General Motors streetcar conspiracy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The General Motors streetcar conspiracy refers to the convictions of

By 1930, most streetcar systems were aging and losing money. Service to the public was suffering; the

By 1930, most streetcar systems were aging and losing money. Service to the public was suffering; the

"The Great GM Conspiracy Legend: GM and the Red Cars", Stan Schwarz

* ttp://www.newday.com/films/Taken_for_a_Ride.html "Taken for a Ride", Jim Klein and Martha Olson – a 55-minute film first shown on PBS in August 1996br>United States v. National City Lines, Inc.'', 186 F.2d 562 (1951)

{{Pacific Electric Railway Streetcars in the United States Corporate crime

General Motors

The General Motors Company (GM) is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. It is the largest automaker in the United States and ...

(GM) and related companies that were involved in the monopolizing of the sale of buses and supplies to National City Lines

National City Lines, Inc. (NCL) was a public transportation company. The company grew out of the Fitzgerald brothers' bus operations, founded in Minnesota, United States in 1920 as a modest local transport company operating two buses. Part of the ...

(NCL) and subsidiaries, as well as to the allegations that the defendants conspired to own or control transit systems, in violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Antitrust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (, ) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce. It was passed by Congress and is named for Senator John Sherman, its principal author.

Th ...

. This suit created lingering suspicions that the defendants had in fact plotted to dismantle streetcar

A tram (called a streetcar or trolley in North America) is a rail vehicle that travels on tramway tracks on public urban streets; some include segments on segregated right-of-way. The tramlines or networks operated as public transport are ...

systems in many cities in the United States as an attempt to monopolize surface transportation.

Between 1938 and 1950, National City Lines and its subsidiaries, American City Lines and Pacific City Lines

Pacific City Lines was a company formed in 1937 as a subsidiary to National City Lines in Oakland, California. Its function was to purchase streetcar systems in the western United States as part of what became known as the Great American streetcar ...

—with investment from GM, Firestone Tire

Firestone Tire and Rubber Company is a tire company founded by Harvey Firestone (1868–1938) in 1900 initially to supply solid rubber side-wire tires for fire apparatus, and later, pneumatic tires for wagons, buggies, and other forms of wheele ...

, Standard Oil of California (through a subsidiary), Federal Engineering, Phillips Petroleum

Phillips Petroleum Company was an American oil company incorporated in 1917 that expanded into petroleum refining, marketing and transportation, natural gas gathering and the chemicals sectors. It was Phillips Petroleum that first found oil in the ...

, and Mack Trucks

Mack Trucks, Inc., is an American truck manufacturing company and a former manufacturer of buses and trolley buses. Founded in 1900 as the Mack Brothers Company, it manufactured its first truck in 1905 and adopted its present name in 1922. Mack ...

—gained control of additional transit systems in about 25 cities. Systems included St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

, and Oakland

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third largest city overall in the Bay A ...

. NCL often converted streetcars to bus

A bus (contracted from omnibus, with variants multibus, motorbus, autobus, etc.) is a road vehicle that carries significantly more passengers than an average car or van. It is most commonly used in public transport, but is also in use for cha ...

operations in that period, although electric traction was preserved or expanded in some locations. Other systems, such as San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the List of United States cities by population, eigh ...

's, were converted by outgrowths of the City Lines. Most of the companies involved were convicted in 1949 of conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, is a secret plan or agreement between persons (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder or treason, especially with political motivation, while keeping their agree ...

to monopolize

In United States antitrust law, monopolization is illegal monopoly behavior. The main categories of prohibited behavior include exclusive dealing, price discrimination, refusing to supply an essential facility, product tying and predatory pricing. ...

interstate commerce in the sale of buses, fuel, and supplies to NCL subsidiaries, but were acquitted of conspiring to monopolize the transit industry.

The story as an urban legend has been written about by Martha Bianco, Scott Bottles, Sy Adler, Jonathan Richmond, Cliff Slater and Robert Post. It has been explored several times in print, film, and other media, notably in the fictional film ''Who Framed Roger Rabbit

''Who Framed Roger Rabbit'' is a 1988 American live-action/animated comedy mystery film directed by Robert Zemeckis, produced by Frank Marshall and Robert Watts, and loosely adapted by Jeffrey Price and Peter S. Seaman from Gary K. Wolf's 1 ...

'', documentary films such as '' Taken for a Ride'' and '' The End of Suburbia'' and the book ''Internal Combustion''.

Only a handful of U.S. cities, including San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Newark

Newark most commonly refers to:

* Newark, New Jersey, city in the United States

* Newark Liberty International Airport, New Jersey; a major air hub in the New York metropolitan area

Newark may also refer to:

Places Canada

* Niagara-on-the ...

, Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, and Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, have surviving legacy rail urban transport systems based on streetcars, although their systems are significantly smaller than they once were. Other cities are re-introducing streetcars. In some cases, the streetcars do not actually ride on the street. Boston had all of its downtown lines elevated or buried by the mid-1920s, and most of the surviving lines at grade operate on their own right of way. However, San Francisco's and Philadelphia's lines do have large portions of the route that ride on the street as well as using tunnels.

History

Background

In the latter half of the 19th century, transit systems were generally rail, first horse-drawn streetcars, and later electric powered streetcars and cable cars. Rail was more comfortable and had lessrolling resistance

Rolling resistance, sometimes called rolling friction or rolling drag, is the force resisting the motion when a body (such as a ball, tire, or wheel) rolls on a surface. It is mainly caused by non-elastic effects; that is, not all the energy nee ...

than street traffic on granite block or macadam

Macadam is a type of road construction, pioneered by Scottish engineer John Loudon McAdam around 1820, in which crushed stone is placed in shallow, convex layers and compacted thoroughly. A binding layer of stone dust (crushed stone from the o ...

and horse-drawn streetcars were generally a step up from the horsebus

A horse-bus or horse-drawn omnibus was a large, enclosed, and sprung horse-drawn vehicle used for passenger transport before the introduction of motor vehicles. It was mainly used in the late 19th century in both the United States and Europe, a ...

. Electric traction was faster, more sanitary, and cheaper to run; with the cost, excreta, epizootic

In epizoology, an epizootic (from Greek: ''epi-'' upon + ''zoon'' animal) is a disease event in a nonhuman animal population analogous to an epidemic in humans. An epizootic may be restricted to a specific locale (an "outbreak"), general (an "epi ...

risk, and carcass disposal of horses eliminated entirely. Streetcars were later seen as obstructions to traffic, but for nearly 20 years they had the highest power-to-weight ratio

Power-to-weight ratio (PWR, also called specific power, or power-to-mass ratio) is a calculation commonly applied to engines and mobile power sources to enable the comparison of one unit or design to another. Power-to-weight ratio is a measuremen ...

of anything commonly found on the road, and the lowest rolling resistance.

