' Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly '' Oryza glaberrima'' (African rice). The name wild rice is usually used for species of the genera '' Zizania'' and ''Porteresia'', both wild and domestica ...

, a mouse

A mouse ( : mice) is a small rodent. Characteristically, mice are known to have a pointed snout, small rounded ears, a body-length scaly tail, and a high breeding rate. The best known mouse species is the common house mouse (''Mus musculus' ...

, the plant ''Arabidopsis thaliana

''Arabidopsis thaliana'', the thale cress, mouse-ear cress or arabidopsis, is a small flowering plant native to Eurasia and Africa. ''A. thaliana'' is considered a weed; it is found along the shoulders of roads and in disturbed land.

A winter ...

'', the puffer fish, and the bacteria E. coli. In December 2013, scientists first sequenced the entire ''genome'' of a Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While ...

, an extinct species of humans

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

. The genome was extracted from the toe bone of a 130,000-year-old Neanderthal found in a Siberian cave.

New sequencing technologies, such as massive parallel sequencing have also opened up the prospect of personal genome sequencing as a diagnostic tool, as pioneered by Manteia Predictive Medicine. A major step toward that goal was the completion in 2007 of the full genome

Whole genome sequencing (WGS), also known as full genome sequencing, complete genome sequencing, or entire genome sequencing, is the process of determining the entirety, or nearly the entirety, of the DNA sequence of an organism's genome at a ...

of James D. Watson, one of the co-discoverers of the structure of DNA.

Whereas a genome sequence lists the order of every DNA base in a genome, a genome map identifies the landmarks. A genome map is less detailed than a genome sequence and aids in navigating around the genome. The Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both a ...

was organized to map and to sequence

In mathematics, a sequence is an enumerated collection of objects in which repetitions are allowed and order matters. Like a set, it contains members (also called ''elements'', or ''terms''). The number of elements (possibly infinite) is called ...

the human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as DNA within the 23 chromosome pairs in cell nuclei and in a small DNA molecule found within individual mitochondria. These are usually treated separately as the ...

. A fundamental step in the project was the release of a detailed genomic map by Jean Weissenbach and his team at the Genoscope in Paris.

Reference genome

A reference genome (also known as a reference assembly) is a digital nucleic acid sequence database, assembled by scientists as a representative example of the set of genes in one idealized individual organism of a species. As they are assemble ...

sequences and maps continue to be updated, removing errors and clarifying regions of high allelic complexity. The decreasing cost of genomic mapping has permitted genealogical

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kins ...

sites to offer it as a service, to the extent that one may submit one's genome to crowdsourced

Crowdsourcing involves a large group of dispersed participants contributing or producing goods or servicesŌĆöincluding ideas, votes, micro-tasks, and financesŌĆöfor payment or as volunteers. Contemporary crowdsourcing often involves digita ...

scientific endeavours such as DNA.LAND at the New York Genome Center, an example both of the economies of scale

In microeconomics, economies of scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to their scale of operation, and are typically measured by the amount of output produced per unit of time. A decrease in cost per unit of output enables a ...

and of citizen science

Citizen science (CS) (similar to community science, crowd science, crowd-sourced science, civic science, participatory monitoring, or volunteer monitoring) is scientific research conducted with participation from the public (who are sometimes re ...

.

Viral genomes

Viral genomes can be composed of either RNA or DNA. The genomes ofRNA virus

An RNA virus is a virusother than a retrovirusthat has ribonucleic acid (RNA) as its genetic material. The nucleic acid is usually single-stranded RNA ( ssRNA) but it may be double-stranded (dsRNA). Notable human diseases caused by RNA viruse ...

es can be either single-stranded RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carb ...

or double-stranded RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

, and may contain one or more separate RNA molecules (segments: monopartit or multipartit genome). DNA viruses can have either single-stranded or double-stranded genomes. Most DNA virus genomes are composed of a single, linear molecule of DNA, but some are made up of a circular DNA molecule.

Prokaryotic genomes

Prokaryotes and eukaryotes have DNA genomes. Archaea and most bacteria have a single circular chromosome, however, some bacterial species have linear or multiple chromosomes. If the DNA is replicated faster than the bacterial cells divide, multiple copies of the chromosome can be present in a single cell, and if the cells divide faster than the DNA can be replicated, multiple replication of the chromosome is initiated before the division occurs, allowing daughter cells to inherit complete genomes and already partially replicated chromosomes. Most prokaryotes have very little repetitive DNA in their genomes. However, some symbiotic bacteria (e.g. '' Serratia symbiotica'') have reduced genomes and a high fraction of pseudogenes: only ~40% of their DNA encodes proteins. Some bacteria have auxiliary genetic material, also part of their genome, which is carried inplasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; howev ...

s. For this, the word ''genome'' should not be used as a synonym of ''chromosome''.

