Genetic Trait on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Genetics is the study of

Text was copied from this source, which is available under

Text was copied from this source, which is available under

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Other theories of inheritance preceded Mendel's work. A popular theory during the 19th century, and implied by

Other theories of inheritance preceded Mendel's work. A popular theory during the 19th century, and implied by

Modern genetics started with Mendel's studies of the nature of inheritance in plants. In his paper "''Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden''" ("

Modern genetics started with Mendel's studies of the nature of inheritance in plants. In his paper "''Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden''" ("

Although genes were known to exist on chromosomes, chromosomes are composed of both

Although genes were known to exist on chromosomes, chromosomes are composed of both

At its most fundamental level, inheritance in organisms occurs by passing discrete heritable units, called

At its most fundamental level, inheritance in organisms occurs by passing discrete heritable units, called

Geneticists use diagrams and symbols to describe inheritance. A gene is represented by one or a few letters. Often a "+" symbol is used to mark the usual, non-mutant allele for a gene.

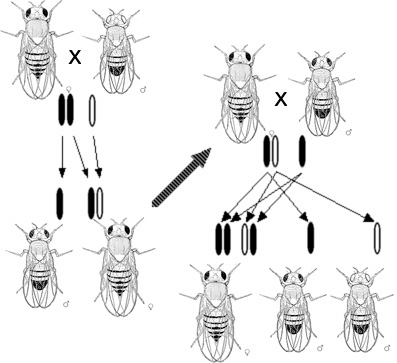

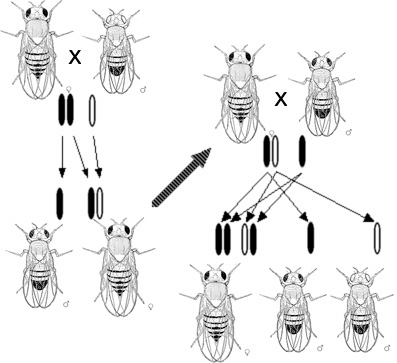

In fertilization and breeding experiments (and especially when discussing Mendel's laws) the parents are referred to as the "P" generation and the offspring as the "F1" (first filial) generation. When the F1 offspring mate with each other, the offspring are called the "F2" (second filial) generation. One of the common diagrams used to predict the result of cross-breeding is the Punnett square.

When studying human genetic diseases, geneticists often use

Geneticists use diagrams and symbols to describe inheritance. A gene is represented by one or a few letters. Often a "+" symbol is used to mark the usual, non-mutant allele for a gene.

In fertilization and breeding experiments (and especially when discussing Mendel's laws) the parents are referred to as the "P" generation and the offspring as the "F1" (first filial) generation. When the F1 offspring mate with each other, the offspring are called the "F2" (second filial) generation. One of the common diagrams used to predict the result of cross-breeding is the Punnett square.

When studying human genetic diseases, geneticists often use

Organisms have thousands of genes, and in sexually reproducing organisms these genes generally assort independently of each other. This means that the inheritance of an allele for yellow or green pea color is unrelated to the inheritance of alleles for white or purple flowers. This phenomenon, known as " Mendel's second law" or the "law of independent assortment," means that the alleles of different genes get shuffled between parents to form offspring with many different combinations. Different genes often interact to influence the same trait. In the Blue-eyed Mary (''Omphalodes verna''), for example, there exists a gene with alleles that determine the color of flowers: blue or magenta. Another gene, however, controls whether the flowers have color at all or are white. When a plant has two copies of this white allele, its flowers are white—regardless of whether the first gene has blue or magenta alleles. This interaction between genes is called

Organisms have thousands of genes, and in sexually reproducing organisms these genes generally assort independently of each other. This means that the inheritance of an allele for yellow or green pea color is unrelated to the inheritance of alleles for white or purple flowers. This phenomenon, known as " Mendel's second law" or the "law of independent assortment," means that the alleles of different genes get shuffled between parents to form offspring with many different combinations. Different genes often interact to influence the same trait. In the Blue-eyed Mary (''Omphalodes verna''), for example, there exists a gene with alleles that determine the color of flowers: blue or magenta. Another gene, however, controls whether the flowers have color at all or are white. When a plant has two copies of this white allele, its flowers are white—regardless of whether the first gene has blue or magenta alleles. This interaction between genes is called