Streetcars paid ordinary business and property taxes, but also generally paid franchise fees, maintained at least the shared right-of-way, and provided street sweeping and snow clearance. They were also required to maintain minimal service levels. Many franchise fees were fixed or based on gross (v. net); such arrangements, when combined with fixed fares, created gradual impossible financial pressures. Early electric cars generally had a two-man crew, a holdover from horsecar

A horsecar, horse-drawn tram, horse-drawn streetcar (U.S.), or horse-drawn railway (historical), is an animal-powered (usually horse) tram or streetcar.

Summary

The horse-drawn tram (horsecar) was an early form of public rail transport, wh ...

days, which created financial problems in later years as salaries outpaced revenues.

Many electric lines—especially in the West—were tied into other real estate or transportation enterprises. The Pacific Electric

The Pacific Electric Railway Company, nicknamed the Red Cars, was a privately owned mass transit system in Southern California consisting of electrically powered streetcars, interurban cars, and buses and was the largest electric railway system ...

and the Los Angeles Railway

The Los Angeles Railway (also known as Yellow Cars, LARy and later Los Angeles Transit Lines) was a system of streetcars that operated in Central Los Angeles and surrounding neighborhoods between 1895 and 1963. The system provided frequent loc ...

were especially so, in essence loss leader

A loss leader (also leader) is a pricing strategy where a product is sold at a price below its market cost to stimulate other sales of more profitable goods or services. With this sales promotion/marketing strategy, a "leader" is any popular articl ...

s for property development and long haul shipping.

By 1918, half of US streetcar mileage was in bankruptcy.

Early years

John D. Hertz

John Daniel Hertz, Sr. (April 10, 1879October 8, 1961) was an American businessman, thoroughbred racehorse owner and breeder, and philanthropist.

Biography

Born Sándor Herz to a Jewish family in Szklabinya, Austria-Hungary (today Sklabiňa, a ...

, better remembered for his car rental business, was also an early motorbus manufacturer and operator. In 1917 he founded the Chicago Motor Coach Company, which operated buses in Chicago, and in 1923, he founded the Yellow Coach Manufacturing Company

The Yellow Coach Manufacturing Company (informally Yellow Coach) was an early manufacturer of passenger buses in the United States. Between 1923 and 1943, Yellow Coach built transit buses, electric-powered trolley buses, and parlor coaches.

Fou ...

, a manufacturer of buses. He then formed The Omnibus Corporation The Omnibus Corporation (also Omnibus Corporation of America) is an American bus company that was formed in 1924 and acquired control of Fifth Avenue Coach Company and the Chicago Motor Coach Company with John D. Hertz as chairman. In 1953, it purch ...

in 1926 with "plans embracing the extension of motor coach operation to urban and rural communities in every part of the United States" that then purchased the Fifth Avenue Coach Company

The Fifth Avenue Coach Company was a bus operator in Manhattan, The Bronx, Queens, and Westchester County, New York, providing public transit between 1896 and 1954 after which services were taken over by the New York City Omnibus Corporation. ...

in New York. The same year, the Fifth Avenue Coach Company acquired a majority of the stock in the struggling New York Railways Corporation

The New York Railways Corporation was a railway company that operated street railways in Manhattan, New York City, United States between 1925 and 1936. During 1935/1936 it converted its remaining lines to bus routes which were operated by the New ...

(which had been bankrupted and reorganized at least twice). In 1927, General Motors acquired a controlling share of the Yellow Coach Manufacturing Company and appointed Hertz as a main board director. Hertz's bus lines, however, were not in direct competition with any streetcars, and his core business was the higher-priced "motor coach".

By 1930, most streetcar systems were aging and losing money. Service to the public was suffering; the

By 1930, most streetcar systems were aging and losing money. Service to the public was suffering; the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

compounded this. Yellow Coach tried to persuade transit companies to replace streetcars with buses, but could not persuade the power companies that owned the streetcar operations to motorize. GM decided to form a new subsidiary—United Cities Motor Transport (UCMT)—to finance the conversion of streetcar systems to buses in small cities. The new subsidiary made investments in small transit systems in Kalamazoo

Kalamazoo ( ) is a city in the southwest region of the U.S. state of Michigan. It is the county seat of Kalamazoo County. At the 2010 census, Kalamazoo had a population of 74,262. Kalamazoo is the major city of the Kalamazoo-Portage Metropolit ...

and Saginaw, Michigan

Saginaw () is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan and the seat of Saginaw County. The city of Saginaw and Saginaw County are both in the area known as Mid-Michigan. Saginaw is adjacent to Saginaw Charter Township and considered part of Greater ...

, and in Springfield, Ohio

Springfield is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Clark County, Ohio, Clark County. The municipality is located in southwestern Ohio and is situated on the Mad River (Ohio), Mad River, Buck Creek, and Beaver Creek, approxim ...

, where they were successful in conversion to buses. UCMT then approached the Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous co ...

, system with a similar proposal. It was censured by the American Transit Association and dissolved in 1935.

The New York Railways Corporation

The New York Railways Corporation was a railway company that operated street railways in Manhattan, New York City, United States between 1925 and 1936. During 1935/1936 it converted its remaining lines to bus routes which were operated by the New ...

began conversion to buses in 1935, with the new bus services being operated by the New York City Omnibus Corporation

The New York City Omnibus Corporation (NYCO, later Fifth Avenue Coach Lines, Inc.) ran bus services in New York City between 1926 and 1962. It expanded in 1935/36 with new bus routes to replace the New York Railways Corporation streetcars when ...

, which shared management with The Omnibus Corporation. During this period GM worked with Public Service Transportation in New Jersey to develop the "All-Service Vehicle", a bus also capable of working as a trackless trolley, allowing off-wire passenger collection in areas too lightly populated to pay for wire infrastructure.

