Gen 75 Committee on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Gen 75 Committee was a

The Gen 75 Committee was a

The Gen 75 Committee was a

The Gen 75 Committee was a committee

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them more ...

of the British cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

, convened by the Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

, on 10 August 1945. It was one of many ''ad hoc'' cabinet committees, each of which was convened to handle a single issue, and given a prefix of Gen (for general) and a number. The purpose of the Gen 75 committee was to discuss and establish the British government's nuclear policy. Attlee dubbed it the "Atom Bomb Committee". It was replaced by an official ministerial committee, the Atomic Energy Committee, in February 1947.

Matters considered by the Gen 75 Committee included decisions on what production facilities should be built to produce nuclear weapons, authorising the construction of nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

s to produce plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

at Windscale

Sellafield is a large multi-function nuclear site close to Seascale on the coast of Cumbria, England. As of August 2022, primary activities are nuclear waste processing and storage and nuclear decommissioning. Former activities included nucle ...

, and a gaseous diffusion

Gaseous diffusion is a technology used to produce enriched uranium by forcing gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6) through semipermeable membranes. This produces a slight separation between the molecules containing uranium-235 (235U) and uranium-2 ...

plant to produce uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exis ...

at Capenhurst

Capenhurst is a village and civil parish in Chester in the unitary authority of Cheshire West and Chester and the ceremonial county of Cheshire England. According to the 2001 Census, Capenhurst had a population of 237, increasing to 380 at the 2 ...

. It took decisions on the administrative structures that would oversee production, and appointed Marshal of the Royal Air Force

Marshal of the Royal Air Force (MRAF) is the highest rank in the Royal Air Force (RAF). In peacetime it was granted to RAF officers in the appointment of Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS), and to retired Chiefs of the Air Staff (CAS), who were ...

Lord Portal, the wartime Chief of the Air Staff, to run the project, which became High Explosive Research

High Explosive Research (HER) was the British project to develop atomic bombs independently after the Second World War. This decision was taken by a cabinet sub-committee on 8 January 1947, in response to apprehension of an American retur ...

. The final decision to proceed with building nuclear weapons, however, was made by another Gen committee, the Gen 163 Committee.

Background

During the early part of theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Britain had a nuclear weapons project, codenamed Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the Bri ...

. A directorate of that name coordinated this effort. Sir John Anderson John Anderson may refer to:

Business

*John Anderson (Scottish businessman) (1747–1820), Scottish merchant and founder of Fermoy, Ireland

* John Byers Anderson (1817–1897), American educator, military officer and railroad executive, mentor of ...

, the Lord President of the Council

The lord president of the Council is the presiding officer of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and the fourth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State, ranking below the Lord High Treasurer but above the ...

, was the minister responsible, and Wallace Akers

Sir Wallace Alan Akers (9 September 1888 – 1 November 1954) was a British chemist and industrialist. Beginning his academic career at Oxford he specialized in physical chemistry. During the Second World War, he was the director of the Tube Al ...

from Imperial Chemical Industries

Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) was a British chemical company. It was, for much of its history, the largest manufacturer in Britain.

It was formed by the merger of four leading British chemical companies in 1926.

Its headquarters were at M ...

(ICI) was appointed the director. At the Quadrant Conference in August 1943, the Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

and the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

, Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, signed the Quebec Agreement

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States outlining the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and specifically nuclear weapons. It was s ...

, which merged Tube Alloys with the American Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

to create a combined British, American and Canadian project. The British considered the Quebec Agreement to be the best deal they could have struck under the circumstances, and the restrictions were the price they had to pay to obtain the technical information needed for a successful post-war nuclear weapons project. Margaret Gowing

Margaret Mary Gowing (), (26 April 1921 – 7 November 1998) was an English historian. She was involved with the production of several volumes of the officially sponsored ''History of the Second World War'', but was better known for her books ...

noted that the "idea of the independent deterrent was already well entrenched."

Many of Britain's top scientists participated in the British contribution to the Manhattan Project

Britain contributed to the Manhattan Project by helping initiate the effort to build the first atomic bombs in the United States during World War II, and helped carry it through to completion in August 1945 by supplying crucial expertise. Follo ...