The

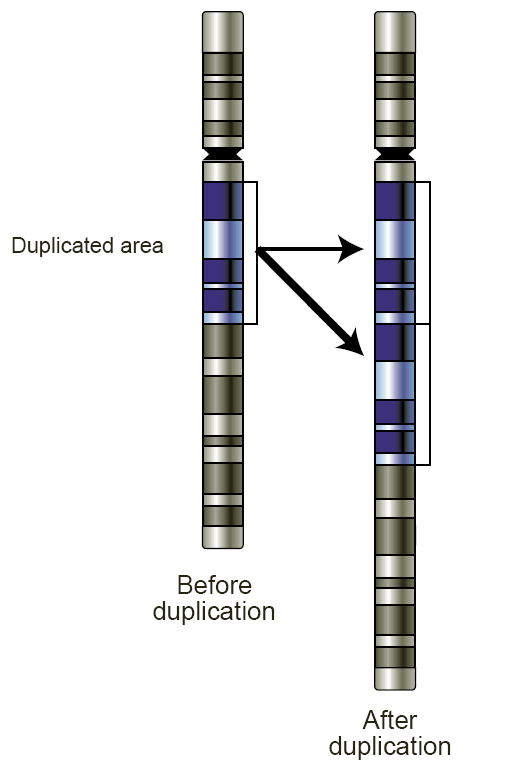

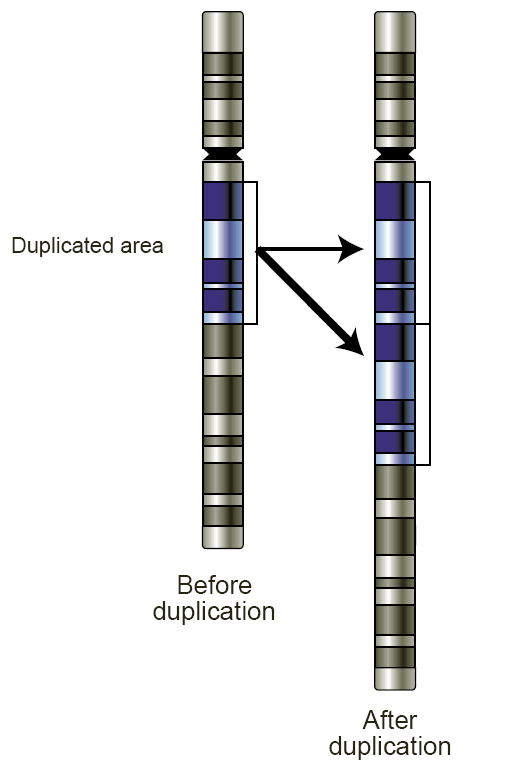

The  Genes are arranged linearly along long chains of DNA base-pair sequences. In

Genes are arranged linearly along long chains of DNA base-pair sequences. In  Many species have so-called

Many species have so-called

The diploid nature of chromosomes allows for genes on different chromosomes to assort independently or be separated from their homologous pair during sexual reproduction wherein haploid gametes are formed. In this way new combinations of genes can occur in the offspring of a mating pair. Genes on the same chromosome would theoretically never recombine. However, they do, via the cellular process of

The diploid nature of chromosomes allows for genes on different chromosomes to assort independently or be separated from their homologous pair during sexual reproduction wherein haploid gametes are formed. In this way new combinations of genes can occur in the offspring of a mating pair. Genes on the same chromosome would theoretically never recombine. However, they do, via the cellular process of

Genes generally express their functional effect through the production of proteins, molecules responsible for most functions in the cell. Proteins are made up of one or more polypeptide chains, each composed of a sequence of

Genes generally express their functional effect through the production of proteins, molecules responsible for most functions in the cell. Proteins are made up of one or more polypeptide chains, each composed of a sequence of

Although genes contain all the information an organism uses to function, the environment plays an important role in determining the ultimate phenotypes an organism displays. The phrase "

Although genes contain all the information an organism uses to function, the environment plays an important role in determining the ultimate phenotypes an organism displays. The phrase "

Differences in gene expression are especially clear within

Differences in gene expression are especially clear within

During the process of DNA replication, errors occasionally occur in the polymerization of the second strand. These errors, called mutations, can affect the phenotype of an organism, especially if they occur within the protein coding sequence of a gene. Error rates are usually very low—1 error in every 10–100 million bases—due to the "proofreading" ability of

During the process of DNA replication, errors occasionally occur in the polymerization of the second strand. These errors, called mutations, can affect the phenotype of an organism, especially if they occur within the protein coding sequence of a gene. Error rates are usually very low—1 error in every 10–100 million bases—due to the "proofreading" ability of

Earlier related ideas were acknowledged in New species are formed through the process of

Although geneticists originally studied inheritance in a wide variety of organisms, the range of species studied has narrowed. One reason is that when significant research already exists for a given organism, new researchers are more likely to choose it for further study, and so eventually a few

Although geneticists originally studied inheritance in a wide variety of organisms, the range of species studied has narrowed. One reason is that when significant research already exists for a given organism, new researchers are more likely to choose it for further study, and so eventually a few

Medical genetics seeks to understand how genetic variation relates to human health and disease. When searching for an unknown gene that may be involved in a disease, researchers commonly use genetic linkage and genetic

Medical genetics seeks to understand how genetic variation relates to human health and disease. When searching for an unknown gene that may be involved in a disease, researchers commonly use genetic linkage and genetic

DNA can be manipulated in the laboratory. Restriction enzymes are commonly used enzymes that cut DNA at specific sequences, producing predictable fragments of DNA. DNA fragments can be visualized through use of gel electrophoresis, which separates fragments according to their length.

The use of DNA ligase, ligation enzymes allows DNA fragments to be connected. By binding ("ligating") fragments of DNA together from different sources, researchers can create recombinant DNA, the DNA often associated with genetically modified organisms. Recombinant DNA is commonly used in the context of plasmids: short circular DNA molecules with a few genes on them. In the process known as molecular cloning, researchers can amplify the DNA fragments by inserting plasmids into bacteria and then culturing them on plates of agar (to isolate Cloning#Unicellular organisms, clones of bacteria cells). "Cloning" can also refer to the various means of creating cloned ("clonal") organisms.

DNA can also be amplified using a procedure called the

DNA can be manipulated in the laboratory. Restriction enzymes are commonly used enzymes that cut DNA at specific sequences, producing predictable fragments of DNA. DNA fragments can be visualized through use of gel electrophoresis, which separates fragments according to their length.

The use of DNA ligase, ligation enzymes allows DNA fragments to be connected. By binding ("ligating") fragments of DNA together from different sources, researchers can create recombinant DNA, the DNA often associated with genetically modified organisms. Recombinant DNA is commonly used in the context of plasmids: short circular DNA molecules with a few genes on them. In the process known as molecular cloning, researchers can amplify the DNA fragments by inserting plasmids into bacteria and then culturing them on plates of agar (to isolate Cloning#Unicellular organisms, clones of bacteria cells). "Cloning" can also refer to the various means of creating cloned ("clonal") organisms.

DNA can also be amplified using a procedure called the

gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

s, genetic variation

Genetic variation is the difference in DNA among individuals or the differences between populations. The multiple sources of genetic variation include mutation and genetic recombination. Mutations are the ultimate sources of genetic variation, ...

, and heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...

in organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

s.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

because heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...

is vital to organisms' evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

. Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, Augustinians, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thomas' Abbey in Br� ...

, a Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The me ...

n Augustinian Augustinian may refer to:

*Augustinians, members of religious orders following the Rule of St Augustine

*Augustinianism, the teachings of Augustine of Hippo and his intellectual heirs

*Someone who follows Augustine of Hippo

* Canons Regular of Sain ...

friar working in the 19th century in Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

, was the first to study genetics scientifically. Mendel studied "trait inheritance", patterns in the way traits are handed down from parents to offspring over time. He observed that organisms (pea plants) inherit traits by way of discrete "units of inheritance". This term, still used today, is a somewhat ambiguous definition of what is referred to as a gene.

