General Boulanger on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

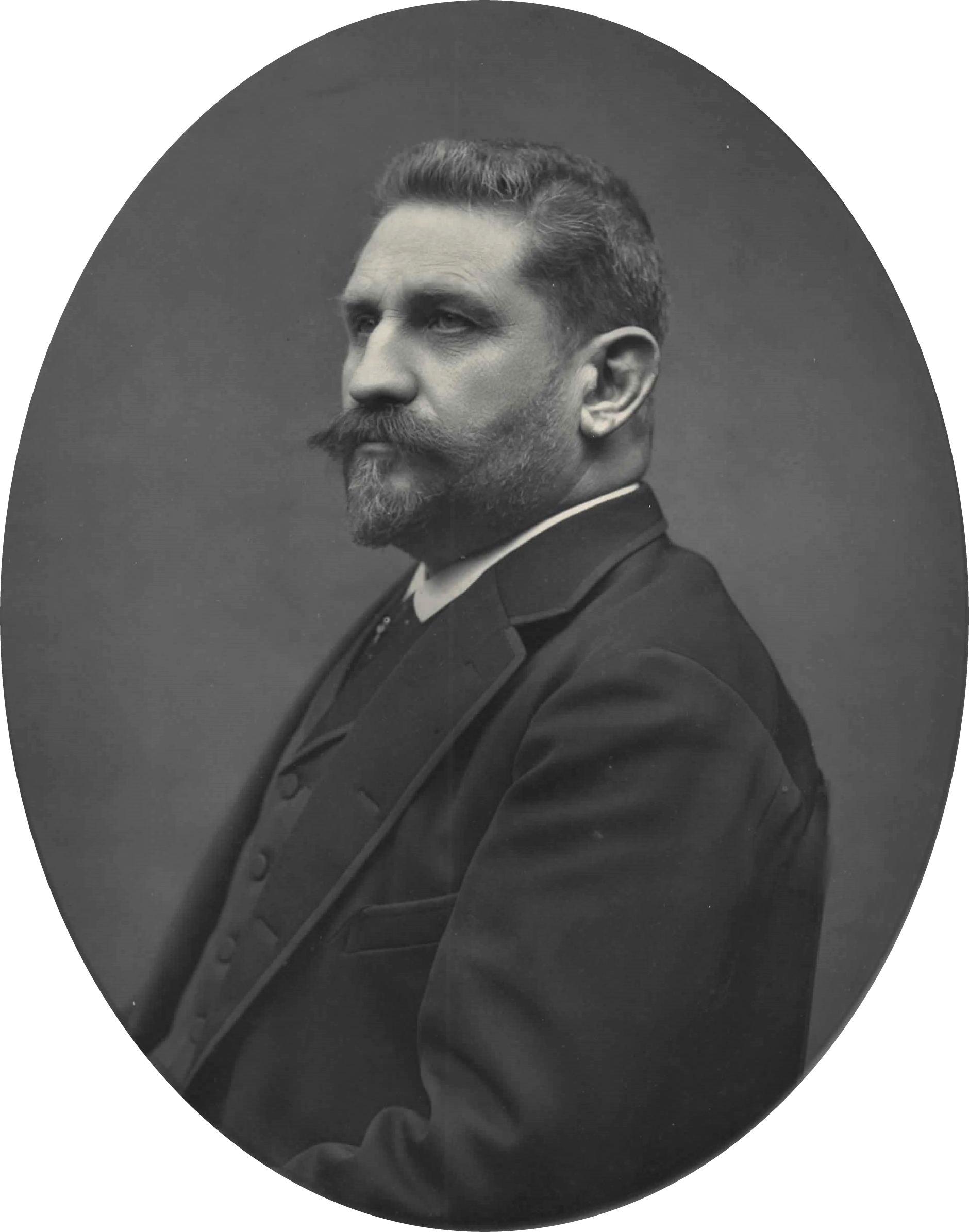

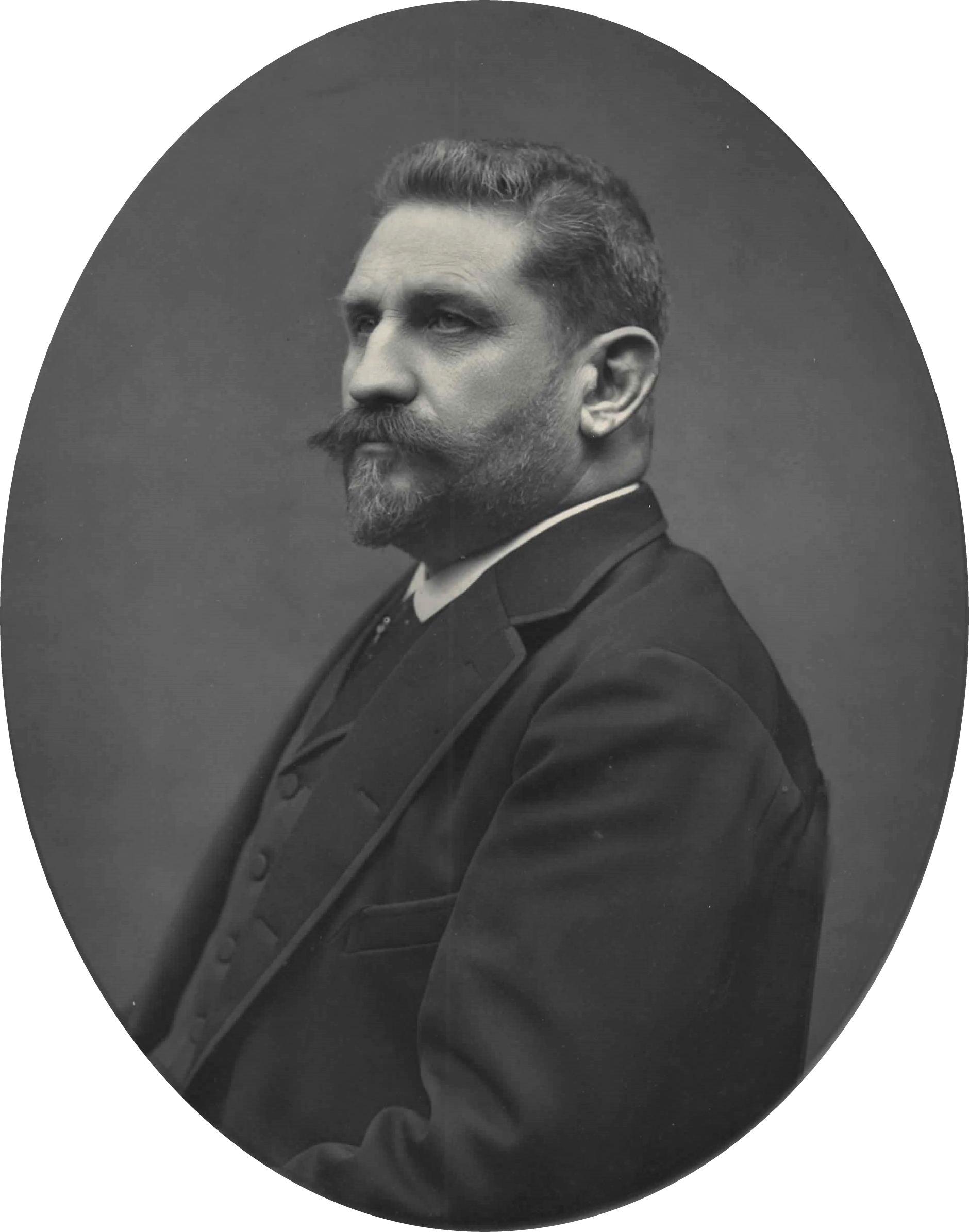

Georges Ernest Jean-Marie Boulanger (29 April 1837 – 30 September 1891), nicknamed Général Revanche ("General Revenge"), was a French general and politician. An enormously popular public figure during the second decade of the Third Republic, he won multiple elections. At the zenith of his popularity in January 1889, he was feared to be powerful enough to establish himself as dictator. His base of support was the working districts of

It was in the capacity of Minister of War that Boulanger gained most popularity. He introduced reforms for the benefit of soldiers (such as allowing soldiers to grow beards) and appealed to the French desire for revenge against

It was in the capacity of Minister of War that Boulanger gained most popularity. He introduced reforms for the benefit of soldiers (such as allowing soldiers to grow beards) and appealed to the French desire for revenge against

Although he was not in fact a legal candidate for the French

Although he was not in fact a legal candidate for the French

In January 1889, he ran as a deputy for Paris, and, after an intense campaign, took the seat with 244,000 votes against the 160,000 of his main adversary. A ''

In January 1889, he ran as a deputy for Paris, and, after an intense campaign, took the seat with 244,000 votes against the 160,000 of his main adversary. A ''

After his flight, support for him dwindled, and the Boulangists were defeated in the general elections of July 1889 (after the government forbade Boulanger from running). Boulanger himself went to live in

After his flight, support for him dwindled, and the Boulangists were defeated in the general elections of July 1889 (after the government forbade Boulanger from running). Boulanger himself went to live in

in JSTOR

* Patrick Hutton, "Popular Boulangism and the Advent of Mass Politics in France, 1886–90," ''Journal of Contemporary History'', vol. 11, no. 1, 1976, pp. 85–106.

in JSTOR

* William D. Irvine, "French Royalists and Boulangism,"''French Historical Studies''Vol. 15, No. 3 (Spring, 1988), pp. 395–40

in JSTOR

* William D. Irvine, ''The Boulanger Affair Reconsidered, Royalism, Boulangism, and the Origins of the Radical Right in France'', (Oxford University Press, 1989) * Jean-Marie Mayeur and Madeleine Rebérioux ''The Third Republic from its Origins to the Great War, 1871 – 1914'' (1984) pp 125–37 * René Rémond, ''The Right Wing in France from 1815 to de Gaulle'', translated by James M. Laux, 2nd American ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1969. * John Roberts, "General Boulanger" ''History Today'' ( Oct 1955) 5#10 pp 657–669, online * Peter M. Rutkoff, ''Revanche and Revision, The Ligue des Patriotes and the Origins of the Radical Right in France, 1882–1900'', Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1981. * Frederic Seager, ''The Boulanger Affair, Political Crossroads of France, 1886–1889'', Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1969.

''Le boulangisme''

*

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Boulanger, Georges 1837 births 1891 deaths 19th-century coups d'état and coup attempts Burials at Ixelles Cemetery Commandeurs of the Légion d'honneur French duellists French generals French Ministers of War French monarchists French people of Welsh descent French politicians who committed suicide Members of the Ligue des Patriotes Military personnel from Rennes Politicians of the French Third Republic Suicides by firearm in Belgium Politicians from Rennes

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

and other cities, plus rural traditionalist Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and royalists. He promoted an aggressive nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

, known as revanchism

Revanchism (french: revanchisme, from ''revanche'', " revenge") is the political manifestation of the will to reverse territorial losses incurred by a country, often following a war or social movement. As a term, revanchism originated in 1870s F ...

, which opposed Germany and called for the defeat of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) to be avenged.

The elections of September 1889 marked a decisive defeat for the Boulangists. Changes in the electoral laws prevented Boulanger from running in multiple constituencies and the aggressive opposition of the established government, combined with Boulanger's self-imposed exile, contributed to a rapid decline of the movement. The decline of Boulanger severely undermined the political strength of the conservative and royalist elements of French political life; they would not recover strength until the establishment of the Vichy regime

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

in 1940. The defeat of the Boulangists ushered in a period of political dominance by the Opportunist Republicans

The Moderates or Moderate Republicans (french: Républicains modérés), pejoratively labeled Opportunist Republicans (), was a French political group active in the late 19th century during the Third French Republic. The leaders of the group inc ...