. A British mission led by Akers assisted in the development of gaseous diffusion

Gaseous diffusion is a technology used to produce enriched uranium by forcing gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6) through semipermeable membranes. This produces a slight separation between the molecules containing uranium-235 (235U) and uranium-2 ...

technology at the SAM Laboratories

K-25 was the codename given by the Manhattan Project to the program to produce enriched uranium for atomic bombs using the gaseous diffusion method. Originally the codename for the product, over time it came to refer to the project, the produ ...

in New York. Another, led by Mark Oliphant

Sir Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant, (8 October 1901 – 14 July 2000) was an Australian physicist and humanitarian who played an important role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and in the development of nuclear weapon ...

, who acted as deputy director at the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), commonly referred to as the Berkeley Lab, is a United States national laboratory that is owned by, and conducts scientific research on behalf of, the United States Department of Energy. Located in ...

, assisted with the electromagnetic separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" n ...

process. John Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft, (27 May 1897 – 18 September 1967) was a British physicist who shared with Ernest Walton the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1951 for splitting the atomic nucleus, and was instrumental in the development of nuclea ...

became the director of the Anglo-Canadian Montreal Laboratory

The Montreal Laboratory in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, was established by the National Research Council of Canada during World War II to undertake nuclear research in collaboration with the United Kingdom, and to absorb some of the scientists and ...

. The British mission to the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

led by James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick, (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English physicist who was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron in 1932. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which inspi ...

, and later Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, (; ; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allied ...

, included distinguished scientists such as Geoffrey Taylor, James Tuck, Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. B ...

, William Penney

William George Penney, Baron Penney, (24 June 19093 March 1991) was an English mathematician and professor of mathematical physics at the Imperial College London and later the rector of Imperial College London. He had a leading role in the d ...

, Otto Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch FRS (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Lise Meitner he advanced the first theoretical explanation of nuclear fission (coining the term) and first ...

, Ernest Titterton

Sir Ernest William Titterton (4 March 1916 – 8 February 1990) was a British nuclear physicist.

A graduate of the University of Birmingham, Titterton worked in a research position under Mark Oliphant, who recruited him to work on radar ...

and Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs (29 December 1911 – 28 January 1988) was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who supplied information from the American, British and Canadian Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union during and shortly aft ...

, who was later revealed to be a spy

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangib ...

for the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. As overall head of the British Mission, Chadwick forged a close and successful partnership with Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Leslie R. Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project, and ensured that British participation was complete and wholehearted.

Origin

TheGovernment of the United Kingdom

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal coat of arms of t ...

is directed by the cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

, a group of senior government minister

A minister is a politician who heads a ministry, making and implementing decisions on policies in conjunction with the other ministers. In some jurisdictions the head of government is also a minister and is designated the ‘prime minister’, � ...

s led by the Prime Minister. Most of the day-to-day work of the cabinet is carried out by cabinet committees, rather than by the full cabinet. Each committee has its own area of responsibility, and their decisions are binding on the entire cabinet. Their membership and scope is determined by the Prime Minister.

During the post-Second World War period, in addition to standing committees, there were ''ad hoc'' committees that were convened to handle a single issue. These were normally short-lived. Each was given a prefix of Gen and a number. Gen 183, for example, was the Committee on Subversive Activities. Between 1945 and 1964, Gen (for general) committees were sequentially numbered from 1 to 881 in order of formation.

Prime Minister Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

, who succeeded Churchill in June 1945, created the Gen 75 Committee on 10 August 1945 to examine the feasibility of a nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

programme. It was known informally by Attlee as the "Atomic Bomb Committee", although no explicit decision to build one was made until January 1947. The Gen 75 Committee differed from other Gen committees in that its deliberations were not reported to the full cabinet, and were shrouded in secrecy even at that level. The entire subject of nuclear weapons was kept off the full cabinet agenda, and cabinet ministers not attending the meetings may not have even known of its existence.