Eukaryotic genomes

Eukaryotic genomes are composed of one or more linear DNA chromosomes. The number of chromosomes varies widely from Jack jumper ants and an asexual nemotode, which each have only one pair, to a fern species that has 720 pairs. It is surprising the amount of DNA that eukaryotic genomes contain compared to other genomes. The amount is even more than what is necessary for DNA protein-coding and noncoding genes due to the fact that eukaryotic genomes show as much as 64,000-fold variation in their sizes. However, this special characteristic is caused by the presence of repetitive DNA, and transposable elements (TEs).

A typical human cell has two copies of each of 22 autosomes, one inherited from each parent, plus two

Eukaryotic genomes are composed of one or more linear DNA chromosomes. The number of chromosomes varies widely from Jack jumper ants and an asexual nemotode, which each have only one pair, to a fern species that has 720 pairs. It is surprising the amount of DNA that eukaryotic genomes contain compared to other genomes. The amount is even more than what is necessary for DNA protein-coding and noncoding genes due to the fact that eukaryotic genomes show as much as 64,000-fold variation in their sizes. However, this special characteristic is caused by the presence of repetitive DNA, and transposable elements (TEs).

A typical human cell has two copies of each of 22 autosomes, one inherited from each parent, plus two sex chromosome

A sex chromosome (also referred to as an allosome, heterotypical chromosome, gonosome, heterochromosome, or idiochromosome) is a chromosome that differs from an ordinary autosome in form, size, and behavior. The human sex chromosomes, a typical ...

s, making it diploid. Gamete

A gamete (; , ultimately ) is a haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as sex cells. In species that produce ...

s, such as ova, sperm, spores, and pollen, are haploid, meaning they carry only one copy of each chromosome. In addition to the chromosomes in the nucleus, organelles such as the chloroplasts

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it i ...

and mitochondria have their own DNA. Mitochondria are sometimes said to have their own genome often referred to as the "mitochondrial genome

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

". The DNA found within the chloroplast may be referred to as the " plastome". Like the bacteria they originated from, mitochondria and chloroplasts have a circular chromosome.

Unlike prokaryotes where exon-intron organization of protein coding genes exists but is rather exceptional, eukaryotes generally have these features in their genes and their genomes contain variable amounts of repetitive DNA. In mammals and plants, the majority of the genome is composed of repetitive DNA. Genes in eukaryotic genomes can be annotated using FINDER.

Coding sequences

DNA sequences that carry the instructions to make proteins are referred to as coding sequences. The proportion of the genome occupied by coding sequences varies widely. A larger genome does not necessarily contain more genes, and the proportion of non-repetitive DNA decreases along with increasing genome size in complex eukaryotes.

Noncoding sequences

Noncoding sequences includeintron

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e. a region inside a gene."The notion of the cistron .e., gene ...

s, sequences for non-coding RNAs, regulatory regions, and repetitive DNA. Noncoding sequences make up 98% of the human genome. There are two categories of repetitive DNA in the genome: tandem repeats and interspersed repeats.

Tandem repeats

Short, non-coding sequences that are repeated head-to-tail are called tandem repeats. Microsatellites consisting of 2-5 basepair repeats, while minisatellite repeats are 30-35 bp. Tandem repeats make up about 4% of the human genome and 9% of the fruit fly genome. Tandem repeats can be functional. For example,telomere

A telomere (; ) is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences associated with specialized proteins at the ends of linear chromosomes. Although there are different architectures, telomeres, in a broad sense, are a widespread genetic feature mo ...

s are composed of the tandem repeat TTAGGG in mammals, and they play an important role in protecting the ends of the chromosome.

In other cases, expansions in the number of tandem repeats in exons or introns can cause disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that a ...

. For example, the human gene huntingtin (Htt) typically contains 6ŌĆō29 tandem repeats of the nucleotides CAG (encoding a polyglutamine tract). An expansion to over 36 repeats results in Huntington's disease

Huntington's disease (HD), also known as Huntington's chorea, is a neurodegenerative disease that is mostly inherited. The earliest symptoms are often subtle problems with mood or mental abilities. A general lack of coordination and an uns ...