.

Academics have attributed the failure of the movement to Boulanger's own weaknesses. Despite his charisma, he lacked coolness, consistency, and decisiveness; he was a mediocre leader who lacked vision and courage. He was never able to unite the disparate elements, ranging from the far left to the far right, that formed the base of his support. He was able, however, to frighten Republicans and force them to reorganize and strengthen their solidarity in opposition to him.

Early life and career

Boulanger was born on 29 April 1837 inRennes

Rennes (; br, Roazhon ; Gallo: ''Resnn''; ) is a city in the east of Brittany in northwestern France at the confluence of the Ille and the Vilaine. Rennes is the prefecture of the region of Brittany, as well as the Ille-et-Vilaine departm ...

, Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period o ...

. He was the youngest of three children born to Ernest Boulanger (1805–1884), a lawyer in Bourg-des-Comptes, and Mary-Ann Webb Griffith (1804–1894), born in Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city i ...

to a Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peopl ...

aristocratic family. His brother Ernest enlisted in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

and was killed in action during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

. Boulanger graduated from Saint-Cyr and entered regular service in the French Imperial Army in 1856. He fought in the Austro-Sardinian War

The Second Italian War of Independence, also called the Franco-Austrian War, the Austro-Sardinian War or Italian War of 1859 ( it, Seconda guerra d'indipendenza italiana; french: Campagne d'Italie), was fought by the Second French Empire and t ...

(he was wounded at Robecchetto con Induno, where he received the ''Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon B ...

''), and in the occupation of Cochinchina

Cochinchina or Cochin-China (, ; vi, Đàng Trong (17th century - 18th century, Việt Nam (1802-1831), Đại Nam (1831-1862), Nam Kỳ (1862-1945); km, កូសាំងស៊ីន, Kosăngsin; french: Cochinchine; ) is a historical exony ...

, after which he became a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

and instructor at Saint-Cyr. During the Franco-Prussian War, Georges Boulanger was noted for his bravery, and soon promoted to '' chef de bataillon''; he was again wounded while fighting at Champigny-sur-Marne

Champigny-sur-Marne (, literally ''Champigny on Marne'') is a commune in the southeastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris.

Name

Champigny-sur-Marne was originally called simply Champigny. The name Champigny ul ...

(during the Siege of Paris). Subsequently, Boulanger was among the Third Republic military leaders who crushed the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defende ...

in April–May 1871. He was wounded a third time as he led troops to the siege of the Panthéon

The Panthéon (, from the Classical Greek word , , ' empleto all the gods') is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was ...

, and was promoted ''commandeur'' of the ''Légion d'honneur'' by Patrice MacMahon. However, he was soon demoted (as his position was considered provisional), and his resignation in protest was rejected.

With backing from his direct superior, Henri d'Orléans, duc d'Aumale

Henri is an Estonian, Finnish, French, German and Luxembourgish form of the masculine given name Henry.

People with this given name

; French noblemen

:'' See the ' List of rulers named Henry' for Kings of France named Henri.''

* Henri I de Mo ...

(incidentally, one of the sons of former King Louis-Philippe

Louis Philippe (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850) was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, and the penultimate monarch of France.

As Louis Philippe, Duke of Chartres, he distinguished himself commanding troops during the Revolutionary War ...

), Boulanger was made a brigadier-general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

in 1880, and in 1882 War Minister

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

Jean-Baptiste Billot appointed him director of infantry at the war office, enabling him to make a name as a military reformer (he took measures to improve morale

Morale, also known as esprit de corps (), is the capacity of a group's members to maintain belief in an institution or goal, particularly in the face of opposition or hardship. Morale is often referenced by authority figures as a generic value ...

and efficiency). In 1884 he was appointed to command the army occupying Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

, but was recalled owing to his differences of opinion with Pierre-Paul Cambon, the political resident. He returned to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

, and began to take part in politics under the aegis of Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was ...

and the Radicals. In January 1886, when Charles de Freycinet

Charles Louis de Saulces de Freycinet (; 14 November 1828 – 14 May 1923) was a French statesman and four times Prime Minister during the Third Republic. He also served an important term as Minister of War (1888–1893). He belonged to the Op ...

was brought into power, Clemenceau used his influence to secure Boulanger's appointment as War Minister (replacing Jean-Baptiste Campenon). Clemenceau assumed Boulanger was a republican, because he was known not to attend Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different element ...

. However Boulanger would soon prove himself a conservative and monarchist.Charles Sowerwine (2001). ''France Since 1870''. pp. 60–62

Minister of War

It was in the capacity of Minister of War that Boulanger gained most popularity. He introduced reforms for the benefit of soldiers (such as allowing soldiers to grow beards) and appealed to the French desire for revenge against

It was in the capacity of Minister of War that Boulanger gained most popularity. He introduced reforms for the benefit of soldiers (such as allowing soldiers to grow beards) and appealed to the French desire for revenge against Imperial Germany

The German Empire (), Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditar ...

—in doing so, he came to be regarded as the man destined to serve that revenge (nicknamed ''Général Revanche''). He also managed to quell the major workers' strike in Decazeville

Decazeville ( oc, La Sala) is a commune in the Aveyron department in the Occitanie region in southern France.

The commune was created in the 19th century because of the Industrial Revolution and was named after the Duke of Decazes (1780–1 ...

. A minor scandal arose when Philippe, comte de Paris

Prince Philippe of Orléans, Count of Paris (Louis Philippe Albert; 24 August 1838 – 8 September 1894), was disputedly King of the French from 24 to 26 February 1848 as Louis Philippe II, although he was never officially proclaimed as such. ...