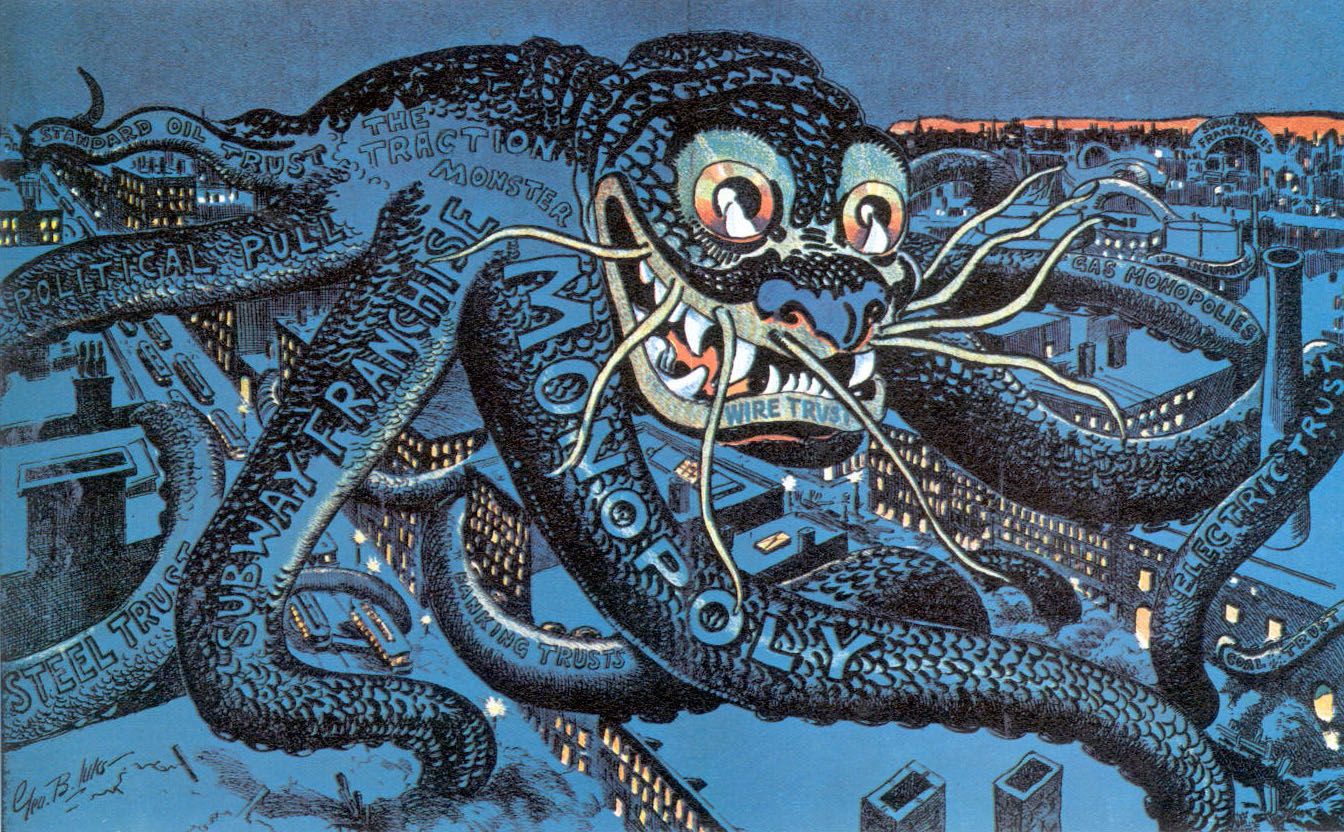

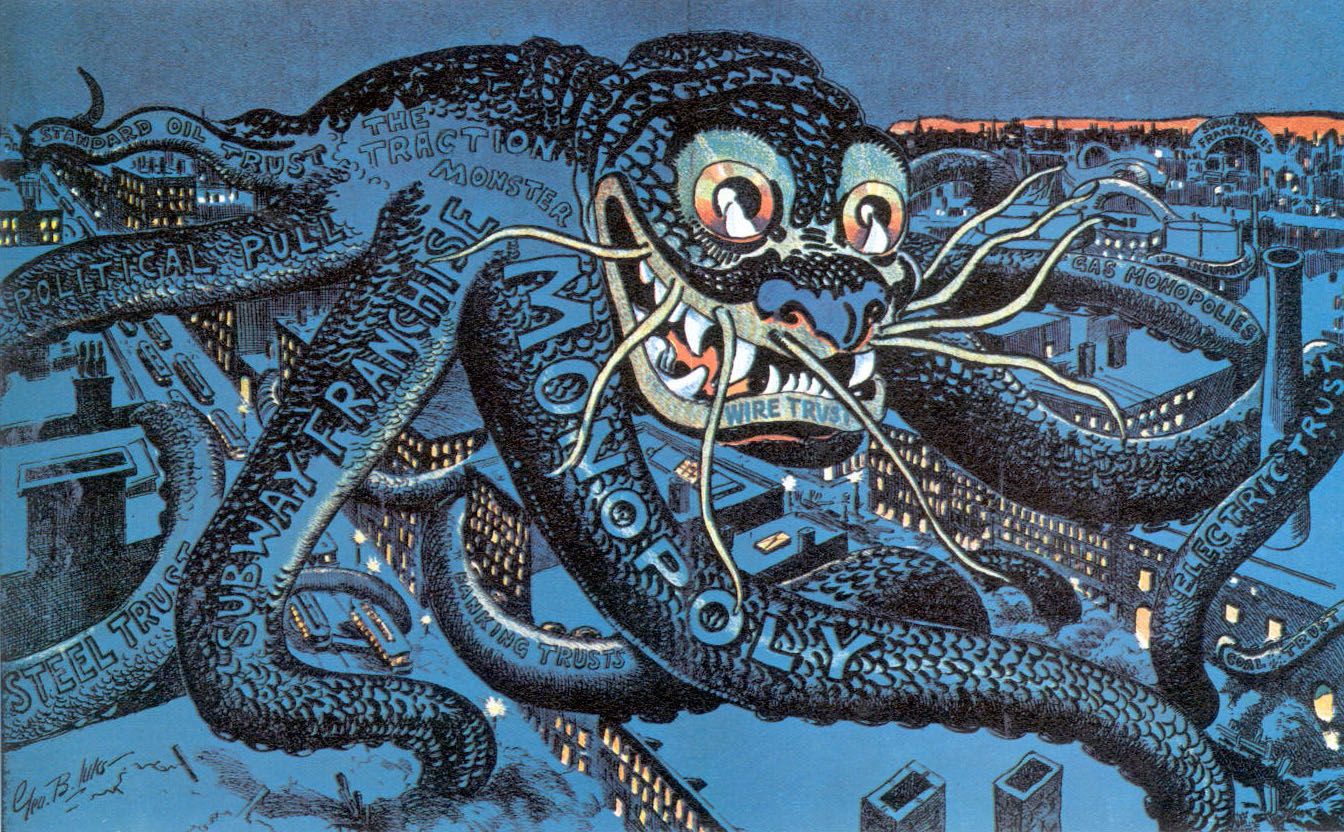

Opposition to traction interests and their influence on politicians was growing. For example, in 1922, New York Supreme Court Justice John Ford came out in favor of William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

, a newspaper magnate, for mayor of New York, complaining that Al Smith was too close to the 'traction interests'. In 1925, Hearst complained about Smith in a similar way. In the 1941 film ''Citizen Kane

''Citizen Kane'' is a 1941 American drama film produced by, directed by, and starring Orson Welles. He also co-wrote the screenplay with Herman J. Mankiewicz. The picture was Welles' first feature film. ''Citizen Kane'' is frequently cited ...