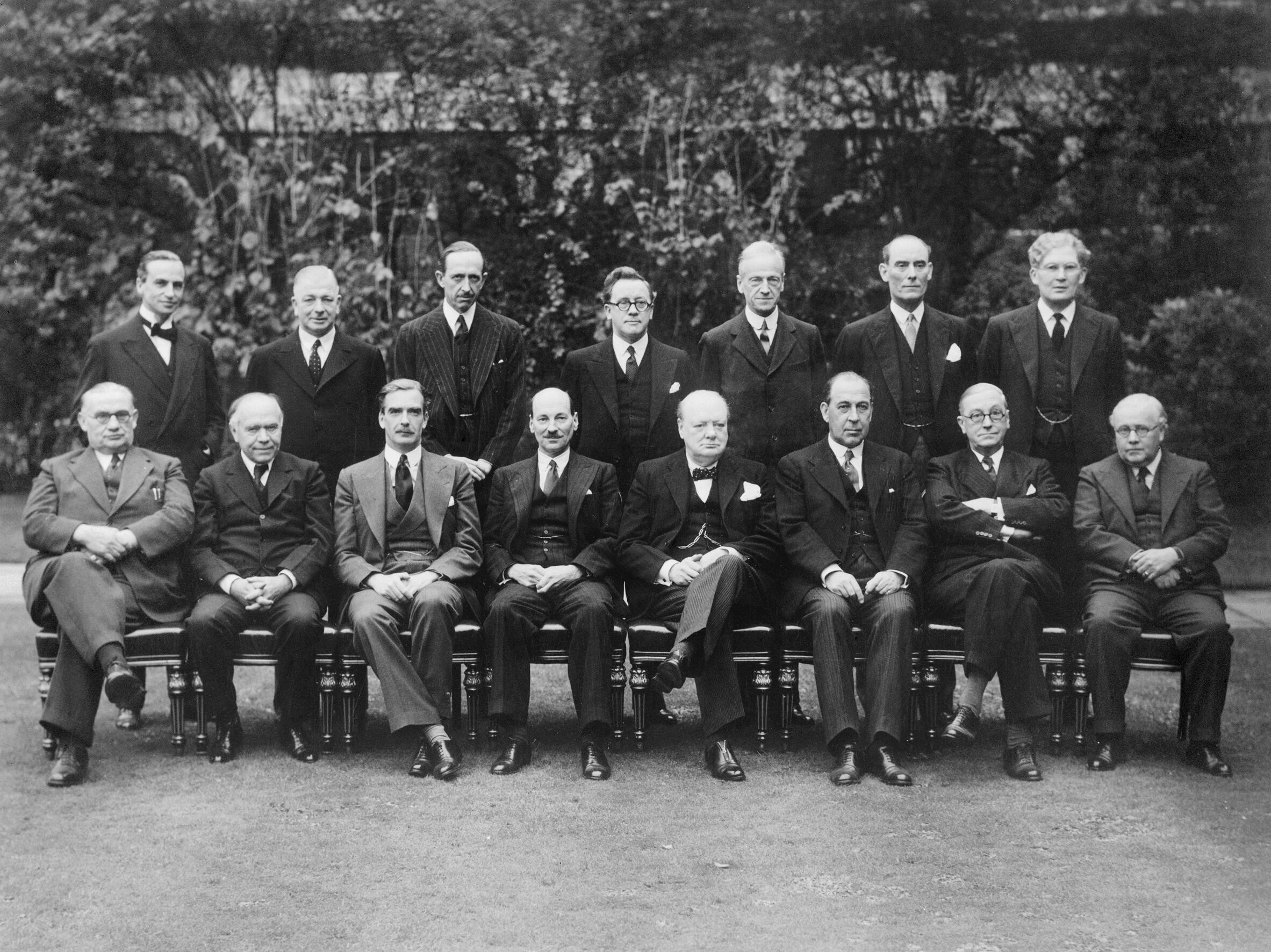

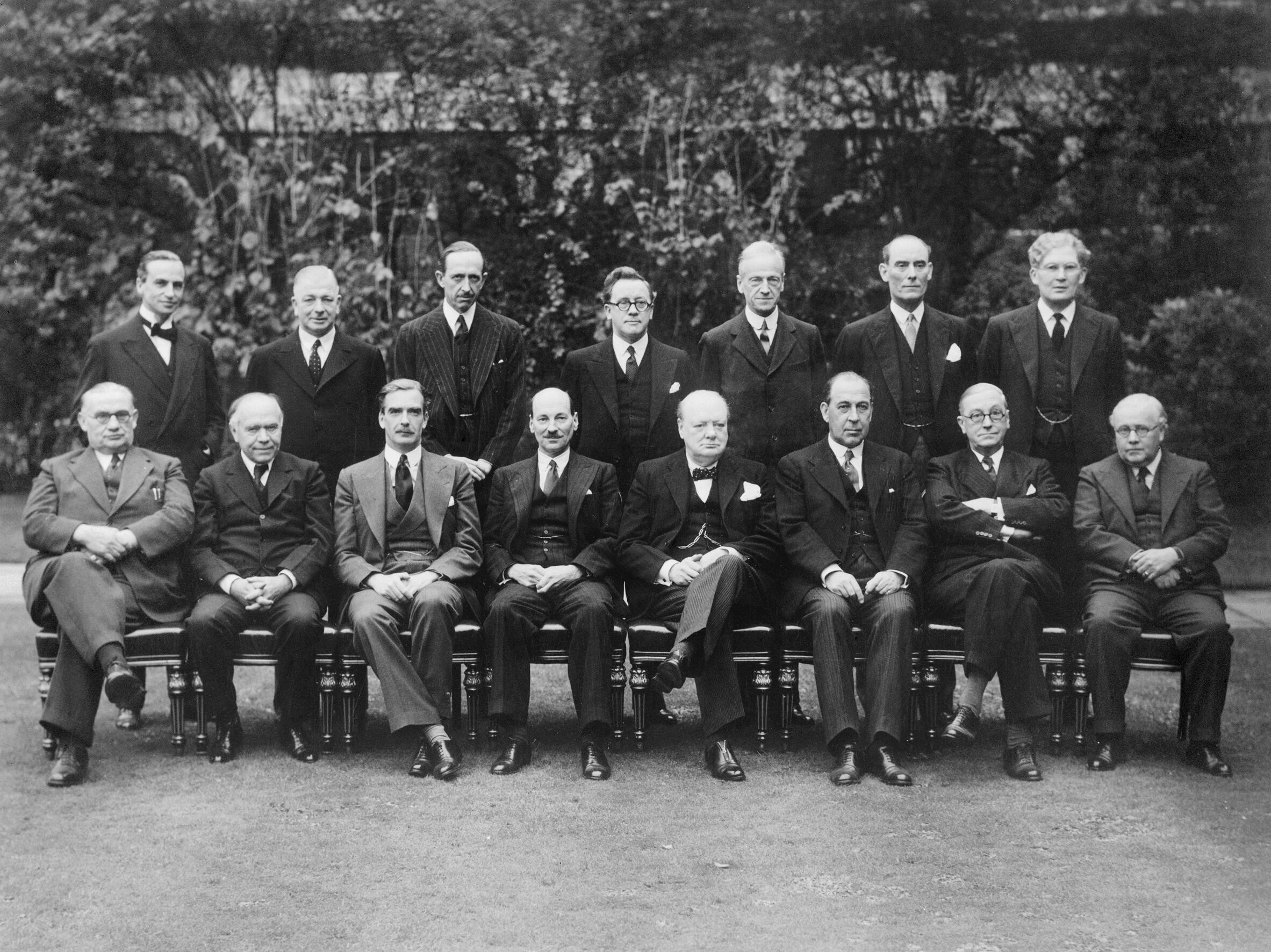

Composition

Membership of Gen 75 initially consisted of five ministers: the Prime Minister, Clement Attlee; the Lord President of the Council,Herbert Morrison

Herbert Stanley Morrison, Baron Morrison of Lambeth, (3 January 1888 – 6 March 1965) was a British politician who held a variety of senior positions in the UK Cabinet as member of the Labour Party. During the inter-war period, he was Mini ...