, the nominal inheritor of the French throne in the eyes of Orléanist

Orléanist (french: Orléaniste) was a 19th-century French political label originally used by those who supported a constitutional monarchy expressed by the House of Orléans. Due to the radical political changes that occurred during that cent ...

monarchists, married his daughter Amélie

''Amélie'' (also known as ''Le Fabuleux Destin d'Amélie Poulain''; ; en, The Fabulous Destiny of Amélie Poulain, italic=yes) is a 2001 French-language romantic comedy film directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet. Written by Jeunet with Guillaume La ...

to Portugal's Carlos I, in a lavish wedding that provoked fears of anti-Republican ambitions. The French parliament hastily passed a law expelling all possible claimants to the crown from French territories. Boulanger communicated to d'Aumale his expulsion from the armed forces. He received the adulation of the public and the press after the Sino-French War

The Sino-French War (, french: Guerre franco-chinoise, vi, Chiến tranh Pháp-Thanh), also known as the Tonkin War and Tonquin War, was a limited conflict fought from August 1884 to April 1885. There was no declaration of war. The Chinese arm ...

, when France's victory added Tonkin

Tonkin, also spelled ''Tongkin'', ''Tonquin'' or ''Tongking'', is an exonym referring to the northern region of Vietnam. During the 17th and 18th centuries, this term referred to the domain '' Đàng Ngoài'' under Trịnh lords' control, inclu ...

to its colonial empire

A colonial empire is a collective of territories (often called colonies), either contiguous with the imperial center or located overseas, settled by the population of a certain state and governed by that state.

Before the expansion of early mod ...

.

He also vigorously pressed for the accelerated adoption, in just first five months of 1886, of a new rifle for the technically revolutionary smokeless powder

Finnish smokeless powderSmokeless powder is a type of propellant used in firearms and artillery that produces less smoke and less fouling when fired compared to gunpowder ("black powder"). The combustion products are mainly gaseous, compared to ...

Poudre B

Poudre B was the first practical smokeless gunpowder created in 1884. It was perfected between 1882 and 1884 at "Laboratoire Central des Poudres et Salpêtres" in Paris, France. Originally called "Poudre V" from the name of the inventor, Paul V ...

developed by P. Vielle two years earlier. Essentially, that backfired: hastily developed 8×50mmR Lebel

The 8×50mmR Lebel (8mm Lebel) (designated as the 8 × 51 R Lebel by the C.I.P.) rifle cartridge was the first smokeless powder cartridge to be made and adopted by any country. It was introduced by France in 1886. Formed by necking down the ...

cartridge became an unprecedented high-velocity ammunition but due to its double taper and rim handicapped French firearm development for decades to come, and hastily designed Lebel Model 1886 rifle

The Lebel Model 1886 rifle (French: ''Fusil Modèle 1886 dit "Fusil Lebel"'') also known as the ''"Fusil Mle 1886 M93"'', after a bolt modification was added in 1893, is an 8 mm bolt-action infantry rifle that entered service in the French A ...

, essentially a strengthened Kropatschek rifle from late 1870s, became morally obsolete much faster than any of the magazine rifles of other European militaries that followed during late 1880s and 1890s (before Boulanger, the French military planned to adopt a much more modern design as well). Boulanger also ordered to produce a million rifles by May 1887, but his proposal how to achieve that was entirely unrealistic (with the best efforts in manufacturing it took several years).

On Freycinet's defeat in December of the same year, Boulanger was retained by René Goblet at the war office. Confident of political support, the general began provoking the Germans; he ordered military facilities to be built in the border region of Belfort

Belfort (; archaic german: Beffert/Beffort) is a city in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region in Northeastern France, situated between Lyon and Strasbourg, approximately from the France–Switzerland border. It is the prefecture of the Terr ...

, forbade the export of horses to German markets, and even instigated a ban on presentations of ''Lohengrin

Lohengrin () is a character in German Arthurian literature. The son of Parzival (Percival), he is a knight of the Holy Grail sent in a boat pulled by swans to rescue a maiden who can never ask his identity. His story, which first appears in Wolf ...

''. Germany responded by calling to arms more than 70,000 reservist

A reservist is a person who is a member of a military reserve force. They are otherwise civilians, and in peacetime have careers outside the military. Reservists usually go for training on an annual basis to refresh their skills. This person i ...

s in February 1887. After the Schnaebele incident (April 1887), war was averted, but Boulanger was perceived by his supporters as coming out on top against Bismarck. For the Goblet government, Boulanger was an embarrassment and risk, and became engaged in a dispute with Foreign Minister Émile Flourens. On 17 May Goblet was voted out of office and replaced by Maurice Rouvier. The latter sacked Boulanger, and replaced him with on 30 May.

The rise of ''Boulangisme''

The government was astonished by the revelation that Boulanger had received around 100,000 votes for the partial election inSeine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres plate ...

, without even being a candidate. He was removed from the Paris region and sent to the provinces, appointed commander of the troops stationed in Clermont-Ferrand

Clermont-Ferrand (, ; ; oc, label= Auvergnat, Clarmont-Ferrand or Clharmou ; la, Augustonemetum) is a city and commune of France, in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, with a population of 146,734 (2018). Its metropolitan area (''aire d'attra ...

. Upon his departure on 8 July, a crowd of ten thousand took the Gare de Lyon

The Gare de Lyon, officially Paris-Gare-de-Lyon, is one of the six large mainline railway stations in Paris, France. It handles about 148.1 million passengers annually according to the estimates of the SNCF in 2018, with SNCF railways and RER ...

by storm, covering his train with posters titled ''Il reviendra'' ("He will come back"), and blocking the railway, but he was smuggled out.

The general decided to gather support for his own movement, an eclectic one that capitalized on the frustrations of French conservatism

Conservatism is a Philosophy of culture, cultural, Social philosophy, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in r ...