'', the lead character, who was loosely based on Hearst and Samuel Insull

Samuel Insull (November 11, 1859 – July 16, 1938) was a British-born American business magnate. He was an innovator and investor based in Chicago who greatly contributed to create an integrated electrical infrastructure in the United States ...

, complains about the influence of the 'traction interests'.

The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935

The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA), also known as the Wheeler-Rayburn Act, was a US federal law giving the Securities and Exchange Commission authority to regulate, license, and break up electric utility holding companies. It l ...

, which made it illegal for a single private business to both provide public transport

Public transport (also known as public transportation, public transit, mass transit, or simply transit) is a system of transport for passengers by group travel systems available for use by the general public unlike private transport, typical ...

and supply electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described ...

to other parties, forced electricity generator companies to divest from trolley, streetcar, electric suburban and interurban transit operators which they used to cross-subsidize in order to increase the basis of their limited return on investment.

National City Lines, Pacific City Lines, American City Lines

In 1936National City Lines

National City Lines, Inc. (NCL) was a public transportation company. The company grew out of the Fitzgerald brothers' bus operations, founded in Minnesota, United States in 1920 as a modest local transport company operating two buses. Part of the ...

, which had been started in 1920 as a minor bus operation by E. Roy Fitzgerald and his brother, was reorganized "for the purpose of taking over the controlling interest in certain operating companies engaged in city bus transportation and overland bus transportation" with loans from the suppliers and manufacturers. In 1939, Roy Fitzgerald, president of NCL, approached Yellow Coach Manufacturing, requesting additional financing for expansion. In the 1940s, NCL raised funds for expansion from Firestone Tire

Firestone Tire and Rubber Company is a tire company founded by Harvey Firestone (1868–1938) in 1900 initially to supply solid rubber side-wire tires for fire apparatus, and later, pneumatic tires for wagons, buggies, and other forms of wheele ...

, Federal Engineering, a subsidiary of Standard Oil of California (now Chevron Corporation), Phillips Petroleum

Phillips Petroleum Company was an American oil company incorporated in 1917 that expanded into petroleum refining, marketing and transportation, natural gas gathering and the chemicals sectors. It was Phillips Petroleum that first found oil in the ...

(now part of ConocoPhillips

ConocoPhillips Company is an American multinational corporation engaged in hydrocarbon exploration and production. It is based in the Energy Corridor district of Houston, Texas.

The company has operations in 15 countries and has production in ...

), GM, and Mack Trucks

Mack Trucks, Inc., is an American truck manufacturing company and a former manufacturer of buses and trolley buses. Founded in 1900 as the Mack Brothers Company, it manufactured its first truck in 1905 and adopted its present name in 1922. Mack ...

(now a subsidiary of Volvo

The Volvo Group ( sv, Volvokoncernen; legally Aktiebolaget Volvo, shortened to AB Volvo, stylized as VOLVO) is a Swedish multinational manufacturing corporation headquartered in Gothenburg. While its core activity is the production, distributio ...

). Pacific City Lines

Pacific City Lines was a company formed in 1937 as a subsidiary to National City Lines in Oakland, California. Its function was to purchase streetcar systems in the western United States as part of what became known as the Great American streetcar ...

(PCL), formed as a subsidiary of NCL in 1938, was to purchase streetcar systems in the western United States., Para 8 "Pacific City Lines was organized for the purpose of acquiring local transit companies on the Pacific Coast and commenced doing business in January 1938." PCL merged with NCL in 1948. American City Lines (ACL), which had been organized to acquire local transportation systems in the larger metropolitan areas in various parts of the country in 1943, was merged with NCL in 1946. The federal government investigated some aspects of NCL's financial arrangements in 1941 (which calls into question the conspiracy myths' centrality of Quinby's 1946 letter.) By 1947, NCL owned or controlled 46 systems in 45 cities in 16 states., para 6 "At the time the indictment was returned, the City Lines defendants had expanded their ownership or control to 46 transportation systems located in 45 cities across 16 states."

From 1939 through 1940, NCL or PCL attempted a hostile takeover

In business, a takeover is the purchase of one company (the ''target'') by another (the ''acquirer'' or ''bidder''). In the UK, the term refers to the acquisition of a public company whose shares are listed on a stock exchange, in contrast to ...

of the Key System

The Key System (or Key Route) was a privately owned company that provided mass transit in the cities of Oakland, Berkeley, Alameda, Emeryville, Piedmont, San Leandro, Richmond, Albany, and El Cerrito in the eastern San Francisco Bay Area fr ...

, which operated electric trains and streetcars in Oakland, California

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast of the United States, West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third ...

. The attempt was temporarily blocked by a syndicate of Key System insiders, with controlling interest secured on Jan 8, 1941. By 1946, PCL had acquired 64% of the stock in the Key System.

In 1945, NCL acquired the Los Angeles Railway

The Los Angeles Railway (also known as Yellow Cars, LARy and later Los Angeles Transit Lines) was a system of streetcars that operated in Central Los Angeles and surrounding neighborhoods between 1895 and 1963. The system provided frequent loc ...

(also known as the "Yellow Cars"), which had been in financial trouble for some time. The new owner slowed the closure of streetcar lines and converted others to trackless trolleys

A trolleybus (also known as trolley bus, trolley coach, trackless trolley, trackless tramin the 1910s and 1920sJoyce, J.; King, J. S.; and Newman, A. G. (1986). ''British Trolleybus Systems'', pp. 9, 12. London: Ian Allan Publishing. .or troll ...

, some of which used equipment initially intended for Oakland, others being purchased specifically in 1948. The LATL also bought new PCCs in one of the last major purchases of new streetcars.