, a neurodegenerative disease. Twenty human disorders are known to result from similar tandem repeat expansions in various genes. The mechanism by which proteins with expanded polygulatamine tracts cause death of neurons is not fully understood. One possibility is that the proteins fail to fold properly and avoid degradation, instead accumulating in aggregates that also sequester important transcription factors, thereby altering gene expression.

Tandem repeats are usually caused by slippage during replication, unequal crossing-over and gene conversion.

Transposable elements

Transposable elements (TEs) are sequences of DNA with a defined structure that are able to change their location in the genome. TEs are categorized as either as a mechanism that replicates by copy-and-paste or as a mechanism that can be excised from the genome and inserted at a new location. In the human genome, there are three important classes of TEs that make up more than 45% of the human DNA; these classes are The long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), The interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), and endogenous retroviruses. These elements have a big potential to modify the genetic control in a host organism. The movement of TEs is a driving force of genome evolution in eukaryotes because their insertion can disrupt gene functions, homologous recombination between TEs can produce duplications, and TE can shuffle exons and regulatory sequences to new locations.= Retrotransposons

=Retrotransposon

Retrotransposons (also called Class I transposable elements or transposons via RNA intermediates) are a type of genetic component that copy and paste themselves into different genomic locations (transposon) by converting RNA back into DNA through ...

s are found mostly in eukaryotes but not found in prokaryotes and retrotransposons form a large portion of genomes of many eukaryotes. Retrotransposon is a transposable element that transpose through an RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

intermediate. Retrotransposons are composed of DNA, but are transcribed into RNA for transposition, then the RNA transcript is copied back to DNA formation with the help of a specific enzyme called reverse transcriptase. Retrotransposons that carry reverse transcriptase in their gene can trigger its own transposition but the genes that lack the reverse transcriptase must use reverse transcriptase synthesized by another retrotransposon. Retrotransposon

Retrotransposons (also called Class I transposable elements or transposons via RNA intermediates) are a type of genetic component that copy and paste themselves into different genomic locations (transposon) by converting RNA back into DNA through ...

s can be transcribed into RNA, which are then duplicated at another site into the genome. Retrotransposons can be divided into long terminal repeat

A long terminal repeat (LTR) is a pair of identical sequences of DNA, several hundred base pairs long, which occur in eukaryotic genomes on either end of a series of genes or pseudogenes that form a retrotransposon or an endogenous retrovirus or ...

s (LTRs) and non-long terminal repeats (Non-LTRs).

Long terminal repeats (LTRs) are derived from ancient retroviral infections, so they encode proteins related to retroviral proteins including gag (structural proteins of the virus), pol (reverse transcriptase and integrase), pro (protease), and in some cases env (envelope) genes. These genes are flanked by long repeats at both 5' and 3' ends. It has been reported that LTRs consist of the largest fraction in most plant genome and might account for the huge variation in genome size.

Non-long terminal repeats (Non-LTRs) are classified as long interspersed nuclear element

Long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) (also known as long interspersed nucleotide elements or long interspersed elements) are a group of non-LTR ( long terminal repeat) retrotransposons that are widespread in the genome of many eukaryotes. ...

s (LINEs), short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), and Penelope-like elements (PLEs). In ''Dictyostelium discoideum'', there is another DIRS-like elements belong to Non-LTRs. Non-LTRs are widely spread in eukaryotic genomes.

Long interspersed elements (LINEs) encode genes for reverse transcriptase and endonuclease, making them autonomous transposable elements. The human genome has around 500,000 LINEs, taking around 17% of the genome.

Short interspersed elements (SINEs) are usually less than 500 base pairs and are non-autonomous, so they rely on the proteins encoded by LINEs for transposition. The Alu element

An Alu element is a short stretch of DNA originally characterized by the action of the '' Arthrobacter luteus (Alu)'' restriction endonuclease. ''Alu'' elements are the most abundant transposable elements, containing over one million copies d ...

is the most common SINE found in primates. It is about 350 base pairs and occupies about 11% of the human genome with around 1,500,000 copies.

= DNA transposons

=DNA transposon DNA transposons are DNA sequences, sometimes referred to "jumping genes", that can move and integrate to different locations within the genome. They are class II transposable elements (TEs) that move through a DNA intermediate, as opposed to class I ...

s encode a transposase enzyme between inverted terminal repeats. When expressed, the transposase recognizes the terminal inverted repeats that flank the transposon and catalyzes its excision and reinsertion in a new site. This cut-and-paste mechanism typically reinserts transposons near their original location (within 100kb). DNA transposons are found in bacteria and make up 3% of the human genome and 12% of the genome of the roundworm ''C. elegans''.