; the Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

, Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in the years 1922–19 ...

; and the President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. This is a committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centu ...

, Stafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps (24 April 1889 – 21 April 1952) was a British Labour Party politician, barrister, and diplomat.

A wealthy lawyer by background, he first entered Parliament at a by-election in 1931, and was one of a handful of La ...

. It was soon expanded with the addition of the Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and abov ...

, Arthur Greenwood

Arthur Greenwood, (8 February 1880 – 9 June 1954) was a British politician. A prominent member of the Labour Party from the 1920s until the late 1940s, Greenwood rose to prominence within the party as secretary of its research department f ...

, and the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

, Hugh Dalton

Edward Hugh John Neale Dalton, Baron Dalton, (16 August 1887 – 13 February 1962) was a British Labour Party economist and politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1945 to 1947. He shaped Labour Party foreign policy in the 1 ...

. After the Gen 75 Committee decided that the nuclear weapons project should be the responsibility of the Ministry of Supply

The Ministry of Supply (MoS) was a department of the UK government formed in 1939 to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to all three British armed forces, headed by the Minister of Supply. A separate ministry, however, was responsible for aircr ...

, the Minister of Supply

The Minister of Supply was the minister in the British Government responsible for the Ministry of Supply, which existed to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to the national armed forces. The position was campaigned for by many sceptics of the for ...

, John Wilmot

John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester (1 April 1647 – 26 July 1680) was an English poet and courtier of King Charles II's Restoration court. The Restoration reacted against the "spiritual authoritarianism" of the Puritan era. Rochester embodie ...

, was added.

Activity

International relations

As reports came in of the devastation caused by theatomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the on ...

, Attlee considered how nuclear weapons had changed the nature of warfare and international relations. He raised the matter with the Gen 75 Committee, and Bevin suggested that a first step should be a letter to Truman suggesting a review of policy. The letter was sent to Truman on 20 September 1945. A response was slow in coming; Truman was concerned about the effect that Anglo-American and Canadian talks might have on the Soviet Union. At Attlee's insistence, talks were scheduled for 9 November 1945.

The Gen 75 Committee meeting discussed what should be said at the meeting, in particular what British policy towards the Soviet Union should be. Bevin took a conciliatory line at the Gen 75 Committee meeting on 11 October 1945, only to take a harder one at the meeting a week later. Unusually, the matter was placed before the full cabinet. Hopes were expressed that Britain might be able to broker a deal that would head off a schism between the United States and the Soviet Union. Ultimately, though, it endorsed Attlee's preference that practical knowledge of nuclear weapons design not be shared with the Soviet Union.

Research establishment

During the war, Chadwick, Cockcroft, Oliphant, Peierls,Harrie Massey

Sir Harrie Stewart Wilson Massey (16 May 1908 – 27 November 1983) was an Australian mathematical physicist who worked primarily in the fields of atomic and atmospheric physics.

A graduate of the University of Melbourne and Cambridge Univer ...

and Herbert Skinner had met in Washington, DC, in November 1944, and drawn up a proposal for a British atomic energy research establishment, which they had calculated would cost around £1.5 million. The Tube Alloys Committee endorsed their recommendation in April 1945, and Anderson, in his capacity as chairman of the Advisory Committee on Atomic Energy, submitted the memorandum advocating it to the Gen 75 Committee. It endorsed the creation of the Atomic Energy Research Establishment

The Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE) was the main Headquarters, centre for nuclear power, atomic energy research and development in the United Kingdom from 1946 to the 1990s. It was created, owned and funded by the British Governm ...

in September, Attlee announced the decision in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

on 29 October 1945.

Organisation of production

In October 1945, the Gen 75 Committee considered the issue of ministerial responsibility for atomic energy. The Cabinet Secretary, Sir Edward Bridges, and the Advisory Committee on Atomic Energy both recommended that it be placed within the Ministry of Supply. Developing atomic energy would require an enormous construction effort, which the Ministry of Supply was best equipped to undertake. The Tube Alloys Directorate was transferred from theDepartment of Scientific and Industrial Research Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, abbreviated DSIR was the name of several British Empire organisations founded after the 1923 Imperial Conference to foster intra-Empire trade and development.