, advocating the three principles of ''Revanche'' (Revenge on Germany), ''Révision'' (Revision of the Constitution), '' Restauration'' (the return to monarchy). The common reference to it has become ''Boulangisme'', a term used by its partisans and adversaries alike. Immediately, the new popular movement was backed by notable conservative figures such as Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New Yor ...

Arthur Dillon, Alfred Joseph Naquet, Anne de Rochechouart de Mortemart

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

( Duchess of Uzès, who financed him with immense sums), Arthur Meyer, Paul Déroulède

Paul Déroulède (2 September 1846 – 30 January 1914) was a French author and politician, one of the founders of the nationalist League of Patriots.

Early life

Déroulède was born in Paris. He was published first as a poet in the magazine '' ...

(and his ''Ligue des Patriotes

The League of Patriots (french: Ligue des Patriotes) was a French far-right league, founded in 1882 by the nationalist poet Paul Déroulède, historian Henri Martin and politician Félix Faure. The Ligue began as a non-partisan nationalist lea ...

'').

After the political corruption scandal surrounding the President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

's son-in-law Daniel Wilson, who was secretly selling ''Légion d'honneur'' medals to anyone who wanted, the Republican government was brought into disrepute and Boulanger's popular appeal rose in contrast. His position became essential after President Jules Grévy was forced to resign due to the scandal: in January 1888, the ''boulangistes'' promised to back any candidate for the presidency that would in turn offer his support to Boulanger for the post of War Minister (France was a parliamentary republic

A parliamentary republic is a republic that operates under a parliamentary system of government where the executive branch (the government) derives its legitimacy from and is accountable to the legislature (the parliament). There are a number ...

). The crisis was cut short by the election of Marie François Sadi Carnot

Marie François Sadi Carnot (; 11 August 1837 – 25 June 1894) was a French statesman, who served as the President of France from 1887 until his assassination in 1894.

Early life

Marie François Sadi Carnot was the son of the statesman Hippo ...

and the appointment of Pierre Tirard as Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

—Tirard refused to include Boulanger in his cabinet. During the period, Boulanger was in Switzerland, where he met with Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte II, technically a Bonapartist

Bonapartism (french: Bonapartisme) is the political ideology supervening from Napoleon Bonaparte and his followers and successors. The term was used to refer to people who hoped to restore the House of Bonaparte and its style of government. In thi ...

, who offered his full support to the cause. The Bonapartists had attached themselves to the general, and even the Comte de Paris encouraged his followers to support him. Once seen as a republican, Boulanger showed his true colors in the camp of the conservative monarchists. On 26 March 1888 he was expelled from the army. The day after, Daniel Wilson had his imprisonment repealed. It seemed to the French people that honorable generals were punished while corrupt politicians were spared, further increasing Boulanger's popularity.

Although he was not in fact a legal candidate for the French

Although he was not in fact a legal candidate for the French Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourbon ...

(since he was a military man), Boulanger ran with Bonapartist backing in seven separate '' départements'' during the remainder of 1888. ''Boulangiste'' candidates were present in every ''département''. Consequently, he and many of his supporters were voted to the Chamber, and accompanied by a large crowd on 12 July, the day of their swearing in—the general himself was elected in the constituency of Nord

Nord, a word meaning "north" in several European languages, may refer to:

Acronyms

* National Organization for Rare Disorders, an American nonprofit organization

* New Orleans Recreation Department, New Orleans, Louisiana, US

Film and televis ...

. The ''boulangistes'' were, nonetheless, a minority in the Chamber. Since Boulanger could not pass legislation, his actions were directed to maintaining his public image. Neither his failure as an orator nor his defeat in a duel with Charles Thomas Floquet

Charles Thomas Floquet (; 2 October 1828 – 18 January 1896) was a French lawyer and statesman.

Biography

He was born at Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port ( Basses-Pyrénées). Charles Floquet is the son of Pierre Charlemagne Floquet and Marie Léocadie ...

, then an elderly civilian and the minister of the interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

, reduced the enthusiasm of his popular following.

During 1888 his personality was the dominating feature of French politics, and, when he resigned his seat as a protest against the reception given by the Chamber to his proposals, constituencies vied with one another in selecting him as their representative. His name was the theme of the popular song ''C'est Boulanger qu'il nous faut'' ("Boulanger is the One We Need"), he and his black horse became the idol of the Parisian population, and he was urged to run for the presidency. The general agreed, but his personal ambitions soon alienated his republican supporters, who recognised in him a potential military dictator. Numerous monarchists continued to give him financial aid, even though Boulanger saw himself as a leader rather than a restorer of kings.

Downfall

In January 1889, he ran as a deputy for Paris, and, after an intense campaign, took the seat with 244,000 votes against the 160,000 of his main adversary. A ''

In January 1889, he ran as a deputy for Paris, and, after an intense campaign, took the seat with 244,000 votes against the 160,000 of his main adversary. A ''coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, ...

'' seemed probable and desirable among his supporters. Boulanger had now become a threat to the parliamentary Republic. Had he immediately placed himself at the head of a revolt he might have effected the coup which many of his partisans had worked for, and might even have governed France; but the opportunity passed with his procrastination on 27 January. According to Lady Randolph Churchill " l his thoughts were centered in and controlled by her who was the mainspring of his life. After the plebiscite...he rushed off to Madame Bonnemain's house and could not be found".

Boulanger decided that it would be better to contest the general election and take power legally. This, however, gave his enemies the time they needed to strike back. Ernest Constans, the Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

, decided to investigate the matter, and attacked the ''Ligue des Patriotes'' using the law banning the activities of secret societies

A secret society is a club or an organization whose activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence ...

.