Trait inheritance and molecular

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioche ...

inheritance mechanisms of genes are still primary principles of genetics in the 21st century, but modern genetics has expanded to study the function and behavior of genes. Gene structure and function, variation, and distribution are studied within the context of the cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery ...

, the organism (e.g. dominance), and within the context of a population. Genetics has given rise to a number of subfields, including molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a sub-field of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the ...

, epigenetics

In biology, epigenetics is the study of stable phenotypic changes (known as ''marks'') that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix '' epi-'' ( "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are "o ...

and population genetics

Population genetics is a subfield of genetics that deals with genetic differences within and between populations, and is a part of evolutionary biology. Studies in this branch of biology examine such phenomena as adaptation, speciation, and pop ...

. Organisms studied within the broad field span the domains of life (archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

, bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

, and eukarya

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

).

Genetic processes work in combination with an organism's environment and experiences to influence development and behavior

Behavior (American English) or behaviour (British English) is the range of actions and mannerisms made by individuals, organisms, systems or artificial entities in some environment. These systems can include other systems or organisms as wel ...

, often referred to as nature versus nurture

Nature versus nurture is a long-standing debate in biology and society about the balance between two competing factors which determine fate: genetics (nature) and environment (nurture). The alliterative expression "nature and nurture" in English h ...

. The intracellular

This glossary of biology terms is a list of definitions of fundamental terms and concepts used in biology, the study of life and of living organisms. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical definitions ...

or extracellular

This glossary of biology terms is a list of definitions of fundamental terms and concepts used in biology, the study of life and of living organisms. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical definitions ...

environment of a living cell or organism may switch gene transcription on or off. A classic example is two seeds of genetically identical corn, one placed in a temperate climate and one in an arid climate (lacking sufficient waterfall or rain). While the average height of the two corn stalks may be genetically determined to be equal, the one in the arid climate

The desert climate or arid climate (in the Köppen climate classification ''BWh'' and ''BWk''), is a dry climate sub-type in which there is a severe excess of evaporation over precipitation. The typically bald, rocky, or sandy surfaces in desert ...

only grows to half the height of the one in the temperate climate due to lack of water and nutrients in its environment.

We need to know a lot more about the biology of viruses because of genetic analysis. The virus's genome, which is made up of 11 double-stranded RNA segments, serves as its defining characteristic. The primary characteristic of viral genetics is the genome's segmented structure's ability to reassign genome segments during mixed infections

Etymology

The word ''genetics'' stems from theancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

' meaning "genitive"/"generative", which in turn derives from ' meaning "origin".

History

The observation that living things inherit traits from their parents has been used since prehistoric times to improve crop plants and animals throughselective breeding

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant mal ...

. The modern science of genetics, seeking to understand this process, began with the work of the Augustinian Augustinian may refer to:

*Augustinians, members of religious orders following the Rule of St Augustine

*Augustinianism, the teachings of Augustine of Hippo and his intellectual heirs

*Someone who follows Augustine of Hippo

* Canons Regular of Sain ...

friar Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, Augustinians, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thomas' Abbey in Br� ...

in the mid-19th century.

Prior to Mendel, Imre Festetics

Count Imre Festetics de Tolna (1764 – 1847) was a noble landowner and geneticist.

Scientific works

Many of the central principles the discipline of genetics were formulated by Imre Festetics through the study of sheep. Festetics formulated a nu ...

, a Hungarian noble, who lived in Kőszeg before Mendel, was the first who used the word "genetic" in hereditarian context. He described several rules of biological inheritance in his works ''The genetic laws of the Nature'' (Die genetischen Gesetze der Natur, 1819). His second law is the same as what Mendel published. In his third law, he developed the basic principles of mutation (he can be considered a forerunner of Hugo de Vries

Hugo Marie de Vries () (16 February 1848 – 21 May 1935) was a Dutch botanist and one of the first geneticists. He is known chiefly for suggesting the concept of genes, rediscovering the laws of heredity in the 1890s while apparently unaware of ...

). Festetics argued that changes observed in the generation of farm animals, plants, and humans are the result of scientific laws. Festetics empirically deduced that organisms inherit their characteristics, not acquire them. He recognized recessive traits and inherent variation by postulating that traits of past generations could reappear later, and organisms could produce progeny with different attributes. These observations represent an important prelude to Mendel’s theory of particulate inheritance insofar as it features a transition of heredity from its status as myth to that of a scientific discipline, by providing a fundamental theoretical basis for genetics in the twentieth century. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

's 1859 ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'', was blending inheritance

Blending may refer to:

* The process of mixing in process engineering

* Mixing paints to achieve a greater range of colors

* Blending (alcohol production), a technique to produce alcoholic beverages by mixing different brews

* Blending (linguist ...

: the idea that individuals inherit a smooth blend of traits from their parents. Mendel's work provided examples where traits were definitely not blended after hybridization, showing that traits are produced by combinations of distinct genes rather than a continuous blend. Blending of traits in the progeny is now explained by the action of multiple genes with quantitative effects. Another theory that had some support at that time was the inheritance of acquired characteristics

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

: the belief that individuals inherit traits strengthened by their parents. This theory (commonly associated with Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biologi ...

) is now known to be wrong—the experiences of individuals do not affect the genes they pass to their children. Other theories included Darwin's pangenesis

Pangenesis was Charles Darwin's hypothetical mechanism for heredity, in which he proposed that each part of the body continually emitted its own type of small organic particles called gemmules that aggregated in the gonads, contributing herita ...

(which had both acquired and inherited aspects) and Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton, FRS FRAI (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911), was an English Victorian era polymath: a statistician, sociologist, psychologist, anthropologist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto- ...

's reformulation of pangenesis as both particulate and inherited.