Edwin J. Quinby

In 1946, Edwin Jenyss Quinby, an activated reservecommander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

, founder of the Electric Railroaders' Association in 1934 (which lobbied

In politics, lobbying, persuasion or interest representation is the act of lawfully attempting to influence the actions, policies, or decisions of government officials, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies. Lobbying, which ...

on behalf of rail users and services), and former employee of North Jersey Rapid Transit (which operated into New York State), published a 24-page "expose" on the ownership of National City Lines addressed to "The Mayors; The City Manager; The City Transit Engineer; The members of The Committee on Mass-Transportation and The Tax-Payers and The Riding Citizens of Your Community". It began, "This is an urgent warning to each and every one of you that there is a careful, deliberately planned campaign to swindle you out of your most important and valuable public utilities–your Electric Railway System". His activism may have led Federal authorities to prosecute GM and the other companies.

He also questioned who was behind the creation of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935

The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA), also known as the Wheeler-Rayburn Act, was a US federal law giving the Securities and Exchange Commission authority to regulate, license, and break up electric utility holding companies. It l ...

, which had caused such difficulty for streetcar operations, He was later to write a history of North Jersey Rapid Transit.

Court cases, conviction, and fines

On April 9, 1947, nine corporations and seven individuals (officers and directors of certain of the corporate defendants) wereindicted

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use the felonies concept often use that of an ...

in the Federal District Court of Southern California on counts of " conspiring to acquire control of a number of transit companies, forming a transportation monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

" and "conspiring to monopolize sales of buses and supplies to companies owned by National City Lines", para 1, "On April 9, 1947, nine corporations and seven individuals, constituting officers and directors of certain of the corporate defendants, were indicted on two counts, the second of which charged them with conspiring to monopolize certain portions of interstate commerce, in violation of Section 2 of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C.A. § 2." In 1948, the venue was changed from the Federal District Court of Southern California to the Federal District Court in Northern Illinois following an appeal to the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

(in ''United States v. National City Lines Inc.'') which felt that there was evidence of conspiracy to monopolize the supply of buses and supplies. "We think the evidence is clear that when any one of these suppliers was approached, its attitude was that it would be interested in helping finance City Lines, provided it should receive a contract for the exclusive use of its products in all of the operating companies of the City Lines, so far as buses and tires were concerned, and, as to the oil companies, in the territory served by the respective petroleum companies. It may be of little importance, but it seems to be the fact, at least we think the jury was justified in inferring it to be the fact, that the proposal for financing came from City Lines but that proposal of exclusive contracts came from the suppliers. At any rate, it is clear that eventually each supplier entered into a written contract of long duration whereby City Lines, in consideration of suppliers' help in financing City Lines, agreed that all of their operating subsidiaries should use only the suppliers' products."

In 1949, Firestone Tire, Standard Oil of California, Phillips Petroleum, GM, and Mack Trucks were convicted

In law, a conviction is the verdict reached by a court of law finding a defendant guilty of a crime. The opposite of a conviction is an acquittal (that is, "not guilty"). In Scotland, there can also be a verdict of "not proven", which is consid ...

of conspiring to monopolize the sale of buses and related products to local transit companies controlled by NCL; they were acquitted

In common law jurisdictions, an acquittal certifies that the accused is free from the charge of an offense, as far as criminal law is concerned. The finality of an acquittal is dependent on the jurisdiction. In some countries, such as the ...

of conspiring to monopolize the ownership of these companies. The verdicts were upheld on appeal

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

in 1951., para 33, "We have considered carefully all the evidence offered and excluded. We think that the court's rulings were fair, and that, having permitted great latitude in admitting testimony as to intent, purpose and reasons for the making of the contracts, the court, in its discretion, was entirely justified in excluding the additional testimony offered." GM was fined and GM treasurer H.C. Grossman was fined $1. The trial judge said "I am very frank to admit to counsel that after a very exhaustive review of the entire transcript in this case, and of the exhibits that were offered and received in evidence, that I might not have come to the same conclusion as the jury came to were I trying this case without a jury," explicitly noting that he might not himself have convicted in a bench trial

A bench trial is a trial by judge, as opposed to a trial by jury. The term applies most appropriately to any administrative hearing in relation to a summary offense to distinguish the type of trial. Many legal systems (Roman, Islamic) use bench ...

.

The San Diego Electric Railway

The San Diego Electric Railway (SDERy) was a mass transit system in Southern California, United States, using 600 volt DC streetcars and (in later years) buses.

The SDERy was established by sugar heir and land developer John D. Spreckels ...

was sold to Western Transit Company, which was in turn owned by J. L. Haugh in 1948 for $5.5 million. Haugh was also president of the Key System, and later was involved in Metropolitan Coach Line's purchase of the passenger operations of the Pacific Electric Railway

The Pacific Electric Railway Company, nicknamed the Red Cars, was a privately owned mass transit system in Southern California consisting of electrically powered streetcars, interurban cars, and buses and was the largest electric railway system ...

. The last San Diego streetcars were converted to buses by 1949. Haugh sold the bus-based San Diego system to the city in 1966.

The Baltimore Streetcar system operated by the Baltimore Transit Company was purchased by NCL in 1948 and started converting the system to buses. Overall Baltimore Transit ridership then plummeted by double digits in each of the following three years. The Pacific Electric Railway

The Pacific Electric Railway Company, nicknamed the Red Cars, was a privately owned mass transit system in Southern California consisting of electrically powered streetcars, interurban cars, and buses and was the largest electric railway system ...

's struggling passenger operations were purchased by Metropolitan Coach Lines in 1953 and were taken into public ownership in 1958 after which the last routes were converted to bus operation.

Urban Mass Transportation Act and 1974 Antitrust hearings

TheUrban Mass Transportation Act of 1964

The Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964 (, USC Title 49, Chapter 5 provided $375 million for large-scale urban public or private rail projects in the form of matching funds to cities and states. The Urban Mass Transportation Administration (now t ...

(UMTA) created the Urban Mass Transit Administration

The Federal Transit Administration (FTA) is an agency within the United States Department of Transportation (DOT) that provides financial and technical assistance to local public transportation systems. The FTA is one of ten modal administration ...

with a remit to "conserve and enhance values in existing urban areas" noting that "our national welfare therefore requires the provision of good urban transportation, with the properly balanced use of private vehicles and modern mass transport to help shape as well as serve urban growth". Funding for transit was increased with the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1970

The Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1970 () added to the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964 by authorizing an additional $12 billion of the same type of matching funds.