Shortly afterward the French government issued a warrant for Boulanger's arrest for conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, is a secret plan or agreement between persons (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder or treason, especially with political motivation, while keeping their agr ...

and treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

able activity. To the astonishment of his supporters, on 1 April he fled Paris before it could be executed, going first to Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

and then to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. On 4 April the Parliament stripped him of his immunity from prosecution

Legal immunity, or immunity from prosecution, is a legal status wherein an individual or entity cannot be held liable for a violation of the law, in order to facilitate societal aims that outweigh the value of imposing liability in such cases. Su ...

; the French Senate

The Senate (french: Sénat, ) is the upper house of the French Parliament, with the lower house being the National Assembly, the two houses constituting the legislature of France. The French Senate is made up of 348 senators (''sénateurs'' a ...

condemned him and his supporters, Rochefort

Rochefort () may refer to:

Places France

* Rochefort, Charente-Maritime, in the Charente-Maritime department

** Arsenal de Rochefort, a former naval base and dockyard

* Rochefort, Savoie in the Savoie department

* Rochefort-du-Gard, in the Ga ...

, and Count Dillon for treason, sentencing all three to deportation

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. The term ''expulsion'' is often used as a synonym for deportation, though expulsion is more often used in the context of international law, while deportation ...

and confinement.

In 1890 ''Le Figaro

''Le Figaro'' () is a French daily morning newspaper founded in 1826. It is headquartered on Boulevard Haussmann in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. The oldest national newspaper in France, ''Le Figaro'' is one of three French Newspaper of recor ...

'' caused a sensation by alleging that Boulanger's London promoter Alexander Meyrick Broadley

Alexander Meyrick Broadley (19 July 1847 – 16 April 1916), also known as Broadley Pasha, was a British barrister, author, company promoter and social figure. He is best known for being the defence lawyer for Ahmed 'Urabi after the failure ...

had taken Boulanger and Rochefort to the male brothel at the centre of the Cleveland Street Scandal

The Cleveland Street scandal occurred in 1889, when a homosexual male brothel and house of assignation on Cleveland Street, London, was discovered by police. The government was accused of covering up the scandal to protect the names of aristocra ...

, an allegation that Dillon was forced to publicly deny.