Mendelian genetics

Modern genetics started with Mendel's studies of the nature of inheritance in plants. In his paper "''Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden''" ("

Modern genetics started with Mendel's studies of the nature of inheritance in plants. In his paper "''Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden''" ("Experiments on Plant Hybridization

"Experiments on Plant Hybridization" (German: "Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden") is a seminal paper written in 1865 and published in 1866 by Gregor Mendel, an Augustinian friar considered to be the founder of modern genetics. The paper was the r ...

"), presented in 1865 to the ''Naturforschender Verein'' (Society for Research in Nature) in Brünn

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a Statutory city (Czech Republic), city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava (river), Svitava and Svratka (river), Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inha ...

, Mendel traced the inheritance patterns of certain traits in pea plants and described them mathematically. Although this pattern of inheritance could only be observed for a few traits, Mendel's work suggested that heredity was particulate, not acquired, and that the inheritance patterns of many traits could be explained through simple rules and ratios.

The importance of Mendel's work did not gain wide understanding until 1900, after his death, when Hugo de Vries

Hugo Marie de Vries () (16 February 1848 – 21 May 1935) was a Dutch botanist and one of the first geneticists. He is known chiefly for suggesting the concept of genes, rediscovering the laws of heredity in the 1890s while apparently unaware of ...

and other scientists rediscovered his research. William Bateson

William Bateson (8 August 1861 – 8 February 1926) was an English biologist who was the first person to use the term genetics to describe the study of heredity, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscove ...

, a proponent of Mendel's work, coined the word ''genetics'' in 1905. (The adjective ''genetic'', derived from the Greek word ''genesis''—γένεσις, "origin", predates the noun and was first used in a biological sense in 1860.) Bateson both acted as a mentor and was aided significantly by the work of other scientists from Newnham College at Cambridge, specifically the work of Becky Saunders, Nora Darwin Barlow

Emma Nora Barlow, Lady Barlow (née Darwin; 22 December 1885 – 29 May 1989), was a British botany, botanist and geneticist. The granddaughter of the United Kingdom, British natural history, naturalist Charles Darwin, Barlow began her academic ...

, and Muriel Wheldale Onslow

Muriel Wheldale Onslow (31 March 1880 – 19 May 1932) was a British biochemist, born in Birmingham, England. She studied the inheritance of flower colour in the common snapdragon Antirrhinum and the biochemistry of anthocyanin pigment molecules ...

. Bateson popularized the usage of the word ''genetics'' to describe the study of inheritance in his inaugural address to the Third International Conference on Plant Hybridization in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

in 1906. :Initially titled the "International Conference on Hybridisation and Plant Breeding", the title was changed as a result of Bateson's speech. See:

After the rediscovery of Mendel's work, scientists tried to determine which molecules in the cell were responsible for inheritance. In 1900, Nettie Stevens began studying the mealworm. Over the next 11 years, she discovered that females only had the X chromosome and males had both X and Y chromosomes. She was able to conclude that sex is a chromosomal factor and is determined by the male. In 1911, Thomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan (September 25, 1866 – December 4, 1945) was an American evolutionary biologist, geneticist, embryologist, and science author who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries elucidating the role tha ...

argued that genes are on chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

s, based on observations of a sex-linked white eye mutation in fruit flies

Fruit fly may refer to:

Organisms

* Drosophilidae, a family of small flies, including:

** ''Drosophila'', the genus of small fruit flies and vinegar flies

** ''Drosophila melanogaster'' or common fruit fly

** ''Drosophila suzukii'' or Asian fruit ...

. In 1913, his student Alfred Sturtevant

Alfred Henry Sturtevant (November 21, 1891 – April 5, 1970) was an American geneticist. Sturtevant constructed the first genetic map of a chromosome in 1911. Throughout his career he worked on the organism ''Drosophila melanogaster'' with ...

used the phenomenon of genetic linkage

Genetic linkage is the tendency of DNA sequences that are close together on a chromosome to be inherited together during the meiosis phase of sexual reproduction. Two genetic markers that are physically near to each other are unlikely to be separ ...

to show that genes are arranged linearly on the chromosome.

Molecular genetics

Although genes were known to exist on chromosomes, chromosomes are composed of both

Although genes were known to exist on chromosomes, chromosomes are composed of both protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

and DNA, and scientists did not know which of the two is responsible for inheritance. In 1928, Frederick Griffith

Frederick Griffith (1877–1941) was a British bacteriologist whose focus was the epidemiology and pathology of bacterial pneumonia. In January 1928 he reported what is now known as Griffith's Experiment, the first widely accepted demonstrati ...

discovered the phenomenon of transformation

Transformation may refer to:

Science and mathematics

In biology and medicine

* Metamorphosis, the biological process of changing physical form after birth or hatching

* Malignant transformation, the process of cells becoming cancerous

* Trans ...

: dead bacteria could transfer genetic material

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main cla ...

to "transform" other still-living bacteria. Sixteen years later, in 1944, the Avery–MacLeod–McCarty experiment

The Avery–MacLeod–McCarty experiment was an experimental demonstration, reported in 1944 by Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty, that DNA is the substance that causes bacterial transformation, in an era when it had been widely b ...

identified DNA as the molecule responsible for transformation. Reprint: The role of the nucleus as the repository of genetic information in eukaryotes had been established by Hämmerling in 1943 in his work on the single celled alga ''Acetabularia

''Acetabularia'' is a genus of green algae in the family Polyphysaceae, Typically found in subtropical waters, ''Acetabularia'' is a single-celled organism, but gigantic in size and complex in form, making it an excellent model organism for stu ...

''. The Hershey–Chase experiment

The Hershey–Chase experiments were a series of experiments conducted in 1952 by Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase that helped to confirm that DNA is genetic material.

While DNA had been known to biologists since 1869, many scientists still as ...

in 1952 confirmed that DNA (rather than protein) is the genetic material of the viruses that infect bacteria, providing further evidence that DNA is the molecule responsible for inheritance.

James Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper proposing the double helix structure of the DNA molecule. Watson, Crick and ...

and Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical struc ...

determined the structure of DNA in 1953, using the X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

work of Rosalind Franklin

Rosalind Elsie Franklin (25 July 192016 April 1958) was a British chemist and X-ray crystallographer whose work was central to the understanding of the molecular structures of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), RNA (ribonucleic acid), viruses, co ...

and Maurice Wilkins that indicated DNA has a helical

Helical may refer to:

* Helix, the mathematical concept for the shape

* Helical engine, a proposed spacecraft propulsion drive

* Helical spring, a coilspring

* Helical plc, a British property company, once a maker of steel bar stock

* Helicoil

A t ...

structure (i.e., shaped like a corkscrew). Their double-helix model had two strands of DNA with the nucleotides pointing inward, each matching a complementary nucleotide on the other strand to form what look like rungs on a twisted ladder. The a-helix is a secondary structure and the twisting in the a-helix is caused by hydrogen bonds between the carboxyl (C=O) and the amine H (N-H) constituents of the polypeptide backbone. This structure showed that genetic information exists in the sequence of nucleotides on each strand of DNA. The structure also suggested a simple method for replication: if the strands are separated, new partner strands can be reconstructed for each based on the sequence of the old strand. This property is what gives DNA its semi-conservative nature where one strand of new DNA is from an original parent strand.

Although the structure of DNA showed how inheritance works, it was still not known how DNA influences the behavior of cells. In the following years, scientists tried to understand how DNA controls the process of protein production

Protein production is the biotechnological process of generating a specific protein. It is typically achieved by the manipulation of gene expression in an organism such that it expresses large amounts of a recombinant gene. This includes the tran ...

. It was discovered that the cell uses DNA as a template to create matching messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the p ...

, molecules with nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules wi ...

s very similar to DNA. The nucleotide sequence of a messenger RNA is used to create an amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

sequence in protein; this translation between nucleotide sequences and amino acid sequences is known as the genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

.

With the newfound molecular understanding of inheritance came an explosion of research. A notable theory arose from Tomoko Ohta

Tomoko (ともこ, トモコ) is a female Japanese given name.

Like many Japanese names, Tomoko can be written using different kanji characters and can mean:

* 友子 - "friendly child"

* 知子 - "knowing child"

* 智子 - "wise child"

* 朋子 ...

in 1973 with her amendment to the neutral theory of molecular evolution

The neutral theory of molecular evolution holds that most evolutionary changes occur at the molecular level, and most of the variation within and between species are due to random genetic drift of mutant alleles that are selectively neutral. The ...

through publishing the nearly neutral theory of molecular evolution

The nearly neutral theory of molecular evolution is a modification of the neutral theory of molecular evolution that accounts for the fact that not all mutations are either so deleterious such that they can be ignored, or else neutral. Slightly del ...

. In this theory, Ohta stressed the importance of natural selection and the environment to the rate at which genetic evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

occurs. One important development was chain-termination DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

in 1977 by Frederick Sanger

Frederick Sanger (; 13 August 1918 – 19 November 2013) was an English biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice.

He won the 1958 Chemistry Prize for determining the amino acid sequence of insulin and numerous other p ...

. This technology allows scientists to read the nucleotide sequence of a DNA molecule. In 1983, Kary Banks Mullis

Kary Banks Mullis (December 28, 1944August 7, 2019) was an American biochemist. In recognition of his role in the invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique, he shared the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Michael Smith and was ...

developed the polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to rapidly make millions to billions of copies (complete or partial) of a specific DNA sample, allowing scientists to take a very small sample of DNA and amplify it (or a part of it) t ...

, providing a quick way to isolate and amplify a specific section of DNA from a mixture. The efforts of the Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both a ...

, Department of Energy, NIH, and parallel private efforts by Celera Genomics

Celera is a subsidiary of Quest Diagnostics which focuses on genetic sequencing and related technologies. It was founded in 1998 as a business unit of Applera, spun off into an independent company in 2008, and finally acquired by Quest Diagnostic ...

led to the sequencing of the human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as DNA within the 23 chromosome pairs in cell nuclei and in a small DNA molecule found within individual mitochondria. These are usually treated separately as the n ...

in 2003.

Features of inheritance

Discrete inheritance and Mendel's laws

gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

s, from parents to offspring. This property was first observed by Gregor Mendel, who studied the segregation of heritable traits in pea

The pea is most commonly the small spherical seed or the seed-pod of the flowering plant species ''Pisum sativum''. Each pod contains several peas, which can be green or yellow. Botanically, pea pods are fruit, since they contain seeds and d ...

plants, showing for example that flowers on a single plant were either purple or white—but never an intermediate between the two colors. The discrete versions of the same gene controlling the inherited appearance (phenotypes) are called allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

s.

In the case of the pea, which is a diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

species, each individual plant has two copies of each gene, one copy inherited from each parent. Many species, including humans, have this pattern of inheritance. Diploid organisms with two copies of the same allele of a given gene are called homozygous

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mo ...

at that gene locus

In genetics, a locus (plural loci) is a specific, fixed position on a chromosome where a particular gene or genetic marker is located. Each chromosome carries many genes, with each gene occupying a different position or locus; in humans, the total ...

, while organisms with two different alleles of a given gene are called heterozygous

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mo ...

. The set of alleles for a given organism is called its genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

, while the observable traits of the organism are called its phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

. When organisms are heterozygous at a gene, often one allele is called dominant as its qualities dominate the phenotype of the organism, while the other allele is called recessive

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and t ...

as its qualities recede and are not observed. Some alleles do not have complete dominance and instead have incomplete dominance

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and ...

by expressing an intermediate phenotype, or codominance

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and t ...

by expressing both alleles at once.

When a pair of organisms reproduce sexually

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote tha ...

, their offspring randomly inherit one of the two alleles from each parent. These observations of discrete inheritance and the segregation of alleles are collectively known as Mendel's first law or the Law of Segregation. However, the probability of getting one gene over the other can change due to dominant, recessive, homozygous, or heterozygous genes. For example, Mendel found that if you cross homozygous dominate trait and homozygous recessive trait your odds of getting the dominant trait is 3:1. Real geneticist study and calculate probabilities by using theoretical probabilities, empirical probabilities, the product rule, the sum rule, and more.