Earlier legislative attempts at establishing a federal transit funding p ...

and further extended by the National Mass Transportation Assistance Act The National Mass Transportation Assistance Act of 1974 is a United States federal law that extended the Urban Mass Transportation Act to cover operating costs as well as construction costs. This act was the culmination of a major lobbying effort b ...

(1974) which allowed funds to support transit operating costs as well as capital construction costs.

In 1970, Harvard Law student Robert Eldridge Hicks began working on the Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader (; born February 27, 1934) is an American political activist, author, lecturer, and attorney noted for his involvement in consumer protection, environmentalism, and government reform causes.

The son of Lebanese immigrants to the Un ...

Study Group Report on Land Use in California, alleging a wider conspiracy to dismantle U.S. streetcar systems, first published in ''Politics of Land: Ralph Nader's Study Group Report on Land Use in California''.

In 1972, Senator Philip Hart

Philip Aloysius Hart (December 10, 1912December 26, 1976) was an American lawyer and politician. A Democrat, he served as a United States Senator from Michigan from 1959 until his death from cancer in Washington, D.C. in 1976. He was known as t ...

introduced into congress the 'Industrial Reorganization Act', with an intention to restructure the U.S. economy to restore competition and address antitrust concern.

During 1973, Bradford Snell, an attorney with Pillsbury, Madison and Sutro and formerly, for a brief time, a scholar with the Brookings Institution

The Brookings Institution, often stylized as simply Brookings, is an American research group founded in 1916. Located on Think Tank Row in Washington, D.C., the organization conducts research and education in the social sciences, primarily in ec ...

, prepared a controversial and disputed paper titled "American ground transport: a proposal for restructuring the automobile, truck, bus, and rail industries." The paper, which was funded by the Stern Fund, was later described as the centerpiece of the hearings. In it, Snell said that General Motors was "a sovereign economic state" and said that the company played a major role in the displacement of rail and bus transportation by buses and trucks.

This paper was distributed in Senate binding together with an accompanying statement in February 1974, implying that the contents were the considered views of the Senate. The chair of the committee later apologized for this error. Adding to the confusion, Snell had already joined the Senate Judiciary Committee's Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly as a staff member.

At the hearings in April 1974, San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

mayor and antitrust attorney Joseph Alioto

Joseph Lawrence Alioto (February 12, 1916 – January 29, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 36th mayor of San Francisco, California, from 1968 to 1976.

Biography

Alioto was born in San Francisco in 1916. His father, Giuseppe ...

testified that "General Motors and the automobile industry generally exhibit a kind of ''monopoly evil''", adding that GM "has carried on a deliberate concerted action with the oil companies and tire companies...for the purpose of destroying a vital form of competition; namely, electric rapid transit". Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley also testified, saying that GM, through its subsidiaries (namely PCL), "scrapped the Pacific Electric and Los Angeles streetcar systems leaving the electric train system totally destroyed". Neither mayor, nor Snell himself, pointed out that the two cities were major parties to a lawsuit against GM which Snell himself had been "instrumental in bringing"; all had a direct or indirect financial interest. (The lawsuit was eventually dropped, the plaintiffs conceding they had no chance of winning.)

However, George Hilton, a professor of economics at UCLA and noted transit scholar rejected Snell's view, stating, "I would argue that these nell's

Nell's (or Nells) was a nightclub located on 246 West 14th Street in downtown Manhattan. It opened in the fall of 1986 in the space of a former electronics store and closed May 30, 2004.

History

Nell's opened in the fall of 1986 in the space of a ...

interpretations are not correct, and, further, that they couldn't possibly be correct, because major conversions in society of this character—from rail to free wheel urban transportation, and from steam to diesel railroad propulsion—are the sort of conversions which could come about only as a result of public preferences, technological change, the relative abundance of natural resources, and other impersonal phenomena or influence, rather than the machinations of a monopolist."

GM published a rebuttal the same year titled "The Truth About American Ground Transport". The Senate subcommittee printed GM's work in tandem with Snell's as an appendix to the hearings transcript. GM explicitly did not address the specific allegations that were ''sub judice''.

Role in decline of the streetcars

Quinby and Snell held that the destruction of streetcar systems was integral to a larger strategy to push the United States into automobile dependency. Most transit scholars disagree, suggesting that transit system changes were brought about by other factors; economic, social, and political factors such as unrealistic capitalization, fixed fares during inflation, changes in paving and automotive technology, theGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, antitrust action, the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935

The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA), also known as the Wheeler-Rayburn Act, was a US federal law giving the Securities and Exchange Commission authority to regulate, license, and break up electric utility holding companies. It l ...

, labor unrest A labour revolt or worker's uprising is a period of civil unrest characterised by strong labour militancy and strike activity. The history of labour revolts often provides the historical basis for many advocates of Marxism, communism, socialism and ...

, market forces

In economics, a market is a composition of systems, institutions, procedures, social relations or infrastructures whereby parties engage in exchange. While parties may exchange goods and services by barter, most markets rely on sellers offering ...

including declining industries' difficulty in attracting capital, rapidly increasing traffic congestion

Traffic congestion is a condition in transport that is characterized by slower speeds, longer trip times, and increased vehicular queueing. Traffic congestion on urban road networks has increased substantially since the 1950s. When traffic de ...

, the Good Roads Movement

The Good Roads Movement occurred in the United States between the late 1870s and the 1920s. It was the rural dimension of the Progressive movement. A key player was the United States Post Office Department. Once a commitment was made for Rural F ...

, urban sprawl

Urban sprawl (also known as suburban sprawl or urban encroachment) is defined as "the spreading of urban developments (such as houses and shopping centers) on undeveloped land near a city." Urban sprawl has been described as the unrestricted growt ...

, tax policies favoring private vehicle ownership, taxation of fixed infrastructure, franchise repair costs for co-located property, wide diffusion of driving skills, automatic transmission

An automatic transmission (sometimes abbreviated to auto or AT) is a multi-speed transmission used in internal combustion engine-based motor vehicles that does not require any input from the driver to change forward gears under normal driving c ...

buses, and general enthusiasm for the automobile.

The accuracy of significant elements of Snell's 1974 testimony was challenged in an article published in ''Transportation Quarterly'' in 1997 by Cliff Slater.