Death

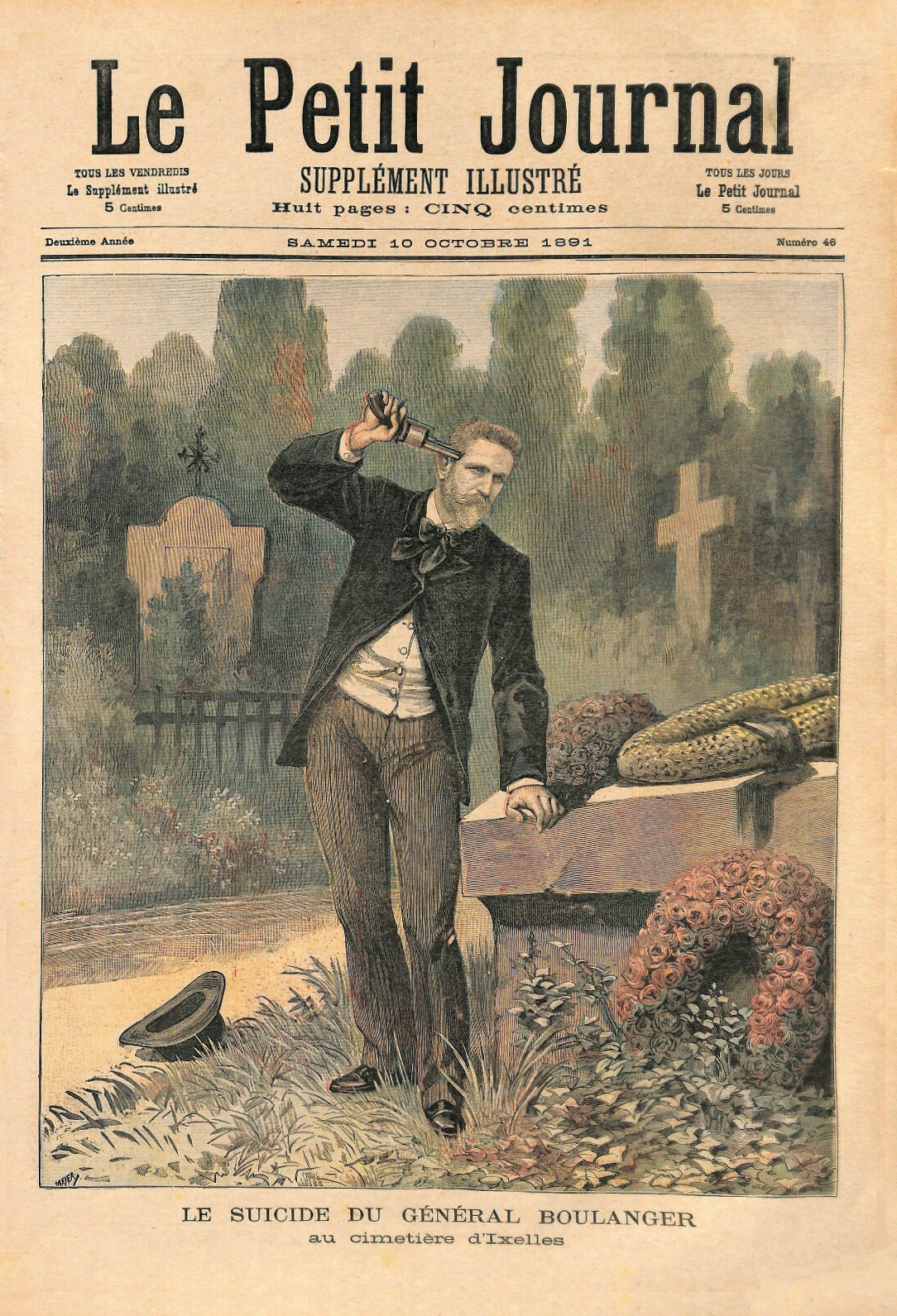

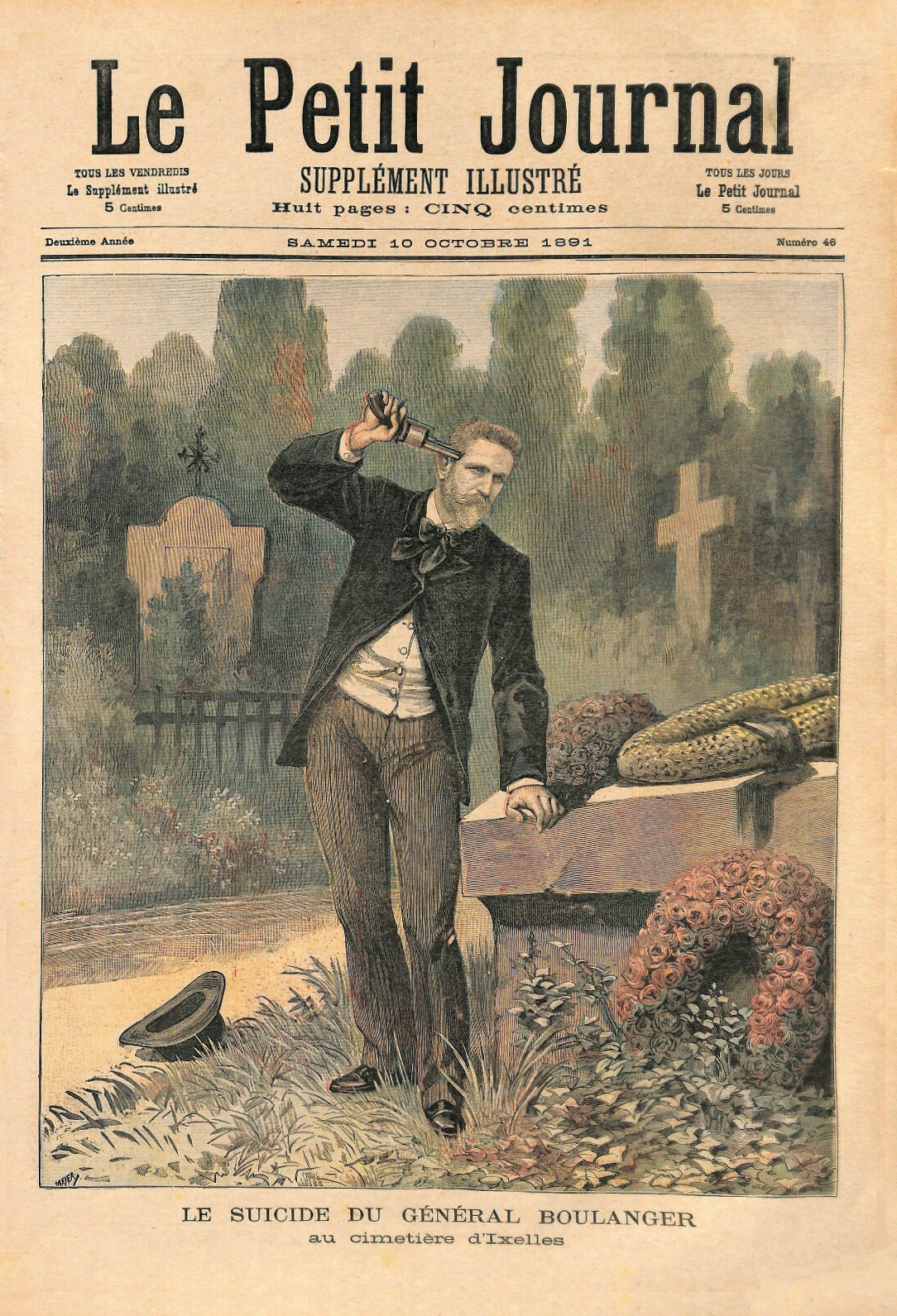

After his flight, support for him dwindled, and the Boulangists were defeated in the general elections of July 1889 (after the government forbade Boulanger from running). Boulanger himself went to live in

After his flight, support for him dwindled, and the Boulangists were defeated in the general elections of July 1889 (after the government forbade Boulanger from running). Boulanger himself went to live in Jersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, Jèrri, label=Jèrriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; Jèrriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependencies, Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west F ...

before returning to the Ixelles Cemetery in Brussels in September 1891 to kill himself with a bullet to the head on the grave of his mistress, Madame de Bonnemains (née Marguerite Brouzet) who had died in his arms the preceding July. He was buried in the same grave.

The Boulangist movement

Marxist historians viewed the Boulangist movement as a proto-fascist right-wing movement. A number of scholars have presented boulangism as a precursor of fascism, includingZeev Sternhell

Zeev Sternhell ( he, זאב שטרנהל; 10 April 1935 – 21 June 2020) was a Polish-born Israeli historian, political scientist, commentator on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and writer. He was one of the world's leading theorists of the ...

and Stanley Payne.

France's right was based in the old aristocracy, but this new movement was based on mass popular feeling that was national, rather than class-based. As Jacques Néré says, "Boulangism was first and foremost a popular movement of the extreme left". Irvine says he had some royalist support but that, "Boulangism is better understood as the coalescence of the fragmented forces of the Left." This interpretation is part of a consensus that France's radical right was formed in part during the Dreyfus era by men who had been Boulangist partisans of the radical left a decade earlier.

Boulanger gained the support of a number of former Communards

The Communards () were members and supporters of the short-lived 1871 Paris Commune formed in the wake of the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War.

After the suppression of the Commune by the French Army in May 1871, 43,000 Communards ...

from the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (french: Commune de Paris, ) was a revolutionary government that seized power in Paris, the capital of France, from 18 March to 28 May 1871.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defende ...

and some supporters of Blanquism

Blanquism refers to a conception of revolution generally attributed to Louis Auguste Blanqui (1805–1881) which holds that socialist revolution should be carried out by a relatively small group of highly organised and secretive conspirators. Ha ...