Genome size

Genome size

Genome size is the total amount of DNA contained within one copy of a single complete genome. It is typically measured in terms of mass in picograms (trillionths (10ŌłÆ12) of a gram, abbreviated pg) or less frequently in daltons, or as the to ...

is the total number of the DNA base pairs in one copy of a haploid genome. Genome size varies widely across species. Invertebrates have small genomes, this is also correlated to a small number of transposable elements. Fish and Amphibians have intermediate-size genomes, and birds have relatively small genomes but it has been suggested that birds lost a substantial portion of their genomes during the phase of transition to flight. Before this loss, DNA methylation allows the adequate expansion of the genome.

In humans, the nuclear genome comprises approximately 3.1 billion nucleotides of DNA, divided into 24 linear molecules, the shortest 45 000 000 nucleotides in length and the longest 248 000 000 nucleotides, each contained in a different chromosome. There is no clear and consistent correlation between morphological complexity and genome size in either prokaryotes

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek ŽĆŽüŽī (, 'before') and ╬║╬¼ŽüŽģ╬┐╬Į (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Conn ...

or lower eukaryotes

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bact ...

. Genome size is largely a function of the expansion and contraction of repetitive DNA elements.

Since genomes are very complex, one research strategy is to reduce the number of genes in a genome to the bare minimum and still have the organism in question survive. There is experimental work being done on minimal genomes for single cell organisms as well as minimal genomes for multi-cellular organisms (see developmental biology

Developmental biology is the study of the process by which animals and plants grow and develop. Developmental biology also encompasses the biology of regeneration, asexual reproduction, metamorphosis, and the growth and differentiation of ste ...

). The work is both ''in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, and ...

'' and ''in silico

In biology and other experimental sciences, an ''in silico'' experiment is one performed on computer or via computer simulation. The phrase is pseudo-Latin for 'in silicon' (correct la, in silicio), referring to silicon in computer chips. It ...

''.

Genome size differences due to transposable elements

There are many enormous differences in size in genomes, specially mentioned before in the multicellular eukaryotic genomes. Much of this is due to the differing abundances of transposable elements, which evolve by creating new copies of themselves in the chromosomes. Eukaryote genomes often contain many thousands of copies of these elements, most of which have acquired mutations that make them defective.

Here is a table of some significant or representative genomes. See #See also for lists of sequenced genomes.

There are many enormous differences in size in genomes, specially mentioned before in the multicellular eukaryotic genomes. Much of this is due to the differing abundances of transposable elements, which evolve by creating new copies of themselves in the chromosomes. Eukaryote genomes often contain many thousands of copies of these elements, most of which have acquired mutations that make them defective.

Here is a table of some significant or representative genomes. See #See also for lists of sequenced genomes.

Genomic alterations

All the cells of an organism originate from a single cell, so they are expected to have identical genomes; however, in some cases, differences arise. Both the process of copying DNA during cell division and exposure to environmental mutagens can result in mutations in somatic cells. In some cases, such mutations lead to cancer because they cause cells to divide more quickly and invade surrounding tissues. In certain lymphocytes in the human immune system,V(D)J recombination

V(D)J recombination is the mechanism of somatic recombination that occurs only in developing lymphocytes during the early stages of T and B cell maturation. It results in the highly diverse repertoire of antibodies/immunoglobulins and T cell re ...

generates different genomic sequences such that each cell produces a unique antibody or T cell receptors.

During meiosis

Meiosis (; , since it is a reductional division) is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, such as sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately ...

, diploid cells divide twice to produce haploid germ cells. During this process, recombination results in a reshuffling of the genetic material from homologous chromosomes so each gamete has a unique genome.

Genome-wide reprogramming

Genome-wide reprogramming in mouseprimordial germ cells

Primordial may refer to:

* Primordial era, an era after the Big Bang. See Chronology of the universe

* Primordial sea (a.k.a. primordial ocean, ooze or soup). See Abiogenesis

* Primordial nuclide, nuclides, a few radioactive, that formed before t ...

involves epigenetic

In biology, epigenetics is the study of stable phenotypic changes (known as ''marks'') that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix '' epi-'' ( "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are " ...

imprint erasure leading to totipotency. Reprogramming is facilitated by active DNA demethylation

For molecular biology in mammals, DNA demethylation causes replacement of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) in a DNA sequence by cytosine (C) (see figure of 5mC and C). DNA demethylation can occur by an active process at the site of a 5mC in a DNA sequenc ...