Notation and diagrams

pedigree chart

A pedigree chart is a diagram that shows the occurrence and appearance of phenotypes of a particular gene or organism and its ancestors from one generation to the next, most commonly humans, show dogs, and race horses.

Definition

The word pedigree ...

s to represent the inheritance of traits. These charts map the inheritance of a trait in a family tree.

Multiple gene interactions

Organisms have thousands of genes, and in sexually reproducing organisms these genes generally assort independently of each other. This means that the inheritance of an allele for yellow or green pea color is unrelated to the inheritance of alleles for white or purple flowers. This phenomenon, known as " Mendel's second law" or the "law of independent assortment," means that the alleles of different genes get shuffled between parents to form offspring with many different combinations. Different genes often interact to influence the same trait. In the Blue-eyed Mary (''Omphalodes verna''), for example, there exists a gene with alleles that determine the color of flowers: blue or magenta. Another gene, however, controls whether the flowers have color at all or are white. When a plant has two copies of this white allele, its flowers are white—regardless of whether the first gene has blue or magenta alleles. This interaction between genes is called

Organisms have thousands of genes, and in sexually reproducing organisms these genes generally assort independently of each other. This means that the inheritance of an allele for yellow or green pea color is unrelated to the inheritance of alleles for white or purple flowers. This phenomenon, known as " Mendel's second law" or the "law of independent assortment," means that the alleles of different genes get shuffled between parents to form offspring with many different combinations. Different genes often interact to influence the same trait. In the Blue-eyed Mary (''Omphalodes verna''), for example, there exists a gene with alleles that determine the color of flowers: blue or magenta. Another gene, however, controls whether the flowers have color at all or are white. When a plant has two copies of this white allele, its flowers are white—regardless of whether the first gene has blue or magenta alleles. This interaction between genes is called epistasis

Epistasis is a phenomenon in genetics in which the effect of a gene mutation is dependent on the presence or absence of mutations in one or more other genes, respectively termed modifier genes. In other words, the effect of the mutation is dep ...

, with the second gene epistatic to the first.

Many traits are not discrete features (e.g. purple or white flowers) but are instead continuous features (e.g. human height and skin color

Human skin color ranges from the darkest brown to the lightest hues. Differences in skin color among individuals is caused by variation in pigmentation, which is the result of genetics (inherited from one's biological parents and or individu ...

). These complex traits

Complex traits, also known as quantitative traits, are traits that do not behave according to simple Mendelian inheritance laws. More specifically, their inheritance cannot be explained by the genetic segregation of a single gene. Such traits show ...

are products of many genes. The influence of these genes is mediated, to varying degrees, by the environment an organism has experienced. The degree to which an organism's genes contribute to a complex trait is called heritability

Heritability is a statistic used in the fields of breeding and genetics that estimates the degree of ''variation'' in a phenotypic trait in a population that is due to genetic variation between individuals in that population. The concept of h ...

. Measurement of the heritability of a trait is relative—in a more variable environment, the environment has a bigger influence on the total variation of the trait. For example, human height is a trait with complex causes. It has a heritability of 89% in the United States. In Nigeria, however, where people experience a more variable access to good nutrition and health care

Health care or healthcare is the improvement of health via the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other physical and mental impairments in people. Health care is delivered by health profe ...

, height has a heritability of only 62%.

Molecular basis for inheritance

DNA and chromosomes

The

The molecular

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioche ...

basis for genes is deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). DNA is composed of deoxyribose

Deoxyribose, or more precisely 2-deoxyribose, is a monosaccharide with idealized formula H−(C=O)−(CH2)−(CHOH)3−H. Its name indicates that it is a deoxy sugar, meaning that it is derived from the sugar ribose by loss of a hydroxy group. D ...

(sugar molecule), a phosphate group, and a base (amine group). There are four types of bases: adenine

Adenine () ( symbol A or Ade) is a nucleobase (a purine derivative). It is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The three others are guanine, cytosine and thymine. Its derivati ...

(A), cytosine

Cytosine () ( symbol C or Cyt) is one of the four nucleobases found in DNA and RNA, along with adenine, guanine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). It is a pyrimidine derivative, with a heterocyclic aromatic ring and two substituents attached (an am ...

(C), guanine

Guanine () ( symbol G or Gua) is one of the four main nucleobases found in the nucleic acids DNA and RNA, the others being adenine, cytosine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). In DNA, guanine is paired with cytosine. The guanine nucleoside is called ...

(G), and thymine

Thymine () ( symbol T or Thy) is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The others are adenine, guanine, and cytosine. Thymine is also known as 5-methyluracil, a pyrimidine nu ...

(T). The phosphates make hydrogen bonds with the sugars to make long phosphate-sugar backbones. Bases specifically pair together (T&A, C&G) between two backbones and make like rungs on a ladder. The bases, phosphates, and sugars together make a nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules wi ...

that connects to make long chains of DNA. Genetic information exists in the sequence of these nucleotides, and genes exist as stretches of sequence along the DNA chain. These chains coil into a double a-helix structure and wrap around proteins called Histones

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes in turn ar ...

which provide the structural support. DNA wrapped around these histones are called chromosomes. Virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es sometimes use the similar molecule RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

instead of DNA as their genetic material.

DNA normally exists as a double-stranded molecule, coiled into the shape of a double helix

A double is a look-alike or doppelgänger; one person or being that resembles another.

Double, The Double or Dubble may also refer to:

Film and television

* Double (filmmaking), someone who substitutes for the credited actor of a character

* ...

. Each nucleotide in DNA preferentially pairs with its partner nucleotide on the opposite strand: A pairs with T, and C pairs with G. Thus, in its two-stranded form, each strand effectively contains all necessary information, redundant with its partner strand. This structure of DNA is the physical basis for inheritance: DNA replication duplicates the genetic information by splitting the strands and using each strand as a template for synthesis of a new partner strand.

Genes are arranged linearly along long chains of DNA base-pair sequences. In

Genes are arranged linearly along long chains of DNA base-pair sequences. In bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

, each cell usually contains a single circular genophore

The nucleoid (meaning ''nucleus-like'') is an irregularly shaped region within the prokaryotic cell that contains all or most of the genetic material. The chromosome of a prokaryote is circular, and its length is very large compared to the cell d ...