* Department of Scientific and Industria ...

to the Ministry of Supply effective 1 November 1945.

To coordinate the atomic energy effort, the Gen 75 Committee decided to appoint a Controller of Production, Atomic Energy (CPAE). Wilmot suggested Marshal of the Royal Air Force

Marshal of the Royal Air Force (MRAF) is the highest rank in the Royal Air Force (RAF). In peacetime it was granted to RAF officers in the appointment of Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS), and to retired Chiefs of the Air Staff (CAS), who were ...

Lord Portal, the wartime Chief of the Air Staff. Portal was reluctant to accept the post, as he felt that he lacked administrative experience outside the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

, but eventually accepted it for a two-year term, commencing in March 1946. In this role he had direct access to the Prime Minister. Portal ran the project until 1951, when he was succeeded by Sir Frederick Morgan. It was hidden under the cover name High Explosive Research

High Explosive Research (HER) was the British project to develop atomic bombs independently after the Second World War. This decision was taken by a cabinet sub-committee on 8 January 1947, in response to apprehension of an American retur ...

.

Nuclear reactors

An early debate among the scientists was whether thefissile material

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be ty ...

for an atomic bomb should be uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exis ...

or plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

. Tube Alloys had performed much of the pioneering research on gaseous diffusion for uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238U ...

, and Oliphant's team in Berkeley were well-acquainted with the electromagnetic process. The staff that had remained in Britain strongly favoured uranium-235; but the scientists that had worked in the United States argued for plutonium on the basis of its greater efficiency as an explosive, despite the fact that they had neither the expertise in the design of nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

s to produce it, nor the requisite knowledge of plutonium chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

or metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

to extract it. However, the Montreal Laboratory had designed and was building pilot reactors, and had carried out some work on separating plutonium from uranium.

The Manhattan Project had pursued both avenues, and the scientists who had worked at Los Alamos were aware of work there with composite cores that used both; but there were concerns that Britain might not have the money, resources or skilled manpower for this. In the end, it came down to economics; a reactor could be built more cheaply than a separation plant that produced an equivalent quantity of enriched uranium, and made more efficient use of uranium fuel. A reactor and separation plant capable of producing enough plutonium for fifteen bombs per year was costed at around £20 million.

It fell to the Gen 75 Committee to decide how many reactors should be built at its meeting on 18 December 1945. Considering the demands that reactors would make on scarce skilled labour and materials, the Gen 75 Committee decided to defer a decision on building a second reactor, but to proceed with the first one "with the highest urgency and importance". Reactors were built at the former ROF Sellafield

Sellafield is a large multi-function nuclear site close to Seascale on the coast of Cumbria, England. As of August 2022, primary activities are nuclear waste processing and storage and nuclear decommissioning. Former activities included nucle ...

. To avoid any confusion with Springfields

Springfields is a nuclear fuel production installation in Salwick, near Preston in Lancashire, England (). The site is currently operated by Springfields Fuels Limited, under the management of Westinghouse Electric UK Limited, on a 150-year l ...

, where uranium metal was produced, the name was changed to Windscale.

Gaseous diffusion facility

A few months later, Portal, who had not been appointed when this decision was taken, began to have doubts. Word reached him of problems with theHanford Site

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington. The site has been known by many names, including SiteW a ...

reactors, which had been all but completely shut down due to Wigner's disease. On a visit to the United States in May 1946, Groves advised Portal not to build a reactor. By this time, there was interest from the scientists in making better use of uranium fuel by re-enrichment of spent fuel rods. A gaseous diffusion plant was costed at somewhere between £30 and £40 million. The Gen 75 Committee considered the proposal in October 1946. Michael Perrin

Sir Michael Willcox Perrin, CBE, FRSC (13 September 1905 – 18 August 1988) was a scientist who created the first practical polythene, directed the first British atomic bomb programme, and participated in the Allied intelligence of the Nazi a ...