Recent journalistic revisitings question the idea that GM had a significant impact on the decline of streetcars, suggesting rather that they were setting themselves up to take advantage of the decline as it occurred. Guy Span suggested that Snell and others fell into simplistic conspiracy theory

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

thinking, bordering on paranoid delusions

A delusion is a false fixed belief that is not amenable to change in light of conflicting evidence. As a pathology, it is distinct from a belief based on false or incomplete information, confabulation, dogma, illusion, hallucination, or some o ...

stating,

In 2010, CBS's Mark Henricks reported:

Other factors

Other factors have been cited as reasons for the decline of streetcars and public transport generally in the United States. Robert Post notes that the ultimate reach of GM's alleged conspiracy extended to only about 10% of American transit systems. Guy Span says that actions and inaction by government was one of many contributing factors in the elimination of electric traction. "Clearly, GM waged a war on electric traction. It was indeed an all out assault, but by no means the single reason for the failure of rapid transit. Also, it is just as clear that actions and inactions by government contributed significantly to the elimination of electric traction." Cliff Slater suggested that the regulatory framework in the US actually protected the electric streetcars for longer than would have been the case if there was less regulation. "The issue is whether or not the buses that replaced the electric streetcars were economically superior. Without GM's interference would the United States today have a viable streetcar system? This article makes the case that under a less onerous regulatory environment, buses would have replaced streetcars even earlier than they actually did." Some regulations and regulatory changes have been linked directly to the decline of the streetcars: *Difficultlabor relations

Labor relations is a field of study that can have different meanings depending on the context in which it is used. In an international context, it is a subfield of labor history that studies the human relations with regard to work in its broadest ...

, and tight regulation of fares, routes, and schedules took their toll on city streetcar systems.

*The streetcars' contracts in many cities required them to keep the pavement on the roads surrounding the tracks in good shape. Such conditions, previously agreed to in exchange for the explicit right to operate as a monopoly in that city, became an expensive burden.

*The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935

The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA), also known as the Wheeler-Rayburn Act, was a US federal law giving the Securities and Exchange Commission authority to regulate, license, and break up electric utility holding companies. It l ...

prohibited regulated electric utilities from operating unregulated businesses, which included most streetcar lines. The act also placed restrictions on services operating across state lines. Many holding companies operated both streetcars and electric utilities across several states; those that owned both types of businesses were forced to sell off one. Declining streetcar business was often somewhat less valuable than the growing consumer electric business, resulting in many streetcar systems being put up for sale. The independent lines, no longer associated with an electric utility holding company, had to purchase electricity at full price from their former parents, further shaving their already thin margins. The Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

then left many streetcar operators short of funds for maintenance and capital improvements.

*In New York City, and other North American cities, the presence of restrictive legal agreements such as the Dual Contracts

The Dual Contracts, also known as the Dual Subway System, were contracts for the construction and/or rehabilitation and operation of rapid transit lines in the City of New York. The contracts were signed on March 19, 1913, by the Interborough Ra ...

, signed by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company

The Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) was the private operator of New York City's original underground subway line that opened in 1904, as well as earlier elevated railways and additional rapid transit lines in New York City. The IRT w ...

and Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation

The Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT) was an urban transit holding company, based in Brooklyn, New York City, United States, and incorporated in 1923. The system was sold to the city in 1940. Today, together with the IND subway s ...

of the New York City Subway

The New York City Subway is a rapid transit system owned by the government of New York City and leased to the New York City Transit Authority, an affiliate agency of the state-run Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Opened on October 2 ...

, restricted the ability of private mass transit operators to increase fares at a time of high inflation, allowed the city to take over them, or to operate competing subsidized transit.

Different funding models have also been highlighted:

*Streetcar lines were built using funds from private investors and were required to pay numerous taxes and dividend

A dividend is a distribution of profits by a corporation to its shareholders. When a corporation earns a profit or surplus, it is able to pay a portion of the profit as a dividend to shareholders. Any amount not distributed is taken to be re-in ...

s. By contrast, new roads were constructed and maintained by the government from tax income.

* By 1916, street railroads nationwide were wearing out their equipment faster than they were replacing it. While operating expenses were generally recovered, money for long-term investment was generally diverted elsewhere.

*The U.S. government responded to the Great Depression with massive subsidies for road construction.

*Later construction of the Interstate Highway System

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Highway System in the United States. Th ...

was authorized by the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, also known as the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act, was enacted on June 29, 1956, when President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the bill into law. With an original authorization of $25 billion for t ...

which approved the expenditure of $25 billion of public money for the creation of a new 41,000 miles (66,000 km) interstate road network. Streetcar operators were occasionally required to pay for the reinstatement of their lines following the construction of the freeways.

*Federal fuel taxes, introduced in 1956, were paid into a new Highway Trust Fund

The Highway Trust Fund is a transportation fund in the United States which receives money from a federal fuel tax of 18.4 cents per gallon on gasoline and 24.4 cents per gallon of diesel fuel and related excise taxes. It currently has two account ...

which could only fund highway construction (until 1983 when some 10% was diverted into a new Mass Transit Account).

Other issues which made it harder to operate viable streetcar services include:

*Suburbanization

Suburbanization is a population shift from central urban areas into suburbs, resulting in the formation of (sub)urban sprawl. As a consequence of the movement of households and businesses out of the city centers, low-density, peripheral urba ...

and urban sprawl

Urban sprawl (also known as suburban sprawl or urban encroachment) is defined as "the spreading of urban developments (such as houses and shopping centers) on undeveloped land near a city." Urban sprawl has been described as the unrestricted growt ...

, exacerbated in the US by white flight

White flight or white exodus is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the terms became popular in the United States. They refer ...

, created low-density land use patterns which are not easily served by streetcars, or indeed by any public transport, to this day.

*Increased traffic congestion often reduced service speeds and thereby increased their operational costs and made the services less attractive to the remaining users.

*More recently it has been suggested that the provision of free parking facilities at destinations and in the center of cities loads all users with the cost of facilities enjoyed only by motorists, creating additional traffic congestion and significantly affects the viability of other transport modes.

Counterarguments

Some of the specific allegations which have been argued over the years include: *According to Snell's testimony, theNew York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad

The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad , commonly known as The Consolidated, or simply as the New Haven, was a railroad that operated in the New England region of the United States from 1872 to December 31, 1968. Founded by the merger of ...

(NH) in New York and Connecticut was profitable until it was acquired and converted to diesel trains. "Members of GM's special unit went to, among others, the Southern Pacific, owner of Los Angeles' Pacific Electric, the world's largest interurban, with 1,500 miles of track, reaching 75 miles from San Bernardino, north to San Fernando, and south to Santa Ana; the New York Central Railroad

The New York Central Railroad was a railroad primarily operating in the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The railroad primarily connected greater New York and Boston in the east with Chicago and St. Louis in the Midw ...