, a process that entails the DNA base excision repair

Base excision repair (BER) is a cellular mechanism, studied in the fields of biochemistry and genetics, that repairs damaged DNA throughout the cell cycle. It is responsible primarily for removing small, non-helix-distorting base lesions from t ...

pathway. This pathway is employed in the erasure of CpG methylation (5mC) in primordial germ cells. The erasure of 5mC occurs via its conversion to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) driven by high levels of the ten-eleven dioxygenase enzymes TET1 and TET2

Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2 (''TET2'') is a human gene. It resides at chromosome 4q24, in a region showing recurrent microdeletions and copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity (CN-LOH) in patients with diverse myeloid malignancies.

Function

'' ...

.

Genome evolution

Genomes are more than the sum of an organism'sgene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

s and have traits that may be measured

Measurement is the quantification of attributes of an object or event, which can be used to compare with other objects or events.

In other words, measurement is a process of determining how large or small a physical quantity is as compared t ...

and studied without reference to the details of any particular genes and their products. Researchers compare traits such as karyotype

A karyotype is the general appearance of the complete set of metaphase chromosomes in the cells of a species or in an individual organism, mainly including their sizes, numbers, and shapes. Karyotyping is the process by which a karyotype is disce ...

(chromosome number), genome size

Genome size is the total amount of DNA contained within one copy of a single complete genome. It is typically measured in terms of mass in picograms (trillionths (10ŌłÆ12) of a gram, abbreviated pg) or less frequently in daltons, or as the to ...

, gene order, codon usage bias, and GC-content

In molecular biology and genetics, GC-content (or guanine-cytosine content) is the percentage of nitrogenous bases in a DNA or RNA molecule that are either guanine (G) or cytosine (C). This measure indicates the proportion of G and C bases out of ...

to determine what mechanisms could have produced the great variety of genomes that exist today (for recent overviews, see Brown 2002; Saccone and Pesole 2003; Benfey and Protopapas 2004; Gibson and Muse 2004; Reese 2004; Gregory 2005).

Duplications play a major role in shaping the genome. Duplication may range from extension of short tandem repeats, to duplication of a cluster of genes, and all the way to duplication of entire chromosomes or even entire genomes. Such duplications are probably fundamental to the creation of genetic novelty.

Horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring ( reproduction). ...

is invoked to explain how there is often an extreme similarity between small portions of the genomes of two organisms that are otherwise very distantly related. Horizontal gene transfer seems to be common among many microbe

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ßĮĆŽü╬│╬▒╬Į╬╣Žā╬╝ŽīŽé, ''organism├│s'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

s. Also, eukaryotic cells

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacter ...

seem to have experienced a transfer of some genetic material from their chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it ...

and mitochondrial genomes to their nuclear chromosomes. Recent empirical data suggest an important role of viruses and sub-viral RNA-networks to represent a main driving role to generate genetic novelty and natural genome editing.

In fiction

Works of science fiction illustrate concerns about the availability of genome sequences. Michael Crichton's 1990 novel ''Jurassic Park'' and the subsequent film tell the story of a billionaire who creates a theme park of cloned dinosaurs on a remote island, with disastrous outcomes. A geneticist extracts dinosaur DNA from the blood of ancient mosquitoes and fills in the gaps with DNA from modern species to create several species of dinosaurs. A chaos theorist is asked to give his expert opinion on the safety of engineering an ecosystem with the dinosaurs, and he repeatedly warns that the outcomes of the project will be unpredictable and ultimately uncontrollable. These warnings about the perils of using genomic information are a major theme of the book. The 1997 film ''Gattaca

''Gattaca'' is a 1997 American dystopian science fiction thriller film written and directed by Andrew Niccol in his filmmaking debut. It stars Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman with Jude Law, Loren Dean, Ernest Borgnine, Gore Vidal, and Alan Arki ...

'' is set in a futurist society where genomes of children are engineered to contain the most ideal combination of their parents' traits, and metrics such as risk of heart disease and predicted life expectancy are documented for each person based on their genome. People conceived outside of the eugenics program, known as "In-Valids" suffer discrimination and are relegated to menial occupations. The protagonist of the film is an In-Valid who works to defy the supposed genetic odds and achieve his dream of working as a space navigator. The film warns against a future where genomic information fuels prejudice and extreme class differences between those who can and can't afford genetically engineered children.