, who was present, later recalled that:

The Gen 75 Committee thereupon approved the construction of the proposed gaseous diffusion plant, which was built on the site of an old Royal Ordnance Factory

Royal Ordnance Factories (ROFs) was the collective name of the UK government's munitions factories during and after the Second World War. Until privatisation, in 1987, they were the responsibility of the Ministry of Supply, and later the Ministr ...

at Capenhurst

Capenhurst is a village and civil parish in Chester in the unitary authority of Cheshire West and Chester and the ceremonial county of Cheshire England. According to the 2001 Census, Capenhurst had a population of 237, increasing to 380 at the 2 ...

, near Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

.

Gen 163 Committee

In July 1946, theChiefs of Staff Committee

The Chiefs of Staff Committee (CSC) is composed of the most senior military personnel in the British Armed Forces who advise on operational military matters and the preparation and conduct of military operations. The committee consists of the Ch ...

considered the issue of nuclear weapons, and recommended that Britain acquire them. This recommendation was accepted by the Cabinet Defence Committee on 22 July 1946. The Chief of the Air Staff, Lord Tedder, officially requested an atomic bomb on 9 August 1946. The Chiefs of Staff estimated that 200 bombs would be required by 1957. Despite this, and the research and construction of facilities that had already been approved, there was still no official decision to proceed with making atomic bombs.

Dissent came from Patrick Blackett

Patrick Maynard Stuart Blackett, Baron Blackett (18 November 1897 – 13 July 1974) was a British experimental physicist known for his work on cloud chambers, cosmic rays, and paleomagnetism, winning the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1948. ...

, who submitted a paper to the Gen 75 Committee that forcefully argued against Britain acquiring atomic bombs. The Foreign Office, however, labelled his ideas "dangerous and misleading rubbish", and rejected a characterisation of the Soviet Union as a peace-loving state with no expansionist ambitions whereas the United States was an aggressor predisposed towards preemptive war

A preemptive war is a war that is commenced in an attempt to repel or defeat a perceived imminent offensive or invasion, or to gain a strategic advantage in an impending (allegedly unavoidable) war ''shortly before'' that attack materializes. It ...

.

Portal submitted his proposal to proceed with the manufacture of nuclear weapons at the 8 January 1947 meeting of the Gen 163 Committee. This was a smaller committee, consisting of Attlee, Morrison, Bevin, Wilmot, the Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs

The position of Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs was a British cabinet-level position created in 1925 responsible for British relations with the Dominions – Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Newfoundland, and the Irish Free S ...

, Lord Addison, and the Minister of Defence

A defence minister or minister of defence is a Cabinet (government), cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from coun ...

, A. V. Alexander

Albert Victor Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Hillsborough, (1 May 1885 – 11 January 1965), was a British Labour and Co-operative politician. He was three times First Lord of the Admiralty, including during the Second World War, and then Mi ...

. It was this committee, which met only once, that agreed to proceed with the development of atomic bombs. Once again, Bevin was a strong supporter, arguing that "We could not afford to acquiesce in an American monopoly of this new development." It also endorsed Portal's proposal to place Penney in charge of the bomb development effort, although Penney was not informed of this decision until May.

Abolishment

With the decision taken to proceed with nuclear weapons development, the Gen 75 Committee was replaced in February 1947 by a standing committee, the Atomic Energy Committee "to deal with questions of policy in the field of atomic energy which require the consideration of Ministers". Its membership was that of the Gen 75 Committee, plus Alexander and Addison. However, the Atomic Energy Committee only met five times in 1947, twice in 1948, four times in 1949, twice in 1950 and just once in 1951. Important decisions therefore continued to be made by Gen committees.Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * {{Portal bar, Politics, United Kingdom, Nuclear technology Nuclear history of the United Kingdom 1945 in British politics 1945 establishments in the United Kingdom Cabinet of the United Kingdom Public policy in the United Kingdom 1947 disestablishments in the United Kingdom Nuclear strategy Clement Attlee