, owner of the New York State Railways, 600 miles of street railways and interurban lines in upstate New York; and NH, owner of 1,500 miles of trolley lines in New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts. In each case, by threatening to divert lucrative automobile freight to rival carriers, they persuaded the railroad (according to GM's own files) to convert its electric street cars to motor buses – slow, cramped, foul-smelling vehicles whose inferior performance invariable led riders to purchase automobiles." Little of NH was converted to diesel, and remains in electric operation under Metro-North Railroad

Metro-North Railroad , trading as MTA Metro-North Railroad, is a suburban commuter rail service run by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), a New York State public benefit corporations, public authority of the U.S. state of New Yor ...

and Amtrak

The National Railroad Passenger Corporation, Trade name, doing business as Amtrak () , is the national Passenger train, passenger railroad company of the United States. It operates inter-city rail service in 46 of the 48 contiguous United Stat ...

. In reality, the line was in financial difficulty for years and filed for bankruptcy in 1935.

*"GM killed the New York street cars". In reality, the New York Railways Company

The New York Railways Company operated street railways in Manhattan, New York City, United States between 1911 and 1925. The company went into receivership in 1919 and control was passed to the New York Railways Corporation in 1925 after which a ...

entered receivership in 1919, six years before it was bought by the New York Railways Corporation

The New York Railways Corporation was a railway company that operated street railways in Manhattan, New York City, United States between 1925 and 1936. During 1935/1936 it converted its remaining lines to bus routes which were operated by the New ...

.

*"GM Killed the Red cars in Los Angeles". Pacific Electric Railway

The Pacific Electric Railway Company, nicknamed the Red Cars, was a privately owned mass transit system in Southern California consisting of electrically powered streetcars, interurban cars, and buses and was the largest electric railway system ...

(which operated the 'red cars') was hemorrhaging routes as traffic congestion worsened with growing car ownership levels after the end of World War II.. "Snell’s report can also be misleading (apparently intentionally so). Snell says: 'In 1940, GM, Standard Oil and Firestone assumed an active control in Pacific (City Lines)... That year, PCL began to acquire and scrap portions of the $100 million Pacific Electric System (of Roger Rabbit fame).' This statement implied that PCL was getting control of Pacific Electric, when, in reality, all they did was acquire the local streetcar systems of Pacific Electric in Glendale and Pasadena and then convert them to buses. Many superficial readers jump on this statement as proof that GM moved in the Red Cars of the Pacific Electric. The ugly little fact is that PCL never acquired Pacific Electric (it was owned by Southern Pacific Railroad until 1953)."

*The Salt Lake City system is mentioned in the 1949 court papers. However, the city's system was purchased by National City Lines

National City Lines, Inc. (NCL) was a public transportation company. The company grew out of the Fitzgerald brothers' bus operations, founded in Minnesota, United States in 1920 as a modest local transport company operating two buses. Part of the ...

in 1944 when all but one route had already been withdrawn, and the withdrawal of this last line had been approved three years earlier.

See also

*Federal Aid Road Act of 1916

The Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 (also known as the Bankhead–Shackleford Act and Good Roads Act), , , was enacted on July 11, 1916, and was the first federal highway funding legislation in the United States. The rise of the automobile at the star ...

*Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921 (Phipps Act)

Federal or foederal (archaic) may refer to:

Politics

General

*Federal monarchy, a federation of monarchies

*Federation, or ''Federal state'' (federal system), a type of government characterized by both a central (federal) government and states or ...

*Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, also known as the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act, was enacted on June 29, 1956, when President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the bill into law. With an original authorization of $25 billion for t ...

*Highway Trust Fund

The Highway Trust Fund is a transportation fund in the United States which receives money from a federal fuel tax of 18.4 cents per gallon on gasoline and 24.4 cents per gallon of diesel fuel and related excise taxes. It currently has two account ...

*Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation

The Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT) was an urban transit holding company, based in Brooklyn, New York City, United States, and incorporated in 1923. The system was sold to the city in 1940. Today, together with the IND subway s ...

(A corporation that was "recaptured" by the city using the Dual Contracts provisions)

* Chicago Motor Coach Company A bus transit company established by John Hertz in Chicago in 1917

*Dual Contracts

The Dual Contracts, also known as the Dual Subway System, were contracts for the construction and/or rehabilitation and operation of rapid transit lines in the City of New York. The contracts were signed on March 19, 1913, by the Interborough Ra ...

Contracts between New York City and subway operators which restricted fares, enforced share profits and allowed the city to 'recapture' and operate lines

*Transportation in metropolitan Detroit

Transportation in metropolitan Detroit is provided by a system of transit services, airports, and an advanced network of freeways which interconnect the city of Detroit and the Detroit region. The Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) a ...

(Details of a system that was already in public ownership)

*Toronto streetcar system

The Toronto streetcar system is a network of nine streetcar routes in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, operated by the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC). It is the busiest light-rail system in North America. The network is concentrated primarily in Dow ...

, which received much of the rolling stock from affected systems

*List of streetcar systems in the United States

This is an all-time list of streetcar (tram), interurban and light rail systems in the United States, by principal city (or cities) served, and separated by political division, with opening and closing dates. It includes all such systems, past a ...

*List of trolleybus systems in the United States

This is a list of trolleybus systems in the United States by State. It includes all trolleybus systems, past and present. About 65Murray, Alan (2000). ''World Trolleybus Encyclopaedia''. Yateley, Hampshire, UK: Trolleybooks. . trolleybus sy ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * A report presented to the Committee of the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly, United States Senate, February 26, 1974 * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

"The Great GM Conspiracy Legend: GM and the Red Cars", Stan Schwarz

* ttp://www.newday.com/films/Taken_for_a_Ride.html "Taken for a Ride", Jim Klein and Martha Olson – a 55-minute film first shown on PBS in August 1996br>United States v. National City Lines, Inc.'', 186 F.2d 562 (1951)

{{Pacific Electric Railway Streetcars in the United States Corporate crime

Streetcar

A tram (called a streetcar or trolley in North America) is a rail vehicle that travels on tramway tracks on public urban streets; some include segments on segregated right-of-way. The tramlines or networks operated as public transport are ...

Former monopolies

1930s in the United States

1940s in the United States

1950s in the United States

Automotive industry in the United States

Anti-competitive practices