, while eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

organisms (such as plants and animals) have their DNA arranged in multiple linear chromosomes. These DNA strands are often extremely long; the largest human chromosome, for example, is about 247 million base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s in length. The DNA of a chromosome is associated with structural proteins that organize, compact, and control access to the DNA, forming a material called chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important roles in r ...

; in eukaryotes, chromatin is usually composed of nucleosome

A nucleosome is the basic structural unit of DNA packaging in eukaryotes. The structure of a nucleosome consists of a segment of DNA wound around eight histone proteins and resembles thread wrapped around a spool. The nucleosome is the fundamen ...

s, segments of DNA wound around cores of histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes in turn a ...

proteins. The full set of hereditary material in an organism (usually the combined DNA sequences of all chromosomes) is called the genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

.

DNA is most often found in the nucleus of cells, but Ruth Sager helped in the discovery of nonchromosomal genes found outside of the nucleus. In plants, these are often found in the chloroplasts and in other organisms, in the mitochondria. These nonchromosomal genes can still be passed on by either partner in sexual reproduction and they control a variety of hereditary characteristics that replicate and remain active throughout generations.

While haploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

organisms have only one copy of each chromosome, most animals and many plants are diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

, containing two of each chromosome and thus two copies of every gene. The two alleles for a gene are located on identical loci of the two homologous chromosomes

A couple of homologous chromosomes, or homologs, are a set of one maternal and one paternal chromosome that pair up with each other inside a cell during fertilization. Homologs have the same genes in the same loci where they provide points alon ...

, each allele inherited from a different parent.

Many species have so-called

Many species have so-called sex chromosome

A sex chromosome (also referred to as an allosome, heterotypical chromosome, gonosome, heterochromosome, or idiochromosome) is a chromosome that differs from an ordinary autosome in form, size, and behavior. The human sex chromosomes, a typical ...

s that determine the sex of each organism. In humans and many other animals, the Y chromosome

The Y chromosome is one of two sex chromosomes (allosomes) in therian mammals, including humans, and many other animals. The other is the X chromosome. Y is normally the sex-determining chromosome in many species, since it is the presence or abse ...

contains the gene that triggers the development of the specifically male characteristics. In evolution, this chromosome has lost most of its content and also most of its genes, while the X chromosome

The X chromosome is one of the two sex-determining chromosomes (allosomes) in many organisms, including mammals (the other is the Y chromosome), and is found in both males and females. It is a part of the XY sex-determination system and XO sex-d ...

is similar to the other chromosomes and contains many genes. This being said, Mary Frances Lyon discovered that there is X-chromosome inactivation during reproduction to avoid passing on twice as many genes to the offspring. Lyon's discovery led to the discovery of X-linked diseases.

Reproduction

When cells divide, their full genome is copied and eachdaughter cell

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukaryotes, there are ...

inherits one copy. This process, called mitosis

In cell biology, mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is mainta ...

, is the simplest form of reproduction and is the basis for asexual reproduction. Asexual reproduction can also occur in multicellular organisms, producing offspring that inherit their genome from a single parent. Offspring that are genetically identical to their parents are called clones

Clone or Clones or Cloning or Cloned or The Clone may refer to:

Places

* Clones, County Fermanagh

* Clones, County Monaghan, a town in Ireland

Biology

* Clone (B-cell), a lymphocyte clone, the massive presence of which may indicate a pathologi ...

.

Eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

organisms often use sexual reproduction to generate offspring that contain a mixture of genetic material inherited from two different parents. The process of sexual reproduction alternates between forms that contain single copies of the genome (haploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

) and double copies (diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

). Haploid cells fuse and combine genetic material to create a diploid cell with paired chromosomes. Diploid organisms form haploids by dividing, without replicating their DNA, to create daughter cells that randomly inherit one of each pair of chromosomes. Most animals and many plants are diploid for most of their lifespan, with the haploid form reduced to single cell gamete

A gamete (; , ultimately ) is a haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as sex cells. In species that produce t ...

s such as sperm

Sperm is the male reproductive cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm with a tail known as a flagellum, whi ...

or eggs

Humans and human ancestors have scavenged and eaten animal eggs for millions of years. Humans in Southeast Asia had domesticated chickens and harvested their eggs for food by 1,500 BCE. The most widely consumed eggs are those of fowl, especial ...

.

Although they do not use the haploid/diploid method of sexual reproduction, bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

have many methods of acquiring new genetic information. Some bacteria can undergo conjugation

Conjugation or conjugate may refer to:

Linguistics

* Grammatical conjugation, the modification of a verb from its basic form

* Emotive conjugation or Russell's conjugation, the use of loaded language

Mathematics

* Complex conjugation, the chang ...

, transferring a small circular piece of DNA to another bacterium. Bacteria can also take up raw DNA fragments found in the environment and integrate them into their genomes, a phenomenon known as transformation

Transformation may refer to:

Science and mathematics

In biology and medicine

* Metamorphosis, the biological process of changing physical form after birth or hatching

* Malignant transformation, the process of cells becoming cancerous

* Trans ...

. These processes result in horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between Unicellular organism, unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offsprin ...

, transmitting fragments of genetic information between organisms that would be otherwise unrelated. Natural bacterial transformation occurs in many bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

l species, and can be regarded as a sexual process for transferring DNA from one cell to another cell (usually of the same species). Transformation requires the action of numerous bacterial gene product

A gene product is the biochemical material, either RNA or protein, resulting from expression of a gene. A measurement of the amount of gene product is sometimes used to infer how active a gene is. Abnormal amounts of gene product can be correlated ...

s, and its primary adaptive function appears to be repair

The technical meaning of maintenance involves functional checks, servicing, repairing or replacing of necessary devices, equipment, machinery, building infrastructure, and supporting utilities in industrial, business, and residential installa ...

of DNA damages in the recipient cell.