(a faction within the Central Revolutionary Committee

The Central Revolutionary Committee (french: Comité révolutionnaire central, CRC) was a French Blanquist political party founded in 1881 and dissolved in 1898.

The CRC was founded by Édouard Vaillant to continue the political struggle of Augu ...

). This included men such as Victor Jaclard, Ernest Granger and Henri Rochefort

Henri is an Estonian, Finnish, French, German and Luxembourgish form of the masculine given name Henry.

People with this given name

; French noblemen

:'' See the ' List of rulers named Henry' for Kings of France named Henri.''

* Henri I de Mo ...

.

In popular culture

Général Boulanger inspired the Jean Renoir movie ''Elena and Her Men

''Elena and Her Men'' is a 1956 film directed by Jean Renoir and starring Ingrid Bergman and Jean Marais. The film's original French title was ''Elena et les Hommes'', and in English-speaking countries, the title was ''Paris Does Strange Thing ...

'', a musical fantasy loosely based on the end of his political career. The role of ''Général François Rollan'', a Boulanger-like character, was played by Jean Marais

Jean-Alfred Villain-Marais (11 December 1913 – 8 November 1998), known professionally as Jean Marais (), was a French actor, film director, theatre director, painter, sculptor, visual artist, writer and photographer. He performed in over 100 f ...

.

IMDb

IMDb (an abbreviation of Internet Movie Database) is an online database of information related to films, television series, home videos, video games, and streaming content online – including cast, production crew and personal biographies, p ...

notes that there was also a French television programme about Boulanger in the early 1980s, ''La Nuit du général Boulanger'' where Boulanger is played by Maurice Ronet

Maurice Ronet (13 April 1927 – 14 March 1983) was a French film actor, director, and writer.

Early life

Maurice Ronet was born Maurice Julien Marie Robinet in Nice, Alpes Maritimes. He was the only child of professional stage actors Émile Rob ...

.

He is quoted as the one who authorised the institution of the "Suicide Bureau" in Guy de Maupassant

Henri René Albert Guy de Maupassant (, ; ; 5 August 1850 – 6 July 1893) was a 19th-century French author, remembered as a master of the short story form, as well as a representative of the Naturalist school, who depicted human lives, destin ...

's short story "The Magic Couch", reportedly "the only good thing he did".

Maurice Leblanc

Maurice Marie Émile Leblanc (; ; 11 December 1864 – 6 November 1941) was a French novelist and writer of short stories, known primarily as the creator of the fictional gentleman thief and detective Arsène Lupin, often described as a French c ...

also mentions him in his 1924 novel ''The Countess of Cagliostro''.

References

Further reading

* D. W. Brogan. ''France under the Republic: The development of modern France (1870–1939)'' (1940) pp 183–216 * Michael Burns, ''Rural Society and French Politics, Boulangism and the Dreyfus Affair, 1886–1900'' (Princeton University Press, 1984) * Patrick Hutton, "The Impact of the Boulangist Crisis on the Guesdist Party at Bordeaux," ''French Historical Studies'', vol. 7, no. 2, 1973, pp. 226–44in JSTOR

* Patrick Hutton, "Popular Boulangism and the Advent of Mass Politics in France, 1886–90," ''Journal of Contemporary History'', vol. 11, no. 1, 1976, pp. 85–106.

in JSTOR

* William D. Irvine, "French Royalists and Boulangism,"''French Historical Studies''Vol. 15, No. 3 (Spring, 1988), pp. 395–40

in JSTOR

* William D. Irvine, ''The Boulanger Affair Reconsidered, Royalism, Boulangism, and the Origins of the Radical Right in France'', (Oxford University Press, 1989) * Jean-Marie Mayeur and Madeleine Rebérioux ''The Third Republic from its Origins to the Great War, 1871 – 1914'' (1984) pp 125–37 * René Rémond, ''The Right Wing in France from 1815 to de Gaulle'', translated by James M. Laux, 2nd American ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1969. * John Roberts, "General Boulanger" ''History Today'' ( Oct 1955) 5#10 pp 657–669, online * Peter M. Rutkoff, ''Revanche and Revision, The Ligue des Patriotes and the Origins of the Radical Right in France, 1882–1900'', Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1981. * Frederic Seager, ''The Boulanger Affair, Political Crossroads of France, 1886–1889'', Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1969.

French studies

* Adrien Dansette, ''Le Boulangisme, De Boulanger à la Révolution Dreyfusienne, 1886–1890'', Paris: Libraire Academique Perrin, 1938. *Raoul Girardet

Raoul Girardet (6 October 1917 – 18 September 2013) was a French historian who specialized in military societies, colonialism and French nationalism.

As a young man he was involved with the right-wing Action Française movement.

He was not antis ...

, ''Le Nationalisme français, 1871–1914'', Paris: A. Colin, 1966.

* Jacques Néré, ''Le Boulangisme et la Presse'', Paris: A. Colin, 1964.

* Odile Rudelle, ''La République Absolue, Aux origines de l'instabilité constitutionelle de la France républicaine, 1870–1889'', Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 1982.

* Zeev Sternhell, ''La Droite Révolutionnaire, 1885–1914; Les Origines Françaises du Fascisme'', Paris: Gallimard, 1997.

External links

*''Le boulangisme''

*

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Boulanger, Georges 1837 births 1891 deaths 19th-century coups d'état and coup attempts Burials at Ixelles Cemetery Commandeurs of the Légion d'honneur French duellists French generals French Ministers of War French monarchists French people of Welsh descent French politicians who committed suicide Members of the Ligue des Patriotes Military personnel from Rennes Politicians of the French Third Republic Suicides by firearm in Belgium Politicians from Rennes