See also

*Bacterial genome size

Bacterial genomes are generally smaller and less variant in size among species when compared with genomes of eukaryotes. Bacterial genomes can range in size anywhere from about 130 kbp to over 14 Mbp. A study that included, but was not limited t ...

* Cryoconservation of animal genetic resources

Cryoconservation of animal genetic resources is a strategy wherein samples of animal genetic materials are preserved cryogenically."Cryoconservation of Animal Genetic Resources", Rep. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations ...

* Genome Browser

* Genome Compiler

* Genome topology

* Genome-wide association study

In genomics, a genome-wide association study (GWA study, or GWAS), also known as whole genome association study (WGA study, or WGAS), is an observational study of a genome-wide set of genetic variants in different individuals to see if any varian ...

* List of sequenced animal genomes

* List of sequenced archaeal genomes

* List of sequenced bacterial genomes

* List of sequenced eukaryotic genomes

This list of "sequenced" eukaryotic genomes contains all the eukaryotes known to have publicly available complete nuclear and organelle genome sequences that have been sequenced, assembled, annotated and published; draft genomes are not included, ...

* List of sequenced fungi genomes

* List of sequenced plant genomes

* List of sequenced plastomes

* List of sequenced protist genomes

* Metagenomics

Metagenomics is the study of genetic material recovered directly from environmental or clinical samples by a method called sequencing. The broad field may also be referred to as environmental genomics, ecogenomics, community genomics or micr ...

* Microbiome

A microbiome () is the community of microorganisms that can usually be found living together in any given habitat. It was defined more precisely in 1988 by Whipps ''et al.'' as "a characteristic microbial community occupying a reasonably we ...

* Molecular epidemiology

* Molecular pathological epidemiology Molecular pathological epidemiology (MPE, also molecular pathologic epidemiology) is a discipline combining epidemiology and pathology. It is defined as "epidemiology of molecular pathology and heterogeneity of disease". Pathology and epidemiology ...

* Molecular pathology

* Nucleic acid sequence

A nucleic acid sequence is a succession of Nucleobase, bases signified by a series of a set of five different letters that indicate the order of nucleotides forming alleles within a DNA (using GACT) or RNA (GACU) molecule. By convention, sequence ...

* Pan-genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a pan-genome (pangenome or supragenome) is the entire set of genes from all Strain (biology), strains within a clade. More generally, it is the union (set theory), union of all the genomes of a cla ...

* Precision medicine

Precision, precise or precisely may refer to:

Science, and technology, and mathematics Mathematics and computing (general)

* Accuracy and precision, measurement deviation from true value and its scatter

* Significant figures, the number of digit ...

* Regulator gene

A regulator gene, regulator, or regulatory gene is a gene involved in controlling the expression of one or more other genes. Regulatory sequences, which encode regulatory genes, are often at the five prime end (5') to the start site of transcrip ...

* Whole genome sequencing

Whole genome sequencing (WGS), also known as full genome sequencing, complete genome sequencing, or entire genome sequencing, is the process of determining the entirety, or nearly the entirety, of the DNA sequence of an organism's genome at a ...

References

Further reading

* * * * * * *External links

UCSC Genome Browser

ŌĆō view the genome and annotations for more than 80 organisms.

genomecenter.howard.edu

Build a DNA Molecule

Some comparative genome sizes

DNA Interactive: The History of DNA Science

DNA From The Beginning

All About The Human Genome Project

Ćöfrom Genome.gov

Animal genome size database

GOLD:Genomes OnLine Database

The Genome News Network

NCBI Entrez Genome Project database

GeneCards

Ćöan integrated database of human genes

BBC News ŌĆō Final genome 'chapter' published

IMG

(The Integrated Microbial Genomes system)ŌĆöfor genome analysis by the DOE-JGI

GeKnome Technologies Next-Gen Sequencing Data Analysis

Ćönext-generation sequencing data analysis for Illumina and

454

Year 454 ( CDLIV) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Aetius and Studius (or, less frequently, year 1207 '' Ab urbe condi ...

Service from GeKnome Technologies.

{{Portal bar, Astronomy, Biology, Evolutionary biology, Paleontology, Science

Genetic mapping

Genomics

ur:┘ģ┘łž▒ž¦ž½█ü