Recombination and genetic linkage

The diploid nature of chromosomes allows for genes on different chromosomes to assort independently or be separated from their homologous pair during sexual reproduction wherein haploid gametes are formed. In this way new combinations of genes can occur in the offspring of a mating pair. Genes on the same chromosome would theoretically never recombine. However, they do, via the cellular process of

The diploid nature of chromosomes allows for genes on different chromosomes to assort independently or be separated from their homologous pair during sexual reproduction wherein haploid gametes are formed. In this way new combinations of genes can occur in the offspring of a mating pair. Genes on the same chromosome would theoretically never recombine. However, they do, via the cellular process of chromosomal crossover

Chromosomal crossover, or crossing over, is the exchange of genetic material during sexual reproduction between two homologous chromosomes' non-sister chromatids that results in recombinant chromosomes. It is one of the final phases of geneti ...

. During crossover, chromosomes exchange stretches of DNA, effectively shuffling the gene alleles between the chromosomes. This process of chromosomal crossover generally occurs during meiosis

Meiosis (; , since it is a reductional division) is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, such as sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately resu ...

, a series of cell divisions that creates haploid cells. Meiotic recombination

Genetic recombination (also known as genetic reshuffling) is the exchange of genetic material between different organisms which leads to production of offspring with combinations of traits that differ from those found in either parent. In eukaryo ...

, particularly in microbial eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s, appears to serve the adaptive function of repair of DNA damages.

The first cytological demonstration of crossing over was performed by Harriet Creighton and Barbara McClintock

Barbara McClintock (June 16, 1902 – September 2, 1992) was an American scientist and cytogeneticist who was awarded the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. McClintock received her PhD in botany from Cornell University in 1927. There s ...

in 1931. Their research and experiments on corn provided cytological evidence for the genetic theory that linked genes on paired chromosomes do in fact exchange places from one homolog to the other.

The probability of chromosomal crossover occurring between two given points on the chromosome is related to the distance between the points. For an arbitrarily long distance, the probability of crossover is high enough that the inheritance of the genes is effectively uncorrelated. For genes that are closer together, however, the lower probability of crossover means that the genes demonstrate genetic linkage; alleles for the two genes tend to be inherited together. The amounts of linkage between a series of genes can be combined to form a linear linkage map that roughly describes the arrangement of the genes along the chromosome.

Gene expression

Genetic code

amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s. The DNA sequence of a gene is used to produce a specific amino acid sequence

Protein primary structure is the linear sequence of amino acids in a peptide or protein. By convention, the primary structure of a protein is reported starting from the amino-terminal (N) end to the carboxyl-terminal (C) end. Protein biosynthe ...

. This process begins with the production of an RNA molecule with a sequence matching the gene's DNA sequence, a process called transcription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

.

This messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the p ...

molecule then serves to produce a corresponding amino acid sequence through a process called translation

Translation is the communication of the Meaning (linguistic), meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The ...

. Each group of three nucleotides in the sequence, called a codon

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

, corresponds either to one of the twenty possible amino acids in a protein or an instruction to end the amino acid sequence; this correspondence is called the genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

. The flow of information is unidirectional: information is transferred from nucleotide sequences into the amino acid sequence of proteins, but it never transfers from protein back into the sequence of DNA—a phenomenon Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical struc ...

called the central dogma of molecular biology

The central dogma of molecular biology is an explanation of the flow of genetic information within a biological system. It is often stated as "DNA makes RNA, and RNA makes protein", although this is not its original meaning. It was first stated by ...

.

The specific sequence of amino acids results

A result is the outcome of an event.

Result or Results may also refer to: Music

* Results (album), ''Results'' (album), a 1989 album by Liza Minnelli

* ''Results'', a 2012 album by Murder Construct

* "The Result", a single by The Upsetters

* "The ...

in a unique three-dimensional structure for that protein, and the three-dimensional structures of proteins are related to their functions. Some are simple structural molecules, like the fibers formed by the protein collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix found in the body's various connective tissues. As the main component of connective tissue, it is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up from 25% to 35% of the whole ...

. Proteins can bind to other proteins and simple molecules, sometimes acting as enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s by facilitating chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the IUPAC nomenclature for organic transformations, chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the pos ...

s within the bound molecules (without changing the structure of the protein itself). Protein structure is dynamic; the protein hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

bends into slightly different forms as it facilitates the capture, transport, and release of oxygen molecules within mammalian blood.

A single nucleotide difference within DNA can cause a change in the amino acid sequence of a protein. Because protein structures are the result of their amino acid sequences, some changes can dramatically change the properties of a protein by destabilizing the structure or changing the surface of the protein in a way that changes its interaction with other proteins and molecules. For example, sickle-cell anemia

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of blood disorders typically inherited from a person's parents. The most common type is known as sickle cell anaemia. It results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin found in red bl ...

is a human genetic disease

A genetic disorder is a health problem caused by one or more abnormalities in the genome. It can be caused by a mutation in a single gene (monogenic) or multiple genes (polygenic) or by a chromosomal abnormality. Although polygenic disorders ...

that results from a single base difference within the coding region

The coding region of a gene, also known as the coding sequence (CDS), is the portion of a gene's DNA or RNA that codes for protein. Studying the length, composition, regulation, splicing, structures, and functions of coding regions compared to no ...

for the β-globin section of hemoglobin, causing a single amino acid change that changes hemoglobin's physical properties.

Sickle-cell versions of hemoglobin stick to themselves, stacking to form fibers that distort the shape of red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "holl ...

s carrying the protein. These sickle-shaped cells no longer flow smoothly through blood vessel

The blood vessels are the components of the circulatory system that transport blood throughout the human body. These vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to the tissues of the body. They also take waste and carbon dioxide away ...

s, having a tendency to clog or degrade, causing the medical problems associated with this disease.

Some DNA sequences are transcribed into RNA but are not translated into protein products—such RNA molecules are called non-coding RNA

A non-coding RNA (ncRNA) is a functional RNA molecule that is not Translation (genetics), translated into a protein. The DNA sequence from which a functional non-coding RNA is transcribed is often called an RNA gene. Abundant and functionally im ...

. In some cases, these products fold into structures which are involved in critical cell functions (e.g. ribosomal RNA